Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecotourism and Climate Change

2.2. Big-Five Personality Domains and Environmental Concerns and Attitudes

2.3. COVID-19 Pandemic and Environmental Attitudes & Personality Domains

3. Materials and Methods

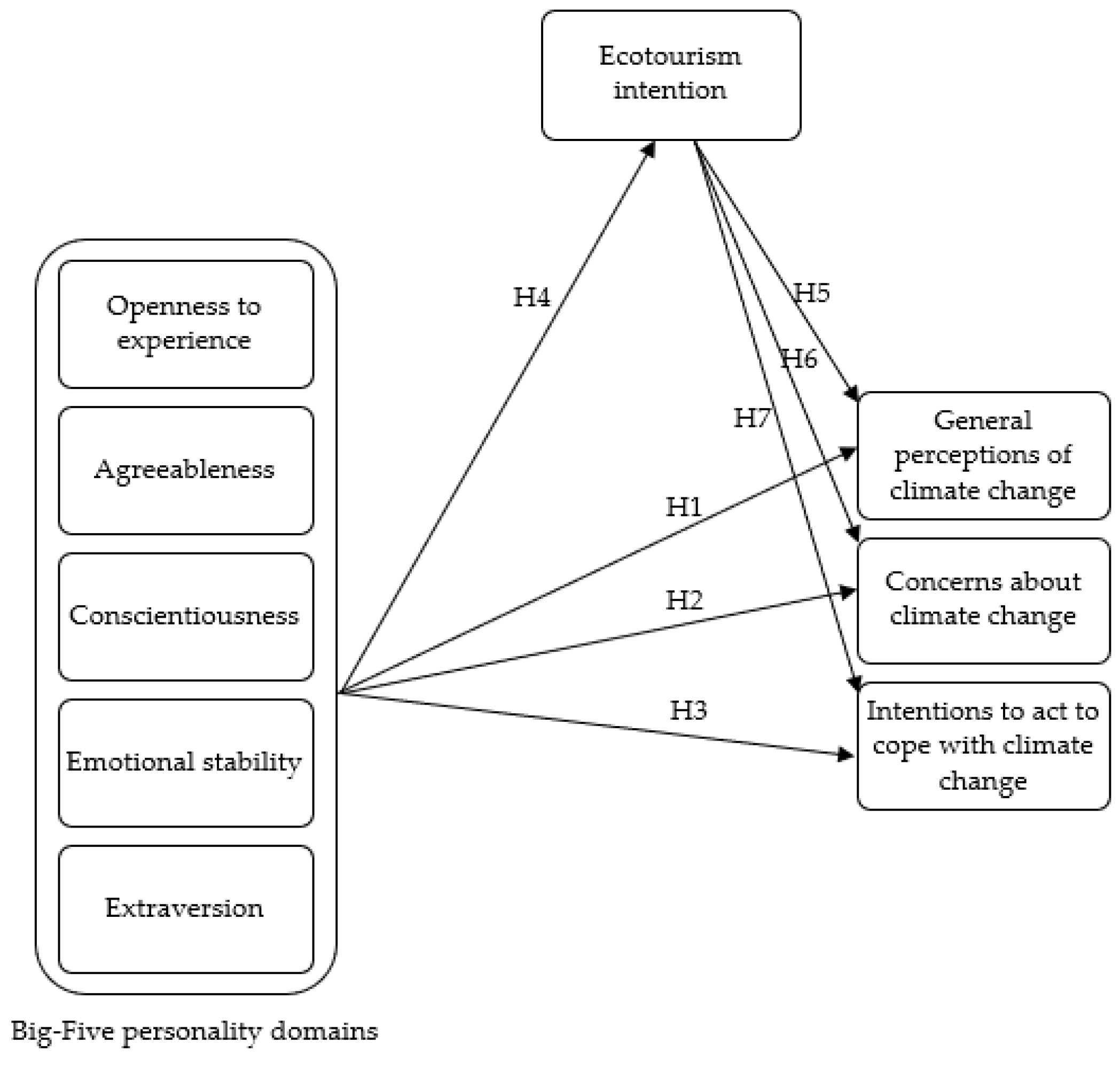

3.1. The Research Model

3.2. Data Collection Tool

3.3. Population and Sample

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.2.1. Reliability

4.2.2. Normality

4.2.3. Model Fit Indices

4.2.4. Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity

4.3. Structural Model

4.3.1. SEM Model Fit Indices

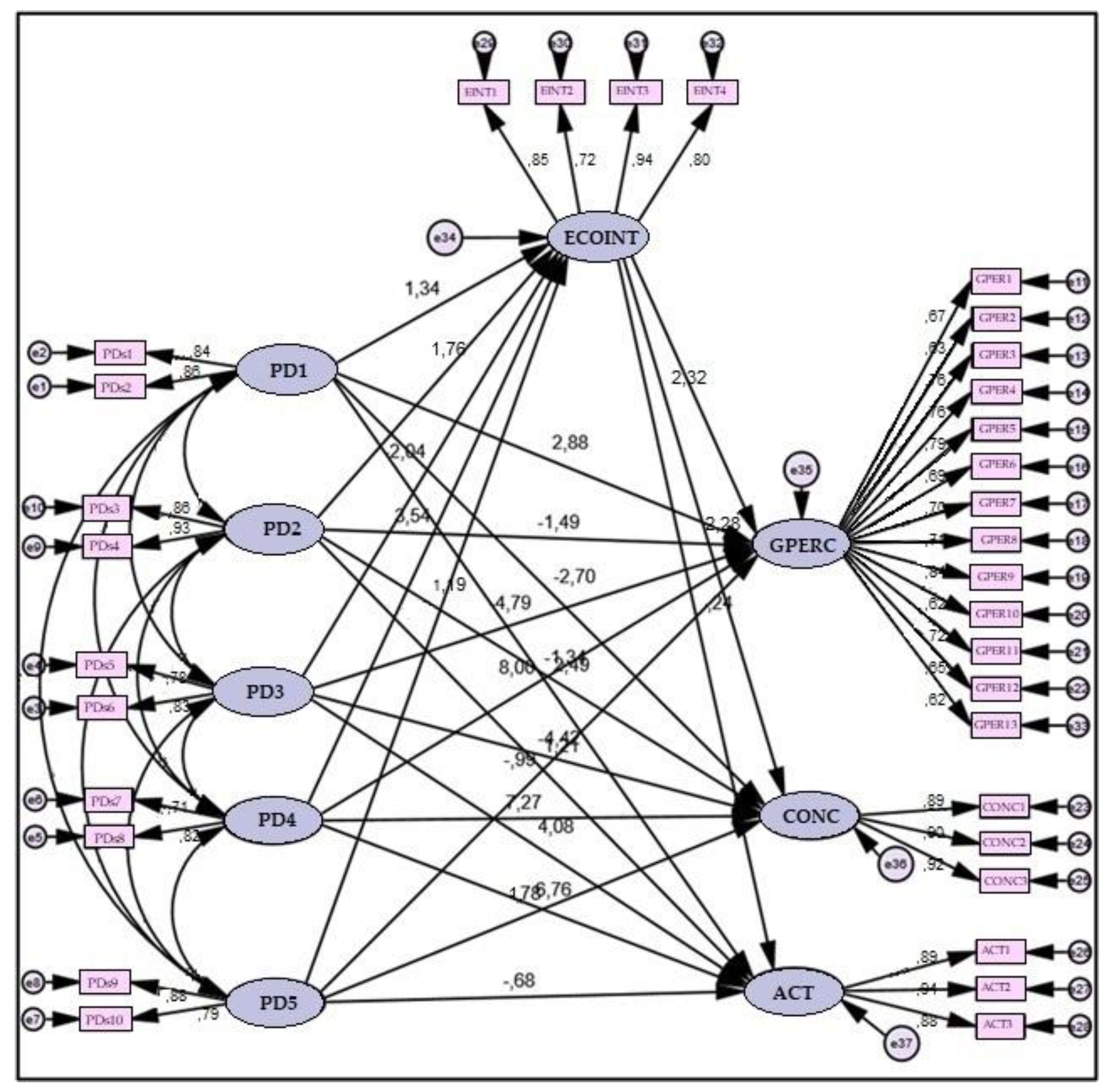

4.3.2. Path Diagram

4.3.3. Hypothesis Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| ECOINT | Ecotourism intention |

| GPERC | General perceptions of climate change |

| CONC | Concerns about climate change |

| ACT | Intentions to act to cope with climate change |

| PDs | Personality domains |

References

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S. A review of research into tourism and climate change - Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research 2022, 95, 103409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yin, J.; Wu, B. Climate change and tourism: A scientometric analysis using CiteSpace. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2018, 26, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, M.; Kim, S.; Del Chiappa, G.; Wassler, P. Ecotourists’ intentions, worldviews, environmental values: Does climate change matter? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2022, 25, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, C.J.; Hernández, M.M.G.; Lam-González, Y. COVID-19 effects on travel choices under climate risks. Annals of Tourism Research 2023, 103, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, F.; Adil, M.; Wu, J. Examining ecotourism intention: The role of tourists’ traits and environmental concerns. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 940116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Gursoy, D.; Xu, H. Impact of personality traits and involvement on prior knowledge. Annals of Tourism Research 2014, 48, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. ; J. Hay. In Climate change and tourism: From policy to practice; Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC]. Available online: https://unfccc.int/ (accessed on 12.06.2025).

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Education for sustainable development: A systemic framework for connecting the SDGs to educational outcomes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekardt, F.; Wieding, J.; Zorn, A. Paris agreement, precautionary principle and human rights: Zero emissions in two decades? Sustainability 2018, 10, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow Declaration on Climate Action in Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/the-glasgow-declaration-on-climate-action-in-tourism (accessed on 11.06.2025).

- Buckley, R.; Gretzel, U.; Scott, D.; Weaver, D.; Becken, S. Tourism megatrends. Tourism Recreation Research 2015, 40, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. Climate change. In Encyclopedia of Tourism, 1st ed.; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G. Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. Annals of Tourism Research 2012, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S. L.; Wu, L.; Morrison, A.M. A review of studies on tourism and climate change from 2007 to 2021. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2024, 36, 1512–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Martín, M.B. Weather, climate and tourism a geographical perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 2005, 32, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. Uncertainties in predicting tourist flows under scenarios of climate change. Climatic Change 2006, 79, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. Tourism and climate change: Impacts, adaptation and mitigation, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, United States of America, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D. Can sustainable tourism survive climate change? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2011, 19, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamey, R.K. Principles of ecotourism. In The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism; Weaver, D.B., Ed.; Cabi Publishing: Wallingford, United Kingdom, 2001; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Ecotourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Del Chiappa, G. The influence of materialism on ecotourism attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Travel Research 2016, 55, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P. Ecotourism from a conceptual perspective, an extended definition of a unique tourism form. International Journal of Tourism Research 2000, 2, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, E.M.; Goldberg, L.R.; Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Profiling the pro-environmental individual: A personality perspective. Journal of Personality 2012, 80, 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.P.; Allik, J.; McCrae, R.R.; Benet-Martínez, V. The geographic distribution of big five personality traits: Patterns and profiles of human self-description across 56 nations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2007, 38, 173–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R.; Costa, P.T. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1987, 52, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann Jr, W.B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasova, O. The big five personality traits as antecedents of eco-friendly tourist behavior. Personality and Individual Differences 2015, 83, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.S.T.; Khanh, C.N.T. Ecotourism intention: The roles of environmental concern, time perspective and destination image. Tourism Review 2021, 76, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Advances in Consumer Research 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.C.; Liu, C.H.S. Moderating and mediating roles of environmental concern and ecotourism experience for revisit intention. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2017, 29, 1854–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, Y.H.; Wu, Y.J. How personality affects environmentally responsible behaviour through attitudes towards activities and environmental concern: Evidence from a national park in Taiwan. Leisure Studies 2020, 39, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B. Personality and environmental concern. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermich, K.; Johnson, E.K.; Griffith, R.M.; Beingolea, M.M. The influence of personality traits on attitudes towards climate change: An exploratory study. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 168, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Sibley, C.G. The big five personality traits and environmental engagement: Associations at the individual and societal level. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2012, 32, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Sustainable tourism and the grand challenge of climate change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K. El niño’s implications for the Victoria Falls Resort and tourism economy in the era of climate change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.T.; Ho, M.T.; Huang, M.L. Understanding the impact of tourist behavior change on travel agencies in developing countries: Strategies for enhancing the tourist experience. Acta Psychologica 2024, 249, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Srivastava, S.; Sakashita, M.; Islam, N.; Dhir, A. Personality and travel intentions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: An artificial neural network (ANN) approach. Journal of Business Research 2022, 142, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Del Chiappa, G. The influence of materialism on ecotourism attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Travel Research 2016, 55, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D.S. A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 06.01.2025).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, United States of America, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.L.; Morgan, G.B. Survey Scales: A Guide to Development, Analysis, and Reporting; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, M. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference - 17.0 Update, 10th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Çapık, C. Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışmalarında doğrulayıcı faktör analizinin kullanımı. Anadolu Hemşirelik ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 2014, 17, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D. Environmental citizenship questionnaire (ECQ): The development and validation of an evaluation instrument for secondary school students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşlıoğlu, M.M. Sosyal bilimlerde faktör analizi ve geçerlilik: Keşfedici ve doğrulayıcı faktör analizlerinin kullanılması. İstanbul Üniversitesi İşletme Fakültesi Dergisi 2017, 46, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D.; DiStefano, C.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Lee, T. Evaluating SEM model fit with small degrees of freedom. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2021, 57, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximénez, C.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Shi, D.; Revuelta, J. Assessing cutoff values of SEM fit indices: Advantages of the unbiased SRMR index and its cutoff criterion based on communality. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2022, 29, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmazdoğan, O.C.; Doğan, R.Ş.; Altıntaş, E. The impact of the source credibility of Instagram influencers on travel intention: The mediating role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Vacation Marketing 2021, 27, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Adaptation of assessment scales in cross-national research: Issues, guidelines, and caveats. International Perspectives in Psychology 2016, 5, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.B.; Nguyen, D.T.A. Future time perspective, eco-destination image, environmental concern, ecotourism behavioral intention in Vietnamese ecotourists: The moderating role of environmental knowledge. International Journal of Tourism Research 2025, 27, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimul, A.S.; Faroque, A.R.; Teah, K.; Azim, S.M.F.; Teah, M. Enhancing consumers’ intention to stay in an eco-resort via climate change anxiety and connectedness to nature. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 442, 141096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Dolderman, D. Personality predictors of consumerism and environmentalism: A preliminary study. Personality and Individual Differences 2007, 43, 1583–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucholska, K.; Gulla, B.; Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A. Climate change beliefs, emotions and pro-environmental behaviors among adults: The role of core personality traits and the time perspective. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, E.; Frumento, S.; Gemignani, A.; Menicucci, D. Personality traits and climate change denial, concern, and proactivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2024, 95, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westland, J.C. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 254 | 62,1% |

| Male | 155 | 37,9% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 179 | 43,8% |

| Single | 230 | 56,2% | |

| Age | Under 25 years | 24 | 5,9% |

| 25–35 years | 80 | 19,6% | |

| 36–45 years | 88 | 21,5% | |

| 46–55 years | 112 | 27,4% | |

| 56–65 years | 105 | 25,7% | |

| Education Status | High school | 35 | 8,6% |

| Associate degree | 39 | 9,5% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 209 | 51,1% | |

| Master’s degree | 88 | 21,5% | |

| Doctorate | 38 | 9,3% | |

| Monthly Income | Minimum wage or below (440 USD or less) |

47 | 11,5% |

| 440-1,030 USD | 120 | 29,3% | |

| 1,030-1,550 USD | 134 | 32,8% | |

| 1,550-2,060 USD | 51 | 12,5% | |

| 2,060 USD or more | 57 | 13,9% | |

| Profession | Student | 29 | 7,1% |

| Unemployed | 16 | 3,9% | |

| Entrepreneur | 56 | 13,7% | |

| Public sector | 122 | 29,8% | |

| Private sector | 88 | 21,5% | |

| Retired | 98 | 24,0% | |

| Tour Organization | I plan and manage my own schedule | 212 | 51,8% |

| I join programs organized by friends and/or clubs | 149 | 36,4% | |

| I receive professional support from travel agencies | 33 | 8,1% | |

| All of the above | 15 | 3,7% | |

| Average Length of Stay | Day trip | 45 | 11,0% |

| 1-3 nights | 170 | 41,6% | |

| 4-6 nights | 152 | 37,2% | |

| 7 nights or more | 42 | 10,3% |

| Factor Loads | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: GPERC | 0.928 | 0.500 | |

| GPERC1 | 0.67 | ||

| GPERC2 | 0.63 | ||

| GPERC3 | 0.76 | ||

| GPERC4 | 0.76 | ||

| GPERC5 | 0.79 | ||

| GPERC6 | 0.69 | ||

| GPERC7 | 0.70 | ||

| GPERC8 | 0.71 | ||

| GPERC9 | 0.84 | ||

| GPERC10 | 0.62 | ||

| GPERC11 | 0.72 | ||

| GPERC12 | 0.65 | ||

| GPERC13 | 0.62 | ||

| Factor 2: CONC | 0.930 | 0.816 | |

| CONC1 | 0.89 | ||

| CONC2 | 0.90 | ||

| CONC3 | 0.92 | ||

| Factor 3: ACT | 0.930 | 0.817 | |

| ACT1 | 0.89 | ||

| ACT2 | 0.94 | ||

| ACT3 | 0.88 | ||

| Factor 4: ECOINT | 0.899 | 0.691 | |

| ECOINT1 | 0.85 | ||

| ECOINT2 | 0.72 | ||

| ECOINT3 | 0.94 | ||

| ECOINT4 | 0.80 | ||

| Factor 5: PDs | 0.957 | 0.692 | |

| PDs1 | 0.84 | PD1 (CR: 0.839; AVE: 0.72) | |

| PDs2 | 0.86 | ||

| PDs3 | 0.86 | PD2 (CR: 0.890; AVE: 0.802) | |

| PDs4 | 0.93 | ||

| PDs5 | 0.78 | PD3 (CR: 0.787; AVE: 0.649) | |

| PDs6 | 0.83 | ||

| PDs7 | 0.71 | PD4 (CR: 0.740; AVE: 0.588) | |

| PDs8 | 0.82 | ||

| PDs9 | 0.88 | PD5 (CR: 0.823; AVE: 0.699) | |

| PDs10 | 0.79 | ||

| Constructs | GPERC | CONC | ACT | ECOINT | PDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPERC | 0.707 | ||||

| CONC | 0.696 | 0.903 | |||

| ACT | 0.668 | 0.683 | 0.904 | ||

| ECOINT | 0.270 | 0.241 | 0.285 | 0.831 | |

| PDs | 0.161 | 0.196 | 0.168 | 0.170 | 0.832 |

| AVE | 0.500 | 0.816 | 0.817 | 0.691 | 0.692 |

| Constructs | Confirmed | β | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | |||

| H1a | Yes | 2.876 | 5.75*** |

| H1b | Yes | -1.494 | -2.99*** |

| H1c | Yes | -4.79 | -9.58*** |

| H1d | Yes | 7.996 | 15.99*** |

| H1e | No | -0.985 | -1.97** |

| H2 | |||

| H2a | No | -2.700 | -5.4NS |

| H2b | Yes | -1.338 | -2.68*** |

| H2c | Yes | -4.416 | -8.83*** |

| H2d | Yes | 7.272 | 14.54*** |

| H2e | Yes | 1.784 | 2.97*** |

| H3 | |||

| H3a | Yes | 2.488 | 4.98*** |

| H3b | Yes | -1.207 | -2.41** |

| H3c | Yes | 4.081 | 8.16*** |

| H3d | Yes | 6.759 | 13.52*** |

| H3e | No | -0.680 | -1.36NS |

| H4 | |||

| H4a | Yes | 1.339 | 2.68*** |

| H4b | Yes | 1.764 | 2.53** |

| H4c | Yes | 2.036 | 4.07*** |

| H4d | Yes | 3.544 | 7.09*** |

| H4e | Yes | 1.187 | 2.37** |

| H5-H6-H7 | |||

| H5 | Yes | 2.321 | 4.64*** |

| H6 | Yes | 2.283 | 4.56*** |

| H7 | No | 0.242 | 0.48NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).