Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Assembly Index (Ai) – the fewest number of steps required to make the molecule

- Copy Number (Ni) – the number of identical molecules counted

2. Materials and Methods

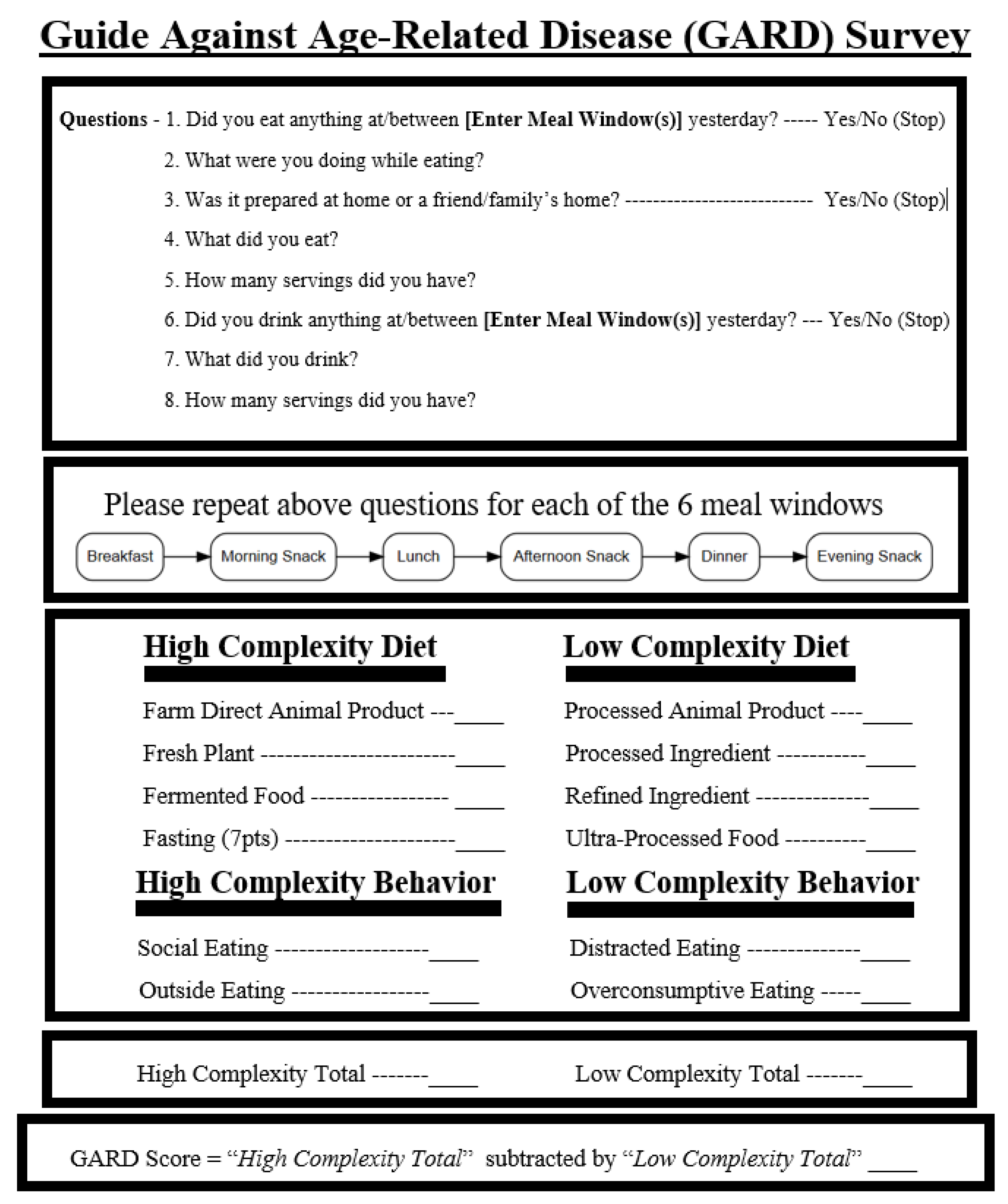

| Quantifiable Food and Food Behavior Categories | |||

| High Complexity Diet | Point Value | Low Complexity Diet | Point Value |

| Farm Direct Animal Product | (+1) | Processed Animal Product | (-1) |

| Fresh Plants | (+1) | Processed Ingredient | (-1) |

| Fermented Foods | (+1) | Refined Ingredient | (-1) |

| Fasting (Autophagy) | (+7) | Ultra-Processed Food | (-1) |

| High Complexity Behavior | Point Value | Low Complexity Behavior | Point Value |

| Social Eating | (+1) | Distracted Eating | (-1) |

| Outside Eating | (+1) | Over consumptive Eating | (-1) |

Data Collection Methods

Collecting the Food Diary

Defining a Point

Grading of High Complexity Variables

Fresh Plant

Farm Direct Animal Product

Fermented Food

Fasting (Autophagy)

Social Eating

Outside Eating

Grading of Low Complexity Variables

Processed Ingredients

Refined Ingredients

Processed Animal Products

Ultra-Processed Foods

Distracted Eating

Over Consumptive Eating

Grading the Food Diary

Survey Distribution

Population

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Internal Validity

Face Validity

| Complexity Grade for a Generic Ham Sandwich | |||

| Ingredient | Variable | Complexity Grade | Point Value |

| White Bread | Refined Ingredient | Low | (-1) |

| Deli Ham | Processed Animal Product | Low | (-1) |

| Mustard | Processed Ingredient (Food Dye) | Low | (-1) |

| Tomato | Fresh Plant | High | (+1) |

| Lettuce | Fresh Plant | High | (+1) |

| GARD Score = “High Complexity Total” subtracted by “Low Complexity Total” = (-1) | |||

| Category | Variable | Ai (Assembly Index) of Average Molecule | Ni (Copy Number) of Average Molecule | Total |

GARD Score |

| High Complexity |

Fresh Plant | 9 (Extremely High) | 9 (Extremely High) | 18 | (+1) |

| Healthy Animal Product | 9 (Extremely High) | 9 (Extremely High) | 18 | (+1) | |

| Fermented Food | 9 (Extremely High) | 9 (Extremely High) | 18 | (+1) | |

| Autophagy (Fasting) | 9 (Extremely High) | 9 (Extremely High) | 18 | (+1) | |

| Low Complexity |

Processed Ingredient | 3 (Low) | 8 (Very High) | 11 | (-1) |

| Refined Ingreient | 2 (Very Low) | 9 (Extremely High) | 11 | (-1) | |

| Processed Animal Product | 7 (High) | 8 (Very High) | 15 | (-1) | |

| Ultra-Processed Food | 1 (Extremely Low) | 9 (Extremely High) | 10 | (-1) |

| Category | Variable | Internal Validity in Assembly Theory |

| High Complexity |

Fresh Plant | Fresh plants contain diverse, complex biomolecules (e.g., polyphenols, fibers) requiring many synthetic steps (Extremely High Ai), with widespread repetition in plant tissue (Extremely High Ni). |

| Farm Direct Animal Product | Whole animal products (meat, seafood) have structured proteins, fats, carbohydrates and nucleic acids (Extremely High Ai) with considerable repetition within a given tissue (Extremely High Ni). | |

| Fermented Food | Fermentation increases biochemical complexity via the presence of microbiotic life (Extremely High Ai) with high molecular repetition within individual bacteria (Extremely High Ni). | |

| Autophagy (Fasting) | Autophagy recycles highly structured biomolecules, organelles, glycogen, fatty acid chains (Extremely High Ai), which exist in repeating cell types with in a tissue (Extremely High Ni). | |

| Low Complexity |

Processed Ingredient | Processed ingredients are designed for easy manufacturing (Low Ai) at large volume (Very High Ni) |

| Refined Ingredient | Industrial processing simplifies molecular structure taking complex biomolecules (i.e. Amylopectin) and turning them into simplified molecules (i.e. Glucose, Fructose) (low Ai) while increasing uniformity and repetition (very high Ni). | |

| Processed Animal Product | Research shows measurable differences in nutritional complexity between processed meat and farm-direct, pasture-raised meat. Specifically, meat from farmers' markets—typically pasture-raised and minimally handled—contains significantly higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), and fat-soluble vitamins like A and E [54,55]. These nutrients result from the animals’ forage-based diets and shorter storage times, which help preserve delicate compounds and vitamins [56,57]. In contrast, processed meat, while chemically dense and uniform, lacks this diversity and freshness. As a result, since processed meat exhibits contains less complex molecule (high Ai) compared to farm-direct meat, which contains a more varied and functionally rich molecular structure. However, processed meat still retains a high number of repeated molecules through out the tissues (Very High). | |

| Ultra-Processed Food | Ultra-processed foods by definition contain manufactured ingredients (extremely low Ai) and refined ingredients that are mass-produced and highly repetitive (extremely high Ni). |

| Category | Variable | Ai (Assembly Index) of Average Molecule | Ni (Copy Number) of Average Molecule | Total |

GARD Score |

| High Complexity Behavior |

Social Eating | 8 (High) | 8 (High) | 16 | (+1) |

| Outside Eating | 8 (High) | 8 (High) | 16 | (+1) | |

| Low Complexity Behavior |

Distracted Eating | 4 (Low) | 9 (Extremely High) | 13 | (-1) |

| Over-Indulgent Eating | 3 (Very Low) | 9 (Extremely High) | 12 | (-1) |

| Category | Internal Validity in Assembly Theory |

| High Complexity Behavior |

Social eating requires complex social structures, communication, and shared rituals (high Ai). It has been a fundamental aspect of human evolution across cultures and time (high Ni). |

| Eating in dynamic outdoor environments requires physiological adaptation to variable conditions (high Ai). This behavior was the norm for most of human history (high Ni). | |

| Low Complexity Behavior |

Eating while distracted lacks engagement with environmental and social cues, reducing behavioral complexity (low Ai). It is a modern behavior that has become widespread (extremely high Ni). |

| Overeating prioritizes quantity over adaptive responses to hunger and social context, diminishing behavioral complexity (very low Ai). Engineered food environments have made it exceedingly common (extremely high Ni). |

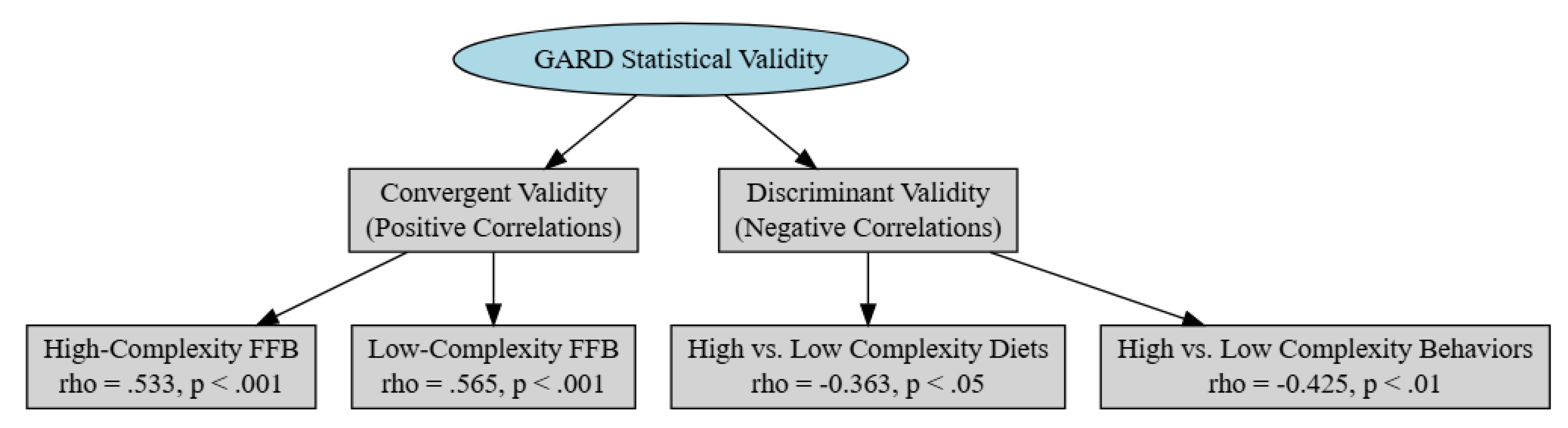

Convergent Validity

Discriminant Validity

External Validity

| NIH: Healthy Meal Planning: Tips for Older Adults | ||

| GARD Score | ||

| Daily Diet (Total GARD score for 3 Meals) |

Store Bought | Farm Bought All Homemade |

| Daily Meal Plan 1 | 16 | 27 |

| Daily Meal Plan 2 | 14 | 22 |

| Daily Meal Plan 3 | 12 | 25 |

| Average | 14 | 23 |

| GARD Score for Daily Mediterranean Diets | ||

| GARD Score | ||

| Daily Diet (Total GARD score for 3 Meals) |

Store Bought | Farm Bought All Homemade |

| Daily Meal Plan 1 | 19 | 27 |

| Daily Meal Plan 2 | 17 | 22 |

| Daily Meal Plan 3 | 7 | 13 |

| Average | 14 | 21 |

| 80% Ultra-Processed Food Diet | ||

| GARD Score | ||

| Daily Diet (Total GARD score for 3 Meals) |

Store Bought | Farm Bought All Homemade |

| Daily Meal Plan 1 | 1 | N/A |

| Daily Meal Plan 2 | -10 | |

| Daily Meal Plan 3 | 1 | |

| Total | -1 | |

| Standard American Diet | ||

| GARD Score | ||

| Daily Diet (Total GARD score for 3 Meals) |

Store Bought | Farm Bought All Homemade |

| Daily Meal Plan 1 | -12 | N/A |

| Daily Meal Plan 2 | -8 | |

| Daily Meal Plan 3 | -9 | |

| Average | -10 | |

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ai | Assembly Index |

| Ni | Copy Number |

| FFB | Food and Food Behavior |

| GARD | Guide Against Age-Related Disease |

| UPF | Ultra-Processed Food |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid |

References

- F. Juul, G. Vaidean, and N. Parekh, “Ultra-processed Foods and Cardiovascular Diseases: Potential Mechanisms of Action,” Adv. Nutr., vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 1673–1680, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A.-D. Termannsen, C. S. Søndergaard, K. Færch, T. H. Andersen, A. Raben, and J. S. Quist, “Effects of Plant-Based Diets on Markers of Insulin Sensitivity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials,” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 13, Art. no. 13, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Seguias and K. Tapper, “The effect of mindful eating on subsequent intake of a high calorie snack,” Appetite, vol. 121, pp. 93–100, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. del C. Fernández-Fígares Jiménez, “A Whole Plant–Foods Diet in the Prevention and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity: From Empirical Evidence to Potential Mechanisms,” J. Am. Nutr. Assoc., vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 137–155, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- “The Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Metabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials in Adults.” Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi. 2072.

- A. Crimarco, M. J. Landry, and C. D. Gardner, “Ultra-processed Foods, Weight Gain, and Co-morbidity Risk,” Curr. Obes. Rep., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 80–92, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Grinshpan, S. Eilat-Adar, D. Ivancovsky-Wajcman, R. Kariv, M. Gillon-Keren, and S. Zelber-Sagi, “Ultra-processed food consumption and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: A systematic review,” JHEP Rep., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 100964, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Tristan Asensi, A. Napoletano, F. Sofi, and M. Dinu, “Low-Grade Inflammation and Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption: A Review,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Song, R. Song, Y. Liu, Z. Wu, and X. Zhang, “Effects of ultra-processed foods on the microbiota-gut-brain axis: The bread-and-butter issue,” Food Res. Int., vol. 167, p. 112730, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Yaroch et al., “Evaluation of Three Short Dietary Instruments to Assess Fruit and Vegetable Intake: The National Cancer Institute’s Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey,” J. Acad. Nutr. Diet., vol. 112, no. 10, pp. 1570–1577, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Barriers and facilitators to undertaking nutritional screening of patients: a systematic review - Green - 2013 - Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jhn. 1201.

- A. Tanweer, S. Khan, F. N. Mustafa, S. Imran, A. Humayun, and Z. Hussain, “Improving dietary data collection tools for better nutritional assessment – A systematic review,” Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update, vol. 2, p. 100067, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Liang, Y. Zhou, Q. Zhang, S. Yu, and S. Wu, “Ultra-processed foods and risk of all-cause mortality: an updated systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies,” Syst. Rev., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 53, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Chae, Y. J. Ju, J. Shin, S.-I. Jang, and E.-C. Park, “Association between eating behaviour and diet quality: eating alone vs. eating with others,” Nutr. J., vol. 17, no. 1, p. 117, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kimura et al., “Eating alone among community-dwelling Japanese elderly: association with depression and food diversity,” J. Nutr. Health Aging, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 728–731, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. V. Matos and R. J. Lopes, “Food System Sustainability Metrics: Policies, Quantification, and the Role of Complexity Sciences,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 22, Art. no. 22, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Bleich, J. Jones-Smith, J. A. Wolfson, X. Zhu, and M. Story, “The Complex Relationship Between Diet And Health,” Health Aff. Proj. Hope, vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 1813–1820, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Compher et al., “Development of the Penn Healthy Diet screener with reference to adult dietary intake data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,” Nutr. J., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 70, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharma, D. Czégel, M. Lachmann, C. P. Kempes, S. I. Walker, and L. Cronin, “Assembly theory explains and quantifies selection and evolution,” Nature, vol. 622, no. 7982, pp. 321–328, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Walker, C. Mathis, S. Marshall, and L. Cronin, “Experimental Measurement of Assembly Indices are Required to Determine The Threshold for Life,” Jun. arXiv:arXiv:2406.06826. [CrossRef]

- M. Jirasek et al., “Investigating and Quantifying Molecular Complexity Using Assembly Theory and Spectroscopy,” ACS Cent. Sci., vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 1054–1064, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Walker, Life as No One Knows It. 2024.

- N. C. Institute, “DNA Synthesis,” Qeios, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Bianconi et al., “An estimation of the number of cells in the human body,” Ann. Hum. Biol., vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 463–471, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lu, Y. C. Chang, Q.-Z. Yin, C. Y. Ng, and W. M. Jackson, “Evidence for direct molecular oxygen production in CO2 photodissociation,” Science, vol. 346, no. 6205, pp. 61–64, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F.-M. Musacchio, “The far ultraviolet aurora of Ganymede,” text.thesis.doctoral, Universität zu Köln, 2016. Accessed: Mar. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.uni-koeln.

- M. M. Lane et al., “Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses,” BMJ, vol. 384, p. e077310, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Astawan and A. P. G. Prayudani, “The Overview of Food Technology to Process Soy Protein Isolate and Its Application toward Food Industry,” in World Nutrition Journal, May 2020, pp. 12–17. [CrossRef]

- M. L. D. C. Louzada et al., “Ultra-processed foods and the nutritional dietary profile in Brazil,” Rev. Saúde Pública, vol. 49, no. 0, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Liu, “Health-Promoting Components of Fruits and Vegetables in the Diet,” Adv. Nutr., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 384S-392S, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Boyer and R. H. Liu, “Apple phytochemicals and their health benefits,” Nutr. J., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 5, May 2004. [CrossRef]

- F. Escalante-Araiza, G. Rivera-Monroy, C. E. Loza-López, and G. Gutiérrez-Salmeán, “The effect of plant-based diets on meta-inflammation and associated cardiometabolic disorders: a review,” Nutr. Rev., vol. 80, no. 9, pp. 2017–2028, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. R. K. Sidhu, C. W. Kok, T. Kunasegaran, and A. Ramadas, “Effect of Plant-Based Diets on Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Interventional Studies,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Peña-Jorquera et al., “Plant-Based Nutrition: Exploring Health Benefits for Atherosclerosis, Chronic Diseases, and Metabolic Syndrome—A Comprehensive Review,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 14, Art. no. 14, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Crerar, “Review: Aquagenesis: The Origin and Evolution of Life in the Sea, by Richard Ellis,” Am. Biol. Teach., vol. 66, no. 8, pp. 579–580, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Bard, “Social Cognition: Evolutionary History of Emotional Engagements with Infants,” Curr. Biol., vol. 19, no. 20, pp. R941–R943, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- “Mechanisms of Social Cognition | Annual Reviews.” Accessed: Mar. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100449.

- G. M. Reséndiz-Benhumea and T. Froese, “Enhanced Neural Complexity is Achieved by Mutually Coordinated Embodied Social Interaction: A State-Space Analysis,” 2020. Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Enhanced-Neural-Complexity-is-Achieved-by-Mutually-Res%C3%A9ndiz-Benhumea-Froese/398560644ae1a4f3da7bbbcb12eb856184c72834.

- C. Tromop-van Dalen, K. Thorne, K. Common, G. Edge, and L. Woods, “Audit to investigate junior doctors’ knowledge of how to administer and score the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),” N. Z. Med. J., vol. 131, no. 1477, pp. 91–108, Jun. 2018.

- S. McGuire, “Todd J.E., Mancino L., Lin B-H. The Impact of Food Away from Home on Adult Diet Quality. ERR-90, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Econ. Res. Serv., February 2010,” Adv. Nutr., vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 442–443, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. Gesteiro, A. García-Carro, R. Aparicio-Ugarriza, and M. González-Gross, “Eating out of Home: Influence on Nutrition, Health, and Policies: A Scoping Review,” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1265, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Lachat, E. Nago, R. Verstraeten, D. Roberfroid, J. Van Camp, and P. Kolsteren, “Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the evidence,” Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 329–346, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. McDonald et al., “American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research,” mSystems, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. e00031-18, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- “Advanced meat preservation methods: A mini review - Rahman - 2018 - Journal of Food Safety - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jfs.12467.

- P. M. da Silva, C. Gauche, L. V. Gonzaga, A. C. O. Costa, and R. Fett, “Honey: Chemical composition, stability and authenticity,” Food Chem., vol. 196, pp. 309–323, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Zabat, W. H. Sano, J. I. Wurster, D. J. Cabral, and P. Belenky, “Microbial Community Analysis of Sauerkraut Fermentation Reveals a Stable and Rapidly Established Community,” Foods, vol. 7, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. D.M and N. M. Bhamidipati, “Citation: Basavarajaiah DM, Narasimhamurhy B (2020) Predictive Modeling of Autophagy Interrelation with Fasting,” J. Biom. Biostat., vol. 5, p. 102, Dec. 2020.

- M. Bagherniya, A. E. Butler, G. E. Barreto, and A. Sahebkar, “The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature,” Ageing Res. Rev., vol. 47, pp. 183–197, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Anton et al., “Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying Health Benefits of Fasting,” Obes. Silver Spring Md, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 254–268, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. I. M. Dunbar, “Breaking Bread: the Functions of Social Eating,” Adapt. Hum. Behav. Physiol., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 198–211, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Outdoor time and dietary patterns in children around the world | Journal of Public Health | Oxford Academic.” Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article/40/4/e493/4978076.

- N. J. Temple, “Refined carbohydrates — A cause of suboptimal nutrient intake,” Med. Hypotheses, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 411–424, Apr. 1983. [CrossRef]

- W. Khalid et al., “Dynamic alterations in protein, sensory, chemical, and oxidative properties occurring in meat during thermal and non-thermal processing techniques: A comprehensive review,” Front. Nutr., vol. 9, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Descalzo et al., “Antioxidant status and odour profile in fresh beef from pasture or grain-fed cattle,” Meat Sci., vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 299–307, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Daley, A. Abbott, P. S. Doyle, G. A. Nader, and S. Larson, “A review of fatty acid profiles and antioxidant content in grass-fed and grain-fed beef,” Nutr. J., vol. 9, p. 10, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Rickman, D. M. Barrett, and C. M. Bruhn, “Nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen and canned fruits and vegetables. Part 1. Vitamins C and B and phenolic compounds,” J. Sci. Food Agric., vol. 87, no. 6, pp. 930–944, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Faustman, Q. Sun, R. Mancini, and S. P. Suman, “Myoglobin and lipid oxidation interactions: mechanistic bases and control,” Meat Sci., vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 86–94, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Monteiro et al., “Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them,” Public Health Nutr., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 936–941, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “The Effects of Distraction on Consumption, Food Preference, and Satiety: A Proposal of Methods - Liguori - 2017 - The FASEB Journal - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://faseb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.957.

- B. J. Rolls, P. M. Cunningham, and H. E. Diktas, “Properties of Ultraprocessed Foods That Can Drive Excess Intake,” Nutr. Today, vol. 55, no. 3, p. 109, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Hall et al., “Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake,” Cell Metab., vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 67-77.e3, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Small and A. G. DiFeliceantonio, “Processed foods and food reward,” Science, vol. 363, no. 6425, pp. 346–347, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. P. McDonald, Test theory: A unified treatment. in Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1999, pp. xi, 485.

- “Healthy Meal Planning: Tips for Older Adults,” National Institute on Aging. Accessed: Mar. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/healthy-eating-nutrition-and-diet/healthy-meal-planning-tips-older-adults.

- I. Castro-Quezada, B. Román-Viñas, and L. Serra-Majem, “The Mediterranean Diet and Nutritional Adequacy: A Review,” Nutrients, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 231–248, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Hess et al., “Dietary Guidelines Meet NOVA: Developing a Menu for A Healthy Dietary Pattern Using Ultra-Processed Foods,” J. Nutr., vol. 153, no. 8, pp. 2472–2481, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Totsch et al., “The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury,” Scand. J. Pain, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 316–324, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Zixuan, “Continuity of Identity: The Sameness of Self from Childhood to Adulthood,” Commun. Humanit. Res., vol. 18, pp. 140–143, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Lalitha, “Phytochemicals and health benefits,” Ann. Geriatr. Educ. Med. Sci., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 29–31. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Anderson et al., “Health benefits of dietary fiber,” Nutr. Rev., vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 188–205, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- “Health benefits of fermented foods: Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition: Vol 59, No 3.” Accessed: Mar. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080/10408398.2017.1383355?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed.

- “Toward an understanding of potato starch structure, function, biosynthesis, and applications - Tong - 2023 - Food Frontiers - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Mar. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://iadns.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/fft2.223.

- J. L. Thomson, A. S. Landry, and T. I. Walls, “Can United States Adults Accurately Assess Their Diet Quality?,” Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 499–506, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. B. Michels, Bloom,Barry R., Riccardi,Paul, Rosner,Bernard A., and W. C. and Willett, “A Study of the Importance of Education and Cost Incentives on Individual Food Choices at the Harvard School of Public Health Cafeteria,” J. Am. Coll. Nutr., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 6–11, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Fulkerson, N. Larson, M. Horning, and D. Neumark-Sztainer, “A Review of Associations Between Family or Shared Meal Frequency and Dietary and Weight Status Outcomes Across the Lifespan,” J. Nutr. Educ. Behav., vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 2–19, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. van Meer, F. de Vos, R. C. J. Hermans, P. A. Peeters, and L. F. van Dillen, “Daily distracted consumption patterns and their relationship with BMI,” Appetite, vol. 176, p. 106136, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Jaeger, “Assembly Theory: What It Does and What It Does Not Do,” J. Mol. Evol., vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 87–92, 2024. [CrossRef]

| High Assembly Index (Ai) and High Copy Number (Ni) | |

| DNA polymerase | Enzyme with a complex structure (high Ai) Replicated billions of times in biology (high Ni) |

| Apples | Biological structure: cells, tissues, proteins, pigments (high Ai) Harvested globally (high Ni) |

| The English Language | Evolved over thousands of years and formed by thousands of words (high Ai) Recreated with little variation globally (high Ni) |

| High Assembly Index (Ai) and Low Copy Number (Ni) | |

| Experimental protein designs | Synthetic designed for a novel function (high Ai) Novel Molecule after first synthesis (low Ni) |

| Hand Crafted Pastry | Complex structure involving multiple layers, fillings, and precise techniques (high Ai) Produced in small batches by artisanal bakers (low Ni) |

| The Word "Alacrity" | Thousands of years of culture to create the word (high Ai) Infrequently used (Low Ai) |

| Low Assembly Index and High Copy Number | |

| Water (H₂O) | Often a biproduct on single step organic reactions (Low Ai) Found universally in high abundance (high Ni) |

| High Fructose Corn Syrup | Fructose molecules refined from a source which initially required <15 steps to assemble the carbohydrate (Low Ai);* Produced globally for sweeteners (high Ni) |

| The Sound of a Rock Falling on Impact | Created by a single step process (low Ai) Occurs universally (high Ni) |

| *Refining does not increase Ai as Ai represents the minimal number of steps needed to build an object using reusable parts. | |

| Low Assembly Index and Low Copy Number | |

| Nitric oxide radical (NO•) | Simple molecule often a biproduct (Low Ai) Reactive and short-lived (Low Ni) |

| Snowball | Formed by aggregation of ice crystals via simple mechanical action (Low Ai) Individually formed and short-lived (Low Ni) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).