Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Modelling Framework

2.1. Three-Region Spatial Equilibrium Model

2.2. Domestic Economic Circulation Equilibrium

2.3. International Economic Circulation Equilibrium

3. Economic Circulation Index Design

3.1. Dual Circulation Pattern

- (1)

- Standardized processing of the initial index data

- (2)

- Calculate entropy and weight

- (3)

- Construct a weighting matrix and determine the optimal solution and the worst solution

- (4)

- Calculate the Euclidean distance between the optimal solution and the worst solution

- (5)

- Calculate relative proximity

- (6)

- Calculate the coupling coordination degree

3.2. “Dual Circulation” Index Measurement Results

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Benchmark Regression

4.2. Robustness Test

5. Further Analysis

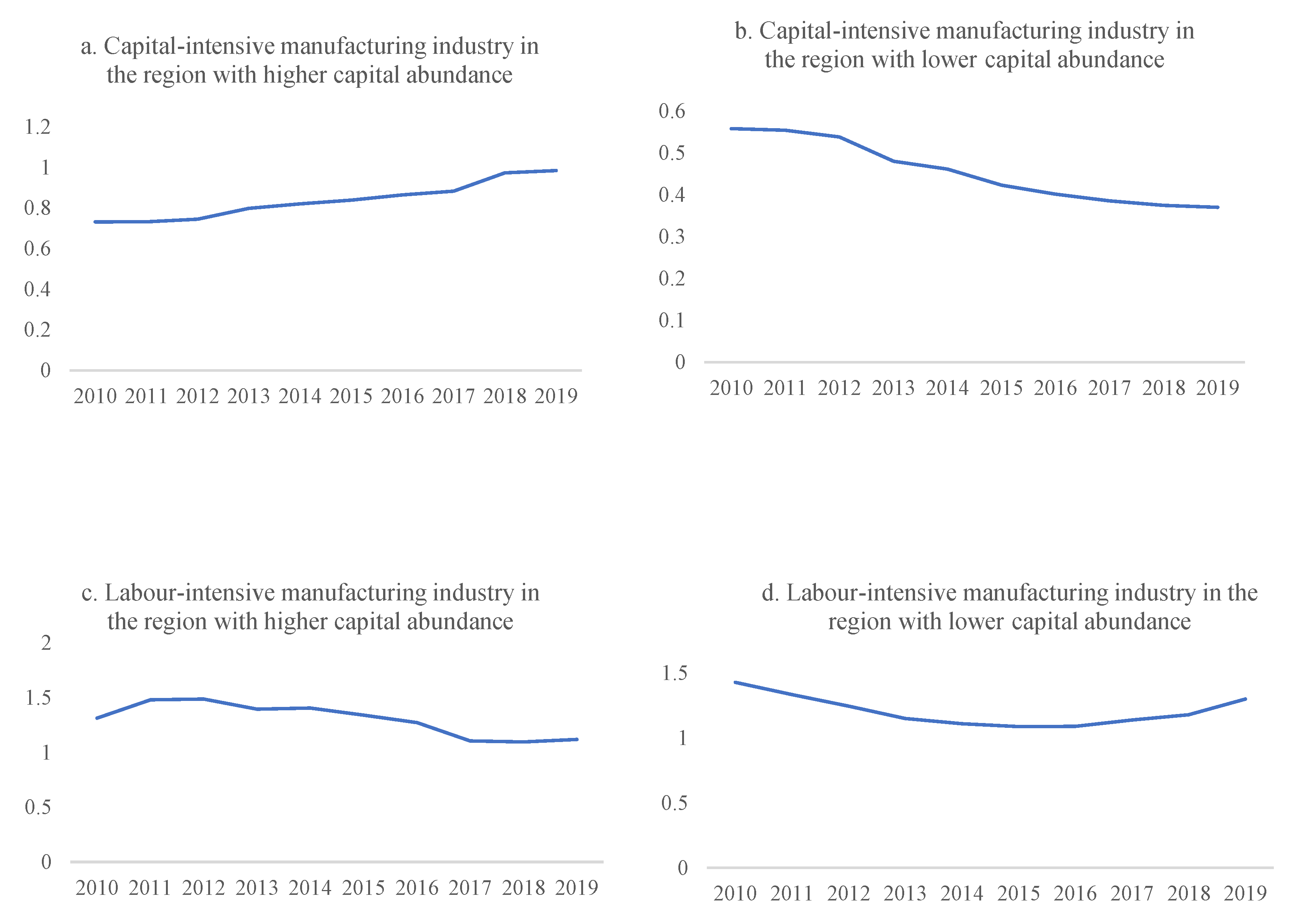

5.1. Domestic Circulation Perspective

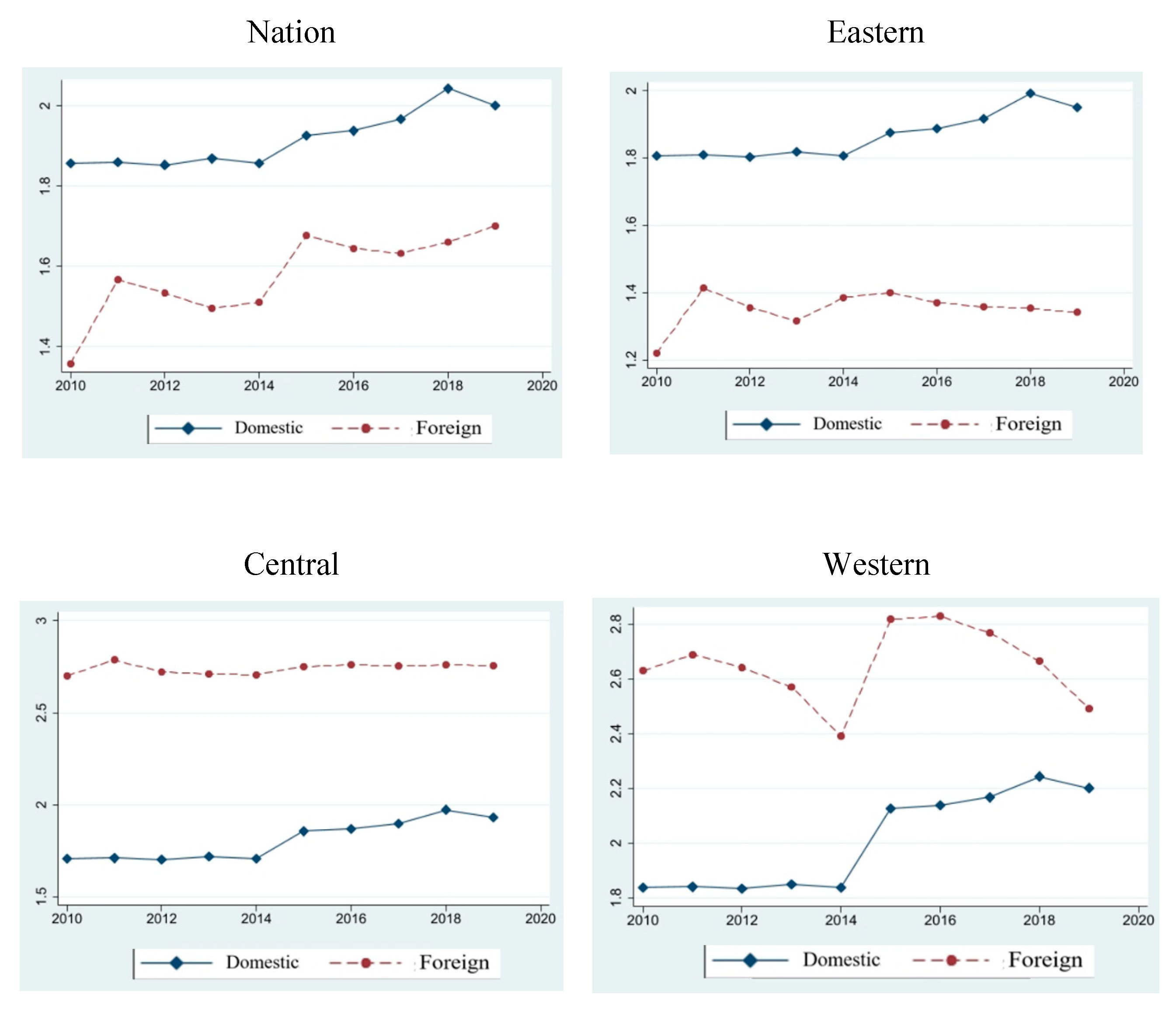

5.2. International Circulation Perspective

6. Conclusions and Implications

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical standard

References

- Fujita M, Krugman P R, Venables A. The spatial economy: Cities, regions, and international trade[M]. MIT press, 2001.

- Ying L, Li M, Yang J. Agglomeration and driving factors of regional innovation space based on intelligent manufacturing and green economy[J]. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 2021, 22: 101398. [CrossRef]

- Gordon I R, McCann P. Innovation, agglomeration, and regional development[J]. Journal of economic Geography, 2005, 5(5): 523-543.

- Yuan H, Zou L, Feng Y, et al. Does manufacturing agglomeration promote or hinder green development efficiency? Evidence from Yangtze River Economic Belt, China[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023, 30(34): 81801-81822. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka A. Inter-regional networks and productive efficiency in Japan[J]. Papers in Regional Science, 2020, 99(1): 115-134.

- Liang L, Wang Z, Li J. The effect of urbanization on environmental pollution in rapidly developing urban agglomerations[J]. Journal of cleaner production, 2019, 237: 117649. [CrossRef]

- Hua C, Abadi B, Miao J. Effect of Agglomeration of Producer Services on Asynchronous Development of Industrialization and Urbanization: Provincial Panel Data of China[J]. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 2024, 150(2): 04024010. [CrossRef]

- Ingebrigtsen S, Jakobsen O D. Circulation economics: theory and practice[M]. Peter Lang, 2007.

- Javed S A, Bo Y, Tao L, et al. The ‘Dual Circulation’ development model of China: Background and insights[J]. Rajagiri Management Journal, 2021, 17(1): 2-20.

- Huang X, Yu P, Song X, et al. Strategic focus study on the new development pattern of ‘dual circulation’ in China under the impact of COVID-19[J]. Transnational Corporations Review, 2022, 14(2): 169-177. [CrossRef]

- Guo K, Tian X. Accelerating the Construction of New Development Pattern and the Paths of Manufacturing Transformation and Upgrading[J]. China Finance and Economic Review, 2022, 11(1): 3-23. [CrossRef]

- Xie F, Gao L, Xie P. Supply-side structural reforms from the perspective of global production networks–based on the theoretical logic and empirical evidence of political economy[J]. China Political Economy, 2020, 3(1): 93-119. [CrossRef]

- Deng H. Trade liberalization, factor distribution and manufacturing agglomeration[J]. Economic Research, 2009,44(11):118-129. (In Chinese).

- Krugman P.R. Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade[J]. American Economic Review, 1980, 70, 950–959.

- Li G, Qin J. Income effect of rural E-commerce: Empirical evidence from Taobao villages in China[J]. Journal of Rural Studies, 2022, 96: 129-140. [CrossRef]

- Gao B Y, W D Liu, Dunford M. State land policy, land markets and geographies of manufacturing: The case of Beijing, China[J]. Land Use Policy, 2014, 36: 1-12.

- Zhao Y, Ni J. The border effects of domestic trade in transitional China: local Governments’ preference and protectionism[J]. The Chinese Economy, 2018, 51(5): 413-431. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Luo Z, Wang Y, et al. Suitability evaluation system for the shallow geothermal energy implementation in region by Entropy Weight Method and TOPSIS method[J]. Renewable Energy, 2022, 184: 564-576. [CrossRef]

- Gibson J, Olivia S, Boe-Gibson G. Night lights in economics: Sources and uses [J]. Journal of Economic Surveys, 2020, 34(5): 955-980.

- Davis D R. and D E Weinstein. Market access, economic geography and comparative advantage: an empirical test[J]. Journal of International Economics, 2003, 59(1): 1-23.

- Holmes T J and J J Stevens. Does home market size matter for the pattern of trade? [J]. Journal of International Economics, 2005, 65(2): 489-505. [CrossRef]

- Long X, Yu H, Sun M, et al. Sustainability evaluation based on the Three-dimensional Ecological Footprint and Human Development Index: A case study on the four island regions in China[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2020, 265: 110509. [CrossRef]

- Grossman G M, Oberfield E. The elusive explanation for the declining labor share[J]. Annual Review of Economics, 2022, 14: 93-124.

- Yang N, Hong J, Wang H, et al. Global value chain, industrial agglomeration and innovation performance in developing countries: Insights from China’s manufacturing industries[J]. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 2020, 32(11): 1307-1321. [CrossRef]

- Rousslang D J, To T. Domestic trade and transportation costs as barriers to international trade[J]. Canadian Journal of Economics, 1993: 208-221.

- Bian Y, Song K, Bai J. Market segmentation, resource misallocation and environmental pollution[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 228: 376-387. [CrossRef]

- Head K. and J. Ries. Increasing returns versus national product differentiation as an explanation for the pattern of US–Canada trade[J]. American Economic Review, 2001, 91(4): 858-876. [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano G., T. Tabuchi T and J.F. Thisse. Agglomeration and trade revisited[J]. International economic review, 2002: 409-435.

- Zhang S, Wang Z, Jin Z. The Economic Growth Effect of Dual Circulation[J]. The Journal of Quantitative & Technical Economics, 2022,39(11):5-26. (In Chinese).

- Melitz M.J. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity[J]. Econometrica, 2003, 71(6): 1695-1725. [CrossRef]

- Koenig P., F. Mayneris and S. Poncet. Local export spillovers in France[J]. European Economic Review, 2010, 54(4): 622-641. [CrossRef]

- Forte R P, Sá A R. The role of firm location and agglomeration economies on export propensity: the case of Portuguese SMEs[J]. EuroMed Journal of Business, 2021, 16(2): 195-217.

- Lin H L, Li H Y, Yang C H. Agglomeration and productivity: Firm-level evidence from China’s textile industry[J]. China Economic Review, 2011, 22(3): 313-329.

| First grade | Second grade | Third grade | Indicator description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Circulation | Intra-Province Circulation | Consumption | Consumption level | Consumption expenditure per capita / GDP per capita |

| Consumption structure | Immaterial consumption / Disposable income | |||

| Production | Production scale | Aggregate fixed investment /GDP | ||

| Production efficiency | Average productivity | |||

| Transportation | Logistics transportation | Transportation, warehousing, postal value added / GDP | ||

| Commodity turnover | Total retail sales / GDP | |||

| Distribution | Income distribution | Disposable income per capita / GDP per capita | ||

| Consumption investment balance | Overall payout / Aggregate fixed investment | |||

| Inter-Province Circulation | Integration | Domestic trade cost | Relative price index | |

| International Circulation | Trade | Trade balance | Net export / Total export-import volume | |

| Trade upgrading | High-tech industry introduction expenditure / Total export-import volume | |||

| Investment | FDI | FDI/GDP | ||

| OFDI | OFDI/GDP | |||

| Rank | dual circulation index | Domestic circulation | International circulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beijing | 0.707 | Beijing | 0.894 | Hainan | 0.547 |

| 2 | Shanghai | 0.606 | Shanghai | 0.737 | Tianjin | 0.438 |

| 3 | Tianjin | 0.498 | Guangdong | 0.587 | Shanghai | 0.401 |

| 4 | Guangdong | 0.455 | Tianjin | 0.513 | Sichuan | 0.374 |

| 5 | Liaoning | 0.365 | Zhejiang | 0.478 | Beijing | 0.354 |

| 6 | Jiangsu | 0.364 | Liaoning | 0.418 | Chongqing | 0.351 |

| 7 | Zhejiang | 0.352 | Jiangsu | 0.415 | Shaanxi | 0.330 |

| 8 | Shandong | 0.336 | Shandong | 0.365 | Shanxi | 0.265 |

| 9 | Hainan | 0.323 | Fujian | 0.319 | Anhui | 0.260 |

| 10 | Sichuan | 0.305 | Heilongjiang | 0.310 | Jiangsu | 0.255 |

| 11 | Chongqing | 0.293 | Hebei | 0.294 | Hubei | 0.249 |

| 12 | Hubei | 0.281 | Inner Mongolia | 0.288 | Shandong | 0.244 |

| 13 | Anhui | 0.278 | Hubei | 0.284 | Guangdong | 0.234 |

| 14 | Fujian | 0.274 | Hunan | 0.281 | Guangxi | 0.231 |

| 15 | Shaanxi | 0.268 | Anhui | 0.274 | Guizhou | 0.226 |

| 16 | Guangxi | 0.265 | Guangxi | 0.263 | Zhejiang | 0.214 |

| 17 | Heilongjiang | 0.264 | Gansu | 0.262 | Liaoning | 0.210 |

| 18 | Hunan | 0.263 | Ningxia | 0.253 | Jiangxi | 0.199 |

| 19 | Hebei | 0.254 | Jilin | 0.253 | Hunan | 0.195 |

| 20 | Inner Mongolia | 0.254 | Jiangxi | 0.239 | Jilin | 0.192 |

| 21 | Gansu | 0.245 | Chongqing | 0.224 | Gansu | 0.184 |

| 22 | Henan | 0.244 | Yunnan | 0.217 | Fujian | 0.169 |

| 23 | Jilin | 0.242 | Sichuan | 0.212 | Ningxia | 0.166 |

| 24 | Shanxi | 0.242 | Shanxi | 0.211 | Henan | 0.160 |

| 25 | Jiangxi | 0.234 | Qinghai | 0.208 | Yunnan | 0.158 |

| 26 | Ningxia | 0.229 | Guizhou | 0.206 | Hebei | 0.141 |

| 27 | Guizhou | 0.221 | Xinjiang | 0.187 | Inner Mongolia | 0.139 |

| 28 | Yunnan | 0.205 | Henan | 0.186 | Qinghai | 0.101 |

| 29 | Qinghai | 0.184 | Shaanxi | 0.182 | Heilongjiang | 0.096 |

| 30 | Xinjiang | 0.162 | Hainan | 0.169 | Xinjiang | 0.074 |

| DCI (Domestic weight 0.5) | DCI (Domestic weight 0.6) | DCI (Domestic weight 0.7) | DCI (Domestic weight 0.8) | DCI (Domestic weight 0.9) | Domestic circulation | International circulation | |

| Agg | 0.0116* (0.0067) |

0.0137** (0.0062) |

0.0201*** (0.0054) |

0.0214** (0.0102) |

0.0280** (0.0112) |

0.0177*** (0.0033) |

0.0025 (0.0208) |

| CV | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual Fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 |

| R2 | 0.3446 | 0.4989 | 0.5965 | 0.5367 | 0.3728 | 0.3672 | 0.3765 |

| IV-2SLS(IV: topographic relief) | IV-2SLS(IV: river density) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Stage | 0.7881*** (0.0022) |

0.6921*** (0.0004) |

||||

| F-value | 101.78 | 985.22 | ||||

| Second Stage | DCI | Domestic | International | DCI | Domestic | International |

| Agg | 0.0226*** (0.0036) |

0.0182*** (0.0009) |

-0.0015 (0.1217) |

0.0260** (0.0065) |

0.0191*** (0.0021) |

-0.0028 (0.2768) |

| CV | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Region | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Obs. | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 |

| R2 | 0.4036 | 0.4345 | 0.3575 | 0.3867 | 0.4708 | 0.4090 |

| Domestic circulation | ||||

| (1) Aggku | (2) Aggkd | (3) Agglu | (4) Aggld | |

| 0.0180*** (0.0005) |

0.0093* (0.065) |

0.0184*** (0.0015) |

0.0097*** (0.0009) |

|

| CV | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.5581 | 0.5172 | 0.4618 | 0.3713 |

| Intra-Province circulation | ||||

| (1) Aggku | (2) Aggkd | (3) Agglu | (4) Aggld | |

| 0.0178*** (0.0027) |

-0.0048 (0.0295) |

0.0180*** (0.0007) |

0.0134** (0.0051) |

|

| CV | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.5396 | 0.4877 | 0.5145 | 0.3886 |

| Inter-Province circulation | ||||

| (1) Aggku | (2) Aggkd | (3) Agglu | (4) Aggld | |

| 0.0104*** (0.0021) |

0.0086** (0.0034) |

0.0272 (0.0415) |

0.0095* (0.0058) |

|

| CV | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.5511 | 0.5221 | 0.4716 | 0.4339 |

| Industry | Capital-output elasticity | Labour-output elasticity | Elasticity of returns to scale | Ratio of export delivery value to output value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural and sideline food processing industry | 0.7566 | 0.2083 | 0.9649 | 4.90 |

| Food manufacturing industry | 0.6211 | 0.9771 | 1.5982 | 5.60 |

| Wine, beverage and refined tea manufacturing industry | 0.7227 | 0.5597 | 1.2824 | 1.60 |

| Tobacco products industry | 0.9404 | 0.1078 | 1.0482 | 0.45 |

| Textile industry | 1.1758 | 0.4210 | 1.5968 | 11.42 |

| Textile and clothing, clothing industry | 0.7329 | 0.3010 | 1.0339 | 23.36 |

| Leather, fur, feathers and their products and footwear | 0.8151 | 0.4783 | 1.2934 | 25.67 |

| Wood processing and wood, bamboo, rattan, brown, grass products industry | 0.8400 | 0.1888 | 1.0288 | 6.72 |

| Furniture manufacturing | 0.7544 | 0.5034 | 1.2578 | 23.05 |

| Papermaking and paper products industry | 0.9477 | 0.1376 | 1.0853 | 4.54 |

| Printing and Recording Media Reproduction | 1.0719 | 0.1885 | 1.2604 | 7.20 |

| Cultural and educational, industrial, sports and entertainment products manufacturing industry | 0.6857 | 1.0514 | 1.7371 | 32.43 |

| Petroleum processing, coking and nuclear fuel processing industries | 0.4022 | 0.1421 | 0.5443 | 1.76 |

| Chemical raw materials and chemical products manufacturing | 0.7082 | 0.6781 | 1.3863 | 5.59 |

| Pharmaceutical manufacturing industry | 0.5190 | 1.2212 | 1.7402 | 6.15 |

| Chemical fiber manufacturing industry | 0.6043 | 0.6269 | 1.2312 | 6.77 |

| Rubber and plastic products industry | 0.7007 | 0.4125 | 1.1132 | 13.82 |

| Non-metallic mineral products industry | 0.8154 | 0.5396 | 1.355 | 3.60 |

| Ferrous metal smelting and rolling processing industry | 0.3229 | 0.0893 | 0.4122 | 3.34 |

| Non-ferrous metal smelting and rolling processing industry | 0.7656 | 0.4437 | 1.2093 | 2.61 |

| Metal products industry | 0.7131 | 0.9239 | 1.637 | 10.99 |

| General equipment manufacturing industry | 0.4609 | 0.4406 | 0.9015 | 11.35 |

| Special equipment manufacturing industry | 0.5770 | 0.8350 | 1.412 | 9.45 |

| Transportation equipment manufacturing industry | 1.4134 | 0.0199 | 1.4333 | 8.61 |

| Electrical machinery and equipment manufacturing industry | 0.7430 | 0.5136 | 1.2566 | 16.11 |

| Computer, communications and other electronic equipment manufacturing | 0.6578 | 1.2625 | 1.9203 | 54.06 |

| Instrument and meter manufacturing industry | 0.7881 | 0.2708 | 1.0589 | 18.34 |

| Manufacturing average | 0.7502 | 0.5016 | 1.2518 | 11.83 |

| 1 | In fact, in the short-term equilibrium, due to the difference between the first nature and the second nature, there may be differences in the rate of return on capital and labor remuneration between region 1 and region 2, while in the long-term equilibrium, the rate of return on capital and labor remuneration will return to the same level. At this time, the employment of labor force in region 1 or region 2 can be regarded as undifferentiated, so the model setting does not restrict the flow of labor force between domestic regions in the long-term equilibrium. |

| 2 | In the process of solving, in order to make the form of the wage equation as simple as possible, the marginal cost of production , and the fixed cost are set. |

| 3 | Due to symmetry, near the equilibrium point, the total differential of the related expressions of region 1 and region 2 can be combined and abbreviated, and the corner markers 1 and 2 are omitted here. |

| 4 | Similarly, the total differential abbreviation omits the corner mark due to symmetry. In order to simplify the analysis, it is assumed that the transportation costs of Region 1 and 2 are equal, that is, τ12 = τ21, and expressed by τ. |

| 5 | The capital-intensive industries in this paper include chemical raw materials and chemical products manufacturing industry, other non-metallic minerals, mechanical and electrical industry, transportation equipment industry, water transportation industry, support and auxiliary transportation activity industry, and the remaining manufacturing sub-sectors are labor-intensive. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).