Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Active Mobility Promotion Measures

2.2. Economic Appraisal of Active Mobility

2.3. Research Gaps

2.4. Justification for Using Contingent Valuation Method (CVM)

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area Justification

3.2. Research Design

3.2.1. Measure Selection Process

3.2.2. Survey Instrument

- P(Yes) = Probability of a respondent accepting the bid

- α = Constant term

- β = Coefficient of the bid amount (expected to be negative)

- B = Bid amount presented to respondent

- γ = Vector of coefficients for explanatory variables

- X = Vector of respondent characteristics (e.g., income, gender, travel behavior)

3.2.3. Sampling

3.2.4. Questionnaire Design

3.2.5. Measure Selection

| Domain | Measure | Description | Source |

| Physical Infrastructure | Separate | Separation of pedestrian and bicycle lanes | SWOT, Pucher & Buehler (2008) |

| Architecture | Beautiful architectural design (e.g., landmarks) | Qualitative interviews | |

| Roof | Pedestrian covered walkways | UddC (2015) | |

| Safety/Security | Motor Protection | Barriers to prevent motorcycles on sidewalks | SWOT, Pongphonrat et al. (2015) |

| CCTV | CCTV in high-risk areas | Qualitative interviews | |

| Safe Crossing | Clear crossings with safety technology | Sansanee Sangsila (2012) | |

| Amenities | Rest Area | Rest areas along paths | SWOT, Methorst et al. (2010) |

| Water Station | Drinking water points | Qualitative interviews | |

| Bicycle Parking | Sufficient bicycle parking | Bordagaray et al. (2015) | |

| Promotion | Promote | Offline/online media campaigns | Qualitative interviews |

| Application | AM information apps | Literature review | |

| Policy | Public Tran | Public transport integration | Pucher & Buehler (2008) |

| Service Centre | Violation notification centres | Qualitative interviews |

3.3. Econometric Analysis

- P = probability of WTP for a given measure

- Xₙ = independent variables (e.g., gender, age, income, distance to campus, travel habits, motivation for AM)

- βₙ = estimated coefficients interpreted as odds ratios (Exp(B))

3.4. Social Benefit Estimation

4. Results and Discussion

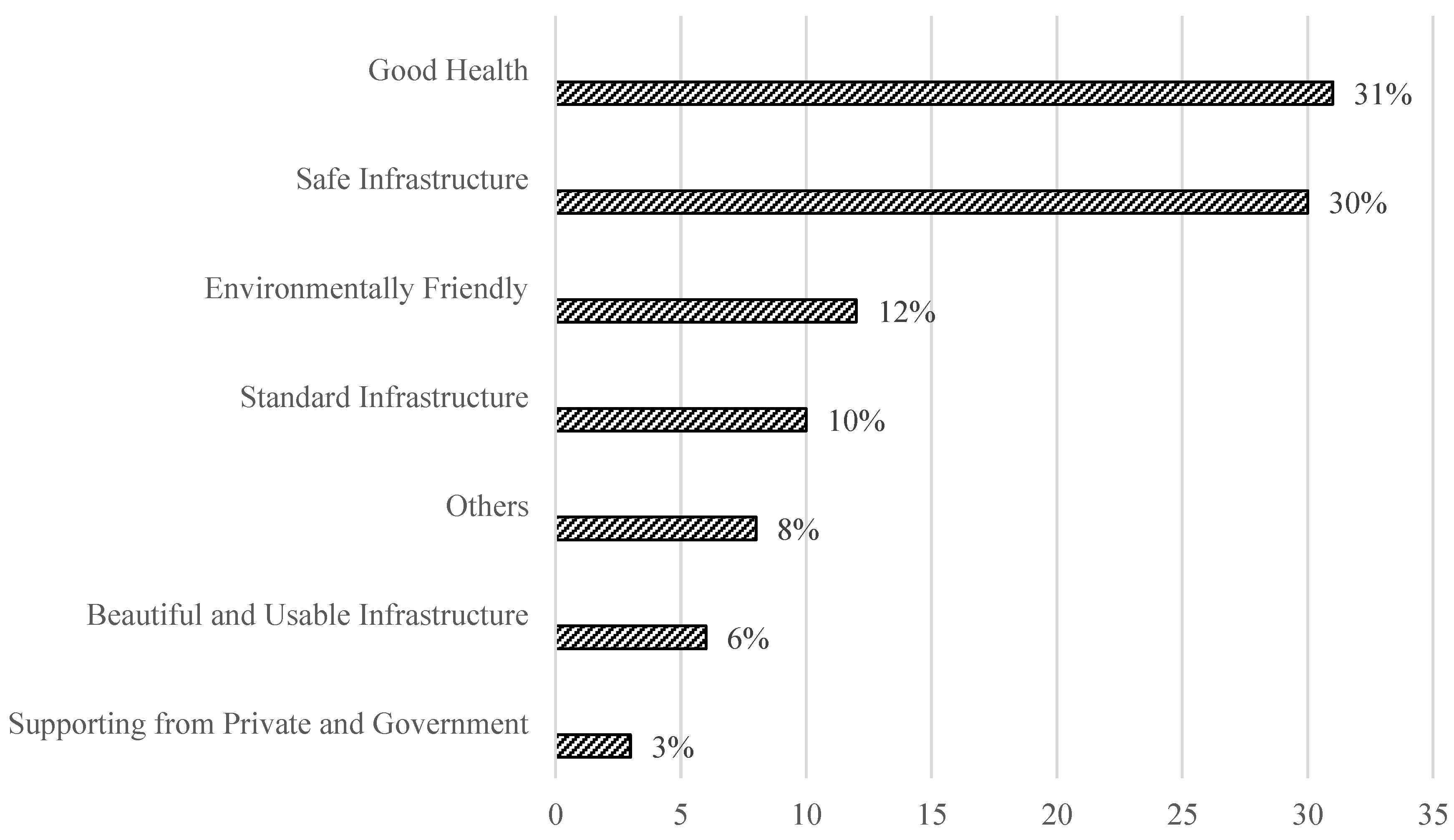

4.1. Qualitative Findings: SWOT Analysis

4.2. Quantitative Findings: Respondent Characteristics

4.3. Binary Logistic Regression Results

- Demographics: Males were less likely to switch to AM (OR=0.512, p=0.096), possibly due to cultural preferences for motorized transport. Higher-income groups (15,001–20,000 THB) were 88.6% less likely to switch (OR=0.114, p=0.004) compared to the <10,000 THB reference group.

- Travel Behaviour: Higher daily travel costs increased AM likelihood slightly (OR=1.008, p=0.044). Motorcycle (OR=0.171, p=0.002) and car users (OR=0.136, p=0.004) were significantly less likely to switch compared to walkers/cyclists.

- Infrastructure: Beautiful architectural design (OR=1.695, p=0.045), rest areas (OR=1.820, p=0.034), CCTV (OR=1.726, p=0.060), protective barriers (OR=1.608, p=0.086), and safe crossings (OR=1.650, p=0.056) increased AM likelihood. Public transport integration was highly influential (OR=2.192, p=0.005).

- Promotion: Media campaigns (OR=0.576, p=0.039) and AM apps (OR=0.583, p=0.038) negatively affected AM adoption, suggesting infrastructure priorities over promotion.

5. Conclusion

Policy Recommendations

- Infrastructure First: Invest in rest areas, CCTV, and protective barriers before launching promotional campaigns.

- Integrate Public Transport: Strengthen first/last-mile connections with trams or bike-sharing.

- Targeted Campaigns: Tailor campaigns to address gender and cultural attitudes, particularly focusing on normalizing AM among males.

- Pilot and Scale: Test interventions at KMITL with pre/post evaluation and expand to other Thai campuses.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Alton, D., Adab, P., Roberts, L., & Barrett, T. (2007). Relationship between walking levels and perceptions of the local neighborhood environment. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92(1), 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, I. J., Carson, R. T., Day, B., Hanemann, W. M., Hanley, N., Hett, T., ... & Watson, S. (2002). Economic valuation with stated preference techniques: A manual. Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bejranonda, S., & Attanandana, V. (2015). Willingness to pay for attributes of cycleway management. Kasetsart Journal - Social Sciences, 36, 201–216.

- Beirão, G., & Sarsfield Cabral, J. A. (2007). Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: A qualitative study. Transport Policy, 14(6), 478–489. [CrossRef]

- Benjasiri, R. (2015). Social return on investment of skywalk in Bangkok. Journal of Politics, Administration and Law.

- Boon-or, N., & Limpasenee, W. (2020). Sidewalk development for convenient Bangkok metropolitan. Vajira Medical Journal, 64(3).

- Boone-Heinonen, J., Evenson, K. R., Taber, D. R., & Gordon-Larsen, P. (2009). Walking for prevention of cardiovascular disease in men and women: A systematic review of observational studies. Obesity Reviews, 10(2), 204–217. [CrossRef]

- Bordagaray, M., de Oña, J., & de Oña, R. (2015). Active commuting to university: Attitudes and perceptions of university students. Journal of Transport Geography, 48, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Bordagaray, M., Dell’Olio, L., Ibeas, A., Barreda, R., & Alonso, B. (2015). Modeling the service quality of public bicycle schemes considering user heterogeneity. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 9(8), 580–591. [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R., Sarmiento, O. L., Jacoby, E., Gomez, L. F., & Neiman, A. (2009). Influences of built environments on walking and cycling: Lessons from Bogotá. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 3(4), 203–226. [CrossRef]

- Chakrat Phala, & Monsicha Petchanon. (2016). An investigation of cycling behavior for bike use policy in Khon Kaen City. Academic Journal: Faculty of Architecture, Khon Kaen University, 15(2), 113–116.

- Clark, A., & Stigell, E. (2017). Active mobility and physical activity - results from the pan-European PASTA project. European Journal of Public Health, 27(3). [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. (2017). Behavioral economics and its application to travel behavior research. Transportation Research Board.

- Clark, J., & Stigell, E. (2017). Walking, cycling, and public transport: A review of interventions to promote active commuting. Journal of Transport & Health, 6, 156–166. [CrossRef]

- Cortright, J. (2009). Walking the walk: How walkability raises home values in U.S. cities. CEOs for Cities.

- Easton, S., & Ferrari, E. (2015). Children’s travel to school—the interaction of individual, neighborhood and school factors. Transport Policy, 44, 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Engels, F., Wentland, A., & Pfotenhauer, S. M. (2019). Testing future societies? Developing a framework for test beds and living labs as instruments of innovation governance. Research Policy, 48(9), 103826. [CrossRef]

- Erlichman, J., Kerbey, A. L., & James, W. P. (2002). Physical activity and its impact on health outcomes. Paper 2: Prevention of unhealthy weight gain and obesity by physical activity: An analysis of the evidence. Obesity Reviews, 3(4), 273–287. [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, W. M. (1994). Valuing the environment through contingent valuation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(4), 19–43. [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed.). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Hume, C., Jorna, M., Arundell, L., Saunders, J., Crawford, D., & Salmon, J. (2009). Are children’s perceptions of neighborhood social environments associated with their walking and physical activity? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 12(6), 637–641. [CrossRef]

- Ibeas, Á., Cordera, R., dell’Olio, L., & Coppola, P. (2011). Pedestrian route choice models: A literature review. Transport Reviews, 31(5), 629–644. [CrossRef]

- Iii, M. P., Herriges, J. A., & Kling, C. L. (2003). The measurement of environmental and resource values: Theory and methods (2nd ed.). Resources for the Future. [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. F., & Eaton, C. B. (1994). Cost-benefit analysis of walking to prevent coronary heart disease. Archives of Family Medicine, 3(8), 703–710. [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapa Pongphonrat, Rattanatavorn, N., & Limpasenee, W. (2015). Attitudes towards walking and cycling in Chiang Mai. Journal of Transport Research Forum, 49(2), 1–18.

- Kemperman, A., & Timmermans, H. (2014). Environmental correlates of active travel behavior of children. Environment and Behavior, 46(5), 583–608. [CrossRef]

- Koh, P. P., & Wong, Y. D. (2013). Singapore’s approach to promoting walking and cycling. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 58, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Krizek, K. J., Handy, S. L., & Forsyth, A. (2009). Explaining changes in walking and bicycling behavior: Challenges for transportation research. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 36(4), 725–740. [CrossRef]

- Kusuma Thavorn, Chaisongkram, P., & Promsuwan, S. (2014). The participatory action research in cycling way of life among town people: A case study of Phanatnikhom municipality, Chonburi Province. Thailand Cycling Club.

- Lewicka, M. (2005). Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25(4), 381–395. [CrossRef]

- Meesit, R., Puntoomjinda, S., Chaturabong, P., Sontikul, S., & Arunnapa, S. (2023). Factors affecting travel behaviour change towards active mobility: A case study in a Thai university. Sustainability, 15(14), 11393. [CrossRef]

- Methorst, R., Bort, H. M., Risser, R., Sauter, D., Tight, M., & Walker, J. (2010). Pedestrian’s quality needs promotion, COST 358 final report part C executive summary. Walk 21, Cheltenham, UK.

- Morris, J. N., & Hardman, A. E. (1997). Walking to health. Sports Medicine, 23(5), 306–332. [CrossRef]

- Morse, J. M. (2004). Theoretical saturation. In M. S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. F. Liao (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods (pp. 1123–1124). SAGE Publications.

- Ogilvie, D., Foster, C. E., Rothnie, H., Cavill, N., Hamilton, V., Fitzsimons, C. F., & Mutrie, N. (2007). Interventions to promote walking: Systematic review. BMJ, 334(7605), 1204. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395. [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J., & Buehler, R. (2008). Making cycling irresistible: Lessons from The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transport Reviews, 28(4), 495–528. [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J., & Buehler, R. (2010). Cycling (and walking) in the USA: Recent trends and policies. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(5), 681–694. [CrossRef]

- Punyanuch Ruthirako, Promsuwan, S., & Chaisongkram, P. (2019). Action research of creating a friendly city toward walking and biking: A case study of Na-Thawi municipality, Na-Thawi, Songkhla. The 7th Thailand Bike and Walk Forum, 70–81.

- Rabl, A., & de Nazelle, A. (2012). Benefits of shift from car to active transport. Transport Policy, 19(1), 121–131. [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B. E., & Handy, S. L. (2008). Built environment correlates of walking: A review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40(7 Suppl), S550–S566. [CrossRef]

- Sælensminde, K. (2004). Cost–benefit analyses of walking and cycling track networks taking into account insecurity, health effects and external costs of motorized traffic. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 38(8), 593–606. [CrossRef]

- Sansanee Sangsila. (2012). The pedestrian behavior of community around mass rapid transit station. (Master’s thesis, Silpakorn University).

- Sohn, D. W., Moudon, A. V., & Lee, J. (2012). The economic value of walkable neighborhoods. Urban Design International, 17(2), 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Chen, R., & Wu, X. (2013). Walking and cycling for healthy urban environments: A case study of Beijing, China. Urban Studies, 50(14), 2821–2838. [CrossRef]

- Sriprasong, P. (2010). Willingness-to-pay for and factor determination of flood-prevent tax in Bangkok by Pasak Jolasid Dam. Srinakharinwirot University.

- Sukharom, R. (1998). Hypothetical scenarios for evaluating non-market goods. Thammasat Economic Journal, 16(4), 89–117.

- UddC (Urban Design and Development Center). (2015). Today, tomorrow, and the future and the barriers to pedestrians in Bangkok. Project to study the potential of access to public utilities that promote walking and the walking potential index study project, Phase 1. Chulalongkorn University.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations General Assembly. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- Wang, G., Macera, C. A., Scudder-Soucie, B., Schmid, T., Pratt, M., Buchner, D., & Heath, G. (2004). Cost analysis of the built environment: The case of bike and pedestrian trials in Lincoln, Neb. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 549–553. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.-A., Giles-Corti, B., & Turrell, G. (2012). The association between objectively measured neighbourhood features and walking for transport in mid-aged adults. Local Environment, 17(2), 131–146. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global status report on road safety 2021. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027114.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Health economic assessment tool (HEAT) for walking and cycling. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/tools/health-economic-assessment-tool--heat-for-walking-and-cycling.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper & Row.

| Strength | Weakness | Opportunity | Threat |

| Exercise benefits | Hot weather | Prevent motorcycle encroachment | Improper motorcycle behaviour |

| Cost savings | Long travel times | Smoother road surfaces | Bad road surfaces |

| Enjoy surroundings | Insufficient sidewalk width | Adequate lighting | Waterlogging |

| Insufficient lighting |

| Strength | Weakness | Opportunity | Threat |

| Exercise benefits | Skirt-wearing challenges | Prevent motorcycle encroachment | Improper motorcycle behaviour |

| Faster than walking | Small headlight/taillight | Bicycle-sharing system | Poor road sharing |

| Inadequate bicycle lanes | Improved bicycle lanes |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Median |

| SECTION 1: DEMOGRAPHIC QUESTIONS | ||||||

| Gender (0=Male, 1=Female) | 400 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Age | 400 | 23.6 | 7.53 | 17 | 70 | 21 |

| Marital Status | 400 | 1.14 | 0.46 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Education Level | 400 | 3.86 | 0.62 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Career | 400 | 1.39 | 0.91 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Income | 400 | 2.03 | 1.16 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Bicycle Ownership | 400 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Distance to University (km) | 400 | 7.47 | 10.1 | 0 | 80 | 2 |

| Travel Cost | 400 | 45.9 | 66.5 | 0 | 500 | 20 |

| Frequent Mode of Transport | 400 | 2.55 | 1.2 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Daily Distance for Walking or Cycling | 400 | 2.02 | 1.01 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Factors Influencing Transport Choice | 400 | 4.23 | 1.81 | 1 | 7 | 4 |

| Intention to Switch to Active Mobility | 400 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| SECTION 2: ACTIVE MOBILITY FACTOR QUESTIONS | ||||||

| Separation of Pedestrian and Bicycle Lanes | 400 | 3.91 | 1.16 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Planting Around the Pedestrian and Bicycle Lanes | 400 | 3.59 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Architectural Design | 400 | 3.65 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Protection Against Motorcycle Incursions | 400 | 3.91 | 1.17 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| CCTV for Security | 400 | 4.02 | 1.06 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Security Checkpoints | 400 | 3.69 | 1.11 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Emergency Communication Devices | 400 | 3.67 | 1.12 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Safe Crossings and Intersections | 400 | 4.04 | 1.08 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Covered Walkways for Pedestrians | 400 | 3.88 | 11.7 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Sufficient Lighting at the Pedestrian and Bicycle Lanes at Night | 400 | 4.09 | 1.1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Sufficient and Suitable Bins | 400 | 3.85 | 1.1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Road Signs and Maps for Pedestrian and Bicycle Lane | 400 | 3.77 | 1.12 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Outdoor Workout Equipment | 400 | 3.27 | 1.11 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Rest Areas | 400 | 3.73 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Sufficient Bicycle Parking | 400 | 3.74 | 1.14 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| A Service Point for Borrowing and Returning Bicycles Within the Institution’s Area | 400 | 3.62 | 1.08 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Shower Spot and Lockers | 400 | 3.26 | 1.13 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Drinking Water Service Points | 400 | 3.58 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| The Connection Point between Other Public Transport and Pedestrian or Bicycle Lanes | 400 | 3.73 | 1.06 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Pedestrian and Bicycle Lanes are Interconnected to Cover the Area | 400 | 3.84 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Promotion Through Offline and Online Media | 400 | 3.48 | 1.08 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Cleaning and Maintenance of Sidewalks and Bicycle Paths | 400 | 3.94 | 1.1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Notification of Violation of the Use of Pedestrian and Bicycle Lane | 400 | 3.81 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Using the Area Around the Pedestrian and Bicycle Lanes to Organize Activities | 400 | 3.38 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Application to Provide Information and News About Walking and Cycling | 400 | 3.46 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Policy to Promote Walking or Bicycle by Giving Prizes or Charitable Donations | 400 | 3.40 | 1.13 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Pedestrian and Bicycle Photography or Video Contests | 400 | 3.26 | 1.15 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Walk or Bicycle Day Activities | 400 | 3.32 | 1.23 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Educating and Organizing Training on Safety Use of Pedestrian and Bicycle Lanes | 400 | 3.49 | 1.08 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Encouraging to Travel by Public Transport | 400 | 3.74 | 1.01 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Participation of Students or Staff in Presenting the Design of the Pedestrian or Bicycle Lanes Within the Institute | 400 | 3.57 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Determining Policies on Improving and Building Pedestrian on Campus | 400 | 3.83 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Gen | Gender (0= male, 1= female) |

| Age | Age (year) |

| Status | Status (1= single, 2= married, 3= divorce, 4= others) |

| Edu | Education level (1= primary, 2=secondary, 3= diploma, 4= bachelor, 5= upper bachelor) |

| Career | Career (1= student, 2= staff, 3= lecturer, 4= merchant/personal business) |

| Income | Income (1= <10,000, 2= 10,000-15,000, 3= 15,001-20,000, 4= 20,001-25,000, 5=>25,000 |

| Bicycle | The bicycle occupancy (yes: 1, no: 0) |

| Distance | In a typical day, what is the distance between your accommodation and university? (km) |

| TraCost | Travel cost (1= 0, 2= <20 bath, 3= <50 bath, 4= <150 bath, 5= >150 bath) |

| TraMode | Frequent mode of transport (1=walk, 2= bicycle, 3= motorcycle, 4= car, 5= others) |

| ActDistance | In a typical day, how many kilometers do you spend for walking or cycling? (1= <1 km, 2= 1-2 km, 3= 2-3 km, 4= >3 km |

| FutureTravBeh | If there is a development in walking and cycling infrastructure, are you going to switch the mode of transport to walking and cycling (0= yes, 1= no) |

| Separate | Separation of pedestrian and bicycle lanes (1=least significant, 2=less significant, 3=moderate significant, 4=significant, 5=very significant) |

| Tree | Planting around the pedestrian and bicycle lanes (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Architecture | Architectural design that looks beautiful, such as having a landmark, etc. (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| MotorProtection | Protection to prevent motorcycles from running on the sidewalk (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| CCTV | CCTV for security in risk areas (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| CheckPoint | Checkpoints for security guards (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| EmerPhone | A device for contacting the staff in case of an emergency (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| SafeCrossing | Clear crossing, clear intersection and technology is used to increase security (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Roof | Pedestrian covered walkways (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Light | Sufficient lighting at the pedestrian and bicycle lanes at night (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| TrashCan | Sufficient and suitable bins (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Sign | Road signs and maps for pedestrian and bicycle lane (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| WorkoutEquipment | Outdoor workout equipment (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| RestArea | Rest areas (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| BicycleParking | Sufficient bicycle parking (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| BicycleRental | A service point for borrowing and returning bicycles within the institution’s area (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| ShowerSpot | Shower spot and lockers (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| WaterStation | Drinking water service points (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| ConnectPubTran | The connection point between other public transport and pedestrian or bicycle lanes (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| NetworkConnection | Pedestrian and bicycle lanes are interconnected to cover the area (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Promote | Promotion through offline and online media (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Cleaning | Cleaning and Maintenance of sidewalks and bicycle paths (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| ServiceCentre | Notification of violation of the use of pedestrian and bicycle lane (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| OtherActivities | Using the area around the pedestrian and bicycle lanes to organize activities (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Application | Application to provide information and news about walking and cycling (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Charity | Policy to promote walking or bicycle by giving prizes or charitable donations (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| PhotoCompet | Pedestrian and bicycle photography or video contests (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| WalkBday | Walk or Bicycle Day activities (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| EduWB | Educating and organizing training on safety use of pedestrian and bicycle lanes (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| PublicTran | EncouragING to travel by public transport (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| Cooperate | Participation of students or staff in presenting the design of the pedestrian or bicycle lanes within the institute (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| OrgPolicy | Determining policies on improving and building pedestrian on campus (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly agree) |

| -2 Log Likelihood | Cox & Snell R² | Nagelkerke R² |

| 216.385 | 0.299 | 0.505 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | OR(Exp(B)) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen | -0.669 | 0.402 | 2.764 | 0.096* | 0.512 | |

| Age | -0.014 | 0.028 | 0.268 | 0.605 | 0.986 | |

| Edu (1) | 0.127 | 1.936 | 0.004 | 0.948 | 1.136 | |

| Edu (2) | -0.486 | 1.938 | 0.063 | 0.802 | 0.615 | |

| Edu (3) | 0.765 | 1.858 | 0.169 | 0.681 | 2.148 | |

| Edu (4) | 1.786 | 2.022 | 0.780 | 0.377 | 5.966 | |

| Income (1) | 0.400 | 0.487 | 0.675 | 0.411 | 1.492 | |

| Income (2) | -1.215 | 0.672 | 3.270 | 0.071* | 0.297 | |

| Income (3) | -2.174 | 0.752 | 8.363 | 0.004*** | 0.114 | |

| Income (4) | -1.426 | 0.937 | 2.316 | 0.128 | 0.240 | |

| Bicycle | 0.666 | 0.450 | 2.188 | 0.139 | 1.947 | |

| Distance | 0.023 | 0.030 | 0.582 | 0.445 | 1.023 | |

| TraCost | 0.008 | 0.004 | 4.044 | 0.044** | 1.008 | |

| TraMode (1) | 0.310 | 1.430 | 0.047 | 0.829 | 1.363 | |

| TraMode (2) | -1.768 | 0.561 | 9.917 | 0.002*** | 0.171 | |

| TraMode (3) | -1.995 | 0.699 | 8.138 | 0.004*** | 0.136 | |

| ActDistance (1) | 0.203 | 0.474 | 0.183 | 0.669 | 1.224 | |

| ActDistance (2) | -0.425 | 0.607 | 0.491 | 0.484 | 0.654 | |

| ActDistance (3) | -0.539 | 0.649 | 0.688 | 0.407 | 0.584 | |

| Separate | 0.150 | 0.273 | 0.302 | 0.583 | 1.162 | |

| Tree | -0.456 | 0.279 | 2.677 | 0.102 | 0.634 | |

| Architecture | 0.528 | 0.263 | 4.013 | 0.045** | 1.695 | |

| MotorProtection | 0.475 | 0.277 | 2.952 | 0.086* | 1.608 | |

| CCTV | 0.546 | 0.290 | 3.545 | 0.060* | 1.726 | |

| CheckPoint | -0.297 | 0.260 | 1.305 | 0.253 | 0.743 | |

| EmerPhone | -0.249 | 0.258 | 0.932 | 0.334 | 0.779 | |

| SafeCrossing | 0.501 | 0.261 | 3.667 | 0.056* | 1.650 | |

| Roof | -0.410 | 0.295 | 1.933 | 0.164 | 0.663 | |

| TrashCan | -0.340 | 0.281 | 1.460 | 0.227 | 0.712 | |

| Sign | 0.111 | 0.251 | 0.193 | 0.660 | 1.117 | |

| WorkoutEquipment | -0.103 | 0.259 | 0.157 | 0.692 | 0.902 | |

| RestArea | 0.599 | 0.282 | 4.500 | 0.034** | 1.820 | |

| BicycleParking | -0.057 | 0.252 | 0.052 | 0.820 | 0.944 | |

| BicycleRental | 0.256 | 0.284 | 0.813 | 0.367 | 1.291 | |

| ShowerSpot | -0.372 | 0.286 | 1.697 | 0.193 | 0.689 | |

| WaterStation | -0.419 | 0.306 | 1.878 | 0.171 | 0.658 | |

| ConnectPubTran | -0.061 | 0.321 | 0.037 | 0.848 | 0.940 | |

| Promote | -0.552 | 0.267 | 4.271 | 0.039** | 0.576 | |

| Cleaning | 0.253 | 0.275 | 0.846 | 0.358 | 1.288 | |

| ServiceCentre | 0.558 | 0.292 | 3.660 | 0.056* | 1.747 | |

| OtherActivities | 0.269 | 0.245 | 1.197 | 0.274 | 1.308 | |

| Application | -0.540 | 0.260 | 4.303 | 0.038** | 0.583 | |

| Charity | 0.132 | 0.244 | 0.292 | 0.589 | 1.141 | |

| PhotoCompet | 0.315 | 0.251 | 1.570 | 0.210 | 1.370 | |

| WalkBday | -0.325 | 0.246 | 1.734 | 0.188 | 0.723 | |

| EduWB | 0.306 | 0.245 | 1.556 | 0.212 | 1.358 | |

| PublicTran | 0.785 | 0.279 | 7.923 | 0.005*** | 2.192 | |

| Cooperate | -0.317 | 0.264 | 1.449 | 0.229 | 0.728 | |

| OrgPolicy | -0.034 | 0.280 | 0.015 | 0.904 | 0.967 | |

| Constant | -2.165 | 2.414 | 0.805 | 0.370 | 0.115 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).