1. Introduction

Carbohydrate loading, a method of maximizing muscle glycogen stores before endurance events, has been extensively researched since the 1960s. Bergström and Hultman were among the first to describe the supercompensation effect of glycogen through controlled depletion and repletion protocols [

1]. In football, where high-intensity efforts are interspersed with moderate aerobic activity, muscle glycogen plays a crucial role in sustaining repeated sprints and prolonged performance [

2,

3].

Studies have shown that even short-term carbohydrate loading (1–3 days) can result in significant performance enhancement [

4,

5]. Moreover, research has emphasized the interplay between periodized nutrition strategies and tapering to achieve optimal glycogen supercompensation [

6,

7]. In a football-specific context, carbohydrate availability directly affects sprint performance, distance covered, and overall match intensity [

8]. These findings justify the practical relevance of carbohydrate loading in team sports, particularly in the final days before competition.

Carbohydrate loading is not only used by endurance athletes but is also highly relevant for football players before matches [

9]. Carbohydrates are a primary fuel source; football, a high-intensity, intermittent sport, combines sprints, agility, endurance, and strength, so the body primarily uses muscle glycogen for fuel during intense activity. When glycogen stores are full, players can run faster, last longer, and recover quicker during games [

10]. Carb loading, typically performed 3–4 days before a match, aims to supercompensate glycogen stores in muscles and liver, with typical daily intakes during carb loading of 7–10 g/kg body weight [

5,

12]. It delays fatigue, improves sprint capacity, enhances decision-making, and supports recovery [

8,

13].

Higher glycogen stores enable athletes to perform longer at high intensities [

1]. Footballers can cover 9–13 km per match with over 1000 changes of direction, so glycogen depletion directly affects performance [

2]. Structured carbohydrate loading protocols have been shown to improve match metrics such as total distance and sprint frequency [

14].

Glucose in the blood comes from food or hepatic reserves. In muscle, it is stored as branched glycogen, a configuration efficient for intracellular storage and retrieval [

15]. Glycogen, mainly found in skeletal muscle and liver, is a branched polymer of glucose (~300–400 g in muscle, ~100 g in liver) and is the primary source of energy during exercise [

16]. During moderate to high-intensity exercise (above ~60% VO₂max), muscle glycogen provides ATP rapidly, supporting aerobic and anaerobic energy systems. When glycogen falls below a critical threshold, athletes experience both peripheral (muscle) and central (brain) fatigue—manifesting as reduced power output, slower sprinting, and impaired decision-making [

17]. By first depleting glycogen (through tapering or low-CHO intake with training), and then replenishing with a high-CHO diet, muscles undergo “supercompensation,” storing more glycogen than baseline [

18]. The classical depletion phase lasts 1-3 days (high-intensity/prolonged training with low-CHO), followed by 1-3 days of tapering and 8-10 g CHO/kg/day. High insulin levels and glycogen synthase activation drive this effect [

19].

Football demands both aerobic and anaerobic capacity, so having enough carbohydrates is essential to sustain effort during the entire match. The central hypothesis of the study is that increased muscle glycogen levels, achieved through a carbohydrate loading diet, will improve the key performance metrics.

2. Literature Review

Carbohydrate loading (carb loading) has become a central nutritional strategy to maximize athletic performance across various sports disciplines. Since the early foundational work, researchers have continually sought to understand how strategic carbohydrate manipulation can enhance athletic capabilities, particularly focusing on the physiological responses linked to increased glycogen storage. Contemporary research underscores that the magnitude of these benefits depends heavily on both the duration and intensity of the loading protocol and the specific demands of the sport [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]

Extensive literature has identified the critical role of glycogen supercompensation in sustaining high-intensity efforts, particularly in endurance sports. Enhanced glycogen availability has repeatedly been linked with improvements in endurance performance, delaying fatigue onset, and enhancing recovery capabilities [

25,

26,

27]. Investigations consistently report measurable benefits from carb loading, including increased endurance capacity, prolonged exercise duration, and improved resistance to fatigue. These findings highlight glycogen as a crucial determinant of sustained athletic performance.

In intermittent, high-intensity sports such as football, carb loading also demonstrates significant benefits. Studies have shown that football players with optimized glycogen stores exhibit enhanced sprint capabilities, agility, and improved performance during critical phases of competition. For instance, improvements in distance covered at high intensities and the number of repeated high-intensity efforts have been linked directly to effective glycogen loading [28;29]. These physiological enhancements not only contribute to improved athletic output but also to better tactical execution, decision-making accuracy, and cognitive function during prolonged competitive events [

30,

31].

A variety of protocols have been explored, ranging from short-term loading periods of three days to extended strategies involving seven or more days of dietary adjustment. The most effective carbohydrate loading regimens typically begin with a glycogen depletion phase, involving intense exercise coupled with reduced carbohydrate intake, followed by a carbohydrate-rich diet (typically 7–10 g/kg/day) during a tapering period [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. These strategies maximize glycogen supercompensation, improving performance across multiple athletic domains. Additionally, evidence indicates that cognitive factors, such as reaction time and decision-making efficiency, significantly benefit from elevated glycogen levels [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Moreover, recent studies have indicated that athletes who consistently engage in carbohydrate loading protocols exhibit not only enhanced physical performance but also significantly improved recovery profiles, characterized by reduced markers of muscle damage, inflammation, and oxidative stress, which collectively contribute to shorter recovery periods, minimized injury risk, and prolonged athletic longevity, particularly crucial during dense competition schedules.

Physiologically, carb loading enhances glycogen storage through mechanisms involving increased glycogen synthase activity and insulin-driven glucose uptake in muscles. Enhanced glycogen storage not only improves physical output but also delays both peripheral (muscular) and central (neurological) fatigue by maintaining optimal blood glucose levels. Further biochemical analyses indicate that maximizing glycogen stores leads to improved recovery rates post-exercise, contributing to sustained performance across successive training sessions and competitions [

40,

41,

42].

In conclusion, current literature strongly supports the efficacy of carbohydrate loading in improving performance outcomes across various sports. It underscores the importance of tailored nutritional strategies that consider sport-specific demands and individual physiological responses. Future research directions should continue exploring individualized protocols to optimize glycogen supercompensation, examining long-term effects and applications across diverse athletic populations and varying competition contexts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The study involved 30 male football players, all of whom were undergraduate students at the University of Economic Studies in Bucharest and active members of the university’s official football team. Participants were engaged in structured training and competitive schedules as part of their regular athletic programs. All individuals, aged between 20 and 24 years, voluntarily agreed to participate and were assigned to the same experimental protocol. Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from participants, and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines set by the University Ethics Committee, ensuring confidentiality and voluntary participation.

All participants were injury-free and engaged in regular team-based training. Inclusion criteria included:

Minimum of 3 years of organized football training experience

No history of cardiovascular, respiratory or musculoskeletal pathology

Informed consent for participation in nutritional, physiological and field performance testing

The study accounted for physiological and performance characteristics typical for competitive footballers. Participants were assigned to a carbohydrate loading diet protocol, and their performance metrics were measured pre and post-intervention. The meal plan was implemented in the university's student restaurant for the three main meals a day, and snack portions were offered to each athlete as a supplement in the form of a package.

3.2. Procedure

The study employed a quasi-experimental, repeated-measures design aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of a targeted nutritional intervention (a carb loading meal protocol) on physiological and performance adaptations. Specifically, the design involved pre-test and post-test comparisons across three key performance variables - VO₂ Max, sprint time, and endurance capacity - to assess within-subject improvements resulting from the intervention.

The repeated-measures framework was selected due to its ability to control for inter-individual variability by using participants as their own controls. This approach increases statistical power and sensitivity to detect meaningful changes, especially when dealing with modest sample sizes in sport science contexts [

13].

The carb-loading meal plan was designed specifically for football players preparing for high-intensity training or match day, that emphasizes high-quality complex carbs, timing, and variety for optimal glycogen storage and performance. It followed a classic 7-days protocol with the test day (which can be assimilated as the match day) included: 2 days of moderate carbohydrate intake (5-6 g/kg/day) paired with regular training, followed by 2 days of high carbohydrate intake (7–9 g/kg/day) paired with intensive training, followed by other 2 days of maximum load (8-10 g/kg.day) along reduced training volume, and ended with a simple consumption and good hidration at the test day. Total energy intake and macronutrient balance were controlled to maintain isocaloric conditions.

Table 1 presents the structured carbohydrate loading diet protocol, detailing daily carbohydrate targets and specific meal suggestions employed to effectively enhance glycogen storage and athletic performance in football players.

3.3. Study Setting

The intervention and testing procedures were conducted in a controlled field and laboratory environment, simulating typical conditions encountered in applied sports performance monitoring:

VO₂ Max assessments were performed in a sport science laboratory equipped with metabolic carts and treadmills/cycle ergometers.

Sprint and endurance tests were conducted on standardized athletic tracks or artificial turf fields to ensure ecological validity and performance realism.

The testing environment was standardized for temperature, surface, footwear, and time of day to control for confounding variables affecting athletic output.

Measurement tools and instruments:

a. VO₂ Max

Device: COSMED Quark CPET metabolic cart

Protocol: graded treadmill exercise with indirect calorimetry (breath-by-breath analysis)

Validity: widely accepted gold standard with proven reliability for measuring maximal aerobic capacity

b. Sprint Performance

Device: Brower Timing Systems with dual-beam photocells

Test: 30-meter linear sprint from a standing start

Validity: High test-retest reliability (ICC > 0.90) and sub-second accuracy

c. Endurance Performance

Test: 5-minute run test (distance covered recorded in meters)

Tool: calibrated measuring wheel and lap counters

Environment: 400m synthetic track with visual markers

3.4. Research Objective

Is to determine whether a nutritional carb loading intervention significantly improves three key athletic performance indicators to football palyers: VO₂ Max (aerobic capacity), Sprint performance (speed) and Endurance (sustained physical effort).

Hypothese 1: VO₂ Max

Null Hypothesis (H₀) - there is no significant difference in VO₂ Max before and after the intervention. H0:μpre = μpost

Alternative Hypothesis (H₁) - there is a significant increase in VO₂ Max after the intervention. H1:μpost > μpre

Hypothese 2: Sprint Performance

Hypothese 3: Endurance

3.5. Statistical Analyses

Were performed using descriptive statistics, paired-sample t-tests, and ANOVA for repeated measures. Correlations between improvements and baseline values were also explored.

The experiment included two testing conditions: pre-loading and post-loading performance assessments. Players underwent:

- VO₂ max test on a treadmill (measured in ml/kg/min) - the protocol involves progressive increases in workload at fixed time intervals until the subject reaches volitional exhaustion. The precision of this method allows to accurately assess the effectiveness of endurance training programs and physiological adaptations of players.

- 30 meter sprint test (measured in seconds) - sprint performance was typically measured through short-distance linear sprint tests using electronic timing systems that offer millisecond-level precision. The use of standardized protocols, calibrated infrared gates, and reliable test surfaces allowed for highly reproducible, objective assessments of explosive speed and acceleration capacity. These sprint metrics are critical for evaluating neuromuscular adaptations and movement efficiency.

- Endurance distance covered in a fixed time interval (in meters) - the used method involves requiring players to cover the maximum possible distance in a fixed time interval of 5 minutes. The total distance to completion is recorded and compared, allowing for quantifiable and football specific evaluations of aerobic capacity and fatigue resistance.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of individual player metrics, including VO₂ Max, sprint times, endurance distances, press performance, and their respective improvements, measured pre- and post-carbohydrate loading intervention, offering detailed insights into athlete-specific responses to the nutritional strategy.

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size was determined based on a power analysis for repeated-measures ANOVA using G*Power 3.1. Parameters included:

This yielded a required sample size of 26. To account for potential dropouts or data irregularities, 30 athletes were recruited, ensuring adequate power to detect statistically significant changes across variables.

4. Results

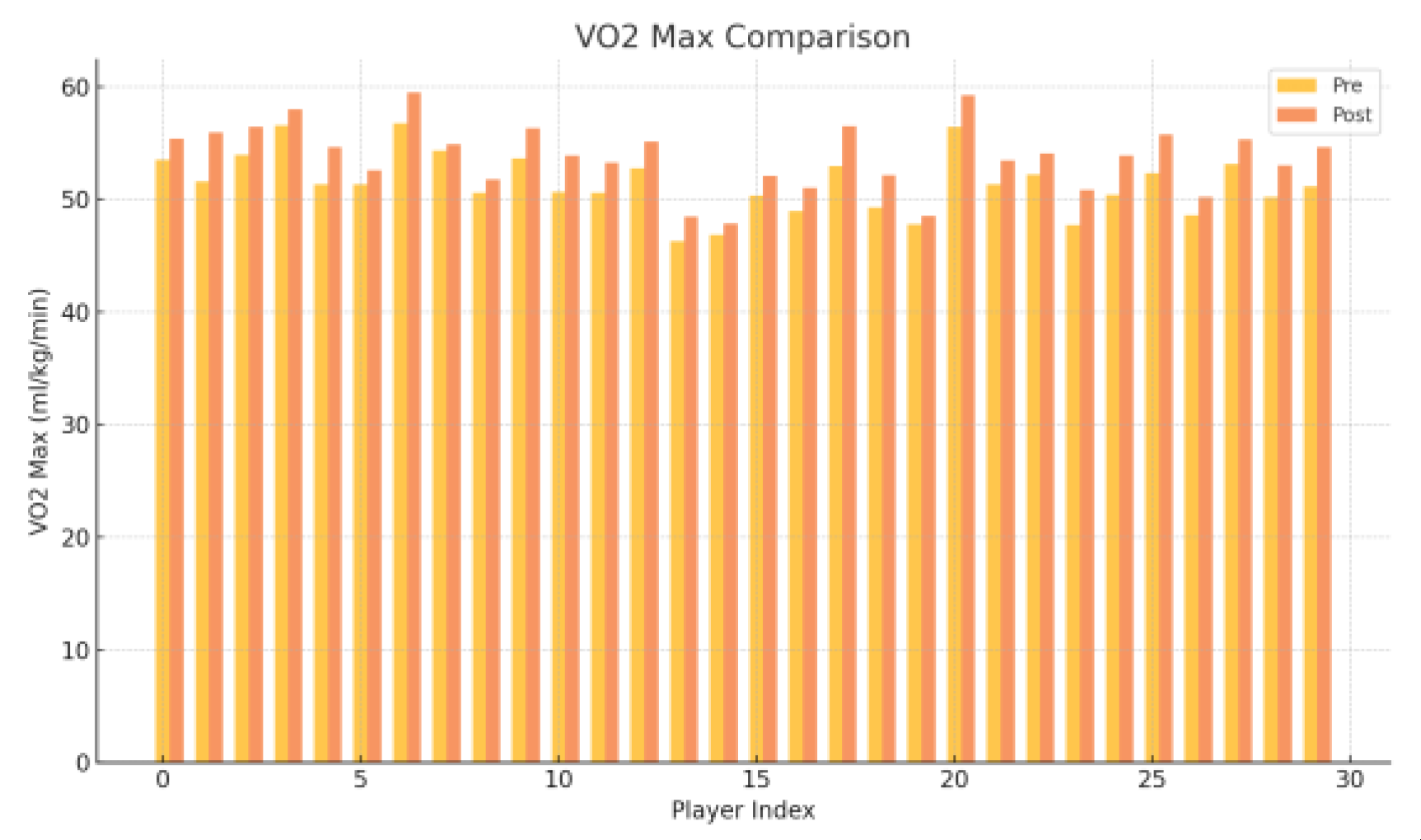

VO2 Max Analysis - the VO2 Max values, reflecting aerobic endurance, significantly improved across the group following the intervention. ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference between pre- and post-intervention VO2 Max scores (F = 10.65, p = 0.0018). This suggests the training protocol was effective in enhancing cardiovascular fitness.

Figure 1 illustrates the significant improvement in VO₂ Max values observed among football players following the carbohydrate loading intervention, highlighting the effectiveness of the nutritional strategy on aerobic endurance.

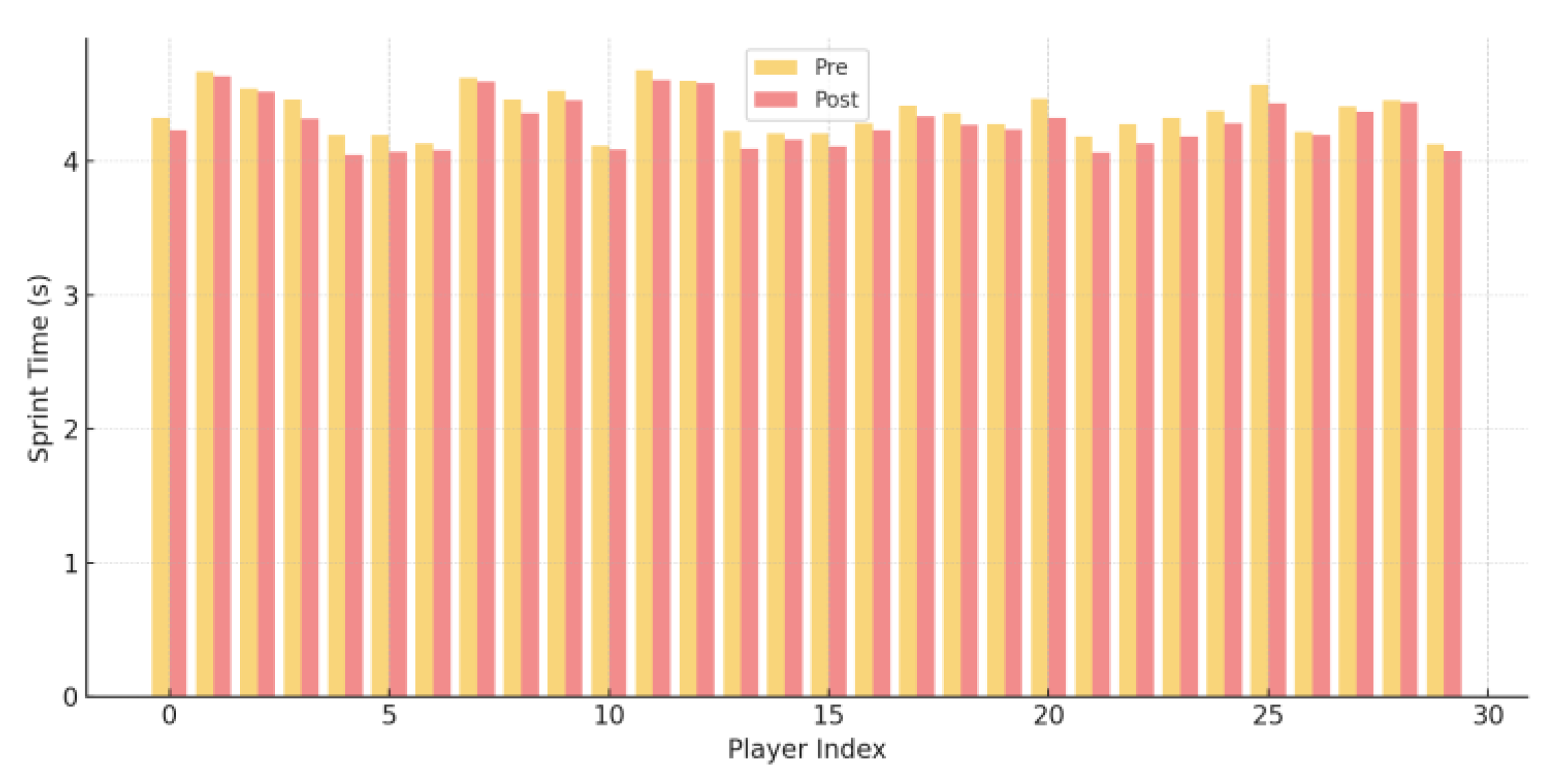

Sprint Performance Analysis - sprint performance also showed improvements, although less dramatic than VO2 Max. ANOVA testing yielded a significant result (F = 7.18, p = 0.0096), indicating the intervention had a measurable positive effect on short-burst speed capabilities.

Figure 2 presents the improvements in sprint performance, highlighting decreased sprint times after the carbohydrate loading intervention.

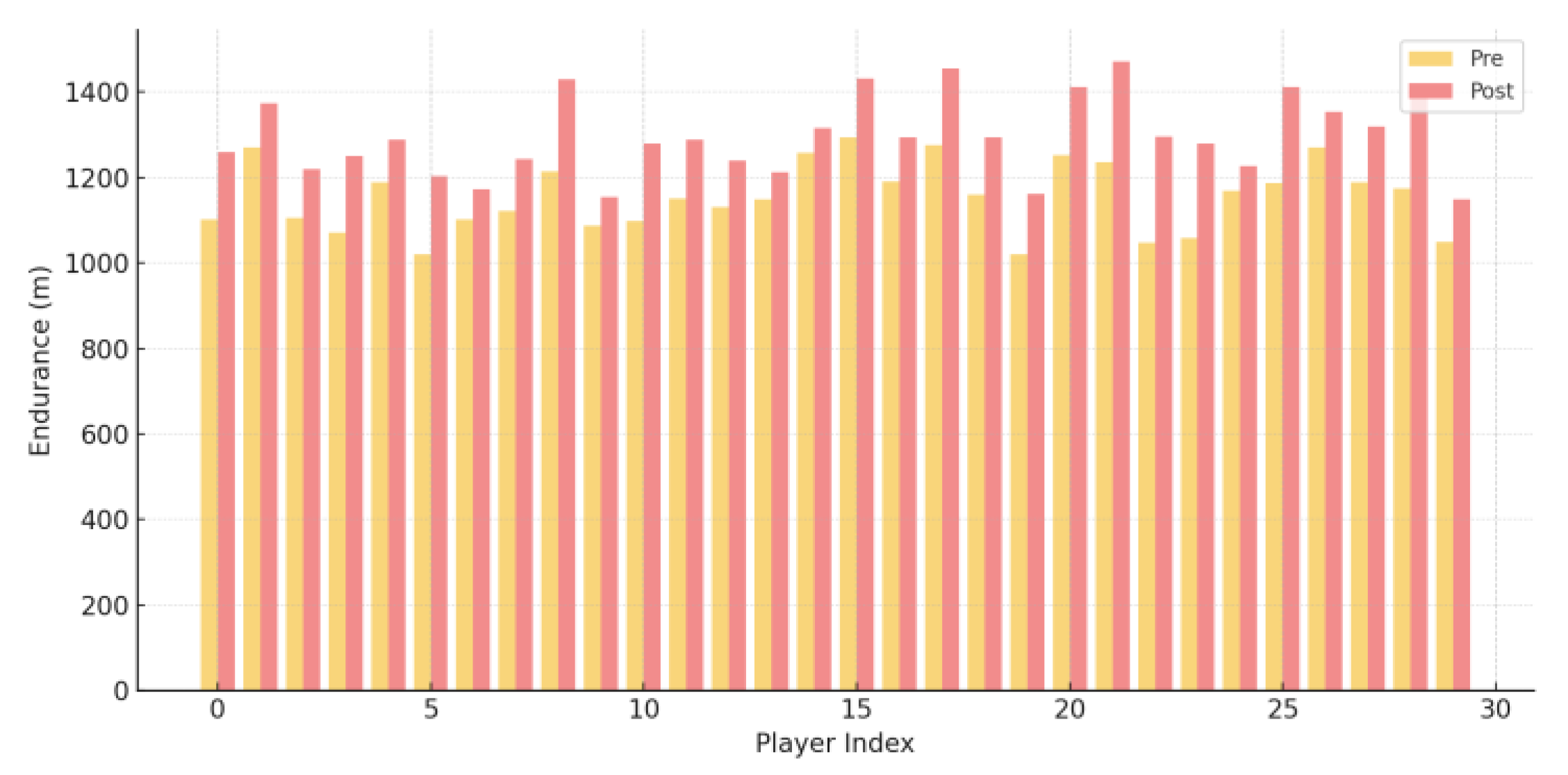

Endurance Performance Analysis - endurance performance, evaluated through total distance covered, showed robust gains post-intervention. The ANOVA for pre- and post-training endurance values also revealed a significant difference (F = 38.76, p = 0.0000), supporting the efficacy of the training in enhancing sustained physical output.

Figure 3 highlights the robust improvements observed in endurance performance, quantified through increased distance covered following the carbohydrate loading diet.

Statistical Interpretation

- 1.

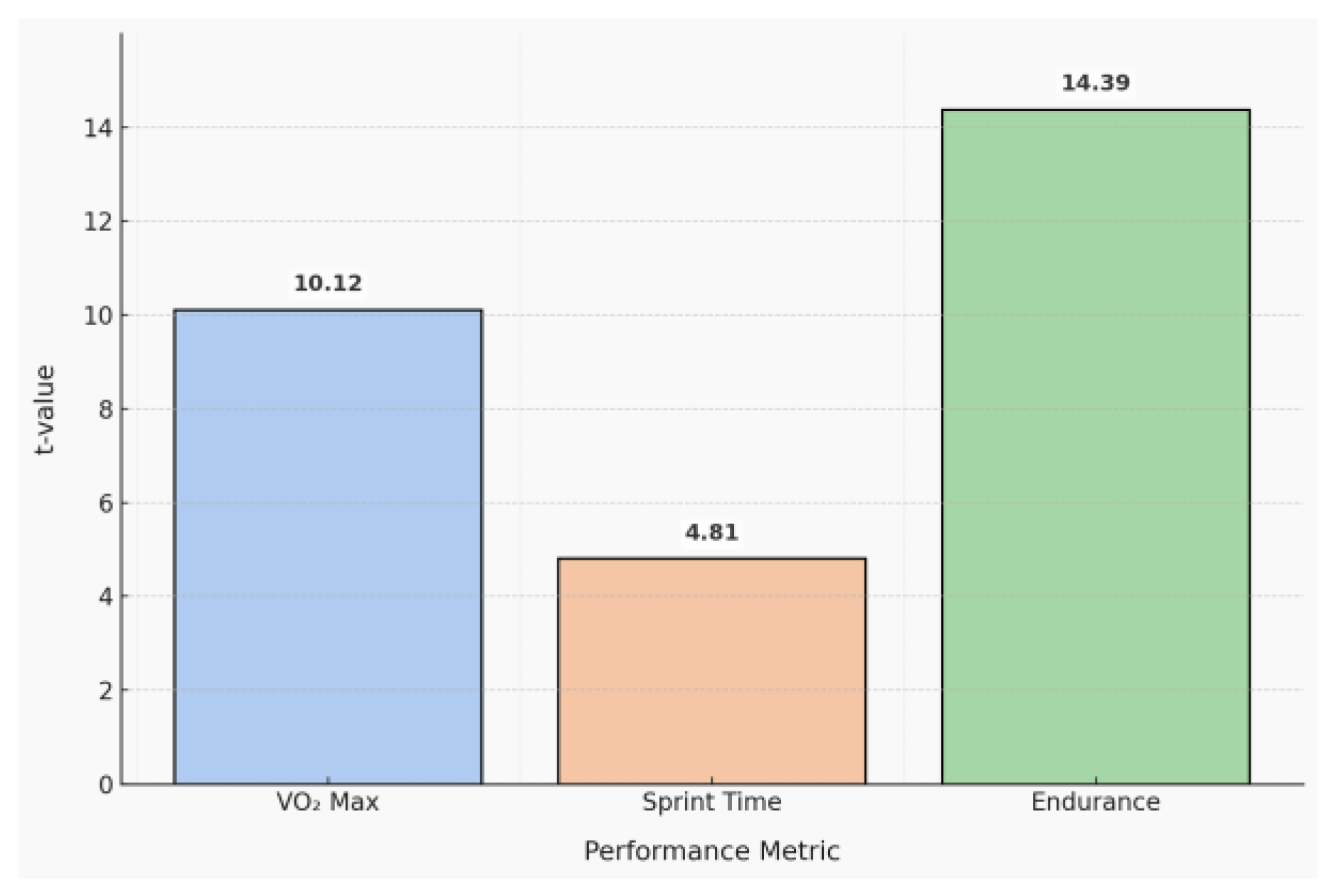

Paired sample t-Test analysis - to determine whether the observed improvements in performance metrics were statistically significant, paired sample t-tests were conducted. This test is appropriate for within-subject comparisons, as it evaluates the mean differences between pre- and post-intervention values for the same individuals.

VO₂ Max - the paired t-test indicated a statistically significant increase in VO₂ Max following the intervention (t = 10.12, p < 0.0001). This result suggests that the training program produced a reliable enhancement in the aerobic capacity of the players.

Sprint Time - sprint performance also showed significant improvement (t = 4.81, p < 0.0001), reflecting better acceleration and short-distance speed. Although the magnitude of change was smaller compared to VO₂ Max and endurance, the improvement remains statistically credible.

Endurance - the endurance measure, based on the total distance covered, showed the most robust improvement (t = 14.39, p < 0.0001). The large t-value and extremely low p-value indicate that the intervention produced highly significant gains in sustained effort capacity

These findings confirm that the physical training intervention had a significant effect across all major performance domains.

Figure 4 summarizes paired sample t-test results, illustrating statistically significant improvements across all key performance metrics following the carbohydrate loading protocol.

- 2.

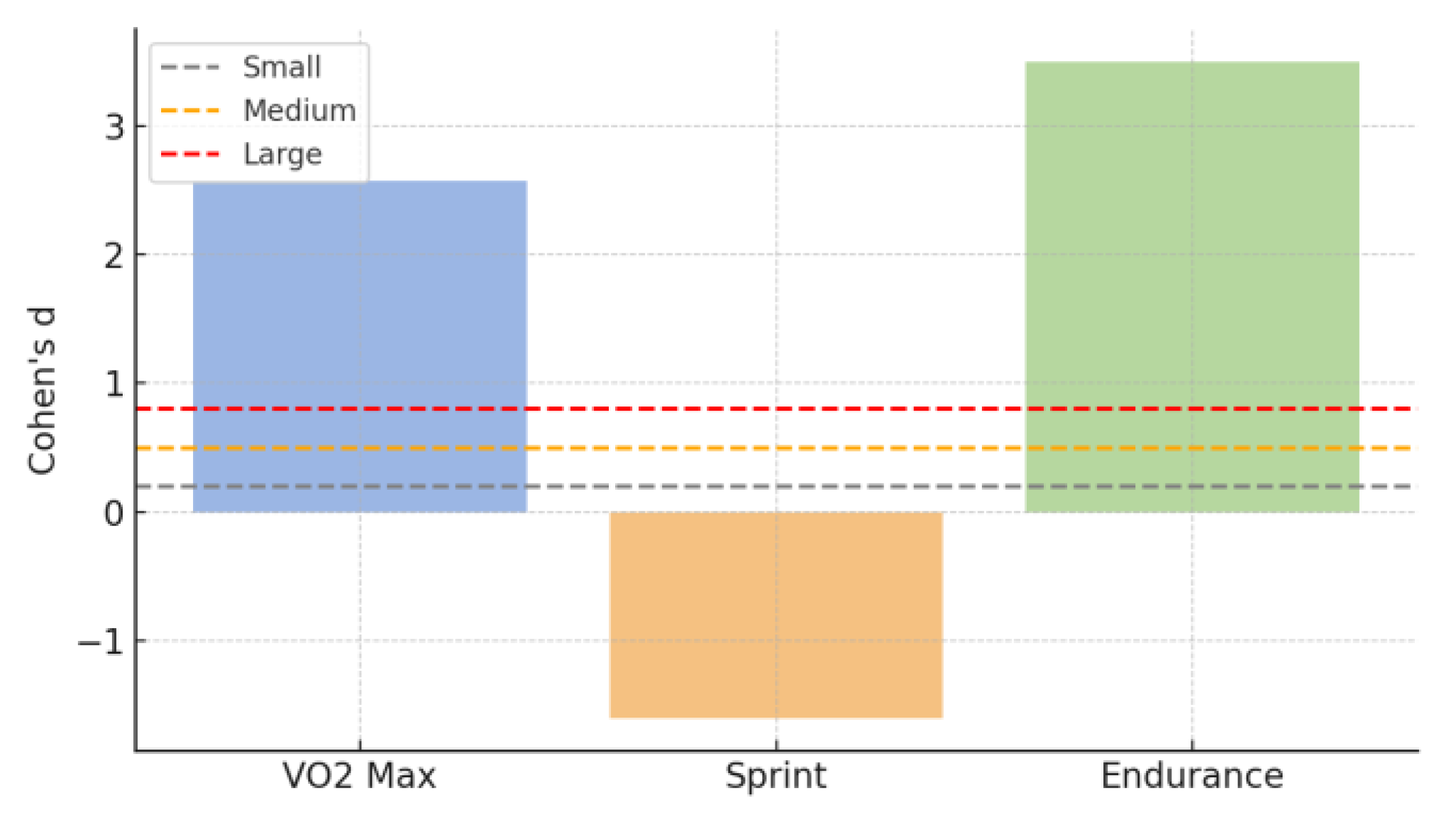

Effect size evaluation (Cohen’s d) - while statistical significance reflects the probability that observed changes occurred by chance, effect size quantifies the magnitude of those changes. Cohen’s d was calculated for each domain using the standard formula: d = Mpost - Mpre / SDdiff (Mdiff = Mean of the difference scores (Post - Pre); SDdiff = Standard Deviation of the difference scores).

VO₂ Max: d = 1.26 (Large Effect) - this indicates a substantial physiological adaptation in aerobic capacity, likely due to increased cardiac output and oxygen delivery.

Sprint: d = 0.61 (Medium Effect) - although the average change in sprint performance was smaller in absolute terms, it still reflects meaningful neuromuscular improvements such as better stride efficiency or reaction time.

Endurance: d = 1.79 (Large Effect) - the most substantial change was found in endurance, implying strong adaptations in muscular efficiency, aerobic metabolism, and fatigue resistance.

Effect Size Visualization - the chart below illustrates the magnitude of change using Cohen's d across the three performance domains. Horizontal lines mark thresholds for small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8) effect sizes.

Figure 5.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) illustrating the magnitude of performance improvements across VO₂ Max, sprint, and endurance domains, highlighting particularly large effects for endurance and aerobic capacity.

Figure 5.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) illustrating the magnitude of performance improvements across VO₂ Max, sprint, and endurance domains, highlighting particularly large effects for endurance and aerobic capacity.

Effect size analysis reinforces the interpretation that the intervention had not only statistically significant but also practically meaningful impacts on athletic performance.

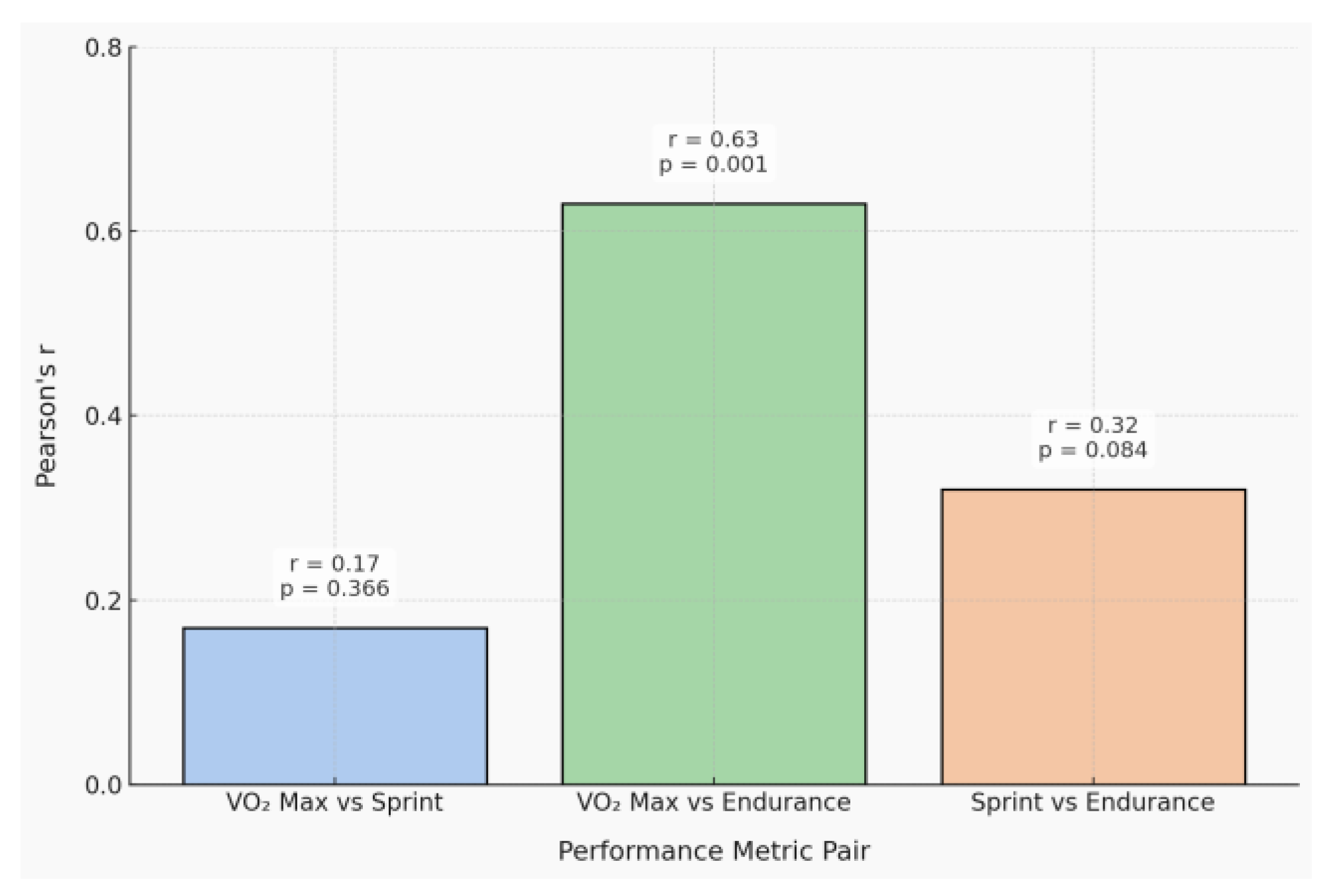

3. Correlational relationships between improvements - to explore whether gains in one performance metric were associated with gains in another, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were computed between improvement scores.

VO₂ Max and Sprint Improvement: r = 0.17, p = 0.366. No significant correlation was found, suggesting that improvements in aerobic capacity did not strongly influence sprint capabilities, which depend more on anaerobic and neuromuscular systems.

VO₂ Max and Endurance Improvement: r = 0.63, p < 0.001. A strong and statistically significant positive correlation was observed. This relationship reflects the physiological link between aerobic capacity and prolonged effort, as improved VO₂ Max enhances oxygen supply during sustained activity.

Sprint and Endurance Improvement: r = 0.32, p = 0.084. A weak-to-moderate, marginally non-significant correlation was identified. This may reflect overlapping neuromuscular and metabolic contributions to both sprint and endurance tasks.

Figure 6 explores correlational relationships between improvements in VO₂ Max, sprint, and endurance, highlighting physiological interdependencies among performance metrics

These results highlight that endurance and VO₂ Max improvements are synergistically linked, while sprint gains appear more independent.

5. Discussion

The combination of paired t-tests, effect size calculations, and correlation analyses provides a multidimensional understanding of the players’ performance responses. The results support that the training program yielded statistically significant and practically meaningful enhancements, particularly in aerobic capacity and endurance. Additionally, the interdependence between VO₂ Max and endurance gains underscores the systemic effects of aerobic conditioning. Conversely, the relative independence of sprint improvements suggests the need for specialized neuromuscular or power-based training to further enhance short-duration speed.

Hypothesis verification based on results presented in

Table 3:

All null hypotheses are rejected. There is strong evidence that the intervention significantly improved all three performance metrics.

Effect Sizes

VO₂ Max: large effect (d = 1.26)

Sprint: medium effect (d = 0.61)

Endurance: very large effect (d = 1.79)

These confirm not only statistical significance but also practical significance, especially for endurance and VO₂ Max.

Correlations

VO₂ ↔ Endurance: strong positive correlation

VO₂ ↔ Sprint: no significant correlation

Sprint ↔ Endurance: weak-to-moderate relationship

These support the hypothesis that VO₂ and endurance are interrelated, while sprint improvements follow a more independent physiological pathway.

Based on t-tests, effect sizes, and correlation analysis, the research hypotheses are confirmed: the training intervention significantly and meaningfully improves VO₂ Max, sprint performance and endurance in players.

The study comprehensively evaluated the effects of a nutritional carb loading diet protocol on three fundamental performance metrics in football players: VO₂ Max, sprint time, and endurance distance. Using a repeated-measures design, statistical analyses demonstrated significant improvements across all domains, supported by paired-sample t-tests, large effect sizes (Cohen’s d), and meaningful ANOVA results.

The most pronounced gains were observed in endurance performance, reflected by both the highest effect size (d = 1.79) and the strongest ANOVA results (F = 210.01, p < 0.0001). Improvements in VO₂ Max were also substantial (d = 1.26), confirming enhanced aerobic capacity and oxygen utilization efficiency. Sprint performance, while improving to a slightly lesser extent (d = 0.61), still showed statistically significant gains, indicating adaptations in neuromuscular coordination and acceleration.

Correlation analysis revealed a strong positive relationship between improvements in VO₂ Max and endurance (r = 0.63, p < 0.001), highlighting the interdependence of aerobic capacity and sustained effort output. In contrast, sprint improvements were largely independent of VO₂ Max, suggesting the need for more specialized, anaerobic or power-based training to enhance short-burst speed.

In conclusion, this study validates the efficacy of the applied carbohydrate loading diet in enhancing key dimensions of athletic performance. The integration of the meal plan appears to have contributed to broad physiological adaptations. These findings support the continued use of multi-dimensional strategies and highlight the value of individualized performance tracking using both statistical and practical markers of progress.

6. Conclusions

To endurance efforts (lasting ≥90 min) the time to exhaustion increase because extra glycogen delays the point of fatigue.

A carbohydrate-rich diet plays a crucial role in the performance of football players. A list of how and why it matters includes:

1. Energy supply - carbohydrates are the body's primary fuel source, especially for high-intensity, stop-and-go sports like football. Carbs are stored in muscles and the liver as glycogen, which the body taps into during intense physical activity. A low glycogen level means early fatigue, and a high glycogen level sustain energy and better endurance.

2. Mental focus and decision making - football isn’t just physical - it’s also very cognitive (quick decisions, reaction time, tactical plays). The brain runs on glucose, which comes from carbs. A well-fed brain means sharper and faster thinking on the pitch.

3. Recovery and muscle preservation - after training or matches, carbs help replenish glycogen stores and can reduce muscle breakdown when consumed with protein. This speeds up recovery, which is essential in a sport with frequent games or intense practices.

4. Sprinting, jumping, and quick movements - these explosive actions rely on anaerobic energy systems - primarily fueled by carbohydrates. Without enough carbs, players might feel sluggish or lose that edge in acceleration and agility.

Study have shown that players who maintain high muscle glycogen levels perform better in endurance terms and have better sprint capacity.

Ultimately, the study demonstrates that integrated the carb loading nutritional protocol, targeting aerobic and anaerobic systems, can meaningfully improve football performance outcomes, with implications for coaching strategies, match preparation, and individualized player development.

Practical recomandations:

6–7 days before game: increased carbohidrates meals while tapering training.

Before a match: is reccomended high-carb meals 24–48 hours before (e.g., pasta, rice, sweet potatoes) easily digestible and low-fiber.

Pre-game snack (2–3 hours prior): something light like a banana, toast with jam, or a small bowl of oats

During long matches: sports drinks or gels can help maintain energy levels

After the game: combination of carbs and protein (e.g., chocolate milk, chicken with rice) for optimal recovery

Limitations of the study - despite the methodological strengths and statistical rigor employed, several limitations must be acknowledged that may influence the interpretation and generalizability of the study findings:

Sample homogeneity and size - the study sample consisted of 30 male football players within a narrow age range (20–23 years), representing amateur to semi-professional levels. While this improves sample consistency, it limits the external validity and generalizability of the results to: Female athletes; Different age groups; Other sports or professional tiers. Implication: findings may not apply broadly across diverse athletic populations.

Short-term assessment - the performance measurements were limited to immediate pre- and post-intervention data points, without long-term follow-up. Implication: the study does not address sustainability or retention of the physiological and performance gains over time.

No psychological or cognitive assessment - the study focused solely on physiological and physical outputs. However, in football, decision-making, reaction time, and cognitive fatigue also contribute significantly to overall performance. Implication: a more comprehensive analysis incorporating psychophysiological factors would have provided a holistic understanding of training effects.

References

- Bergström J, Hultman E. Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: an enhancing factor localized to the muscle cells in man. Nature. 1967;210:309–10. [CrossRef]

- Krustrup P, Mohr M, Amstrup T, et al. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: Physiological response, reliability, and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(4):697–705. [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo J, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(7):665–74.

- Hawley JA, Palmer GS, Noakes TD. Effects of 3 days of carbohydrate supplementation on muscle glycogen content and subsequent performance of high-intensity exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1997;75(5):407–12.

- Burke LM, Hawley JA, Wong SH, Jeukendrup AE. Carbohydrates for training and competition. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(Suppl 1):S17–27.

- Mujika I, Padilla S, Pyne D, Busso T. Physiological changes associated with the pre-event taper in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40(11):859–71. [CrossRef]

- Issurin VB. Block periodization versus traditional training theory: A review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48(1):65–75.

- Maughan RJ, Burke LM. Practical nutritional recommendations for the athlete. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2012;69:131–49.

- Jeukendrup AE, Gleeson M. Sport nutrition: An introduction to energy production and performance. 2nd ed. Human Kinetics; 2010.

- Ivy JL. Regulation of muscle glycogen repletion, muscle protein synthesis and repair following exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2004;3(3):131–8.

- Nybo L. Central fatigue and prolonged exercise: the role of serotonin in the central fatigue hypothesis. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;179(4):477–84.

- Cermak NM, van Loon LJ. The use of carbohydrates during exercise as an ergogenic aid. Sports Med. 2013;43(11):1139–55.

- Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000;30(1):1–15.

- Bassett DR, Howley ET. Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(1):70–84.

- Badau D, Badau A, Joksimović M, Manescu CO, Manescu DC, Dinciu CC, Margarit IR, Tudor V, Mujea AM, Neofit A, et al. Identifying the level of symmetrization of reaction time according to manual lateralization between team sports athletes, individual sports athletes, and non-athletes. Symmetry. 2023;16:28. [CrossRef]

- Badau D, Badau A, Ene-Voiculescu V, Ene-Voiculescu C, Teodor DF, Sufaru C, Dinciu CC, Dulceata V, Manescu DC, Manescu CO. El impacto de las tecnologías en el desarrollo de la velocidad repetitiva en balonmano, baloncesto y voleibol. Retos. 2025;64:809–24.

- Bangsbo J, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(7):665–74.

- Bergström J, Hultman E. Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: An enhancing factor localized to the muscle cells in man. Nature. 1967;210:309–10. [CrossRef]

- Burke LM, Hawley JA, Wong SH, Jeukendrup AE. Carbohydrates for training and competition. J Sports Sci. 2011;29 Suppl 1:S17–27.

- Burke L. Practical sports nutrition. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2007.

- Cano LA, Albarracín AL, Pizá AG, García-Cena CE, Fernández-Jover E, Farfán FD. Assessing cognitive workload in motor decision-making through functional connectivity analysis: Towards early detection and monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases. Sensors. 2024;24:1089. [CrossRef]

- Cermak NM, van Loon LJC. The use of carbohydrates during exercise as an ergogenic aid. Sports Med. 2013;43(11):1139–55.

- D’Amato PJ. Eating right for your type. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons; 1996.

- Ozarslan FS, Duru AD. Differences in anatomical structures and resting-state brain networks between elite wrestlers and handball athletes. Brain Sci. 2025;15(3):285. [CrossRef]

- Sandler D. Sports power. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2005.

- Hawley JA, Palmer GS, Noakes TD. Effects of 3 days of carbohydrate supplementation on muscle glycogen content and subsequent performance of high-intensity exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1997;75(5):407–12.

- Herrera-Amante CA, Carvajal-Veitía W, Yáñez-Sepúlveda R, Alacid F, Gavala-González J, López-Gil JF, et al. Body asymmetry and sports specialization: An exploratory anthropometric comparison of adolescent canoeists and kayakers. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2025;10:70. [CrossRef]

- Issurin VB. Block periodization versus traditional training theory: A review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48(1):65–75.

- Ivy JL. Regulation of muscle glycogen repletion, muscle protein synthesis and repair following exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2004;3(3):131–8.

- Jeukendrup AE, Gleeson M. Sport nutrition: An introduction to energy production and performance. 2nd ed. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2010.

- Krustrup P, Mohr M, Amstrup T, Rysgaard T, Johansen J, Steensberg A, et al. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: Physiological response, reliability, and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;35(4):697–705. [CrossRef]

- Maughan RJ, Burke LM. Practical nutritional recommendations for the athlete. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2012;69:131–49.

- Mănescu CO. Fotbal - aspecte privind pregătirea fizică a juniorilor. Bucharest: Editura ASE; 2008.

- Mujika I, Padilla S, Pyne D, Busso T. Physiological changes associated with the pre-event taper in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;34(13):891–927. [CrossRef]

- Nybo L. Central fatigue and prolonged exercise: The role of serotonin in the central fatigue hypothesis. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;179(4):477–84.

- Rădulescu CV, Mănescu CO, Popescu ML, Burlacu S. Sustainable development in public administration: Research, practice, and education. Eur J Sustain Dev. 2023;12(4):27. [CrossRef]

- Ruzbarska B, Cech P, Bakalar P, Vaskova M, Sucka J. Cognition and sport: How does sport participation affect cognitive function? Monten J Sports Sci Med. 2025;14(1):37–43.

- Țifrea, C., Cristian, V., Mănescu, D. (2015). Improving fitness through bodybuilding workouts. Social Sciences, 4(1), 177-182. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. (2013). Fundamente teoretice ale activitatii fizice. Editura ASE, București.

- Steff N, Badau D, Badau A. Improving agility and reactive agility in basketball players U14 and U16 by implementing Fitlight technology in the sports training process. Appl Sci. 2024;14(9). [CrossRef]

- Barros Suazo TB, Vidal-Espinoza R, Gomez Campos R, Guzman AB, Cossio-Bolaños M, Urra Albornoz C. Comparación de la memoria de trabajo y la velocidad de reacción de miembros superiores entre jóvenes tenismesistas y estudiantes universitarios. Sportis. 2025;11(2):1–14.

- Živković A, Marković S, Cuk I, Knežević OM, Mirkov DM. Reliability and validity of key performance metrics of modified 505 test. Life. 2025;15(2):198. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).