1. Introduction

The ongoing advancement of the automotive industry necessitates the development of lightweight, high-performance materials for critical components, such as brake rotors. Traditionally, brake rotors are manufactured from gray cast iron (GCI) owing to its satisfactory wear resistance, excellent damping properties, friction behavior, volumetric heat capacity, and cost-effectiveness [

1,

2,

3]. However, the high density of cast iron significantly contributes to the overall vehicle weight, resulting in increased fuel consumption and emissions. Furthermore, the susceptibility of GCI rotors to corrosion presents an additional challenge that requires immediate attention, particularly for electric vehicle applications [

4,

5]. To address these issues, researchers and manufacturers have investigated advanced lightweight materials, with a particular focus on aluminum metal matrix composites (Al-MMCs) as potential alternatives to brake rotors [

3,

6,

7].

Al-MMCs present a distinctive combination of high strength, low density, and enhanced thermal conductivity, rendering them promising candidates for automotive braking applications [

3,

8]. The integration of ceramic reinforcements, such as silicon carbide (SiC), aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃), and graphite, enhances their mechanical and tribological properties, thereby improving the wear resistance and frictional performance under braking conditions [

9,

10]. Among the various processing techniques available for the fabrication of Al-MMCs, squeeze casting has emerged as the preferred method because of its capability to produce components with reduced porosity, improved interfacial bonding, and enhanced mechanical properties [

11,

12,

13]. Despite these advantages, the tribological performance of squeeze-cast Al-MMC brake rotors under realistic braking conditions has not been investigated sufficiently.

The braking system of a vehicle operates under complex and demanding conditions involving high contact pressures, fluctuating temperatures, and repeated sliding interactions. These factors significantly influence the frictional behavior, wear mechanisms, and thermal stability of brake rotors [

14]. The tribological performance of a brake rotor is primarily characterized by its coefficient of friction (CoF), wear resistance, and heat dissipation capability. A stable CoF is essential for consistent braking performance, whereas superior wear resistance ensures an extended component lifespan. In addition, the ability to dissipate heat effectively minimizes the risk of brake fading and thermal damage [

15].

Numerous studies have examined the tribological properties of Al-MMCs for braking applications. For example, Awe et al. [

16] compared the wear behavior of Al-SiC MMCs with that of coated and uncoated conventional cast iron rotors and found significantly lower wear rates in Al-MMCs. This reduction in wear is attributed to the ability of the reinforcing phase to resist abrasion. Similarly, Wu et al. [

17] and Ye et al. [

18] demonstrated that graphite-reinforced Al-MMCs possess self-lubricating properties, which enhance frictional stability and reduce material degradation. However, these investigations were primarily conducted using laboratory-scale pin-on-disc or ball-on-disc configurations, which do not fully replicate real-world braking conditions. To address this limitation, full-scale dynamometer testing is required to evaluate Al-MMC rotors under simulated braking scenarios.

Dynamometer testing is a widely recognized method for evaluating brake rotor performance under controlled yet realistic conditions. Among the various test protocols, the AK-Master test is an industry-standard procedure that replicates a range of braking conditions, including normal, aggressive, and emergency braking scenarios [

19,

20,

21]. This test provides critical insights into key tribological parameters, such as CoF variation, wear rates, and thermal response, offering a comprehensive evaluation of rotor performance.

The present study utilized an AK-Master dynamometer test to examine the tribological behavior of a squeeze-cast Al-MMC brake rotor. The AK Master (SAE J2522) [

19] is a performance test designed to simulate various braking scenarios on dynamometer stands, thereby subjecting brake systems to real driving conditions and stresses experienced during stops. Additionally, the AK Master test comprises different bedding and fading phases and integrates values of initial speed, initial temperature, and pressure (10-80 bar) of brake applications. This test is essential for characterizing brake materials and ensuring their safety and performance in automotive applications. This methodology enables a direct comparison of the tribological properties of Al-MMC with varying chemical compositions, thereby yielding valuable data on frictional stability, wear mechanisms, and thermal effects. By analyzing the worn surfaces using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), this study aims to identify the predominant wear mechanisms and material degradation patterns, further elucidating the suitability of Al-MMCs for braking applications.

Recent investigations by Lattanzi et al. [

22,

23] examined the effects of nickel (Ni) and zirconium (Zr) addition on the high-temperature mechanical and tribological properties of aluminum–silicon (Al–Si) matrix composites reinforced with 20 wt. % silicon carbide (SiC) particles. Their results revealed that the incorporation of Ni consistently enhanced the mechanical responses of the composites at elevated temperatures. In contrast, Zr addition did not yield comparable improvements. Notably, the synergistic interaction between the SiC particles, eutectic Si, and eutectic Ni-based intermetallic phases contributed to a 44% increase in the activation energy of the deformation process [

22]. The observed increase in composite hardness due to Ni and Zr addition was attributed to secondary phase precipitation and solid solution strengthening mechanisms. However, the wear rate of the composites, ranging from 2 to 8 × 10⁻⁵ mm³/N·m, did not exhibit a direct correlation with hardness, indicating the influence of more complex wear mechanisms in the system.

Building on this foundation, the present study sought to evaluate and compare the frictional performance of squeeze-cast Al-MMC brake rotors with varying chemical compositions using standardized AK-Master dynamometer testing protocols. The objectives include a detailed assessment of the wear mechanisms and degradation pathways through advanced microstructural and surface characterization techniques as well as thermal performance monitoring during braking cycles. In addition, this study aims to compare the tribological behavior of Al-MMC brake rotors with that of their conventional cast iron counterparts, thereby identifying potential advantages in terms of performance, weight reduction, and durability. The outcomes of this research offer valuable empirical insights into the real-world tribological behavior of squeeze-cast Al-MMCs, contributing to the development and optimization of next-generation lightweight braking systems. Furthermore, the results are expected to guide the refinement of alloy composition, casting process parameters, and surface engineering strategies to enhance the operational performance and service life of Al-MMC brake rotors in automotive applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Brake Rotor Materials and Fabrication

The Automotive Components Floby AB (Floby, Sweden) provided the investigated materials. The composites were produced by squeeze casting with a targeted SiC content of 20 wt.%. The details of the casting procedure are described elsewhere [

22]. SiC particles were purchased from Fiven ASA (Oslo, Norway) and were composed of cubic β-SiC and hexagonal/rhombic α-SiC structures, with an average particle size of 20 μm.

Table 1 lists the chemical compositions of the composites, which were measured using optical emission spectrometry. The Si content in

Table 1 provides the total silicon (Si) amount, the sum of the Si in the base alloy, and the Si in the SiCp for each MMC material.

The GCI material, commonly employed in brake-disc applications, was examined for comparative analysis with composite materials. The elemental composition of the GCI material, expressed in weight percentages, is as follows: carbon (C), 3.7%; silicon (Si), 2.0%; manganese (Mn), 0.7%; phosphorus (P), 0.05%; sulfur (S), 0.14%; chromium (Cr), 0.10%; and copper (Cu), 0.17%.

To facilitate the activation of the friction surfaces of the MMC brake rotors for expedited bedding-in during the dynamometer test, the MMC rotors underwent post-machining chemical etching, as detailed in [

24]. In contrast, the GCI rotor was employed without additional treatment following machining.

Figure 1 presents a representative photograph of the MMC and GCI rotors before the dynamometer AK-Master protocol.

The microstructures of the various materials were investigated using optical (Olympus DSX1000) and scanning electron microscopy (TESCAN Mira 4) after standard metallographic preparation, and the different phases were identified using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, EDAX Octane Elect). The microhardness of both the MMC and GCI materials was determined using a FALCON 600 Vickers hardness tester on the unetched metallographic samples. Microhardness measurements were performed according to the ISO 6507-1:2018 standard. A constant load of 1000 gf was applied for a dwelling time of 10 s, and ten readings were taken in the longitudinal direction of each sample. The average microhardness (HV1) of each specimen was calculated and reported along with its standard deviation.

2.2. Experimental Setup: AK-Master Dynamometer Testing

The braking test was executed utilizing a full-scaled dynamometer with an inertia of 46.85 kg m² at Federal-Mogul Bremsbelag GmbH, Germany. During each braking snub, the friction and temperature data were recorded at a frequency of 100 Hz. The surface temperature of the disc was measured using a rubbing thermocouple that maintained physical contact with the frictional surface of the disc throughout the test. A pair of non-asbestos organic (NAO) brake pads with a zero-copper formulation (FER9701) was employed as friction couples for the MMC and GCI brake rotors. Brake pads were manufactured and supplied by Federal-Mogul Bremsbelag GmbH (Glinde, Germany).

Figure 2 shows an image of the brake measurement section of the dynamometer. The braking effectiveness of various friction pairs was evaluated according to the AK master test protocol (SAE J2522) [

19]. The specific test conditions were defined in the SAE-J2522 standard and are listed in

Table 2. To elucidate the friction properties and wear mechanisms of rotor-pad braking pairs under varying conditions, repeated tests were conducted at different braking speeds and pressures. This paper analyzes and discusses

Sections 4, 9–12, 14, and 15 of the AK master protocol, as highlighted in

Table 2. It is noteworthy that the cooling air with a velocity of 8 km/h, as recommended by SAE-J2522, was directed at the braking pair during the tests, where cooling was desired. The test temperature ranges for the MMC and GCI brake rotors were 50–400 °C and 100–500 °C, respectively. The frictional performance of the rotors was assessed by monitoring the variation in the coefficient of friction (COF) across braking cycles using a computer log connected to the dynamometer. Wear analysis was performed using a mass measurement method, wherein the weights of the rotors and pads were recorded before and after the test, allowing for the calculation of weight loss or gain by the rotors and pads. The post-test surface morphology analysis of the rotors was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and optical microscopy.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure Analysis of the Rotors

The microstructures of the composites and GCI brake rotors were examined using optical microscopy, and the findings are presented in

Figure 3. Mat000 (

Figure 3a) served as the reference composite material, comprising an Al-Si9-Mg0.3 alloy reinforced with 20 wt.% SiC particles. The SiC particles were observed as dark polygonal features, consistently present across all three composite materials analyzed. The incorporation of 3.5 wt.% Ni into the matrix alloy results in the formation of Al

3Ni particles, which emerge at the boundaries of the primary aluminum dendrites within the Mat300 and Mat350 microstructures (

Figure 3b-c). The constituent phases within the composite materials were identified using EDS analysis and compared with literature reports, as detailed in our previous publications [

22,

23]. The results indicate that the primary microstructural feature distinguishing Mat300 and Mat350 from Mat000 is the presence of the Al

3Ni phase in addition to the microstructural characteristics of Mat000. The incorporation of Cu into Mat350 (

Figure 3c) resulted in Cu enrichment of the Ni-based phase and primary α-Al dendrites without the formation of Cu-based phases.

Figure 3d depicts the typical microstructure of GCI, which was used as a comparative material to represent the traditional automotive brake discs. This microstructure consisted of graphite flakes and manganese sulfide (MnS) particles embedded within the pearlitic matrix (

Figure 3d). The various microstructural constituents of these materials are expected to significantly influence the tribological behavior of different materials in terms of mechanical, friction, thermal, and wear behavior.

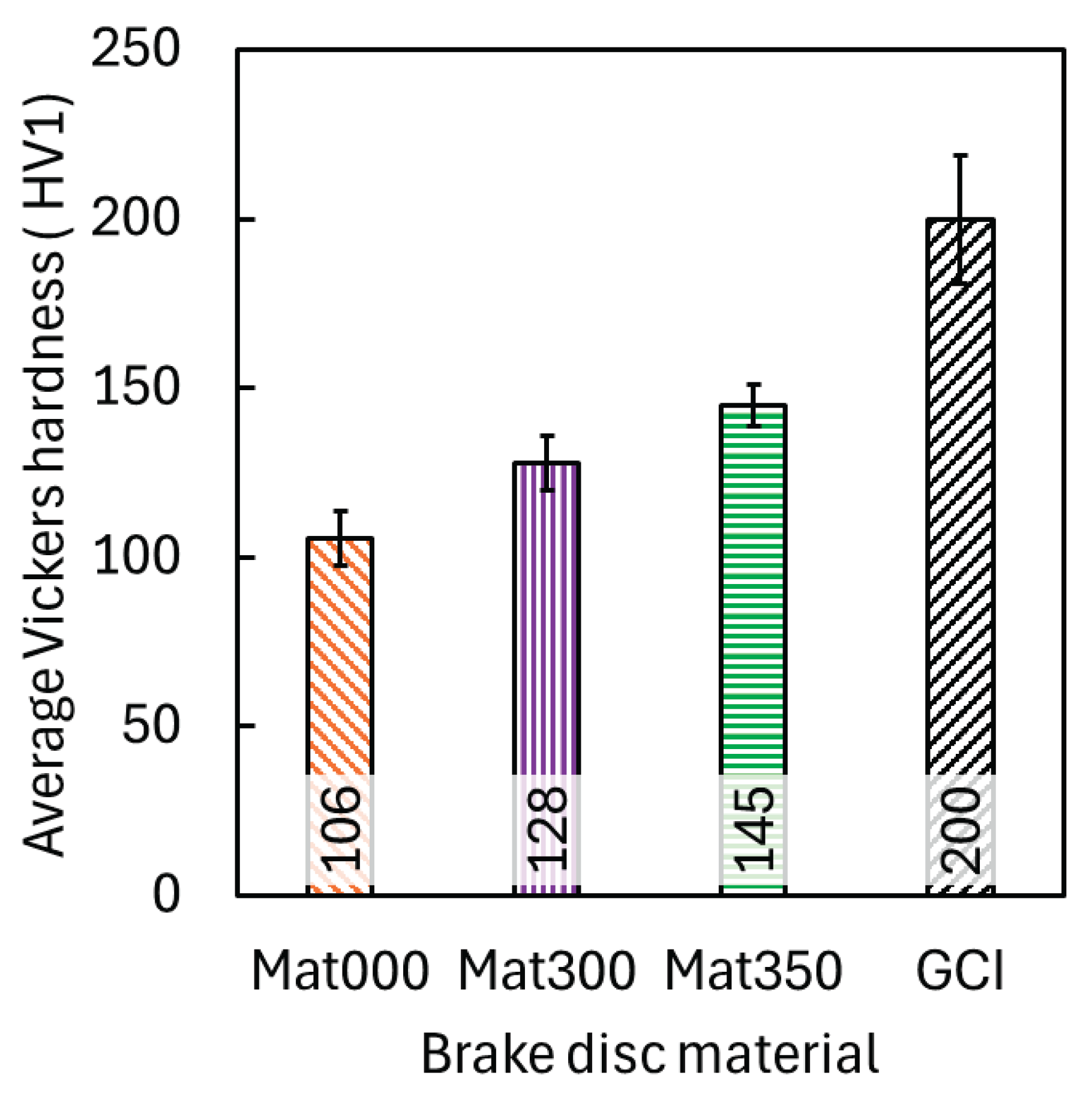

3.2. Microhardness Evaluation of Brake Materials

Figure 4 shows the microhardness distribution across the thickness of the friction surfaces for each brake-rotor material. Fifteen Vickers hardness measurements were taken across each rotor’s thickness, and the average hardness values for these materials are shown in

Figure 4. The average hardness values for Mat000, Mat300, Mat350, and GCI were 106HV1, 128HV1, 145HV1, and 200HV1, respectively. Notably, the microhardness of the GCI brake rotor surpassed that of the Al-MMC brake rotor. However, the hardness of Mat000 (106HV1) is slightly lower than that of Mat300 and Mat350 by 17% and 27%, respectively. The increased hardness observed in Mat300 and Mat350 compared to Mat000 can be attributed to the precipitation of secondary phases, especially Al

3Ni particles, within their microstructures, as discussed in

Section 3.1. Additionally, this enhancement in hardness was partially due to the solid solution strengthening of the aluminum matrices resulting from the incorporation of Cu and Zr, as illustrated in

Table 1. These results corroborate our earlier findings regarding the hardness of these composite materials determined using the Berkovich nanoindentation technique [

3]. The hierarchy of hardness among the primary microstructural components of the composite material was as follows: SiC (34.4 ± 3.7 GPa) < Al

3N (3.85 ± 1.4 GPa) < eutectic Si (2.73 ± 0.4 GPa) < α-Al (1.15 ± 0.1 GPa). Consequently, this hierarchy influences the overall hardness of the composite materials in the following order: Mat000 < Mat300 < Mat350. The results from this study indicate that the microhardness analysis of the aluminum composite materials corresponds closely with previously reported nanohardness tests conducted on these materials.

3.3. Tribological Performance Evaluation

This section examines the impact of variations in testing temperature, pressure, and speed on braking effectiveness, with particular emphasis on analyzing and discussing

Sections 4, 9–12, 14, and 15 of the AK master test protocol, as outlined in

Table 2, for the various brake rotor materials under study. It further compares the braking performance of Al-MMC rotors with that of traditional GCI brake rotors. An NAO brake pad was employed as a friction counterpart for both the composite and GCI rotors. Owing to the differences in thermal resistance between the aluminum composite and GCI rotors, the testing temperature for the Al-MMC discs was maintained within the range of 50-425 °C, whereas the GCI rotor was tested within the temperature range of 100-550 °C. Additionally, an analysis of the surface characteristics of the Al-MMC rotors following dynamometer testing is presented.

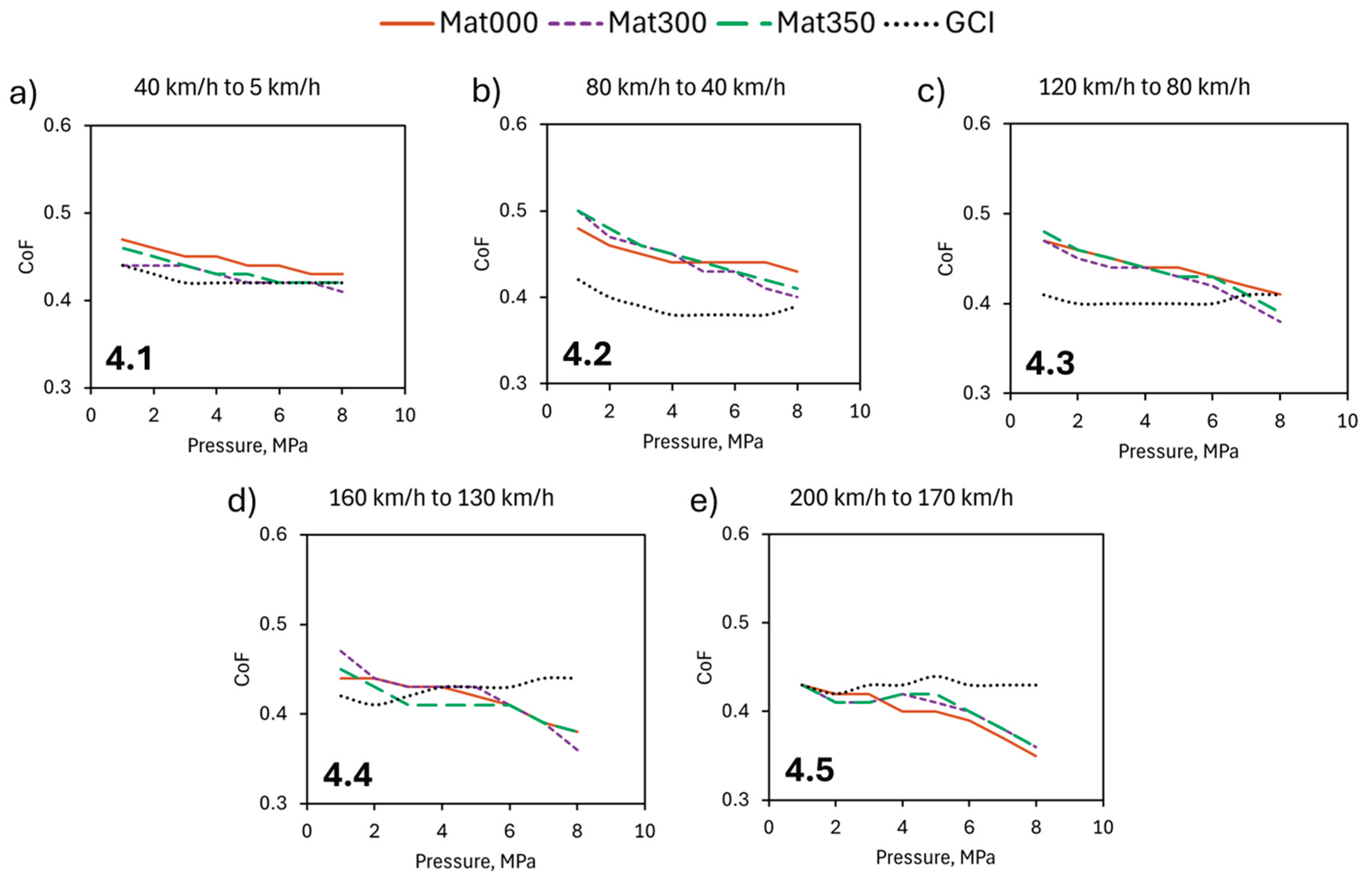

3.3.1. Pressure-Speed Sensitivity

This study investigated the frictional properties of various materials in response to changes in speed and pressure during AK master test cycles.

Figure 5 provides a detailed and accurate representation of the variations in the coefficient of friction (CoF) for different brake rotor materials. The plots presented in the figure illustrate the distinct tribological responses among the Al-MMC variants (Mat000, Mat300, and Mat350) in comparison with conventional GCI rotors. Fundamentally, all Al-MMC variants exhibited similar friction behaviors, characterized by a generally negative slope in the coefficient of the friction-pressure relationship. The Al-MMC rotors displayed higher initial CoFs but demonstrated greater sensitivity to both pressure and speed conditions, with more pronounced decreases at elevated pressures, particularly at high speeds. Conversely, the GCI rotors exhibited a more stable friction coefficient across various pressure ranges and speed conditions, with minimal variation in the CoF, typically ranging from 0.38 to 0.44. The pressure sensitivity of the friction coefficient differed significantly between the Al-MMC and GCI materials. As depicted in

Figure 5 (a)–(e), the Al-MMC variants consistently show a decreasing trend in the friction coefficient with increasing pressure. This negative slope is most pronounced in the high-speed braking scenario (200-170 km/h) illustrated in

Figure 5(e), where the friction coefficient decreases from approximately 0.42 at low pressure to 0.35 at 8 MPa. This behavior is consistent with the findings in the literature, which suggest that, “as the contact pressure increases, the coefficient of friction decreases” owing to the compression of the micro-convex peaks (uneven surfaces) that expand the real contact area [

25]. In contrast, the GCI rotor exhibited a relatively stable friction coefficient, particularly within the high-speed range (

Figure 5e), where the friction coefficient remained nearly constant at approximately 0.43 across the entire pressure range. This stability presents a significant advantage in maintaining consistent braking performance under various pressure conditions. Previous studies have indicated that the stability of the friction coefficient is crucial for predictable braking behavior and reduced brake fade [

26,

27].

The frictional behavior exhibited a significant dependence on the speed. At lower speed ranges, specifically 40-5 km/h and 80-40 km/h, as illustrated in

Figure 5 (a) and (b), all materials display moderate sensitivity to pressure, with friction coefficients generally ranging from 0.38 to 0.47. However, as the speed increases to the 120-80 km/h range (

Figure 5c), the divergence in behavior between the GCI and Al-MMC rotors becomes more pronounced. In the highest speed range (200-170 km/h), as shown in

Figure 5(e), the most notable contrast emerges. While GCI maintains a relatively stable friction coefficient of approximately 0.43, irrespective of pressure, the Al-MMC variants exhibit a significant decrease in the friction coefficient as pressure increases. This behavior is consistent with research findings that suggest that an increased sliding velocity leads to a reduced friction coefficient and wear rate in MMC [

28]. This reduction is attributed to the formation of a compact transfer layer on the worn surface of the MMCs, which is primarily composed of constituents from the counter body material (brake pads).

The observed reduction in the friction coefficient of the Al-MMC rotor variants with increasing pressure can be explained by several tribological mechanisms. At elevated pressures, the increased contact area and temperature facilitated the formation of a protective transfer layer on the Al-MMC surface. The formation of this protective tribolayer is more pronounced under higher loads, leading to a reduced coefficient of friction compared to lower loads [

29]. This transfer layer incorporates constituents from the brake pad material and functions as a lubricant between the sliding surfaces. Second, higher contact pressures can result in increased frictional heat, which can alter the mechanical properties of the contact surfaces. As documented in the literature, “at higher pressure, the heat caused by friction is much higher than the heat transferred to the environment” [

25]. This increase in temperature can diminish the shear strength of the surface material, leading to a reduction in friction. The more significant reduction in the CoF for the Al-MMC rotors at higher speeds, particularly evident in

Figure 5d-e, may also suggest the thermal softening effect of the matrix material. Aluminum composites are more susceptible to the thermal degradation of friction properties than cast iron materials, which may explain the stability of the GCI rotor at higher speeds and pressures [

30]. Furthermore, the interaction between the hard ceramic SiC reinforcements in the Al-MMC brake rotors and the brake pad material changes with pressure. The interaction between the metal fibers of friction materials and an Al-MMC disc differs from that of gray cast iron [

31]. This interaction becomes particularly significant under high-pressure conditions, where hard particles may play a dominant role in controlling friction.

The relative stability of the GCI friction coefficient across pressures and speeds can be attributed to the graphite flakes providing consistent lubrication. This aligns with Österle et al. [

32], who found that graphite lamellae in cast iron provided stable friction films under various loading conditions. The tribolayer formed on the GCI differed from that formed on the Al-MMC, offering more consistent friction characteristics. The stability of the GCI rotor can also be attributed to its higher thermal capacity (i.e., higher volumetric heat capacity), which enables better heat absorption and minimizes thermal gradients [

3,

33].

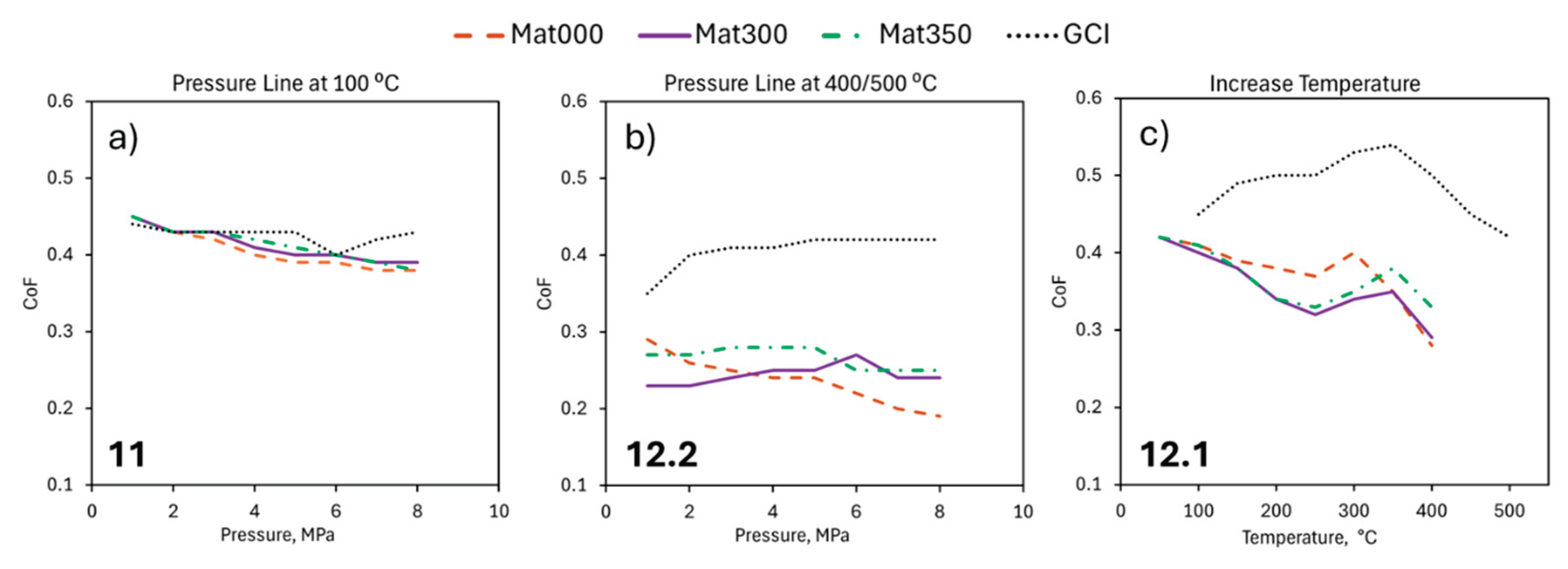

3.3.2. Temperature-Pressure Sensitivity

The impact of pressure and temperature on the frictional properties of the aluminum composites and GCI brake rotors is illustrated in

Figure 6. At a constant temperature of 100 °C (

Figure 6a), the materials tested demonstrated average CoF values ranging from 0.38 to 0.45. The frictional behavior exhibited a relatively low sensitivity to pressure variations between 1 and 8 MPa. The GCI maintains a slightly higher and more stable average CoF compared to the Al-MMC variants, which shows a slight decrease with increasing pressure. This behavior is advantageous for the predictability of brake performance under normal operating temperatures because stable friction characteristics ensure a consistent braking response. The minimal pressure sensitivity at moderate temperatures is consistent with tribological expectations because the contact interfaces have not yet undergone significant thermally induced modifications that would alter the friction mechanisms [

31].

When evaluated at elevated temperatures (

Figure 6b), the materials exhibit more pronounced differences in their frictional behavior. GCI, tested at 500 °C, exhibited a higher coefficient of friction of approximately 0.40-0.42, in contrast to the Al-MMC materials, tested at 400 °C, which displayed average CoF values ranging from 0.20 to 0.30. Mat000 exhibited a noticeable decreasing trend with increasing pressure, whereas Mat300 and Mat350 exhibited relatively stable friction characteristics. The slight friction stability observed in Mat300 and Mat350 compared to Mat000 could be attributed to the presence of heat-resistant alloying elements (Ni and Zr) incorporated into the matrices of these materials, as shown in

Table 1 and explained in

Section 3.1. This variability in the average CoF at high temperatures has significant implications for brake performance under severe service conditions, such as repeated heavy braking or mountain descent [

34]. The substantial changes in the CoF with applied pressure suggest that the interaction between the friction materials and the Al-MMC substrate fundamentally differs from their interaction with gray cast iron [

31]. This is likely due to the presence of reinforcement particles in the MMC, which influence the tribological contact mechanisms.

Figure 6c shows the temperature-dependent friction behavior of the most distinctive differences between the materials. All MMC materials started with similar CoF values (~0.40) at low temperatures, but their behaviors diverged significantly as the temperature increased. The GCI rotor shows exceptional thermal stability, achieving the highest CoF values (0.45-0.53) within the 200-400 °C range. It shows a notable increase in average CoF as the temperature rises, reaching a peak of approximately 0.53 around 350-400 °C before gradually decreasing. This “friction-rise” behavior is particularly advantageous for brake performance, as it provides enhanced stopping power during thermal loading conditions, counteracting potential fade effects [

21,

34]. In contrast, all Al-MMC materials exhibited a general decrease in the coefficient of friction as the temperature increased, indicating potential thermal fading issues during intense braking conditions. Typically, all materials experience a reduction in CoF above 300-400°C, with Al-MMCs exhibiting more significant decreases. The declining CoF observed for Al-MMCs at higher temperatures can be attributed to the softening of the matrix and degradation of the tribolayer above 300 °C [

28,

30,

34]. At 500 °C, the difference in friction performance between GCI (CoF ~0.42) and Al-MMC materials (CoF ~0.28-0.33) becomes evident, highlighting the superior high-temperature friction stability of GCI [

30].

The generally modest impact of pressure at standard operating temperatures indicates that all the materials can sustain predictable braking performance at different application pressures. However, the gray cast iron rotor exhibits superior consistency at elevated temperatures. Although aluminum metal matrix composite rotors offer advantages in weight reduction, their lower coefficient of friction values at higher temperatures suggest potential limitations in high-performance braking applications where thermal loads are substantial.

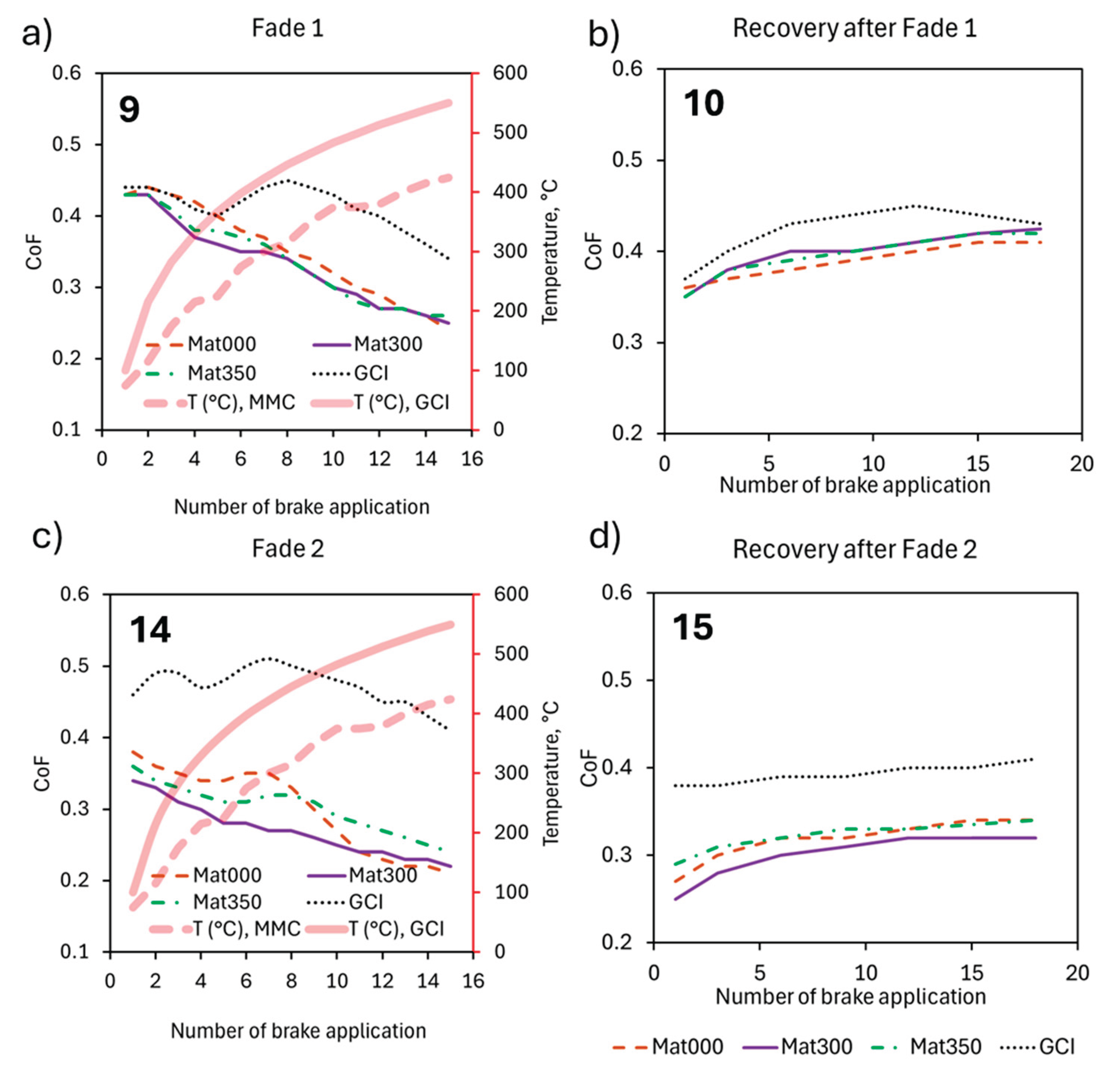

3.3.3. Friction Fade and Recovery Cycles

The data depicted in

Figure 7 offer a detailed tribological analysis comparing the average coefficient of friction behavior of the Al-MMC variants and the GCI brake rotor during the fade (at 40% deceleration) and recovery test cycles conducted in accordance with the AK master protocol. During the initial fade cycle (

Figure 7a), all Al-MMC variants exhibited a marked decrease in the coefficient of friction as the temperature increased from approximately 100 °C to 425 °C. The initial CoF values for the Al-MMC materials, ranging from approximately 0.42 to 0.45, progressively declined to around 0.24 to 0.25 after 15 brake applications. This substantial reduction, approximately 40-45%, indicates a significant sensitivity to thermal effects, a characteristic common to many aluminum-based composites [

28,

30,

35]. In contrast, the GCI brake rotor (

Figure 7a) exhibited superior thermal stability, beginning with a coefficient of friction of approximately 0.44, which decreased to approximately 0.37 by the conclusion of the fade cycle, indicating a modest reduction of 16%. This inherent thermal stability of GCI aligns with its prevalent application in conventional braking systems and can be attributed to its microstructural characteristics and graphite flake morphology [

30,

32]. The second fade cycle (

Figure 7b) reveals notable differences in the material behavior. The Al-MMC-variant rotors had slightly lower CoF values than those in Fade 1, suggesting potential residual thermal effects or microstructural alterations from the preceding test cycle. Mat350 exhibited a marginally enhanced fade resistance relative to its performance in the initial fade test, possibly indicating beneficial microstructural stabilization following the initial thermal cycle. GCI demonstrates even superior performance during Fade 2, with higher initial CoF values (approximately 0.47-0.50) and maintaining relatively stable friction characteristics throughout the test. The enhanced CoF stability observed during repeated thermal cycling, which may be attributed to GCI having a higher volumetric heat capacity than Al-MMC [

3,

36], represents a significant advantage for braking applications that require consistent performance under severe conditions [

37].

The recovery characteristics observed following the initial fade cycle (

Figure 7c) illustrate the capacity of the materials to restore their frictional properties after thermal exposure. All materials demonstrated progressive recovery of the CoF with an increasing number of brake applications, indicating the restoration of tribological properties as the system cooled. Notably, the GCI rotor achieved the highest recovery value, peaking at approximately 0.45, thereby exhibiting superior thermal reversibility [

37]. Among the Al-MMC variants, Mat350 exhibited the most effective recovery performance, followed by Mat000 and Mat300. This hierarchy may indicate compositional or microstructural differences among the Al-MMC variants that affect their thermal recovery characteristics. The disparity between the highest performing Al-MMC (Mat350) and GCI remains evident, with the GCI rotor maintaining approximately 8-10% higher CoF values throughout the recovery phase. The recovery observed following the second fade cycle (

Figure 7d) demonstrates a more pronounced disparity in performance between the materials. GCI consistently exhibited substantially higher CoF values (approximately 0.38-0.41) throughout the recovery phase in comparison to the Al-MMC variants. The Al-MMC materials exhibited lower initial CoF values during the second recovery phase than during Recovery 1 (

Figure 7c), indicating potential cumulative degradation or tribological surface modifications resulting from repeated thermal cycling [

38]. The recovery trajectory for all materials followed a similar pattern of gradual improvement; however, GCI consistently outperformed the Al-MMC variants owing to its higher resistance to elevated temperatures [

1,

30,

39], maintaining approximately 15-20% higher CoF values throughout this recovery phase. This performance differential is particularly significant for braking applications, where consistent recovery characteristics are crucial for predictable vehicle handling [

21,

37].

The experimental results unequivocally demonstrated the superior thermal stability and fade resistance of the GCI compared to the tested Al-MMC variants. This thermal advantage of GCI can be attributed to several factors, including its higher thermal conductivity, which facilitates enhanced heat dissipation, and its graphitic microstructure, which provides inherent lubrication properties at elevated temperatures [

40,

41]. The more pronounced fade behavior observed in Al-MMC materials is consistent with previous studies on aluminum-based brake materials, which have identified challenges with thermal management despite their weight advantages. Jang et al. [

42] identified comparable thermal sensitivity in metal matrix composites employed in braking applications, emphasizing that material formulation plays a crucial role in determining high-temperature friction stability. The recovery patterns observed in these experiments provide valuable insights into the tribological mechanisms that influence brake performance. The superior recovery behavior of the GCI may indicate more reversible surface interactions during the braking process. When brake materials are exposed to elevated temperatures, various phenomena can occur, including oxidation, transfer film formation, and microstructural transformations [

37]. The data indicate that the GCI rotor undergoes more reversible transformations, thereby enhancing its ability to effectively recover its friction properties. In contrast, the Al-MMC materials exhibited lower recovery values, which may suggest less reversible surface transformations. This could potentially involve more permanent oxidation of the aluminum matrix or degradation of the interface between the matrix and reinforcement materials. Kchaou et al. [

37] emphasized that recovery characteristics are crucial for braking safety because they influence the predictability of a brake system’s performance following exposure to high temperatures.

3.3.4. Wear and Surface Degradation

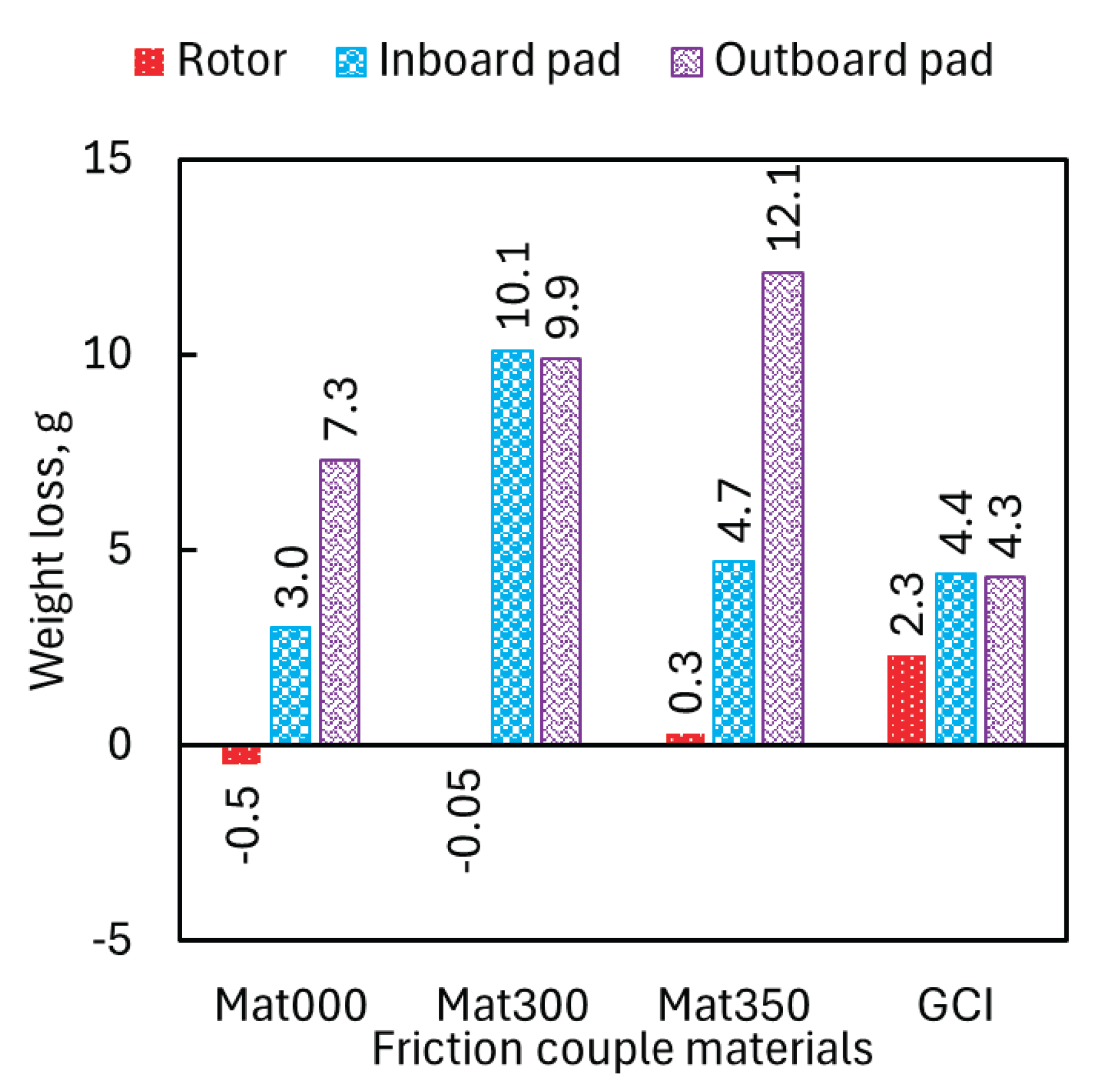

Figure 8 illustrates the weight loss measurements for various friction pairs, specifically brake rotors and pads, as determined using the AK master test procedure. The data presented in this figure offer significant insights into the tribological and braking performances of the different materials used in this investigation. Notably, as shown in

Figure 8, the most prominent observation was the differential wear behavior exhibited between the rotors and brake pads across the tested materials. The wear data indicate negative weight loss values for the Al-MMC rotors, specifically Mat000 (-0.5 g) and Mat300 (-0.05 g), whereas Mat350 exhibits minimal positive wear (0.3 g), whereas the GCI rotor (2.3 g) shows conventional positive wear patterns. The negative wear suggests material transfer from the brake pads to the rotor surface, a phenomenon well-documented in the tribology of aluminum matrix composites [

28,

29]. This material transfer results in the formation of a protective tribofilm, fundamentally altering the wear mechanism from abrasive material removal to the development of a protective layer.

The formation of transfer layers on Al-MMC surfaces occurs through a complex tribochemical process in which brake pad constituents, including organic binders, metallic fibers, and ceramic particles, become mechanically and chemically bonded to the aluminum matrix surface [

28,

29].

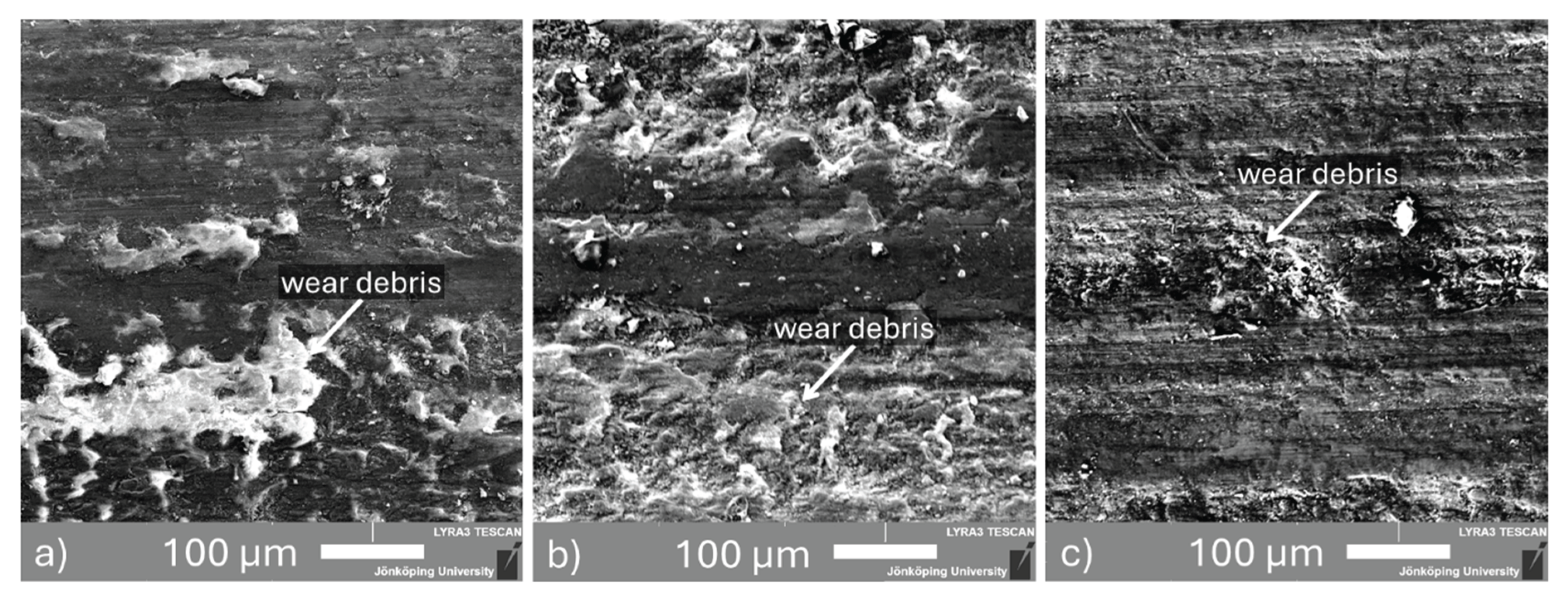

Figure 9 presents the SEM images of the worn surface on the discs after the AK master test. The wear debris adhered to the surface of all the composites investigated. Mat000 (

Figure 9a) and Mat300 (

Figure 9b) exhibited a comparable appearance of a compact and thick tribolayer along the sliding direction. The tribolayer was not continuous on the entire surface, with portions of the composite surface exposed and portions of the tribolayer distributed unevenly, suggesting that the layer was removed and formed again during the wear process. Mat350 (

Figure 9c) presents wear debris that appears particulate and dusty and less compact than the other composites. The appearance of the tribolayer on a microscale can depend on the presence of hard phases in the matrix, such as the Ni-based phases in Mat350, which present an overall higher hardness compared to the other composites.

The protective role of this transfer layer is evident in its ability to reduce both the wear rate and friction coefficient compared with bare aluminum surfaces. This is demonstrated by the negative wear of the Al-MMC rotors (

Figure 8) and the lower CoFs shown in

Figure 7d.

An important characteristic observed in

Figure 8 is the significant asymmetry in pad wear between the outboard and inboard pads across various Al-MMC formulations. For Mat300, both the outboard (9.9 g) and inboard (10.1 g) pads exhibited similarly high wear rates. In contrast, Mat000 and Mat350 exhibited significant differences in wear between the outboard and inboard pads. This asymmetric wear behavior can be attributed to variations in the contact pressure distribution, thermal gradients, influence of protruding hard SiC particles, rotor surface roughness after aggressive thermal loads, and local tribological conditions within the brake caliper assembly. The high pad wear rates observed in certain Al-MMC variants, particularly Mat350 with an outboard pad wear of 12.1 g, suggest that while the rotor surface is protected by the formation of a transfer layer, the brake pad material undergoes accelerated consumption. This phenomenon aligns with the findings indicating that Al-MMC discs can demonstrate superior wear resistance compared to conventional materials when the structure and composition of the lining material (brake pad) are optimally configured [

28,

29].

The fundamental difference in the wear behavior between the Al-MMC and GCI rotors highlights distinct tribological mechanisms. The GCI rotors exhibit conventional abrasive wear, evidenced by a positive weight loss of 2.3 g, while maintaining relatively consistent pad wear at both the outboard (4.3 g) and inboard (4.4 g) positions (

Figure 8). This balanced wear distribution in the GCI rotor-pad system suggests a more traditional two-body abrasive wear mechanism, in which both surfaces contribute to material removal. Typically, GCI brake discs operate via a well-established tribological mechanism involving the formation of tribofilms primarily composed of iron oxides [

43]. The graphite flakes in the GCI rotor serve as solid lubricants, forming tribo-films that reduce both friction and wear under dry sliding conditions [

30,

32,

44]. The presence of graphite created a more stable tribological interface, resulting in the observed balanced wear distribution between the rotor and pads, as shown in

Figure 8. The negative wear values observed in the Al-MMC rotors suggest the formation of stable transfer layers that offer protective coverage, as is evident from their surface appearances in

Figure 10. These transfer layers are formed through compaction galling, where brake pad debris accumulates in the surface dimples and becomes mechanically interlocked with the rotor surface [

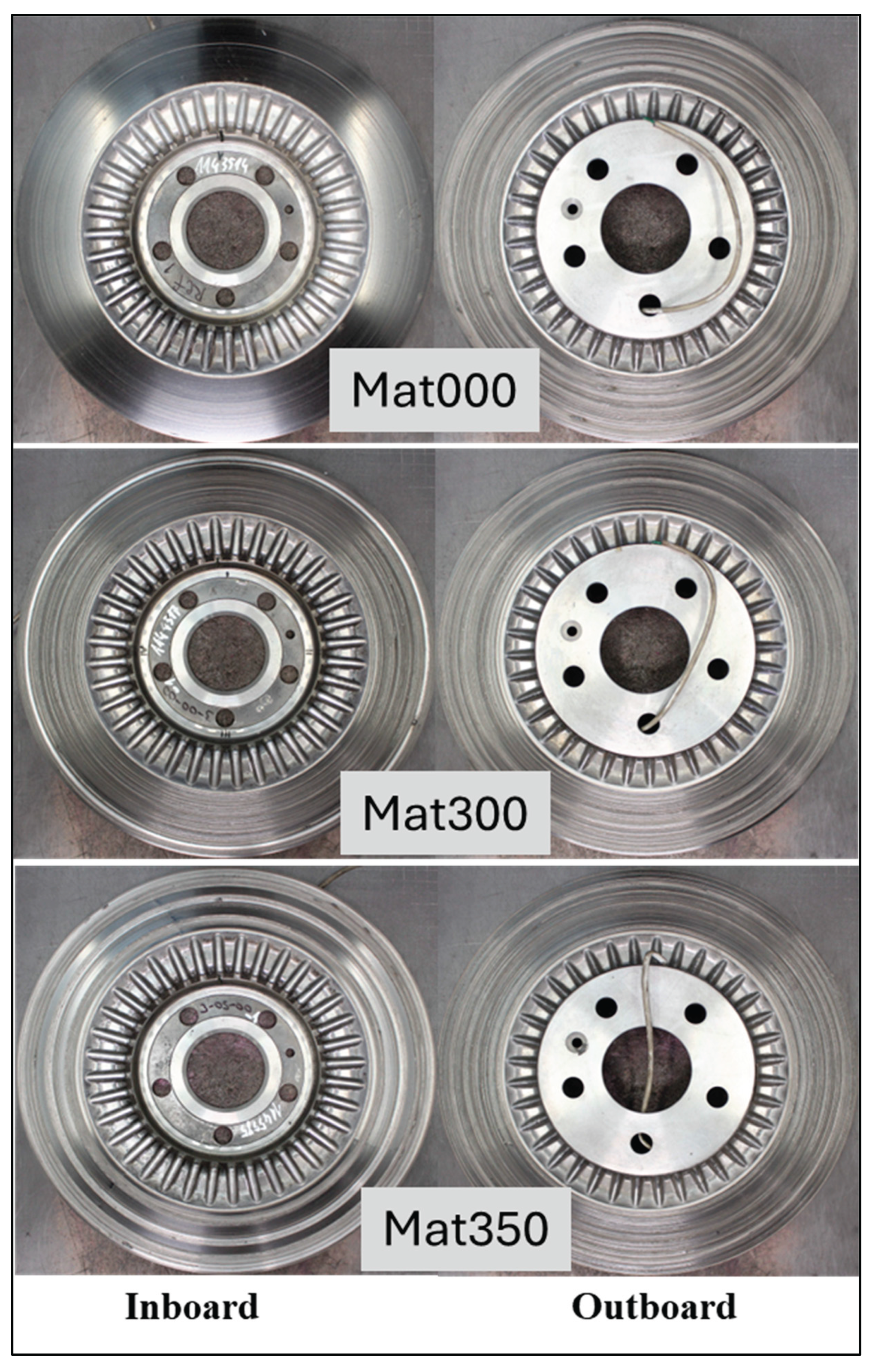

45]. The dimpled surface morphology typical of processed Al-MMC materials enhances the bonding of the transfer layer through mechanical interlocking mechanisms.

Figure 10 depicts the surface appearance of all Al-MMC rotors following the implementation of the aggressive AK master test protocol. It should be noted that the surface condition of the GCI rotor was not documented during this test. The figure illustrates several distinctive characteristics of the friction surfaces of the aluminum composite brake rotor variants. For rotor Mat000, the friction surface was relatively smooth, exhibiting minimal visible wear marks or scores. The surface appears uniform, indicating a less aggressive material interaction. No significant grooves or deep scratches were evident, suggesting lower material transfer or abrasive wear during testing. The surface characteristics of the friction interfaces of Mat300 exhibited more pronounced wear marks than those of Mat000. The observable scratches and slight discoloration suggest increased friction and heat generation. The presence of light scoring indicates a higher degree of abrasive wear, which is likely attributable to variations in the hardness of the composite material or its interaction with brake pads. In contrast, the friction surfaces of Mat350 demonstrated the most significant wear, characterized by deeper scratches, more pronounced scoring, and areas of discoloration. The surface appears rougher than that of the other two variants. The increased scoring and roughness imply higher abrasive wear and potentially more substantial material transfer between the rotor and brake pad. This could suggest higher friction but also greater wear on the rotor surface (Mat350), as shown in

Figure 8.

From the tribological perspective, the smoother appearance of the Mat00 friction ring suggests better wear resistance and a lower friction coefficient, leading to less material loss. However, this may also indicate a lower grip with the brake pads, potentially reducing braking efficiency under high-stress conditions. The moderate wear and scoring of Mat300 suggest a balanced tribological performance. The material may likely provide a higher friction coefficient than Mat000, improving the grip with the brake pads, but at the cost of increased wear. The rougher surface and deeper scoring in Mat350 indicate a higher friction coefficient, which could enhance braking performance by improving the pad-rotor interaction. However, the increased wear suggests poorer durability, as the rotor may degrade faster over time, potentially leading to more frequent replacement. These observations align closely with the wear patterns depicted in

Figure 8 and the friction behavior reported in

Figure 7d. Overall, all the Al-MMC variants exhibited a relatively uniform friction surface appearance, indicating consistent pad-to-rotor contact during the AK master test protocol.

3.4. Practical Implications for Braking Performance

Aluminum metal matrix composite (Al-MMC) and gray cast iron (GCI) brake rotors exhibit distinct performance characteristics and trade-offs within braking systems. This study presents a structured comparison of their practical braking performance implications, as derived from the findings of this investigation.

Thermal capacity and heat dissipation: The superior thermal conductivity of aluminum compared to cast iron offers substantial benefits in brake thermal management [

3]. Al-MMC brake rotors exhibit a 25% higher rate of heat dissipation relative to cast iron rotors, leading to a more uniform thermal distribution and a reduction in the formation of hot spots, which are commonly observed in GCI rotors. This improved thermal performance contributes to more consistent braking behavior, diminished thermal stress-induced distortion, reduced thermal fade during repeated braking, and facilitates quicker recovery between braking events, which is advantageous in performance-driving scenarios. Nonetheless, the incorporation of ceramic reinforcements into Al-MMCs can pose challenges to their thermal conductivity because ceramic particles possess a significantly lower thermal conductivity than the aluminum matrix [

3,

36]. This thermal disparity necessitates careful optimization of the reinforcement content and distribution to ensure adequate heat dissipation while maintaining the mechanical properties. Conversely, the higher thermal capacity (volumetric thermal capacity) of GCI rotors enables superior heat absorption during intense braking, as observed in this investigation. This characteristic ensures a more consistent performance during repeated heavy braking events, rendering GCI rotors ideal for heavier vehicles and high-load applications.

Friction stability and performance consistency: The formation of stable transfer layers on the Al-MMC rotors, as observed in this study, contributed to more consistent friction coefficients throughout the braking cycle. These findings indicate that the Al-MMC brake discs can sustain stable friction coefficients while demonstrating superior wear resistance compared to conventional materials. The generally modest impact of pressure at standard operating temperatures (lower than 500 °C) suggests that all Al-MMC variants can maintain predictable braking performance across different application pressures. The evolution of the tribological interface during braking influences the stability of the friction coefficient through the dynamic formation and reformation of the contact plateaus. However, the capacity of Al-MMC surfaces to accommodate transfer materials and sustain stable tribological interfaces contributes to reduced brake fade and more predictable braking performance under varying conditions. The consistently stable CoF of the GCI rotor under aggressive and repeated braking events renders it superior to the Al-MMC rotor for extreme temperature (up to 700 °C) brake applications owing to its inherent thermal stability.

Weight considerations: The GCI rotor possesses a significantly higher density of approximately 7.2 g/cm³, which contributes to increased unsprung weight, thereby adversely affecting vehicle dynamics, acceleration, and fuel efficiency. In contrast, Al-MMC rotors exhibit a substantially lower density of approximately 2.8 g/cm³, resulting in a reduction of rotational inertia and unsprung weight by 50-60%. This reduction leads to enhanced handling, acceleration, and fuel economy, with an estimated improvement of 1-2% in overall vehicle efficiency. The reduced weight of the Al-MMC rotors makes them viable candidates for electric vehicle applications, where both weight reduction and corrosion resistance are prioritized.

Wear resistance and dust generation: The findings of this study suggest that the GCI rotor exhibited a higher wear rate, evidenced by a 2.3 g weight loss in the AK master dynamometer test, when used in conjunction with an NAO friction material. This observation indicates that the GCI disc produces substantial dust, necessitating further modification of the friction surfaces of the GCI rotor to improve wear resistance and comply with Euro 7 emission-generation standards. The balanced wear characteristics of the GCI are likely associated with more stable friction coefficients during braking; more predictable thermal behavior; potentially superior noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH) performance; and more uniform pressure distribution and thermal management across the brake assembly. These factors typically result in a more consistent brake torque and pedal feel during operation. In contrast, the Al-MMC rotors exhibited negative or nearly zero wear characteristics compared to the GCI rotor. This indicates that the hybrid Al-SiC MMC rotors had superior wear resistance, leading to a reduction in particulate emissions by 86.9-121.7% compared to the GCI rotors. Although the negative weight loss in Al-MMC materials may contribute to an extended rotor lifespan, the associated asymmetrical pad wear could potentially undermine the overall system reliability and performance consistency. Specialized pad formulations are required to prevent excessive wear; however, with appropriate engineering, comparable lifespans can be achieved. Al-MMC rotors are particularly advantageous for applications that prioritize weight reduction, environmental impact, and low wear. Nevertheless, GCI remains preferable for high-stress, high-temperature conditions that require uncompromised thermal stability. Advances in coating technologies, such as plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) and high-velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF), along with hybrid Al-MMC designs, can reduce performance disparities, thereby enhancing the viability of Al-MMC for mainstream automotive adoption, particularly for electric vehicle applications where frictional brake systems are less frequently used.

Long-term durability and maintenance considerations: The wear data indicate that Al-MMC brake rotors have the potential to endure the entire lifespan of a vehicle owing to their exceptional wear resistance and the formation of a protective transfer layer. Nevertheless, this benefit is accompanied by increased brake pad consumption, particularly for specific formulations such as Mat350. This trade-off necessitates careful evaluation of the overall system cost and maintenance requirements. The selection of the rotor variant depends on the intended application. For general use, where durability is prioritized, Mat000 is preferable owing to its lower wear rate, although it may compromise braking power. In contrast, for performance-oriented applications where stopping power is paramount, Mat350 is superior; however, its higher wear rate suggests that it is more suitable for scenarios where rotors can be replaced more frequently. Mat300 provides a balance between braking performance and durability, rendering it a versatile option for a wide range of conditions. To optimize performance, pairing these rotors with brake pads that complement their friction characteristics could further enhance overall braking efficiency and longevity.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive comparative evaluation of squeeze-cast aluminum metal matrix composite (Al-MMC) brake rotors and conventional gray cast iron (GCI) rotors using the AK-Master dynamometer protocol. The investigation emphasizes the tribological performance, wear mechanisms, and practical implications for automotive brake applications. The principal conclusions of this study are as follows:

The Al-MMC rotors exhibited stable coefficients of friction (CoFs) under moderate temperature and pressure conditions, with initial CoF values comparable to those of GCI rotors. Nevertheless, the Al-MMC rotors displayed pressure and speed-sensitive friction coefficients (0.35–0.47), which decreased at higher pressures and speeds. In contrast, the GCI rotors maintained a more consistent friction response (0.38–0.44) across all tested conditions.

At elevated temperatures, GCI rotors demonstrate superior performance compared with Al-MMC variants, exhibiting enhanced thermal stability and resistance to fade. GCI maintained a higher and more stable CoF during repeated high-temperature braking cycles, whereas Al-MMC rotors experienced significant fade, with a reduction in CoF of up to 40–45%, and demonstrated less effective recovery following thermal exposure. The thermal fade resistance of GCI was notably superior, retaining 84% of the initial CoF at 500 °C, in contrast to the 40–60% loss of Al-MMC at 400 °C.

The incorporation of ceramic reinforcements, specifically silicon carbide (SiC), along with alloying elements such as nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), and zirconium (Zr), into Al-MMCs has been shown to enhance both hardness and wear resistance. Nevertheless, the thermal softening of the aluminum matrix at elevated temperatures poses a limitation to the friction stability. The predominant wear mechanisms observed in Al-MMCs are abrasive and oxidative, with the protective tribolayer playing a pivotal role in mitigating wear.

Al-MMC rotors present a significant reduction in density, approximately 50–60% lower than GCI, resulting in enhanced vehicle dynamics, improved fuel efficiency, and a reduction in particulate emissions by 87–122% compared to GCI. This characteristic renders Al-MMCs particularly advantageous for vehicle applications that prioritize weight reduction and environmental compliance, particularly in urban and electric vehicle contexts.

These findings highlight the potential of squeeze-cast Al-MMCs for automotive braking applications, offering benefits in terms of weight reduction and wear resistance. However, they also indicate the necessity for further material optimization to improve the high-temperature performance and friction stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and L.L.; methodology, S.A.; validation, S.A. and L.L.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, S.A. and L.L.; resources, S.A. and L.L.. Data curation, S.A. and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, L.L.; visualization, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Stiftelsen för kunskaps- och kompetensutveckling (KK-Stiftelsen), Sweden, through the project “Properties and formability of Al-SiCp MMCs” (ProForAl) [Prospekt, diarienr. 20200217].

Data Availability Statement

The authors will supply research data upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. R. Westergård from Gränges Finspång AB for supplying master alloys, as well as Dr. P. Jansson from Comptech i Skillingaryd AB and C. Rudenstam from Husqvarna AB participated in the ProForAl Project. We gratefully acknowledge Prof. A. Jarfors, Prof. E. Ghassemali and Prof. J-E. Ståhl for their advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Awe SA. Evaluating the Impact of Natural Ageing and Stress-Relief Heat Treatment on Grey Cast Iron Rotor’s Resonant Frequency, Damping Characteristics, and Hardness: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Metalcasting 2025 2025:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Awe SA. Developing Material Requirements for Automotive Brake Disc. Modern Concepts in Material Science Science 2019;2:1–4. https://doi.org/MCMS.MS.ID.000531.

- Lattanzi L, Awe SA. Thermophysical properties of Al-based metal matrix composites suitable for automotive brake discs. Journal of Alloys and Metallurgical Systems 2024;5:100059. [CrossRef]

- Ghouri I, Barker R, Brooks P, Kosarieh S, Barton D. The Effects of Corrosion on Particle Emissions from a Grey Cast Iron Brake Disc. SAE Technical Papers, SAE International; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gweon J, Shin S, Jang H, Lee W, Kim D, Lee K. The Factors Governing Corrosion Stiction of Brake Friction Materials to a Gray Cast Iron Disc. SAE Technical Papers 2018;2018-October. [CrossRef]

- Uyyuru RK, Surappa MK, Brusethaug S. Tribological behavior of Al-Si-SiCp composites/automobile brake pad system under dry sliding conditions. Tribol Int 2007;40:365–73. [CrossRef]

- Awe SA, Thomas A. The Prospects of Lightweight SICAlight Discs in the Emerging Disc Brake Requirements. Eurobrake 2021, FISITA; 2021, p. 1–6.

- Sajjadi SA, Ezatpour HR, Beygi H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al–Al2O3 micro and nano composites fabricated by stir casting. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2011;528:8765–71. [CrossRef]

- Gill RS, Samra PS, Kumar A. Effect of different types of reinforcement on tribological properties of aluminium metal matrix composites (MMCs) – A review of recent studies. Mater Today Proc 2022;56:3094–101. [CrossRef]

- Alam MA, Ya HB, Azeem M, Mustapha M, Yusuf M, Masood F, et al. Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review. Nanotechnol Rev 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Dhanashekar M, Senthil Kumar VS. Squeeze casting of aluminium metal matrix composites - An overview. Procedia Eng 2014;97:412–20. [CrossRef]

- Zyska A, Boron K. Comparison of the Porosity of Aluminum Alloys Castings Produced by Squeeze Casting. Manufacturing Technology 2021;21:725–34. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan S, Xavior MA. Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Aluminum Alloy Metal Matrix Composite by Squeeze Casting-A Review. Mater Today Proc 2018;5:11175–84. [CrossRef]

- Limpert R. Brake Design and Safely. Third. SAE International; 2011.

- Chan D, Stachowiak GW. Review of automotive brake friction materials. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2004;218:953–66. [CrossRef]

- Awe S, Eilers E, Gulden F. Sustainable aluminium brake discs and pads for electrified vehicles. Sustainable brake components, EuroBrake 2023, 2023, p. 1–10.

- Wu H, Zhang H, Gao A, Gong L, Ji Y, Zeng S, et al. Friction and wear performance of aluminum-based self-lubricating materials derived from the 3D printed graphite skeletons with different morphologies and orientations. Tribol Int 2024;195:109614. [CrossRef]

- Ye W, Shi Y, Zhou Q, Xie M, Wang H, Bou-Saïd B, et al. Recent advances in self-lubricating metal matrix nanocomposites reinforced by carbonous materials: A review. Nano Materials Science 2024;6:701–13. [CrossRef]

- SAE J2522. Inertia Dynamometer Disc and Drum Brake Effectiveness Test Procedure. 400 Commonwealth Drive, Warrendale, PA, United States: SAE International; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Wang J, Cao F, Ma Y. Comparative braking performance evaluation of a commercial and non-asbestos, cu-free, carbonized friction composites. Medziagotyra 2021;27:197–204. [CrossRef]

- Day A, Bryant D. Braking of Road Vehicles. Second. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lattanzi L, Etienne A, Li Z, Manjunath T, Nixon N, Jarfors AEW, et al. The influence of Ni and Zr additions on the hot compression properties of Al-SiCp composites. J Alloys Compd 2022;905:164160. [CrossRef]

- Lattanzi L, Etienne A, Li Z, Chandrashekar GT, Reddy Gonapati S, Awe SA, et al. The effect of Ni and Zr additions on hardness, elastic modulus and wear performance of Al-SiCp composite. Tribol Int 2022;169:107478. [CrossRef]

- Storstein T, Kuylenstierna C, Kalmi J. Friction member and a method for its surface treatment. US6821447, 2004.

- Utama BP. Frictional Characterization Of Grey Cast Iron Train Brake Block Using A Reduced Scale Dynamometer. Mekanika: Majalah Ilmiah Mekanika 2022;21:31. [CrossRef]

- Aleksendrić D, Barton DC, Vasić B. Prediction of brake friction materials recovery performance using artificial neural networks. Tribol Int 2010;43:2092–9. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Li Z, Wen G, Gao Z, Li Y, Li Y, et al. Sepiolite: A new component suitable for 380 km/h high-speed rail brake pads. Advanced Powder Materials 2024;3:100199. [CrossRef]

- Shorowordi KM, Haseeb ASMA, Celis JP. Velocity effects on the wear, friction and tribochemistry of aluminum MMC sliding against phenolic brake pad. Wear 2004;256:1176–81. [CrossRef]

- Lyu Y, Wahlström J, Tu M, Olofsson U. A friction, wear and emission tribometer study of non-asbestos organic pins sliding against alsic mmc discs. Tribology in Industry 2018;40:274–82. [CrossRef]

- Blau PJ. Compositions, functions, and testing of friction brake materials and their additives ORNL-27 (4-00). Tennessee: 2001.

- Jang H, Ko K, Kim SJ, Basch RH, Fash JW. The effect of metal fibers on the friction performance of automotive brake friction materials. Wear 2004;256:406–14. [CrossRef]

- Österle W, Prietzel C, Kloß H, Dmitriev AI. On the role of copper in brake friction materials. Tribol Int 2010;43:2317–26. [CrossRef]

- Aranke O, Algenaid W, Awe S, Joshi S. Coatings for Automotive Gray Cast Iron Brake Discs: A Review. Coatings 2019, Vol 9, Page 552 2019;9:552. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović N, Abdullah OI, Schlattmann J, Grujić I, Glišović J. Investigation of the penetration and temperature of the friction pair under different working conditions. Tribology in Industry 2020;42:288–98. [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi H, Kakihara K, Nakayama A, Murayama T. Development of aluminum metal matrix composites (Al-MMC) brake rotor and pad. JSAE Review 2002;23:365–70. [CrossRef]

- Lattanzi L, Mohammadpour Kasehgari S, Awe SA. The influence of SiC particle reinforcement on the thermophysical properties of aluminium-based metal matrix composites. J Therm Anal Calorim 2025:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kchaou M, Sellami A, Fajoui J, Kus R, Elleuch R, Jacquemin F. Tribological performance characterization of brake friction materials: What test? What coefficient of friction? Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part J: Journal of Engineering Tribology 2019;233:214–26. [CrossRef]

- Haley J, Cheng K. Investigation into precision engineering design and development of the next-generation brake discs using Al/SiC metal matrix composites. Nanotechnology and Precision Engineering 2021;4. [CrossRef]

- Awe SA. Effects of stress-relief and natural aging on the geometric tolerances and functional requirements of ferritic nitrocarburized gray cast iron brake rotors. Discover Mechanical Engineering 2024 3:1 2024;3:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Gigan G, Norman V, Ahlström J, Vernersson T, Gigan G. Thermomechanical fatigue of grey cast iron brake discs for heavy vehicles. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part D, Journal of Automobile Engineering n.d.;233:453–67. [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Chen X, Li Y, Liu Z. Effects of Inoculation on the Pearlitic Gray Cast Iron with High Thermal Conductivity and Tensile Strength. Materials 2018;11:1876. [CrossRef]

- Jang H, Ko K, Kim SJ, Basch RH, Fash JW. The effect of metal fibers on the friction performance of automotive brake friction materials. Wear 2004;256:406–14. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson S, Hogmark S. Tribofilms – On the crucial importance of tribologically induced surface modifications. In: Nikas GK., editor. Recent developements in wear prevention, friction, and lubrication, Research Signpost; 2010, p. 314.

- Kumar C, Reddy R, Jayasankar S. Tribological performance of ferritic nitrocarburizing (FNC) treated automotive brake discs. Lund University, 2021.

- Cai R, Zhang J, Nie X, Tjong J, Matthews DTA. Wear mechanism evolution on brake discs for reduced wear and particulate emissions. Wear 2020;452–453:203283. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Representative photographs of (a) the MMC and (b) the GCI brake rotors before the test, showing the outboard and inboard friction surfaces of the rotors.

Figure 1.

Representative photographs of (a) the MMC and (b) the GCI brake rotors before the test, showing the outboard and inboard friction surfaces of the rotors.

Figure 2.

A section of the test rigg showing the mounted brake rotor and caliper.

Figure 2.

A section of the test rigg showing the mounted brake rotor and caliper.

Figure 3.

Microstructure of the investigated materials: (a) Mat000; (b) Mat300; (c) Mat350; (d) GCI.

Figure 3.

Microstructure of the investigated materials: (a) Mat000; (b) Mat300; (c) Mat350; (d) GCI.

Figure 4.

Microhardness (HV1) of the investigated brake rotor materials.

Figure 4.

Microhardness (HV1) of the investigated brake rotor materials.

Figure 5.

Variation in the average coefficient of friction (CoF) for Al-MMC (Mat000, Mat300, and Mat350) and GCI brake rotors as the pressure increased across five specified speeds: (a) from 40 km/h to 5 km/h, (b) from 80 km/h to 40 km/h, (c) from 120 km/h to 80 km/h, (d) from 160 km/h to 130 km/h, and (e) from 200 km/h to 170 km/h, in accordance with the AK master test protocol.

Figure 5.

Variation in the average coefficient of friction (CoF) for Al-MMC (Mat000, Mat300, and Mat350) and GCI brake rotors as the pressure increased across five specified speeds: (a) from 40 km/h to 5 km/h, (b) from 80 km/h to 40 km/h, (c) from 120 km/h to 80 km/h, (d) from 160 km/h to 130 km/h, and (e) from 200 km/h to 170 km/h, in accordance with the AK master test protocol.

Figure 6.

Variation in average CoF of Al-MMCs (Mat000, Mat300, and Mat350) and GCI brake rotors with pressure at (a) 100 °C, (b) 400/500 °C, and (c) with increasing temperature according to the AK master test protocol. The numbers indicate AK master test segments.

Figure 6.

Variation in average CoF of Al-MMCs (Mat000, Mat300, and Mat350) and GCI brake rotors with pressure at (a) 100 °C, (b) 400/500 °C, and (c) with increasing temperature according to the AK master test protocol. The numbers indicate AK master test segments.

Figure 7.

Variation in average CoF of Al-MMC (Mat000, Mat300 & Mat350) and GCI brake rotors after Fade 1 (a); Fade 2 (b), Recoveries after Fade 1 (c) and Fade 2 (d) tests according to the AK master test protocol. The numbers indicate AK master test segments.

Figure 7.

Variation in average CoF of Al-MMC (Mat000, Mat300 & Mat350) and GCI brake rotors after Fade 1 (a); Fade 2 (b), Recoveries after Fade 1 (c) and Fade 2 (d) tests according to the AK master test protocol. The numbers indicate AK master test segments.

Figure 8.

Weight loss analysis of the friction couple materials after the AK master dyno test cycles.

Figure 8.

Weight loss analysis of the friction couple materials after the AK master dyno test cycles.

Figure 9.

Surface of the composite materials after the AK master dyno test cycles: a) Mat000, b) Mat300, c) Mat350.

Figure 9.

Surface of the composite materials after the AK master dyno test cycles: a) Mat000, b) Mat300, c) Mat350.

Figure 10.

Surface appearance of Al-MMC brake rotor variants after AK master dyno test.

Figure 10.

Surface appearance of Al-MMC brake rotor variants after AK master dyno test.

Table 1.

Chemical composition [wt%) %] of the investigated materials. .

Table 1.

Chemical composition [wt%) %] of the investigated materials. .

| Al-MMCs |

Si* |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Cr |

Ni |

Ti |

Zr |

Al |

| Mat000 |

17.34 |

0.20 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.34 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.09 |

0.00 |

Bal |

| Mat300 |

20.12 |

0.22 |

0.03 |

0.38 |

0.64 |

0.19 |

3.47 |

0.13 |

0.20 |

Bal |

| Mat350 |

18.50 |

0.17 |

0.48 |

0.11 |

0.55 |

0.02 |

3.44 |

0.11 |

0.05 |

Bal |

Table 2.

Test conditions for the AK Master protocol according to SAE-J2522 Recommended Practice [

19].

Table 2.

Test conditions for the AK Master protocol according to SAE-J2522 Recommended Practice [

19].

| Sections |

Test name |

Conditions |

| 1 |

Green μ characteristic |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 30 stops |

| 2 |

Burnish |

80 → 30 km/h; 1.5–5.1 MPa; 62 stops |

| 3 |

Characteristic value 1 |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 6 stops |

| 4.1 |

Speed-pressure sensitivity |

40 → 5 km/h; 1.0–8.0 MPa; 8 stops |

| 4.2 |

80 → 40 km/h; 1.0–8.0 MPa; 8 stops |

| 4.3 |

120 → 80 km/h; 1.0–8.0 MPa; 8 stops |

| 4.4 |

160 → 130 km/h; 1.0–8.0 MPa; 8 stops |

| 4.5 |

200 → 170 km/h; 1.0–8.0 MPa; 8 stops |

| 5 |

Characteristic value 2 |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 6 stops |

| 6 |

Cold braking |

40 → 5 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 1 stop |

| 7 |

Motorway braking |

100 → 5 km/h; 160 → 10 km/h; 60% deceleration; 2 stops |

| 8 |

Characteristic value 3 |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 18 stops |

| 9 |

Fade 1 |

100 → 5 km/h; 40% deceleration; 15 stops |

| 10 |

Recovery 1 |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 18 stops |

| 11 |

Temperature/pressure sensitivity 100 °C |

80 → 30 km/h; 1.0–5.0 MPa; 8 stops |

| 12.1 |

Temperature/pressure sensitivity 400 - 500 °C |

80 → 30 km/h; 1.0–5.0 MPa; 9 stops; increasing temperature |

| 12.2 |

80 → 30 km/h; 1.0–8.0 MPa; 8 stops; pressure line |

| 13 |

Recovery 2 |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 18 stops |

| 14 |

Fade 2 |

100 → 5 km/h; 40% deceleration; 15 stops |

| 15 |

Recovery 3 |

80 → 30 km/h; 3.0 MPa; 18 stops |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).