Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Aspects of ANM

3. ANM for Elastic Nonlinear Problems

3.1. Theory

3.2. Numerical Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Algorithm ANM |

|

4. ANM for Thermo-Elastic Nonlinear Problems

4.1. Theory

4.2. Numerical Algorithm

5. Some Aspects of the FreeFEM++ Implementation

- FreeFEM++ has a high level user friendly typed input language with an algebra of analytic and finite element functions.

- The finite element problems are described by their variational formulations, and are easily implemented. It is possible to have access to the internal vectors and matrices if needed.

- Many kinds of problems can be solved: multi-variables, multi-equations, one, two or three dimensional static or time dependent, linear or nonlinear coupled systems.

- An automatic mesh generator is available, based on the Delaunay-Voronoï algorithm.

- A large variety of triangular finite elements: linear and quadratic Lagrangian finite elements and more, discontinuous P1, and Raviart-Thomas elements.

- A large variety of linear direct and iterative solvers (LU, Cholesky, Crout, CG, GMRES, UMFPACK, MUMPS, SuperLU, ...), eigenvalue and eigenvector solvers (ARPACK) are available.

- msh3 Th("Th3D.msh");

- fespace Vh(Th,P1);

- macro Grad(u) [dx(u), dy(u), dz(u)] //

- Vh u,v;

- problem Poisson(u,v) =

- int3d(Th)(Grad(u)’*Grad(v))-int3d(Th)(f*v)

- -int2d(Th,LN)(g*v)

- +on(LD,u=0);

- Poisson;

- plot(u,wait=1);

- macro GammaL(u,v,w) [dx(u),dy(v),dz(w),(dy(u)+dx(v)),

- (dz(u)+dx(w)),(dz(v)+dy(w))] //

- macro GammaNL(u1,v1,w1,u2,v2,w2)

- [(dx(u1)*dx(u2)+dx(v1)*dx(v2)+dx(w1)*dx(w2))*0.5,

- (dy(u1)*dy(u2)+dy(v1)*dy(v2)+dy(w1)*dy(w2))*0.5,

- (dz(u1)*dz(u2)+dz(v1)*dz(v2)+dz(w1)*dz(w2))*0.5,

- (dy(u1)*dx(u2)+dx(u1)*dy(u2)+dy(v1)*dx(v2)

- +dx(v1)*dy(v2)+dy(w1)*dx(w2)+dx(w1)*dy(w2))*0.5,

- (dz(u1)*dx(u2)+dx(u1)*dz(u2)+dz(v1)*dx(v2)

- +dx(v1)*dz(v2)+dz(w1)*dx(w2)+dx(w1)*dz(w2))*0.5,

- (dz(u1)*dy(u2)+dy(u1)*dz(u2)+dz(v1)*dy(v2)

- +dy(v1)*dz(v2)+dz(w1)*dy(w2)+dy(w1)*dz(w2))*0.5] //

- macro Gamma(u,v,w) (GammaL(u,v,w)+GammaNL(u,v,w,u,v,w)) //

- macro dGammaNL(u,v,w,uu,vv,ww) (2.0*GammaNL(u,v,w,uu,vv,ww)) //

- macro dGamma(u,v,w,uu,vv,ww) (GammaL(uu,vv,ww)+dGammaNL(u,v,w,uu,vv,ww)) //

- real E = 1.e5; nu = 0.;

- real lambda = E*nu/(1.0+nu)/(1.0-2.0*nu); mu = E/2.0/(1.0+nu);

- func D = [

- [ (lambda+2.0*mu), lambda, lambda,0.0,0.0,0.0 ],

- [ lambda,(lambda+2.0*mu), lambda,0.0,0.0,0.0 ],

- [ lambda, lambda,(lambda+2.0*mu),0.0,0.0,0.0 ],

- [ 0.0,0.0,0.0,mu,0.0,0.0 ],

- [ 0.0,0.0,0.0,0.0,mu,0.0 ],

- [ 0.0,0.0,0.0,0.0,0.0,mu ]

- ];

- fespace Vh(Th3D,[P2,P2,P2]);

- Vh[int] [u,v,w](Norder+1);

- varf PbTg ([u1,v1,w1],[uu,vv,ww]) =

- int3d(Th3D) ( (dGamma(u[0],v[0],w[0],uu,vv,ww))’*

- (D*(GammaL(u1,v1,w1)+2*GammaNL(u[0],v[0],w[0],u1,v1,w1)))

- +(dGammaNL(u1,v1,w1,uu,vv,ww))’*(D*(GammaL(u[0],v[0],w[0])

- +GammaNL(u[0],v[0],w[0],u[0],v[0],w[0]))) )

- +on(lencasmid,u1=0.,v1=0.,w1=0.);

- varf PbF ([u1,v1,w1],[uu,vv,ww]) = int2d(Th3D,lrigthmid) (Pa*ww)

- +on(lencasmid,u1=0.,v1=0.,w1=0.);

- matrix Kt = PbTg(Vh,Vh,solver=sparsesolver);

- Vh [Fu,Fv,Fw];

- Fu[] = PbF(0,Vh);

- Vh [u1hat,v1hat,w1hat];

- u1hat[] = Kt^-1*Fu[];

- fespace QFh6(ThL3D,

- [FEQF53d,FEQF53d,FEQF53d,FEQF53d,FEQF53d,FEQF53d]);

- QFh6[int] [Sxx,Syy,Szz,deuxSxy,deuxSxz,deuxSyz](Norder+1);

- QFh6[Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz](Norder+1);

- [Sxx[1],Syy[1],Szz[1],deuxSxy[1],deuxSxz[1],deuxSyz[1]] =

- DL*(GammaL(u[1],v[1],w[1])+2*GammaNL(u[0],v[0],w[0],u[1],v[1],w[1]));

- [Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz] =

- DL*(GammaNL(u[1],v[1],w[1],u[1],v[1],w[1]));

- varf PbFnl2 ([u1,v1,w1],[uuu,vvv,www]) = - int3d(Th3D) (

- (dGammaNL(u[1],v[1],w[1],uuu,vvv,www))’*

- ([Sxx[1],Syy[1],Szz[1],deuxSxy[1],deuxSxz[1],deuxSyz[1]])

- + (dGamma(u[0],v[0],w[0],uuu,vvv,www))’*

- ([Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz]) )

- + on(lencasmid,u1=0.,v1=0.,w1=0.);

- Fnlu[]=PbFnl2(0,Vh);

- real Norm1 = sqrt(int3d(Th3D) (u[1]’*u[1]+v[1]’*v[1]+w[1]’*w[1]));

- real NormNo = sqrt(int3d(Th3D) (u[Norder]’*u[Norder]+

- v[Norder]’*v[Norder]+

- w[Norder]’*w[Norder]));

- amax = (delta*Norm1/NormNo)^(1.0/(Norder-1.0));

6. Numerical Results

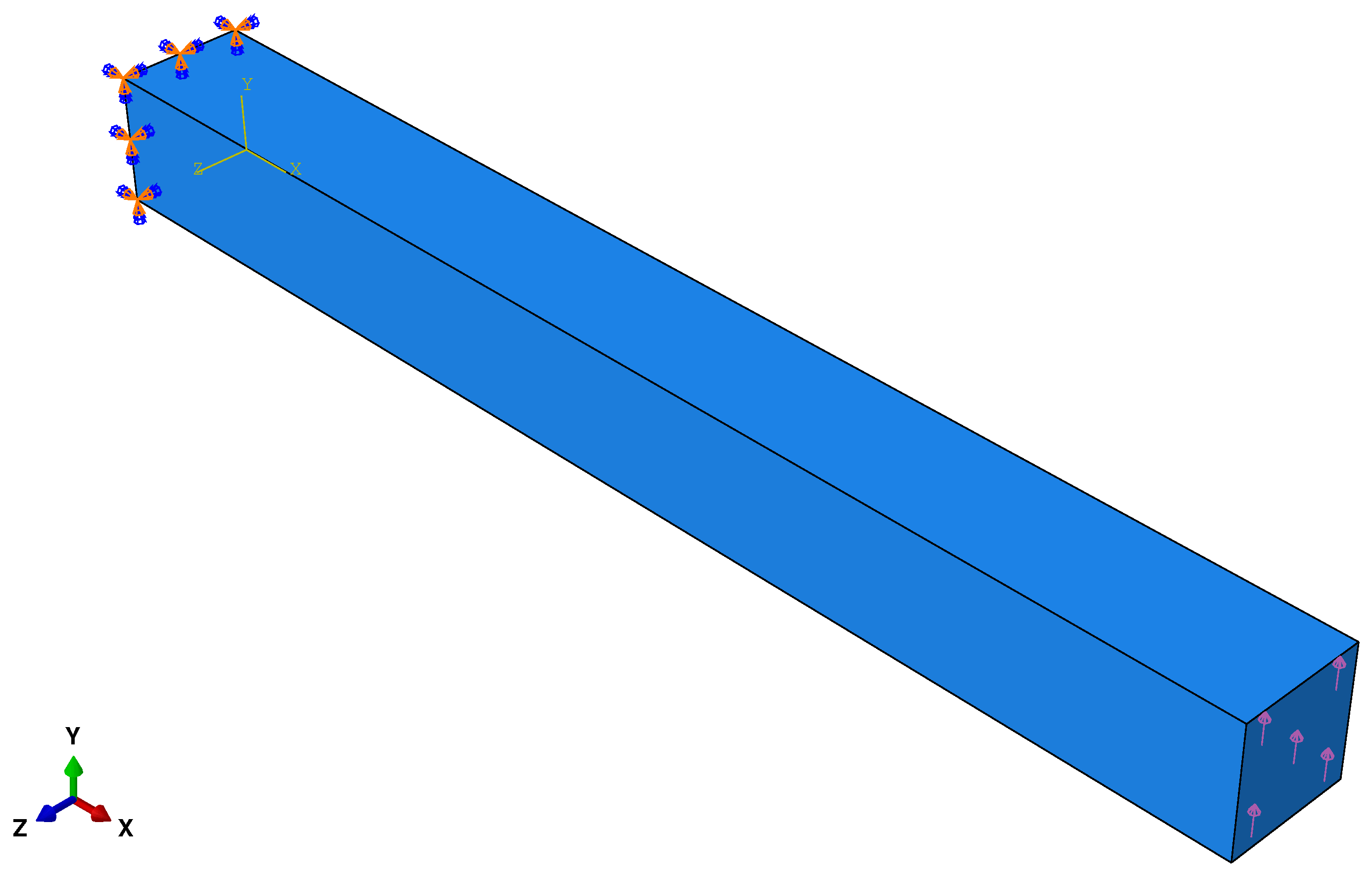

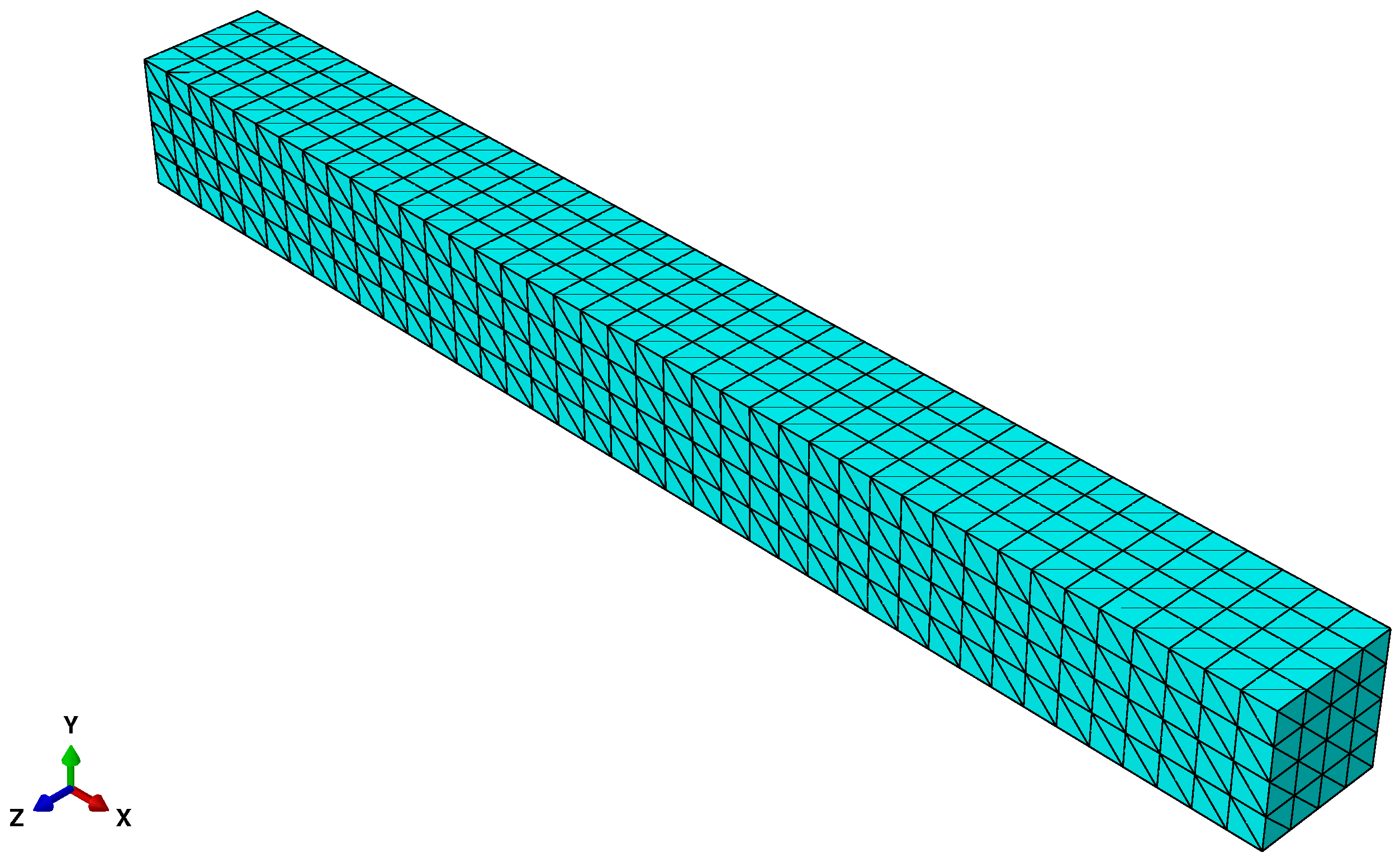

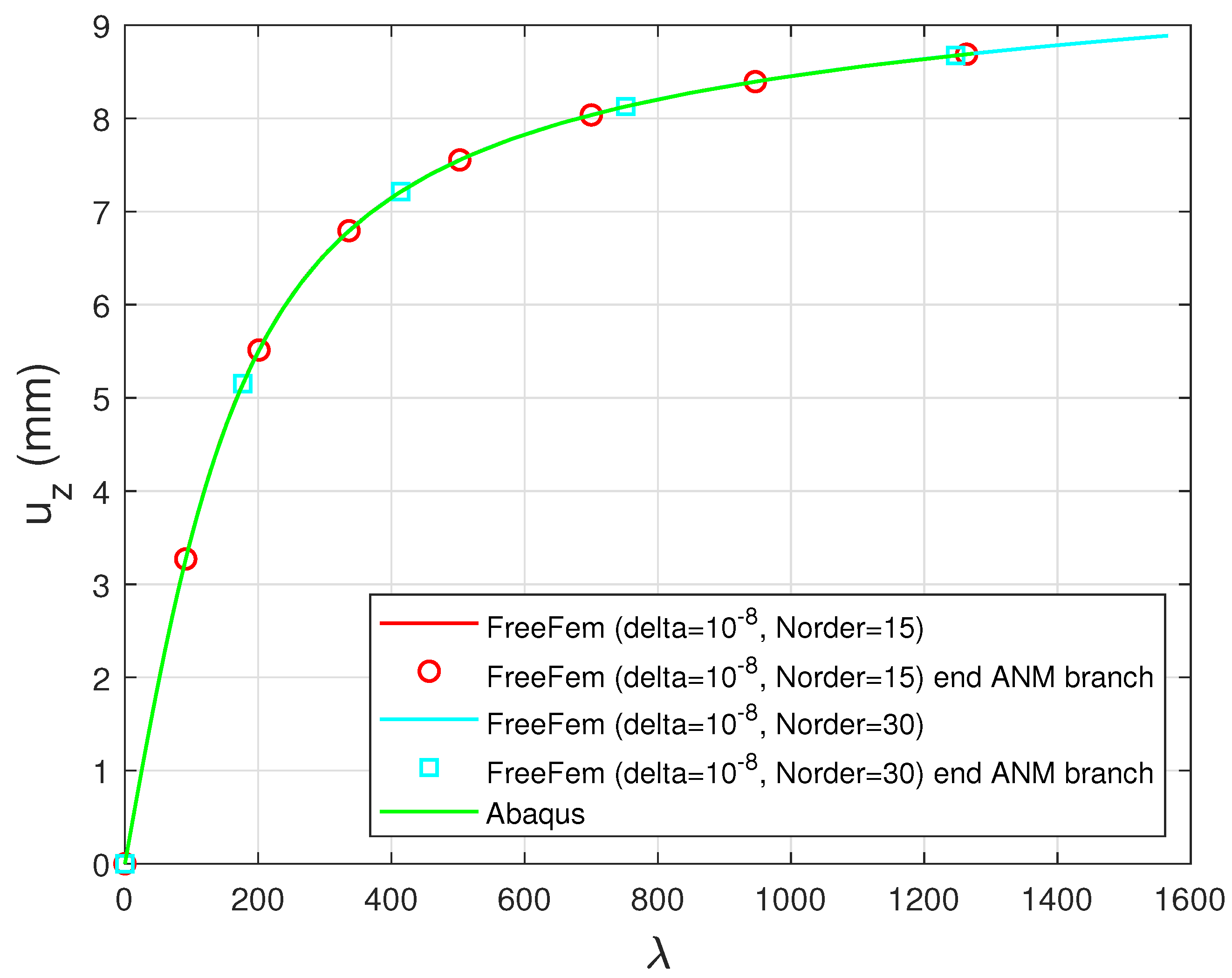

6.1. Clamped Beam Subjected to a Conservative Vertical Surface Traction

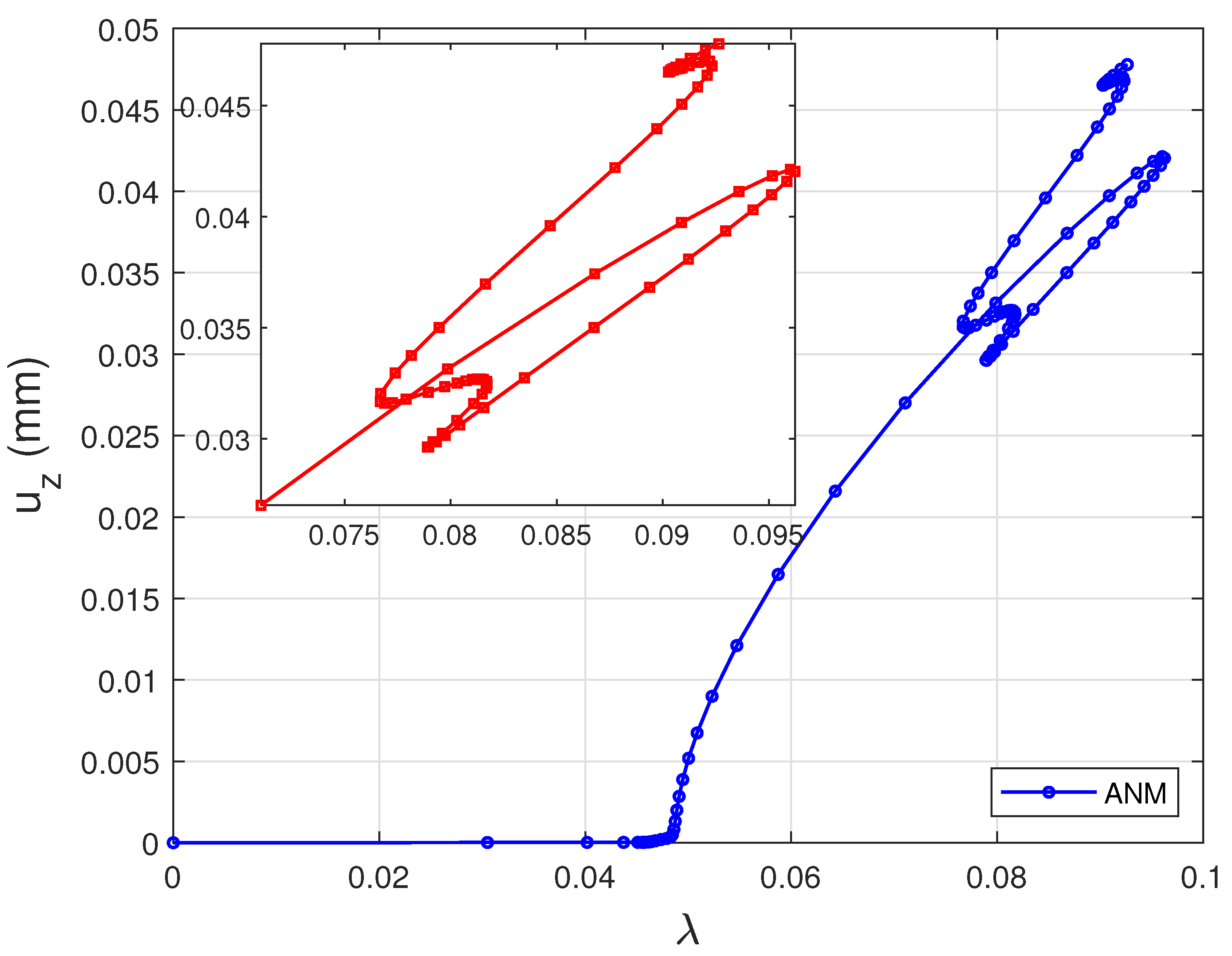

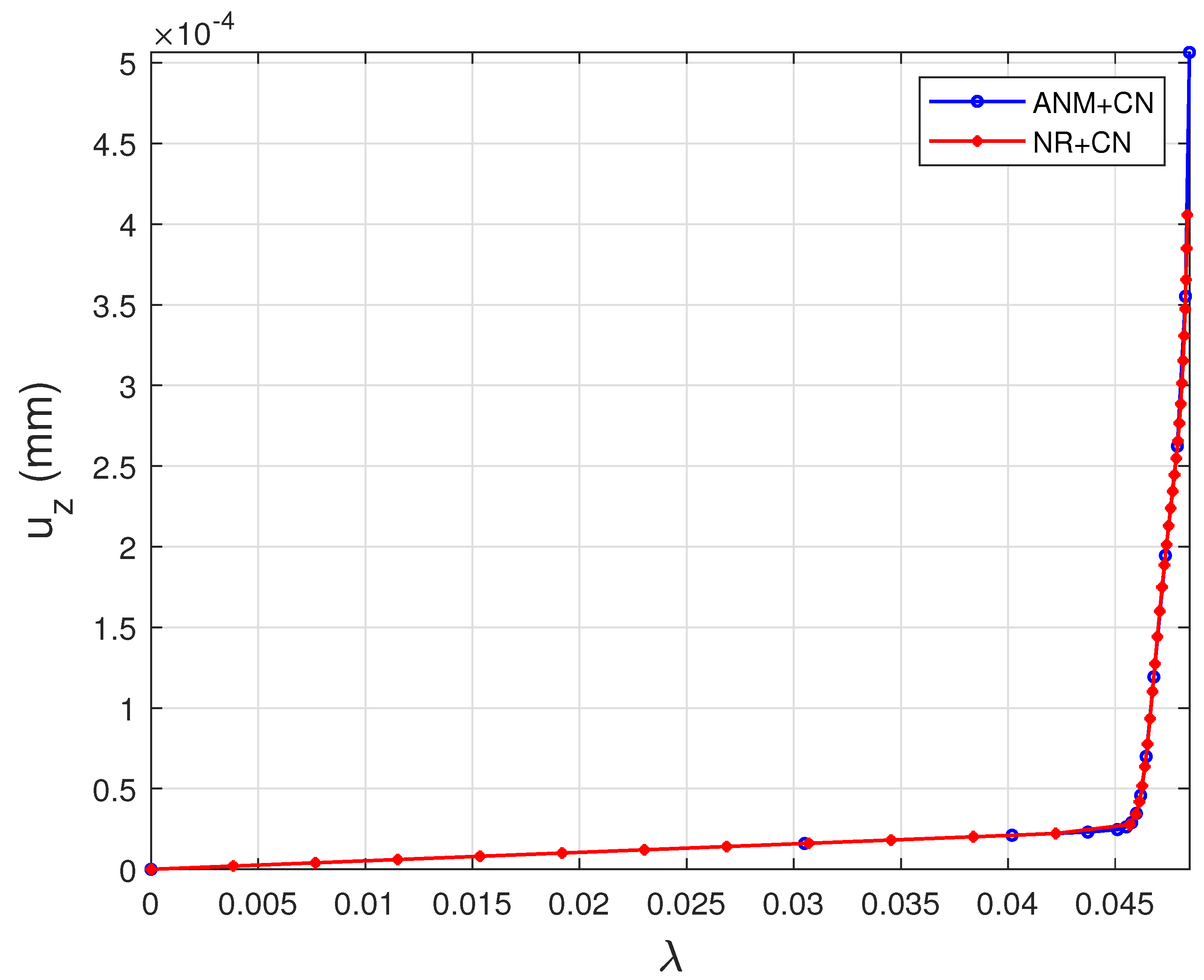

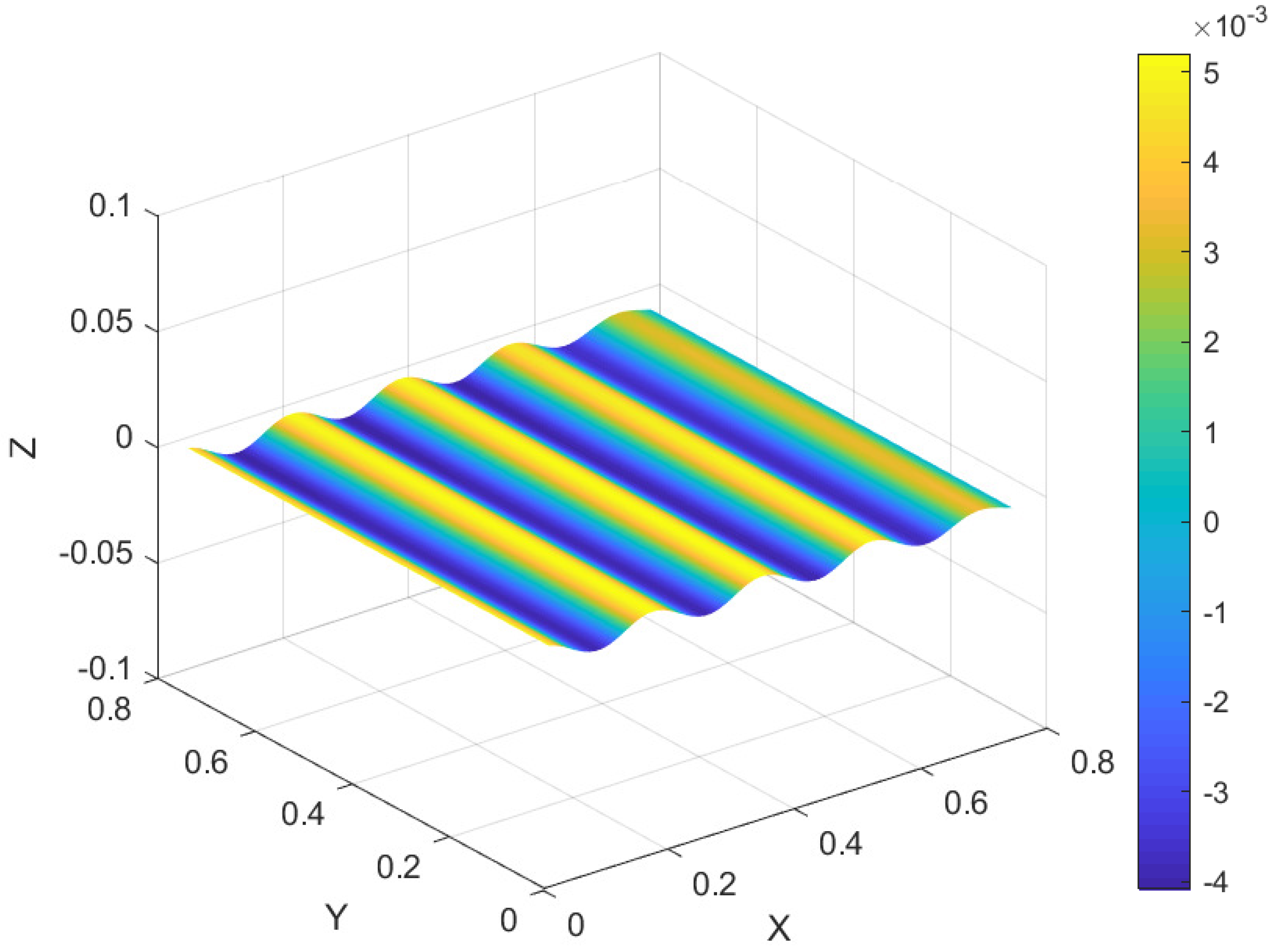

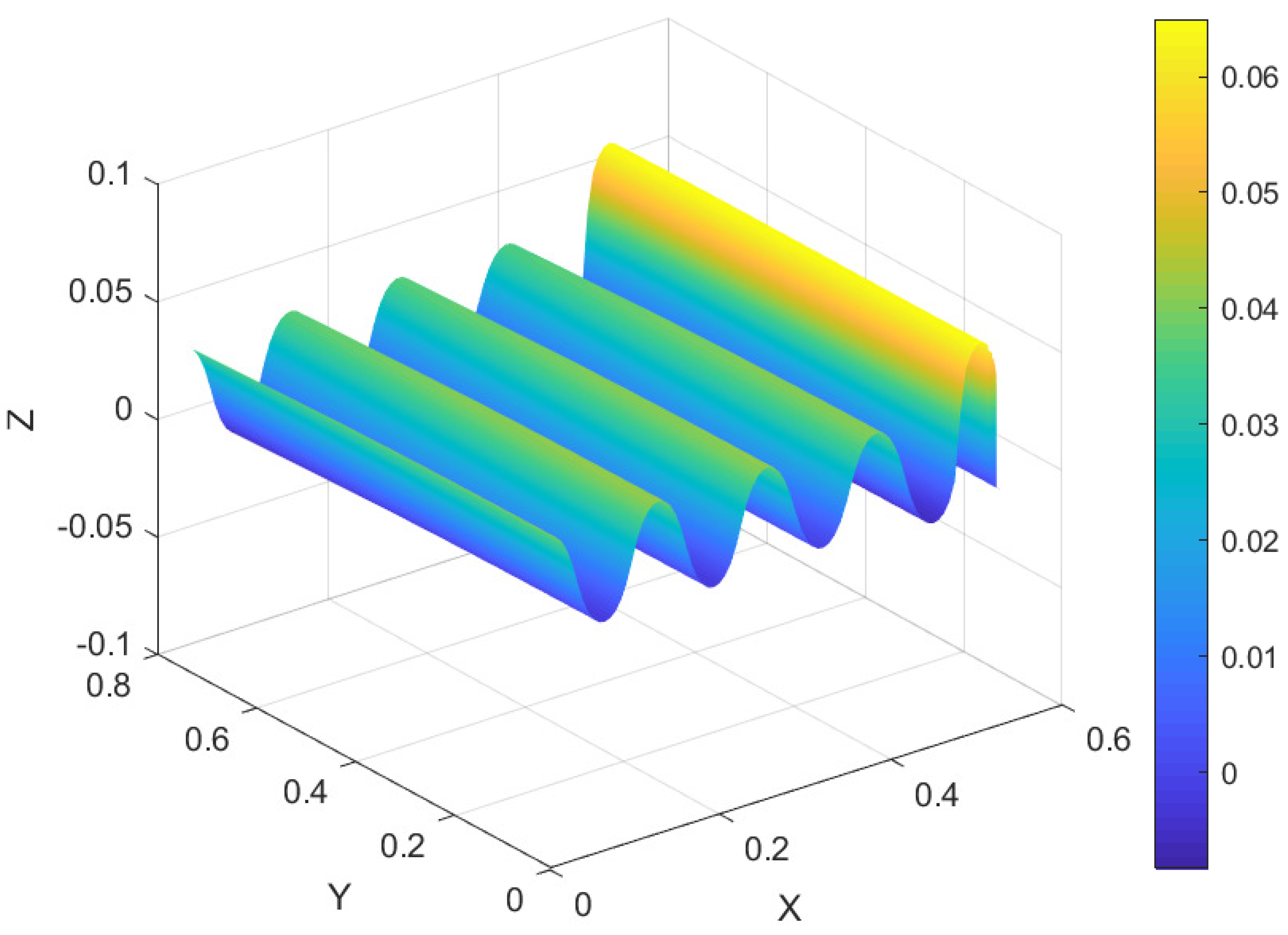

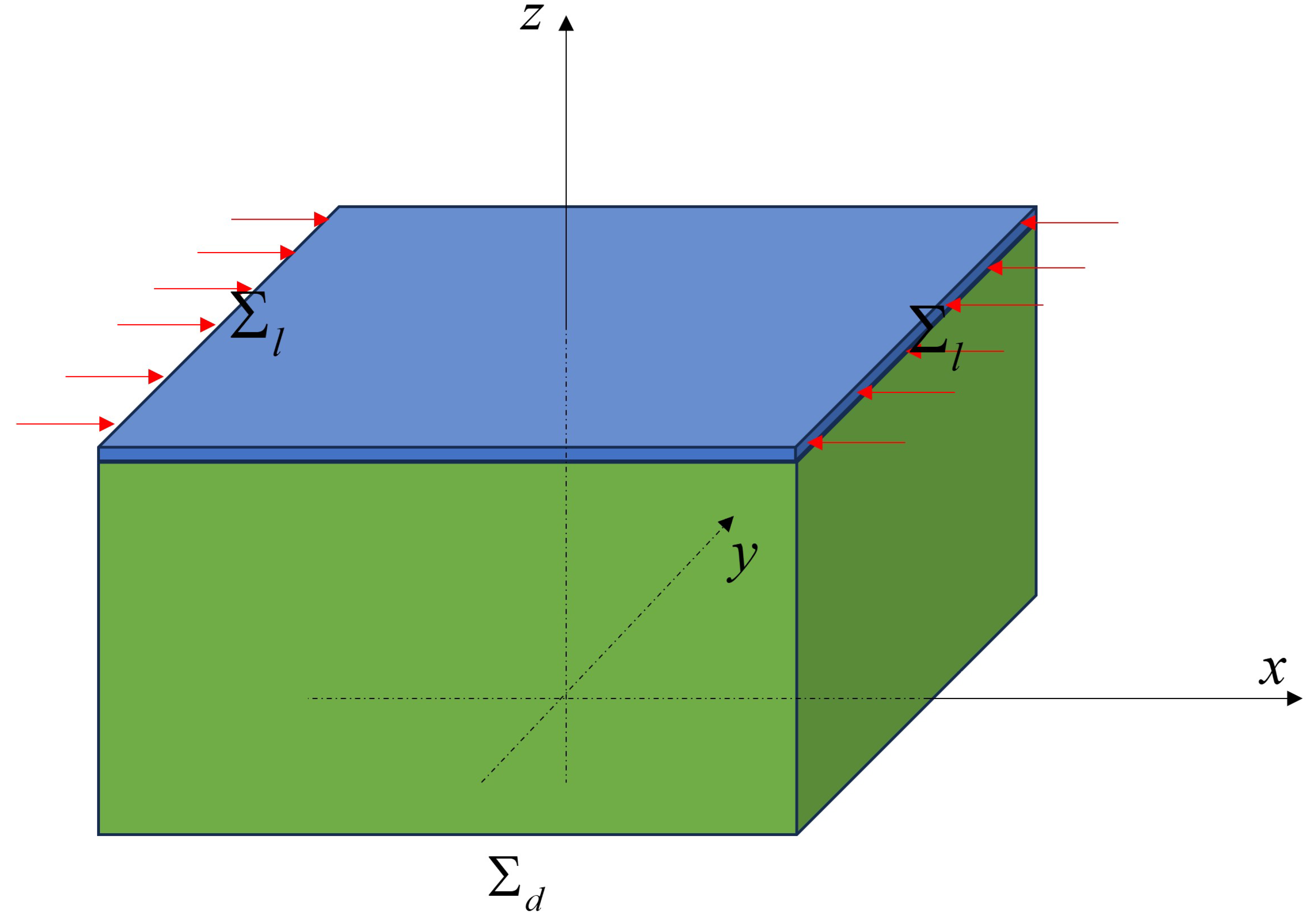

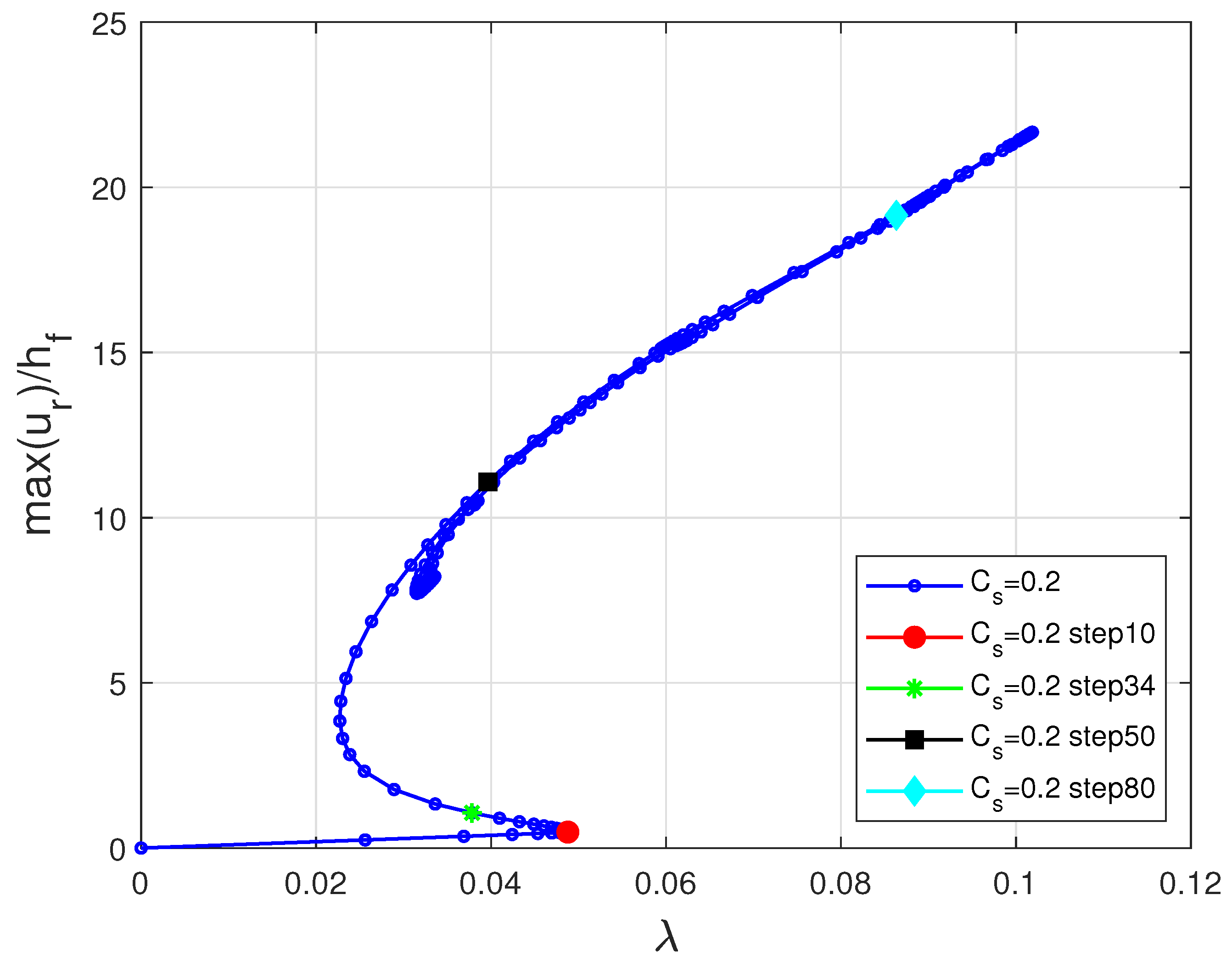

6.2. Film-Substrate Systems Under Uniaxial Compression

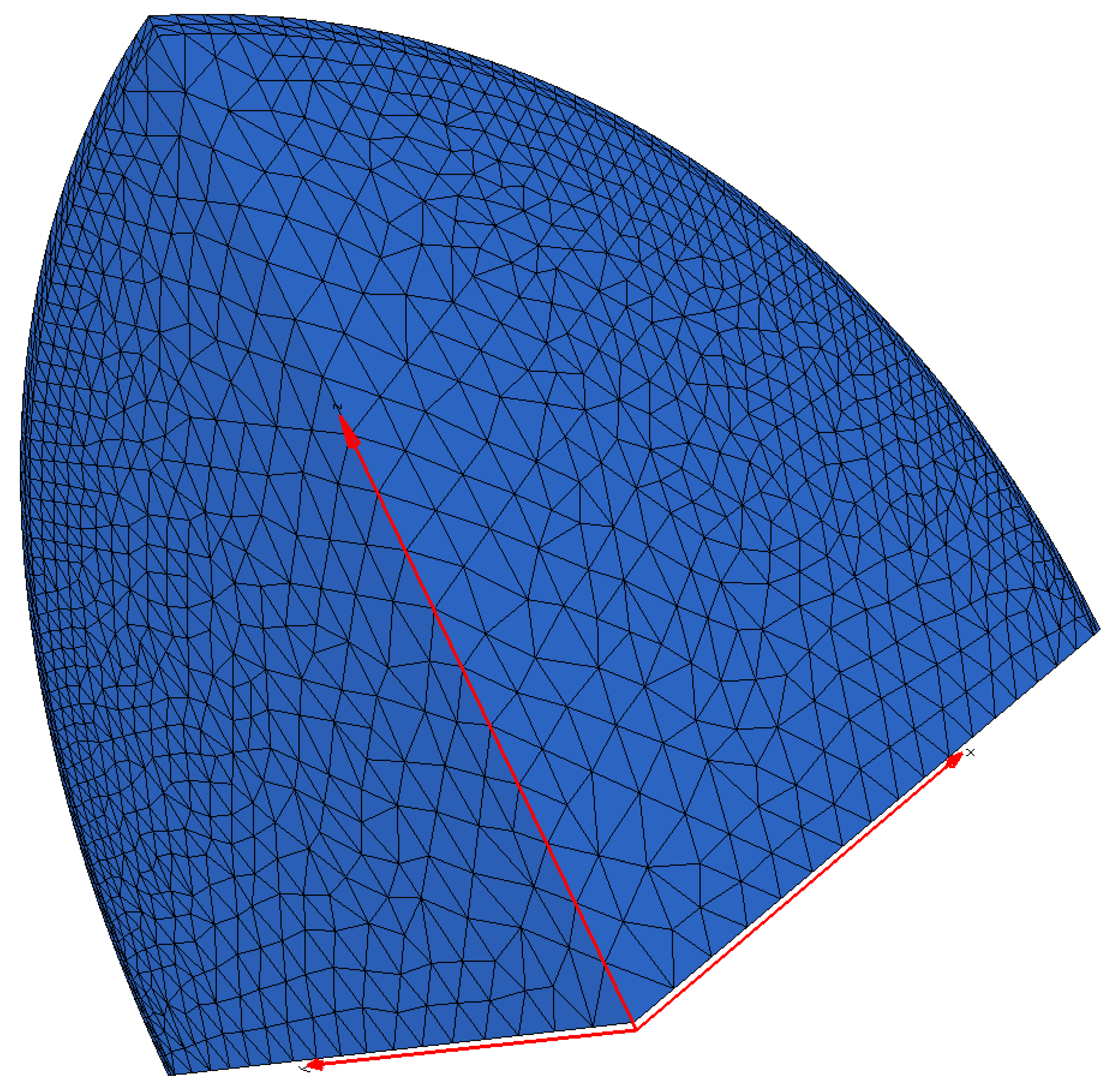

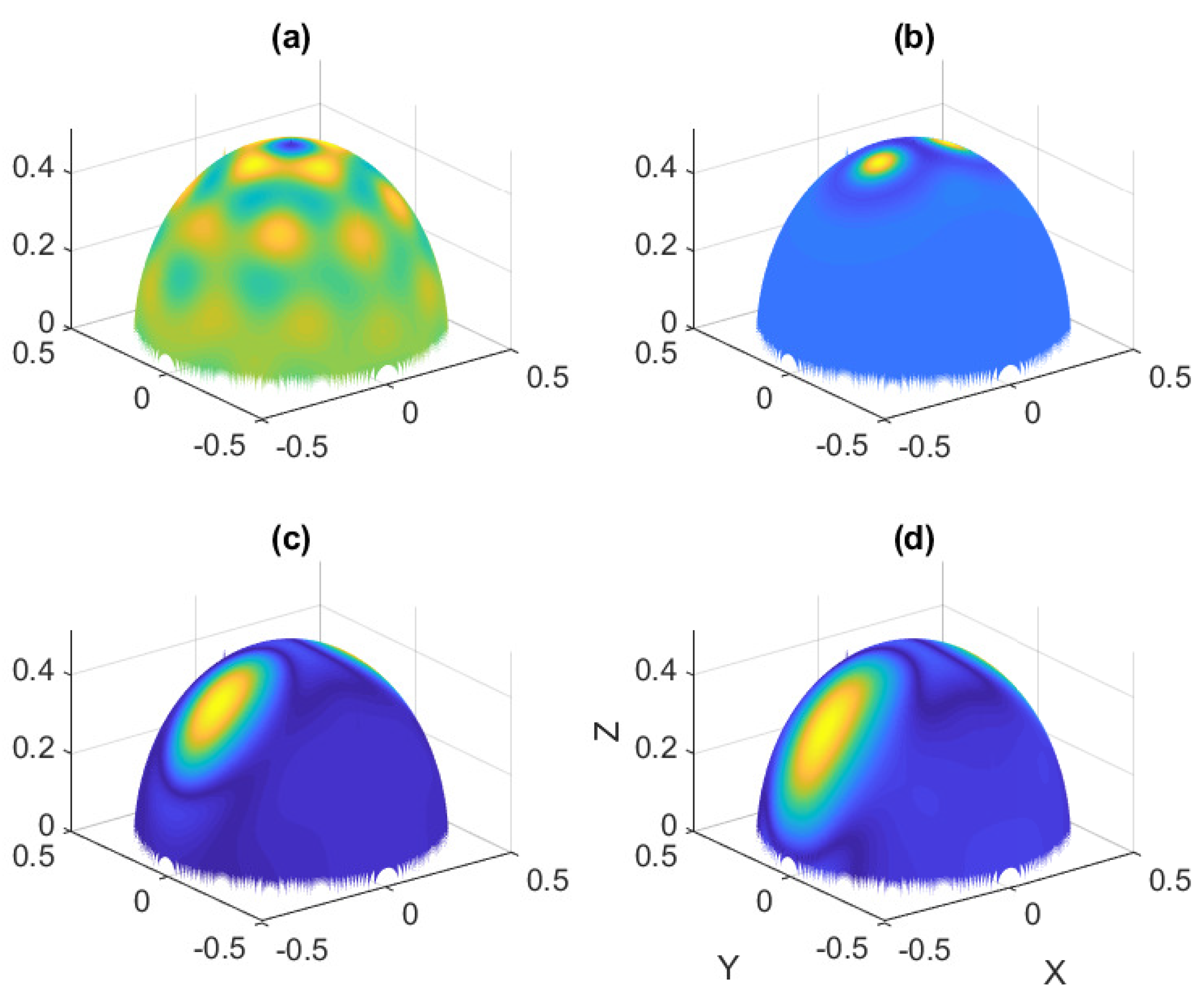

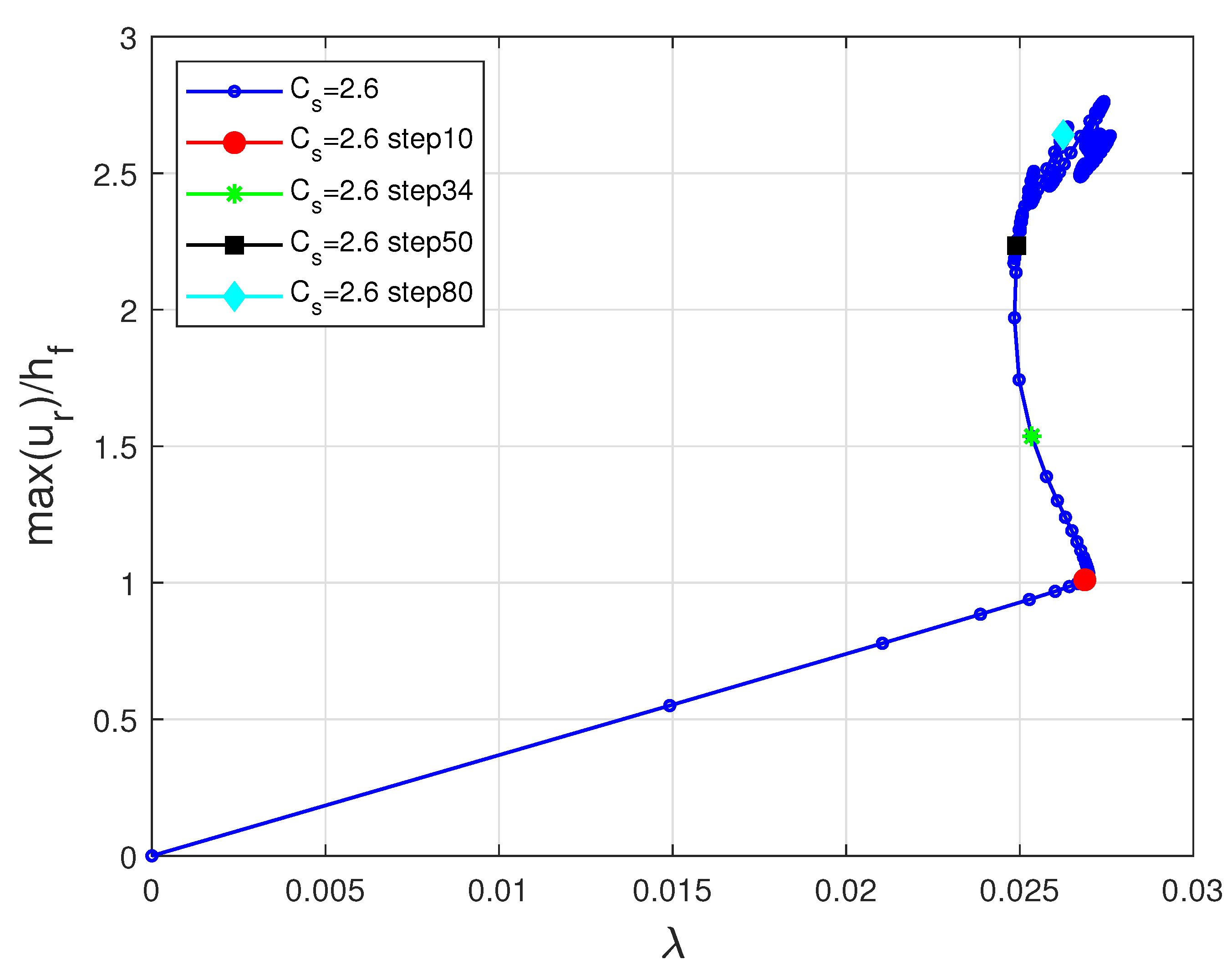

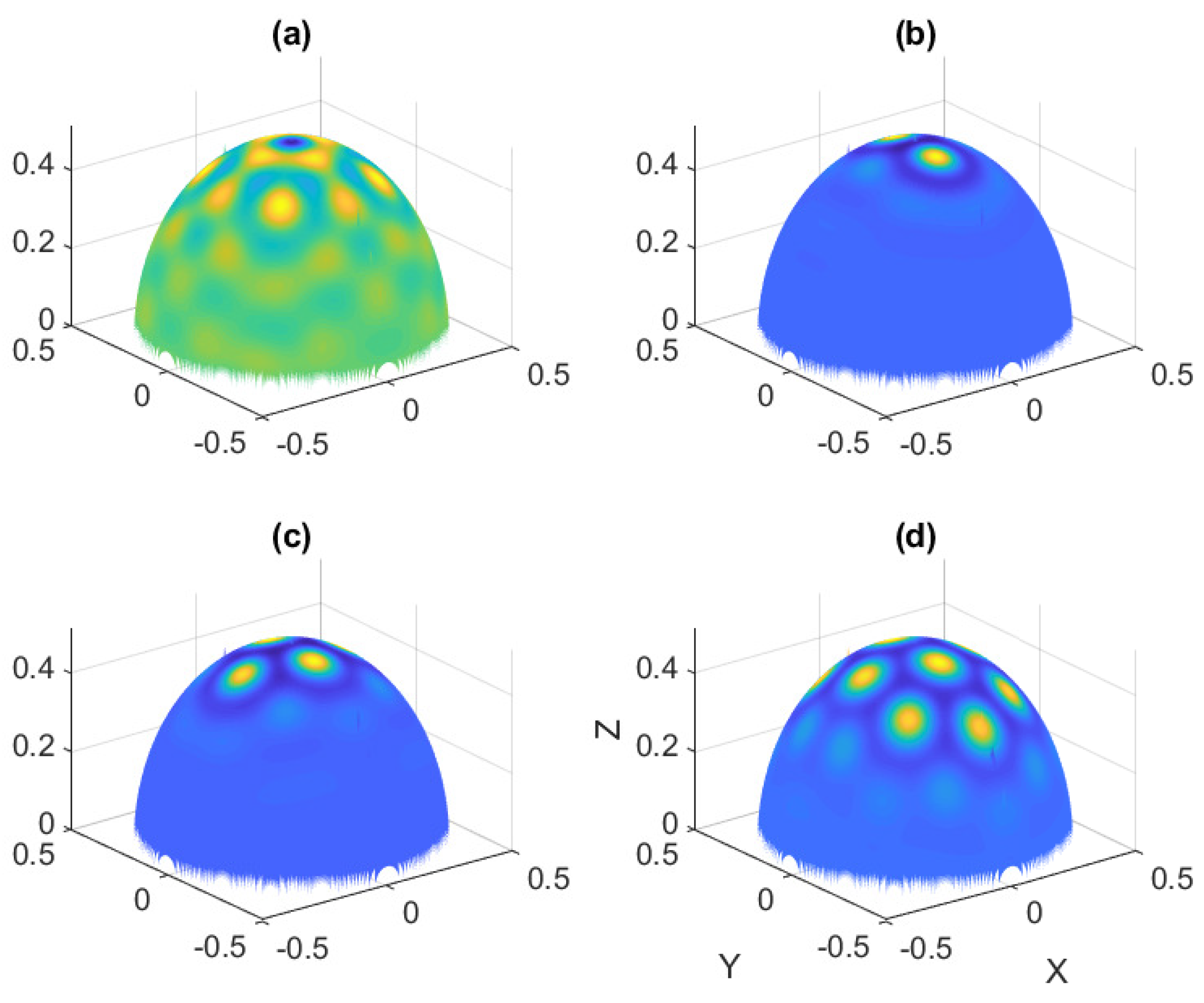

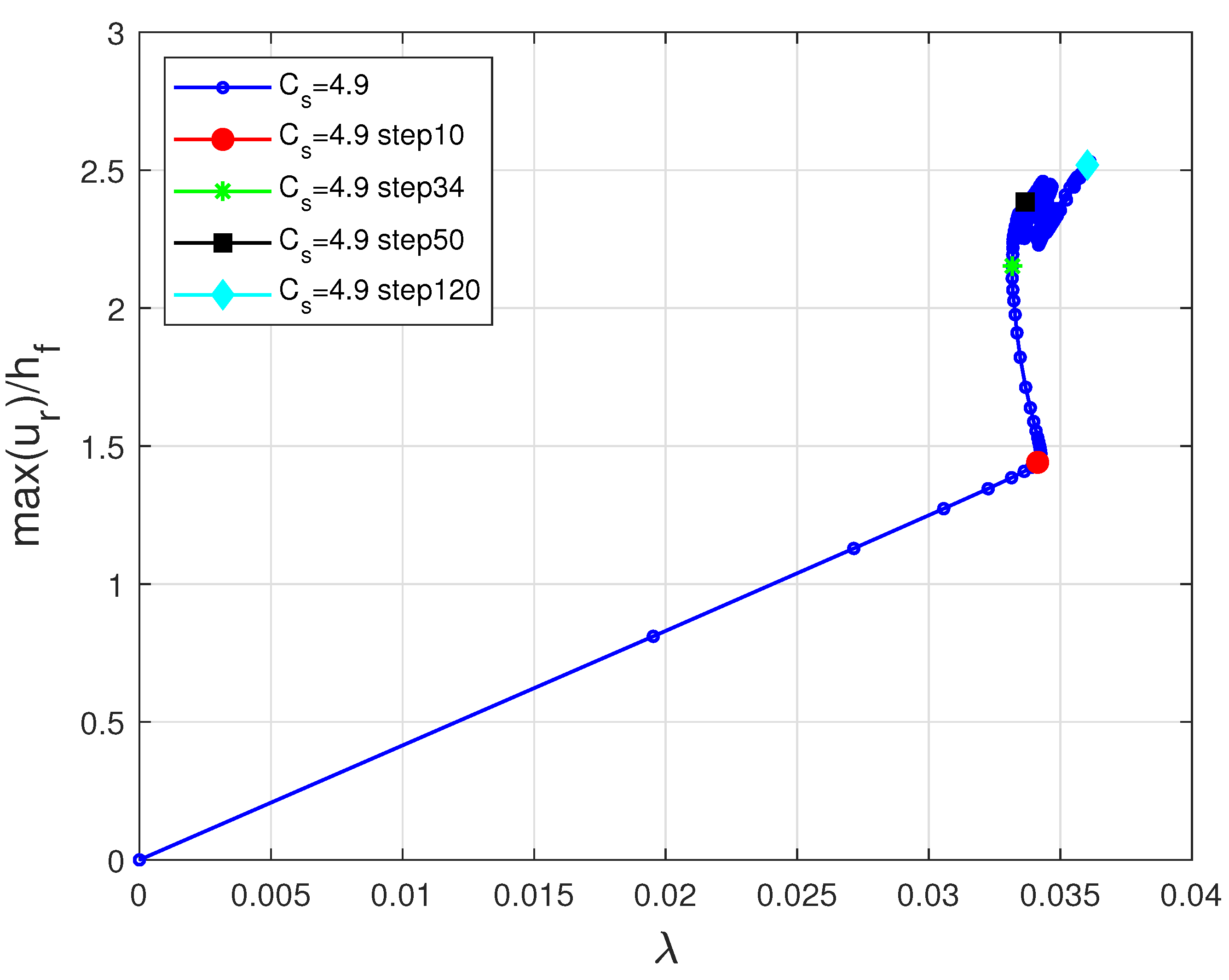

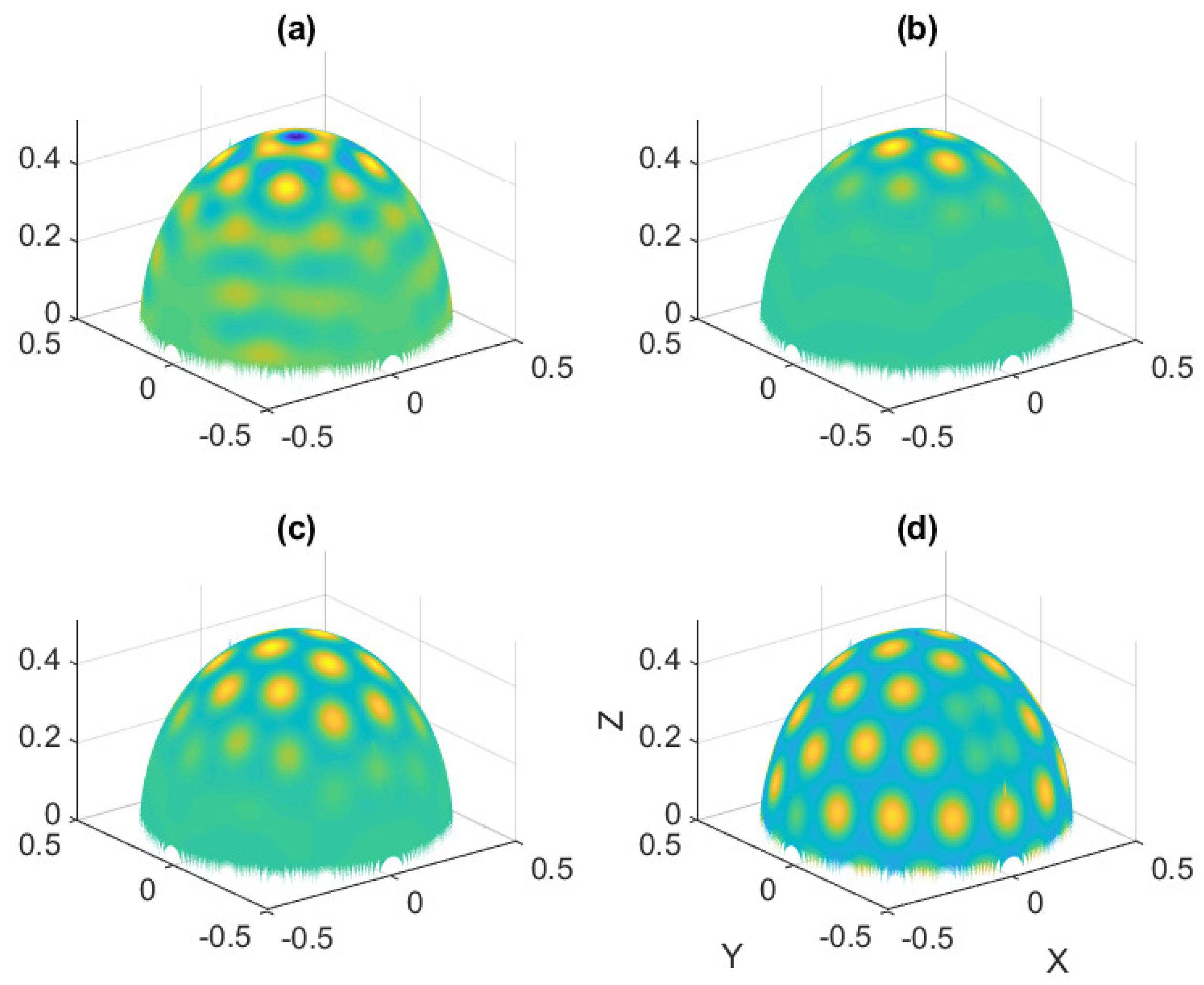

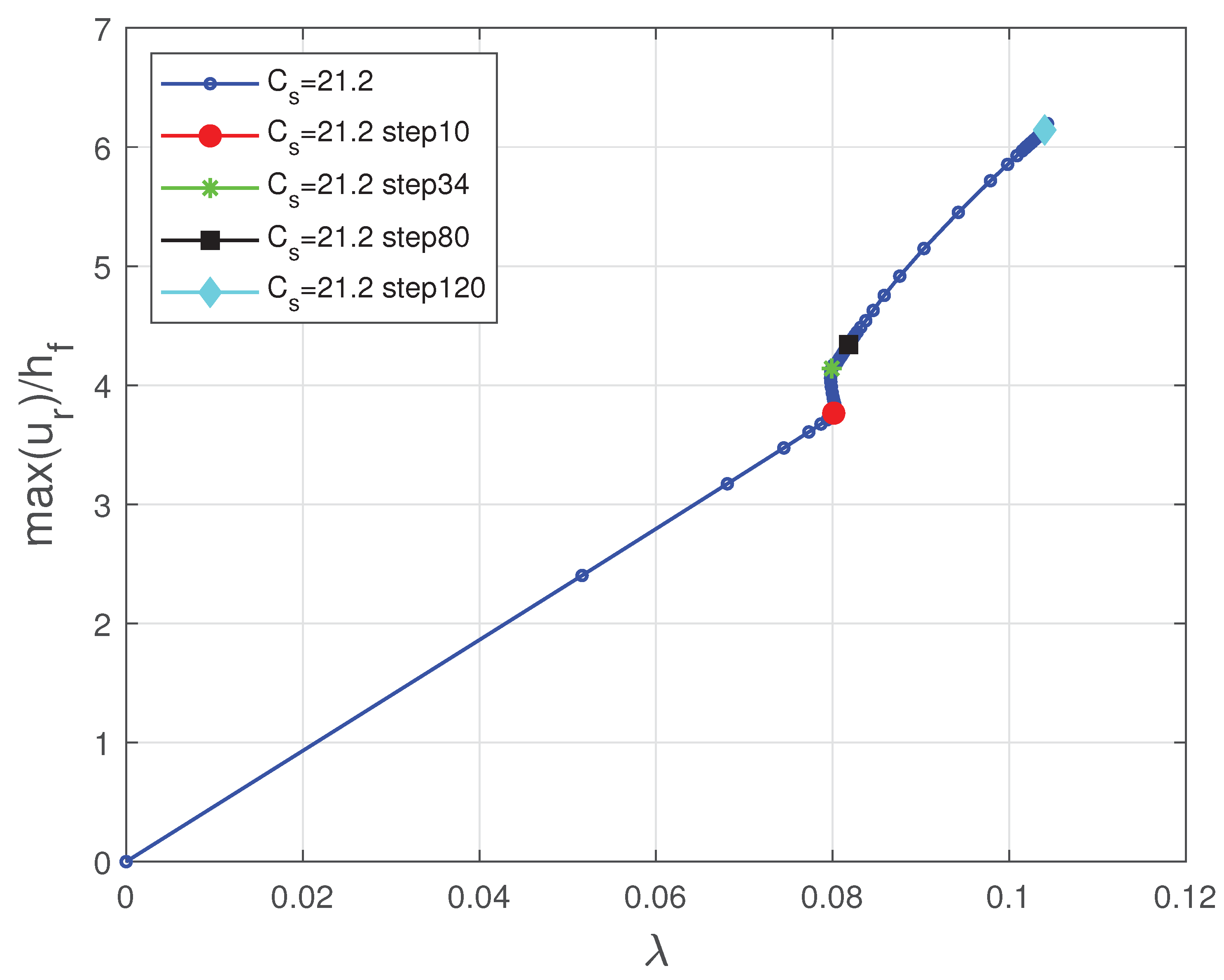

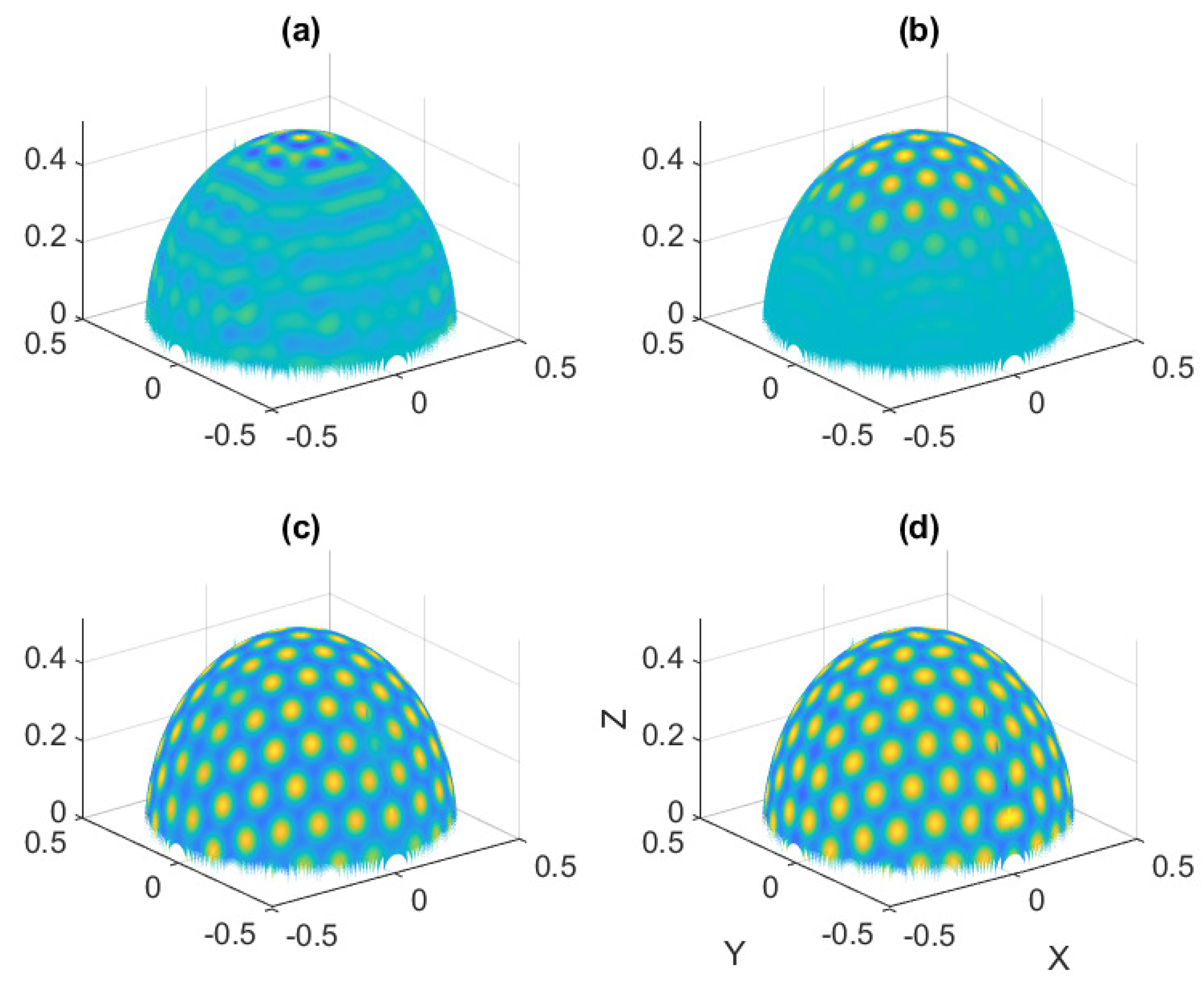

6.3. Spherical Film-Substrate Under Thermal Loading

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. FreeFEM++ Implementation of ANM When the ANM Order Is Greater than 2

- unl[] = Kt^-1*Fnlu[];

- lambda[p] = -lambda[1]*(unl[]’*u[1][]);

- u[p][] = lambda[p]/lambda[1]*u[1][]+unl[];

- [Sxx[p],Syy[p],Szz[p],deuxSxy[p],deuxSxz[p],deuxSyz[p]] =

- DL*(GammaL(u[p],v[p],w[p])+

- 2*GammaNL(u[0],v[0],w[0],u[p],v[p],w[p]))

- +[Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz];

- [Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz] =

- [0.,0.,0.,0.,0.,0.];

- for (int ir=1;ir<(p+1);ir++)

- {

- [Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz] =

- [Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz]

- + GammaNL(u[p+1-ir],v[p+1-ir],w[p+1-ir],u[ir],v[ir],w[ir]);

- }

- [Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz] = D*

- [Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz];

- Vh [Fnlutmp,Fnlvtmp,Fnlwtmp];

- [Fnlu,Fnlv,Fnlw] = [0.,0.,0.];

- [Fnlutmp,Fnlvtmp,Fnlwtmp] = [0.,0.,0.];

- for (int ir=1;ir<(p+1);ir++)

- {

- varf PbFnla ([utmp,vtmp,wtmp],[uuu,vvv,www]) = - int3d(Th3D)

- ( (dGammaNL(u[p+1-ir],v[p+1-ir],w[p+1-ir],uuu,vvv,www))’*

- ([Sxx[ir],Syy[ir],Szz[ir],deuxSxy[ir],deuxSxz[ir],deuxSyz[ir]

- ))

- + on(lencasmid,utmp=0.,vtmp=0.,wtmp=0.);

- Fnlutmp[] = PbFnla(0,Vh);

- Fnlu[] = Fnlu[] + Fnlutmp[];

- }

- Vh [Fnlutmp,Fnlvtmp,Fnlwtmp];

- Fnlutmp[] = 0.0;

- varf PbFnlc ([utmp,vtmp,wtmp],[uuu,vvv,www]) =

- - int3d(Th3D) ( (dGamma(u[0],v[0],w[0],uuu,vvv,www))’*

- ([Snlxx,Snlyy,Snlzz,deuxSnlxy,deuxSnlxz,deuxSnlyz]) )

- + on(lencasmid,utmp=0.,vtmp=0.,wtmp=0.);

- [Fnlutmp,Fnlvtmp,Fnlwtmp] = [0.,0.,0.];

- Fnlutmp[] = PbFnlc(0,Vh);

- Fnlu[] = Fnlu[] + Fnlutmp[];

Appendix B. Newton-Raphson Continuation and Newton-Riks Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm A1 Algorithm Newton-Raphson Prediction |

|

| Algorithm A2 Algorithm Newton-Riks correcions |

|

References

- Wong, W.; Pellegrino, S. Wrinkled membranes III: numerical simulations. Journal of Mechanics of Materials and Structures 2006, 1, 63–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hutchinson, J.W. Herringbone buckling patterns of compressed thin films on compliant substrates. Journal of Applied Mechanics 2004, 71, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhao, S.; Conghua, L.; Potier-Ferry, M. Pattern selection in core-shell spheres. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids (2020) 103892, 137. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Potier-Ferry, M.; Abed-Meraim, F. Buckling and wrinkling of thin membranes by using a numerical solver based on multivariate Taylor series. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2021, 230, 111165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Rio, G.; Cadou, J.M.; Troufflard, J. Numerical study of dynamic relaxation with kinetic damping applied to inflatable fabric structures with extensions for 3D solid element and non-linear behavior. Thin-Walled Structures 2011, 49, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Bertoldi, K.; Steigmann, D.J. Spatial resolution of wrinkle patterns in thin elastic sheets at finite strain. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2014, 62, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.T.; Walker, A.C. The non-linear perturbation analysis of discrete structural systems. International Journal of Solids and Structures 1968, 4, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochelin, B. A path following technique via an asymptotic-numerical method. Computers and Structures 1994, 53(5), 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochelin, B.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. The asymptotic numerical method : an efficient technique for non linear structural mechanics. Revue Européenne des Eléments Finis 1994, 3, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochelin, B.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. Asymptotic-numerical methods and Padé approximants for non linear elastic structure. International journal of Numerical Methods in Engineering 1994, 37, 1187–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azrar, L.; Cochelin, B.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. An asymptotic-numerical method to compute the postbuckling behaviour of elastic plates and shells. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 1993, 36, 1251–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, A.; Cochelin, B.; Potier-Ferry, M. Résolution des équations de Navier-Stokes et Détection des bifurcations stationnaires par une Méthode Asymptotique-Numérique. Revue Européenne des éléments Finis 1996, 5, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhage-Hussein, A.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. An asymptotic numerical algorithm for frictionless contact problems. Revue Européenne des éléments Finis 1998, 7, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrouni, H.; Cochelin, B.; Potier-Ferry, M. Computing finite rotations of shells by an asymptotic-numerical method. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 1999, 175, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadou, J.M.; Potier-Ferry, M.; Cochelin, B. A numerical method for the computation of bifurcation points in fluid mechanics. European Journal of Mechanics - B/Fluids 2006, 25, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggoune, W.; Zahrouni, H.; Potier-Ferry, M. Asymptotic numerical methods for unilateral contact. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2006, 68, 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Nezamabadi, S.; Zahrouni, H.; Yvonnet, J. Multiscale computational homogenization of heterogeneous shells at small strains with extensions to finite displacements and buckling. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2015, 104, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riks, E. An incremental approach to the solution of snapping and buckling problems. International Journal of Solids and Structures 1979, 15, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Arquier, B. R. Arquier, B. Cochelin, C. Manlab, http://manlab.lma.cnrs-mrs.fr/.

- Lejeune, A.; Béchet, F.; Boudaoud, H.; Mathieu, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. Object-oriented design to automate a high order non-linear solver based on asymptotic numerical method. Advances in Engineering Software 2012, 48, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevel, Y.; Allain, T.; Girault, G.; Cadou, J.M. Numerical bifurcation analysis for 3-dimensional sudden expansion fluid dynamic problem. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2018, 87, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, F. New development in FreeFem++. Journal of Numerical Mathematics 2012, 20, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, F.; Ventura, P.; Dufilié, P. Original coupled FEM/BIE numerical model for analyzing infinite periodic surface acoustic wave transducers. Journal of Computational Physics 2013, 246, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, F.; Pironneau, O. An energy stable monolithic Eulerian fluid-structure finite element method. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2017, 85, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Potier-Ferry, M.; Belouettar, S.; Cong, Y. 3D finite element modeling for instabilities in thin films on soft substrates. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2014, 51, 3619–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Koutsawa, Y.; Potier-Ferry, M.; Belouettar, S. Instabilities in thin films on hyperelastic substrates by 3D finite elements. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2015, 69-70, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochelin, B.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. Méthode asymptotique numérique; Hermès-Lavoisier, 2007.

- Potier-Ferry, M. Asymptotic numerical method for hyperelasticity and elastoplasticity: a review. Proceeding of the Royal Society 2024, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourdon, X. Analyse; Ellipse, 2020.

- Berger, M.S. Nonlinearity and functional analysis: lectures on nonlinear problems in mathematical analysis. Academic press, New York 1977, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.S. Method of Lyapunov and Schmidt in the study of non-linear equation and their further development. Russian mathematical surveys 1962, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Mottaqui, H.; Braikat, B.; Damil, N. Discussion about parameterization in the asymptotic numerical method: application to nonlinear elastic shells. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2010, 199, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmam, H.; Cadou, J.M.; Zahrouni, H.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. High-order predictor–corrector algorithms. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2002, 55, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, P.; Potier-Ferry, M.; Zahrouni, H. A secure version of asymptotic numerical method via convergence acceleration. Comptes Rendus Mécaniques 2020, 348, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assidi, M.; Zahrouni, H.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. Regularization and perturbation technique to solve plasticity problems. International Journal of Material Forming 2009, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kihal, C.; Askour, O.; Belaasilia, Y.; Hamdaoui, A.; Braikat, B.; Damil, N.; Potier-Ferry, M. Asymptotic numerical method for finite plasticity. Finite Elements in Analysis and Design 2022, 206, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrouni, H. Méthode Asymptotique Numérique pour les coques en grande rotation. PhD thesis, Université de Lorraine, 1998.

- Bowden, N.; Brittain, S.; Evans, A.G.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Whitesides, G.M. Spontaneous formation of ordered structures in thin films of metals supported on an elastomeric polymer. Nature 1998, 393, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, N.; Huck, W.; Paul, K.; Whitesides, G.M. The control formation of ordered, sinusoidal structures by plasma oxidation of an elastometric polymer. Applied Physics Letters 1999, 75(17), 2557–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, J.; Kim, D.H.; Huang, Y.; Rogers, J.A. Local versus global buckling of thin films on elastometric substrates. Applied Physics Letters, 0231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarter, J.; Stafford, C. Instabilities as a measurement tool for soft materials. Soft Mater 2010, 6(22), 5661–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchter", N.; Ramm, E.; Roehl, D. Three dimensional extension of non-linear shell formulation based on the enhanced assumed strain concept. International Journal for Numeral Methods in Engineering 1994, 37, 2551–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hutchinson, J. Herringbone buckling patterns of compressed thin films on compliant substrates. Journal of Applied Mechanics 2004, 71, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguet, S.; Cochelin, B. On the behaviour of the ANM continuation in the presence of bifurcation. Communication in Numerical Methods in Engineering 2003, 19, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyel, F.; Chaboche, J.L. FE2 multiscale approach for modelling the elastoviscoplastic behaviour of long fibre SiC/Ti composite materials. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2000, 183, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamabadi, S.; Yvonnet, J.; Zahrouni, H.; Potier-Ferry, M. A multilevel computational strategy for microscopic and macroscopic instabilities. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2009, 198, 2099–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pure Newton | 152 | 87 | 53 |

| Full algorithm | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| r | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | 1224 | 4925 | 17660 | ||||

| after | 1584 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).