1. Introduction

Japan’s healthcare system is widely recognized for its universal health coverage, low infant mortality rates, and having among the highest life expectancies globally. These accomplishments have been built over decades of dedicated efforts by healthcare professionals, policymakers, and communities alike. The system’s accessibility and quality have made it a model for many countries seeking to improve public health.

However, Japan currently faces new challenges arising from demographic changes such as rapid population aging and a shrinking workforce, alongside persistent regional disparities in healthcare resource distribution. With the worsening of the national fiscal balance, the sustainability of the current comprehensive social security system is increasingly uncertain, and there is growing pressure to contain the rising costs of healthcare.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Japan has experienced a significant increase in excess mortality and a stagnation in life expectancy [

1,

2,

3] As a result, the pace of population decline may accelerate beyond previous projections. This demographic shift, driven by both depopulation and rapid aging, raises concerns about a potential decline in Japan's international standing and economic strength.

These challenges call for a reexamination of how healthcare services are organized and delivered across the country.

In the context of Japan's declining population density, the Japan Hospital Association emphasizes that the reduction in hospitals and inpatient beds is a natural and inevitable trend. It highlights the need to re-evaluate the healthcare delivery system by categorizing regions into everyday care areas, regional care zones, and wide-area medical zones. Given the projected changes in disease structure and the sharp decline in the healthcare workforce due to demographic shifts, it is increasingly difficult to sustain the current healthcare model. The Association underscores the importance of defining what services to discontinue or downscale and warns that hospitals must strategically prepare for a gradual withdrawal. Clarifying the roles of hospitals and fostering inter-institutional collaboration are viewed as essential steps forward [

4,

5]

This review argues that Japan’s exceptionally high density of hospital beds—particularly in rural areas—contributes to inefficiencies in healthcare delivery and distorts resource allocation, necessitating urgent structural reform. Despite having a relatively low physician-to-population ratio compared to other developed countries, Japan maintains one of the highest hospital bed densities globally. This discrepancy raises critical questions about the relationship between healthcare infrastructure, medical need, utilization, and expenditures.

In this review, we compared Japan’s hospital bed and physician densities with international benchmarks. Next, we analyze the association between bed density and key health indicators across prefectures—such as per capita healthcare expenditure, life expectancy, and healthy life expectancy—using scatter plots to assess whether a higher number of hospital beds translates into better health outcomes.

The case of Yubari City, Hokkaido, is also examined. After declaring financial bankruptcy in 2007 and losing its general hospital, the city did not experience a decline in health indicators, and medical costs showed a downward trend [

6]

.

This example underscores the potential role of primary care physicians and generalists in sustaining population health amid declining infrastructure. Finally, the article offers policy recommendations to enhance the sustainability, equity, and quality of Japan’s healthcare system in the face of demographic and economic pressures.

2. Japan’s Healthcare Context in International Perspective

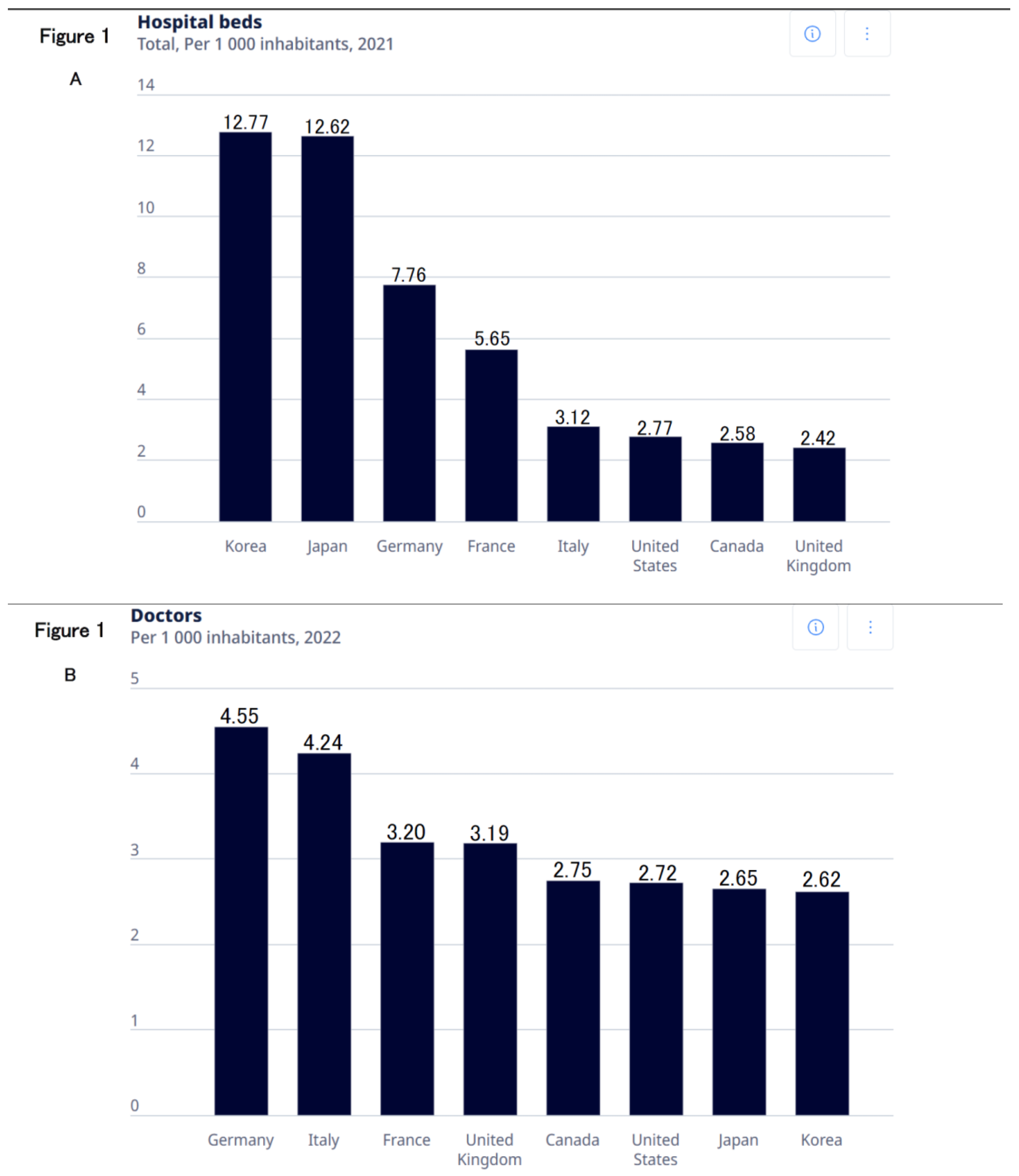

According to OECD data from 2021, Japan had approximately 12.62 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants. This is the

second highest, closely following Korea. This figure is nearly double that of countries like Germany (7.76 beds per 1,000) or France (5.65 beds per 1,000) [

7] (

Figure 1A) In stark contrast, Japan’s physician density stands at around 2.65 physicians per 1,000 people, which is relatively low compared to Germany (4.55) or Italy (4.24) [

8] (

Figure 1B)

This combination of high hospital bed availability alongside a comparatively low physician density is quite unusual among developed countries. Many OECD members employ centralized healthcare planning mechanisms, regulating the establishment of new hospitals and the allocation of beds based on regional population health needs and projected demand. This ensures that healthcare infrastructure is matched closely to the epidemiological and demographic profiles of each area.

Japan’s system differs in that it permits a relatively free market entry for new medical facilities. Licensed physicians can establish hospitals or clinics by fulfilling certain minimum requirements. Until the 1980s, supply regulation through hospital bed controls was not implemented. This policy was designed in the postwar era to rapidly increase access to healthcare across the country. While this approach has succeeded in improving geographic access to medical services, it also introduces challenges in coordinating resources effectively and controlling healthcare spending. Understanding the implications of this unique balance between market forces and regulation is essential for addressing emerging inefficiencies.

3. Structural Factors Influencing Hospital Bed Supply and Utilization

Japan’s healthcare infrastructure is heavily shaped by its historical context. After World War II, the priority was to

expand access rapidly, resulting in a free-entry system where more than 80% of hospitals are privately owned and operated, often by individual physicians or small family-run organizations. This decentralized ownership structure contributed to the proliferation of hospitals, especially in areas where demand appeared stable or growing.

Compounding this is the national health insurance reimbursement scheme, which primarily relies on a fee-for-service payment model. Under this system, providers are paid for each diagnostic test, procedure, and inpatient day. Such volume-based remuneration creates financial incentives for hospitals to maximize admissions, prolong lengths of stay, and maintain high occupancy rates.

Unlike other systems that use global budgeting, capitation, or bundled payments to contain volume-driven care, Japan currently lacks stringent mechanisms to cap hospital bed supply or the overall volume of reimbursed services. Consequently, hospital operators may regard maintaining a large bed capacity as a business imperative rather than merely a clinical necessity. These structural incentives may, in some contexts, contribute to patterns of supply-sensitive utilization, where hospitalization rates reflect not only medical necessity but also the availability of beds and institutional norms.

4. Regional Variations and Economic Influences

An earlier analysis using 1992 national health insurance data found that Fukuoka Prefecture had 43% higher inpatient expenditure per capita compared to the national average, primarily due to high rates of long-term hospitalization related to stroke. The study also showed that inpatient costs correlated more with bed supply than with actual medical need, highlighting the importance of structural factors in explaining regional variation [

9]

An examination of data across Japan’s 47 prefectures reveals substantial variation in hospital bed density and

medical expenditures. All public statistical data used in this study are from the year 2022.

Table 1 provides the source URLs for each dataset:

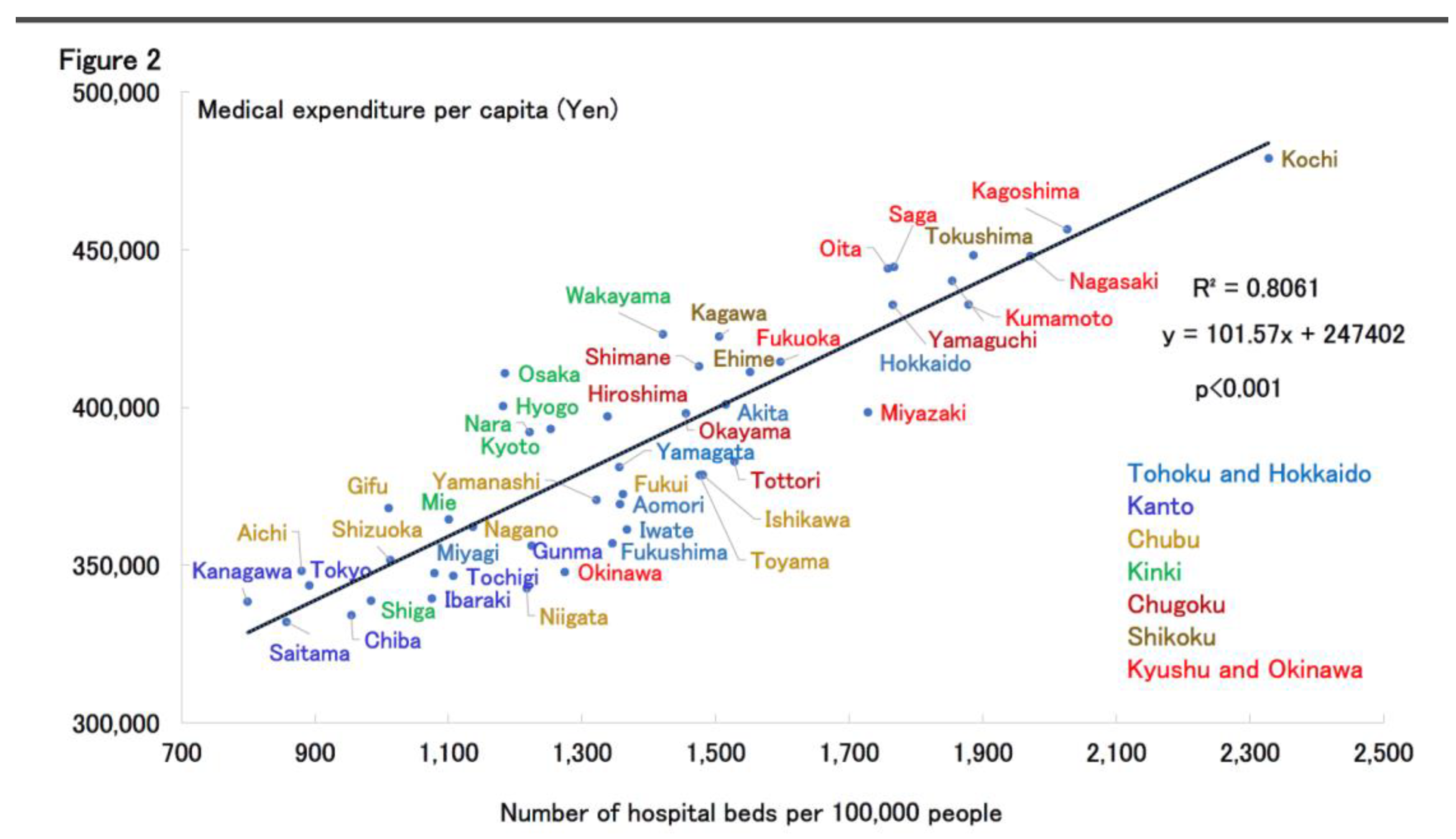

Notably, several rural prefectures in western Japan—such as Kochi, Kagoshima, Nagasaki, and Kumamoto—exhibit the highest bed densities and medical expenditure per capita. (

Figure 2) Interestingly, these regions do not consistently show worse health outcomes or markedly higher proportions of elderly residents compared to other prefectures. This regional variation cannot be explained by differences in age composition, such as the aging rate.

Economic conditions contribute significantly to these disparities. Lower land and labor costs in rural areas make hospital operation and expansion more financially feasible than in urban centers, where real estate and wages are considerably higher. Consequently, many small-scale hospitals—often established and operated by dedicated local physicians—continue to serve important roles in meeting community needs, particularly where alternative care options are limited.

In addition, alternative care models, such as home care, visiting nursing services, and community-based care, are less developed in rural areas. Although home healthcare services are available in rural areas, seamless care remains challenging due to factors such as frequent staff turnover and underdeveloped collaboration frameworks with physicians and local governments. Moreover, studies have reported that highly functional home-visit nursing providers are limited in number in these regions, resulting in persistent disparities in service availability [

10,

11]. The relative scarcity of these services often means that hospitalization remains the default setting for managing chronic diseases or rehabilitation, even when less intensive care might suffice.

Historical legacies also shape regional differences. Western Japan hosts numerous older medical schools founded before World War II, which established extensive hospital networks often maintained through alumni relationships and academic department affiliations. These longstanding institutional connections have historically supported continuity in medical education and care delivery, though they may also present challenges for adapting infrastructure to emerging needs.

5. Impact on Health Outcomes and System Efficiency

A high number of hospital beds does not necessarily lead to better health outcomes. For example, Nagano Prefecture

has low bed density and moderate healthcare spending but consistently ranks high in life expectancy and public health indicators. While bed density correlates with inpatient costs, its link to health outcomes is unclear, suggesting that abundant inpatient infrastructure is not essential for good population health.

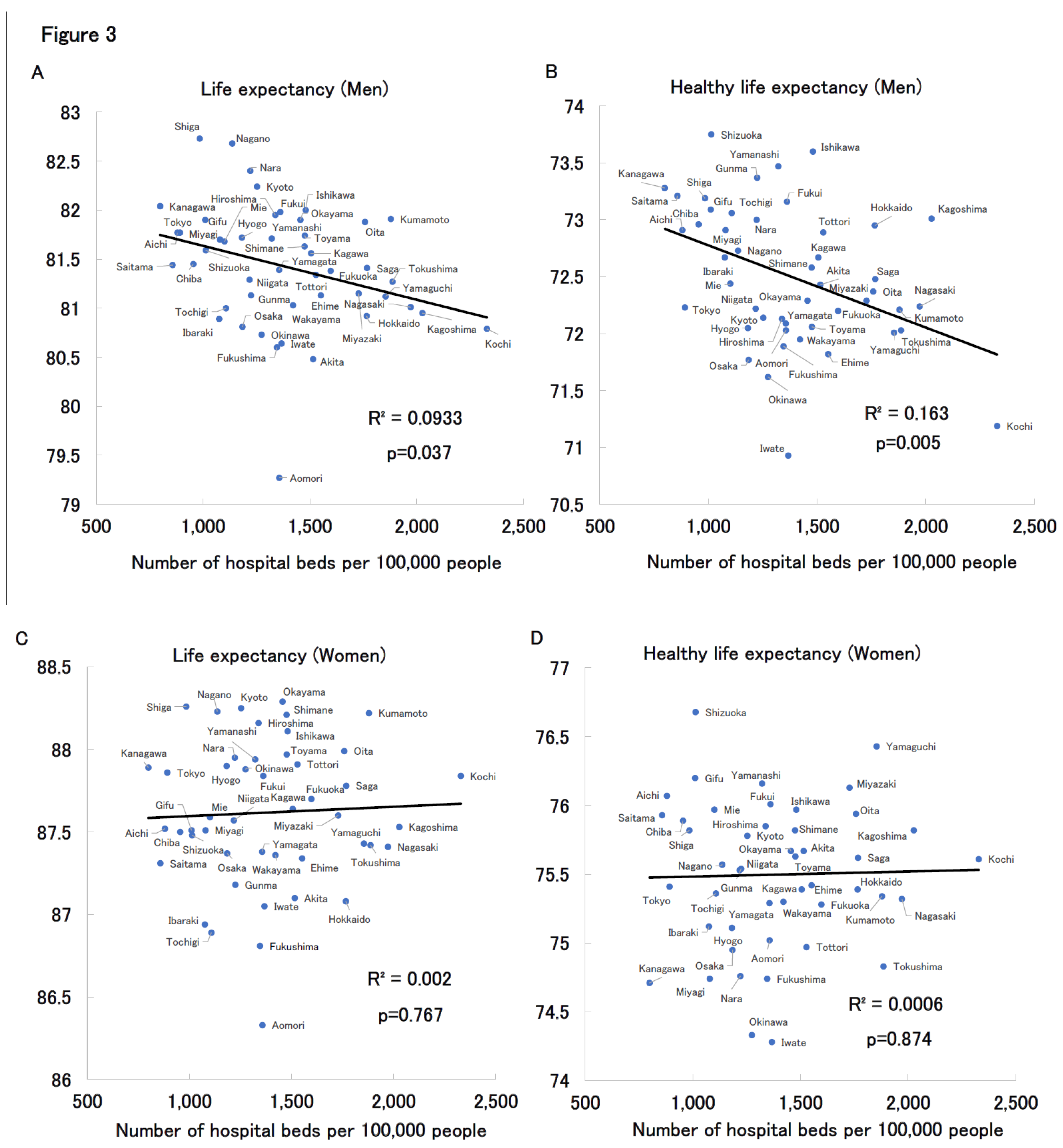

Figure 3 presents scatter plots by prefecture, stratified by sex, showing the relationships between number of hospital beds and both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. Among women, no significant correlation was observed between medical expenditures and either outcome. (

Figure 3C, D) Surprisingly, among men, both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy were negatively correlated with number of hospital beds. (

Figure 3A, B) One possible explanation for the significant association observed between healthcare expenditure and life expectancy in men—but not in women—is that women tend to have longer average and healthy life expectancies than men and generally maintain healthier lifestyles, which may make them less susceptible to the effects of the healthcare environment. In contrast, men are more likely to delay seeking medical attention until symptoms become severe, and are often diagnosed at a more advanced stage of illness. These gender-based differences in healthcare-seeking behavior may contribute to the phenomenon whereby men incur higher healthcare costs despite having shorter life expectancy. Women, on the other hand, may engage in earlier and more frequent healthcare utilization, which could attenuate the observable impact of healthcare spending on their longevity.

While these indicators do not capture the full spectrum of health outcomes, the data suggest that a higher number of hospital beds does not necessarily translate into longer or healthier lives. Conversely, regions with high bed densities often report longer hospital stays, higher rates of admissions that might be avoidable, and greater patient exposure to hospital-acquired conditions. These observations imply that surplus inpatient capacity may contribute to inefficiencies and could potentially compromise care quality.

6. The Role of Primary care physicians and generalists in Addressing Bed Oversupply

Primary care physicians and generalists, who play a pivotal role in managing a wide spectrum of inpatient cases, are uniquely positioned to contribute to addressing the challenges posed by Japan's oversupply of hospital beds. Unlike highly specialized physicians who focus narrowly on particular diseases or organ systems, generalists adopt a comprehensive, patient-centered approach that is especially suited for the multimorbid and aging population often seen in hospitals with high bed densities.

In many rural and suburban areas, generalists are the primary providers overseeing the daily care of inpatients, including those admitted for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions, rehabilitation, or extended observation. This makes generalists keenly aware of instances where hospitalizations might be avoidable, unnecessarily prolonged, or better managed through community-based alternatives. By integrating clinical judgment with a broad understanding of social determinants of health, hospital generalists can help optimize admission and discharge practices, reduce preventable admissions, and improve transitions of care.

Moreover, generalists often act as clinical leaders within small and medium-sized hospitals, especially in regions where subspecialty services are limited. Their involvement in hospital governance, quality improvement initiatives, and staff education positions them as key agents in shifting institutional culture away from bed-filling incentives toward value-based care. For example, generalists can advocate for the development of hospital-at-home programs, post-discharge follow-up systems, and tighter collaboration with home care providers—measures that directly reduce reliance on inpatient beds.

In policy discussions regarding bed consolidation and regional healthcare reform, the voices and experience of primary care physicians and generalists are critical. Their frontline insights can inform evidence-based decisions on resource allocation and help ensure that any reduction in bed numbers does not compromise access to care for vulnerable populations. Recognizing and empowering generalists as stewards of both clinical appropriateness and system efficiency is thus essential to Japan’s pursuit of a more sustainable and equitable healthcare system.

7. Case Study: Yubari City’s Hospital Closure and Its Impact on Health Outcomes and Expenditures

Yubari City in Hokkaido, once a prosperous coal-mining town in first half of the 20th century, experienced a dramatic population decline following the closure of its mines and eventually declared municipal bankruptcy in 2007. As a result, the city’s only advanced medical facility—a 171-bed municipal general hospital—was downsized to a 19-bed inpatient clinic and a 40-bed long-term care facility, effectively reducing inpatient hospital beds in the city to near zero.

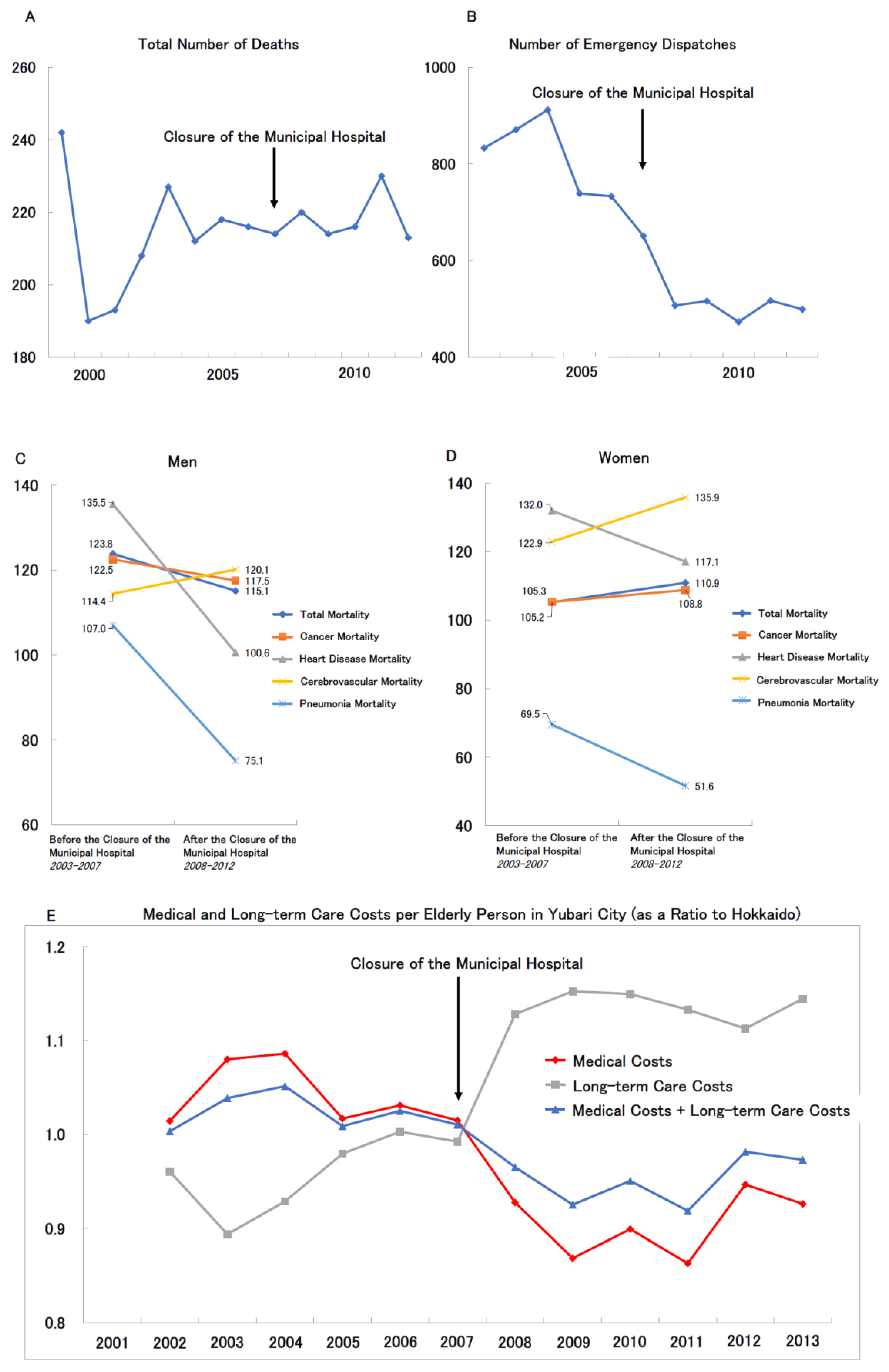

Remarkably, despite a rapidly aging population, there was no substantial change in the city’s total mortality before and after the hospital closure (

Figure 4A). In fact, the number of emergency transports significantly declined post-closure (

Figure 4B). Sex-specific standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) for all-cause mortality, cancer, and heart disease remained stable or slightly decreased (

Figures 4C and 4D). Although cerebrovascular mortality increased slightly for both sexes, pneumonia-related mortality showed a notable decline. This may be attributed to residents’ proactive efforts to receive pneumococcal vaccinations and enhanced oral care for aspiration pneumonia prevention, driven by local dentists and community health initiatives. These preventive activities appear to have intensified after the hospital’s closure.

Figure 4E illustrates the trend in per-capita medical and long-term care expenditures for older adults in Yubari, expressed as a ratio to the overall averages in Hokkaido. Following the hospital closure, medical expenditures dropped sharply, while long-term care costs increased significantly, suggesting a shift from medical services to community-based care. Overall, the combined per-capita cost of medical and long-term care decreased relative to the Hokkaido average.

In summary, despite the closure of Yubari’s general hospital in 2007 and the near-elimination of inpatient beds, SMRs for all-cause, cancer, cardiovascular, and pneumonia mortality remained unchanged or decreased. Concurrently, healthcare expenditures and emergency transports declined, indicating a reduced societal burden of healthcare.

Several factors likely contributed to Yubari’s ability to sustain health outcomes: the development of an integrated 24-hour medical and long-term care system; strengthened social networks within the community; and increased health awareness and preventive behavior among residents. This shift from hospital-centered acute care to community-based, supportive care was facilitated by the active involvement of primary care and generalist physicians, who played a central role in maintaining local healthcare.

A potential counterargument is that improvements in Yubari’s health indicators and cost reductions may simply reflect the out-migration of high-dependency patients to other municipalities. To examine this possibility, the number of dialysis patients—who typically require high-cost, intensive care—was analyzed. Using two indicators (the number of certified physically disabled residents with renal impairment from 2006 to 2012, and new dialysis initiations from 1999 to 2009), little change was found before and after the municipal bankruptcy. Although dialysis patient numbers remained stable, further research is warranted to assess whether patients with other high-dependency conditions may have relocated to access care elsewhere, these findings suggest that no large-scale outflow of severely disease patients occurred.

It is important to note that Yubari is a relatively small municipality, with a tightly knit community structure that may have facilitated public engagement and collective action. Additionally, the city’s proximity to Sapporo may have allowed some access to tertiary care facilities when necessary. Therefore, Yubari’s experience may not be entirely generalizable to all municipalities.

While health indicators appeared stable following the hospital closure, it is essential to note that mortality rates alone may not fully capture the broader health impact, particularly regarding chronic disease progression, quality of life, or unmet healthcare needs. Nevertheless, the series of events surrounding Yubari’s hospital closure offer important insights for the future of healthcare in Japan, particularly as discussions intensify around hospital downsizing and strategic withdrawal. Yubari may serve as a valuable model for reimagining healthcare delivery in a super-aged society.

8. Policy Considerations for Sustainable and Equitable Care

To ensure the sustainability and equity of Japan’s healthcare system amidst demographic and economic challenges,

a multifaceted approach is warranted:

・Regional Bed Planning Based on Evidence: Adoption of tools and frameworks to assess appropriate bed numbers according to regional population demographics, disease burden, and service utilization trends can help align supply with actual need. Countries like France, Canada, and Germany provide useful models for such evidence-based planning.

・Promoting Hospital Consolidation and Service Diversification: Financial and administrative incentives can encourage small hospitals, especially in rural areas, to merge or transition toward outpatient, rehabilitation, or long-term care services. Such restructuring can optimize resource use while preserving access to essential care.

・Strengthening Community-Based and Outpatient Care: Investment in home care providers, public health nursing, primary care clinics, and integrated care platforms is essential to reduce reliance on inpatient services. Training and deploying community health workers can further support chronic disease management and health promotion.

・Reforming Payment Systems: Gradual transition from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based or bundled payment models can better incentivize quality, efficiency, and patient outcomes, mitigating the tendency toward unnecessary service volume.

・Engaging Stakeholders Collaboratively: Successful reform depends on the participation of medical associations, hospital leaders, policymakers, and local communities. Transparent data sharing, consensus-building, and shared decision-making processes can help ensure reforms are contextually appropriate and broadly supported.

9. Conclusion

Japan’s healthcare system has long relied on the dedication of local physicians and community-based practitioners, especially in rural areas, to maintain access and quality of care. Their vital contributions remain the foundation of public health and deserve utmost respect. However, demographic changes and economic realities now require a reassessment of resource allocation. This study highlights that an oversupply of hospital beds, particularly where physicians are scarce, can lead to inefficiencies without clear health benefits. The example of Yubari City demonstrates that well-coordinated, community-based care led by generalist physicians can sustain health outcomes even with limited inpatient facilities. Looking ahead, healthcare reform must be regionally tailored, data-driven, and developed in close collaboration with frontline medical professionals. Embracing sustainable, culturally appropriate models centered on primary and generalist care, Japan—facing advanced aging and population decline—can pioneer a global approach to health in shrinking societies. Population decline, from an environmental and societal sustainability perspective, is not purely negative and may guide future sustainable development worldwide.

Author Contributions

Hiroshi Kusunoki: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; writing–review and editing. Hiroyuki Morita: Supervision; writing–review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Funding Information

The authors received no funding for this work.

Conflict Of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

References

- Kusunoki H. Unraveling Rising Mortality: Statistical Insights from Japan and International Comparisons. Healthcare (Basel). 2025 May 30;13(11):1305. [CrossRef]

- Devanathan G, Chua PLC, Nomura S, Ng CFS, Hossain N, Eguchi A, Hashizume M. Excess mortality during and after the COVID-19 emergency in Japan: a two-stage interrupted time-series design. BMJ Public Health. 2025 Apr 5;3(1):e002357. [CrossRef]

- https://www.satsuki-jutaku.mlit.go.jp/journal/article/p=2325.

-

https://www.m3.com/news/iryoishin/1288335.

-

https://www.byoinshinbun.com/nitibyo_news.php?id=421.

- Morita H. Analysis of Factors Contributing to the Reduction in Per Capita Medical Expenditure for Elderly Residents in Yubari City," Social Insurance Journal (Issue 2584), pp. 12–29, November 1, 2014.

-

https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1522262180335660288.

-

https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/hospital-beds.html.

-

https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/doctors.html.

- Une H. Medical expenditure for the elderly and factors related to its geographical variations within Fukuoka Prefecture. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 1996 Jan;43(1):28-36.

- Ohta R, Ryu Y, Katsube T, Sano C. Rural Homecare Nurses' Challenges in Providing Seamless Patient Care in Rural Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Dec 13;17(24):9330. [CrossRef]

- Fukui S, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Fujita J. Five types of home-visit nursing agencies in Japan based on characteristics of service delivery: cluster analysis of three nationwide surveys. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014 Dec 20;14:644. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).