By aligning infrastructure with actual needs and encouraging efficient, quality care, Japan can maintain its healthcare excellence while addressing emerging challenges.

1. Introduction

Japan’s healthcare system is widely recognized for its universal health coverage, low infant mortality rates, and among the highest life expectancies globally. These accomplishments have been built over decades of dedicated efforts by healthcare professionals, policymakers, and communities alike. The system’s accessibility and quality have made it a model for many countries seeking to improve public health.

However, Japan currently faces new challenges arising from demographic changes such as rapid population aging and a shrinking workforce, alongside persistent regional disparities in healthcare resource distribution. These challenges call for a reexamination of how healthcare services are organized and delivered across the country.

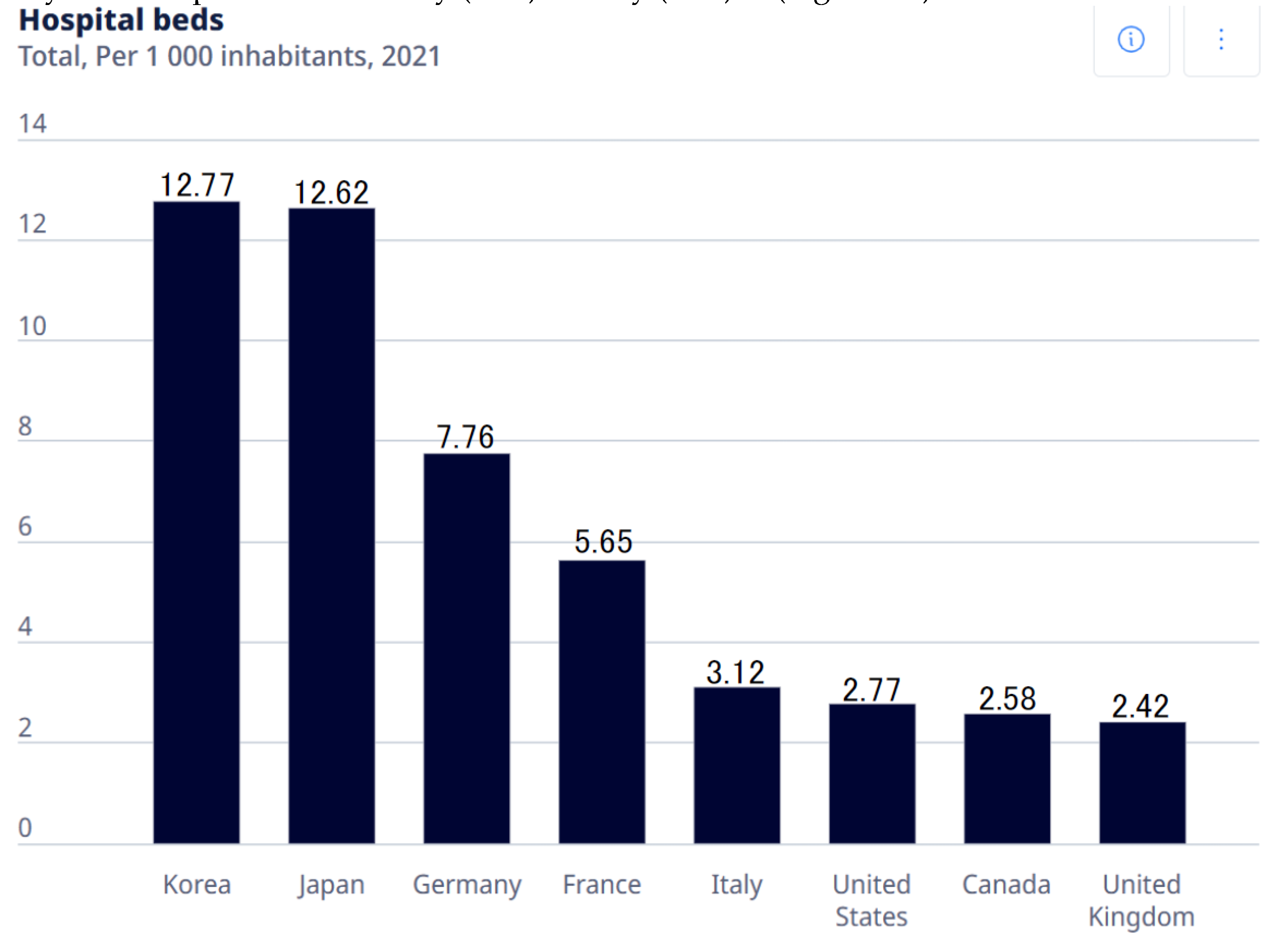

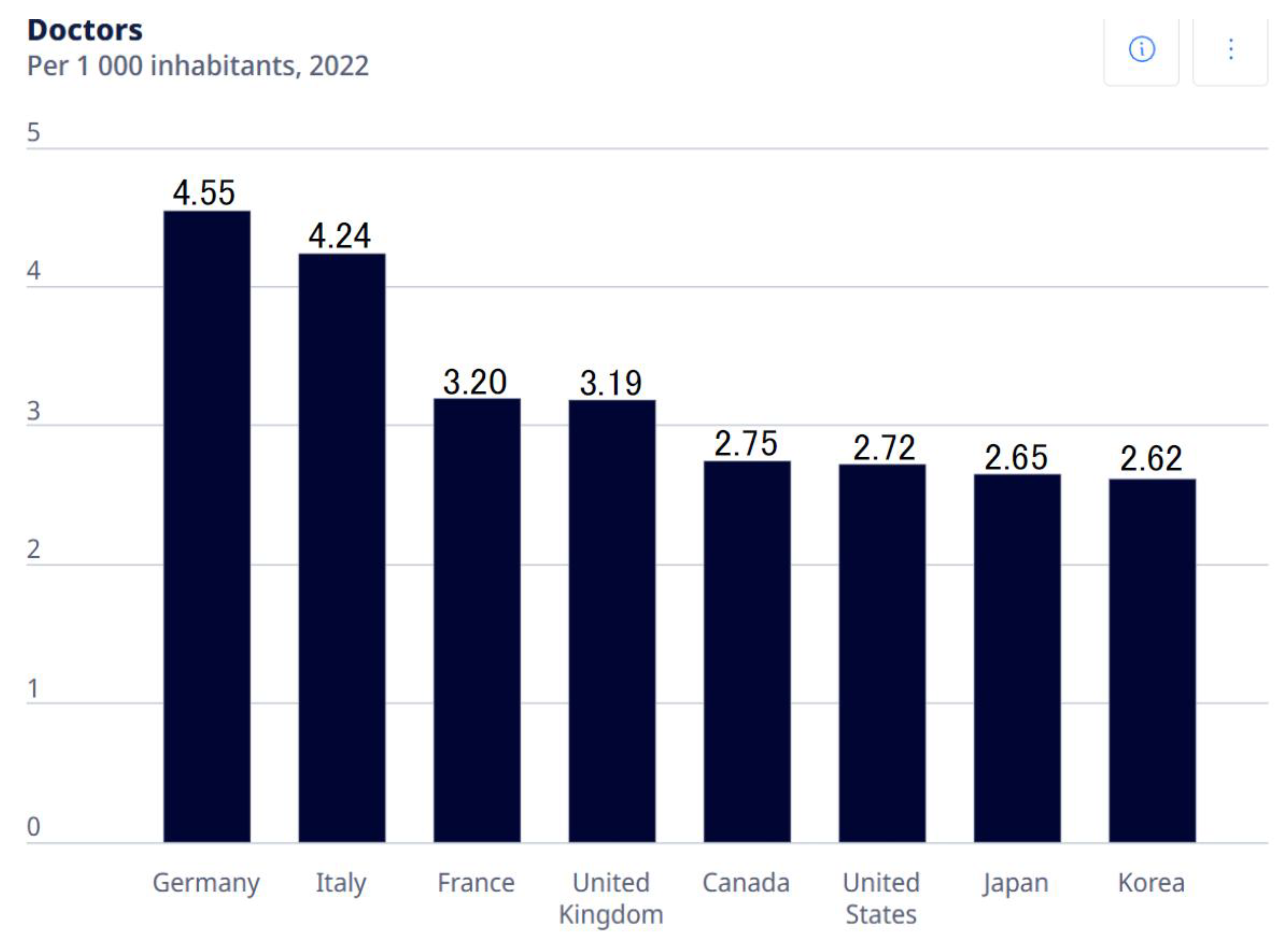

This Opinion piece argues that Japan's unusually high density of hospital beds—especially in rural regions—drives inefficiencies in healthcare delivery, distorts resource allocation, and must be urgently addressed through structural reforms. While Japan maintains a relatively modest physician-to-population ratio compared to other developed countries, its density of hospital beds per capita remains among the highest worldwide. This paradox invites important questions about the relationship between infrastructure availability, medical need, healthcare utilization, and expenditures.

This Opinion piece seeks to explore the structural and historical factors shaping Japan’s hospital landscape, with a focus on regional variations. It draws on national and international data to consider how hospital bed availability influences healthcare costs and delivery patterns. Finally, it offers policy considerations aimed at supporting the continued sustainability, equity, and quality of Japan’s healthcare system.

2. Japan’s Healthcare Context in International Perspective

According to OECD data from 2021, Japan had approximately 12.62 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants. This is the second highest, closely following Korea. This figure is nearly double that of countries like Germany (7.76 beds per 1,000) or France (5.65 beds per 1,000)

1). (

Figure 1A) In stark contrast, Japan’s physician density stands at around 2.65 physicians per 1,000 people, which is relatively low compared to Germany (4.55) or Italy (4.24)

2). (

Figure 1B)

This combination of high hospital bed availability alongside a comparatively low physician density is quite unusual among developed countries. Many OECD members employ centralized healthcare planning mechanisms, regulating the establishment of new hospitals and the allocation of beds based on regional population health needs and projected demand. This ensures that healthcare infrastructure is matched closely to the epidemiological and demographic profiles of each area.

Japan’s system differs in that it permits a relatively free market entry for new medical facilities. Licensed physicians can establish hospitals or clinics by fulfilling certain minimum requirements. Until the 1980s, supply regulation through hospital bed controls was not implemented. This policy was designed in the postwar era to rapidly increase access to healthcare across the country. While this approach has succeeded in improving geographic access to medical services, it also introduces challenges in coordinating resources effectively and controlling healthcare spending. Understanding the implications of this unique balance between market forces and regulation is essential for addressing emerging inefficiencies.

3. Structural Factors Influencing Hospital Bed Supply and Utilization

Japan’s healthcare infrastructure is heavily shaped by its historical context. After World War II, the priority was to expand access rapidly, resulting in a free-entry system where more than 80% of hospitals are privately owned and operated, often by individual physicians or small family-run organizations. This decentralized ownership structure contributed to the proliferation of hospitals, especially in areas where demand appeared stable or growing.

Compounding this is the national health insurance reimbursement scheme, which primarily relies on a fee-for-service payment model. Under this system, providers are paid for each diagnostic test, procedure, and inpatient day. Such volume-based remuneration creates financial incentives for hospitals to maximize admissions, prolong lengths of stay, and maintain high occupancy rates.

Unlike other systems that use global budgeting, capitation, or bundled payments to contain volume-driven care, Japan currently lacks stringent mechanisms to cap hospital bed supply or the overall volume of reimbursed services. Consequently, hospital operators may regard maintaining a large bed capacity as a business imperative rather than merely a clinical necessity.

These structural incentives can give rise to supply-induced demand, where the availability of hospital beds itself influences hospitalization rates, sometimes beyond what is strictly medically necessary.

4. Regional Variations and Economic Influences

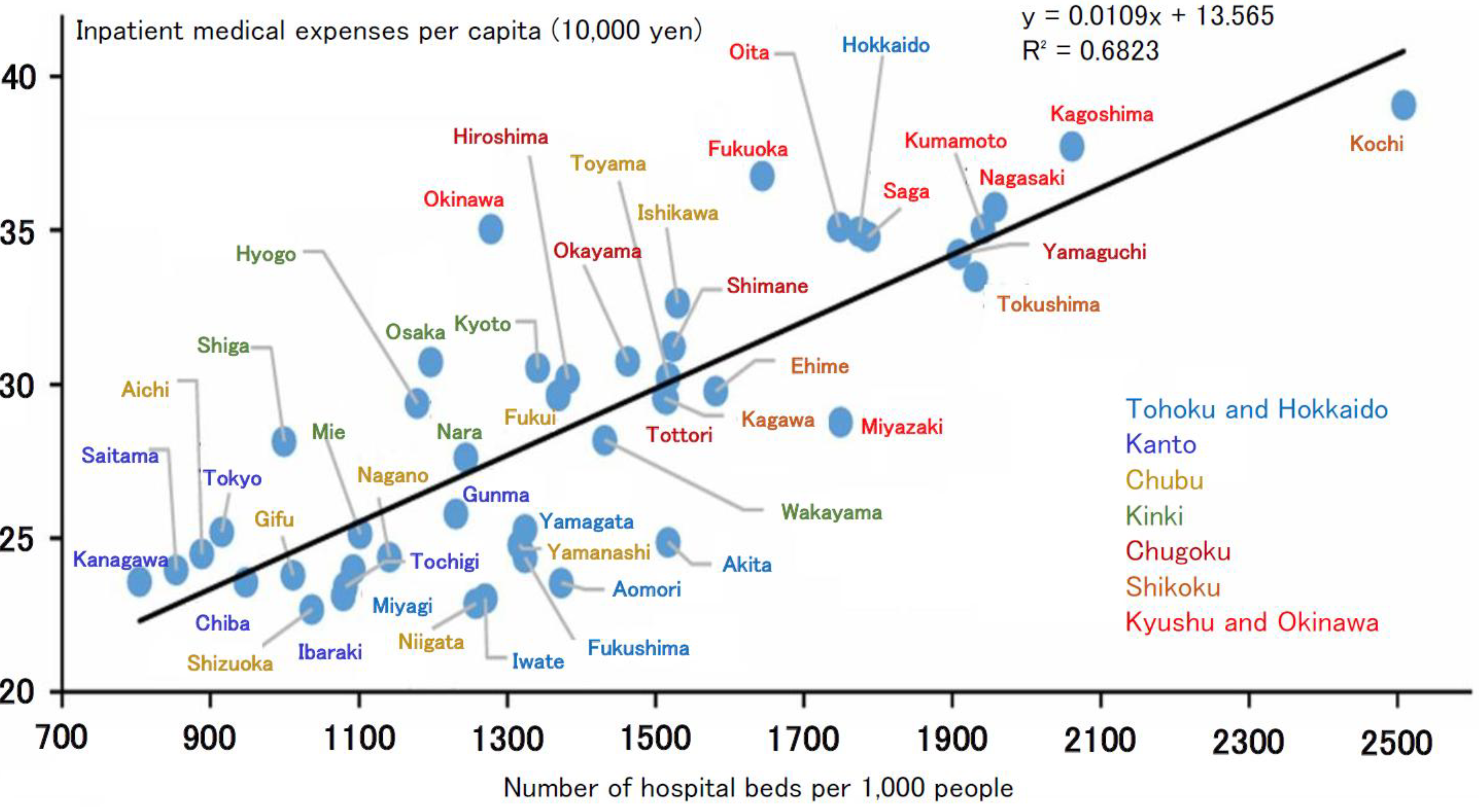

An examination of data across Japan’s 47 prefectures reveals substantial variation in hospital bed density and inpatient expenditures. Notably, several rural prefectures in western Japan—such as Kochi, Kagoshima, Nagasaki, and Kumamoto—exhibit the highest bed densities and inpatient costs per capita

3). (

Figure 2) Interestingly, these regions do not consistently show worse health outcomes or markedly higher proportions of elderly residents compared to other prefectures.

Economic conditions contribute significantly to these disparities. Lower land and labor costs in rural areas make hospital operation and expansion more financially feasible than in urban centers, where real estate and wages are considerably higher. Consequently, many small-scale hospitals—sometimes run by single physicians or families—continue to operate viably in these regions.

In addition, alternative care models, such as outpatient clinics, home care, visiting nursing services, and community-based care, are less developed in rural areas. The relative scarcity of these services often means that hospitalization remains the default setting for managing chronic diseases or rehabilitation, even when less intensive care might suffice.

Historical legacies also shape regional differences. Western Japan hosts numerous older medical schools founded before World War II, which established extensive hospital networks often maintained through alumni relationships and academic department (“ikyoku”) affiliations. These longstanding institutional connections reinforce existing infrastructure patterns, making change challenging.

5. Impact on Health Outcomes and System Efficiency

A critical question is whether an abundance of hospital beds translates into better health outcomes. Evidence suggests that this is not necessarily the case. Nagano Prefecture, which has relatively low bed density and moderate healthcare expenditures, consistently ranks among the highest nationally in life expectancy and other public health indicators.While hospital bed density is strongly associated with regional inpatient expenditures, its correlation with key health outcomes, such as life expectancy, is far less clear. In fact, some regions with low bed density, such as Nagano, consistently report favorable health indicators, suggesting that an abundance of inpatient infrastructure is not necessarily a prerequisite for better population health.

Conversely, regions with high bed densities often report longer hospital stays, higher rates of admissions that might be avoidable, and greater patient exposure to hospital-acquired conditions. These observations imply that surplus inpatient capacity may contribute to inefficiencies and could potentially compromise care quality.

A study analyzed how healthcare resources, socioeconomic, and sociodemographic factors influence hospitalization costs for the elderly across varying levels of urbanization in Japan. Using regional data and regression analysis, it found that medical and sociodemographic factors were more impactful in rural areas, while hospital bed numbers and socioeconomic conditions mattered more in urban settings 4). Additionally, projections for 2025 based on prefectural estimates reveal persistent regional disparities in medical supply and demand across secondary medical areas, highlighting the need for urbanization-sensitive healthcare policy reforms 5). Addressing these complex issues requires balancing access to necessary inpatient care with efforts to improve care coordination, reduce unnecessary hospitalization, and enhance overall system efficiency.

6. Policy Considerations for Sustainable and Equitable Care

To ensure the sustainability and equity of Japan’s healthcare system amidst demographic and economic challenges, a multifaceted approach is warranted:

Regional Bed Planning Based on Evidence: Adoption of tools and frameworks to assess appropriate bed numbers according to regional population demographics, disease burden, and service utilization trends can help align supply with actual need. Countries like France, Canada, and Germany provide useful models for such evidence-based planning.

Promoting Hospital Consolidation and Service Diversification: Financial and administrative incentives can encourage small hospitals, especially in rural areas, to merge or transition toward outpatient, rehabilitation, or long-term care services. Such restructuring can optimize resource use while preserving access to essential care.

Strengthening Community-Based and Outpatient Care: Investment in home care providers, public health nursing, primary care clinics, and integrated care platforms is essential to reduce reliance on inpatient services. Training and deploying community health workers can further support chronic disease management and health promotion.

Reforming Payment Systems: Gradual transition from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based or bundled payment models can better incentivize quality, efficiency, and patient outcomes, mitigating the tendency toward unnecessary service volume.

Engaging Stakeholders Collaboratively: Successful reform depends on the participation of medical associations, hospital leaders, policymakers, and local communities. Transparent data sharing, consensus-building, and shared decision-making processes can help ensure reforms are contextually appropriate and broadly supported.

7. Conclusion

Japan’s healthcare system stands as a global exemplar of universal access and strong health outcomes. Nonetheless, evolving demographic realities and persistent regional disparities in healthcare infrastructure necessitate adaptive reforms.

Hospital bed distribution reflects a complex interplay of historical, economic, and regulatory factors influencing healthcare delivery and expenditures. While sufficient inpatient capacity remains vital for quality care, oversupply in certain regions contributes to inefficiencies and increased costs.

By fostering evidence-informed, collaborative approaches to resource allocation and care delivery, Japan can sustain its healthcare achievements while enhancing efficiency, equity, and quality. Constructive dialogue among healthcare professionals, policymakers, and communities will be crucial in navigating this path forward.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).