Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Change and Personal Construct Systems

1.2. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps as Quantitative Models

1.3. Centrality Measures in Graph Theory

2. Mathematical Foundations

2.1. FCM of Psychological Change

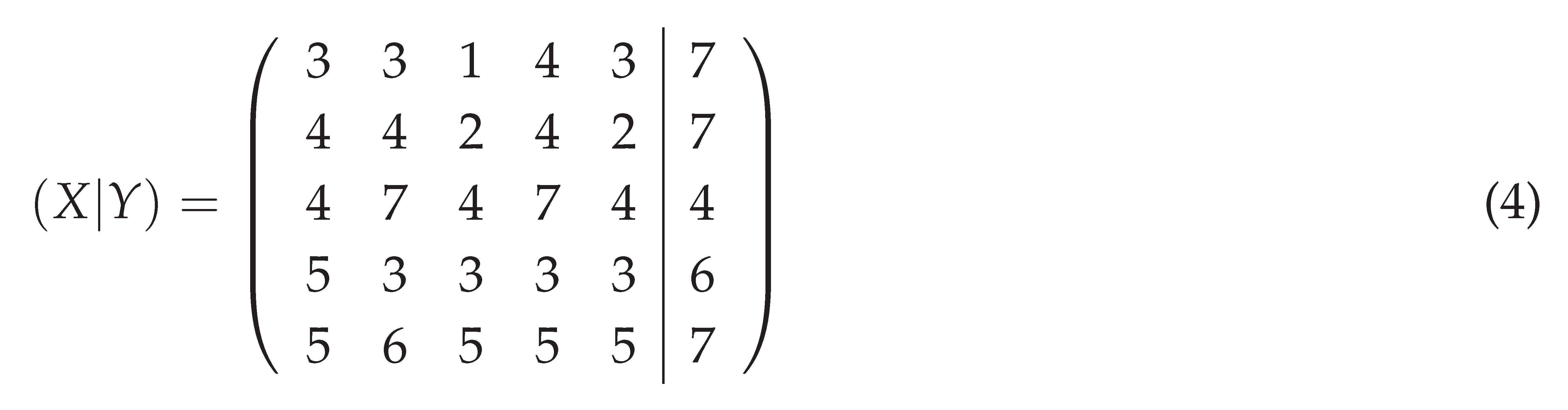

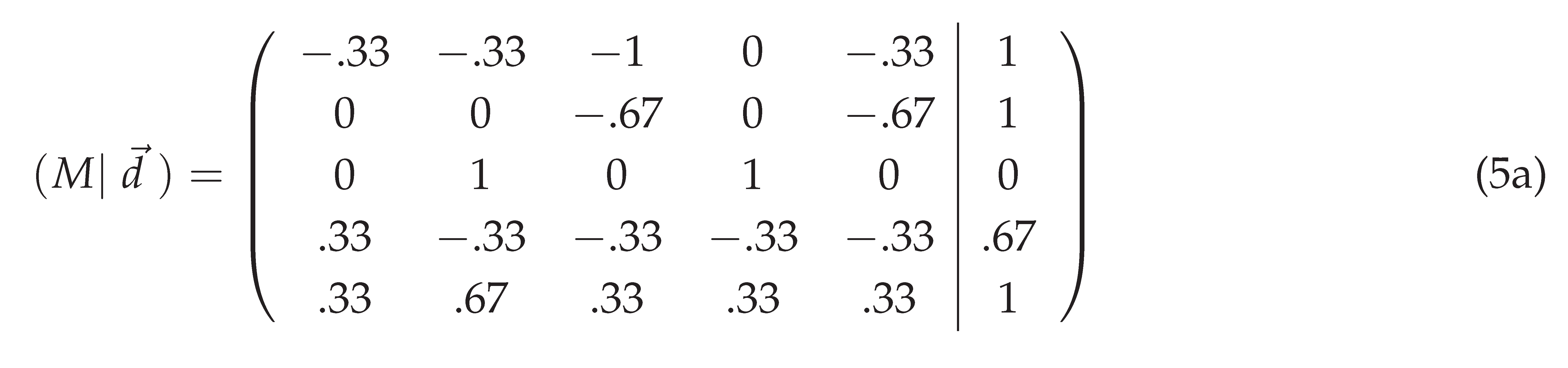

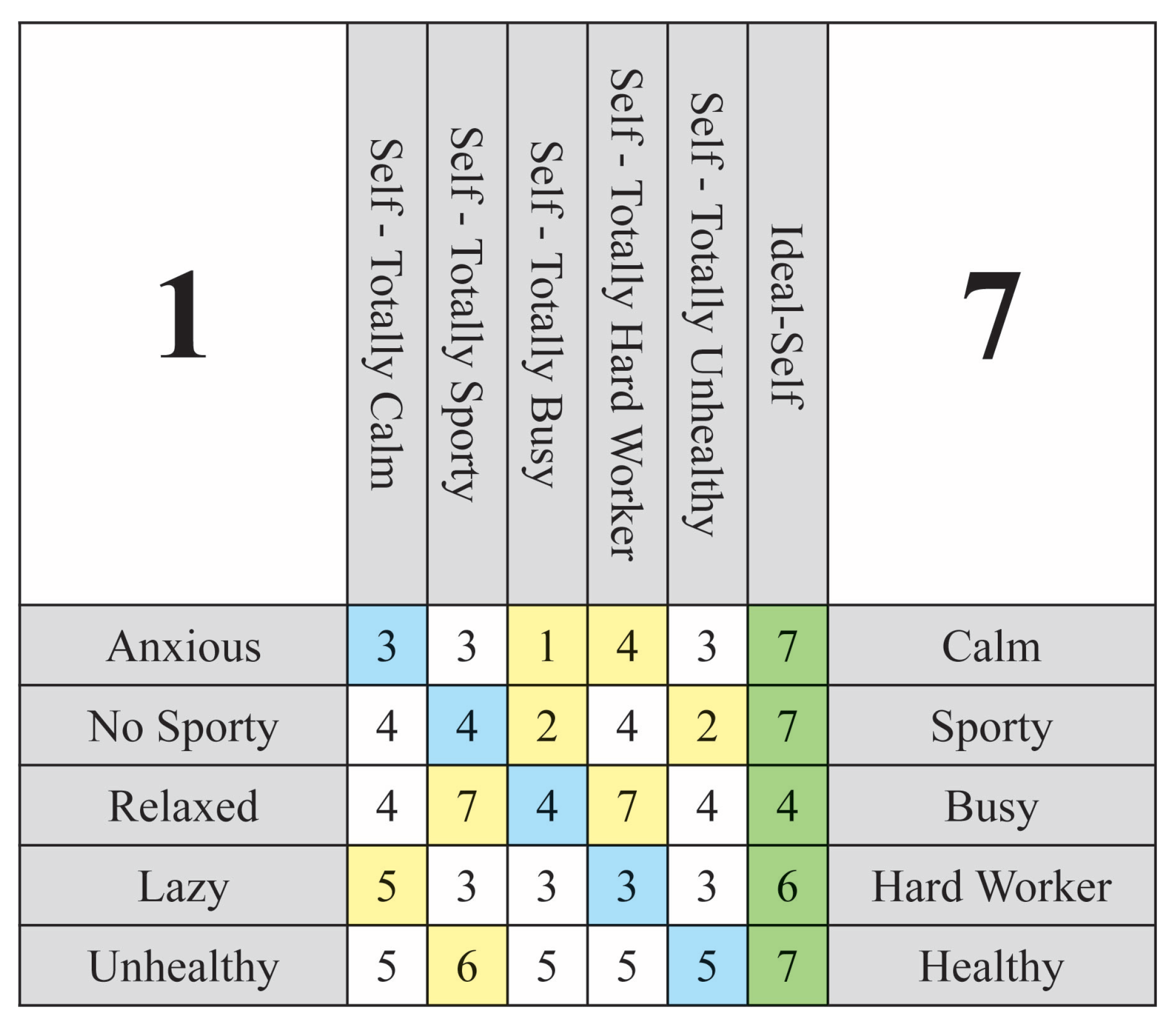

- The matrix M encodes the hypothetical selves, where represents the hypothetical score of construct j when construct i undergoes a hypothetical shift (). Thus, reflects how construct j is influenced by changes in construct i.

- The Self-Now vector provides the baseline values for each construct, where is the score for construct j in its present state. The difference therefore measures the deviation of construct j under the hypothetical shift, , associated with construct i from its baseline state.

- The hypothetical intensity vector captures the proposed changes in the interview. The difference quantifies the magnitude of the hypothetical change introduced to construct i.

- From the Linearity of Change Axiom (Axiom 1), we assume that the relationship between the change in construct i and the corresponding change in construct j can be described as proportional. This proportionality is expressed by:where is the proportionality coefficient that quantifies the influence of construct i on construct j.

- Applying this axiom to the hypothetical scenario, we relate the deviation of construct j () to the magnitude of the shift introduced to construct i (). Specifically, the weight is given by normalizing the deviation with respect to the hypothetical intensity :

- Equation (3) quantifies the sensitivity of construct j to changes in construct i under the assumption of linearity. This process is applied to all pairs of constructs , resulting in the weight matrix W, which captures the pairwise relationships across the entire system.

- , where each vertex corresponds to a construct.

- , where if and only if .

- assigns attributes to vertices, where .

- assigns weights to edges, where .

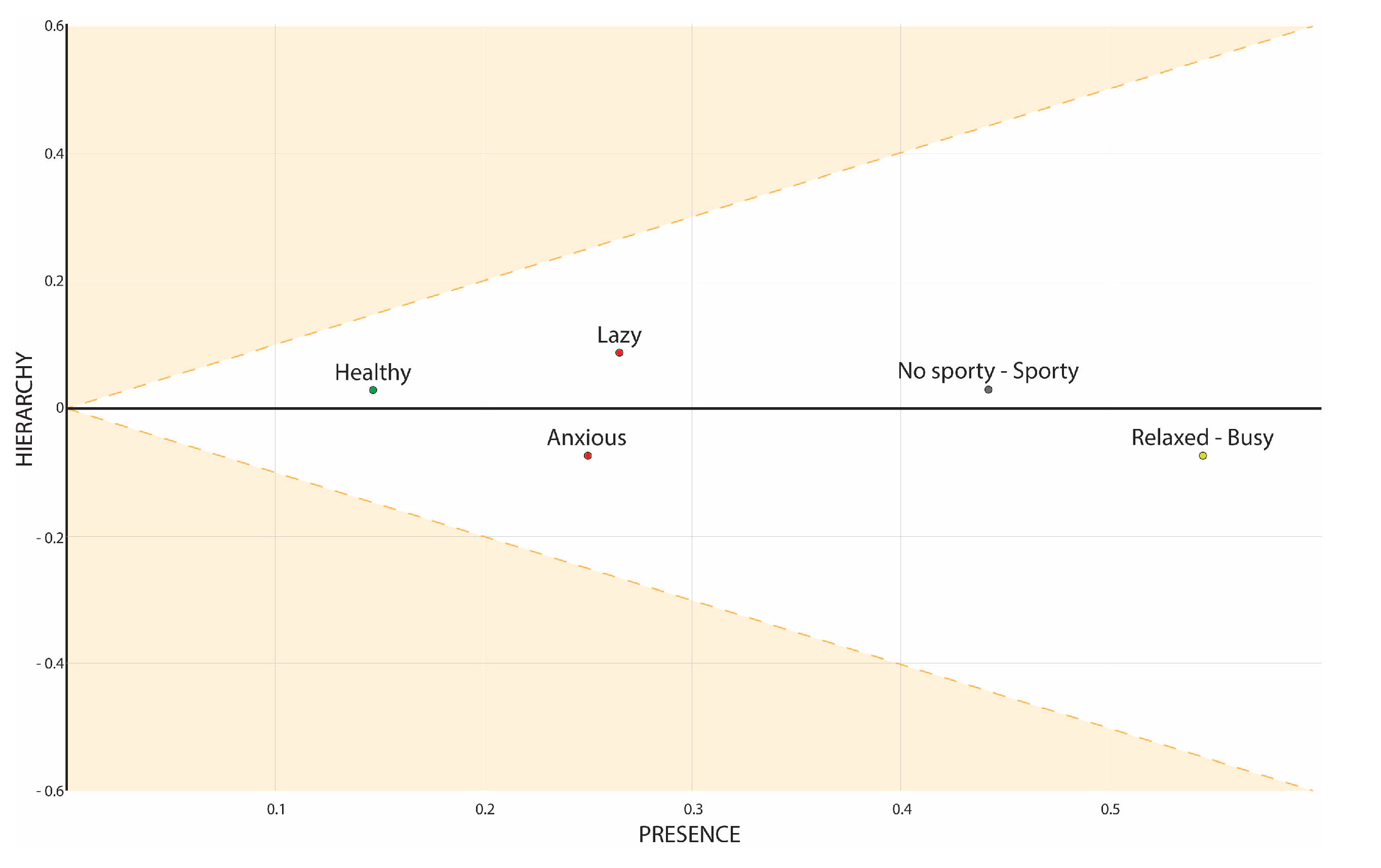

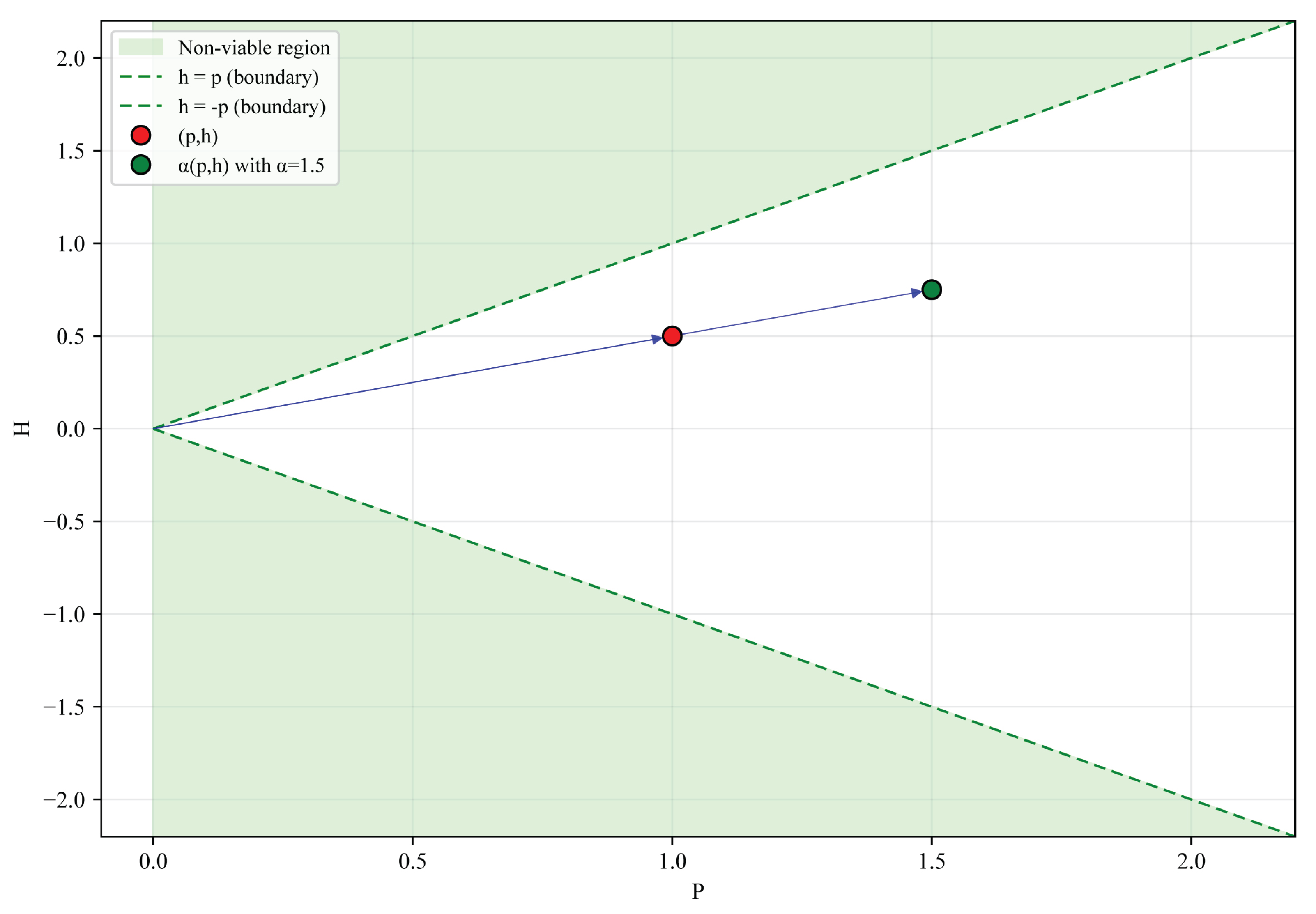

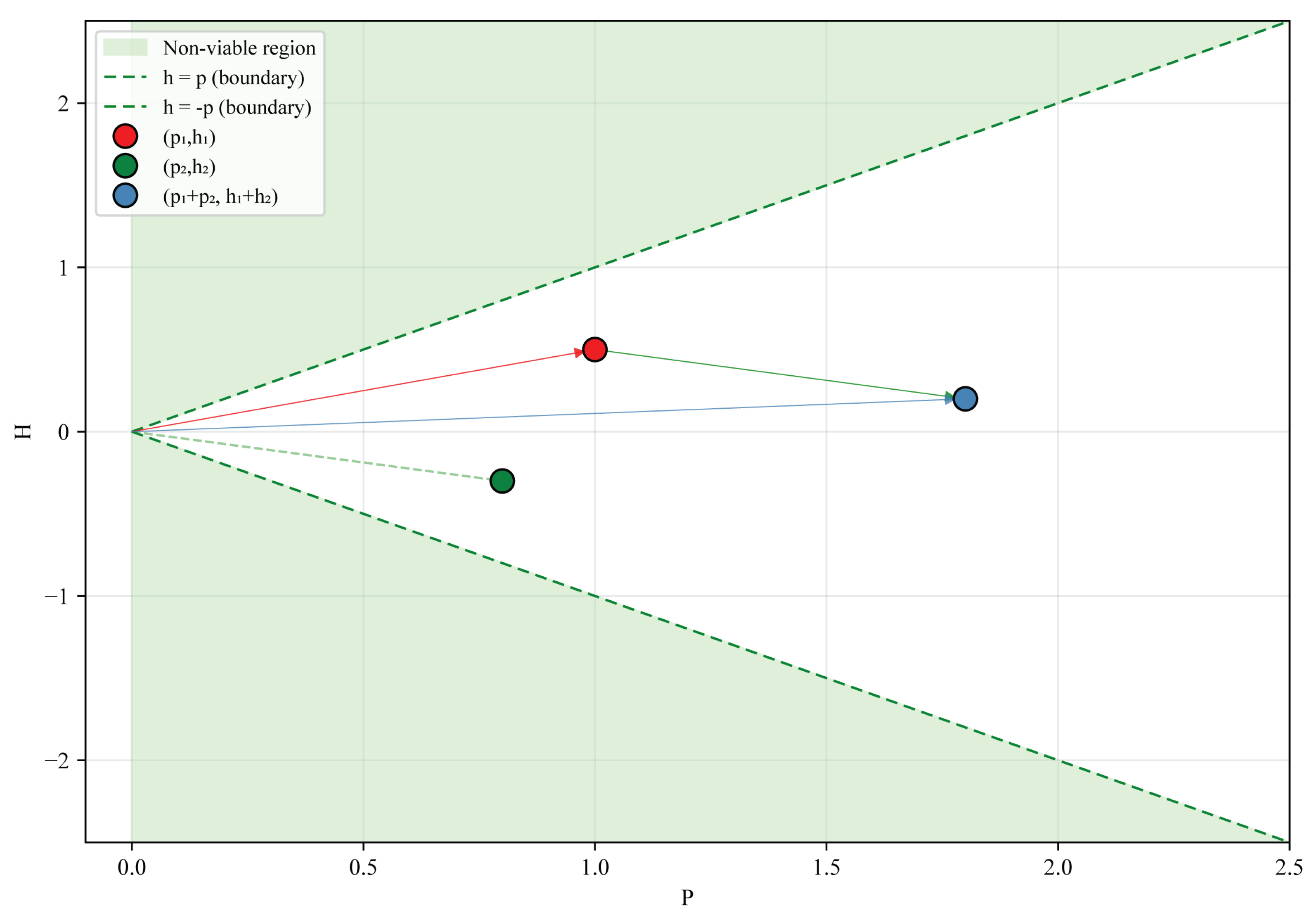

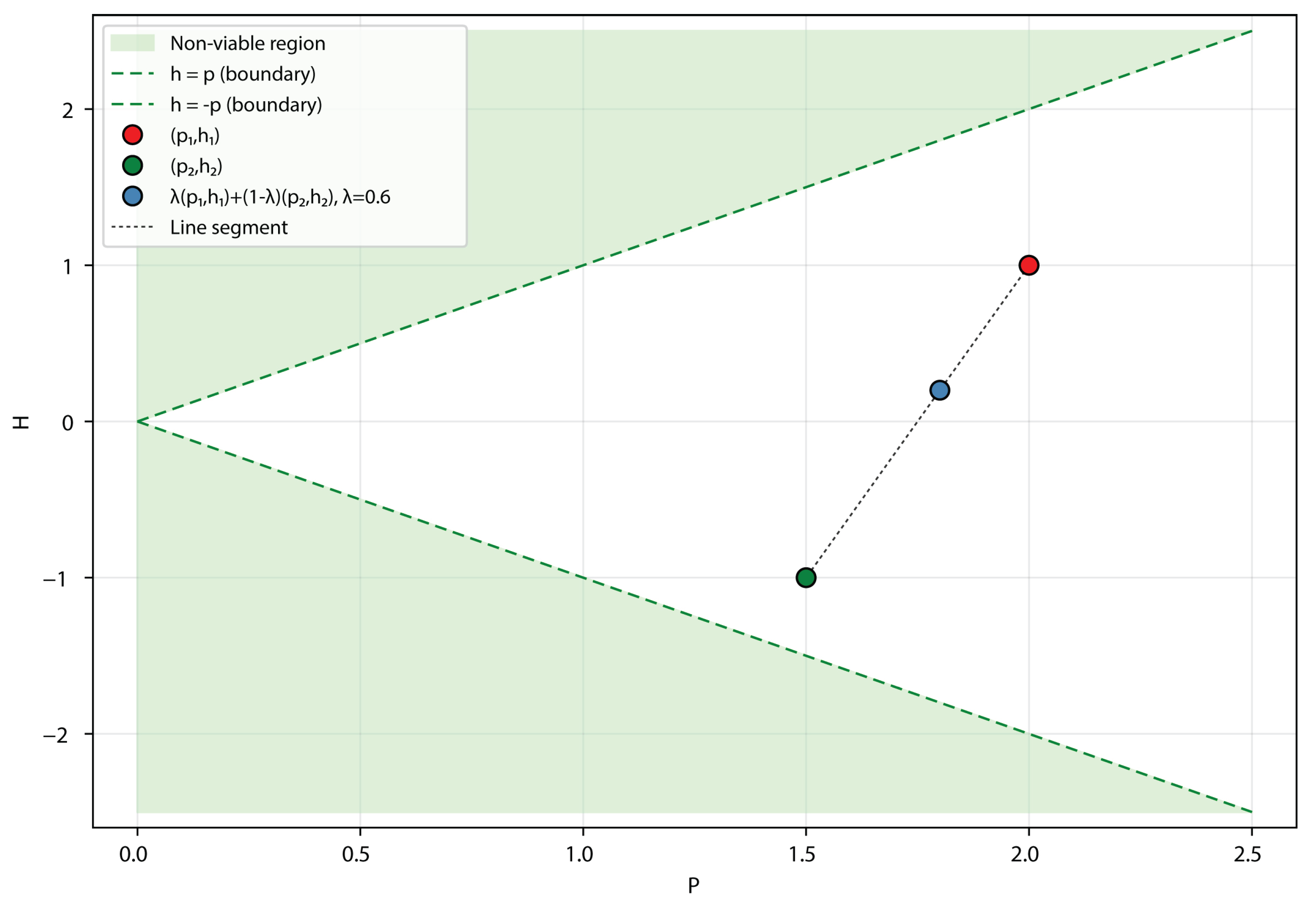

2.2. PH Space

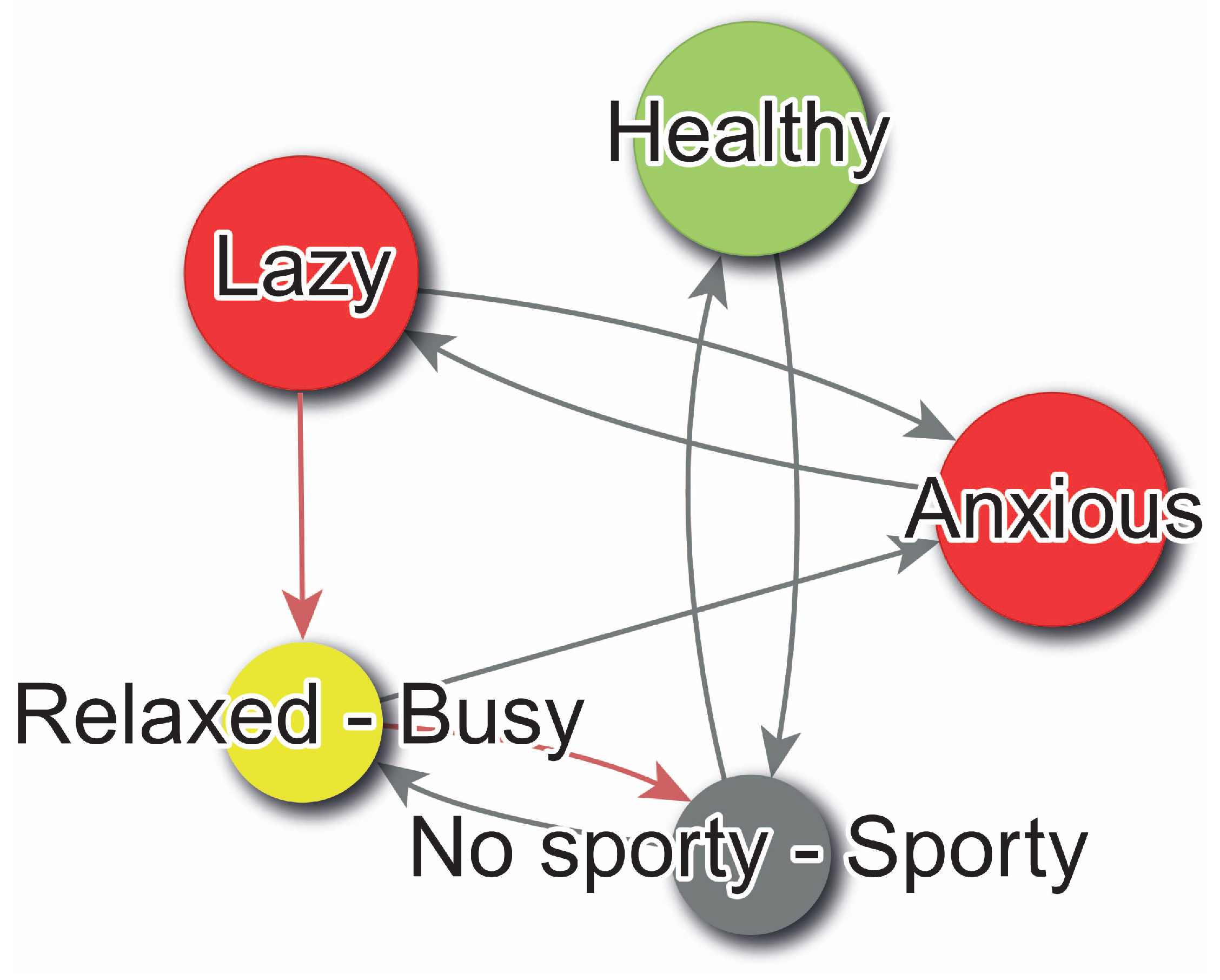

- is said to be supraordinate if , meaning the vertex exerts more influence (outputs) than it receives (inputs).

- is said to be subordinate if , meaning the vertex is more influenced by other vertices (inputs) than it influences them (outputs).

- is said to be neutral if , meaning the vertex has an equal balance of influence received (inputs) and exerted (outputs).

- Presence index () represents the projection of the vector onto the axis defined by , capturing the total connectivity of vertex , i.e., .

- Hierarchy index () represents the projection of the vector onto the axis defined by , capturing the net difference between and , i.e., .

2.3. Properties of the PH Space

2.3.1. Bounding Theorem and Geometric Constraint

- If , i.e., the node is a pure source, then .

- If , i.e., the node is a pure sink, then . □

2.3.2. Geometric Formulation

2.3.3. Graph Projections and Asymptotic Behavior

- -

- (source: )

- -

- (balanced: )

- Achieving A requires a node with (max out-strength).

- Achieving C requires another node with (max connections).

2.3.4. Interpretational Implications

3. Discussion

3.1. Applications

3.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FCM | Fuzzy Cognitive Map |

| PCP | Personal Construct Psychology |

| PH | Presence–Hierarchy |

| WimpGrid | Weighted Implication Grid |

References

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs; Norton: New York, 1955.

- Fransella, F.; Bell, R.; Bannister, D. A Manual for Repertory Grid Technique; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2004.

- Procter, H.; Winter, D.A. Personal and Relational Construct Psychotherapy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2020.

- Hinkle, D.N. The Change of Personal Constructs from the Viewpoint of a Theory of Construct Implications. PhD thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, 1965.

- Bell, R.C. Did Hinkle prove laddered constructs are superordinate? A re-examination of his data suggests not. Personal Construct Theory and Practice 2014, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Korenini, B. What do Hinkle’s data really say about laddering? Personal Construct Theory and Practice 2016, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kosko, B. Fuzzy cognitive maps. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 1986, 24, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Mendel, J.M. Generating fuzzy rules by learning from examples. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1992, 22, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsadiras, A.K. Fuzzy cognitive maps for decision support in social systems. Journal of Systems Research and Behavioral Science 2008, 25, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, G.; Nápoles, G.; Falcon, R.; Vanhoof, K. A review on methods and software for fuzzy cognitive maps. Artificial Intelligence Review 2019, 52, 1707–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfeliciano, A.; Sául, L.A.; Botella, L. Weighted implication grid: A graph-theoretic approach to modelling psychological change. Frontiers in Psychology 2025. In press.

- Sanfeliciano, A.; Saúl, L.A. WimpTools: A Graph-Theoretical R Toolbox for Modeling Psychological Change (1.0.0), 2025. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social Networks 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabidussi, G. The centrality index of a graph. Psychometrika 1966, 31, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, L.C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, P. Power and centrality: A family of measures. American Journal of Sociology 1987, 92, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özesmi, U.; Özesmi, S.L. Ecological models based on people’s knowledge: a multi-step fuzzy cognitive mapping approach. Ecological Modelling 2004, 176, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P. Centrality and network flow. Social Networks 2005, 27, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).