Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

Data Sources and Assumptions

Estimation Strategy

Results and Discussion

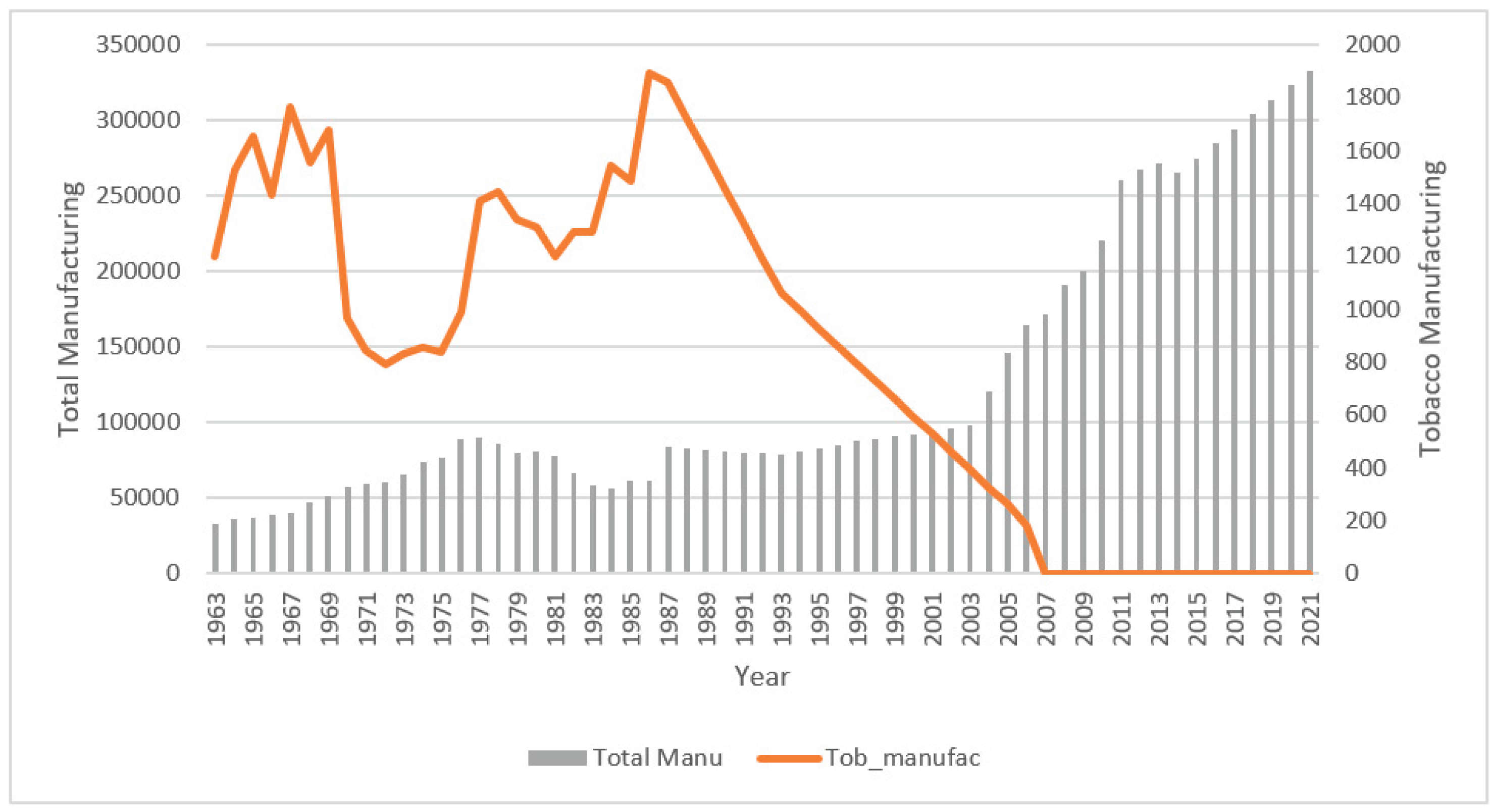

Tobacco Manufacturing Versus Total Manufacturing Jobs

Tobacco Farming or Leaf Production Employment

Tobacco Sales and Distribution Employment

Employment Income

Limitations of the Study

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

| 1 | S – Smuggling & Illicit Trade, C – Court & Legal Challenges, A – Anti-poor Rhetoric R – Revenue Reduction, E – Employment Impact. |

References

- World Health Organization: WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2019: Offer help to quit tobacco use. 2019.

- Goodchild, M.; Nargis, N.; d'Espaignet, E.T. Global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases. Tobacco Control 2018, 27, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The economics of tobacco. [https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/tobacco/publications/the-economics-of-tobacco].

- Ghana Country Facts. [https://files.tobaccoatlas.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/ghana-country-facts-en.pdf].

- Singh, A.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Mdege, N.; McNeill, A.; Britton, J.; Bauld, L. A situational analysis of tobacco control in Ghana: progress, opportunities and challenges. Journal of global health reports 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Investment Case for Tobacco Control in Ghana. In.; 2024.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network: Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Smoking Tobacco Use Prevalence 1990-2019.. In., 2021 edn. Seattle, United States of America: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). 2021.

- CDC; WHO; MOH. GLOBAL YOUTH TOBACCO SURVEY: Factsheet, Ghana 2017. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GLOBAL YOUTH TOBACCO SURVEY, Ghana 2000: Factsheet.

- Yayan, J.; Franke, K.-J.; Biancosino, C.; Rasche, K. Comparative systematic review on the safety of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes. Food Chem Toxicol 2024, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghana Food and Drugs Authority. FDA Strengthens Regulation on Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS)/VAPES; Ghana Food and Drugs Authority: Accra, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Glantz, S.A.; Bareham, D.W. E-cigarettes: use, effects on smoking, risks, and policy implications. Annual review of public health 2018, 39, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, S.L.; Kungskulniti, N.; Charoenca, N.; Kasemsup, V.; Ruangkanchanasetr, S.; Jongkhajornpong, P. Electronic Cigarette Harms: Aggregate Evidence Shows Damage to Biological Systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO framework convention on tobacco control. [ www.who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf (accessed: Jan 28, 2019)].

- Tumwine, J. Implementation of the framework convention on tobacco control in Africa: current status of legislation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2011, 8, 4312–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Economics of Tobacco Control: NCI Monograph Symposium [https://www.economicsforhealth.org/files/research/402/Chaloupka_SRNT_Monograph-Symposium_March-9-2017.pdf].

- Vision for Alternative Development - Ghana (VALD Ghana). The Excise Duty Amendment Act 2023 and the Tobacco Industry Interference in Ghana, VALD Ghana: Accra, 2023.

- Boachie, M.K.; Immurana, M.; Iddrisu, A.-A.; Ayifah, E. Economics of Tobacco Control in Ghana; Vision for Alternative Development: Accra, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Illicit Tobacco Trade [https://www.tobaccotactics.org/article/illicit-tobacco-trade/].

- World Bank. Confronting Illicit Tobacco Trade: a Global Review of Country Experiences; World Bank: Washington DC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vulovic, V. Tobacco Control Policies and Employment. A Tobacconomics Policy Brief; Tobacconomics, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago: Chicago, IL, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.E. The economics of tobacco: myths and realities. Tobacco Control 2000, 9, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatoński, M.Z.; Egbe, C.O.; Robertson, L.; Gilmore, A. Framing the policy debate over tobacco control legislation and tobacco taxation in South Africa. Tobacco Control 2023, 32, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Economics and Business Research Ltd. Quantification of the economic impact of plain packaging for tobacco products in the UK; Centre for Economics and Business Research Ltd: London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Tobacco International. Response to the Department of Health's Consultation on the Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products; Japan Tobacco International: London, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Climate change is smoking Zimbabwe’s valuable tobacco crop. [https://allianceforscience.org/blog/2022/01/climate-change-is-smoking-zimbabwes-valuable-tobacco-crop/].

- Malawi’s Tobacco Sector Standing on One Strong Leg is Better Than on None [https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/505031468757241265/pdf/267380AFR0wp55.pdf].

- Alternatives to tobacco – a closer look at legumes and sunflower in Malawi [https://unfairtobacco.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Legumes-and-Sunflower-in-Malawi_a4.pdf].

- Alternatives to tobacco – a closer look at Kenaf in Malaysia [https://unfairtobacco.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Kenaf-in-Malaysia_en_a4.pdf].

- International Labour Organization. Tobacco sector employment statistical update; International Labour Organization: Geneva, 2014; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, A.; Wiyono, N. An analysis of the impact of higher cigarette prices on employment in Indonesia; University of Indonesia: Indonesia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SP.POP.TOTL&country=SWZ# ].

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. INDSTAT 2 2023, ISIC Revision 3; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wellington, E.; Gyapong, J.; Twum-Barima, S.; Aikins, M.; Britton, J. Tobacco control in Africa: People, politics and policies. Anthem Press: Ghana. London, UK, 2011.

- GlobalData: Cigarettes in Ghana, 2020. In.: GlobalData; 2020.

- Appiah, S.O. Child labour or child work? Children and tobacco production in Gbefi, Volta Region. GHANA SOCIAL SCIENCE 2018, 15, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Quaterly Labour Force Report; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huesca, L.; Sobarzo, H.; Llamas, L. A general equilibrium analysis of the macroeconomic impacts of tobacco taxtation in Mexico In.; 2021.

- Waters, H.; Miera BSd Ross, H.; Shigematsu, L.R. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Taxation in Mexico; International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union): Paris, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Industry Tactics [https://www.tobaccotactics.org/article/tobacco-industry-tactics/].

| Year | Farmers | Distributors | Wholesalers | Retailers | Total |

| 2005 | 1,300 | 250 | 1,800 | 20,000 | 23,350 |

| 2006 | 1,277 | 246 | 1,768 | 19,640 | 22,930 |

| 2007 | 1,254 | 241 | 1,736 | 19,286 | 22,517 |

| 2008 | 1,231 | 237 | 1,705 | 18,939 | 22,112 |

| 2009 | 1,209 | 232 | 1,674 | 18,598 | 21,714 |

| 2010 | 1,187 | 228 | 1,644 | 18,264 | 21,323 |

| 2011 | 1,166 | 224 | 1,614 | 17,935 | 20,939 |

| 2012 | 1,145 | 220 | 1,585 | 17,612 | 20,562 |

| 2013 | 1,124 | 216 | 1,557 | 17,295 | 20,192 |

| 2014 | 1,104 | 212 | 1,529 | 16,984 | 19,829 |

| 2015 | 1,084 | 208 | 1,501 | 16,678 | 19,472 |

| 2016 | 1,065 | 205 | 1,474 | 16,378 | 19,121 |

| 2017 | 1,045 | 201 | 1,447 | 16,083 | 18,777 |

| 2018 | 1,027 | 197 | 1,421 | 15,794 | 18,439 |

| 2019 | 1,008 | 194 | 1,396 | 15,509 | 18,107 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).