Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

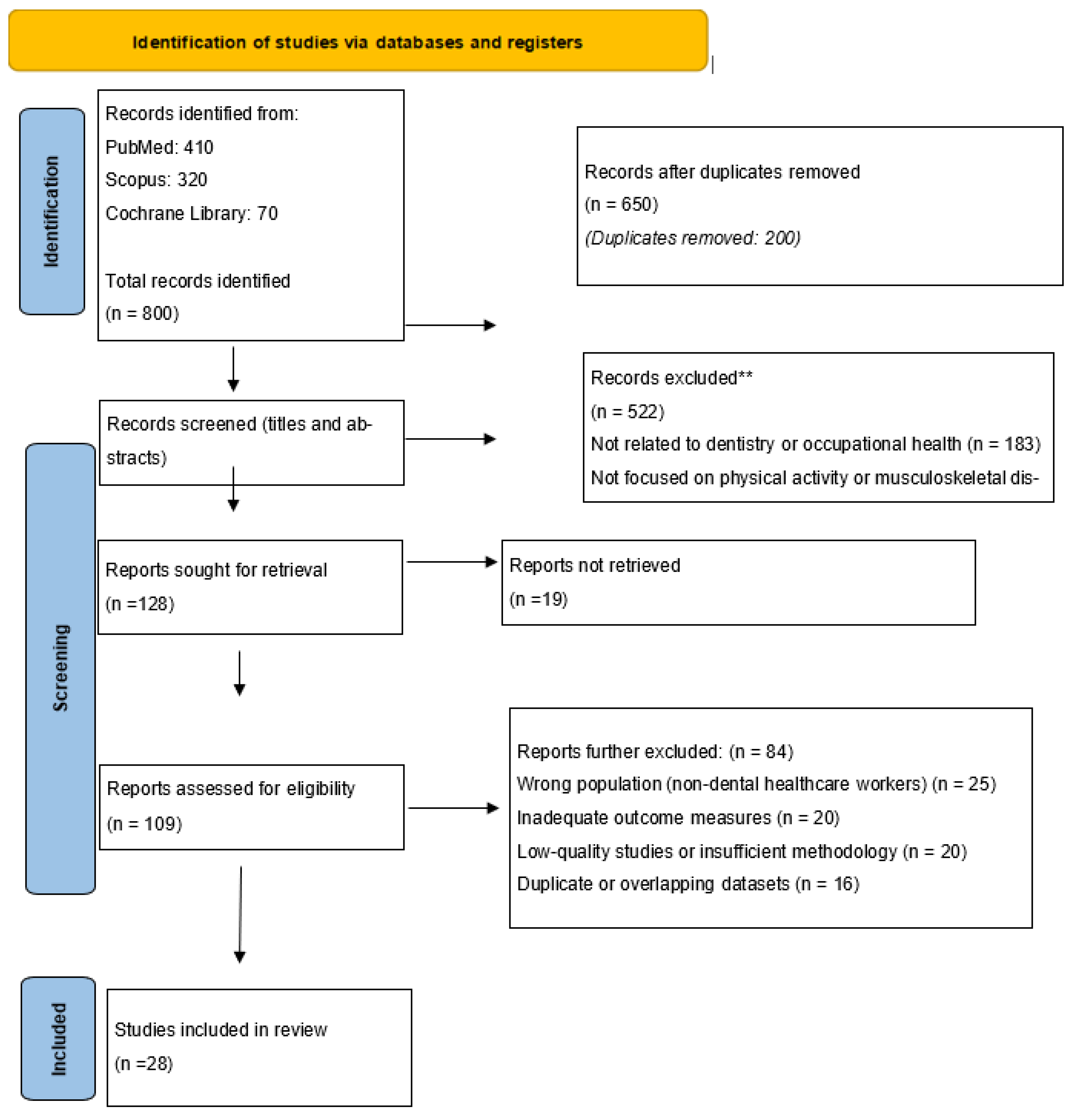

2. Materials and Methods

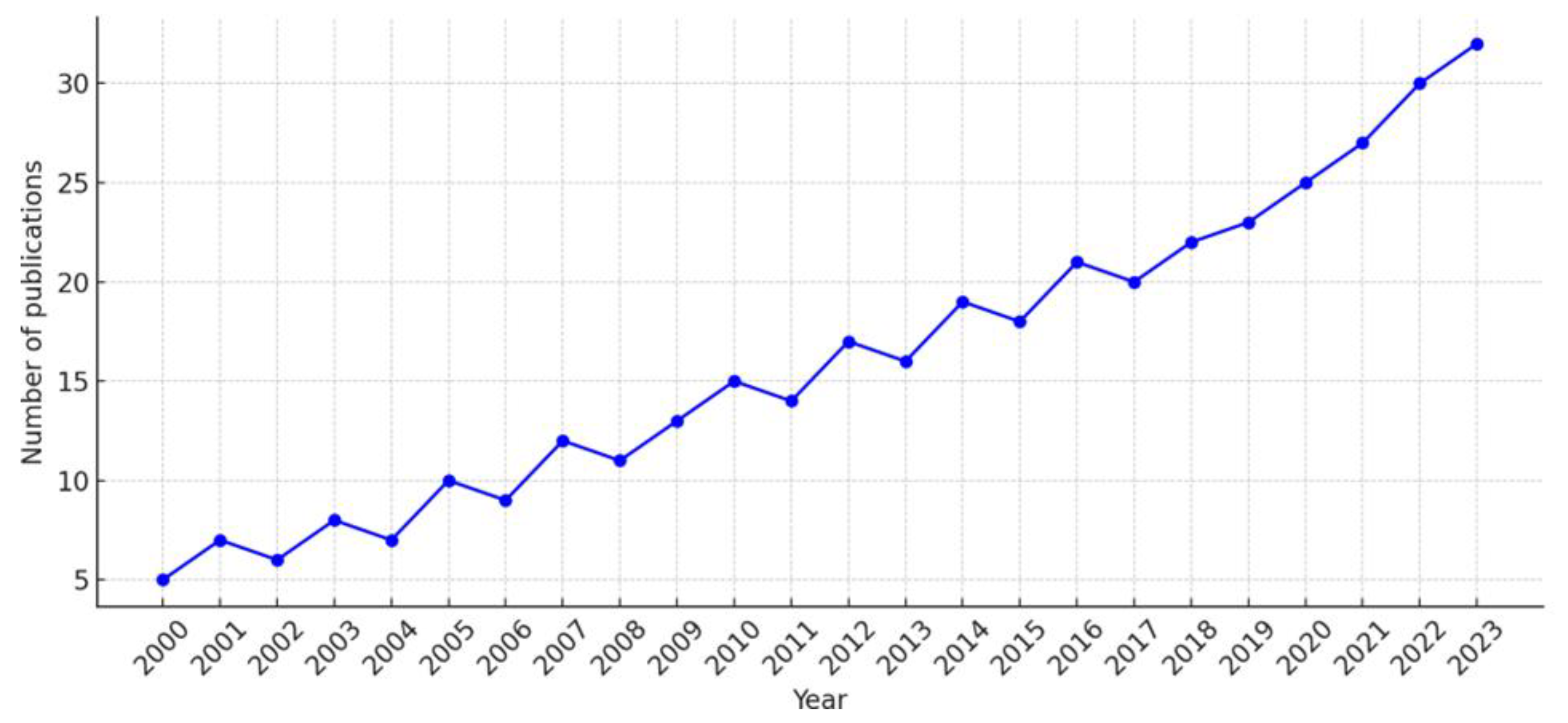

3. Results

4. Discussion

Integrative Models Beyond Ergonomics

Preventive Wellness in Education and Clinical Practice

Institutional and Governmental Responsibility for Health Promotion

Cellular Mechanisms and Biological Aging

Cognitive and Emotional Benefits of Movement

Professional Identity and Role Modeling

The Overlooked Role of Sleep and Recovery

Contextualizing Interventions by Culture and Resources

Long-Term Sustainability of Wellness Practices

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelly D, Shorthouse F, Roffi V, Tack C. Exercise therapy and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in sedentary workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2018;68(4):262–72. [CrossRef]

- Large, A. Managing patient expectations. BDJ Team. 2020;7(9):31. [CrossRef]

- McDonald JM, Paganelli C. Exploration of Mental Readiness for Enhancing Dentistry in an Inter-Professional Climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 1;18(13):7038. [CrossRef]

- Azimi S, Azimi S, Azami M. Occupational hazards/risks among dental staff in Afghanistan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Estimation of factors affecting burnout in Greek dentists before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dent J (Basel). 2022;10(6):108. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M, Mangoulia P, Myrianthefs P. Quality of life and wellbeing parameters of academic dental and nursing personnel vs. quality of services. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(20):2792. [CrossRef]

- Miron C, Colosi HA. Work stress, health behaviours and coping strategies of dentists from Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Int Dent J. 2018;68(3):152–61. [CrossRef]

- Arslan SS, Alemdaroğlu İ, Karaduman AA, Yilmaz ÖT. The effects of physical activity on sleep quality, job satisfaction, and quality of life in office workers. Work. 2019;63(1):3–7. [CrossRef]

- Kurtović A, Talapko J, Bekić S, Škrlec I. The relationship between sleep, chronotype, and dental caries: A narrative review. Clocks Sleep. 2023;5(2):295–312. [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi MG, Zamparini F, Spinelli A, Risi A, Prati C. Musculoskeletal disorders among Italian dentists and dental hygienists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2705. [CrossRef]

- Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Sinha R. The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Med. 2014;44(1):81–121. [CrossRef]

- Serra MVGB, Camargo PR, Zaia JE, Tonello MGM, Quemelo PRV. Effects of physical exercise on musculoskeletal disorders, stress and quality of life in workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2018;24(1):62–7. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez A, Gostian-Ropotin LA, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Belando-Pedreño N, Simón JA, López-Mora C, et al. Sporting mind: The interplay of physical activity and psychological health. Sports (Basel). 2024;12(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Basso JC, Suzuki WA. The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast. 2017;2(2):127–52. [CrossRef]

- Al Nawwar MA, Alraddadi MI, Algethmi RA, Salem GA, Salem MA, Alharbi AA. The Effect of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality and Sleep Disorder: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2023 Aug 16;15(8):e43595. [CrossRef]

- Dhuli K, Naureen Z, Medori MC, Fioretti F, Caruso P, Perrone MA, et al. Physical activity for health. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022;63(2 Suppl 3):E150–9. [CrossRef]

- Militello R, Luti S, Gamberi T, Pellegrino A, Modesti A, Modesti PA. Physical Activity and Oxidative Stress in Aging. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024 ;13(5):557. 1 May. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, J.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, X. Progress in Understanding Oxidative Stress, Aging, and Aging-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burini RC, Anderson E, Durstine JL, Carson JA. Inflammation, physical activity, and chronic disease: An evolutionary perspective. Sports Med Health Sci. 2020 Mar 26;2(1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Cortés, R.; Salazar-Méndez, J.; Nijs, J. Physical Activity as a Central Pillar of Lifestyle Modification in the Management of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Narrative Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, P. , Seing, I., Ericsson, C. et al. Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: an interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 147 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Ara, R.; Afrin, S.; Meiring, J.E.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M. Planetary Health Education and Capacity Building for Healthcare Professionals in a Global Context: Current Opportunities, Gaps and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlgren A, Tucker P, Epstein M, Gustavsson P, Söderström M. Randomised control trial of a proactive intervention supporting recovery in relation to stress and irregular work hours: effects on sleep, burn-out, fatigue and somatic symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2022 Jul;79(7):460-468. [CrossRef]

- Sakzewski L, Naser-ud-Din S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in dentists and orthodontists: A review of the literature. Work. 2014;48(1):37–45. [CrossRef]

- Țâncu AMC, Didilescu AC, Pantea M, Sfeatcu R, Imre M. Aspects regarding sustainability among private dental practitioners from Bucharest, Romania: A pilot study. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(9):1326. [CrossRef]

- Mekhemar M, Attia S, Dörfer C, Conrad J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dentists in Germany. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):1008. [CrossRef]

- Vered Y, Zaken Y, Ovadia-Gonen H, Mann J, Zini A. Professional burnout: Its relevance and implications for the general dental community. Quintessence Int. 2014;45(1):87–90. [CrossRef]

- Plessas A, Paisi M, Bryce M, Burns L, O'Brien T, Hanoch Y, Witton R. Mental health and wellbeing interventions in the dental sector: A systematic review. Evid Based Dent. 2022:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Almeida MB, Póvoa R, Tavares D, Alves PM, Oliveira R. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dental students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023 Sep 11;9(10):e19956. [CrossRef]

- Carapeto PV, Aguayo-Mazzucato C. Effects of exercise on cellular and tissue aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(10):14522–14543. [CrossRef]

- Scott J, Etain B, Miklowitz D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of sleep and circadian rhythms disturbances in individuals at high-risk of developing or with early onset of bipolar disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;135:104585. [CrossRef]

- McDonald JM, Paganelli C. Exploration of Mental Readiness for Enhancing Dentistry in an Inter-Professional Climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 1;18(13):7038. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui FM, Jabeen S, Alwazzan A, Vacca S, Dalal L, Al-Haddad B, Jaber A, Ballout FF, Abou Zeid HK, Haydamous J, El Hajj Chehade R, Kalmatov R. Integration of Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Extended Reality in Healthcare and Medical Education: A Glimpse into the Emerging Horizon in LMICs-A Systematic Review. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2025 ;12:23821205251342315. 29 May. [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, JH. PROSPERO: An international register of systematic review protocols. Med Ref Serv Q. 2019;38(2):171–180. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2022. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics.

- Asaduzzaman M, Arbia L, Tasdika T, Mondol A, Ray P, Hossain T, Hossain M. Assessing the awareness on occupational health hazards among dentists of different private dental clinics in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Biol Agric Healthc. 2022;12(18):xx–xx. [CrossRef]

- Al-Huthaifi BH, Al Moaleem MM, Alwadai GS, Abou Nassar J, Sahli AAA, Khawaji AH, et al. High prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals: A study on ergonomics and workload in Yemen. Med Sci Monit. 2023;29:e942294. [CrossRef]

- Eminoğlu DÖ, Kaşali K, Şeran B, Burmaoğlu GE, Aydin T, Bircan HB. An assessment of musculoskeletal disorders and physical activity levels in dentists: A cross-sectional study. Work. 2025 Jan;80(1):396-406. [CrossRef]

- Al-Emara Z, Karaharju-Suvanto T, Furu P, Furu H. Musculoskeletal disorders and work ability among dentists and dental students in Finland. Work. 2024;78(1):73–81. [CrossRef]

- Matur Z, Zengin T, Bolu NE, Oge AE. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms among young dentists. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43358. [CrossRef]

- Macrì M, Galindo Flores NV, Stefanelli R, Pegreffi F, Festa F. Interpreting the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain impacting Italian and Peruvian dentists likewise: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1090683. [CrossRef]

- Javed H, Tariq H, Lodhi A, Iftikhar R, Khanzada S, Arshad K, et al. Prevalence of carpel tunnel syndrome among dentists: A cross-sectional study. J Health Rehabil Res. 2023;3:384–388. [CrossRef]

- Chenna D, Pentapati KC, Kumar M, Madi M, Siddiq H. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dental healthcare providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res. 2022 Sep 16;11:1062. [CrossRef]

- Daou M, Jaoude SA, Khazaka S. Musculoskeletal disorders in dentists: A preprint. Res Square. 2023. [CrossRef]

- AlDhaen, E. Awareness of occupational health hazards and occupational stress among dental care professionals: Evidence from the GCC region. Front Public Health. 2022;10:922748. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Zhou W, Aisaiti A, Wang B, Zhang J, Svensson P, Wang K. Dentists have a high occupational risk of neck disorders with impact on somatosensory function and neck mobility. J Occup Health. 2021;63(1):e12269. [CrossRef]

- Alnaser MZ, Almaqsied AM, Alshatti SA. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of dentists in Kuwait and the impact on health and economic status. Work. 2021;68(1):213–221. [CrossRef]

- Berdouses EB, Sifakaki M, Katsantoni A, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Greek dentists: A nationwide survey. Dent Res Oral Health. 2020;4:169–182. [CrossRef]

- Savić Pavičin I, Lovrić Ž, Zymber Çeshko A, Vodanović M. Occupational injuries among dentists in Croatia. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2020;54(1):51–59. [CrossRef]

- Alabdulwahab S, Kachanathu S, Alaulami A. Health-related quality of life among dentists in Middle-East countries: A cross-sectional study. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2020;18:168. [CrossRef]

- Harris ML, Sentner SM, Doucette HJ, Brillant MGS. Musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists in Canada. Can J Dent Hyg. 2020;54(2):61–67.

- Ahmad W, Taggart F, Shafique MS, et al. Diet, exercise and mental-wellbeing of healthcare professionals in Pakistan. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1250. [CrossRef]

- Memarpour M, Badakhsh S, Khosroshahi SS, Vossoughi M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Iranian dentists. Work. 2013;45(4):465–474. [CrossRef]

- Hashim R, Al-Ali K. Health of dentists in United Arab Emirates. Int Dent J. 2013;63(1):26–29. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Purohit B. Physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity among Indian dental professionals. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(4):563–570. [CrossRef]

- Ellapen TJ, Narsigan S, van Herdeen HJ, Pillay K, Rugbeer N. Impact of poor dental ergonomical practice. SADJ. 2011;66(6):272–277.

- Sharma P, Golchha V. Awareness among Indian dentists regarding the role of physical activity in prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22(3):381–384. [CrossRef]

- Kierklo A, Kobus A, Jaworska M, Botuliński B. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dentists: A questionnaire survey. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18(1):79–84.

- Lietz J, Kozak A, Nienhaus A. Prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208628. [CrossRef]

- Alhusain FA, Almohrij M, Althukeir F, et al. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms among dentists working in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 2019;39(2):104–111. [CrossRef]

- Mehta A, Gupta M, Upadhyaya N. Status of occupational hazards and their prevention among dental professionals in Chandigarh, India: A comprehensive questionnaire survey. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2013;10(4):446–451.

- Bozkurt S, Demirsoy N, Günendi Z. Risk factors associated with work-related musculoskeletal disorders in dentistry. Clin Investig Med. 2016;39(6):27527.

- Feng B, Liang Q, Wang Y, Andersen LL, Szeto G. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms of the neck and upper extremity among dentists in China. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006451. [CrossRef]

- Meyerson J, Gelkopf M, Eli I, Uziel N. Burnout and professional quality of life among Israeli dentists: The role of sensory processing sensitivity. Int Dent J. 2020;70(1):29–37. [CrossRef]

- Meyerson J, Gelkopf M, Eli I, Uziel N. Stress coping strategies, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction amongst Israeli dentists: A cross-sectional study. Int Dent J. 2022;72(4):476–483. [CrossRef]

- Singh P, Aulak DS, Mangat SS, Aulak MS. Systematic review: Factors contributing to burnout in dentistry. Occup Med (Lond). 2016;66(1):27–31. [CrossRef]

- Szalai E, Hallgató J, Kunovszki P, Tóth Z. Burnout among Hungarian dentists. Orv Hetil. 2021;162(11):419–424. [CrossRef]

- White, R.L. , Vella, S., Biddle, S. et al. Physical activity and mental health: a systematic review and best-evidence synthesis of mediation and moderation studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 21, 134 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Horowitz AM, Fan X, Bieri G, et al. Blood factors transfer beneficial effects of exercise on neurogenesis and cognition to the aged brain. Science. 2020;369(6500):167–173. [CrossRef]

- Reddy V, Bennadi D. Occupational hazards among dentists: A descriptive study. J Oral Hyg Health. 2015;3. [CrossRef]

- Kızılcı E, Kızılay F, Mahyaddinova T, Muhtaroğlu S, Kolçakoğlu K. Stress levels of a group of dentists while providing dental care under clinical, deep sedation, and general anesthesia. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27(7):3601–3609. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R.J. , Ahrens, K.F., Kollmann, B. et al. The impact of physical fitness on resilience to modern life stress and the mediating role of general self-efficacy. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 272, 679–692 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Mulimani P, Hoe VC, Hayes MJ, et al. Ergonomic interventions for preventing musculoskeletal disorders in dental care practitioners. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(10):CD011261. [CrossRef]

- Papagerakis S, Zheng L, Schnell S, et al. The circadian clock in oral health and diseases. J Dent Res. 2014;93(1):27–35. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez de Grado G, Denni J, Musset AM, Offner D. Back pain prevalence, intensity and associated factors in French dentists: A national study among 1004 professionals. Eur Spine J. 2019;28(11):2510–2516. [CrossRef]

- Le VNT, Dang MH, Kim JG, et al. Mental health in dentistry: A global perspective. Int Dent J. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moro JDS, Soares JP, Massignan C, et al. Burnout syndrome among dentists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2022;22(3):101724. [CrossRef]

- Scheepers RA, Emke H, Epstein RM, Lombarts KMJMH. The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on doctors' well-being and performance: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):138–149. [CrossRef]

- Lee CY, Wu JH, Du JK. Work stress and occupational burnout among dental staff in a medical center. J Dent Sci. 2019;14(3):295–301. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030. Geneva: WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484.

- Alyousefy MA, Shaiban AS, Alaajam WH, et al. Questionnaire-based study on the prevalence, awareness, and preventive measures of occupational hazards among dental professionals. Med Sci Monit. 2022;28:e938084. [CrossRef]

- Chen XK, Yi ZN, Wong GT, et al. Is exercise a senolytic medicine? A systematic review. Aging Cell. 2021;20(1):e13294. [CrossRef]

- Zábó V, Lehoczki A, Fekete M, Szappanos Á, Varga P, Moizs M, Giovannetti G, Loscalzo Y, Giannini M, Polidori MC, Busse B, Kellermayer M, Ádány R, Purebl G, Ungvari Z. The role of purpose in life in healthy aging: implications for the Semmelweis Study and the Semmelweis-EUniWell Workplace Health Promotion Model Program. Geroscience. 2025 Jun;47(3):2817-2833. [CrossRef]

- Saintila J, Javier-Aliaga D, Del Carmen Gálvez-Díaz N, Barreto-Espinoza LA, Buenaño-Cervera NA, Calizaya-Milla YE. Association of sleep hygiene knowledge and physical activity with sleep quality in nursing and medical students: a cross-sectional study. Front Sports Act Living. 2025 Mar 20;7:1453404. [CrossRef]

- Praditpapha A, Mattheos N, Pisarnturakit PP, Pimkhaokham A, Subbalekha K. Dentists' Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Int Dent J. 2023 Oct 27;74(2):294–302. [CrossRef]

- Mucharraz y Cano, Yvette, Dávila-Ruiz, Diana, & Cuilty-Esquivel, Karla. (2025). Burnout resilience in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tec Empresarial, 19(1), 36-50. [CrossRef]

- Negucioiu, M.; Buduru, S.; Ghiz, S.; Kui, A.; Șoicu, S.; Buduru, R.; Sava, S. Prevalence and Management of Burnout Among Dental Professionals Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adsett JA, Mudge AM. Interventions to Promote Physical Activity and Reduce Functional Decline in Medical Inpatients: An Umbrella Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2024 Aug;25(8):105052. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher J, Colonio-Salazar F, White S. Supporting dentists' health and wellbeing: A qualitative study of coping strategies in 'normal times'. Br Dent J. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sezer, B. , Sıddıkoğlu, D. Relationship between work-related musculoskeletal symptoms and burnout symptoms among preclinical and clinical dental students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 26, 561 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Leadership and Managerial Skills in Dentistry: Characteristics and Challenges Based on a Preliminary Case Study. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami M, Drouri S, Al Jalil Z, Ettaki S, Jabri M. Musculoskeletal disorders and stress among Moroccan dentists: A cross-sectional study. Integr J Med Sci. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Caron RM, Noel K, Reed RN, Sibel J, Smith HJ. Health Promotion, Health Protection, and Disease Prevention: Challenges and Opportunities in a Dynamic Landscape. AJPM Focus. 2023 Nov 8;3(1):100167. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Chen Y, Shi Y, Su X, Chen P, Wu D, Shi H. Exercise and exerkines: Mechanisms and roles in anti-aging and disease prevention. Experimental Gerontology 2025, 200, 112685. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Englund DA, Aversa Z, Jachim SK, White TA, LeBrasseur NK. Exercise Counters the Age-Related Accumulation of Senescent Cells. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2022 Oct 1;50(4):213-221. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. , Huang, X., Dou, L. et al. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 391 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , Tian, X., Luo, J. et al. Molecular mechanisms of aging and anti-aging strategies. Cell Commun Signal 22, 285 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gao G, Xie Z, Huang H. Mitochondrial function maintenance and mitochondrial training in ageing and related diseases. Journal of Holistic Integrative Pharmacy, 2025, 6, 159–174. [CrossRef]

- Małkowska, P. Positive Effects of Physical Activity on Insulin Signaling. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024 ;46(6):5467-5487. 30 May. [CrossRef]

- Almuraikhy S, Sellami M, Al-Amri HS, Domling A, Althani AA, Elrayess MA. Impact of Moderate Physical Activity on Inflammatory Markers and Telomere Length in Sedentary and Moderately Active Individuals with Varied Insulin Sensitivity. J Inflamm Res. 2023 Nov 20;16:5427-5438. [CrossRef]

- Erickson KI, Hillman C, Stillman CM, Ballard RM, Bloodgood B, Conroy DE, Macko R, Marquez DX, Petruzzello SJ, Powell KE; FOR 2018 PHYSICAL ACTIVITY GUIDELINES ADVISORY COMMITTEE*. Physical Activity, Cognition, and Brain Outcomes: A Review of the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Jun;51(6):1242-1251. [CrossRef]

- Crielaard L, Nicolaou M, Sawyer A, Quax R, Stronks K. Understanding the impact of exposure to adverse socioeconomic conditions on chronic stress from a complexity science perspective. BMC Med. 2021 Oct 12;19(1):242. [CrossRef]

- Belcher BR, Zink J, Azad A, Campbell CE, Chakravartti SP, Herting MM. The Roles of Physical Activity, Exercise, and Fitness in Promoting Resilience During Adolescence: Effects on Mental Well-Being and Brain Development. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021 Feb;6(2):225-237. [CrossRef]

- Dhahbi, W. , Briki, W., Heissel, A. et al. Physical Activity to Counter Age-Related Cognitive Decline: Benefits of Aerobic, Resistance, and Combined Training—A Narrative Review. Sports Med - Open 11, 56 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ben Ezzdine L, Dhahbi W, Dergaa I, Ceylan Hİ, Guelmami N, Ben Saad H, Chamari K, Stefanica V, El Omri A. Physical activity and neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative disorders: a comprehensive review of exercise interventions, cognitive training, and AI applications. Front Neurosci. 2025 Feb 28;19:1502417. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Fernandes MS, Ordônio TF, Santos GCJ, Santos LER, Calazans CT, Gomes DA, Santos TM. Effects of Physical Exercise on Neuroplasticity and Brain Function: A Systematic Review in Human and Animal Studies. Neural Plast. 2020 Dec 14;2020:8856621. [CrossRef]

- Tari A, Norevik C, Scrimgeour, Kobro-Flatmoen A, Storm-Mathisen J, Bergersen L, Wrann CD, Selbæk G, Kivipelto M, MoreiraJBN, Wisløff U. Are the neuroprotective effects of exercise training systemically mediated?Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2019, 62, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Pontes CC, Stanley K, Molayem S. Understanding the Dental Profession's Stress Burden: Prevalence and Implications. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2024 May;45(5):236-241; quiz 242.

- Gkintoni, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Nikolaou, G.; Boutsinas, B. Digital and AI-Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: Neurocognitive Mechanisms and Clinical Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim N, Ka S, Park J. Effects of exercise timing and intensity on physiological circadian rhythm and sleep quality: a systematic review. Phys Act Nutr. 2023 Sep;27(3):52-63. [CrossRef]

- Woo D, Shafiee R, Manton JW, Huang J, Fa BA. Self-care and wellness in dentistry—a mini review. J Oral Maxillofac Anesth 2024;3:5.

- Harris M, Eaton K. Exploring dental professionals' perceptions of resilience to dental environment stress: a qualitative study. Br Dent J. 2025 Mar;238(6):395-402. [CrossRef]

- Koh EYH, Koh KK, Renganathan Y, Krishna L. Role modelling in professional identity formation: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Mar 29;23(1):194. [CrossRef]

- McColl E, Paisi M, Plessas A, Ellwood F, Witton R. An individual-level approach to stress management in dentistry. BDJ Team. 2022;9(10):13–6. [CrossRef]

- de Lisser R, Dietrich MS, Spetz J, Ramanujam R, Lauderdale J, Stolldorf DP. Psychological safety is associated with better work environment and lower levels of clinician burnout. Health Aff Sch. 2024 Jul 17;2(7):qxae091. [CrossRef]

- Teisberg E, Wallace S, O'Hara S. Defining and Implementing Value-Based Health Care: A Strategic Framework. Acad Med. 2020 May;95(5):682-685. [CrossRef]

- Hallman DM, Birk Jørgensen M, Holtermann A. On the health paradox of occupational and leisure-time physical activity using objective measurements: Effects on autonomic imbalance. PLoS One. 2017 ;12(5):e0177042. 4 May. [CrossRef]

- Seaton CL, Bottorff JL, Soprovich AL, et al. Men’s Physical Activity and Sleep Following a Workplace Health Intervention: Findings from the POWERPLAY STEP Up challenge. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2021;15(1). [CrossRef]

- Cillekens B, Huysmans MA, Holtermann A, van Mechelen W, Straker L, Krause N, van der Beek AJ, Coenen P. Physical activity at work may not be health enhancing. A systematic review with meta-analysis on the association between occupational physical activity and cardiovascular disease mortality covering 23 studies with 655 892 participants. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2022 Mar 1;48(2):86-98. [CrossRef]

- Sahebi A, Abdi K, Moayedi S, Torres M, Golitaleb M. The prevalence of insomnia among health care workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. J Psychosom Res. 2021 Oct;149:110597. [CrossRef]

- Karihtala T, Puttonen S, Valtonen AM, Kautiainen H, Hopsu L, Heinonen A. Role of physical activity in the relationship between recovery from work and insomnia among early childhood education and care professionals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2024 Mar 19;14(3):e079746. [CrossRef]

- Marklund S, Mienna CS, Wahlström J, Englund E, Wiesinger B. Work ability and productivity among dentists: associations with musculoskeletal pain, stress, and sleep. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020 Feb;93(2):271-278. [CrossRef]

- Desai D, Momin A, Hirpara P, Jha H, Thaker R, Patel J. Exploring the Role of Circadian Rhythms in Sleep and Recovery: A Review Article. Cureus. 2024 Jun 3;16(6):e61568. [CrossRef]

- Holtermann A, Mathiassen SE, Straker L. Promoting health and physical capacity during productive work: the Goldilocks Principle. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019 Jan 1;45(1):90-97. [CrossRef]

- Cipta DA, Andoko D, Theja A, Utama AVE, Hendrik H, William DG, Reina N, Handoko MT, Lumbuun N. Culturally sensitive patient-centered healthcare: a focus on health behavior modification in low and middle-income nations-insights from Indonesia. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024 Apr 12;11:1353037. [CrossRef]

- Garbin AJÍ, Soares GB, Arcieri RM, Garbin CAS, Siqueira CE. Musculoskeletal disorders and perception of working conditions: A survey of Brazilian dentists in São Paulo. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017;30(3):367–377. [CrossRef]

- Manthey, NA. The role of community-led social infrastructure in disadvantaged areas. Cities 2024, 147, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi A, Cole M, Kelly AL, Zariwala MG, Walker NC. Workplace Physical Activity Barriers and Facilitators: A Qualitative Study Based on Employees Physical Activity Levels. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Aug 1;19(15):9442. [CrossRef]

- Tang T, Nelson M, Steele Gray C. Adapt to evaluate: Lessons from a multi-site trial of a digitally enabled care transition intervention. Healthc Manage Forum. 2025 Jun 23:8404704251351459. [CrossRef]

- Naderbagi A, Loblay V, Zahed IUM, Ekambareshwar M, Poulsen A, Song YJC, Ospina-Pinillos L, Krausz M, Mamdouh Kamel M, Hickie IB, LaMonica HM. Cultural and Contextual Adaptation of Digital Health Interventions: Narrative Review. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Jul 9;26:e55130. [CrossRef]

- Agnello, D.M. , Anand-Kumar, V., An, Q. et al. Co-creation methods for public health research — characteristics, benefits, and challenges: a Health CASCADE scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol 25, 60 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T. Occupational health and hazards among health care workers. Int J Occup Saf Health. 2013;3. [CrossRef]

- Wieneke KC, Egginton JS, Jenkins SM, Kruse GC, Lopez-Jimenez F, Mungo MM, Riley BA, Limburg PJ. Well-Being Champion Impact on Employee Engagement, Staff Satisfaction, and Employee Well-Being. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019 ;3(2):106-115. 27 May. [CrossRef]

- Elsawah, W. Exploring the effectiveness of gamification in adult education: A learner-centric qualitative case study in a dubai training context. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 2025, 9, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowensteyn I, Berberian V, Berger C, Da Costa D, Joseph L, Grover SA. The Sustainability of a Workplace Wellness Program That Incorporates Gamification Principles: Participant Engagement and Health Benefits After 2 Years. Am J Health Promot. 2019 Jul;33(6):850-858. [CrossRef]

- Matthews JA, Matthews S, Faries MD, Wolever RQ. Supporting Sustainable Health Behavior Change: The Whole is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024 ;8(3):263-275. 18 May. [CrossRef]

- AlNujaidi HY, Al-Rayes SA, Alumran A. The Evolution of Wellness Models: Implications for Women's Health and Well-Being. Int J Womens Health. 2025 Mar 4;17:597-613. [CrossRef]

- Kallis G, Hickel J, Daniel W O’Neill DW, Jackson T, Victor AP, Raworth K, Schor JB, Steinberger JK, Ürge-Vorsatz D. Post-growth: the science of wellbeing within planetary boundaries. The Lancet Planetary Health 2025, 9, e62–e78. [CrossRef]

- Huttunen M, Kämppi A, Soudunsaari A, et al. The association between dental caries and physical activity, physical fitness, and background factors among Finnish male conscripts. Odontology. 2023;111(1):192–200. [CrossRef]

- Calvo JM, Kwatra J, Yansane A, et al. Burnout and work engagement among US dentists. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(5):398–404. [CrossRef]

| Authors, country, year | Type of study | Sample | Exposure | Comparators | Statistical significance | Limitations | Sample calculation | Confounders | Outcomes |

| 1. Eminoğlu et al, 2025, Turkey [38]. | Cross-sectional study | 234 dentists (both male and female) | Physical activity levels and presence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) | Dentists with different levels of physical activity (e.g., active vs. inactive) | Significant associations found between lower physical activity levels and higher prevalence of MSDs (p < 0.05) | Cross-sectional design limits causal inference; self-reported data may introduce bias | Not reported | Age, gender, years in practice, and BMI were considered | High prevalence of MSDs among dentists; lower physical activity associated with higher MSD occurrence and intensity |

| 2.Sezer, &, Sıddıkoğlu, 2025, Turkey [30]. | Cross-sectional study | 298 dental students (pre-clinical and clinical phases) | Presence of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms (WMSs) | Students with and without WMSs; comparison also made between pre-clinical and clinical students | Significant positive correlation between musculoskeletal symptoms and burnout symptoms (p < 0.01); clinical students showed higher symptom prevalence | Cross-sectional design limits causal interpretation; self-reported data; single-institution sample may limit generalizability | Not reported | Year of study, gender, and academic workload were considered in analyses | High prevalence of WMSs among dental students, particularly in clinical years; strong association with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization domains of burnout |

| 3. Al-Emara et al, 2024, Finland [39] | Cross-sectional questionnaire-based study - Single-centered |

255 dentists | Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and work ability | descriptive study | MSDs were significantly linked to WAS, FWA, and work disability (p < 0.05). | low response rate (21%), possible self-reporting bias, limited to a single country | 1200 questionnaires sent, with a 21% response rate (255 valid responses) | Age, gender, physical exercise, use of dental loupes | Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders, impact on work ability, sickness absence days |

| 4. Azimi, et al., 2024 Afghanistan [4] |

A cross-sectional study - Single-centered |

206 dentists | physical activity | no | Not highlighted | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Backache was the most common MSD. While 55% were vaccinated, 41.6% were not. Most (74%) found dentistry stressful, and 26.7% reported high end-of-day fatigue. |

| 5.Matur et al., 2023 Turkey [40] | Case-control study - Single-centered |

74 dentists under 40 from Istanbul University Faculty of Dentistry and 61 similarly aged and gender-matched administrative personnel as controls. | prevalence of CTS symptoms | Dentists versus control group | Dentists showed higher CTS symptoms and object dropping, with significant links to BCTQ scores and hand usage duration. | Small sample size, lack of EMG examinations for all participants, potential recall bias for object-dropping incidents, and limited specificity of BCTQ as a screening tool. | Not specified. | Age, sex, BMI, hand usage, and family history of CTS. | 55.4% of dentists reported dropping objects, significantly higher than 19.7% in controls (p<0.001). BCTQ scores were significantly higher in dentists, indicating more severe CTS symptoms and functional impairment. |

| 6.Al-Huthaifi et al., 2023 Yemen , [37] | Cross-sectional questionnaire-based study - Multi-centered (conducted in three dental schools) |

310 dental professionals (174 dental students, 50 interns, 72 general practitioners, 14 specialists) | Musculoskeletal disorders and other occupational hazards | descriptive study | Significant differences found in various parameters, including musculoskeletal problems and needlestick injuries (P<0.05) | Included only one city in Yemen, did not compare different levels of dental clinical professions, did not include auxiliary staff, small sample size | Based on G*Power software, 420 questionnaires distributed, 310 valid responses (response rate: 74%) | Gender, age, clinical profession, levels of awareness about occupational hazards | Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders, awareness of occupational hazards, need for ergonomic education and preventive measures |

| 7.Macrì et al., 2023 Italy and Peru [41] |

Cross-sectional observational study - Multi-centered |

167 dental professionals (86 from Italy and 81 from Peru) | Musculoskeletal pain | descriptive study | Musculoskeletal pain was linked to gender, daily work hours, years of practice, and physical activity. | Small sample size, cross-sectional design, potential cultural differences not fully accounted for, lack of validated questionnaire | 187 questionnaires submitted, 167 valid responses (response rate: ~89%) | Gender, age, occupation, height, working hours, years of work, physical activity, weekly activity, presence of WMSD. | Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain, affected body regions, significant factors associated with pain, need for ergonomic education and intervention |

| 8.Javed, et al., 2023 Pakistan [42] | cross-sectional study - single-centered |

50 dentists, 38% female, aged between 20-50 years. | Neuromuscular Disorders | not specified | Not explicitly stated; however, the study found a higher prevalence of CTS among female dentists. | Small sample size of 50 dentists. | Not specified. | Not detailed | 40% reported mild hand/wrist pain, 10% moderate pain, 30% had daily wrist pain, 40% experienced slight weakness, and 6% moderate weakness. CTS was more prevalent among female dentists. |

| 9.Almeida et al , 2023 Portugal [29]. |

Systematic review and meta-analysis | 29 studies included; total pooled sample size of over 7,000 dental students | Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among dental students | Not applicable (pooled prevalence from included studies) | High pooled prevalence of MSDs among dental students (~74% overall); significant heterogeneity observed among studies (I² > 90%, p < 0.001) | High heterogeneity; variation in methodologies across studies; lack of longitudinal data | Not applicable (systematic review/meta-analysis) | Not analyzed directly due to pooled nature of data; noted variability in assessment tools, gender distribution, and academic stage across studies | High prevalence of MSDs in dental students, particularly in the neck, shoulders, and back; underlines the need for early ergonomic and preventive measures |

| 10.Chenna et al 2022, India [43]. | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 45 studies included (total pooled sample size >12,000 dental healthcare providers) | Occupational risk of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among dental professionals | Not applicable (pooled prevalence estimates from included studies) | Meta-analysis showed a high pooled prevalence of MSDs (overall prevalence ~78%) with significant heterogeneity across studies (I² > 90%, p < 0.001) | High heterogeneity among included studies; variation in MSD definitions and assessment tools; possible publication bias | Not applicable (systematic review/meta-analysis) | Not directly analyzed due to nature of pooled data; most included studies adjusted for age, sex, years of experience where reported | Very high prevalence of MSDs among dental professionals, particularly affecting the neck, back, and shoulders; highlights the need for preventive interventions |

| 11.Daou et al., 2022 Lebanon [44] |

Quantitative research - single-centered |

A total of 314 dentists (184 male and 130 female) | Job satisfaction | tress and satisfaction were linked to leisure, sleep, vacations, relationships, and experience. | Lack of leisure, sleep disorders, fewer vacations, and no outdoor activities were linked to greater psychosocial and patient relationship issues (all P < 0.05). | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | The study found significant stress and job satisfaction issues among Lebanese dentists, recommending sports, cultural activities, better sleep, and mental health programs. |

| 12.Asaduzzaman et al., (2022). Bangladesh [36] | Multi centered, cross-sectional study | 206 professional dentists | occupational physical health | Comparisons based on gender, age, qualification, and occupation | Male SDPs had higher stress scores (P > 0.05), with significantly higher scores in those aged 50+ and at senior levels (P < 0.05). | Self-reported questionnaire could lead to logical bias Cross-sectional study design made it impossible to detect the connection and identify relevant risk factors |

Not specified | Not specified | Only 3.3% saw saliva as a risk. Most used protection; 73.3% noted aerosol risks, 96.7% sterilized tools, 60% felt treatment pain, 70% cited ergonomic risks, 20% were dissatisfied, and 23.3% unaware of technostress. |

| 13.AlDhae, (2022) Bahrain.[45] |

cross-sectional study - multi centered |

222 dental professionals (44.1% male, 55.9% female), aged 23 to 57, with varying physical activity levels. | physical activity | descriptive study | Ergonomic hazards caused the most job stress (25%), followed by biological hazards; physical had less impact, and chemical showed no effect. | The study’s limitations include its Bahrain-specific sample, which limits generalizability, a low response rate, and potential bias due to participation mainly from hazard-aware employees. | Of 300 healthcare workers with over a year of experience, 239 responded, and 222 questionnaires were analyzed. | Not specifically controlled for. | The study confirmed ergonomic, biological, physical, and chemical hazards, with ergonomic hazards most common and the primary cause of increased job-related stress. |

| 14.Zhou et al., 2021 China [46] |

Comparative cross-sectional study - Single-centered |

100 dentists and 102 control aged 22-60 years. | Physical activity,musculoskeletal disorders | Office workers matched by age and gender. | P-values for various tests included, with significant results highlighted. | Limited to Nanjing area; relatively small sample size; cross-sectional design. | Not specified. | Adjusted for working age and gender. | Dentists reported more neck pain (73% vs. 52%) and lower PPTs, indicating higher pain sensitivity. Women had greater CROM and lower PPTs than men. Mobility decreased with age. |

| 15.Gandolfi et al., (2021) Italy [10] |

Cross-sectional observational study - Multi-centered |

284 dental professionals (dentists and dental hygienists) | Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD) | descriptive study | WMSDs were significantly linked to gender, daily/weekly working hours, years of experience, and ergonomic knowledge. | Undisclosed mobilization, potential misinterpretation of activities, inability to link WMSD solely to work, and cross-sectional design limiting causality. | 323 questionnaires distributed, 284 valid responses (response rate: 88%) | Gender, age, body fat, height, occupation, work hours, experience, physical activity, mobilization, ergonomic knowledge. | Prevalence of WMSD, most affected body regions, significant factors associated with WMSD, need for ergonomic education |

| 16. Alnaser, et al., (2021) Kuwait [47] |

cross-sectional multicentered |

232 dentists | Work-related musculoskeletal disorders | Descriptive study | Dentists with WMSD were older, had more experience, and worked longer hours. Pain linked to lost workdays; stress was tied to less sleep, lower job satisfaction, and higher male dissatisfaction. | No specific limitations noted | Not specified | Age | Older dentists, those in practice longer, and those working longer hours were more likely to report work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD). There was a significant association between the rating of pain and lost days from work. |

| 17.Berdouses et al., (2020) Greece [48] |

Cross-sectional - Nationwide survey |

1500 Greek dentists (855 males and 645 females) randomly selected and interviewed over the phone. | Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and their correlation with working conditions | MSD variations were linked to posture, four-handed dentistry, and assistant presence. | Higher MSD prevalence was found in those with over 10 years of work, with distribution varying by posture and four-handed dentistry (p < 0.05). | Subjectivity of responses has potential for more accurate responses from recent episodes, and lack of direct comparison to older studies. | The initial sample included 1968 dentists (1007 males, 961 females); 1500 participated (855 males, 645 females). | Gender, years of practice, method of working (seated vs. standing), and use of four-handed dentistry. | 54.1% reported MSDs, mainly back, hand, cervical, shoulder, and leg problems. Four-handed dentistry and seated posture influenced MSD distribution, while exercise correlated with lower MSD prevalence. |

| 18.Pavičin et al., (2020) Croatia [49] |

Quantitative research Single-centered |

406 dentists in Croatia | Occupational injuries among dentists. | Not applicable. | P-values for various tests included, with significant results highlighted | Limited to dentists in Croatia; relatively small sample size; self-reported data. | Not specified | Adjusted for age, gender, specialization, and years of practice | 63.05% of respondents reported injuries from dental practice, mainly needle punctures (57.75%), cuts (20.86%), and eye injuries (13.37%). Key risk factors include improper posture, stress, infection, and noise. |

| 19.AlAbdulwahab et al., 2020 Saudi Arabia [50] |

Quantitative research, multicentered | Sample of 339 dentists (220 females and 119 males) | musculoskeletal disorders | Yes | Statistical significance highlighted | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | |

| 20.Harris et al., 2020 Canada [51] |

Cross-sectional - multi centered |

647 registered dental hygienists in Canada. | work-related /working hours/physical activity | Not applicable | Positive correlation between years in practice and the number of MSDs reported (r = 0.238; p < 0.001). | Low response rate (2.24%); lacked data on confounders, MSD severity, and work impact. Social media and English-only format skewed responses. | Target sample of 379 ensured 5% margin of error at 95% confidence. | Not specifically controlled for. | 83% reported work-related MSDs, mainly CTS and tendonitis. Incidence rose with years in practice. Half and most schools found prevention training adequate. |

| 21.Miron et al., (2018) Romania. [7] |

Cross-sectional study - Multi-centered |

116 dentists (after excluding inadequately completed questionnaires) from Cluj-Napoca, Romania | Work stress, health behaviors, and coping strategies | descriptive study | Work stress was significantly linked to sociodemographics, health behaviors, and coping strategies. | Low response rate, potential information bias, overrepresentation of young dentists and those who teach at the university, limited generalizability to older age groups | Sample size set at 148; 250 questionnaires distributed to offset low response rate. | Factors included age, workplaces, work hours, job satisfaction, exercise, nutrition, and work-related pain. | Overall work stress scores, predictors of work stress, health behaviors, coping strategies, self-perceived health |

| 22.Ahmad et al., 2015 Pakistan [52]. |

Cross-sectional study - Multi-centered |

1,190 healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, dentists) | Diet, exercise, mental well-being | No | Found significant (p<0.05) | Non-probability sampling, lack of detailed dietary guidelines for Pakistan, self-reported BMI, and subjective occupational stress assessment. | Followed sample size recommendations by VanVoorhis & Morgan (2007) | Gender, age, income, profession, psychosocial stressors, dietary habits | Low prevalence of regular exercise, high levels of occupational stress, moderate levels of mental well-being, dietary patterns not meeting recommended guidelines |

| 23.Memarpour et al., (2013) Iran, United Arab Emirates [53] |

Cross-sectional study Single centered |

272 dentists (205 generalists and 67 specialists) | Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) | No | Found significant (p<0.05) | Not specified | Not specified | Gender, years of work, ergonomic exercise | High prevalence of MSDs, especially in shoulder, neck, and lower back; significant correlation with years of work and ergonomic exercise |

| 24.Hashim & Al-Ali (2013) Dubai, Iran, United Arab Emirates[54]. |

Cross-sectional study Single centered |

733 dentists aged 22-70 years, both male and female, from public and private sectors | Health problems, exercise habits, smoking habits, systemic diseases | No | Found significant (P < 0.05) | Potential inaccuracies in self-reported data | Not specified | Gender, work sector (public vs. private), smoking habits | Low prevalence of regular exercise, significant smoking habits, systemic health problems including cardiovascular diseases |

| 25.Singh & Purohit (2012) India [55] |

Cross-sectional study - single centered |

324 dental health care professionals | Physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity | No | Found significant (P ≤ .05 for physical activity, P ≤ .001 for obesity) | Not specified | Not specified | Assessment of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and obesity in dental professionals | Physical activity levels (mean MET minutes/week) varied significantly, with students and interns being more active than faculty, who also had the highest obesity rates. These differences were statistically significant. |

| 26.Ellapen et al., (2011) South Africa [56] |

Occupational, epidemiological retrospective study -Single centered |

94 dentists aged 24-75 years old | Poor dental ergonomical practice | No | Found significant (p<0.05) | Lack of radiographs and posture profiles | Not specified | Gender, race, and BMI | Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and discomfort in different body parts |

| 27.Sharma & Golchha (2011) India [57] |

Questionaire survey single centered |

102 Indian dentists (80 males) from Delhi NCR with recent MSDs; 220 dentists (194 females) from Podlaskie Voivodeship. | Physical activity's role in preventing work-related MSDs. | No | Found significant correlation using Pearson correlation test | Not specified | Not specified | Gender, duration of work, and ergonomic factors | Awareness of physical activity's role in prevention, correlation between physical activity sessions and symptom improvement |

| 28.Kierklo et al., (2011) Poland[58] |

Questionaire survey Single centered |

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) | No | Found significant (p<0.05) | No correlation between work and MSDs, except in specific cases; reliance on self-reported data. | Not specified | Gender, years of practice, work posture, and rest breaks. | High prevalence of MSDs, especially in neck and lower back, correlation between years of practice and MSD occurrence |

| Sensitivity Condition | Impact on Findings | Effect Description |

| Exclusion of small sample studies (<100 participants) | Low to moderate | Trends remain consistent, minor statistical shifts |

| Inclusion of studies with standardized MSD diagnostics only | Minimal | Findings confirm reliability across consistent diagnostics |

| Exclusion of studies from LMICs | Moderate to high | Contextual insights reduced, skew toward high-income settings |

| Inclusion of studies specifying sector (public/private) | Significant (data reduction) | Weaker conclusions due to limited data |

| Inclusion of studies published after 2020 only | Shift in thematic focus (less emphasis on MSDs) | More focus on mental health; traditional MSD patterns diluted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).