Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

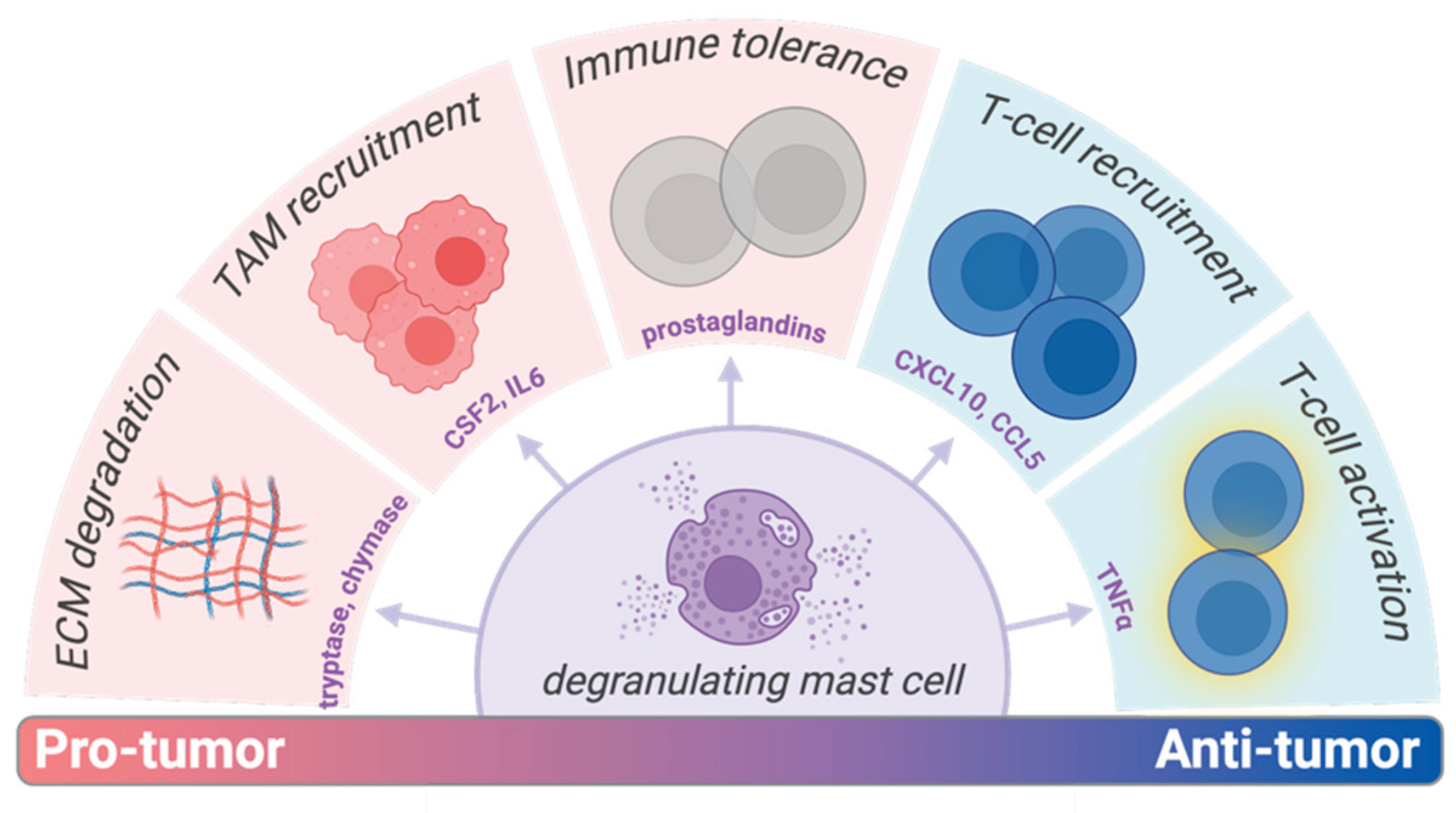

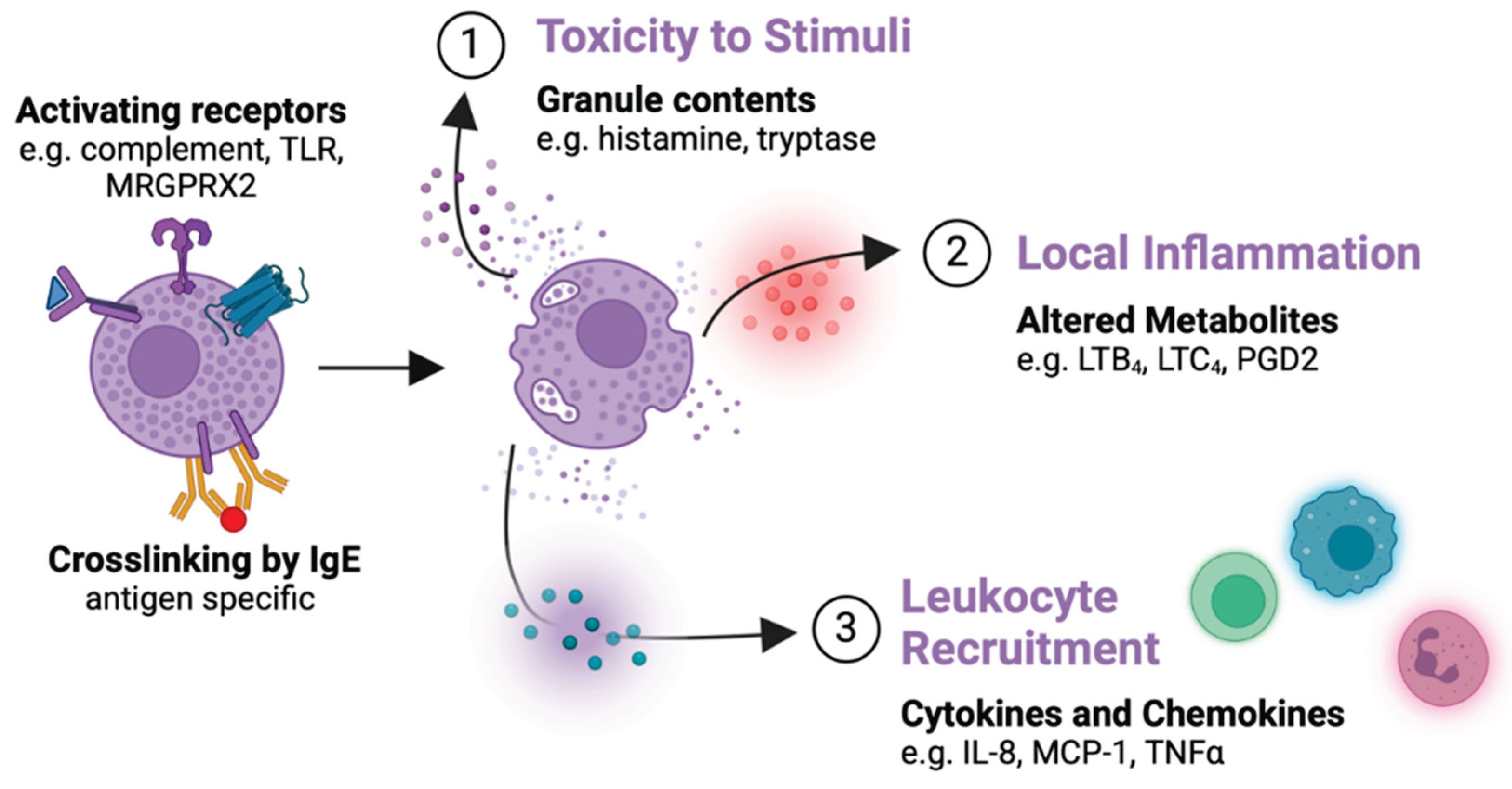

2. Modulating MC Activation as Cancer Immunotherapy

2.1. Direct Effects of MC Modulators on Cancer Cells

2.2. Inhibition of MC Function as Cancer Immunotherapy

| MC AGONIST | CANCER | IN VIVO MODEL | DOSE | DOSING | CONCLUSIONS | REF | |

| Cromolyn sodium | Thyroid | 8505-C subQ in BALB/c-nu | IP 10 mg/kg | qd | Co-injection of MCs with tumor resulted in accelerated tumor growth, treatment with cromolyn reversed this | [12] | |

| Pancreatic | pIns-mycERTAM;RIP7-bcl-xL transgenic | IP 10 mg/kg | qd | Induced apoptosis of pre-existing β-cell tumors; MCs critical for tumor expansion | [101] | ||

| Colon | CT-26 subQ in BALB/c | IP 50 mg/kg | q2d | Non-significant reduction in tumor weight and after survival change | [72] | ||

| Mastoparan | Melanoma | B16F10-Nex2 subQ in C57BL/6 | Peritumoral 5 mg/kg |

qd 5x | 70.29% growth inhibition rate 28.26% prolonged survival ratio |

[73] | |

| Breast | 4T1 orthotopic in BALB/c | IP 6 mg/kg | q2d | Non-significant reduction in tumor growth. significant reduction when combined with gemcitabine |

[68] | ||

| MCF-7/Dox in BALB/c-nu | IV 10 μmol/kg | q2d 7x | 33.6% growth inhibition rate | No signs of damage by histology or blood chemistry | [52] | ||

| KM8 | 81.6% growth inhibition rate | ||||||

2.3. Activation of MCs as Cancer Immunotherapy

3. Formulation of MC Modulators in Drug Delivery Systems

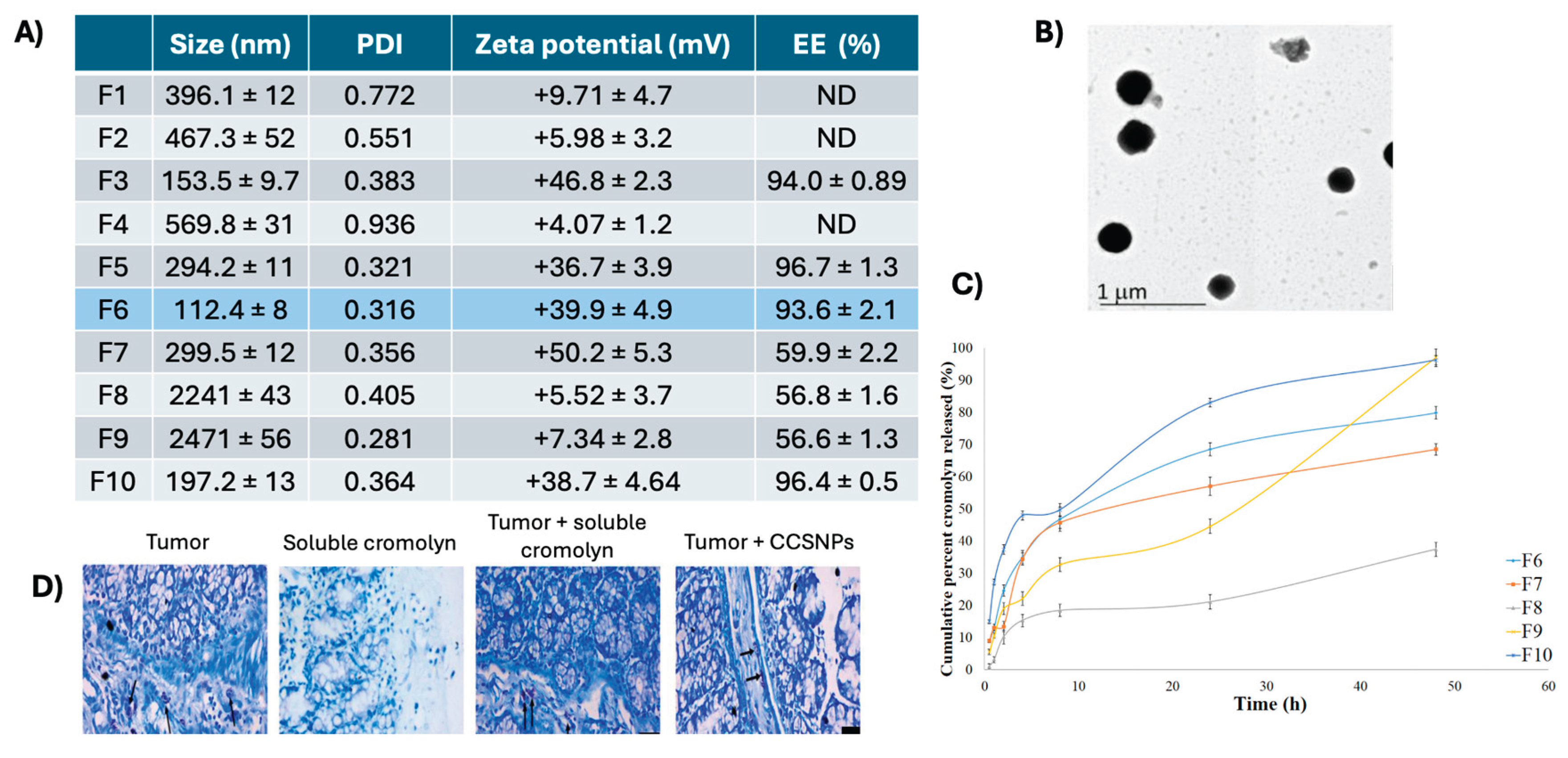

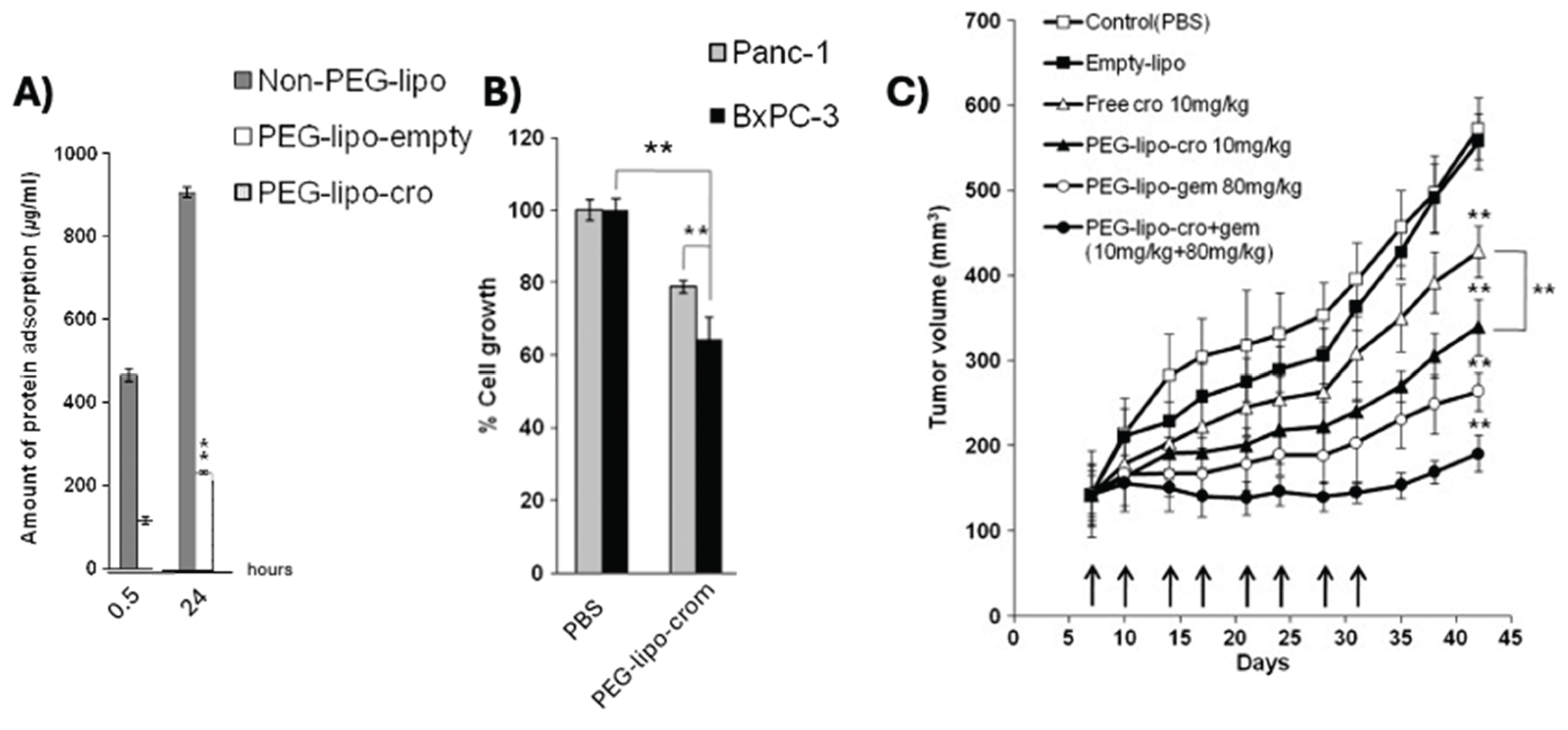

3.1. Cromolyn Formulations for MC Inhibition

3.2. Mastoparan Nanoconjugates

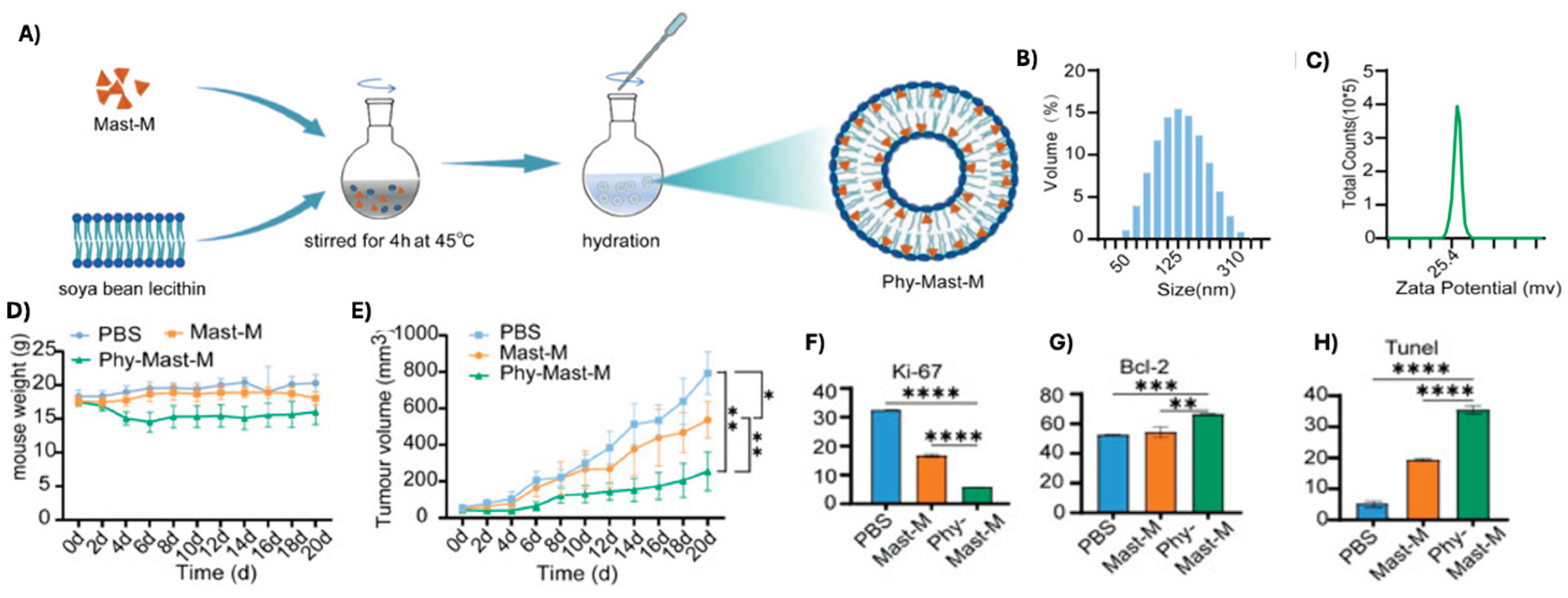

3.3. Phytosome Encapsulation of Mastoparan

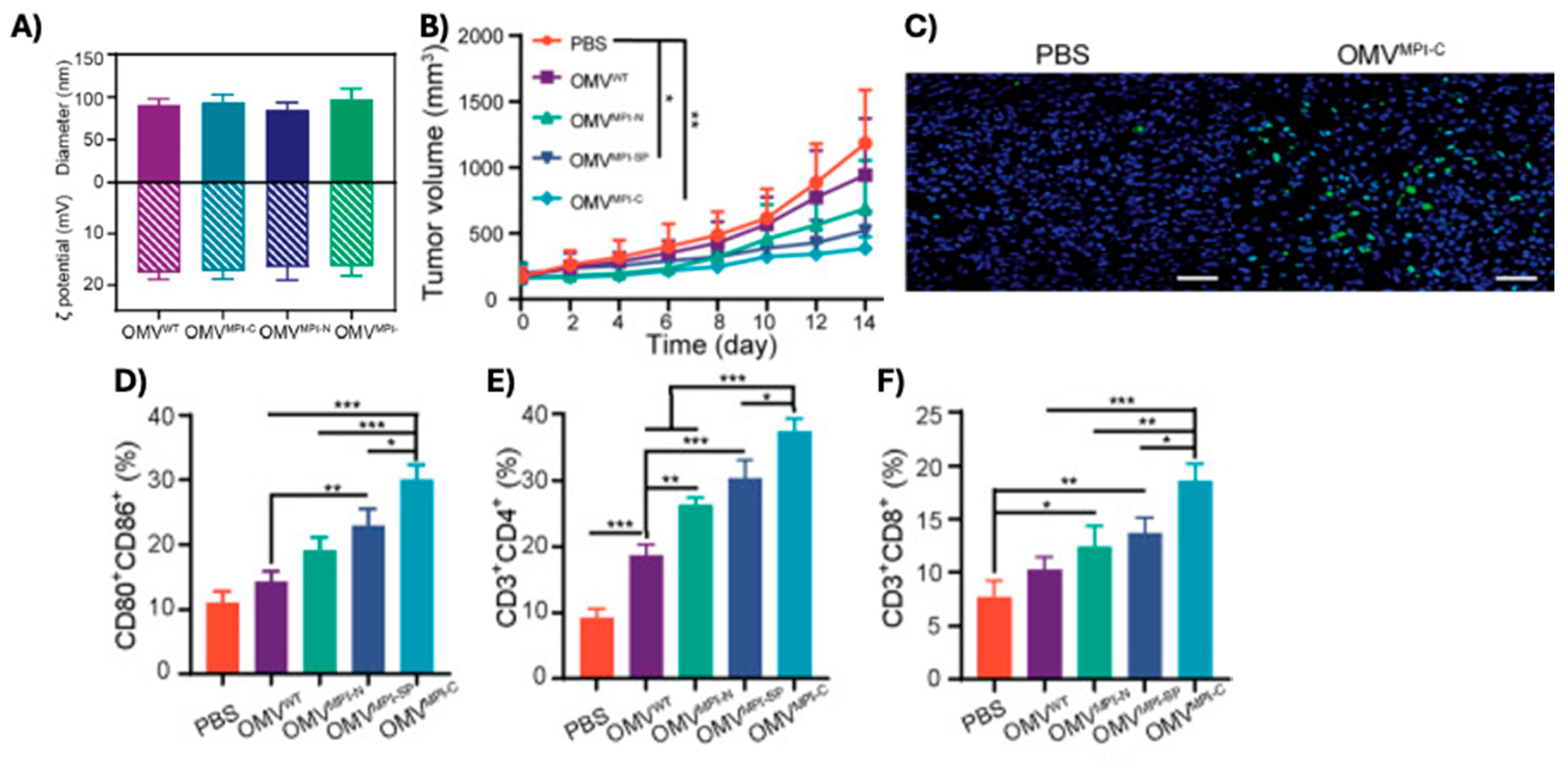

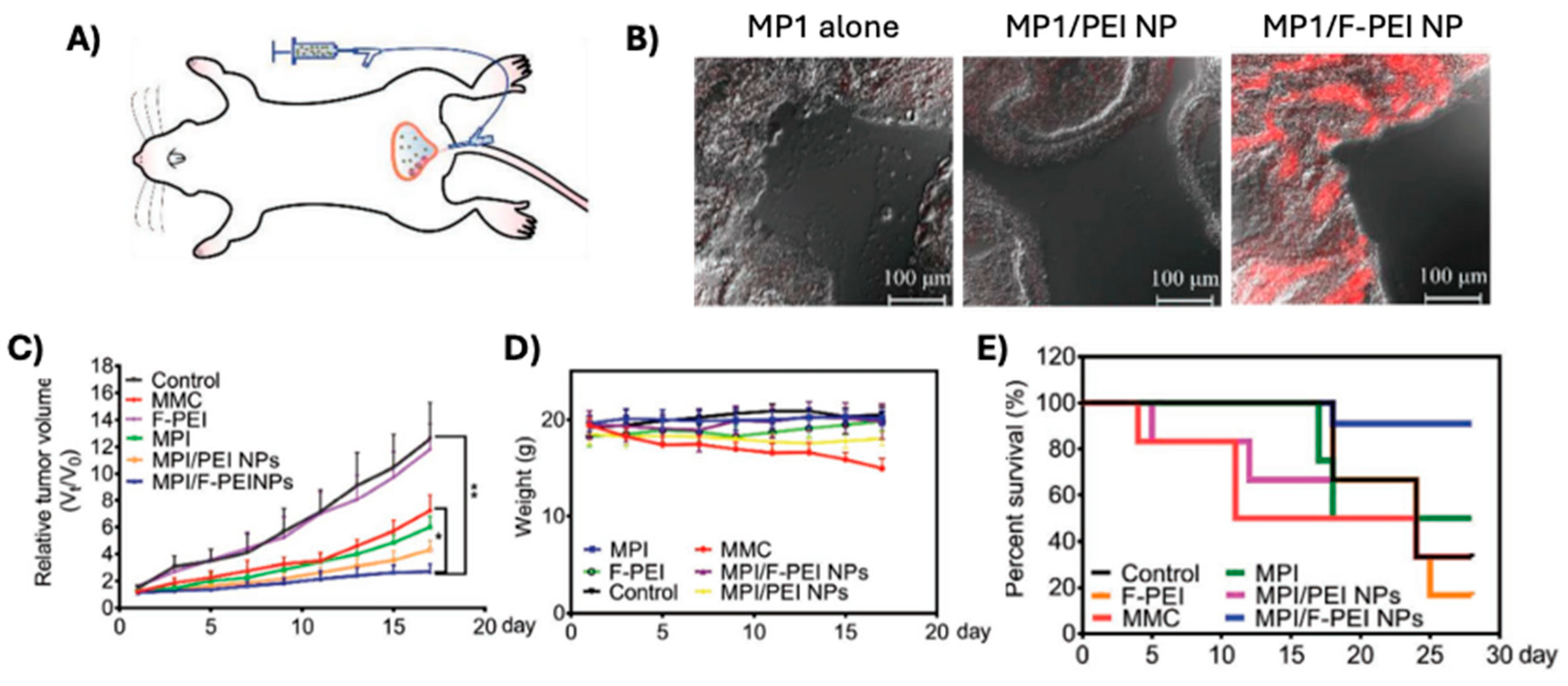

3.4. Polybia-MP1 Nanoparticle Formulations

3.5. Micellular Polymyxin E Co-Delivered with Doxorubicin

4. Conclusions

References

- Flier, J.S.; Underhill, L.H.; Galli, S.J. New Concepts about the Mast Cell. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Pang, X.; Letourneau, R.; Sant, G.R. Interstitial Cystitis: A Neuroimmunoendocrine Disordera. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1998, 840, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedström, G.; Berglund, M.; Molin, D.; Fischer, M.; Nilsson, G.; Thunberg, U.; Book, M.; Sundström, C.; Rosenquist, R.; Roos, G.; et al. Mast cell infiltration is a favourable prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2007, 138, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.K.; Magistris, A.; Loizzi, V.; Lin, F.; Rutgers, J.; Osann, K.; DiSaia, P.J.; Samoszuk, M. Mast cell density, angiogenesis, blood clotting, and prognosis in women with advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 99, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Wu, W.; Liu, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, X.; Luo, P.; et al. Large-scale bulk RNA-seq analysis defines immune evasion mechanism related to mast cell in gliomas. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 914001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulubova, M.; Vlaykova, T. Prognostic significance of mast cell number and microvascular density for the survival of patients with primary colorectal cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.M.; Zheng, D.B.; Hu, D.M.; Ma, B.M.; Cai, C.M.; Chen, W.M.; Zeng, J.M.; Luo, J.M.; Xiao, D.M.; Zhao, Y.M.; et al. The prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophages in glioma patients. Medicine 2023, 102, e35298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Niu, L.; Zheng, G.; Du, K.; Dai, S.; Li, R.; Dan, H.; Duan, L.; Wu, H.; Ren, G.; et al. Single-cell analysis unveils activation of mast cells in colorectal cancer microenvironment. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, L.; Liao, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Rao, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Mast cells expressing interleukin 17 in the muscularis propria predict a favorable prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2013, 62, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shen, W.; Sun, M.; Lv, J.; Liu, R.; Qin, S. Activated Mast Cells Combined with NRF2 Predict Prognosis for Esophageal Cancer. J. Oncol. 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, G.; Guarnotta, C.; Frossi, B.; Piccaluga, P.P.; Boveri, E.; Gulino, A.; Fuligni, F.; Rigoni, A.; Porcasi, R.; Buffa, S.; et al. Bone marrow stroma CD40 expression correlates with inflammatory mast cell infiltration and disease progression in splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Blood 2014, 123, 1836–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melillo, R.M.; Guarino, V.; Avilla, E.; Galdiero, M.R.; Liotti, F.; Prevete, N.; Rossi, F.W.; Basolo, F.; Ugolini, C.; de Paulis, A.; et al. Mast cells have a protumorigenic role in human thyroid cancer. Oncogene 2010, 29, 6203–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, D.; Edström, A.; Glimelius, I.; Glimelius, B.; Nilsson, G.; Sundström, C.; Enblad, G. Mast cell infiltration correlates with poor prognosis in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2002, 119, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Ennas, M.G.; Vacca, A.; Ferreli, F.; Nico, B.; Orru, S.; Sirigu, P. Tumor vascularity and tryptase-positive mast cells correlate with a poor prognosis in melanoma. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 33, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskinen, M.; Karjalainen-Lindsberg, M.-L.; Leppä, S. Prognostic influence of tumor-infiltrating mast cells in patients with follicular lymphoma treated with rituximab and CHOP. Blood 2008, 111, 4664–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, H.; Kinuta, M.; Tateishi, H.; Nakano, Y.; Matsui, S.; Monden, T.; Okamura, J.; Sakai, M.; Okamoto, S. Mast cell infiltration around gastric cancer cells correlates with tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Gastric Cancer 1999, 2, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A.; Rudolfsson, S.; Hammarsten, P.; Halin, S.; Pietras, K.; Jones, J.; Stattin, P.; Egevad, L.; Granfors, T.; Wikström, P.; et al. Mast Cells Are Novel Independent Prognostic Markers in Prostate Cancer and Represent a Target for Therapy. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majorini, M.T.; Colombo, M.P.; Lecis, D. Few, but Efficient: The Role of Mast Cells in Breast Cancer and Other Solid Tumors. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.M.; Reuben, A.; Barua, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Hudgens, C.W.; Tetzlaff, M.T.; Reuben, J.M.; et al. Poor Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Correlates with Mast Cell Infiltration in Inflammatory Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Annese, T.; Tamma, R. Controversial role of mast cells in breast cancer tumor progression and angiogenesis. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.; Kinet, J.-P. Signalling through the high-affinity IgE receptor FcεRI. Nature 1999, 402, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülen, T.; Akin, C. Anaphylaxis and Mast Cell Disorders. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2022, 42, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.D. Prussin, and D.D. Metcalfe, IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2010. 125(2 SUPPL. 2): p. S73-S80.

- Yu, Y.; Blokhuis, B.R.; Garssen, J.; Redegeld, F.A. Non-IgE mediated mast cell activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 778, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystel-Whittemore, M.; Dileepan, K.N.; Wood, J.G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, S.J.; Nakae, S.; Tsai, M. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, J.B.; Hart, J.P.; Pizzo, S.V.; Shelburne, C.P.; Staats, H.F.; Gunn, M.D.; Abraham, S.N. Mast cell–derived tumor necrosis factor induces hypertrophy of draining lymph nodes during infection. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakae, S.; Suto, H.; Iikura, M.; Kakurai, M.; Sedgwick, J.D.; Tsai, M.; Galli, S.J. Mast Cells Enhance T Cell Activation: Importance of Mast Cell Costimulatory Molecules and Secreted TNF. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2238–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, K.M.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Pfaff, D.W.; Silver, R. Brain mast cells link the immune system to anxiety-like behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 18053–18057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurish, M.F.; Austen, K.F. Developmental Origin and Functional Specialization of Mast Cell Subsets. Immunity 2012, 37, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.F.; Barrett, N.A.; Austen, K.F.; The Immunological Genome Project Consortium. Expression profiling of constitutive mast cells reveals a unique identity within the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, H.R.; Stevens, R.L.; Austen, K. Heterogeneity of mammalian mast cells differentiated in vivo and in vitro. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1985, 76, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Austen, K.F.; Gurish, M.F.; Jones, T.G. Protease phenotype of constitutive connective tissue and of induced mucosal mast cells in mice is regulated by the tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 14210–14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswamy, G., O. Ajitawi, and D.S. Chi, The human mast cell: an overview. Mast Cells: Methods and Protocols, 2005: p. 13-34.

- Khazaie, K.; Blatner, N.R.; Khan, M.W.; Gounari, F.; Gounaris, E.; Dennis, K.; Bonertz, A.; Tsai, F.-N.; Strouch, M.J.T.; Cheon, E.; et al. The significant role of mast cells in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011, 30, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligan, C. , et al., The regulatory role and mechanism of mast cells in tumor microenvironment. American Journal of Cancer Research, 2024. 14(1): p. 1-1.

- Huang, B.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, G.-M.; Li, D.; Song, C.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Unkeless, J.; Xiong, H.; et al. SCF-mediated mast cell infiltration and activation exacerbate the inflammation and immunosuppression in tumor microenvironment. Blood 2008, 112, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, E.; Everingham, S.; Zhang, S.; Greer, P.A.; Allingham, J.S.; Craig, A.W. FES Kinase Promotes Mast Cell Recruitment to Mammary Tumors via the Stem Cell Factor/KIT Receptor Signaling Axis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Põlajeva, J.; Sjösten, A.M.; Lager, N.; Kastemar, M.; Waern, I.; Alafuzoff, I.; Smits, A.; Westermark, B.; Pejler, G.; Uhrbom, L.; et al. Mast Cell Accumulation in Glioblastoma with a Potential Role for Stem Cell Factor and Chemokine CXCL12. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e25222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.L. , et al., Arthritis augments breast cancer metastasis: role of mast cells and SCF/c-Kit signaling. Breast Cancer Research, 2013. 15(2): p. R32.

- Ma, Y.; Hwang, R.F.; Logsdon, C.D.; Ullrich, S.E. Dynamic Mast Cell–Stromal Cell Interactions Promote Growth of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3927–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-Q.; Lv, J.-Q.; Lin, Y.; Xiang, M.; Gao, B.-H.; Shi, Y.-F. Expression of chemokines CCL5 and CCL11 by smooth muscle tumor cells of the uterus and its possible role in the recruitment of mast cells. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. , et al., Expression of CCL5/RANTES by Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells and its possible role in the recruitment of mast cells into lymphomatous tissue. International Journal of Cancer, 2003. 107(2): p. 197-201.

- Oldford, S.A.; Marshall, J.S. Mast cell modulation of the tumor microenvironment. The Tumor Immunoenvironment, 2013: p.

- Varricchi, G. , et al., Future Needs in Mast Cell Biology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, Vol. 20, Page 4397, 2019. 20(18): p. 4397-4397.

- Varricchi, G. , et al., Are Mast Cells MASTers in Cancer? Frontiers in Immunology, 2017. 8.

- Grützkau, A.; Krüger-Krasagakes, S.; Baumeister, H.; Schwarz, C.; Kögel, H.; Welker, P.; Lippert, U.; Henz, B.M.; Möller, A. Synthesis, Storage, and Release of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor/Vascular Permeability Factor (VEGF/VPF) by Human Mast Cells: Implications for the Biological Significance of VEGF206. Mol. Biol. Cell 1998, 9, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, O.N.; Torres, M.D.T.; Cao, J.; Alves, E.S.F.; Rodrigues, L.V.; Resende, J.M.; Lião, L.M.; Porto, W.F.; Fensterseifer, I.C.M.; Lu, T.K.; et al. Repurposing a peptide toxin from wasp venom into antiinfectives with dual antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 26936–26945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, R.J. , et al., Side Chain Hydrophobicity Modulates Therapeutic Activity and Membrane Selectivity of Antimicrobial Peptide Mastoparan-X. PLoS ONE, 2014. 9(3): p. e91007.

- Souza, B.M.; Mendes, M.A.; Santos, L.D.; Marques, M.R.; César, L.M.; Almeida, R.N.; Pagnocca, F.C.; Konno, K.; Palma, M.S. Structural and functional characterization of two novel peptide toxins isolated from the venom of the social wasp Polybia paulista. Peptides 2005, 26, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiolas, A.; Pisano, J.J. Isolation and characterization of two new peptides, mastoparan C and crabrolin, from the venom of the European hornet, Vespa crabro. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 10106–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Xing, Z.; Zhong, H.; Yu, D.; Yu, R.; Deng, X. Plasma metabolites-based design of long-acting peptides and their anticancer evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 631, 122483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irazazabal, L.N.; Porto, W.F.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Casale, S.; Humblot, V.; Ladram, A.; Franco, O.L. Selective amino acid substitution reduces cytotoxicity of the antimicrobial peptide mastoparan. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynor, R.L.; Kim, Y.-S.; Zheng, B.; Vogler, W.R.; Kuo, J. Membrane interactions of mastoparan analogues related to their differential effects on protein kinase C, Na,K-ATPase and HL60 cells. FEBS Lett. 1992, 307, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.R. , et al., The Heterotrimeric G-protein Gi Is Localized to the Insulin Secretory Granules of β-Cells and Is Involved in Insulin Exocytosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1995. 270(21): p. 12869-12876.

- Ontiveros-Padilla, L.; Hendy, D.A.; Pena, E.S.; Williamson, G.L.; Murphy, C.T.; Lukesh, N.R.; Ashcraft, K.A.; Abraham, M.A.; Landon, C.D.; Staats, H.F.; et al. Broadly active intranasal influenza vaccine with a nanocomplex particulate adjuvant targeting mast cells and toll-like receptor 9. J. Control. Release 2025, 384, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, J.B.; Shelburne, C.P.; Hart, J.P.; Pizzo, S.V.; Goyal, R.; Brooking-Dixon, R.; Staats, H.F.; Abraham, S.N. Mast cell activators: a new class of highly effective vaccine adjuvants. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovnik, L., M. Logonder-Mlinsek, and F. Erjavec, The effect of compound 48/80 and of electrical field stimulation on mast cells in the isolated mouse stomach. Agents Actions, 1988. 23(3-4): p. 300-3.

- Koibuchi, Y. , et al., Binding of active components of compound 48/80 to rat peritoneal mast cells. Eur J Pharmacol, 1985. 115(2-3): p. 171-7.

- Murphy CT, B. EM, and A. KM, Mast Cell Activators as Adjuvants in Mucosal Vaccines. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, In press.

- Schemann, M. , et al., The mast cell degranulator compound 48/80 directly activates neurons. PLoS One, 2012. 7(12): p. e52104.

- John, A.L.S.; Choi, H.W.; Walker, Q.D.; Blough, B.; Kuhn, C.M.; Abraham, S.N.; Staats, H.F. Novel mucosal adjuvant, mastoparan-7, improves cocaine vaccine efficacy. npj Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H.V.; Johnson, A.R.; Moran, N.C. SELECTIVE RELEASE OF HISTAMINE FROM RAT MAST CELLS BY SEVERAL DRUGS. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1970, 175, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratories, B. , Polymyxin B for Injection USP 500,000 units. 2011: Product Insert.

- Yoshino, N.; Endo, M.; Kanno, H.; Matsukawa, N.; Tsutsumi, R.; Takeshita, R.; Sato, S.; Miyaji, E.N. Polymyxins as Novel and Safe Mucosal Adjuvants to Induce Humoral Immune Responses in Mice. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, M.C.; van Velzen, A.J.; Touw, D.J.; de Kok, B.M.; Fokkens, W.J.; Heijerman, H.G.M. Systemic absorption of nasally administered tobramycin and colistin in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 3112–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.-X.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Qu, J.-M. Intravenous combined with aerosolised polymyxin versus intravenous polymyxin alone in the treatment of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilchie, A.L.; Sharon, A.J.; Haney, E.F.; Hoskin, D.W.; Bally, M.B.; Franco, O.L.; Corcoran, J.A.; Hancock, R.E. Mastoparan is a membranolytic anti-cancer peptide that works synergistically with gemcitabine in a mouse model of mammary carcinoma. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 3195–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, S.S.; Fernandopulle, N.A.; Karas, J.A.; Li, J.; Ziogas, J.; Velkov, T.; Mackay, G.A. Differential MRGPRX2-dependent activation of human mast cells by polymyxins and octapeptins. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 984, 177050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, X.; Brehin, S.; Kamel, R.; Landry, Y. G protein-dependent activation of mast cell by peptides and basic secretagogues. Peptides 2002, 23, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousli, M.; Bueb, J.-L.; Bronner, C.; Rouot, B.; Landry, Y. G protein activation: a receptor-independent mode of action for cationic amphiphilic neuropeptides and venom peptides. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990, 11, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, A.; Haghshenas, M.R.; Kiani, R.; Panjehshahin, M.R.; Erfani, N. Promising anticancer activity of cromolyn in colon cancer: in vitro and in vivo analysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, R.A. , et al., Mastoparan induces apoptosis in B16F10-Nex2 melanoma cells via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway and displays antitumor activity in vivo. Peptides, 2015. 68: p. 113-119.

- Alhakamy, N.A.; Okbazghi, S.Z.; Alfaleh, M.A.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Bakhaidar, R.B.; Alselami, M.O.; AL Zahrani, M.; Alqarni, H.M.; Alghaith, A.F.; Alshehri, S.; et al. Wasp venom peptide improves the proapoptotic activity of alendronate sodium in A549 lung cancer cells. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0264093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhakamy, N.A.; Ahmed, O.A.A.; Shadab; Fahmy, U. A. Mastoparan, a Peptide Toxin from Wasp Venom Conjugated Fluvastatin Nanocomplex for Suppression of Lung Cancer Cell Growth. Polymers 2021, 13, 4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, O. , et al., Anti-cancer peptide mastoparan and derivatives kill HCT-116 and HT-29 colon cancer cells by peptide-mediated Lysis | Acadia Scholar. 2020.

- Hilchie, A.L.; Sharon, A.J.; Haney, E.F.; Hoskin, D.W.; Bally, M.B.; Franco, O.L.; Corcoran, J.A.; Hancock, R.E. Mastoparan is a membranolytic anti-cancer peptide that works synergistically with gemcitabine in a mouse model of mammary carcinoma. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 3195–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Xi, X.; Bininda-Emonds, O.R.; Shaw, C.; Chen, T.; Zhou, M. Evaluation of the bioactivity of a mastoparan peptide from wasp venom and of its analogues designed through targeted engineering. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-R. , et al., Antitumor effects, cell selectivity and structure–activity relationship of a novel antimicrobial peptide polybia-MPI. Peptides, 2008. 29(6): p. 963-968.

- da Silva, A.M.B. , et al., Pro-necrotic Activity of Cationic Mastoparan Peptides in Human Glioblastoma Multiforme Cells Via Membranolytic Action. Molecular Neurobiology, 2018. 55(7): p. 5490-5504.

- Maltby, S.; Khazaie, K.; McNagny, K.M. Mast cells in tumor growth: Angiogenesis, tissue remodelling and immune-modulation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 2009, 1796, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.M.; Raymond, W.W.; Bergers, G.; Laig-Webster, M.; Behrendtsen, O.; Werb, Z.; Caughey, G.H.; Hanahan, D. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 1382–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, P.; Nakata, K.; Oyama, K.; Higashijima, N.; Sagara, A.; Date, S.; Luo, H.; Hayashi, M.; Kubo, A.; Wu, C.; et al. Blockade of histamine receptor H1 augments immune checkpoint therapy by enhancing MHC-I expression in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speisky, D. , et al., Histamine H4 Receptor Expression in Triple-negative Breast Cancer: An Exploratory Study. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society, 2022. 70(4): p. 311-322.

- Akdis, C.A.; Blaser, K. Histamine in the immune regulation of allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 112, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Nakamura, E.; Okabe, S. Histamine regulates growth of malignant melanoma implants via H2 receptors in mice. Inflammopharmacology 2005, 13, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martner, A.; Wiktorin, H.G.; Lenox, B.; Sander, F.E.; Aydin, E.; Aurelius, J.; Thorén, F.B.; Ståhlberg, A.; Hermodsson, S.; Hellstrand, K. Histamine Promotes the Development of Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells and Reduces Tumor Growth by Targeting the Myeloid NADPH Oxidase. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 5014–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.M.; Akin, C.; Gilfillan, A.M. Pharmacological targeting of the KIT growth factor receptor: a therapeutic consideration for mast cell disorders. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.C.; Corless, C.L.; Demetri, G.D.; Blanke, C.D.; Von Mehren, M.; Joensuu, H.; McGreevey, L.S.; Chen, C.-J.; Van den Abbeele, A.D.; Druker, B.J.; et al. Kinase Mutations and Imatinib Response in Patients With Metastatic Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 4342–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S. , et al., Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified kit arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2013. 31(26): p. 3182-3190.

- Jachetti, E. , et al., Imatinib spares cKit-expressing prostate neuroendocrine tumors, whereas kills seminal vesicle epithelial-stromal tumors by targeting PDGFR-β. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 2017. 16(2): p. 365-375.

- Pittoni, P.; Tripodo, C.; Piconese, S.; Mauri, G.; Parenza, M.; Rigoni, A.; Sangaletti, S.; Colombo, M.P. Mast Cell Targeting Hampers Prostate Adenocarcinoma Development but Promotes the Occurrence of Highly Malignant Neuroendocrine Cancers. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5987–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoszuk, M.; Corwin, M.A. Acceleration of tumor growth and peri-tumoral blood clotting by imatinib mesylate (Gleevec™). Int. J. Cancer 2003, 106, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngblood, B.A.; Brock, E.C.; Leung, J.; Falahati, R.; Bochner, B.S.; Rasmussen, H.S.; Peterson, K.; Bebbington, C.; Tomasevic, N. Siglec-8 antibody reduces eosinophils and mast cells in a transgenic mouse model of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, N.; Mao, F.; Teng, Y.; Wang, T.; Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, P.; et al. Increased intratumoral mast cells foster immune suppression and gastric cancer progression through TNF-α-PD-L1 pathway. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, A.; Tachi, M.; Ejima, Y.; Endo, Y.; Toyama, H.; Matsubara, M.; Saito, K.; Yamauchi, M.; Miura, C.; Kazama, I. Anti-Allergic Drugs Tranilast and Ketotifen Dose-Dependently Exert Mast Cell-Stabilizing Properties. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, M.; McKenzie, S.H.; Steven, I.; Cooper, C.; Lanz, R. Efficacy and safety of ketotifen eye drops in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. , et al., Repurposing ketotifen as a therapeutic strategy for neuroendocrine prostate cancer by targeting the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. Cellular Oncology, 2023. 46(5): p. 1445-1456.

- Hemmati, A.; Nazari, Z.; Motlagh, M.; Goldasteh, S. THE ROLE OF SODIUM CROMOLYN IN TREATMENT OF PARAQUAT-INDUCED PULMONARY FIBROSIS IN RAT. Pharmacol. Res. 2002, 46, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutello, K. and V. Gupta, Cromolyn Sodium. StatPearls, 2024.

- Soucek, L.; Lawlor, E.R.; Soto, D.; Shchors, K.; Swigart, L.B.; Evan, G.I. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, J.D.; Elias, M.G.; Fereydouni, M.; Daniels-Wells, T.R.; Dellinger, A.L.; Penichet, M.L.; Kepley, C.L. Human Mast Cells From Adipose Tissue Target and Induce Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobits, B.; Holcmann, M.; Amberg, N.; Swiecki, M.; Grundtner, R.; Hammer, M.; Colonna, M.; Sibilia, M. Imiquimod clears tumors in mice independent of adaptive immunity by converting pDCs into tumor-killing effector cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldford, S.A.; Haidl, I.D.; Howatt, M.A.; Leiva, C.A.; Johnston, B.; Marshall, J.S. A Critical Role for Mast Cells and Mast Cell-Derived IL-6 in TLR2-Mediated Inhibition of Tumor Growth. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7067–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudeck, J.; Ghouse, S.M.; Lehmann, C.H.; Hoppe, A.; Schubert, N.; Nedospasov, S.A.; Dudziak, D.; Dudeck, A. Mast-Cell-Derived TNF Amplifies CD8+ Dendritic Cell Functionality and CD8+ T Cell Priming. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Weaver, B.; Choi, H.W.; Abraham, S.N.; Staats, H.F. Mast cell activators as novel immune regulators. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018, 41, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLachlan, J.B.; Shelburne, C.P.; Hart, J.P.; Pizzo, S.V.; Goyal, R.; Brooking-Dixon, R.; Staats, H.F.; Abraham, S.N. Mast cell activators: a new class of highly effective vaccine adjuvants. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, D.; Donzé, O.; Talabot-Ayer, D.; Mézin, F.; Palmer, G.; Gabay, C. Interleukin (IL)-33 induces the release of pro-inflammatory mediators by mast cells. Cytokine 2007, 40, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berselli, E.; Coccolini, C.; Tosi, G.; Gökçe, E.H.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Fathi, F.; Krambeck, K.; Souto, E.B. Therapeutic Peptides and Proteins: Stabilization Challenges and Biomedical Applications by Means of Nanodelivery Systems. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2024, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rische, C.H.; Thames, A.H.; Krier-Burris, R.A.; O’sUllivan, J.A.; Bochner, B.S.; Scott, E.A. Drug delivery targets and strategies to address mast cell diseases. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2023, 20, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Arlian, B.M.; Nycholat, C.M.; Wei, Y.; Tateno, H.; A Smith, S.; Macauley, M.S.; Zhu, Z.; Bochner, B.S.; Paulson, J.C. Nanoparticles Displaying Allergen and Siglec-8 Ligands Suppress IgE-FcεRI–Mediated Anaphylaxis and Desensitize Mast Cells to Subsequent Antigen Challenge. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 2290–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoh, Y.; Tadokoro, S.; Tanabe, H.; Inoue, M.; Hirashima, N.; Nakanishi, M.; Furuno, T. Inhibitory effects of a cationic liposome on allergic reaction mediated by mast cell activation. 86, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, D.A.; Johnson-Weaver, B.T.; Batty, C.J.; Bachelder, E.M.; Abraham, S.N.; Staats, H.F.; Ainslie, K.M. Delivery of small molecule mast cell activators for West Nile Virus vaccination using acetalated dextran microparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 634, 122658–122658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontiveros-Padilla, L.; Batty, C.J.; Hendy, D.A.; Pena, E.S.; Roque, J.A.; Stiepel, R.T.; Carlock, M.A.; Simpson, S.R.; Ross, T.M.; Abraham, S.N.; et al. Development of a broadly active influenza intranasal vaccine adjuvanted with self-assembled particles composed of mastoparan-7 and CpG. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-E.; Lim, S.-K.; Kim, J.-S. In vivo antitumor effect of cromolyn in PEGylated liposomes for pancreatic cancer. J. Control. Release 2012, 157, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.K.; El-Maraghy, S.A.; ElMeshad, A.N.; Nady, O.M.; Hammam, O.A. Cromolyn chitosan nanoparticles as a novel protective approach for colorectal cancer. Chem. Interactions 2017, 275, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.K.; El-Maraghy, S.A.; Sabry, D.; Nady, O.M.; Senousy, M.A. Cromolyn chitosan nanoparticles reverse the DNA methylation of RASSF1A and p16 genes and mitigate DNMT1 and METTL3 expression in breast cancer cell line and tumor xenograft model in mice. Chem. Interactions 2022, 365, 110094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhakamy, N.A.; Okbazghi, S.Z.; Alfaleh, M.A.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Bakhaidar, R.B.; Alselami, M.O.; AL Zahrani, M.; Alqarni, H.M.; Alghaith, A.F.; Alshehri, S.; et al. Wasp venom peptide improves the proapoptotic activity of alendronate sodium in A549 lung cancer cells. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0264093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Bao, S.; Chen, S.; Yang, Q.; Lou, K.; Gai, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Phytosomes Loaded with Mastoparan-M Represent a Novel Strategy for Breast Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, ume 20, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lei, Q.; Wang, F.; Deng, D.; Wang, S.; Tian, L.; Shen, W.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, S. Fluorinated Polymer Mediated Transmucosal Peptide Delivery for Intravesical Instillation Therapy of Bladder Cancer. Small 2019, 15, e1900936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Li, Y.; Cong, Z.; Li, Z.; Xie, L.; Wu, S. Bioengineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles encapsulated Polybia–mastoparan I fusion peptide as a promising nanoplatform for bladder cancer immune-modulatory chemotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1129771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yeh, C.-R.; Ding, J.; Li, L.; Chang, C.; Yeh, S. Recruited mast cells in the tumor microenvironment enhance bladder cancer metastasis via modulation of ERβ/CCL2/CCR2 EMT/MMP9 signals. Oncotarget 2015, 7, 7842–7855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, X.; Guo, Q.; Liu, Z.; Liu, K.; He, J.; Li, R.; Sun, H.; Yao, W.; Wang, L. Facile preparation of nanomicelles using polymyxin E for enhanced antitumor effects. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2021, 33, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Bao, S.; Chen, S.; Yang, Q.; Lou, K.; Gai, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Phytosomes Loaded with Mastoparan-M Represent a Novel Strategy for Breast Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, ume 20, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichterman, J.N.; Reddy, S.M. Mast Cells: A New Frontier for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2021, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, P.; Letard, S.; Ciufolini, M.; Gros, L.; Humbert, M.; Castéran, N.; Borge, L.; Hajem, B.; Lermet, A.; Sippl, W.; et al. Masitinib (AB1010), a Potent and Selective Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Targeting KIT. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PEPTIDE | SEQUENCE | ORIGIN | REF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mastoparan-L | INLKALAALAKKIL-NH₂ | Vespa lewisii | [48] |

| Mastoparan-X | INWKGIAAMAKKLL- NH₂ | Vespa xanthoptera | [49] |

| Mastoparan-C | LNLKALLAVAKKIL-NH₂ | Vespa crabro | [50] |

| Polybia-MPI | IDWKKLLDAAKQIL-NH₂ | Polybia paulista | [51] |

| KM8 | KLLKKNLKALAALAKKIL-NH₂ | M-L analog | [52] |

| [I5, R8] Mastoparan | INLKILARLAKALL-NH₂ | M-L analog | [53] |

| Mastoparan-3 | NLKALAALAKKIL-NH₂ | M-L analog | [54] |

| Mastoparan-7 (M7) | INLKALAALAKALL- NH₂ | M-L analog | [55] |

| MP12W | INLKALAALAWALL-NH₂ | M7 analog | [56] |

| MC Modulator | Cancer Type | In vitro model |

Time (hrs) |

IC50 (μM) |

Ref |

| MC Inhibitor | |||||

| Cromolyn sodium | Colon | HT-29 | 72 | 2.33 | [72] |

| Healthy | MCF-10 | 7.33 | |||

| MC Agonist | |||||

| Mastoparan-L-COOH |

Lymphoma | Jurkat | 24 |

77.9 | [73] |

| GBM | U87 | 311.7 | |||

| Cervical | SiHA | 172.1 | |||

| Breast | MCF-7 | 432.5 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 251.25 | ||||

| SK-BR3 | 320.3 | ||||

| Melanoma | A2058 | 140 | |||

| B16F10-Nex2 | 165 | ||||

| Healthy | Melan-a | 411.5 | |||

| HACaT | 428 | ||||

| Mastoparan-L-NH2 |

Lung | A549 | ~14 | [74] | |

| 34.3 | [75] | ||||

| Colon | HCT-116 p53 double knockout | ~30-35 | [76] | ||

| HT-29 | ~40-45 | ||||

| Leukemia | Jurkat | 8-9.2 | [77] |

||

| THP-1 | |||||

| Myeloma | HOPC | 11 | |||

| Breast | MDA-MB-231 | 20–24 |

|||

| T47D | |||||

| MDA-MB-468 | |||||

| 4T1 | |||||

| SKBR3 | |||||

| MCF7 | |||||

| MCF7-TX400 | |||||

| Prostate | PC3 | <50 | |||

| Ovarian | SCOV3 | 25 | |||

| Cervical | HeLa | 10 | |||

| Healthy | PBMCs | 48 | |||

| Leukemia | HL60 | NA | 10 | [54] | |

| Breast | MCF-7 | 48 | 26.6 | [52] | |

| MCF-7/Dox | 27.6 | ||||

| Lung | A549 | 28.3 | |||

| NCI-446 | 28.4 | ||||

| Esophageal | Eca109 | 31.9 | |||

| Healthy | LO2 | 53.2 | |||

| HEK-293 | 51.5 | ||||

| KM8 | Breast | MCF-7 | 5.3 | ||

| MCF-7/Dox | 5.5 | ||||

| Lung | A549 | 6.2 | |||

| NCI-446 | 6.3 | ||||

| Esophageal | Eca109 | 7.4 | |||

| Healthy | LO2 | 45.9 | |||

| HEK-293 | 45.0 | ||||

| Mastoparan-C | Lung | H157 | 24 | 13.57 | [78] |

| Breast | MCF-7 | 25.27 | |||

| Prostate | PC-3 | 6.29 | |||

| GBM | U251-MG | 36.65 | |||

| Healthy | HMEC-1 | 57.15 | |||

| Polybia-MPI |

Prostate | PC-3 | 64.68 | [79] | |

| Bladder | Biu87 | 52.16 | |||

| EJ | 75.51 | ||||

| Healthy | HUVEC | 55.6 | |||

| GBM | T298G | 2 | 32.7 | [80] | |

| Mastoparan-X | 18.05 | ||||

| Leukemia | HL60 | NA | 10 | [54] | |

| Mastoparan-3 | 200 | ||||

| Mastoparan [I5, R8] |

Leukemia | THP-1 | 72 | 24.5 | [53] |

| Healthy | HEK-293 | >200 | |||

| MC AGONIST | CANCER | MODEL | VEHICLE | DOSE | SCHEDULE | CONCLUSIONS | REF |

| Cromolyn sodium | Pancreatic | Bx-PC-3 subQ in BALB/c mice | PEGylated liposomes | IV 10mg/kg | Twice weekly for 4 weeks | Encapsulated cromolyn outperformed soluble in tumor growth inhibition, more apoptosis 24 hr after treatment | [115] |

| Colorectal | DMH induced in Wister albino rats | Chitosan nanoparticles | IP 5mg/kg | Twice weekly for 16 weeks | Survival not assessed; maintenance of colon architecture, decreased MC frequency | [116] | |

| Mastoparan | Lung | In vitro |

Alendronate sodium nanoconjugate | A549 24 hr MTT | NA | IC50 = 1.3 μM; vehicle alone 37.6 μM, alone ~13 | [74] |

| Fluvastatin mastoparan nanoconjugate | A549 4hr MTT | More apoptotic proteins present in MAS-FLV-NC; IC50 = 18.6 μM; vehicle alone = 58.4 μM, mas = 34.3 μM | [75] | ||||

| Mastoparan-M | Breast | 4T1 subQ in BALB/c mice | Soya phosphatidylcholines phytosomes | IV 2.7mg/kg | q4d 4x | Encapsulated mastoparan outperformed soluble in tumor growth inhibition with more apoptosis (Bcl-2 and TUNEL) and decreased proliferation (Ki-67) | [124] |

| Polybia-mastoparan I (MPI) | Bladder | MB49 subQ in C57/BL6 mice | Outer membrane vesicles of gram-negative bacteria | IT 100 μg vesicle protein | q3d 4x | DC maturation, macrophage recruitment, CD4+ and CD8+ infiltration | [121] |

| T24 subQ in BALB/c nude mice | Fluorinated PEI nanoparticles | 0.5 mg/kg intravesical | 60min long treatment 1x | NPs resulted in superior tumor control a SOC chemo (MMC), no weight loss | [120] | ||

| Polymyxin E | Cervical | U14 subQ in Kunming mice | PE-Doxorubicin loaded micelles | 2.5mg/kg DOX I.V. | q2d 7x | PE not efficacious alone, but when combined with DOX, better than either alone | [123] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).