Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Novelty of the Work

1.2. Paper Structure

2. Background

2.1. Model Compression Techniques

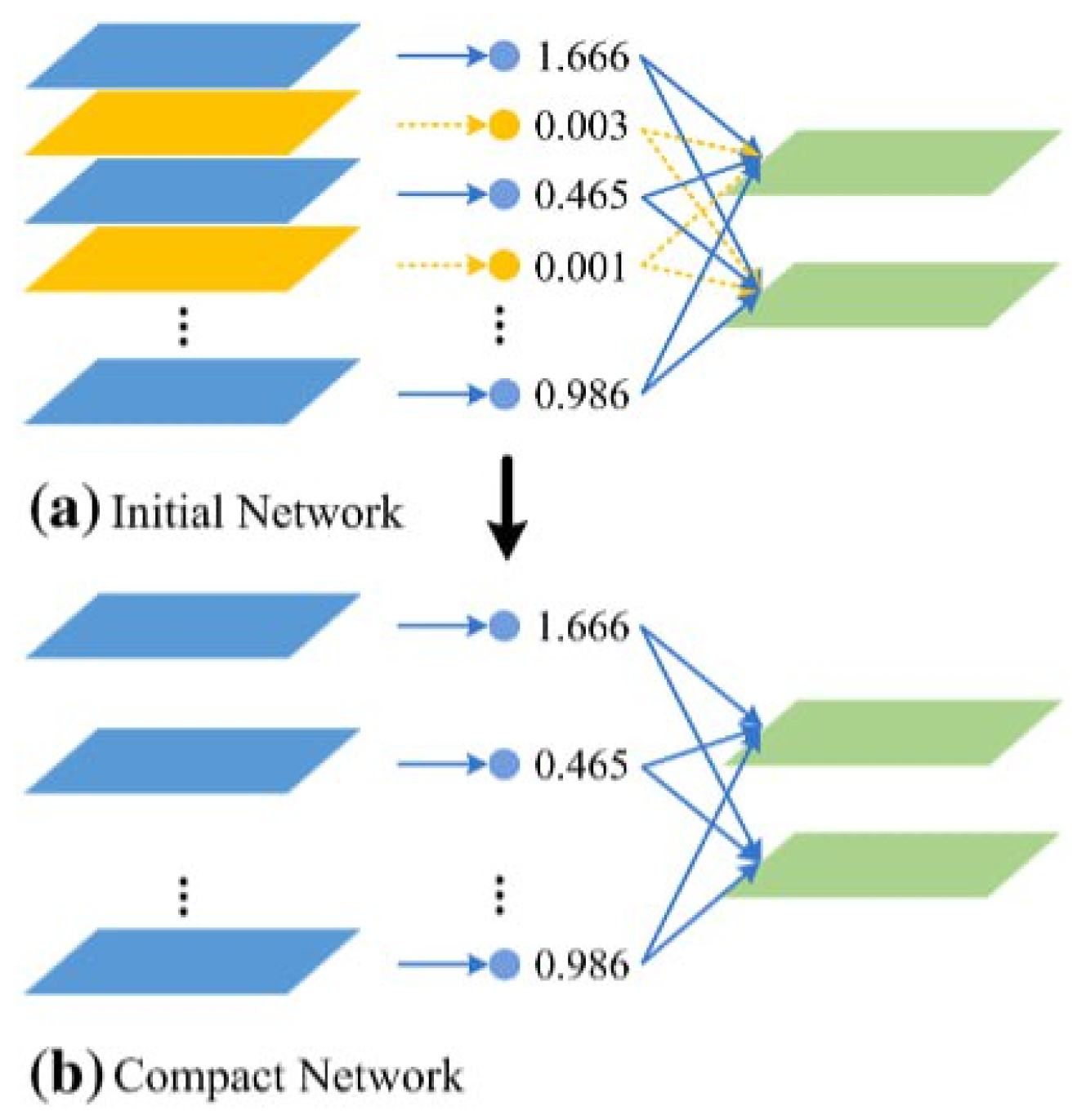

2.1.1. Pruning

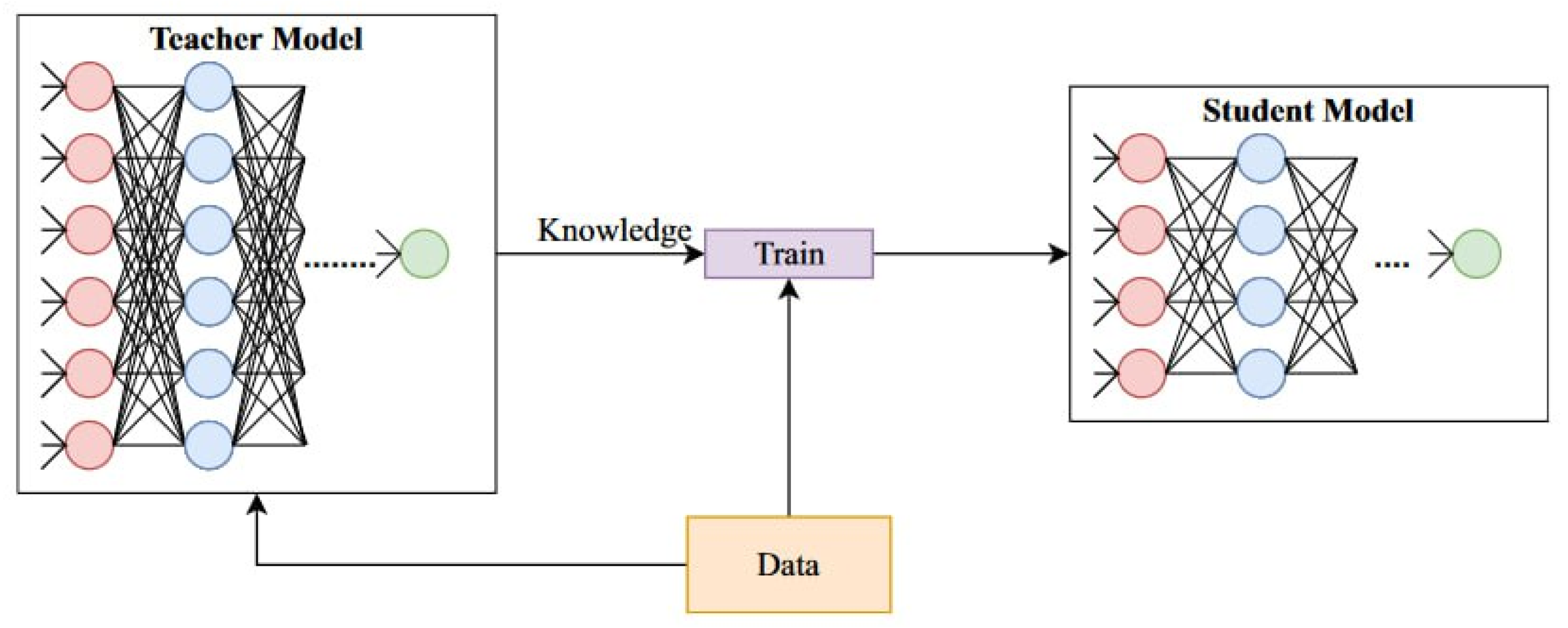

2.1.2. Knowledge Distillation

- and are the outputs of the student and teacher models, respectively.

- is the teacher’s probability distribution over the output classes, softened by a temperature T.

- is the student’s output distribution.

- is the cross-entropy loss with the true labels y, and is the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the teacher and student distributions.

- is a weighting factor that balances the two loss terms.

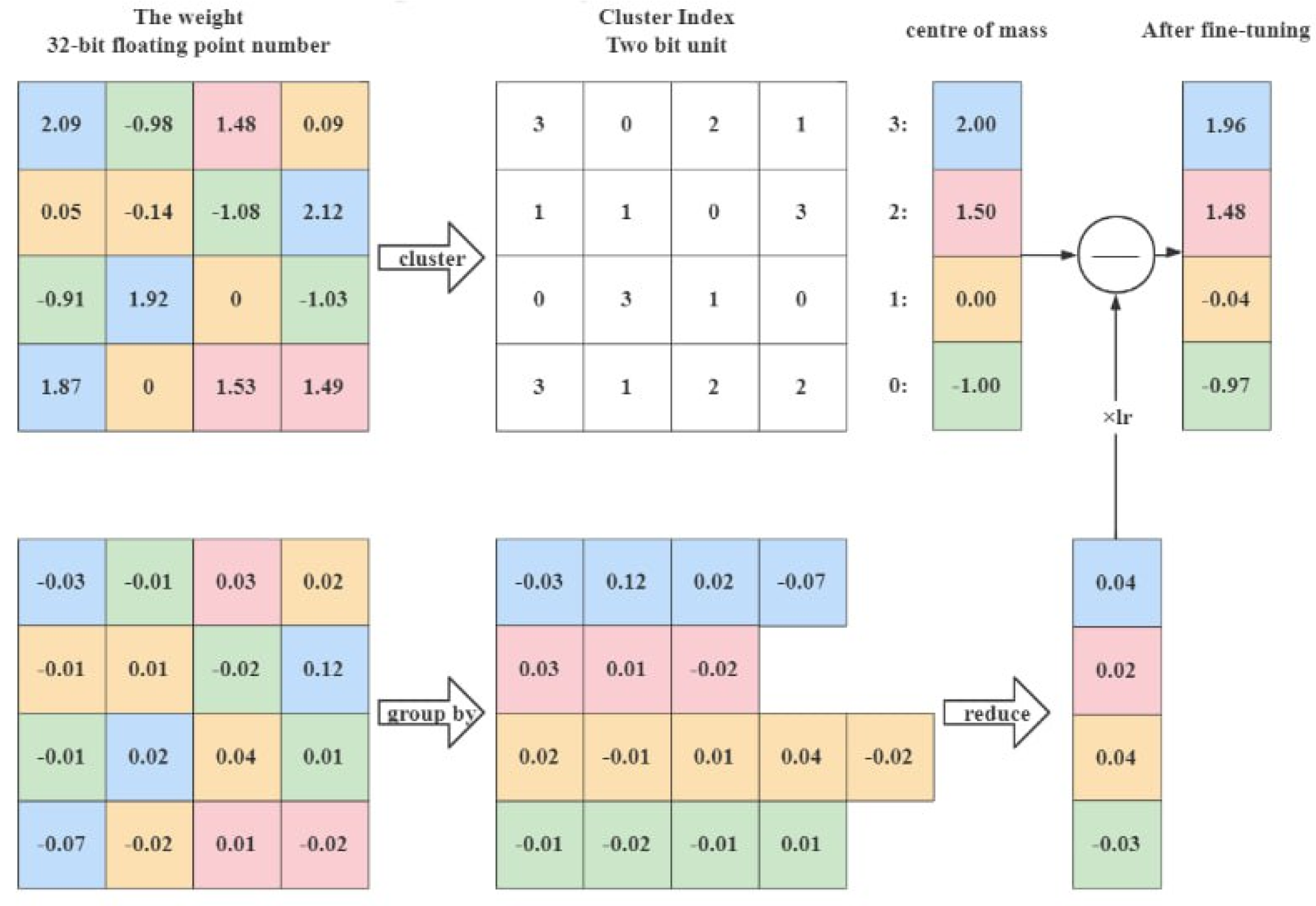

2.1.3. Quantization

2.2. Adversarial Attack Generation

- is the loss function with respect to the model M and the target label y,

- is the adversarial example,

- is the perturbation limit, controlling the maximum allowable change to the input,

- is the step size, determining how much the adversarial example is modified in each iteration.

2.2.1. Evaluation Metrics for Adversarial Robustness

Robustness Accuracy:

Average Perturbation:

2.2.2. Defense Mechanisms

Adversarial Training:

- denotes the cross-entropy loss,

- is the model’s prediction on clean input ,

- is the model’s prediction on the adversarial example ,

- controls the balance between the losses from clean and adversarial examples.

Defensive Distillation:

Adversarial Purification:

Input Transformation:

2.2.3. Comparison of Defense Techniques

2.3. Compression and adversarial robustness

3. Methodology

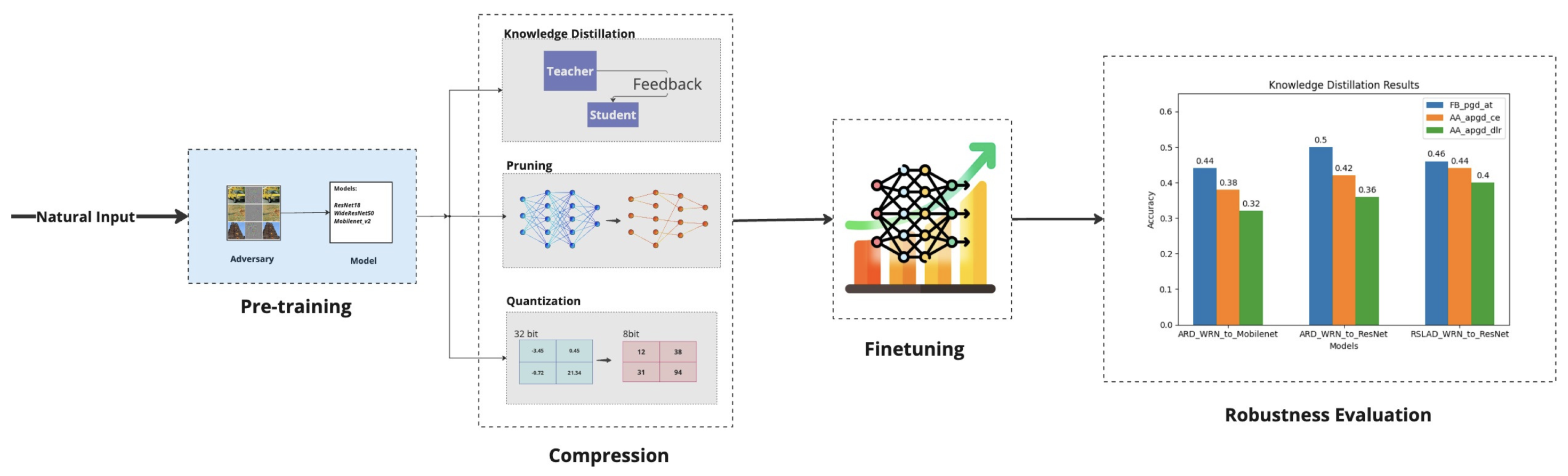

3.1. Pipeline Overview

- Pretraining

- Compression

- Fine-tuning

- Evaluation

3.1.1. Pretraining

3.1.2. Compression

3.1.3. Fine-Tuning

3.1.4. Evaluation

3.2. Benchmarking Pipeline Key Components

3.2.1. Model Compression Metrics

3.2.2. Adversarial Robustness Evaluation

3.2.3. Categorization of Compression Techniques

3.2.4. Performance Visualization

| Algorithm 1Benchmarking Pipeline for Pretrained and Compressed Models |

|

4. Experimental Setup

5. Results

6. Discussion

- Hydra Techniques: The Hydra methodologies demonstrate substantial compression rates (99x, 95x, and 90x); surprisingly, these high compression levels are accompanied by a marked increment in adversarial robustness, particularly when subjected to the FB-PGD and AA attacks.

- Knowledge Distillation (IAD vs. KD): The IAD framework displays superior performance compared to traditional KD approaches, evidenced by enhanced robustness metrics. Notably, IAD methods achieve higher accuracy under adversarial conditions, indicating a potential advantage in utilizing intra-architecture relationships to mitigate adversarial effects. Here IIAD-I stands for Introspective Adversarial Distillation based on ARD [44] and IAD-II Introspective Adversarial Distillation based on AKD2 [46].

- RAP-ADMM Techniques: Models subjected to RAP-ADMM compression exhibit varying degrees of adversarial resilience, suggesting that the selection of appropriate compression rates plays a critical role in optimizing both model size and robustness.

- RSLAD and Quanztion Frameworks: Both RSLAD and Quanztion frameworks present compelling results, particularly the Quanztion framework, which achieves notable accuracy metrics while maintaining a viable compression rate. This indicates a promising avenue for future research focusing on integrating quantization with adversarial robustness.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dantas, P.V.; Sabino da Silva Jr, W.; Cordeiro, L.C.; Carvalho, C.B. A comprehensive review of model compression techniques in machine learning. Applied Intelligence 2024, pp. 1–41.

- Bai, T.; Luo, J.; Zhao, J.; Wen, B.; Wang, Q. Recent advances in adversarial training for adversarial robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.01356 2021.

- Carlini, N.; Athalye, A.; Papernot, N.; Brendel, W.; Rauber, J.; Tsipras, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Madry, A.; Kurakin, A. On evaluating adversarial robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.06705 2019.

- Villegas-Ch, W.; Jaramillo-Alcázar, A.; Luján-Mora, S. Evaluating the Robustness of Deep Learning Models against Adversarial Attacks: An Analysis with FGSM, PGD and CW. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Xu, K.; Liu, S.; Cheng, H.; Lambrechts, J.H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, A.; Ma, K.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X. Adversarial robustness vs. In model compression, or both? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019; pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Ta, N.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, M.; Wei, H. A real-time deep learning forest fire monitoring algorithm based on an improved Pruned+ KD model. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 2021, 18, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhulaifi, A.; Alsahli, F.; Ahmad, I. Knowledge distillation in deep learning and its applications. PeerJ Computer Science 2021, 7, e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Su, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, T. Research on compression pruning methods based on deep learning. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, Vol. 2580; 2023; p. 012060. [Google Scholar]

- Shafique, M.A.; Munir, A.; Kong, J. Deep Learning Performance Characterization on GPUs for Various Quantization Frameworks. AI 2023, 4, 926–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, D.; Yi, J.; Bailey, J.; Ma, X.; Gu, Q. Improving adversarial robustness requires revisiting misclassified examples. In Proceedings of the International conference on learning representations; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, H.; Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I. Adversarial logit pairing. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1803.06373 2018.

- Liu, D.; Wu, L.; Zhao, H.; Boussaid, F.; Bennamoun, M.; Xie, X. Jacobian norm with selective input gradient regularization for improved and interpretable adversarial defense. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.13036 2022.

- Ilyas, A.; Santurkar, S.; Tsipras, D.; Engstrom, L.; Tran, B.; Madry, A. Adversarial examples are not bugs, they are features. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Jiménez, G.; Modas, A.; Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Frossard, P. Optimism in the face of adversity: Understanding and improving deep learning through adversarial robustness. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572, arXiv:1412.6572 2014.

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, S. Adversarial examples in the physical world. In Artificial intelligence safety and security; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; pp. 99–112.

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 ieee symposium on security and privacy (sp). Ieee; 2017; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mądry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. stat 2017, 1050. [Google Scholar]

- Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.; Wu, X.; Jha, S.; Swami, A. Distillation as a defense to adversarial perturbations against deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE; 2016; pp. 582–597. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, F.; Liang, M.; Dong, Y.; Pang, T.; Hu, X.; Zhu, J. Defense against adversarial attacks using high-level representation guided denoiser. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 1778–1787.

- Guo, C.; Rana, M.; Cisse, M.; Van Der Maaten, L. Countering adversarial images using input transformations. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1711.00117 2017.

- Tramèr, F.; Kurakin, A.; Papernot, N.; Goodfellow, I.; Boneh, D.; McDaniel, P. Ensemble adversarial training: Attacks and defenses. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1705.07204 2017.

- Han, C.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Cui, W.; Yan, B. A Pruning Method Combined with Resilient Training to Improve the Adversarial Robustness of Automatic Modulation Classification Models. Mobile Networks and Applications.

- Wang, L.; Ding, G.W.; Huang, R.; Cao, Y.; Lui, Y.C. Adversarial robustness of pruned neural networks 2018.

- Jordao, A.; Pedrini, H. On the effect of pruning on adversarial robustness. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp.1–11.

- Wijayanto, A.W.; Choong, J.J.; Madhawa, K.; Murata, T. Towards robust compressed convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dy, J.; Ioannidis, S. Pruning adversarially robust neural networks without adversarial examples. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM). IEEE; 2022; pp. 993–998. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, S.; Nazemi, M.; Beerel, P.A.; Pedram, M. A tunable robust pruning framework through dynamic network rewiring of dnns. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.03083 2020.

- Gorsline, M.; Smith, J.; Merkel, C. On the adversarial robustness of quantized neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 on Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI, 2021, pp. 189–194.

- Duncan, K.; Komendantskaya, E.; Stewart, R.; Lones, M. Relative robustness of quantized neural networks against adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Gan, C.; Han, S. Defensive quantization: When efficiency meets robustness. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1904.08444 2019.

- Song, C.; Ranjan, R.; Li, H. A layer-wise adversarial-aware quantization optimization for improving robustness. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2110.12308 2021.

- Neshaei, S.P.; Boreshban, Y.; Ghassem-Sani, G.; Mirroshandel, S.A. The Impact of Quantization on the Robustness of Transformer-based Text Classifiers. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2403.05365 2024.

- Li, Q.; Meng, Y.; Tang, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z. Investigating the Impact of Quantization on Adversarial Robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05639 2024.

- Panda, P. Quanos: adversarial noise sensitivity driven hybrid quantization of neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design, 2020, pp. 187–192.

- Galloway, A.; Taylor, G.W.; Moussa, M. Attacking binarized neural networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1711.00449 2017.

- Song, C.; Fallon, E.; Li, H. Improving adversarial robustness in weight-quantized neural networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2012.14965 2020.

- Hinton, G. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1503.02531 2015.

- Cao, Z.; Bao, Y.; Meng, F.; Li, C.; Tan, W.; Wang, G.; Liang, Y. Enhancing Adversarial Training with Prior Knowledge Distillation for Robust Image Compression. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2024; pp. 3430–3434. [Google Scholar]

- Rauber, J.; Zimmermann, R.; Bethge, M.; Brendel, W. Foolbox Native: Fast adversarial attacks to benchmark the robustness of machine learning models in PyTorch, TensorFlow, and JAX. Journal of Open Source Software 2020, 5, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, J.; Brendel, W.; Bethge, M. Foolbox: A Python toolbox to benchmark the robustness of machine learning models. In Proceedings of the Reliable Machine Learning in the Wild Workshop, 2017., 34th International Conference on Machine Learning.

- Sehwag, V.; Wang, S.; Mittal, P.; Jana, S. Hydra: Pruning adversarially robust neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 19655–19666. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Ye, J.; Chen, G.; Zhao, J.; Heng, P.A. Robustness of accuracy metric and its inspirations in learning with noisy labels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol.

- Goldblum, M.; Fowl, L.; Feizi, S.; Goldstein, T. Adversarially robust distillation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 3996–4003.

- Bernhard, R.; Moellic, P.A.; Dutertre, J.M. Impact of low-bitwidth quantization on the adversarial robustness for embedded neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW). IEEE; 2019; pp. 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Chang, S.; Wang, Z. Robust overfitting may be mitigated by properly learned smoothening. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Defense Mechanism | Effectiveness | Complexity | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adversarial Training | High | Moderate | High |

| Defensive Distillation | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Adversarial Purification | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Input Transformation | Low-Moderate | Low | Low |

| Model | Architecture | Compression Technique | Adversarial Attacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAP-ADMM | WideResNet | ADMM Pruning | FB_pgd_at, AA_apgd-ce, AA_apgd-dlr |

| Hydra | ResNet | Layer-wise Pruning | FB_pgd_at, AA_apgd-ce, AA_apgd-dlr |

| RSLAD | ResNet (Student) | Distillation (Soft-label) | FB_pgd_at, AA_apgd-ce, AA_apgd-dlr |

| ARD | MobileNet_v2 | Distillation | FB_pgd_at, AA_apgd-ce, AA_apgd-dlr |

| IAD | ResNet (Student) | Distillation (Unreliable-student) | FB_pgd_at, AA_apgd-ce, AA_apgd-dlr |

| Low-bitwidth | WideResNet | Low-bit Qauntization | FB_pgd_at |

| Compression Rate | Model Name | # Parameters | Architecture | FB-PGD Attack | AA (APGD-CE) | AA (APGD-DLR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99x | finetune 99x | 122,283 | wrn_28_4 | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.00% |

| 95x | finetune 95x | 611,419 | wrn_28_4 | 8.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 90x | finetune 90x | 1,222,839 | wrn_28_4 | 4.0% | 2.0% | 0.0% |

| Model | Compression Rate | # Parameters | Architecture | FB-PGD Attack | AA (APGD-CE) | AA (APGD-DLR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAD-I | 3.4x | 11M | resnet18 | 52.00% | 40.00% | 36.00% |

| IAD-II | 3.4x | 11M | resnet18 | 48.00% | 44.00% | 42.00% |

| Model | Compression Rate | # Parameters | Architecture | FB-PGD Attack | AA (APGD-CE) | AA (APGD-DLR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARD_WRN_to_Mobilenet | 10.7x | 3.4M | mobilenet-v2 | 44.00% | 38.00% | 32.00% |

| ARD_WRN_to_ResNet | 3.12x | 11.7M | ResNet | 50.00% | 42.00% | 36.00% |

| Model | Compression Rate | # Parameters | Architecture | FB-PGD Attack | AA (APGD-CE) | AA (APGD-DLR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAP_prune | 12x | 931,163 | resnet18 | 40.00% | 36.00% | 32.00% |

| RAP_prune | 16x | 698,373 | resnet18 | 40.00% | 34.00% | 30.00% |

| RAP_prune | 8x | 1,396,745 | resnet18 | 42.00% | 32.00% | 30.00% |

| RAP_pre | Not Compressed | 11,173,962 | resnet18 | 44.00% | 42.00% | 36.00% |

| RAP_fine | 12x | 931,163 | resnet18 | 42.00% | 38.00% | 32.00% |

| RAP_fine | 16x | 698,373 | resnet18 | 42.00% | 36.00% | 34.00% |

| RAP_fine | 8x | 1,396,745 | resnet18 | 48.00% | 38.00% | 34.00% |

| Model Name | Compression Rate | # Parameters | Architecture | FB-PGD Attack | AA (APGD-CE) | AA (APGD-DLR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSLAD_WRN_to_ResNet | 3.12x | 11.7M | ResNet | 46.00% | 44.00% | 4.00% |

| RSLAD_WRN_to_Mobilenet_V2 | 10.7x | 3.4M | MobileNet | 46.00% | 42.00% | 36.00% |

| Attack | Accuracy | Compression Rate |

|---|---|---|

| PGD | 56.00% | 32x |

| CWL2 | 49.20% | 32x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).