Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Pharmacologic Management

- Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for sleep disturbances, chronic pain, and mood stabilization.

- Sleep aids, including alpha-blockers or sedative-hypnotics, to manage persistent insomnia.

- Neuropathic pain medications, like low-dose anticonvulsants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), manage nerve-related pain.

- Stimulants, such as modafinil, are used with caution to alleviate severe fatigue.

- Immunomodulators, including intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), in cases with significant immune dysfunction.

- Gastrointestinal antibiotics or antimicrobials to treat gut infections or dysbiosis.

1.2. Non-Pharmacologic Management

- Low-oxalate diets, useful for individuals with oxalate sensitivity or nephrolithiasis, reduce intake of foods such as spinach, beets, and almonds to prevent calcium oxalate accumulation and associated inflammation [27].

- Low-glutamate diets, which avoid foods high in free glutamate (e.g., MSG, soy sauce, aged cheeses), may help reduce excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation mediated by NMDA receptor overactivation [28].

2. Mitochondrial Function in Health and Its Role in ME/CFS Pathophysiology

2.1. Role of Mitochondria in Normal Biochemical Functioning

2.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in ME/CFS

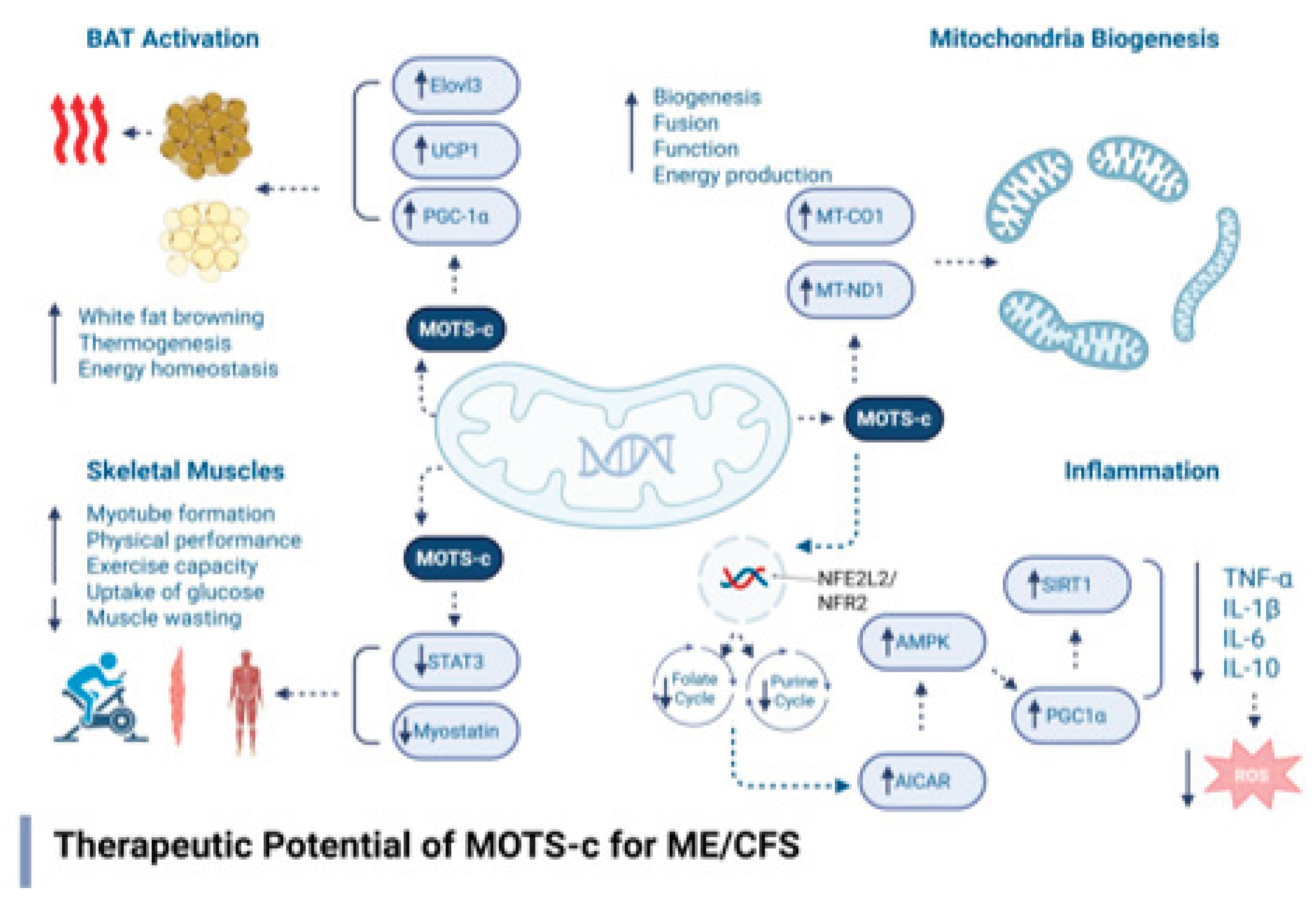

3. Mitochondrial-Derived Peptides and the Therapeutic Potential of MOTS-c in ME/CFS

3.1. Biochemical Mechanisms of MOTS-c

3.2. Preclinical and Clinical Relevance to ME/CFS

3.3. Pharmacological Profile and Delivery Considerations

3.4. Safety Considerations of MOTS-c Therapy

3.5. Regulatory and FDA Guidance for Peptide Therapies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |

| PEM | Post-Exertional Malaise |

| MDPs | Mitochondrial-Derived Peptides |

| MOTS-c | Mitochondrial Open Reading Frame of the 12S rRNA-c |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| ETC | Electron Transport Chain |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| IND | Investigational New Drug |

| OI | Orthostatic Intolerance |

| POTS | Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome |

| BAT | Brown Adipose Tissue |

| NMN | Nicotinamide Mononucleotide |

| NR | Nicotinamide Riboside |

| CoQ10 | Coenzyme Q10 |

References

- Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

- ME/CFS Clinician Coalition. Treatment recommendations for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). 2021. Available from: https://mecfscliniciancoalition.org/.

- DePace, N.L.; Vinik, A.I.; Acosta, C.; Santos, L.; Murray, G.L.; Colombo, J. ORAL VASOACTIVE MEDICATIONS.

- Miller, A.J.; Raj, S.R. Pharmacotherapy for postural tachycardia syndrome. Autonomic Neuroscience. 2018, 215, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes Rivera, M.; Mastronardi, C.; Silva-Aldana, C.T.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Lidbury, B.A. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive review. Diagnostics. 2019, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neustadt, J.; Pieczenik, S.R. Medication-induced mitochondrial damage and disease. Molecular nutrition & food research. 2008, 52, 780–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.H. Pharmacologic effects on mitochondrial function. Developmental disabilities research reviews. 2010, 16, 189–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuda, M.; Kamath, A. Drug induced mitochondrial dysfunction: Mechanisms and adverse clinical consequences. Mitochondrion. 2016, 31, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janhsen, K.; Roser, P.; Hoffmann, K. The problems of long-term treatment with benzodiazepines and related substances: Prescribing practice, epidemiology, and the treatment of withdrawal. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2015, 112, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rowe, P.C.; Underhill, R.A.; Friedman, K.J.; Gurwitt, A.; Medow, M.S.; Schwartz, M.S.; Speight, N.; Stewart, J.M.; Vallings, R.; Rowe, K.S. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome diagnosis and management in young people: a primer. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2017, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grach, S.L.; Seltzer, J.; Chon, T.Y.; Ganesh, R. Diagnosis and management of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. InMayo Clinic Proceedings 2023 Oct 1 (Vol. 98, No. 10, pp. 1544-1551). Elsevier.

- Evrard, A.; Mbatchi, L. Genetic polymorphisms of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters: the long way from bench to bedside. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2012, 12, 1720–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.; Maes, M. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome explained by activated immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. Metab Brain Dis. 2014, 29, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naviaux, R.K.; Naviaux, J.C.; Li, K.; et al. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016, 113, E5472–E5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L. The Energy Envelope Theory and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Aaohn Journal. 2008, 56, 189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangelo, T.; Cagnin, S.; Bondi, D.; Santangelo, C.; Marramiero, L.; Purcaro, C.; Bonadio, R.S.; Di Filippo, E.S.; Mancinelli, R.; Fulle, S.; Verratti, V. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome from current evidence to new diagnostic perspectives through skeletal muscle and metabolic disturbances. Acta Physiologica. 2024, 240, e14122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.M. Sleep Hygiene. Integrative Sleep Medicine. 2021, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Baranwal, N.; Phoebe, K.Y.; Siegel, N.S. Sleep physiology, pathophysiology, and sleep hygiene. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2023, 77, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manresa-Rocamora, A.; Sarabia, J.M.; Javaloyes, A.; Flatt, A.A.; Moya-Ramon, M. Heart rate variability-guided training for enhancing cardiac-vagal modulation, aerobic fitness, and endurance performance: A methodological systematic review with meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021, 18, 10299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, M.; Bosley, M.; Gordon, C.; Pollak, T.A.; Mann, F.; Massou, E.; Morris, S.; Holloway, L.; Harwood, R.; Middleton, K.; Diment, W. ‘I still can’t forget those words’: mixed methods study of the persisting impact on patients reporting psychosomatic and psychiatric misdiagnoses. Rheumatology. 2025, 64, 3842–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlou, A.; Ruble, K.; Stapert, A.F.; Chang, H.C.; Rowe, P.C.; Schwartz, C.L. Orthostatic intolerance in survivors of childhood cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2007, 43, 2685–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, C.P. General information brochure on orthostatic intolerance and its treatment. Chronic Fatigue Clinic Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. 2014.

- Rowe, P.C.; Barron, D.F.; Calkins, H.; Maumenee, I.H.; Tong, P.Y.; Geraghty, M.T. Orthostatic intolerance and chronic fatigue syndrome associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 1999, 82, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.F.; Ellmore, M.; Middleton, G.; Murgatroyd, P.M.; Gee, T.I. Effects of resistance band exercise on vascular activity and fitness in older adults. International journal of sports medicine. 2017, 38, 184–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakše, B.; Jakše, B.; Pajek, M.; Pajek, J. Uric acid and plant-based nutrition. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xue, X.; Ma, L.; Zhou, S.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Sun, W.; Li, C.; Chen, Y. Effect of low-purine diet on the serum uric acid of gout patients in different clinical subtypes: a prospective cohort study. European Journal of Medical Research. 2024, 29, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siener, R.; Hesse, A. Influence of dietary oxalate intake on urinary oxalate excretion. World J Urol. 2006, 24, 305–309. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, K. The potential role of dietary intervention for the treatment of neuroinflammation. Translational Neuroimmunology 2023, 7, 239–66. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Cordero, M.D.; Sáez-Francas, N.; et al. Effect of coenzyme Q10 plus NADH supplementation on maximum heart rate after exercise testing in chronic fatigue syndrome–a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Clin Nutr. 2016, 35, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaguarnera, M.; Vacante, M.; Giordano, M.; et al. Oral acetyl-l-carnitine therapy reduces fatigue in older patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- .

- .

- Teitelbaum, J.E.; Johnson, C.; St Cyr, J. The use of D-ribose in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2006, 12, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomioka, H.; Kawanami, T.; Ogasawara, K.; et al. Effects of nicotinamide riboside and NMN on cardiovascular health and metabolism. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 1171. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, S.; Bertoglio, K.; Ashwood, P.; et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020, 50, 2070–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daverey, A.; Agrawal, S.K. Curcumin protects against white matter injury through NF-κB and Nrf2 cross talk. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2020, 37, 1255–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Folgado, S.L.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Samarghandian, S. The therapeutic effect of resveratrol: Focusing on the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020, 127, 110234. [Google Scholar]

- Osellame, L.D.; Blacker, T.S.; Duchen, M.R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2012, 26, 711–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nolfi-Donegan, D.; Braganza, A.; Shiva, S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: Oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox biology. 2020, 37, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowaltowski, A.J.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Castilho, R.F.; Vercesi, A.E. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009, 47, 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, A.G.; Jänicke, R.U. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell death & differentiation. 1999, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Miller, W.L. Role of mitochondria in steroidogenesis. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2012, 26, 771–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chiabrando, D.; Mercurio, S.; Tolosano, E. Heme and erythropoieis: more than a structural role. haematologica. 2014, 99, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalf, G.F. Deoxyribonucleic acid in mitochondria and its role in protein synthesis. Biochemistry. 1964, 3, 1702–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, S. Mitochondrial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. J Transl Med. 2020, 18, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behan, W.M.; More, I.A.; Behan, P.O. Mitochondrial abnormalities in the postviral fatigue syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 83, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myhill, S.; Booth, N.E.; McLaren-Howard, J. Chronic fatigue syndrome and mitochondrial dysfunction. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2009, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tomas, C.; Brown, A.E.; Newton, J.L. Cellular bioenergetics is impaired in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS One. 2017, 13, e0192817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweetman, E.; Ryan, M.; Edgar, C.; MacKay, A.; Vallings, R.; Tate, W. Changes in the transcriptome of circulating immune cells of a New Zealand cohort with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2020, 34, 2058738420933686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albright, F.; Light, K.; Light, A.; Bateman, L.; Cannon-Albright, L.A. Evidence for a heritable predisposition to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. BMC neurology. 2011, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatomi, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Ishii, A.; et al. Neuroinflammation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: An ¹¹C-(R)-PK11195 PET study. J Nucl Med. 2014, 55, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.J.; Camacho, A.; Martin, C.; et al. Neuroimaging findings in Long COVID and ME/CFS: An overlapping pattern? Front Neurol. 2020, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Son, J.M.; Benayoun, B.A.; Lee, C. The mitochondrial-encoded peptide MOTS-c translocates to the nucleus to regulate nuclear gene expression in response to metabolic stress. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Zeng, J.; Drew, B.G.; et al. The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c promotes metabolic homeostasis and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, J.C.; Lai, R.W.; Woodhead, J.S.T.; et al. MOTS-c is an exercise-induced mitochondrial-encoded regulator of age-dependent physical decline and muscle homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Nguyen, A.; Lee, C. Mitochondrial peptide MOTS-c promotes thermogenesis and browning of white fat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021, 118, e2023993118. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel, F.; Hoel, A.; Pettersen, I.K.; Rekeland, I.G.; Risa, K.; Alme, K.; Sørland, K.; Fosså, A.; Lien, K.; Herder, I.; Thürmer, H.L. A map of metabolic phenotypes in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI insight. 2021, 6, e149217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasia, M. Metabolic Dysregulation in ME/CFS: The Role of Hypometabolism and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Post-Exertional Malaise (Doctoral dissertation).

- Tang, M.; Su, Q.; Duan, Y.; Fu, Y.; Liang, M.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wang, M.; Pang, X.; Ma, J.; Laher, I. The role of MOTS-c-mediated antioxidant defense in aerobic exercise alleviating diabetic myocardial injury. Scientific Reports. 2023, 13, 19781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wei, X.; Wei, P.; Lu, H.; Zhong, L.; Tan, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z. MOTS-c functionally prevents metabolic disorders. Metabolites. 2023, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, C. Overcoming the shortcomings of peptide-based therapeutics. Future Drug Discovery. 2022, 4, FDD75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttenthaler, M.; King, G.F.; Adams, D.J.; Alewood, P.F. Trends in peptide drug discovery. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2021, 20, 309–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Hardie, D.G. New insights into activation and function of the AMPK. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2023, 24, 255–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.; Kim, S.J.; Kumagai, H.; Yen, K.; Cohen, P. Mitochondria-derived peptides in aging and healthspan. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Peptide Drug Products. 2022. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/peptide-drug-products.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).