Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

Statistical Analysis

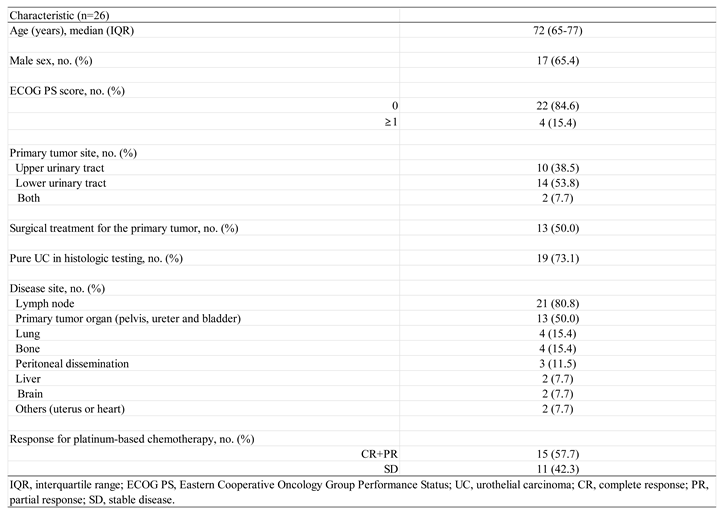

Patient Characteristics

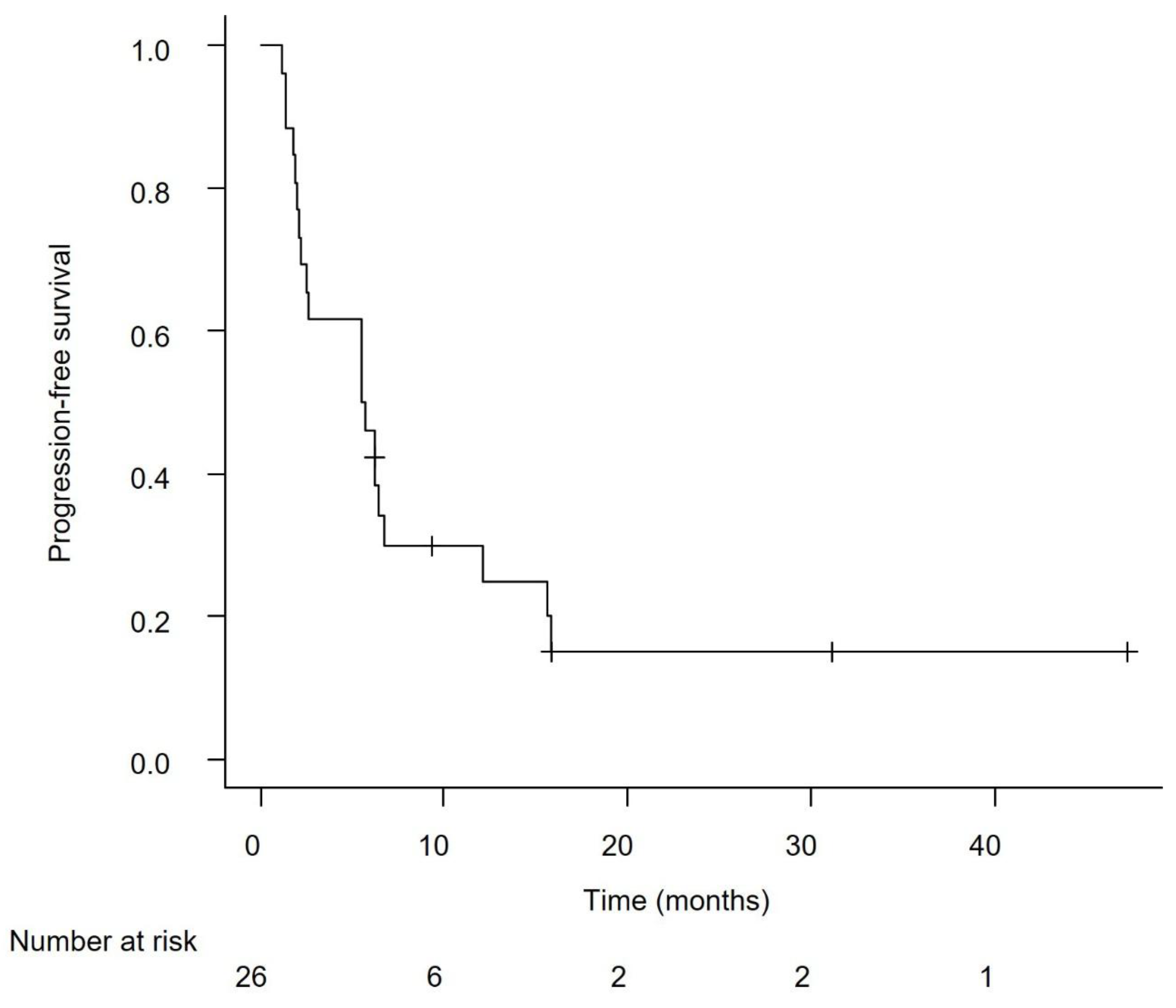

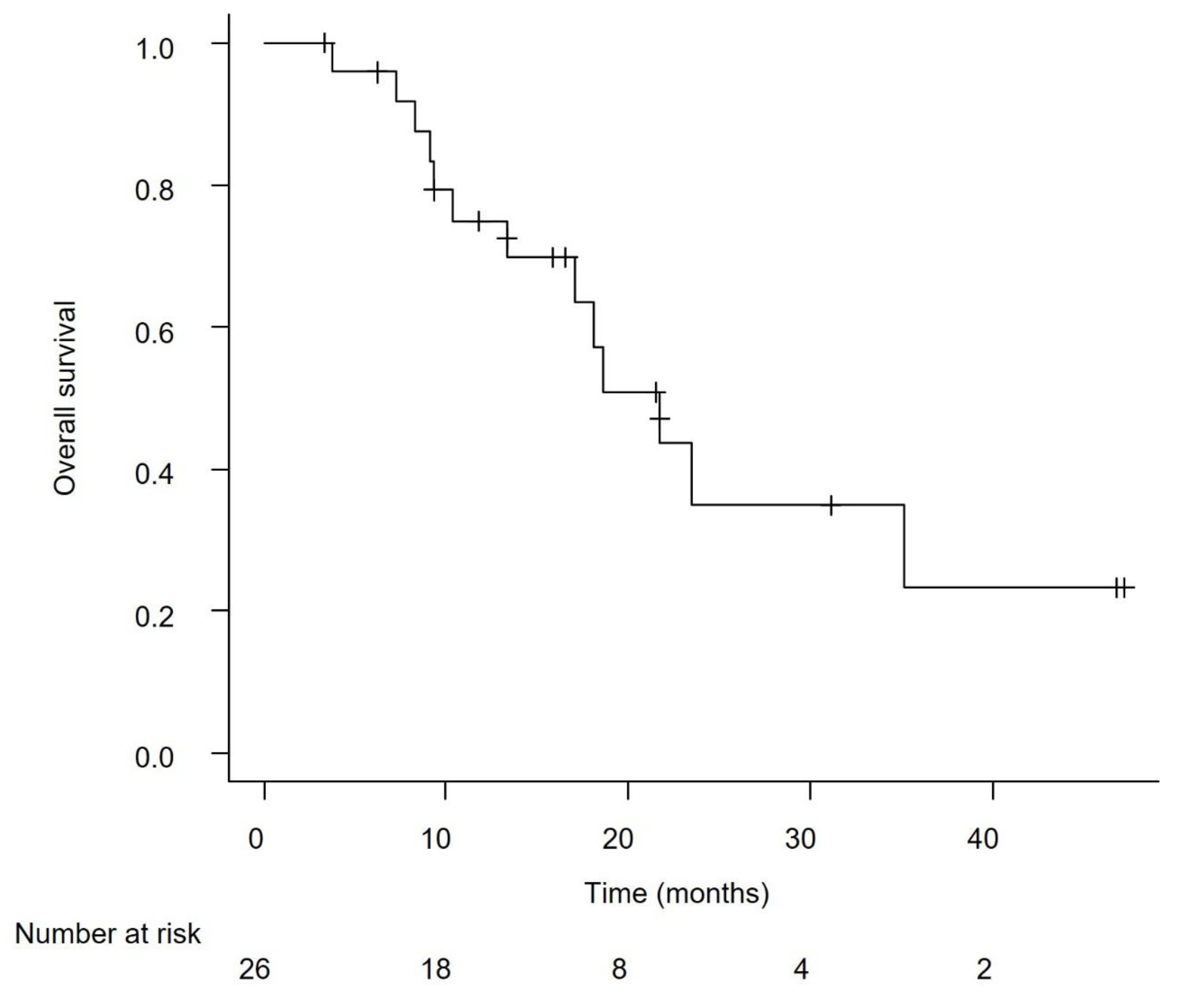

Efficacy in the Overall Cohort

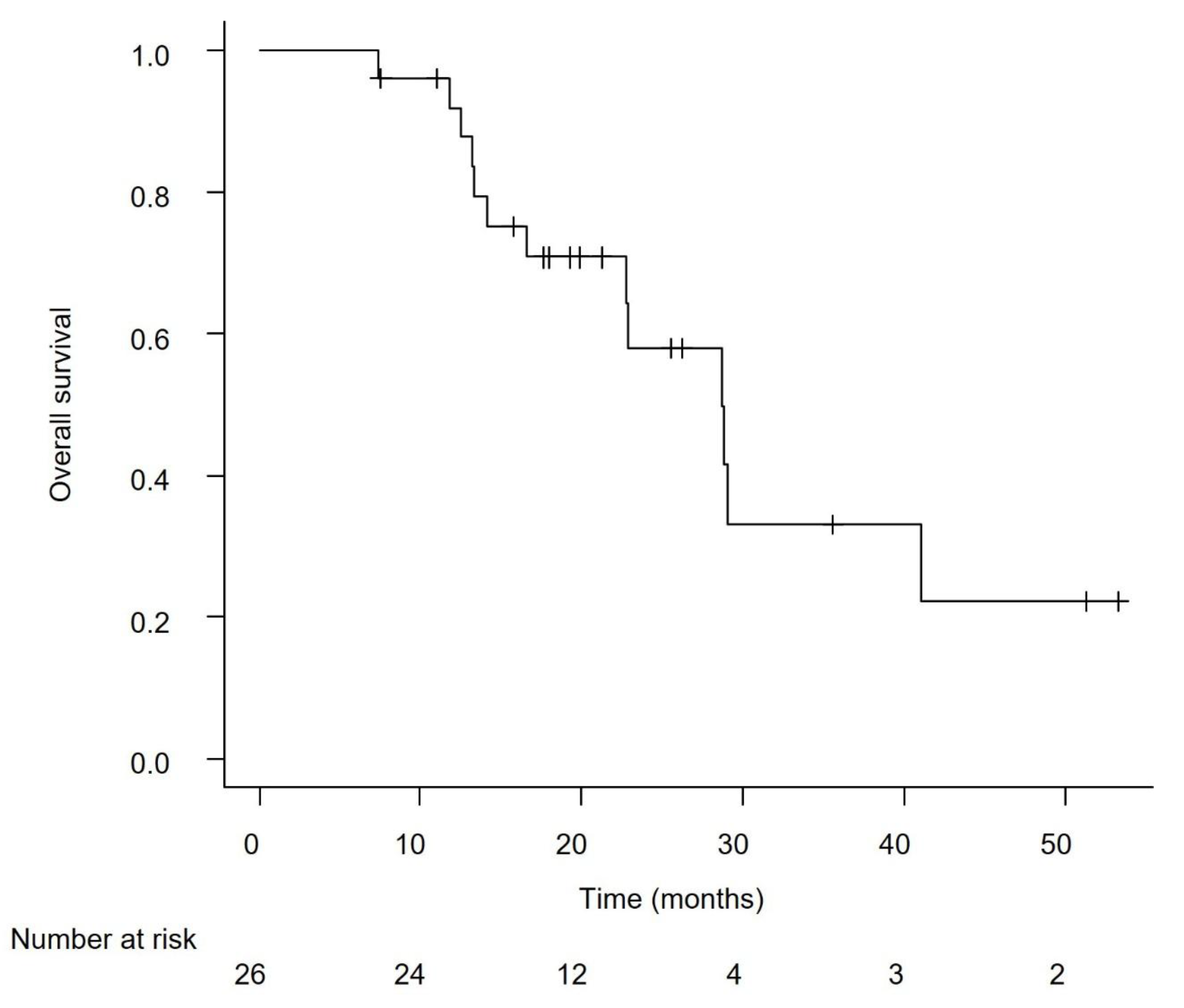

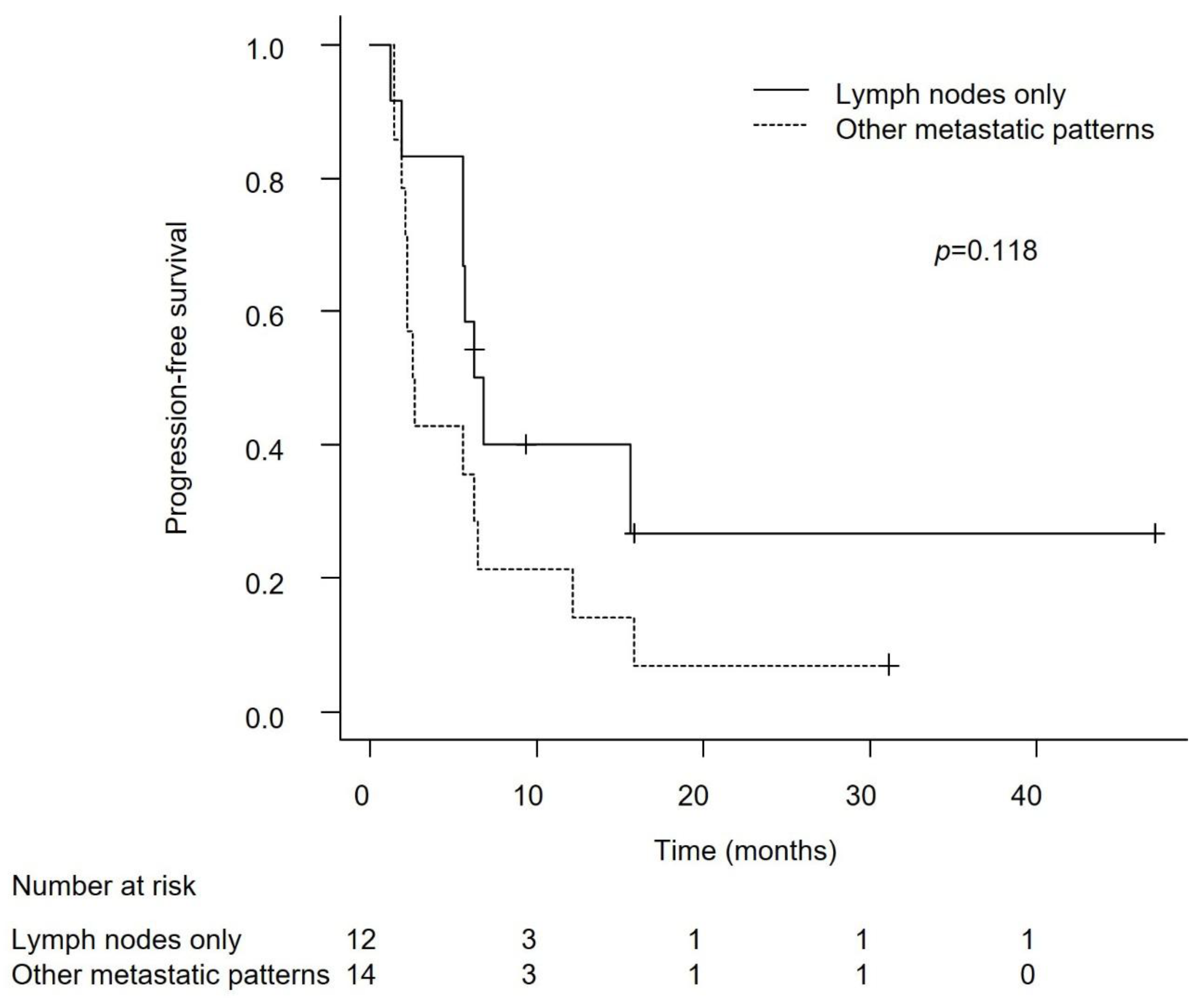

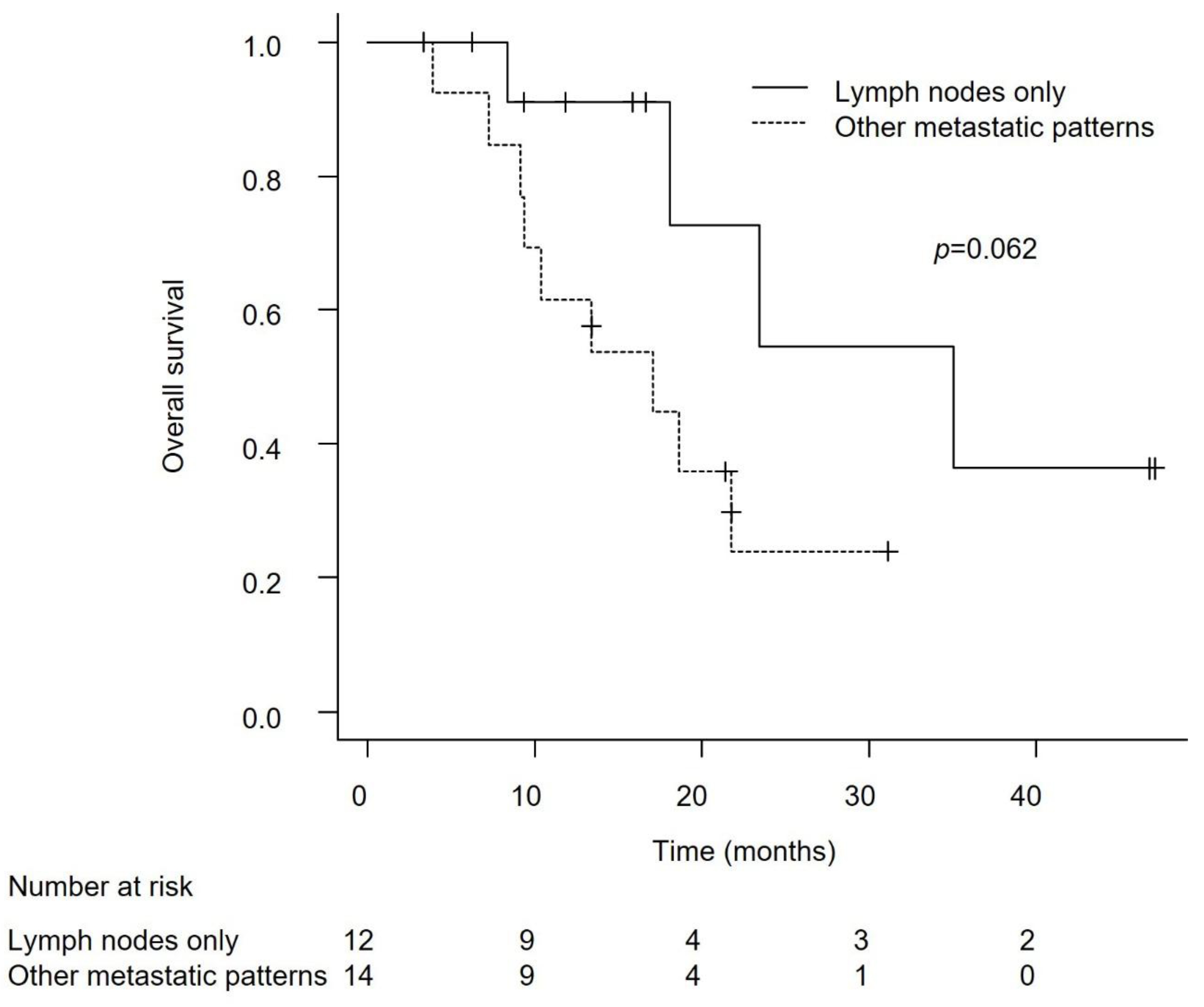

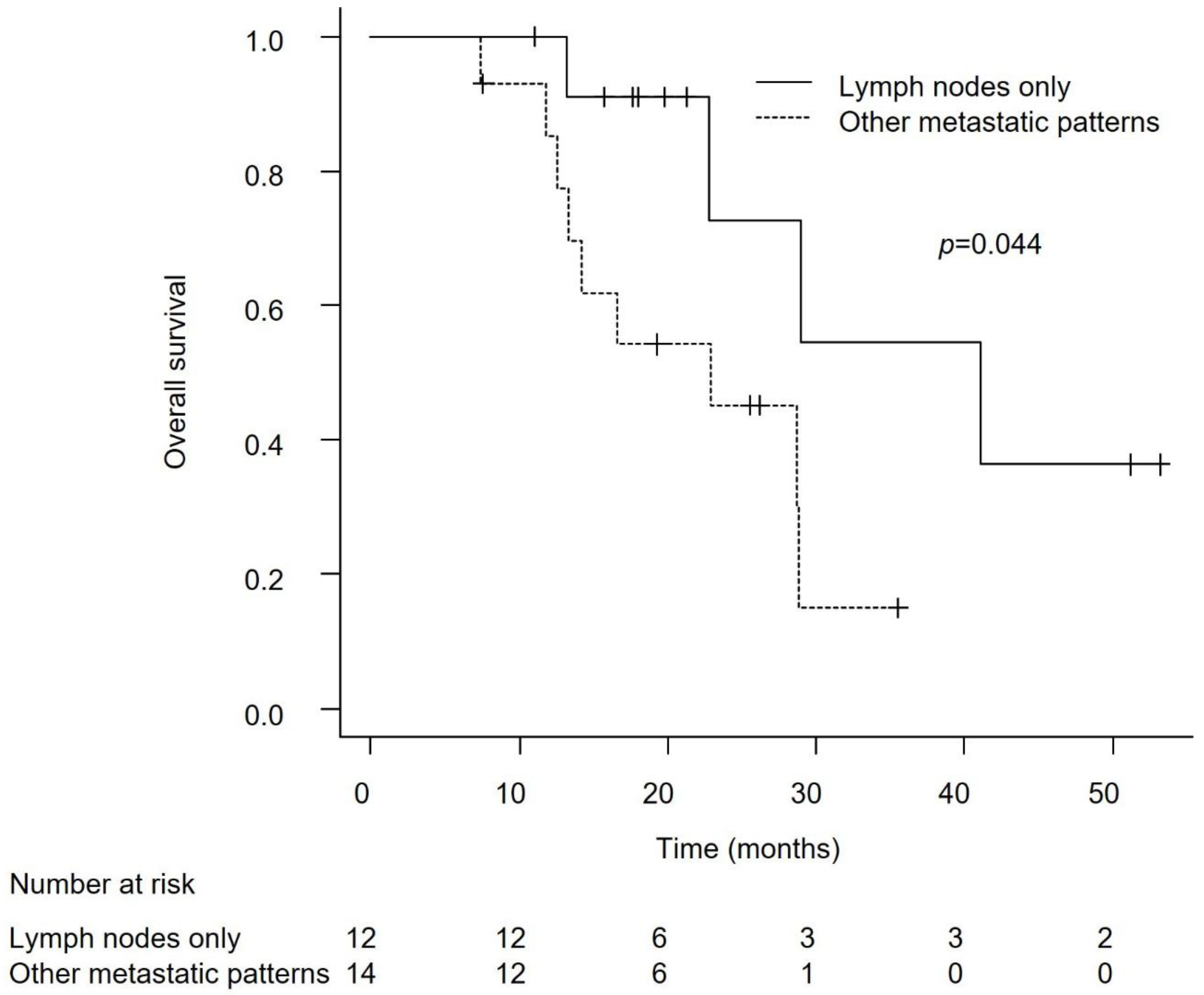

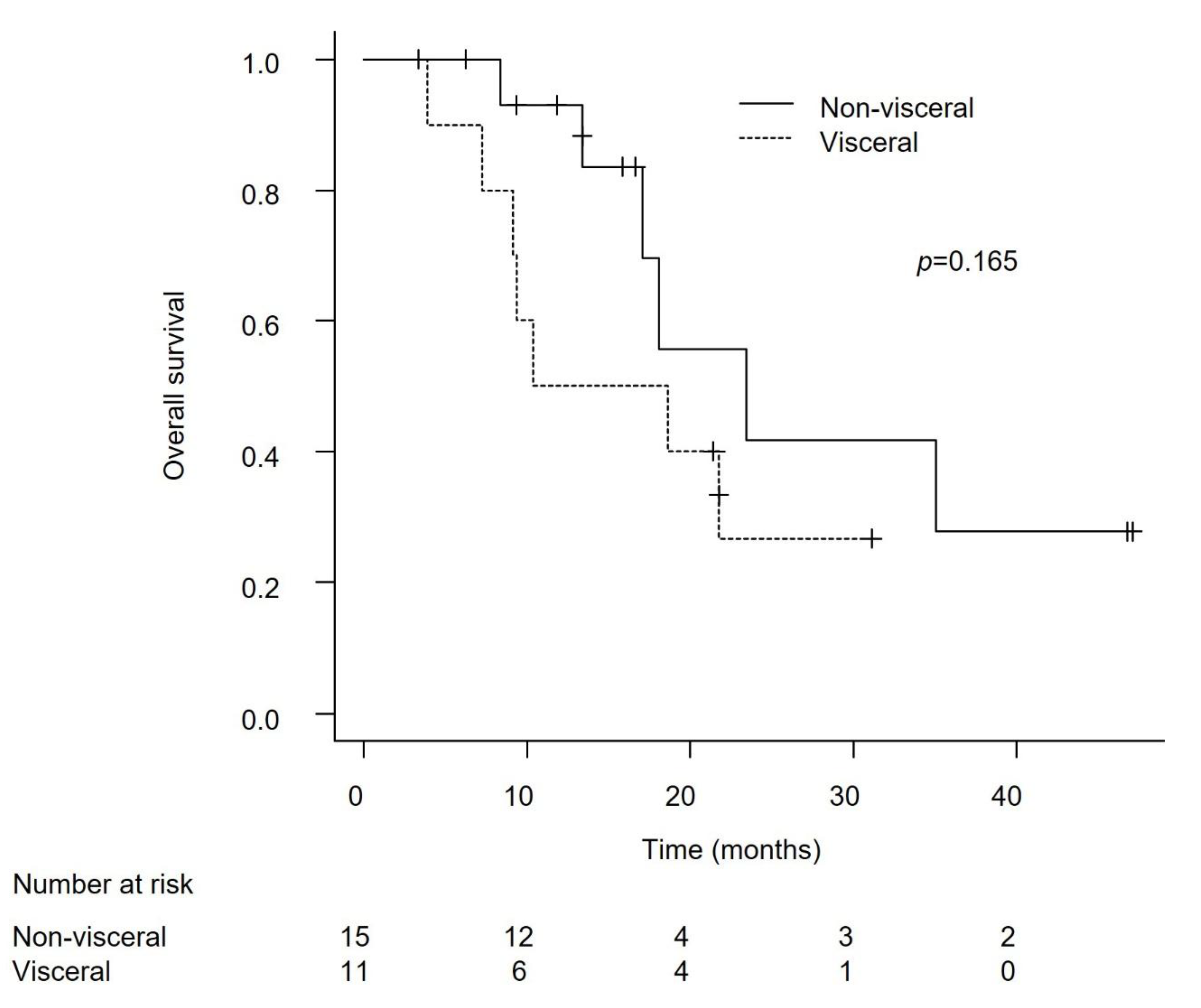

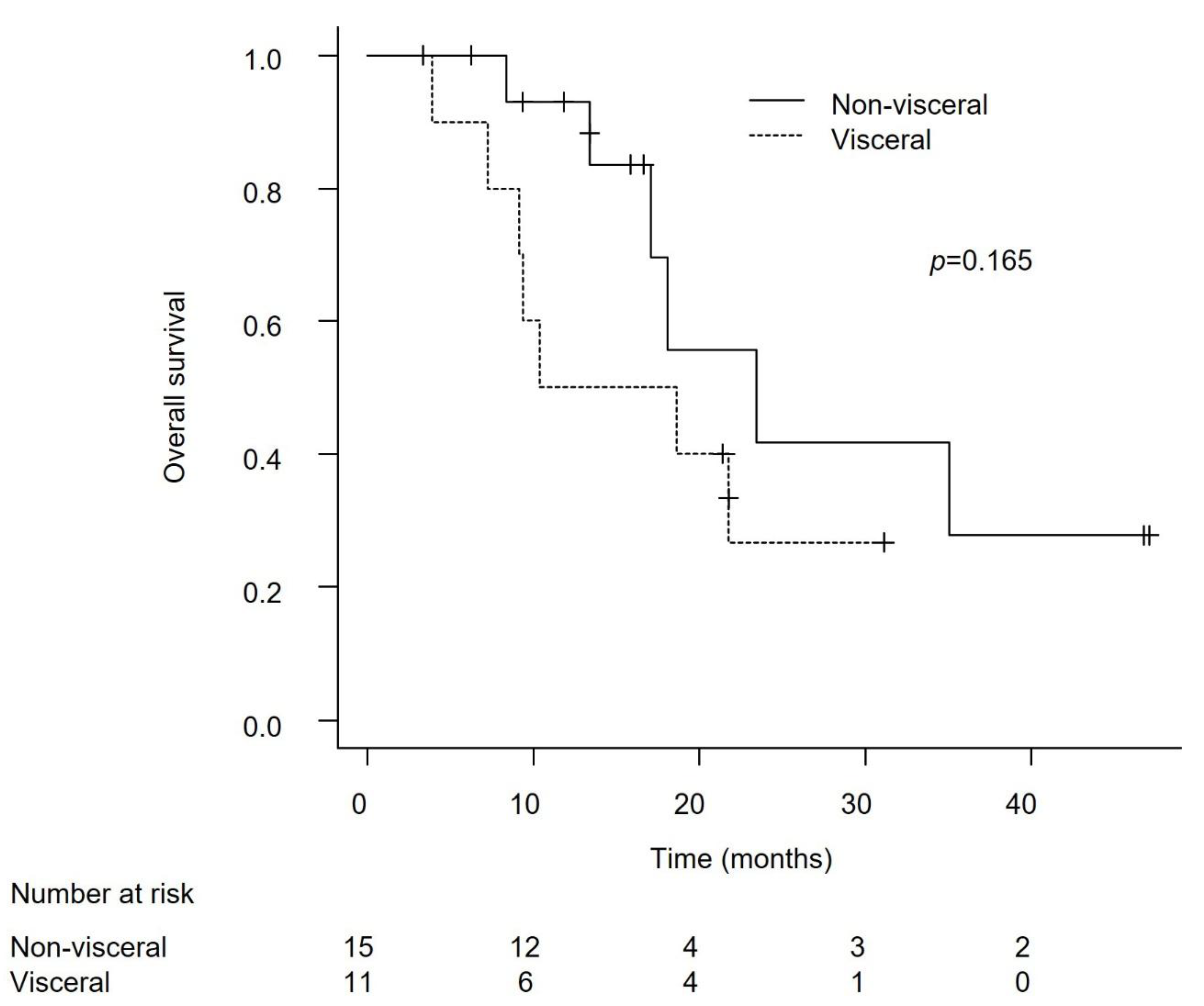

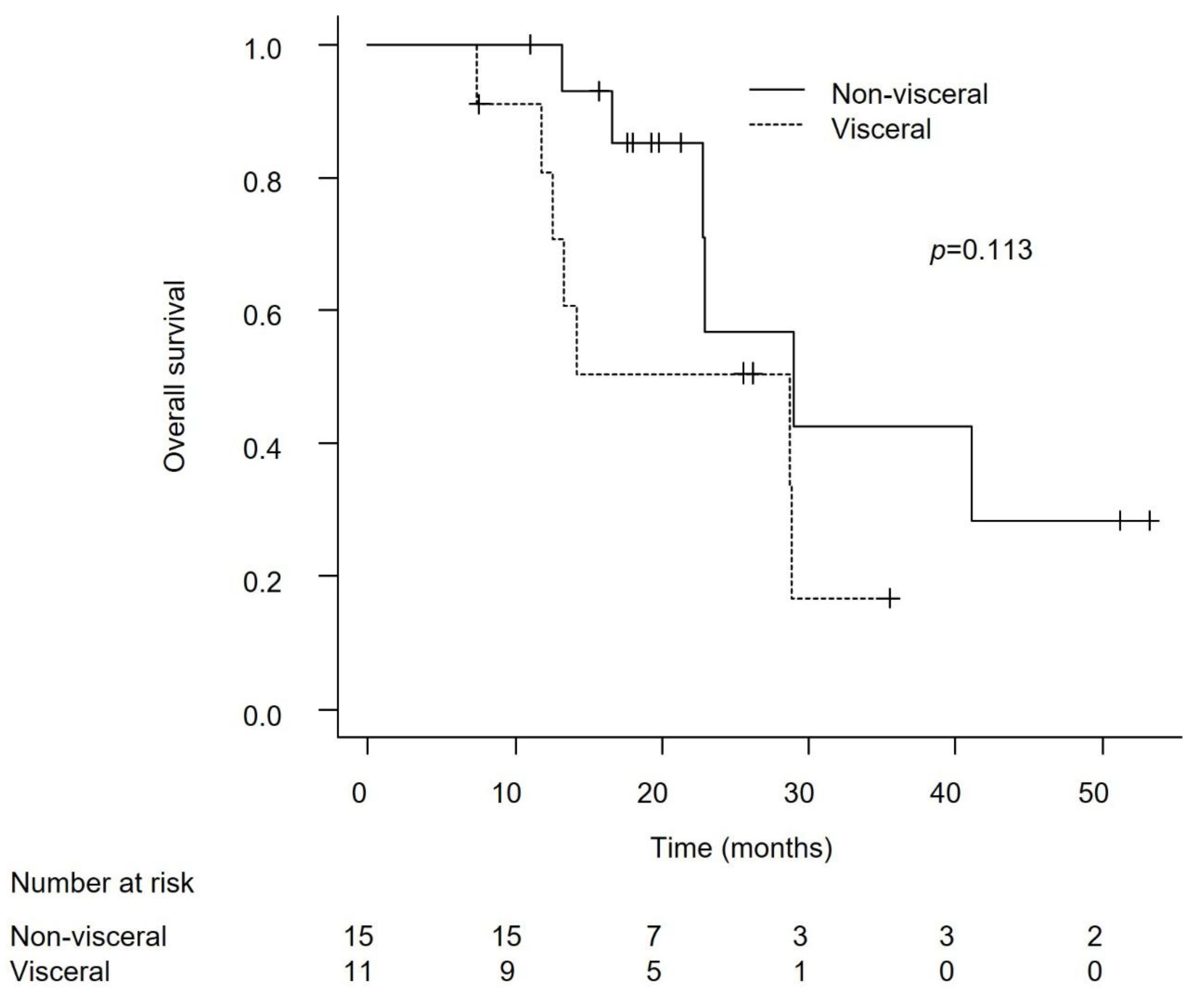

Efficacy in Patients with Lymph Node-Only Metastasis and Non-Visceral Metastasis

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Bladder Cancer; Version 1.2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Powles, T.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gupta, S.; Bedke, J.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Iyer, G.; Vulsteke, C.; Park, S.H.; Shin, S.J.; et al. Enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab in untreated advanced urothelial cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Sonpavde, G.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Burotto, M.; Schenker, M.; Sade, J.P.; Bamias, A.; Beuzeboc, P.; Bedke, J.; et al. Nivolumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin in advanced urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, E.; Hussain, S.A.; Barthélémy, P.; Kanesvaran, R.; Giannatempo, P.; Benjamin, D.J.; Hoffman, J.; Birtle, A. Individualizing first-line treatment for advanced urothelial carcinoma: A favorable dilemma for patients and physicians. Cancer Treat Rev. 2025, 134, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Ullén, A.; Loriot, Y.; Sridhar, S.S.; Sternberg, C.N.; Bellmunt, J.; et al. Avelumab first-line maintenance for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Results from the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial after ≥2 years of follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3486–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furubayashi, N.; Minato, A.; Tomoda, T.; Hori, Y.; Kiyoshima, K.; Negishi, T.; Haraguchi, Y.; Koga, T.; Kuroiwa, K.; Fujimoto, N.; et al. Organ-specific tumor response to avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective study. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 5689–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivas, P.; Huber, C.; Pawar, V.; Roach, M.; May, S.G.; Desai, I.; Chang, J.; Bharmal, M. Management of Patients With Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma in an Evolving Treatment Landscape: A Qualitative Study of Provider Perspectives of First-Line Therapies. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2022, 20, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.; Terada, N.; Saito, T.; Yokomizo, A.; Kohei, N.; Goto, T.; Kawamura, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Kimura, T.; et al. Differential prognostic factors in low- and high-burden de novo metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Arén Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.-N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélémy, P.; Loriot, Y.; Thibault, C.; Fléchon, A.; Voog, E.; Eymard, J.C.; Simon, C.; Gross-Goupil, M.; et al. AVENANCE real-world study of avelumab first-line maintenance treatment for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Analyses in low tumor burden subgroups. J Clin Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Théodore, C.; Demkov, T.; Komyakov, B.; Sengelov, L.; Daugaard, G.; Caty, A.; Carles, J.; Jagiello-Gruszfeld, A.; Karyakin, O.; et al. Phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone after a platinum-containing regimen in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27, 4454–4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsteinsson, K.; Brandt, S.B.; Jensen, J.B. Patients with metastatic or locally advanced bladder cancer not undergoing systemic oncological treatment—Characteristics and long-term outcome in a single-center Danish cohort. Cancers (Basel). 2025, 17, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivas, P.; Grande, E.; Davis, I.D.; Moon, H.H.; Grimm, M.-O.; Gupta, S.; Barthélémy, P.; Thibault, C.; Guenther, S.; Hanson, S.; et al. Avelumab first-line maintenance treatment for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Review of evidence to guide clinical practice. ESMO Open. 2023, 8, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Ullén, A.; Loriot, Y.; Sridhar, S.S.; Tsuchiya, N.; et al. Avelumab first-line maintenance for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Long-term outcomes from the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial in patients with nonvisceral or lymph node-only disease. Eur Urol. 0302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2025.43.5_suppl.664 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/visceral (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Cai, D.; Hong, S. Prevalence and prognosis of bone metastases in common solid cancers at initial diagnosis: A population-based study. BMJ Open. 2023, 13, e069908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrakis, D.; Talukder, R.; Lin, G.I.; Diamantopoulos, L.N.; Dawsey, S.; Gupta, S.; Carril-Ajuria, L.; Castellano, D.; de Kouchkovsky, I.; Koshkin, V.S.; et al. Association Between Sites of Metastasis and Outcomes With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2022, 20, e440–e452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruatta, F.; Derosa, L.; Escudier, B.; Colomba, E.; Guida, A.; Baciarello, G.; Loriot, Y.; Fizazi, K.; Albiges, L. Prognosis of renal cell carcinoma with bone metastases: Experience from a large cancer centre. Eur. J. Cancer. 2019, 107, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, M.; Santini, D.; Cursano, M.C.; Foderaro, S.; Tonini, G.; Procopio, G. Bone metastases from urothelial carcinoma: The dark side of the moon. J Bone Oncol. 2021, 31, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xie, C.; Li, Q.; Huang, X.; Huang, W.; Yin, D. Prognostic factors and nomogram for the overall survival of bladder cancer bone metastasis: A SEER-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e33275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Gu, H.; Zhang, D.; Wen, M.; Yan, Z.; Song, B.; Xie, C. Establishment and validation of a nomogram for predicting overall survival of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma with bone metastasis: A population-based study. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).