1. Introduction

Breast density is a well-recognized risk factor for breast cancer, correlating not only with increased malignancy risk but also with reduced sensitivity of conventional mammography [

1,

2]. Background parenchymal enhancement (BPE)—defined as the physiological uptake of contrast in non-pathological fibroglandular tissue—has emerged as a potential imaging biomarker in contrast-enhanced breast imaging. While extensively studied in breast MRI, the clinical significance of BPE remains controversial, with evidence pointing in divergent directions —some identifying it as a risk biomarker, others finding limited predictive value [

3,

4]. This underscores the importance of modality-specific classification systems that account for both technical constraints and interpretive requirements unique to CEM.

Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) is an emerging hybrid modality that com-bines anatomical and functional imaging, offering advantages over MRI such as greater accessibility, lower cost, and faster acquisition [

5,

6]. BPE can be visualized on CEM, but its assessment is complicated by the planar, two-dimensional nature of the modality, which lacks the volumetric and kinetic resolution available with MRI. Notably, pronounced BPE in CEM can mask lesions and reduce diagnostic accuracy [

7,

8]. Unlike breast density, which is systematically categorized via the ACR BI-RADS lexicon [

9], there is currently no standardized lexicon or scoring system for BPE in CEM, resulting in interpretive variability and limited comparability across studies.

The relationship between BPE and breast density remains controversial. Some evidence suggests a positive correlation [

10,

11], while other studies report no significant link [

12,

13]. These inconsistencies highlight the need for a dedicated classification system tailored specifically to the technical and interpretive characteristics of CEM. Importantly, existing BPE grading schemes developed for MRI—such as that by Sorin et al. [

9]—are based on volumetric and temporal contrast dynamics not available in CEM, making direct transposition impractical.

Unlike MRI-based frameworks, the Breast Contrast Standard Scale (BCSS) was developed specifically for CEM. It defines enhancement based on semi-quantitative thresh-olds of parenchymal involvement (e.g., <10% for Minimal), complemented by anatomical criteria such as masking of ducts and vessels. This modality-specific approach reflects the practical constraints of CEM interpretation and offers a novel step toward standardizing BPE assessment in clinical and research settings.

Recent advances in this field have also led to ongoing investigations exploring artificial intelligence—particularly neural networks—to enhance standardization and reduce variability in the assessment of BPE and breast density. Preliminary results from a complementary study using AI have shown promising improvements in assisting radiologists with borderline BI-RADS C and D cases, where inter-reader variability is greatest. Methodological details and early findings from this AI-based approach are reported separately and will support the clinical integration of such tools.

This study evaluates the relationship between breast density and background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) in contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) and introduces the Breast Contrast Standard Scale (BCSS)—a four-level classification system (Minimal, Light, Moderate, Marked) designed to standardize BPE reporting in CEM.

The BCSS adapts MRI-derived grading concepts to the constraints of CEM by integrating enhancement thresholds and anatomical distribution criteria suitable for planar imaging. Specifically, the scale combines semi-quantitative estimates of parenchymal enhancement (e.g., <10% for Minimal) with anatomical markers such as the masking of ducts or vascular structures.

The BCSS aims to:

Improve inter-reader agreement in BPE interpretation on CEM;

Enable reproducible comparisons across imaging studies and centers;

Facilitate the inclusion of BPE in structured breast cancer risk stratification frameworks.

This classification system represents a clinically relevant step toward reducing subjectivity in CEM interpretation and may support both diagnostic accuracy and personalized screening strategies for women with dense breasts.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective single-center study was conducted at the Interventional Senology Unit of P.O. "A. Perrino" Hospital, Brindisi, Italy, from May 2022 to June 2023, fol-lowing Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Among 314 initially evaluated patients, 213 women aged 28–80 years met inclusion criteria. Eligible subjects presented with suspicious breast lesions classified as BI-RADS 4 or 5 on CEM and underwent complete di-agnostic workup including ultrasound (US), conventional mammography (MG), and contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) prior to biopsy and histological confirmation of invasive breast cancer. Due to its retrospective nature, no additional consent beyond routine imaging authorization was required.

Clinical and imaging data were entered into three structured relational databases: demographics (patient ID, birth date), imaging parameters (breast density per ACR BI-RADS A-D, BPE categories Minimal/Light/Moderate/Marked, completion status of US, MG, and CEM), and morphometric glandular measurements in millimeters across four fields.

Inclusion: Women ≥18 years with suspicious findings (BI-RADS 4 or 5) on CEM.

Exclusion: Contrast contraindications (pregnancy, allergy, renal insufficiency per ESUR guidelines), prior breast cancer, breast implants, ongoing neoadjuvant therapy, incomplete imaging, absent histologic confirmation, or biopsy/radiotherapy within 21 days before CEM.

CEM Protocol

Contrast Administration

After screening for contraindications, Iohexol 350 mg I/ml (Omnipaque®) was injected intravenously at 1.5 ml/kg via 20-gauge catheter at 3 ml/s, followed by 20 ml sa-line flush.

CEM was performed using a full-field digital mammography system (Senographe Pristina with SenoBright® software). Bilateral craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views were acquired under compression. Each breast was imaged using low-energy (26–31 keV) and high-energy (45–49 keV) exposures, beginning 2 minutes post-injection, with acquisition lasting ~1.5 seconds per view. Total exam time was under 7 minutes. Images were recombined to produce subtraction images for BPE evaluation.

Breast density was assessed on low-energy images using ACR BI-RADS v5 criteria [

9]. BPE was evaluated on recombined subtraction images using the newly proposed BPE-CEM Standard Scale (BCSS), which defines four BPE levels based on semi-quantitative and qualitative criteria:

Minimal (MIN): <10% of visible fibroglandular tissue enhanced, faint enhancement not obscuring ducts/vessels.

Light (LIE): 10–25% enhancement, mild masking but key anatomical landmarks visible.

Moderate (MOD): 25–50% enhancement, partial overlap/obscuration of ducts, vessels, and glandular architecture, potentially interfering with le-sion visibility.

Marked (MAR): >50% enhancement, strong masking/obscuration complicating lesion detection.

Experienced breast radiologists visually estimated enhancement extent via standardized scoring sheets, cross-referencing low-energy images to define glandular boundaries. This combined quantitative and anatomical approach aims to enhance reproducibility tailored to CEM’s 2D nature.

Data were managed using a relational database management system (DBMS) to minimize redundancy and ensure consistency. Descriptive statistics summarized patient age, BPE, and breast density distributions. Lesion size comparisons were per-formed using the Bland-Altman method. A multiple linear regression analysis was performed with BPE as the dependent variable and breast density and age as independent predictors, in order to assess their explanatory power.

To further evaluate reproducibility, interobserver agreement was assessed by having three expert breast radiologists (each with over 10 years of experience in breast imaging) independently evaluate a randomized subset of 50 cases. Each radiologist as-signed BPE scores according to the newly proposed Breast Contrast Standard Scale (BCSS). Agreement among readers was quantified using Cohen’s kappa statistic and interpreted based on Landis and Koch criteria

Table 1.

Age group, record number, percentage, and density distribution by BPE.

Table 1.

Age group, record number, percentage, and density distribution by BPE.

| Age Group |

Number of Record (out of 268) |

Percentage |

BPE |

Notes on Density |

| 25-40 |

11 |

5% |

MIN/LIE |

|

| 25-40 |

2 |

1% |

MOD/MAR |

No A and no D |

| 41-55 |

80 |

38% |

MIN/LIE |

|

| 41-55 |

13 |

6% |

MOD/MAR |

No A |

| Over 55 |

97 |

46% |

MIN/LIE |

|

| Over 55 |

9 |

4% |

MOD/MAR |

No A, one B and one D |

| |

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Count of records by letter, with percentages and details on the S value.

Table 2.

Count of records by letter, with percentages and details on the S value.

| Letter |

Count |

Percentage (%) |

Null Values |

Details on S Value |

| A |

18 |

14% |

13 |

3 records with S < -2, 2 with S > 2 |

| B |

47 |

36% |

31 |

7 records with S < -2, 8 with S > 2 |

| C |

40 |

31% |

25 |

7 records with S < -2, 7 with S > 2 |

| D |

25 |

19% |

14 |

7 records with S < -2, 3 with S > 2 |

| |

|

|

|

|

3. Results

Patient Age Distribution

The study population ranged from 28 to 79 years, with a peak incidence around age 60—consistent with typical breast imaging cohorts.

BPE Categorization

Among the 211 patients included:

Minimal BPE: 57%

Light BPE: 31%

Moderate BPE: 10%

Marked BPE: 2%

This distribution reflects a predominance of low-grade enhancement in the study population.

Interobserver Agreement

BPE classification using the BCSS showed near-perfect interobserver agreement, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.92). This supports the reproducibility and operational feasibility of the proposed scale.

Breast Density and Imaging Modality

A total of 313 imaging studies (pre- and post-contrast) were analyzed:

Non-contrast (based on low-energy images): 11% A, 29% B, 26% C, 17% D.

Contrast-enhanced (CEM): 1% A, 7% B, 4% C, 4% D.

This contrast-induced shift in perceived density likely reflects enhanced visualization of fibroglandular tissue, a known phenomenon in contrast-based breast imaging.

Age-Based Stratification of BPE

BPE showed an inverse relationship with age:

Age 25–40: 5% Minimal/Light, 1% Moderate/Marked.

Age 41–55: 38% Minimal/Light, 6% Moderate/Marked.

Age >55: 46% Minimal/Light, 4% Moderate/Marked.

These findings align with physiological estrogen decline and support previously described age-dependent trends in background enhancement.

S Metric Analysis

The S-value, a derived morphometric index, showed variability across breast density types, especially in intermediate categories:

Density A: 14% of cases; 3 with S < -2, 2 with S > 2.

Density B: 36%; 7 with S < -2, 8 with S > 2.

Density C: 31%; 7 each with S < -2 and S > 2.

Density D: 19%; 7 with S < -2, 3 with S > 2.

These findings suggest intra-group heterogeneity, indicating that glandular morphology may add nuance to standard density classifications.

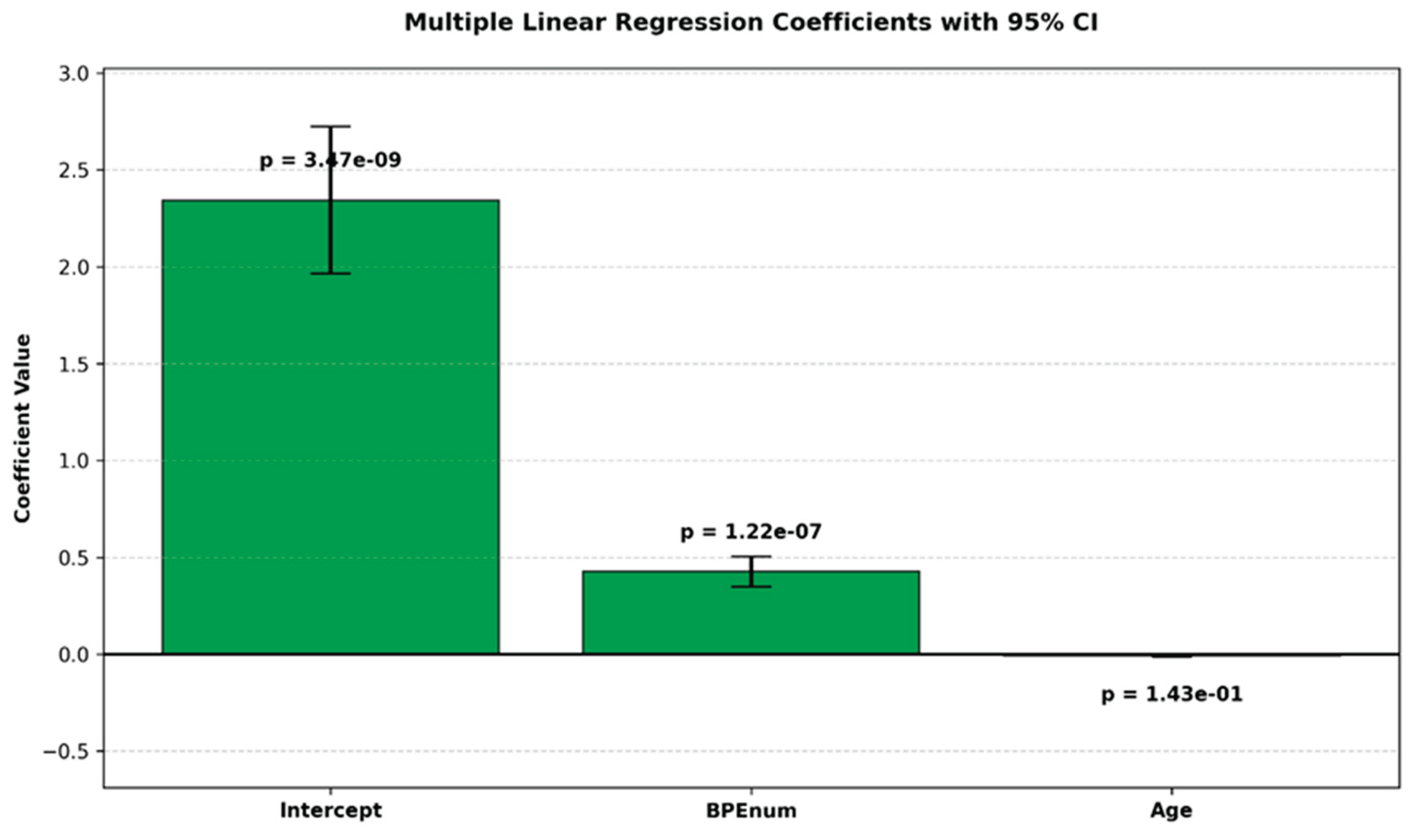

Regression Analysis

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between breast density, BPE, and age:

Multiple R: 0.38 (moderate correlation)

R²: 0.144 (14.4% of variance explained)

Adjusted R²: 0.136

Standard error: 0.8639

BPE showed a statistically significant positive association with breast density (p < 0.05)

Age was not a significant predictor (p = 0.14)

Although BPE shows a statistically significant correlation with breast density (p < 0.05), the relatively low R² value (0.144) indicates modest predictive power, suggesting that additional nonlinear or latent variables likely influence BPE. Notably, a complementary analysis conducted on the same dataset—reported separately in another manuscript—demonstrated that a neural network model achieved a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.691, outperforming the regression model's standard error of 0.8639. This finding supports the potential of deep learning approaches to capture nonlinear interactions more effectively and warrants further investigation.

Figure 1.

Bar plot of estimated coefficients from a multiple linear regression model with 95% confidence intervals. p-values are shown above each bar.

Figure 1.

Bar plot of estimated coefficients from a multiple linear regression model with 95% confidence intervals. p-values are shown above each bar.

Table 3.

This table presents the results of the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) for the regression model. The table shows the de-grees of freedom (df), sum of squares (SS), mean square (MS), F-statistic, and significance value for the regression and residual components, along with the total sum of squares. The very low significance F (7.86E-08) indicates that the model is statistically significant.

Table 3.

This table presents the results of the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) for the regression model. The table shows the de-grees of freedom (df), sum of squares (SS), mean square (MS), F-statistic, and significance value for the regression and residual components, along with the total sum of squares. The very low significance F (7.86E-08) indicates that the model is statistically significant.

| ANOVA ( Analysis of Variance) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Source |

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

| Regression |

2 |

26.42365998 |

13.21182999 |

17.70217459 |

7.8594E-08 |

| Residual |

210 |

156.7312696 |

0.746339379 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

212 |

183.1549296 |

|

|

|

Table 4.

The table reports the estimated coefficients, standard errors, t-statistics, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals for the model parameters.

Table 4.

The table reports the estimated coefficients, standard errors, t-statistics, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals for the model parameters.

| |

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

p-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

Lower 95.0% |

Upper 95.0% |

| Intercept |

2.343692153 |

0.379884019 |

6.169493937 |

3.47353E-09 |

1.594817367 |

3.092566939 |

1.594817367 |

3.092566939 |

| BPEnum |

0.426517913 |

0.077858245 |

5.478134158 |

1.22301E-07 |

0.273034024 |

0.580001803 |

0.273034024 |

0.580001803 |

| Age |

0.008787179 |

0.005970236 |

1.471831024 |

0.14256352 |

0.020556454 |

0.002982096 |

0.020556454 |

0.002982096 |

4. Discussion

The interplay between background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) and breast density has been extensively investigated in the literature, yet remains controversial, with conflicting evidence regarding their correlation and individual roles in breast cancer risk stratification [

22,

23]. BPE, initially described in contrast-enhanced breast MRI, reflects physiologic contrast uptake in non-pathologic fibroglandular tissue and is influenced by hormonal status, vascular perfusion, and parenchymal composition [

24]. While several studies have proposed BPE as an independent imaging biomarker for breast cancer risk, findings have been inconsistent or inconclusive [

25].

Breast density, by contrast, is a well-established and independent risk factor for breast cancer. Dense breast tissue not only correlates with increased malignancy rates but al-so reduces the sensitivity of standard mammography [

26,

27]. However, the relation-ship between BPE and density—particularly in the setting of contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM)—remains poorly defined. One major challenge is the absence of a standardized BPE classification system tailored specifically for CEM, unlike MRI which benefits from a well-established volumetric lexicon [

28,

29,

30].

CEM is increasingly recognized as a clinically valuable alternative to breast MRI, combining anatomical and functional information with greater accessibility and shorter acquisition times. However, BPE as visualized in CEM differs from MRI due to the modality's planar, two-dimensional nature and its reliance on recombined subtraction imaging. These technical differences complicate BPE interpretation and reduce reproducibility across clinical settings. Additionally, whereas breast density is categorized systematically using the ACR BI-RADS lexicon, no universally accepted classification currently exists for BPE in CEM, contributing to interpretive variability and limiting research comparability.

Our study addresses this gap by introducing the BPE-CEM Standard Scale (BCSS), a novel four-level classification (Minimal, Light, Moderate, Marked) based on semi-quantitative enhancement thresholds and anatomical criteria. This modality-specific scale is designed to standardize BPE assessment within the constraints of CEM’s 2D imaging format.

Preliminary data from a subsequent analysis on the same dataset suggest that artificial intelligence (AI), particularly neural networks, can reduce interobserver variability in cases with borderline BI-RADS classifications (C and D), where subjectivity is most pronounced. The lower MAE observed with neural networks indicates improved predictive precision over traditional linear regression models, aligning with the established utility of backpropagation and gradient-based optimization in modeling complex biomedical data. These findings resonate with the foundational work of Rosen-blatt (1958), Rumelhart et al. (1986), and Goodfellow et al. (2016), which collectively underscore the power of iterative weight optimization via backpropagation in enhancing predictive accuracy.

Taken together, these findings reinforce the importance of a standardized BPE lexicon tailored to CEM and open promising avenues for the integration of AI in breast imaging protocols. Further validation is needed, but this dual approach—structural standardization through BCSS and variability reduction via AI—may significantly improve diagnostic reproducibility in women with dense breasts.

Key Findings

BPE distribution: Minimal in 57% of patients, Light in 31%, Moderate in 10%, and Marked in 2%.

Density correlation: Higher breast density categories (BI-RADS C–D) were significantly associated with Moderate-to-Marked BPE, whereas lower densities (A–B) correlated with Minimal-to-Light BPE (p < 0.05).

Regression analysis: Demonstrated a statistically significant association between BPE and breast density (R² = 0.144), with a moderate multiple correlation coefficient (R = 0.38). Age was not a significant predictor (p = 0.14).

Interobserver agreement: The BCSS showed excellent reproducibility, with Co-hen’s κ = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.92), supporting its feasibility and consistency in clinical practice.

Although the regression model confirmed a statistically significant relationship be-tween BPE and breast density, the relatively low R² value indicates that BPE explains only a modest portion of the variance in breast density. This suggests that other, possibly nonlinear or latent factors—such as hormonal therapy, menopausal status, BMI, or genetic predisposition—may influence enhancement and should be incorporated into future predictive models.

Moreover, the standard error (0.8639) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) reflect residual variance, further highlighting the model’s limited predictive accuracy. While the mod-el was statistically significant overall (F-statistic: 17.70, p < 0.001), the predictive contribution of individual variables remains modest.

The proposed BCSS offers a practical solution for harmonizing BPE assessment in CEM. Unlike MRI-based systems that rely on volumetric and temporal enhancement criteria, the BCSS adapts semi-quantitative thresholds to the two-dimensional nature of CEM and incorporates anatomical indicators such as ductal and vascular masking.

For instance, “Moderate” BPE in CEM refers to enhancement of 25–50% of fibroglandular tissue with partial obscuration of key structures, which—despite lacking volumetric context—may still compromise lesion visibility in planar imaging. This distinction is critical for aligning classification with diagnostic performance in CEM.

The high interobserver agreement observed in our study confirms the reliability of the BCSS, suggesting that it may enhance both diagnostic consistency and research comparability across institutions. However, its clinical utility remains to be confirmed through multicenter, prospective validation studies encompassing diverse patient populations and imaging platforms.

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective, single-center design may limit generalizability. Additionally, the lack of clinical data on hormonal status, BMI, menstrual cycle phase, and endocrine therapies restricted our ability to account for con-founding variables that may influence BPE. Moreover, the study population was drawn from a diagnostic rather than a screening cohort, potentially affecting the applicability of findings to broader populations. All imaging was also acquired using a single CEM device (GE Senographe Pristina) and a fixed contrast protocol, which may limit reproducibility across different vendors or acquisition settings.

To strengthen the clinical impact of the BCSS and deepen understanding of BPE's biological and imaging correlates, future research should focus on:

Prospective, multicenter validation of the BCSS across different imaging plat-forms;

Integration of AI-based tools for objective, automated quantification of BPE, reducing reader subjectivity;

Incorporation of hormonal, genetic, and physiological variables into risk prediction models;

Application of machine learning and deep learning methods to uncover complex, nonlinear associations and enhance predictive accuracy.

In particular, neural networks may minimize prediction error (e.g., MAE), uncover la-tent patterns, and improve the integration of BPE into individualized risk models and screening pathways—especially in women with dense breasts, where conventional mammography is limited. This study represents an initial step toward future quantitative standardization of BPE assessment; however, it does not yet incorporate advanced predictive modeling, which will be addressed in separate analyses.

5. Conclusions

In the context of contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM), background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) remains a clinically significant but poorly standardized imaging feature. Our proposed BPE-CEM Standard Scale (BCSS) provides a structured, modality-specific framework aimed at enhancing the consistency and reproducibility of BPE assessment, particularly in women with dense breasts where diagnostic interpretation is most challenging.

While our results confirm a modest correlation between breast density and BPE, the limited explanatory power of linear models underscores the complexity of this relationship. This highlights the need for innovative methodologies capable of capturing the intricate interplay between tissue composition and enhancement patterns.

Preliminary investigations utilizing artificial intelligence (AI), including neural networks, demonstrate promising potential to reduce interobserver variability and support radiologists in borderline cases. Although these computational approaches require further validation, they offer valuable tools to improve diagnostic consistency and enable personalized risk stratification.

Future research should focus on integrating probabilistic AI models with multi-modal data—encompassing hormonal, genetic, and physiological factors—within predictive frameworks. Such integration would enhance both the interpretability and clinical utility of BPE as an imaging biomarker. Crucially, these technological advancements should function as adjuncts, augmenting rather than replacing the expert judgment of experienced radiologists.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used: “Conceptualization Di Grezia G. and Nazzaro A.; methodology Cisternino E.; software, Nazzaro A.; validation, Gatta G, Cuccurullo V; formal analysis, Gatta G; investigation, Di Grezia G and Sica G.; resources, Nazzaro A; data curation, Di Grezia G; writing—original draft preparation, Di Grezia G and Schiavone L.; writing—review and editing, Di Grezia G and Schiavone L.; visualization, Gatta G; supervision, Gatta G and Scaglione M.; project administration, Cuccurullo V. All authors have read and agreed to the pub-lished version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPE |

Background Parenchymal Enhancement |

| CEM |

Contrast-Enhanced Mammography |

| BCSS |

BPE-CEM Standard Scale |

| BI-RADS |

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| DBMS |

Database Management System |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| |

|

References

- Bodewes FTH, van Asselt AA, Dorrius MD, Greuter MJW, de Bock GH. Mammographic breast density and the risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast. 2022 Dec;66:62-68. [CrossRef]

- Michaels E, Worthington RO, Rusiecki J. Breast Cancer: Risk Assessment, Screening, and Primary Prevention. Med Clin North Am. 2023 Mar;107(2):271-284.

- Magni V, Cozzi A, Muscogiuri G, Benedek A, Rossini G, Fanizza M, Di Giulio G, Sardanelli F. Background parenchymal enhancement on contrast-enhanced mammography: associations with breast density and patient's characteristics. Radiol Med. 2024 Sep;129(9):1303-1312. [CrossRef]

- Sorin V, Yagil Y, Shalmon A, Gotlieb M, Faermann R, Halshtok-Neiman O, Sklair-Levy M. Background Parenchymal En-hancement at Contrast-Enhanced Spectral Mammography (CESM) as a Breast Cancer Risk Factor. Acad Radiol. 2020 Sep;27(9):1234-1240. [CrossRef]

- Moffa G, Galati F, Maroncelli R, Rizzo V, Cicciarelli F, Pasculli M, Pediconi F. Diagnostic Performance of Contrast-Enhanced Digital Mammography versus Conventional Imaging in Women with Dense Breasts. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Jul 28;13(15):2520. [CrossRef]

- Taylor DB, Kessell MA, Parizel PM. Contrast-enhanced mammography improves patient access to functional breast imaging. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2024 Oct 31. [CrossRef]

- Watt GP, Keshavamurthy KN, Nguyen TL, Lobbes MBI, Jochelson MS, Sung JS, Moskowitz CS, Patel P, Liang X, Woods M, Hopper JL, Pike MC, Bernstein JL. Association of breast cancer with quantitative mammographic density measures for women receiving contrast-enhanced mammography. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Apr 30;8(3):pkae026. [CrossRef]

- Karimi Z, Phillips J, Slanetz P, Lotfi P, Dialani V, Karimova J, Mehta T. Factors Associated With Background Parenchymal Enhancement on Contrast-Enhanced Mammography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021 Feb;216(2):340-348. [CrossRef]

- van Nijnatten TJA, Morscheid S, Baltzer PAT, Clauser P, Alcantara R, Kuhl CK, Wildberger JE. Contrast-enhanced breast imaging: Current status and future challenges. Eur J Radiol. 2024 Feb;171:111312. [CrossRef]

- Meucci R, Pistolese CA, Perretta T, Vanni G, Beninati E, DI Tosto F, Serio ML, Caliandro A, Materazzo M, Pellicciaro M, Buonomo OC. Background Parenchymal Enhancement in Contrast-enhanced Spectral Mammography: A Retrospective Analysis and a Pictorial Review of Clinical Cases. In Vivo. 2022 Mar-Apr;36(2):853-858.

- Miller MM, Mayorov S, Ganti R, Nguyen JV, Rochman CM, Caley M, Jahjah J, Repich K, Patrie JT, Anderson RT, Harvey JA, Rooney TB. Patient Experience of Women With Dense Breasts Undergoing Screening Contrast-Enhanced Mammography. J Breast Imaging. 2024 May 27;6(3):277-287. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara F, Santonocito A, Vogel W, Trombadori C, Zarcaro C, Weber M, Kapetas P, Helbich TH, Baltzer PAT, Clauser P. Background parenchymal enhancement in CEM and MRI: Is there always a high agreement? Eur J Radiol. 2024 Dec 25;183:111903.

- Nicosia L, Mariano L, Mallardi C, Sorce A, Frassoni S, Bagnardi V, Gialain C, Pesapane F, Sangalli C, Cassano E. Influence of Breast Density and Menopausal Status on Background Parenchymal Enhancement in Contrast-Enhanced Mammography: Insights from a Retrospective Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Dec 24;17(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Freer PE. Mammographic breast density: impact on breast cancer risk and implications for screening. Radiographics. 2015 Mar-Apr;35(2):302-15. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka M. Mammographic Density for Personalized Breast Cancer Risk. Radiology. 2023 Feb;306(2):e222129. [CrossRef]

- Harrington J.L., Relational Database Design and Implementation, Morgan Kaufmann, 2016.

- Date C.J., An Introduction to Database Systems, Addison-Wesley, 2004.

- Taipalus T., Database management system performance comparisons: A systematic literature review, The Journal of Systems & Software, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bland J.M., Altman D.G., Comparing methods of measurement: why plotting difference against standard method is mis-leading, The Lancet, 346(8982), 1085-1087, 1995.

- Lantz B., Machine Learning con R. Conoscere le tecniche per costruire modelli predittivi, Apogeo editore, 2020.

- Draper N.R., Smith H., Applied Regression Analysis, Wiley-Interscience, 2014.

- Altman D.G., Practical Statistics for Medical Research, Chapman & Hall, 1991.

- Neter J., Wassermann W., Kutner M.H., Applied Linear Statistical Models, McGraw-Hill Education (ISE Editions), 1996.

- Kim G., Mehta TS., Brook A., Du LH., Legare K., Phillips J., Enhancement Type at Contrast-enhanced Mammography and Association with Malignancy, Radiology, 2022 Nov;305(2):299-306. [CrossRef]

- Hafez MAF., Zeinhom A., Hamed DAA., Ghaly GRM., Tadros SFK., Contrast-enhanced mammography versus breast MRI in the assessment of multifocal and multicentric breast cancer: a retrospective study, Acta Radiol, 2023 Nov;64(11):2868-2880.

- Monticciolo DL., Newell MS., Moy L., Lee CS., Destounis SV., Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Higher-Than-Average Risk: Updated Recommendations From the ACR, J Am Coll Radiol, 2023 Sep;20(9):902-914. [CrossRef]

- Wessling D., Männlin S., Schwarz R., Hagen F., Brendlin A., Olthof SC., Hattermann V., Gassenmaier S., Herrmann J., Preibsch H., Background enhancement in contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM): are there qualitative and quantitative differences between imaging systems?, Eur Radiol, 2023 Apr;33(4):2945-2953. [CrossRef]

- Gennaro G., Hill ML., Bezzon E., Caumo F., Quantitative Breast Density in Contrast-Enhanced Mammography, J Clin Med, 2021 Jul 27;10(15):3309. [CrossRef]

- Lin ST., Li HJ., Li YZ., Chen QQ., Ye JY., Lin S., Cai SQ., Sun JG., Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced mammog-raphy for suspicious findings in dense breasts: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Cancer Med, 2024 Apr;13(8):e7128.

- Camps-Herrero J., Pijnappel R., Balleyguier C., MR-contrast enhanced mammography (CEM) for follow-up of breast cancer patients: a "pros and cons" debate, Eur Radiol, 2024 Oct;34(10):6264-6270. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).