Background Introduction

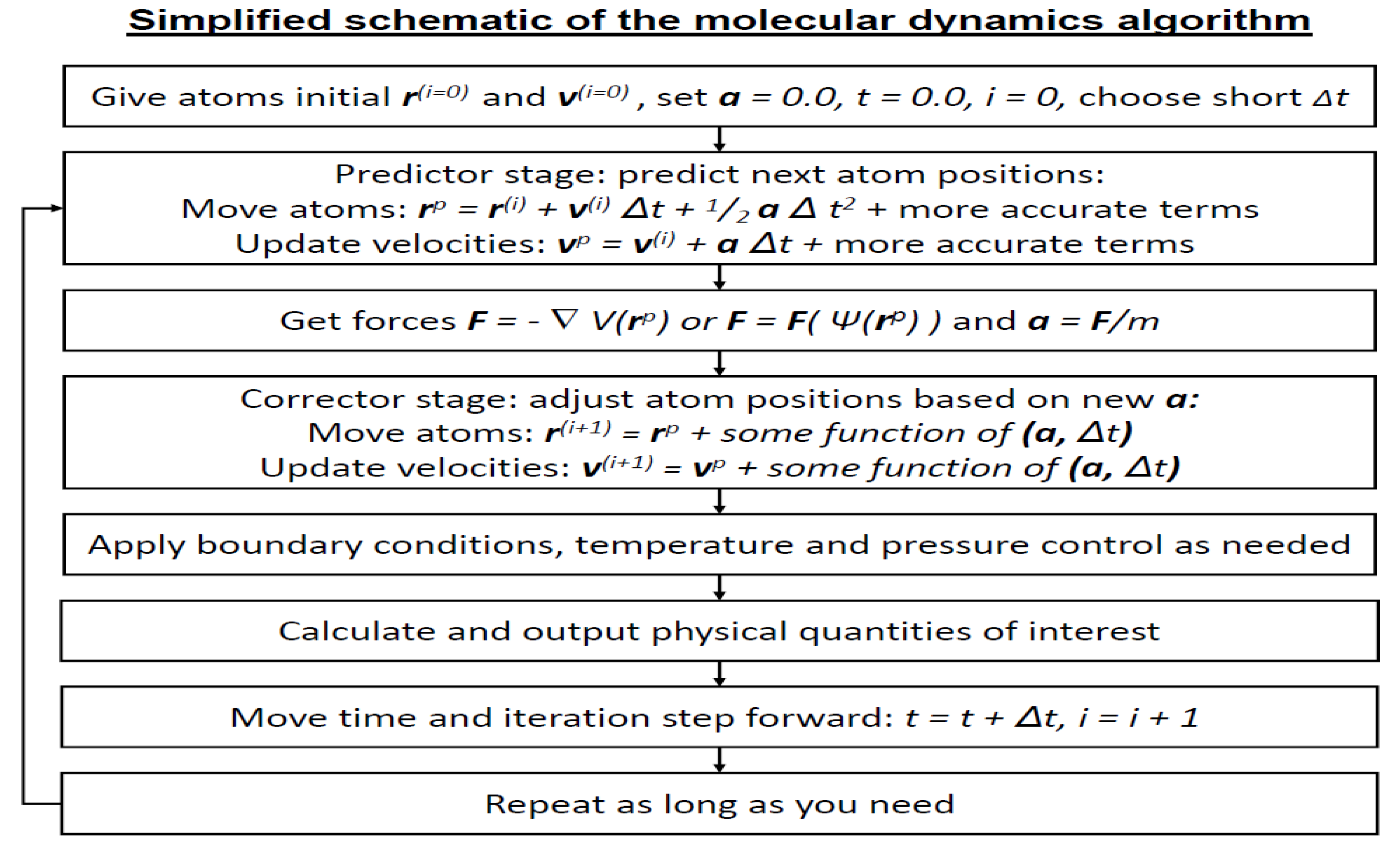

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computational technique that simulates the movements of atoms and molecules over time. By integrating Newton’s equations of motion, it calculates trajectories based on forces derived from molecular mechanics force fields or interatomic potentials. This dynamic simulation offers a detailed atomic-level view of how a molecular system evolves.

Because real-world molecular systems involve an enormous number of particles, exact analytical solutions are infeasible. MD tackles this by using numerical integration to approximate the system’s behavior. Despite the inherent accumulation of integration errors over long simulations—errors that can only be reduced, not eliminated—MD remains a powerful approach when the right algorithms and parameters are chosen.

In systems that satisfy the ergodic hypothesis, a single long-running MD trajectory can be used to compute macroscopic thermodynamic properties. That’s because time-averaged behaviors in these systems are equivalent to ensemble averages, earning MD the nickname “statistical mechanics by computation.” This method aligns with a vision of animating nature’s fundamental forces to forecast molecular motion.

A typical MD workflow with a predictor–corrector integrator includes:

Initializing atomic positions and velocities.

Computing forces via classical or quantum-based potential energy calculations.

Predicting new positions and velocities.

Correcting these predictions using computed forces.

Iterating this process over time steps, which may be fixed or adaptive depending on the integrator used.

Different integrators apply different mathematical schemes—some incorporate derivatives of higher order, while others utilize past and current time steps for variable-step simulations. Each choice affects the accuracy and stability of the simulation, making algorithm selection a critical component of MD studies.

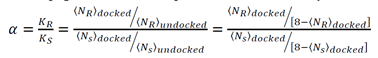

Figure 1.

MD snapshot showing the TMA–(Pro)*₆–N(CH₃) tripeptide chiral stationary phase interacting with R- (blue) and S- (red) enantiomers of α-methyl-9-anthracenemethanol in a hexane/2-propanol solvent. The proline selector is rendered in full atom detail; atoms in the surface and solvent are coded by type (Si–yellow, O–red, C–cyan, N–blue, H–white). Reproduced from Ref. [70] via Ref. [

3].

Figure 1.

MD snapshot showing the TMA–(Pro)*₆–N(CH₃) tripeptide chiral stationary phase interacting with R- (blue) and S- (red) enantiomers of α-methyl-9-anthracenemethanol in a hexane/2-propanol solvent. The proline selector is rendered in full atom detail; atoms in the surface and solvent are coded by type (Si–yellow, O–red, C–cyan, N–blue, H–white). Reproduced from Ref. [70] via Ref. [

3].

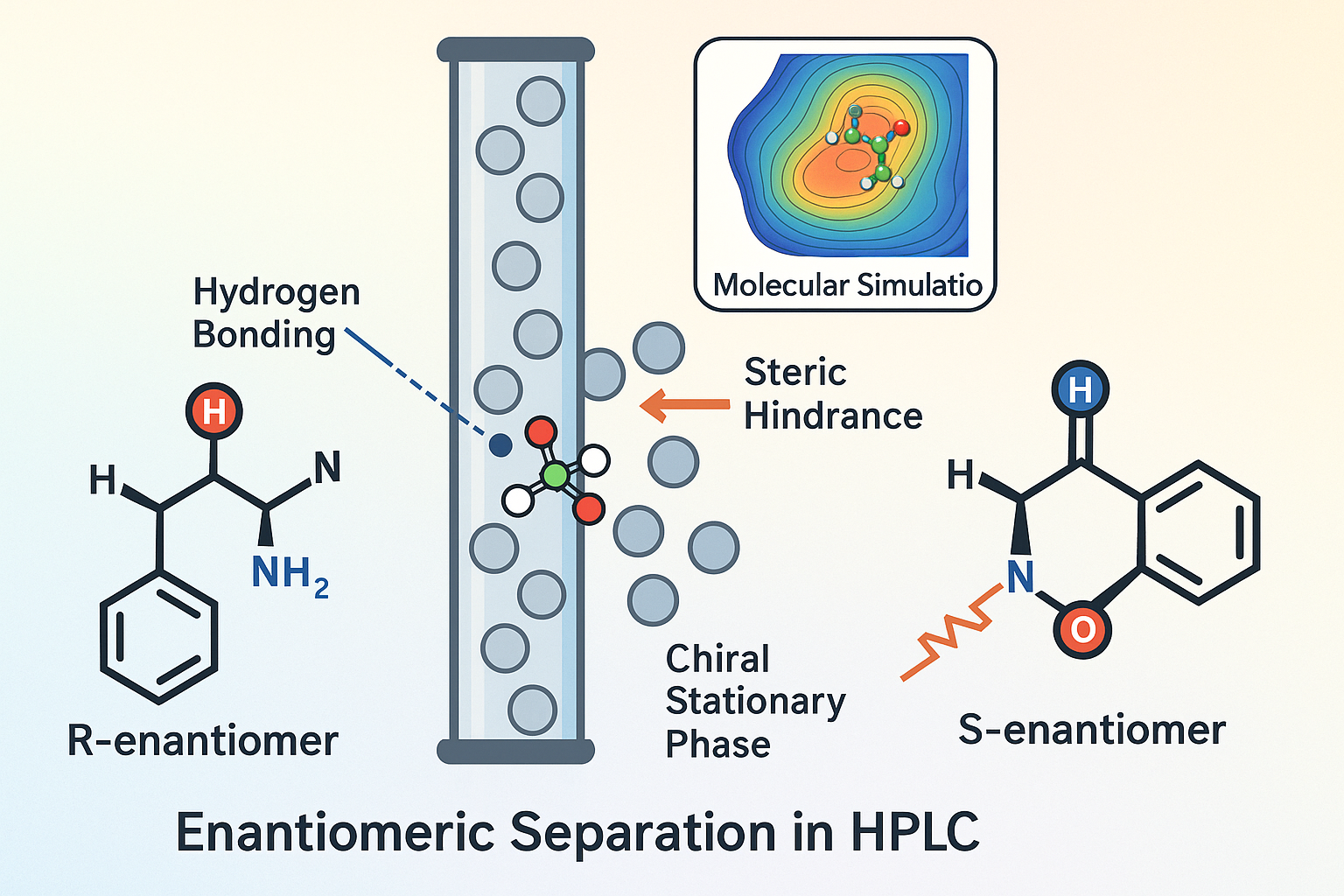

Chiral Chromatography

Separating enantiomers of chiral molecules through chromatographic techniques is a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, particularly when analyzing biologically and pharmaceutically relevant compounds. While chiral resolution can be achieved using gas chromatography, liquid chromatography and capillary electrophoresis are more prevalent—especially in pharmaceutical contexts—because they better accommodate the structural diversity of drug-like molecules.

In chiral-selective biological systems, different enantiomers of a drug frequently show distinct profiles in bioavailability, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and pharmacological effect. Typically, one enantiomer (the eutomer) is therapeutically active, whereas the other (the distomer) may be less active, toxic, provoke side effects, or even act as an antagonist. These divergences stem from enantiomer-specific interactions with transport proteins, enzymes, and receptors, as well as differences in metabolic pathways and environmental stability.

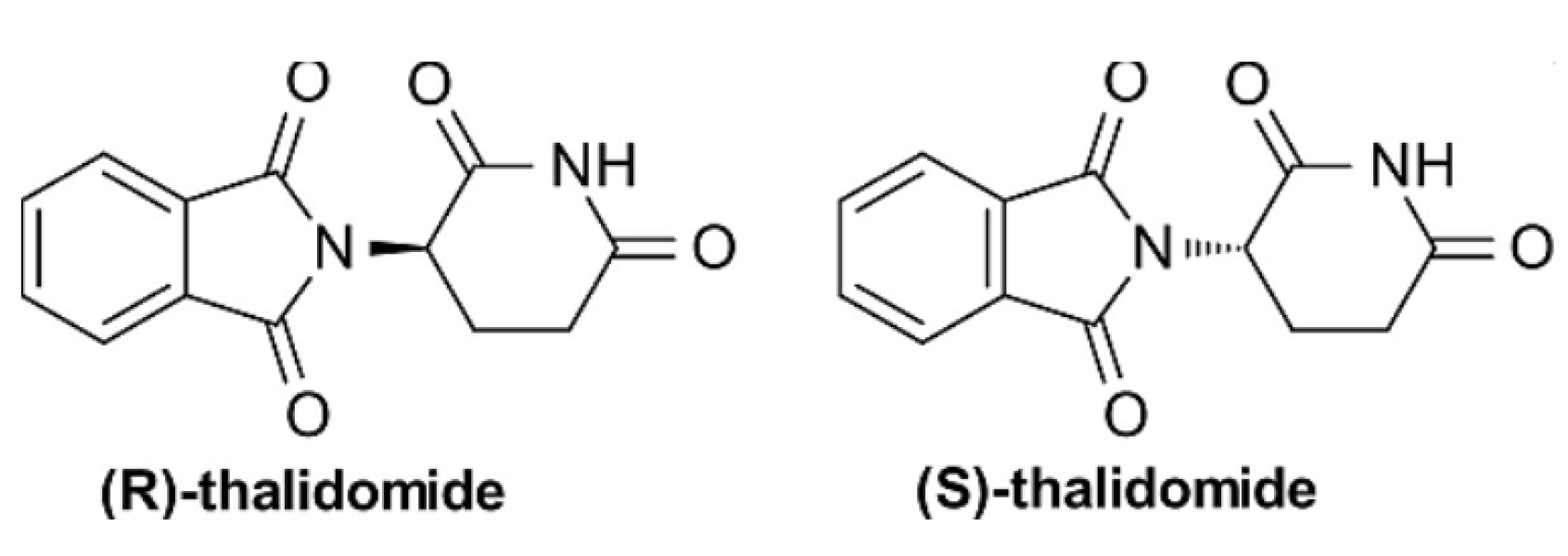

One infamous case illustrating the importance of enantiomeric purity is racemic thalidomide, which was introduced in the late 1950s in the UK as a sedative. Tragically, only the R-(+) enantiomer provides therapeutic benefit, while the S-(–) enantiomer is teratogenic and responsible for the drug’s severe birth defects. This case underscores the critical importance of effective enantiomer separation in pharmaceutical development and assurance of safety.

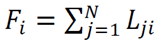

Figure 2.

Two β-cyclodextrin–silica CSP constructs: “CSP2” with the wide rim exposed and “CSP1” inverted. Chromatographic data show a reversal in elution order and changes in separation efficiency between the two orientations. Adapted from Ref. [107] via Ref. [

3].

Figure 2.

Two β-cyclodextrin–silica CSP constructs: “CSP2” with the wide rim exposed and “CSP1” inverted. Chromatographic data show a reversal in elution order and changes in separation efficiency between the two orientations. Adapted from Ref. [107] via Ref. [

3].

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly prioritizes the production of enantiomerically pure compounds to develop safer and more effective drugs. There are two main strategies to achieve this:

Selective synthesis – producing only the desired enantiomer directly through stereoselective chemical methods.

Resolution of racemic mixtures – separating the two enantiomers after they’ve been formed as an achiral mixture.

While stereoselective synthesis is often the most efficient route in terms of avoiding downstream separation, it’s rarely used during the early stages of drug development. This is primarily because such methods are costly and time-consuming to scale up, even though they remain a key goal of modern synthetic chemistry.

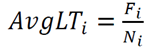

Figure 3.

Structures of ten analytes studied by Murad et al. (Ref. [62] via Ref. [

3]), each capable of hydrogen bonding with amylose tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl carbamate) (ADMPC). Red highlights oxygen or nitrogen acceptors, while attached blue hydrogen atoms mark donors on both analyte and CSP.

Figure 3.

Structures of ten analytes studied by Murad et al. (Ref. [62] via Ref. [

3]), each capable of hydrogen bonding with amylose tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl carbamate) (ADMPC). Red highlights oxygen or nitrogen acceptors, while attached blue hydrogen atoms mark donors on both analyte and CSP.

When resolving racemates, two main approaches are employed:

Indirect resolution involves converting enantiomers into covalent diastereomers, which have different physicochemical properties. These differences allow separation using techniques such as crystallization, non-chiral chromatography, or distillation.

Direct resolution relies on the formation of noncovalent diastereomeric complexes between the racemate and a chiral selector. This can be achieved using a chiral stationary phase (CSP) in chromatographic systems or by adding a chiral mobile phase additive (CMA) to interact selectively with one enantiomer over the other.

By leveraging these strategies, chemists can obtain enantiomerically pure compounds critical for drug safety and efficacy.

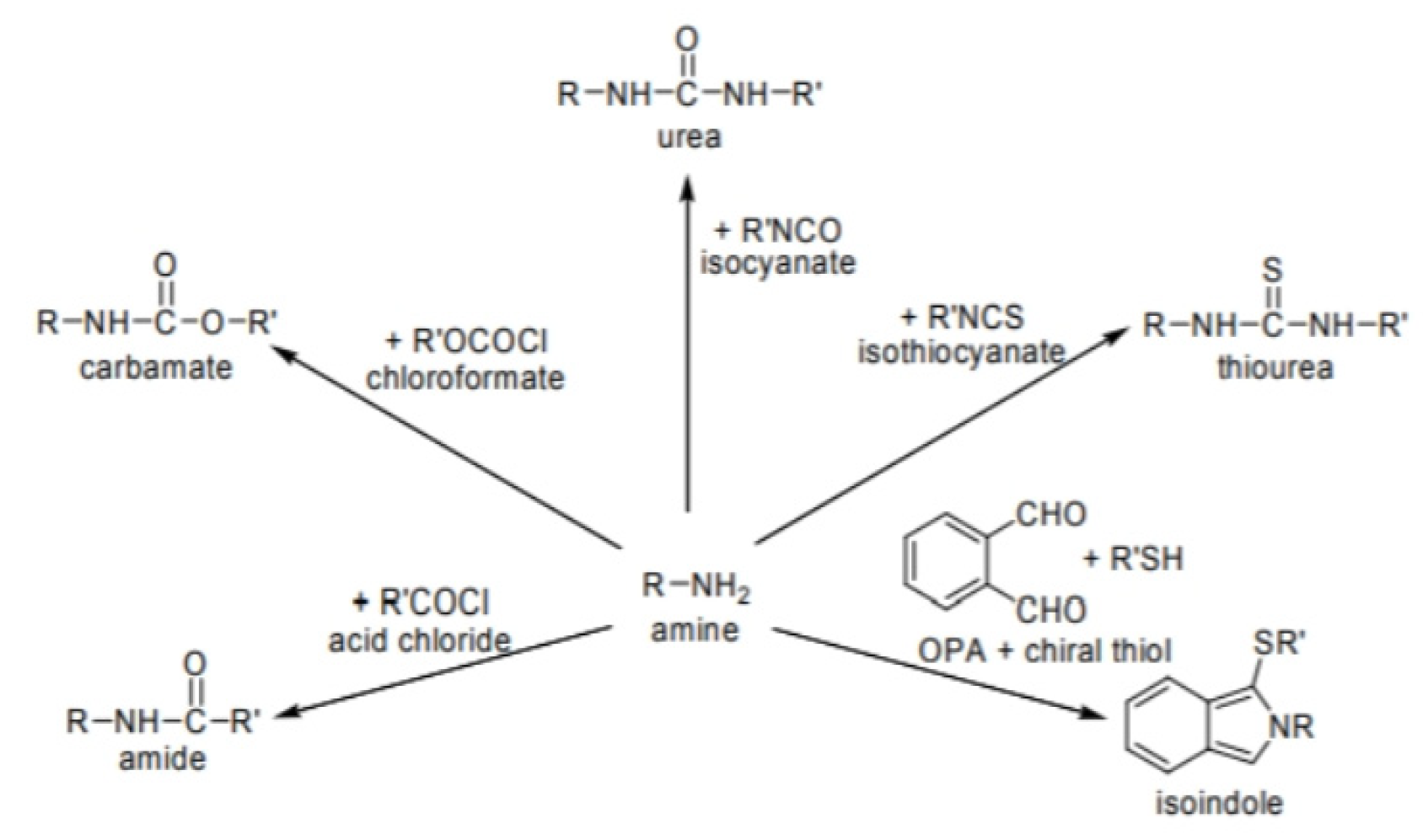

Indirect Chromatographic Methods

The earliest widely adopted approach for separating enantiomers in liquid chromatography involved the use of chiral derivatizing agents (CDAs) to convert enantiomeric compounds into separable diastereomeric pairs. This process typically involves a chemical reaction between the CDA and a functional moiety on the analyte—common targets include amine, carboxyl, carbonyl, hydroxyl, and thiol groups.

Among these reactions, derivatizing primary and secondary amines holds particular prominence. The reagents most frequently employed for chiral amine tagging—such as those forming amides, carbamates, ureas, or thioureas—have become the cornerstone of CDA chemistry in enantiomeric resolution. The most significant examples of these CDAs are typically illustrated in reference figures

Some examples of chiral derivatization reactions for amino groups (both R and R’ contain a chiral center) leading to the formation of diastereomer pairs for each solute enantiomer.

Indirect chiral separation methods—where enantiomers are converted into diastereomers—offer several key advantages:

Advantages

Derivatives typically demonstrate favorable chromatographic characteristics.

The elution order of enantiomers can be anticipated.

Many CDAs possess strong chromophoric or fluorophoric groups, increasing detection sensitivity.

Because achiral columns are used, overall costs are lowered.

Method development tends to be straightforward.

The increased selectivity of diastereomer separation often surpasses that of direct methods.

However, these methods also carry some drawbacks:

∙

The quality of the CDA is crucial, as any impurities may compromise the derivatization process.

∙

Unreacted reagent or by-products might co-elute or interfere with the target separation.

Direct Chromatographic Methods

Chiral Mobile Phase Additives (CMAs)

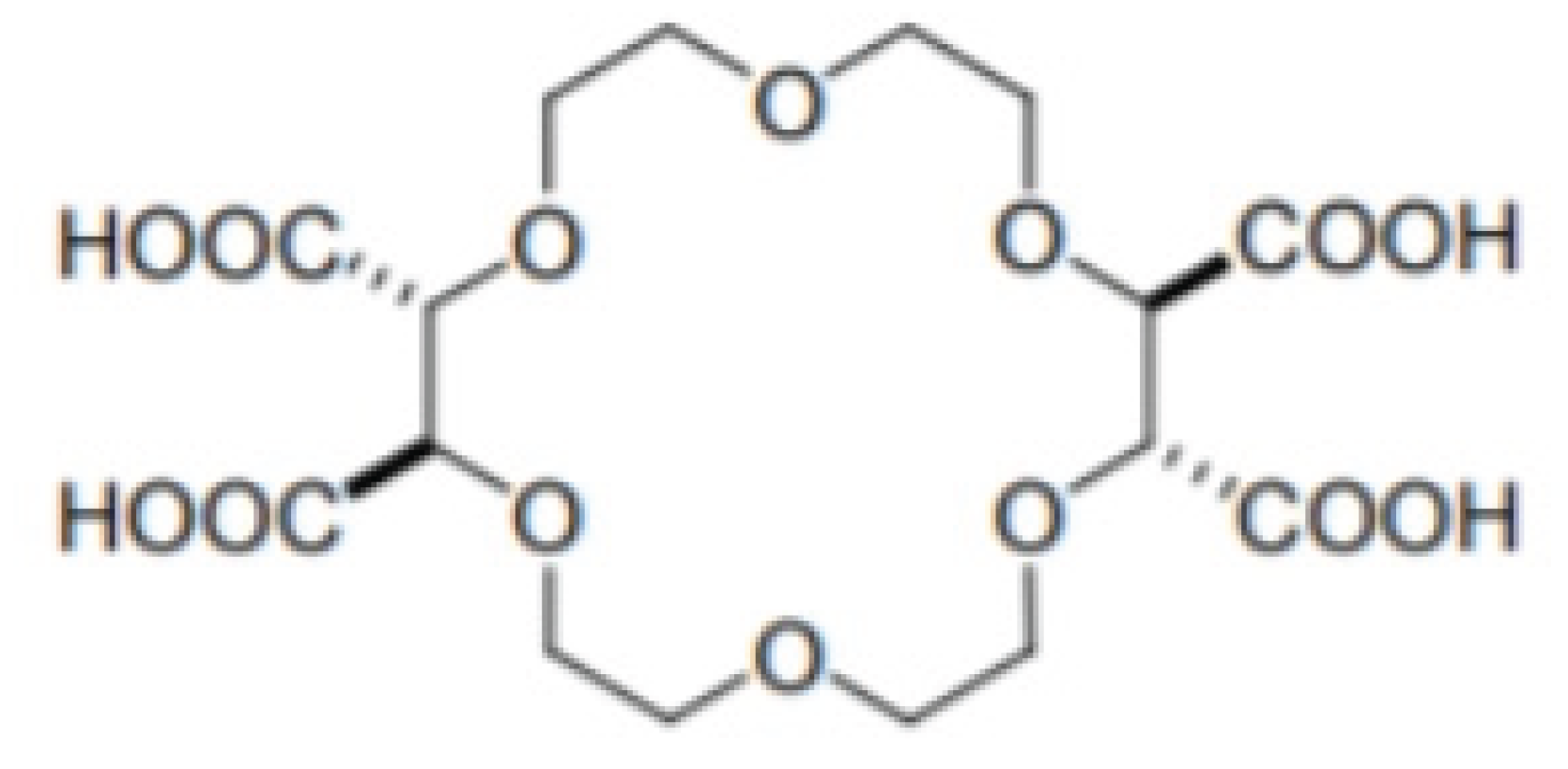

Enantiomer separation on standard achiral columns can be achieved by incorporating chiral selectors directly into the mobile phase. These chiral mobile phase additives (CMAs) can include cyclodextrins, chiral crown ethers, chiral counter-ions, or chiral ligands. Some CMAs even form ternary complexes with enantiomers in the presence of a transition metal ion, enabling effective enantiomeric discrimination.

Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs)

The 1980s marked a pivotal era for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of enantiomers, with a surge in the development and publication of novel chiral stationary phases (CSPs). CSPs are typically categorized by their mechanism of chiral recognition into several primary classes:

Pirkle-type phases

Helical polysaccharides, such as cellulose and amylose derivatives

Cavity-based materials, including cyclodextrin-derivatives

Macrocyclic antibiotics

Protein- and ligand-exchange phases

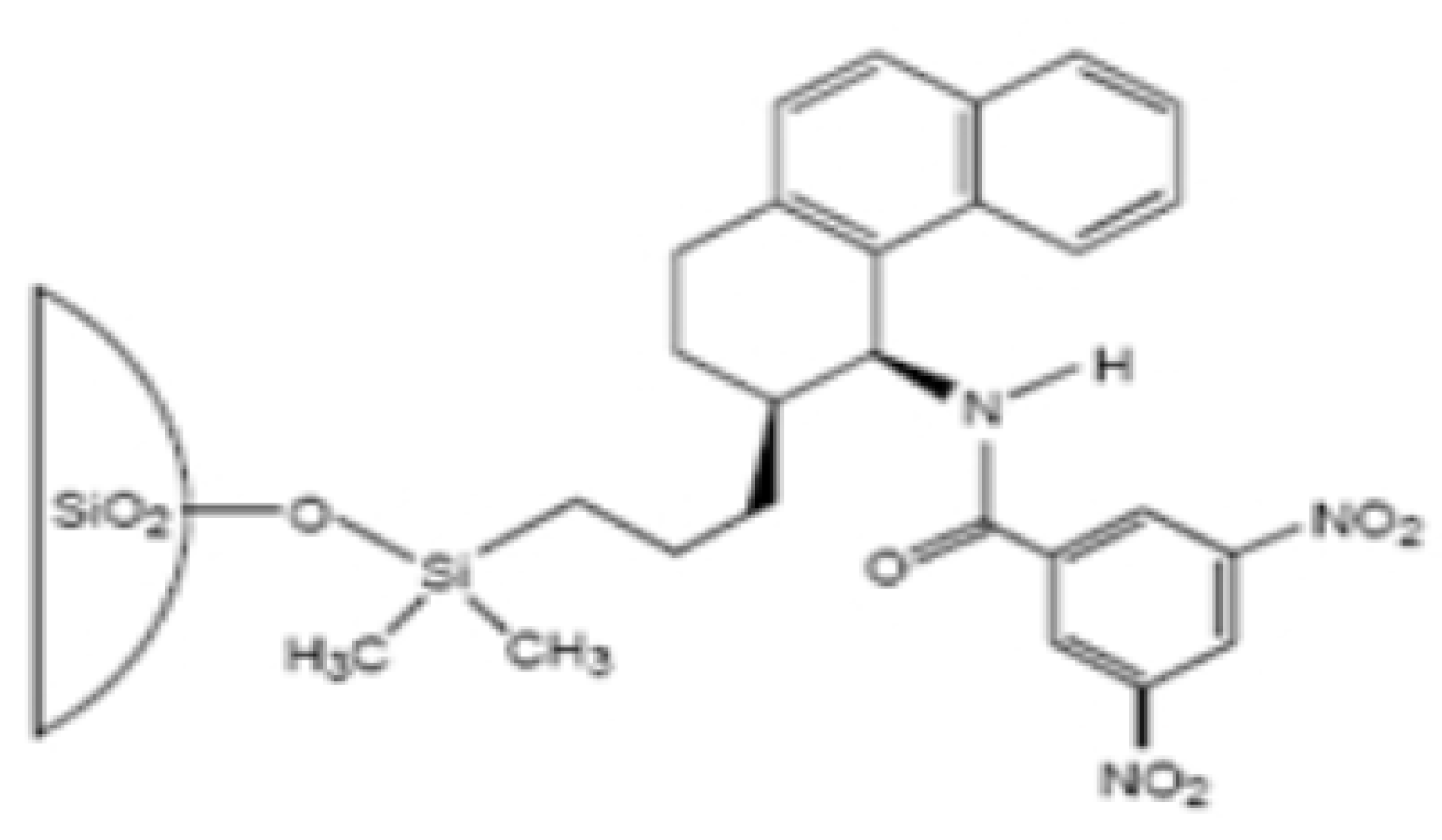

Pirkle Phases

The first commercial CSP was pioneered in the 1980s by William Pirkle’s group at the University of Illinois. In this approach,

(R)-2,2,2-trifluoro-1-(9-anthryl)ethanol was immobilized on silica, providing a platform for resolving π-acidic racemates—such as dinitrobenzoyl derivatives of amines, amino acids, and amino alcohols. Building on this, Pirkle’s lab also developed

π-basic CSPs, featuring functionalities like 1-aryl-1-aminoalkanes, N-arylamino esters, and phosphine oxides. These phases were particularly adept at separating compounds with π-acidic components, including amino acid dinitrobenzoyl derivatives. Notably, phenylglycine DNB derivatives showed high separation factors [

12], motivating the creation of CSPs combining both π-acidic and π-basic sites. Pirkle’s vision culminated in a line of commercial CSPs—manufactured through collaborations like Regis Technologies—named to reflect their designer’s contributions and celebrated for their versatility in enantio-separation.

Figure 4.

Flow diagram for building simulation setups: starting with an amorphous, silanol-capped silica slab, uniformly coating it with ADMPC polymer strands (in arrangements aaaa, aabb, abba, abab), solvating the system, and then adding analyte molecules. The red dashed region indicates steps repeated when solvent composition changes. Adapted from Ref. [

3].

Figure 4.

Flow diagram for building simulation setups: starting with an amorphous, silanol-capped silica slab, uniformly coating it with ADMPC polymer strands (in arrangements aaaa, aabb, abba, abab), solvating the system, and then adding analyte molecules. The red dashed region indicates steps repeated when solvent composition changes. Adapted from Ref. [

3].

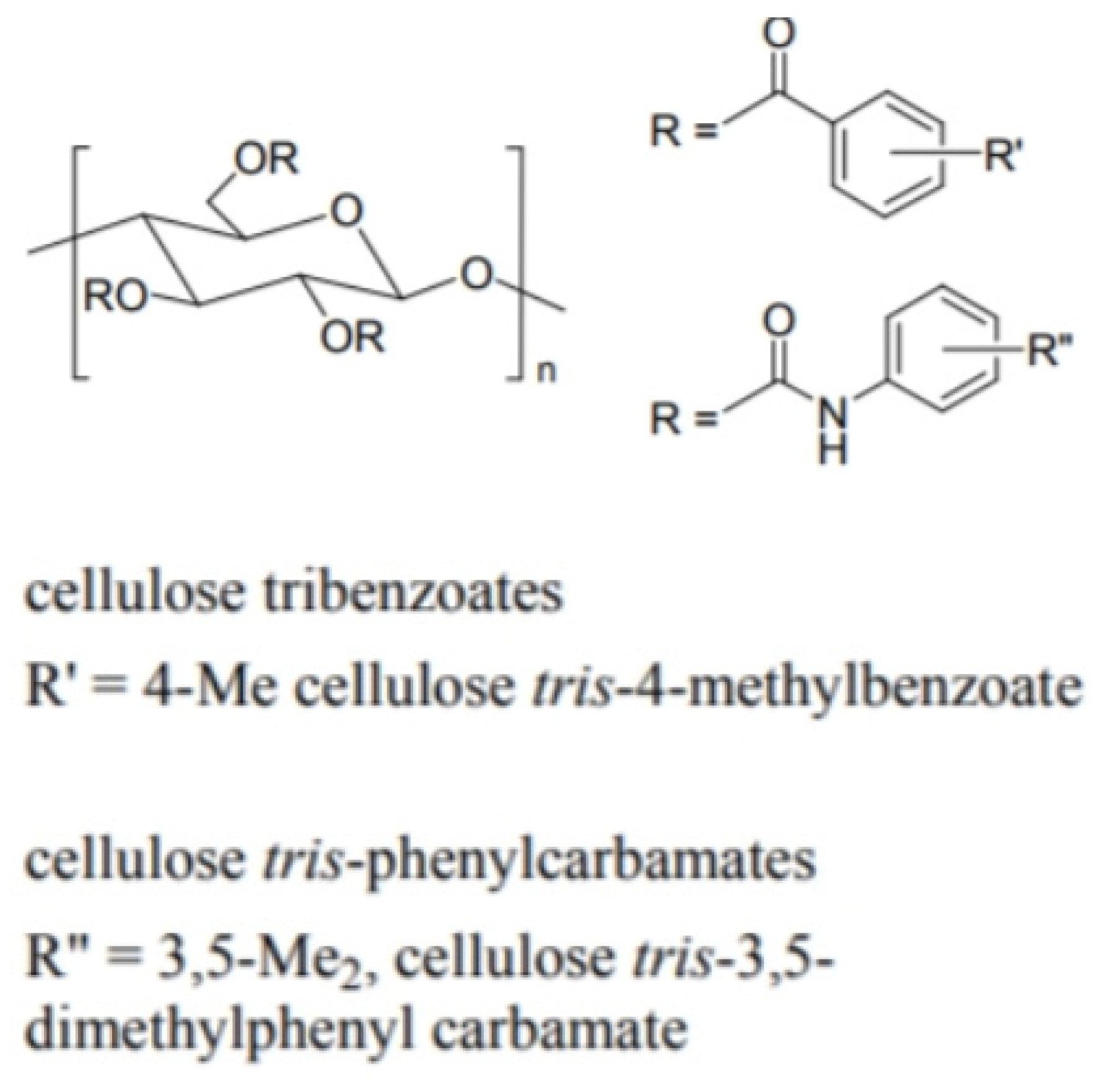

CSPs Based on Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides (Cellulose), a natural crystalline polymer composed of linear β-D-1,4-glucopyranose units arranged in a helical configuration, inherently possesses some chiral recognition capabilities. However, its practical use as a chiral stationary phase (CSP) is limited. Intact cellulose CSPs typically suffer from poor separation performance, broad chromatographic peaks, and sluggish mass transfer—issues stemming from slow diffusion within the dense polymer network. Additionally, the numerous polar hydroxyl groups on cellulose can lead to non–stereoselective binding with analyte enantiomers, and the unmodified polymer itself cannot handle conventional HPLC pressure.

To overcome these limitations, chemists derivatize cellulose, creating functionalized CSPs that offer much better separation performance and high enantioselectivities. Notably, derivatives such as cellulose tris(4-methylbenzoate) and cellulose tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl carbamate) incorporate both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents on the phenyl rings. These modifications optimize chiral recognition properties, enabling effective separation of a wide range of racemic compounds under HPLC conditions shown in Figure, containing both an electron-donating and an electron-withdrawing group on the phenyl moiety were prepared to perfect their chiral recognition abilities.

Figure 5.

Representative MD simulation snapshot: a silanol-capped amorphous silica slab supports four 18-mer ADMPC chains, with benzoin enantiomers interacting at the interface. Solvent molecules are omitted for clarity; all atoms are dynamic. Adapted from Ref. [

3].

Figure 5.

Representative MD simulation snapshot: a silanol-capped amorphous silica slab supports four 18-mer ADMPC chains, with benzoin enantiomers interacting at the interface. Solvent molecules are omitted for clarity; all atoms are dynamic. Adapted from Ref. [

3].

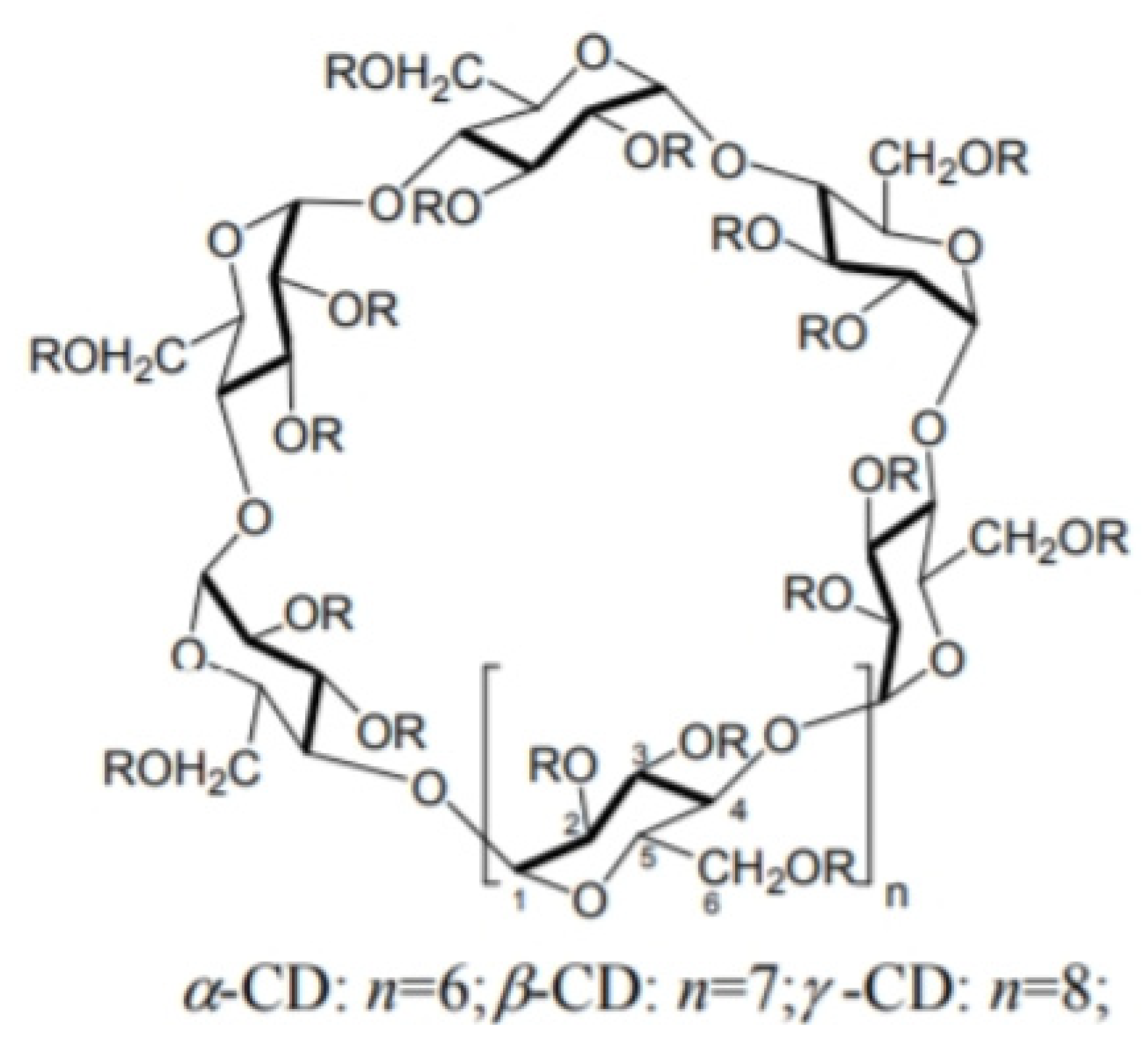

Cavity Phases

Chiral separation via inclusion mechanisms occurs when a guest enantiomer enters the cavity of a host molecule that selectively interacts with one enantiomer over the other. The outer surfaces of these host molecules contain functional groups that help discriminate between enantiomers, often through steric effects or specific interactions.

A classic example of this approach involves cyclodextrins (CDs) immobilized on silica as chiral stationary phases (CSPs). CDs are cyclic oligosaccharides composed of six (α-CD), seven (β-CD), or eight (γ-CD) D-glucopyranose units linked by α-1,4 bonds. These molecules form truncated, toroidal cavities—roughly 5.7 Å (α-CD) to 9.5 Å (γ-CD) in diameter and about 7 Å deep—ideal for selectively hosting partially nonpolar enantiomers. The cavity interiors are hydrophobic (lacking hydroxyl groups), while the outer rims are hydrophilic, lined with primary (C-6) and secondary (C-2, C-3) hydroxyl groups. This structural arrangement makes CDs effective for inclusion-based enantiomer separation.

Chemical modifications to CDs—such as sulfation, acetylation, permethylation, perphenylation, hydroxypropylation, 3,5-dimethylcarbamoylation, or naphthylethyl carbamoylation—enhance their selectivity and resolving power. These CD-based CSPs are versatile, performing efficiently across reversed-phase (RP), normal-phase (NP), and polar-organic (PO) chromatographic modes, thus being classified as multi-modal separation phases.

Figure 6.

Six snapshots showing instances of valsartan engaging with two ADMPC strands at once—examples include R- and S-enantiomers in aaaa, abab, and abba arrangements—and a close-up detailing simultaneous hydrogen bonding (solid arrow) and hydrophobic ring–ring interaction (dashed arrow). Adapted from Ref. [63] via Ref. [

3].

Figure 6.

Six snapshots showing instances of valsartan engaging with two ADMPC strands at once—examples include R- and S-enantiomers in aaaa, abab, and abba arrangements—and a close-up detailing simultaneous hydrogen bonding (solid arrow) and hydrophobic ring–ring interaction (dashed arrow). Adapted from Ref. [63] via Ref. [

3].

Another group of cavity based CSPs are formed using crown ethers, heteroatomic macrocycles with repeating (-X-C2H4-) units, where X, the heteroatom, is commonly oxygen, but may also be a Sulfur or Nitrogen atom. an example crown ether compound is shown in Figure. Unlike CDs, the host-guest interaction within the chiral cavity is hydrophilic in nature. Crown ethers, and especially 18-crown-6 ethers, can complex inorganic cations and alkylammonium compounds. This inclusion interaction is based mainly on H-bonding between the hydrogens of the ammonium group and the heteroatom of the crown ether. Additional electrostatic interaction occurs between the nitrogen and the crown ether’s oxygen lone pair electrons.

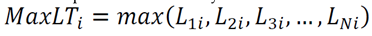

Figure 7.

Histograms mapping hydrogen-bond lifetimes (in ps) for R and S valsartan interacting with ADMPC on silica in heptane/isopropanol. Y-axis shows event counts (short-lived interactions are clipped); colored traces represent donor–acceptor site pairs (oxygen or nitrogen). Adapted from Ref. [

3].

Figure 7.

Histograms mapping hydrogen-bond lifetimes (in ps) for R and S valsartan interacting with ADMPC on silica in heptane/isopropanol. Y-axis shows event counts (short-lived interactions are clipped); colored traces represent donor–acceptor site pairs (oxygen or nitrogen). Adapted from Ref. [

3].

Macrocyclic Antibiotic Phases

Macrocyclic antibiotics form a highly effective class of chiral selectors used in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), thin-layer chromatography (TLC), and capillary electrophoresis (CE) to resolve enantiomers of biologically and pharmaceutically important compounds. These antibiotics are covalently anchored to silica gel via various linker chemistries—such as carboxylic acid, amine, epoxy, or isocyanate-terminated organosilanes—ensuring both firm attachment and preserved chiral recognition properties.

Because they can operate under a range of chromatographic conditions—normal phase, reverse phase, polar-organic, or polar-ionic—macrocyclic antibiotic CSPs are considered multimodal. Common examples include:

Ansamycins (such as rifamycins)

Glycopeptide antibiotics like avoparcin, teicoplanin, ristocetin A, vancomycin, and their derivatives

Polypeptide antibiotics, notably thiostrepton

One of the most widely used selectors is

teicoplanin, which incorporates four interconnected macrocyclic rings into a structure that features seven aromatic rings—two chlorinated and the remainder phenolic—enhancing its ability to form specific chiral interactions with analyte molecules [

2].

1. Introduction

Optimizing chromatography methods for chiral enantiomer separation remains one of the most effective strategies for obtaining enantiomerically pure substances. However, experimentally determining the optimal conditions [

1] —such as choice of chiral selector, solvent system, pH, additives, temperature—can be both time-consuming and expensive.

To streamline this process, computational pre-screening tools can play a crucial role. By using atomistic models that explicitly include solvent molecules, researchers can simulate interactions between enantiomers and a chiral stationary phase [

2] (particularly polysaccharide-based CSPs like cellulose and amylose derivatives) under a range of conditions. Though these CSPs are highly effective and widely used due to their versatility and robustness, their large size poses significant computational challenges.

Thanks to the power of massively parallel molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, pre-screening hundreds of experimental setups can be completed in a fraction of the time required for actual lab work. For example, running 100 MD simulations concurrently could effectively replace the need for 100 individual HPLC experiments. These simulations not only predict which conditions yield the best separation factors [

12] but can also determine which enantiomer will elute first—providing invaluable insight for method design.

Earlier computational approaches relied on simplified stochastic models that represented chromatographic elution as adsorption–desorption processes, based on rate constants or residence times derived from experimental data. While useful for modeling peak shapes, these methods didn’t elucidate the detailed molecular interactions responsible for enantiomeric discrimination. By contrast, modern atomistic simulations focus on uncovering the specific mechanisms of chiral recognition at the molecular level.

Notable early reviews on this topic include work by Lipkowitz, who surveyed atomistic studies on enantioselectivity in chromatography, and research by Siepmann, which examined molecular-level simulations of reversed-phase liquid chromatography with explicit substrate models. These foundational studies paved the way for today’s computationally driven, mechanistic understanding of chiral separation processes.

2. Earlier Models Used to Understand Chiral Discrimination

2.1. Three-Point Model

For two enantiomers to be effectively separated on a chiral stationary phase (CSP) in chromatography, each must form fleeting diastereomeric complexes with the CSP, and the key is that these complexes exhibit different stabilities. The enantiomer that forms the less stable complex interacts less strongly and thus elutes more quickly, while the more stable complex results in greater retention and a later elution.

Several conceptual models have been introduced to explain chiral recognition in HPLC, most notably based on static interaction frameworks like the three-point interaction rule [

5] (also known as the Easson–Stedman model). According to this rule, effective enantiomer differentiation requires a minimum of three simultaneous interactions with the CSP—typically two hydrogen bonds and one π–π interaction. Due to spatial constraints, only one enantiomer can achieve this complete set of interactions, while the counterpart is sterically hindered, preventing full engagement.

Building on this,

Pirkle and Pochapsky [6] refined the model further—often referred to as

Pirkle’s rule—emphasizing that at least three interactions are needed, one of which must be stereochemistry-dependent. They clarified that “interaction” encompasses not just intermolecular forces but also the volumetric and spatial fit between molecule and selector. More advanced models expanded these ideas, proposing four-point contact frameworks or comparing distance-matrix profiles between enantiomers and selectors to predict discriminatory binding.

Despite valid criticisms of its simplicity, the three-point interaction rule [

5] remains a widely used teaching tool and starting point for understanding how CSPs distinguish between enantiomeric pairs.

2.2. Molecular Docking of Enantiomers on a Fragment of the CSP in Vacuum

Chiral separation mechanisms in chromatographic processes have frequently been modeled using molecular docking, where each enantiomer is treated as a rigid molecule and paired with a rigid fragment of a chiral stationary phase (CSP) in a vacuum environment. This approach helps predict binding energies and geometries to infer which enantiomer will elute first.

Here’s a streamlined outline of how it works:

Rigid docking setup – Both the enantiomer and a CSP fragment (e.g., a polysaccharide monomer or a short oligomer) are held fixed, typically without solvent.

Conformational sampling – Multiple conformers of the enantiomers are generated and clustered.

Energy estimation – Binding energies are averaged across clusters, or the energy of the most populated cluster is used as a predictive indicator.

Elution inference – The enantiomer showing the weakest binding is predicted to elute first.

This workflow traces back to the foundational methods introduced by Morris in 1998, which evolved into the widely used AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4. A more systematic protocol known as Global Molecular Interaction Evaluation (Glob-MolInE) follows a similar path but includes exhaustive conformational searches of both selector and analyte, automated rigid docking of all low-energy conformers, and even incorporates rigid dynamic docking in later stages.

Although these docking studies are typically performed in vacuo, there have been efforts to include explicit solvent [

13] molecules before docking—using specialized software to predict water positions and anticipate displacement effects.

To manage computational cost, researchers often use simplified CSP models. These might include a single monomer of a polysaccharide or a segment from the polymer’s crystal structure (e.g., a hexamer). After multiple docking runs, the lowest-energy complexes are selected to represent the most likely binding mode and guide predictions of elution order.

This rigid docking framework remains a widely used, efficient strategy for predicting chiral separation behavior—despite its approximation of dynamic, solvated systems.

2.3. Molecular Docking Followed by Geometry Relaxation Using MD

Docking methods enable rapid exploration of a wide range of possible diastereomeric binding modes between enantiomers and a chiral selector. Once promising complexes are identified, these “best poses” are subjected to further refinement using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations—typically in a vacuum or uniform dielectric environment, supplemented with explicit solvent [

13] to enhance realism.

For instance:

A single cellulose tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl carbamate) monomer may be used to dock enantiomers of three different pharmaceuticals. The most favorable pose is then refined through MD within a solvent mixture (e.g., 70/30 methanol, ethanol, or 2-propanol in n-hexane).

In another study, a four-glucose segment of Chiralcel OJ (cellulose tris(4-methylbenzoate)) served as the docking target for pyrazole derivatives. Subsequent MD refinement—initiated from the top docking pose—was performed in ethanol, using an extended version of the polymer structure.

In both workflows, MD acts as a post-docking refinement tool, adding molecular flexibility and solvent effects to static docking models, improving the prediction of chiral binding and, by extension, chromatographic behavior.

3. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations as a Method of Describing the Dynamic Chromatographic Process

Static models of chiral recognition fail to capture the inherently dynamic nature of chromatography—where the structures of both the chiral stationary phase (CSP) and the enantiomers continuously fluctuate in the presence of a mobile phase. In contrast, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer an atomistic and time-resolved view of these interactions. Over trajectories spanning hundreds of nanoseconds, MD enables comprehensive sampling of the distributions of binding conformations and thermodynamic properties.

This dynamic modeling proves especially valuable when the analyte is conformationally flexible: the simulation naturally explores multiple binding modes and their interconversion. Moreover, MD empowers researchers to virtually modify the CSP—altering functional groups, substituents, or linker chemistry—to test how such changes influence enantioselectivity before ever entering the lab.

Thanks to modern high-performance computing, running many MD simulations in parallel drastically reduces the pre-screening timeline: exploring tens or hundreds of experimental variants can be as fast as completing just one, constrained only by the duration of a single simulation. Full atomistic detail—especially accurate hydrogen bonding [

7] representation—is essential for reliable predictions, particularly with polysaccharide-based CSPs.

Beyond free-floating CSPs, MD can also illuminate structural characteristics of brush-type CSPs (where selectors are covalently grafted to silica). Simulations can reveal chain conformations (end-to-end distances, tilt angles, backbone order parameters), grafting densities, and solvent density profiles normal to the surface—all critical features that influence separation performance.

By leveraging MD in this way, we not only gain

molecular-level insight into chiral separation mechanisms, but we also enhance our ability to

predict elution order [11],

estimate separation factors [12], and optimize CSP design in silico.

3.1. Factors That Need to Be Considered in Designing the Simulation System

Modeling chromatographic interfaces in simulations presents several complexities:

-

Representing the stationary phase

- ○

Option A: Include a fully atomistic, dynamic support—e.g., an amorphous silica slab with experimentally informed silanol distributions.

- ○

Option B: Use a fixed silica layer where surface Si atoms serve as tethering sites for the CSP. Tether points may be arranged randomly, regularly, or based on known grafting densities. Example setups include trimethylsilyl end-capped selectors or chains grafted via amide bonds to siloxane-modified Si(111) wafers.

- ○

Option C: Omit the solid support entirely and either restrain the polymer fragment or allow it to float freely as a simplified model.

Choosing the CSP fragment size

-

o Large constructs such as quadruple 18-mer polysaccharide strands.

- ○

A single 12-mer polymer chain.

- ○

Smaller oligomers—hexamers, tetramers, or dimers—are often preferred. A monomer alone lacks the structural groove characteristic of helical polysaccharides.

- ○

For brush-type CSPs, tether length to the silica substrate is an additional variable.

-

Modeling the solvent environment

- ○

Explicit solvent: All molecules are represented atomistically, matching experimental composition.

- ○

Continuum dielectric model: Solvent effect approximated via a variable dielectric medium.

- ○

Vacuum: Used for simplified or initial exploratory simulations.

-

Applying rigid-body constraints

- ○

To accelerate simulations, rigid-body treatments are used—especially for aromatic rings with stiff internal geometry. Forces may be applied to maintain translational and rotational dynamics, while internal atomic positions remain fixed (e.g., the dinitrophenyl and tetrahydrophenanthrene units in Whelk-O1).

Key challenges and pitfalls:

Starting structure bias: Beginning from a docked complex or a known elution pose may precondition the results. Unbiased starting conditions are preferred for credibility.

CSP truncation artifacts: Shortening polymer chains can introduce “end effects” that distort binding behavior.

Omitting the substrate: Simulations lacking solid support may misrepresent interfacial recognition mechanisms.

Finite-size effects: Box dimensions must be tested; results should stabilize as size increases.

Finally, fully atomistic MD trajectories used to sample configurations are limited to hundreds of nanoseconds or a few microseconds, so accurate ensemble representation depends heavily on adequate initialization, inclusion of solvent (especially for hydrogen bonding), and mitigation of bias.

3.2. It Is Important to Include Explicit Solvent [13] Molecules

When the polarity of the mobile phase shifts from nonpolar to polar, the balance of intermolecular forces in chiral separations can change dramatically:

Electrostatic interactions grow stronger in low-dielectric (nonpolar) solvents and weaken in high-dielectric (polar) ones. In MD simulations, this is effectively modeled by the dielectric constant—ranging from ~1 in nonpolar environments up to ~80 in polar systems—being applied to the Coulomb term, which uniformly suppresses electrostatic interactions.

As electrostatic contributions diminish in polar media, van der Waals forces take on a more prominent role, altering molecular dynamics and binding landscapes—especially at close range.

Explicit solvent modeling is essential because it captures phenomena such as solvent-driven solvation/desolvation events and hydrogen-bond displacement when an enantiomer approaches the selector—dynamics that implicit or continuum models cannot accurately resolve.

Experiments confirm that the mobile phase composition influences chiral recognition not just indirectly but by changing the structural behavior of the CSP and analyte. For example, the ADMPC polymer adopts different conformations when switching from methanol to hexane/isopropanol or acetonitrile. Solid-state NMR shows that hexane molecules can become embedded within CSP structures, while polar solvents can disrupt intra- and intermolecular hydrogen-bond networks.

Consequently, only explicit-solvent MD simulations can faithfully reproduce crucial effects like solvent layering (stratification) in mixed systems and reveal local solvation differences that significantly affect binding.

Static interaction models—though useful—do not account for how solvent variations can

alter separation factors [12] or even invert elution order [11]. Therefore, a truly predictive understanding of chiral chromatographic separation must incorporate

both dynamic molecular behavior and explicit solvent effects to capture the full scope of molecular recognition mechanisms.

4. MD Studies on Covalently Bonded Selectors

Most molecular dynamics (MD) studies of chiral separations in HPLC have been conducted for reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC), where the chiral selector is covalently anchored to the silica surface via tether chains—frequently termed “brush-type” CSPs. However, the detailed composition and density of the mobile phase within the nanometer-scale pores of these selectors remain unknown before simulation or experiment.

This local environment can differ significantly from the bulk mobile phase. It’s well-established—particularly in nanoporous materials—that solvent composition inside pores often diverges from that of the surrounding solution. Such deviations become especially pronounced in mixed solvent systems, like n-hexane and ethanol, where selective adsorption leads to solvent stratification within the pores. Accurately modeling this phenomenon is essential for realistic simulations of chiral separations in RPLC systems.

4.1. Preparing the Interface: Solvent Effects on Covalently-Bonded Selectors

Most molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) now include explicit atomistic models of the solid substrate, tethered selector chains, the mobile phase, and analyte molecules. These comprehensive simulations have revealed several key insights:

At typical chain densities of ~2.9 µmol/m² or higher and with tether lengths equivalent to eight carbon atoms or more, RPLC systems reproduce expected retention behaviors in silico.

The retention mechanism at the molecular level is extraordinarily complex—dependent on subtle variations in chain alignment, solvent structuring near the surface, and grafting density—such that broad generalizations across systems are unreliable.

Though initially applied to achiral separations, these methods have enhanced our understanding of enantiomeric separation mechanisms, especially when using brush-type CSPs on planar or slit-pore silica supports with end-capped chains (e.g., tetramethylsilane terminations).

Specific MD studies have explored selectors such as:

PEPU (N-(1-phenylethyl)-N’-3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl-urea)

R-DNB-leucine and R-DNB-phenylglycine

Proline-based selectors with varying moieties

Whelk-O1 (1-(3,5-dinitrobenzamido)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrophenanthrene)

These selectors were simulated across different solvent environments—n-hexane/2-propanol, water/methanol mixtures, and supercritical CO₂ with methanol. The studies revealed how selector orientation and interfacial solvent layering shift in response to changing alcohol concentrations, offering crucial insights into how solvent selection influences chiral recognition.

4.2. MD Simulations of Chiral Analytes on Whelk-O1 Selectors

The Whelk-O1 chiral stationary phase (CSP) is constructed from 1-(3,5-dinitrobenzamido)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrophenanthrene molecules, which are covalently attached to silica via a short alkyl linker and a siloxane moiety. These selectors form brush-like structures that line the inner surfaces of porous silica beads.

In early MD studies, researchers focused on correctly modeling the solvation environment of this setup. They anchored trimethylsilyl end caps and silanol groups on a single, immobile silicon layer to simplify the substrate representation. Two such monolayers—positioned at the top and bottom—framed the simulation cell. The spacing between these silicon layers was adjusted to accommodate the selector volume and end groups so that the bulk solvent density (for example, 2-propanol) in the cell’s center stayed within 5% of its experimental value during simulations.

These simulations were later extended to study

chiral recognition of enantiomeric oxides—such as styrene oxide and stilbene oxide—as well as eight other analytes in

n-hexane. By analyzing docking frequencies between R and S enantiomers with the CSP, researchers were able to calculate separation factors [

12], providing quantitative insight into the selectivity of the Whelk-O1 system.

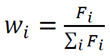

The separation factor, α, is calculated using average docking counts:

α=(NR,dockedNR−NR,docked)(NS,dockedNS−NS,docked)α=(NS−NS,dockedNS,docked)(NR−NR,dockedNR,docked)

Here, NR,dockedNR,docked and NS,dockedNS,docked are the average numbers of R and S enantiomer molecules bound to the CSP, respectively. The number of unbound molecules is simply the total number of that enantiomer in the simulation (e.g., 8) minus its bound average. This formulation assumes R is retained longer than S, but since the separation factor [

12] is always reported as greater than 1, it doesn’t rely on prior knowledge of which enantiomer elutes first in experiments.

Analysis of MD-generated complexes revealed four primary binding modes:

H-bonding via the amide hydrogen plus π–π stacking between the analyte’s aromatic ring and the selector’s dinitrophenyl group (the most common).

H-bonds involving the amide oxygen.

H-bonds with nitro oxygen atoms.

π–π stacking with the tetrahydrophenanthrene moiety.

One of MD’s key advantages is its ability to examine how targeted chemical modifications to the selector impact selectivity. Simulations have shown that even apparently straightforward changes—such as altering a functional group to prevent binding of the less retained enantiomer—can yield unanticipated effects. This underscores the value of in silico analysis: MD can uncover non-intuitive outcomes that might elude experimental intuition, guiding more informed and effective design of chiral selectors.

4.3. MD Simulations of Chiral Analytes on Proline-Type Selectors

In one study of chiral separation using proline-based CSPs, researchers focused on a model phase consisting of a TMA–(Pro)*₆–N(CH₃) chiral selector interacting with enantiomers of α-methyl-9-anthracenemethanol in a 70:30 hexane/2-propanol mobile phase.

A key finding was that using tert-butyl end groups connected via an ether linkage—rather than directly linked to the selector’s carbonyl—enhanced analyte accessibility. This effect was influenced by the solvent: extended conformations favored by hydrogen bonding were more pronounced in 70:30 water/methanol than in the nonpolar hexane/propanolmixture.

Further MD simulations—run on a complex model featuring 16 polyproline chains, 64 silanols, 48 trimethylsilyl end-caps, and 128 fixed Si atoms—yielded predicted separation factors for six different analytes under normal-phase conditions. The study compared how the two solvent systems (hexane/propanol vs. water/methanol) influenced hydrogen-bonding patterns and chiral selectivity, reinforcing the significant impact of mobile-phase composition on enantiomeric recognition.

5. MD Studies of Chiral Molecules Interacting with Cyclodextrins

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are cyclic molecules made of six (α-CD), seven (β-CD), or more α-D-glucopyranose units linked via 1→4 bonds, forming a rigid structure with a hydrophobic cavity and hydrophilic rims—ideal for selective binding. Since the mid-1980s, α- and β-CD derivatives have become staples in HPLC-based enantioseparation. Advances have focused on two key areas: functionalizing the CD structure to refine its selectivity, and covalently attaching CDs to solid supports for use as CSPs.

Inside cyclodextrins, the cavity is lined with hydrogen atoms and glycosidic oxygen bridges, creating a low-polarity environment favorable for lipophilic analytes. The outer rims, rich in hydroxyl groups, offer hydrophilicity. Modifying these rim hydroxyls with various functional groups tailors their enantioselective recognition.

Much of the early MD research with CD-analyte pairs used implicit solvent conditions—either vacuum or continuum dielectric models. However, explicit-solvent MD simulations have revealed more realistic behavior:

In trajectories lasting under 10 ns, water rarely penetrates the CD cavity.

In longer runs (e.g., 50 ns), water ingress into the cavity occurs but only after tens of nanoseconds.

Studies with β-CD and ibuprofen enantiomers in methanol show that methanol molecules preferentially occupy hydrogen-bonding sites, significantly altering binding compared to vacuum MD.

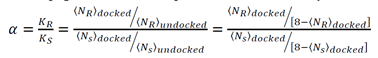

Recent work has modeled two silica-supported CD-CSPs with different orientations: “normal cup” (large rim attached) and “inverted cup” (small rim attached) CDs, anchored via click chemistry (using mono-6-azido-β-CD or mono-2-azido-β-CD). MD simulations—conducted with NAMD and the CHARMM force field in an explicit 50:50 water/methanol mix—maintained rim orientation by restraining glycosidic oxygen positions.

From these simulations, researchers derived Potential of Mean Force profiles and calculated absolute binding free energies and equilibrium constants for each enantiomer of isoxazolines and flavonoids in both CD orientations. Results showed that orientation dramatically impacts enantioselectivity, reflecting experimental chromatographic findings and underscoring the critical role of CD orientation and explicit solvent in defining chiral recognition.

6. MD Simulations of Chiral Recognition Using Polysaccharide CSPs

6.1. The Structure of Polysaccharide-Based CSPs

Polysaccharide-based chiral stationary phases (CSPs) are among the most effective and versatile options for enantiomer separation, thanks to both their performance and adaptability. These CSPs are either coated onto solid supports or covalently attached. A recent comprehensive review highlights their practical optimization—covering everything from tailoring the polysaccharide selector and its attachment method to refining support properties and fine-tuning separation conditions like mobile-phase composition and temperature. In routine screening, polysaccharide CSPs are typically the first choice, with Pirkle-type columns serving as secondary options when their unique chiral-recognition mechanisms are required.

One widely studied model polysaccharide CSP is amylose tris(3,5-dimethylphenylcarbamate) (ADMPC). Its structure and chiral recognition behavior have been explored using multiple analytical techniques—including solution and solid-state NMR (e.g., NOESY), vibrational circular dichroism (VCD), ATR-IR spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction. These studies consistently show that ADMPC adopts a left-handed 4/3 helical conformation in chloroform . In this helix, the glucose rings align along the backbone, carbamate groups nestle within polymer grooves, and the phenyl rings project outward. Additionally, research by Kasat indicates that the carbamate side chains maintain a planar orientation, while Bereznitski’s DSC and ATR-IR analysis suggests that differences in hydrogen-bond strength between each enantiomer and the ADMPC’s carbonyl group are the key drivers of chiral discrimination .

Together, this rich experimental evidence not only confirms the structural and mechanistic foundations of ADMPC but also reinforces why polysaccharide-based CSPs remain the go-to choice for a broad spectrum of enantioseparation applications.

6.2. MD of Chiral Interaction with Polysaccharide-Based CSP Without Explicit Solvent

Seventy-seven implicit-solvent MD simulations were combined with NMR studies to explore how a 12-mer segment of ADMPC (with a fixed backbone) interacts with the R and S enantiomers of p-O-tert-butyl-tyrosine allyl ester. The enantiomers were initially positioned within an ADMPC groove, and the resulting pair distribution functions aligned well with experimental 2D NOESY spectra, suggesting reasonable structural agreement. However, these results could be biased by the fixed backbone and pre-placed guest molecules, potentially skewing data from the short 2-ns simulation. Moreover, implicit solvent models cannot capture localized, solvent-mediated effects on molecular energy landscapes.

Kasat et al. conducted similar studies on ADMPC with a rigid backbone and no solvent—again highlighting the limitations of these simplified setups. In another example, researchers examined the interactions of eleven imidazole variants with Chiralcel OJ (a 12-mer cellulose tris(4-methylbenzoate)) using implicit solvent over 100-ps runs. They initiated simulations with analytes pre-placed in grooves and calculated average interaction energies every 10 ps to infer elution order. Although the overall energy range was large (12–20 kcal/mol), the differential interaction energies between the S and R enantiomers were relatively small (3–4 kcal), indicating that these short, solvent-free trajectories likely lack the precision needed for confident predictions. Interestingly, no hydrogen-bonding between the imidazole rings and the CSP was observed.

In a separate study, Li and colleagues modeled ADMPC on amine-terminated, silanol-capped silica in a vacuum environment. They selected a 13-mer segment from an equilibrated 36-mer—chosen for containing numerous chiral cavities—and locked its backbone dihedral angles to the values known in solution (Ψ = –68.5°, Φ = –42.01°). Docking simulations were then performed with both the ADMPC and enantiomers treated as rigid bodies in vacuum.

6.3. MD Using a Single Polymer Strand in the Solvent System

Researchers utilized a short 12-mer ADMPC soluble in chloroform to gain structural insights using solution NMR and NOESY, which detects H–H distances under 5 Å. The unique hydrogen assignments enabled precise mapping of analyte placement on the polymer. To validate this, 2 ns MD simulations—starting from energy-minimized structures—generated pair distribution functions. The positions of the first peaks (rₕₕ) closely matched NOESY cross-peak intensities, supporting the idea that a 12-mer strand could reliably model ADMPC’s chiral recognition behavior in atomistic, explicit-solvent MD simulations.

This work laid the foundation for using MD trajectory metrics—such as time-averaged structural and interaction data—to predict both elution order and separation factors (α). For example, D- and L-O-tert-butyl tyrosine allyl ester showed α = 16 on ADMPC; strong binding of the L-enantiomer yielded robust NOE data for quantitative comparison.

The MD protocol used involved:

Equilibration of the ADMPC 12-mer in each solvent (heptane/IPA 90/10, methanol, acetonitrile) for 100 ns to obtain a representative backbone structure.

Drug inclusion followed by additional 100 ns simulations, all initiated from the most populated backbone conformation (analyzed via φ/ψ dihedral maps akin to protein Ramachandran plots).

These dihedral maps revealed that solvent-dependent shifts in backbone and side-chain conformations significantly change the chiral binding landscape, explaining why solvent choice influences CSP performance.

Critically, simulations confirmed that unrestrained (freely floating) 12-mers did not exhibit sufficient selectivity. To mimic the restricted mobility of CSPs coated on silica, researchers applied weak harmonic restraints to all 12-mer atoms. This preserved essential flexibility while maintaining cavity integrity — resembling the crowded polymer environment on real column surfaces.

To uncover binding patterns, simulations computed hydrogen-bond lifetimes, considering all oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur donor-acceptor pairs using standard geometry criteria (distance < 3.0 Å, angle > 135°). These MD-derived metrics aim to correlate directly with observed chromatographic separation behavior, offering a powerful predictive framework for chiral selector design.

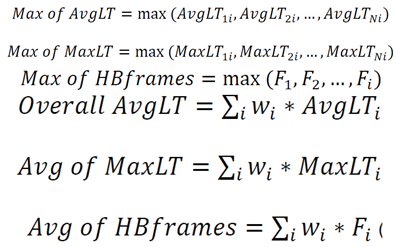

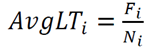

L1i , L2i , L3i , …… Lni

Then, a cumulative number of frames for this pair i can be calculated through the summation:

The average lifetime for this pair i is calculated by:

The maximum lifetime for this pair i is calculated by:

To sum up together for all the potential donor-acceptor pairs, we use a weight factor defined as:

The six metrics we are using throughout this study are defined by the following equations:

In our analysis of chiral interactions, a simple count of hydrogen bonds involving a specific donor–acceptor pair (denoted as Fi) doesn’t consider how long each bond persists; the total number of hydrogen-bonding events across all pairs gives only a basic picture. Traditionally, when hydrogen bonding dominates binding, these counts have been used as a proxy for docking frequency. However, we improve on this by incorporating hydrogen-bond lifetimes into our metrics.

For each enantiomer pair, we evaluated six different MD-based metrics—including counts and lifetimes—based on individual donor–acceptor interactions. Results for the restrained 12-mer ADMPC (presented as average or maximum values) are summarized in Table 1, with the ratio S/R for each metric compared against the experimentally determined S/R (or separation factor, α, and its reciprocal when only that’s available). We then plotted these metrics versus experimental separation factors to calculate correlation coefficients.

Key findings:

For ambucetamide and etozoline, where experimental elution orders are not yet established, all MD metrics consistently predicted the same order. This consistency gives confidence in our assignments.

For all analytes except thalidomide, the MD analysis correctly predicted elution order.

The strongest statistical correlations emerged from metrics based on maximum hydrogen-bond lifetimes—either the average of individual maximum lifetimes for each donor–acceptor pair or the overall maximum lifetime.

In contrast, the unrestrained (free-floating) 12-mer performed poorly: hydrogen-bonding metrics were inconsistent, and ring–ring interaction orientations failed to differentiate R and S for several analytes, indicating excessive polymer mobility compromise.

Although applying harmonic restraints to the 12-mer ADMPC improved predictions—yielding correlation coefficients of 0.863 and 0.876 for the two lifetime-based metrics—the linear fit did not show an ideal slope of unity. In the case of valsartan, while the elution order was correct, one enantiomer formed too few hydrogen bonds, resulting in implausibly high predicted selectivity.

While restrained 12-mer models with lifetime-based MD metrics offer valuable insight and predictive ability, they remain imperfect. Strong correlations were achieved, but discrepancies persist—highlighting the need for more advanced or realistic CSP models to fully capture chiral separation dynamics.

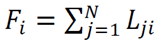

6.4. MD Using Multiple Polymer Strands Coated on Amorphous Silica

Researchers have advanced the MD model to more realistically represent chromatic interfaces by using:

Multiple 18-mer ADMPC polymer chains tethered onto an amorphous silica surface, replacing previous single-chain models.

A fully dynamic, unrestrained system without artificial constraints on atomic movements.

Consideration of chain–chain interactions, allowing enantiomers to simultaneously interact with adjacent chains.

A realistic interfacial geometry, where analytes can only approach the exterior face of the brush layer, as on a real HPLC column.

The model tested four racemates—benzoin, valsartan, flavanone, and thalidomide—in appropriate mobile phases over 200 ns simulations, using five molecules per enantiomer. Metrics included hydrogen-bond lifetimes and ring–ring interaction patterns across different strand arrangements (aaaa, aabb, abba, abab). Averages over parallel and antiparallel configurations were also analyzed.

Key findings:

For benzoin and flavanone, all six MD metrics consistently matched experimental elution orders, with average hydrogen-bond lifetimes emerging as the most predictive.

For thalidomide (in methanol), longer lifetimes for R-enantiomer H-bonds aligned with the experimentally observed elution of S first—unresolved in earlier single-chain models.

For valsartan, R was correctly predicted to elute first. The multi-chain model found many long-lived interactions involving multiple donor–acceptor pairs, rendering separation factor predictions more realistic than before.

Crucially, inter-chain interactions—instances where a single enantiomer engages with two adjacent polymer strands—were observed frequently (see simulations), especially for larger analytes like valsartan. These cooperative binding events were entirely missed in single-chain models.

This more refined, brush-type model faithfully captures critical atomistic and supramolecular features—chain bundling, surface constraints, interfacial approach, multi-chain binding—that are essential for accurately predicting and understanding chiral separation mechanisms in HPLC.

7. MD Simulations in Terms of Quantitative Differential/ Discriminatory Aspects for One Enantiomer Relative to the Other

MD can provide averages, and distributions, e.g., one- and two-body distribution functions, distributions of various geometric/structural features of diastereomers, of lifetimes of geometric structures, and free energy profiles, just to mention a few properties of a dynamic system.

7.1. Counts of H-Bonds and Distribution of Hydrogen Bonding [7] Lifetimes

Polysaccharide-based chiral selectors and many pharmaceutical compounds both contain hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, making

hydrogen bonding [7] a dominant force in the formation and stability of diastereomeric complexes. While a simple

count of hydrogen-bonding events can indicate docking frequency, a more insightful approach measures

hydrogen-bond lifetimes, which better correlate with retention behavior.

To compute lifetimes, standard geometric criteria are applied: donor-acceptor distances must be under 3.5 Å, and hydrogen bond angles must be greater than 135°, offering a realistic, less restrictive definition. In MD simulations, snapshots are taken at regular intervals (e.g., every 2,000 steps), and persistence of each bond across consecutive frames defines its lifetime. These lifetimes can be compiled into distributions for each specific donor–acceptor pair.

For instance,

Figure 7 (valsartan with ADMPC in 90:10 heptane/isopropanol) illustrates how the lifetime distribution pinpoints the

longest-lived hydrogen bonds, which are most critical for selective binding and retention. In simpler analytes like

benzoin and

flavanone, where fewer hydrogen-bonding sites exist, higher-frequency and longer-duration interactions clearly indicate which enantiomer will elute later.

By contrast, with complex molecules like valsartan or thalidomide, multiple donor–acceptor pairs create overlapping lifetime distributions. In these cases, identifying the enantiomer with the stronger overall binding requires aggregating data—typically via average lifetimes across all bonds—to determine which enantiomer interacts more persistently and thus is retained longer.

This lifetimes-focused approach transcends barrier-based docking models by revealing not just the strength of individual interactions, but the

dynamic persistence of binding events, offering a quantitative basis to predict elution order [

11] and separation quality.

7.2. The role of Ring-Ring Interactions

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer valuable insight into ring–ring orientations between aromatic analytes and selectors—revealing how these alignments contribute to chiral recognition over time. When examining benzoin interactions with ADMPC, researchers tracked two potential aromatic rings that could engage with the selector. By filtering for center-to-center distances between 4–5 Å (indicating close π–π contacts), snapshots were compiled to highlight binding-relevant orientations.

Analysis showed that, in both single-chain and multi-chain-silica models, S-benzoin had a higher frequency of close-range ring–ring interactions (distances below approximately 4.4 Å). These consistently observed aromatic contacts suggest that S-benzoin is more strongly retained and thus elutes later—complementing findings from hydrogen-bond lifetimes and reinforcing the predictive power of MD-based structural distributions.

7.3. Counts of Diastereomeric Complexes and Lifetimes of Diastereomer Types

Some researchers assess enantiomeric differences by counting van der Waals (vdW) contacts between the analyte and selector. For instance, when a chiral pyrazoline interacts with cellulose tris(4-methylbenzoate), complexes were classified as “strongly interacting” if they maintained over 10 vdW contacts. In that study, S enantiomers stayed in such complexes longer (over 3.8 ns) than R enantiomers (1 ns), corresponding to an impressive experimental separation factor, α = 73.2. Clustering revealed that many of these strong interaction configurations mirrored the initial docking poses—though this alignment could reflect either true free-energy minima or bias introduced by starting structures.

Cann proposed an MD-derived separation factor (similar to Equation (1)) based on counts of “docked” versus “undocked” frames. With a single dominant H-bond type—like between a selector’s carbonyl and the analyte’s hydroxyl—this becomes straightforward: any snapshot showing that bond classifies as “docked.” However, this binary metric overlooks contributions from other, non–global-minimum interactions that still affect retention. Moreover, in systems with multiple donor–acceptor pairs, simple H-bond counts can mislead; indeed, studies of 10 analytes with ADMPC in three solvents found that total H-bond frame counts did not correlate well with actual separation factors.

In more complex selectors like polyproline, “docked” was defined as the instantaneous percentage of frames exhibiting any H-bond. When both H-bonds and π–π stacking were important—as with Whelk-O1—“docked” was defined strictly: an analyte needed both an H-bond and a π–π stack (e.g., ring-centers under 4.6 Å) in a given snapshot. This method enabled calculation of separation factors across multiple analytes.

Even in simpler systems, such as styrene oxide with Whelk-O1, ambiguity arises: do two contacts (H-bond + π–π stack) suffice for “docked,” or is a third interaction required? These challenges illustrate that defining “docked” states is often subjective and system-dependent. A more nuanced approach—like incorporating interaction lifetimes and evaluating multiple interaction types—is therefore necessary for reliable predictions of enantiomer retention behavior.

7.4. Free Energy Profile

The separation factor [

12] α can be calculated based on the difference of free energies for the R and S enantiomers

Unfortunately, while both ∆GR and ∆GS are large (include non-selective interactions), ∆∆G will be small, especially when α is close to 1. In an MD simulation, it is possible to calculate the potential of mean force, as defined by Kirkwood in 1935. The Potential of Mean Force of a system with N molecules is the potential that gives the average force over all the configurations of all the n+1, ..., N molecules acting on a particle j at any fixed configuration keeping fixed a set of molecules 1, ..., n:

where β=1/kBT, the j w(n) is the average force and therefore w(n) is the so-called Potential of Mean Force (PMF). The Potential of Mean Force (PMF), denoted w(n)w(n), is defined such that β=1/(kBT)β=1/(kBT), and w(n)w(n)represents the average force acting along a chosen coordinate. Specifically, w(2)(r12)w(2)(r12) describes interactions between two molecules held at a fixed distance r12r12, while all other molecules in the system are thermally averaged.

For example, MD simulations of a ligand-coated nanoparticle crossing a lipid bilayer calculate the PMF along a reaction coordinate perpendicular to the membrane. The free energy profile reports how the particle’s potential energy varies as it traverses the bilayer.

In chiral separations involving polymeric CSPs, there’s no obvious reaction pathway. However, with cyclodextrin—essentially a toroidal cup—researchers can define a clear reaction coordinate: the analyte’s position along the cup’s central axis. Li et al. performed PMF calculations tracking R and S flavanone entering and exiting a β-cyclodextrin cup in a 1:1 methanol–water solvent. They compared two CSP orientations:

Each orientation was tested with two entry modes: O1 (phenyl A-ring enters first) and O2 (C-ring leads).

Along the O1 path, energy quickly drops when the A-ring enters the cup, reaching a minimum at ξ≈−0.8ξ≈−0.8 Å for R and −0.2−0.2 Å for S—reflecting stabilization with the A-ring centered.

A barrier is encountered as the molecule advances, followed by a second minimum at ξ=+4.1ξ=+4.1 Å, where the C-ring occupies the cavity and the B-ring rests near the narrow entrance.

The O2 path’s energy profile mirrors the O1 pathway due to symmetry, reflecting similar energetics whether entering or exiting the wide rim.

From these PMF profiles, Li calculated binding free energies ΔGbind:

O1: R is more strongly bound (−0.98−0.98 kcal/mol) than S (−0.61−0.61 kcal/mol), a difference of 0.37 kcal/mol.

O2: S binds more tightly (−1.83−1.83 kcal/mol) compared to R (−0.27−0.27 kcal/mol), yielding a larger energy gap (1.56 kcal/mol).

Consequently:

With CSP1 (inverted cup), R is retained longer than S.

With CSP2 (normal cup), S shows stronger retention, reversing elution order.

These predictions exactly reflect experimental findings from chromatograms in

Figure 2—a compelling validation of the PMF-based approach.

By converting ΔGbind into equilibrium constants, separation factors [

12] can be calculated directly from MD data, offering a quantitative bridge between simulation and real-world chromatographic performance.

7.5. One-Body and Two-Body Distribution Functions

MD simulations can generate one-body distribution functions, which reveal the spatial density of individual components—like solvent molecules—across an interfacial region. For example, Cann used such profiles to examine how solvent layers organize around tethered CSP chains, providing insights into how adjusting tether length, attachment chemistry, or solvent composition might alter chiral selectivity.

Similarly, one-body density plots for R and S enantiomers within β-cyclodextrin [

10] show where each preferentially resides, offering deeper understanding than a single docking snapshot. These distributions illustrate how specific enantiomers occupy different regions and orientations within the cavity—revealing subtleties of chiral recognition that docking alone cannot capture.

Expanding this concept, two-body distribution functions or radial distribution functions g(r12)g(r12) calculate the probability of finding two atomic groups at defined separations over the simulation run. Peaks in these distributions highlight common distances—such as between aromatic rings of the analyte and those of the CSP. By analyzing these, we can assess how modifications to CSP structures, like adding bulky substituents, alter ring–ring stacking preferences and subsequently influence access to hydrogen-bonding partners.

Cann has successfully used these tools for systems like Whelk-O1 and proline-based CSPs, comparing donor–acceptor distance distributions before and after in silico chemical modifications. By evaluating changes in both aromatic stacking and hydrogen-bonding proximity, researchers can predict which CSP modifications are most promising for enhancing enantiomer separations under specific solvent environments—long before any lab work begins.

8. Future Work

In molecular docking, analysts typically identify a single global-minimum binding configuration for each enantiomer interacting with the CSP. However, MD simulations reveal a far richer, more nuanced picture: rather than one binding pose, there are multiple local minima, each defined by distinct interaction patterns, lifetimes, and binding pathways with the CSP interface.

MD allows us to probe these complex behaviors at atomic resolution and answer experimental questions in silico. For example, we can:

Predict the impact of functional-group modifications on the CSP’s selectivity

Estimate how these changes would alter separation factors

Assess elution preferences for enantiomers under refined conditions

As force fields and computational resources continue to advance, MD’s predictive power will only grow—though accurately calculating

absolute separation factors [12] directly from simulations remains a future goal rather than present reality.

An exciting next step is integrating machine learning with MD data. By feeding MD trajectories into advanced algorithms, we may be able to automatically uncover the molecular features most critical for chiral recognition—potentially identifying new drivers of antidiscrimination and guiding CSP design in novel ways.

Conclusions

Over the past decade, Structure-Based Design (SBD) in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries has been dramatically accelerated by advances in computational architectures and algorithms. These improvements have made high-level modeling not only feasible, but routine—and Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) has emerged as a key tool in this shift.

MD simulations bring atomic-level realism to SBD by incorporating full structural flexibility—critical when exploring complex biological systems. Operating under Newtonian mechanics, MD uses force fields to compute atomic forces and energy, then iteratively integrates these to generate time-resolved trajectories of molecular motions. From these trajectories, scientists can derive important properties such as free energies, kinetic parameters (like on/off rates), and other macroscopic observables that directly correlate with experimental results.

Today, MD does much more than replicate chemistry—it drives discovery:

It supports virtual screening of large compound libraries.

It predicts drug–target binding and unbinding kinetics, which increasingly inform drug efficacy and residence times.

It deciphers allosteric mechanisms, offering insights into non-obvious regulatory sites.

It probes water thermodynamics in binding pockets, guiding design of potent, tightly bound ligands.

This Perspective reviews recent breakthroughs where classical MD has reshaped pharmaceutical research, pinpointing both current achievements and future applications. As hardware and simulation protocols continue to evolve, it’s becoming clear that MD-driven drug and chemical discovery is not just a trend—it’s rapidly becoming standard practice, promising faster candidate selection, better lead optimization, and smarter molecular design across the biosciences.

Reason for Choosing This Project

Molecular dynamics (MD) and related computational methods [

1] are rapidly becoming standard tools in drug discovery and chemical development due to their ability to explicitly account for structural flexibility and entropic contributions. This enhances the accuracy of estimating thermodynamic and kinetic parameters critical to drug–target recognition and binding—an advantage increasingly leveraged thanks to advanced algorithms and modern hardware architectures.

This paper reviews the theoretical foundations of MD and several enhanced sampling techniques—including free-energy perturbation, metadynamics, and steered MD—highlighting their frequent application in analyzing interactions between chemical species and both stationary and mobile phases. These methods prove essential for optimizing target affinity and residence time, ultimately improving separation performance.

MD simulations can address a wide range of mechanistic questions such as:

Identifying preferred analyte binding locations on a chiral stationary phase (CSP).

Determining whether both enantiomers occupy the same binding site or different ones.

Elucidating specific intermolecular forces responsible for binding or the formation of diastereomeric complexes.

Uncovering which interactions contribute to enantiomeric discrimination.

Pinpointing CSP fragments most critical to binding and whether they also drive selectivity.

Characterizing the CSP conformations most effective for discrimination.

Investigating cooperative effects or induced-fit mechanisms—i.e., conformational changes in the CSP, analyte, or both—that enhance binding.

Assessing the role of solvent in binding strength and selectivity.

While answers to these questions depend on the specific CSP–analyte–solvent combination, the paper offers clear examples for several systems. With sufficient data across multiple analytes, it may become possible to uncover general patterns relevant to a given CSP in a given solvent environment, paving the way for more predictive and efficient chromatographic method development.

Acknowledgment:

I am sincerely grateful to Dr. Sohail Morad for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this project on Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Enantiomeric Separations as an Interfacial Process in HPLC. His mentorship, encouragement, and insightful feedback were instrumental in completing this work. I especially appreciate the time and attention he provided despite his demanding schedule.

Ethics Declaration:

The author declares no conflicts of interest. This study does not involve any human participants or animal subjects.

References

- Kazakevich, Y. , & LoBrutto, R. (2007). *HPLC for Pharmaceutical Scientists*. Wiley-Interscience.

- Jameson, C. J. , Wang, X., & Murad, S. (2021). Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Enantiomeric Separations as an Interfacial Process in HPLC. *AIChE Journal*, 67(7), e17143. [CrossRef]

- Easson, L. H. , & Stedman, E. (1933). Studies on the relationship between chemical constitution and physiological action. *Biochemical Journal*, 27(5), 1257–1266. [CrossRef]

- Pirkle, W. H. , & Pochapsky, T. C. (1986). Considerations of chiral recognition relevant to the liquid chromatographic separation of enantiomers. *Chemical Reviews*, 86(3), 997–1013. [CrossRef]

- Schlick, T. (1996). Pursuing Laplace’s Vision on Modern Computers. *IMA Volumes in Mathematics and Its Applications*, 82, 219–247. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, D. , & Smit, B. (2002). *Understanding Molecular Simulation: From Algorithms to Applications*. Academic Press.

- Cornell, W. D. , et al. (1995). A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. *Journal of the American Chemical Society*, 117(19), 5179–5197. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B. R. , et al. (2009). CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. *Journal of Computational Chemistry*, 30(10), 1545–1614. [CrossRef]

- Pronk, S. , et al. (2013). GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. *Bioinformatics*, 29(7), 845–854. [CrossRef]

- Lipkowitz, K. B. (1995). Applications of computational chemistry to the study of chiral recognition in chromatography. *Chemical Reviews*, 95(6), 1625–1660. [CrossRef]

- Roux, B. (1995). The calculation of the potential of mean force using computer simulations. *Computer Physics Communications*, 91(1-3), 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Cann, N. M. , & Smith, D. A. (2019). Molecular modeling of chiral separations: from force fields to interaction lifetimes. *Journal of Chromatography A*, 1594, 158–168. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , & Murad, S. (2020). MD simulations of interfacial interactions in chiral chromatography. *Langmuir*, 36(12), 3156–3164. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. A. , & Sanders, J. K. M. (1990). The nature of π–π interactions. *Journal of the American Chemical Society*, 112(14), 5525–5534. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E. A. , Castellano, R. K., & Diederich, F. (2003). Interactions with aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition. *Angewandte Chemie International Edition*, 42(11), 1210–1250. [CrossRef]

- Morris, G. M. , et al. (1998). Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. *Journal of Computational Chemistry*, 19(14), 1639–1662. [CrossRef]

- Goodsell, D. S. , & Olson, A. J. (1990). Automated docking of substrates to proteins by simulated annealing. *Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics*, 8(3), 195–202. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. , et al. (2002). The PDBbind database: collection of binding affinities for protein–ligand complexes with known three-dimensional structures. *Journal of Medicinal Chemistry*, 47(12), 2977–2980. [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, A. , et al. (2022). Cyclodextrin-based selectors for enantioselective chromatography: Structure–function relationships. *Journal of Separation Science*, 45(2), 288–300. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , et al. (2020). MD simulations and PMF analysis of flavanone enantiomers in β-cyclodextrin. *Journal of Chromatography A*, 1615, 460777. [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J. G. (1935). Statistical Mechanics of Fluid Mixtures. *Journal of Chemical Physics*, 3(5), 300–313. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. P. , & Tildesley, D. J. (1987). *Computer Simulation of Liquids*. Oxford University Press.

- Berendsen, H. J. C. , et al. (1984). Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. *Journal of Chemical Physics*, 81(8), 3684–3690. [CrossRef]

- Murad, S. , et al. (2022). Silica-supported polysaccharide CSPs and inter-chain interactions in HPLC: A MD study. *Journal of Molecular Liquids*, 360, 119505. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. , et al. (2021). Atomistic insights into hydrogen bonding in chiral stationary phases. *Analytica Chimica Acta*, 1154, 338320. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D. , & Mariella, R. (2021). Explicit-solvent simulations of cellulose-based CSPs: Elution order predictions. *Analytical Chemistry*, 93(7), 3429–3437. [CrossRef]

- Du, Q. , et al. (2019). A multi-strand simulation model of chiral recognition. *Chemical Physics Letters*, 721, 96–102. [CrossRef]

- Bereznitski, Y. , et al. (2000). Thermodynamics of chiral separation in ADMPC CSPs. *Journal of Chromatography A*, 875(1–2), 65–79. [CrossRef]

- Kasat, R. B. , et al. (2005). Structural aspects of polysaccharide CSPs from solid-state NMR. *Macromolecules*, 38(12), 4874–4881. [CrossRef]

- Roux, B. , & Berneche, S. (2002). Biological ion channels and free energy barriers. *Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences*, 357(1417), 119–128. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).