Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

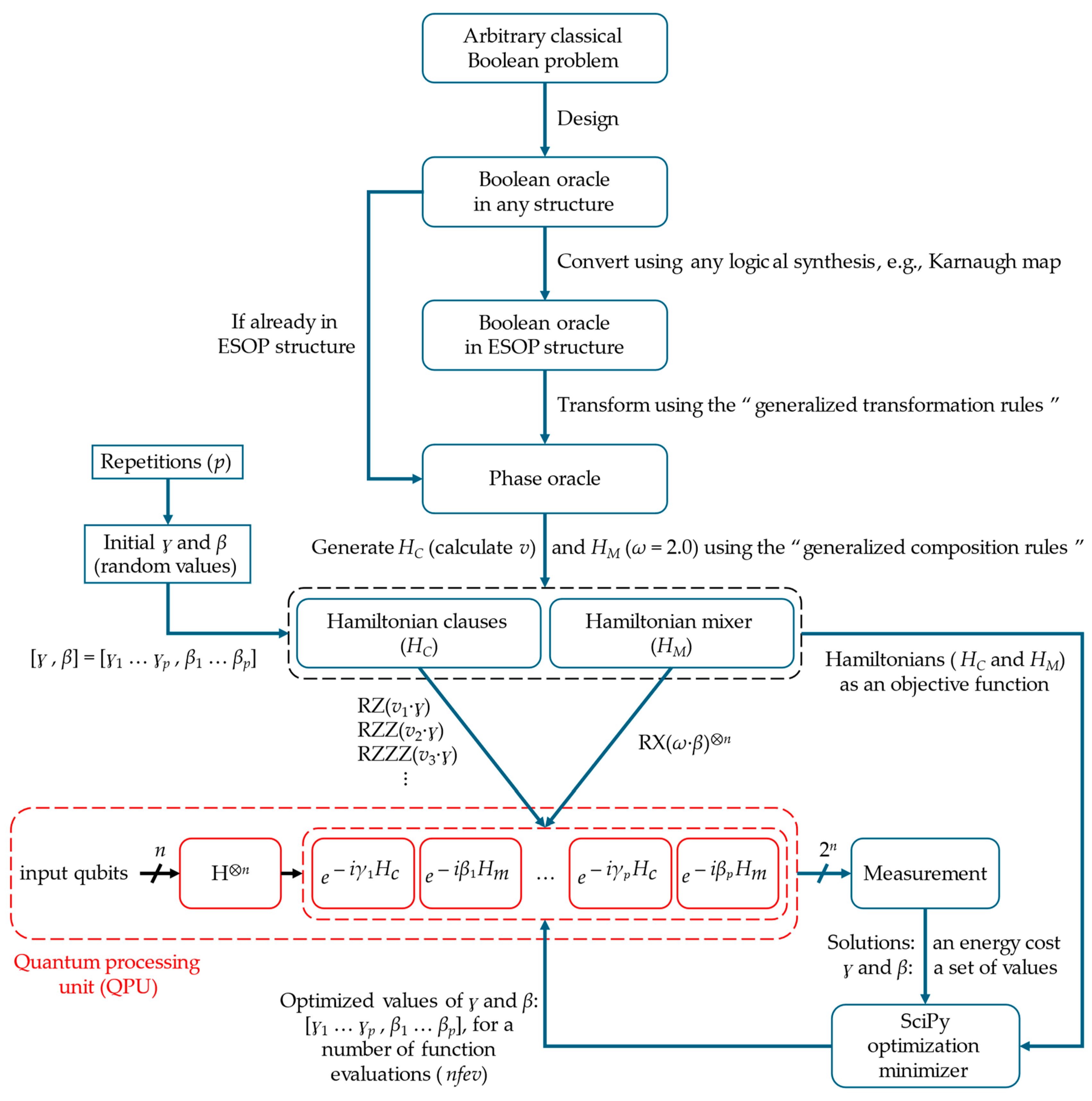

- An arbitrary classical Boolean problem is constructed as a quantum Boolean oracle [8,21]. This constructed oracle can be expressed in arbitrary logical structures, such as Product-Of-Sums (POS) [22,23], Sum-Of-Products (SOP) [22,24], Exclusive-or Sum-Of-Products (ESOP) [25,26], XOR-Satisfiability (CNF-XOR SAT and DNF-XOR SAT) [27,28], Algebraic Normal Form (ANF) (or Reed-Muller expansion) [29,30], just to name a few.

- This constructed oracle (in any logical structure) is converted into its equivalent quantum Boolean oracle in ESOP structure, unless it was initially constructed in ESOP structure.

- The Hamiltonians (HC and HM) of QAOA are then generated from this transformed quantum Phase oracle, based on our modified composition rules originally presented by Hadfield [31].

- The above-mentioned optimization operational concurrencies between a QPU and a minimizer are performed for the generated HC and HM, until finding all optimized approximated solutions. Notice that, in [20], the SciPy optimization minimizer [32] is performed using the constrained optimization by linear approximation (COBYLA) algorithm [14,16,32].

2. Methods

2.1. The Methodology of BHT-QAOA

| Rule 1: | A Feynman (CX) gate is transformed into a Pauli-Z (Z) gate, when Equation (1) stated below is a solution-satisfiable, where j is the index of an input qubit (q). The left side of Equation (1) is the Boolean-based output of a CX gate, and its right side is the phase-inverted output of a Z gate. | |

|

|

(1) | |

| Rule 2: | A Toffoli gate is transformed into a controlled-Z (CZ) gate, when Equation (2) stated below is a solution-satisfiable, where j and k are the indices of input qubits (q). The left side of Equation (2) is the Boolean-based output of a Toffoli gate, and its right side is the phase-inverted output of a CZ gate. | |

|

|

(2) | |

| Rule 3: | An n-bit Toffoli gate is transformed into an (n–1)-bit multi-controlled Z (MCZ) gate, when Equation (3) stated below is a solution-satisfiable, where j is the index of an input qubit (q) and n ≥ 3 qubits (q + fqubit). The left side of Equation (3) is the Boolean-based output of an n-bit Toffoli gate, and its right side is the phase-inverted output of an (n–1)-bit MCZ gate. | |

|

|

(3) | |

2.2. The Architecture of BHT-QAOA

- HC and HM (in a number of p), as the “objective function” needs to be minimized.

- Measured solutions of BHT-QAOA, as the “energy cost” of the objective function.

- Previously calculated ɣ and β, as their “numerical values” need to be optimized.

2.3. The Optimization Approximation Algorithms

3. Results and Discussion

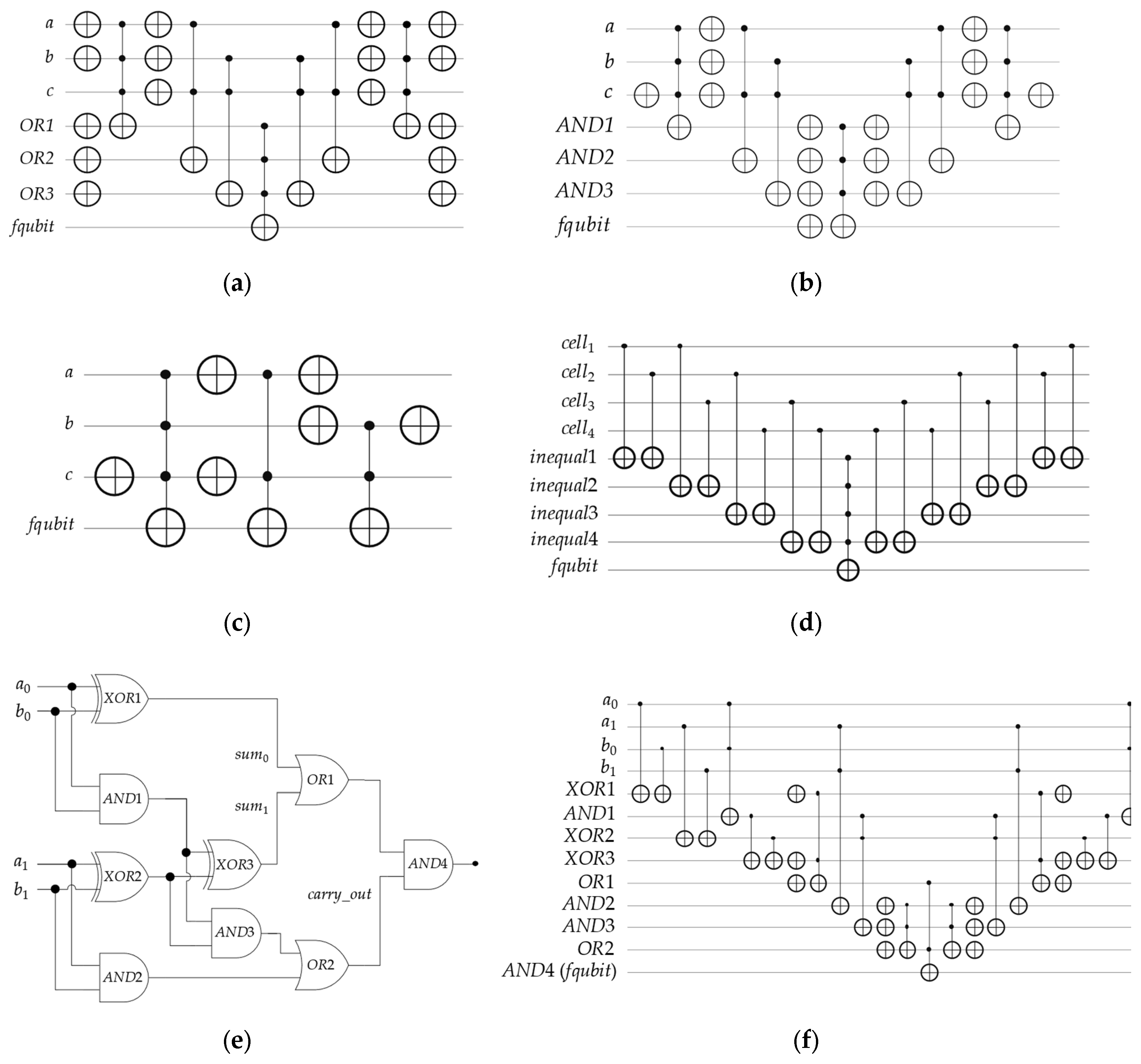

- An arbitrary Boolean problem in POS structure, as stated in Equation (4) and shown in Figure 2a.

- 2.

- An arbitrary Boolean problem in SOP structure, as stated in Equation (5) and illustrated in Figure 2b.

- 3.

- An arbitrary Boolean problem in ESOP structure, as stated in Equation (6) and shown in Figure 2c.

- 4.

- 5.

- A 4-bit conditioned half-adder (HA) digital circuit, which is ORing two 1-bit sums and then ANDing them with one 1-bit carry-out, as stated in Equation (8) and illustrated in Figure 2e,f.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goemans, M.X.; Williamson, D.P. .878-approximation algorithms for max cut and max 2sat. In Proc. of the Twenty-Sixth Ann. ACM Symp. on Theory of Computing, 1994, pp. 422–431.

- Rendl, F.; Rinaldi, G.; Wiegele, A. Solving max-cut to optimality by intersecting semidefinite and polyhedral relaxations. Mathematical Programming 2010, 121, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, E.; Goldstone, J.; Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv Preprint 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, E.; Goldstone, J.; Gutmann, S.; Neven, H. Quantum algorithms for fixed qubit architectures. arXiv Preprint 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proc. of the 28th Ann. ACM Symp. on Theory of Computing, 1996, pp. 212–219.

- Grover, L.K. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Physical Review Letters 1997, 79, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A framework for fast quantum mechanical algorithms. In Proc. of the 30th Ann. ACM Symp. on Theory of Computing, 1998, pp. 53–62.

- Al-Bayaty, A.; Perkowski, M. A concept of controlling Grover diffusion operator: a new approach to solve arbitrary Boolean-based problems. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 23570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, C.; Wang, H.; Bäck, T.; Dunjko, V. Unsupervised strategies for identifying optimal parameters in quantum approximate optimization algorithm. EPJ Quantum Technology 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amosy, O.; Danzig, T.; Lev, O.; Porat, E.; Chechik, G.; Makmal, A. Iteration-free quantum approximate optimization algorithm using neural networks. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, R.; Lotshaw, P.C.; Ostrowski, J.; Humble, T.S.; Siopsis, G. Multi-angle quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtz, J.; Lykov, D. Fixed-angle conjectures for the quantum approximate optimization algorithm on regular MaxCut graphs. Physical Review A 2021, 104, 052419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E. Performance of the quantum approximate optimization algorithm on the maximum cut problem. arXiv Preprint 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pendás, M.; Combarro, E.F.; Vallecorsa, S.; Ranilla, J.; Rúa, I. F. A study of the performance of classical minimizers in the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2022, 404, 113388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.J.D. Advances in Optimization and Numerical Analysis; Gomez, S., Hennart, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, M.J.D. A view of algorithms for optimization without derivatives. Mathematics Today-Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications 2007, 43, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo, M.; Arrasmith, A.; Babbush, R.; Benjamin, S.C.; Endo, S.; Fujii, K.; McClean, J.R.; Mitarai, K.; Yuan, X.; Cincio, L.; Coles, P.J. Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wecker, D.; Hastings, M. B.; Troyer, M. Progress towards practical quantum variational algorithms. Physical Review A 2015, 92, 042303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, J.; Chen, H.; Cao, S.; Picozzi, D.; Setia, K.; Li, Y.; Grant, E.; Wossnig, L.; Rungger, I.; Booth, G.H.; Tennyson, J. The variational quantum eigensolver: a review of methods and best practices. Physics Reports 2022, 986, 1–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayaty, A.; Perkowski, M. BHT-QAOA: the generalization of quantum approximate optimization algorithm to solve arbitrary Boolean problems as Hamiltonians. Entropy 2024, 26, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figgatt, C.; Maslov, D.; Landsman, K.A.; Linke, N.M.; Debnath, S.; Monroe, C. Complete 3-qubit Grover search on a programmable quantum computer. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakerly, J.F. Digital Design: Principles and Practices, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.X.; Huang, W. A note on the invariance principle of the product of sums of random variables. Electronic Communications in Probability 2007, 12, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, R.; Tran, D.Q. Optimized synthesis of sum-of-products. In IEEE Thirty-Seventh Asilomar Conf. on Signals, Systems & Computers, 2003, pp. 867–872.

- Mishchenko, A.; Perkowski, M. Fast heuristic minimization of exclusive sums-of-products. In Proc. RM’2001 Workshop, 2001, pp. 242–250.

- Sasao, T. EXMIN2: a simplification algorithm for exclusive-or-sum-of-products expressions for multiple-valued-input two-valued-output functions. IEEE Trans. on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 1993, 12, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimi, M.; Kanoria, Y.; Kraning, M.; Montanari, A. The set of solutions of random XORSAT formulae. In Proc. of the 23rd Ann. ACM-SIAM Symp. on Discrete Algorithms, 2012, pp. 760–779.

- Soos, M.; Meel, K.S. BIRD: engineering an efficient CNF-XOR SAT solver and its applications to approximate model counting. In Proc. of the AAAI Conf. on Artificial Intelligence, 2019, 33, pp. 1592–1599.

- Stankovic, R.S.; Sasao, T. A discussion on the history of research in arithmetic and Reed-Muller expressions. IEEE Trans. on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2001, 20, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurgalin, S.; Borzunov, S. Concise Guide to Quantum Computing: Algorithms, Exercises, and Implementations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield, S. On the representation of Boolean and real functions as Hamiltonians for quantum computing. ACM Trans. on Quantum Computing (TQC) 2021, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrijsen, W.; Tudor, A.; Müller, J.; Iancu, C.; De Jong, W. Classical optimizers for noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices. In 2020 IEEE Int. Conf. on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), 2020, pp. 267–277.

- Yuan, Y.X. A modified BFGS algorithm for unconstrained optimization. IMA Journal of Numerical Analysis 1991, 11, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.H. Convergence properties of the BFGS algoritm. SIAM Journal on Optimization 2002, 13, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Byrd, R.H.; Lu, P.; Nocedal, J. Algorithm 778: L-BFGS-B: Fortran subroutines for large-scale bound-constrained optimization. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software (TOMS) 1997, 23, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.C.; Nocedal, J. On the limited memory BFGS method for large scale optimization. Mathematical Programming 1989, 45, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, C.; Li, J. Improved SQP and SLSQP algorithms for feasible path-based process optimisation. Computers and Chemical Engineering 2024, 188, 108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnans, J.F.; Gilbert, J.C.; Lemaréchal, C.; Sagastizábal, C.A. Numerical Optimization: Theoretical and Practical Aspects; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ragonneau, T.M. Model-Based Derivative-Free Optimization Methods and Software. PhD Thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ebendt, R.; Fey, G.; Drechsler, R. Advanced BDD Optimization; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wille, R.; Drechsler, R. Effect of BDD optimization on synthesis of reversible and quantum logic. Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 2010, 253, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayaty, A.; Perkowski, M. COVID-19 features detection using machine learning models and classifiers. In The Science behind the COVID Pandemic and Healthcare Technology Solutions; Adibi, S., Rajabifard, A., Shariful Islam, S.M., Ahmadvand, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 15, pp. 379–403. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Mu, B.; Zheng, H. Link between and comparison and combination of Zhang neural network and quasi-Newton BFGS method for time-varying quadratic minimization. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2013, 43, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tan, M. Tuning SVM parameters by using a hybrid CLPSO–BFGS algorithm. Neurocomputing 2010, 73, 2089–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.C.; Nocedal, J. On the limited memory BFGS method for large scale optimization. Mathematical Programming 1989, 45, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Elyasi, S.N.; Yahyavi, M. Implementation and measurement of quantum entanglement using IBM quantum platforms. Physica Scripta 2024, 99, 045121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, R.; Van Meter, R.; Naveh, Y. IBM’s Qiskit tool chain: working with and developing for real quantum computers. In 2019 Design, Automation and Test in Europe Conf. & Exhibition (DATE), 2019, pp. 1234–1240.

- Georgopoulos, K.; Emary, C.; Zuliani, P. Modeling and simulating the noisy behavior of near-term quantum computers. Physical Review A 2021, 104, 062432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Yu, K.; Lim, H.; Jin, D.; Choi, D. Quantum amplitude estimation algorithms on IBM quantum devices. In Quantum Communications and Quantum Imaging XVIII, 2020, 11507, pp. 49–60.

- Farrell, R.C.; Illa, M.; Ciavarella, A.N.; Savage, M.J. Scalable circuits for preparing ground states on digital quantum computers: the Schwinger model vacuum on 100 qubits. PRX Quantum 2024, 5, 020315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Quantum Platform. Available online: https://quantum.ibm.com/services/resources?tab=systems (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Simonis, H. Sudoku as a constraint problem. In CP Workshop on Modeling and Reformulating Constraint Satisfaction Problems, 2005, pp. 13-27.

- Lynce, I.; Ouaknine, J. Sudoku as a SAT problem. In Proc. of the 9th Symp. on Artificial Intelligence and Mathematics (AI&M), 2006.

| Rules | Gate | Type | g(x) | Hg |

| Rule 1 | Z | Phase |

|

|

| Rule 2 | CZ | Phase |

|

|

| Rule 3 | MCZ | Phase |

|

|

| Rule 4 | X | Phase |

|

Invert signs (±) of all jth qubits in ZQ |

| Applications | BFGS | L-BFGS-B | SLSQP | COBYLA | COBYQA |

| POS | 27 | 21 | 30 | 49 | 38 |

| SOP | 90 | 185 | 181 | 296 | 165 |

| ESOP | 75 | 100 | 108 | 379 | 123 |

| 2×2 Sudoku | 80 | 115 | 61 | 515 | 124 |

| 4-bit HA circuit | 70 | 85 | 71 | 99 | 93 |

| Applications | BFGS | L-BFGS-B | SLSQP | COBYLA | COBYQA |

| POS | 90.1 | 91.1 | 90.7 | 88.3 | 88.0 |

| SOP | 92.4 | 90.0 | 87.7 | 93.7 | 89.9 |

| ESOP | 85.5 | 87.6 | 86.4 | 80.4 | 80.6 |

| 2×2 Sudoku | 71.8 | 69.8 | 71.3 | 68.7 | 71.7 |

| 4-bit HA circuit | 57.3 | 57.7 | 55.9 | 55.5 | 52.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).