Submitted:

30 August 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Description

2.1. Database

- objects (samples) ,

- each object () is defined by criteria (variables) with values in linearly ordered domains with and ; if some value (, ) is either missing or uncertain, then its value is recorded as ∞,

- weights in with , where each () quantifies the importance of the criterion ; if for all , then all criteria are equally important; a criterion is ignore if .

2.2. Distance Metrics

- Logical Boolean domain: , where .

- Logical non-Boolean domain: , where and .

- Numerical domain with natural values: , where .

- Numerical domain with rational values: , where .

- Binary code: , where the domain consists of all binary strings of length n, and for all , , ,

2.3. Tasks Specification

- Task 1:

-

Calculate the distance (or similarity metric) between the new object and each object in Table 2.If the distance corresponding to is , then

- Task 2:

- Given a threshold , calculate all objects at a distance at most to x.

- Task 3:

- Calculate the probability of a new object belonging to a labelled class (e.g. low risk vs. high risk) using a threshold and Table 2.

- Task 4:

- Rank the criteria in Table 2 and calculate the marker or markers criterion/criteria that are the most important/ones.

- Task 5:

- Assign alternative weights to criteria.

- Task 6:

- Test the data accuracy and method for Task 4.

2.4. Tasks Solutions

- Compute the distances between each object in Table 2 and , so obtain a vector with n non-negative real components .

- For each , compute the distances taking into consideration all criteria in Table 2 except: obtain the vector .

- Compute the distances between , using the formulaand sort them in increasing order. The criterion is a marker if , for every .

2.5. An Example

2.6. Complexity Estimation of the SAIN Method

3. Survival Analysis in SAIN

3.1. Data and Tasks

- Table 17 in which the first column lists the patients treated for the same disease with the same method under strict conditions, and the last column records the times till the patients’ deaths.

- Table 18, which includes the record of the new patient p.

- A threshold which defines the acceptable similarity between p and the relevant ’s in the Survival database (i.e. ).

3.2. Tasks Solutions

-

For Task 1,

- (a)

- Compute the set of patients that are similar up to to p:

- (b)

- Using , compute the probability that p will survive the time :

- (c)

- Compute the life expectancy of p using the formula:

- For Task 2, calculate the probability that the life expectancy of p is at least time T:

3.3. An Example

-

For , , that is the entire database. Then

- (a)

- ,

- (b)

- i.

- ,

- ii.

- ,

- iii.

- ,

- iv.

- ,

- v.

- ,

- vi.

- ,

- vii.

- ,

- viii.

- .

- (c)

- i.

- ,

- ii.

- ,

- iii.

- ,

- iv.

- ,

- v.

- ,

- vi.

- ,

- vii.

- ,

- viii.

- ,

We can calculate other probabilities, for example, . -

For , . Then

- (a)

- ,

- (b)

- i.

- ,

- ii.

- ,

- iii.

- ,

- iv.

- ,

- v.

- ,

- (c)

- i.

- ,

- ii.

- ,

- iii.

- ,

- iv.

- ,

- v.

- .

Similarly, we can calculate the probabilities , .

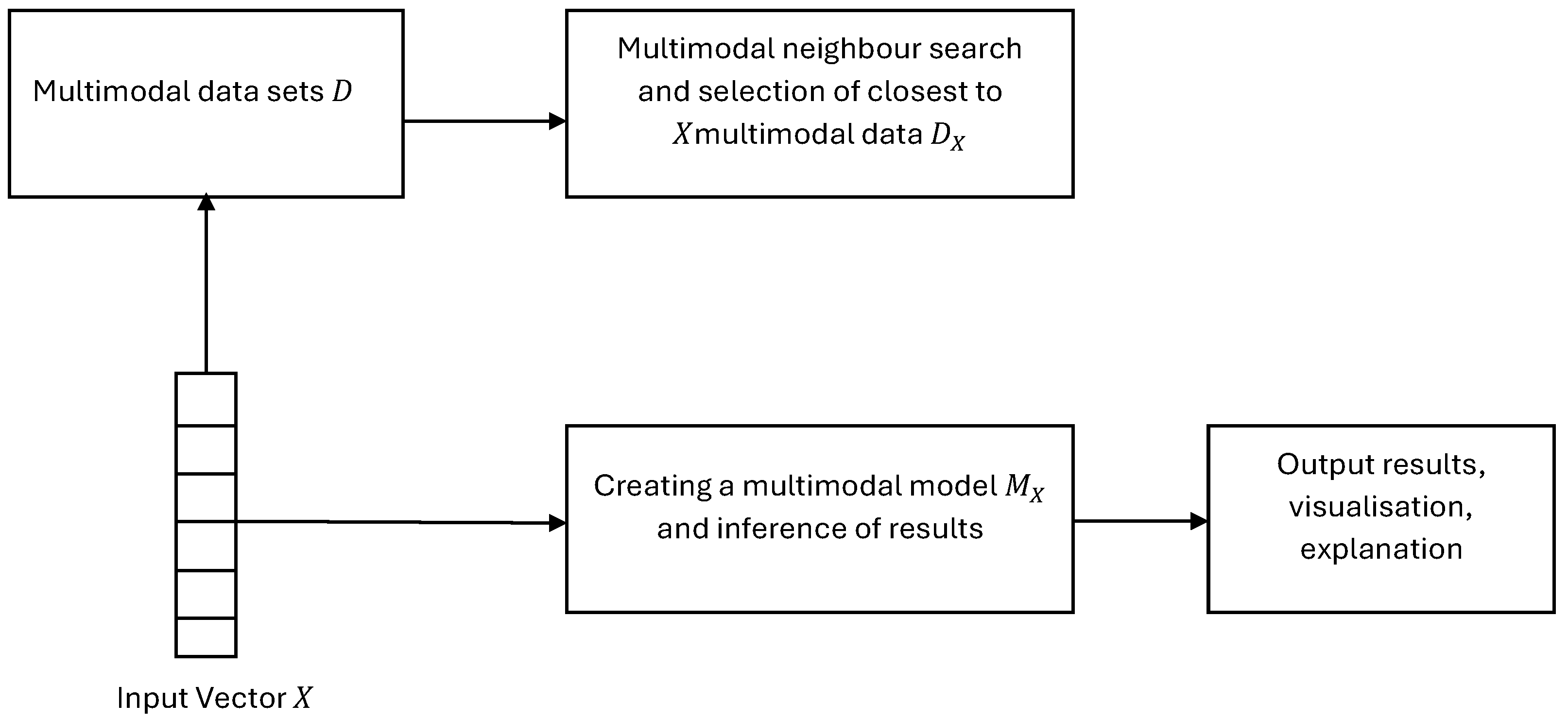

4. SAIN: A Modular Diagram and Functional Information Flow

- Multimodal data of a new object X.

- An existing repository D of multimodal data of many objects, labelled with their outcome.

- A module of algorithms for searching in the database D and based on the distance between X and each object in D.

- Defining a subset from D, so that X is closer to the objects in based on a given threshold.

- A module of algorithms for building a model in .

-

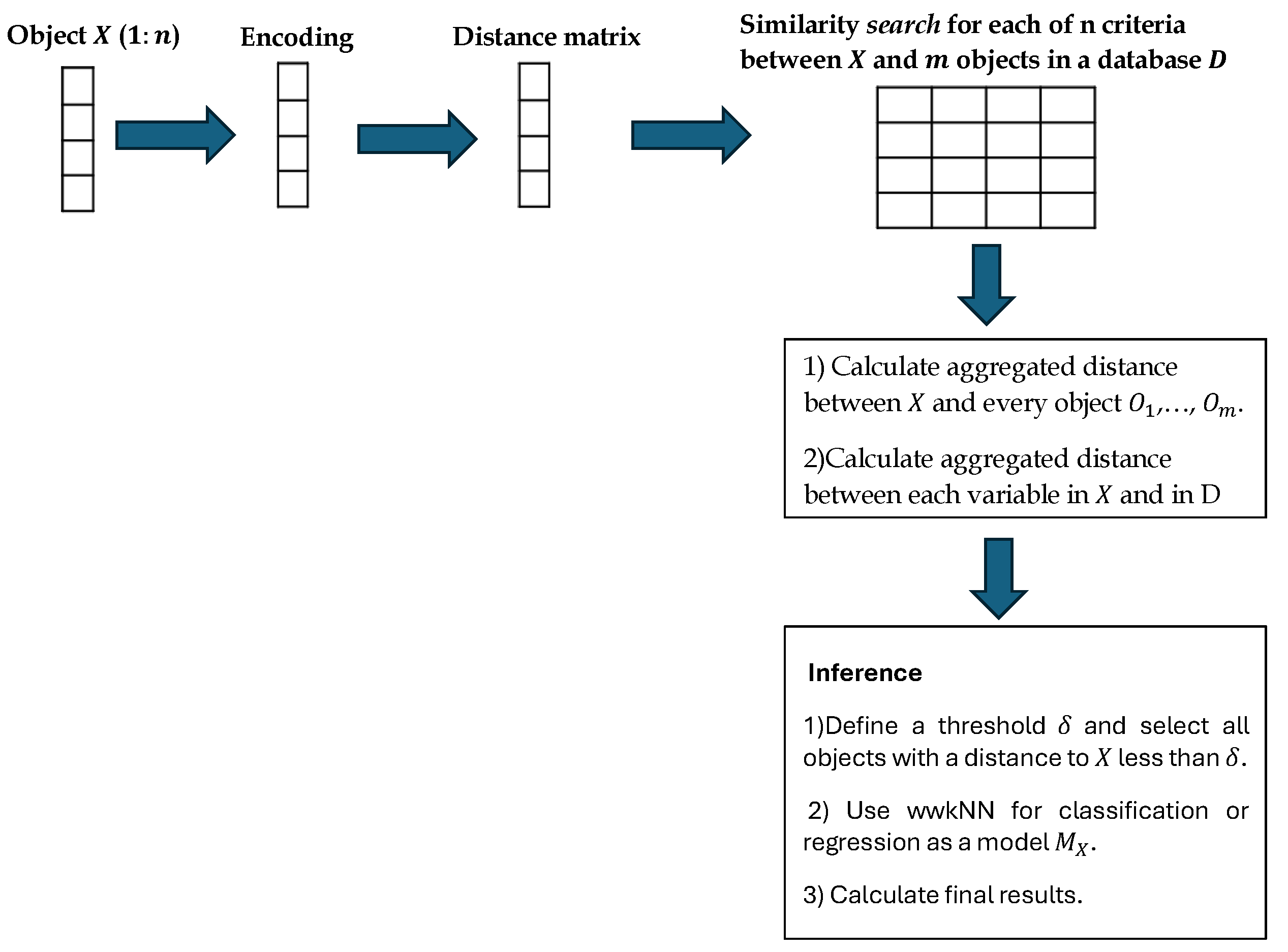

An inference algorithm to derive the output for X from the model and to visualise it for explanation purposes. Figure 1 gives a modular view of the SAIN framework and Figure 2 shows the information processing flow:

- (a)

- Encoding the multimodal data of X and D. -

- (b)

- Choosing a distance matrix and similarity search in the data set D.

- (c)

- Calculating the aggregated difference between the new data vector X and the closest vectors in .

- (d)

- Creating a model in .

- (e)

- Applying inference by calculating the for each class (or output value), using the wwkNN method in [5].

- (f)

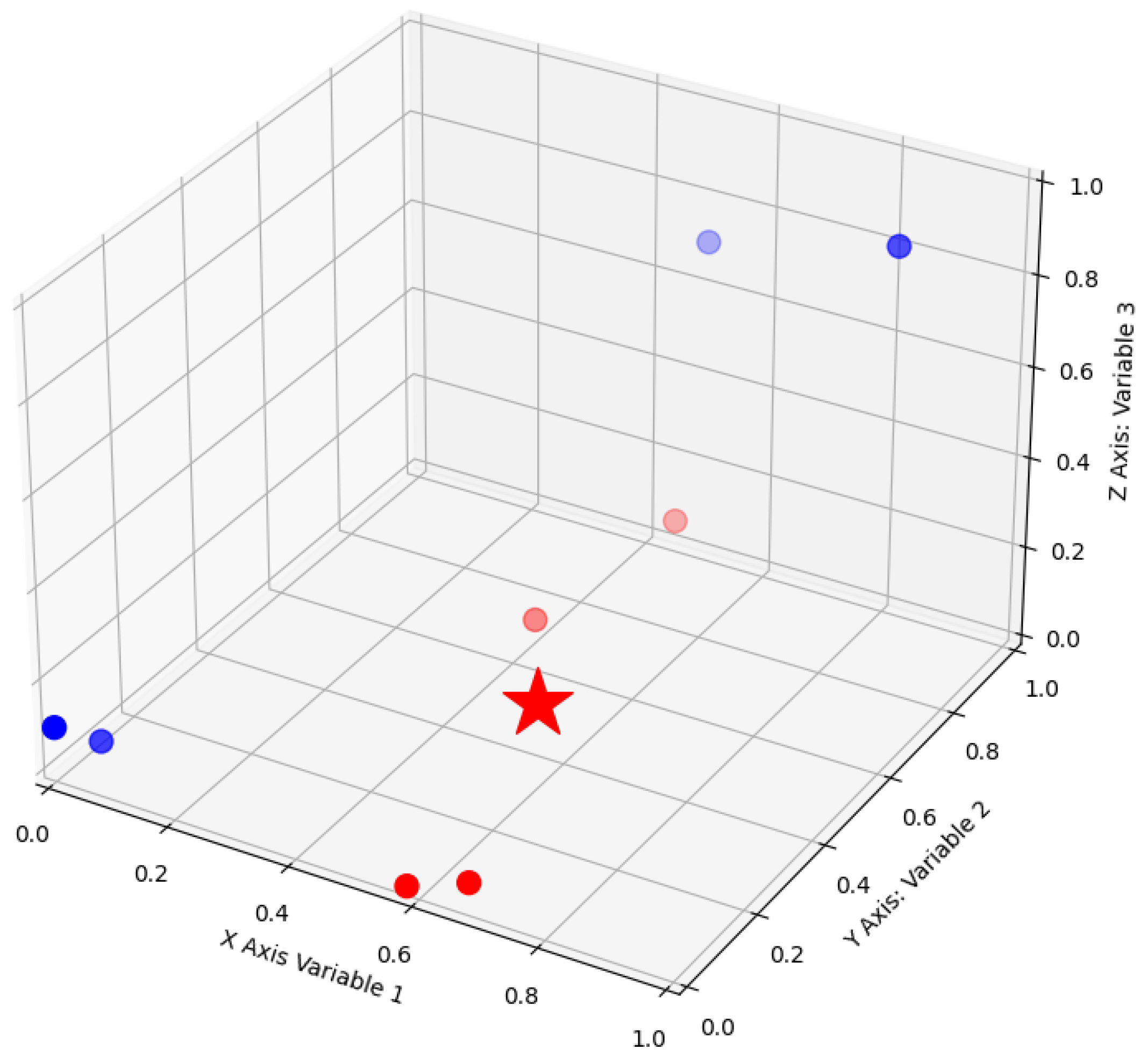

- Reporting and visualisation of results of the individual model Mx. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

5. Case Studies for Medical Diagnosis and Prognosis

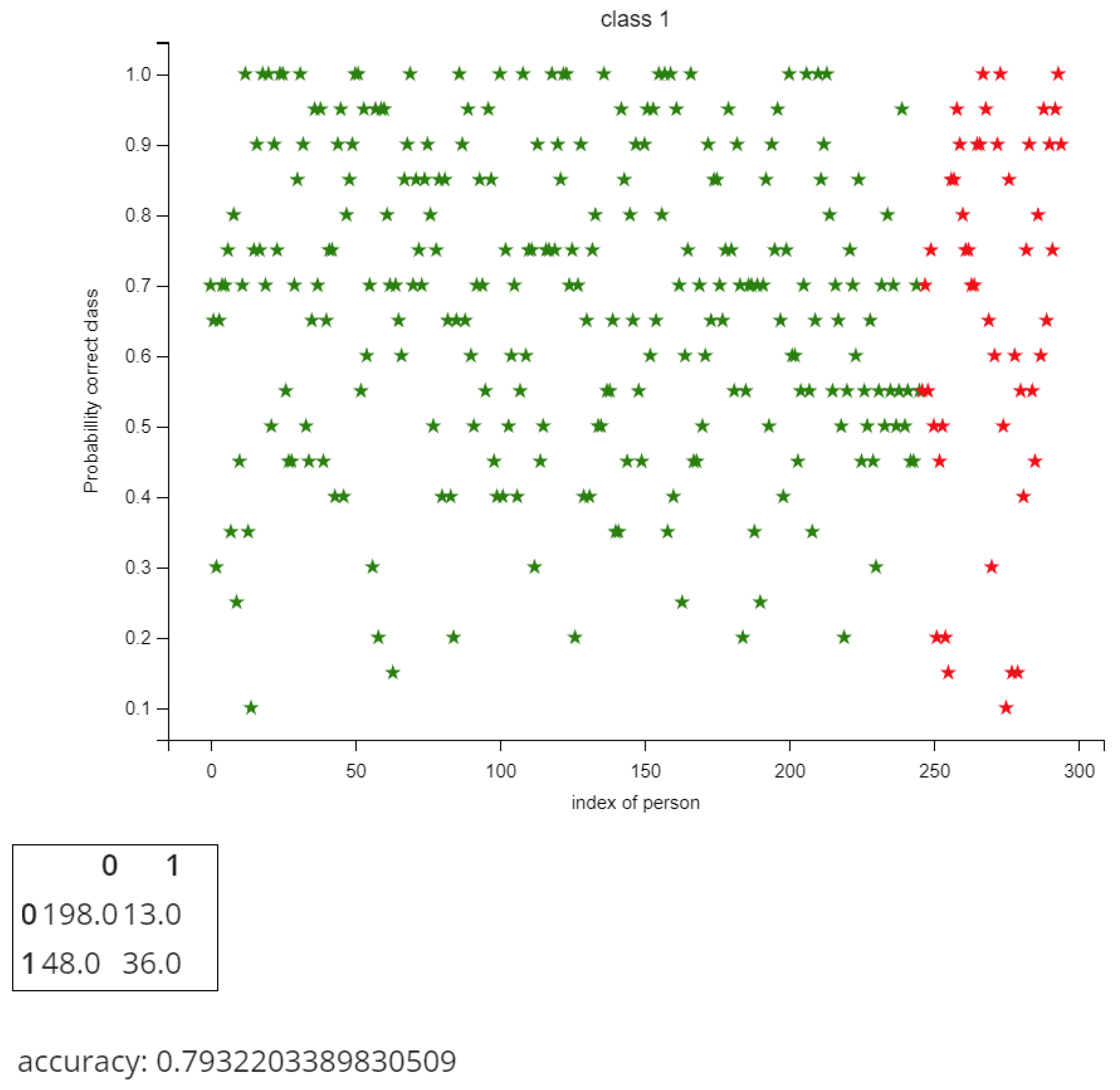

5.1. Heart Disease Diagnosis

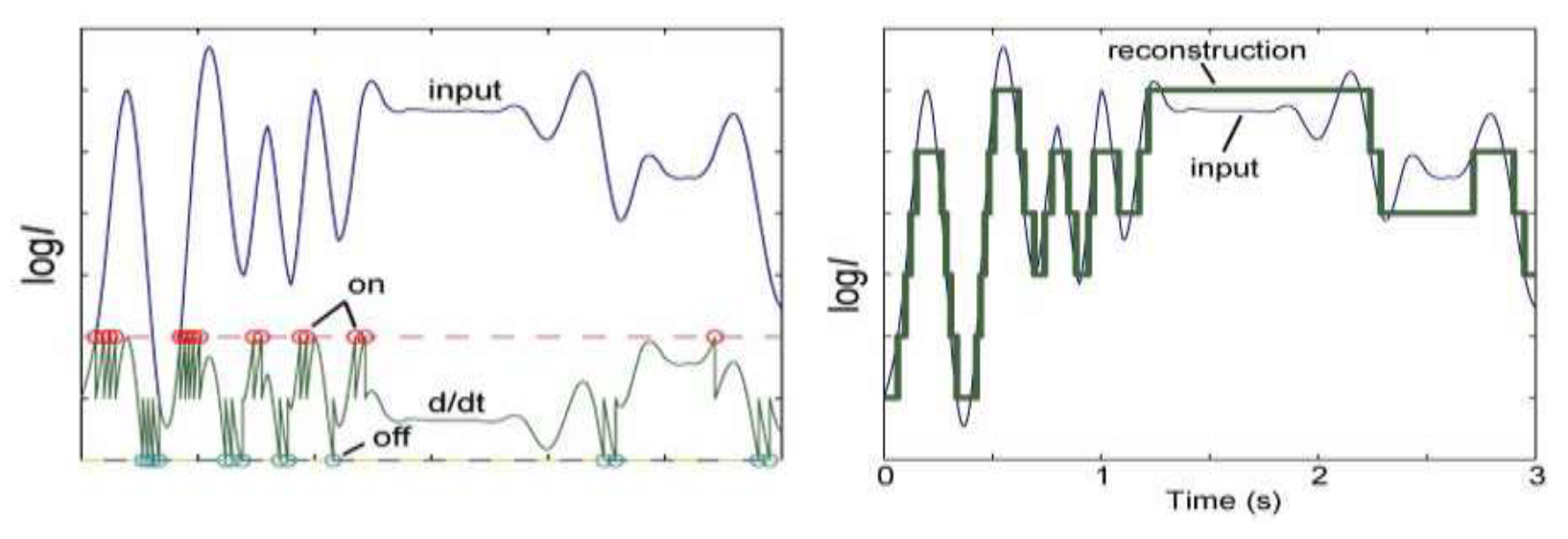

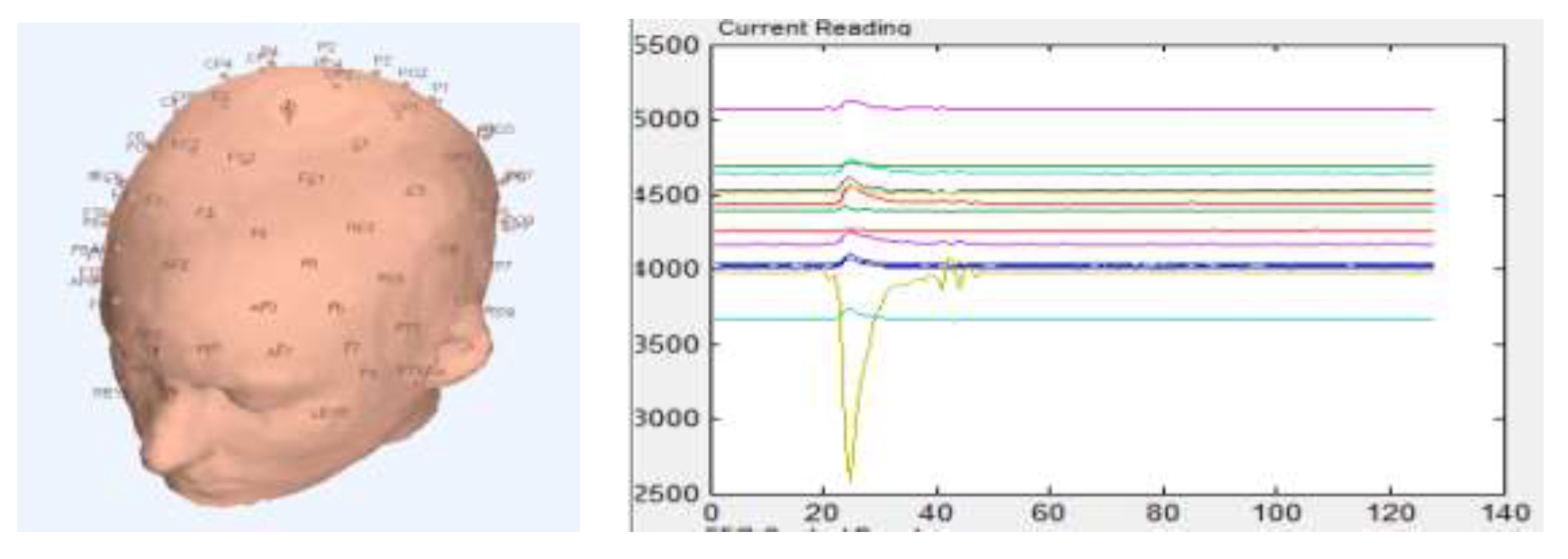

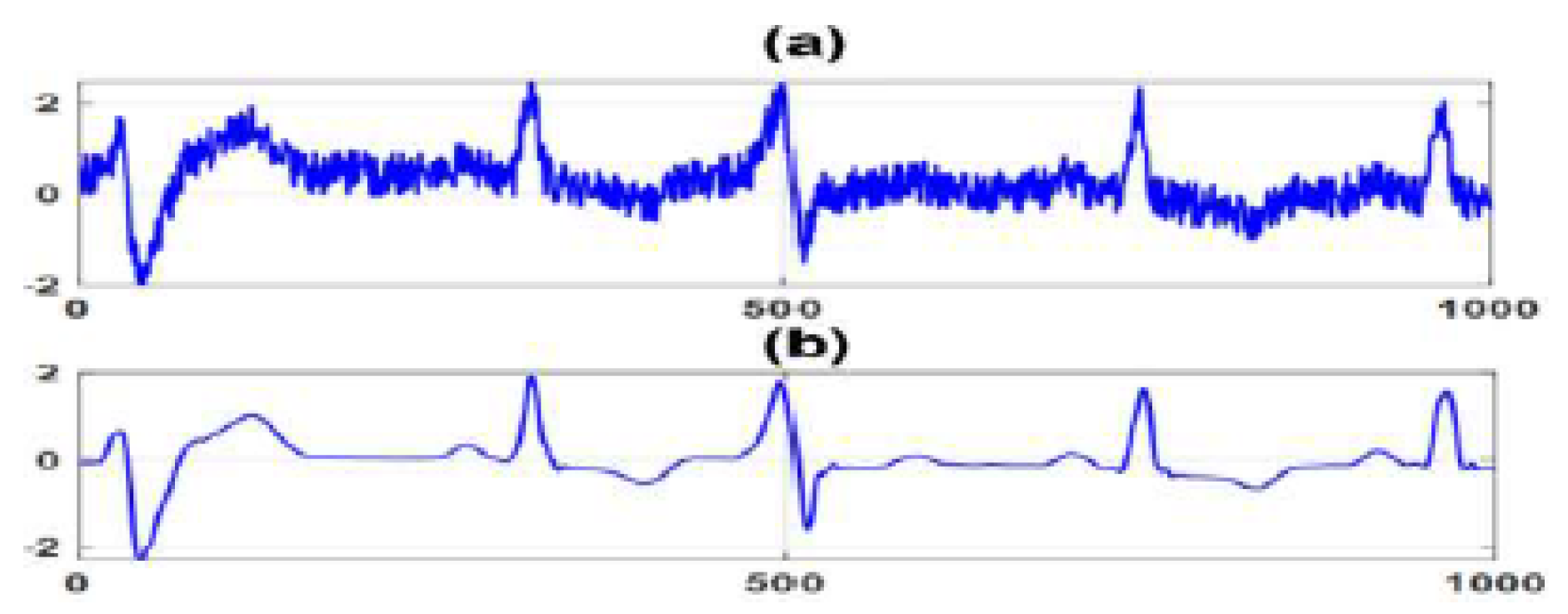

5.2. Time Series Classification

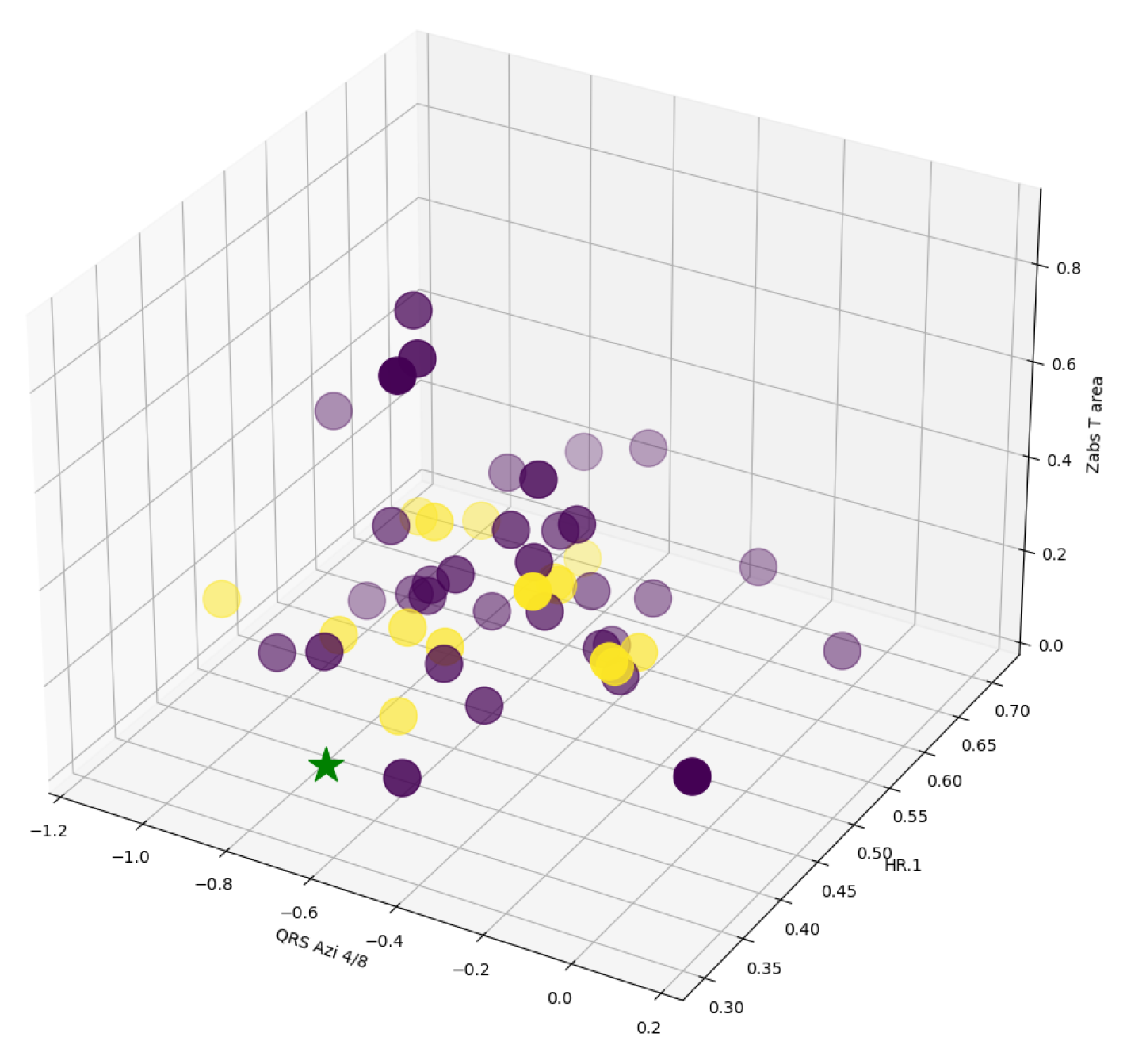

5.3. Predicting Longevity in Cardiac Patients

- demographics, risk factors, disease states, medication and deprivation scores,

- echocardiography, cardiac ultrasound measurements,

- advanced ECG measurements,

6. Data and Software Availability

7. Conclusions

- The method is suitable for multimodal data searches in heterogeneous data sets, e.g., numbers, text, images, sound, categorical data;

- It is suitable for personalised model creation to classify or predict specific outcomes based on multimodal and heterogeneous data.

- It uses a similarity measure based on multicriteria metrics. In this way, inaccurate measurement of similarity on a large number of heterogeneous variables is avoided.

- Its search is fast even on large data sets and includes advanced personalised searches with multiple parameters and features;

- It facilitates multiple solutions with corresponding probabilities;

- It is suitable for unsupervised clustering in multimodal heterogeneous data.

Acknowledgments

References

- Budhraja, S.; Singh, B.; Doborjeh, M.; Doborjeh, Z.; Tan, S.; Lai, E.; Goh, W.; Kasabov, N. Mosaic LSM: A Liquid State Machine Approach for Multimodal Longitudinal Data Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- AbouHassan, I.; Kasabov, N.K.; Jagtap, V.; Kulkarni, P. Spiking neural networks for predictive and explainable modelling of multimodal streaming data with a case study on financial time series and online news. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18367. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Markou, I.; Pereira, F.C. Combining time-series and textual data for taxi demand prediction in event areas: A deep learning approach. Information Fusion 2019, 49, 120–129. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Q.; Kasabov, N.K. GeSeNet: A General Semantic-Guided Network With Couple Mask Ensemble for Medical Image Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 35, 16248–16261. [CrossRef]

- Doborjeh, Z.; Doborjeh, M.; Sumich, A.; Singh, B.; Merkin, A.; Budhraja, S.; Goh, W.; Lai, E.M.; Williams, M.; Tan, S.; et al. Investigation of social and cognitive predictors in non-transition ultra-high-risk’individuals for psychosis using spiking neural networks. Schizophrenia 2023, 9, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N.K. NeuCube: A spiking neural network architecture for mapping, learning and understanding of spatio-temporal brain data. Neural networks 2014, 52, 62–76. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N. Global, local and personalised modeling and pattern discovery in bioinformatics: An integrated approach. Pattern Recognition Letters 2007, 28, 673–685. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N. Data Analysis and Predictive Systems and Related Methodologies, U.S. Patent 9,002,682 B2, 7 April 2015.

- Doborjeh, M.; Doborjeh, Z.; Merkin, A.; Bahrami, H.; Sumich, A.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Medvedev, O.N.; Crook-Rumsey, M.; Morgan, C.; Kirk, I.; et al. Personalised predictive modelling with brain-inspired spiking neural networks of longitudinal MRI neuroimaging data and the case study of dementia. Neural Networks 2021, 144, 522–539. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N.K. Evolving connectionist systems, 2 ed.; Springer: London, England, 2007.

- Kasabov, N.K. Time-space, Spiking Neural Networks and Brain-inspired Artificial Intelligence; Vol. 750, Springer, 2019.

- Santomauro, D.F.e.a. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398, 1700 – 1712.

- Swaddiwudhipong, N.; Whiteside, D.J.; Hezemans, F.H.; Street, D.; Rowe, J.B.; Rittman, T. Pre-diagnostic cognitive and functional impairment in multiple sporadic neurodegenerative diseases. bioRxiv 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N.K.; FEIGIN, V.; et al. Improved method and system for predicting outcomes based on spatio/spectro-temporal data, 2015.

- Paprotny, D.; Morales-Nápoles, O.; Worm, D.T.; Ragno, E. BANSHEE–A MATLAB toolbox for non-parametric Bayesian networks. SoftwareX 2020, 12, 100588. [CrossRef]

- Koot, P.; Mendoza-Lugo, M.A.; Paprotny, D.; Morales-Nápoles, O.; Ragno, E.; Worm, D.T. PyBanshee version (1.0): A Python implementation of the MATLAB toolbox BANSHEE for Non-Parametric Bayesian Networks with updated features. SoftwareX 2023, 21, 101279. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Lugo, M.A.; Morales-Nápoles, O. Version 1.3-BANSHEE—A MATLAB toolbox for Non-Parametric Bayesian Networks. SoftwareX 2023, 23, 101479. [CrossRef]

- Calude, C.; Calude, E. A metrical method for multicriteria decision making. St. Cerc. Mat 1982, 34, 223–234.

- Calude, C. A simple non-uniform operation. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1983, 20, 40–46.

- Akhtarzada, A.; Calude, C.S.; Hosking, J. A Multi-Criteria Metric Algorithm for Recommender Systems. Fundamenta Informaticae 2011, 110, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kahramanli, H.; Allahverdi, N. Design of a hybrid system for the diabetes and heart diseases. Expert systems with applications 2008, 35, 82–89. [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, S.; Liao, Y.W.; Dugo, C.; Cave, A.; Zhou, L.; Ayar, Z.; Christiansen, J.; Scott, T.; Dawson, L.; Gavin, A.; et al. ECG-derived spatial QRS-T angle is associated with ICD implantation, mortality and heart failure admissions in patients with LV systolic dysfunction. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0171069. [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Kasabov, N. TWNFI–a transductive neuro-fuzzy inference system with weighted data normalization for personalized modeling. Neural Netw. 2006, 19, 1591–1596. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N., NeuCube EvoSpike Architecture for Spatio-temporal Modelling and Pattern Recognition of Brain Signals. In Artificial Neural Networks in Pattern Recognition; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012; p. 225–243. [CrossRef]

- Kumarasinghe, K.; Kasabov, N.; Taylor, D. Deep learning and deep knowledge representation in Spiking Neural Networks for Brain-Computer Interfaces. Neural Networks 2020, 121, 169–185. [CrossRef]

- Futschik, M.; Kasabov, N. Fuzzy clustering of gene expression data. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence. 2002 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems. FUZZ-IEEE’02. Proceedings (Cat. No.02CH37291), 2002, Vol. 1, pp. 414–419 vol.1. [CrossRef]

| Objects/Criteria | ... | ... | ||||

| ... | ... | |||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ |

| ... | ... | |||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ |

| ... | ... | |||||

| w | ... | ... |

| Objects/Criteria | ... | ... | Class label | ||||

| ... | ... | ||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ... | ... | ||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ... | ... |

| Criteria weights | ... | ... | ||||

| w | ... | ... |

| Object/Criteria | ... | ... | ||||

| x | ... | ... |

| Object/Criteria | ... | ... | Class label | ||||

| ... | ... |

| 68.2 | 0 | 6789 | small | red | 0,1,-1,-1,1,1,0,0, 1,-1 | 1,1,0 | 1 |

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 93 | 1 | 98000 | medium | yellow | 0,-1,-1,-1,-1,0,0, 1,-1,1 | 1,0,0 | 1 |

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 44.5 | 1 | 5600 | large | red | 0,1,-1,1,-1,1,0,0, 1,-1 | 1,1,0 | 1 |

| 1,0,1 | |||||||

| 1,1,1 | |||||||

| 56.8 | 0 | 89 | small | white | 1,-1,-1,-1,-1,1,0,0, 1,-1 | 1,1,0 | 1 |

| 0,1,1 | |||||||

| 1,0,1 | |||||||

| 26.3 | 0 | 9456 | large | black | 1,-1,-1,-1,0,1,0,0, 1,-1 | 1,1,0 | 2 |

| 1,1,1 | |||||||

| 1,0,1 | |||||||

| 81.5 | 1 | 78955 | medium | red | 0, 1,-1,1,-1,-1,0,0, 1,-1 | 1,1,0 | 2 |

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 1,1,1 | |||||||

| 56.7 | 1 | 68900 | small | black | 1,- 1,-1,1,-1,1,0,0, 1,1 | 1,1,1 | 2 |

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 1,1,1 | |||||||

| 20 | 0 | 7833 | large | yellow | 1,1,-1,-1,1,1,0,-1, -1,1 | 1,0,0 | 2 |

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 1,1,1 | |||||||

| 20 | 0 | 7833 | ∞ | yellow | 1,1,-1,-1,1,1,0,-1, -1,1 | 1,0,0 | 2 |

| 0,0,1 | |||||||

| 1,1,1 |

| 48.5 | 1 | 45679 | large | red | 1, 0, 0, -1, 1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 1 | 1,1,0 |

| 0,0,1 | ||||||

| 1,0,1 |

| 68.2 | 0 | 6789 | 0 | FF0000 | 0122110012 | 110001001 | 1 | |

| 111111110000000000000000 | ||||||||

| 93 | 0 | 98000 | 1 | FFFF00 | 0222200121 | 110001001 | 1 | |

| 111111111111111100000000 | ||||||||

| 44.5 | 1 | 5600 | 2 | FF0000 | 0121210012 | 110101111 | 1 | |

| 111111110000000000000000 | ||||||||

| 56.8 | 0 | 89 | 0 | FFFFFF | 1222210012 | 110011101 | 1 | |

| 111111111111111111111111 | ||||||||

| 26.3 | 0 | 9456 | 2 | 000000 | 1222010012 | 110111101 | 2 | |

| 000000000000000000000000 | ||||||||

| 81.5 | 1 | 78955 | 1 | FF0000 | 0121220012 | 110001111 | 2 | |

| 111111110000000000000000 | ||||||||

| 56.7 | 1 | 68900 | 0 | 000000 | 1221210011 | 111001111 | 2 | |

| 000000000000000000000000 | ||||||||

| 20 | 0 | 7833 | 2 | FFFF00 | 1122110221 | 100001111 | 2 | |

| 111111111111111100000000 | ||||||||

| 20 | 0 | 7833 | ∞ | FFFF00 | 1122110221 | 100001111 | 2 | |

| 111111111111111100000000 |

| x | 48.5 | 1 | 45679 | 2 | FF0000 | 1002121001 | 110001101 |

| 111111110000000000000000 |

| 0.682 | 0 | 0.06789 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.0122110012 | 0.110001001 | |

| 0.93 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.0222200121 | 0.100001001 | |

| 0.445 | 1 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.0121210012 | 0.110101111 | |

| 0.568 | 0 | 0.00089 | 0 | 1 | 0.1222210012 | 0.110011101 | |

| 0.263 | 0 | 0.09456 | 1 | 0 | 0.1222010012 | 0.110111101 | |

| 0.815 | 1 | 0.78955 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0121220012 | 0.110001111 | |

| 0.567 | 1 | 0.689 | 0 | 0 | 0.1221210011 | 0.111001111 | |

| 0.2 | 0 | 0.07833 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.1122110221 | 0.100001111 | |

| 0.2 | 0 | 0.07833 | ∞ | 0.6 | 0.1122110221 | 0.100001111 |

| x | 0.485 | 1 | 0.45679 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.1002121001 | 0.110001101 |

| 0.197 | 1 | 0.3889 | 1 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.11111111 | 3.09701111 | |

| 0.445 | 0 | 0.52321 | 0.5 | 0.33333333 | 0.6 | 0.22222222 | 2.62376556 | |

| 0.04 | 0 | 0.40079 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.22222222 | 1.16301222 | |

| 0.083 | 1 | 0.4559 | 1 | 0.66666667 | 0.45 | 0.11111111 | 3.76667778 | |

| 0.222 | 1 | 0.36223 | 0 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 2.58978556 | |

| 0.33 | 0 | 0.33276 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.45 | 0.11111111 | 1.72387111 | |

| 0.082 | 0 | 0.23221 | 1 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 2.31976556 | |

| 0.285 | 1 | 0.37846 | 0 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 2.66901556 | |

| 0.285 | 1 | 0.37846 | 1 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 3.66901556 |

| 0.04 | 0 | 0.40079 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.22222222 | 1.16301222 | |

| 0.33 | 0 | 0.33276 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.45 | 0.11111111 | 1.72387111 | |

| 0.082 | 0 | 0.23221 | 1 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 2.31976556 | |

| 0.222 | 1 | 0.36223 | 0 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 2.58978556 | |

| 0.445 | 0 | 0.52321 | 0.5 | 0.33333333 | 0.6 | 0.22222222 | 2.62376556 | |

| 0.285 | 1 | 0.37846 | 0 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 2.66901556 | |

| 0.197 | 1 | 0.3889 | 1 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.11111111 | 3.09701111 | |

| 0.285 | 1 | 0.37846 | 1 | 0.33333333 | 0.45 | 0.22222222 | 3.66901556 | |

| 0.083 | 1 | 0.4559 | 1 | 0.66666667 | 0.45 | 0.11111111 | 3.76667778 |

| 0.2 | 0 | 0.00089 | 0 | 1 | 0.1222210012 | 0.100001001 |

| 1.469 | 0.987 | 1.469 | 1.402 | 1.469 | 0.669 | 1.359 | 1.459 |

| 3.709 | 2.979 | 2.709 | 2.730 | 3.209 | 3.309 | 3.609 | 3.709 |

| 3.220 | 2.975 | 2.220 | 3.165 | 2.220 | 2.420 | 3.110 | 3.210 |

| 0.378 | 0.010 | 0.378 | 0.378 | 0.378 | 0.378 | 0.378 | 0.368 |

| 2.167 | 2.104 | 2.167 | 2.073 | 1.167 | 1.167 | 2.167 | 2.157 |

| 3.824 | 3.209 | 2.824 | 3.035 | 3.324 | 3.024 | 3.714 | 3.814 |

| 3.066 | 2.699 | 2.066 | 2.378 | 3.066 | 2.066 | 3.066 | 3.055 |

| 1.487 | 1.487 | 1.487 | 1.410 | 0.487 | 1.087 | 1.477 | 1.487 |

| 1.487 | 1.487 | 1.487 | 1.410 | 0.487 | 1.087 | 1.477 | 1.487 |

| Distances | 2.870 | 4.00 | 2.826 | 5.00 | 5.60 | 0.450 | 0.061 |

| Weights | 0.137 | 0.192 | 0.135 | 0.240 | 0.269 | 0.021 | 0.002 |

| Patients/Criteria | ... | ... | Units of time | ||||

| ... | ... | ||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ... | ... | ||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ... | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ... | ... |

| Patient/Criteria | ... | ... | ||||

| p | ... | ... |

| patients | units of time | |||||||

| 0.682 | 0 | 0.06789 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.012211001 | 0.110001001 | 12.3 | |

| 0.93 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.022220012 | 0.100001001 | 15 | |

| 0.445 | 1 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.012121001 | 0.110101111 | 68 | |

| 0.568 | 0 | 0.00089 | 0 | 1 | 0.122221001 | 0.110011101 | 1.4 | |

| 0.263 | 0 | 0.09456 | 1 | 0 | 0.122201001 | 0.110111101 | 40.5 | |

| 0.815 | 1 | 0.78955 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.012122001 | 0.110001111 | 97.2 | |

| 0.567 | 1 | 0.689 | 0 | 0 | 0.122121001 | 0.111001111 | 97.2 | |

| 0.2 | 0 | 0.07833 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.112211022 | 0.100001111 | 55.7 | |

| 0.2 | 0 | 0.07833 | ∞ | 0.6 | 0.112211022 | 0.100001111 | 63.7 |

| 0.485 | 1 | 0.45679 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.1002121001 | 0.110001101 |

| Distance d | ||||||||

| 0.1970 | 1 | 0.388900 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.08800109890 | 0.000000100 | 2.67390119890 | |

| 0.4450 | 0 | 0.523210 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.07799208800 | 0.010000100 | 1.95620218800 | |

| 0.0400 | 0 | 0.400790 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.08809109890 | 0.000100010 | 0.52898110890 | |

| 0.0830 | 1 | 0.455900 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.02200890110 | 0.000010000 | 3.36091890110 | |

| 0.2220 | 1 | 0.362230 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.02198890110 | 0.000110000 | 1.80632890110 | |

| 0.3300 | 0 | 0.332760 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.08809009890 | 0.000000010 | 1.25085010890 | |

| 0.0820 | 0 | 0.232210 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.02190890100 | 0.001000010 | 1.53711891100 | |

| 0.2850 | 1 | 0.378460 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.01199892200 | 0.009999990 | 2.08545891200 | |

| 0.2850 | 1 | 0.378460 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.01199892200 | 0.009999990 | 3.08545891200 |

| Name | Data type | Definition |

| age | integer | age in years |

| sex | binary | sex |

| cp | {1,2,3,4} | chest pain type |

| trestbps | integer | resting blood pressure |

| chol | integer | serum cholesterol in mg/dl |

| fbs | binary | fasting blood sugar > 120 mg/d |

| restecg | {0,1,2} | resting electrocardiographic results |

| thalach | I integer | maximum heart rate achieved |

| exang | binary | exercise-induced angina |

| oldpeak | float | ST depression induced by exercise relative to rest |

| slope | {1,2,3} | the slope of the peak exercise ST segment |

| ca | {0,1,2,3,} | number of major vessels colored by flourosopy |

| thal | {3,6,7} | heart status |

| num | {0,1,2,3,4} | diagnosis of heart disease |

| Record | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | Channel 3 | Label |

| R1 | (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) | (0, 1, 1, 1, -1) | (1, 1, -1, -1, 0) | 1 |

| R2 | (1, 0, -1, 0, 1) | ( 0, 1, 1, 1, -1) | (1, 0, -1, -1, 1 ) | 1 |

| R3 | (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) | (0, -1, 1, 1, -1) | (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) | 2 |

| R4 | (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) | (0, -1, 1, 0, -1) | (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) | 2 |

| R5 | (1, 1, -1, 0, 0) | (0, -1, 0, 1, -1) | (1, 1, -1, 1, 1) | 3 |

| R6 | (1, -1, -1, 0, 1) | (0, -1, 1, 0, -1) | (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).