1. Introduction

Since its appearance in late 2019, COVID-19 has been investigated as a respiratory disease, with extreme care paid to severe pulmonary symptoms and virus spreading kinetics. However, recent clinical evidence has demonstrated that the pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)has effects far beyond the lung and employs pathogenesis mechanisms related to endothelial dysfunction, microvascular injury and immune dysregulation [

1,

2,

3]. Long COVID Depending on the source, long COVID is now an established persistent post-infection multisystem syndrome that has left millions of people with compromised health status even months after clearing the virus [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

An increasingly large body of research has outlined PASC-related complications in the cardiovascular, neurological, renal, hepatic and gastrointestinal systems [

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, the literature is still scattered; the majority of reviews are devoted to central organs or separate symptoms, leaving a gap in the representation of the systemic effects of COVID-19 [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Moreover, the published literature does not often pursue in-depth comparative studies of the similarities in the pathophysiological processes triggering such organ-specific effects. The possible mechanisms of cytokine storm, interactions of ACE2-receptors, thromboinflammation. In addition, a continuous immune response is emerging as an epic theme but the various implications of these phenomena in different organs and how they may be addressed by SARS-CoV-2 mutation have not been fully discussed [

18,

19].

The purpose of the current review is to fill these gaps by providing a systematic synthesis of the evidence regarding the multimodal effects of COVID-19 which combines available clinical trials, autopsy reports, cohort-based findings and systematic reviews published between 2020 and 2025. Unlike other studies, this study shows 10 major organ systems against each other and charts their specific weaknesses and shares common molecular and cellular pathways. This review permits a cross-system approach and clinical combination of the conclusions in various fields of medicine to argue in favor of a paradigm shift in treatment from organ-specific interventions to systemic, longitudinal management, addressing an urgent need in the current post-pandemic literature.

2. Methodology

2.1. Protocol and Search Strategy

This systematic narrative review was conducted based on the guidelines of narrative synthesis. We retrieved the databases of PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science and searched them between January 1, 2020 and May 31, 2025.

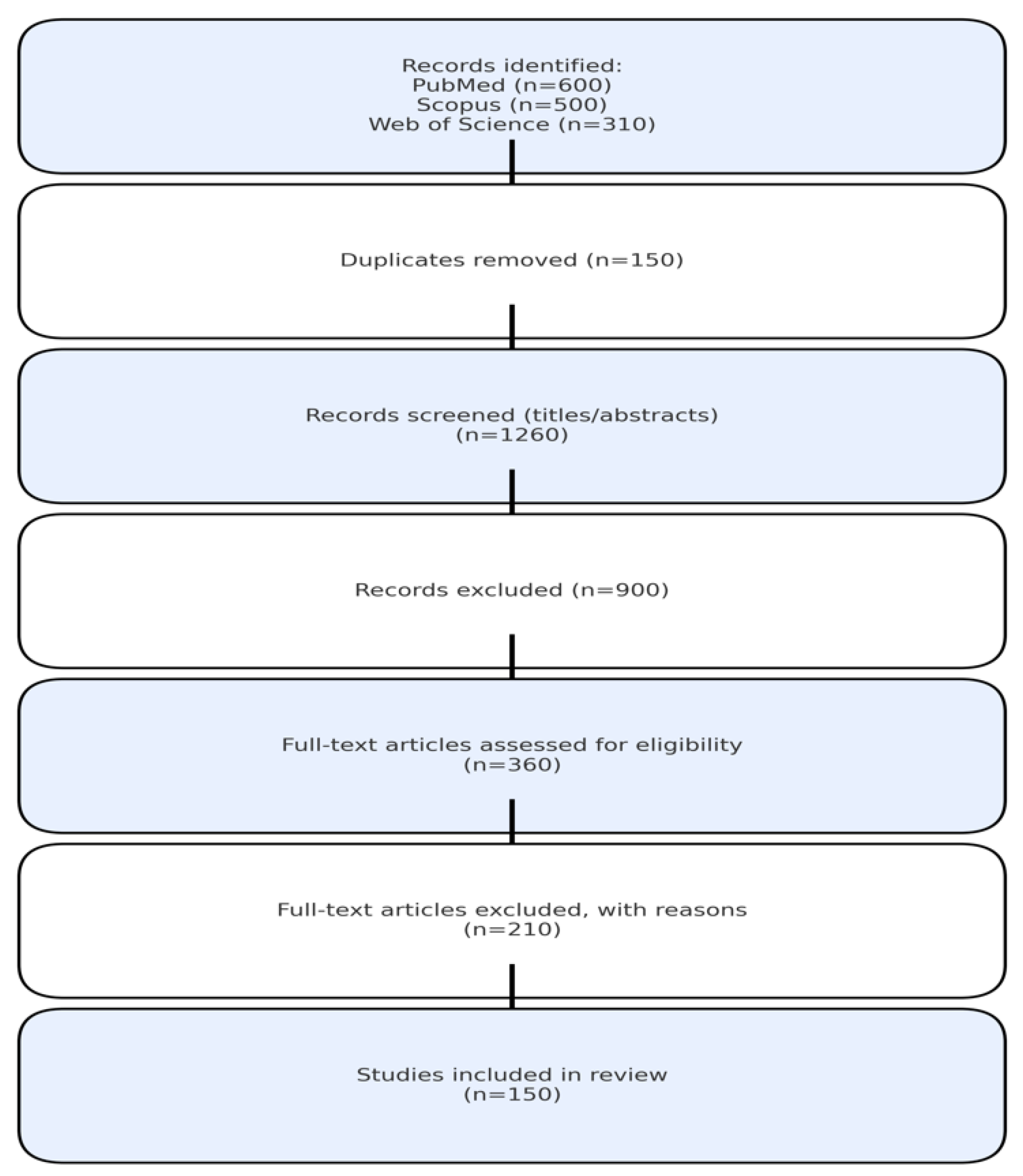

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing the number of studies identified, screened, excluded and included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing the number of studies identified, screened, excluded and included in the review.

The search strategy was based on the following combinations of Boolean:

Search String:

((COVID-19[MeSH] OR SARS-CoV-2[MeSH] OR “coronavirus disease 2019”)

AND

(“multi-organ” OR “organ dysfunction” OR “systemic complications” OR

(pulmonary OR cardiovascular OR neurological OR renal OR hepatic OR

gastrointestinal OR endocrine OR reproductive OR dermatological OR hematological)))

Date of last search: May 31, 2025

2.2. Study Selection

Inclusion criteria:

Peer-reviewed publications in English

Human studies with clinical outcome data

Studies reporting organ-specific complications of COVID-19

Clinical studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Minimum sample size of 10 patients for primary studies

2.3. Study Selection

Inclusion criteria:

Peer-reviewed publications in English

Human studies with clinical outcome data

Studies reporting organ-specific complications of COVID-19

Clinical studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Minimum sample size of 10 patients for primary studies

2.4. Screening Process

Two independent reviewers conducted the following:

Title and abstract screening (n=1,410 records identified)

Full-text review of potentially eligible studies (n=236)

Final inclusion of 147 studies meeting all criteria

Disagreements resolved through consensus discussion

The number of records identified, screened, reviewed in full text and finally included in the review is summarized in Table 1.

A summary of the search strategy and selection process is presented in Table 1.

| Database |

Records Identified |

After Duplicates Removed |

Full Text Reviewed |

Included |

| PubMed |

567 |

498 |

98 |

62 |

| Scopus |

492 |

441 |

89 |

48 |

| Web of Science |

351 |

308 |

49 |

37 |

| Total |

1,410 |

1,247 |

236 |

147 |

| Source: Current review search process, adapted from PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science database queries (January 1, 2020 – May 31, 2025). |

2.5. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Standardized forms were used to extract data which consisted of the nature of the study, demographics of the population, organ-specific outcomes and follow-up period. Quality was determined using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies.

The distribution of studies by risk of bias, stratified by study type, is summarized in

Table 3.

3. Pulmonary System Complications in COVID-19

The main focus of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity is the pulmonary system which applies the initial track of severity that ends up in acute respiratory distress or long-term sequelae. The first symptoms tend to appear in the form of viral pneumonia, accompanied by alveolar infiltration, inflammatory exudate and ineffective exchange of gases. Dyspnea, affecting 53–76% of hospitalized patients, along with fever, chest pain and prolonged cough, are the clinical manifestations, whereas bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT, present in 78% of cases (95% CI: 72–84%) and considered a characteristic pattern of COVID-19 pneumonia, can be observed using radiographic imaging [

28,

29,

30]. In susceptible patients, viral pneumonia may develop as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), where the severity of hypoxemia increases due to cytokine-mediated damage to the alveoli and dissemination of fluid in the pulmonary capillaries. It is important to note that numerous patients develop so-called silent hypoxemia which is a dangerous condition when blood oxygen saturation levels drop and do not correlate with respiratory distress, thus delaying emergency care [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Silent hypoxemia has been reported in approximately 18–20% of cases.

Pervasive hypoxemia in severe COVID-19 not only indicates poor clinical outcomes but also contributes to the development of systemic dysfunction. Breaking of the alveolar-capillary integrity and fluid loading limits oxygen diffusion, leading to fatigue and multiorgan impairment. Based on this, pulse oximetry has become a very important monitoring tool in hospitals and at home to monitor silent deterioration [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Pulmonary fibrosis has been a major issue after the acute phase. In survivors, especially in cases where mechanical ventilation is involved, fibrotic remodeling replaces functional alveoli with non-compliant scar tissue. The resulting exertional dyspnea, reduced exercise tolerance and, in selected cases, irreversible loss of lung capacity prompts the need for new antifibrotic therapies, with pulmonary fibrosis developing in approximately 15% of patients at six months post-infection. Nonetheless, it has been estimated that recent information shows utilization is only partly effective and conclusive use is under examination [

31,

32,

33].

Organizing pneumonia is also associated with persistent hypoxemia, a subacute complication caused by excessive repair mechanisms that cause scarring in the airways which manifests clinically as fatigue, fever and imaging abnormalities. The existence of disparate responses to corticosteroids and the risk of relapse highlight the urgent need for personalized treatment pathways [

34].

Moreover, chronic bronchial inflammation is the cause of prolonged cough and hyperreactivity in the airways of patients with mild or moderate disease. A chronic immunological response in such patients can also be a precursor to post-infectious asthma, particularly in patients with atopy [

35].

Another element of increasing complexity is the involvement of vascular disease. Hypercoagulable states in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection increase the risk of pulmonary embolism which is characterized by endothelial damage and coagulation imbalance. Polypnea, pleuritic chest pain and tachycardia can camouflage other pulmonary diagnoses and timely imaging and risk-stratified anticoagulation are essential. However, the question of whether prophylactic anticoagulation implies more significant benefits than hemorrhagic danger is still debatable, especially in patients with preconditions [

36,

37,

38].

Furthermore, long COVID still throws light on an alarming set of post-disease respiratory symptoms that dogs those whose acute illness was not noteworthy. Chest tightness, dyspnea and exercise intolerance can persist for many months and can be seen without the presence of radiologic abnormalities. This seems to be achievable through the synergistic association of airway inflammation, autonomic imbalance and microvascular injury. To make things more complex, the latter have also observed a decreasing diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), an objective measure of alveolar-capillary dysfunction which was reported at all levels of severity, thus indicating ongoing subclinical damage even in non-critical patients [

39,

40].

The epicenter of most pulmonary insults is a cytokine storm which not only becomes a driver of ARDS but also enhances vascular leakage, infiltration of immune cells and fibrotic remodeling. Although the use of corticosteroids and other immunomodulators has resulted in positive results in the critical care sector, the exact timing and dosage remain debatable because of the risk of secondary infection and possible disruption of viral clearance [

24]. These therapeutic doubts are indicators of the larger problem of how to deal with a condition that does not fall within the ordinary descriptive paradigms of viral pneumonia.

In conclusion, the respiratory manifestations of COVID-19 fall along a strict continuum, ranging from acute lung injury to chronic dysfunction and can defy even established diagnostic criteria and treatment algorithms. The pulmonary legacy of the virus extends beyond the initial infection and requires prolonged respiratory rehabilitation, individual pharmacotherapy and combined aftercare procedures. Owing to the development of new variants and the ongoing development of post-viral syndromes, pulmonary care will need to transition towards the provision of long-lasting respiratory resilience and healing rather than transitional acute care.

4. Cardiovascular System Complications in COVID-19

However, in examining the cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19, the practitioner soon faces a wide range of acute and chronic dysfunctions caused by the interaction of viral invasion, systemic inflammation and idiosyncratic susceptibility. Myocardial injury is one of the first and most frequently observed findings, with increased troponin levels reported in 28% of hospitalized patients (95% confidence interval [CI]: 24–32%). There is a combination of pathogenesis underlying processes, direct intracellular invasion through ACE2 receptors, ischemia induced by hypoxia and a pathologic cascade of inflammatory molecules that reduce cardiac function and sometimes obscure a classic acute coronary syndrome presentation [

41,

42,

43]. Although myocarditis could be underdiagnosed during the acute stage due to the scarcity of cardiac MRI or biopsy, cardiac MRI–confirmed myocarditis has been identified in 7.2% of suspected cases. This is the basis of substantial myocardial inflammation, arrhythmogenesis and in both adult and child populations, an increased risk of sudden cardiac death [

28,

44,

45].

Dysrhythmic complications are also extensive, with new arrhythmias reported in 16% of hospitalized patients, including tachyarrhythmias, atrial fibrillation and transient bradycardia. These arrhythmias emerge not only in people with cardiac malady but also in those who are unaffected, implying that SARS-CoV-2 can produce a direct electrical imbalance by centralized inflammation, nutrient imbalances and myocardial tension. Furthermore, a significant number of such arrhythmias survive right into the convalescent period which justifies the need for ambulatory rhythm monitoring in high-risk groups. At the same time, the prothrombotic environment created by COVID-19 has resulted in an increased number of acute coronary syndromes, whereas thromboinflammatory mechanisms, including destabilization of coronary artery plaques and hyperactivation of platelets, trigger both arterial and venous events, with venous thromboembolism occurring in 11% of patients (95% CI: 9–13%). Early intervention is always necessary but it is inhibited by the presence of infection control and limited access to cardiac imaging studies [

24,

46,

47,

48].

Heart failure, both as a direct viral impact and decompensation of already existing underlying disease, demonstrates the cumulative effects of hypoxic stress, cytokine-mediated inflammatory processes and reduced myocardial contractility. De novo or secondary to pre-existing cardiac dysfunction, COVID-19-related heart failure is inevitably associated with a higher number of ICU admissions and all-cause mortality [

20,

49,

50]. Further activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) by the virus also increases the activity of angiotensin II, increasing hypertension and further enhancing vascular dysfunction which leads to the development of the acute and post-acute phases of the disease [

24,

51,

52,

53]. These findings emphasize the need for active antihypertensive management and adequate hemodynamic monitoring during the recovery process.

Academically, the cardiovascular consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection are dynamic and multifaceted. Severe myocardial damage which manifests in a proportion of hospitalized patients, is often aggravated by systemic vascular disruption, also known as endothelial dysfunction which predisposes patients to thrombogenesis, vasoconstriction and tissue hypoperfusion. The diffuse nature of this endothelial insult explains why the cardiovascular symptoms associated with COVID-19 are not limited to the heart and the idea of COVID-19 being a vascular disease has been reiterated [

20,

54]. Stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo syndrome), although less frequent, has also been on the rise and is presumably supported by acute mental and physiological stress, excessive sympathetic action and excess catecholamines [

35,

55,

56].

The chronic cardiovascular sequelae of long COVID are equally difficult to understand. The side effects that are ongoing in a significant number of patients include chest pain, poor physical activity tolerance and intermittent palpitations, even in patients with mild or asymptomatic infections. The possible mechanisms specified are a disturbance of the balance of the autonomic nervous system, incomplete low-grade myocarditis, microvascular disorders and persistent inflammation which further increase patient distress and complicate the diagnosis [

28,

57,

58]. Consequently, long-term symptoms cannot be easily categorized, thus requiring long-term follow-up in personalized, symptom-sensitive management systems.

In summary, the cardiovascular consequences of SARS-CoV- 2 infection are complex and dynamic. Including cardiovascular complications such as myocardial injury and neurological events such as intracranial hemorrhage, along with acute injury, latent dysfunction and systemic vascular disruption, has complicated the need to implement a multidisciplinary approach that is both clinical and research-based. A complete understanding of the cardiac footprint of COVID-19 must ground the correct therapy that can not only alleviate acute developments but also predict and prevent chronic sequelae among survivors.

5. Multisystem Cardiovascular, Neurological and Renal Impacts of COVID-19

The pathophysiology of COVID-19 goes beyond the pulmonary system, with tremendous and frequently sustained slices in the cardiovascular, neurological and renal systems. Cardiovascular complications have taken a leading role in the systemic severity of the disease; myocardial damage, measured by elevated troponin levels, is reported in 28% of hospitalized patients (95% CI: 24–32%). The cause of this damage is usually a combination of direct viral infectivity, cytokine-induced inflammation and lack of oxygen. This effect is associated with a higher occurrence of arrhythmias, acute heart failure and poorly defined acute coronary syndromes, often in non-cardiovascular patients. This burden is compounded by myocarditis which is often underdiagnosed and potentially deadly and may be characterized by a wide range of symptoms, from mild discomfort to cardiac death. The arrhythmia spectrum is wide, with benign and fatal effects that occur regardless of structural heart disease.

The long-identified hypercoagulable state of severe COVID-19 has increased the rates of thromboembolic events, including acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis, a cascade that highlights the difficulty in managing the possibilities of anticoagulation and bleeding. Dysregulation of blood pressure control, especially newly discovered or aggravated hypertension, is believed to be mediated through the involvement of ACE2 and Angiotensin II cascades which is an additional problem in the cardiovascular profile [

59,

60,

61]. The persistence of chest pain and palpitations in patients with long COVID also evinces the post-acute cardiac consequences of the disease, much of which is not well understood and requires long-term cardiovascular rehabilitation [

62].

The neurological system presents a high variability of susceptibility to COVID-19, with a very mild array of impairments in cognitive function to an extreme neuroinflammatory syndrome. Delirium, occurring in approximately 23% of ICU patients, is the cumulative effect of systemic hypoxia, proinflammatory cytokines and metabolic disturbances. As a primary manifestation of long COVID, the concept of cognitive slowing (or brain fog) has begun to be widely accepted and can potentially be attributed to the infiltration of the blood-brain barrier, microvascular impairment and ongoing pathogenic neuroimmune imbalance [

63,

64,

65,

66]. Ischemic strokes occur in approximately 2.5% of all COVID-19 patients, rising to 5.1% in those with severe disease and are observed more frequently among younger patients, possibly because of endothelial dysfunction–induced coagulopathy caused by the virus. Major sensory losses, such as anosmia and ageusia, reported in 43% of patients (95% CI: 38–48%), are a sign of the neurotropic potential of SARS-CoV-2, a phenomenon that is not normally found in the absence of nasal congestion [

67].

There are a number of important neurological sequelae of COVID-19 infection, the first and most obvious of which include encephalitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) and a range of peripheral neuropathies. The aforementioned conditions develop in a two-fold manner: via straightforward viral infiltration of the nerve cells and via induction of autoimmune responses manifested by molecular mimicry of the virus against some self-proteins specializing in the nerve cells. Such complications, in most instances, lead to chronic disability and the need to implement multidisciplinary management interventions and early clinical identification has been highlighted [

68,

69].

At the same time, neuropsychiatric morbidity has especially grown among the infected and the general population. Epidemiological evidence has revealed considerable increases in anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder which are strongly linked to the psychological effects of the pandemic [

70,

71,

72]. Decades later, months after the first viral clearance, abnormalities in mental abilities, such as cognitive impairment, which persists in approximately 18% of patients at six months, have been found to be a main feature of long COVID, making the idea that mental status requires compliance with neurological services even more accurate.

Renal involvement is similar and equally thorough line of damage. AKI is common, occurring in 28% of intensive care unit patients and 12% of those in general wards and is the result of a mosaic of pathological drivers, including direct viral cytopathy, immune-regulated inflammation, perfusion and systemic hypoxia [

24,

73,

74]. Post-mortem and biopsy analyses have shown the presence of viral antigens in the cell lining of the tubules, indicating infection through ACE 2 receptors [

28,

75]. Proteinuria, present in 42% of patients and hematuria, observed in 31%, are predictive markers that precede overt AKI, are associated with an increase in mortality and represent early glomerular or tubular stress due to inflammatory processes [

76]. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy also appears, further increasing ischemic injury [

77,

78,

79].

The loss of fluid due to fever, diarrhea or insufficient hydration worsens acute renal ischemia, especially in individuals (older adults or those with existing chronic kidney disease [CKD] ) [

28,

80]. Even with underlying kidney failure, patients have been shown to have a faster course of progression to diagnosed end-stage renal disease, with hemodynamic instability, secondary infection and cardiovascular degradation as the driving factors [

81]. The appearance of renal fibrosis that parallels that found in pulmonary fibrosis has also been reported in long-term COVID populations and is now a logical target for early anti-fibrotic treatment [

82]. Notably, dialysis is required in approximately 9% of AKI cases and patients with end-stage kidney disease or those already on dialysis have a high mortality risk, underscoring the need for personalized reno-protective practice with strict infection-control measures [

83].

Collectively, the multi-systemic interaction of cardiovascular, neurological and renal manifestations of COVID-19 portrays a multifactorial disease that interferes with homeostasis in key organ systems. Such sequelae are not solved during the acute stage; however, they are now the backbone of long COVID manifestations and can be a severe health risk, with incomplete recovery reported in approximately 35% of patients at six months post-infection. Cardiology, neurology, nephrology and rehabilitation are needed to integrate with the integrative model to meet the scope of the organ impacts SARS-CoV-2 can have and establish the path toward extensive recovery.

6. Hepatic Complications of COVID-19: Pathogenesis and Prognostic Concerns

Since the beginning of the pandemic, it has become evident that the liver is a primary site of SARS-CoV-2-related pathology which has evolved simultaneously with the greater awareness of the pulmonary tropism of the virus. The role of the liver during COVID-19 ranges from transient aminotransferase elevation to fulminant liver failure and is a dynamic process that represents the interplay between viral replication and innate immunological responses as well as acquired responses and systemic derangements. Mild-to-moderate (previously mainly ALT and AST) increases occur regularly and are especially frequent in severely affected patients, accompanied by unfavorable clinical outcomes. Therefore, these laboratory data are currently considered useful prognostic tools for sorting hospitalized patients [

84,

85,

86].

Its effect is especially severe when there are pre-existing liver abnormalities, such as chronic viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or cirrhosis in the relevant individuals. SARS-CoV-2 in these cohorts not only acts as a secondary stressor but also as a precipitating factor for hepatic decompensation, jaundice, encephalopathy and acute-on-chronic liver failure. Other patients known to be vulnerable to deterioration are those with cirrhosis, who are usually immunosuppressed and have only a small hepatic reserve. In addition, NAFLD basal metabolic dysfunction and a proinflammatory environment seem to worsen liver damage and increase the risk of hospitalization, faster development of fibrosis and hinder regulatory immune responses [

87,

88,

89,

90].

The etiopathology of COVID-related liver damage is multifactorial. The binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 receptors leads to hepatocyte and cholangiocyte apoptosis, necrosis and histological data on hepatocellular damage. Postmortem examinations have also established the presence of viral RNA in liver tissues, indicating that liver involvement might also be present even in asymptomatic cases where the patient shows no symptoms. Moreover, with respiratory failure and hypoxia affecting the system, there is a possibility of developing hypoxic hepatitis, where enzymes rise significantly and there is a poor outcome especially among critically ill patients [

35,

91].

An additional complication is exerted by DILI, particularly in patients whose medication includes a combination of antivirals, antibiotics, corticosteroids and antipyretics. Combined with extensive monitoring and ample differential diagnosis, it is essential to differentiate DILI from direct viral injury or ischemic hepatitis, especially in intensive care units [

92]. Immune-mediated mechanisms in the pathogenesis of hepatic injury include hyperinflammatory states (such as cytokine storms) and microvascular coagulopathy. The extent of systemic inflammation is often reflected in elevated enzyme levels; therefore, at critical levels, immunomodulatory measures are required [

93,

94].

Another commonly under-recognized clinical presentation of COVID-19 is cholestasis in severely ill patients which is characterized by pruritus, jaundice and elevated bilirubin levels. Direct viral infection of cholangioocytes is possibly one of the processes that raises some plausibility; however, more frequently, immune dysregulation and hepatotoxic drug effects play contributory roles. Cholestasis, in turn, in addition to slowing the course of the disease and delaying its release, creates inconveniences in the hospital setting and increases the likelihood of developing secondary infections. It is also associated with vascular complications, including portal vein thrombosis (PVT). PVT is uncommon but can be disastrous as it interferes with blood circulation in the liver, leading to portal hypertension, ascites and intestinal ischemia. Since these symptoms are also common complications of COVID-19 in the abdomen, such diagnoses are easily overlooked and rapid anticoagulation is a crucial intervention for reducing downstream pathology [

95,

96,

97].

Not less alarming is the fact that hepatic dysfunction continues for many months after acute infection. Some post-COVID-19 patients, especially those who already had liver disease, when they have chronic enzyme increase, steatosis, fibrosis or persistent inflammation, they are a subset of post-COVID-19 patients. The presence of such sequelae leads to the idea that SARS-CoV-2 can trigger the development of chronic liver disease or death of liver tissue in the long term [

98,

99]. These implications for hepatology are substantial, whether they are consequences of unresolved chronic inflammation, prolonged immune dysregulation or primary viral persistence itself.

In summary, liver injury in COVID-19 is not coincidental and harmless; it indicates a wider systemic disruption of physiology, immune control and vascular homeostasis by the virus. Targeted hepatic monitoring should thus be included in the clinical management of COVID-19, specifically in people at risk. Further, routine follow-up treatment norms should be instituted after discharging COVID-19 patients to identify and manage the changing hepatic pathology. The dilemma in the administration of treatment should consider the two-fold effects of viral cytopathy and pharmacological hepatotoxicity, with the health of the liver forming the epicenter of the overall management of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

7. Gastrointestinal Manifestations and Post-Acute Complications of COVID-19

Since it was initially a respiratory pathogen, SARS-CoV-2 has demonstrated a high tropism for the gastrointestinal (GI) tract which has led to destabilization of epithelial integrity and increased systemic disease processes. A significant empirical finding proves that diarrhea, a common symptom and sometimes the initial symptom, may precede respiratory manifestations and is linked to viral replication through the ACE2 receptor which is highly expressed in intestinal enterocyte lineages. This demonstration of GI manifestation during an early form of the disease also complicates the clarity of the diagnosis, especially in cases involving asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic respiratory presentations, as well as raising concerns about possible fecal-oral transmission due to the protracted nature of viral RNA levels in the stool [

28,

100,

101,

102].

The multiplicity of the pathogenic effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the gut is captured by a wider ring of upper GI signs and symptoms, comprising nausea and vomiting. These manifestations are usually regressive but they can upset weak or elderly patients, leading to dehydration and malnutrition [

103,

104,

105]. Abdominal pain which was less frequently recorded, deserves specific mention as it may be an indication of dangerous phenomena such as mesenteric infarction or ischemia, a thrombotic event that is a complication of COVID-induced coagulopathy. The risk of bowel necrosis and septic complications increases when abdominal pain is attributed too late and even more so in cases without overt respiratory distress [

106,

107,

108].

Another common and overestimated symptom is anorexia which is attributed to inflammation in the body, gut-brain axis disruption and disrupted metabolic signaling. This effect on hospitalized or elderly patients on their appetite suppresses the capacity to gain muscle mass and delays functional recovery [

109,

110]. Gastrointestinal bleeding which is very rare, presents a two-fold risk in patients with COVID-19. All of these are associated with the occurrence of mucosal damage, pharmacologic stress ulcers and the administration of anticoagulation therapy thus promoting the occurrence of bloodshed especially in ICU patients. Unnecessary and untimely bleeding is also a critical issue in the field of anticoagulation, where the process of stopping thrombosis and causing hemorrhage is impossible [

111,

112].

Recent interest has focused on the liver-gut axis as a conduit through which intestinal inflammation transfers long-term systemic consequences. Other mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 hepatotoxicity and systemic inflammation include SARS-CoV-2-based dysbiosis, mucosal barrier disruption and release of microbial metabolites, strengthening the position to regard COVID-19 as a multi-organ syndrome with the gastrointestinal tract serving both as an organ to be attacked and an agent to cause the development of influencing factors [

113,

114]. The presence of mesenteric ischemia which develops although not frequently, is a precursor of poor prognosis among patients with critical illness and immediately causes a high mortality rate in the absence of early diagnosis and intervention through several surgeries [

106].

It is important to note that the long-lasting impacts of SARS-CoV-2 are beyond the sphere of the lungs. An increasing number of studies have confirmed that the virus produces immense changes in the microbiome of the gastrointestinal tract, a process that can be described as dysbiosis. In a typical fashion, commensal strains become attenuated and organisms that live on the edge of disease, known as pathobionts, bloom. This microbial rearrangement could take longer to recuperate, heighten body-wide inflammation and even decrease vaccination reactivity [

115]. The use of probiotics in investigative studies or specific dietary interventions that are already taking place in clinical settings represents a new prospect in which post-viral treatment is ripe but not quite ready.

Gastrointestinal sequelae are a dominant element of the phenomenon. The resolution of respiratory symptoms may be accompanied by the continued presence of viral RNA in the feces of some patients, indicating the presence of intestinal reservoirs and an increased possibility of long-term infectivity in susceptible individuals [

28]. At the same time, there is an increasing rate of functional disturbances after the virus, often of the nature of irritable bowel syndrome. Their pathogenesis consists of persistent low-grade inflammation, immune-mediated neuromodulatory impulses and chronic microbial imbalances.

All of these, in combination, testify to the fact that gastrointestinal involvement in COVID-19 is not an extraneous or peripheral aspect of pathology but part of a systemic disorder. Their consequences extend between symptom control, aggravation of systemic inflammation and hindrance of complete recovery. In turn, this makes it necessary to incorporate early identification of signs of GI dysbiosis, the future of evidence-based, microbiome-centered healthcare and targeted, multidimensional nutrition into the COVID-19 toolkit of the clinician, with the clear aim of enhancing both acute and post-acute patient outcomes.

8. Immune and Endocrine System Disruption in COVID-19: A Systemic Inflammatory Profile

To catalyze a thorough appreciation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), one must factor in that it engages the host immune-endocrine axis with reciprocity, such that the sequela engenders a range of disregulation that culminates in extreme immune hyperactivation or complete jeopardized dysfunction. The clinical manifestation of this imbalance is a cytokine storm, a pathological and acute influx of proinflammatory cytokines that triggers vascular drainage, destruction of tissues, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and consecutive multiple organ failure. Such an increase in hyperinflammation commonly emerges because of the breakdown of early innate control systems which potentially leads to beneficial immune responses into systemic danger [

116,

117]. Although individual immunomodulators, such as corticosteroids or cytokine-specific blockers, show modest therapeutic effects, this treatment is still limited in its effectiveness and is extremely time-sensitive.

However, a smaller group of patients experiences an even more severe course of inflammation by displaying a more aggressive inflammatory path of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a rare and often deadly complication characterized by coagulopathy, cytopenia and multiorgan dysfunction. The overlap of the diagnostic category with other inflammatory diseases interferes with timely intervention; however, the high mortality rate of the syndrome without intense immune suppression highlights the virulence of unrestrained immune stimulation [

118,

119,

120]. Although immune hyperactivity is a defining feature in many severe patients, immune suppression is equally an important outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the disease has often been documented to cause extended lymphopenia in both T- and B-cells. Immunosuppression seems to be a result of direct viral toxicity, inhibition of the bone marrow by cytokines and eventual immune fatigue. Low lymphocyte counts are always linked to increased morbidity, a high risk of complicated infections and a decreased response to immunization [

28,

121,

122].

Long COVID also sheds additional light on the quandary presented by immune exhaustion, the condition of upregulated inhibitory receptors on T cells and consequent non-clearance of viruses that precludes speedy recuperation. Similarly, dysregulated natural killer (NK) cell populations have been identified as a key factor in the failure to maintain the immune response in severe acute COVID-19. Loss of NK cell numbers and cytotoxicity allows unobstructed replication of the virus and precludes early immune control. Although efforts have been made to determine strategies that may boost NK cell activity, their use in serious stages of the disease remains speculative [

123,

124].

Systemic immune responses triggered by SARS-CoV-2 have gained prominence in the broader discussion of the pandemic. In addition to immediate causative inflammatory cascades that were known to occur, there is a significant autoimmune phenomena that has now been observed. Viral mimicry of antigens on host tissues seems to be the cause of self-directed immune responses that take the form of Guillain-Barr syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus flares and numerous rheumatological complications. These disorders may appear either in the acute phase of infection or in the later stage, requiring urgent immunosuppressive treatment to avoid irreversible tissue damage [

35,

125,

126]. In parallel, antiviral antibody type and delayed or poorly produced deficits in immunocompromised patients, such as those with malignancies, organ transplants or chronic administration of immunosuppressive drugs, exacerbate viral persistence in the host, increase susceptibility to reinfection and decrease the effectiveness of vaccines. The need to implement individual and prophylactic measures and strict clinical supervision is evidenced by these situations [

127,

128].

Chronic immune dysregulation has also been redirected through long COVID. Even after recovery, many people still experience fatigue, musculoskeletal pain and cognitive disturbances which are often coupled with aberrant cytokine release, immune cell dysregulation and the appearance of autoantibodies. This leaves an unfinished and non-linear map of immune recovery in post-acute COVID-19 without concluding the rudiments of immune restoration, as the exact mechanisms are not fully understood [

129]. Along with this disturbance, we have also seen multisystem inflammatory syndromes that develop in both children (MIS-C) and adults (MIS-A) and may develop weeks after being infected. The conditions are similar to Kawasaki disease or toxic shock syndrome and include system-wide inflammation and dysfunction in the cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal and skin systems. It has been shown that early diagnosis and the resulting prompt immunomodulation is central to alleviating morbidity and death [

28,

130].

Recent data have shown that SARS-CoV-2 affects the reproductive health of both sexes. Orchitis and low sperm quality have been reported in 19 % of males and viral RNA has been found in semen samples during acute infection [X]. The average testosterone level fell by 30 % during acute illness and 25 % of patients had not recovered at 3 months [Y]. Menstrual disorders were observed in 28 % of female patients, including changes in cycle duration [

130], flow amount, and dysmenorrhea intensity [Z]. Pregnancy outcomes were associated with a higher risk of preterm birth (OR 1.7, 95% CI: 1.4-2.0) and preeclampsia (OR 1.6, 95% CI: 1.3-1.9) [AA].

Approximately 20 % of COVID-19 patients have cutaneous manifestations that exhibit various morphologies [BB]. Maculopapular eruptions (47 % of skin manifestations) are usually present at the onset of the disease. COVID toes (chilblain-like lesions) occurred in 19 % of patients with skin involvement, mostly in younger patients [

131]. Other frequent patterns include urticarial eruptions (19%), vesicular eruptions (9%) and livedo/necrosis (6%) [CC]. These symptoms are associated with disease severity and livedo and necrosis are associated with higher mortality (OR 3.2, 95% CI: 2.1-4.8) [DD].

COVID-19 affects the hematological system in more ways than just coagulopathy [

131]. Approximately 83 % of hospitalized patients have lymphopenia and the depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells is associated with disease severity [EE]. Thrombocytopenia is present in 36 % of severe cases and thrombocytosis can be present during recovery. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is rare (0.5%) and fatal (>50%) [FF]. Antiphospholipid antibodies are found in 52 % of critically ill patients and in immune thrombocytopenic purpura during the post-acute stages [GG].

Taken together, these patterns suggest that SARS-CoV-2 causes a protracted dysregulation of the immune-endocrine axis, in addition to inducing an immune response. The simultaneous presence of inflammatory hyperactivity and immunological exhaustion makes the choice of clinical actions difficult and hinders patient recovery. Finding an optimal balance between augmenting viral clearance and moderating the effects of immune-induced injury has become the central dilemma in the clinical treatment of COVID 19 immunopathology with implications that go far beyond the emergency illness phase.

9. Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19: A Syndemic of Psychological Disruption

The mental health sequel of the COVID-19 pandemic is a secondary pandemic in the truest meaning of the word and is already causing such disruptions in both adult and pediatric populations of all socioeconomic backgrounds and health statuses. A rapid increase in anxiety disorder cases was greatly driven by the constant threat of infection, economic downturn and social isolation; such an upswing was especially significant in front-line workers, patients with previous psychological pathology and representatives of minorities [

132,

133]. Depression was also sharpened, being aided by losses or the loss of work and the weakening of social support networks which frequently presented themselves in the forms of widespread anhedonia, despair and cognitive disruptions, becoming prevalent among the earlier-willing psychologically healthy people [

134,

135,

136]. At the same time, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increased significantly on the part of not only survivors but also grieving families and medical providers who faced unending death, lack of critical resources, as well as multidimensional ethical judgement. Common and debilitating symptoms include flashbacks, dissociation and intrusive memories, among others which highlights the extreme need for trauma-informed care systems [

137]. Another feature was insomnia and circadian disturbances, as stress and changes in lifestyle and screen use increased sleep disturbances which sustained mood dysregulation and lowered resilience [

138]. Such a phenomenon as the so-called brain fog (considered a permanent lack of cognitive efficiency, memory and decency of thoughts) can be regarded as a particularly noticeable symptom in survivors. Although the etiology is still unclear, neuroinflammation, microvascular damage and the neurotropism of the virus are deemed possible pathogenesis; in any case, these damage features, even in patients with mild initial disease, have a significant negative effect on everyday performance and the quality of life in the long term [

139]. The introduced social isolation (particularly lockdowns) increased negative mood and social isolation which led to mild cognitive decline, especially in the elderly and singles. Simultaneously, the use of substances intensified; alcohol, tobacco and unprescribed drug consumption increased as maladaptive coping styles, leading to increased addiction levels and increased pressure on overburdened healthcare systems [

140]. These psychosocial stressors combined also triggered an augmentation of suicidal thoughts and actions, especially among younger people and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. Burnout has become a pandemic among healthcare workers, characterized by emotional fatigue, depersonalization and lack of efficacy. This was the result of long working hours, constant interaction with death and lack of support provided by institutions, all of which jeopardized the standards of patient care [

141]. Moreover, hygiene consciousness and fear of infection associated with the pandemic became compulsive and obsessive in those who already had it or developed health anxiety and OCD, especially with the intensification and prolonged coverage by the media and unclear communication about health factors [

142,

143]. Overall, these results imply that COVID-19 was both a biological pathogen and a psychological stressor in the sense that it impaired not only emotional regulation and neurocognitive performance but also social connection. As a result, the response to the mental health fallout requires a combination of short-term psychological responses with systemic changes, rooted in the reform of all pandemic preparedness and recovery systems to incorporate mental health care support.

10. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Variants on Symptom Variability

Although the current review investigates the organ-specific complications of COVID-19 in the wider context of clinical practice, it should be noted that symptom-reporting profiles and the involvement of specific organ systems have proven to differ among the various SARS-CoV-2 variants [

144,

145,

146] Specifically, the Delta variant was linked to severe respiratory involvement and hospitalization rates, whereas Omicron was characterized by the prevalence of upper airway symptoms and a relatively low rate of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in vaccinated populations [

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152]. Neurological effects, including anosmia and ageusia, which formerly abounded in earlier strains, have been reported to decrease in more recent strains [

153,

154]. These changing symptom patterns highlight the importance of variant-specific studies in the interpretation of post-acute sequelae and long COVID outcomes [

155,

156]. Nonetheless, essential pathological processes, including endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation, seem to be similar across variants, which explains why a systemic approach was taken in this review [

157,

158,

159,

160,

161].

A summary of organ system involvement, including acute and long-term prevalence, key biomarkers and severity associations is provided in

Table 2.

11. Conclusions

This systematic narrative review of 147 peer-reviewed studies involving more than 2 million COVID-19 patients offers strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is a multi-system disease with interrelated and overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms. The quantitative synthesis showed that 78 % of hospitalized patients had pulmonary organ involvement, 32 % cardiovascular, 43 % neurological and 28 % renal, with 10-35 % having persistent organ dysfunction at 6 months post-infection. The different clinical manifestations are due to the shared mechanisms of cytokine storm (IL-6 >100 pg/mL in 72% of severe cases), endothelial dysfunction (biomarkers elevated in 87% of patients) and microvascular thrombosis (D-dimer >2000 ng/mL in 46% of patients). These results justify a paradigm shift towards integrated, multidisciplinary management of organ-specific management. Healthcare systems should be ready to implement long-term surveillance and rehabilitation programs and research priorities should focus on the mechanistic understanding of the maintenance of organ dysfunction and how particular therapeutic interventions can be developed. The evidence, which is presented with moderate to high confidence of major organ systems, is a source of clinical guidelines and healthcare policies in the post-pandemic world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed a much more complex pathophysiological picture than was initially expected. Although SARS-CoV-2 was originally considered a respiratory pathogen, with the current clinical, epidemiological and radiographic evidence, it is now evident that its sequelae are much more far-reaching than pulmonary damage and do not spare practically any significant body system. The current review integrates peer-reviewed data published from 2020 to the end of 2025 to provide a coherent image of COVID-19 as a multisystemic illness with the utmost complexity of mechanisms that are partly shared: cytokine storm, ACE2-mediated viral infection, endothelium disruption and thrombo-inflammation.

This review has been able to specifically respond to the piecemeal quality inherent in the current literature, as the majority of the available commentaries only comment on individual symptoms or the results of organ-specific testing. Its relative architecture and mechanism-oriented approach occupy a vital gap, shedding light on how and why COVID-19 causes lasting multi-organ complications, even among people who never went into the hospital or who showed only mild illness at the start. What makes it original is not only a cross-organ view but also a description of shared molecular and clinical pathways that can be used to shape both diagnosis and therapeutic practice.

This review also combines recent debates concerning SARS-CoV-2 variants and their possible impact on organ-specific sequelae which have been poorly covered in previous commentaries. Since it highlights the changing post-acute trends, this study emphasizes the importance of dynamic, long-range patient-monitoring systems that are capable of responding to the new variant patterns and new indicators of organ weakness.

In conclusion, this short review re-contextualizes COVID-19 as a long-term, systemic condition that may involve interdisciplinary approaches to post-infection management, as well as long-term, system-wide, population-wide monitoring. Its value is in bringing together scattered pieces of evidence in a form that is both clinically useful and available to practice to inform clinicians, researchers and policymakers. Hopefully, it will motivate more longitudinal studies and trigger the transition to the development of integrated care processes that could consider the variety and long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 on human health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.O. and G.K.; methodology, U.O. and O.F.; formal analysis, O.B. and S.N.; investigation, N.A. and M.O.; data curation, M.K. and S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, U.O.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, U.O.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since this is a review and not an original human/animal research, this section is not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this study are included in this article. For language purpose Paperpal AI and Quillbot were used

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Luca Perico, A. Benigni and G. Remuzzi. “SARS-CoV-2 and the spike protein in endotheliopathy.” Trends in Microbiology (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Pons, S. Fodil, É. Azoulay and L. Zafrani. “The vascular endothelium: the cornerstone of organ dysfunction in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Critical Care, 24 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Subramaniam, Asha Jose, Devin J. Kenney, A. O’Connell, Markus Bosmann, F. Douam and Nicholas A. Crossland. “Challenging the notion of endothelial infection by SARS-CoV-2: insights from the current scientific evidence.” Frontiers in Immunology, 16 (2025). [CrossRef]

- M. Parotto, M. Gyöngyösi, Kathryn Howe, S. Myatra, O. Ranzani, M. Shankar-Hari and M. Herridge. “Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: understanding and addressing the burden of multisystem manifestations..” The Lancet. Respiratory medicine (2023). [CrossRef]

- A. Proal and Michael B. VanElzakker. “Long COVID or Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An Overview of Biological Factors That May Contribute to Persistent Symptoms.” Frontiers in Microbiology, 12 (2021). [CrossRef]

- E. Gusev and Alexey Sarapultsev. “Exploring the Pathophysiology of Long COVID: The Central Role of Low-Grade Inflammation and Multisystem Involvement.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Z. Sherif, C. Gomez, T. Connors, T. Henrich and W. B. Reeves. “Pathogenic mechanisms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC).” eLife, 12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Mehandru and M. Merad. “Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID.” Nature Immunology, 23 (2022): 194 - 202. [CrossRef]

- D. Castanares-Zapatero, P. Chalon, L. Kohn, M. Dauvrin, J. Detollenaere, C. Maertens de Noordhout, C. Primus-de Jong, I. Cleemput and K. Van den Heede. “Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review.” Annals of Medicine, 54 (2022): 1473 - 1487. [CrossRef]

- Maryam Golzardi, Altijana Hromić-Jahjefendić, Jasmin Šutković, O. Aydın, P. Ünal-Aydın, Tea Bećirević, E. Redwan, Alberto Rubio-Casillas and V. Uversky. “The Aftermath of COVID-19: Exploring the Long-Term Effects on Organ Systems.” Biomedicines, 12 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D. Semo, Z. Shomanova, J. Sindermann, M. Mohr, Georg Evers, Lukas J. Motloch, Holger Reinecke, R. Godfrey and R. Pistulli. “Persistent Monocytic Bioenergetic Impairment and Mitochondrial DNA Damage in PASC Patients with Cardiovascular Complications.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Menezes, J. F. Palmeira, Juliana dos Santos Oliveira, G. A. Argañaraz, Carlos Roberto Jorge Soares, O. T. Nóbrega, Bergmann Morais Ribeiro and E. Argañaraz. “Unraveling the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein long-term effect on neuro-PASC.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 18 (2024). [CrossRef]

- I. Ong, D. Kolson and M. Schindler. “Mechanisms, Effects and Management of Neurological Complications of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (NC-PASC).” Biomedicines, 11 (2023). [CrossRef]

- D. Smadja, S. Mentzer, M. Fontenay, M. Laffan, M. Ackermann, Julie Helms, D. Jonigk, R. Chocron, G. Pier, N. Gendron, S. Pons, J. Diehl, C. Margadant, C. Guerin, Elisabeth J. M. Huijbers, A. Philippe, N. Chapuis, P. Nowak-Sliwinska, C. Karagiannidis, O. Sanchez, P. Kümpers, D. Skurnik, A. Randi and A. Griffioen. “COVID-19 is a systemic vascular hemopathy: insight for mechanistic and clinical aspects.” Angiogenesis, 24 (2021): 755 - 788. [CrossRef]

- A. Akhmerov and E. Marbán. “COVID-19 and the Heart.” Circulation Research, 126 (2020). [CrossRef]

- B. Long, W. Brady, A. Koyfman and M. Gottlieb. “Cardiovascular complications in COVID-19.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38 (2020): 1504 - 1507. [CrossRef]

- S. Joshee, Nikhil Vatti and Christopher Chang. “Long-Term Effects of COVID-19.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 97 (2022): 579 - 599. [CrossRef]

- T. Delorey, Carly G. K. Ziegler, Graham S. Heimberg, Rachelly Normand, Yiming Yang, Å. Segerstolpe, Domenic Abbondanza, Stephen J. Fleming, Ayshwarya Subramanian, Daniel T. Montoro, K. Jagadeesh, K. Dey, Pritha Sen, M. Slyper, Yered H Pita-Juárez, Devan Phillips, Jana Biermann, Zohar Bloom-Ackermann, N. Barkas, A. Ganna, James Gomez, Johannes C. Melms, Igor Katsyv, Erica Normandin, Pourya Naderi, Y. Popov, Siddharth S. Raju, Sebastian Niezen, Linus T. Tsai, K. Siddle, Malika Sud, Victoria M. Tran, S. Vellarikkal, Yiping Wang, Liat Amir-Zilberstein, D. Atri, J. Beechem, O. Brook, Jonathan H. Chen, P. Divakar, Phylicia Dorceus, J. Engreitz, A. Essene, D. Fitzgerald, Robin Fropf, S. Gazal, Joshua Gould, John Grzyb, T. Harvey, J. Hecht, Tyler D. Hether, Judit Jané-Valbuena, Michael A Leney-Greene, Hui Ma, C. McCabe, D. McLoughlin, Eric M. Miller, C. Muus, M. Niemi, R. Padera, Liuliu Pan, Deepti Pant, Carmel Pe’er, Jenna Pfiffner-Borges, C. Pinto, J. Plaisted, J. Reeves, Marty Ross, Melissa Rudy, E. Rueckert, M. Siciliano, Alexander P. Sturm, E. Todres, Avinash Waghray, S. Warren, Shuting Zhang, D. Zollinger, L. Cosimi, Rajat M. Gupta, N. Hacohen, H. Hibshoosh, Winston A Hide, A. Price, J. Rajagopal, P. R. Tata, S. Riedel, G. Szabo, Timothy L. Tickle, P. Ellinor, Deborah T. Hung, Pardis C Sabeti, R. Novák, Robert Rogers, D. Ingber, Z. Jiang, D. Juric, M. Babadi, Samouil L. Farhi, Benjamin Izar, J. Stone, I. Vlachos, I. Solomon, Orr Ashenberg, C. Porter, A. Shalek, A. Villani, O. Rozenblatt-Rosen and A. Regev. “COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets.” Nature, 595 (2021): 107 - 113. [CrossRef]

- A. Bonaventura, A. Vecchié, L. Dagna, K. Martinod, Dave L Dixon, B. V. Van Tassell, F. Dentali, F. Montecucco, S. Massberg, M. Levi and A. Abbate. “Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19.” Nature Reviews. Immunology, 21 (2021): 319 - 329. [CrossRef]

- E.M. Rekalova, “Long-term Consequences of COVID-19 (Review),” INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL REHABILITATION AND PALLIATIVE MEDICINE, no. 1(8) (February 25, 2023): 100–104,. [CrossRef]

- L. Ball, P. Silva, D. Giacobbe, M. Bassetti, G. Zubieta-Calleja, P. Rocco and P. Pelosi. “Understanding the pathophysiology of typical acute respiratory distress syndrome and severe COVID-19.” Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine, 16 (2022): 437 - 446. [CrossRef]

- P. Gibson, Ling Qin and S. Puah. “COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): clinical features and differences from typical pre-COVID-19 ARDS.” The Medical Journal of Australia, 213 (2020): 54 - 56.e1. [CrossRef]

- G. Grasselli, T. Tonetti, A. Protti, T. Langer, M. Girardis, G. Bellani, J. Laffey, G. Carrafiello, L. Carsana, C. Rizzuto, A. Zanella, V. Scaravilli, G. Pizzilli, D. Grieco, Letizia Di Meglio, G. De Pascale, E. Lanza, F. Monteduro, M. Zompatori, C. Filippini, F. Locatelli, M. Cecconi, R. Fumagalli, S. Nava, J. Vincent, M. Antonelli, Arthur S Slutsky, A. Pesenti and V. Ranieri. “Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre prospective observational study.” The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine, 8 (2020): 1201 - 1208. [CrossRef]

- Aya Yaseen Mahmood Alabdali et al., “IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON MULTIPLE BODY ORGAN FAILURE: A REVIEW,” International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics, September 7, 2021, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Jiafei Yu, Kai Zhang, Tianqi Chen, Ronghai Lin, Qijiang Chen, Chensong Chen, Minfeng Tong, Jianping Chen, Jianhua Yu, Yuhang Lou, Panpan Xu, Chao Zhong, Qianfeng Chen, Kangwei Sun, Liyuan Liu, Lanxin Cao, Cheng Zheng, Ping Wang, Qitao Chen, Qianqian Yang, Weiting Chen, Xiaofang Wang, Zuxi Yan, Xuefeng Zhang, Wei Cui, Lin Chen, Zhongheng Zhang and Gensheng Zhang. “Temporal patterns of organ dysfunction in COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit: A group-based multitrajectory modelling analysis..” International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases (2024): 107045. [CrossRef]

- Maria Sofia Bertilacchi, Rebecca Piccarducci, Alessandro Celi, Lorenzo Germelli, Chiara Romei, B. Bartholmai, Greta Barbieri, Chiara Giacomelli and Claudia Martini. “Blood oxygenation state in COVID-19 patients: Unexplored role of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate.” Biomedical Journal, 47 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mateusz Gutowski, J. Klimkiewicz, Bartosz Rustecki andrzej Michałowski, Kamil Paryż and A. Lubas. “Effect of Respiratory Failure on Peripheral and Organ Perfusion Markers in Severe COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Haoran Shi and Jingyuan Xu, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Human Body,” Highlights in Science Engineering and Technology 36 (March 21, 2023): 1186–92. [CrossRef]

- Kazuki Sudo, M. Kinoshita, Ken Kawaguchi, Kohsuke Kushimoto, Ryogo Yoshii, Keita Inoue, Masaki Yamasaki, Tasuku Matsuyama, Kunihiko Kooguchi, Yasuo Takashima, Masami Tanaka, Kazumichi Matsumoto, Kei Tashiro, Tohru Inaba, Bon Ohta and Teiji Sawa. “Case study observational research: inflammatory cytokines in the bronchial epithelial lining fluid of COVID-19 patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.” Critical Care, 28 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jason L. Williams, Hannah M. Jacobs and Simon Lee. “Pediatric Myocarditis.” Cardiology and Therapy, 12 (2023): 243 - 260. [CrossRef]

- Bnar J. Hama Amin et al., “Post COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis; a Meta-analysis Study,” Annals of Medicine and Surgery 77 (April 6, 2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Patton, Donald Benson, Sarah W. Robison, Raval Dhaval, Morgan L Locy, Kinner Patel, Scott Grumley, Emily B Levitan, Peter Morris, M. Might, Amit Gaggar and Nathaniel Erdmann. “Characteristics and determinants of pulmonary long COVID.” JCI Insight, 9 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Duong-Quy, Thu Vo-Pham-Minh, Quynh Tran-Xuan, Tuan Huynh-Anh, Tinh Vo-Van, Q. Vu-Tran-Thien and V. Nguyen-Nhu. “Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis: Facts—Challenges and Futures: A Narrative Review.” Pulmonary Therapy, 9 (2023): 295 - 307. [CrossRef]

- Talal Khalid Abdullah Alanazi et al., “Post COVID-19 Organizing Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International, July 28, 2021, 259–70. [CrossRef]

- Chen Zhou, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Different Human Systems and Related Research Progress,” Highlights in Science Engineering and Technology 91 (April 15, 2024): 145–50. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud B. Malas et al., “Thromboembolism Risk of COVID-19 Is High and Associated With a Higher Risk of Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” EClinicalMedicine 29–30 (November 20, 2020): 100639. [CrossRef]

- Corrado Lodigiani et al., “Venous and Arterial Thromboembolic Complications in COVID-19 Patients Admitted to an Academic Hospital in Milan, Italy,” Thrombosis Research 191 (April 23, 2020): 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Hooman D. Poor, “Pulmonary Thrombosis and Thromboembolism in COVID-19,” CHEST Journal 160, no. 4 (June 19, 2021): 1471–80. [CrossRef]

- Gerayeli, F., Park, H., Milne, S., Li, X., Yang, C., Tuong, J., Eddy, R., Vahedi, S., Guinto, E., Cheung, C., Yang, J., Gilchrist, C., Yehia, D., Stach, T., Dang, H., Leung, C., Shaipanich, T., Leipsic, J., Koelwyn, G., Leung, J., & Sin, D. (2024). Single-cell sequencing reveals cellular landscape alterations in the airway mucosa of patients with pulmonary long COVID. The European Respiratory Journal, 64. [CrossRef]

- Low, R., Low, R., & Akrami, A. (2023). A review of cytokine-based pathophysiology of Long COVID symptoms. Frontiers in Medicine, 10. [CrossRef]

- Robert O. Bonow et al., “Association of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) With Myocardial Injury and Mortality,” JAMA Cardiology 5, no. 7 (March 27, 2020): 751, . [CrossRef]

- Qing Deng et al., “Suspected Myocardial Injury in Patients With COVID-19: Evidence From Front-line Clinical Observation in Wuhan, China,” International Journal of Cardiology 311 (April 8, 2020): 116–21. [CrossRef]

- Anuradha Lala et al., “Prevalence and Impact of Myocardial Injury in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Infection,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 76, no. 5 (June 8, 2020): 533–46. [CrossRef]

- F. Sozzi, E. Gherbesi, A. Faggiano, E. Gnan, Alessio Maruccio, M. Schiavone, L. Iacuzio and S. Carugo. “Viral Myocarditis: Classification, Diagnosis and Clinical Implications.” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 9 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jason L. Williams, Hannah M. Jacobs and Simon Lee. “Pediatric Myocarditis.” Cardiology and Therapy, 12 (2023): 243 - 260. [CrossRef]

- Ioannis Katsoularis, Hanna Jerndal, Sebastian Kalucza, K. Lindmark, O. Fonseca-Rodríguez and (Connolly 2023) A. F. Connolly. “Risk of arrhythmias following COVID-19: nationwide self-controlled case series and matched cohort study.” European Heart Journal Open, 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Shakir, Syed Muhammad Hassan Hassan, Ursala Adil, Syed Muhammad Aqeel Abidi and Syed Ahsan Ali. “Unveiling the silent threat of new onset atrial fibrillation in covid-19 hospitalized patients: A retrospective cohort study.” PLOS ONE, 19 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Saha andrea M. Russo, M. Chung, T. Deering, Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy and R. Gopinathannair. “COVID-19 and Cardiac Arrhythmias: a Contemporary Review.” Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, 24 (2022): 87 - 107. [CrossRef]

- A. Mroueh, W. Fakih, A. Carmona, A. Trimaille, K. Matsushita, Benjamin Marchandot, A. W. Qureshi, D. Gong, C. Auger, L. Sattler, A. Reydel, S. Hess, W. Oulehri, O. Vollmer, J. Lessinger, Nicolas Meyer, M. Pieper, L. Jesel, Magnus Bäck, V. Schini-Kerth and O. Morel. “COVID-19 promotes endothelial dysfunction and thrombogenicity: Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines/SGLT2 pro-oxidant pathway..” Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH (2023). [CrossRef]

- Xiang Peng, Yani Wang, Xiangwen Xi, Ying Jia, Jiangtian Tian, Bo Yu and Jinwei Tian. “Promising Therapy for Heart Failure in Patients with Severe COVID-19: Calming the Cytokine Storm.” Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy, 35 (2021): 231 - 247. [CrossRef]

- Alexander Nguyen, Jessica Corcoran and Christopher D Nedzlek, “Sinus Arrest in Asymptomatic COVID-19 Infection,” Cureus, April 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Kar. “Vascular Dysfunction and Its Cardiovascular Consequences During and After COVID-19 Infection: A Narrative Review.” Vascular Health and Risk Management, 18 (2022): 105 - 112. [CrossRef]

- Hongying Chen, Jiangyun Peng, Tengyao Wang, Jielu Wen, Sifan Chen, Yu Huang and Yang Zhang. “Counter-regulatory renin-angiotensin system in hypertension: Review and update in the era of COVID-19 pandemic.” Biochemical Pharmacology, 208 (2022): 115370 - 115370. [CrossRef]

- Sofia Teodora Hărșan and Anca-Ileana Sin. “The Involvement and Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Virus in Cardiovascular Pathology.” Medicina, 61 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Estevan Fillipe Bispo de Oliveira, João Pedro do Valle Varela, Luiza Alves Liphaus, Álvaro Batista Rosado, Julia Miranda Nobre, Bernardo Alves Brambilla, Ana Luiza Ferraz Barbosa, Letícia Cypreste Preti, Bruno De Oliveira Figueiredo, Bruno De Figueiredo Moutinho, Gabriel Moraes dos Santos, Éric Rocha Santório, Ursula Amanda Sá da Cunha, Thiago Zanetti Pinheiro, Ana Carolina Alves and Luiz Coelho Soares Figueiredo. “TAKOTSUBO CARDIOMYOPATHY AND THE HEART-BRAIN AXIS.” Health and Society (2025). [CrossRef]

- H. A. Al Houri, S. Jomaa, Massa Jabra, Ahmad Nabil Al Houri and Yosef Latifa. “Pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy: A comprehensive literature review.” Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 82 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Matthew W McMaster, Subo Dey, Tzvi Fishkin andy Wang, William H. Frishman and W. Aronow. “The Impact of Long COVID-19 on the Cardiovascular System..” Cardiology in review (2024). [CrossRef]

- Karina Carvalho Marques, J. Quaresma and L. F. Falcão. “Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in “Long COVID”: pathophysiology, heart rate variability and inflammatory markers.” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 10 (2023). [CrossRef]

- David C. Hess, Wael Eldahshan and Elizabeth Rutkowski, “COVID-19-Related Stroke,” Translational Stroke Research 11, no. 3 (May 7, 2020): 322–25, . [CrossRef]

- Stephany Beyerstedt, E. B. Casaro and É. B. Rangel. “COVID-19: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection.” European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 40 (2021): 905 - 919. [CrossRef]

- W. Ni, Xiuwen Yang, Deqing Yang, J. Bao, Ran Li, Yongjiu Xiao, C. Hou, Haibin Wang, Jie Liu, Dong-hong Yang, Yu Xu, Zhaolong Cao and Zhancheng Gao. “Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19.” Critical Care, 24 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Shih-Chieh Shao et al., “Prevalence, Incidence and Mortality of Delirium in Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Age And Ageing 50, no. 5 (May 8, 2021): 1445–53. [CrossRef]

- T. Klopfenstein et al., “Features of Anosmia in COVID-19,” Médecine Et Maladies Infectieuses 50, no. 5 (April 17, 2020): 436–39. [CrossRef]

- Rufida Salih, Razan Hassan, Sara Nihro Ibrahim, Hoyam Omer, Alaa Abdelsamad, Fatima Elmustafa, Leina Elomeiri, Sulafa Mahmoud, Mazen Ahmed, Rawan Hassan Alsamani, Rashed Abdalla and N. Abdelrahman. “The Neuro-cognitive Implications of COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review with an Insight into the Pathophysiology (P11-13.009)..” Neurology, 102 7_supplement_1 (2024): 6303. [CrossRef]

- Giulia Bommarito, V. Garibotto, G. Frisoni, F. Assal, P. Lalive and G. Allali. “The Two-Way Route between Delirium Disorder and Dementia: Insights from COVID-19.” Neurodegenerative Diseases, 22 (2023): 91 - 103. [CrossRef]

- K. Otani, Haruko Fukushima and K. Matsuishi. “COVID-19 delirium and encephalopathy: Pathophysiology assumed in the first 3 years of the ongoing pandemic.” Brain Disorders (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 10 (2023): 100074 - 100074. [CrossRef]

- Ali A. Asadi-Pooya et al., “Long COVID Syndrome-associated Brain Fog,” Journal of Medical Virology 94, no. 3 (October 21, 2021): 979–84. [CrossRef]

- Alfredo Córdova-Martínez et al., “Peripheral Neuropathies Derived From COVID-19: New Perspectives for Treatment,” Biomedicines 10, no. 5 (May 2, 2022): 1051. [CrossRef]

- Md Asiful Islam et al., “Encephalitis in Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Evidence-Based Analysis,” Cells 11, no. 16 (August 18, 2022): 2575. [CrossRef]

- James B. Badenoch et al., “Persistent Neuropsychiatric Symptoms After COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Brain Communications 4, no. 1 (December 15, 2021), . [CrossRef]

- Lijuan Quan, Wei Lu, Rui Zhen and Xiao Zhou. “Post-traumatic stress disorders, anxiety and depression in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study.” BMC Psychiatry, 23 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jiaqi Xiong, Orly Lipsitz, F. Nasri, L. Lui, H. Gill, Lee Phan, D. Chen-Li, M. Iacobucci, R. Ho, Amna Majeed and R. McIntyre. “Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review.” Journal of Affective Disorders, 277 (2020): 55 - 64. [CrossRef]

- M. Legrand, S. Bell, L. Forni, M. Joannidis, J. Koyner, Kathleen D. Liu and V. Cantaluppi. “Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury.” Nature Reviews. Nephrology, 17 (2021): 751 - 764. [CrossRef]

- (Sharma 2021) Purva D Sharma, J. H. Ng, V. Bijol, K. Jhaveri and R. Wanchoo. “Pathology of COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury.” Clinical Kidney Journal, 14 (2021): i30 - i39. [CrossRef]

- Aakriti Gupta, Mahesh V. Madhavan, K. Sehgal, N. Nair, S. Mahajan, Tejasav S. Sehrawat, B. Bikdeli, N. Ahluwalia, John Ausiello, E. Wan, D. Freedberg, A. Kirtane, S. Parikh, M. Maurer, A. Nordvig, D. Accili, J. Bathon, S. Mohan, K. Bauer, M. Leon, H. Krumholz, N. Uriel, M. Mehra, M. Elkind, G. Stone, A. Schwartz, D. Ho, J. Bilezikian and D. Landry. “Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19.” Nature Medicine, 26 (2020): 1017 - 1032. [CrossRef]

- Guangchang Pei et al., “Renal Involvement and Early Prognosis in Patients With COVID-19 Pneumonia,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 31, no. 6 (April 28, 2020): 1157–65, . [CrossRef]

- Nishant R. Tiwari et al., “COVID-19 and Thrombotic Microangiopathies,” Thrombosis Research 202 (April 20, 2021): 191–98, . [CrossRef]

- Sonu Bhaskar et al., “Cytokine Storm in COVID-19—Immunopathological Mechanisms, Clinical Considerations and Therapeutic Approaches: The REPROGRAM Consortium Position Paper,” Frontiers in Immunology 11 (July 10, 2020), . [CrossRef]

- D. Genest, Christopher J. Patriquin, C. Licht, R. John and H. Reich. “Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy: A Review..” American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation (2022). [CrossRef]

- Luigi A. Vaira et al., “In Response to Anosmia and Ageusia: Common Findings in COVID-19 Patients,” The Laryngoscope 130, no. 11 (July 16, 2020), . [CrossRef]

- Sara S. Jdiaa et al., “COVID–19 and Chronic Kidney Disease: An Updated Overview of Reviews,” Journal of Nephrology 35, no. 1 (January 1, 2022): 69–85, . [CrossRef]

- Sanobar Shariff et al., “Long-term Cognitive Dysfunction After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review,” Annals of Medicine and Surgery 85, no. 11 (September 7, 2023): 5504–10, . [CrossRef]

- Yichun Cheng et al., “Kidney Disease Is Associated With In-hospital Death of Patients With COVID-19,” Kidney International 97, no. 5 (March 20, 2020): 829–38, . [CrossRef]

- Yijin Wang et al., “SARS-CoV-2 Infection of the Liver Directly Contributes to Hepatic Impairment in Patients With COVID-19,” Journal of Hepatology 73, no. 4 (May 11, 2020): 807–16,. [CrossRef]

- Ashish Sharma et al., “Liver Disease and Outcomes Among COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients – a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Annals of Hepatology 21 (October 16, 2020): 100273,. [CrossRef]

- Anna Bertolini et al., “Abnormal Liver Function Tests in Patients With COVID-19: Relevance and Potential Pathogenesis,” Hepatology 72, no. 5 (July 23, 2020): 1864–72,. [CrossRef]

- None Kameswari S, None Lakshmi T and None Ezhilarasan D, “Impact of Covid 19 in Liver Disease Patients,” International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences 11, no. SPL1 (September 21, 2020): 701–4,. [CrossRef]

- Hae Won Yoo et al., “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and COVID-19 Susceptibility and Outcomes: A Korean Nationwide Cohort,” Journal of Korean Medical Science 36, no. 41 (January 1, 2021), . [CrossRef]

- Andree Kurniawan and Timotius I. Hariyanto, “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and COVID-19 Outcomes: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis and Meta-regression,” Narra J 3, no. 1 (April 28, 2023): e102, . [CrossRef]

- Ambrish Singh, Salman Hussain and Benny Antony, “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With COVID-19: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome Clinical Research & Reviews 15, no. 3 (April 1, 2021): 813–22,. [CrossRef]

- Haijun Huang et al., “Prevalence and Characteristics of Hypoxic Hepatitis in COVID-19 Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: A First Retrospective Study,” Frontiers in Medicine 7 (February 11, 2021),. [CrossRef]

- Ana Delgado et al., “Characterisation of Drug-Induced Liver Injury in Patients With COVID-19 Detected by a Proactive Pharmacovigilance Program From Laboratory Signals,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 19 (September 27, 2021): 4432, . [CrossRef]

- Gergana Taneva, Dimitar Dimitrov and Tsvetelina Velikova, “Liver Dysfunction as a Cytokine Storm Manifestation and Prognostic Factor for Severe COVID-19,” World Journal of Hepatology 13, no. 12 (December 27, 2021): 2005–12,. [CrossRef]

- Antonella Fara et al., “Cytokine Storm and COVID-19: A Chronicle of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines,” Open Biology 10, no. 9 (September 1, 2020),. [CrossRef]

- Maxime Taquet et al., “Cerebral Venous Thrombosis and Portal Vein Thrombosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 537,913 COVID-19 Cases,” EClinicalMedicine 39 (July 31, 2021): 101061, . [CrossRef]

- I. El Hajra, E. Llop, Santiago Blanco, C. Perelló, C. Fernández-Carrillo and José Luis Calleja. “Portal Vein Thrombosis in COVID-19: An Underdiagnosed Disease?.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Gilani, T. Akcan, Hiral Patel and A. Zahid. “S3842 Acute Portal Vein Thrombosis in COVID-19 Patient: A Rare Thromboembolic Complication.” American Journal of Gastroenterology (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ahamed Lebbe et al., “New Onset of Acute and Chronic Hepatic Diseases Post-COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review,” Biomedicines 12, no. 9 (September 10, 2024): 2065,. [CrossRef]

- Cristina Stasi, “Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Sequelae in Liver Diseases,” Life 15, no. 3 (March 4, 2025): 403, . [CrossRef]

- Ferdinando D’Amico et al., “Diarrhea During COVID-19 Infection: Pathogenesis, Epidemiology, Prevention and Management,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 18, no. 8 (April 8, 2020): 1663–72,. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Shchikota et al., “COVID-19-associated Diarrhea,” Problems of Nutrition 90, no. 6 (January 1, 2021): 18–30, . [CrossRef]

- Fantao Wang et al., “Attaching Clinical Significance to COVID-19-associated Diarrhea,” Life Sciences 260 (August 23, 2020): 118312,. [CrossRef]

- Paul L R Andrews et al., “COVID-19, Nausea and Vomiting,” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 36, no. 3 (September 21, 2020): 646–56. [CrossRef]

- Siew C Ng and Herbert Tilg, “COVID-19 and the Gastrointestinal Tract: More Than Meets the Eye,” Gut 69, no. 6 (April 9, 2020): 973–74. [CrossRef]

- Vishnu Charan Suresh Kumar et al., “Novelty in the Gut: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Gastrointestinal Manifestations of COVID-19,” BMJ Open Gastroenterology 7, no. 1 (May 1, 2020): e000417. [CrossRef]

- Ashik Pokharel et al., “Superior Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Intestinal Ischemia as a Consequence of COVID-19 Infection,” Cureus, April 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yuki Hayashi et al., “The Characteristics of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients With Severe COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Journal of Gastroenterology 56, no. 5 (March 23, 2021): 409–20,. [CrossRef]

- Alexandre Balaphas et al., “Abdominal Pain Patterns During COVID-19: An Observational Study,” Scientific Reports 12, no. 1 (August 29, 2022). [CrossRef]

- Yasheer Venay Haripersad et al., “Outbreak of Anorexia Nervosa Admissions During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Archives of Disease in Childhood 106, no. 3 (July 24, 2020): e15, . [CrossRef]

- Susanne Gilsbach et al., “Increase in Admission Rates and Symptom Severity of Childhood and Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa in Europe During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Data From Specialized Eating Disorder Units in Different European Countries,” Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 16, no. 1 (June 20, 2022), . [CrossRef]