1. Introduction

Of the estimated 238,400 people diagnosed with lung cancer in the United States in 2023 [

1], 86% have non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Only 23% of NSCLC patients have localized disease with 22% having regional disease and nearly one-half (46%) having distant metastatic cancer [

2]. Five-year survival rates for regional (34%) and metastatic (8%) NSCLC are significantly lower than localized disease (61%) [

2].

The introduction of FDA-approved use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in 2015, including ipilimumab targeting CTLA-4 and nivolumab targeting PD-L-1, led to dramatic improvements in treatment response for NSCLC. However, only about 20% of metastatic NSCLC patients experience a clinical response from ICI therapy [

3], highlighting the importance of identifying patient characteristics that influence ICI response. Nutritional status, which is known to influence gut microbiome composition and systemic inflammation [

4], has been associated with ICI response among NSCLC patients. Previous research suggests that the diversity and composition of the gut microbiome may strongly influence ICI response, although results are somewhat inconsistent [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Furthermore, systemic inflammation is clinically relevant and likely strongly influences cancer-related malnutrition [

12]. Importantly, interventions such as dietary and nutritional counseling can improve nutritional status, making this an important factor to identify and understand in delivering ICI therapy for advanced NSCLC.

We aimed to examine nutritional status and related inflammatory markers among patients with stage III-IV NSCLC referred for ICI and to determine their associations with ICI response and overall survival in a prospective cohort study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

We prospectively recruited ICI treatment-naïve stage III-IV NSCLC patients with squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma scheduled to undergo single agent or combination ICI therapy at Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was approved by Advarra IRB, MCC# 18611, PRO00017235.

2.2. Clinical Metadata Abstraction

Socio-demographic data, physical exam, smoking history, comorbidity, and all routine pretreatment laboratory data were abstracted from MCC electronic medical records. Data were abstracted on diagnosis (histology and stage), number and types of previous treatments received, current medications prescribed, recent antimicrobial therapy use, type of ICI received (i.e., PD-L-1 or CTLA-4), height, weight, performance status, and comorbidities. Medical records were reviewed monthly until clinician-confirmed tumor progression or death. Clinician-assessed immunotherapeutic response, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and treatment-related adverse events at each clinical visit were recorded.

2.3. Treatment Response Assessment

In the past, response to immunotherapy was measured as with chemotherapy using conventional RECIST v1.1 criteria [

13] which utilizes the radiographic unidimensional measurement of the target tumor size. A decrease in tumor size is considered a partial response (PR) and complete resolution of the tumor (complete response---CR) indicates ICI effectiveness. Stability of tumor size (stable disease---SD) or enlargement of the tumor mass (progressive disease—PD) indicates tumor resistance to ICI—the so-called 2 vs 2 response [

14]. However, some tumors that respond to ICI treatment temporarily increase in size due to the influx of T cells and other inflammatory cells, along with edema, but in subsequent months the tumors shrink. These patients may erroneously be considered as non-responders due to “pseudo-progression,” which is later followed by tumor shrinkage [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, the best clinical indicator of the effectiveness of ICI response is the “Clinical Benefit” at 12 months with CR, PR, and SD, while PD at 12 months indicates a non-response (3 vs. 1 response). In other words, “Clinical Benefit” is best defined as progression-free survival at 12 months. The reasoning is that if a patient with the usual, aggressive lung cancer, undergoes immunotherapy and shows no progression of the cancer within 12 months, it indicates a definite treatment response even if they appear to have stable disease. Therefore, in this study, positive response to ICI (“Clinical Benefit”) is defined as 12-month progression-free survival.

2.4. Nutrition and Inflammation Indicators

We included assessments of indicators of pretreatment patient nutritional status, inflammatory status, and prognostic factors that were previously validated in the literature. All blood-based indicators were measured based on routine clinical blood draws that were taken prior to initiating ICI therapy.

2.4.1. Malnutrition Indicators

Pretreatment indicators of malnutrition include percentage of patient-reported weight loss (significant if >5%) over the last 12 months [

4]. Blood indicators included serum albumin (<3.5gm/dL indicates malnutrition) [

4,

18], serum sodium (<135mmol/L, associated with malnutrition and poorer OS) [

19,

20,

21], and hemoglobin (<12.5 gm/dL associated with malnutrition) [

22]. Some elevated blood cell counts are characteristic of malnutrition (in addition to inflammation) and include white blood cell count (increased mortality in cancer when elevated >12,000) [

23], total neutrophil count, total monocyte count and platelet count (when elevated >400,000 indicates inflammation and worse prognosis) [

24]. A low total lymphocyte count (<2000) indicates malnutrition [

18]. An elevated red cell distribution width (RDW >15) indicates inflammation, nutritional impairment and poor OS [

25]. We also calculated the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (>1.81 indicates inflammation, malnutrition, and poor OS in cancer) [

26,

27,

28], platelet to lymphocyte ratio (>150 associated with inflammation and poor OS) [

26,

29], monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (>0.58 indicates inflammation) [

30], and the lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (<2 indicates poor OS with lymphopenia) [

31].

We calculated the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index, which incorporates ideal body weight, actual weight, serum albumin to identify malnutrition (scores <98) [

32]. The Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA), which incorporates self-reported food intake, weight loss, mobility, psychological stress, acute disease in the past 3 months, neuropsychological problems, and BMI, was also used to identify malnutrition (scores <11) [

22,

33]. Finally, we calculated the Clinical Frailty Index (9-point scale with scores ≥4 identifying frailty with higher mortality based on physical functioning) [

34,

35], the Charlson Comorbidity Index [

36], and the Prognostic Nutritional Index (serum albumin + 5 x total lymphocyte count, with scores <51.4 indicating abnormal nutritional status) [

21]

2.4.2. Skeletal Muscle Indicators

We measured cross-sectional areas of skeletal muscle at the middle of the 12

th thoracic vertebra (T12) using single computerized tomography (CT) images and SliceOmatic software (Version 6, Tomovision, Magog, Canada). For each patient, T12 images were identified and extracted from two separate CT scans performed approximately 3-6 months apart: pre-treatment (prior to starting ICI) and following ICI completion. The dates of extracted T12 images were recorded to compute the number of weeks between scans. Images were selected and processed in a random order by a trained researcher maintaining blindness to both image timepoint and patient group (i.e., clinical benefit vs. no clinical benefit). Using published Hounsfield unit (HU) radiodensity limits for skeletal muscle (i.e., -29 to 150 HU), the combined cross-sectional area of the intercostals, abdominal wall muscles, trapezius, latissimus dorsi, serratus posterior, and paraspinals at T12 were measured in cm

2 and recorded for each CT scan [

37]. Skeletal muscle cross-sectional areas were standardized to patient stature (i.e., the square of height in m

2) to compute skeletal muscle index (SMI; cm

2/m

2). SMI was compared to established, sex-specific cut points to indicate sarcopenia (i.e., <20.8 cm

2/m

2 for females and <28.8 cm

2/m

2 for males) [

38], with sarcopenia associated with poor functional status and a predictor for reduced survival [

39] For each CT image, the average radiodensity (HU) of T12 skeletal muscle density (SMD) was also recorded for each scan to indicate degree of myosteatosis [

40], with a reduced SMD associated with functional impairment, systemic inflammation and reduced survival [

41]. In addition to point measurements, we computed change scores, percent changes, and rates of change (per week) for both SMI and SMD.

2.4.3. Systemic Inflammation

To reflect systemic inflammation, we calculated the Systemic Immune Response Index [SIRI (neutrophils X monocytes/lymphocytes), with >1.0 indicating inflammation] [

42] and the Systemic Immune Inflammation Index [SII (platelets X neutrophils/lymphocytes), with >1003 indicating inflammation and associated with poorer OS] [

26,

42].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To compare patient characteristics by immunotherapy Clinical Benefit, categorical variables were descriptively summarized by frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were described by mean and standard deviation. Pearson’s Chi-square test and either two-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to examine for differences in distributions of demographics and clinical variables between post-immunotherapy response and non-response groups. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) for the associations of nutritional and inflammatory indicators with clinical response. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval from immunotherapy start to the date of death or last visit (whichever occurred earlier). The Kaplan-Meier curve method and the log rank test were used to summarize OS distribution and test for difference in OS. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to evaluate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed using Schoenfeld residual correlation test. In multivariable modeling analyses, stepwise variable selection with a typical entry p-value criterion of < 0.15 was employed to build a parsimonious model. Two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Information

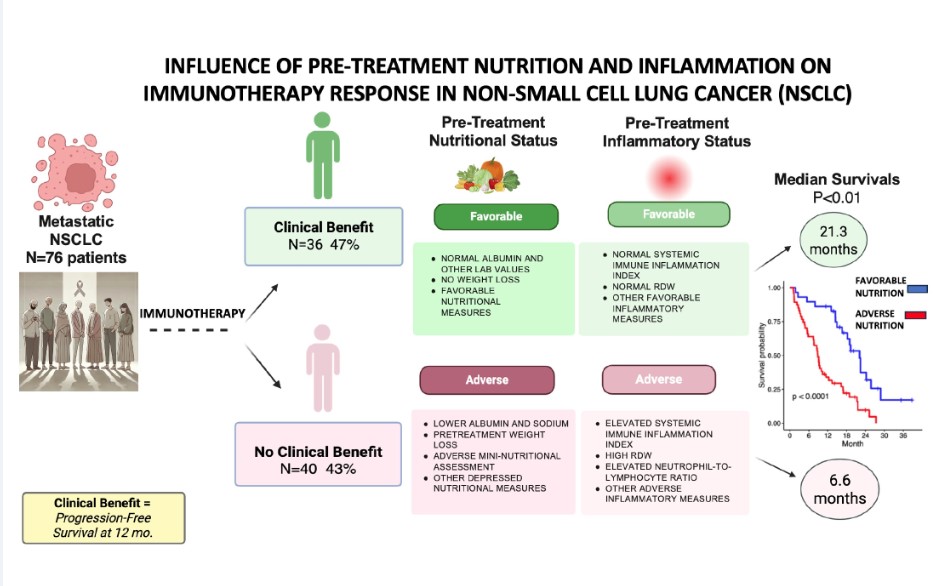

Of the 76 patients (

Table 1), there was a trend for more diabetic patients in the No-Clinical Benefit group (28% No-Clinical Benefit versus 11% Clinical Benefit, p=0.073). There were no other differences between the two groups based on cancer cell type, PD-L1 positivity, or immunotherapy regimen. PFS was longer in the Clinical Benefit versus No-Clinical Benefit groups (median 15.8 months versus 2.7 months, respectively, p<0.01). Likewise, OS was significantly longer in the Clinical Benefit versus the No-Clinical Benefit groups (median 21.3 months versus 6.6 months, respectively, p<0.01).

3.2. Nutritional and Inflammatory Indicators of Immunotherapy Response (Clinical Benefit)

Of the various nutritional status indicators examined (

Table 2), the most obvious indicator of adverse nutritional status was pre-treatment weight loss. Only 33% of Clinical Benefit patients had some degree of pretreatment weight loss versus 67% of No-Clinical Benefit patients (p=0.003). Although there was also a difference in mean percent weight loss between groups, the difference was not statistically significant. Of direct measured blood studies, serum albumin and RDW were statistically different between groups, with higher serum albumin (p=0.003) and lower RDW (p=0.044) in Clinical Benefit patients. The calculated indices of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index, Frailty Index and the Mini Nutritional Assessment were all statistically different with more favorable scores in the Clinical Benefit patients.

Of the various indicators of increased pre-treatment inflammation, the RDW and the Systemic Immune Response Index (SIRI) were both significantly elevated in the No-Clinical Benefit patients (p=0.044 and p=0.041, respectively). Other inflammation indicators were not statistically different.

For skeletal muscle analysis, our chest/abdomen CT scan-derived measures were the SMI (the indicator of sarcopenia) and the SMD (the indicator of myosteatosis or fatty muscle infiltration). Both of these indicators are strongly correlated with functional impairment, systemic inflammation and reduced survival [

39,

41]. Prior to starting ICI, there was no significant difference in the baseline degree of muscle atrophy/sarcopenia or muscle density (SMI or SMD). However, over the course of immunotherapy, there was a significantly more muscle atrophy and decline in muscle density in the no clinical benefit group (

Supplementary Table S1). Although almost all patients had some degree of muscle atrophy during treatment, it was noted that slower rates of both muscle atrophy and myosteatosis (i.e., decrease in SMI or SMD per week) were significantly associated with increased probability of complete response to immunotherapy in univariate analysis (Odds ratio (OR)=3.15, 95% confidence interval (CI): (1.73-6.39, and p<0.001 for SMI; OR=2.04, 95% CI: 1.14-4.23, and p<0.031 for SMD) and also multivariate analysis (OR=20.6, 95% CI:3.25-257, and p<0.01 for SMI; OR=9.46, 95% CI: 1.41-106, and p<0.017 for SMD).

The univariate logistic regression analysis finds Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), serum albumin, weight loss, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI), and total monocyte count significantly associated with Clinical Benefit. In addition, Systemic Immune Response Index (SIRI), Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI), WBC, and diabetes were borderline significantly associated with Clinical Benefit (

Figure 1).

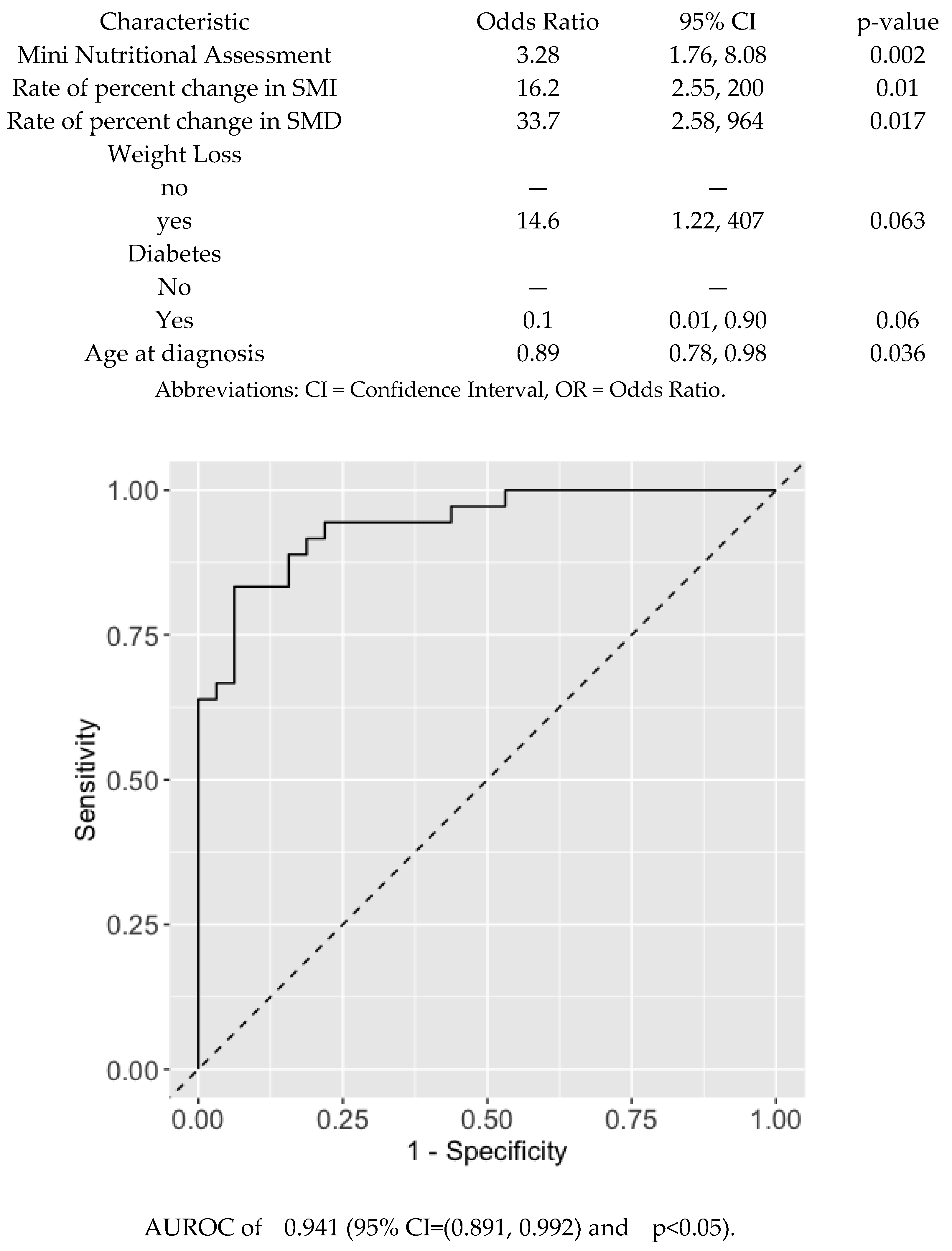

When a multivariable logistic regression model was applied using a stepwise variable selection adjusting for age and sex as key demographic variables, the model retained MNA index, rate of percent change in SMI and SMD, and age at diagnosis were significantly associated with Clinical Benefit. Weight loss and diabetes were borderline significantly associated with Clinical Benefit. However, only the MNA index and rate of percent change in SMI and SMD were significant while other variables had less significant association (

Figure 2).

A nomogram was used to visualize the model and facilitate the estimation of the probability of clinical benefit. The prediction accuracy of the multivariate model using MNA index and rate of percent change in SMI and SMD was significantly high in terms of an Area Under Receiver-Operator Characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.941 (95% CI=(0.891, 0.992) and p<0.05)

. (

Figure 2). Using MNA alone also had a significantly high prediction accuracy in terms of an Area Under Receiver-Operator Characteristic curve (AUROC) 0.886 (95% CI=0.813, 0.959, p<0.05). (

Supplementary Figure S1).

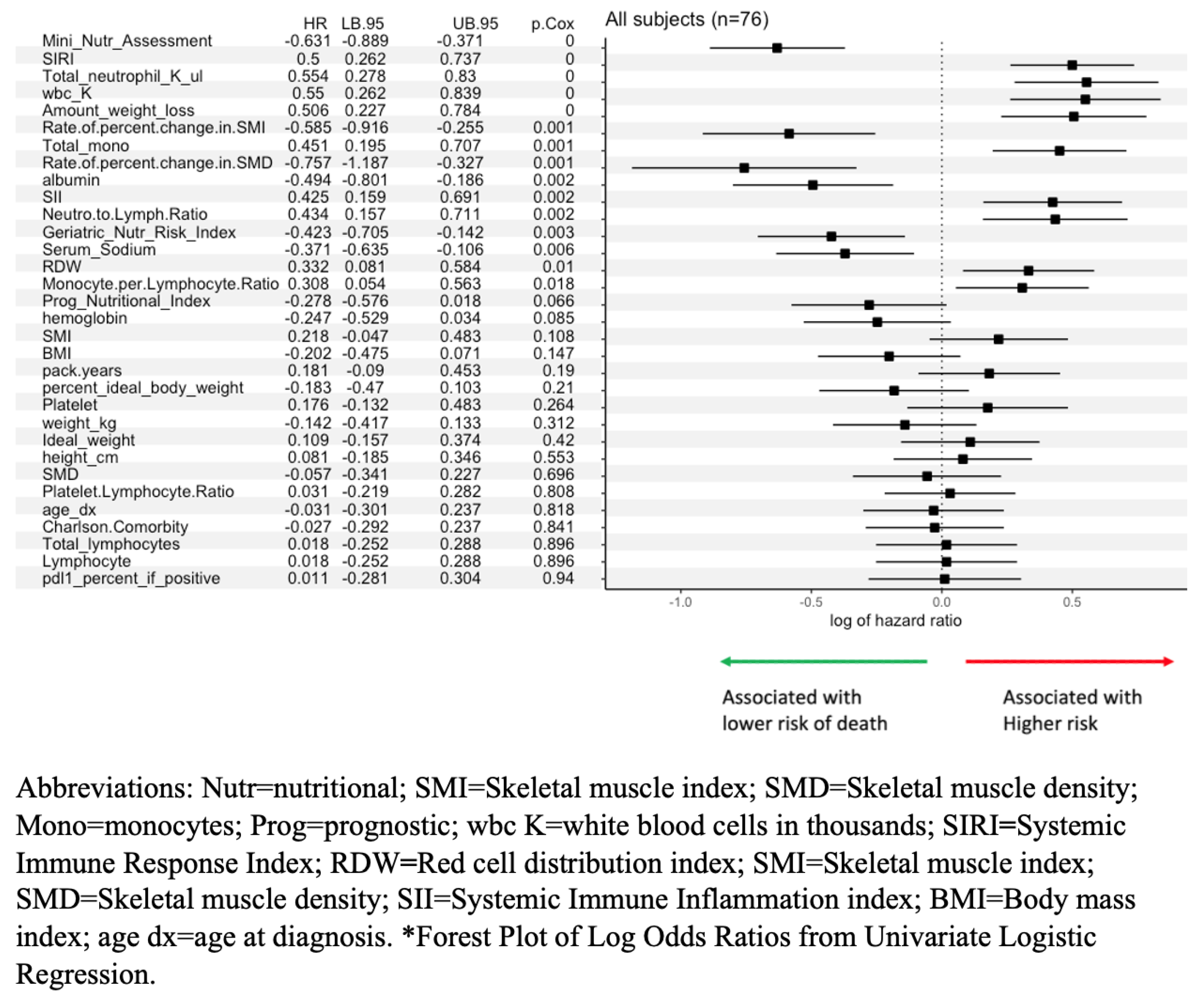

3.3. Nutritional and Inflammatory Indicators of Overall Survival After Immunotherapy

Demographic and nutrition variables that showed significant associations with post-immunotherapy survival include MNA, SIRI, total neutrophil count, total white blood cell count, amount of weight loss, rate of percent change in SMI, total monocyte count, rate of percent change in SMD, serum albumin, Systemic Immune Inflammation Index (SII), neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, GNRI, serum sodium, RDW, and monocyte to lymphocyte ratio. Borderline significant variables included PNI and hemoglobin (

Figure 3).

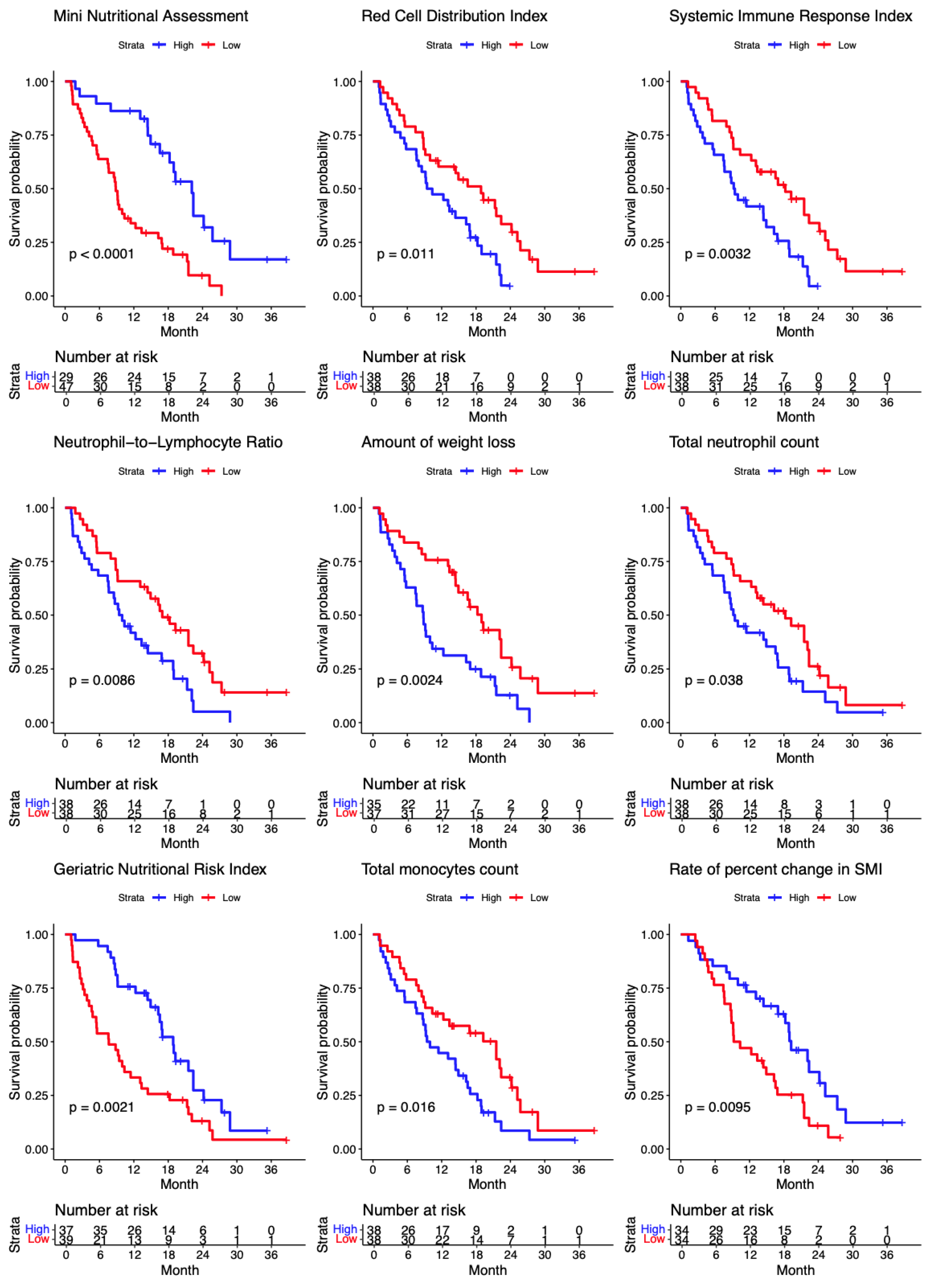

The Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival for the significant continuous variables upon the median split are shown (

Figure 4). The Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival for the significant categorical variables are shown in

Supplementary Figure S2.

Slower rates of both muscle atrophy and myosteatosis were significantly associated with lower risk of death (both p<0.001) on univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis

. In the multivariable analysis of OS after immunotherapy, rates of change in percent change in SMI and SMD, ECOG performance status, RDW, serum sodium, WBC, female gender and serum albumin are significant factors in predicting overall survival probability (

Supplementary Table S2). Increased percent change in SMI and SMD are associated with reduced risk of death by 62.5% (HR=0.275, 95% CI: 0.13-0.584) and 63% (HR=0.366, 95% CI: 0.154-0.872). Higher RDW and WBC are associated with higher risks (HR=1.1 (95% CI: 1.039-1.169) and 1.24 (95% CI: 1.039-1.169), respectively). Higher serum sodium and albumin are associated with decreased risk of death (HR=0.877 (95% CI: 0.809-0.951) and 0.416 (95% CI: 0.175-0.992). When the muscle index (SMI) and density (SMD) are excluded from the analysis, a higher MNA is associated with 20% lower risk of death (HR=0.8, 95% CI=0.71-0.9)

Supplementary Table S3. Also, a higher RDW and WBC are associated with higher risks of death (HR=1.09 (95% CI: 1.03-1.14) and 1.18 (95% CI: 1.08-1.29), respectively). Overall, a depressed nutritional status and evidence of inflammation were significant negative predictors of OS.

4. Discussion

A strong, dynamic relationship exists between nutritional state and immune function [

43]. A deficiency of numerous micro and macronutrients in the malnourished patient readily leads to poorly functional immune system and a pro-inflammatory state. Malnutrition to some degree is present in 15-40% of cancer patients at presentation, and is likely caused by an inflammatory state that promotes anorexia and weight loss [

44]. Furthermore it is well established that malnutrition can adversely influence medical and surgical treatment outcomes, impair wound healing, lead to sarcopenia and weakness, and worsen quality of life. A poor initial nutritional status, often termed cancer cachexia when weight loss >5%, will impair tolerance and response to most antineoplastic therapy types, including immunotherapy, which depends on a robust immune system for a positive effect [

44].

4.1. Current Study

In our prospective study of 76 advanced lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy, an impressive 36 (47%) met our criteria for Clinical Benefit with a progression-free survival at 1 year. Unfortunately, over one-half of all patients did not have a favorable response. The Clinical Benefit cohort had a progression-free median survival of 15.8 months versus 2.7 months in the No-Clinical Benefit group (p<0.01). The overall median survival was 21.3 months in the Clinical Benefit cohort versus 6.6 months in the No-Clinical Benefit group (p<0.01).

The purpose of our prospective study was to investigate individual pre-treatment patient characteristics that might account for this major disparity in clinical response. Non-responders had numerous pretreatment indicators of a depressed nutritional status and significant chronic inflammation.

The most obvious indicator of malnutrition is weight loss which was present in 68% of the patients who had No-Clinical Benefit from ICI. A number of highly sensitive and specific validated nutritional risk screening tools were employed. The No-Clinical Benefit cohort of patients had a depressed nutritional status as demonstrated by low serum albumin and high RDW, as well as adverse scores on the nutrition screening tools Geriatric Nutritional Risk index, the Frailty index and the Mini Nutritional Assessment (

Table 2). Each indicator had a significant correlation with overall survival (

Figure 4).

Furthermore, as expected, the No-Clinical Benefit group had significant chronic inflammation as documented by an elevated Systemic Immune Response Index and an elevated RDW. Malnutrition generally arises from an inflammatory state that results in anorexia and subsequent weight loss [

44].

Skeletal muscle measurements calculated from serial chest/abdomen CT scans over 3-6 months of immunotherapy are much different indicators of nutritional status and chronic inflammation as well as predictors of poor progression-free and overall survival [

38,

40]. The skeletal muscle index (SMI) is an indicator of sarcopenia, and the skeletal muscle density (SMD) is an indicator of myosteatosis or a higher presence of intramuscular fat infiltration. Both SMI and SMD are associated with functional impairment, systemic inflammation and reduced survival [

39,

41].

Although the pretreatment SMI and SMD were not significantly different in the ICI responders and non-responders, we found that there was a more rapid progression of sarcopenia (greater percentage of SMI loss per time) and more rapid progression of myosteatosis (greater percentage of SMD reduction per time) over time during immunotherapy in non-responders and were significantly associated with poor survivals. Since there was some degree of progressive sarcopenia and myosteatosis in all patients in both cohorts (significantly worse in non-responders), this problem strongly supports the need for prescribing resistance and exercise training for all patients during and after completing ICI treatment to minimize the cancer and treatment-related adverse effects of anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, decreased physical function, muscle weakness, and many other negative changes, as recommended by the 2019 Consensus Statement from an International Multidisciplinary Roundtable, the National Cancer Institute and others [

45,

46,

47]. Although the nutritionally-depressed patients who were non-responders to ICI treatment did not have pre-treatment evidence of a depressed skeletal muscle status, significantly more progressive sarcopenia and myosteatosis than the less nutritionally-impaired patients during ICI suggests that a pre-treatment catabolic state may be important to identify and target with interventions.

Overall, by multivariate analysis, the most accurate screening tool that predicts response to ICI pretreatment is the 6-measurement Mini Nutritional Index (AUC=.886, p<0.05) (

Figure 2). In the multivariable analysis of overall survival after immunotherapy, rates of change in percent change in SMI and SMD, ECOG performance status, RDW, serum sodium, WBC, gender and serum albumin are significant factors in predicting overall survival probability (

Supplementary Table S2). However, if the SMI and SMD which are measured over the course of ICI therapy are excluded from analysis, a higher pretreatment MNA score is significantly associated with 20% lower risk of death. Taken together, the quickest, most accurate validated tool easily-assessed at a pre-treatment clinic visit (without needing to wait for laboratory tests) for nutritional screening of oncology patients to predict ICI response is the MNA (

Supplementary Table S4), which also strongly correlates with WBC, RDW and the marital status.

4.2. Prior Studies

Over 4 decades ago, Dewys and associates analyzed data from 12 ECOG chemotherapy protocols and found that weight loss was associated with decreased median survival, even in patients with good performance status (ECOG 0) [

48]. Aside from the numerous studies documenting pretreatment malnutrition with reduced survival with chemotherapy in lung cancer [

12], Fiala and colleagues found that a low serum albumin as a marker for malnutrition in targeted therapy to be a negative predictor of PFS and OS in patients with metastatic NSCLC treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [

49]. In fact, malnutrition in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with the second generation EGFR-inhibitor afatinib had a much higher severe gastrointestinal toxicity risk and required dose reduction.

Shoji and associates reported in 2019 on 102 advanced NSCLC patients finding that an abnormally low Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) predicted a reduced OS after ICI therapy [

50], similar to the findings in the current study. Subsequently Lee and associates [

4] in 2020 retrospectively reviewed 106 patients undergoing ICI treatment for advanced NSCLC, finding that evidence of malnutrition based on pretreatment >5% weight loss and hypoalbuminemia were associated with a decreased OS. The current study also found that weight loss and hypoalbuminemia were significantly associated with decreased OS and PFS.

Although numerous published nutritional assessment indicators exist, the MNA has been shown to be a more sensitive baseline screening method than weight loss history in metastatic lung cancer patients for prediction of treatment response, time to progression and overall survival [

51]. The most recent published study by Madeddu and associates [

52] in 2023 looked prospectively at 74 advanced lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy. They found that an elevated level of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and adverse elevated miniCASCO score [

53] (assesses weight loss, inflammation, physical status and quality of life) are predictive of a poor clinical response to immunotherapy and a decreased progression-free survival and overall survival—confirming the findings of the current study.

Additionally, the presence of inflammation has a negative impact on ICI treatment results in NSCLC, as demonstrated in the present study with an elevated RDW and Systemic Immune Response Index. Although there is no consensus as to the best markers of inflammation, Kiriu and colleagues in 2019 found that elevated RDW, which reflects the variation in red cell volume, strongly correlates with inflammation and nutrition state, and was an independent factor predicting a worse OS and poor prognosis in NSCLC patients undergoing ICI treatment [

54]. Shiroyama and associates also found in ICI lung cancer patients that a pretreatment adverse advanced lung cancer inflammation index (BMI x serum albumin/NLR) and an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were strong prognostic factors for poor PFS and OS. Chronic inflammation facilitates resistance to treatment and progression of the tumor [

55]. Overall, no matter what indicators are employed, it is convincingly demonstrated that an adverse inflammatory status and poor nutritional status lead to immune system malfunction and poor response to immunotherapy in lung cancer [

12]

4.3. Mechanism

The vicious combination of malnutrition and chronic inflammation leading to cancer cachexia and sarcopenia strongly impacts the immune system, impairing response to therapy. Malnutrition impairs the ability of lymphocytes to proliferate and produce interferon-gamma, the cytokine responsible for inducing an array of immune responses [

12]. Malnutrition with its deficiency in macro and micronutrients has an adverse effect on the gut microbiota leading to a dysbiotic microbiome that produces pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreased T-cells and natural-killer-cells resulting in immunodeficiency with depressed ICI response [

10,

56]. Systemic inflammation is a major driver of cancer-related malnutrition causing muscle wasting and liver metabolism change which sends signals of anorexia to the central nervous system [

12]. The hypoalbuminemia resulting from inflammation leads to increased vascular permeability with albumin leakage into the interstitial space providing materials for cell proliferation [

12]

An additional mechanism determining ICI response was described by Turner and colleagues [

57] who performed a retrospective analyses of data from large, randomized ICI trials (KEYNOTE-002 for melanoma and KEYNOTE-0101 for NSCLC) for 340 melanoma and 804 NSCLC patients treated with the ICI pembrolizumab, comparing OS to dose, exposure and baseline clearance of the ICI. They found that patients with a high clearance of pembrolizumab resulted in a poor OS, and subsequently looked at the clinical factors related to rapid ICI clearance. The major finding was that patients with cancer cachexia, defined as >5%weight loss, had the highest clearance of ICI and poorest OS. They postulated that those cachectic individuals suffering dramatic loss of weight and muscle strength have catabolic drivers of skeletal muscle loss that also result in catabolic clearance in an accelerated primary elimination pathway for pembrolizumab and other similar biologics.

4.4. Prehabilitation

When confronted with a NSCLC patient with weight loss and anorexia, the unfortunate usual recommendation is for the patient to drink a high sugar/high protein drink such as Boost

® or Ensure

®, and then proceed with immunotherapy as soon as possible. These seemingly beneficial high-refined-sugar/protein drinks may be counterproductive. The heavy, refined-glucose load elevates insulin levels (a cancer cell growth stimulator) [

58] and the release from the liver of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), a promotor of cell cycle progression, angiogenesis and metastasis [

59,

60,

61], in addition to leading to a dysbiotic inflammatory gut microbiome [

62].

With the extensive body of evidence documenting that malnutrition and chronic inflammation result in poor response to systemic therapy, especially ICI in advanced NSCLC patients, can we employ an intensive prehabilitation program that might improve their immune status prior to treatment [

63,

64]? For years oncologic surgeons have focused on early nutritional support before and after surgery for patients with moderate to severe nutritional risk, codified by the proven-effective enhanced-recovery-after-surgery (ERAS) program [

44]. The author recently published a large retrospective case-control series of 462 patients undergoing curative resection of thoracic neoplasms who benefitted from a short 5-day preoperative protocol [Nutritional-Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (N-ERAS)] that resulted in fewer complications and shorter hospital stays [

65].

Unfortunately, most oncologists have not focused on the highly important nutritional aspect of their advanced cancer patients’ status prior to treatment. Studies suggest that a short period of intensive nutritional prehabilitation along with added exercise can alter the efficacy of cancer treatment by improving immune competence and patients’ quality of life [

12,

44,

63,

66,

67]. Many techniques have been describe to modulate the gut microbiota to enhance the effects of ICIs including dietary modification which is perhaps the easiest to employ [

68]. Besides advocating for an anti-inflammatory diet, a recent, well-designed human trial [

69] showed that a fermented-food-enhanced diet (yogurt, kefir, kombucha, fermented vegetables, etc.) markedly decreased inflammatory markers and increased microbiome diversity that favorably modulated immune function. This approach may also be beneficial prior to ICI, and consequently we are currently accruing participants to a pre-treatment fermented foods trial in patients scheduled to undergo ICI treatment for NSCLC. Likewise, placing a metastatic lung cancer patient on a pre-treatment ketogenic diet regimen may improve patient outcomes by enhancing the effects of therapy through creation of an unfavorable metabolic environment thereby impeding tumor growth [

70,

71]. We are currently planning a similar ketogenic diet clinical trial in metastatic NSCLC patients who will undergo ICI treatment.

The most common measure of the patients’ physiological status during participation in prospective, randomized clinical trials of systemic cancer therapy is the ECOG performance status, which is used to evaluate the balance of randomized cohorts and is also used in the evaluation of results. As many as 40% of advanced cancer patients have been reported to have some degree of unintentional weight loss (51% in the current study). These cancer cachexia patients have a significantly decreased chance of responding to systemic therapy (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy) [

48]. Nevertheless, many of these patients with weight loss (who are poorly responsive to therapy) may still qualify as ECOG performance status 0 by the standard definition (“fully active, no performance restrictions”) [

72]. Therefore, major clinical trials may have significantly unbalanced cohorts with regard to nutritional status. Consequently, this imbalance may skew the results and trial conclusions. We therefore propose that a Nutritional Performance Status (NPS) classification (

Supplementary Table S5) be considered for inclusion in future prospective studies to balance treatment groups more accurately.

4.5. Limitations

Since this study is an unplanned post-hoc analysis of the data, one limitation is that we could not obtain several specific blood studies such as C-reactive protein, cytokine levels, and transferrin. However, the results using the available indicators are so definitive such that additional blood studies would be interesting but would not likely modify the results. In addition, some patient data is based on patient recall which can be fallible, such as exact amounts of weight loss, although most patients are quite aware of changes in their weight, but perhaps not the exact amount.

5. Conclusions

Numerous published studies have documented the deleterious effect of pretreatment nutritional depletion and chronic inflammation on the response and survival rates with all forms of systemic therapy in advanced NSCLC. Using multiple blood and clinical indicators, our study has dramatically demonstrated that the patient with cancer cachexia with its concomitant chronic inflammation and the resultant immunosuppression has a markedly decreased chance of responding to ICI leading to a poor progression-free and overall survival. We recommend using the easy-to-use MNA indicator with all new patients, which is much better at predicting survival/clinical benefit than the lauded PD-L-1 score. When depressed, that patient should be promptly referred for pre-treatment intensive nutritional counseling. Considering the marked negative effect of malnutrition on systemic treatment response in patients who still qualify as ECOG performance status 0-1 patients, prospective clinical trials should also match their cohorts by nutritional status, or they run the risk of unbalanced cohorts and invalid results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Multivariable Mini Nutritional Assessment Model Estimating the Probability of Clinical Benefit; Fig. S2: Categorical Variables with Significant Survival Association; Table S1: Skeletal Muscle Indicators of Clinical Benefit; Table S2: Multivariable Analysis of Overall Survival; Table S3: Multivariable Analysis of Factors Affection Overall Survival After Immunotherapy; Table S4: Mini Nutritional Assessment; Table S5: Nutritional Performance Status (NPS).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.P. and L.A.R.; methodology, Y.K., G.M.D., C.M.P. and L.A.R.; software, Y.K., S.H., A.B.; validation, C.M.P., D.A.B. and Y.K.; formal analysis, Y.K., S.H., N.P., G.M.D., L.A.R., and D.A.B.; investigation, L.A.R. and C.M.P.; resources, L.A.R. and C.M.P.; data curation, L.A.R., N.P., A.B., S.H., W.V.D.S., B.C. and D.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.R., N.P. and Y.K.; writing—review and editing, L.A.R., Y.K., N.P., A.B., G.M.D., D.A.B., S.H., B.C., C.M.P. and W.V.D.S.; visualization, L.A.R.; supervision, L.A.R.; project administration, L.A.R. and C.M.P.; funding acquisition, L.A.R. and C.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants from the Hoenle Foundation, Sarasota, FL and Florida Academic Cancer Center Alliance. These funding sources was not involved in the study design, data collection and interpretation or writing of the report.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by This study was approved by Advarra IRB, MCC# 18611, PRO00017235.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available due to patient privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. AI was not used in the analysis nor the creation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript |

. |

| AUROC |

Area Under Receiver-Operator Characteristic curve |

|

BMI |

Body mass index. |

|

CI |

Confidence interval. |

|

CR |

Complete response. |

|

CT |

Computed tomography. |

|

CTLA-4 |

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4. |

|

ECOG |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. |

|

ERAS |

Enhanced recovery after surgery. |

|

FDA |

Federal Drug Administration. |

|

GNRI |

Geriatric Nutritional Response Index. |

|

HR |

Hazard ratio. |

|

HU |

Hounsfield Unit. |

|

ICI |

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. |

|

IGF-1 |

Insulin-like growth factor-1. |

|

IRB |

Institutional Review Board. |

|

MCC |

Moffitt Cancer Center. |

|

MNA |

Mini Nutritional Assessment. |

|

N-ERAS |

Nutritional enhanced recovery after surgery. |

|

NLR |

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio. |

|

NPS |

Nutritional performance status. |

|

NSCLC |

Non-Smal-cell lung cancer. |

|

PD |

Progressive disease. |

|

PD-L-1 |

Programmed death-ligand-1. |

|

PR |

Partial response. |

|

PFS |

Progression free survival. |

|

PNI |

Prognostic Nutritional Index. |

|

OR |

Odds ratio. |

|

OS |

Overall survival. |

|

RDW |

Red cell distribution width. |

|

SD |

Stable disease or Standard deviation. |

|

SII |

Systemic Immune Inflammation index. |

|

SMD |

Skeletal muscle density. |

|

SMI |

Skeletal muscle index. |

|

SIRI |

Systemic Immune Response Index. |

|

T12 |

12th Thoracic Vertebra. |

|

WBC |

White blood cell. |

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;73:17-48. [CrossRef]

- Society AC. Cancer Facts and Figures 2023 Atlanta, GA2023 [June 17, 2023]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2023-cancer-facts-figures.html.

- Abdayem P, Planchard D. Safety of current immune checkpoint inhibitoirs in non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2021;20:651-67.

- Lee C-S, Devoe CE, Zhu X, Fishbein JS, Seetharamu N. Pretreatment nutritional status and response to checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Lung Cancer Management. 2020;9:LMT31.

- Nagasaka M, Sexton R, Alhasan R, Rahman S, Azmi AS, Sukari A. Gut microbiome and response to checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer—A review Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;145:102841.

- Liu X, Cheng Y, Zang D, et.al. The role of gut microbiota in lung cancer: From carcinogenesis to immunotherapy. Fronteirs Oncology. 2021;11:720842.

- Griffin ME, Hang HC. Microbial mechanisms to improve immune checkpoint blockade responsiveness. Neoplasia. 2022;31:100818.

- Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et.al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91-7.

- Matson V, Fessler J, Bao R, et.al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359:104-8.

- Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, et.al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359:97-103.

- Derosa L, Routy B, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. The intestinal microbiota determines the clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint blockers targeting PD-1/PD-L1. OncoImmunology. 2018;7:e1434468. [CrossRef]

- Baldessari C, Guaitoli G, Valoriani F, Bonacini R, Marcheselli R, et.al. Impact of body composition, nutritional and inflammatory status on outcome of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2021;43:64-75.

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, al. e. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). European J Cancer. 2009;45:228-47.

- Hodi FS, Hwu W-J, Kefford R, al. e. Evaulation of immune-related response criteria and RECIST v1.1 in patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. J Clin Oncology. 2016;34:1510-7.

- Kataoka Y, Hirano K, Narabayashi T, et.al. Concordance between the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors version 1.1 and the immune-related response criteria in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2018;81:333-7.

- Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, et.al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: Immune-related response criteria Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15:7512-20.

- Hochmair MJ, Schwab S, Burghuber OC, Krenbek D, Prosch H. Symptomatic pseudo-progression followed by significant treatment response in two lung cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2017;113:4-6.

- Rocha NP, Fortes RC. Total lymphocyte count and serum albumin as predictors of nutritional risk in surgical patients. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28:193-6.

- Castillo JJ, Glezerman IG, Boklage SH, Chiodo J, Tidwell BA, Lamerato LE, et al. The occurence of hyponatremia and its importance as a prognostic factor in a cross-section of cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:564.

- Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Hyponatremia. New England J Medicine. 2000;342:1581-9.

- Zhao L, Zhao X, Tian P, Liang L, Huang B, Huang L, et al. Prognostic utility of the prognostic nutritional index combined with serum sodium level in patients with heart failure. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2022;32:1894-902.

- Fatyga P, Pac A, Fedyk-Lukasik M, Grodzicki T, Skalska A. The relationship between malnutrition risk and inflammatory biomarkers in outpatient geriatric population. European Geriatric Medicine. 2020;11:383-91.

- Shankar A, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, et.al. Association between circul;ating white blood cell count and cancer mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2006;166:188-94.

- Barlow M, Hamilton W, Ukoumunne OC, Bailey SER. The association between thrombocytosis and subtype of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Translational Cancer Research. 2021;10:1249-60. [CrossRef]

- Hu L, Li M, Ding Y, Pu L, Liu J, Xie J, et al. Prognostic value of RDW in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:16027-35.

- Janicic A, Petrovic M, Zekovic M, Vasilic N, Coric V, Milojevic B, et al. Prognostic significance of systemic inflammatioin markers in testicular and penile cancers: A narrative review of current literature. Life. 2023;13:600.

- Song M, Graubard BI, Rabkin CS, Engels E. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ration and mortality in the United States general population. Scientific Reports. 2021;11:464.

- Kaya T, Acikgoz SB, Yildirim M, Nalbant A, Altas AE, Cinemre H. Association between neurtophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and nutritional status in geriatric patients. J Clin Lab Analysis. 2018;33:e22636.

- Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mukanova U, Yessirkepov M, Kitas GD. The platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as an inflammatory marker in rheumatic diseases. Annals Laboratory Medicine. 2019;39:345-57.

- Xu Z, Zhang J, Zhong Y, Mai Y, Huang D, Wei W, et al. Predictive value of the monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e27244.

- Nishijima TF, Muss HB, Shachar SS, Tamura K, Takamatsu Y. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and metanalysis. Cancer Treatmentr Reviews. 2015;41:971-8.

- Su W-T, Wu S-C, Huang C-Y, Chou S-E, Tsai C-H, Li C, et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index as a Screening Tool to Identify Patients with Malnutrition at a High Risk of In-Hospital Mortality among Elderly Patients with Femoral Fractures—A Retrospective Study in a Level I Trauma Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:8920. [CrossRef]

- Reber E, Gomes F, Vasiloglou MF, Schuetz P, Stanga Z. Nutritional risk screening and assessment. J Clinical Medicine. 2019;8:1065.

- Kojima G, Iliffe S, Walters K. Frailty index as a predictor of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Aging. 2018;47:193-200.

- Research GM. Clinical Frailty Scale 2020 [June 24, 2023]. Available from: https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html.

- Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, C. P. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91:8-35.

- He S, Zhang G, Huang N, Chen S, Ruan L, Liu X, et al. Utilizing the T12 skeletal muscle index on computed tomography images for sarcopenia diagnosis in lung cancer patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2024;11(6):100512. Epub 2024/07/08. PubMed PMID: 38975610; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC11225817. [CrossRef]

- Derstine BA, Holcombe SA, Ross BE, Wang NC, Su GL, Wang SC. Skeletal muscle cutoff values for sarcopenia diagnosis using T10 to L5 measurements in a healthy US population. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):11369. [CrossRef]

- Yeh KY, Ling HH, Ng SH, Wang CH, Chang PH, Chou WC, et al. Role of the Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Index for Predicting the Recurrence-Free Survival of Head and Neck Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(2). Epub 2021/03/07. PubMed PMID: 33673006; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7918727. [CrossRef]

- Scopel Poltronieri T, de Paula NS, Chaves GV. Skeletal muscle radiodensity and cancer outcomes: A scoping review of the literature. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2022;37(5):1117-41. [CrossRef]

- Calixto-Lima L, Wiegert EVM, Oliveira LC, Chaves GV, Bezerra FF, Avesani CM. The association between low skeletal muscle mass and low skeletal muscle radiodensity with functional impairment, systemic inflammation, and reduced survival in patients with incurable cancer. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2023;47(2):265-75. Epub 2022/11/04.PubMed PMID: 36325962. [CrossRef]

- Chu M, Luo Y, Wang D, Liu Y, Wang D, Wang Y, et al. Systemic inflammation response index predicts 3-month outcome in patients with mild acute ischemic stroke receiving intravenous thrombolysis. Fronteirs in Neurology. 2023;14:1095668.

- Munteanu C, Schwarttz B. The relationship between nutrition and the immune system. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022;9:1082500.

- Ravasco, P. Nutrition in cancer patients. J Clinical Medicine. 2019;8:1211.

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2375-90. Epub 2019/10/19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst C, Robinson SM, Witham MD, Dodds RM, Granic A, Buckland C, et al. Resistance exercise as a treatment for sarcopenia: prescription and delivery. Age and Ageing. 2022;51(2). [CrossRef]

- Schmitz KH. Prescribing Exercise as Cancer Treatment Bethesda, MD2019 [April 13, 2025].

- Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, et.al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior tochemotherapy in cancer patients. American J Medicine. 1980;69:491-7.

- Fiala O, Pesek M, Finek J, et.al. Serum albumin is a strong predictor of survival in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib. Neoplasma. 2016;63:471-6.

- Shoju F, Takeoka H, Kozuma Y, et.al. Pretreatment prognostic nutritional index as a novel biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer Management. 2019;136:45-51.

- Gioubasanis I, Baracos VE, Giannousi Z, et.al. Baseline nutritional evaluation in metastatic lung cancer patients: Mini Nutritional Assessment versus weight loss history. Annals of Oncology. 2011;22:835-41.

- Madeddu C, Busquets S, Donisi C, Lai E, Pretta A, López-Soriano FJ, et al. Effect of Cancer-Related Cachexia and Associated Changes in Nutritional Status, Inflammatory Status, and Muscle Mass on Immunotherapy Efficacy and Survival in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(4). Epub 2023/02/26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiles JM, Betancourt A, Guardeia-Olmos J, Pero-Cebollero M, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Madeddu C, et al. Validation of the CAchexia SCOre (CASCO). Staging Cancer Patients: The Use of miniCASCO as a Simplified Tool. `. 2017;8:2017. [CrossRef]

- Kiriu T, Yamamoto M, Nagano T, et.al. Prognostic Value of Red Blood Cell Distribution Width in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Anti-programmed Cell Death-1 Antibody. In Vivo. 2019;33:213-20.

- Zhao H, Wu L, Yan G, et.al. Inflamation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2021:263. [CrossRef]

- Salazar N, Valdes-Varela L, Gonzalez S, et.al. Nutrition and the gut microbiome in the elderly. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:82-97.

- Turner DC, Kondic AG, Anderson KM, et.al. Pembrolizumab Exposure-Response Assessments Challenged by Association of Cancer Cachexia and Catabolic Clearance. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5841-9.

- Vigneri R, Sciacca L, Vigneri P. Rethinking the relationship between insulin and cancer. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2020;31:551-60.

- Melnik BC, John SM, Schmitz G. Over-stimulation of insulin/IGF-1 signaling by western diet may promote diseases of civilization: lessons learnt from laron syndrome. Nutr Metab (London). 2011;8:41.

- Major JM, Laughlin Ga, Kritz-Silverstein D, et.al. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I and Cancer Mortality in Older Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95:1054-9.

- Nurwidya F, Andarini S, Takahashi F, et.al. Implications of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor activation in lung cancer. Malays J Med Sci. 2916;23:9-21.

- Brahmkhatri VP, Prasanna C, Atreya HS. Insulin-Like Growth Factor System in Cancer: Novel Targeted Therapies. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:538019.

- Kanarek N, Petrova B, Sabatini DM. Dietary modifications for enhanced cancer therapy. Nature. 2020;579:507-17.

- Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, et.al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune response. Cell. 2021;184:4137-53.

- Robinson LA, Tanvetyanon T, Grubbs D, et.al. Preoperative nutrition-enhanced recovery after surgery protocol for thoracic neoplasms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surgery. 2021;162:710-20.

- Bolte LA, Lee KA, Bjork JR, et.al. Association of a Mediterranean diet with outcomes for patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade for advanced melanoma. JAMA Oncology. 2023;9:705-9. [CrossRef]

- Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, et.al. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: An American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. Ca: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56:323-53.

- Huang J, Gong C, Zhou A. Modulation of the gut microbiota: a novel approach to enhancing the effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 2023;15(1-21).

- Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, et.al. Gut-microbiota-trageted diets modulate human immune status. Cell. 2021;184:4137-53.

- Neha, Chaudhary R. Ketogenic diet as a treatment and prevention strategy for cancer: A therapeutic alternative. Nutrition. 2024;124:112427. [CrossRef]

- Tan-Shalaby, J. Ketogenic Diets and Cancer: Emerging Evidence. Fed Pract. 2017;34(Suppl 1):37s-42s. Epub 2017/02/01. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6375425 with regard to this article. [PubMed]

- ECOG Performance Status Scale 2023. Available from: https://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).