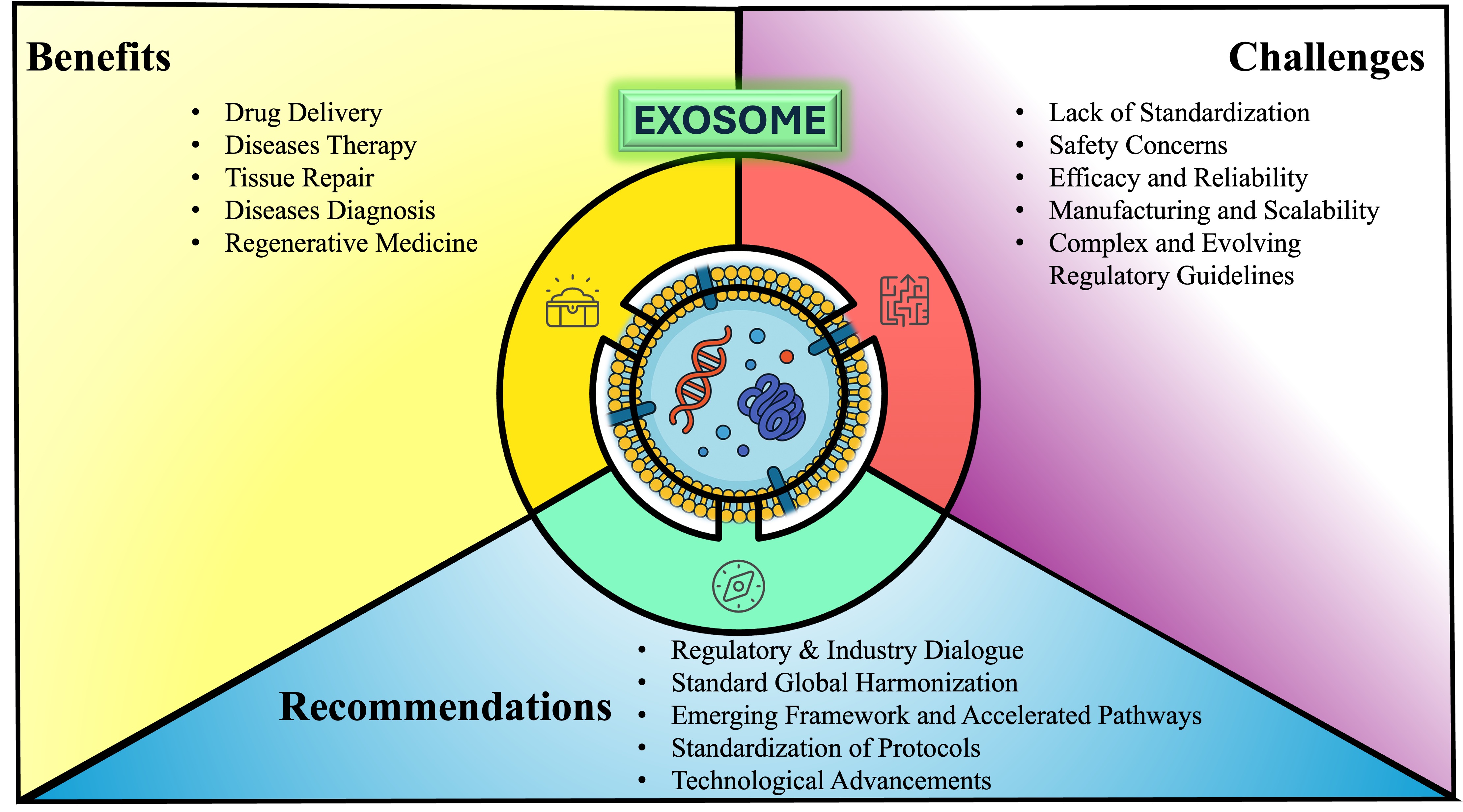

Figure 1.

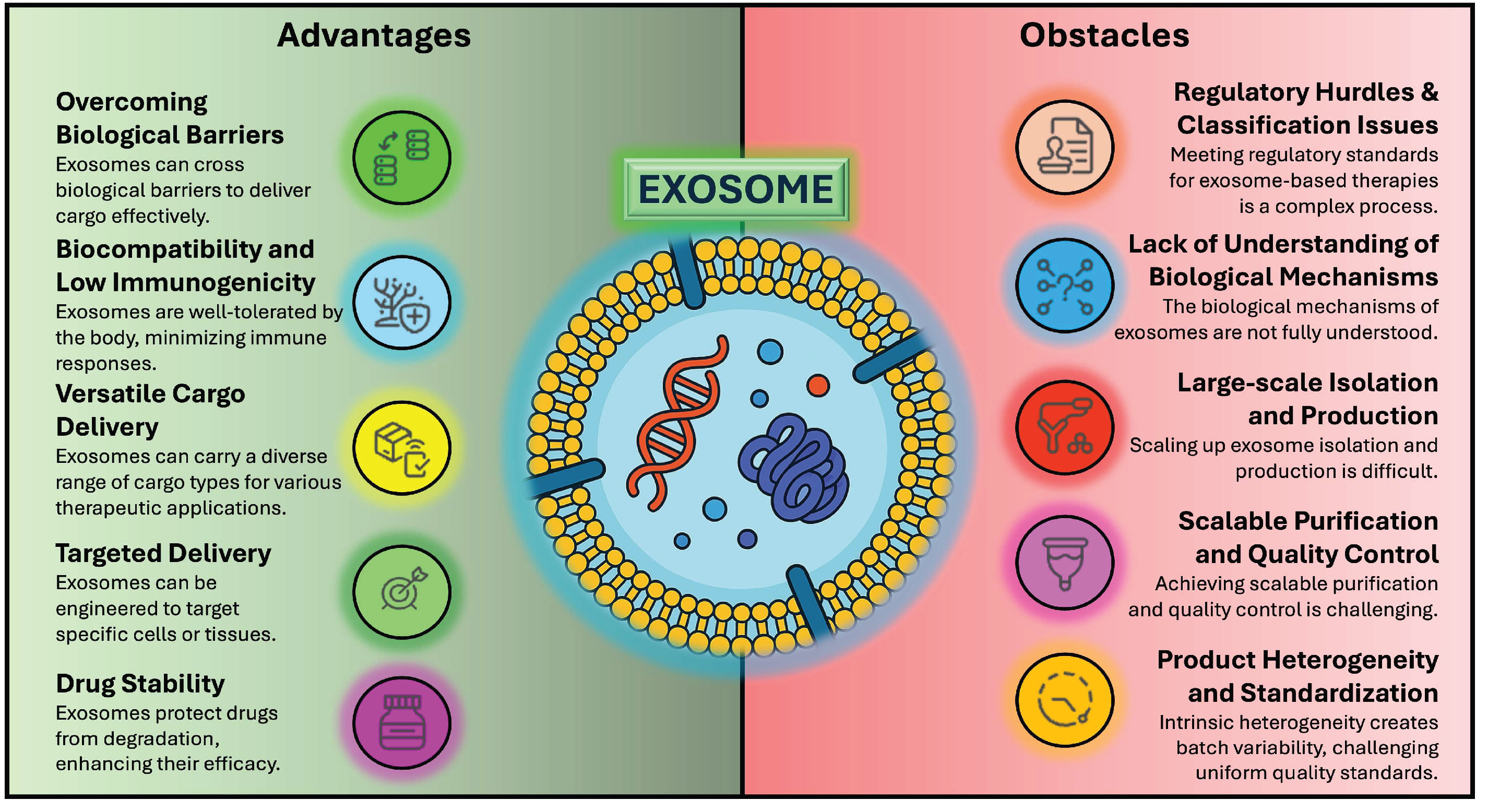

Graphical Abstract. This conceptual framework explains the exosome-based therapeutics landscape by highlighting its inherent benefits—efficient cargo delivery, biocompatibility, and precision targeting—while identifying key translational hurdles (standardization gaps, safety and efficacy concerns, manufacturing scale-up challenges, and regulatory complexity) and proposing strategic measures—global regulatory harmonization, accelerated approval pathways, standardized protocols, and ongoing technological innovation—to accelerate clinical integration.

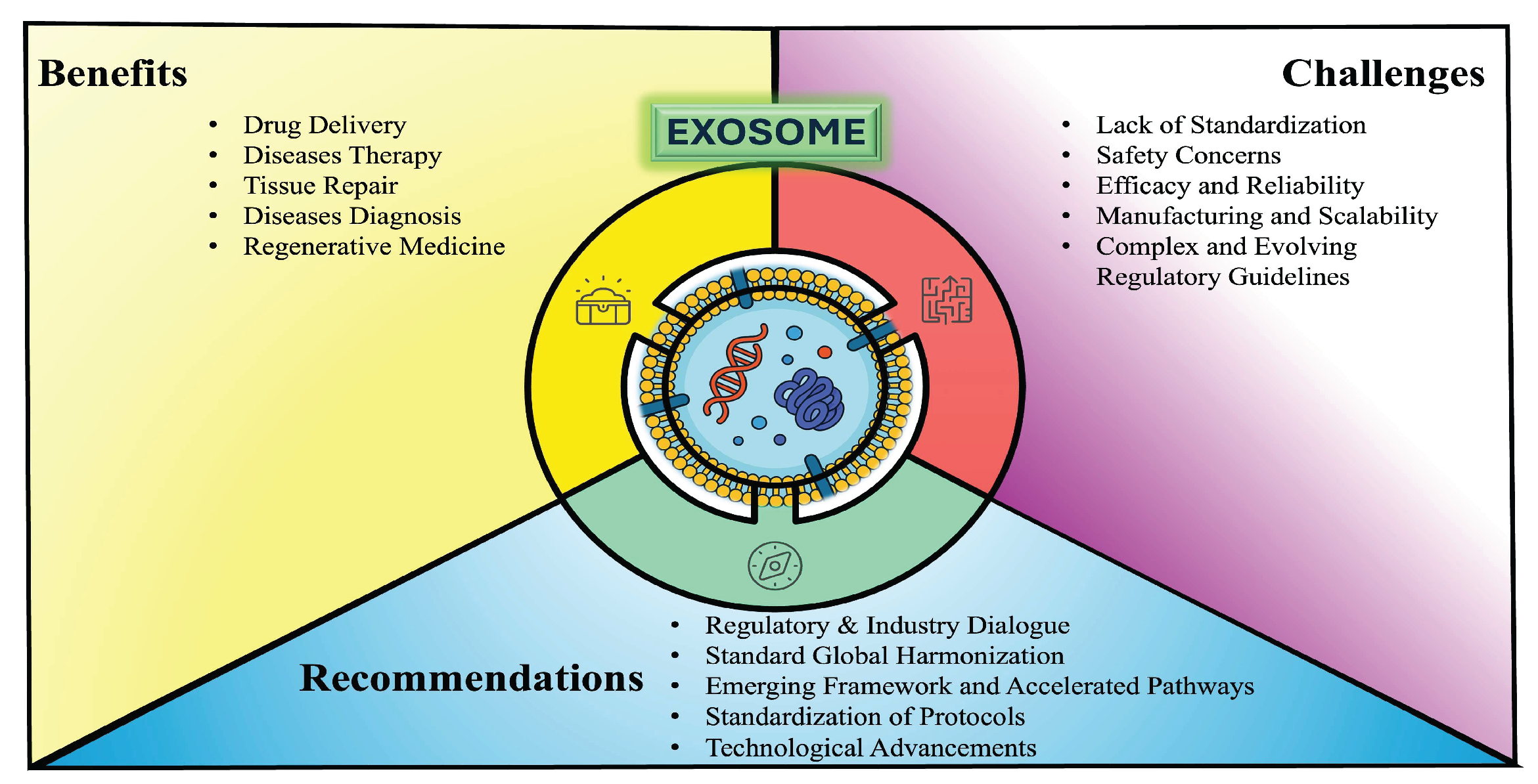

Figure 1.

Graphical Abstract. This conceptual framework explains the exosome-based therapeutics landscape by highlighting its inherent benefits—efficient cargo delivery, biocompatibility, and precision targeting—while identifying key translational hurdles (standardization gaps, safety and efficacy concerns, manufacturing scale-up challenges, and regulatory complexity) and proposing strategic measures—global regulatory harmonization, accelerated approval pathways, standardized protocols, and ongoing technological innovation—to accelerate clinical integration.

1. Introduction

Exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles (EV), around 30–100 nm, released by diverse cell types, facilitating intercellular communication via the transfer of biomolecules [1-3]. Moreover, they are hypothesized to carry specific biomarkers reflective of their parent cells, thereby offering significant insights into disease states and potential therapeutic strategies [

4,

5]. Common markers used for exosome characterization include tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), Alix, TSG101, and heat shock proteins [

6]. Their roles in immune modulation, cell survival, and angiogenesis further underscore their importance in both physiological regulation and pathological conditions [

1,

7]. For instance, stem cell-derived exosomes have demonstrated the capacity to enhance tissue repair and regeneration through the modulation of inflammation and promotion of angiogenesis, which may benefit conditions such as diabetic complications and neurodegenerative disorders [

8,

9]. Furthermore, the natural capacity of exosomes to serve as drug carriers offers a biocompatible and targeted delivery system for therapeutics [

10,

11].

Emerging applications in therapeutics, diagnostics, and drug delivery have brought exosomes to the forefront of biomedical research. In the therapeutic sphere, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes are being actively investigated for their regenerative properties, especially in treating osteoarthritis and diabetic wounds [

12,

13]. Additionally, exosome-based immunotherapy is showing promise in cancer treatment, as it facilitates the targeted delivery of Immunotherapeutics while minimizing systemic toxicity [

14,

15]. As diagnostic tools, exosomes are considered promising candidates for liquid biopsies because they can mirror the pathological state of their originating tissue, thereby aiding in the early and non-invasive detection of cancers and other diseases [

5,

16]. Consequently, the potential for personalized medicine through tailored exosome therapies emphasizes the need for further research alongside careful ethical considerations.

The increased interest in both clinical translation and commercialization of exosome-based products is accompanied by several challenges. Regulatory bodies are anticipated to develop comprehensive guidelines addressing the characterization, safety, and efficacy of these products, which is vital for mitigating concerns related to immunogenicity and long-term effects [

12,

17]. Equally, preclinical and clinical trials are essential to validate therapeutic benefits and standardize production methods [

2,

17]. Challenges remain in managing exosome source variability, scaling up production, standardizing isolation and characterization protocols, and ensuring batch-to-batch consistency regarding safety and efficacy [

18]. Institutions like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have created frameworks highlighting the significance of adhering to good manufacturing practices and robust quality control standards. Concurrently, initiatives to commercialize products aim to improve the production yield, purity, and stability of exosome formulations. [

6,

18]. This robust growth trajectory in clinical development suggests that exosomes may soon play a central role in advancing precision medicine across diagnostics, therapeutics, and drug delivery [

18].

On a regional level, regulatory agencies have begun formulating guidelines specific to exosome-based products; however, discrepancies in classification and evaluation criteria still exist across jurisdictions. For example, while the FDA regulates exosomes under the Public Health Service Act, the EMA may classify certain exosome therapies as advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) depending on their content and function [

19]. Similarly, countries such as South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan have either implemented or are in the process of developing distinct regulatory strategies that reflect local scientific priorities and healthcare needs [

19]. This situation underscores the necessity for global regulatory harmonization aimed at streamlining clinical translation and commercialization processes while ensuring public health safety [

20]. Ultimately, establishing a unified global framework is crucial to maintain consistent manufacturing practices, protect patient safety, and facilitate the responsible translation of exosome research into clinical applications. Collaboration among regulatory agencies, researchers, and industry stakeholders will be key to fostering an innovative yet secure regulatory environment. Moreover, in this review, we provide a comprehensive analysis of the current global regulatory framework, challenges, compare regional differences, and propose strategies for achieving global harmonization.

2. Exosome-Based Therapeutics in Clinical Trials

Exosome-based therapeutics have attracted considerable scholarly attention in recent years, as illustrated by the growing number of clinical trials conducted across diverse medical fields. Their potential is being investigated for an array of conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory ailments. In particular, considerable focus has been placed on mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes due to their regenerative and immunomodulatory capabilities. For instance, clinical trials evaluating their application in COVID-19 pneumonia have provided evidence that these exosomes can expedite recovery through anti-inflammatory and reparative mechanisms [21-23]. Moreover, a clinical trial employing nebulization therapy with MSC-derived exosomes has been initiated to assess their benefits in treating severe pulmonary complications associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections [

24]. Similarly, studies examining MSC-derived exosomes for premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) have indicated promising therapeutic potential in reproductive health [

25,

26].

In the field of oncology, exosomes are under active investigation as vehicles for targeted drug delivery, particularly in RNA-based therapeutic applications. These vesicles may enhance treatment protocols and serve as carriers for interfering RNAs (siRNAs )and messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [

27,

28]. Contemporary clinical trials in pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma are evaluating exosome-based drug delivery systems that aim to increase cytotoxicity against tumors while reducing systemic toxicity [

29]. Furthermore, exosome-based cancer vaccines are being explored, capitalizing on the inherent ability of these vesicles to stimulate immune responses against specific malignancies [

30,

31]. In addition, subsequent studies have broadened the scope of exosome applications; for example, in the context of neuroprotection following ischemic strokes, several clinical trials suggest that exosomes may facilitate recovery through neuroplastic mechanisms [

32,

33]. Preliminary evidence in gastrointestinal diseases further indicates that exosome-based therapies may modulate immune responses and promote tissue repair in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease [

18,

34].

Despite these encouraging advancements, the translation of exosome research into clinical applications faces numerous regulatory challenges. The intrinsic complexity of exosomes as biological entities mandates the establishment of stringent frameworks to ensure their safe and effective use as therapeutic agents. Accordingly, the following discussion examines the principal regulatory challenges currently confronting exosome research, particularly in the context of clinical trials and the development of exosome-based therapies.

First, a prominent challenge pertains to the classification of exosomes within existing regulatory frameworks. As exosomes may be categorized as either biological products or drug delivery systems, their regulatory oversight becomes inherently complex [

13,

35]. Considering that exosome therapies are relatively novel, current regulatory guidelines may not fully address the unique characteristics and functionalities of these vesicles. Regulatory agencies, such as the U.S. FDA, are still in the process of developing the requisite policies to govern the production, clinical trials, and therapeutic applications of exosomes [

13,

17]. Furthermore, the absence of universally accepted protocols for exosome isolation and characterization further compounds these regulatory hurdles [

35,

36].

Moreover, the regulatory approval process demands an in-depth understanding of both the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of exosomal therapies [

17] . This process necessitates rigorous preclinical and clinical evaluations to establish safety and effectiveness, frequently involving extensive data collection regarding the behavior and effects of exosomes in varied biological environments. The challenge is further compounded by the need for researchers to delineate the intricate pathways of exosome biogenesis, uptake, and functionality to provide compelling evidence for regulatory submissions [

17]. As highlighted in reviews focusing on exosome dynamics, these factors must be systematically characterized to facilitate the seamless translation of exosome-based therapies into clinical practice [

35,

37].

In addition, issues related to the standardization of exosome preparations continue to impede their clinical application. Given that individual studies often employ different methods for exosome isolation, variability in exosomal composition and functional outcomes is observed [

18]. Consequently, regulatory agencies face significant difficulties in evaluating the consistency and reliability of exosome-based products [

36,

38]. The lack of standardized quality controls may lead to substantial variances in therapeutic outcomes, thereby posing a barrier to the recognition of exosome-based interventions as established clinical therapies.

Further complicating the regulatory landscape is the dynamic nature of exosome content, which can be influenced by factors such as cell type, disease state, and environmental conditions [

39]. Accordingly, regulatory frameworks must be sufficiently adaptable to accommodate these variables and accurately capture the biological intricacies of exosomes as therapeutic agents. This evolving scenario necessitates continuous dialogue between researchers and regulatory authorities to formulate guidelines that foster innovation while ensuring patient safety [

36,

40].

In summary, although exosome research holds considerable promise for advancing therapeutic strategies, it is encumbered by regulatory challenges arising from classification uncertainties, the imperative for robust pharmacological data, and the complexities of standardization. Overcoming these obstacles will be pivotal in the successful integration of exosome-based therapies into clinical practice, an endeavor that will require concerted collaborative efforts among stakeholders in the biomedical field [

17,

35,

37]. (

Figure 2).

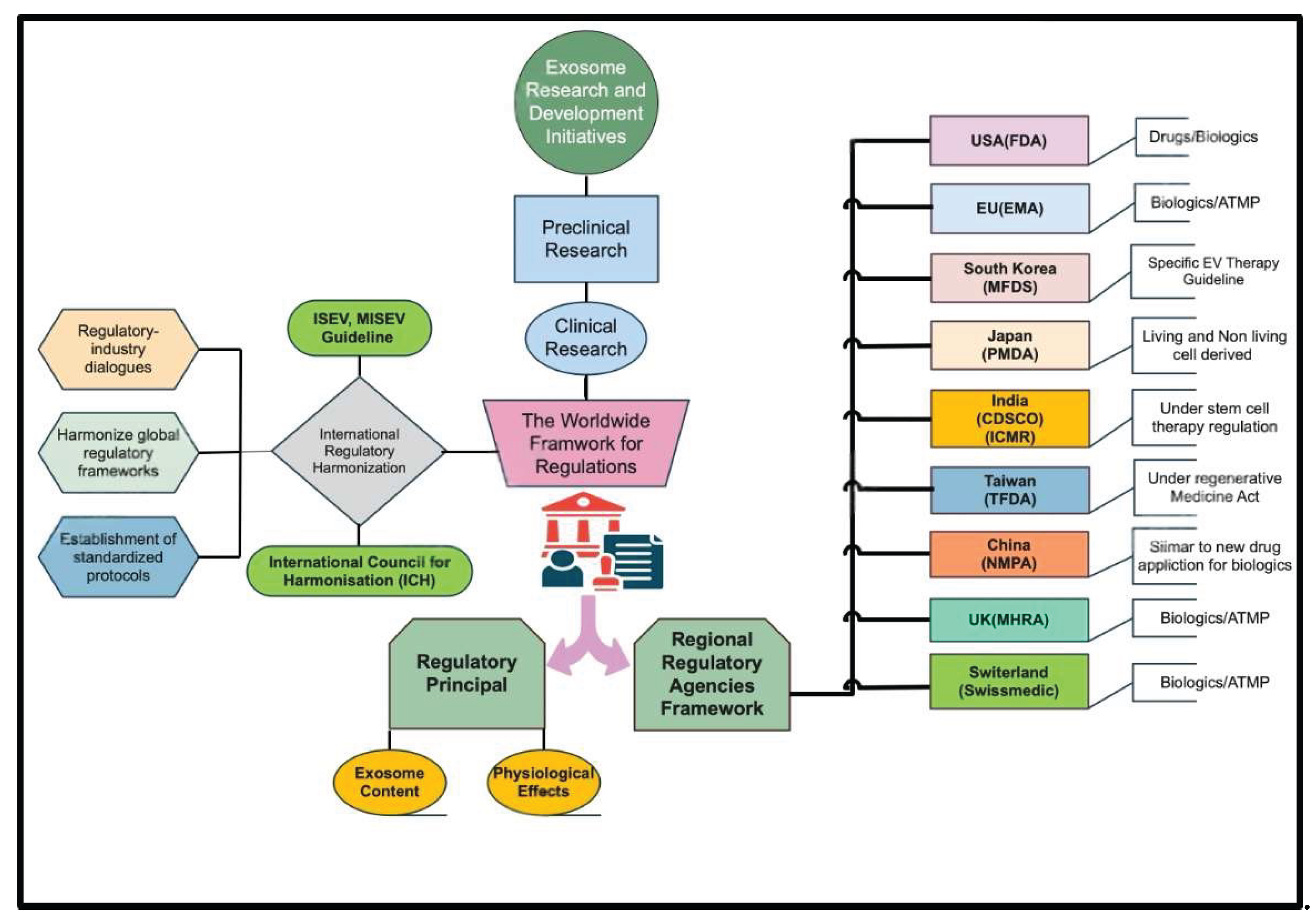

3. Global Regulatory Frameworks for Exosomes

The global regulatory frameworks that govern the development and approval of exosome-based therapies are both intricate and regionally disparate (

Table 1), thereby influencing their clinical translation. Consequently, exosomes—as biologic medicines—face significant regulatory hurdles owing to their unique intracellular mechanisms and heterogeneous manufacturing techniques, which impede efforts at standardization. Globally, regulation generally hinges on two primary strategies: firstly, evaluation of the molecular and physiological effects of exosomal cargo; and secondly, assessment based on the methods of exosome acquisition and production [

17]. Under the first strategy, regulators determine whether bioactive components—such as functional RNAs or modified proteins—elicit therapeutic or diagnostic effects, thus classifying the product as a biological drug or an ATMP [

17]. In contrast, the second approach—common in certain Asian jurisdictions—categorizes exosome-based products according to their provenance (e.g., isolation from living cells, bioengineering, or derivation from nonliving materials), irrespective of cargo composition [

17]. Furthermore, exosome-based therapies are typically regulated akin to biological medicinal products, requiring in-depth characterization of molecular composition, structure, pharmacokinetics, and therapeutic efficacy, although these requirements continue to challenge regulatory agencies [

17].

Regional disparities further shape approval pathways (

Table 1). For instance, in Europe, exosomes are not considered ATMPs unless incorporated into gene therapies, a classification that directly affects regulatory strategy, jurisdictional oversight, and development timelines [

41]. Although the EU’s ATMP Regulation provides a harmonized framework for regenerative medicine, it has been criticized for not keeping pace with rapid technological advances [

42]. In the United States, regulatory responsibilities are shared between the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), with oversight determined by the specific application of the exosome product [

41]. Meanwhile, Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (PMD) Act and the Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine (ASRM) permit conditional, time-limited marketing authorizations, thereby expediting development while safeguarding patient welfare [

43]. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) emphasizes the necessity of collaboration among researchers, clinicians, and regulatory authorities to ensure the safe and effective clinical translation of exosome-based therapies [

44]. Despite the expanding promise of exosomes in regenerative medicine, oncology, and targeted drug delivery, critical obstacles—particularly those relating to isolation, purification, and regulatory standardization—remain[

45]. Overall, while significant progress has been made, regulatory frameworks must evolve further to address the unique challenges posed by exosome-based therapies and to facilitate their clinical application [

46,

47].

Overall, significant progress has been made in recognizing the potential of exosome-based therapies, yet numerous challenges remain in their regulatory oversight. The development of comprehensive guidelines addressing the isolation, characterization, and therapeutic efficacy of exosomes, along with international regulatory harmonization, will be crucial in enabling these innovative therapies to fulfill their promise in clinical settings.

Table 1.

Regulatory frameworks for exosome-based therapeutics across key jurisdictions.

Table 1.

Regulatory frameworks for exosome-based therapeutics across key jurisdictions.

| Region/Country |

Regulatory Authority |

Regulatory Status & Classification |

Classification Focus |

| United States |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

|

Exosomes are regulated as biologics/drugs and subject to premarket review; no products approved to date |

Content characterization; physiological function |

| European Union |

European Medicines Agency (EMA)

|

Exosomes fall under the Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP) regulation; classification criteria remain unclear |

Cargo composition; functional (RNA) content |

| Japan |

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) |

Dedicated subcommittees evaluate safety and quality of extracellular vesicle therapies |

Source of manufacture; living vs. nonliving |

| South Korea |

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) |

Published specific guidelines for extracellular vesicle–based therapies |

Manufacturing source |

| Taiwan |

Taiwan Food and Drug Administration (TFDA) |

Regenerative Medicine Development Act encompasses exosomes; cosmetic use explicitly permitted |

Manufacturing source; regenerative applications |

| India |

Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) & ICMR |

Stem-cell therapies regulated; no exosome-specific therapeutic guidelines established |

Nascent and evolving |

| Australia |

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) |

Stem-cell and tissue therapies regulated since 2019; no dedicated exosome guidelines |

Nascent and evolving |

| China |

National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) |

Exosome products regulated under the same framework as biological new drug applications |

Nascent and evolving |

| Switzerland |

Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic) |

Exosome-derived products classified as biological medicines; may be regulated as ATMPs when cells are extensively manipulated |

Nascent and evolving |

| United Kingdom |

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) |

Exosome therapies classified as biological medicinal products; ATMP framework applies if derived from manipulated cells |

Nascent and evolving |

Table 1. Overview of regional regulatory frameworks for exosome-based therapeutics, detailing

the responsible authorities, classification status, pathways, and principal evaluation criteria across

key jurisdictions

3.1. United States Regulatory Framework

In the United States, products based on exosomes for treating or preventing diseases are categorized as drugs and biologics, falling under the regulatory frameworks of the Public Health Service (PHS) Act Section 351 and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act [

17,

41]. Accordingly, sponsors are required to submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application and, following successful clinical trials, file a Biologics License Application (BLA) with the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER)[

41]. Furthermore, the FDA has consistently issued public safety notices and undertaken enforcement actions against the marketing of unapproved exosome products, thereby highlighting regulatory gaps and the urgent need for comprehensive guidelines [

17]. To ensure patient safety, the FDA has also released consumer alerts stating that no exosome-based product is currently approved and cautioning against clinics that promote unapproved “stem cell” and exosome interventions [

42]. Given the intricate nature, heterogeneity, and incomplete elucidation of the mechanisms underlying exosome products, the FDA aligns its regulatory oversight with the stringent requirements applicable to biologic drugs, including adherence to current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) standards for quality control, safety testing, and consistency in manufacturing [

17]. This rigorous regulatory stance reflects the agency’s commitment to balancing innovative advancements in regenerative medicine with patient safety, emphasizing the critical need for robust clinical evidence and standardized production processes before marketing authorization can be granted [

41].

In summary, although exosome therapies hold immense promise, the regulatory framework is still evolving. There is a clear need for adaptive and expansive guidelines to facilitate the safe transition of these therapies from the research phase to clinical practice, ensuring that their potential benefits are effectively realized [

13,

35].

3.2. European Union Regulatory Framework

The European Union (EU) predominantly classifies exosome-based therapies as biological medicinal products, subjecting them to strict regulatory oversight similar to that applied to advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) when their contents have a direct impact on physiological functions [

17]. According to the European Directive (Directive 2001/83/EC) and Regulation 1394/2007/EC, exosomes that are either directly purified from cells or contain functionally translated RNA with expected therapeutic effects are categorized as ATMPs. Consequently, these products are reviewed by the Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) at the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which assesses their quality, safety, and efficacy prior to granting marketing authorization [

17]. Moreover, products that encapsulate recombinant nucleic acids or gene-modulating components may be regulated as gene therapy medicinal products under this framework [

17].

The classification primarily depends on whether the exosome composition exerts a specific mechanism of action affecting physiological functions, distinguishing them from ordinary biological specimens [

17]. In addition, quality control, manufacturing processes, and clinical evaluations are required to meet Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and Chemical, Manufacturing, and Control (CMC) regulations, thus ensuring consistent pharmaceutical quality throughout the product lifecycle [

17]. Nevertheless, the intrinsic heterogeneity and batch-to-batch variability of exosomes continue to pose significant challenges for standardization and regulatory harmonization [

17].

Notably, the use of human-derived exosomes in cosmetic products is prohibited under EU Cosmetic Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 due to safety concerns, such as risks of contamination and immunogenicity [

43]. Therefore, regulatory pathways for exosome-based therapies focus primarily on therapeutic applications rather than cosmetic uses [

43].

Furthermore, the EMA actively issues scientific recommendations and guidelines to promote the safe clinical translation and commercialization of exosome-based therapeutics. These recommendations emphasize the necessity for clear product characterization, a comprehensive mechanistic understanding, and rigorous clinical evaluation to safeguard patient safety while fostering innovation in this emerging field [

17].

In summary, the EU regulatory framework mandates that exosome therapies be managed as sophisticated biological medicinal products—often as ATMPs—with oversight by the EMA’s CAT committee, strict adherence to GMP, and comprehensive clinical evaluations to ensure safety and efficacy prior to market authorization. Although this framework accounts for the unique nature of exosomes, it also underscores ongoing challenges in quality control and standardization that will require continuous refinement [

17,

43].

3.3. Japan Regulatory Framework

In Japan, the regulatory framework for exosome therapies is defined by a dual-track system designed to expedite the availability of regenerative medicinal products while ensuring patient safety. This system, influenced by the Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices, and Other Therapeutic Products Act (PMD Act) and the Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine (ASRM) enacted in November 2014, promotes innovative therapies by allowing conditional and time-limited approvals for regenerative products, including exosome therapies [44-46].

Nevertheless, Japan currently does not have specific legislation or detailed regulations that directly address EVs, such as exosomes, beyond the general oversight provided by the Medical Practitioners' Act and the Medical Care Act [

47]. Consequently, exosome-based therapies are often utilized in clinical settings without comprehensive scientific validation or regulatory scrutiny, resulting in their widespread application even in the absence of robust efficacy or safety data. Moreover, the lack of mandated tracking and reporting mechanisms for adverse events further complicates patient safety oversight and emphasizes the urgent need for clearer regulations [

48].

Although the dual-track system is intended to balance patient access with safety by employing risk-based classifications and certified review committees, the inherent variability of exosomes, stemming from differences in origin, culture conditions, and manufacturing methods, poses significant challenges to standardization and quality control that current cell therapy frameworks do not fully address [

17]. Consequently, there is a growing call within the scientific and regulatory communities for dedicated guidelines and regulatory measures specifically tailored to exosome therapies to ensure consistent product quality and patient protection while still promoting innovation [

17].

In summary, while exosome therapies in Japan are currently managed as biologic medicinal products under existing pharmaceutical laws, the absence of exosome-specific legislation and comprehensive safety monitoring has led to regulatory ambiguity and potential patient risks. Therefore, enhanced regulatory oversight, clearer classification guidelines, and improved adverse event tracking are imperative to support the safe clinical development and application of exosome-based therapies in Japan [

17]

3.4. South Korea Regulatory Framework

South Korea's oversight of exosome therapies is primarily determined by the "Act on the Safety of and Support for Advanced Regenerative Medicine and Advanced Biological Products," enacted in August 2019 and set to take effect in February 2025 [

49]. This legislation is designed to safeguard patient safety and ensure the quality of advanced regenerative treatments, including exosome-based therapies, by establishing stringent oversight over their development, manufacturing, and clinical application [

17]. n this framework, both the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) and the National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation (NIFDS) play pivotal roles by issuing detailed guidelines that cover quality standards as well as nonclinical and clinical evaluation criteria specifically for extracellular vesicle therapeutics [

17]. Moreover, exosome products are classified as biologics and regulated under standards similar to those for cellular and gene therapies, although with tailored requirements that address their unique characteristics [

17]. The MFDS enforces compliance with GMP specialized for advanced biopharmaceuticals, thereby emphasizing rigorous quality control and safety protocols to tackle challenges such as exosome heterogeneity and production variability [

17]. Additionally, the regulatory framework facilitates patient access by allowing controlled clinical research pathways, which are authorized by designated institutions and overseen by a national review committee composed of scientific and medical experts [

49]. Notably, South Korea’s approach distinguishes itself by excluding minimally manipulated cells, such as cord blood, from this advanced regenerative medicine pathway—a distinction that sets it apart from other international frameworks [

49]. Furthermore, recent regulatory milestones, such as the MFDS’s authorization of S&E Bio’s Phase 1b clinical trial for an exosome-based stroke therapy, underscore the advancements enabled by this landscape [

50]. Collectively, South Korea’s regulatory structure embodies a comprehensive, science-driven approach that effectively balances the promotion of innovation with patient safety, thereby positioning the country as a leader in the global development and commercialization of exosome therapeutics [

17].

3.5. Taiwan Regulatory Framework

In Taiwan, exosomes are recognized as cell-derived products within the realm of regenerative medicine, as explicitly defined by the recently enacted Regenerative Medicine Act (RMA) [

46]. The RMA encompasses genes, cells, and their derivatives, thereby including exosomes as regulated biological products. This systemic approach draws inspiration from regulatory models in Japan and South Korea while being tailored to Taiwan’s unique biomedical landscape [

46]. Consequently, exosome therapies are categorized as biologic medicinal products and must adhere to stringent quality and safety standards similar to those applicable to cell and gene therapies [

17].

The primary regulatory authority overseeing exosome therapy in Taiwan is the Taiwan Food and Drug Administration (TFDA), supported by the Center for Drug Evaluation [

51]. The TFDA is charged with ensuring compliance with Good Tissue Practice (GTP), GMP, and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standards throughout the entire lifecycle of exosome products—from raw material procurement to clinical application [

51]. Simultaneously, the CDE provides technical evaluations and detailed scientific assessments during the review of submission dossiers for both regenerative medical technologies and preparations, which include exosome-based therapeutics [

52].

Taiwan’s regulatory framework is dual-faceted, governing both regenerative medical technology—covering clinical use protocols—and regenerative medical preparations, which encompass biologic drug products such as engineered exosomes [

52,

53]. For regenerative medical preparations, manufacturers must comply with site registration requirements and adhere to GMP standards, which may involve foreign inspections or Plant Master File (PMF) reviews, depending on the product’s country of origin [

52]. Moreover, the development and manufacturing processes for exosome therapies must overcome challenges related to their heterogeneity and instability by standardizing raw materials, controlling cultivation environments, optimizing purification procedures, and ensuring thorough characterization of their physicochemical and biological properties [

17]. To this end, Taiwanese guidelines have incorporated international recommendations, such as the ISEV, Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) 2018, to standardize quality control and characterization practices [

17].

Exosome therapies are subject to a phased approval process in which clinical trial applications must comply with the Human Trials Management Regulation, in alignment with international GCP standards [

54]. Products that involve exosomes with minimal manipulation or systemic effects may qualify for expedited or conditional approval pathways, analogous to the “fast track” processes available for certain cell therapies in Taiwan [

52] . However, a rigorous demonstration of pharmacokinetics, mechanisms of action, safety, and efficacy remain mandatory [

17]. Additionally, the TFDA conducts post-marketing surveillance to track adverse events and treatment efficacy, which is critical due to the risks linked with biologics, including immunogenicity and off-target effects. All licensed institutions are required to report adverse drug reactions and submit annual summary reports. Furthermore, Taiwan’s proactive regulatory environment and supportive government initiatives have spurred local industry participation and clinical research in exosome therapy. For instance, ExoOne Bio has obtained approval to use human-derived exosomes as cosmetic ingredients following a rigorous review process conducted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the TFDA [

55]. In summary, Taiwan’s regulatory framework for exosome therapy reflects its commitment to advancing innovative medical treatments through a dual-framework approach that addresses significant scientific and regulatory challenges. As the field progresses, further regulatory adaptations will be essential to ensure the successful clinical implementation of exosome-based therapies.

3.6. Chinese Regulatory Framework

Exosome therapy represents an emerging frontier in biomedical science in China, attracting significant attention and prompting the development of a specialized regulatory framework to manage both its research and commercialization. Since 2017, China has implemented a dual-track regulatory system that distinguishes between pathways for investigator-initiated studies and commercial clinical trials involving cell-based therapies, including exosome products. This bifurcated system establishes clear and distinct requirements that facilitate the progression from research to market approval, thereby enhancing regulatory clarity and oversight for these innovative treatments[

56].

At the core of this framework is the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), which serves as the primary authority overseeing exosome therapies, particularly those classified as cell therapy products. The NMPA is responsible for managing clinical trial approvals, enforcing quality control standards, and granting market authorization, all while ensuring that safety and efficacy criteria are rigorously evaluated before any therapeutic product reaches patients [

56]. Complementing these measures, China has adopted GMP that conforms to international guidelines, such as PIC/S GMP. These standards are critical for ensuring quality assurance throughout the production and distribution stages, emphasizing standardized production environments, consistent product quality, and full traceability from raw materials to final products—factors that are essential in addressing the inherent heterogeneity of exosome preparations [

56].

Moreover, government policies play a pivotal role in bolstering the exosome therapy sector in China. Strategic initiatives like the "Healthy China 2030" plan allocate substantial funding towards precision medicine and regenerative therapies, thereby indirectly accelerating innovation and the expansion of exosome research and applications [

57]. Additionally, regulatory efforts have yielded fast-track approvals for over 40 exosome-based therapies as of 2023, highlighting a proactive stance aimed at expediting the availability of promising treatments while maintaining rigorous oversight [

57]. Nonetheless, significant challenges remain. The complexity of exosomes’ molecular composition and their dynamic biological functions continue to impede full standardization. In response, China has adopted a cautious regulatory approach that requires comprehensive preclinical and clinical data to ensure reliable therapeutic outcomes, in line with international standards [

56].

In conclusion, China’s regulatory framework for exosome therapy is evolving in step with technological innovations and emerging regulatory demands. With its emphasis on safety, efficacy, and international alignment, the framework reflects a growing recognition of exosome therapy as a key element in future therapeutic strategies[

56,

57].

3.7. Indian Regulatory Framework

In India, the principal regulatory body for the approval, clinical trial conduct, and commercialization of exosome-based therapies is the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), operating under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) [

58]. The Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI), who heads CDSCO, serves as the Central Licensing Authority responsible for granting permissions related to clinical trials and marketing authorization for new drugs, including biological products such as exosome therapeutics [

59]. Accordingly, the CDSCO’s responsibilities include the approval of investigational new drugs, oversight of clinical trial protocols, and the enforcement of drug standards to ensure product safety and efficacy [

58].

In addition, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) plays a pivotal role by issuing national guidelines focused on ethical conduct, research approval, and the monitoring of stem cell and related advanced therapies. Particularly, the ICMR's 2017 guidelines mandate that stem cell interventions, including exosome applications, must occur within sanctioned clinical trials. These trials require stringent oversight from Institutional Committees for Stem Cell Research (IC-SCR) and Institutional Ethics Committees (IEC). [

60].

Although a dedicated regulatory framework exclusively for exosome therapies has yet to be finalized, their governance in India currently falls under existing frameworks for biological products, stem cell research, and regenerative medicine as stipulated by the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, and its accompanying rules [

61]. Under these regulations, exosome-based products are treated as biological medicinal products that must comply with GMP and meet quality standards established by CDSCO [

61]. Moreover, in 2019 the Government of India issued national guidelines on gene therapy product development and clinical trials, which, although primarily targeting gene therapy, provide procedural references applicable to advanced biotherapeutics and new pharmaceutical products, including exosomes [

19] Consequently, clinical trials involving exosome therapies must obtain prior approval from CDSCO (via the DCGI) and the respective registered Ethics Committees, adhering to the comprehensive provisions of the New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules (2019). These rules require the detailed submission of data on pharmacokinetics, safety, immunogenicity, and manufacturing quality before initiating first-in-human trials [

59]. Furthermore, CDSCO mandates the registration and continuous monitoring of Ethics Committees to ensure ongoing ethical oversight throughout clinical trials involving novel biologics and cell-based therapies. In addition, each trial site must secure approval from a registered Ethics Committee to provide multi-tiered review that safeguards participant rights and safety [

59].

However, India's current regulatory framework for exosome therapy faces several challenges. Notably, the absence of dedicated, explicit guidelines that comprehensively address the unique characteristics of exosome products, including considerations related to donor eligibility, purification standards, potency assays, and long-term safety monitoring, has resulted in regulatory ambiguity. This lack of a specific drug classification for exosome products further complicates both clinical translation and commercial approvals [

19].

Therefore, to ensure the safe, effective, and ethical use of exosome therapies, the Indian regulatory system requires specific amendments and robust policy development. These should include the establishment of dedicated regulatory guidelines for the manufacture, quality control, clinical trials, and post-marketing surveillance tailored to the distinctive nature of exosome products [

19].

3.8. United Kingdom Regulatory Framework

The regulatory framework for exosome therapy in the United Kingdom is notably stringent, reflecting the uncertainties and potential risks inherent to these emerging biological products. Exosomes, broadly classified as EVs, are considered biological medicinal products and are consequently regulated as Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) [

62]. This status requires that their quality, safety, and efficacy undergo rigorous evaluation prior to market authorization, in accordance with both European Union and international standards for cell and gene therapies [

63]. Currently, no exosome-based therapies have received approval for clinical or cosmetic use within the UK, largely due to insufficient clinical trial data to substantiate their safety and effectiveness [

64]. The MHRA has expressly stated that exosome injections, particularly those used for aesthetic purposes like facial rejuvenation, cannot be legally administered until robust evidence from controlled studies is provided [

65]. As a result, clinics offering human-derived exosome products, such as those obtained from umbilical cord blood or mesenchymal stem cells, are in violation of UK regulations, a situation that has sparked calls for stricter enforcement measures to protect public health [

66]. Moreover, regulatory oversight includes strict adherence to GMP to ensure the purity, stability, and reproducibility of exosome preparations, as well as robust quality control to mitigate risks such as microbial contamination or viral transmission [

62]. UK authorities also follow guidance from organizations like the ISEV and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for standardization and monitoring of these products [

62]. Additionally, adverse events associated with unlicensed exosome therapies are required to be reported under established pharmacovigilance frameworks, although existing surveillance systems for these novel interventions still exhibit certain gaps [

41].

In summary, the UK's regulatory framework for exosome therapy is characterized by cautious and comprehensive control under the ATMP designation, emphasizing patient safety through stringent pre-market evaluation and the prohibition of unapproved clinical applications. This careful approach, while limiting immediate availability, is designed to prevent public exposure to unproven and potentially hazardous treatments until further scientific validation is achieved [

64].

3.9. Switzerland Regulatory Framework

In Switzerland, exosome therapy is primarily regulated by Swissmedic, the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products, which is responsible for authorizing and supervising therapeutic products to ensure their quality, safety, and efficacy [

67]. Exosome-based products are classified as Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) in accordance with European Union Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007, a framework with which Switzerland formally aligns to promote regulatory harmonization (© Copyright Swissmedic 2019, n.d.) [

68]. This alignment subjects exosome therapies to stringent oversight comparable to that applied to other cellular and gene therapies, employing a risk-based, case-by-case evaluation that accounts for the products' biological complexity [

67]. Moreover, the production, characterization, and quality control of these therapies adhere to international standards, such as those established by the ISEV, with particular emphasis on achieving the purity, potency, and reproducibility expected of clinical-grade exosomes [

62]. Although specific authorizations for exosome products by major regulatory bodies like the FDA remain absent, ongoing global clinical trials highlight both the promise and the regulatory challenges of exosome therapies—a development that Swissmedic actively monitors within its evolving framework [

62].

In conclusion, Switzerland’s regulatory environment for exosome therapy is marked by rigorous evaluation aligned with advanced therapy standards, prioritizing patient safety and product quality while fostering convergence with European Union regulations to support innovation in regenerative medicine [

67].

4. Regulatory Challenges in Clinical Trials and Exosome Research

The rapid evolution of exosome research has been accompanied by significant regulatory challenges that substantially affect their clinical use as therapeutic agents. One of the primary issues is the appropriate classification of exosomes within existing regulatory frameworks. Regulatory agencies—most notably the U.S. FDA—are still determining whether exosomes should be regarded as biological products, which would subject them to stringent biomanufacturing standards, or as drug delivery systems that might follow alternative approval routes [

13,

35]. Furthermore, a core regulatory challenge arises from the absence of standardized methodologies for exosome isolation, purification, and characterization. This methodological variability can lead to inconsistencies in exosome potency and therapeutic efficacy, thereby complicating compliance with regulatory requirements [

2,

69,

70]. Without established protocols to guarantee the purity and precise content of exosome preparations, concerns regarding patient safety and treatment effectiveness persist. In addition, regulatory bodies insist on a clear demonstration of the pharmacokinetics and biological activity of exosomal therapies; however, the complex nature of these vesicles renders such assessments particularly challenging [

71,

72].

Moreover, the scalability of exosome production remains unresolved. Current production techniques often fail to generate exosomes in commercially viable quantities while maintaining consistent quality [

18,

70,

73]. The requirement to adhere to GMP further complicates production, as many academic institutions and early-stage companies may not have the necessary infrastructure to meet these standards [

70,

74]. Consequently, the transition from preclinical investigations to clinical applications critically depends on the development of robust production and quality assurance protocols that satisfy regulatory expectations [

37,

70,

75]. Additionally, the intrinsic variability in exosome composition—stemming from differences in cellular origin, cell passage number, culture mediums, and environmental conditions—challenges conventional diagnostic and therapeutic evaluations and underscores the need for specific regulatory guidelines tailored to exosome products [

17].

Furthermore, an incomplete understanding of the physiological mechanisms underlying exosome therapeutic effects, particularly regarding their pharmacokinetics, cellular uptake, and mechanism of action (MOA), impedes the establishment of reliable potency assays and comprehensive safety profiles. This lack of mechanistic clarity further complicates regulatory approval and the assurance of consistent therapeutic outcomes [

2,

74]. Thus, rigorous validation and standardization of exosomal products are essential for advancing this field [

18,

35,

37].

In summary, navigating the regulatory landscape for exosome-based therapies requires the development of standardized protocols for isolation and characterization, scalable manufacturing processes, and comprehensive regulatory compliance. Addressing these multifaceted challenges is critical to unlocking the clinical potential of exosome therapeutics [

17,

76,

77].

5. Harmonization of the exosome regulatory framework

International harmonization of the exosome regulatory framework presents both a significant challenge and a promising opportunity in biomedicine. The inherent complexity of exosome biology means that their development and manufacturing processes encounter unique regulatory obstacles. Globally, differing regulatory approaches result in variations in how exosomes are characterized and evaluated for clinical use. Wang and colleagues underscore that achieving harmonization across these practices is crucial for ensuring safety and efficacy across diverse jurisdictions

Table 1 [

17]. One promising strategy to advance harmonization is the establishment of international cooperation frameworks. Current discussions advocate a dual approach: one that focuses on the composition and biological effects of exosomes, and another that evaluates their therapeutic implications [

17]. In support of this, the ISEV has called for the standardization of methodologies to assess exosome products, thereby promoting a unified regulatory approach that spans both geographical and institutional boundaries [

78]

Figure 3. Such collaborative efforts are essential, as inconsistent regulations can impede innovation and delay the translation of research into clinical applications. Moreover, international bodies such as the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) play a pivotal role in ligning regulatory standards for biopharmaceuticals, including exosomes. Their established frameworks have fostered regulatory convergence across regions, facilitating smoother collaborative efforts in drug development and approval processes [

79]. Additionally, recent initiatives emphasize sharing best practices and aligning preclinical and clinical evaluation standards to further bolster regulatory coherence in exosome therapeutics [

80,

81]. Despite these advancements, notable challenges remain. For example, incomplete harmonization—illustrated by experiences in the stem cell sector—can lead to regulatory fragmentation, thereby compromising global assessments of efficacy and safety [

82]. Furthermore, stakeholders must navigate complex ethical, legal, and social considerations as they work toward a more cohesive regulatory stance on exosomes [

83]. Addressing these multifaceted issues necessitates an ongoing dialogue among regulatory authorities, scientists, and healthcare providers to develop robust standards that support innovation while safeguarding public health

Figure 3.

In conclusion, progress toward harmonizing the regulatory framework for exosome therapies is a multifaceted journey marked by both significant achievements and persistent challenges. Continued dialogue and alignment among global regulatory agencies are essential for establishing mutually recognized standards, streamlining approval pathways and methodologies, enhancing regulatory efficiency, fostering trust, and ultimately improving patient access to these innovative therapies[

17,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

6. Future Directions, Opportunities, and Policy Implications

As recognition of exosomes' therapeutic potential grows, their regulatory framework continues to evolve. Given the inherent complexity of exosome biology and their diverse clinical applications, it is imperative to develop comprehensive regulatory guidelines that ensure both safety and efficacy. Currently, existing regulations often lack the necessary specificity regarding exosomes, thereby complicating their development and approval. Accordingly, efforts should concentrate on clearly defining exosomes within regulatory frameworks—whether as biological products or drug delivery systems—especially in light of their complex biogenesis and biocompatibility [

17,

35,

41]. Such clarity will enable researchers and companies to navigate the regulatory landscape more effectively.

Moreover, advancements in exosome isolation and characterization techniques are expected to play a crucial role in future research and development. The improvement and standardization of these methods will enhance the reproducibility and purity of exosome preparations, thereby facilitating more reliable clinical applications [

36,

84]. In addition, integrating artificial intelligence and machine learning into data analysis could streamline the biomarker identification process, thus accelerating the translation from basic research to clinical trials [

85].

Exosomes also present novel therapeutic opportunities, particularly in the field of personalized medicine. Their capacity to transport nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids specific to the originating cell allows for targeted therapies in diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic conditions [

37,

86]. Furthermore, exosome-mediated drug delivery systems offer the potential to improve treatment efficiency while mitigating the adverse effects commonly associated with conventional therapies [

87]. Global collaboration is another vital avenue for optimizing both regulatory and investigational processes in exosome research. Initiatives by international bodies such as the ISEVare essential for fostering a unified approach to developing and implementing exosome therapies [

88]. Harmonizing regulatory standards across countries could facilitate a smoother transition of exosome-based products into clinical practice, thereby accelerating medical innovation.

Given the rapid advancements in this field, regulatory frameworks must adapt accordingly. Policymakers need to ensure that regulations are both comprehensive and flexible enough to accommodate ongoing scientific and technological progress. This includes recognizing exosomes as pivotal components of biologics, which necessitates stricter guidelines concerning their composition, manufacturing, and clinical applications [

89].Additionally, regulatory bodies should consider establishing fast-track pathways for promising exosome therapies similar to accelerated approval processes used for other innovative treatments, to expedite patient access while maintaining rigorous safety and efficacy standards [

90]. Complementary policy efforts should also focus on incentivizing research and development in exosome technology through targeted grants and funding, thereby empowering emerging scientists and organizations to contribute meaningfully to this field [

91,

92].

7. Conclusions

In summary, exosome-based therapies hold substantial promise, driven by ongoing scientific advances and an evolving regulatory environment. Nevertheless, the global regulatory landscape is filled with significant challenges, including the absence of harmonized international guidelines, technical obstacles in characterization and manufacturing, and unresolved concerns regarding safety and efficacy. Consequently, the development of clear and robust policies is expected to streamline the advancement process and promote collaboration among researchers, clinicians, and industry stakeholders, ultimately enabling safe and effective applications across diverse medical fields. By tackling regulatory voids and adopting technological developments, exosomal therapeutics can foster improved patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.V.; resources, S.A.; data curation, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.V.; writing—review and editing, N.V. and S.A.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, N.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATMP |

Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products |

| CBER |

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research |

| CDER |

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research |

| ISEV |

International Society for Extracellular |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| GMP |

Good Manufacturing Practices |

| MSC |

Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| PMD |

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices |

| ASRM |

Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine |

| EMA |

European Medicines Agency |

| PMDA |

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency |

| MFDS |

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety |

| TFDA |

Taiwan Food and Drug Administration |

| CDSCO |

Central Drugs Standard Control Organization |

| ICMR |

Indian Council of Medical Research |

| TGA |

Therapeutic Goods Administration |

| NMPA |

National Medical Products Administration |

| MHRA |

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency |

| PHS |

Public Health Service |

| IND |

Investigational New Drug |

| BLA |

Biologics License Application |

| CMC |

Chemical, Manufacturing, and Control |

| CAT |

Committee for Advanced Therapies |

| RMA |

Regenerative Medicine Act |

| GTP |

Good Tissue Practice |

| GCP |

Good Clinical Practice |

| MISEV |

Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles |

| EV |

Extracellular Vesicles |

| MOA |

Mechanism of Action |

| ICH |

International Conference on Harmonization |

References

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.W.A.; Chan, L.K.W.; Hung, L.C.; Lam, P.K.W.; Park, Y.; Yi, K.H. Clinical Applications of Exosomes: A Critical Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.H.; Hao, W.R.; Cheng, T.H. Stem cell exosomes: New hope for recovery from diabetic brain hemorrhage. World J Diabetes 2024, 15, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Xu, K.; Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zheng, S. Application of Exosomes as Liquid Biopsy in Clinical Diagnosis. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, J.; Feghhi, M.; Etemadi, T. A Review on Exosomes Application in Clinical Trials: Perspective, Questions, and Challenges. Cell Communication and Signaling 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Luh, F.; Ho, Y.S.; Yen, Y. Exosomes: a review of biologic function, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications, and clinical trials. J Biomed Sci 2024, 31, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhery, M.S.; Arif, T.; Mahmood, R.; Harris, D.T. Stem Cell-Based Acellular Therapy: Insight into Biogenesis, Bioengineering and Therapeutic Applications of Exosomes. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-H.; Lee, R.P.; Wu, W.T.; Chen, I.-H.; Yeh, K.T.; Wang, C.C. Advancing Osteoarthritis Treatment: The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Biomaterial Integration. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, W.C.; Kim, J.W.; Luo, J.Z.Q.; Luo, L. Stem cell-derived exosomes: a novel vector for tissue repair and diabetic therapy. J Mol Endocrinol 2017, 59, R155–R165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, R.; Dhar, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Nag, S.; Gorai, S.; Mukerjee, N.; Mukherjee, D.; Vatsa, R.; Jadhav, M.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Exosome-Based Smart Drug Delivery Tool for Cancer Theranostics. Acs Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2023, 9, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, T.; Zhang, X.; Bie, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Hakeem, A.; Hu, J.; Gan, L.; Santos, H.A.; et al. Tumor exosome-based nanoparticles are efficient drug carriers for chemotherapy. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, P.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, A.C.; Moreira, A.; Coelho, A.; Alvites, R.; Alves, N.; Geuna, S.; Mauricio, A.C. Advancements and Insights in Exosome-Based Therapies for Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Systematic Review (2018-June 2023). Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.H.; Lee, R.P.; Wu, W.T.; Chen, I.H.; Yeh, K.T.; Wang, C.C. Advancing Osteoarthritis Treatment: The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Biomaterial Integration. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zeng, S.; Gong, Z.; Yan, Y. Exosome-based immunotherapy: a promising approach for cancer treatment. Mol Cancer 2020, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Lei, C.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Wang, C.; Qian, K.; Li, T.; Shen, Y.; Fan, X.; Lin, F.; et al. CAR exosomes derived from effector CAR-T cells have potent antitumour effects and low toxicity. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xu, K.; Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zheng, S. Application of exosomes as liquid biopsy in clinical diagnosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.K.; Tsai, T.H.; Lee, C.H. Regulation of exosomes as biologic medicines: Regulatory challenges faced in exosome development and manufacturing processes. Clin Transl Sci 2024, 17, e13904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, J.; Feghhi, M.; Etemadi, T. A review on exosomes application in clinical trials: perspective, questions, and challenges. Cell Commun Signal 2022, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R. The Silent Battle for Extracellular Vesicle Regulation: Why Extracellular Vesicle Therapies Remain in Legal Grey Zones Worldwide. 2025.

- Research, C.f.D.E.a. International Regulatory Harmonization - FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.

- Chu, M.; Wang, H.; Bian, L.; Huang, J.; Wu, D.; Zhang, R.; Fei, F.; Chen, Y.; Xia, J. Nebulization Therapy with Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for COVID-19 Pneumonia. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2022, 18, 2152–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Upadhayay, V.K.; Tripathi, P.; Gautam, K.A.; Mishra, B.K.; Ahmad, J.; Jeong, G.B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Exhibit Promising Potential for Treating SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients. Cells 2021, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani-Ruttenstock, E.; Antounians, L.; Khalaj, K.; Figueira, R.L.; Zani, A. The Role of Exosomes in the Treatment, Prevention, Diagnosis, and Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2021, 31, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, M.; Wang, H.; Bian, L.; Huang, J.; Wu, D.; Fei, F.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Xia, J. Nebulization Therapy for COVID-19 Pneumonia With Embryonic Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Cetin, E.; Siblini, H.; Seok, J.; Alkelani, H.; Alkhrait, S.; Liakath Ali, F.; Mousaei Ghasroldasht, M.; Beckman, A.; Al-Hendy, A. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles to Treat PCOS. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.C.; Kang, I.; Yu, K.R. Therapeutic Features and Updated Clinical Trials of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Exosomes. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Tang, S.; Chai, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Recent advances in exosome-mediated nucleic acid delivery for cancer therapy. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, M.; Zheng, A. Exosome-Based Carrier for RNA Delivery: Progress and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, F.Y.; Tsai, C.H.; Chang, K.H.; Chang, Y.K.; Chou, R.H.; Liu, Y.J. Exosomes as promising frontier approaches in future cancer therapy. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025, 17, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, R.; Dhar, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Nag, S.; Gorai, S.; Mukerjee, N.; Mukherjee, D.; Vatsa, R.; Chandrakanth Jadhav, M.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Exosome-Based Smart Drug Delivery Tool for Cancer Theranostics. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, S. Clinical trial status of exosomes-based cancer theranostics. Clinical and Translational Discovery 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, G.Y. Therapeutic application of exosomes in ischaemic stroke. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2021, 6, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, W.; Ye, J.; Wang, Y. Potential Role of Exosomes in Ischemic Stroke Treatment. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghaei, K.; Tokhanbigli, S.; Asadzadeh, H.; Nmaki, S.; Reza Zali, M.; Hashemi, S.M. Exosomes as a novel cell-free therapeutic approach in gastrointestinal diseases. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 9910–9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Yadav, A.; Nandy, A.; Ghatak, S. Insight into the Functional Dynamics and Challenges of Exosomes in Pharmaceutical Innovation and Precision Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.W.A.; Chan, L.K.W.; Hung, L.C.; Phoebe, L.K.W.; Park, Y.; Yi, K.H. Clinical Applications of Exosomes: A Critical Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Corbett, A.L.; Taatizadeh, E.; Tasnim, N.; Little, J.P.; Garnis, C.; Daugaard, M.; Guns, E.; Hoorfar, M.; Li, I.T.S. Challenges and opportunities in exosome research-Perspectives from biology, engineering, and cancer therapy. APL Bioeng 2019, 3, 011503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K. Exosomes in perspective: a potential surrogate for stem cell therapy. Odontology 2019, 107, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Whiteside, T.L.; Reichert, T.E. Challenges in Exosome Isolation and Analysis in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Espinosa, I.; Serrato, J.A.; Ortiz-Quintero, B. The Role of Exosome-Derived microRNA on Lung Cancer Metastasis Progression. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaun, S. Exosomes as therapeutics and drug delivery vehicles: global regulatory perspectives. 2020, 6, 1561 - 1569, publication_type = article.

- Pawanbir, S.; Laure, B.-D.; Satya, P.D. Exploratory assessment of the current EU regulatory framework for development of advanced therapies. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology 2010, 16, 331–336, publication_type = article. [Google Scholar]

- Daisuke, M.; Teruhide, Y.; Takami, I.; Masakazu, H.; Kazuhiro, T.; Daisaku, S. Regulatory Frameworks for Gene and Cell Therapies in Japan. 2015; Volume 871, pp. 147 - 162, publication_type = incollection.

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Borger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; Del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials - an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 30087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakova, E.V.; Kim, M.S. Development and regulation of exosome-based therapy products. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2016, 8, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.H. Brief summary of the regulatory frameworks of regenerative medicine therapies. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1486812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, M.; Hatta, T.; Ikka, T.; Onishi, T. The urgent need for clear and concise regulations on exosome-based interventions. Stem Cell Reports 2024, 19, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (FDA), U.F.a.D.A. Consumer Alert on Regenerative Medicine Products Including Stem Cells and Exosomes. 2024.

- Clinic. Exosomes & EU Regulations. 2024, 2025.

- Lysaght, T. Accelerating regenerative medicine: the Japanese experiment in ethics and regulation. Regen Med 2017, 12, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Kawamoto, A. Regenerative medicine legislation in Japan for fast provision of cell therapy products. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016, 99, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, A.; Terai, S.; Horiguchi, I.; Homma, Y.; Saito, A.; Nakamura, N.; Sato, Y.; Ochiya, T.; Kino-Oka, M.; Working Group of Attitudes for, P.; et al. Basic points to consider regarding the preparation of extracellular vesicles and their clinical applications in Japan. Regen Ther 2022, 21, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CiRA. The need for regulatory measures regarding exosome therapy. Available online: https://www.cira.kyoto-u.ac.jp/e/pressrelease/news/241025-110000.html (accessed on 05/22/2025).

- Verter, F. South Korea expands access to regenerative medicine for serious illnesses. Available online: https://parentsguidecordblood.org/en/news/south-korea-expands-access-regenerative-medicine-serious-illnesses. (accessed on 05/20/2025).

- patsnap, S.b. S&E Bio Gains Korea's First Approval for Exosome Therapy Trial. Available online: https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/se-bio-gains-koreas-first-approval-for-exosome-therapy-trial (accessed on 05/20/2025).

- (2025), T.-A.o. Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies - TFDA. Available online: https://www.aabb.org/regulatory-and-advocacy/regulatory-affairs/regulatory-for-cellular-therapies/international-competent-authorities/taiwan#:~:text=In%20Taiwan%2C%20the%20Food,these%20regulations.&text=primary%20pieces%20of%20legislation,these%20regulations.&text=tissues%20must%20comply%20with,these%20regulations.&text=cellular%20therapy%20product.%20The,these%20regulations. (accessed on 03/19/2025).

- Bridge, P. Taiwan’s Regulatory Framework for Regenerative Medicine. Available online: https://www.pacificbridgemedical.com/uncategorized/taiwan-regulatory-framework-for-regenerative-medicine/ (accessed on 05/18/2025).

- Chao, W.Y.; Chang, Y.T.; Tsai, Y.T.; Huang, M.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Wu, M.M.; Chi, J.F.; Lin, C.L.; Cheng, H.F.; Wu, S.M. Update on Regulation of Regenerative Medicine in Taiwan. Adv Exp Med Biol 2023, 1430, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Cheng, H.F.; Yeh, M.K. Cell Therapy Regulation in Taiwan. Cell Transplant 2017, 26, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- healthcare, T. ExoOne has been granted approval by the Ministry of Health and Welfare to use human-derived exosomes as cosmetic ingredients, marking the first case in Taiwan. Available online: https://www.taiwan-healthcare.org/en/news-detail?id=0scizkifbr66p1ui (accessed on 03/18/2025).

- Bioscience, A. Navigating Cell & Gene Therapy Regulations in China – How does the dual-track system works? 2024.

- Ltd, A.I.P. Exosome research products market in China is rapidly expanding, driven by significant government funding, cutting-edge applications in diagnostics and drug delivery, and increasing collaborations among research institutions and biotech firms, positioning China as a leader in biomedical innovation. 2024.

- S, S.K.; Joga, R.; Srivastava, S.; Nagpal, K.; Dhamija, I.; Grover, P.; Kumar, S. Regulatory landscape and challenges in CAR-T cell therapy development in the US, EU, Japan, and India. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2024, 201, 114361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinRegs. Clinical Research Regulation For India - ClinRegs. 2025.

- AABB.org, I.-. https://www.aabb.org/regulatory-and-advocacy/regulatory-affairs/regulatory-for-cellular-therapies/international-competent-authorities/india#:~:text=All%20other%20forms%20of,ICMR%20registry.&text=marrow%20derived%20stem%20cells%2C,ICMR%20registry.&text=any%20embryonic%20stem%20cell,ICMR%20registry.&text=appropriately%20reviewed%20and%20monitored,ICMR%20registry. (accessed on 03/19/2025).

- Jain., V. Regulation of Biologics in India - Morulaa HealthTech. Available online: https://morulaa.com/regulation-of-biologics-in-india-2/#:~:text=Biologics%20are%20the%20medicinal%2F,in%20India.&text=spin%2Doff%20for%20human%20use.,in%20India.&text=tissues%20etc.%20Biotechnology%20is,in%20India.&text=Drugs%20Standard%20Control%20Organization,in%20India. (accessed on 05/19/2016).

- Thakur, A.; Rai, D. Global requirements for manufacturing and validation of clinical grade extracellular vesicles. J Liq Biopsy 2024, 6, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency, M.a.H.p.R. Advanced therapy medicinal products: regulation and licensing in UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/advanced-therapy-medicinal-products-regulation-and-licensing#:~:text=All%20ATMPs%20to%20be,the%20quality%2C&text=the%20market%20in%20the,the%20quality%2C&text=have%20a%20marketing%20authorisation,the%20quality%2C&text=%29.%20The%20MHRA%20is,the%20quality%2C (accessed on 05/21/2025).

- Asadpour, A.; Yahaya, B.H.; Bicknell, K.; Cottrell, G.S.; Widera, D. Uncovering the gray zone: mapping the global landscape of direct-to-consumer businesses offering interventions based on secretomes, extracellular vesicles, and exosomes. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiadima, M. Can Exosomes Be Injected in the Face? - Premier Laser Clinic. 2024, 2025.

- Devlin, H. Beauty clinics in UK offering banned treatments derived from human cells. The Guardian 2025.

- Bukovac, P.K.; Hauser, M.; Lottaz, D.; Marti, A.; Schmitt, I.; Schochat, T. The Regulation of Cell Therapy and Gene Therapy Products in Switzerland. Adv Exp Med Biol 2023, 1430, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swissmedic. Legal framework governing the use of tissues and cells of human origin. Available online: https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/en/home/humanarzneimittel/besondere-arzneimittelgruppen--ham-/innovation/publikationen/legal-basis-governing-the-use-of-tissues-and-cells-of-human-orig.html (accessed on 05/21/2025).

- Queen, D.; Avram, M.R. Exosomes for Treating Hair Loss: A Review of Clinical Studies. Dermatol Surg 2025, 51, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.H.; Ryu, S.W.; Choi, H.; You, S.; Park, J.; Choi, C. Manufacturing Therapeutic Exosomes: from Bench to Industry. Mol Cells 2022, 45, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Mukerjee, N.; Alharbi, H.M.; Ghosh, A.; Alexiou, A.; Thorat, N.D. Targeted therapies for HPV-associated cervical cancer: Harnessing the potential of exosome-based chipsets in combating leukemia and HPV-mediated cervical cancer. J Med Virol 2024, 96, e29596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.R.; Kourembanas, S.; Mitsialis, S.A. Toward Exosome-Based Therapeutics: Isolation, Heterogeneity, and Fit-for-Purpose Potency. Front Cardiovasc Med 2017, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Nalabotala, R.; Koo, K.M.; Bose, S.; Nayak, R.; Shiddiky, M.J.A. Separation of distinct exosome subpopulations: isolation and characterization approaches and their associated challenges. Analyst 2021, 146, 3731–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Qin, F.; Chen, J. Exosomes: a promising avenue for cancer diagnosis beyond treatment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1344705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, G.; Ramos, E.K.; Wan, Y.; Gius, D.R.; Liu, H. Exosomes as a Drug Delivery System in Cancer Therapy: Potential and Challenges. Mol Pharm 2018, 15, 3625–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhou, X.; He, M.; Shang, Y.; Tetlow, A.L.; Godwin, A.K.; Zeng, Y. Ultrasensitive detection of circulating exosomes with a 3D-nanopatterned microfluidic chip. Nat Biomed Eng 2019, 3, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, S.; Perocheau, D.; Touramanidou, L.; Baruteau, J. The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal 2021, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, C.P.; Mittra, J.; Kojima, N.; Sugiyama, D.; Awatin, J.; Simmons, G. Prospects for Harmonizing Regulatory Science Programs in Europe, Japan, and the United States to Advance Regenerative Medicine. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2016, 50, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndomondo-Sigonda, M.; Miot, J.; Naidoo, S.; Masota, N.; Ng'andu, B.; Ngum, N.; Kaale, E. Harmonization of Medical Products Regulation: A Key Factor for Improving Regulatory Capacity in the East African Community. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom-Gommers, L.; Mullin, T. International Conference on Harmonization: Recent Reforms as a Driver of Global Regulatory Harmonization and Innovation in Medical Products. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019, 105, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosemann, A.; Chaisinthop, N. The pluralization of the international: Resistance and alter-standardization in regenerative stem cell medicine. Soc Stud Sci 2016, 46, 112–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiderman, E.; Boily, A.; Hasilo, C.; Knoppers, B.M. Overcoming barriers to facilitate the regulation of multi-centre regenerative medicine clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, K.; Moradi-Hasanabad, A.; Sobhani-Nasab, A.; Javaheri, J.; Ghasemi, A. Application of cell-derived exosomes in the hematological malignancies therapy. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1263834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, A.; Guo, H.; Zheng, W.; Chen, R.; Miao, C.; Zheng, D.; Peng, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. Exosomes: innovative biomarkers leading the charge in non-invasive cancer diagnostics. Theranostics 2025, 15, 5277–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, E.; Palmer, D.; Fletcher, B.; Vaughn, R. Exosomes in Precision Oncology and Beyond: From Bench to Bedside in Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.K.; Jena, B.C.; Banerjee, I.; Das, S.; Parekh, A.; Bhutia, S.K.; Mandal, M. Exosome as a Novel Shuttle for Delivery of Therapeutics across Biological Barriers. Mol Pharm 2019, 16, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitbon, A.; Delmotte, P.R.; Pistorio, V.; Halter, S.; Gallet, J.; Gautheron, J.; Monsel, A. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles therapy openings new translational challenges in immunomodulating acute liver inflammation. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaalouk, D.; Prasai, A.; Goldberg, D.J.; Yoo, J.Y. Regulatory Aspects of Regenerative Medicine in the United States and Abroad. Dermatological Reviews 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, N.; Zolfi Gol, A.; Shahabi Rabori, V.; Saberiyan, M. Exploring the role of exosomal and non-exosomal non-coding RNAs in Kawasaki disease: Implications for diagnosis and therapeutic strategies against coronary artery aneurysms. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025, 42, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; He, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, N.; Rong, L.; Liu, B. Exosomes derived from miR-26a-modified MSCs promote axonal regeneration via the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway following spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakil, D.; Doshi, R.; McKinnirey, F.; Sidhu, K. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes as New Horizon for Cell-Free Therapeutic Development: Current Status and Prospects. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|