1. Introduction

APL is a distinct subtype of AML characterized by the t (15;17) translocation, which gives rise to the PML-RARA fusion gene [

1]. This fusion protein interferes with RAR signaling and halts myeloid maturation at the promyelocyte stage [

2]. The introduction of ATRA, a derivative of vitamin A, marked a major advance in APL therapy by promoting terminal differentiation of leukemic cells. [

3,

4]. When combined with arsenic trioxide (ATO), ATRA-based regimens induce durable remissions in the vast majority of patients, with cure rates exceeding 90% in newly diagnosed cases [

5].

However, not all patients respond to ATRA. Resistance—whether present at diagnosis or acquired during treatment—occurs in roughly 5-10% of cases and is more common in relapsed or refractory disease [

6,

7]. These patients often face worse outcomes and fewer therapeutic options. Clarifying the molecular mechanisms behind ATRA resistance is key to developing more effective treatment approaches.

Multiple mechanisms have been linked to ATRA resistance. Among the best-characterized are mutations in the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of the RARA portion of the PML-RARA fusion, which reduce retinoid binding and block transcription of genes required for differentiation [

8,

9]. Disruption of PML protein function—whether through genetic mutation or reduced expression—can also impair formation of PML nuclear bodies and prevent degradation of the fusion oncoprotein, further limiting the response to therapy [

10].

Beyond genetic alterations, epigenetic dysregulation also plays a pivotal role in ATRA resistance. For instance, although ATRA induces histone acetylation (e.g., H3K9ac) upon treatment, repressive marks such as H3K27me3 and DNA methylation may persist at retinoic acid response elements (RAREs), silencing key differentiation genes despite retinoid exposure [

11]. Specifically, PLZF-RARA fusion demonstrates heightened recruitment of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), leading to increased H3K27me3 and reduced H3K9/K14 acetylation at target loci, a pattern correlated with ATRA unresponsiveness [

12]. Additionally, dysregulated histone deacetylases (HDACs) contribute significantly to epigenetic resistance. PLZF-RARα and similar fusion proteins recruit corepressor complexes containing HDAC1, maintaining a deacetylated, repressive chromatin environment that blocks transcription of granulocytic differentiation genes [

12]. Targeting HDACs with inhibitors restores an open chromatin state and has shown synergistic effects with ATRA in preclinical models. Moreover, autophagy-mediated degradation of PML-RARA is essential for ATRA efficacy. ATRA and ATO co-treatment induces autophagic flux, marked by increased LC3-II and decreased p62 in NB4 cells; blocking autophagy with bafilomycin impairs PML-RARA degradation and significantly reduces differentiation, highlighting autophagy’s critical role [

13]. Finally, metabolic reprogramming supports ATRA resistance. During ATRA-driven differentiation, NB4 cells shift from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis. Although specific lipid metabolism alterations are less defined in APL, broader cancer models indicate that, under differentiation stress, cells upregulate fatty acid synthesis and redox-balancing pathways to maintain survival—suggesting a metabolic adaptation component in resistant clones [

14].

Several new strategies are under investigation to overcome ATRA resistance. Arsenic trioxide–based combinations remain active in many resistant cases and continue to be a mainstay of salvage therapy [

15]. BCL2 inhibitors, such as venetoclax, have shown potential to enhance differentiation and promote apoptosis in resistant cells [

16]. Tamibarotene (Am80), a synthetic retinoid with greater stability and RARα selectivity than ATRA, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in relapsed APL [

17,

18]. Immunomodulatory approaches, including immune checkpoint inhibition (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1 blockade), are being tested in AML, with early-phase trials in AML showing encouraging hematologic responses and survival signals [

19,

20], suggesting potential applicability in APL as adjuncts to differentiation therapy.

This review outlines current insights into the biology of ATRA resistance in APL and discusses therapeutic strategies that are being developed to improve outcomes in resistant disease.

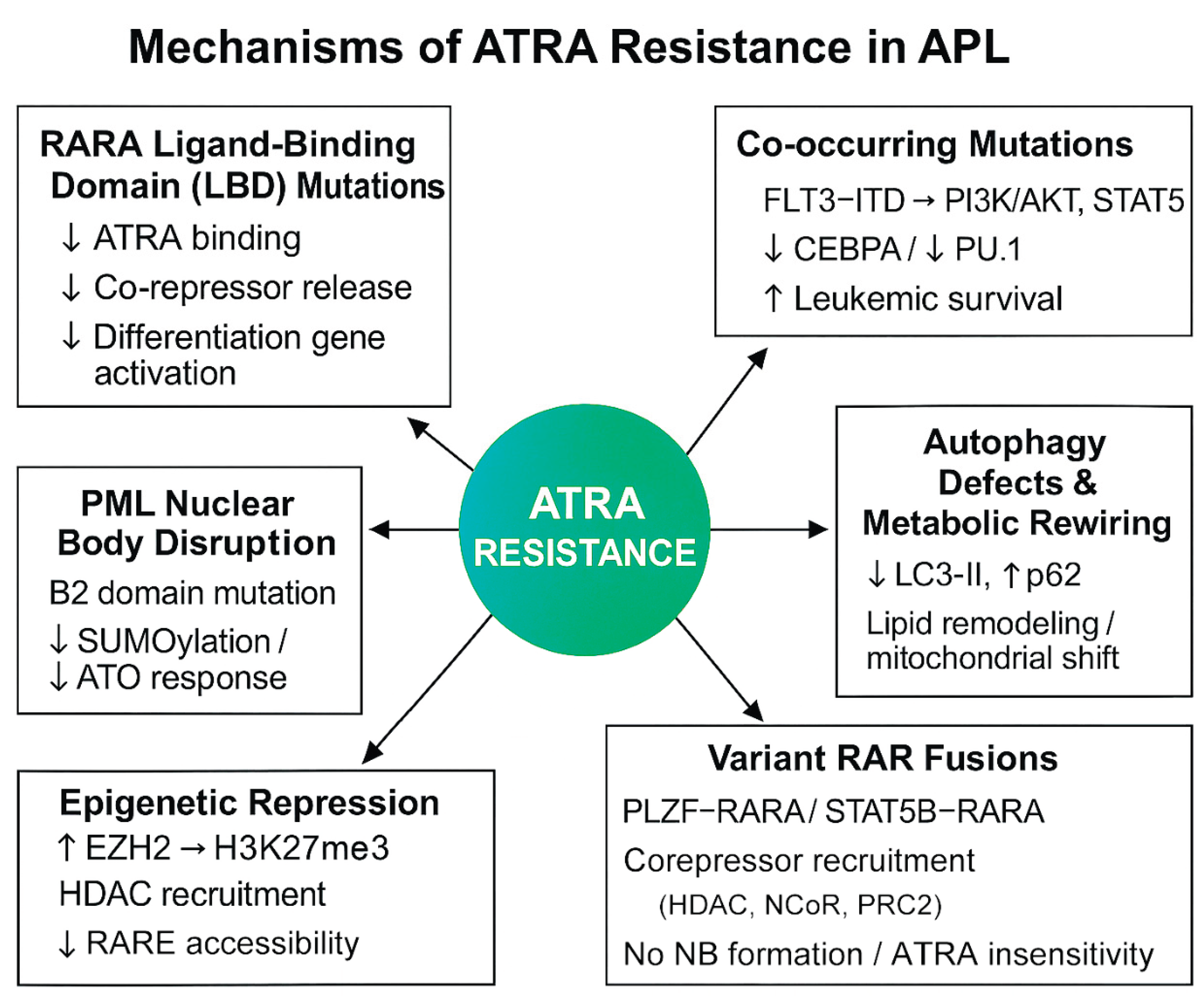

2. Mechanisms of ATRA Resistance

While ATRA has enabled long-term remission in most APL patients, resistance still emerges—especially in relapsed or refractory settings—driven by a multifactorial network of molecular and cellular changes. The following sections offer an in-depth look at each resistance mechanism, as also outlined in the schematic overview presented in

Figure 1.

2.1. RARA Ligand-Binding Domain (LBD) Mutations in PML-RARA

Mutations within the RARA-LBD of the PML-RARA fusion are a dominant mechanism of ATRA resistance. These mutations reduce ATRA binding affinity, hinder release of co-repressors, and impair activation of differentiative genes.

In relapsed APL patients, RARA-LBD mutations were identified in 30–65% of cases, especially after ATRA therapy [

21]. A detailed case reported a seven–amino acids deletion (p.K227_T233del) and point mutation p.R217S in RARA-LBD. The deletion mutant exhibited markedly reduced CD11b induction, impaired NBT reduction, and failure to form PML-NBs upon ATRA or tamibarotene treatment [

22]. In vitro studies (NB4-R sublines) confirmed selection of resistant clones with such LBD mutations under ATRA pressure [

21]. These data validate that LBD mutations confer functional resistance by blocking differentiation and NB restoration.

Notably, the 2022 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommendations emphasized the relevance of molecular profiling at relapse, including detection of RARA-LBD mutations, to guide the selection of second-line agents such as tamibarotene and arsenic trioxide [

23].

2.2. PML–B2 Domain Mutations Affecting NB Integrity

NBs are essential for ATRA- and ATO-mediated degradation of PML-RARA and induction of differentiation.

Mutations in the PML-B2 domain—such as A216V or A216H—disrupt SUMOylation and arsenic binding, thereby blocking NB formation and resulting in persistence of the fusion protein [

24]. These mutations stabilize PML-RARA and may hinder its degradation and apoptotic clearance, thereby compromising the efficacy of combined ATRA/ATO therapy [

24]. Thus, PML-B2 mutations underlie dual resistance to both retinoids and arsenic compounds.

Although such mutations are relatively uncommon, they have been detected in relapsed patients with poor response to ATO-based therapy. In one study, an acquired PML-B2 domain mutation (A216H) was identified in 1 of 14 relapsed APL cases following ATRA/ATO therapy, and was not present at initial diagnosis—suggesting it was acquired during treatment [

24].

In a comprehensive mutational analysis by Madán et al., PML mutations were detected in 12 of 14 relapsed APL samples, with 11 localizing to the B2 domain—particularly at the A216V hotspot—highlighting their potential emergence under ATO selection pressure and their contribution to therapeutic failure [

25].

Routine sequencing of the PML gene is not currently recommended in major guidelines such as ELN or NCCN; however, detection of B2 domain lesions may help explain failure of differentiation and apoptosis in select clinical settings, particularly when resistance to both agents is suspected.

2.3. FLT3-ITD and Other Co-Mutations Activate Survival Pathways

In addition to the PML-RARA fusion that defines APL, co-occurring mutations—most notably internal tandem duplications (ITD) in the FLT3 gene—play a significant role in modulating treatment response and disease progression. FLT3-ITD mutations are detected in approximately 30–35% of newly diagnosed or relapsed APL cases, and are strongly associated with hyperleukocytosis and poor response to ATRA-based therapy [

26,

27,

28].

Mechanistically, FLT3-ITD leads to constitutive activation of downstream signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK, and STAT5, thereby promoting leukemic cell proliferation, survival, and blockade of terminal differentiation [

28]. In APL models, activation of these pathways has been shown to interfere with retinoic acid signaling by reducing expression of key transcription factors such as CEBPA and PU.1, and by inhibiting the reformation of PML-NBs—a process critical for ATRA-mediated degradation of the PML-RARA oncoprotein [

29,

30,

31].

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that pharmacologic inhibition of FLT3 or its downstream effectors can partially restore sensitivity to ATRA. For example, co-treatment with sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor targeting FLT3 and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways, in combination with ATRA, enhanced MCL-1 degradation and induced apoptosis and granulocytic differentiation in FLT3-ITD-positive leukemic cells [

32]. These findings support the rationale for dual targeting of oncogenic signaling and differentiation pathways in resistant APL.

In addition to FLT3-ITD, other co-mutations—including those in NRAS, KRAS, and WT1—have also been reported in APL and may contribute to ATRA resistance through activation of MAPK or by interfering with transcriptional networks required for differentiation [

33]. Although the mechanistic contributions of these mutations in APL are less well-defined than those of FLT3-ITD, their recurrence in relapsed and refractory disease highlights the need for comprehensive genomic profiling to guide combination therapeutic strategies.

2.4. Epigenetic Repression: Histone Methylation and HDAC Activity

Epigenetic silencing significantly undermines ATRA efficacy in APL, with resistant cells often exhibiting elevated levels of H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) at RAREs, enforced by PRC2 under EZH2 control—effectively blocking transcription of differentiation genes [

34]. In variant APL driven by non–PML-RARA fusions such as PLZF-RARA, EZH2 plays a central role in maintaining transcriptional repression.

Although SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors were ineffective, EZH2-selective degraders restored ATRA sensitivity in a PLZF-RARA mouse model by eliminating H3K27me3 and promoting granulocytic differentiation [

35].

Similarly, ATRA-resistant APL and AML cells demonstrate pathological recruitment of HDACs and persistent deacetylation at RAREs. For instance, ATRA treatment fails to displace HDACs effectively in resistant NB4 cells, but combining ATRA with HDAC inhibitors such as FK228 or SAHA restores RARE acetylation, reactivates key myeloid differentiation genes, and induces apoptosis [

36].

Preclinical data also show that combining EZH2 inhibitors (e.g., tazemetostat analogs) or selective HDAC inhibitors with ATRA reduces H3K27me3, restores histone acetylation, re-establishes expression of granulocytic differentiation markers, and induces apoptosis—providing a rationale for ongoing trials of ATRA-epigenetic drug combinations [

37,

38].

2.5. Defects in Autophagy and Metabolic Reprogramming

Autophagy is crucial for the degradation of the PML-RARA oncoprotein during ATRA (and ATO) therapy in APL, whereas defects in this pathway contribute significantly to therapeutic resistance. A comprehensive review in Blood describes how ATRA weakly induces autophagic flux in NB4 cells, leading to the formation of autophagosomes that gradually degrade PML-RARA, and emphasizes that pharmacological inhibitors such as bafilomycin or genetic knockdown of key autophagy genes markedly reduce ATRA-induced differentiation—highlighting the critical role of autophagy in restoring PML-NBs and granulocytic maturation in resistant models [

13].

Studies have shown that ATRA induces autophagy in NB4 cells, as evidenced by increased LC3-II and decreased p62, contributing to granulocytic differentiation. Pharmacological activation of autophagy using rapamycin further enhances these effects, indicating synergy between autophagy and ATRA signaling in promoting maturation [

39]. Although such studies have not specifically focused on resistant NB4 sublines, these findings support the therapeutic rationale for targeting autophagy in cases of impaired differentiation [

13].

In parallel, metabolic reprogramming may also contribute to ATRA resistance. ATRA-treated NB4 cells exhibit mitochondrial remodeling and alterations in cardiolipin composition, potentially reflecting shifts in lipid handling and phospholipid metabolism [

40]. While specific fatty acid synthesis enzymes like FASN have not yet been directly linked to ATRA resistance in APL, similar metabolic rewiring in AML supports the hypothesis that targeting lipid synthesis and oxidative stress pathways may sensitize resistant leukemic clones.

Together, these studies underscore that defects in autophagy and metabolic reprogramming form a dual barrier to differentiation therapy, and that their pharmacologic modulation represents a promising strategy to overcome ATRA resistance.

2.6. Variant RAR Fusions and Atypical Translocations

A minority of APL cases are characterized by alternative RAR family fusion proteins, such as PLZF-RARA, STAT5B-RARA, NPM1-RARA, and CPSF6-RARG, arising from atypical chromosomal translocations [

41]. These variant fusions generate leukemia with APL-like morphology and clinical features but exhibit primary resistance to ATRA- and ATO-based therapies [

12].

Mechanistically, PLZF-RARA recruits transcriptional corepressors including nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR), silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT), HDACs, and Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), leading to persistent chromatin repression at RAREs through elevated H3K27me3 and reduced acetylation marks [

12,

34]. This repressive chromatin state silences critical differentiation genes and is not reversed by ATRA alone. Moreover, unlike PML-RARA, PLZF-RARA does not undergo ATRA/ATO-induced degradation and fails to restore PML-NB formation [

42]. Similar resistance profiles have been observed for STAT5B-RARA and CPSF6-RARG, although mechanistic details for these fusions are less well characterized [

41].

Therapeutic strategies for variant APL remain limited, and such fusion-driven cases often require alternative, mechanism-informed approaches. These include epigenetic modulators and targeted agents, which are further discussed in the following section.

3. Summary

ATRA resistance develops through multifaceted mechanisms:

(1) LBD mutations that disable retinoid binding,

(2) PML domain mutations that disrupt NB assembly,

(3) Co-mutational activation of survival pathways,

(4) Epigenetic repression of differentiation genes,

(5) Impaired autophagy and metabolic adaptation, and

(6) Variant RAR fusions resistant to standard therapies.

In many relapsed cases, these resistance mechanisms act synergistically, allowing leukemic subclones to persist despite targeted differentiation therapy. Comprehensive molecular profiling at relapse is therefore critical to guide combination treatment strategies.

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome ATRA Resistance

As insight into the mechanisms of ATRA resistance deepens, several promising therapeutic strategies have emerged. These largely fall into four categories: optimized retinoid analogs, combination therapies with targeting agents, integration of ATRA with arsenic, and immunotherapy/targeted therapies for specific mutations.

3.1. Next-Generation Retinoids: Tamibarotene

Tamibarotene (Am80) is a synthetic RARα-selective agonist developed to overcome resistance due to RARA-LBD mutations. Its higher binding affinity and slower metabolism enable greater efficacy than ATRA in resistant APL. A phase II trial in adult patients with relapsed/refractory APL post-ATO + ATRA reported an overall response rate of 64 % (CR rate 43 %) and median overall survival of 9.5 months, despite frequent relapses (median EFS of 3.5 months) [

17]. Notably, tamibarotene induced durable remissions in some cases when combined with arsenic trioxide, including a case report achieving molecular CR in a patient refractory to both agents alone [

43]. These results support ongoing trials combining tamibarotene with arsenic or epigenetic drugs.

3.2. ATO Combinations

ATO remains effective against ATRA-resistant APL due to its ability to degrade PML-RARA independently of the RARA-LBD. In relapsed/refractory settings, ATO as a single agent achieves high response rates [

17]. Combination regimens with ATRA and/or gemtuzumab-ozogamicin have demonstrated improved survival: e.g., ATRA + ATO achieved >90 % cure rates in both non-high-risk and high-risk cohorts, reducing early mortality and obviating the need for chemotherapy in many cases [

41]. Mechanistically, ATRA enhances arsenic uptake by inducing AQP9, thereby facilitating more efficient degradation of PML-RARA. [

42].

3.3. Targeted Therapy: FLT3 and BCL2 Inhibitors

FLT3-ITD mutations, frequent in ATRA-resistant APL, drive pro-survival signaling and blunt differentiation. Preclinical data show that FLT3 inhibitors (e.g., quizartinib) can reactivate ATRA sensitivity by interrupting PI3K/AKT signaling and restoring PML-RARA degradation [

42]. Similarly, overexpression of anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins in resistant APL makes venetoclax an attractive partner. Even though venetoclax data in APL are limited, combining it with tamibarotene and hypomethylating agents in RARA-positive AML shows encouraging responses (ORR ~67 %), providing a rationale for exploring similar combinations in ATRA-resistant APL.

3.4. Immunotherapy and Targeted Agents for Variant Fusions

Variant APLs driven by non–PML-RARA fusions—such as PLZF-RARA, STAT5B-RARA, and CPSF6-RARG—remain intrinsically resistant to conventional differentiation therapy [

44]. These fusion proteins often recruit robust transcriptional repressors, including HDACs and PRC2, resulting in persistent epigenetic silencing of key myeloid genes. Unlike PML-RARA, these variants are not effectively degraded by ATRA or ATO, and do not restore PML-NBs, limiting the effectiveness of standard therapies [

44].

To overcome this resistance, recent studies have investigated the potential of epigenetic modifiers. In PLZF-RARA-driven APL models, inhibition of EZH2—the enzymatic core of PRC2—has been shown to restore retinoic acid sensitivity. Single-cell multiomic profiling revealed that PLZF-RARA leukemic clones exhibit strong dependence on EZH2, and its inhibition selectively eliminated resistant subpopulations and prolonged survival in vivo [

34]. Additionally, HDAC inhibitors such as valproic acid have demonstrated the ability to relieve transcriptional repression imposed by these fusions, partially reactivating differentiation programs in vitro [

12].

Beyond epigenetic targeting, immunotherapeutic strategies are being explored. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade has shown promising activity in preclinical AML models and early-phase clinical trials, primarily through reversal of T-cell exhaustion and reactivation of anti-leukemic immunity [

19,

20]. These agents may help reverse T-cell exhaustion and enhance immune surveillance in the leukemic microenvironment. Although their efficacy in variant APL has not been directly tested, early-phase AML trials suggest that integrating immunotherapy with epigenetic modulators could overcome immune evasion mechanisms and improve treatment durability [

45].

These findings highlight the need for integrated therapeutic strategies in APL cases with non-canonical RAR fusions, where standard differentiation therapy fails. Combinations that simultaneously target epigenetic repression and immune evasion—designed with fusion-specific molecular features in mind—may offer a rational path forward in this challenging subset.

3.5. Oral Arsenic and Maintenance Strategies

To improve convenience and reduce toxicity, oral arsenic formulations have been introduced. Notably, in Hong Kong, oral arsenic combined with ATRA demonstrated effective maintenance therapy without requiring stem cell transplantation in relapsed pediatric cases [

46]. Similar strategies are under prospective evaluation to consolidate remissions achieved after initial ATRA/ATO or tamibarotene-based therapy.

Taken together, modern ATRA-resistant APL therapy is evolving from monotherapy to rational combinations guided by molecular profiling. Key future directions include:

(1) Randomized trials of tamibarotene + ATO/epigenetic modulators in resistant APL.

(2) Biomarker-driven strategies—e.g., FLT3-ITD or CD33 expression—to personalize targeted therapy.

(3) Optimized administration routes (oral arsenic) to reduce treatment burden.

(4) Adaptation to rare fusions, using immunotherapy and epigenetic drugs in precision medicine approaches.

Table 1.

Overview of Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for ATRA-Resistant APL.

Table 1.

Overview of Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for ATRA-Resistant APL.

| Strategy |

Mechanism |

Supporting Evidence |

| Tamibarotene |

RARα-selective retinoid; overcomes RARA-LBD mutations |

Phase II trial: ORR 64%, CR 43%, OS 9.5 mo (Ref [17]); effective with ATO (Ref [43]) |

| ATO combinations |

PML-RARA degradation independent of RARA-LBD; AQP9 synergy |

ATRA+ATO cure >90% in both risk groups (Ref [41]); AQP9-mediated uptake (Ref [42]) |

| FLT3 or BCL2 inhibitors |

Target pro-survival pathways in resistant APL |

Preclinical ATRA sensitization (FLT3i: Ref [42]); AML RARA+ ORR ~67% with venetoclax |

| Epigenetic/Immune therapies |

Reverse chromatin repression and immune evasion |

EZH2/HDAC inhibition restores RA sensitivity in PLZF-RARA models (Refs [12,34]); PD-1/PD-L1 active in early AML trials (Refs [19,20]) |

| Oral arsenic maintenance |

Enables outpatient remission maintenance |

Pediatric relapsed APL: effective ATRA+oral-ATO maintenance (Ref [46]) |

4. Conclusions

The treatment landscape of APL has been transformed by ATRA-based therapy, yet resistance remains a critical obstacle in a subset of patients. ATRA resistance arises from diverse biological mechanisms, including RARA-LBD mutations, PML-NB disruption, epigenetic silencing of differentiation programs, and oncogenic signaling pathway activation. In addition, metabolic reprogramming and the emergence of variant RARA or RARG fusions further complicate management.

Advances in molecular profiling and preclinical modeling have enabled the development of targeted strategies to overcome resistance. These include next-generation retinoids like tamibarotene, arsenic-based combinations, and inhibitors of FLT3, BCL2, and epigenetic regulators. Furthermore, novel approaches are being explored for rare APL-like leukemias that do not respond to conventional differentiation therapy.

Going forward, personalized treatment strategies guided by the genomic and epigenomic features of each patient’s leukemia will be key to improving outcomes. Future progress will hinge on rigorous clinical testing of combination regimens, the pragmatic shift toward oral formulations to ease treatment adherence, and the thoughtful integration of immunotherapies—especially for cases no longer responsive to ATRA monotherapy.

Ultimately, overcoming ATRA resistance will demand an individualized, biology-driven approach—one that strategically combines agents targeting distinct resistance pathways, instead of depending on a single modality.

Author Contributions

L.H. conceived the manuscript. L.H. and J.N. wrote the manuscript. B.Z. designed the figures. L.H., J.N. and B.Z. edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2020GG0292) and the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2021LHMS08028).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; APL-like, acute promyelocytic leukemia-like; ATO, arsenic trioxide; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CD33, cluster of differentiation 33; CEBPA, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha; CPSF6, cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 6; CR, complete remission; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; FASN, fatty acid synthase; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; FLT3-ITD, FLT3 internal tandem duplication; G9A, euchromatic histone lysine methyltransferase 2; HDAC, histone deacetylase; H3K27me3, histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation; H3K9ac, histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation; LBD, ligand-binding domain; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCL-1, myeloid cell leukemia 1; NB, nuclear body; NB4, a human APL cell line; NBT, nitroblue tetrazolium; NCoR, nuclear receptor corepressor; ORR, overall response rate; PML, promyelocytic leukemia; PML-NB, PML nuclear body; PML-RARA, promyelocytic leukemia-retinoic acid receptor alpha; PRC2, Polycomb Repressive Complex 2; PU.1, purine-rich box 1; RA, retinoic acid; RARA, retinoic acid receptor alpha; RARG, retinoic acid receptor gamma; RARE, retinoic acid response element; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine; SAHA, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid; SMRT, silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors; STAT5, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5; SUMOylation, small ubiquitin-like modifier modification; WT1, Wilms’ tumor 1.

References

- Melnick, A.; Licht, J.D. Deconstructing a disease: RARalpha, its fusion partners, and their roles in the pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 1999, 93, 3167–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de The, H.; Chen, Z. Acute promyelocytic leukaemia: novel insights into the mechanisms of cure. Nat Rev Cancer 2010, 10, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.E.; Ye, Y.C.; Chen, S.R.; Chai, J.R.; Lu, J.X.; Zhoa, L.; Gu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Y. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 1988, 72, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Coco, F.; Avvisati, G.; Vignetti, M.; Thiede, C.; Orlando, S.M.; Iacobelli, S.; Ferrara, F.; Fazi, P.; Cicconi, L.; Di Bona, E.; et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, C.C.; Tavakkoli, M.; Tallman, M.S. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: where did we start, where are we now, and the future. Blood Cancer J 2015, 5, e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, G.A.; Kats, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. Synergy against PML-RARa: targeting transcription, proteolysis, differentiation, and self-renewal in acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Exp Med 2013, 210, 2793–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann-Che, J.; Bally, C.; de The, H. Resistance to therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 1170–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, R.E.; Yeap, B.Y.; Bi, W.; Livak, K.J.; Beaubier, N.; Rao, S.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Tallman, M.S.; Slack, J.L.; et al. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of PML-RAR alpha mRNA in acute promyelocytic leukemia: assessment of prognostic significance in adult patients from intergroup protocol 0129. Blood 2003, 101, 2521–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood 2008, 111, 2505–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach, V.; de The, H. PML nuclear bodies: from architecture to function. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2018, 52, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.; Sultan, M.; Vidovic, D.; Dean, C.A.; Cruickshank, B.M.; Lee, K.; Loung, C.Y.; Holloway, R.W.; Hoskin, D.W.; Waisman, D.M.; et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide induce lasting differentiation and demethylation of target genes in APL cells. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, M.F.; Mikesch, J.H.; Fung, T.K.; So, C.W. Epigenetics in acute promyelocytic leukaemia pathogenesis and treatment response: a TRAnsition to targeted therapies. Br J Cancer 2015, 112, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakson, P.; Bjoras, M.; Boe, S.O.; Simonsen, A. Autophagy contributes to therapy-induced degradation of the PML/RARA oncoprotein. Blood 2010, 116, 2324–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caricasulo, M.A.; Zanetti, A.; Terao, M.; Garattini, E.; Paroni, G. Cellular and micro-environmental responses influencing the antitumor activity of all-trans retinoic acid in breast cancer. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, R.; Guillemin, M.C.; Ferhi, O.; Soilihi, H.; Peres, L.; Berthier, C.; Rousselot, P.; Robledo-Sarmiento, M.; Lallemand-Breitenbach, V.; Gourmel, B.; et al. Eradication of acute promyelocytic leukemia-initiating cells through PML-RARA degradation. Nat Med 2008, 14, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopleva, M.; Pollyea, D.A.; Potluri, J.; Chyla, B.; Hogdal, L.; Busman, T.; McKeegan, E.; Salem, A.H.; Zhu, M.; Ricker, J.L.; et al. Efficacy and Biological Correlates of Response in a Phase II Study of Venetoclax Monotherapy in Patients with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016, 6, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, D.; Lo-Coco, F.; Sanz, M.A.; Di Bona, E.; Coutre, S.; Altman, J.K.; Wetzler, M.; Allen, S.L.; Ravandi, F.; Kantarjian, H.; et al. Tamibarotene in patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia relapsing after treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide. Br J Haematol 2015, 171, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, A.; Asou, N.; Atsuta, Y.; Sakura, T.; Ueda, Y.; Sawa, M.; Dobashi, N.; Taniguchi, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Nakagawa, M.; et al. Tamibarotene maintenance improved relapse-free survival of acute promyelocytic leukemia: a final result of prospective, randomized, JALSG-APL204 study. Leukemia 2019, 33, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, Y.; Zeidan, A.M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Llobell, M.; Peleteiro Raindo, A.; Climent Medina, J.; Gomez Centurion, I.; Mosquera Orgueira, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 882531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, R.E.; Schachter-Tokarz, E.L.; Zhou, D.C.; Ding, W.; Kim, S.H.; Sankoorikal, B.J.; Bi, W.; Livak, K.J.; Slack, J.L.; Willman, C.L. Relapse of acute promyelocytic leukemia with PML-RARalpha mutant subclones independent of proximate all-trans retinoic acid selection pressure. Leukemia 2006, 20, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, H.; Ishikawa, Y.; Kawashima, N.; Akashi, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Harada, Y.; Hirano, D.; Adachi, Y.; Miyao, K.; Ushijima, Y.; et al. Identification of the novel deletion-type PML-RARA mutation associated with the retinoic acid resistance in acute promyelocytic leukemia. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0204850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasan, A.; Haferlach, C.; Perglerova, K.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, T. Molecular landscape of acute promyelocytic leukemia at diagnosis and relapse. Haematologica 2017, 102, e222–e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, V.; Shyamsunder, P.; Han, L.; Mayakonda, A.; Nagata, Y.; Sundaresan, J.; Kanojia, D.; Yoshida, K.; Ganesan, S.; Hattori, N.; et al. Comprehensive mutational analysis of primary and relapse acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2016, 30, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, R.E.; Hills, R.; Pizzey, A.R.; Kottaridis, P.D.; Swirsky, D.; Gilkes, A.F.; Nugent, E.; Mills, K.I.; Wheatley, K.; Solomon, E.; et al. Relationship between FLT3 mutation status, biologic characteristics, and response to targeted therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2005, 106, 3768–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnault, C.; Rahme, R.; Rice, K.L.; Berthier, C.; Gaillard, C.; Quentin, S.; Maubert, A.L.; Kogan, S.; de The, H. FLT3-ITD impedes retinoic acid, but not arsenic, responses in murine acute promyelocytic leukemias. Blood 2019, 133, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan, E.; Montesinos, P.; Camos, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Calasanz, M.J.; Roman-Gomez, J.; Gomez-Casares, M.T.; Ayala, R.; Lopez, J.; Fuster, O.; et al. Prognostic value of FLT3 mutations in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy. Haematologica 2011, 96, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Friedman, A.D.; Levis, M.; Li, L.; Weir, E.G.; Small, D. Internal tandem duplication mutation of FLT3 blocks myeloid differentiation through suppression of C/EBPalpha expression. Blood 2004, 103, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, C.; Schwable, J.; Brandts, C.; Tickenbrock, L.; Sargin, B.; Kindler, T.; Fischer, T.; Berdel, W.E.; Muller-Tidow, C.; Serve, H. AML-associated Flt3 kinase domain mutations show signal transduction differences compared with Flt3 ITD mutations. Blood 2005, 106, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Cai, J.; Zhu, J.; Lang, W.; Zhong, J.; Zhong, H.; Chen, F. Modulation of FLT3 through decitabine-activated C/EBPa-PU.1 signal pathway in FLT3-ITD positive cells. Cell Signal 2019, 64, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xia, L.; Gabrilove, J.; Waxman, S.; Jing, Y. Sorafenib Inhibition of Mcl-1 Accelerates ATRA-Induced Apoptosis in Differentiation-Responsive AML Cells. Clin Cancer Res 2016, 22, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann-Che, J.; Bally, C.; Letouze, E.; Berthier, C.; Yuan, H.; Jollivet, F.; Ades, L.; Cassinat, B.; Hirsch, P.; Pigneux, A.; et al. Dual origin of relapses in retinoic-acid resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplineau, M.; Platet, N.; Mazuel, A.; Herault, L.; N'Guyen, L.; Koide, S.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Kuribayashi, W.; Carbuccia, N.; Haboub, L.; et al. Noncanonical EZH2 drives retinoic acid resistance of variant acute promyelocytic leukemias. Blood 2022, 140, 2358–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbirkov, Y.; Schenk, T.; Kwok, C.; Stengel, S.; Brown, R.; Brown, G.; Chesler, L.; Zelent, A.; Fuchter, M.J.; Petrie, K. Dual inhibition of EZH2 and G9A/GLP histone methyltransferases by HKMTI-1-005 promotes differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1076458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noack, K.; Mahendrarajah, N.; Hennig, D.; Schmidt, L.; Grebien, F.; Hildebrand, D.; Christmann, M.; Kaina, B.; Sellmer, A.; Mahboobi, S.; et al. Analysis of the interplay between all-trans retinoic acid and histone deacetylase inhibitors in leukemic cells. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91, 2191–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Xin, X.; Hu, H. The epigenetic role of EZH2 in acute myeloid leukemia. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ma, T.; Yu, B. Targeting epigenetic regulators to overcome drug resistance in cancers. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfali, N.; O'Donovan, T.R.; Nyhan, M.J.; Britschgi, A.; Tschan, M.P.; Cahill, M.R.; Mongan, N.P.; Gudas, L.J.; McKenna, S.L. Induction of autophagy is a key component of all-trans-retinoic acid-induced differentiation in leukemia cells and a potential target for pharmacologic modulation. Exp Hematol 2015, 43, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, M.; Goracci, L.; Schlaefli, A.; Di Veroli, A.; Kurosaki, M.; Guarrera, L.; Bolis, M.; Foglia, M.; Lupi, M.; Tschan, M.P.; et al. Role of cardiolipins, mitochondria, and autophagy in the differentiation process activated by all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.G.; Elias, L.; Stanchina, M.; Watts, J. The treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia in 2023: Paradigm, advances, and future directions. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1062524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhi, F.; Wen, Z.; Gao, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, B.; Bai, Y. An overview of arsenic trioxide-involved combined treatment algorithms for leukemia: basic concepts and clinical implications. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, M.; Ogiya, D.; Ichiki, A.; Hara, R.; Amaki, J.; Kawai, H.; Numata, H.; Sato, A.; Miyamoto, M.; Suzuki, R.; et al. Refractory acute promyelocytic leukemia successfully treated with combination therapy of arsenic trioxide and tamibarotene: A case report. Leuk Res Rep 2016, 5, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Yu, W.; Jin, J. Current views on the genetic landscape and management of variant acute promyelocytic leukemia. Biomark Res 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimbu, L.; Mesaros, O.; Popescu, C.; Neaga, A.; Berceanu, I.; Dima, D.; Gaman, M.; Zdrenghea, M. Is There a Place for PD-1-PD-L Blockade in Acute Myeloid Leukemia? Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.; Raghupathy, R.; Lee, C.Y.Y.; Yung, Y.; Chu, H.T.; Ni, M.Y.; Xiao, X.; Flores, F.P.; Yim, R.; Lee, P.; et al. Acute promyelocytic leukaemia: population-based study of epidemiology and outcome with ATRA and oral-ATO from 1991 to 2021. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).