Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Basics of MRI

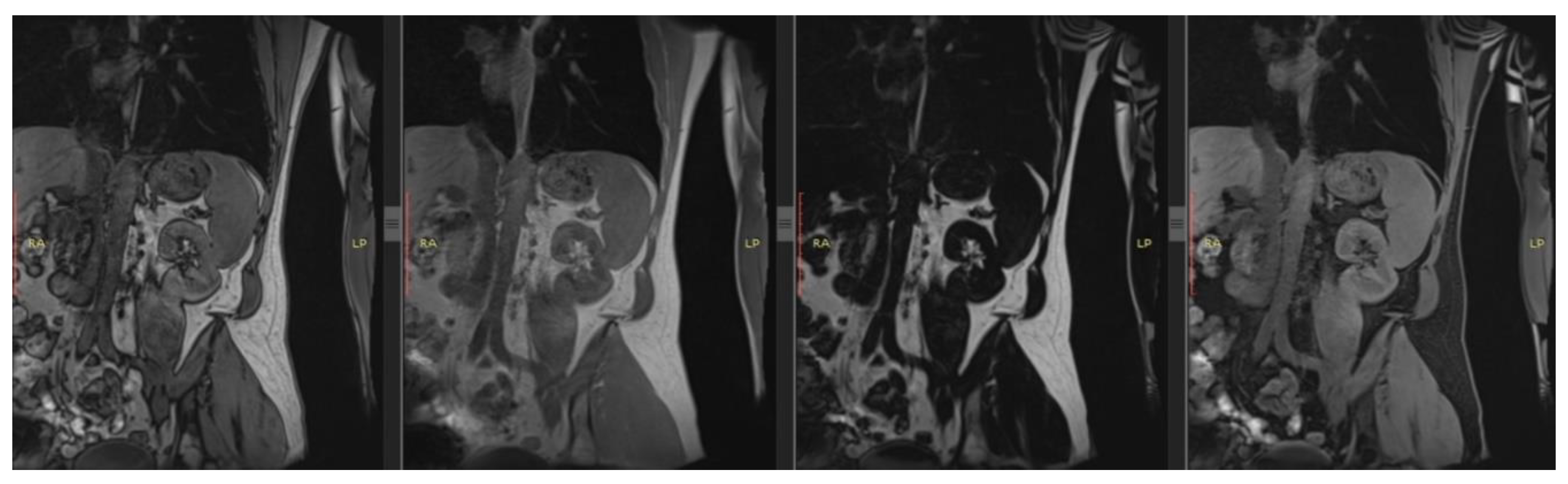

3. T1 and T2

3.1. Principles

3.2. Clinical Utility

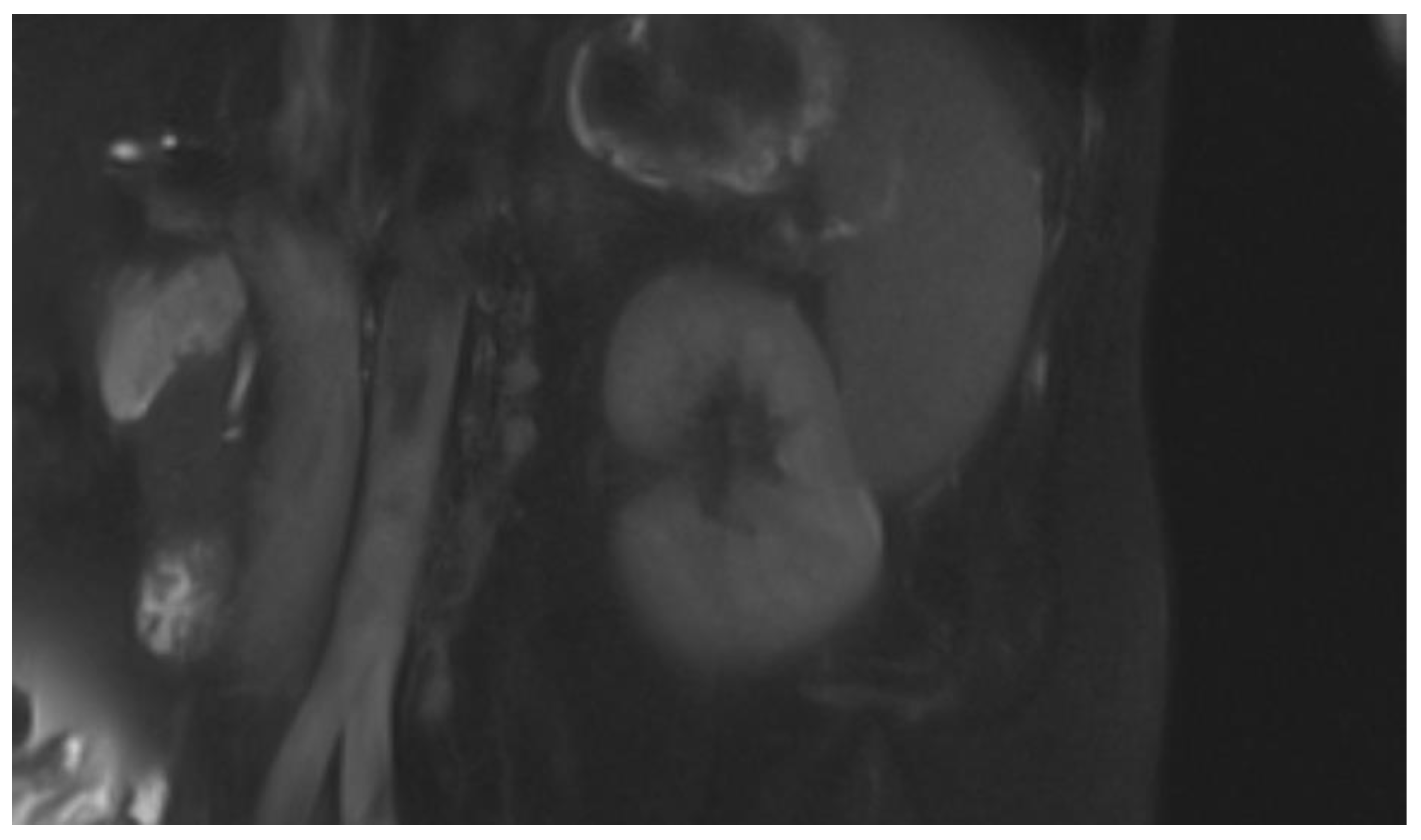

4. DWI

4.1. Principles

4.2. Clinical Utility

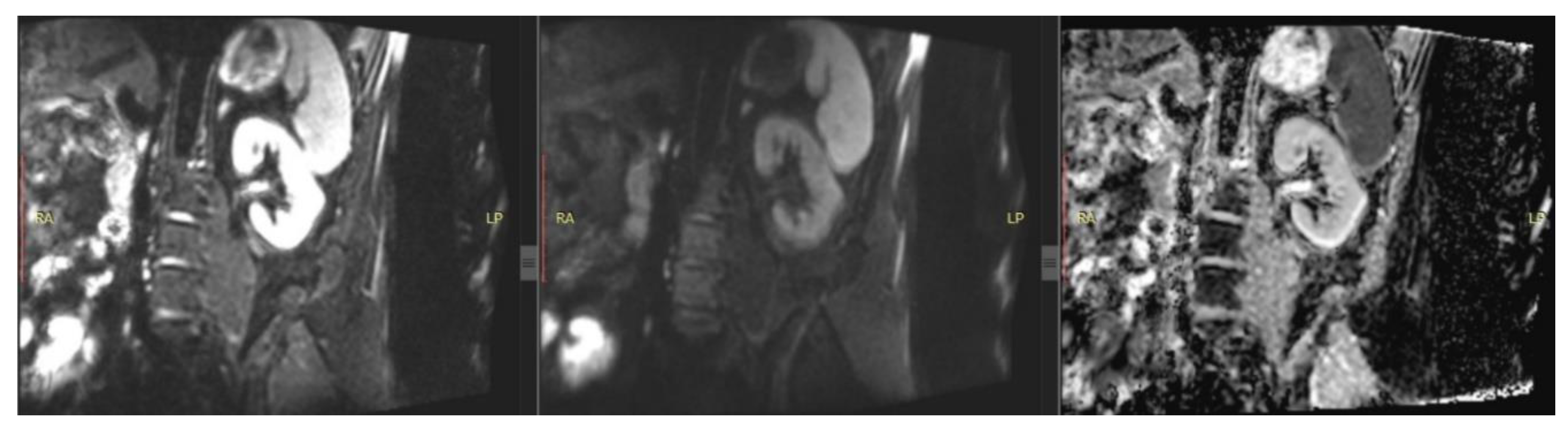

5. Phase Contrast

5.1. Principles

5.2. Clinical Utility

6. BOLD

6.1. Principles

6.2. Clinical Utility

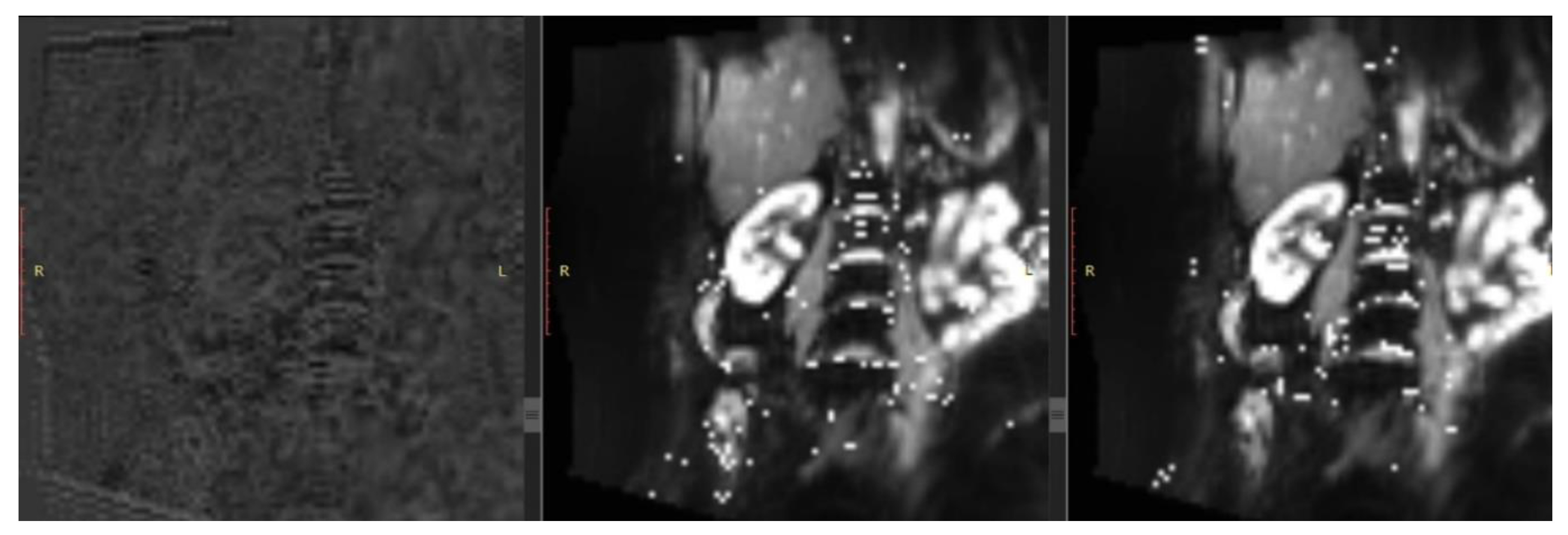

7. ASL

7.1. Principles

7.2. Clinical Utility

8. Conclusions

9. Limitations of the Method

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. 2024. [CrossRef]

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, 709–733. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; You, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Shao, L. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease among adolescents and emerging adults from 1990 to 2021. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhou, K.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Global burden and epidemic trends of chronic kidney disease attributable to high body mass index: insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47. [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, I.; Clementi, A.; Sessa, C.; Torrisi, I.; Meola, M. Ultrasound and color Doppler applications in chronic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 2018, 31, 863–879. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Lin, L.C.; Pan, S.Y.; Huang, J.W.; Chang, Y.C.; Chiang, J.Y.; Kao, H.L.; Luo, P.J.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, B. Bin Use of iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast media in patients with chronic kidney disease: Consensus statements from nephrologists, cardiologists, and radiologists at National Taiwan University Hospital. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Caroli, A.; Remuzzi, A.; Remuzzi, G. Does MRI trump pathology? A new era for staging and monitoring of kidney fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 442–444. [CrossRef]

- Selby, N.M.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Boor, P.; Combe, C.; Eckardt, K.U.; Eikefjord, E.; Garcia-Fernandez, N.; Golay, X.; Gordon, I.; Grenier, N.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers for chronic kidney disease: a position paper from the European Cooperation in Science and Technology Action PARENCHIMA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2018, 33, ii4–ii14. [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.E.; Brunt, V.E.; Shiu, Y.-T.; Bunsawat, K. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease: a clinical perspective. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Garcia, J.A.; Keefe, J.A.; Song, J.; Li, N.; Wehrens, X.H.T. Mechanisms underlying atrial fibrillation in chronic kidney disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2025, 205, 37–51. [CrossRef]

- Efiong, E.E.; Maedler, K.; Effa, E.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Peters, E.; Ikebiuro, J.O.; Soremekun, C.; Ihediwa, U.; Niu, J.; Fuchs, M.; et al. Decoding diabetic kidney disease: a comprehensive review of interconnected pathways, molecular mediators, and therapeutic insights. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.S.Z.; Yu, B.; Gao, Q.; Dong, H.L.; Li, Z.L. The critical role of ion channels in kidney disease: perspective from AKI and CKD. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2488139. [CrossRef]

- Scherzinger, A.L.; Hendee, W.R. Basic Principles of Magnetic Resonance Imaging—An Update. West. J. Med. 1985, 143, 782.

- Schaeffter, T.; Dahnke, H. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2008, 185, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.L.M.; Wright, G.A. Rapid high-resolution T1 mapping by variable flip angles: Accurate and precise measurements in the presence of radiofrequency field inhomogeneity. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 55, 566–574. [CrossRef]

- Moser, E.; Stadlbauer, A.; Windischberger, C.; Quick, H.H.; Ladd, M.E. Magnetic resonance imaging methodology. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2009, 36, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, A.J.; Mayne, K.; Allwood-Spiers, S.; Hall Barrientos, P.; Roditi, G.; Gillis, K.A.; Mark, P.B. Will advances in functional renal magnetic resonance imaging translate to the nephrology clinic? Nephrology 2022, 27, 223–230. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; De Boer, A.; Sharma, K.; Boor, P.; Leiner, T.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Moser, E.; Caroli, A.; Jerome, N.P. Magnetic resonance imaging T1- and T2-mapping to assess renal structure and function: a systematic review and statement paper. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2018, 33, II41–II50. [CrossRef]

- Selby, N.M.; Bmbs, B.; Frcp, D.M.; Francis, S.T. Assessment of Acute Kidney Injury using MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2025, 61, 25–41. [CrossRef]

- Marotti, M.; Hricak, H.; Terrier, F.; McAninch, J.W.; Thuroff, J.W. MR in renal disease: importance of cortical-medullary distinction. Magn. Reson. Med. 1987, 5, 160–172. [CrossRef]

- Hricak, H.; Terrier, F.; Marotti, M.; Engelstad, B.L.; Filly, R.A.; Vincenti, F.; Duca, R.M.; Bretan, P.N.; Higgins, C.B.; Feduska, N. Posttransplant renal rejection: comparison of quantitative scintigraphy, US, and MR imaging. 1987, 162, 685–688. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, B.; Nelson, R.; Ball, T.; Wyly, J.; Bourke, E.; Delaney, V.; Bernardino, M.; Baumgartner, B.; Nelson, R.; Ball, T.; et al. MR imaging of renal transplants. https://www.ajronline.org/ 2012, 147, 949–953. [CrossRef]

- Yusa, Y.; Kundel, H.L. Magnetic resonance imaging following unilateral occlusion of the renal circulation in rabbits. Radiology 1985, 154, 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, A.; Hentschel, J.; Fechner, M.; Hoff, U.; Bubalo, G.; Arakelyan, K.; Cantow, K.; Seeliger, E.; Flemming, B.; Waiczies, H.; et al. High temporal resolution parametric MRI monitoring of the initial ischemia/reperfusion phase in experimental acute kidney injury. PLoS One 2013, 8. [CrossRef]

- Hueper, K.; Rong, S.; Gutberlet, M.; Hartung, D.; Mengel, M.; Lu, X.; Haller, H.; Wacker, F.; Meier, M.; Gueler, F. T2 relaxation time and apparent diffusion coefficient for noninvasive assessment of renal pathology after acute kidney injury in mice: comparison with histopathology. Invest. Radiol. 2013, 48, 834–842. [CrossRef]

- Franke, M.; Baeßler, B.; Vechtel, J.; Dafinger, C.; Höhne, M.; Borgal, L.; Göbel, H.; Koerber, F.; Maintz, D.; Benzing, T.; et al. Magnetic resonance T2 mapping and diffusion-weighted imaging for early detection of cystogenesis and response to therapy in a mouse model of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1544–1554. [CrossRef]

- Schmidbauer, M.; Rong, S.; Gutberlet, M.; Chen, R.; Bräsen, J.H.; Hartung, D.; Meier, M.; Wacker, F.; Haller, H.; Gueler, F.; et al. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging and Mapping of T1 and T2 Relaxation Time for Evaluation of Chronic Renal Allograft Rejection in a Translational Mouse Model. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hueper, K.; Hensen, B.; Gutberlet, M.; Chen, R.; Hartung, D.; Barrmeyer, A.; Meier, M.; Li, W.; Jang, M.S.; Mengel, M.; et al. Kidney Transplantation: Multiparametric Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Assessment of Renal Allograft Pathophysiology in Mice. Invest. Radiol. 2016, 51, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.S.; Kaur, M.; Bokacheva, L.; Chen, Q.; Rusinek, H.; Thakur, R.; Moses, D.; Nazzaro, C.; Kramer, E.L. What causes diminished corticomedullary differentiation in renal insufficiency? J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2007, 25, 790–795. [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.W.L.; Bydder, G.M.; Steiner, R.E.; Bryant, D.J.; Young, I.R. Magnetic resonance imaging of the kidneys. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1984, 143, 1215–1227. [CrossRef]

- Geisinger, M.A.; Risius, B.; Jordan, M.L.; Zelch, M.G.; Novick, A.C.; George, C.R. Magnetic resonance imaging of renal transplants. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1984, 143, 1229–1234. [CrossRef]

- Kettritz, U.; Semelka, R.C.; Brown, E.D.; Sharp, T.J.; Lawing, W.L.; Colindres, R.E. MR findings in diffuse renal parenchymal disease. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1996, 6, 136–144. [CrossRef]

- Semelka, R.C.; Corrigan, K.; Ascher, S.M.; Brown, J.J.; Colindres, R.E. Renal corticomedullary differentiation: observation in patients with differing serum creatinine levels. Radiology 1994, 190, 149–152. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Kozawa, E.; Okada, H.; Inukai, K.; Watanabe, S.; Kikuta, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Takenaka, T.; Katayama, S.; Tanaka, J.; et al. Noninvasive evaluation of kidney hypoxia and fibrosis using magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1429–1434. [CrossRef]

- Mathys, C.; Blondin, D.; Wittsack, H.J.; Miese, F.R.; Rybacki, K.; Walther, C.; Holstein, A.; Lanzman, R.S. T2’ Imaging of Native Kidneys and Renal Allografts - a Feasibility Study. Rofo 2011, 183, 112–119. [CrossRef]

- Schley, G.; Jordan, J.; Ellmann, S.; Rosen, S.; Eckardt, K.U.; Uder, M.; Willam, C.; Bäuerle, T. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of experimental chronic kidney disease: A quantitative correlation study with histology. PLoS One 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.; An, J.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Jin, Z. Texture analysis based on quantitative magnetic resonance imaging to assess kidney function: a preliminary study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2021, 11, 1256–1270. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Huang, C.; Fan, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Song, Z.; Zhi, N.; Ding, J. Application of MR Imaging Features in Differentiation of Renal Changes in Patients With Stage III Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy and Normal Subjects. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Grzywińska, M.; Jankowska, M.; Banach-Ambroziak, E.; Szurowska, E.; Dębska-Ślizień, A. Computation of the Texture Features on T2-Weighted Images as a Novel Method to Assess the Function of the Transplanted Kidney: Primary Research. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 2062–2066. [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Nagawa, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Inoue, K.; Funakoshi, K.; Inoue, T.; Okada, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Kozawa, E. The utility of texture analysis of kidney MRI for evaluating renal dysfunction with multiclass classification model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14776. [CrossRef]

- Majos, M.; Klepaczko, A.; Szychowska, K.; Stefanczyk, L.; Kurnatowska, I. Texture Analysis of T2-Weighted Images as Reliable Biomarker of Chronic Kidney Disease Microstructural State. Biomed. 2025, Vol. 13, Page 1381 2025, 13, 1381. [CrossRef]

- Le Bihan, D.; Iima, M. Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging: What Water Tells Us about Biological Tissues. PLOS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002203. [CrossRef]

- Taouli, B.; Koh, D.M. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the liver. Radiology 2010, 254, 47–66. [CrossRef]

- Javid, M.; Mirdamadi, A.; Javid, M.; Keivanlou, M.H.; Amini-Salehi, E.; Norouzi, N.; Abbaspour, E.; Alizadeh, A.; Joukar, F.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F.; et al. The evolving role of MRI in the detection of extrathyroidal extension of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhen, J.; Wang, R.; Cai, S.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Q. Chronic kidney disease: pathological and functional assessment with diffusion tensor imaging at 3T MR. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 652–660. [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, P.; Yaǧci, A.B.; Dursun, B.; Herek, D.; Fenkçi, S.M. Renal diffusion-weighted imaging in diabetic nephropathy: correlation with clinical stages of disease. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2014, 20, 374–378. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Sharma, R.; Bhalla, A.; Gamanagatti, S.; Seth, A. Diffusion-weighted MRI in assessment of renal dysfunction. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2012, 22, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.F.; Gaggioli, E.; Ricci, V.; Mazzei, F.; Mazzei, M.A.; Volterrani, L. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of renal function: a preliminary study. Radiol. Med. 2007, 112, 1201–1210. [CrossRef]

- Yalçin-Şafak, K.; Ayyildiz, M.; Ünel, S.Y.; Umarusman-Tanju, N.; Akça, A.; Baysal, T. The relationship of ADC values of renal parenchyma with CKD stage and serum creatinine levels. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2016, 3, 8–11. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Di, J.; Xing, W. Assessment of renal dysfunction with diffusion-weighted imaging: comparing intra-voxel incoherent motion (IVIM) with a mono-exponential model. Acta Radiol. 2016, 57, 507–512. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Chen, T.W.; Zhang, X.M. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Acute Kidney Injury: Present Status. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yan, F. Diffusion-weighted imaging in assessing renal pathology of chronic kidney disease: A preliminary clinical study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2014, 83, 756–762. [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Geng, L.; Lu, F.; Chen, C.; Jiang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, M.; Sun, B.; et al. Utilization of the corticomedullary difference in magnetic resonance imaging-derived apparent diffusion coefficient for noninvasive assessment of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xiao, W.; Li, X.; He, J.; Huang, X.; Tan, Y. In vivo evaluation of renal function using diffusion weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging in type 2 diabetics with normoalbuminuria versus microalbuminuria. Front. Med. 2014, 8, 471–476. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.P.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, J.; Bai, X.; Li, L.; Guo, H.P.; Ning, X.Y.; Zhang, X.J.; et al. Assessment of the Added Value of Intravoxel Incoherent Motion Diffusion-Weighted MR Imaging in Identifying Non-Diabetic Renal Disease in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 59, 1593–1602. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A.A.K.A.; Al-Adlany, M.A.A.A.; Alhadidy, A.M.; Atwa, M.A.; Abdou, N.E.A. Diffusion tensor imaging of the renal cortex in diabetic patients: correlation with urinary and serum biomarkers. Abdom. Radiol. (New York) 2017, 42, 1493–1500. [CrossRef]

- Lupica, R.; Mormina, E.; Lacquaniti, A.; Trimboli, D.; Bianchimano, B.; Marino, S.; Bramanti, P.; Longo, M.; Buemi, M.; Granata, F. 3 Tesla-Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: The Nephrologist’s Point of View. Nephron 2016, 134, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Caroli, A.; Villa, G.; Brambilla, P.; Trillini, M.; Sharma, K.; Sironi, S.; Remuzzi, G.; Perico, N.; Remuzzi, A. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging for kidney cyst volume quantification and non-cystic tissue characterisation in ADPKD. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 6009–6019. [CrossRef]

- Suwabe, T.; Ubara, Y.; Ueno, T.; Hayami, N.; Hoshino, J.; Imafuku, A.; Kawada, M.; Hiramatsu, R.; Hasegawa, E.; Sawa, N.; et al. Intracystic magnetic resonance imaging in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: features of severe cyst infection in a case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2016, 17, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Bs, P.W.; Bs, J.Z.; Ms, Y.T.; et al. Functional Evaluation of Transplanted Kidneys with Reduced Field-of-View Diffusion-Weighted Imaging at 3T. Korean J. Radiol. 2018, 19, 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging for predicting kidney allograft function decline: comparison with clinical parameters. Insights Imaging 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zöllner, F.G.; Ankar Monssen, J.; Rørvik, J.; Lundervold, A.; Schad, L.R. Blood flow quantification from 2D phase contrast MRI in renal arteries using an unsupervised data driven approach. Z. Med. Phys. 2009, 19, 98–107. [CrossRef]

- Steeden, J.A.; Muthurangu, V. Investigating the limitations of single breath-hold renal artery blood flow measurements using spiral phase contrast MR with R-R interval averaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 41, 1143–1149. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.B.; Santos, J.M.; Hargreaves, B.A.; Nayak, K.S.; Sommer, G.; Hu, B.S.; Nishimura, D.G. Rapid measurement of renal artery blood flow with ungated spiral phase-contrast MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2005, 21, 590–595. [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet (London, England) 2012, 379, 165–180. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.J.; Murphy, T.P.; Cutlip, D.E.; Jamerson, K.; Henrich, W.; Reid, D.M.; Cohen, D.J.; Matsumoto, A.H.; Steffes, M.; Jaff, M.R.; et al. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Binkert, C.A.; Debatin, J.F.; Schneider, E.; Hodler, J.; Ruehm, S.G.; Schmidt, M.; Hoffmann, U. Can MR measurement of renal artery flow and renal volume predict the outcome of percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty? Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2001, 24, 233–239. [CrossRef]

- Binkert, C.A.; Hoffman, U.; Leung, D.A.; Matter, H.G.; Schmidt, M.; Debatin, J.F. Characterization of renal artery stenoses based on magnetic resonance renal flow and volume measurements. Kidney Int. 1999, 56, 1846–1854. [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, S.O.; Knopp, M. V.; Londy, F.; Krishnan, S.; Zuna, I.; Lang, N.; Essig, M.; Hawighorst, H.; Maki, J.H.; Stafford-Johnson, D.; et al. Morphologic and functional magnetic resonance imaging of renal artery stenosis: a multireader tricenter study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.J.; Berthusen, A.; Vigers, T.; Schafer, M.; Browne, L.P.; Bjornstad, P. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate in a pediatric population using non-contrast kidney phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2023, 38, 2877–2881. [CrossRef]

- Michaely, H.J.; Schoenberg, S.O.; Ittrich, C.; Dikow, R.; Bock, M.; Guenther, M. Renal disease: value of functional magnetic resonance imaging with flow and perfusion measurements. Invest. Radiol. 2004, 39, 698–705. [CrossRef]

- Khatir, D.S.; Pedersen, M.; Jespersen, B.; Buus, N.H. Evaluation of Renal Blood Flow and Oxygenation in CKD Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66, 402–411. [CrossRef]

- Spithoven, E.M.; Meijer, E.; Borns, C.; Boertien, W.E.; Gaillard, C.A.J.M.; Kappert, P.; Greuter, M.J.W.; van der Jagt, E.; Vart, P.; de Jong, P.E.; et al. Feasibility of measuring renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 683–692. [CrossRef]

- Kline, T.L.; Edwards, M.E.; Garg, I.; Irazabal, M. V.; Korfiatis, P.; Harris, P.C.; King, B.F.; Torres, V.E.; Venkatesh, S.K.; Erickson, B.J. Quantitative MRI of kidneys in renal disease. Abdom. Radiol. (New York) 2018, 43, 629–638. [CrossRef]

- King, B.F.; Torres, V.E.; Brummer, M.E.; Chapman, A.B.; Bae, K.T.; Glockner, J.F.; Arya, K.; Felmlee, J.P.; Grantham, J.J.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; et al. Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow as a marker of disease severity in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 2214–2221. [CrossRef]

- Pruijm, M.; Milani, B.; Burnier, M. Blood oxygenation level-dependent mri to assess renal oxygenation in renal diseases: Progresses and challenges. Front. Physiol. 2017, 7, 240378. [CrossRef]

- Neugarten, J. Renal BOLD-MRI and assessment for renal hypoxia. Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 613–614. [CrossRef]

- van der Bel, R.; Coolen, B.F.; Nederveen, A.J.; Potters, W. V.; Verberne, H.J.; Vogt, L.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Paul Krediet, C.T. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Derived Renal Oxygenation and Perfusion During Continuous, Steady-State Angiotensin-II Infusion in Healthy Humans. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Milani, B.; Pruijm, M.; Kohn, O.; Sprague, S.; Hack, B.; Prasad, P. Renal BOLD MRI in patients with chronic kidney disease: comparison of the semi-automated twelve layer concentric objects (TLCO) and manual ROI methods. MAGMA 2020, 33, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Inoue, T.; Kozawa, E.; Ishikawa, M.; Shimada, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Tanaka, J.; Okada, H. Reduced oxygenation but not fibrosis defined by functional magnetic resonance imaging predicts the long-term progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2020, 35, 964–970. [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, E.A.; Fain, S.B.; Alford, S.K.; Korosec, F.R.; Fine, J.; Muehrer, R.; Djamali, A.; Hofmann, R.M.; Becker, B.N.; Grist, T.M. Assessment of acute renal transplant rejection with blood oxygen level-dependent MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology 2005, 236, 911–919. [CrossRef]

- Niles, D.J.; Artz, N.S.; Djamali, A.; Sadowski, E.A.; Grist, T.M.; Fain, S.B. Longitudinal Assessment of Renal Perfusion and Oxygenation in Transplant Donor-Recipient Pairs Using Arterial Spin Labeling and Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest. Radiol. 2016, 51, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Djamali, A.; Sadowski, E.A.; Samaniego-Picota, M.; Fain, S.B.; Muehrer, R.J.; Alford, S.K.; Grist, T.M.; Becker, B.N. Noninvasive assessment of early kidney allograft dysfunction by blood oxygen level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging. Transplantation 2006, 82, 621–628. [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Xiao, W.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J. The significance of BOLD MRI in differentiation between renal transplant rejection and acute tubular necrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2008, 23, 2666–2672. [CrossRef]

- Gloviczki, M.L.; Keddis, M.T.; Garovic, V.D.; Friedman, H.; Herrmann, S.; McKusick, M.A.; Misra, S.; Grande, J.P.; Lerman, L.O.; Textor, S.C. TGF expression and macrophage accumulation in atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 546–553. [CrossRef]

- Abumoawad, A.; Saad, A.; Ferguson, C.M.; Eirin, A.; Woollard, J.R.; Herrmann, S.M.; Hickson, L.T.J.; Bendel, E.C.; Misra, S.; Glockner, J.; et al. Tissue hypoxia, inflammation, and loss of glomerular filtration rate in human atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 948–957. [CrossRef]

- Chrysochou, C.; Mendichovszky, I.A.; Buckley, D.L.; Cheung, C.M.; Jackson, A.; Kalra, P.A. BOLD imaging: a potential predictive biomarker of renal functional outcome following revascularization in atheromatous renovascular disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2012, 27, 1013–1019. [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.; Herrmann, S.M.S.; Eirin, A.; Ferguson, C.M.; Glockner, J.F.; Bjarnason, H.; McKusick, M.A.; Misra, S.; Lerman, L.O.; Textor, S.C. Phase 2a Clinical Trial of Mitochondrial Protection (Elamipretide) During Stent Revascularization in Patients With Atherosclerotic Renal Artery Stenosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Kosaka, N.; Fujiwara, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Tsuchida, T.; Tsuchiyama, K.; Oyama, N.; Kimura, H. Arterial Transit Time-corrected Renal Blood Flow Measurement with Pulsed Continuous Arterial Spin Labeling MR Imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 2017, 16, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R.B.; Frank, L.R.; Wong, E.C.; Siewert, B.; Warach, S.; Edelman, R.R. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn. Reson. Med. 1998, 40, 383–396. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Shim, W.H.; Yoon, S.K.; Oh, J.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Jung, H.; Matsuda, T.; Kim, D. Measurement of arterial transit time and renal blood flow using pseudocontinuous ASL MRI with multiple post-labeling delays: Feasibility, reproducibility, and variation. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2017, 46, 813–819. [CrossRef]

- Pi, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, C.; Li, G.; Wen, H.; Peng, H.; Wang, J. Arterial spin labeling and diffusion-weighted MR imaging: quantitative assessment of renal pathological injury in chronic kidney disease. Abdom. Radiol. (New York) 2023, 48, 999–1010. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Artunc, F.; Martirosian, P.; Schlemmer, H.P.; Schick, F.; Boss, A. Histogram analysis of renal arterial spin labeling perfusion data reveals differences between volunteers and patients with mild chronic kidney disease. Invest. Radiol. 2012, 47, 490–496. [CrossRef]

- Gillis, K.A.; McComb, C.; Patel, R.K.; Stevens, K.K.; Schneider, M.P.; Radjenovic, A.; Morris, S.T.W.; Roditi, G.H.; Delles, C.; Mark, P.B. Non-Contrast Renal Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Assess Perfusion and Corticomedullary Differentiation in Health and Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 2016, 133, 183–192. [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Garcia-Fernandez, N.; Slon Roblero, M.F.; Páramo, J.A.; Escalada, F.J.; Wang, D.J.J.; Benito, A.; Fernández-Seara, M.A. Arterial spin labeling MRI is able to detect early hemodynamic changes in diabetic nephropathy. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2017, 46, 1810–1817. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Tan, H.; Thacker, J.M.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Kohn, O.; Sprague, S.M.; Prasad, P. V. Evaluation of Renal Blood Flow in Chronic Kidney Disease Using Arterial Spin Labeling Perfusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Kidney Int. reports 2017, 2, 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Ding, Y.; Ding, X.; Fu, C.; Cao, B.; Kuehn, B.; Benkert, T.; Grimm, R.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, M. Capability of arterial spin labeling and intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging to detect early kidney injury in chronic kidney disease. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 3286–3294. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.J.; Maki, J.H. Non-contrast-enhanced MR imaging of renal artery stenosis at 1.5 tesla. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2009, 17, 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Fenchel, M.; Martirosian, P.; Langanke, J.; Giersch, J.; Miller, S.; Stauder, N.I.; Kramer, U.; Claussen, C.D.; Schick, F. Perfusion MR imaging with FAIR true FISP spin labeling in patients with and without renal artery stenosis: initial experience. Radiology 2006, 238, 1013–1021. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Tong, X.Y.; Ning, Z.H.; Wang, G.Q.; Xu, F.B.; Liu, J.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Sun, Z.H.; Zhao, X.H.; et al. A preliminary study of renal function for renal artery stenosis using multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom. Radiol. (New York) 2025, 50. [CrossRef]

- Artunc, F.; Rossi, C.; Boss, A. MRI to assess renal structure and function. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2011, 20, 669–675. [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Janka, R.; Schmid, A.; Titze, S.; Ditting, T.; Sobotka, P.A.; Veelken, R.; Uder, M.; Schmieder, R.E. Vascular and renal hemodynamic changes after renal denervation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 1195–1201. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.; Meik, R.; Pravdivtseva, M.S.; Langguth, P.; Gottschalk, H.; Sedaghat, S.; Jüptner, M.; Koktzoglou, I.; Edelman, R.R.; Kühn, B.; et al. Non-contrast preoperative MRI for determining renal perfusion and visualizing renal arteries in potential living kidney donors at 1.5 Tesla. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Wen, C.L.; Chen, L.H.; Xie, S.S.; Cheng, Y.; Fu, Y.X.; Oesingmann, N.; de Oliveira, A.; Zuo, P.L.; Yin, J.Z.; et al. Evaluation of renal allografts function early after transplantation using intravoxel incoherent motion and arterial spin labeling MRI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2016, 34, 908–914. [CrossRef]

- Cutajar, M.; Hilton, R.; Olsburgh, J.; Marks, S.D.; Thomas, D.L.; Banks, T.; Clark, C.A.; Gordon, I. Renal blood flow using arterial spin labelling MRI and calculated filtration fraction in healthy adult kidney donors Pre-nephrectomy and post-nephrectomy. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 2390–2396. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Cheng, D.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Ni, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Wen, J. Perfusion and oxygenation in allografts with transplant renal artery stenosis: Evaluation with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Clin. Transplant. 2022, 36. [CrossRef]

- Radovic, T.; Jankovic, M.M.; Stevic, R.; Spasojevic, B.; Cvetkovic, M.; Pavicevic, P.; Gojkovic, I.; Kostic, M. Detection of impaired renal allograft function in paediatric and young adult patients using arterial spin labelling MRI (ASL-MRI). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Wan, J.; Tian, Y.; Wu, P.; Xu, R.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, L.; Zhu, M. Arterial spin labeling combined with T1 mapping for assessment of kidney function and histopathology in patients with long-term renal transplant survival after kidney transplantation. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 2415–2425. [CrossRef]

| T1 | T2 | DWI | PC-MRI | BOLD | ASL | ||

| CKD | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Kidney transplant | + | + | + | - | + | + | |

| CKD in policystic kidney disease | - | + | + | + | - | - | |

| Renal artery stenosis | Monitoring | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Qualification to revascularisation | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| MRI sequence | Possible application |

| T1 | Assessing renal structure, fibrosis, oedema, corelation with GFR |

| T2 | Assessing renal structure, oedema, hypoxia, corelation with GFR |

| DWI | Estimation of fibrosis and oedema, corelation with GFR |

| PC-Contrast | Estimation of RBF, corelation with GFR |

| BOLD | Detection of oxygenation, estimation of RBF |

| ASL | Tissue perfusion, estimation of RBF, corelation with GFR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).