Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Literature Review

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Experiments and Sample Preparation

3. Results

3.1. Chemical and Thermal Tests

3.2. Chloride Ion Penetration Test

3.3. Physico-Mechanical Tests

3.3.1. Soil Classification Tests and Moisture Content

3.3.2. Unconfined Compressive Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ubi, S.E., Nyah, E.D. & Agbor, R.B., 2022. Determination of mechanical properties of sandcrete block made with sand, polystyrene, laterite and cement. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Management (IJAEM) [online]. Available online: https://ijaem.net/issue_dcp/Determination%20of%20Mechanical%20Properties%20of%20Sandcrete%20Block%20Made%20With%20Sand,%20Polystyrene,%20Laterite%20and%20Cement.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Daily Post Nigeria, 2015. Governor Ortom pledges to revive Taraku Mills, others. Daily Post Nigeria [online]. Available online: https://dailypost.ng/2015/06/20/governor-ortom-pledges-to-revive-taraku-mills-others/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Daily Trust, 2023. Encounter with Benue burnt brick makers. Daily Trust [online]. Available online: https://dailytrust.com/encounter-with-benue-burnt-brick-makers/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Tse, T.A., 2012. Comparative evaluation of fired and unfired clay bricks in Benue. Journal of Building Materials, 8(2), pp.101–109.

- Day, R.L., 1990. Pozzolans for use in low-cost housing in developing countries. In: Malhotra, V.M. ed., Supplementary Cementing Materials for Concrete. Ottawa: Canadian Government Publishing Centre, pp.241–268.

- ASTM C618, 2023. Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International.

- Ayininuola, G.M. & Adekitan, T.O., 2016. Development of kaolinite as supplementary cementitious material by thermal activation. Journal of King Saud University – Engineering Sciences, 31(2), pp.174–181.

- Amah, A.N., Ejeh, S.P. & Lawal, A.A., 2011. Pozzolanic activity of selected clay samples in Nigeria. Journal of Engineering and Technology, 6(2), pp.77–84.

- Shi, C., 2001. Activator types and mechanisms of alkaline activation of slag. Cement and Concrete Research, 31(5), pp.741–748.

- Mette, K. & Emmanuel, O.S., 2019. Chemical and mechanical activation of uncalcined kaolinitic clays for cementitious applications. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 31(4), p.04019017.

- Okigbo, C.C. & Gana, M., 2017. Evaluation of locally made burnt bricks in compliance with building code standards. Nigerian Journal of Construction Technology and Management, 3(1), pp.22–29.

- Olawuyi, B.J., Babatunde, O.S. & Bolarinwa, A.K., 2013. Assessment of pozzolanic activities of selected clay samples for potential use in cement production. Nigerian Journal of Technology, 32(1), pp.93–100.

- Ameh, S., 2016. Benue to hand over moribund Otukpo bricks to investors. Premium Times [online], 12 August. Available online: www.premiumtimesng.com (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Minke, G., 2005. Building with Earth: Design and Technology of a Sustainable Architecture. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Geiker, M.R. & Gallucci, E., 2019. Reactivity of clay-based supplementary cementitious materials: Overview and gaps in knowledge. Cement and Concrete Research, 124, p.105807.

- Applied Testing and Geosciences LLC, 2024. Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs): A Guide for Sustainable Construction. Applied Testing and Geosciences LLC Publications.

- Feng, M., He, C. & Zhang, X., 2004. Mineralogical characterization of natural pozzolans. Cement and Concrete Research, 34(5), pp.869–872.

- Justice, J.M. & Kurtis, K.E., 2007. Characterization of cementitious materials using SEM techniques. Cement and Concrete Composites, 29(2), pp.142–145.

- Neville, A.M., 2011. Properties of Concrete. 5th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

- Alujas, A., Fernández, R., Skibsted, J. & Steger, S., 2015. Fast determination of pozzolanic activity using electrical conductivity and colorimetry. Cement and Concrete Composites, 64, pp.17–24.

- Pinheiro, A., Toledo Filho, R.D., Köhler, C. & Silva, I., 2023. Multi-scale assessment of pozzolanic reactivity: Bridging the gap in SCM testing. Construction and Building Materials, 370, p.130731.

- Elsen, J., Van Balen, K. & Van Gemert, D., 2011. Hydration reactions in hydraulic lime mortars: The role of additives. Cement and Concrete Research, 41(12), pp.1234–1242.

- Sherwood, P., 1993. Soil Stabilization with Cement and Lime. London: HMSO/Transport Research Laboratory.

- Makusa, G.P., 2012. Soil Stabilization Methods and Materials in Engineering Practice: State of the Art Review. Luleå University of Technology, Sweden.

- Iorfa, T.F., Iorfa, K.F., McAsule, A.A. & AKaayar, M.A., 2020. Extraction and characterization of nanocellulose from rice husk. International Journal of Applied Physics (IJAP), 7(1). Available online: https://www.internationaljournalssrg.org/IJAP/2020/Volume7-Issue1/IJAP-V7I1P117.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Moussa, M., Carminati, M., Borghi, G., Demenev, E., Gugiatti, M., Pepponi, G., Crivellari, M., Ficorella, F., Ronchin, S., Zorzi, N., Borovin, E., Lutterotti, L. & Fiorini, C., 2022. 32-channel silicon strip detection module for combined X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and X-ray diffractometry analysis. Frontiers in Physics, 10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2022.910089/full (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Dodson, V.H., 1990. Concrete Admixtures. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Mitchell, J.K. & Soga, K., 2005. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Balan, E., Fritsch, E., Allard, T. & Calas, G., 2007. Inheritance vs. neoformation of kaolinite during lateritic soil formation: A case study in the middle Amazon basin. Clays and Clay Minerals, 55(3), pp.253–259. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1346/CCMN.2007.0550303 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Beauvais, A. & Bertaux, J., 2002. In situ characterization and differentiation of kaolinites in lateritic weathering profiles using infrared microspectroscopy. Clays and Clay Minerals, 50(3), pp.314–330. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/DE825374356C9BFBAA50EA9C495198FB/S0009860400023892a.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

| Parameter | Minimum Value (Peak No.) |

Maximum Value (Peak No.) |

|---|---|---|

| 2θ (°) | 12.33 ± 0.05 (Peak 1) | 50.08 ± 0.03 (Peak 5) |

| d-spacing (Å) | 1.8200 ± 0.0009 (Peak 5) | 7.17 ± 0.03 (Peak 1) |

| Height (cps) | 291 ± 28 (Peak 5) | 2770 ± 164 (Peak 4) |

| FWHM (°) | 0.155 ± 0.013 (Peak 4) | 0.88 ± 0.11 (Peak 2) |

| Integrated Intensity (cps·°) | 58 ± 23 (Peak 5) | 905 ± 62 (Peak 2) |

| Integral Width (°) | 0.20 ± 0.10 (Peaks 4 and 5) | 1.9 ± 0.3 (Peak 2) |

| Asymmetry | 0.5 ± 0.8 (Peak 5) | 1.5 ± 0.7 (Peak 4) |

| Decay (nL/mL) | 0.0 ± 0.2 (Peak 5) | 1.55 ± 0.16 (Peaks 2 and 3) |

| Decay (nH/mH) | 0.0 ± 0.17 (Peak 5) | 1.55 ± 0.18 (Peaks 2 and 3) |

| Crystallite Size (Å) | 95 ± 12 (Peak 2) | 549 ± 45 (Peak 4) |

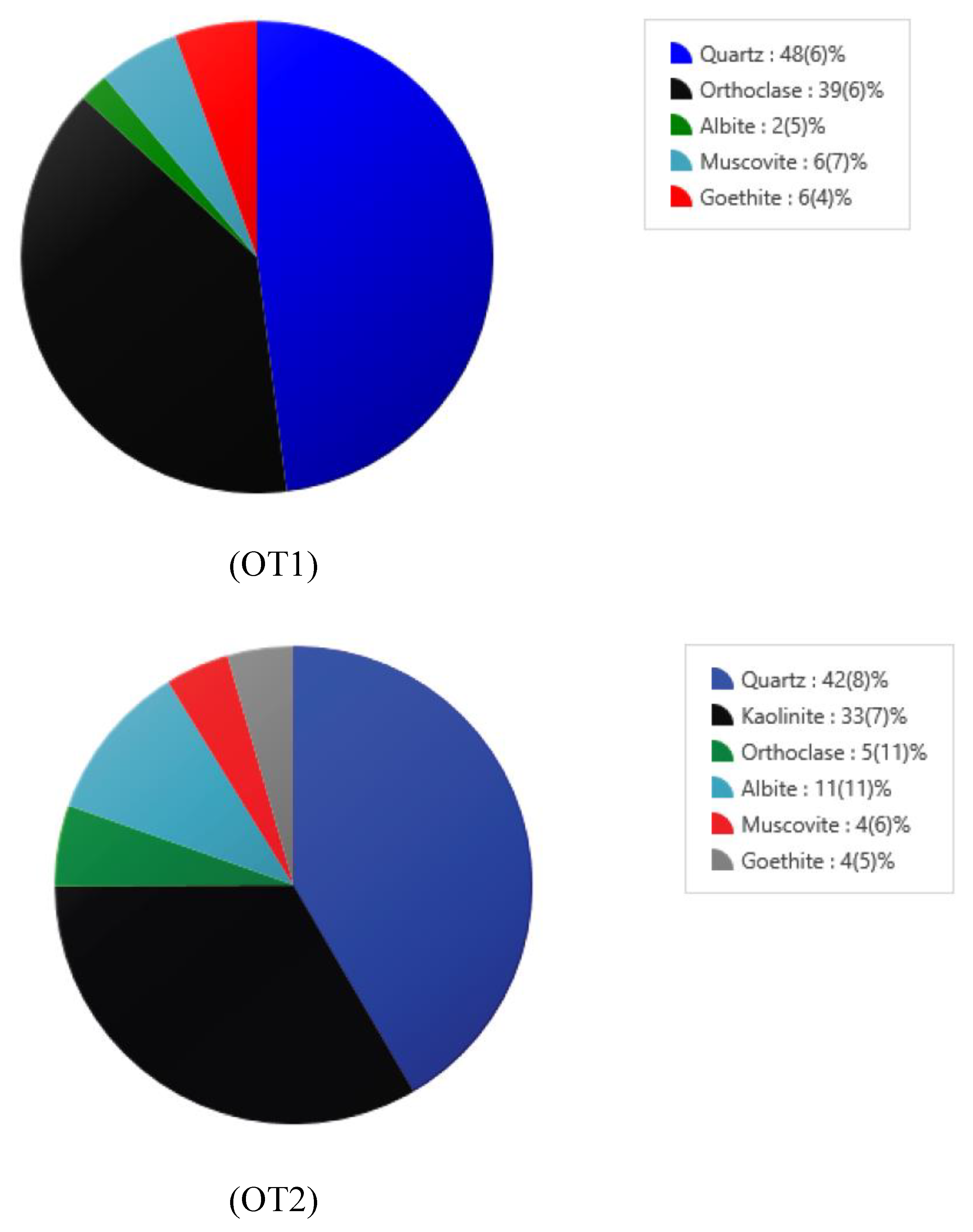

| Sample | Quartz (%) | Albite (%) | Orthoclase (%) | Goethite (%) | Muscovite (%) | Kaolinite (%) | Calcite (%) | Alite (%) |

| OT1 | 48 | 2 | 39 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OT2 | 42 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| SOKCEM 11-42.5N | 13.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.3 | 67.1 |

| Elements/Chemical Components | OT1 (wt.%) | SOKCEM 11-42.5N (wt.%) |

| O | 44.645 | 32.68 |

| Mg/MgO | 0.424 / 0.375 | 0 |

| Al/Al2O3 | 10.697 / 23.208 | 3.029/5.724 |

| Si/SiO2 | 23.827 / 48.567 | 5.181/11.085 |

| P/P2O5 | 0.106 / 0.046 | 0 |

| S/SO3 | 0.096 / 0.166 | 0.923/2.304 |

| Cl | 0.825 / 0.717 | 1.327/0 |

| K/K2O | 4.529 / 0.887 | 0.421/0.507 |

| Ca/CaO | 1.580 / 0.407 | 52.076/72.864 |

| Ti/TiO2 | 1.669 / 2.740 | 0.248/0.414 |

| V/V2O5 | 0.085 / 0.179 | 0.044/0.079 |

| Cr/Cr2O3 | 0.012 / 0.044 | 0.003/0.005 |

| Mn/MnO | 0.228 / 0.041 | 0.122/0.157 |

| Fe/Fe2O3 | 11.004 / 22.007 | 3.308/4.729 |

| Co/CoO | 0.042 / 0.081 | 0.035/0.044 |

| Ni/NiO | 0.009 / 0.000 | 0.004/0.005 |

| Cu/CuO | 0.042 / 0.049 | 0.03/0.037 |

| Zn/ZnO | 0.019 / 0.007 | 0.012/0.015 |

| Rb/Rb2O | 0.238 / 0.040 | 0.007/0.008 |

| Sr/SrO | 0.046 / 0.094 | 0.047/0.056 |

| Zr/ZrO2 | 0.238 / 0.148 | 0.048/0.065 |

| Nb/Nb2O5 | 0.047 / 0.021 | 0.021/0.03 |

| Ag/Ag2O | 0.000 / 0.000 | 0/0 |

| Sn/SnO2 | 0.000 / 0.000 | 0.395/0.501 |

| Ba/BaO | 0.068 / 0.000 | 0/0 |

| Ta/Ta2O5 | 0.018 / 0.033 | 0.017/0.021 |

| W/WO3 | 0.003 / 0.000 | 0.008/0.01 |

| Pb/PbO | 0.014 / 0.036 | 0.007/0.007 |

| S + A + F | 93.782 |

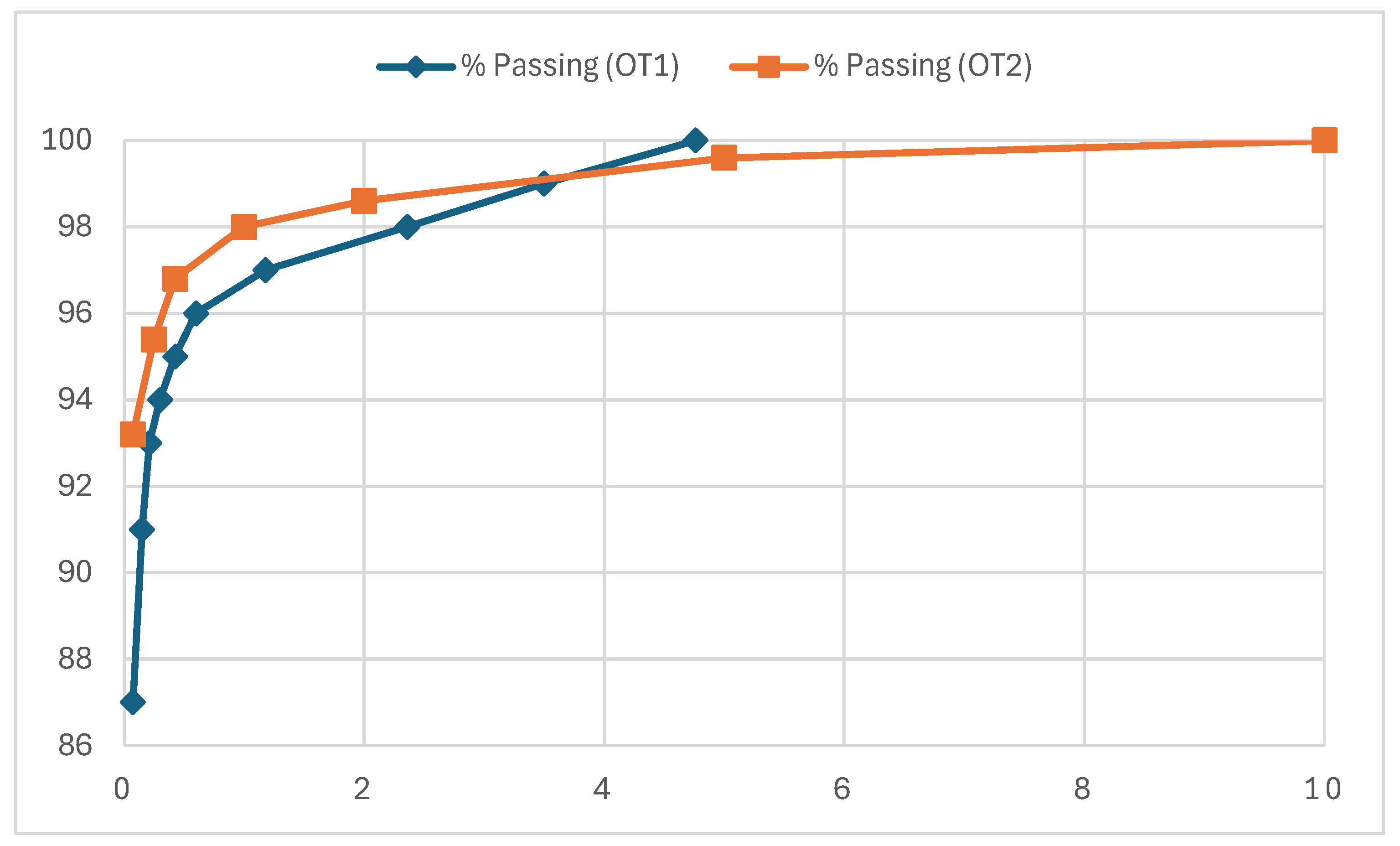

| Sieve size (mm) | OT1 (Passing %) | OT2 (Passing %) |

| 0.075 | 87 | 93.2 |

| 0.15 | 91 | - |

| 0.212 | 93 | - |

| 0.25 | - | 95.4 |

| 0.3 | 94 | - |

| 0.425 | 95 | 96.8 |

| 0.6 | 96 | - |

| 1.0 | - | 98 |

| 1.18 | 97 | - |

| 2.0 | - | 98.6 |

| 2.36 | 98 | - |

| 4.76 | 100 | - |

| 5.0 | - | 99.6 |

| 10.0 | - | 100 |

| Sample | LL (%) | PL (%) | PI (%) | LS (%) | MDD (g/cm3) | OMC (%) | USCS classification |

| OT1 | 72 | 26 | 46 | 14 | 1.69 | 22 | CH (Fat Clay) |

| Curing Period | Natural (kPa) | 5% NaOH (kPa) | 10% NaOH (kPa) | 5% Cement (kPa) | 10% Cement (kPa) |

| 7 Days | 73 | 75 | 99 | 153 | 104 |

| 14 Days | 87 | 72 | 105 | 240 | 338 |

| 28 Days | 96 | 122 | 153 | 512 | 796 |

| Days | 0% (Natural) (kPa) | 5% NaOH (kPa) | 10% NaOH (kPa) | 5% Cement (kPa) | 10% Cement (kPa) |

| 7 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 800 | 1000 |

| 14 | 100 | 300 | 500 | 1100 | 1300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).