1. Introduction

Archaeology is the science that investigates and studies the culture of people through the material remains and structures of the past, constituting one of the most fascinating fields of research. The preservation and study of cultural heritage is one of humanity’s most significant tasks, as it enables future generations to comprehend their historical identity and transmits knowledge of the past to the future. The relationship between modern individuals and archaeology is close and undeniable, as it serves as a primary source of information about the past, the way of life of people, and their achievements, helping to understand the evolution that has taken place over time and the events of the past [

1]. Archaeology is a multifaceted science, and it is difficult to fully define with a single definition, as its goals and functions continuously evolve over the years. A general definition is that archaeology is the humanistic science that aims to reconstruct and understand the near or distant, ancient human life by studying the material remains of human activity discovered during excavations [

2,

3]. According to [

4], archaeology seeks to interpret the conditions under which people acted and lived in the past, both in local and broader historical societies, and to promote historical knowledge and empathy.

In recent decades, significant technological advancement has offered new possibilities and innovative solutions, enhancing research accessibility and efficiency, with robotics occupying a central position in archaeological investigations. As a rapidly developing branch of the sciences, it contributes to a new era in archaeological science by supporting and evolving archaeological practices.

The term ’robotics’ refers to the branch of technology that focuses on the conception, design, development, and subsequent operation of a robot. It is a modern field of technology that studies the design and execution of the tasks performed by a robot and conducts research for its further development. Robotics integrates a variety of sciences, primarily computer science, mechanical engineering, and electronics, which collaborate to create a new synthetic science that deals with the exchange of information and energy between a machine and the environment in which it operates, aiming toward a specific set of objectives [

5].

The connection of robotics with archaeology is not only a technological innovation but also an attempt to overcome the limitations of traditional methods, as robots are used in various tasks, such as exploring inaccessible areas, mapping underwater, subterranean, or challenging archaeological sites, and collecting data with accuracy and speed. New possibilities provided by robotics, such as 3D scanning, autonomous vehicles, photogrammetry, and augmented reality (AR), can usher in a new era for archaeology and lead to unprecedented levels of documenting cultural achievements.

The methodology followed in this study is based on a combinatorial approach, ensuring a multidimensional analysis of the subject and projecting a comprehensive view of robotics’ contribution to the science of archaeology. It includes the following components:

Literature Review: The primary source of scientific material examined in this study is the collection and study of articles published in the press and online, as well as scientific books that present the applications of robotics both in archaeological investigation and in the museum space. The goal was not to include all possible articles found, but to provide a good understanding of this multi-disciplinary area.

Case Studies Analysis: For this study, a number of characteristic case studies are examined to highlight the significance of using robots in archaeological research. The selection of these specific cases was made based on the innovative use of robotic technology in each case, solving archaeological issues in a pioneering way, and the importance of each robotic system in archaeological research.

2. Archaeology and Technology

Archaeology, as a science, has traditionally been associated with physical research, as its primary tool is excavation, through which material remnants are uncovered, aiding in the study of human civilization. The way archaeologists today discover, record, and interpret findings has shown remarkable improvement, as technology has contributed to the advancement of archaeological science. In many cases, traditional methods are still employed, such as using a journal for daily documentation of excavation processes and findings, manual drawing, and manual excavation techniques by specialized workers. Although these methods remain of great importance and have been the foundation of excavation research for centuries, they have several disadvantages, such as being time-consuming, costly, and lacking the precision provided by modern tools and the latest technological methods.

The contribution of technology to the development and evolution of archaeology is truly remarkable, as its introduction into this field has facilitated improvements and solutions to various problems arising from the exclusive use of traditional methods. Archaeology and technology, converging at excavation sites, work together in recording, preserving, and analyzing archaeological findings and data, ultimately leading to their interpretation.

2.1. Technologies

More specifically, the cutting-edge technologies applied in archaeology today include (

Figure 1):

Lidar Technology (Light Detection and Ranging): Initially used in meteorology [

6], Lidar has brought significant changes to archaeological research over the past two decades by enabling high-speed topographic mapping. It is a sensor that measures variations in the ground and creates three-dimensional maps, identifying archaeological sites that would otherwise remain undetected [

7].

Geographic Information Systems (GIS): GIS are digital tools that allow the identification of archaeological sites through the statistical analysis of digital images combined with archaeological and environmental information [

8].

Three-Dimensional Modeling (3D Modeling): This is an advanced form of digitization aimed at three-dimensional documentation of archaeological sites and objects. The most widely used method is laser scanning, but depending on the case and the desired outcome, other techniques such as shape from structured light, shape from stereo imaging, shape from photometry, photogrammetry, and field laser scanning are also employed [

9,

10]. The benefits of 3D modeling in cultural heritage are numerous, including digital documentation of archaeological findings, public access to 3D archaeological objects via the internet, and the creation of accurate replicas for educational purposes or for conservation, aiding in the restoration and completion of broken fragments [

11].

Augmented reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR): AR/VR technologies enable immersive visualization of archaeological sites, allowing researchers to reconstruct and explore ancient structures in 3D, and offer virtual site tours. AR/VR can transform how cultural heritage is studied and preserved.

Figure 1.

Technologies used in Archaeology

Figure 1.

Technologies used in Archaeology

2.2. Categories of Robots

As previously mentioned, robots are devices designed to perform preprogrammed tasks, perceive their environment, and can be categorized as follows:

Fixed-base robots - This type consists of links—solid bodies that form a kinematic chain. One end is attached to a fixed base in space, which connects to the other links through joints. These joints enable movement and can be classified based on their degrees of freedom as rotary, prismatic, or spherical.

-

Mobile Robots - These robots can move in space using wheels, propellers, rotors, or mechanical legs. Mobile robots are further classified based on their mode of movement and degree of autonomy:

Wheeled Autonomous Robots - These robots move using wheels and possess a high degree of autonomy. They do not require continuous supervision and are capable of executing high-level commands.

Legged Robots: These robots use mechanical legs for movement. Unlike wheeled robots, they can more easily navigate uneven terrain and overcome obstacles.

Aerial Robots (UAVs and Drones) - These are flying, unmanned robots capable of continuous flight and performing predefined tasks without direct operator control. They may operate autonomously or be remotely controlled from the ground. In recent years, significant research progress has been made in this area [

12].

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) - These are unmanned underwater robots used in industries such as oil, gas, and mineral exploration, as well as subsea geotechnical surveys [

13]. They are known for their flexibility, with sizes ranging from small observation units to large systems capable of complex operations. Advantages of ROVs include unlimited operational time (since they are powered by a surface vessel), the ability to access areas unsafe for divers, and detailed seabed inspections [

14]. However, limitations include restricted movement due to the tether cable, challenges operating in strong currents, and difficulty in very shallow waters.

3. Applications of Robotics in Archaeology

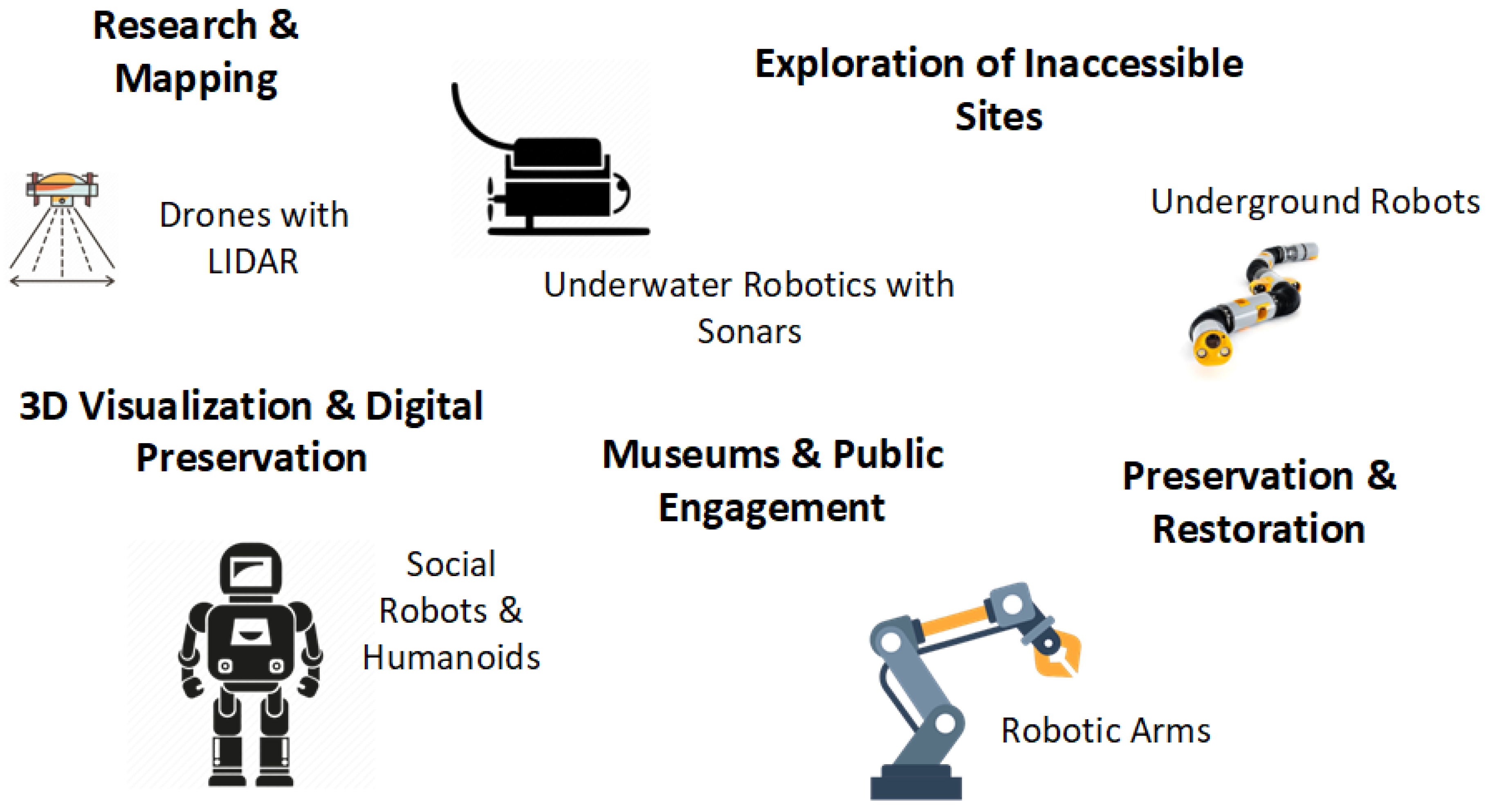

An emerging interdisciplinary field at the intersection of Archaeology and Robotics has gained significant attention in recent years, aiming to explore, study, and preserve cultural monuments and archaeological findings uncovered through excavations (

Figure 2). This important collaboration between the humanities and engineering enables the adaptation of technological solutions to the specific needs of archaeological research and fieldwork, while also contributing to the preservation and sustainable management of cultural heritage [

15]. Robotics applications, in particular, have introduced new capabilities for mapping, visualization, and in-depth analysis of archaeological sites. Notable innovations include the use of drones and 3D imaging technologies, which—both individually and in combination—support the creation of interactive tools and promote a deeper, broader understanding of cultural heritage.

New technologies are being developed and applied within a dynamic framework that brings together novel theoretical approaches with technical knowledge and innovation. This synergy promotes the sustainable management of cultural heritage.

3.1. Research and Mapping

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, have become an essential tool in archaeology, offering topographic mapping and aerial photography capabilities for archaeological sites. Mapping an archaeological area is typically costly and time-consuming; however, drones equipped with high-resolution cameras and sensors (such as LiDAR, multispectral cameras, and other detection equipment) can collect data that enables detailed documentation of cultural heritage [

16,

17]. Drones provide a variety of advantages:

Fast and Cost-Effective Mapping

In terms of speed and cost-efficiency, drones can rapidly collect data while significantly reducing the expenses associated with such tasks. Traditional aerial photography methods require the use of airplanes or satellites, which provide high-resolution imagery at a high cost and often with long wait times. In contrast, drones can map large archaeological areas in a short amount of time and at a cost-effective scale, making them suitable even for limited budgets [

18,

19].

Access to Remote Areas

Drones offer accessibility to remote and difficult-to-reach locations where ground methods are impractical [

16]. Many excavations occur in areas with challenging access, rugged terrain, dense vegetation, or even hazards, and numerous archaeological sites are located in geographically demanding environments, such as deserts or mountainous regions [

20]. The ability of drones to fly at low altitudes and collect data from multiple angles provides a unique opportunity to monitor archaeological sites that are otherwise inaccessible using traditional methods [

21]. Furthermore, in cases of natural disasters such as earthquakes or floods, drones can reach hazardous or obstructed areas to document the condition of archaeological monuments without putting researchers at risk [

16].

Photogrammetry and Digital Models

One revolutionary application of drones in archaeology is the creation of digital models via photogrammetry, enabling new approaches in recording and analyzing archaeological sites [

22]. Photogrammetry involves capturing a series of images from different angles, which are then processed with specialized software to produce high-resolution and detailed 3D digital models. These models help in studying site geometry and monitoring wear over time, accurately documenting both ancient structures and their surrounding environment.

Combining Drones and LiDAR

Field surveys and archaeological excavations are crucial for uncovering findings that, once interpreted, can provide significant insights into historical contexts. In recent years, modern methods have been introduced to address the limitations of past approaches in surveying even the most inaccessible areas. Accurate topographic diagrams and precise recording of movable artifacts during excavations are critical for identifying their differences and contextual relationships [

23,

24].

Mobile mapping systems have revolutionized archaeological site documentation by collecting high-precision data, capturing large-scale details, and producing 3D models while reducing the time and cost of traditional geospatial measurements [

25]. Advancements in ground-based surveys now allow for the accurate collection of large datasets through UAV technology and the integration of LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging).

LiDAR emits laser pulses that detect objects and simultaneously measure their distance from the sensor. Drones, due to their compact size and mobility, are easily deployable and can scan ground surfaces equipped with LiDAR. The laser pulses reflect off surfaces, return to the sensor, and are recorded as point data [

26]. When combined with GIS (Geographic Information Systems), LiDAR point clouds are processed to analyze and manage large geospatial datasets, aiding in pattern recognition, spatial modeling, and creating high-value maps [

27,

28].

LiDAR can reveal what optical cameras cannot: hidden archaeological structures beneath vegetation or the earth’s surface [

16]. This non-invasive technique uncovers archaeological sites and features that would otherwise remain invisible using traditional methods [

29]. To conduct a LiDAR-equipped drone survey, post-processing data analysis and visualization is requried [

30].

3.2. Exploring Robotics in Archaeology

Robotic technology is one of the most valuable tools in archaeology, as it aids in the exploration of areas that would typically be difficult or impossible for scientists and researchers to access. These areas include caves, underground tombs, narrow tunnels, and sites that have suffered from collapse. Robots can gather data with the highest accuracy, increasing the efficiency of archaeological research, reducing risks to researchers, and providing useful information without disturbing the surrounding environment [

31,

32].

Robots for Underground Excavations

A new and innovative approach to exploring underground excavations involves the use of robots, which offers several advantages compared to traditional methods [

33]. Robots used in subterranean structures are equipped with advanced technologies such as acoustic sensors, 3D imaging, and LiDAR, enabling precise mapping of spaces [

34]. Specifically, LiDAR allows for the accurate reconstruction of 3D models of areas, even in low-light environments with insufficient natural illumination [

26]. The paper titled [

35] presents the development of a compact, articulated hexapod robot named A-RHex, designed to assist archaeologists in the initial exploration of underground tombs. Its small size and articulated design enable navigation through narrow and complex terrains, facilitating safe and efficient pre-exploration of archaeological sites.

Penetration of Narrow Passages and Caves

A challenging aspect of archaeological research is the exploration of narrow passages, caves, and generally inaccessible areas, where the use of robotics represents a truly innovative approach [

36]. The rapid development of robotics provides safe access to narrow pathways, unstable rocks, and areas with limited visibility that are impossible for researchers to visit. Furthermore, the use of micro-robots or coordinated swarms of robots [

37] opens up new possibilities for analysis in extremely tight spaces and irregular surfaces, mapping and analyzing areas where prehistoric wall paintings and other high-archaeological significance findings may exist, with minimal environmental disturbance [

38,

39].

Robots in Underwater Archaeology

AUVs, in contrast, operate without a physical connection to the surface [

40]. Both ROVs [

41,

42] and AUVs [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] are widely used in underwater archaeological missions. Other works also explore

bimanual humanoid underwater robots with articulated arms [

48] and

modular AUVs equipped with manipulation arms [

49] for complex underwater tasks. Additionally, multi-AUV collaboration has been investigated in the context of marine archaeological missions [

50,

51,

52]. Also, in [

53] a biomimetic robotic fish (Robofish) is used underwater archaeological tasks, while in [

54] a autonomous surface vehicle (ASV) is employed. These robotic systems are deployed in diverse environments—from

Mediterranean shipwrecks [

48], to

deep-water surveys in Trondheim Harbour [

42], and

cistern system mapping in Malta [

43]. Also, to support their missions, these robots integrate a variety of sensors, as summarized in

Table 1.

3.3. 3D Visualization of Archaeological Sites

AI-powered robots can detect, record, and identify components of archaeological artifacts, facilitating the creation of digital archives and 3D models [

55,

56]. In particular, 3D scanning and modeling technologies have been widely used to create interactive models that revolutionizes documentation, study, and preservation practices of monuments, even in remote or inaccessible areas [

57]. This technology involves the use of equipment such as laser scanners, drones with photogrammetry capabilities, and 3D modeling software. Digital technologies also support the creation of virtual tours, augmented reality (AR) representations, and applications that reconstruct the original appearance of monuments, contributing to both the preservation and dissemination of cultural knowledge [

58]. Through these digital reconstructions, visitors can explore these sites remotely, thus increasing public access and offering a new dimension in understanding history. Furthermore, integrating such tools into museums and educational programs enhances cultural education and public awareness [

59].

3.4. Preservation and Restoration

Robotics is increasingly being applied in the fields of preservation and restoration of fragile archaeological findings as well as the maintenance of archaeological sites. This represents an innovative and interdisciplinary field, combining both the humanities and technological sciences.

Applications of Robotics in Conservation and Restoration

Environmental factors such as air pollution, climate change, and the passage of time accelerate the decay of heritage monuments—especially those exposed to open air. Materials of historical structures, including temples, ancient theaters, façades, and marble sculptures, are particularly vulnerable. Traditional cleaning and maintenance techniques often involve significant risk of human-induced damage. Therefore, the deployment of advanced robotic technologies and specialized systems has become a necessity, offering safer, more effective, and less invasive conservation approaches.

Robotic systems automate a wide range of tasks that enhance the efficiency and precision of artifact restoration. These systems reduce the time required for such tasks and are capable of performing delicate, specialized interventions on fragile objects, ancient frescoes, and mosaics. Human intervention in highly sensitive archaeological materials is minimized, while robotic tools offer researchers improved accuracy and control. These specialized tools can be tailored to the needs of individual artifacts [

60].

For example, robotic arms equipped with sensors can analyze materials such as metals, frescoes, sculptures, and ceramics in detail, without compromising their integrity—thereby reducing the risk of human error [

61]. This emerging field focuses on the development of robots specifically designed for preserving sensitive surfaces on-site, such as monuments, and for handling ancient artifacts from excavation areas. These robots provide safe, precise, and effective methods, minimizing the risk of further deterioration caused by manual handling. For example, [

62] presents a service robot designed to assist in the analysis, surveying, and restoration of fresco paintings. The robot integrates advanced sensing and manipulation capabilities to perform delicate tasks, minimizing the risk of damage to the artwork. [

63] highlights the ROVINA project, which utilizes AI-driven robotics to digitally document and preserve cultural heritage in environments like the catacombs of Priscilla in Rome and San Gennaro in Naples. [

64] explores the application of robotic technologies in the preservation of cultural heritage, with a specific focus on the Bini artifacts in Nigeria.

Robotics in the Retrieval and Analysis of Archaeological Finds

One of the most significant developments in archaeological robotics is the retrieval of artifacts from inaccessible or difficult-to-reach areas. Through the use of computer vision, sensors, and cameras, robotic systems can capture and analyze sequences of images to study archaeological finds and ancient remains without the risk of physical damage.

Additionally, during excavations, archaeologists often encounter large quantities of fragments—such as pottery sherds (“ostraka”), bones, and other materials—that require substantial time and expertise to classify and document. Due to practical constraints, these items are often selectively recorded. This process can be automated using a database that aids in the recognition of fragments through image analysis from portable devices. The artifacts are then categorized by size, shape, decoration, material composition, and level of degradation. The RePAIR project [

65] uses AI, robotics, and computer vision to automate the retrieval, analysis, and reconstruction of fragmented archaeological finds. It enables large-scale restoration of artifacts like vases and frescoes, making cultural heritage more accessible by drastically reducing manual effort and time.

Safeguarding Cultural Heritage

Robotics also plays a critical role in safeguarding cultural heritage, particularly in monuments located in disaster-prone, hazardous, or hard-to-reach regions. Equipped with environmental sensors, robots can detect changes in temperature and humidity, enabling early identification of material degradation and the implementation of preventive conservation measures [

66].

3.5. Robots in Cultural Institutions and Museums

Robotic technology is emerging as a key driver of intelligent transformation in the museum sector and, more broadly, in the domain of cultural heritage. The integration of robots into museum environments represents a genuine innovation that enhances both the accessibility and educational experience of visitors. Robots can provide guided information about exhibits, improving visitor engagement, while also supporting essential tasks related to the preservation, restoration, and protection of museum collections.

Robots capable of interacting, communicating, and collaborating with humans are often referred to as

social robots, and their operation may be either fully or partially autonomous [

67]. In the museum context, a social robot is not merely an information transmitter guiding and informing visitors, but also a medium for creating novel, interactive tour experiences that differ significantly from traditional museum methods such as labels and static visual aids. [

68] presents the MuseBot project, highlighting the integration of robotics and informatics to develop strategic solutions for enhancing museum experiences. [

69] discusses the integration of semantic information retrieval systems in robotic museum guides to enhance user interaction and information accessibility. [

70] CiceRobot, a cognitive robotic system designed to guide museum visitors, enhancing their experience through interactive tours. [

71] discusses the deployment of the telepresence robot "Virgil" to enhance museum accessibility and visitor engagement through remote exploration. [

72] explores the integration of robotic avatars in museum settings to enhance visitor engagement and provide innovative telepresence experiences.

According to [

73], five essential features are required for effectively integrating a robot into a museum environment:

Social navigation: The robot must adapt its movement within the museum space by recognizing human presence and responding appropriately.

Perception: Using its cameras and sensors, the robot can detect visitors’ movements. Through visual capabilities, it understands the environment and human actions—for example, identifying a visitor’s interest in an exhibit when they stop or approach it.

Speech: The social robot is equipped with verbal communication capabilities, transforming the museum visit into an engaging and interactive experience. As a guide, it provides tailored information based on the visitor’s age—offering simplified answers for children and more complex responses for adults. Speech is also used for directions, personalized suggestions, and storytelling about exhibits.

Gestures (non-verbal cues): Some museum robots are equipped with gesture sensors that allow them to mimic visitor movements, further enriching the interactive experience.

Combination of skills and behavior generation: By combining the above four capabilities, the robot can adopt different behaviors that provide an optimal visitor experience in museums and cultural spaces.

While the use of robots and artificial intelligence in museums significantly enhances visitor experience and promotes innovation, several challenges must be addressed. Robots entail high development, installation, and maintenance costs, posing a financial burden, especially for smaller cultural institutions [

74]. In noisy environments, robots may struggle to adapt and interact effectively with visitors, often failing to respond to more specialized questions, thus limiting their educational value [

75]. Furthermore, some museum visitors, particularly older individuals who are less familiar with technology, tend to prefer human interaction and guidance. Excessive reliance on technological systems in museums may reduce interpersonal communication between visitors and staff, thereby diminishing the human dimension of the museum experience [

76]. Lastly, concerns have been raised regarding the protection of personal data. Robots equipped with sensors and cameras collect a large volume of information, raising privacy and data protection issues [

77].

4. Case Studies: Applications of Robotics in Archaeology

This section presents case studies of robotic applications drawn from both international and Greek archaeology. The selected examples were chosen based on criteria such as their contribution to the understanding and protection of cultural heritage, their level of technological innovation, and their geographical diversity. Based on these criteria, a comprehensive picture can be formed regarding the usefulness of robotics in the field of archaeology.

Each case study involves an analysis of the technologies used, the outcomes achieved, the challenges encountered, and the conclusions drawn regarding the future prospects of robotic technologies. The key aspects addressed in each case are as follows:

Application context: The condition of the archaeological site before the implementation of robotic tools and the challenges that were being faced.

Description of the technology: The technological tools and methods employed in each case study.

Results of the robotic application: The achievements and discoveries that emerged, and how they contributed to the scientific understanding of the archaeological site.

Challenges and limitations: The problems encountered during the application of robotic technology and whether they were resolved or remain unsolved.

Lessons learned and future impact: The most important lessons derived from each case and their expected influence on future robotic applications in archaeology.

| Application |

Special Features / Differentiators |

|

Exploration of the Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt |

|

|

Underwater exploration of the submarine volcano Kolumbo (Santorini) |

|

|

Mapping and monitoring archaeological sites (e.g., Pompeii) |

High-precision sensor data collection Access to hazardous or hard-to-reach areas Site preservation support |

|

Smithsonian National Museum of American History |

|

|

Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki |

Participates in treasure hunt games for children Provides museum information via portable devices Educational and entertainment goals |

|

San Antolín Cathedral (Palencia, Spain) |

|

|

Notre-Dame Cathedral |

Digital twin and 3D model creation Real-time structural data monitoring Robotic analysis of ceramic findings |

|

Analysis of ancient ceramics from excavations [78] |

Digital archiving and classification Comparison with known collections Faster, safer ceramic analysis |

|

Mapping archaeological site of Wombwell Wood |

Non-invasive structure detection in dense vegetation Fast, large-area, high-resolution 3D mapping GIS integration |

|

Archaeological mapping in Amazon Jungle |

Dense jungle penetration using LiDAR AI-powered autonomous UAV navigation Sensor fusion (thermal, GIS) for 3D reconstruction Minimal environmental impact |

4.1. Robotic Exploration of the Great Pyramid: The Djedi Project

The purpose and construction method of the Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Pyramid of Khufu) have sparked numerous unanswered questions since antiquity and remain a key subject of global archaeological research. As the largest pyramid on the Giza Plateau and the only surviving wonder of the ancient world, it holds immense cultural significance [

79].

Robotics has enabled exploration of previously inaccessible areas within the pyramid. In the so-called Queen’s Chamber, a narrow shaft was discovered hidden behind a false wall. Unlike other shafts intended for ventilation, this one served no known functional purpose and was too narrow for human entry.

To explore it, the

Djedi robot was developed in 2011 by a team at the University of Leeds, led by engineer Rob Richardson [

80]. The robot was designed to navigate inclined surfaces and confined spaces while collecting detailed data without damaging the structure. It featured:

An 8-mm micro snake camera capable of detailed imaging,

A 360-mm drill for piercing small obstacles (e.g., stone blocks),

Miniature sensors for precision data acquisition.

4.2. The Use of Robots at the Archaeological Site of Pompeii

Pompeii, a city in Southern Italy, was founded in the 8

th century BCE in a renowned location with an exceptional climate, making it the most famous resort of the Roman Empire. Wealthy Romans built country villas there, decorated with significant artistic creations, and the city flourished, reaching a population of around 20,000–30,000. On August 24, 79 CE, the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried the city under volcanic ash, rock, and successive layers of lava up to seven meters thick. Extensive archaeological excavations have revealed public buildings, affluent Roman villas adorned with unique frescoes, numerous temples—most notably those of Apollo and Isis—fountains, the small and large theater, and the Forum, the city’s central marketplace and commercial hub [

81].

The integration of innovative technologies, such as robotics, in Pompeii has proven particularly effective for archaeological research, site management, conservation, study, and the protection of one of the most important archaeological sites globally.

The Capabilities of the Quadruped Robot SPOT

In addition to the aforementioned findings, spaces with limited accessibility and structural instability have been uncovered, posing challenges for exploration due to collapse risks. Pompeii’s unique architecture, including its underground structures, presents difficulties for archaeologists in terms of both access and study. In Pompeii, robots are used as part of a multilevel monitoring strategy to inspect structures and terrain, helping assess damage, material decay, and structural stability, ultimately supporting data-driven decisions for efficient and resilient cultural heritage maintenance [

82].

The SPOT robot, a quadruped robotic dog developed by Boston Dynamics, offers a solution by safely and precisely mapping these areas. Weighing approximately 33 kilograms and equipped with 360° vision to avoid obstacles, SPOT can inspect confined spaces and collect valuable data for the study of Pompeii’s antiquities and the planning of future interventions [

83]. Moreover, it monitors the progress of restoration works with high efficiency. Thanks to its autonomy, SPOT can perform repetitive or time-consuming tasks more quickly and effectively. It is equipped with a LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) system for 3D mapping, and offers two operational modes: the Leica BLKARC sensor and the Spot CAM sensor, which help create 3D maps and provide critical data to archaeologists.

SPOT also contributes to the security and surveillance of the Pompeii site by conducting routine inspections to identify structural problems, signs of erosion and damage, or vandalism. Its onboard cameras detect movement and patrol visitor-accessible areas, deterring potential looters and inspecting underground tunnels dug by “tombaroli”—looters seeking valuable artifacts in the city’s ruins [

84].

Other Robotic Applications in Pompeii

Beyond SPOT, robotic systems have also supported the conservation of highly fragile finds such as frescoes and mosaic floors. The RePAIR project (Reconstructing the Past: Artificial Intelligence and Robotics meet Cultural Heritage), launched in 2011, utilizes AI and robotic arms to reassemble dispersed fragments [

85][

86]. This task is vital, as the robot accurately analyzes the surviving pieces, saving archaeologists significant time in what is otherwise a laborious process with uncertain outcomes.

RePAIR can also clean fragments without causing damage, allowing for the precise and effective restoration of artworks that would otherwise be difficult to reassemble. Robotic assistance is essential in preserving the historical heritage of Pompeii.

4.3. The Pepper Robot at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Most visitors to a museum or cultural venue expect to be surrounded by objects and works of art to admire from a distance. However, the Smithsonian Institution pioneered the use of robots in the museum environment, following its deployment of Minerva by introducing the Pepper robot, a 1.2-meter tall humanoid robot, to provide a novel interactive experience for its guests and to help solve common issues within the cultural institution.

Pepper played a supportive role in enhancing the museum experience for Smithsonian visitors, drawing the attention of individuals who had previously never or rarely visited the space. It also encouraged repeat attendance from frequent visitors and served as a helpful tool for educators leading school visits (Smithsonian Launches Pilot Program of “Pepper” Robots, 2018). Upon entry, Pepper greets guests using its built-in sensors, capturing the interest of younger audiences who are typically more engaged with technology.

Pepper is a speech-enabled robot capable of mimicking human expressions, perceiving and interacting with its environment, answering questions, and narrating stories. Since museums attract a diverse international audience, Pepper helps bridge language gaps with support for 21 different languages [

87]. Additionally, it features a touchscreen interface that enhances the interactive experience, appealing to visitors of all ages.

Leveraging artificial intelligence, Pepper detects when a visitor approaches and initiates engagement. In doing so, the Smithsonian improves the quality of the visitor experience while allowing museum staff to focus on more complex tasks [

88].

4.4. Social Robot in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki is the first cultural institution in Greece to use a robot to enhance its educational programs, making it a pioneer among Greek museums. It serves as an excellent example of the convergence of new technologies with culture, offering a modern approach to the museum experience while also reinforcing the museum’s educational and cultural mission. Utilizing artificial intelligence, the robot enables the integration of new technologies by storing information about the museum’s most important exhibits in its memory.

The robot was part of the innovative program “CultureID: The Internet of Culture – Integrating RFID Technology in the Museum,” which focused on digital transformation and employed RFID (Radio-Frequency Identification) robotic technology. Using simple language that is understandable by the general public, the social robot responds to visitors’ questions regarding the museum’s most popular archaeological artifacts. In this way, it provides immediate and interactive information, enhancing the museum’s educational role.

Furthermore, it participates in educational programs, enriching the experience for visitors of all ages. It is specifically designed to take part in games aimed at children, such as a riddle game in which young visitors are divided into teams and must search for clues throughout the museum. By using a portable device, participants can tell if they are near the correct location because the device emits a sound signal when they are close. Then, the players return to the robot’s position, submit their answer, and the game continues. The increased accessibility and friendly interaction make the robot approachable for visitors of all ages while simultaneously promoting interactivity throughout the spaces of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki [

89].

4.5. Use of Robotic Systems in the Restoration of Cathedrals – The Case of Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris is the most famous cathedral in the world, built in the 12th century and recognized as the most visited monument globally, with 14 million visitors annually. It measures 128 meters in length, features two bell towers 68 meters high, and is renowned for its sculptures and stained glass windows. The cathedral suffered significant damage during the French Revolution and was restored in the 19th century under the supervision of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose restoration efforts lasted 25 years [

90,

91] Despite expensive annual maintenance—costing the French government 2 million euros—the cathedral still exhibited considerable deterioration.

In April 2019, a massive fire broke out, severely damaging the monument. Additionally, lead from the bell tower was found to have contaminated the air and flooring, as confirmed by researchers [

92].

Drones (Figure 25) were employed to create a 3D model of the cathedral’s upper sections and roof, capturing billions of digital points to build a complete digital replica. This model was compared with earlier digital scans to aid in understanding, preserving, and restoring Notre-Dame (Figure 26). The reconstruction was particularly difficult due to the lack of restoration archives. A critical innovation was the development of a “digital twin”—a continuously updated 3D representation of the cathedral informed by sensor data, which allowed comparison of different temporal snapshots (Figure 27) [

93].

Artificial intelligence also played a vital role in the restoration of Notre-Dame. Through digital restoration techniques, restorers accessed archives and historical records that depicted the cathedral’s original appearance [

94]. The five-year restoration effort after the devastating fire benefited from AI, which helped recover original colors, textures, and structural details. A real-time monitoring system was crucial for assessing structural stability and enabling timely interventions.

4.6. Use of Robotic Systems in Archaeological Excavation and Documentation – The RASCAL System

During archaeological excavations, thousands of ceramic sherds are uncovered daily, serving as key chronological and cultural indicators. Traditional manual documentation of these fragments is time-consuming, prompting the need for automation. The RASCAL (Robotic Arm for Sherds and Ceramics Automated Locomotion) system, as presented by [

78], addresses this challenge through a robotic arm equipped with a camera and multiple data acquisition stations. It operates under varying lighting conditions and can weigh, photograph, and store data for each sherd with high accuracy—processing approximately 1,260 fragments per day. The system also supports semi-automated reassembly and 3D modeling of ancient vessels, thereby minimizing physical handling and reducing the risk of damage.

Despite the advantages of robotic integration in cultural heritage documentation—efficiency, precision, and preservation—certain limitations persist. High costs and technical expertise are required for deployment. According to [

95], data accessibility is another concern, as 3D datasets are often private and unavailable to the broader research or educational community. Additionally, virtual reality applications that accompany such robotic systems may prioritize technological presentation over archaeological context, potentially diminishing the cultural and educational value of the artifacts themselves.

4.7. Discovery of an Ancient Metropolis in the Amazon Jungle Using UAVs and LiDAR

As already noted in the case of Wombwell Wood, the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has emerged as a powerful tool in archaeological research, enabling both the discovery and mapping of hidden structures beneath dense vegetation. A remarkable initiative in the Amazon rainforest is the “Amazônia Revelada” project, led by Brazilian archaeologist Eduardo Góes Neves. Utilizing LiDAR technology, the project mapped nearly 1,600 square kilometers of forest, uncovering 30 archaeological sites, including geometric structures and an abandoned 18th-century Portuguese village [

96]. UAVs are, also, used for the identification of forest species in areas of forest regeneration in the Amazon because UAVs generally operate at low altitudes and can acquire images in better spatial resolutions than satellite images, providing more detailed information not only about the forest but also at the species level [

97].

LiDAR technology, integrated into UAVs, emits laser pulses that produce detailed 3D maps of the ground surface. This method enables the detection of archaeological features invisible to traditional techniques due to the dense foliage. Specifically, the LiDAR pulses penetrated the canopy, captured the ground’s topography, and revealed hidden features (Figure 32). In the Upano region of Ecuador, researchers identified 6,000 platforms—likely dwellings and ceremonial spaces—as well as an advanced urban planning system, including 25 kilometers of roads (Figure 33). The presence of defensive ditches suggests potential conflicts, while agricultural practices included maize cultivation and the fermentation of beverages.

Researchers also uncovered an extensive network of roads, canals, and plazas, pointing to a thriving society that existed over 2,500 years ago. LiDAR was first used in excavations in 2015, when Ecuador’s National Institute of Cultural Heritage funded the corresponding surveys. The mapping employed a non-destructive method that preserved both the archaeological remains and the Amazonian forest [

98]. The combination of UAV imagery, thermal sensors, and LiDAR allowed for a multi-layered data analysis, while geolocation and GIS (Geographic Information Systems) provided precise placement of archaeological sites for comparison with historical data and excavation optimization. There is case where UAVs equipped with both RGB and thermal sensors were employed to reveal features otherwise invisible at ground level, enabling the identification of built-up boundaries and facilitating reconstruction hypotheses of the urban structure[

99].

This groundbreaking discovery challenges the long-held belief that the Amazon was inhabited only by small, nomadic groups and instead reveals the presence of a complex and well-organized civilization, comparable to the Maya. Overall, the use of UAVs equipped with LiDAR technology and enhanced by artificial intelligence has revolutionized archaeological exploration in the Amazon, enabling the non-invasive discovery and documentation of hidden cultural treasures.

5. Conclusions: Scientific Challenges and Limitations of Robotics in Archaeology

The integration of robotic technology offers numerous possibilities and opportunities in the field of archaeology. Nevertheless, there are several challenges and limitations that arise in the processes of discovery, documentation, and preservation of archaeological findings. These technologies bring with them a range of constraints that must be taken into consideration.

Technological Limitations

Despite the progress made in robotics, robots face significant difficulties when operating in irregular and unpredictable environments such as archaeological sites. Navigation across uneven terrain requires advanced sensor systems and algorithms for obstacle avoidance and the execution of delicate tasks. However, such systems are not always available or reliable. One fundamental limitation is that robots must possess sufficient degrees of freedom to achieve high flexibility and successful navigation. As such, path planning must involve feasible trajectories that help avoid unexpected situations [

100].

Economic Limitations

Robotic systems used in archaeology represent a highly innovative practice that combines technological advancement with the need for careful and detailed study of cultural heritage. However, these systems are expensive to develop and maintain. Despite their advantages, the main challenge remains their high initial purchase and installation costs, especially in archaeological projects or small research institutions with limited budgets. Moreover, the investment in robotics requires specialized personnel, and the cost of their training adds further financial burden, increasing operational costs and expenses. Due to their high cost, robotic systems are produced in limited quantities, forcing institutions to evaluate their cost-effectiveness, which casts doubt on their economic viability [

101]. Thus, strategies must be explored that promote funding tools and support innovation in the field of archaeology.

Adaptability Limitations and Integration Challenges

The integration of robotics in archaeology requires effective interdisciplinary collaboration among archaeologists, computer scientists, and engineers, each of whom contributes essential knowledge and expertise. Effective communication channels are crucial to combine skills from each scientific field and ensure the successful implementation of robotic technologies. Archaeologists provide interpretation and evaluation of findings, computer scientists contribute to data processing and analysis, and engineers focus on developing and adapting robotic technologies for archaeological use [

102]. However, differences in priorities and misunderstandings between disciplines can undermine collaboration and reduce its effectiveness. Additionally, each archaeological site is unique, with specific environmental and contextual conditions, meaning robotic systems must offer customized solutions. This increases both the cost and the technical complexity of deployment.

Ethical and Social Limitations

While robotics offers new possibilities for discovery and conservation, it also raises ethical questions regarding the replacement of human labor and the loss of traditional skills. Automation can exclude the human dimension from excavation and data collection, reducing the involvement of archaeologists and potentially alienating cultural heritage [

103]. The deployment of robots in sensitive archaeological environments must be carefully considered, as there is a risk of unintentional damage or alteration of the landscape [

104]. Concerns also arise about the extent to which the integrity of archaeological finds is preserved and how technology might negatively affect traditional research methods.

References

- I. Hodder, Entangled. An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- C. Tryon, B. Pobiner, R. Kauffman, Archaeology and human evolution, Evolution: Education and Outreach 3 (2010) 377–386.

- C. Renfrew, P. G. Bahn, Archaeology: theories, methods and practice, Thames and Hudson, 1994.

- P. Barker, Techniques of Archaeological Excavation, 1st Edition, Routledge, 1993.

- D. Koditschek, What is robotics? why do we need it and how can we get it?, Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems 4 (1) (2021) 1–33.

- G. G. Goyer, R. Watson, The laser and its application to meteorology, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 44 (1963) 564–575.

- G. Vinci, F. Vanzani, A. Fontana, S. Campana, Lidar applications in archaeology: A systematic review, Archaeological Prospection 32 (1) (2025) 81–101.

- D. Wheatley, M. Gillings, Spatial technology and archaeology: the archaeological applications of GIS, CRC Press, 2013.

- C. A. Wallace, Refinement of retrospective photogrammetry: an approach to 3d modeling of archaeological sites using archival data, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 14 (10) (2022) 192.

- G. Pavlidis, A. Koutsoudis, F. Arnaoutoglou, V. Tsioukas, C. Chamzas, Methods for 3d digitization of cultural heritage, Journal of cultural heritage 8 (1) (2007) 93–98.

- A. Kantaros, P. Douros, E. Soulis, K. Brachos, T. Ganetsos, E. Peppa, E. Manta, E. Alysandratou, 3d imaging and additive manufacturing for original artifact preservation purposes: A case study from the archaeological museum of alexandroupolis, Heritage 8 (2) (2025) 80.

- C. Liew, D. De Latte, N. Takeishi, T. Yairi, Recent developments in aerial robotics: A survey and prototypes overview (2017) 1–14. https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/2adf5c564dbf1ef25507833c3acde6b4c197e721.

- F. Azis, M. Aras, M. Rashid, M. Othman, S. Abdullah, Problem identification for underwater remotely operated vehicle (rov): A case study, Procedia Engineering 41 (2012) 554–560.

- I. Patiris, Rov, remote operated vehicle (2015).

- C. Dallas, Digital humanities and archaeology: Theoretical perspectives, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 30 (2) (2015) 240–253. [CrossRef]

- S. Campana, Drones in archaeology: State-of-the-art and future perspectives, Archaeological Prospection 24 (4) (2017) 275–296. [CrossRef]

- A. Ulvi, Importance of unmanned aerial vehicles (uavs) in the documentation of cultural heritage, Turkish Journal of Engineering 4 (3) (2020) 104–112.

- J. I. Fiz, P. M. Martín, R. Cuesta, E. Subías, D. Codina, A. Cartes, Examples and results of aerial photogrammetry in archeology with uav: Geometric documentation, high resolution multispectral analysis, models and 3d printing, Drones 6 (3) (2022) 59. [CrossRef]

- I. H. Beloev, A review on current and emerging application possibilities for unmanned aerial vehicles, Acta Technol. Agric 19 (3) (2016) 70–76.

- E. Adamopoulos, E. E. Papadopoulou, M. Mpia, E. Deligianni, G. Papadopoulou, D. Athanasoulis, M. Konioti, M. Koutsoumpou, C.-N. Anagnostopoulos, 3d survey and monitoring of ongoing archaeological excavations via terrestrial and drone lidar, ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences (2023) 3–10.

- D. Calderone, N. Lercari, D. Tanasi, D. Busch, R. Hom, R. Lanteri, Tackling the thorny dilemma of mapping southeastern sicily’s coastal archaeology beneath dense mediterranean vegetation: A drone-based lidar approach, Archaeological Prospection 32 (1) (2025) 139–158.

- G. J. Verhoeven, Taking computer vision aloft: archaeological three-dimensional reconstructions from aerial photographs with photoscan, Archaeological Prospection 18 (1) (2011) 67–73. [CrossRef]

- H. Abdel-Maksoud, Combining uav-lidar and uav-photogrammetry for bridge assessment and infrastructure monitoring, Arabian Journal of Geosciences 17 (4) (2024) 144.

- N. Camarretta, P. A. Harrison, A. Lucieer, B. M. Potts, N. Davidson, M. Hunt, From drones to phenotype: using uav-lidar to detect species and provenance variation in tree productivity and structure, Remote Sensing 12 (19) (2020) 3184.

- J. Fernández-Hernández, D. González-Aguilera, P. Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, J. Mancera-Taboada, Image-based modelling from unmanned aerial vehicle (uav) photogrammetry: An effective, low-cost tool for archaeological applications, Archaeometry 57 (1) (2015) 128–145. [CrossRef]

- R. Opitz, J. T. Herrmann, Recent trends and long-standing problems in archaeological remote sensing, Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology 1 (1) (2018) 19–41. [CrossRef]

- M. Doneus, C. Briese, M. Fera, M. Janner, Archaeological prospection of forested areas using full-waveform airborne laser scanning, Journal of Archaeological Science 35 (4) (2008) 882–893. [CrossRef]

- J. Schindling, C. Gibbes, Lidar as a tool for archaeological research: A case study, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 6 (4) (2014) 411–423. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Opitz, D. C. Cowley (Eds.), Interpreting Archaeological Topography: Airborne Laser Scanning, 3D Data and Ground Observation, Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2013.

- J. Casana, E. J. Laugier, A. C. Hill, K. M. Reese, C. Ferwerda, M. D. McCoy, T. Ladefoged, Exploring archaeological landscapes using drone-acquired lidar: Case studies from hawai’i, colorado, and new hampshire, usa, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 39 (2021) 103133. [CrossRef]

- A. Traviglia, R. Giovanelli, Robotics in archaeology: Navigating challenges and charting future courses, in: European Robotics Forum, Springer, 2024, pp. 362–367.

- J. Wang, X. Zhu, F. Tie, T. Zhao, X. Xu, Design of a modular robotic system for archaeological exploration, in: 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, IEEE, 2009, pp. 1435–1440.

- L. Tom, C. Cyprien, P.-E. Dossou, L. Gaspard, Towards a robotic intervention for on-land archaeological fieldwork in prehistoric sites, in: International Conference on Flexible Automation and Intelligent Manufacturing, Springer, 2023, pp. 79–90.

- M. Afrazi, K. Lee, Autonomous mapping and exploration of underground structures, in: Advancements in Underground Infrastructures, CRC Press, 2025, pp. 401–433.

- Q. Shao, Q. Xia, Z. Lin, X. Dong, X. An, H. Zhao, Z. Li, X.-J. Liu, W. Dong, H. Zhao, Unearthing the history with a-rhex: Leveraging articulated hexapod robots for archeological pre-exploration, Journal of Field Robotics 42 (1) (2025) 206–218. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/rob.22410. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang, B. Shang, Y. Chen, H. Moyes, Smartcavedrone: 3d cave mapping using uavs as robotic co-archaeologists, in: 2017 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), IEEE, 2017, pp. 1052–1057.

- M. Cüneyitoğlu, Swarm robotics and archaeology: A concepts paper, in: European Robotics Forum 2024: 15th ERF, Volume 2, Springer Nature, p. 357.

- T. Gramegna, L. Venturino, M. Ianigro, G. Attolico, A. Distante, Pre-historical cave fruition through robotic inspection, in: Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, IEEE, 2005, pp. 3187–3192.

- S. O’Donoghue, Culture re-view: A dog called robot discovers one of the most impressive examples of prehistoric art, accessed: 2025-05-25 (2023). https://www.euronews.com/culture/2023/09/12/culture-re-view-a-dog-called-robot-discovers-one-of-the-most-impressive-examples-of-prehis.

- D. R. Blidberg, The development of autonomous underwater vehicles (auv); a brief summary, in: Ieee Icra, Vol. 4, 2001, pp. 122–129.

- A. Gebaur, et al., Innovative technologies in underwater archaeology: Field experience, open problems, and research lines, Chemistry and Ecology (2006).

- D. McLaren, Cost-effective deep water archaeology: Preliminary investigations in trondheim harbour, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2000).

- J. G. Bellingham, et al., Archaeology via underwater robots: Mapping and localization within maltese cistern systems, Journal of Field Robotics (2010).

- D. Skarlatos, et al., Autonomy in marine archaeology, in: Proceedings of CAA2015, 2015.

- K. Demestichas, et al., Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: From simulation environments to real-world scenarios, Heritage 4 (4) (2021) 3081–3102.

- A. Gebaur, et al., The arrows project: Robotic technologies for underwater archaeology, in: OCEANS 2014 - TAIPEI, IEEE, 2014.

- . degård, R. E. Hansen, H. Singh, T. J. Maarleveld, Archaeological use of synthetic aperture sonar on deepwater wreck sites in skagerrak, Journal of Archaeological Science 89 (2018) 1–13.

- O. Khatib, et al., Ocean one: A robotic avatar for oceanic discovery, IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine 23 (4) (2016) 20–29.

- W. Zhang, et al., Design and application of a multifunctional exploration platform for robotic archaeology, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering (2023).

- N. Tsiogkas, et al., Facilitating multi-auv collaboration for marine archaeology, in: OCEANS 2015-Genova, IEEE, 2015, pp. 1–6.

- N. Tsiogkas, G. Papadimitriou, Z. Saigol, D. Lane, Efficient multi-auv cooperation using semantic knowledge representation for underwater archaeology missions, in: 2014 Oceans-St. John’s, IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–6.

- J. Wu, R. C. Bingham, S. Ting, K. Yager, Z. J. Wood, T. Gambin, C. M. Clark, Multi-auv motion planning for archeological site mapping and photogrammetric reconstruction, Journal of Field Robotics 36 (7) (2019) 1250–1269.

- S. Wang, et al., Experiment of robofish aided underwater archaeology, ROBOT 27 (2) (2005) 147–151.

- V. Kapetanović, et al., Assessing the current state of a shipwreck using an autonomous marine robot: Szent istvan case study, in: Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Special Sessions, 17th International Conference, Springer, 2019, pp. 111–118.

- M. Emami, Y. M. Emami, Y. Sakali, C. Pritzel, R. Trettin, Deep inside the ceramic texture: A microscopic–chemical approach to the phase transition via partial-sintering processes in ancient ceramic matrices, Journal of Microscopy and Ultrastructure 4 (1) (2016) 11–19.

- F. Cannella, M. Cannella, E. Fontana, R. Giovanelli, G. Marchello, P. Marciniak, Cultural heritage digital preservation through ai-driven robotics, in: The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Vol. XLVIII-M-2-2023, 2023, pp. 995–1000. https://isprs-archives.copernicus.org/articles/XLVIII-M-2-2023/995/2023/. [CrossRef]

- F. Remondino, S. Campana, 3D Recording and Modelling in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage: Theory and Best Practices, Archaeopress, Oxford, 2014.

- F. Bruno, S. Bruno, G. De Sensi, M. L. Luchi, S. Mancuso, M. Muzzupappa, From 3d reconstruction to virtual reality: A complete methodology for digital archaeological exhibition, Journal of Cultural Heritage 11 (1) (2010) 42–49.

- M. K. Bekele, R. Pierdicca, E. Frontoni, E. S. Malinverni, J. E. Gain, A survey of augmented, virtual, and mixed reality for cultural heritage, Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH) 11 (2) (2018) 1–36.

- T. R. Kurfess, et al., Robotics and automation handbook, Vol. 414, CRC press Boca Raton, FL, 2005.

- M. Cigola, A. Pelliccio, O. Salotto, G. Carbone, E. Ottaviano, M. Ceccarelli, et al., Application of robots for inspection and restoration of historical sites, in: Proceedings 22st International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Vol. 400, Università di Ferrara, 2005, pp. 1–6.

- M. Ceccarelli, G. Carbone, A. Messina, G. Quaglia, G. Vacca, A robotic solution for the restoration of fresco paintings, International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 12 (7) (2015) 1–10. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.5772/61757. [CrossRef]

- J. Serafin, M. Di Cicco, T. M. Bonanni, G. Grisetti, L. Iocchi, D. Nardi, C. Stachniss, V. A. Ziparo, Robots for exploration, digital preservation and visualization of archaeological sites, in: Artificial Intelligence for Cultural Heritage, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, pp. 121–140. https://iris.uniroma1.it/handle/11573/924699.

- H. U. M. Bazunu, P. A. Edo, C. O. Isiramen, P. O. O. Ottuh, Robotic intervention in preserving artifacts: The case of the bini cultural artifacts in nigeria, Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 17 (1) (2025) 1–10. https://rupkatha.com/V17/n1/v17n102.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Reconstructing the past: Artificial intelligence and robotics meet cultural heritage (repair), https://www.repairproject.eu/, horizon 2020 EU Research and Innovation Programme, Grant Agreement No. 964854 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. P. Pocobelli, J. Boehm, P. Bryan, J. Still, J. Grau-Bové, Bim for heritage science: a review, Heritage Science 6 (1) (2018) 1–15.

- M. Sarrica, S. Brondi, L. Fortunati, Social robots and the future of museum experiences, Journal of Human-Robot Interaction (2020).

- A. Gallozzi, G. Carbone, M. Ceccarelli, C. De Stefano, A. Scotto di Freca, M. Bianchi, M. Cigola, The musebot project: Robotics, informatic, and economics strategies for museums, in: Handbook of Research on Emerging Technologies for Digital Preservation and Information Modeling, IGI Global, 2016, pp. 1–20. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/the-musebot-project/165616. [CrossRef]

- G. Vassallo, A. Chella, G. Pilato, R. Sorbello, A semantic information retrieval in a robot museum guide application, in: Proceedings of the Workshop on Semantic Information Retrieval, 2005. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228793538.

- A. Chella, M. Liotta, I. Macaluso, Cicerobot: A cognitive robot for interactive museum tours, Industrial Robot: An International Journal 34 (6) (2007) 503–511. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/01439910710832101/full/html. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Lupetti, C. Germak, L. Giuliano, Robots and cultural heritage: New museum experiences, in: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts (EVA 2015), BCS Learning and Development Ltd., 2015, pp. 322–329. https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.14236/ewic/eva2015.36. [CrossRef]

- M. Roussou, P. E. Trahanias, G. Giannoulis, G. Kamarinos, A. Argyros, D. Tsakiris, P. Georgiadis, W. Burgard, D. Haehnel, A. B. Cremers, D. Schulz, M. Moors, E. Spirtounias, M. Marianthi, V. Savvaides, A. Reitelman, D. Konstantios, A. Katselaki, Experiences from the use of a robotic avatar in a museum setting, in: Proceedings of the 2001 Conference on Virtual Reality, Archaeology, and Cultural Heritage (VAST ’01), ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2001, pp. 153–160. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/584993.585017. [CrossRef]

- M. Hellou, et al., Robots in museum environments: Key features for effective integration, International Journal of Social Robotics (2022).

- M. Nikolaou, Economic challenges in the adoption of robotic technologies in cultural institutions, Heritage Technology Review (2024).

- G. Carignani, Limitations of social robots in noisy environments: A case study in interactive museums, Museum Innovation Studies (2021).

- A. Vermeeren, et al., Balancing technology and human touch in the museum experience, Museum Management and Curatorship (2018).

- C. Oruma, et al., Privacy concerns in human–robot interaction in public spaces, AI and Society (2023).

- D. Wang, B. Lutz, P. J. Cobb, P. Dames, Rascal: Robotic arm for sherds and ceramics automated locomotion, in: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 2021, pp. 6378–6384. [CrossRef]

- R. Richardson, et al., Exploration technologies for the great pyramid, Journal of Archaeological Robotics (2013).

- J. Liu, R. Richardson, Robotic access in confined heritage structures: the djedi robot, Heritage Science (2015).

- J. J. Dobbins, P. W. Foss, The world of Pompeii, Vol. 125, Routledge London, 2007.

- G. Zuchtriegel, A. Zambrano, V. Calvanese, A multilevel approach to monitor the archaeological park of pompeii, in: European Robotics Forum, Springer, 2024, pp. 351–356.

- J. Ouellette, Boston dynamics’ robot dog will help protect the ruins of pompeii, accessed: 2025-05-21 (2022). https://arstechnica.com/science/2022/04/boston-dynamics-robot-dog-will-help-protect-the-ruins-of-pompeii/.

- Pompeii Sites, Spot, a quadruped robot at the service of archaeology to inspect archaeological areas and structures in safety, https://pompeiisites.org/en/press-releases/spot-a-quadruped-robot-at-the-service-of-archaeology-to-inspect-archaeological-areas-and-structures-in-safety/, archaeological Park of Pompeii, Press Release (Mar. 2022).

- S. Bonomi, Detection and recognition of archaeological fragments to improve robotic artifact reconstruction (2023). https://unitesi.unive.it/handle/20.500.14247/24685.

- T. Dafoe, Archaeologists in italy are using a.i. robots to piece together ancient frescoes from fragments discovered at pompeii, accessed: 2025-05-21 (2023). https://news.artnet.com/art-world/archeologists-ai-robot-repair-pompeii-artwork-2262148.

- R. Elsakhry, et al., The technology of robots as one of the elements of automation in museums (museum of the future-smithsonian as a model),مجـلة کلية الآثـار بقنا جامعة جنوب الوادي19 (1) (2024) 1–17.

- D. Allegra, F. Alessandro, C. Santoro, F. Stanco, Experiences in using the pepper robotic platform for museum assistance applications, in: 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1033–1037.

- A. Dimitriou, S. Papadopoulou, M. Dermenoudi, A. Moneda, V. Drakaki, A. Malama, A. Filotheou, A. Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, A. Tzitzis, S. Megalou, et al., Exploiting rfid technology and robotics in the museum. zenodo, 7805387, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by peer community in archaeology (2024).

- F. Bandarin, The restoration and reconstruction of notre-dame of paris: A test for the profession, Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation History, Theory, and Criticism 17 (1) (2020) 97–110.

- P. Zachmann, O. de Châlus, Restoring Notre-Dame de Paris: Rebirth of the Legendary Gothic Cathedral, Schiffer+ ORM, 2023.

- O. Allal-Chérif, Intelligent cathedrals: Using augmented reality, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence to provide an intense cultural, historical, and religious visitor experience, Technological Forecasting and Social Change (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. Jacquot, R. Saleri, Gathering, integration, and interpretation of heterogeneous data for the virtual reconstruction of the notre dame de paris roof structure, Journal of cultural heritage 65 (2024) 232–240.

- O. Allal-Chérif, Intelligent cathedrals: Using augmented reality, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence to provide an intense cultural, historical, and religious visitor experience, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 178 (2022) 121604.

- Y. Ming, R. C. Me, J. K. Chen, R. W. O. K. Rahmat, A systematic review on virtual reality technology for ancient ceramic restoration, Applied Sciences 13 (15) (2023) 8991. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, L. Aragão, J. Iriarte, A uav–lidar system to map amazonian rainforest and its ancient landscape transformations, International journal of remote sensing 38 (8-10) (2017) 2313–2330.

- M. M. Moura, L. E. S. de Oliveira, C. R. Sanquetta, A. Bastos, M. Mohan, A. P. D. Corte, Towards amazon forest restoration: Automatic detection of species from uav imagery, Remote Sensing 13 (13) (2021) 2627.

- M. Rachini, Deep in the amazon, researchers have uncovered a complex of ancient cities using laser technology, accessed: 2025-01-22 (2024). https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/ancient-cities-amazon-1.7087760.

- J. Berni, P. Zarco-Tejada, L. Suárez, V. González-Dugo, E. Fereres, Remote sensing of vegetation from uav platforms using lightweight multispectral and thermal imaging sensors, Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inform. Sci 38 (6) (2009) 6.

- R. Siegwart, I. R. Nourbakhsh, D. Scaramuzza, Introduction to autonomous mobile robots, MIT press, 2011.

- D. Tsiafaki, N. Michailidou, Benefits and problems through the application of 3d technologies in archaeology: recording, visualisation, representation and reconstruction, Scientific culture 1 (3) (2015) 37–45.

- P. J. Cobb, J. H. Sigmier, P. M. Creamer, E. R. French, Collaborative approaches to archaeology programming and the increase of digital literacy among archaeology students, Open Archaeology 5 (1) (2019) 137–154.

- M. Ponti, A. Seredko, Human-machine-learning integration and task allocation in citizen science, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9 (1) (2022) 1–15.

- M. Fisher, M. Fradley, P. Flohr, B. Rouhani, F. Simi, Ethical considerations for remote sensing and open data in relation to the endangered archaeology in the middle east and north africa project, Archaeological Prospection 28 (3) (2021) 279–292.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).