1. Introduction

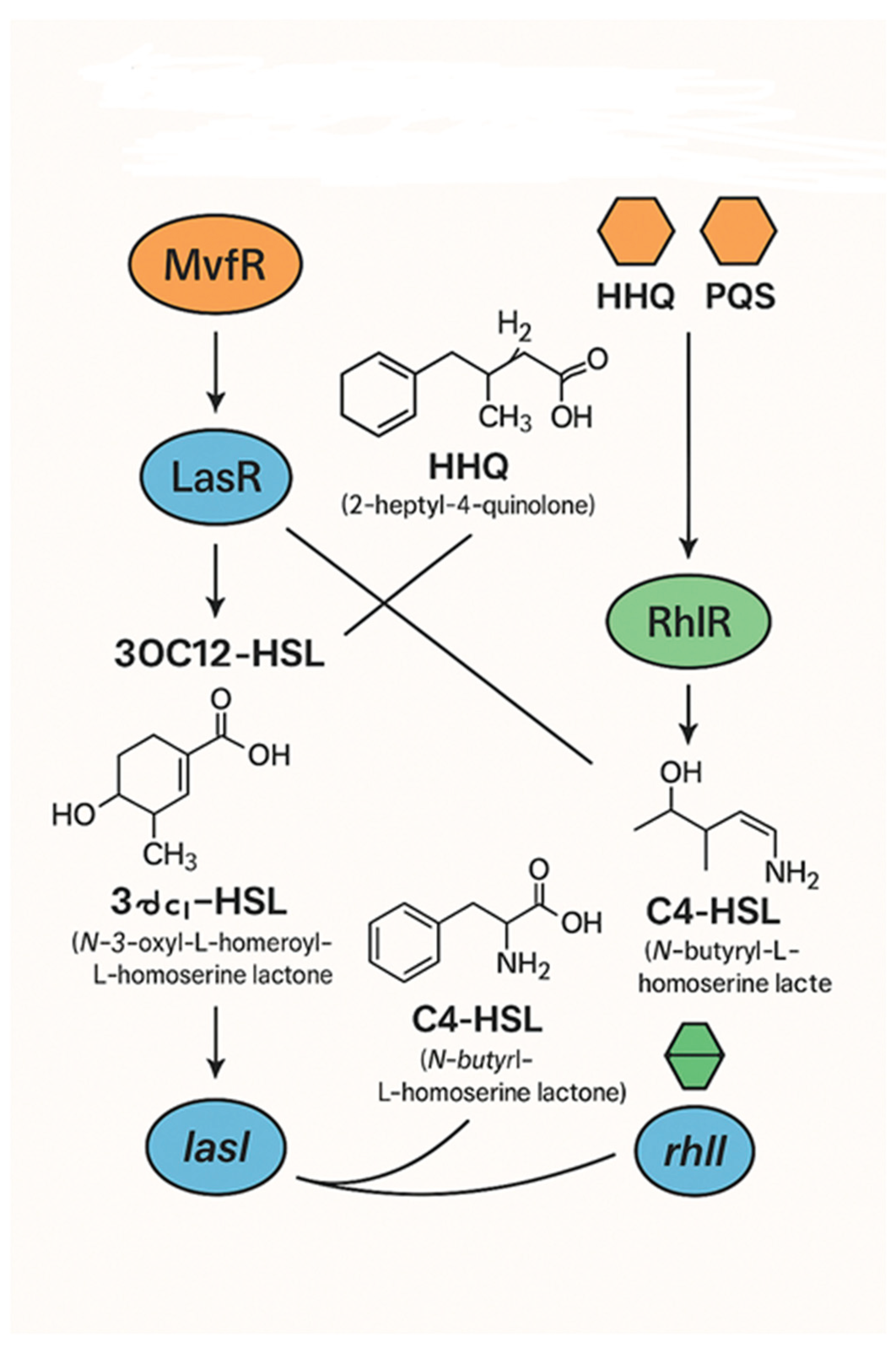

Upon examining bacterial persistence in chronic infections, one uncovers a multitude of multifactorial mechanisms that underscore the complexity of this phenomenon, en-compassing various metabolic pathways, stress responses, antibiotic tolerance, and bio-film formation, among others. The interconnection among these multifactorial systems alludes to an old mechanism of cellular communication known as quorum sensing (QS). Bacteria use quorum sensing to regulate the gene expression that governs collective behaviors. Consequently, antibiotic tolerance correlates with biofilm development, which resulting from the activation of quorum sensing networks. This happens as a result of the elevated concentration of autoinducer molecules when reaching a certain cell density (see

Figure 1). In recent decades, interest in these themes has surged, partly due to the quest for answers to a significant issue afflicting healthcare systems globally, namely the hunt for treatment options for illnesses caused by antibiotic-resistant microbes [

1,

2,

3].

In this background, it is unsurprising that several strategies have been suggested to tackle the aforementioned issue. To our knowledge, the suggested solutions have not at-tained the expected results. We contend that numerous limitations in attaining the desired objectives, specifically in identifying effective treatments against microbial resistance, stem chiefly from the foundational assumptions inherent in the design of these investiga-tions. This subject will be discussed in the first section.

In recent years, an approach for treating bacteria that to an extent was successful over a century ago has been reintroduced. Ironically, it was progressively forsaken with the advent of penicillin.

This review will concentrate on providing the most recent findings from research us-ing bacteriophages as a compelling method to combat bacterial diseases. Understanding the evolution of strategies that disrupt signaling networks associated with pathogen re-ceptors will provide insights into quorum sensing mechanisms, thereby enhancing our comprehension of receptor dynamics essential for developing novel antimicrobial thera-pies.

2. Biology the Way It Is and How It Could Be

Ecosystems consist of populations of various organisms, which may belong to distinct kingdoms. In this context, it may be said that interactions among microbes from various kingdoms have been facilitated by quorum sensing (QS).

These connections have evolved via both cooperative organisms and by pathogens. The intricate signaling networks present in single-celled organisms, both by cooperative organisms and by pathogens, have been enhanced by several stressors and survival threats, leading to the sophisticated molecular processes seen today.

Consequently, emphasizing the primary conclusions of the preceding paragraph necessitates a critical reassessment of the assumptions in biological research that, in various respects, overlook the continuous interplay of molecular interactions that have happened for millennia. Essentially, recognizing that several study designs on a subject as intricate as the one we are examining are hindered by many unknown variables, and that trial and error is not an effective approach to illuminate these overlooked aspects. Besides, a reductionist perspective on biological phenomena fails to elucidate the molecular processes occurring continuously, some of which may be pertinent to addressing the intricate phenomenon of host-pathogen interaction.

At the end of the past century and into this new century, biology has bifurcated into two approaches, significantly influenced by advancements in the study of complex systems: systems biology and synthetic biology.

Nonetheless, it seems that the significant potential of both methodologies to provide innovative strategies for an enhanced comprehension of biology has not been completely actualized. It seems that in this quarter of the 21st century, the ramifications of seeing living organisms as complex systems—arguably the most complex in the universe—have not yet been completely understood. How can we use the concepts of dissipative and fractal systems in systems biology to comprehend the development of molecular network design?

This may also be employed within the context of synthetic biology. Consequently, we may inquire: what has been happening in these more than two decades of development in synthetic biology research? And we maintain that this indicates the direction taken by researchers mostly focused on the so-called “top-down” component of synthetic biology (although it is also possible that we can find some accents of this direction in research on the “bottom-up” component of synthetic biology).

The “top-down” strategy involves using established biological systems, such as bacteria or other cells, and use genetic engineering techniques to alter them for the introduction of novel functionalities or the synthesis of new molecules. Conversely, “bottom-up” methodologies seek to construct synthetic cells from the ground up, beginning with discrete molecules or components and integrating them into bigger nanostructures with innovative functionalities [

4,

5].

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Certainly, the research program centered around genes is mainly belonging to “top-down” synthetic biology. However, we are seeing that in recent years the “bottom-up” synthetic biology is also using the research program centered around genes to design and build artificial cells or protocells [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Although both approaches yield intriguing results, we contend that the bottom-up approach ought to prioritize comprehending the processes and functions arising from simpler systems to enhance the understanding of the development of biological mechanisms, processes, and functions from the ground up. The gene-centric research approach, is the legacy of the top-dawn synthetic biology. The significant potential for uncovering new knowledge and applications offered by the bottom-up method should guide the emergence of the third wave of synthetic biology, characterized by a more systemic rather than reductionist perspective [

11].

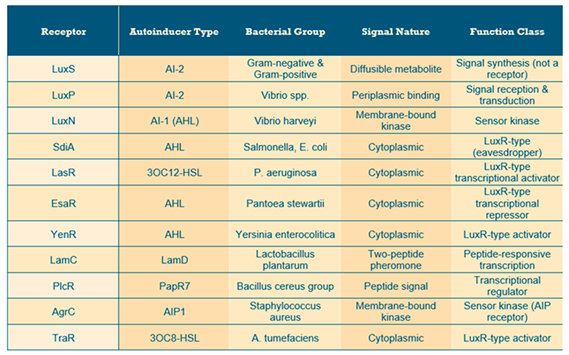

3. Quorum Sensing, Interkingdom Interaction, Importance of Receptors

In all bacterial intercellular communication mechanisms, or quorum sensing (QS) mechanisms, two molecular types are crucial for initiating signaling events: signaling molecules, termed autoinducers (AI), and their corresponding receptors (

Table 1 presents the most recognized receptors and their autoinducers).

Concentrating on receptors, QS systems can be categorized into two classes: interspecies QS receptors and intraspecies QS receptors [

12,

13,

14].

In interkingdom interactions, particularly between bacteria and eukaryotes, organisms from both kingdoms have developed the ability to recognize diverse chemicals, including quorum sensing signals, to modulate gene expression and behavior [

15,

16].

For instance, the QS signal molecule AHL influences mammalian host cells by engaging many signaling pathways, including calcium mobilization and the activation of Rho GTPases and MAPK, among others. Consequently, they regulate several functions and behaviors in host cells, including epithelial barrier integrity, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and the synthesis of immune mediators, among others [

17,

18,

19].

Quorum quenching has been identified in studies of several organisms, including bacteria, fungi, plants, and mammals, which inactivate AHL via enzymes [

20,

21]. In humans, a category of quorum quenching enzymes known as paraoxonases possesses the capability to degrade AHL [

22,

23,

24,

25].

This study emphasizes the promise of bacteriophages in developing treatments for pathogenic bacteria as alternatives to antibiotics; nevertheless, research on quorum sensing extends beyond these subjects.

Over the past two decades, research on QS systems has emerged as a significant priority within the science of microbiology.

Consequently, the progression of knowledge in QS systems originates from several domains. Besides pathogenic microbes, researchers have conducted research on quorum sensing systems in environmental, culinary, and industrial microorganisms, among others [

26,

27,

28].

Nonetheless, despite the substantial number of academics engaged in QS systems across several domains and with diverse objectives, comprehension remains inadequate.

The various QS systems exhibit distinct communication methods. Although QS signaling molecules serve as a universal medium for inter-bacterial communication, the mechanisms by which receptors detect signals and initiate signal transduction differ significantly across various systems [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

In this context, it is important to emphasize that one of the foremost themes in QS systems research is undoubtedly the pivotal role of receptors.

It appears that we have yet to fully define all the receptors within the quorum sensing systems of diverse bacteria. The receptor’s recognition of the mechanism of signal transduction of complex and diverse signaling chemicals from a specific host remains inadequately comprehended [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Finalizing, a recent study delineates numerous unresolved yet significant issues that may enhance the understanding of interkingdom connections mediated by quorum sensing systems Which specific biochemical pathways do quorum sensing molecules influence to alter eukaryotic metabolism and physiology? Which cell surface receptors or transcription factors are shared by QS-producing bacteria and QQ/QSI-producing eukaryotes that enable chemical communication between these entities? What regulatory mechanisms govern the modulation of viral replication methods by QS signals in relation to cell density and the host’s physiological condition? [

40] (p. 9).

4. Bacteriophages as a Substitute for Antibiotics

A crucial facet of employing bacteriophages as a prospective replacement to antibiotics is their capacity to efficiently target and eliminate specific bacteria while sparing human cells from infection. Nonetheless, their elevated selectivity presents a challenge to the advancement of broad-spectrum products utilizing natural bacteriophages.

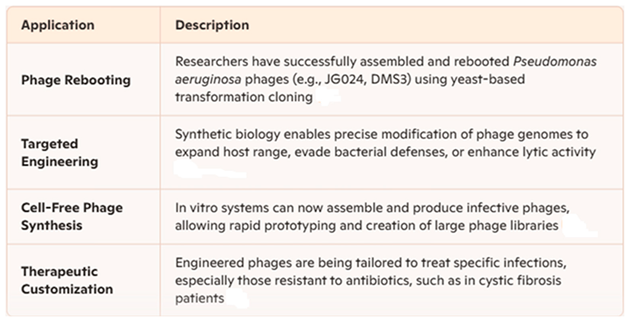

In recent years, synthetic biologists have transformed the area of phage research. Subsequent paragraphs will present some cutting-edge developments at the intersection of synthetic biology and phage engineering (

Table 2).

4.1. Phage Rebooting

Phage rebooting, alternatively referred to as phage genome rebooting or synthetic phage assembly, is an advanced approach in synthetic biology that facilitates the generation of infectious bacteriophage particles from their purified or synthetically engineered genomic DNA. Essentially, it resembles “booting up” a computer with its operating system from the ground up, but for phages..

Phage rebooting fundamentally entails transferring the genetic blueprint of a phage (its DNA genome) onto an appropriate host bacteria. The bacterial host subsequently “interprets” this DNA, expresses the phage genes, replicates the phage genome, and finally constructs new, infectious phage particles capable of infecting and lysing additional bacteria [

41,

42].

Historically, the engineering of phages has predominantly depended on homologous recombination. This entails co-infecting a bacterial host with a wild-type phage plus a modified DNA construct, such as a plasmid, that contains the intended genetic alterations. Recombination subsequently transpires within the host, resulting in an altered phage. This approach possesses multiple limitations: 1) Inefficiency; 2) Restricted changes; 3) Reliance on Wild-Type Phage; 4) Certain bacteria exhibit resistance to DNA transformation, complicating phage engineering [

43,

44].

Conversely, the benefits of Phage Rebooting include: a) Precise Engineering enabling meticulous and comprehensive alterations to the phage genome; b) Synthetic phages exhibiting novel characteristics; c) Mitigation of native host constraints; d) Diminished screening requirements relative to homologous recombination; e) Expedited development of phage therapy; f) Generation of extensive libraries of engineered phages [

45,

46,

47].

In summary, phage rebooting is a synthetic biology approach enabling scientists to construct and reactivate bacteriophages from their genomic DNA, frequently outside their native hosts. Consider it as the digital modification of a phage’s blueprint, subsequently manifesting it within a novel bacterial chassis.

4.2. Targeted Engineering

In synthetic biology, “targeted engineering” in phage research refers to the deliberate and precise modification of bacteriophage genomes and components to bestow new, enhanced, or entirely novel functionalities. This surpasses traditional genetic modification by utilizing systematic engineering techniques to develop phages with desired attributes, specifically for therapeutic, diagnostic, and biotechnological applications. It involves the precise design and modification of bacteriophage genomes to impart new or improved capabilities. This surpasses random modifications by the application of advanced techniques including gene synthesis, genome editing technologies (CRISPR-Cas systems, ZFNs, TALENs), directed evolution, and modular phage engineering (BioBricks and genetic circuits).

Essentially, targeted engineering in phage research involves transitioning from the utilization of naturally existing phages to the creation of them as advanced biological machines. This transition is essential for realizing the complete potential of phages, especially in addressing the global issue of antibiotic resistance [

48,

49,

50,

51].

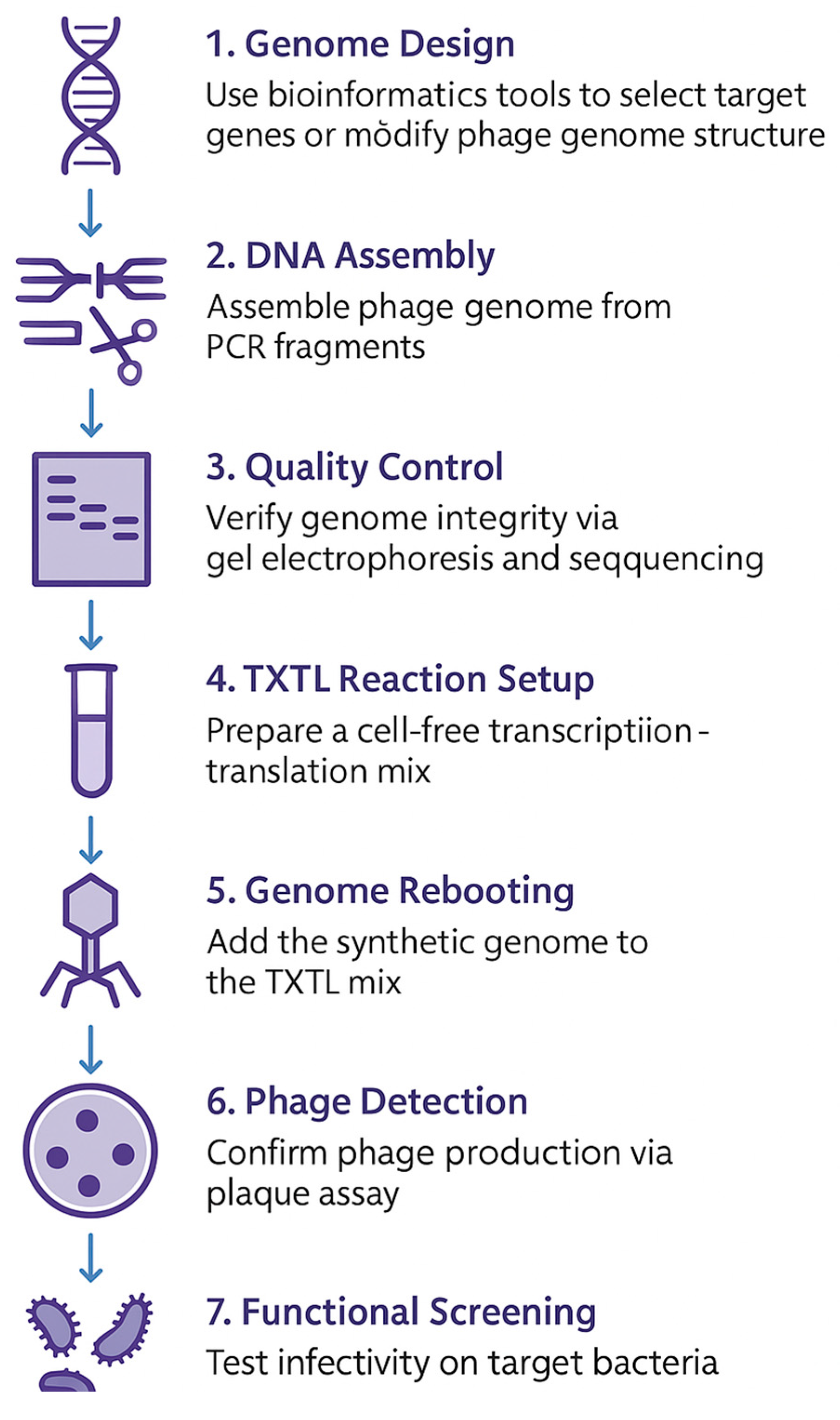

4.3. Cell-Free Phage Synthesis

It employs cell-free transcription–translation (TXTL) systems—essentially, the molecular apparatus of cells (such as ribosomes, enzymes, and tRNAs) that have been removed and reconstituted in vitro—to express phage genomes and construct functional phage particles. Cell-free phage synthesis is an innovative method enabling researchers to generate infective bacteriophages entirely in vitro, eliminating the necessity for living bacterial hosts. This methodology is transforming phage engineering and medicinal advancement (see

Figure 2).

This method possesses numerous benefits [

52,

53]:

1. Living hosts are unnecessary, mitigating host toxicity and simplifying biosafety issues.

2. It facilitates rapid prototyping, expediting the evaluation of created phage variants.

3. High-throughput compatibility facilitates the generation of extensive phage libraries (e.g., 7.5 million variations).

4. Exacting genome regulation facilitating modular construction and modification of phage genomes.

5. Capable of being tailored for individualized phage therapy and synthetic biology applications.

4.3.1. Phage Engineering by In Vitro Gene Expression and Selection

Traditional in vivo phage engineering approaches, such as homologous recombination and lysogenization-based techniques, entail the introduction of specific genetic modifications into the phage genome during its replication within a living bacterial cell. This is frequently predicated on natural or artificial recombination mechanisms (e.g., λ Red recombination) or the incorporation of temperate phages into the host genome. Nonetheless, in vivo techniques are constrained by host viability and metabolic processes, and they need considerable time investment. The processes of bacterial culture, transformation, infection, and screening are time-consuming, often requiring days or weeks. Moreover, designing phages with genes capable of lethally or significantly inhibiting the bacterial host prior to adequate engineering is challenging. Phages that replicate most effectively within the host are preferentially selected, regardless of their therapeutic or functional attributes. Bacterial contamination and endotoxins present intrinsic obstacles to large-scale in vivo phage synthesis for therapeutic applications [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

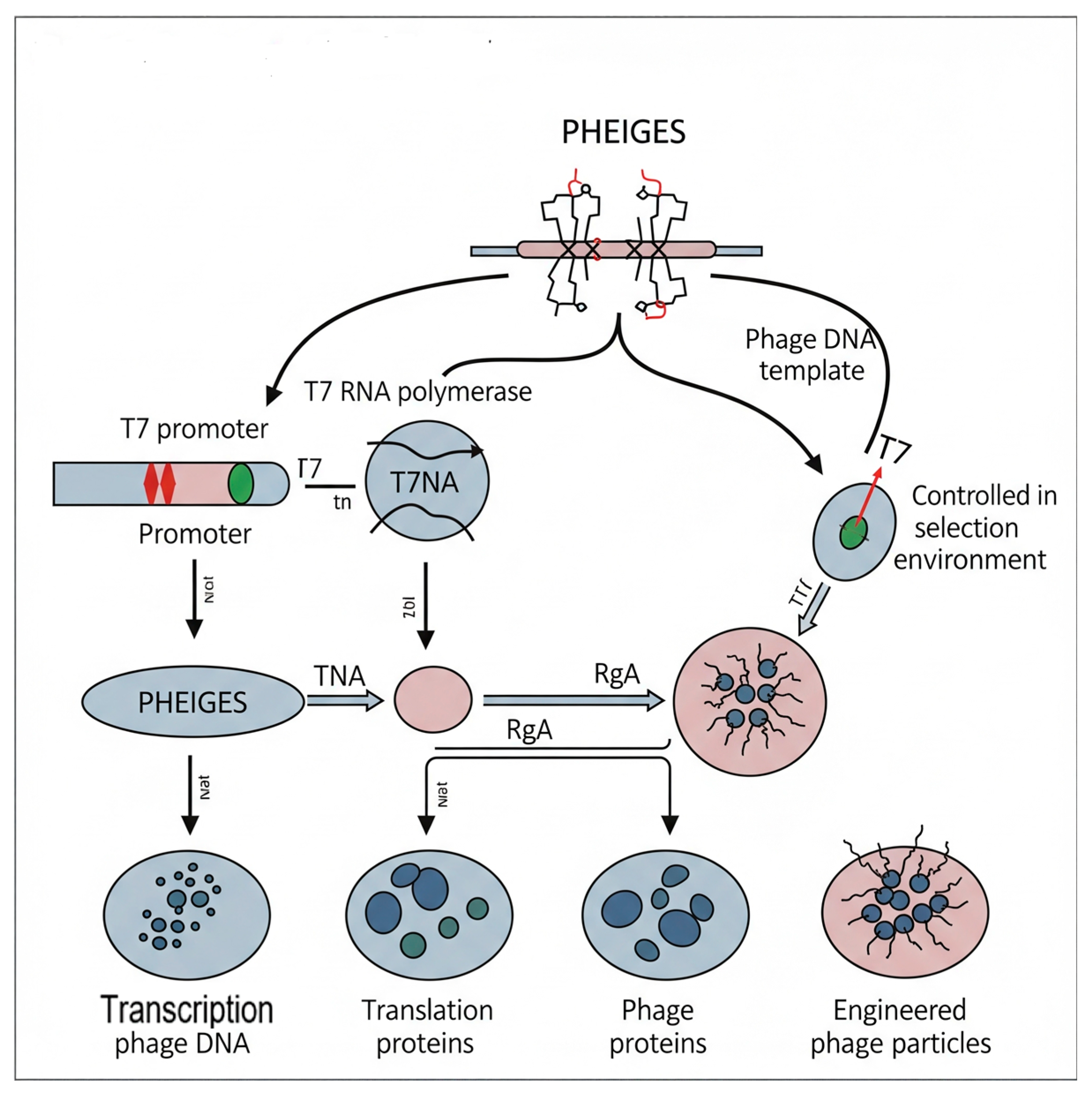

Recently, “Phage Engineering via In Vitro Gene Expression and Selection” has been established. This technology enables scientists to synthesize and enhance bacteriophages in vitro, independent of live cells. This is essential as it expedites the phage engineering process and enhances its precision. PHEIGES is a groundbreaking methodology in phage engineering, characterized by its transition from in vivo (in-cell) techniques to entirely in vitro (in-test-tube) processes for phage production and selection. This ostensibly straightforward modification provides a multitude of advantages that address the significant constraints of conventional phage engineering. PHEIGES markedly decreases the duration necessary for the design, construction, and testing of engineered phages, reducing it from days or weeks to frequently a mere day. The swift iteration cycle is essential in domains like phage therapy, where prompt adaptation to advancing bacterial resistance is vital. The in vitro environment facilitates highly parallel studies, permitting the concurrent testing and selection of extensive libraries of phage variants.

Moreover, PHEIGES facilitates a direct correlation between the genetic alteration (genotype) and the resultant function (phenotype) of the phage. Phages self-assemble from genetic material in a cell-free system, with only those that assemble correctly and possess the intended function being “selected.”

This addresses the issues of genetic bottlenecks and biases that may occur during in vivo replication. Besides, PHEIGES eliminates host-cell compatibility constraints, facilitating the engineering and examination of phages that are challenging or unfeasible to control using conventional techniques, particularly those with atypical replication cycles or toxic components.

In summary, PHEIGES is a cell-free method for phage genome engineering, synthesis, and selection based on T7. It allows for the direct selection of engineered and mutant phages without compartmentalization (see

Figure 3) [

60].

5. Artificial Receptors

With the growing recognition of bacteriophages as innovative antimicrobials and prospective diagnostic tools, there is an intensified interest in elucidating the processes of their interactions with bacterial hosts. The initial phase of a bacteriophage infection involves the identification of specific entities on the bacterial cell surface, facilitated by their phage receptor binding proteins (RBPs). They are situated on their tail structures to engage with specific receptors on the surfaces of bacterial cells. This physical contact is essential for phage attachment and subsequent infection, serving as a critical determinant of the phage’s host range [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66].

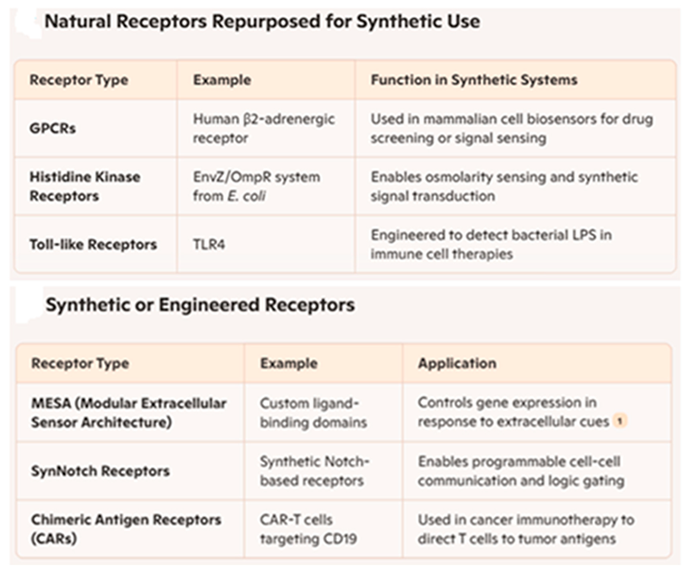

In the past twenty years, synthetic biologists have utilized physical components and principles from natural receptors to create synthetic receptors. These technologies employ tailored sense-and-respond systems that connect a cell’s interactions with extracellular and intracellular signals to user-specified reactions.

Synthetic biology has utilized many receptor types to modify cells capable of detecting and responding to particular signals. Certain receptors are frequently incorporated into synthetic circuits to develop sense-and-respond systems, medicinal devices, or environmental biosensors. Receptors serve a pivotal function in synthetic biology as the sensory regulators of created systems. Synthetic organisms, whether bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cells, are permitted to identify certain environmental, cellular, or chemical signals and thereafter initiate a predetermined reaction (see

Table 3) [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75].

6. Conclusions

Recent revelations regarding phage-host interactions are creating opportunities to combat antibiotic resistance. Cell-free expression systems are emerging as a potential platform for the generation and engineering of bacteriophages. This method enables researchers to swiftly alter phage genomes and express them in vitro, facilitating the prototyping of phages for biotechnological, medical, or diagnostic purposes [

76].

Synthetic phages are artificially manufactured bacteriophages, viruses that target and eliminate bacteria, created to address the shortcomings of wild phages in the treatment of bacterial illnesses. These alterations frequently entail modifying the phage’s receptor-binding proteins (RBPs), which are crucial for identifying and adhering to specific receptors on bacterial cell surfaces. By altering RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), researchers can expand the host range of phages, enhancing their efficacy against a broader spectrum of bacterial strains or specifically targeting strains resistant to natural phages [

77,

78,

79,

80].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chinemerem Nwobodo, D.; Ugwu, M.C.; Oliseloke Anie, C.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S., Chinedu Ikem, J; Victor Chigozie, U, Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022, 36(9), e24655. [CrossRef]

- Cangui-Panchi, S.P.; Ñacato-Toapanta, A.L.; Enríquez-Martínez, L.J.; Reyes, J.; Garzon-Chavez, D.; Machado, A. Biofilm-forming microorganisms causing hospital-acquired infections from intravenous catheter: A systematic review. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2022, 3,100175.

- Crivello, G.; Fracchia, L.; Ciardelli, G.; Boffito, M.; Mattu, C. In Vitro Models of Bacterial Biofilms: Innovative Tools to Improve Understanding and Treatment of Infections. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2023, 13(5),904.

- Gibson, D.G. Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome. Science 2010, 329,52–56. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.G.L.; Schweizer, J.; Kamenova, K.; Au, L.; Blasimme, A.; Vayena, E. Organizational change of synthetic biology research: Emerging initiatives advancing a bottom-up approach. Current Research in Biotechnology 2024, 7, 100188. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Cell-free synthetic biology: Engineering in an open world. Synthetic and systems biotechnology 2017, 2(1), 23-27.

- Göpfrich, K.; Platzman, I.; Spatz, J.P. Mastering Complexity: Towards Bottom-up Construction of Multifunctional Eukaryotic Synthetic Cells. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36(9),938-951. [CrossRef]

- Elani, Y. Interfacing living and synthetic cells as an emerging frontier in synthetic biology. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60(11), 5602-5611.

- Jahnke, K.; Ritzmann, N.; Fichtler, J.; Nitschke, A-; Dreher, Y.; Abele, T.; Hofhaus, G.; Platzman, I.; Schröder, R.R.; Müller, D.J.; Spatz, J.P.; Göpfrich, K. Proton gradients from light-harvesting E. coli control DNA assemblies for synthetic cells. Nat Commun. 2021, 12(1),3967. [CrossRef]

- Olivi, L.; Berger, M.; Creyghton, R.N.; De Franceschi, N.; Dekker, C.; Mulder, B.M.; Claassens, N.J.; Ten Wolde, P.R.; van der Oost, J. Towards a synthetic cell cycle. Nat Commun. 2021, 12(1),4531. [CrossRef]

- El-Samad, H. The Next Emergence of Synthetic Biology. GEN Biotechnology 2024, 3(1),1-2.

- Khan, F.; Javaid, A.; Kim, Y.M. Functional Diversity of Quorum Sensing Receptors in Pathogenic Bacteria: Interspecies, Intraspecies and Interkingdom Level. Curr Drug Targets. 2019, 20(6),655-667. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Wang, H.; Mao, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Grenier, D.; Yi, L.; Wang, Y. Structure and Signal Regulation Mechanism of Interspecies and Interkingdom Quorum Sensing System Receptors. J Agric Food Chem. 2022, 70(2),429-445. [CrossRef]

- Coolahan, M.; Whalen, K.E. A review of quorum-sensing and its role in mediating interkingdom interactions in the ocean. Commun Biol. 2025, 8(1),179. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, A.R.; Sperandio, V. Inter-kingdom signaling: chemical language between bacteria and host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.F.; Venturi, V. A novel widespread interkingdom signaling circuit. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Camara, M. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 182–191. [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, L.M.; Ovchinnikova, E.S.; Meijler, M.M.; Krom, B.P. Microbial spy games and host response: roles of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa small molecule in communication with other species. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002312. [CrossRef]

- Teplitski, M.; Mathesius, U.; Rumbaugh, K.P. Perception and degradation of N-acyl homoserine lactone quorum sensing signals by mammalian and plant cells. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 100–116. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, R.; Jafra, S. Quenching of acyl-homoserine lactone-dependent quorum sensing by enzymatic disruption of signal molecules. Acta Biochim Pol. 2009, 56(1),1-16.

- Chen, F.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Li, X. Quorum quenching enzymes and their application in degrading signal molecules to block quorum sensing-dependent infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2013, 14(9),17477-17500. [CrossRef]

- Camps, J.; Marsillach, J.; Joven, J. The paraoxonases: role in human diseases and methodological difficulties in measurement. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2009, 46(2), 83–106. [CrossRef]

- Amara, N.; Krom, B.P.; Kaufmann, G.F.; Meijler, MM. Macromolecular inhibition of quorum sensing: enzymes, antibodies, and beyond. Chem Rev. 2011, 111(1),195-208. [CrossRef]

- Camps, J.; Iftimie, S.; García-Heredia, A.; Castro, A.; Joven, J. Paraoxonases and infectious diseases. Clinical Biochemistry 2017, 50(13–14), 804-811. [CrossRef]

- Taler-Verčič, A.; Goličnik, M.; Bavec, A. The Structure and Function of Paraoxonase-1 and Its Comparison to Paraoxonase-2 and -3. Molecules 2020, 25(24), 5980. [CrossRef]

- Skandamis, P.N.; Nychas, G.J. Quorum sensing in the context of food microbiology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012, 78(16),5473-5482. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Khan, Sh.J.; Hasan Sh.W. Quorum sensing control and wastewater treatment in quorum quenching/ submerged membrane electro-bioreactor (SMEBR(QQ)) hybrid system. Biomass and Bioenergy 2019, 128,105329. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. Quorum Sensing Systems in Microorganisms and Their Potential Applications. International Journal of Biology and Life Sciences 2025, 10(3), 11-14. [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C.; Wood, T.K.; Kumar, P. Evolution of Resistance to Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors. Microbial Ecology 2014, 68 (1), 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Hao, H.; Xie, S.; Wang, X.; Dai, M.; Huang, L.; Yuan, Z. Antibiotic alternatives: the substitution of antibiotics in animal husbandry? Front Microbiol. 2014, 5,217. [CrossRef]

- García-Contreras, R.; Maeda, T.; Wood, T.K. Resistance to quorum-quenching compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013, 79(22),6840-6846. [CrossRef]

- Christiaen, S.E.; Matthijs, N.; Zhang, X.H.; Nelis, H.J.; Bossier, P.; Coenye, T. Bacteria that inhibit quorum sensing decrease biofilm formation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Pathogens and Disease 2014, 70(3), 271-279. [CrossRef]

- Hochachka, W.M.; Dobson, A.P.; Hawley, D.M.; Dhondt, A.A. Host population dynamics in the face of an evolving pathogen. J Anim Ecol. 2021, 90(6),1480-1491. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Nair, S.K. Quorum sensing: how bacteria can coordinate activity and synchronize their response to external signals? Protein Sci. 2012, 21(10), 1403-1417. [CrossRef]

- Valente, R.S.; Xavier, K.B. The Trk Potassium Transporter Is Required for RsmB-Mediated Activation of Virulence in the Phytopathogen Pectobacterium wasabiae. J Bacteriol. 2015, 198(2), 248-255. [CrossRef]

- Valente, R.S.; Nadal-Jimenez, P.; Carvalho, A.F.P.; Vieira, F.J.D.; Xavier, K.B. Signal Integration in Quorum Sensing Enables Cross-Species Induction of Virulence in Pectobacterium wasabiae. mBio. 2017, 8(3), e00398-17. [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Gorgulla, C.; Boursier, M.E.; Rexrode, N.; Brown, E.C.; Arthanari, H.; Blackwell, H.E.; Nagarajan, R. N-Acyl Homoserine Lactone Analog Modulators of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Rhll Quorum Sensing Signal Synthase. ACS Chem Biol. 2019, 14(10), 2305-2314. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.J.D.; Nadal-Jimenez, P.; Teixeira, L.; Xavier, K.B. Erwinia carotovora Quorum Sensing System Regulates Host-Specific Virulence Factors and Development Delay in Drosophila melanogaster. mBio. 2020, 11(3), e01292-20. [CrossRef]

- Anandan, K.; Vittal, R.R. Quorum quenching strategies of endophytic Bacillus thuringiensis KMCL07 against soft rot pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum. Microb Pathog. 2025, 200,107356. [CrossRef]

- Coolahan, M.; Whalen, K.E. A review of quorum-sensing and its role in mediating interkingdom interactions in the ocean. Commun Biol. 2025, 8(1),179. [CrossRef]

- Fernbach, J.; Meile, S.; Kilcher, S.; Loessner, M.J. Genetic Engineering and Rebooting of Bacteriophages in L-Form Bacteria. Methods Mol Biol. 2024, 2734,247-259. [CrossRef]

- Ipoutcha, T.; Racharaks, R.; Huttelmaier, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Ozer, E.A.; Hartmann, E.M. A synthetic biology approach to assemble and reboot clinically relevant Pseudomonas aeruginosa tailed phages. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e02897-23. [CrossRef]

- Kilcher, S.; Studer, P.; Muessner, C.; Klumpp, J.; Loessner, M.J. Cross-genus rebooting of custom-made, synthetic bacteriophage genomes in L-form bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018, 115(3), 567-572. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Batra, H.; Dong, J.; Chen, C.; Rao, V.B.; Tao, P. Genetic Engineering of Bacteriophages Against Infectious Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 954. [CrossRef]

- Lammens, E.M.; Nikel, P.I.; Lavigne, R. Exploring the synthetic biology potential of bacteriophages for engineering non-model bacteria. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5294. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.J.; Jia, P.P.; Yin, S.; Bu, L.K.; Yang, G.; Pei, D.S. Engineering bacteriophages for enhanced host range and efficacy: insights from bacteriophage-bacteria interactions. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14,1172635. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; He, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, T.; Ye, Y.; Lin, Z. Synthesis of Headful Packaging Phages Through Yeast Transformation-Associated Recombination. Viruses 2025, 17(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Mahalingam, M.; Marasa, B.S.; Zhang, Z.; Chopra, A.K.; Rao, V.B. In vitro and in vivo delivery of genes and proteins using the bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging machine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110(15), 5846-5851. [CrossRef]

- Aljabali, A.A.; Hassan, S.S.; Pabari, R.M.; Shahcheraghi, S.H.; Mishra, V.; Charbe, N.B.; Chellappan, D.K.; Dureja, H.; Gupta, G.; Almutary, A.G.; Alnuqaydan. A.M.; Verma, S.K.; Panda, P.K.; Mishra, Y.K.; Serrano-Aroca, Á.; Dua, K.; Uversky, V.N.; Redwan, E.M.; Bahar, B.; Bhatia, A.; Negi, P.; Goyal, R.; McCarron, P.; Bakshi, H.A.; Tambuwala, M.M. The viral capsid as novel nanomaterials for drug delivery. Future Science OA 2021, 7(9), FSO744. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Veeranarayanan, S.; Thitiananpakorn, K.; Wannigama, D.L. Bacteriophage Bioengineering: A Transformative Approach for Targeted Drug Discovery and Beyond. Pathogens 2023, 12(9), 1179. [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, K.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, F.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Teng, T. Genetic Engineering and Biosynthesis Technology: Keys to Unlocking the Chains of Phage Therapy. Viruses 2023, 15(8),1736. [CrossRef]

- Lemire, S.; Yehl, K.M.; Lu,T.K. Phage-Based Applications in Synthetic Biology. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 453–476. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, C.S.; Petersen, A.Ø.; Kilstrup, M.; van der Helm, E.; Takos, A. Cell-free synthesis of infective phages from in vitro assembled phage genomes for efficient phage engineering and production of large phage libraries. Synth Biol (Oxf) 2024, 9(1), ysae012. [CrossRef]

- Archer, P.K.; Campbell, C.A.: LaRock, D.L.; Jarecke, D.J.; Minnick, M.F.; Donohue, C.A. Bacteriophage λ N protein inhibits transcription slippage by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 5823–5829. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, S.I.; Dias, J.N.R.; André, A.S.; Silva, M.L.; Martins, D.; Carrapiço, B.; Castanho, M.; Carriço, J.; Cavaco, M.; Gaspar, M.M.; Nobre, R.J.; Pereira de Almeida, L.; Oliveira, S.; Gano, L.; Correia, J.D.G.; Barbas, C. 3rd; Gonçalves, J.; Neves, V.; Aires-da-Silva, F. Highly specific blood-brain barrier transmigrating single-domain antibodies selected by an in vivo phage display screening. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1598. [CrossRef]

- Avramucz, Á.; Møller-Olsen, C.; Grigonyte, A.M.; Paramalingam, Y.; Millard, A.; Sagona, A.P.; Fehér, T. Analysing parallel strategies to alter the host specificity of bacteriophage T7. Biology 2021, 10(6), 556. [CrossRef]

- Adler, B.A.; Hessler, T.; Cress, B.F.; Lahiri, A.; Mutalik, V.K.; Barrangou, R.; Banfield, J.; Doudna, J.A. Broad-spectrum CRISPR-Cas13a enables efficient phage genome editing. Nat Microbiol. 2022, 7(12),1967-1979. [CrossRef]

- André, A.S.; Moutinho, I.; Dias, J.N.R.; Aires-da-Silva, F. In vivo Phage Display: A promising selection strategy for the improvement of antibody targeting and drug delivery properties. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13,962124. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.J.; Jia, P.P.; Yin, S.; Bu, L.K.; Yang, G.; Pei, D.S. Engineering bacteriophages for enhanced host range and efficacy: insights from bacteriophage-bacteria interactions. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14,1172635. [CrossRef]

- Levrier, A.; Karpathakis, I.; Nash, B.; Bowden, S.D.; Lindner, A.B.; Noireaux, V. PHEIGES: all-cell-free phage synthesis and selection from engineered genomes. Nat Commun. 2024, 15(1), 2223. [CrossRef]

- Bebeacua C, Tremblay D, Farenc C, Chapot-Chartier MP, Sadovskaya I, van Heel M, Veesler D, Moineau S, Cambillau C. Structure, adsorption to host, and infection mechanism of virulent lactococcal phage p2. J Virol. 2013, 87,12302–12312. [CrossRef]

- Bielmann R, Habann M, Eugster MR, Lurz R, Calendar R, Klumpp J, Loessner MJ. Receptor binding proteins of Listeria monocytogenes bacteriophages A118 and P35 recognize serovar-specific teichoic acids. Virology 2015, 477, 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi Silva, J.; Storms, Z.; Sauvageau, D. Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016, 363, fnw002. [CrossRef]

- Dowah, A.S.A.; Clokie, M.R.J. Review of the nature, diversity and structure of bacteriophage receptor binding proteins that target Gram-positive bacteria. Biophys Rev. 2018, 10(2), 535-542. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Serrano, R.; Dunne, M.; Rosselli, R.; Martin-Cuadrado, A.B.; Grosboillot, V.; Zinsli, L.V.; Roda-Garcia, J.J.; Loessner, M.J.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. Alteromonas Myovirus V22 Represents a New Genus of Marine Bacteriophages Requiring a Tail Fiber Chaperone for Host Recognition. mSystems 2020, 5(3), e00217-20. [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, J.; Dunne, M.; Loessner, M.J. A perfect fit: Bacteriophage receptor-binding proteins for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2023, 71, 102240. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. ed. Synthetic Receptors for Biomolecules: Design Principles and Applications. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2015.

- Edelstein, H.I.; Donahue, P.S.; Muldoon, J.J.; Kang, A.K.; Dolberg, T.B.; Battaglia, L.M.; Allchin, E.R.; Hong, M.; Leonard, J.N. Elucidation and refinement of synthetic receptor mechanisms. Synth Biol (Oxf). 2020, 5(1), ysaa017. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Bonnet, J. Synthetic receptors to understand and control cellular functions. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 633,143-167. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.J.; Yu, Z.Y.; Cai, Y.M.; Du, R.R.; Cai, L. Engineering of an enhanced synthetic Notch receptor by reducing ligand-independent activation. Commun Biol. 2020, 3(1), 116. [CrossRef]

- Scheller, L. Synthetic Receptors for Sensing Soluble Molecules with Mammalian Cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2021, 2312, 15-33. [CrossRef]

- Manhas, J.; Edelstein, H.I.; Leonard, J.N.; Morsut, L. The evolution of synthetic receptor systems. Nat Chem Biol. 2022, 18(3), 244-255. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Raval, M.; Singh, V.; Tiwari, A.K. Synthetic receptors in medicine. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2023, 196, 303-335. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, S.; Ngocho, K.; Zheng, J.; He, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, K.; Shi, H.; Liu, J. Oriented triplex DNA as a synthetic receptor for transmembrane signal transduction. Nat Commun. 2024, 15(1),9789. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.R.; Wu, M.S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Guo, W.; Li, D.W.; Qian, R.C.; Lu, Y. Synthetic transmembrane DNA receptors enable engineered sensing and actuation. Nat Commun. 2025, 16(1), 1464. [CrossRef]

- Nour El-Din, H.; Kettal, M.; Lam, S.; Granados Maciel, J.; Peters, D.L.; Chen, W. Cell-free expression system: a promising platform for bacteriophage production and engineering. Microb Cell Fact. 2025, 24(1),42. [CrossRef]

- Lemire, S.; Yehl, K.M.; Lu, T.K. Phage-Based Applications in Synthetic Biology. Annu Rev Virol. 2018, 5(1), 453-476. [CrossRef]

- Dams, D.; Brøndsted, L.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Briers, Y. Engineering of receptor-binding proteins in bacteriophages and phage tail-like bacteriocins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019, 47(1),449-460. [CrossRef]

- Silpe, J.E.; Duddy, O.P.; Bassler, B.L. Natural and synthetic inhibitors of a phage-encoded quorum-sensing receptor affect phage-host dynamics in mixed bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119(49),e2217813119. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yadav, A. Synthetic phage and its application in phage therapy. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2023; 200,61-89. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).