Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The OE-OH Concept

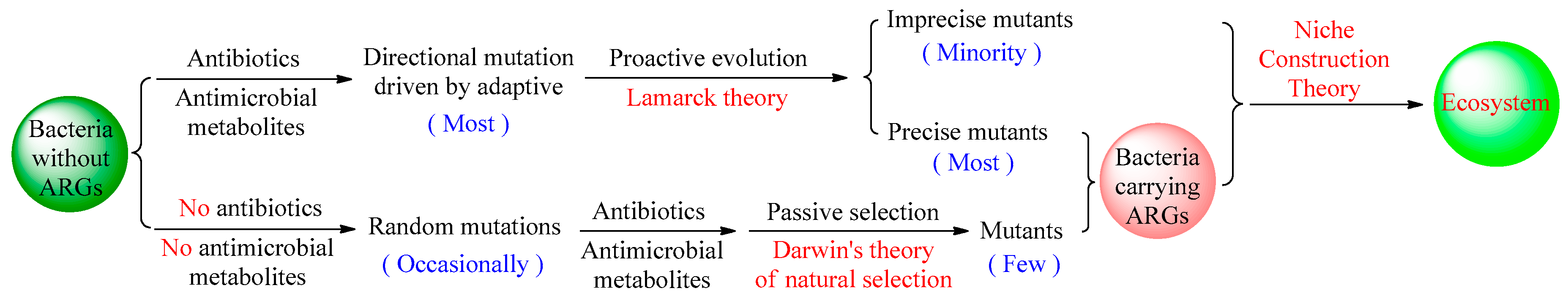

2.1. Dual Mutation Pattern of Bacterial Resistance

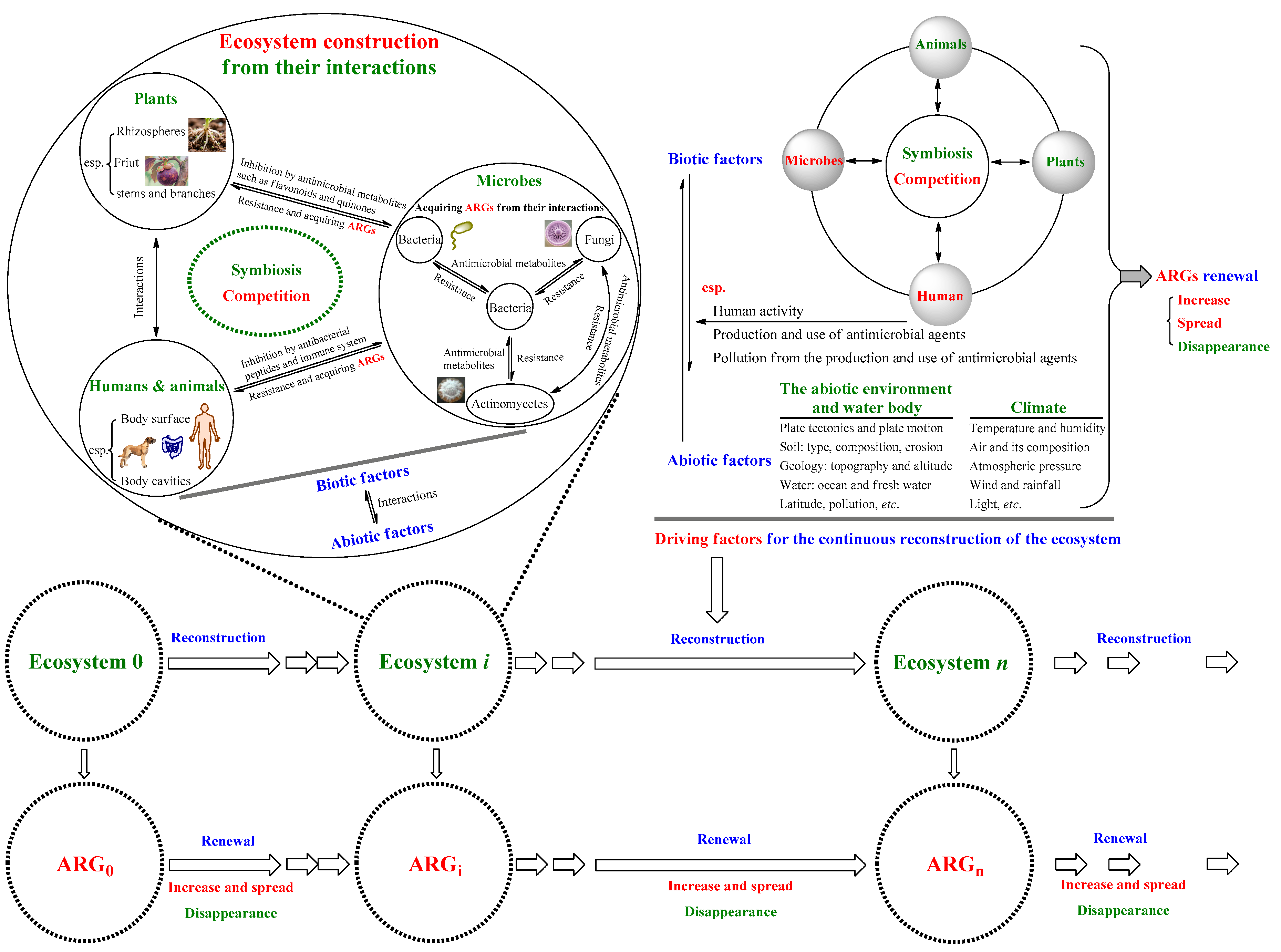

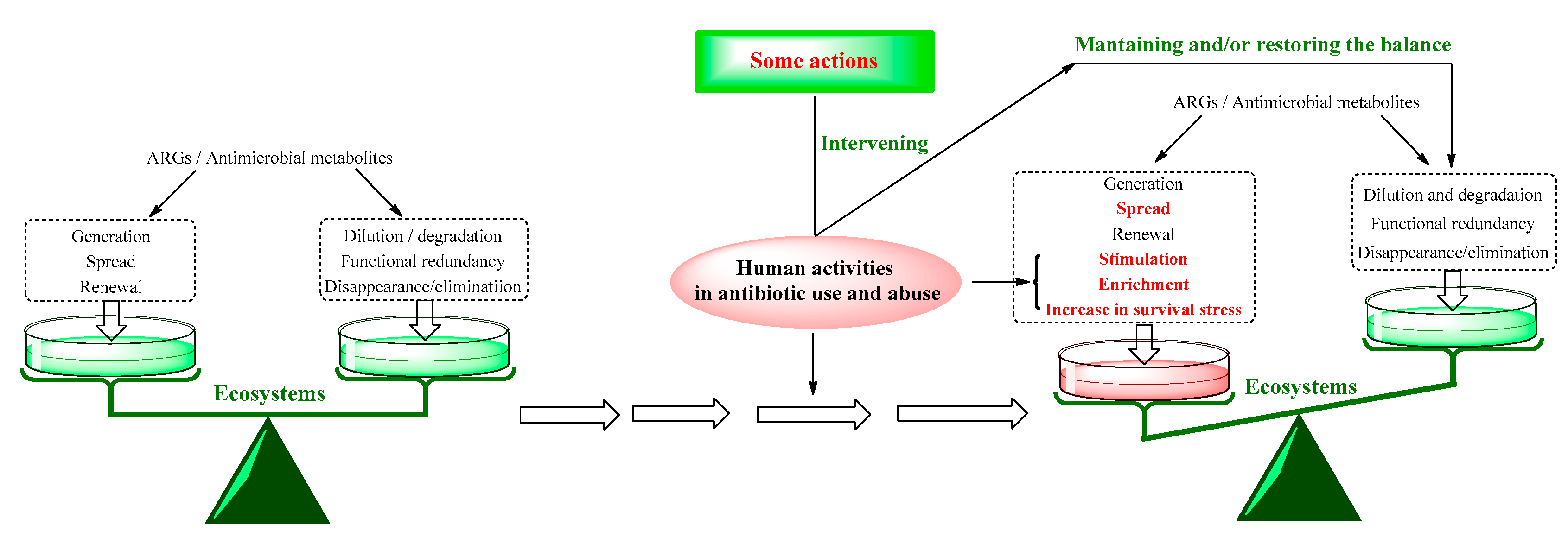

2.2. Theoretical Logic of the OE-OH Concept Based on Ecosystems

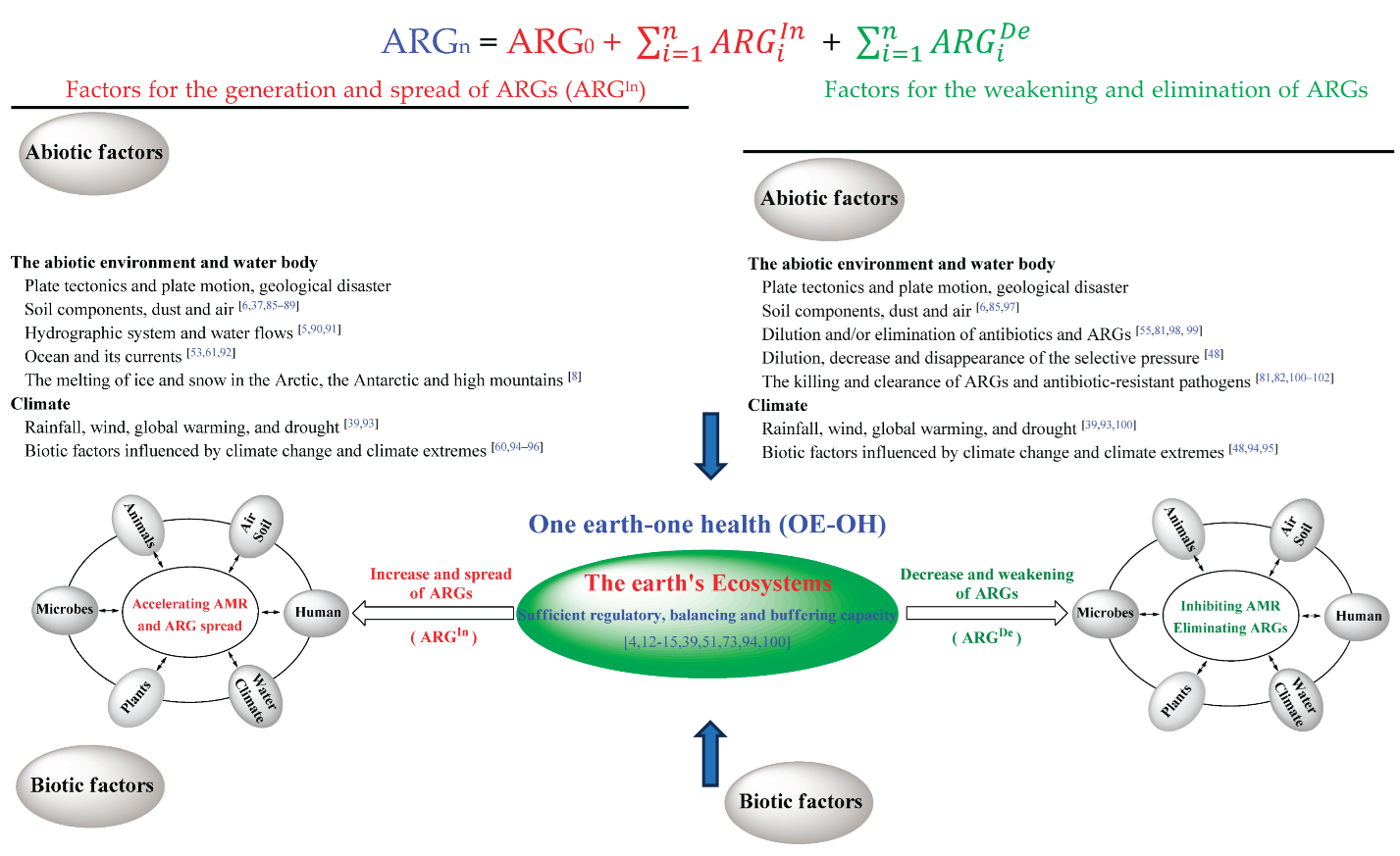

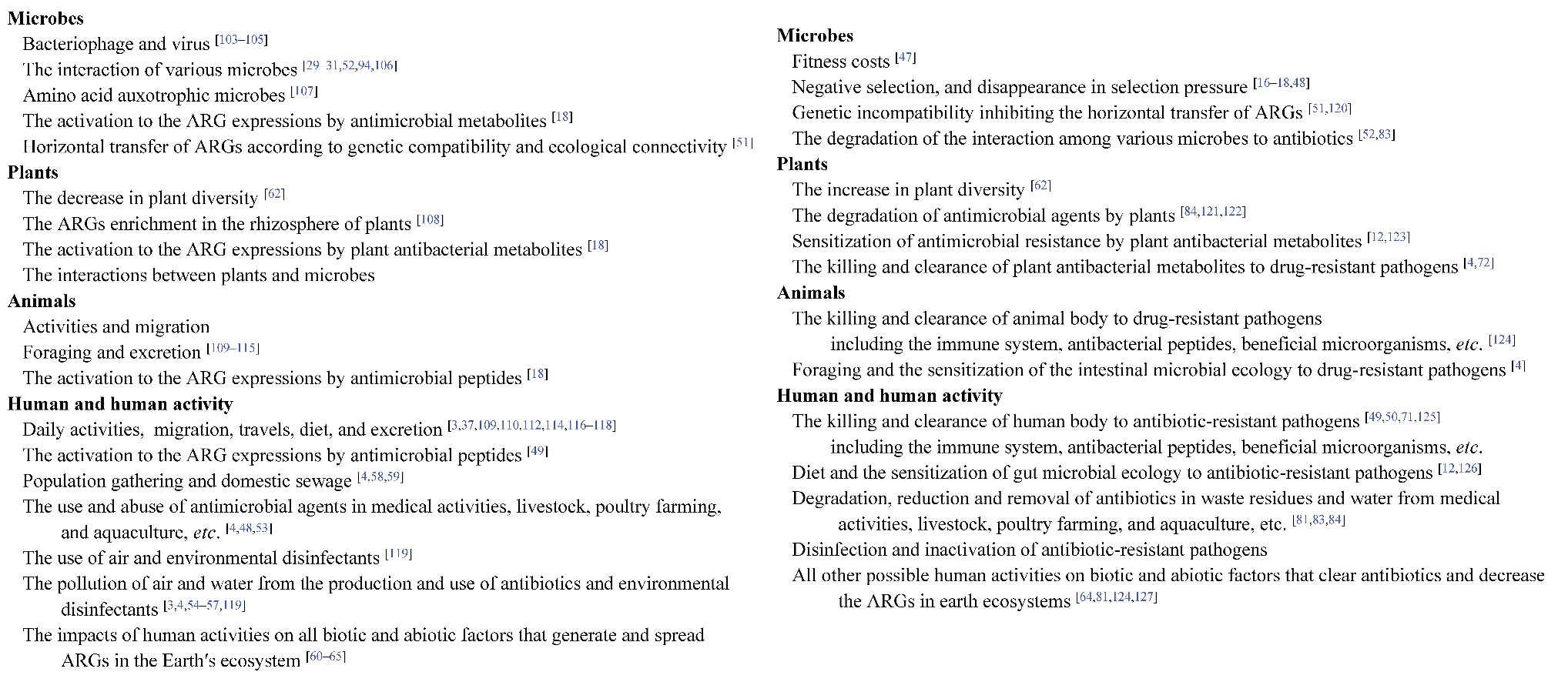

2.3. Basic Mathematical Model for the ARGs Renewing with the Ecosystem

3. ARG Analyses from the OE-OH Concept Based on Ecosystems

3.1. ARGs Emerging Before Humans and Existing Everywhere

3.2. ARGs by the Self-Regulation of Ecosystems Before the Industrial Production and Use of Antibiotics

3.3. Impact of Antibiotic Use on ARGs by the Self-Regulation of Ecosystems

4. Measures Combating ABR from the OE-OH Concept Based on Ecosystems

4.1. Minimizing the Use of Antibiotics, While Fully Utilizing the Regulatory ROLE of Plants on the Body's Ecosystem

4.2. Minimizing the Emissions of Antibiotics and ARGs, While Fully Utilizing the Self-Regulation of Ecosystems.

4.3. Avoiding the Excessive Aggregation of Population

4.4. Accelerating the Development and Reserve of New Antibiotics Based on the Understanding for the Proactive Defense Mechanisms of Microbes

4.5. Encouraging Them in Combination with Plant Antimicrobial Ingredients

4.6. Simulating the Elimination of Antibiotics and ARGs in Ecosystems

5. Methods

5.1. The OE-OH Concept

5.2. Analyses of ARG Generation, Spread and Elimination from the OE-OH Concept

5.3. Measures Combating ABR from the OE-OH Concept Based on Ecosystems

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Mantilla-Calderon, D.; Xiong, Y.; Alkahtani, M.; Bashawri, Y.M.; Al Qarni, H.; Hong, P.Y. Investigation of antibiotic resistome in hospital wastewater during the COVID-19 pandemic: is the initial phase of the pandemic contributing to antimicrobial resistance? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15007–15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, S.; Yutao, L.; Goh, S.G.; Ng, C.; Luhua, Y.; Tran, N.H.; Gin, K.Y. Quaternary ammonium compounds of emerging concern: classification, occurrence, fate, toxicity and antimicrobial resistance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445, 130393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhou, X.; Fu, Q.; Li, Y.; Ni, B.J.; Liu, X. Understanding bacterial ecology to combat antibiotic resistance dissemination. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 23, S0167–7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.; Stirling, E.; Yan, Q.; He, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, H. Global diversity, coexistence and consequences of resistome in inland waters. Water Res. 2024, 253, 121253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Fu, Y.; Shi, H.; Xu, W.; Shen, C.; Hu, B.; Ma, L.; Lou, L. Neglected resistance risks: cooperative resistance of antibiotic resistant bacteria influenced by primary soil components. J. Hazard Mater. 2022, 429, 128229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.Z.; He, L.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhao, J.L.; Zhang, T.; Ying, G.G. Integrating global microbiome data into antibiotic resistance assessment in large rivers. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.X.; Chen, C.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, L.; Qi, F.Y.; Zhu, D.; Li, H.Z.; Cui, L. Hong WL, et al. Antibiotic resistance at environmental multi-media interfaces through integrated genotype and phenotype analysis. J. Hazard Mater. 2024, 480, 136160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddaf, M. 40 million deaths by 2050: toll of drug-resistant infections to rise by 70. Nature 2024, 633, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: the most critical pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, UNEP, WHO, WOAH. One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–2026). Working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment. Rome, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Lian, F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Fatima, A.; Qian, Y. One Earth-One Health (OE-OH): antibacterial effects of plant flavonoids in combination with clinical antibiotics with various mechanisms. Antibiotics, 2025, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenton, T.M. Gaia and natural selection. Nature 1998, 394, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, A.E.; Wilkinson, D.M.; Williams, H.T.P.; Lenton, T.M. Multiple states of environmental regulation in well-mixed model biospheres. J. Theor. Biol. 2017, 414, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maull, V.; Pla Mauri, J.; Conde Pueyo, N.; Solé, R. A synthetic microbial Daisyworld: planetary regulation in the test tube. J. R. Soc. Interface 2024, 21, 20230585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R16. Lynch, M.; O'Hely, M.; Walsh, B.; Force, A. The probability of preservation of a newly arisen gene duplicate. Genetics 2001, 159, 1789–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.H.; Chen, L.; Xiong, Y.L.; Chen, Z.X. Evolution and function of developmentally dynamic pseudogenes in mammals. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.P.J.; Wucher, B.R.; Nadell, C.D.; Foster, K.R. Bacterial defences: mechanisms, evolution and antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Yuan, G.; Wang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, M. Synergistic combination of two antimicrobial agents closing each other's mutant selection windows to prevent antimicrobial resistance. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Yuan, G.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y. Drug combinations to prevent antimicrobial resistance: various correlations and laws, and their verifications, thus proposing some principles and a preliminary scheme. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak, I.; Bartoszewski, R.; Króliczewski, J. Comprehensive review of antimicrobial activities of plant flavonoids. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, F.; Khameneh, B.; Iranshahi, M.; Iranshahy, M. Antibacterial activity of flavonoids and their structure-activity relationship: an update review. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Yi, H.; Zhang, L.; Guan, Y.; Li, S.; Lian, F.; Fatima, A.; Wang, Y. Drug combinations to prevent antimicrobial resistance: theory, scheme and practice. In Book of Abstracts, Proceedings of the 6th International Caparica Conference on Antibiotic Resistance.; Caparica, Portugal, 8–12 September 2024; Capelo-Martinez, J.L., Santos, H.M., Oliveira, E., Fernández, J., Lodeiro, C., Eds.; PROTEOMASS Scientific Society: Caparica, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg, H.A. Occam's razor: from Ockham's via moderna to modern data science. Sci Prog. 2018, 101, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandai, K.; Navarro-Martinez, C.; Smith, B.; Buonopane, R.; Byun, S.A.; Patterson, M. Determining significant correlation between pairs of extant characters in a small parsimony framework. J. Comput. Biol. 2022, 29, 1132–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Meng, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, B.; Hou, X.L.; Yan, B.; Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; et al. Inheritance of acquired adaptive cold tolerance in rice through DNA methylation. Cell, 0092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laland, K.; Matthews, B.; Feldman, M.W. An introduction to niche construction theory. Evol. Ecol. 2016, 30, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.; Ramstead, M.J.D.; Veissière, S.P.L.; Campbell, J.O.; Friston, K.J. A variational approach to niche construction. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20170685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Straight, P.D. Antibiotic discovery through microbial interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.C.; Smith, W.P.J.; Foster, K.R. The evolution of short- and long-range weapons for bacterial competition. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 2080–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmias, N.; Dotan, N.; Rocha, M.C.; Fraenkel, R.; Detert, K.; Kluzek, M.; Shalom, M.; Cheskis, S.; Peedikayil-Kurien, S.; Meitav, G.; et al. Systematic discovery of antibacterial and antifungal bacterial toxins. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 3041–3058, Erratum in: Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; Fukami, T.; Fisher, D.S. Rapid evolution of adaptive niche construction in experimental microbial populations. Evolution 2014, 68, 3307–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, R. The 2009 Garrod lecture: the evolution of antimicrobial resistance: a Darwinian perspective. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini-Andreote, F.; van Elsas, J.D.; Olff, H.; Salles, J.F. Dispersal-competition tradeoff in microbiomes in the quest for land colonization. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohemeng, K.A.; Schwender, C.F.; Fu, K.P.; Barrett, J.F. DNA gyrase inhibitory and antibacterial activity of some flavones (l). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1993, 3, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, J.A.; Lebreton, F.; Salamzade, R.; Shea, T.; Martin, M.J.; Schaufler, K.; Urhan, A.; Abeel, T.; Camargo, I.L.B. C, Sgardioli, B.F.; et al. Global diversity of enterococci and description of 18 previously unknown species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2310852121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, V.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Segata, N. Human microbiome acquisition and transmission. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, P.; Brinch, C.; Møller, F.D.; Petersen, T.N.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Seyfarth, A.M.; Kjeldgaard, J.S.; Svendsen, C.A.; van Bunnik, B.; Berglund, F.; et al. Genomic analysis of sewage from 101 countries reveals global landscape of antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7251, Erratum in: Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial-fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plough, H.H. Penicillin resistance of Staphylococcus aureus and its clinical implications. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1945, 15, 446–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, W.M. Extraction of a highly potent penicillin inactivator from penicillin resistant staphylococci. Science 1944, 99, 452–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Hou, L.; Zhang, L.; Grossart, H.P.; Liu, K.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, A. Distinct influences of altitude on microbiome and antibiotic resistome assembly in a glacial river ecosystem of Mount Everest. J. Hazard Mater. 2024, 479, 135675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arros, P.; Palma, D.; Gálvez-Silva, M.; Gaete, A.; Gonzalez, H.; Carrasco, G.; Coche, J.; Perez, I.; Castro-Nallar, E.; Galbán, C.; et al. Life on the edge: microbial diversity, resistome, and virulome in soils from the union glacier cold desert. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Dawson, R.A.; Bradley, J.A.; Hernández, M. Prevalence and dynamics of antimicrobial resistance in pioneer and developing Arctic soils. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisaccia, M.; Berini, F.; Marinelli, F.; Binda, E. Emerging Trends in antimicrobial resistance in polar aquatic ecosystems. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, G.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Wang, C.; Li, R.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, K.; Hou, C. Occurrence and antibacterial resistance of culturable antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the Fildes Peninsula, Antarctica. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 162, 111829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasouly, A.; Shamovsky, Y.; Epshtein, V.; Tam, K.; Vasilyev, N.; Hao, Z.; Quarta, G.; Pani, B.; Li, L.; Vallin, C.; et al. Analysing the fitness cost of antibiotic resistance to identify targets for combination antimicrobials. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1410–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddamsetti, R.; Yao, Y.; Wang, T.; Gao, J.; Huang, V.T.; Hamrick, G.S.; Son, H.I.; You, L. Duplicated antibiotic resistance genes reveal ongoing selection and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeansyah, E.; Boulouis, C.; Kwa, A.L.H.; Sandberg, J.K. Emerging role for MAIT cells in control of antimicrobial resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelfel, S.; Silva, M.S.; Stecher, B. Intestinal colonization resistance in the context of environmental, host, and microbial determinants. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D.; Parras-Moltó, M.; Inda-Díaz, J.S.; Ebmeyer, S.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Johnning, A.; Kristiansson, E. Genetic compatibility and ecological connectivity drive the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.K.; Meirelles, L.A.; Newman, D.K. From the soil to the clinic: the impact of microbial secondary metabolites on antibiotic tolerance and resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.X.; He, L.Y.; Tang, Y.J.; Qiao, L.K.; Xu, M.C.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Bai, H.; Zhang, M.; Ying, G.G. Deciphering spread of quinolone resistance in mariculture ponds: cross-species and cross-environment transmission of resistome. J. Hazard Mater. 2025, 487, 137198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhou, J.; Topp, E.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z. Treatment of antibiotic-manufacturing wastewater enriches for Aeromonas veronii, a zoonotic antibiotic-resistant emerging pathogen. ISME J. 2025, 19, wraf077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, M.E.; Farkas, K.; Kiss, A.; Jones, D.L. National-scale insights into AMR transmission along the wastewater-environment continuum. Water Res. 2025, 282, 123603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, I.T.; Santos, L. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: a review of the European scenario. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 736–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ye, B.; Wang, L. Antibiotics in soil and water in China-a systematic review and source analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danko, D.; Bezdan, D.; Afshin, E.E.; Ahsanuddin, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Butler, D.J.; Chng, K.R.; Donnellan, D.; Hecht, J.; Jackson, K.; et al. A global metagenomic map of urban microbiomes and antimicrobial resistance. Cell 2021, 184, 3376–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhu, D.; An, X.L.; Yang, X.R.; Su, J.Q.; Qiao, M.; Zhu, Y.G. Spatial and temporal distribution of antibiotic resistomes in a peri-urban area is associated significantly with anthropogenic activities. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Jia, S.; Qu, M.; Pei, Y.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Lyu, N.; et al. A global atlas and drivers of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella during 1900-2023. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Xu, N.; Lu, T.; Hong, W.; Penuelas, J.; Gillings, M.; Wang, M.; Gao, W.; et al. Assessment of global health risk of antibiotic resistance genes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Liu, Y.J.; Fu, Y.M.; Xu, J.Y.; Zhang, T.L.; Cui, H.L.; Qiao, M.; Rillig, M.C.; Zhu, Y.G.; Zhu, D. Microplastic diversity increases the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in soil. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yuan, X.; Lu, W.; Wen, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T. ; Microplastics in livestock manure and compost: environmental distribution, degradation behavior, and their impact on antibiotic resistance gene dissemination, Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Rahman, S.U.; Rehman, A.; Li, H.; Hui, N.; Khalid, M. Shaping rhizocompartments and phyllosphere microbiomes and antibiotic resistance genes: The influence of different fertilizer regimes and biochar application. J. Hazard Mater. 2025, 487, 137148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; Ling, H.; Xie, R.; Fang, L.; Guo, M.; Wu, X. Polyvinyl chloride microplastic triggers bidirectional transmission of antibiotic resistance genes in soil-earthworm systems. Environ. Int. 2025, 198, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorninger, C.; Menéndez, L.P.; Caniglia, G. Social-ecological niche construction for sustainability: understanding destructive processes and exploring regenerative potentials. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 379, 20220431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.; Zheng, E.J.; Valeri, J.A.; Donghia, N.M.; Anahtar, M.N.; Omori, S.; Li, A.; Cubillos-Ruiz, A.; Krishnan, A.; Jin, W.; et al. Discovery of a structural class of antibiotics with explainable deep learning. Nature 2024, 626, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laland, K.; Odling-Smee, J.; Endler, J. Niche construction, sources of selection and trait coevolution. Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20160147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.A.; Long, J.S.; Logan, M.W.; Benton, F. Pareto in prison. Behav. Sci. Law 2025, 43, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.A.; Mazzuchi, T.A.; Sarkani, S.; Forsberg, K. Problem management process, filling the gap in the systems engineering processes between the risk and opportunity processes. Systems Eng 2012, 15, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, K.; Lobov, A.; Antonello, P.; Shmueli, M.D.; Yakir, I.; Weizman, T.; Ulman, A.; Sheban, D.; Laser, E.; Kramer, M.P.; et al. Cell-autonomous innate immunity by proteasome-derived defence peptides. Nature 2025, 639, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.M.; Nakasato, J.A.; de Jesus, G.S.; Micheletti, A.C.; Pott, A.; Yoshida, N.C.; Paulo. P.L. Antimicrobial activity of Pantanal macrophytes against multidrug resistant bacteria shows potential for improving nature-based solutions. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, S.V.; Wiebers, D.O.; Lueddeke, G.; Morand, S.; Lee, K.; Knight, A.; Brainin, M.; Feigin, V.L.; Whitfort, A.; Marcum, J.; et al. Proposed solutions to anthropogenic climate change: A systematic literature review and a new way forward. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liang, P.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Q.; Pu, Q.; Dong, L.; Luo, G.; Mazhar, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Yang, S. Research progress of traditional Chinese medicine against COVID-19. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, K.; Gao, Z.; Harbottle, M.; Sapsford, D.; Cleall, P. Life cycle assessment and cost-benefit analysis of nature-based solutions for contaminated land remediation: a mini-review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, G.; Wild, T.; Hernandez-Garcia, J.; Baptista, M.D.; van Lierop, M.; Bina, O.; Inch, A.; Ode Sang, Å.; Buijs, A.; Dobbs, C.; et al. Supporting nature-based solutions via nature-based thinking across European and Latin American cities. Ambio 2024, 53, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randrup, T.B.; Buijs, A.; Konijnendijk, C.C.; Wild, T. Moving beyond the nature-based solutions discourse: introducing nature-based thinking. Urban Ecosyst. 2020, 23, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, A.; Smith-Torino, M.; Shamamba, S.M.; Chirakarhula, B.; Lwaboshi, M.A.; Benn, C.S.; Chumakov, K. A risk management approach to global pandemics of infectious disease and anti-microbial resistance. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gefen, O.; Ronin, I.; Bar-Meir, M.; Balaban, N.Q. Effect of tolerance on the evolution of antibiotic resistance under drug combinations. Science 2020, 367, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odling-Smee, J.; Erwin, D.H.; Palkovacs, E.P.; Feldman, M.W.; Laland, K.N. Niche construction theory: a practical guide for ecologists. Q. Rev. Biol. 2013, 88, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J. Photocatalysis enhanced constructed wetlands effectively remove antibiotic resistance genes from domestic wastewater. Chemosphere 2023, 325, 138330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Qu, J.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Simulated sunlight-induced inactivation of tetracycline resistant bacteria and effects of dissolved organic matter. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Lu, B.; Zhao, Y. Phytohormone gibberellins treatment enhances multiple antibiotics removal efficiency of different bacteria-microalgae-fungi symbionts. Bioresoure Technol. 2024, 394, 130182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; An, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wen, C.; Yan, C. Phytoremediation for antibiotics removal from aqueous solutions: a meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.X.; Anupoju, S.M.B.; Nguyen, A.; Zhang, H.; Ponder, M.; Krometis, L.A.; Pruden, A.; Liao, J. Evidence of horizontal gene transfer and environmental selection impacting antibiotic resistance evolution in soil-dwelling Listeria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Liang, J.L.; Su, J.Q.; Jia, P.; Lu, J.L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Feng, S.W.; Luo, Z.H.; Ai, H.X.; et al. Globally distributed mining-impacted environments are underexplored hotspots of multidrug resistance genes. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2099–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Hu, H.W.; Maestre, F.T.; Guerra, C.A.; Eisenhauer, N.; Eldridge, D.J.; Zhu, Y.G.; Chen, Q.L.; Trivedi, P.; Du, S.; et al. The global distribution and environmental drivers of the soil antibiotic resistome. Microbiome 2022, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.C.; Shuai, X.Y.; Lin, Z.J.; Zheng, J.; Chen, H. Comprehensive profiling and risk assessment of antibiotic resistance genes in a drinking water watershed by integrated analysis of air-water-soil. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 347, 119092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Yang, T.; Su, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, S.; Gillings, M.; Wang, C.; Ju, F.; Lan, B.; et al. Air pollution could drive global dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. ISME J. 2021, 15, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Liu, X.; Xue, L.; Xiang, D.; Xian, B.; Chu, F.; Fang, F.; Tang, W.; Bao, S.; Fang, T. Determining the spatiotemporal variation, sources, and ecological processes of antibiotic resistance genes in a typical lake of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Yin, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, F.; Li, S.; Shi, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, L.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Zhang, T. Longitudinal metagenomic analysis on antibiotic resistome, mobilome, and microbiome of river ecosystems in a sub-tropical metropolitan city. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dželalija, M.; Kvesić-Ivanković, M.; Jozić, S.; Ordulj, M.; Kalinić, H.; Pavlinović, A.; Šamanić, I.; Maravić, A. Marine resistome of a temperate zone: distribution, diversity, and driving factors across the trophic gradient. Water Res. 2023, 246, 120688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sui, Q.; Xin, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, H.; Wei, Y. An extensive assessment of seasonal rainfall on intracellular and extracellular antibiotic resistance genes in Urban River systems. J. Hazard Mater. 2023, 455, 131561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Thakur, M.P. Climate extremes disrupt fungal-bacterial interactions. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 2226–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, N.W.; Slessarev, E.; Marschmann, G.L.; Nicolas, A.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Brodie, E.L.; Firestone, M.K.; Foley, M.M.; Hestrin, R.; Hungate, B.A.; et al. Life and death in the soil microbiome: how ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, C. Revealing the critical role of rare bacterial communities in shaping antibiotic resistance genes in saline soils through metagenomic analysis. J. Hazard Mater. 2025, 491, 137848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, G.; Li, S.; Feng, R.; Xia, D. The dynamics and removal efficiency of antibiotic resistance genes by UV-LED treatment: an integrated research on single- or dual-wavelength irradiation. Ecotox. Environ. Safe 2023, 263, 115212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, Q.; Fan, Z.; Xu, M.; Ji, R.; Jin, X.; Gu, C. Dry-to-wet fluctuation of moisture contents enhanced the mineralization of chloramphenicol antibiotic. Water Res. 2023, 240, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, A.K. Environmental stress leads to genome streamlining in a widely distributed species of soil bacteria. ISME J. 2022, 16, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xue, S.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Y. Effect of dissolved organic matter on sulfachloropyridazine photolysis in liquid water and ice. Water Res. 2023, 246, 120714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Shao, J.; Hu, P.; Tang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Hao, T. From micro to macro: the role of seawater in maintaining structural integrity and bioactivity of granules in treating antibiotic-laden mariculture wastewater. Water Res. 2023, 246, 120702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, C.; Ramoneda, J.; Kan, A.; Rudge, T.J.; Wang, G.; Johnson, D.R. Phage predation accelerates the spread of plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Yin, X.; Balcazar, J.L.; Huang, D.; Liao, J.; Wang, D.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Yu, P. Bacterium-phage symbiosis facilitates the enrichment of bacterial pathogens and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the plastisphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 2948–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Liang, J.L.; Wen, P.; Jia, P.; Feng, S.W.; Liu, S.Y.; Zhuang, Y.Y.; Guo, Y.Q.; Lu, J.L.; Zhong, S.J.; et al. Giant viruses as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Weiss, A.; Ma, H.R.; Son, H.I.; Zhou, Z.; You, L. Antibiotic-mediated microbial community restructuring is dictated by variability in antibiotic-induced lysis rates and population interactions. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.S.L.; Correia-Melo, C.; Zorrilla, F.; Herrera-Dominguez, L.; Wu, M.Y.; Hartl, J.; Campbell, K.; Blasche, S.; Kreidl, M.; Egger, A.S.; et al. Microbial communities form rich extracellular metabolomes that foster metabolic interactions and promote drug tolerance. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Jin, M.; Zhu, D.; Yang, X.; Qian, H.; Lu, T. Plants select antibiotic resistome in rhizosphere in early stage. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, S.C.; Liu, J.; Kumar, N.; Gulliver, E.L.; Gould, J.A.; Escobar-Zepeda, A.; Mkandawire, T.; Pike, L.J.; Shao, Y.; Stares, M.D.; et al. Strain-level characterization of broad host range mobile genetic elements transferring antibiotic resistance from the human microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberte, L.E.; van Schaik, W. Antibiotic resistance in the commensal human gut microbiota. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Sun, R.; Hu, H.; Duan, G.; Meng, L.; Qiao, M. The overlap of soil and vegetable microbes drives the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from manure-amended soil to vegetables. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, R.S.; McCallum, G.E.; Lamberte, L.E.; van Schaik, W. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in the human gut microbiome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 53, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Patankar, A.V.; Gui, C.; Holmes, S.; Relman, D.A. Brief antibiotic use drives human gut bacteria towards low-cost resistance. Nature 2025, 641, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Mulchandani, R.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Global surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in food animals using priority drugs maps. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, D.M.; Sansom, S.E.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Blaustein, R.A.; Atkins, T.K.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Dangana, T. ; Fukuda, C.; Thotapalli, L.; et al. Clonal Candida auris and ESKAPE pathogens on the skin of residents of nursing homes. Nature 2025, 639, 1016–1023, Erratum in: Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häsler, R.; Kautz, C.; Rehman, A.; Podschun, R.; Gassling, V.; Brzoska, P.; Sherlock, J.; Gräsner, J.T.; Hoppenstedt, G.; Schubert, S.; et al. The antibiotic resistome and microbiota landscape of refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan in Germany. Microbiome 2018, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, L.; Rao, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. Transmission of the human respiratory microbiome and antibiotic resistance genes in healthy populations. Microbiome 2025, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Huang, Z.; Malakar, P.K.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Antimicrobial resistomes in food chain microbiomes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 6953–6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Guo, J. Disinfection spreads antimicrobial resistance. Science 2021, 371, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dagan, T. The evolution of antibiotic resistance islands occurs within the framework of plasmid lineages. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zheng, J.; Tang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lin, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J. Retrievable hydrogel networks with confined microalgae for efficient antibiotic degradation and enhanced stress tolerance. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Vadiveloo, A.; Chen, A.J.; Liu, W.Z.; Chen, D.Z.; Gao, F. Supplementation of exogenous phytohormones for enhancing the removal of sulfamethoxazole and the simultaneous accumulation of lipid by Chlorella vulgaris. Bioresoure Technol. 2023, 378, 129002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.P.; Koprivova, A.; Kopriva, S. Pinpointing secondary metabolites that shape the composition and function of the plant microbiome. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gao, B.; Henawy, A.R.; Rehman, K.U.; Ren, Z.; Jiménez, N.; Zheng, L.; Huang, F.; Yu, Z.; Yu, C.; et al. Mitigating the transfer risk of antibiotic resistance genes from fertilized soil to cherry radish during the application of insect fertilizer. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, K.; Jia, Y.; Shi, J.; Tong, Z.; Fang, D.; Yang, B.; Su, C.; Li, R.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Z. Gut microbiome alterations in high-fat-diet-fed mice are associated with antibiotic tolerance. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Dios, R.; Proctor, C.R.; Maslova, E.; Dzalbe, S.; Rudolph, C.J.; McCarthy, R.R. Artificial sweeteners inhibit multidrug-resistant pathogen growth and potentiate antibiotic activity. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e16397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Yang, P.; Wang, B.; Xu, Q.; Song, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, M. Divergent mitigation mechanisms of soil antibiotic resistance genes by biochar from different agricultural wastes. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 374, 126247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).