1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been seriously threatening to human health and economic development [

1,

2,

3], simultaneously the COVID-19 pandemic further accelerates this global problem [

3]. AMR and its evolution are closely related to the application of antibacterial agents, and food, environment, etc. [

4], and preventing AMR is very complex, involving many aspects [

5]. For drugs, many strategies have been putting forward to fight or delay the resistance, such as the development of new antimicrobial agents [

6], combination therapy [

7], antibiotic adjuvants, optimal use of clinic antimicrobial agents, and revival of old antibiotics [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Among them combination therapy has been proved to be an economic and effective strategy to fight the resistance, and it has been indicating that rational combination therapies can not only enhance the clinical efficacy of antibacterial agents [

12], but also make full use of clinical antibacterial resources to reduce the cost and gain enough time for preventing AMR, delaying the evolution of AMR [

9,

12,

13,

14]. Therefore, it is important to quickly discover synergistic antibacterial combinations from clinical antibacterial agents.

It is generally believed that the combination of antibacterial agents with different mechanisms would present a higher probability of synergistic effects. However, the result evaluated by us indicated that most of them show non-synergistic antibacterial effects, and while antimicrobial agents targeting same macromolecular biosynthesis pathway with different sites have a great potency to discover synergistic combinations [

15]. Namely, the combination of antibacterial agents acting on different metabolic sites of the same biomacromolecule metabolic pathway would present a higher probability of synergistic effects [

15]. Also, this result was immediately proved by Brochado,

et al. from European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Germany [

14], and also by subsequent experiments on natural products as α-mangostin and carnosic acid respectively in combination with clinical antibiotics with different mechanisms of action [

16].

Along with the in-depth research on drug combinations, the reports on plant natural products in combination with clinical antibiotics have been continuously increasing. The results show that many of them, especially plant flavonoids, not only can remarkably enhance the antibacterial effects of clinical antibiotics, but also can reverse the resistance or even enhance the susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria to clinical antibiotics [

17,

18,

19]. Some plant flavonoids also have antibacterial activities comparable to clinical antibiotics.

Based on this, to widely verify above drug selection rules for synergistic combination, and discover possible new rules on the combination of plant flavonoids and clinical antibiotics, here 37 plant flavonoids with different antibacterial potentials were further evaluated on the antibacterial effect of them in combination with clinical antibiotics having different antibacterial mechanisms, and

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli were used as the representatives of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. Based on this research, and various laws and conclusions of combination therapy preventing AMR discovered by us [

20], the concept of One Earth One Health (OE OH) was proposed to prevent AMR, at the 6

th International Caparica Conference in Antibiotic Resistance 2024 (IC

2AR 2024) [

21]. Now, the research is presented as follows:

2. Results

2.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The MICs of 9 clinical antibiotics against pathogenic bacterial S. aureus ATCC 25923 and E. coli ATCC 25922 are listed in

Table 1. These antibiotics involve various antibacterial mechanisms, including the inhibition to the synthesis of cell wall or protein and the damage to cell membrane along with the alteration in membrane permeability. They have different activities against S. aureus and E. coli, respectively with MICs ranged from 0.25 to 32 μg/mL and 1 to 1024 μg/mL.

Another, the MICs, expressed as the molar concentration (μM), of 37 plant flavonoids against S. aureus ATCC 25923 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were reported in our previous work [

27], and here the raw data of their MICs (μg/mL) were reorganized and shown in

Table 2. These plant flavonoids includes various structural subtypes, such as dihydroflavones, flavones, flavonols, chalcones, isoflavones and xanthones. From

Table 2, they present different antibacterial activity against S. aureus ATCC 25923, with the MICs ranged from 2 to 4096 μg/mL or more than 2048 μg/mL, and a few of them show antibacterial activities comparable to clinical antibiotics, such as sophoraflavanone G and α-mangostin. However, all plant flavonoids in

Table 2 show weak inhibitory activities against E. coli ATCC 25922, and their MICs range from 512 to more than 2048 μg/mL.

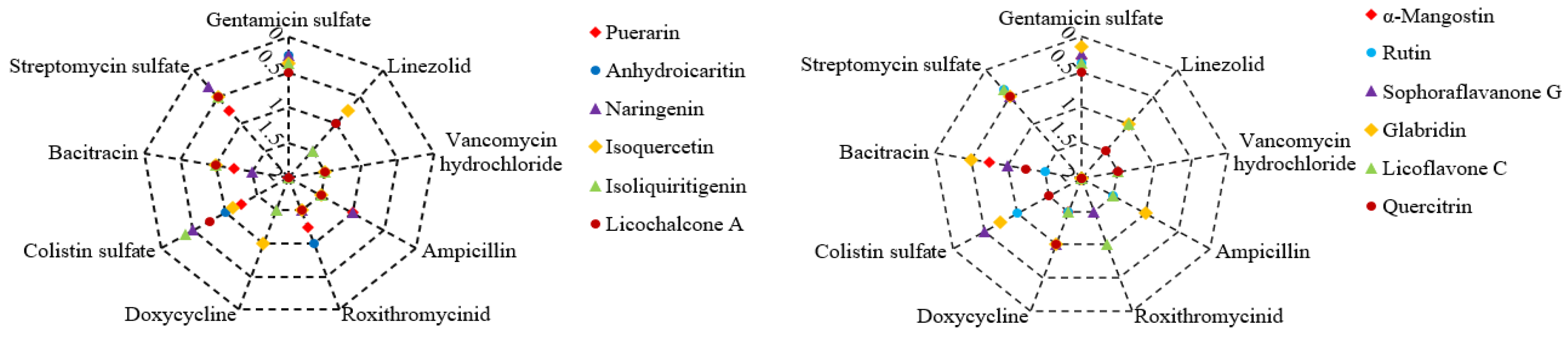

2.2. Antibacterial Effects of Plant Flavonoids in Combination with Clinical Antibiotics to S. aureus

There are 12 plant flavonoids with definite MIC values against

S. aureus ATCC 25923 in

Table 2. They are quercetin, anhydroicaritin, isovitexin, isoliquiritigenin, licoflavone C, rutin, naringenin, puerarin, glabridin, licochalcone A, sophoraflavanone G and α-mangostin, respectively. The antibacterial effects of these plant flavonoids in combination with 9 clinical antibiotics (

Table 1) were determined on 96-well plates, and the results are shown in

Figure 1. Among these 108 combinations against

S. aureus, 27 ones presented synergistic effect, and which was equal to 25% of all combinations.

From

Figure 1, all tested plant flavonoids show synergistic effects against

S. aureus ATCC 25923 when combined with gentamicin sulfate or streptomycin sulfate, except for puerarin in combination with streptomycin sulfate. Simultaneously, a few of these plant flavonoids show synergistic effects against

S. aureus ATCC 25923 when combined with antibiotics that affect the cell membrane, such as colistin sulfate or bacitracin. However, all tested plant flavonoids show indifferent effects when combined with antibiotics that inhibit the biosynthesis of bacterial cell wall or protein, such as vancomycin hydrochloride, ampicillin, roxithromycin, doxycycline and linezolid. As the antibacterial mechanism of gentamicin sulfate, streptomycin sulfate, colistin sulfate and bacitracin involves the impact on the cell membrane, the above combinational effect of 12 plant flavonoids and 9 antibiotics are consistent with the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations [

15].

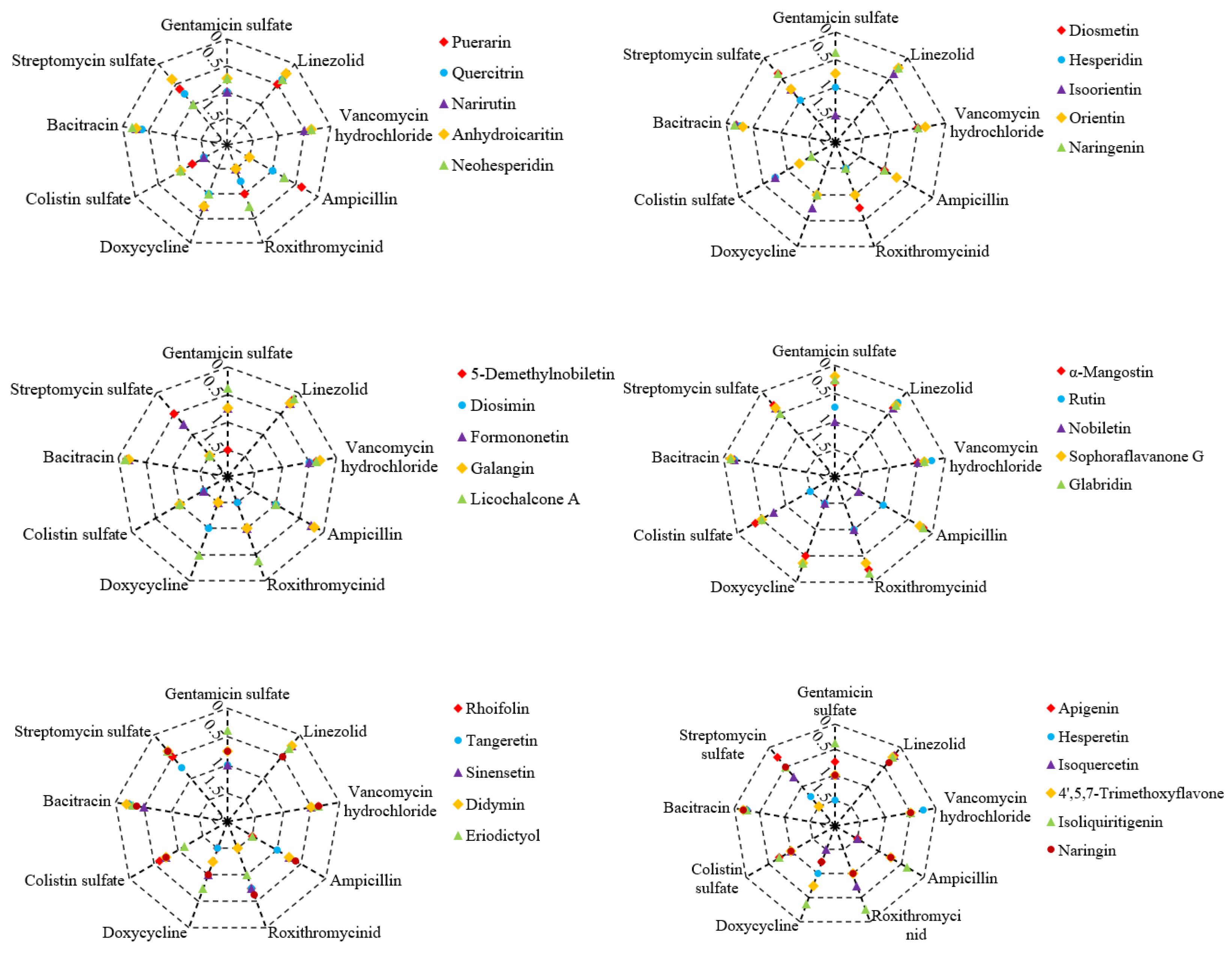

2.3. Antibacterial Effects of Plant Flavonoids in Combination with Clinical Antibiotics to E. coli

As shown in

Table 2, there are a total of 32 plant flavonoids with definite MIC values against

E. coli ATCC 25922. The antibacterial effects of these plant flavonoids in combination with 9 clinical antibiotics (

Table 1) were also determined, and the results are shown in

Figure 2. Among these 288 combinations against

E. coli, 141 ones presented synergistic effect, and which was equal to 49.0% of all combinations. Namely, approximately half of these combinations presented synergistic effect.

Different from the combinational effects described in section 2.2, here these 32 plant flavonoids, including most of 12 flavonoids with definite MIC values against

S. aureus ATCC 25923, in combination with antibiotics show extensively synergistic effects against

E. coli ATCC 25922 from

Figure 2. Notably, all the plant flavonoids showing relatively stronger activity against

E. coli ATCC 25922, such as glabridin, sophoraside G, and α-mangostin, exhibit synergistic effects when combined with the antibiotics listed in

Table 1. Additionally, isoliquiritigenin and licochalcone A also present synergistic antibacterial effects with most of tested antibiotics. It is worth noting that antibiotics clinically used for treating Gram-positive bacterial infections, such as vancomycin hydrochloride, linezolid, and bacitracin, show synergistic effects against

E. coli ATCC 25922 when combined with all tested plant flavonoids although these antibiotics have weak activity against

E. coli. Moreover, streptomycin sulfate shows synergistic effects against

E. coli when combined with many of tested plant flavonoids, and which was similar to those cases against

S. aureus. However, gentamicin sulfate exhibits synergistic effects against

E. coli only when combined with glabridin, sophoraside G, α-mangostin, isoliquiritigenin, licochalcone A, hispidulin, and naringin. The different effect of plant flavonoids in combination with antibiotics against

S. aureus and

E. coli maybe due to their different antibacterial mechanism [

27].

2.4. Antibacterial Effects of Plant Flavonoids in Combination with Levofloxacin to E. coli

Considering that DNA gyrase is an important target for plant flavonoids against Gram-negative bacteria [

27], those plant flavonoids presented extensive synergistic effects when combined with tested antibiotics against

E. coli, including glabridin, sophoraside G, α-mangostin, isoliquiritigenin, and licochalcone A, are likely to exhibit non-synergistic effects in combination with quinolone antibacterial agents acting on DNA gyrase, according to the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations [

15]. Thereby, the antibacterial effects of these five plant flavonoids in combination with levofloxacin against

E. coli ATCC 25922 were further determined using the same methods described in sections 4.3 and 4.4. The results show that all the combinations exhibit indifferent effects, with the FICI values ranging from 0.625 to 2.125. Conversely, this once again supports the rationality of the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations. Namely, the probability of discovering synergistic combinations is higher from antibacterial agents that act on different metabolic sites of the same macromolecular metabolite pathway.

3. Discussion

Along with the continuous research on antimicrobial natural products and combination therapy, plant flavonoids, which are widely distributed in plants and have good safety, have attracted much attention, and related researches and reviews are emerging increasingly [

17,

18,

19]. However, there are three aspects worth discussing: (1) Due to differences in testing environment, conditions, methods, and specific operations, there are significant differences in the results reported from different literature for some compounds. Using the microbroth dilution method, the MIC value generally resulted from a series of concentrations with half dilution, and the actual one may not be exactly at the set concentration. For example, the series of concentrations may include 10, 5, and 2.5 μg/mL (or 12.5, 6.25, and 3.13 μg/mL), if the observed MIC value is 5 μg/mL (or 6.25 μg/mL), the actual value could be 4 or 3 μg/mL (or 5 or 4 μg/mL). Therefore, an error of 1/2 to 2 × MIC would be introduced. Considering the differences in various laboratories, testing conditions and methods, and specific operations, greater errors would be even led to. Therefore, the ratio of MIC values reported for a compound against the same bacterial strain should be considered reasonable within the range of 1/2 to 2 and even 1/4 to 4 [

28,

29], using the microbroth dilution method. (2) Many compounds have significantly difference in the inhibitory activities and/or action mechanisms against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, due to their different cell structures especially the bacterial envelope. However, some literature did not strictly differentiate these when reviewing the antibacterial mechanisms of plant flavonoids [

17,

27,

29], which can easily lead to some confusion in antibacterial mechanisms, and the erroneous transmission of research results. (3) The antibacterial mechanisms of a few plant flavonoids were limited to molecular levels including only theoretical calculations with molecular docking, lacking the comprehensive cellular experiments and the actual explorations at the cellular biochemical level [

28,

30]. Based on these, here the antibacterial properties, combination therapy and synergistic mechanisms of plant flavonoids were discussed, combing with our researches on their structure-activity relationships and mechanisms respectively against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

27,

28,

29,

31].

3.1. Differences in Plant Flavonoids Against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria

Combined with our researches on plant flavonoids against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

27,

28], here this research indicates that the antibacterial activities of plant flavonoids are weaker than clinic antibiotics, while a few of plant flavonoids present comparable activity against Gram-positive bacteria to clinical antibiotics (

Table 2). Overall, plant flavonoids show stronger activities against Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative species. Simultaneously, plant flavonoids with stronger hydrophilicity exhibit stronger activities against Gram-negative bacteria, while those with lipophilicity demonstrate strong against Gram-positive species. These indicate that there is a higher probability of discovering natural products with strong activity against Gram-positive bacteria from plant flavonoids.

Another, the results show that it is relatively easy to discover synergistic combinations consisted of plant flavonoids and clinical antibiotics. However, plant flavonoids in combination with antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria (about 50%) have more extensive synergistic effects than those against Gram-positive species (25%). This is a very fortunate thing since it is more severe resistance of Gram-negative bacteria than Gram-positive species to clinical antibiotics [

32]. Therefore, it is encouraged to increase the researches on the combined use of plant flavonoids with clinical antibiotics, for discovering more synergistic combinations against Gram-negative bacteria and delaying the evolution of Gram-negative ones.

3.2. Drug Selection and Synergistic Mechanisms of Plant Flavonoids in Combination with Antibiotics

As previously reported, the cell membrane is the primary action site of plant flavonoids against Gram-positive bacteria, while there are multiple mechanisms of plant flavonoids against Gram-negative ones [

27]. Besides the cell membrane as an important action site, DNA gyrase is also another important target of plant flavonoids against Gram-positive bacteria [

27].

According to the results in section 2.2, plant flavonoids show extensively synergistic effects when combined with antibiotics acting on bacterial ribosomes and affecting the cell membrane, such as gentamicin sulfate and streptomycin sulfate. Simultaneously, a few plant flavonoids also show synergistic effects when combined with colistin sulfate and bacitracin, which can damage to the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria. In contrast, all test plant flavonoids show indifferent effects when combined with other antibiotics that do not target the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria. Given that the cell membrane is the main site of action of plant flavonoids against Gram-positive bacteria, involving cell membrane damage and inhibition of the respiratory chain quinone pool [

29,

31], the above antibacterial effects of plant flavonoids in combination with clinical antibiotics against

S. aureus not only match the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations [

15], it further proves the rationality of this rule in turn.

According to the results in section 2.2, plant flavonoids show universal synergistic effects when combined with antibiotics against

E. coli, especially when combined with antibiotics such as vancomycin hydrochloride, bacitracin, and linezolid, which mainly inhibit to Gram-positive bacteria and have weak activity against

E. coli, all combinations showing synergistic effects. This may be interpreted that it is weak ability for these three antibiotics to penetrate the cell membrane the outer membrane of

E. coli to reach the inner membrane and cytoplasm where they act, but when combined with plant flavonoids that have membrane damage effects [

19,

33,

34], the concentration of these antibiotics reaching the inner membrane and cytoplasm increases, thus presenting a synergistic antibacterial effect. This is also supported by the synergistic effects resulted from plant flavonoids such as glabridin, sophoraside G, and α-mangostin in combination with all tested antibiotics. As these three plant flavonoids have stronger activity against both

S. aureus and

E. coli, they not only have stronger damage to cell membrane (strong inhibitory activity against

S. aureus), but can also reach the target site at the inner membrane or nuclear region of

E. coli at higher concentrations since they have stronger inhibitory activity against

E. coli. However, for antibiotics that have stronger inhibitory activity against

E. coli or whose inhibitory activity

S. aureus and

E. coli is approximate, this impact of plant flavonoids enhancing the membrane permeability of these antibiotics might be diminished since they can penetrate the outer membrane, or the site of action is out of the inner membrane of

E. coli. This may be the biological explanation that the antibacterial effects of these antibiotics combined with plant flavonoids were consistent with the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations. These antibiotics include streptomycin sulfate, gentamicin sulfate, bacitracin, doxycycline and ampicillin, and all of them involve the effect on the cell membrane. Differently, roxithromycin, which is mainly active against Gram-positive bacteria, shows indifferent effects when combined with plant flavonoids against

E. coli. This result also followed the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations, and might be due to the main mechanism of action of roxithromycin against

E. coli is not necessarily or entirely on the ribosome.

Based on above analyses, for antibiotics that are strong activity against Gram-positive bacteria but weak against Gram-negative ones, plant flavonoids can enhance the concentration of antibiotics reaching their targets by damaging the cell membrane, thus exhibiting a synergistic effect. Simultaneously, antibiotics, except quinolone antibacterial agents, in combination with plant flavonoids with stronger activities against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria likely show extensively synergistic effects, due to their various mechanisms against Gram-negative bacteria and stronger damage to the cell membrane. Moreover, the combined antibacterial effects of plant flavonoids with antibiotics follow the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations [

15]. Therefore, this also provides a theoretical basis for the combined use of plant flavonoids and antibiotics.

3.3. Clinical Antimicrobial Agents in Combination with Plant Flavonoids to Prevent AMR

Combination therapy can enhance the antimicrobial effects of antimicrobial agents. In the past, people mainly focused on the aspect enhancing the antimicrobial effects of antimicrobial drugs through combination therapy, with less attention to the preventing effect to bacterial resistance. However, synergistic combination or enhancing the antimicrobial effects doesn’t mean that it can prevent AMR [

15,

20] although synergistic combination is beneficial for preventing bacterial resistance. As the situation of AMR becomes increasingly severe, combination therapy was increasingly researched for preventing AMR, and has been proved as an effective strategy [

12,

13,

14]. Regardless of whether the combinational effect is synergistic, indifferent, or antagonistic, one drug always can narrow the mutation selection window of another drug by increasing its dosage according to our previous work [

15,

20], thereby achieving the preventing effect to AMR according to the mutation selection window theory [

35]. Of course, the more synergistic the combined effect, the greater the potential to prevent AMR, and the easier it is to manipulate [

15,

20]. However, synergistic combinations are, after all, rare, and can only delay the spread of AMR. Moreover, the abuse of drug combinations not only cannot prevent AMR but may also accelerate the evolution and spread of AMR [

14,

36]. Given that flavonoids are widely distributed in plants and everyday foods such as vegetables and fruits contain plant flavonoids. these flavonoids not only have good safety, but also have widely antimicrobial effects, and synergistic effects when combined with antimicrobial agents. Therefore, it is worth encouraging to research on the combination therapy of plant flavonoids and antibacterial agents. Also, the plant flavonoids widely distributed in the diet of vegetables, fruits, and other foods will inevitably affect the

in vivo antibacterial effect of antibiotics and the resistance of pathogenic bacteria to antibiotics [

37], and this can be also used to prevent AMR.

3.4. Concept of the One Earth-One Health (OE-OH) to Prevent AMR

As mentioned above, many plant flavonoids have antimicrobial activity and exhibit widely synergistic effects when combined with clinical antibiotics. It is worth noting that these flavonoids are widely distributed in various plants across different habitats on the earth, including a variety of vegetables and fruits that are part of the diets of people in countries worldwide. Additionally, plants contain many other secondary metabolites, such as terpenoids, quinones, alkaloids, and other phenolic substances, many of which also have antimicrobial activity and present synergistic effects when combined with clinical antibiotics [

33,

34,

38,

39,

40,

41], such as ursolic acid, carnosic acid [

16], emodin, berberine, and so on. Therefore, all these plant secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activity not only would affect the

in vivo antimicrobial effects of clinical antibiotics and the susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria to clinical antibiotics if got into the human body [

33,

37,

39], but can also have a significant impact on the spread of resistant bacterial populations caused by the discharge of antibiotics into various environments if they are metabolites from environmental plants on the earth.

Similarly, various environmental microorganisms on the earth, including which in human and animal such as the gut microbiota, also can produce various secondary metabolites [

38]. These metabolites are not only important sources of clinical antibiotics, but also have the ability to inhibit or kill pathogenic bacteria. The

in vivo and

in vitro combined effects of antibiotics each other from environmental microorganisms also indicate that they may affect the susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria to other clinical antibiotics, thereby affecting the evolution of AMR. Therefore, various secondary metabolites with antibacterial activities, produced by microorganisms distributed in various environments on the earth, not only would affect the

in vivo antimicrobial effects of clinical antibiotics and the susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria to clinical antibiotics if they are metabolites from microorganisms in the human body, but can also have a significant impact on the spread of resistant bacterial populations caused by the discharge of antibiotics into various environments if they are metabolites from environmental microorganisms on the earth. In addition, microorganisms, plants and animals on the earth can degrade and/or utilize various clinical antibiotics emitted into the earth's environment, and which can reduce the accumulation of clinical antibiotics in the environment, thereby reducing the risk in the antibiotic resistance and its transmission around the environment. Thereout, the entire ecosystem of the earth can have a significant impact on the evolution of AMR, and which impact may be positive or negative.

It can be deduced that the complexity and enough buffering capacity of the earth's ecosystem determines its sufficient self-regulation ability in the evolution of AMR. So, a balance between humans and pathogenic microorganisms could be ensured as long as unremitting efforts are made to minimize the abuse of antibiotics and use the antibiotics as reasonably as possible. If this is achieved, the prediction from World Health Organization for AMR by 2050 would not become a reality. Based on these, together with the rules, key factor and important principle of drug combination for preventing AMR, we proposed the concept of One Earth-One Health (OE-OH) for preventing AMR at the 6th International Caparica Conference in Antibiotic Resistance 2024 (IC2AR 2024) held in Portugal in September 10, 2024.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Antimicrobial Agents and Plant Flavonoids

Ten antibacterial agents were used for the evaluation of combinational effect. Gentamicin sulfate (USP grade, 590 U/mg) was were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); ampicillin (96%) was purchased from Shanghai Acmec Biochemical Co.,Ltd. (Shanghai, China); linezolid (99%), colistin sulfate (≥19,000 U/mg), bacteriocin (>60 U/mg), streptomycin sulfate (98%), and levofloxacin (98%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); vancomycin hydrochloride (900 ug/mg) was purchased from Meryer (Shanghai) Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China);Roxithromycin (USP grade, >940 U/mg) and doxycycline (USP grade, 88~94%), analytical pure for 3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Thirty-seven plant flavonoids were used for the evaluation of combinational effect, and their chemical structures and sources were already reported in our previous work [

27]. Sophoraflavanone G (>98%) were purchased from Shanghai TopScience Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); naringin (95%), neohesperidin (≥98%), hesperidin (95%) were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); rutin (≥98%) and methyl-hesperidin (95%) was purchased from Shanghai Acmec Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); eriodictyol (≥98%), eriocitrin (≥98%), rhoifolin (≥98%) and licoflavone C (≥98%) were purchased from Wuhan ChemFaces Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China); hesperetin (97%), puerarin (98%), baicalein (98%), diosmin (95%), apigenin (≥95%), diosmetin (98%), galangin (98%), icaritin (>98%), isoliquiritigenin (98%), formononetin (98%) and naringenin (97%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); didymin (≥98%), 5-demethylnobiletin (≥98%), 4',5,7-trimethoxyflavone (≥98%), vitexin (≥98%) and isovitexin (≥98%) were purchased from Sichuan Weikeqi Biological Technology Co.,Ltd. (Sichuan, China); narirutin (98%), α-mangostin (>98.0%), licochalcone A (>98.0%), nobiletin (≥98.5%), orientin (99%), isoorientin (98%), tangeritin (≥98.5%), quercitrin (98%), sinensetin (98%), were purchased from Chengdu Push Bio-technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China); quercetin (97%) and glabridin (99.8%) was purchased from Meryer (Shanghai) Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

All the aforementioned compounds were stored at −20°C. Prior to use, they were dissolved in a specific volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or sterilized water (only for hydrochloride and sulfate of antibiotics), and then diluted with fresh sterilized Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) to achieve stock solutions with a concentration of 2048, 4096, 8192 or 16384 μg/mL. Following this, the stock solution was thoroughly mixed and further diluted to the desired concentrations with sterile MHB immediately. Additionally, the concentrations of DMSO in all test systems was maintained at less than 5.0%, while the blank controls contained 5.0% DMSO.

4.2. Media, Bacterial Strains and Growth Condition

Casein hydrolysate was purchased from Qingdao Hope Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China), and starch soluble, beef extract and agar powder were sourced from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). These reagents were employed in the preparation of the culture media. Mueller Hinton agar (MHA) was formulated with 17.5 g/L of casein hydrolysate, 1.5 g/L of starch soluble, 3.0 g/L of beef extract, and 17.0 g/L of agar powder, all dissolved in purified water, with a pH value adjusted to 7.40 ± 0.20. Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) was prepared without agar powder, following the same composition and protocol as MHA.

E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection in Manassas, VA, USA. These bacterial strains were preserved in MicrobankTM microbial storage systems, supplied by PRO-LAB diagnostics in Toronto, Canada, at a temperature of −20°C. Prior to use, both E. coli and S. aureus were cultured onto MHA plate at 37°C. Subsequently, isolated pure colonies from these plates were transferred into MHB and incubated at 37°C for 24 h on a rotary shaker (160 rpm). An aliquot of the overnight culture was then diluted 1:100 into fresh MHB and incubated at 37°C until it reached the exponential growth phase, ready for subsequent experimental procedures. MHB was used for the antimicrobial susceptibility tests. All TopPette Pipettors, both the 2~20 μL and 20~200 μL models, were purchased from DLAB Scientific Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

4.3. Susceptibility Test

The MICs of 37 plant flavonoids against both two pathogenic bacteria were reported in our previous work [

27], together with their MICs (μM) of unit converted, and the raw data of their MICs (μg/mL) were reported here. Similarly, all the MICs of antimicrobial against both two pathogenic bacteria were respectively determined according to the standard procedure described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [

42]. Briefly, the exponential phase culture was diluted with MHB to achieve a bacterial concentration approximately 1.0×10

6 CFU/mL, and then the MICs against

E. coli ATCC 25922 and

S. aureus ATCC 25923 were determined using the broth microdilution method on the 96-well plates (Shanghai Excell Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) in triplicate [

27]. Based on the preliminary MIC values of the compounds, the initial concentration of 1024, 2048 or 4096 μg/mL was respectively established for corresponding compound. Following a 24 h incubation of the 96-well plate at 35°C, 20 μL of MTT solution (4.0 mg/mL) was added into each well, the plate was thoroughly shaken, and then allowed to stand for 30 min at room temperature. The MIC, defined as the lowest concentration of the compound that completely inhibits bacterial growth in the micro-wells, was determined by the absence of color change, indicating no bacterial growth, in contrast to the sufficient bacterial growth observed in the blank wells, as described in reference [

28].

4.4. Checkerboard Assay

Depended on the MICs of plant flavonoids with exact MIC values and 9 antibacterial agents, checkerboard assay was designed to determine their FICIs in combinations against two pathogenic bacteria, according to previous method [

15], and the tests were performed on 96-well plates. Briefly, the dilutions from 8 to 1/16 MIC for plant flavonoids and antibacterial agents in the horizontal or vertical direction were prepared in a separate 96-well plate by twofold dilution method. Next, a 100 μL of dilution with different concentrations for two compounds in a combination were correspondingly added into the designed wells on another plate to obtain different proportions with the concentrations from 4 to 1/32 MIC of each compound. Another, columns 11 and 12 only contained MHB with 5 × 10

5 cfu/mL bacterial strains were used as blank controls. When the microbial growth in blank wells was good at 35 °C for 24 h, the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of bacterial growth visibly inhibited in the micro-wells. If necessary, MTT stain was used to clearly observe the results like section 4.3. The MICs of two compounds in alone were respectively observed from row A and column 1, and the MICs of two compounds in combinations were obtained from wells B2 to H8.

The FICs were calculated as following formula:

Here, A and B were two compounds in a drug combination, and are respectively the MICs of A in a combination and in alone, and and are respectively the MICs of B in a combination and in alone.

The combining effect interpreted as follows: synergy, FICI ≤ 0.5; indifference, 0.5 < FICI ≤ 4.0; and antagonism, FICI > 4.0 [

43].

5. Conclusions

Based on above results, analyses and discussion, it was concluded as follows: (1) plant flavonoids in combination with antibiotics presents extensive synergistic effects, and it is easier to discover synergistic combinations consisted of plant flavonoids and clinical antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria than Gram-positive ones; (2) the combined effects of plant flavonoids with antibiotics follow the selection rule of antibacterial agents for synergistic combinations, and this is likely due to the main mechanism of plant flavonoids damaging the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria and its multiple mechanisms on Gram-negative ones including the membrane damage and the inhibition to DNA gyrase; (3) microorganisms, plants and animals on the earth and their various metabolites would definitely impact on the evolution of AMR, meanwhile the ecosystem of the earth also have enough buffering capacity and self-regulation ability to the fight between human and pathogenic microorganisms. Based on these, the concept of One Earth-One Health (OE-OH) was proposed for preventing AMR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Y.; methodology, G.Y.; software, G.Y. and F.L.; validation, G.Y., F.L., Y.Y., Y.W. and L.Z.; formal analysis, G.Y., F.L., L.Z. and Y.Y.; investigation, G.Y., F.L., Y.Y., Y.W., L.Z., J.Z., Y.Q. and A.F.; resources, G.Y.; data curation, G.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Y. F.L., Y.Y., Y.W. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, G.Y.; visualization, G.Y., Y.Y., J.Z. and Y.Q.; supervision, G.Y.; project administration, G.Y.; funding acquisition, G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82073745 and 82360691).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The MICs (μg/mL) against bacteria presented in

Table 2 are the raw ones of the MICs (μM) of 37 plant flavonoids in

Table 1 reported in our previous work [

27], and here these raw data were reorganized and presented in

Table 2 for the reference of the checkerboard experiment in section 4.4. The structures of 37 plant flavonoids can be found in

Figure 1 reported by us at

MDPI, and are available from the link at

https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/17/3/292.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- MacLean, R.C.; Millan, A.S. The evolution of antibiotic resistance. Science 2019, 365, 1082–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, A. , Esiovwa, R., Connolly, J., Hursthouse, A., Henriquez, F. Antimicrobial resistance as a global health threat: The need to learn lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Policy 2022, 13, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.E.J.; Ward, M.J. Microbiology. Sources of antimicrobial resistance. Science 2013, 341, 1460–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan R, Sridhar D, Blaser M,; Wang, M.; Woolhouse, M. Achieving global targets for antimicrobial resistance. Science 2016, 353, 874–875. [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Opportunities for natural products in 21st century antibiotic discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbach, M.A. Combination therapies for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K. Improving known classes of antibiotics: an optimistic approach for the future. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepekule, B.; Uecker, H.; Derungs, I.; Frenoy, A.; Bonhoeffer, S. Modeling antibiotic treatment in hospitals: A systematic approach shows benefits of combination therapy over cycling, mixing, and mono-drug therapies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, M.A.; Brown, E.D. Drug repurposing for antimicrobial discovery. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuretzbacher, U.; Piddock, L.J. Non-traditional antibacterial therapeutic options and challenges. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejim, L.; Farha, M.A.; Falconer, S.B.; Wildenhain, J.; Coombes, B.K.; Tyers, M.; Brown, E.D.; Wright, G.D. Combinations of antibiotics and nonantibiotic drugs enhance antimicrobial efficacy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyers, M.; Wright, G.D. Drug combinations: a strategy to extend the life of antibiotics in the 21st century. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochado, A.R.; Telzerow, A.; Bobonis, J.; Banzhaf, M.; Mateus, A.; Selkrig, J.; Huth, E.; Bassler, S.; Beas, J.Z.; Zietek, M. Species-specific activity of antibacterial drug combinations. Nature 2018, 559, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Yuan, G.; Wang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, M. Synergistic combination of two antimicrobial agents closing each other's mutant selection windows to prevent antimicrobial resistance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7237–7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Li, S.; Yuan, G.; Yi, H.; Zhang, T. Antibacterial effects of carnosic acid or α-mangostin combined with various antibiotics with different mechanisms, to Staphylococcus aureus. Chin. J. Antibio. 2023, 48, 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Górniak, I.; Bartoszewski, R.; Króliczewski, J. Comprehensive review of antimicrobial activities of plant flavonoids. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, F.; Khameneh, B.; Iranshahi, M.; Iranshahy, M. Antibacterial activity of flavonoids and their structure-activity relationship: An update review. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Hao, Z.; Ding, S.; Panichayupakaranant, P.; Zhu, K.; Shen, J. Plant natural flavonoids against multidrug resistant pathogens. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Yuan, G.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y. Drug combinations to prevent antimicrobial resistance: various correlations and laws, and their verifications, thus proposing some principles and a preliminary scheme. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan G.; Yi H.; Zhang L.; Guan Y.; Li S.; Lian F.; Fatima A.; Wang Y. Drug combinations to prevent antimicrobial resistance: theory, scheme and practice. Book of abstracts, 6th International Caparica Conference on Antibiotic Resistance. Caparica, Portugal, 8th – 12th September 2024; Capelo-Martinez J.L.; Santos H.M.; Oliveira E.; Fernández J.; Lodeiro C.; Publisher: PROTEOMASS Scientific Society, Caparica, Portugal, Keynote Presentations 8, pp. 93.

- Stone, K.J.; Strominger, J.L. Mechanism of action of bacitracin: complexation with metal ion and C55-isoprenyl pyrophosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1971, 68, 3223–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovinskaya, M.A.; Pai, R.D.; Zhang, W.; Schuwirth, B.S.; Holton, J.M.; Hirokawa, G.; Kaji, H.; Kaji, A.; Cate, J.H. Structural basis for aminoglycoside inhibition of bacterial ribosome recycling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Cukras, A.R.; Rogers, E.J.; Southworth, D.R.; Green, R. Mutational analysis of S12 protein and implications for the accuracy of decoding by the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 374, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maaland, M.G.; Papich, M.G.; Turnidge, J.; Guardabassi, L. Pharmacodynamics of doxycycline and tetracycline against Staphylococcus pseudintermedius: proposal of canine-specific breakpoints for doxycycline. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 3547–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, C.; Roberts, J.A.; Muller, L. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oxazolidinones. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 57, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xia, X.; Fatima, A.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, G.; Lian, F.; Wang, Y. Antibacterial activity and mechanisms of plant flavonoids against gram-negative bacteria based on the antibacterial statistical model. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Xia, X.; Guan, Y.; Yi, H.; Lai, S.; Sun, Y.; Cao, S. Antimicrobial quantitative relationship and mechanism of plant flavonoids to gram-positive bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Guan, Y.; Yi, H.; Lai, S.; Sun, Y.; Cao, S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of plant flavonoids to gram-positive bacteria predicted from their lipophilicities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadio, G.; Mensitieri, F.; Santoro, V.; Parisi, V.; Bellone, M.L.; De Tommasi, N.; Izzo, V.; Dal Piaz, F. Interactions with microbial proteins driving the antibacterial activity of flavonoids. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Xia, X.; Yuan, G.; Li, S.; Deng, B.; Luo, X. Quinone pool, a key target of plant flavonoids inhibiting gram-positive bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Roy Choudhury, M.; Yang, X.; Benoit, S.L.; Womack, E.; Van Mouwerik Lyles, K.; Acharya, A.; Kumar, A.; Yang, C.; Pavlova, A.; et al. Restoring and enhancing the potency of existing antibiotics against drug-resistant gram-negative bacteria through the development of potent small-molecule adjuvants. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, A.C.; McBain, A.J.; Simões, M. Plants as sources of new antimicrobials and resistance-modifying agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Herranz-López, M.; Micol, V. Antibacterial plant compounds, extracts and essential oils: An updated review on their effects and putative mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drlica, K.; Zhao, X. Mutant selection window hypothesis updated. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gefen, O.; Ronin, I.; Bar-Meir, M.; Balaban, N.Q. Effect of tolerance on the evolution of antibiotic resistance under drug combinations. Science 2020, 367, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Souza, M.V.; Dias, C. G, Ferreira-Marçal, P.H. Interactions of natural products and antimicrobial drugs: investigations of a dark matter in chemistry. Biointerface Res. Appl 2018, 8, 3259–3264. [Google Scholar]

- Gyawali, R.; Ibrahim, S.A. Natural products as antimicrobial agents. Food Control 2014, 46, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, R.; Coppo, E.; Marchese, A.; Daglia, M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Nabavi, S.F.; Nabavi, S.M. Phytochemicals for human disease: An update on plant-derived compounds antibacterial activity. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 196, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchino, S.A.; Butassi, E.; Liberto, M.D.; Raimondi, M.; Postigo, A.; Sortino, M. Plant phenolics and terpenoids as adjuvants of antibacterial and antifungal drugs. Phytomedicine 2017, 37, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisuria, V.B.; Okshevsky, M.; Déziel, E.; Tufenkji, N. Proanthocyanidin interferes with intrinsic antibiotic resistance mechanisms of gram-negative bacteria. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2202641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 10th ed.; Approved Standards, CLSI document M07-A10; Clinical and Laboratory and Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2015.

- Odds, F.C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).