Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- -

- -

- No-tillage: Improves water retention, reduces soil erosion, and increases soil organic matter.

- -

- Agroforestry: Boosts biodiversity and positively impacts water, climate, and ecological balance [3].

- -

- Precision farming: Optimizes resource use (water, energy, fertilizers, plant protection products) through accurate monitoring [4].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

2. Materials and Methods

3. Review

3.1. Agricultural Microbiome

3.2. Sustainable Green Chemistry

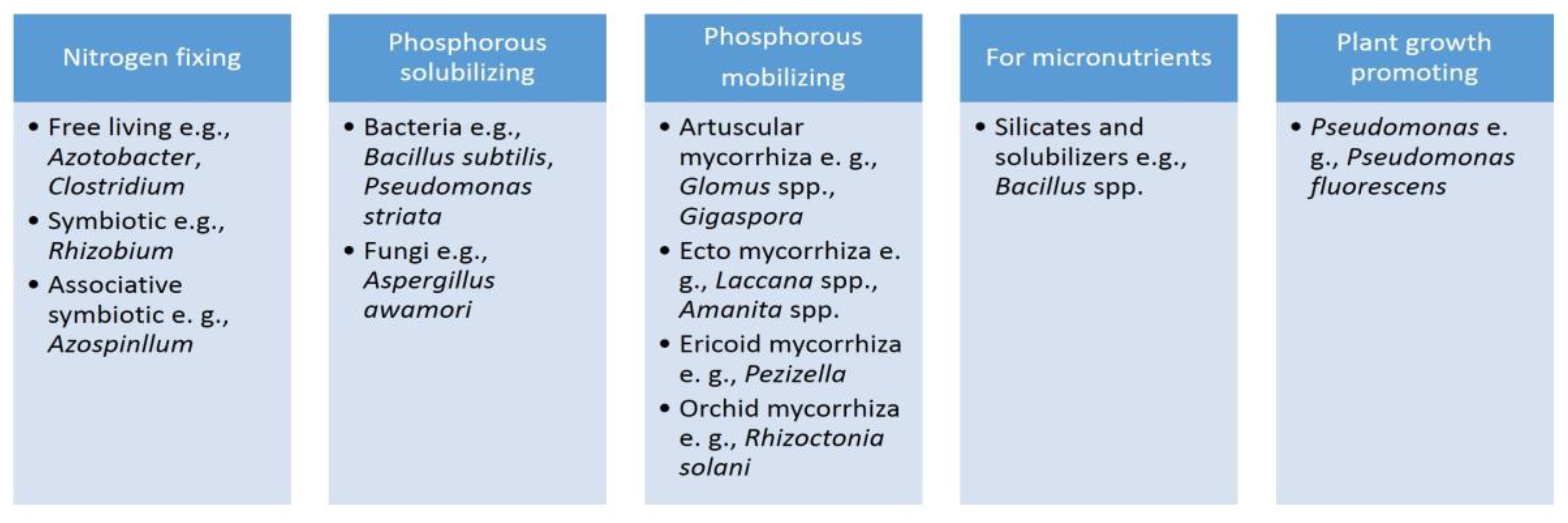

3.3. Biofertilizers

3.3. Development of EM and Biofertilizer Formulation

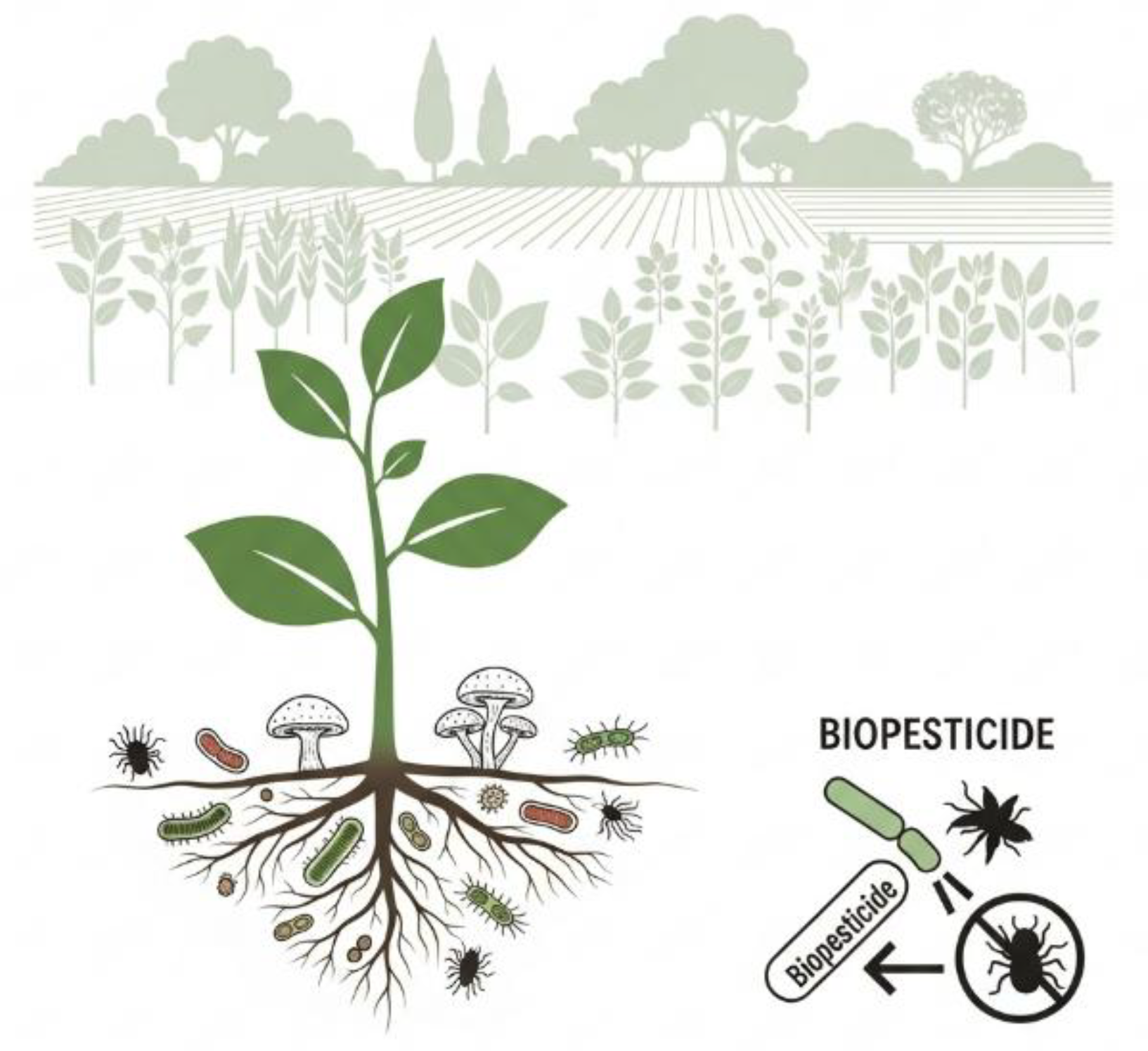

3.4. Biopesticides

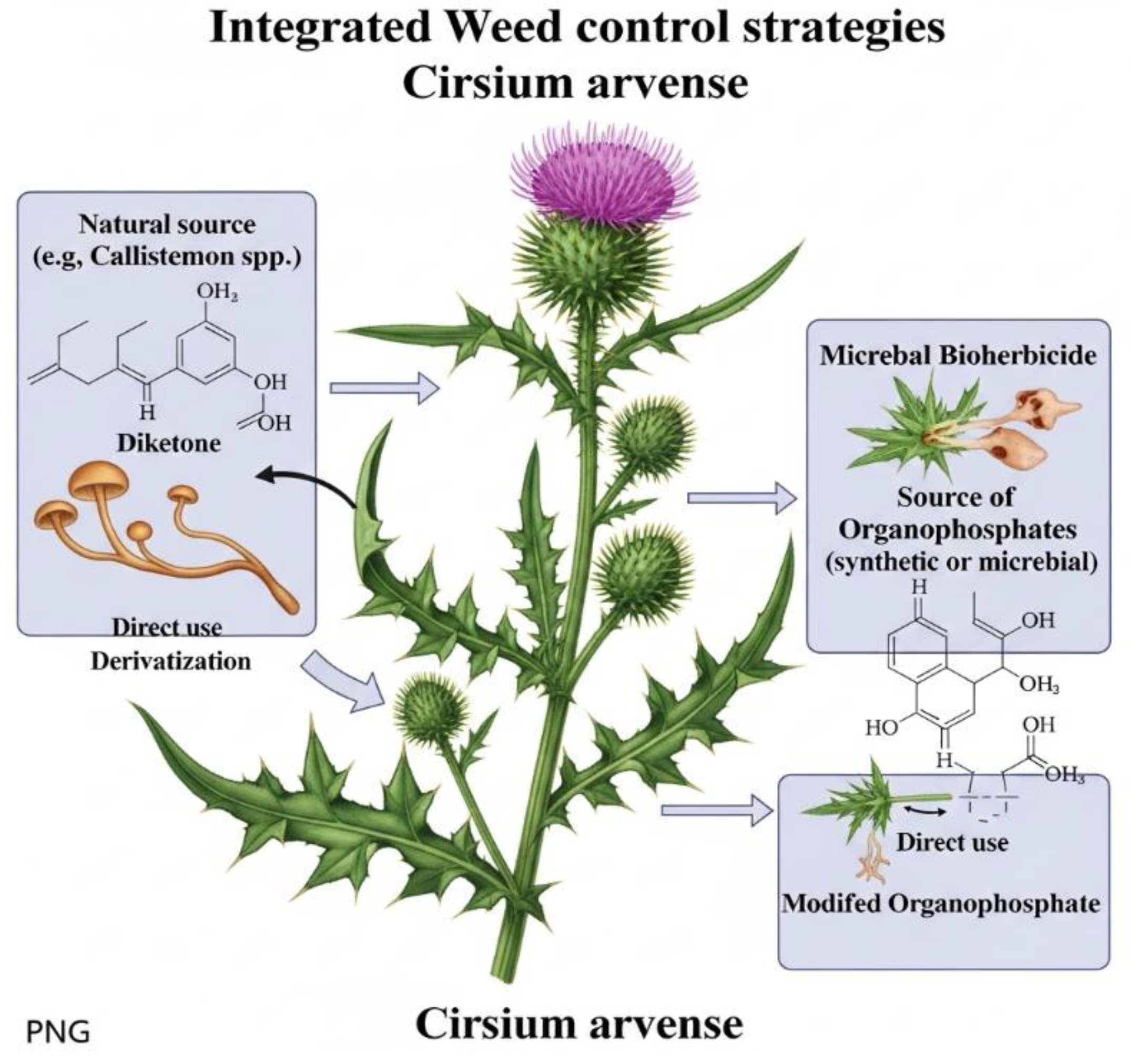

3.5. Bioherbicides

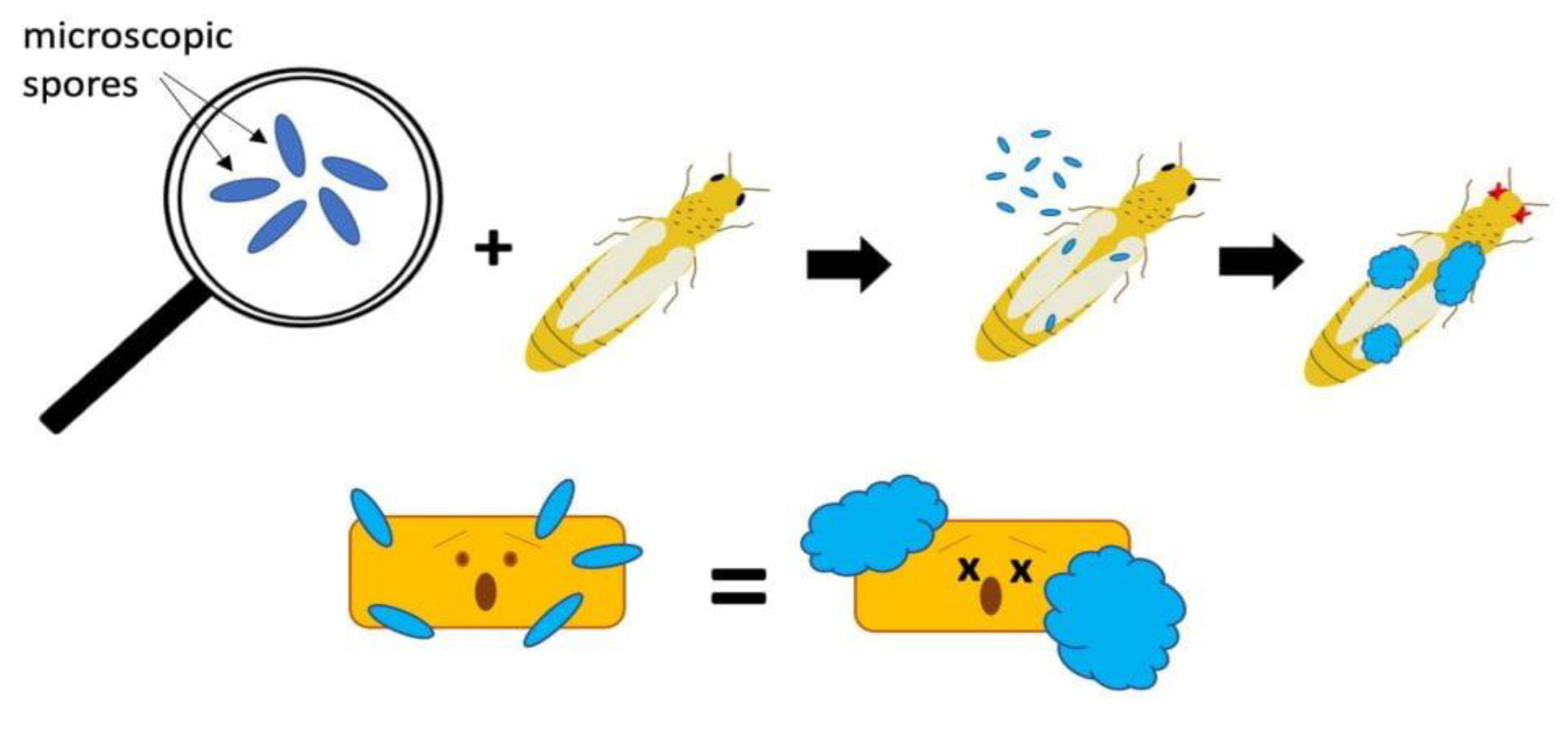

3.6. Bioinsecticides

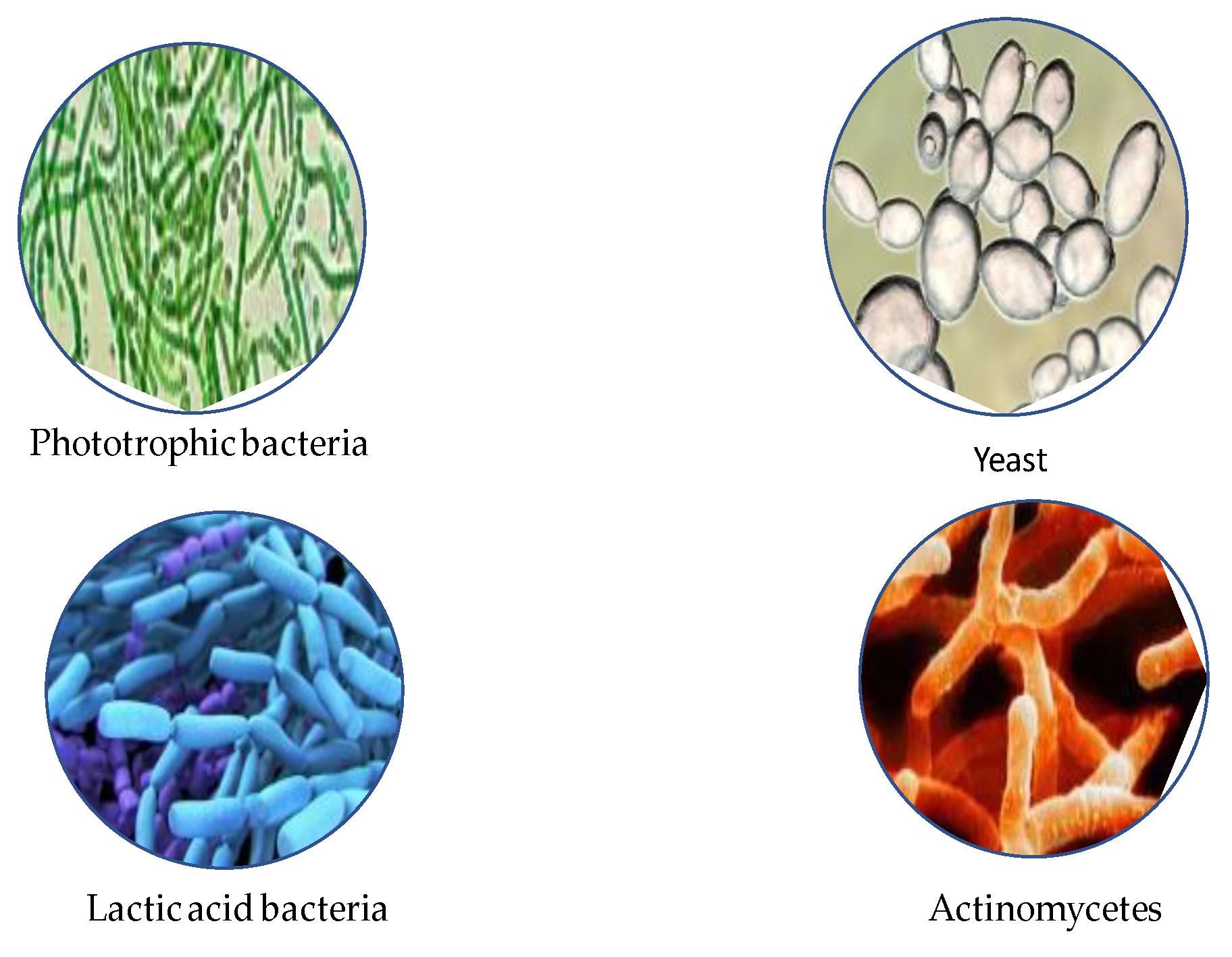

3.7. Effective Microorganisms

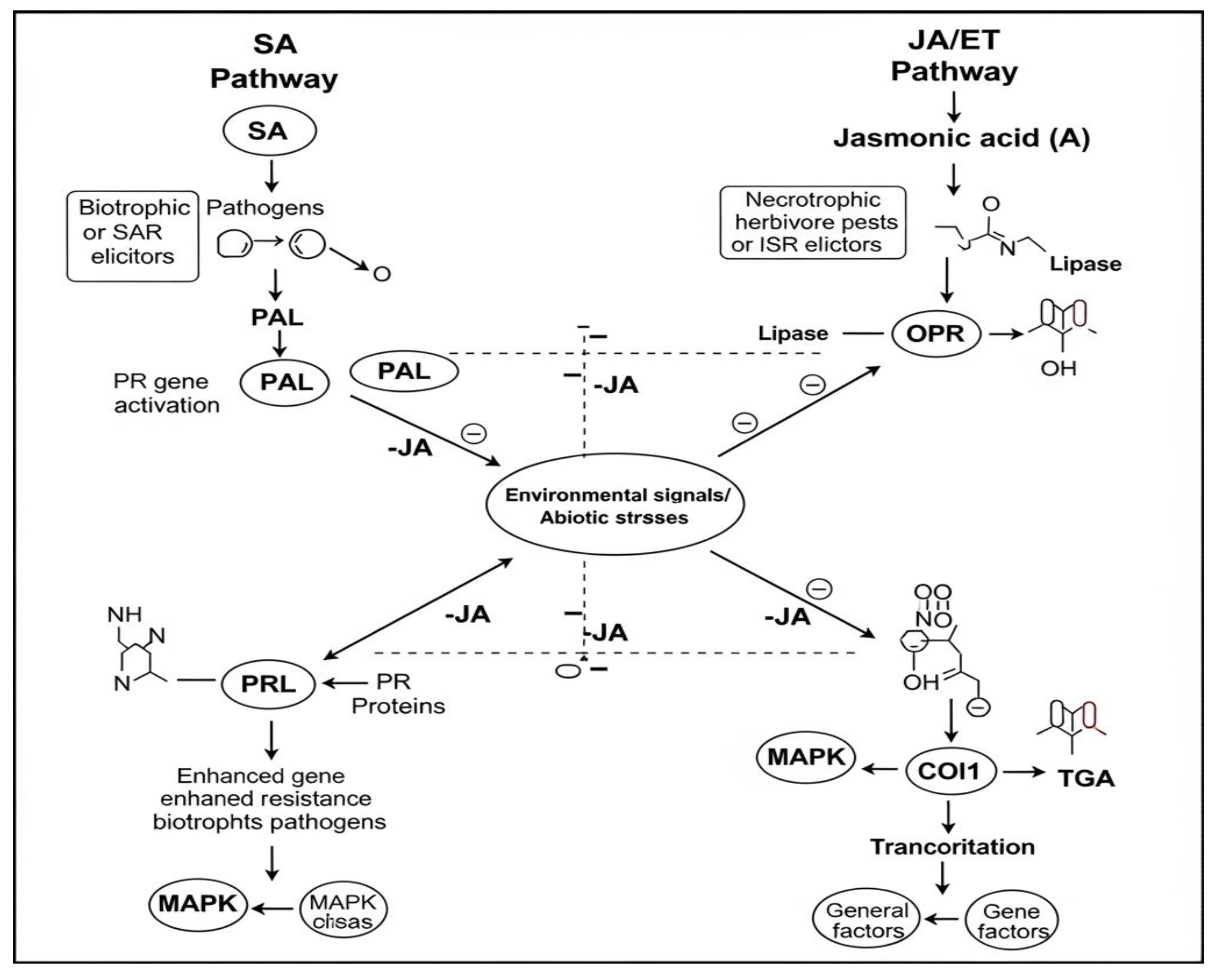

3.7.1. Microorganisms in the Influence of Plant Resistance

3.7.2. EM in Plant Cultivation

3.7.3. Microbiological Preparations in Composting

3.7.4. EM in Food Processing

3.7.5. Mycorrhizal Preparations

3.7.6. Microorganisms in Aerobic Nitrification and Denitrification

3.7.6. EM and Germanium (Ge)

3.7.8. Inhibition of the Growth of Various Pathogenic Microorganisms Using EM

3.8. Microbiological Organisms in Sustainable Agriculture

3.9. Soil and Microorganisms: Basics and Impact of EM

3.8.1. Soil Microorganisms Enhancing Plant Health

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMF | an effective plant-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| AOA | ammonia-oxidizing archaea |

| AOB | ammonia-oxidizing bacteria |

| COD | chemical oxygen demand |

| DO | dissolved oxygen |

| DS | Drought Stress |

| EM | effective microorganisms |

| EPA | The Environmental Protection Agency |

| EPS | extracellular polymeric substance |

| FF | French fries |

| GV | Granulosis’s |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein fraction |

| HN-AD | heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification |

| HNADM | heterotrophic nitrification with oxygen denitrifying microorganisms |

| HRAC | Herbicide Resistance Action Committee |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein fraction |

| LEMs | effective local microorganisms |

| MBBR | moving bed biofilm reactor |

| MBR | membrane bioreactor |

| MLR | Maximum Residue Levels |

| MoA in Pesticides | Mode of Action |

| NPV | Nuclear polyhedrosis viruses |

| NOB | nitrite-oxidizing bacteria |

| Nod | biofertilizers containing rhizobia Nod |

| PBS | polybutylene succinatepn |

| PC | Potato Chips |

| PGPR | Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria) |

| PP | pomelo peel |

| PSI | Photosystem I |

| PSII | Photosystem II bs |

| QS | secretion of quorum sensing |

| RSM | response surface methodology |

| SBBR | sequencing batch biofilm reactor |

| SBR | sequencing batch reactor |

| SHARON | Single reactor High activity Ammonium Removal Over Nitrite |

| SND | simultaneous heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification |

| SwF | seaweed extracts |

| tEM | thermoacids of effective microorganisms |

| tEMA | thermoacids of effective microorganisms with shading |

| tEMB | thermo acids of effective microorganisms without shading |

| TIN | total inorganic nitrogen |

| TN | total nitrogen |

| TP | total phosphorus |

References

- Kucharski J, Jastrzębska E. The role of effective microorganisms in shaping the microbiological properties of soil. Ecological Engineer, 2005, 12: 295-296. (in Polish).

- Shah K.K., Tripathi S., Tiwari I., Shrestha J., Modi B., Paudel N., Das BD., Role of soil microbes in sustainable crop production and soil health: A review. Agricultural Science and Technology, 2021, 13(2), 109-118. [CrossRef]

- Sarveswaran S, Vishal Johar*, Vikram Singh and Ragunanthan C. Agroforestry: A Way Forward for Sustainable Development. Eco. Env. & Cons. 2023, 29 (August Suppl. Issue): S300-S309. ISSN 0971–765X. [CrossRef]

- Li, X, Guo, Q, Wang, Y, Xu, J, Wei, Q, Chen, L, Liao, L. Enhancing Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal by Applying Effective Microorganisms to Constructed Wetlands. Water, 2020, 12, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun M, Coskun M, Cayir A. Frequencies of micronuclei (MNi), nucleoplasm bridges (NPBs), and nuclear buds (NBUDs) in farmers exposed to pesticides in Çanakkale, Turkey. Environ Int, 2011, 1:93-96.

- Wong, R. H, Chang S.Y, Ho S.W. Polymorphisms in metabolic GSTP1 and DNA-repair XRCC1 genes with an increased risk of DNA damage in pesticide-exposed fruit growers. Mutat Res 2008,654:168-75.

- Sawicka B., Vambol V., Krochmal-Marczak B., Messaoudi M, Skiba D., Pszczółkowski, P., Barbaś, P., Farhan A.K. Green Technology as a Way of Cleaning the Environment from Petroleum Substances in South-Eastern Poland. Frontier Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2022; 14(4): 28. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Green Technology Innovation, Energy Consumption Structure and Sustainable Improvement of Enterprise Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU), No. 540/2011, OJ L 153 of 11.6.2011: 1–186.

- European Food Safety Authority. EFSA Journal 2012, 10 (10): sf101, https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/sf101 (accessed 17/12/2021).

- European Food Safety Authority, Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance gibberellins. EFSAJ 2012b, 10(1):2502–2551.

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. tenebrionis strain NB-176. EFSA Journal 2013a, 11(1): 3024–3059.

- European Food Safety Authority, Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance carbon dioxide. EFSA Journal 2013b, 11(5): 3053–3153.

- European Food Safety Authority, Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance orange oil. EFSA Journal 2013c, 11(2): 3090–3144.

- European Union Pesticides Database (2019). (Online). Available: http://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/protection/evaluation/database_act_subs_en.html (accessed 02.10.2021).

- Ortiz, A., Sansinenea, E. Chapter 1. Bacillus thuringiensis based biopesticides for integrated crop management, Editor(s): Amitava Rachit, Vijay Singh Meena, P.C. Abhilash, B.K. Sarma, H.B. Singh, Leonardo Fraceto, Manoj Parihar, Anand Kumar Singh, [In:] Advances in Bio-inoculant Science, Biopesticides, Woodhead Publishing, 2022, Pages 1-6, ISBN 9780128233559. [CrossRef]

- Kapka-Skrzypczak L, Cyranka M, Kruszewski M, Turski W.A. Plant protection products and farmers’ health - biomarkers and the possibility of using them to assess exposure to pesticides. Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu, 2011, 17(1): 28-32. (in Polish).

- Skiba D., Sawicka B., Pszczółkowski P., Barbaś P., Krochmal-Marczak. Impact of crop management and weed control systems of very early potatoes on weed infestation, biodiversity, and tuber health safety. Life, 2021, 11(826): 33. [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, C. Genotoxicity of pesticides: a review of human biomonitoring studies. Mutat Res, 2003, 3:251-72.

- Barbaś P., Sawicka B. Comparison of the profitability of various methods of weed infestation in edible potato cultivation. Problems of Agricultural Engineering, 2017, 2 (96): 5–15. ISSN 1231-0093 (in Polish).

- Nowacka A, Gnusowski B, Dąbrowski J. Remains of protection measures in agricultural crops (2006). The remains. Progress in Plant Protection/Postępy w Ochronie Roślin 47(4):79-90. (in Polish).

- Martínez-Valenzuela C, Gómez-Arroyo S, Villalobos-Pietrini R. Genotoxic biomonitoring of agricultural workers exposed to pesticides in the north of Sinaloa State, Mexico. Environ Int, 8:1155-9.

- Bortoli G.M, Azevedo M.B, Silva L.B. Cytogenetic biomonitoring of Brazilian workers exposed to pesticides. Micronucleus analysis in buccal epithelial cells of soybean growers. Mutat Res, 2009, 1-2: 1-4.

- Crestani M, Menezes Ch, Glusczak L, Santos Miron D. Effects of Clomazone Herbicide on biochemical and histological aspects of silver catfish (Rhamdia quelen) and recovery pattern. Chemosphere, 2007, 67: 2305-2311.

- Santos MD, Crestani M, Shettinger M. R, Morsch V.M. Effects of the herbicides clomazone, quinclorac, and metsulfuron methyl on acetylcholinesterase activity in the silver catfish (Rhamadia quelen). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2005, 6: 398-403.

- Anonimous. Assessment of the effectiveness of plant protection products. Resistance risk analysis. Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes, 2002, PP 1/213(2).

- Alam A, Bibi F, Deshwal K, Sahariya A, Bhardwaj C, Emmanuel I. Biofortification of primary crops to eliminate latent hunger: an overview. Natural resources for human health. 2022, 2(1): 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Pan Y, Q Xi, Zhang S, Zhi Ch, Meng H, Cheng Z. Effects of exogenous germanium and effective microorganisms on germanium accumulation and nutritional qualities of garlic (Allium sativum L.), Scientia Horticulture, 2021, 283: 110114. [CrossRef]

- Gupta K. Profiles of the bio-fertilizer industry on the market. (In:) Biofertilizers: research and impact. Editors: Inamuddin, Mohd Imran Ahamed, Rajender Boddula, Mashallah Rezakazemi, 2021a. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K, Balyan, H.S, Sharma, S, Kumar, R. Biofortification and bioavailability of Zn, Fe and Se in wheat: present status and future prospects. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 2021b, 134(1): 1-35. [CrossRef]

- El-Ghwas, DE. , Elkhateeb WA., Daba G, M. Fungi: The Next Generation of Biofertilizers. Environmental Science Archives, 2022, 2(1), 34-41. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Biswas SK, Nagar D, Lal K, Singh J. Effect of biofertilizer growth parameters and potato yield. inside J. Curr. Microbiol. Regret. Science, 2017, 6(5): 1717-1724.

- De Assis RMA, Carneiro JJ, Medeiros APR, de Carvalho AA, da Cunha Honorato A, Carneiro MAC, Bertolucci, SKV, Pinto JEBP. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and organic manure enhance growth and accumulation of citral, total phenols, and flavonoids in Melissa officinalis L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 158: 112981. [CrossRef]

- Mathur S, Tomar RS, Jajoo A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) protect photosynthetic apparatus of wheat under drought stress. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 139:227–238. [CrossRef]

- Mathur S, Jajoo A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi protect maize plants from high temperature stress by regulating photosystem II heterogeneity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 143: 111934. [CrossRef]

- Igiehon NO, Babalola OO, Cheseto X, Torto, B. Effects of rhizobia and Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on yield, size distribution and fatty acid of soybean seeds grown under drought stress. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242: 126640. [CrossRef]

- Paravar A, Farahani SM, Rezazadeh A. Lallemantia response to drought stress and the use of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Crops and Industrial Products 2021,172: 114002.

- Plouznikoff K, Asins MJ, de Boulois HD, Carbonell EA, Declerck S. Genetic analysis of tomato root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124:933–946. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Abdelraouf E, Bicego B, Joshi V, Garcia, AG. Deficit irrigation: a viable option for sustainable confection sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) production in the semi-arid US. Irrig. Sci. 36: 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Liu X, Zhang Q, Li S, Sun Y, Lu W, Ma C. Response of alfalfa growth to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria under different phosphorus application levels. AMB Express 2020, 10: 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarzadeh Z, Mohsenzadeh S, Rowshan V, Zarei M. Mitigation of water deficit stress in Dracocephalum moldavica L. by symbiotic association with soil microorganisms. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272: 109549. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-González MI, Matilla MA, Quesada JM, Ramos JL, Espinosa-Urgel M. Using genomics to discover bacterial lifestyle determinants in the rhizosphere (in:) Molecular Microbiological Ecology of the Rhizosphere, Editors: Frans J. de Bruijn. Issue 1, March 18, 2013, ISBN: 9781118296172. [CrossRef]

- Mgomi FC, Zhang B-X, Lu Ch-L, Yang Z-Q, Yuan L. Novel biofilm-inspired encapsulation technology enhances the viability of probiotics during processing, storage, and delivery, Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2025, 160, 105032, ISSN 0924-2244. [CrossRef]

- Ferrando L, Rariz G, Martínez-Pereyra A, Fernández-Scavino A, Endophytic diazotrophic communities from rice roots are diverse and weakly associated with soil diazotrophic community composition and soil properties, Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2024, 135(7),157. [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J. , Niewiadomska J. Głuchowska K. Kaczmarek D., Impact of fertilizers and soil properties in the case of Solanum tuberosum L. during conversion to organic farming. Applied ecology and Environmental Research, 2017, 15(4),369-839.

- Council Directive 91/414/EEC of 15 July 1991 concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market. OJ L 230, 19.8.1991: p. 1–32.

- Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the placing of plant protection products on the market and repealing Council Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC103352 (accessed 14.12.2022.

- Villaverde JJ, Sevilla-Morán B, Sandín-España P, López-Goti C, Alonso-Prados JL. Biopesticides in the framework of the European. Pesticide Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009. Pest Manag Sci 70: 2-5.

- Lu Ch, Zhang Z, Guo P, Wang R, Liu T, Luo J, Hao B, Wang Y, Guo W. Synergistic mechanisms of bioorganic fertilizer and AMF driving rhizosphere bacterial community to improve phytoremediation efficiency of multiple HMs-contaminated saline soil, Science of The Total Environment, 2023, 883: 163708, ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. The Application of Genomics in Agriculture. Agricultural Science and Food Processing, 2025, 2(1), 26–46. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xue, F.; Yu, S.; Du, S.; Yang, Y. Subcritical Water Extraction of Natural Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Z-Z, Zeng D-W, Zhu Y-F, Zhou M-H, Kondo A, Hasunuma T, Zhao X-Q, Fermentation design and process optimization strategy based on machine learning, BioDesign Research, 2025, 7(1): 100002, ISSN 2693-1257. [CrossRef]

- Sawicka B, Egbuna Ch, Nayak AK, Kala S. Chapter 2. Plant diseases, pathogens, and diagnosis. PART I. Green approach to pest and disease control (in:) Natural Remedies for Pest, Disease and Weed Control. Edited by Chukwuebuka Egbuna, Barbara Sawicka, ELSEVIER, Academic Press, London, 1-16, 2020. ISBN: 978-0-12-819304-4. [CrossRef]

- Crandall, L.; Zaman, R.; Duthie-Holt, M.; Jarvis, W.; Erbilgin, N. Navigating the Semiochemical Landscape: Attraction of Subcortical Beetle Communities to Bark Beetle Pheromones, Fungal and Host Tree Volatiles. Insects 2025, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han X, Li S, Zeng Q, Sun P, Wu D, Wu J, Yu X, Lai Z, Milne RJ, Kang Z, Xie K, Li G. Genetic engineering, including genome editing, for enhancing broad-spectrum disease resistance in crops, Plant Communications, 2025, 6(2):101195, ISSN 2590-3462. [CrossRef]

- Vaitkeviciene, N. The Effect of Biodynamic Preparations on the Accumulation of Biologically Active Compounds in the Tubers of Different Genotypes of Ware Potatoes. Ph.D. Thesis, Agricultural Sciences, Agronomy (01A), ASU, Akademija, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2016, pp. 212.

- Vaitkeviciene, N, Jariene, E, Danilcenko, H, Sawicka, B. Effect of biodynamic preparations on the content of some mineral elements and starch in tubers of three colored potato cultivars. J. Elem. 2016, 21, 927–935. [Google Scholar]

- Keidan M. Optimization of winter oilseed rape technological parameters in the organic farming system. PhD thesis, Aleksandras Stulginskis University, Kaunas, pp. 221.

- Adetunji, CO., Oloke, J.K., Phazang P., Sarin N.B. Influence of eco-friendly phytotoxic metabolites from Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae C1136 on physiological, biochemical, and ultrastructural changes on tested weeds. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020, 27(9): 9919-9934.

- Levickienė D, Jarienė, E, Gajewski, M, Danilčenko, H, Vaitkevičienė N, Przybył JL, Sitarek M. Influence of harvest time on biologically active compounds and antioxidant activity in mulberry leaves in Lithuania. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 2017, 45(2): 431-436.

- Levickienė D. The Influence of the Biodynamic Preparations on the Soil Properties and Accumulation of Bioactive Compounds in the Leaves of White Mulberry (Morus alba L.). PhD thesis, Aleksandras Stulginskis University, Kaunas 2018: pp. 212.

- Werle R, Lowell D, Sandeln LD, Buhler DD, Hartzler RG, Lundqvists LJ. Predicting the emergence of 23-year-old annual weed species. Weed Science 2014, 62 (2): 267-279. [CrossRef]

- Stanek-Tarkowska, J.; Szostek, M.; Rybak, M. Effect of Different Doses of Ash from Biomass Combustion on the Development of Diatom Assemblages on Podzolic Soil under Oilseed Rape Cultivation. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouajio M, McGiffen ME, Hembree, KJ. Tolerance of tomato cultivars to velvetleaf interference. Weed Sci 2009, 49(379): 91-98, 10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049(0091: TOTCTV)2.0.CO, 2 380.

- Goldwasser Y, Lanini W, Wrobel R. Tolerance of tomato varieties to lespedeza dodder. Weed Sci 2009, 49:520-523. [CrossRef]

- Andrew IKS, Storkey J, Sparke D.L. A review of the potential for competitive cereal cultivars as a tool in integrated weed management. Weed Res 2015, 55, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, S.O. , Pan, Z., Bajsa-Hirschel, J., Douglas, B.C. The potential future roles of natural compounds and microbial bioherbicides in weed management in crops. Adv Weed Sci, 40(1), e020210054, Jan. 2022.

- Macías FA, Mejpias FJR, Molinillo JMG. Recent advances in allelopathy for weed control: from knowledge to applications. Pest Manag Sci 2019, 75, 2413–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq M, Bajwa AA, Cheema SA, Cheema ZA. Application of allelopathy in crop production Int. J. Agric. Biol., 2013, 15(389): 1367–1378. [CrossRef]

- Portela VO, Moro A, Santana NA, Baldoni DB, de Castro IA, Antoniolli ZI, Dalcol II, Seminoti Jacques RJ. First report on the production of phytotoxic metabolites by Mycoleptodiscus indicus under optimized conditions of submerged fermentation. Environ Technol. 2022 43(10):1458-1470. [CrossRef]

- Boligłowa E. Potato protection against diseases and pests using Effective Microorganisms (EM) with herbs. (In:) Selected ecological issues in modern agriculture. Ed. Z. Zbytek, Publisher: PIMR, Poznań: 165–170, 2005. (in Polish).

- Janas R. Possibilities of using effective microorganisms in ecological systems of crop production. Problems of Agriculure Engineering 2009, 3: 111-119. (in Polish).

- Ji B, Hu H, Zhao Y, Mu X, Liu K, Li C. Effects of deep tillage and straw returning on soil microorganism and enzyme activities. Sci. World J. 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczyk M, Szmigiel A, Ropek, D. Effectiveness of potato protection production using selected insecticides to combat potato beetles (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say). Acta Scientiarum Polonorum s. Agricultura 2009, 8(4): 5-14.

- Kumar A, Singh VK, Singh P, Mishr K. Purification of environmental pollutants via microbes. 1st edition, Editors: Ajay Kumar Vipin, Kumar Singh, Pardeep Singh, Virendra Kumar Mishra, Woodhead Publishing, eBook ISBN: 9780128232071, Paperback ISBN: 978012821199, 2020: pp. 474.

- Daniel C, Wyssa E. Field applications of Beauveria bassiana to control the Rhizolites cerasi fruit fly. Journal of Applied Entomology 2010, 134 (9-10): 675-681. [CrossRef]

- Macías FA, Rodríguez MJ, Molinillo MG. Recent advances in weed control allopathy. From knowledge to application. Pest Control Science 75 (9). [CrossRef]

- Rudeen ML, Jaronski ST, Petzold-Maxwell JL, Gassmann AJ. Entomopathogenic fungi in cornfields and their potential to fight the larvae of western corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013 Nov,114(3):329-32. [CrossRef]

- Reddy GVP, Tangtrakulwanich K, Wua S, Miller JH, Ophus VL, Prewett J, Jaronski ST. Evaluation of the effectiveness of entomopaths in the control of wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae) on spring wheat. J Invertebr Pathol 2014, 120: 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Trawczyński C., 2012. The influence of irrigation and Effective Microorganisms on quantity and chemical composition of the yields of plants cultivation in organic crop rotation on light soil. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Engineering, 57(4): 148–154.

- Laznik, Ž, Tóth, T, Lakatos, T, Vidrih, M, Trdan, S. Inspection of Colorado potato beetle (L. decemlineata Say) on potato under field conditions: comparison of the effectiveness of the two strains Steinernema feltiae (Filipjev) and spraying with thiamethoxam. J Plant Dis Prot 2010, 117(3): 129-135.

- Lepiarczyk, A, Kulig, B, Stępnik, K. The effect of simplified soil cultivation and forecrops on LAI development of selected winter wheat varieties for crop rotation. Fragmenta Agronomica 2005, 2(86): 98-105.

- Xu, HL. Effects of a microbial inoculant and organic fertilizer on the growth, photosynthesis, and yield of sweet corn. Journal of Crop Production, 2000, 3: 183–214.

- Emitazi G, Nader A, Etemadifar Z. Effect of nitrogen fixing bacteria on growth of potato tubers. Adv. Food Sci. 2004, 26: 56–58.

- Kalitkiewicz A, Kępińska E. The use of Rhizobacteria to stimulate plant growth. Biotechnology, 2008, 2: 102–114.

- Górski R., Kleiber T., 2010. Effect of Effective Microorganisms (EM) on nutrient contents in substrate and development and yielding of rose (Rosa x hybrida) and gerbera (Gerbera jamesonii). Ecol. Chem. Eng., S, 17 (4): 505-513.

- Kaczmarek Z, Owczarzak W, Mrugalska L, Grzelak M. Effect of effective microorganisms on selected physical and water properties of arable-humus levels of mineral soils. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2007, 52: 73–77. (In Polish).

- Kaczmarek Z, Jakubas M, Grzelak M, Mrugalska L. Impact of the addition of various doses of Effective Microorganisms to arable-humus horizons of mineral soils on their physical and water properties. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2008a, 53: 118–121.

- Kaczmarek Z, Wolna-Murawska A, Jakubas M. Change in the number of selected groups of soil microorganisms and enzymatic activity in soil inoculated with effective microorganisms (EM). J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2008b, 53: 122–128.

- Szembowski, B. Experiences of a Farm in Trankwice with the EM-FarmingTM Biotechnology. Natural Probiotic Microorganisms, Publisher: Associate Ecosystem, Lichen, Poland, 2009: 56–58. (In Polish).

- Kosicka D, Wolna-Murawka A, Trzeciak M. Influence of microbiological preparations on soil and plant growth and development. Kosmos 2015, 64(2): 327-335. (in Polish).

- Kołodziejczyk M. Effectiveness of nitrogen fertilization and application of microbial preparations in potato cultivation. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2014a, 38: 299–310.

- Kołodziejczyk, M. Effect of nitrogen fertilization and microbial populations on potato yielding. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60(8): 379–386.

- Pszczółkowski P, Sawicka B. The impact of the application of biopreparations and fungicides on the yield and selected parameters of the seed value of seed potatoes. Acta Agroph. 2018a, 25(2): 239–255.

- Pszczółkowski P, Sawicka B. The impact of the use of fungicides, microbiological preparations, and herbal extracts on the shaping of the potato yield. Fragm. Agron, 2018b, 35 (1): 81-93.

- Pszczółkowski P, Krochmal-Marczak B, Sawicka B, Pszczółkowski M. Effect of the use of effective microorganisms on the color of raw potato tuber flesh for food processing. Appl Sci 2021, 11 (19): 8959. [CrossRef]

- Sawicka B, Pszczółkowski P, Kiełtyka-Dadasiewicz A, Ćwintal M, Krochmal-Marczak B. Effect of effective microorganisms on the quality of potatoes in food processing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11: 1415. [CrossRef]

- Koskey G, Mburu SW, Awino R, Njeru EM, Maingi JM. Potential Use of Beneficial Microorganisms for Soil Amelioration, Phytopathogen Biocontrol, and Sustainable Crop Production in Smallholder Agroecosystems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2021, 5: 130. [CrossRef]

- Galarreta JIR, Ezpelata B, Pascualena J, Ritter E. Combining ability in early generations of potato breeding. Plant Breeding, 2006, 125: 183–186.

- Kolasa-Wiącek, A. Will Effective Microorganisms Revolutionize the World? Post. Technol. Convert Food. 2010, 1: 66–69. (In Polish).

- Kowalska J, Sosnowska D, Remlein-Starosta D, Drożdżyński D, Wojciechowska R, Łopatka W. Effective microorganisms in organic farming. Publisher: IOR-PIB, Poznań, 2021. https://www.ior.poznan.pl/plik,3661,sprawozdanie-mikroorganizmy-w-rol-eko-2011-pdf.pdf.

- Barbaś, P., Skiba, D, Pszczółkowski, P, Sawicka B. Natural Resistance of Plants. Subbject: Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 2022. E Scholary Community Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/34721.

- Martyniuk S. Effective and ineffective microbiological preparations used in the protection and cultivation of plants as well as reliable and unreliable methods of their evaluation. Post. Microbiol., 2011, 50(4): 321-328.

- Okorski M, Majchrzak B. Fungi colonizing pea seeds after applying the EM 1 microbiological preparation. Progress in Plant Protection/Postępy w Ochronie Roślin, 2008, 48(4): 1314–1318.

- Higa T. Effective microorganisms, concept, and the latest technological achievements. Materials from the Effective Microorganisms Conference for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment. 4th Kyusei International Wildlife Agriculture Conference, Bellingham-Washington, 1998, USA: 247-248.

- Dach, J., Wolna-Maruwka B., Zbytek Z. Influence of effective microorganisms’ addition (EM) on composting process and gaseous emission intensity Journal of Research and Applications in Agricultural Engineering, 2009, 54(3), 49-55.

- Higa, T. Effective microorganisms – technology of the 21st century. Conference: “Effective Microorganisms in the World”. London, UK, 2005: 20-24.

- Zarzecka, K, Gugała, M. Effect of UGmax soil fertilizer on the potato yield and its structure. Bulletin IHAR, 2013, 267:107–112. (In Polish).

- Baranowska A, Zarzecka K, Gugała M, Mystkowska I. The effect of fertilizer on UGmax soil on the presence of Streptomyces scabies on edible potato tubers. J. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 3:68-73. [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet PCJ, Bloem J, de Goede RGM. Microbial diversity, nitrogen loss and grass production after the addition of Effective Microorganisms® (EM) to slurry manure. Applied Soil Ecology, 2006, 32: 188–198.

- Martyniuk S. Production of microbiological preparations on the example of symbiotic bacteria in legumes. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2010, 55: 20–23. (In Polish).

- Martyniuk S, Księżak J. Evaluation of pseudo-microbial biopreparations used in plant production. Polish Agronomic Journal, 2011, 6: 27-33.

- Paśmionka I, Kotarba K. Possibilities of using effective microorganisms in environmental protection. Cosmos, Problems of Biological Sciences, 2015, 64 (1): 173-184.

- Ding, L.-N.; Li, Y.-T.; Wu, Y.-Z.; Li, T.; Geng, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, W.; Tan, X.-L. Plant Disease Resistance-Related Signaling Pathways: Recent Progress and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumoto, S, Shintani, M, Higa, T. The use of effective microorganisms and biochar inhibits the transfer of radioactive caesium from soil to plants during continuous Komatsu cultivation. [In:] Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Radiobiology: Present”, Institute of Radiobiology of the NAS of Belarus, Gomel, Belarus, 26–27 September 2019, 22.

- Nigussie, A., Dume, B., Ahmed, M., Mamuye, M., Ambaw, G., Berhiun, G., Biresaw, A., Aticho, A. Effect of microbial inoculation on nutrient turnover and lignocellulose degradation during composting: A meta-analysis. Waste Management, 2021, 125: 220-234, ISSN 0956-053X. [CrossRef]

- Allahverdiyev SR, Kırdar E, Gunduz G, Kadimaliyev D, Revin V, Filonenko V, Rasulova DA, Abbasova ZI, Gani-Zade SI, Zeynalova EM. Effective Microorganisms (EM). Technology in Plants. Technology, 2011, 14:103–106.

- Pszczółkowski P, Sawicka B, Danilcenko H, Jariene E. The role of microbiological preparations in improving the quality of potato tubers. [In:] Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference: ‘New trends in food safety and quality’, Aleksandras Stulginskis University, Akademija, Lithuania, 5–7 October 2017: 22–23.

- Sawicka B, Egbuna C. Chapter 1. Pest of agricultural crops and control measures. PART I. Green approach to pest and disease control (in:) Natural Remedies for Pest, Disease and Weed Control. Edited by Chukwuebuka Egbuna, Barbara Sawicka, Elsevier, Academic Press, 17-28, 2020, ISBN: 978-0-12-819304-4. [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, B. Rate of spread of fungal diseases on potato plants as affected by application of a biostimulator and foliar fertilizer. Biostimulators in modern agriculture. Solanaceous crops. Ed. Z. Dąbrowski. Published by the Editorial House: Wieś Jutra, Limited. Warsaw. Plantpress, 2008, ISBN 83-89503-55-7: 68-76.

- Boligłowa E, Gleń K. Assessment of effective microorganism activity (EM) in winter wheat protection against fungal diseases. Ecol. Chem. Eng. A 2018, 15:23–27.

- Gacka S. Economic aspects of implementing EM-FarmingTM biotechnology. Natural probiotic microorganisms. Publisher: Ecosystems Association, Licheń, 2009, 28–33. (In Polish).

- Tommonaro G, Abbamondi GR, Mikołaja B, Poli A, D’Angelo C, Iodice C, De Prisco R. Productivity and Nutritional Trait Improvements with Various Tomatoes Grown Effective Microorganisms Technology. Agriculture 2021, 11, 2, (112). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz M, Céspedes C. Bokashi as a fix and nitrogen source for sustainable farming systems: an overview. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2019, 237–248. [CrossRef]

- Marczakiewicz J. Another year with EM biotechnology at RZD SGGW Chylice. Natural probiotic microorganisms. Ecosystem Association Publishing House, Licheń, 2009, 65. (in Polish).

- Mathews, S. , Gowrilekshmi R. Solid Waste Management with Effective Microbial (EM) Technology. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci, 2016, 5(7): 804-815. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y., Lu H., Zhang J., Shuguang C., Yangqing C., Lei WY, Zhang R., Song L. Simultaneous heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification (SND) for nitrogen removal: review and future prospects, Environmental Advances, 2022, 9, 100254. [CrossRef]

- Al-Taweil HI, Bin Osman M, Hamid AA, Yusoff WM. Development of microbial inoculants and the impact of soil application on rice seedlings growth. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2009, 4: 79–82.

- Szewczuk Cz, Sugier D, Baran S, Bielińska E.J, Gruszczyk M. The impact of fertilizing agents and different doses of fertilizers on selected soil chemical properties as well as the yield and quality traits of potato tubers). Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, Sectio E, Agricultura, 2016, LXXI (2): 65–79.

- Development of ecological hop production technology. [in:] 1st Lublin Scientific and Technical Conference – Microorganisms in Environmental Revitalization - Science and Practice.

- Henry AB, Maung CEH, Kim KY. Metagenomic analysis reveals enhanced biodiversity and composting efficiency of lignocellulosic waste by thermoacidophile effective microorganism (tEM), Journal of Environmental Management, 2020, 276: 111252, ISSN 0301-4797. [CrossRef]

- Ney L, Franklin D, Mahmud K, Cabrera M, Hancock D, Habteselassie M, Newcomer Q, Dahal S. Impact of inoculation with local effective microorganisms on soil nitrogen cycling and legume productivity using composted broiler litter, Applied Soil Ecology, 2020, 154: 103567. [CrossRef]

- Faturrahman L, Meryandini A, Junior M.Z, Rusmana I. The Role of Agarolytic Bacteria in Enhancing Physiological Function for Digestive System of Abalone (Haliotis asinine). J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2015, 5(5): 49–56.

- Gacka S, Kolbusz S. Biotechnology EM-FarmingTM – comprehensive, natural, solution in animal production ensuring animal welfare. Natural probiotic microorganisms. Publisher: Ekosystem Association, Licheń, 2009: 102–103. (In Polish).

- Tsatsakis, A.M., Nawaz, M.A., Kouretas D., Balias, G., Savolainen, K., Tutelyan, V.A., Golokhvast, K.S., Lee, J.D., Chung, J.G. 2017. Envirtmental impacts of Genetically Modified Plants: A Review, Environmental Research, 156, 2017, 818-833, ISSN 0013-9351. [CrossRef]

- Pniewska I. Wpływ Efektywnych Mikroorganizmów (EM) i dokarmiania pozakorzeniowego nawozami typu Alkalin na plonowanie i cechy jakościowe fasoli szparagowej. Rozprawa Doktorska, UPH, Siedlce, 2015, 94 ss. UPH241d48bcde014585936d1137b4d854ac [in {Polish).

- Fatunbi O, Ncube L. Activities of Effective Microorganism (EM) on the Nutrient Dynamics of Different Organic Materials Applied to Soil. Am. Eurasian J. Agron. 2009, 2(1): 26–35.

- Safwat M., Safwat, Rozaik, E. Growth Inhibition of Various Pathogenic Microorganisms Using Effective Microorganisms (EM). International Journal of Research and Engineering, 2017, 4 (12), 283-286. [CrossRef]

- Gopalasamy, R. The role of microorganisms in sustainable development Envtl. International Journal of Scientific Research 2019, 6 (7): 413.

- Song T, Zhang X, Li J, Wu X, Feng H, Dong W. A review of research progress of heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification microorganisms (HNADMs), Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 80: 149319. [CrossRef]

- Correia, T.S.; Lara, T.S.; Santos, J.A.d.; Sousa, L.D.S.; Santana, M.D.F. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Promote Physiological and Biochemical Advantages in Handroanthus serratifolius Seedlings. Plants 2022, 11, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin FM, van der Heijden MAG. The mycorrhizal symbiosis: research frontiers in genomics, ecology, and agricultural application. New Phytologist, 2024, 242(4): 1486-1506. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.E. Dang, Y., Smith J.A. Nitrogen cycling during wastewater treatment. Adv. Appl. Microbiol., 2019,106: 113-192.

- Xi, H., Zhou, X., Arslan, M., Luo, Z., Wei, J., Wu, Z., El-Din M.G. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification process: Promising but a long way to go in the wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ., 2022, 805, Article 150212.

- Lei, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, H., Xi, C., Song L. A novel heterotrophic nitrifying and aerobic denitrifying bacterium, Jobelihle taiwanensis DN-7, can remove high-strength ammonium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2016, 100 (9), 4219-4229.

- Su, JF., Shi, JX., Huang, T.L., Ma F. Kinetic analysis of simultaneous denitrification and biomineralization of novel Acinetobacter sp. CN86. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 109 (1) (2016), pp. 87-94.

- , Shi, J.X., Ma F. Aerobic denitrification and biomineralization by a novel heterotrophic bacterium, Acinetobacter sp. H36. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 2017, 116 (1–2), 209-215.

- Jetten, M.S. The microbial nitrogen cycle. Environ. Microbiol., 2008, 10(11), 2903-2909.

- Liu, S., Chen, Q., Ma, T., Wang, M., Ni J. Genomic insights into metabolic potentials of two simultaneous aerobic denitrification and phosphorus removal bacteria, Achromobacter sp. GAD3 and Agrobacterium sp. LAD9 FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 2018, 94 (4), 223.

- Chen, J. , Zhao, B., An, Q., Wang, X., Zhang Y.X. Kinetic characteristics and modelling of growth and substrate removal by Alcaligenes faecalis strain NR. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng., 2016, 39 (4), 593-601.

- Xia, L., Li, X., Fan, W., Wang J. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by a novel Acinetobacter sp. ND7 isolated from municipal activated sludg Bioresour. Technol., 301 (2020), Article 122749.

- Msambwa MM, Daniel K, Lianyu C, Integration of information and communication technology in secondary education for better learning: A systematic literature review. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2024, 10: 101203, ISSN 2590-2911. [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S.K., Maiti NK. Molecular insight into the dynamic central metabolic pathways of Achromobacter xylosoxidans CF-S36 during heterotrophic nitrogen removal processes J. Biosci. Bioeng., 2017, 123 (1), 46-55.

- Medhi, K. Singhal, A., Chauhan, D.K. Thakur I.S. Investigating the nitrification and denitrification kinetics under aerobic and anaerobic conditions by Paracoccus denitrificans ISTOD1, Bioresour. Technol., 242 (2017), 334-343.

- Huang, F., Pan, L., Lv, N., Tang, X. Characterization of novel Bacillus strain N31 from mariculture water capable of halophilic heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification J. Biosci. Bioeng., 124 (5) (2017), pp. 564-571.

- He, T., Xie, D., Li, Z., Ni, J., Sun Q. Ammonium stimulates nitrate reduction during simultaneous nitrification and denitrification process by Arthrobacter arilaitensis Y-10. Bioresour. Technol., 2017, 239, 66-73.

- Zhao, B., He, Y.L., Hughes, J., Zhang X.F. Heterotrophic nitrogen removal by a newly isolated Acinetobacter calcoaceticus HNR. Bioresources Technol., 2010, 101 (14), 5194-5200.

- Yang, L., Ren, Y.X., Liang, X., Zhao, SQ., Wang, JP., Xia, Z.H. Nitrogen removal characteristics of a heterotrophic nitrifier Acinetobacter junii YB and its potential application for the treatment of high-strength nitrogenous wastewater. Bioresour. Technol., 2015, 193, 227-233.

- Wang, H., Zhang, W., Ye, Y., He, Q., Zhang S. Isolation and characterization of Pseudoxanthomonas sp. Strain YP1 capable of denitrifying phosphorus removal (DPR) Geomicrobiology J. 2018, 35 (6), 537-543.

- 1Zhang D, Huang, X., Li, W., Qin, W., Wang P. Characteristics of heterotrophic nitrifying bacterium strain SFA13 isolated from the Songhua River. Ann Microbiol, 2015, 66 (1), 271-278.

- Xu, X.; Yang, K.; Dou, Y. High-end equipment development task decomposition and scheme selection method. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2021, 32, 118–135. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx, M.; Reins, L. The Future of Farming: The (Non)-Sense of Big Data Predictive Tools for Sustainable EU Agriculture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, K.; Dou, Y. High-end equipment development task decomposition and scheme selection method. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2021, 32, 118–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer J, Riemens M, Reinders M. The future of crop protection in Europe. Panel for the Future of Science and Technology. European Parliamentary Research Service Scientific Foresight Unit (STOA) PE 656.330 – February 2021 EN. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/656330/EPRS_STU(2021)656330_EN.pdf.

- Mann, R. S, Kaufman, P.E. Natural product pesticides: their development, delivery and use against insect vectors. Mini-Rev. Org Chem 2012, 9:185–202.

| Microbe/ References | Weed target(s) & Status | Trade name | Year of Introduction or registration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria cassia Bannon,1988 | Cassia obtusifolia C. coccidentalis Crotalaria spectabilis Never commercialized | Casst™ | never |

| Alternaria destruens Bewick et al., 2000 | Cusucta spp. Discontinued | Smolder™ | 2005 |

| Chondrostereum purpureum Hintz, 2007 | Populus and Alnus spp. Unknown | Chontrol™ | 2004 |

| Colletotrichum acutatum Morris, 1989 | Hakea sericea Discontinued | Hakatak | 1990 |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene Cartwright et al., 2010 | Aeshynomene vigrinica Available on demand | Collego® | 1982 |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. Malvae Boyetchko et al. 2007 | Acacia mearnsii and A. pycnantha Discontinued | Stumpout™ | 1997 |

| Cylindrobasidium laeve. Morris et al. 1999 | Acacia mearnsii and A. pycnantha Discontinued | Stumpout™ | 1997 |

| Phoma macrostoma Bailey et al. 2011 | many broadleaf weed species Available | Bio-Phoma™ | 2016 |

| Phytophthora palmivora Ridings 1986 | Morrenia odorata Discontinued | DeVine® | 1982 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens Kennedy et al. 2001 | Bromus tectorum Discontinued | D7® | 2014 |

| Puccinia canaliculata Phatak et al. 1983 | Cyperus esculentus Discontinued | Dr. Biosedge™ | 1987 |

| Puccinia thlaspeos Knopp et al. 2002 | Isatis tinctorial Discontinued | Woad Warrior® | 2002 |

| Sclerotinia minor Watson2018 | Taraxacum officinale Discontinued | Sarritor® | 2009 |

| Several fungi Gale & Goutler, 2013 | Parkinsonia aculeate Available | Di-Bak® | 2019 |

| Streptomyces scabies O’Sullivan et al. 2015 | several grass and broadleaf weeds Never commercialized | Opportune™ | 2012 |

| Tobacco mild green mosaic vírus Charudattan & Hiebert, 2007 | Solanum viarum Available | SolviNix™ | 2014 |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. poae Imaizaumi et al. 1999 | Poa annua Discontinued | Camperico™ | 1997 |

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Increasing food production: Some microorganisms are beneficial to plants and help in their growth and production. They can also help produce food by fermenting and processing food. | Uncontrolled growth of microorganisms: In some cases, microorganisms can grow uncontrollably and become harmful to plants, soil and human health. |

| Plant protection: Some microorganisms are able to fight plant diseases and pests, reducing the use of harmful pesticides and other chemicals. | Environmental pollution: Some microorganisms, such as E. coli bacteria, can cause soil and water pollution, which is a public health risk |

| Improving soil quality: Microorganisms can help enrich the soil with nutrients and improve its structure, which positively affects the health of plants. | GMO risks: Some microbial technologies, such as genetic engineering, can lead to genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which raise social and ethical concerns. |

| Sustainable Agriculture: The use of microorganisms can aid sustainable agriculture by reducing the use of harmful chemicals and improving soil quality. | Costs: Some systems and technologies using microorganisms can be expensive, which is a barrier to their widespread use |

| Origin of species | Specification of Species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Activated sludge |

Acinetobacter sp. ND7 Ochrobactrum anthropic LJ81 Alcaligenes faecalis NR Achromobacter sp. GAD3 Agrobacterium sp. LAD9 Acinetobacter sp. SZ28 Acinetobacter sp. WB-1 Ochrobactrum sp. KSS10 Pseudomonas stutzeri CFY1 Thauera sp. FDN-01 Diaphorobacter sp. PD-7 |

[[152] [146] [151] [150] [150] [126] [126] [28] [151] [[153] [126] |

| Artificial lake |

Acinetobacter sp. H36 Acinetobacter sp. CN86 |

[[147] [147] |

| Domestic wastewater |

Achromobacter xylosoxidans CF-S36 Paracoccus denitrificans ISTOD1 Klebsiella pneumoniae CF-S9 |

[154] [[155] [154] |

| Drinking water reservoir | Zoogloea sp. N299 | [156] |

| Flooded paddy soil |

Arthrobacter arilaitensis Y-10 Pseudomonas tolaasii strain Y-11 |

[157] [157] |

| Laboratory-scale MBR |

Acinetobacter calcoaceticus HNR Bacillus methylotrophicus L7 Serratia sp. LJ-1 |

[158] [[126] [128] |

| Laboratory-scale SBR |

Acinetobacter junii YB Pseudoxanthomonas sp. YP1 |

[[159] [160] |

| Landfill leachate | Zobellella taiwanensis DN- | [146] |

| Seabed sludge | Paracoccus versutus LYM | [161] |

| Songhua River | Microbacterium esteraromaticum SFA13 | [162] |

| Wastewater system |

Acinetobacter sp. YS2 Cupriavidus sp. S1 Pseudomonas sp. yy7 Rhodococcus sp. CPZ24 |

[[143] [160] [151] [151] |

| Source | Target Weeds | Ecosystem | Registered Name |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria cassiae | Cassia obtusifolia L. | Soy | Recipe development - “CASST” | [54] |

| Alternaria destruens | Cuscuta spp. | Cranberry Field | assessment - Smolder | [11] |

| C. purpura | P. Serotina | Forest | Commercoalizedm Biochon TM | [61] |

| C. purpura | Populus euramericana | Guinier Forest | Commercialized - Chontrol® | [57] |

| Cephalospprium diospyri | Diospyras virginiana L. | Pastures, pastures | Oklahoma | [53] |

| Chondrostereum purpureum (Fr.) | Pouz Prunus serotina Ehrh. | Forest, Mountains | Commercialized - Mycotech™ | [54] |

| Citrus lime (L.) Osbeck | D. Sanguinalis | Cultivated areas | Commercial herbicide Avenger® | [51] |

| Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Solanum nigrum L. | Crop land, roadside | Commercialized - Green Match™ | [62] |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Hakea sericea Schrad. &J.C. Wendl. | Mountain meadows | Commercialized - Hakak |

[55] |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Malvae, Malva Pusilla Sm. | Flex, lentils, horticultural crops | Commercialized - BioMal ® [56] |

[56] |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioidesaeschynomene | Aeschynomene virginica L. | Rice, Soybeans | Commercialized– Colle™ | [54] |

| Cylindrobasidium | leave Acacia spp. | Forest, pasture | Commercialized - Stump-Out™ | [61] |

|

Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) |

Stapf. spp. | Agricultural land | Commercialized - Green Match™ EX | [64] |

| Phoma macrostoma | Reynoutria japonica Houtt. | Golf Courses, Agriculture &Agroforestry | Commercialized - Phoma | [59] |

| Phytophthora palmivora | Morrenia odorata (Hook. &Arn.) Lindl. | Citrus Groves | Commmercialized — Devine™ | [54] |

| Puccinia thlaspeos C. Shub. | Isatis tinctoria L. | Forest, pastures | - Beloukha ® [62] | [63] |

| S. aromaticum | E. crus-galli | Farmland, Rice | Commercialized - Weed Slayer® | [59] |

| Sclerotinia minor Jagger. | Taraxacum sp. | Turf | Commercialized - Sarritor ® [60] | [61] |

| Streptomyces acidi scabies | Taraxacum officinale L. | Turf | Commercialized - Opportune ® |

[59] |

|

Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & LM Perry & Presl Cinnamomum verum J., |

E. crus-galli | Rice, farmland | Commercialized - WeedZap ® | [53] |

| Xanthomonas campestris | Poa annua L. | Turf, athletic fields | Commercialized - Camperico | [55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).