1. Introduction

Globally, the incidence of liver diseases is on the rise, with an increasing risk of illness. Despite strengthened public health interventions worldwide, liver diseases continue to account for a significant proportion of the global disease burden, highlighting the complexity and multidimensionality of the epidemiology of liver diseases. Liver injuries are the pathological basis of liver disease. Most liver injuries are accompanied by an inflammatory response. Although the inflammatory response is a protective mechanism of the body, persistent liver inflammation can exacerbate liver tissue damage and promote the development of fibrosis [

1]. Therefore, further in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying liver inflammation and the identification of key molecules as potential drug targets are of great clinical significance for developing effective therapies for chronic liver diseases.

CDK5RAP3 (CDK5 regulatory subunit associated protein 3, C53), is alternatively named LZAP (LXXLL/Leucine-Zipper-Containing ARF-Binding Protein), IC53 (an isoform of C53), HSF-27 (Heat Stress Transcription Factor 27), MST016, PP1553, OK/SW-cl.114 (NCBI). It was initially identified as a CDK5-binding protein twenty years ago [

2]. CDK5RAP3 is highly conserved in mammals and expressed in multiple organs [

3]. It participates in diverse cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, cell damage, apoptosis, invasion, migration, metastasis, cytoskeletal remodeling, and proliferation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. During early stages of embryonic development, CDK5RAP3 can regulate the progression of the cell cycle ,adhesion, and migration of epidermal cells [

12]. Studies have shown that CDK5RAP3 plays an important role in diseases such as gastric cancer, colon cancer, and gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma. However, its function in the liver remains unclear. Mak et al. found that CDK5RAP3 is highly expressed in liver cancer tissues, and in vitro function experiments revealed it promotes invasion and migration of liver cancer cells by downregulating the expression of the tumor suppressor gene p14 and activating the p21 protease [

13]. Conversely, other studies reported relatively low CDK5RAP3 expression in liver cancer tissues and liver cancer cell lines (HCC), with expression levels significantly correlated with prognosis-the long-term survival rate of patients with high expression was significantly better than those with low expression [

14]. Yang's team used a mouse knockout model and found that CDK5RAP3 knockout mice died at embryonic day16.5 (E16.5), indicating that CDK5RAP3 is essentioal for liver development and function, as well as serving as a substrate adapter of the UFM1 (Ubiquitin Fold Modifier 1) system [

12,

15]

.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a critical pattern recognition receptor (PRRs) primarly expressed in the cytoplasm and belongs to the NLRPs protein family. It is widely expressed in the cytoplasm of immune and non-immune cells, and is currently the most extensively studied inflammasome [

16].The NLRP3 inflammasome acts as a sensor, responding to microbial infections, endogenous danger signals, and environmental stimuli. These stimuli disrupt intracellular homeostasis, triggering the production and secretion of NLRP3 signal transduction mediators (such as cytokines), induce inflammatory cell death, and when excessively activated, promoting the progression of various inflammatory diseases[

17]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome occurs in two stages, the priming stage (the first signal) and the activation stage (the second signal). The priming stage upregulates the expression of inflammasome components NLRP3, Caspase-1, and precursor IL-1β. Following activation, NLRP3 molecules oligomerization via homotypic interaction through the NACHT domain [

17]

.NLRP3 oligomers recruit ASC through PYD-PYD interactions, promoting ASC speckles formation. Subsequently, precursor Caspase-1 is recruited via the C-terminal Caspase Recruitment Domain (CARD) of ASC, and self-cleavage occurs between the p20 and p10 subunits activating Caspase-1 [

18,

19]. Activated Caspase-1 precursor IL-1β and IL-18 turn into their mature forms. Additionally, activated Caspase-1 cleaves and activates gasdermin D (GSDMD), causing it to translocate to the plasma membrane where it forms pores, facilitating the release of mature IL-1β and IL-18 into the extracellular space. The massive release of inflammatory factors, culminates in programmed inflammatory, form of cell death called pyroptosis [

20,

21,

22]

.

In this study, liver-specific CDK5RAP3 knockout mice and mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEFs) cell line with conditional knockdown of CDK5RAP3 were used for biological research. Deletion of CDK5RAP3 in liver resulted in liver damage, activation of the NLRP3 pathway and induction of inflammation, accompanied by Caspase-1-mediated inflammatory cell death. Meanwhile, MEFs with conditional CDK5RAP3 knockdown exhibited reduced growth rates, decreased viability, and increased apoptotic. The levels of proinflammatory factors and certain genes related to the NLRP3 pathway were elevated in these MEFs, consistent with the results in CDK5RAP3 knockout mice liver.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were derived from CDK5RAP3f/f: CAG-CreERT2 embryos at embryonic day 13–14 (E13–E14). Genotypic verification confirmed homozygous floxed alleles (CDK5RAP3f/f) with either CreERT2/ERT2 or CreERT2+/- expression. Dissected trunk tissues were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), mechanically minced, and subjected to enzymatic digestion using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco,NY, USA) at 37°C for 5 minutes. Cell suspensions were filtered through 70 μm strainers, and adherent fibroblasts were selected by differential attachment in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; HyClone, Utah, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS,Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing,China). At 80–90% confluence, cells were transduced with lentiviral particles carrying the T antigen (MOI = 5). Puromycin selection (10 μg/ml; InvioGen, ant-pr-1, USA) was initiated 48 hours post-transduction to enrich stably transduced cells. For conditional CDK5RAP3 knockout, MEFs were treated with 4-OHT (4-Hydroxytamoxifen, 8 μM, H7904 or H6278, Sigma, USA) for 72 hours, with vehicle control (0.1% ethanol) included for normalization. All cultures were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.2. Animal Model

Liver-specific CDK5RAP3 knockout (CKO) mice which is generated by Prof. Yafei Cai's laboratory and 5-month-old wild-type littermates were maintained under controlled environmental conditions in temperature of 18–22°C and humidity of 50–60% in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility. Animals were provided with standard laboratory chow (Research Diets, Inc.) and autoclaved water ad libitum. All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in full compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.3. Tissue Pathology Analysis

Liver tissues from wild-type and CDK5RAP3-knockout mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF; Sigma-Aldrich, HT501128) for 72 hours at 4°C, followed by paraffin embedding. Serial sections of 5 μm thickness were dewaxed through three 20 minutes xylene immersion, and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series: 100% ethanol (2 × 2 min), 95%, 90%, 80%, and 70% ethanol (2 min each). Sections were rinsed in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, pH 7.4; Gibco, 14190144) with three 5-minutes washes to remove residual ethanol.

Nuclear staining was performed by immersion in Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, MHS16) for 90 seconds at 25°C. After rinsing in tap water to stop the reaction, sections were differentiated in 0.1% HCl-ethanol (v/v) for 30 seconds and washed in DPBS (2 × 5 min). Cytoplasmic counterstaining was achieved with eosin Y (0.5% aqueous solution; Solarbio, G1120) for 120 seconds. Stained sections were dehydrated through an ascending ethanol series (70% → 80% → 90% → 100%; 2 min each), cleared in 3 changes of xylene, 5 min each, and mounted with neutral balsam (Sigma-Aldrich, 03989). Slides were air-dried in a chemical fume hood for 24 hours prior to bright-field microscopy analysis (Nikon Eclipse Ni-U).

2.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

Following collection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformalde-hyde (PFA) for 15 minutes. Permeabilization was performed using PBST (PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100) for 10 minutes, followed by incubation in blocking buffer (PBST supplemented with 10% normal goat serum) at room temperature for 30-45 minutes. Primary antibodies (details in

Table S1) targeting Alb, CDK5RAP3, IL-6, Nlrp3were applied at 37°C for 45-60 minutes. After washing with PBS containing 1% BSA, cells were incubated at 37°C with species-specific secondary antibodies (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) andGoat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647); (details in

Table S1). Unbound secondary antibodies were removed via three 5 minutes PBS washes, and nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 for 5 minutes. Fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 900 META confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 900 META, Jena, Germany).

Table S1.

Antibodies used in this paper.

Table S1.

Antibodies used in this paper.

| Primary antibodies |

Vendor |

Dilution |

Source |

| IL6( IF/WB) |

Abcam (ab9324) |

1:200/1:2000 |

Mouse |

| IL1β(WB) |

ABclonal (A23416) |

1:2000 |

Rabbit |

| GSDMD(WB) |

ABclonal (A17308) |

1:1000 |

Rabbit |

| Caspase1(WB) |

Proteintech (22915-1-AP) |

1:2000 |

Rabbit |

| BAX(WB) |

Proteintech (50599-2-Ig) |

1:2000 |

Rabbit |

| TNF-alpha(WB) |

Proteintech (17590-1-AP) |

1:1000 |

Rabbit |

| CDK5RAP3(WB) |

Abcam (ab157203) |

1:2000 |

Rabbit |

| Bcl-2(WB) |

ABclonal (A0208) |

1:1000 |

Rabbit |

| NLRP3( IF/WB) |

Proteintech (19771-1-AP) |

1:200/1:1000 |

Rabbit |

| Alb (IF) |

Proteintech (16475-1-AP) |

1:200 |

Mouse |

| CDK5RAP3(IF) |

Abcam(ab168353) |

1:200 |

Rabbit |

Secondary antibodies

Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488)(IF)

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647)(IF)

HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H+L)(WB)

HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG(H+L)(WB)

|

Abcam (ab150077)

Abcam(ab150115)

Proteintech(AB_2722564)

Proteintech(AB_2722565)

|

1:150

1:150

1:5000

1:5000

|

Goat

Goat

Goat

Goat

|

2.5. Protein Extraction from Liver Tissues and Cells

When the cells reached approximately 80% confluence, the cell culture dishes were rinsed twice with preheated PBS (pH 7.4). Cells were lysed on ice for 30 minutes using RIPA biffer (Beyotime ,ST506, China) supplemented with 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Beyotime, st506, China). Lysates were centrifuged at 8,000g for 4 minutes at 4°C to peiiet cellular debris. The supernatant transfer to fresh pre-chilled tubes and protein concentration was quantified using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, China). Sample were mixed with 5*SDS (Beyotime, P0285, China) and boil mixture for 5 minutes at 100℃ to denaturation proteins. Aliquots of processed protein samples were stored at -20°C for short-term preservation.

2.6. RNA Extraction from Liver Tissue and Cells

Total RNA was isolated from cells at 80% confluence using TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Briefly, cells were washed twice with RNase-free PBS and harvested by centrifugation at 1,000 ×g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cell pellets were lysed in 1 mL TRIzol™ with vigorous pipetting on ice for 5 minutes. Chloroform was added, followed by vortexing for 15 seconds and incubation at 25°C for 3 minutes. After centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 15 minutes at 4°C, the aqueous phase was transferred to fresh RNase-free tubes. RNA was precipitated by adding 0.5 mL isopropanol and incubating at -20°C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was washed with 1 mL 75% ethanol (prepared in DEPC-treated water), centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 5 minutes, and air-dried for 5-10 minutes. Purified RNA was dissolved in 30-50 μL RNase-free water, heated at 55°C for 10 minutes, and quantified using a NanoDrop™ One spectrophotometer (Shanghai Jiapeng Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), with RNA integrity confirmed by A260/A280 ratios of 1.8-2.1.

2.7. RT-qPCR

According to the manufacturer's instructions, RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription system. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on the instrument using appropriate primers. The primer sequences of target genes and GAPDH gene were designed using PrimerPremier5.0 software.

Table S2.

Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR.

Table S2.

Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR.

| Genes |

Genbanks |

Forward primer sequences |

Reverse primer sequences |

Product Length (bp) |

| NLRP3 |

NM_001359676.1 |

GACCAGCCAGAGTGGAATGA |

CTTCAAGGCTGTCCTCCTGG |

92 |

| TNFα |

NM_013693.3 |

CCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT |

GCTACGACGTGGGCTACAG |

61 |

| IL1β |

NM_008361.4 |

GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG |

TGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACAG |

118 |

| IL6 |

NM_031168.2 |

AGACAAAGCCAGAGTCCTTCAG |

GTGACTCCAGCGTATCTCTTGGT |

148 |

| Bax |

NM_007527.3 |

ATGCGTCCACCAAGAAGCTGAG |

CCCCAGTTGAAGTTGCCATCAG |

102 |

| Bcl2 |

NM_009741.5 |

GCAGAGATGTCCAGTCAG |

CACCGAACTCAAAGAAGG |

94 |

| CDK5RAP3 |

NM_001308183.1 |

ATGAGATCGACTGGGGTGAC |

AGCCTCAGTTCCTGTCTCCA |

156 |

| β-Actin |

NM_007393.5 |

TGCTGTCCCTGTATGCCTCTG |

GGTGTAAAACGCAGCTCAGTAA |

245 |

| ASC |

NM_023258.3 |

CTGCTCAGAGTACAGCCAGAAC |

CTGTCCTTCAGTCAGCACACTG |

181 |

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

After electrophoresis of the protein solution, proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder in TBST for 1hour before incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The antibodies used in this study included: GAPDH, CDK5RAP3, bax, bcl2, TNFα, cleaved-IL-1β, IL-1β, IL-6, NLRP3, ASC, caspase1, cleaved-caspase1, and GSDMD. Finally, the membranes were processed using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.9. Other Related Operations

Crystal violet (Macklin 548-62-9, Shanghai, China) was used for crystal violet staining. The Annexin V-FITC/PI cell apoptosis detection kit (Vazyme, A211, China) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance was performed, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. A p-value > 0.05 indicates no significant difference; a p-value < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference; a p-value < 0.01 indicates a highly significant difference; and a p-value < 0.001 indicates an extremely significant difference. The data are presented as mean ± standard error (SD).

3. Results

3.1. CDK5RAP3 Deletion Induced Liver Injury in Mice

CDK5RAP3

F/F mice were crossed with Alb-Cre mice to generate hepatocyte-specific CDK5RAP3 knockout (KO) mice (

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep). Western blotting and quantitative PCR (q-PCR) analysis showed that the expression levels of CDK5RAP3 protein and mRNA in the liver of

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep mice were significantly lower than those of wild type (WT) mice (

Figure 1A). Immunofluorescence (IF) staining showed that the colocalization signal of albumin (Alb) and CDK5RAP3 in the liver cells of

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep mice was weakened (

Figure 1B) . Hematoxylin eosin (H&E) staining further demonstrated significant lipid accumulation, vacuolation, and inflammatory cell infiltration in the livers of the

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group (

Figure 1C). Furthermore, in the

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group, the protein levels of the pro - apoptotic factor BAX and the anti - apoptotic factor BCL2 exhibited an upward tendency, whereas the mRNA expression levels of both were significantly elevated (

Figure 1D). These results indicated that the absence of CDK5RAP3 leads to liver dysfunction and hepatocyte injury.

3.2. CDK5RAP3 Deletion Up-Regulates Liver Proinflammatory Factor Expression

After significant inflammatory expression was observed in H&E staining of liver tissue, liver pro-inflammatory factors were systematically quantified to validate the inflammatory phenotype. Western blot analysis showed that the protein levels of IL - 6 and cleaved IL-1β (CL-IL1β) in the

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group were significantly higher than those in the WT group (

Figure 2A). q PCR further confirmed that the mRNA expression levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β in the

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group were upregulated (

Figure 2B). These data were consistent with histopathological evidence of inflammation, confirming a direct association between CDK5RAP3 deletion and cytokine dysregulation.

3.3. CDK5RAP3 Deletion Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Induces Pyroptosis

To investigate the regulatory function of CDK5RAP3 in the inflammatory signaling pathway, the expression levels and activities of key molecules within the NLRP3 inflammasome were systematically analyzed. Western blot analysis showed that the protein expressions of NLRP3 and ASC (apoptosis-related speckle like protein containing CARD domain) in the liver of

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group were significantly increased (

Figure 3A). Immunofluorescence staining revealed enhanced IL-6 and NLRP3 signals in

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group (

Figure 3B). qPCR confirmed that the mRNA expression of NLRP3, ASC and Caspase-1 in the

CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep group was upregulated compared to WT mice, while the mRNA levels of the pyroptosis marker GSDMD were also significantly increased (

Figure 3C). These data suggest that deletion of CDK5RAP3 triggers pyroptosis in Caspase-1 dependent cells by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway.

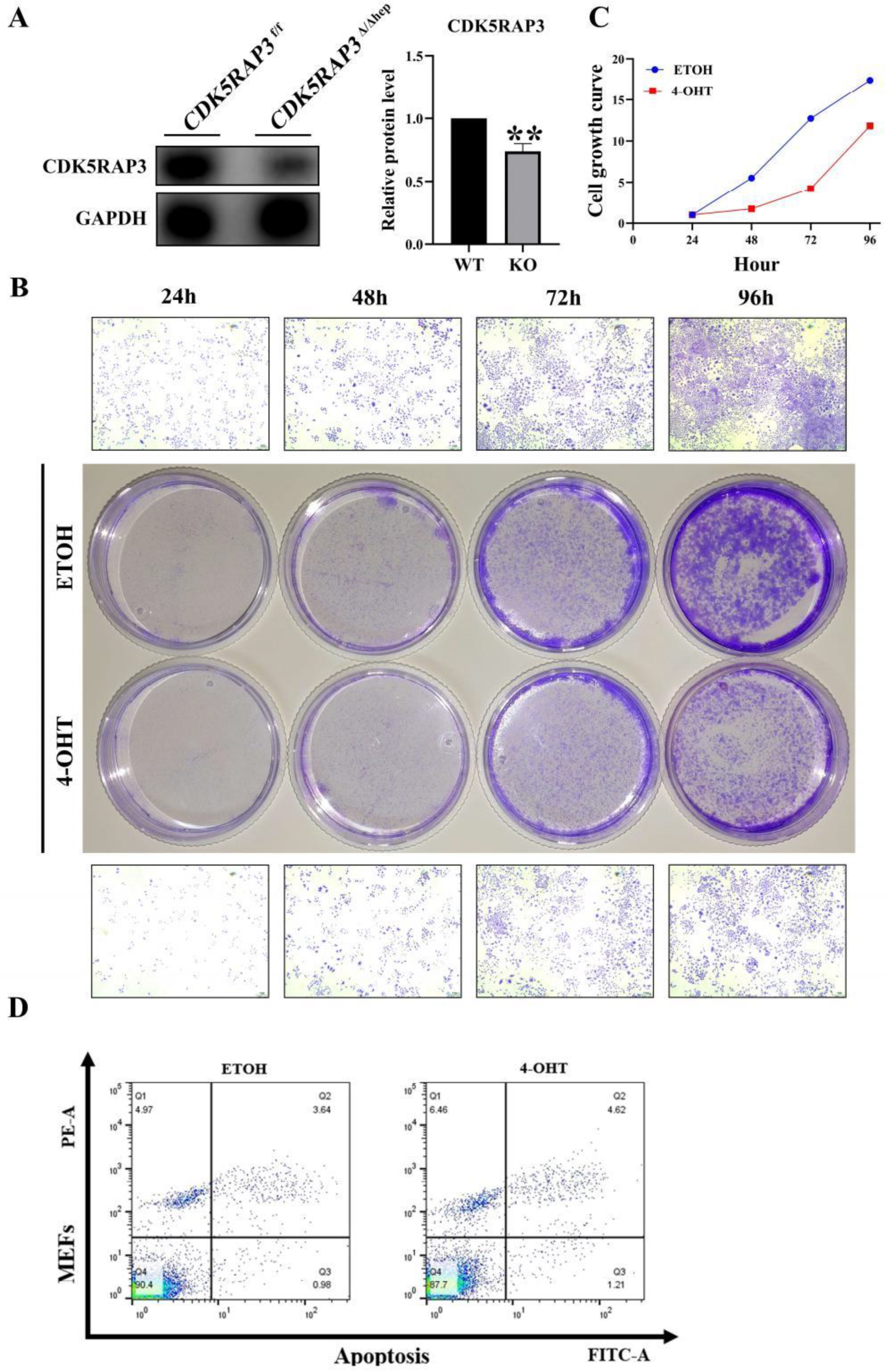

3.4. Loss of CDK5RAP3 Promotes Apoptosis and Inflammatory

To elucidate the regulatory mechanism of CDK5RAP3 deficiency in apoptotic pathways, a tamoxifen-inducible conditional knockout model was established in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) using 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, 8 μM) system. Treatment with 4-OHT for 48 hours resulted in a decrease in the expression level of CDK5RAP3 protein in MEFs (

Figure 4A). Crystal violet staining (24 - 96 h treatment) showed that the cell proliferation rate in the 4-OHT treatment group was significantly slower than that in the EtOH control group (

Figure 4B, 4C). Flow cytometry analysis (Annexin V/PI double staining) showed that CDK5RAP3 knockdown resulted in an increased apoptosis rate (

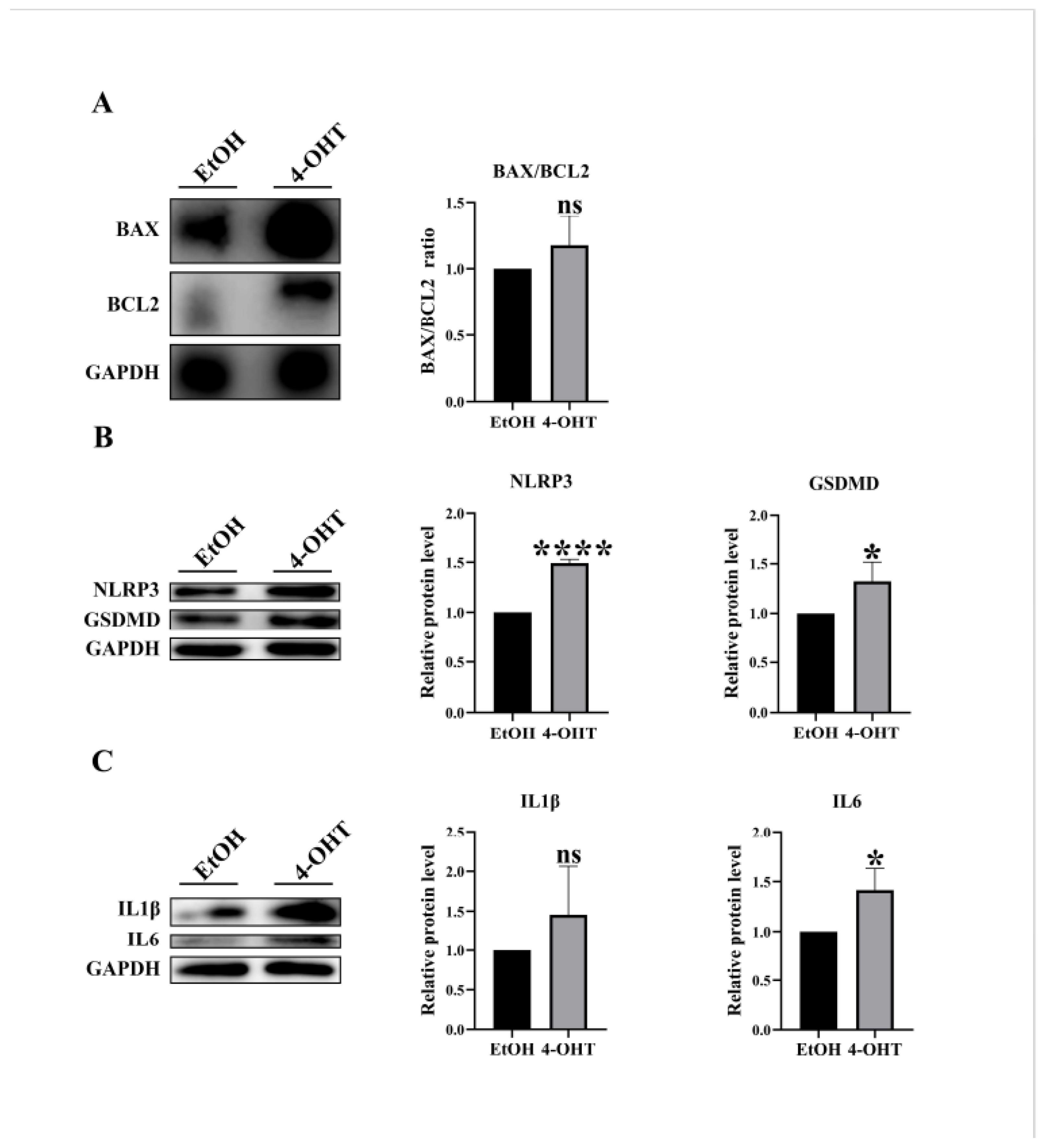

Figure 4D), and the BAX/BCL2 ratio was increased (

Figure 5A). Consistent with the results of liver tissue experiments, 4-OHT administration induced significant activation of pyroptosis-related signaling mediators, as evidenced by elevated protein levels of the NLRP3 inflammasome and its downstream effector GSDMD (

Figure 5B), while the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β expression were upregulated (

Figure 5C) These results suggest that the loss of CDK5RAP3 exacerbates liver injury through synergistic activation of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways.

4. Discussion

This study elucidates the molecular mechanisms by which CDK5RAP3 deficiency leads to multidimensional pathological damage in mouse livers. Initial histological analysis via H&E staining revealed pronounced phenotypic abnormalities in CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep mice, including hepatocyte swelling, vacuolization, lipid deposition, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Subsequent Western blotting and quantitative PCR confirmed significant down regulation of CDK5RAP3 at both the protein and mRNA levels in the liver tissues of these mice. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated weakened colocalization signals between albumin (Alb) and CDK5RAP3, indicating compromised hepatocyte-specific functional integrity. Crystal violet staining of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)-induced CKO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) showed a marked reduction in cell numbers compared to wild-type controls, further corroborating impaired proliferative capacity. These phenotypes were closely associated with aberrant activation of apoptotic pathways. Follow-up investigations identified elevated levels of the pro-apoptotic factor BAX in CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep mice, resulting in a significant increase in the BAX/Bcl-2 ratio. Annexin V/PI dual-labeling flow cytometry analysis confirmed a substantial increase in apoptotic cell numbers, consistent with the elevated BAX/Bcl-2 ratio. These findings underscore the critical role of CDK5RAP3 in maintaining hepatic function and hepatocyte homeostasis. Previous studies have shown that CDK5RAP3 suppresses gastric cancer progression by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [

23,

24]. Thus, it is hypothesized that the absence of this regulatory protein may disrupt cell cycle control, thereby hindering hepatocyte survival and proliferation. Notably, the functional role of CDK5RAP3 in the liver may differ substantially from its effects within the tumor microenvironment, warranting further mechanistic exploration [

19,

23].

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a key driver of hepatitis, triggers an inflammatory cascade via Caspase-1-mediated maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 [

25,

26].Our data revealed not only upregulation of NLRP3 and Caspase-1 but also significant increases in ASC and GSDMD expression at both mRNA and protein levels in the livers of CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep mice, indicating robust inflammasome activation. These observations align with the findings of Mridha et al., which emphasize the central role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in liver injury pathologies such as fibrosis and steatosis [

27,

28]. Immunofluorescence labeling further localized enhanced NLRP3 and ASC speck formation within CDK5RAP3-deficient hepatocytes, confirming inflammasome assembly at the cellular level. Unlike classical NLRP3 activation mechanisms [

29], this study is the first to identify CDK5RAP3 as an endogenous negative regulator that maintains hepatic homeostasis by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome assembly. This discovery provides novel insights into the pathological imbalance between inflammatory responses and regenerative capacity in chronic liver diseases [

24,

30].

CDK5RAP3 deficiency concurrently exacerbates apoptosis and pyroptosis, potentially establishing a self-reinforcing "inflammation-death" feedback loop that promotes tumor progression. GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis releases damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs, e.g., ATP), which activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and synergize with apoptotic pathways to amplify inflammatory responses [

31,

32]. Our results demonstrated a significant elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, at both protein and mRNA levels in CDK5RAP3Δ/Δhep mice, intensifying inflammatory signaling. Such dual cell death modalities have been previously documented in pyroptosis research [

33]. This study highlights CDK5RAP3 as an upstream regulatory hub coordinating both death pathways [

26,

34].

To validate the causal role of CDK5RAP3 deficiency in inflammation-driven apoptosis, a tamoxifen-inducible knockout model was established using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Embryonic fibroblasts from experimental mice were treated with 4-OHT, whereas the controls received ethanol (EtOH). 4-OHT administration markedly increased apoptosis rates, suppressed cell growth, and down regulated CDK5RAP3 expression levels. In addition to the elevated production of inflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 pathway components, WB and q-PCR analyses confirmed a significant increase in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. These results suggest that CDK5RAP3 deficiency initiates a self-amplifying "inflammation-death" cycle, exacerbating hepatocyte injury through the coordinated activation of apoptosis and pyroptosis.While MEFs offer flexibility for genetic manipulation, the absence of liver-specific microenvironments (e.g., metabolic stress and immune cell interactions) may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should validate these results using organoid models and primary hepatocyte cultures.

Figure 6.

CDK5RAP3 Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Inflammation via NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis and Apoptotic Crosstalk A schematic illustration depicts the pathological cascade triggered by CDK5RAP3 deficiency in mouse livers, involving dual activation of inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis and apoptosis.

Figure 6.

CDK5RAP3 Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Inflammation via NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis and Apoptotic Crosstalk A schematic illustration depicts the pathological cascade triggered by CDK5RAP3 deficiency in mouse livers, involving dual activation of inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis and apoptosis.

In summary, CDK5RAP3 deficiency induces apoptosis and pyroptosis by dysregulating the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and altering the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, positioning CDK5RAP3 as a potential therapeutic target for liver disease.

The role of NLRP3 in chronic liver diseases (e.g., NASH) is stage-dependent: early pro-inflammatory responses aid in clearing damaged cells, but persistent activation promotes fibrosis [

28,

35]. Although this study focused on CDK5RAP3’s impact, it did not comprehensively address interactions with other pathways, such as NF-κB or MAPK [

36,

37]. Further research should clarify these interactions and employ co-immunoprecipitation assays to determine whether CDK5RAP3 directly binds ASC or NLRP3 to regulate inflammasome assembly.

NLRP3-targeting small-molecule inhibitors (e.g., MCC950) have demonstrated clinical potential [

30,

38]. Our findings provide a theoretical foundation for exploring CDK5RAP3’s therapeutic value in liver diseases and advance our understanding of its role in hepatic inflammation. Future investigations should extend to other liver pathologies (e.g., cirrhosis and fibrosis) and assess their viability as therapeutic targets.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Table S1 Antibodies used in this paper. Table S2 Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR.

Author Contributions

Y.C. and L.S. codesigned this experiment; X.C., Q.H., Y.W., H.Y., F.C., F.L.,and H.K., participated in all experimental work; Q.H. analyzed the experimental data; X.C. and Y.W. wrote and calibrated the manuscript. All the authors have read and authorized the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 32270516; 31970413), and also supported by Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (SRT, 201410307041Z).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Theanimal-related procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University, China, with the approval number 20220615.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Guo Maliy, Xu Junjie, and everyone in Professor Cai Yafei's laboratory for their assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in the submission of this manuscript, and the manuscript is authorized to be published by all authors.

References

- Lee, Y.A.; Friedman, S.L. Inflammatory and Fibrotic Mechanisms in NAFLD-Implications for New Treatment Strategies. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 11–31. [CrossRef]

- Ching, Y.P.; Qi, Z.; Wang, J.H. Cloning of Three Novel Neuronal Cdk5 Activator Binding Proteins. Gene 2000, 242, 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, X.; Luo, Y.; Yarbrough, W.G. A Novel ARF-Binding Protein (LZAP) Alters ARF Regulation of HDM2. Biochem. J. 2006, 393, 489–501. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-F.; Lin, N.; He, D.-Q.; Xu, M.; Zhong, L.-Y.; He, S.-Q.; Guo, D.-H.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.-L.; Zheng, X.-Q.; et al. LZAP Promotes the Proliferation and Invasiveness of Cervical Carcinoma Cells by Targeting AKT and EMT. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 1625–1633. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, S.; Li, H. Cdk5 Activator-Binding Protein C53 Regulates Apoptosis Induced by Genotoxic Stress via Modulating the G2/M DNA Damage Checkpoint. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 20651–20659. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, X.; Su, M.; Shen, H.; Qiu, W.; Tian, Y. CDK5RAP3 Participates in Autophagy Regulation and Is Downregulated in Renal Cancer. Dis. Markers 2019, 2019, 6171782. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-X.; Xie, X.-S.; Weng, X.-F.; Qiu, S.-L.; Xie, J.-W.; Wang, J.-B.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Cao, L.-L.; Lin, M.; et al. Overexpression of IC53d Promotes the Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells by Activating the AKT/GSK3β/Cyclin D1 Signaling Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 2739–2752. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, W.-D.; Melville, D.B.; Cha, Y.I.; Yin, Z.; Issaeva, N.; Knapik, E.W.; Yarbrough, W.G. Tumor Suppressor Lzap Regulates Cell Cycle Progression, Doming, and Zebrafish Epiboly. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2011, 240, 1613–1625. [CrossRef]

- Mak, G.W.-Y.; Chan, M.M.-L.; Leong, V.Y.-L.; Lee, J.M.-F.; Yau, T.-O.; Ng, I.O.-L.; Ching, Y.-P. Overexpression of a Novel Activator of PAK4, the CDK5 Kinase-Associated Protein CDK5RAP3, Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2949–2958. [CrossRef]

- Mak, G.W.-Y.; Lai, W.-L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.; Ng, I.O.-L.; Ching, Y.-P. CDK5RAP3 Is a Novel Repressor of p14ARF in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. PloS One 2012, 7, e42210. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jiang, H.; Luo, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, F.; Huang, S.; Li, H. Caspase-Mediated Cleavage of C53/LZAP Protein Causes Abnormal Microtubule Bundling and Rupture of the Nuclear Envelope. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 691–704. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Kang, B.; Chen, B.; Shi, Y.; Yang, S.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, T.; et al. CDK5RAP3, a UFL1 Substrate Adaptor, Is Crucial for Liver Development. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2019, 146, dev169235. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-S.; Wu, C.-W.; Hsu, K.-W.; Liao, W.-J.; Yang, M.-C.; Li, A.F.-Y.; Wang, A.-M.; Kuo, M.-L.; Chi, C.-W. The Activated Notch1 Signal Pathway Is Associated with Gastric Cancer Progression through Cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 5039–5048. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-C.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.-M.; Wang, L.-L.; Wu, X.-L. Gastric Cancer Cell Growth and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Are Inhibited by γ-Secretase Inhibitor DAPT. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 2160–2164. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, K.; Moura, R.F.; Granvik, M.; Igoillo-Esteve, M.; Hohmeier, H.E.; Hendrickx, N.; Newgard, C.B.; Waelkens, E.; Cnop, M.; Schuit, F. Ubiquitin Fold Modifier 1 (UFM1) and Its Target UFBP1 Protect Pancreatic Beta Cells from ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis. PloS One 2011, 6, e18517. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Núñez, G. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Activation and Regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 331–344. [CrossRef]

- Seoane, P.I.; Lee, B.; Hoyle, C.; Yu, S.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; Lowe, M.; Brough, D. The NLRP3-Inflammasome as a Sensor of Organelle Dysfunction. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e202006194. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.I.; Lu, A.; Chen, J.W.; Ruan, J.; Tang, C.; Wu, H.; Ploegh, H.L. A Single Domain Antibody Fragment That Recognizes the Adaptor ASC Defines the Role of ASC Domains in Inflammasome Assembly. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 771–790. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P.-Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Molecular Activation and Regulation to Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Yi, T.; Chen, C. NF-κB-Gasdermin D (GSDMD) Axis Couples Oxidative Stress and NACHT, LRR and PYD Domains-Containing Protein 3 (NLRP3) Inflammasome-Mediated Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis Following Myocardial Infarction. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 6044–6052. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Cai, T.; Wang, F.; Shao, F. Cleavage of GSDMD by Inflammatory Caspases Determines Pyroptotic Cell Death. Nature 2015, 526, 660–665. [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wan, H.; Hu, L.; Chen, P.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Z.-H.; Zhong, C.-Q.; Han, J. Gasdermin D Is an Executor of Pyroptosis and Required for Interleukin-1β Secretion. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 1285–1298. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.-H.; Wang, J.-B.; Lin, M.-Q.; Zhang, P.-Y.; Liu, L.-C.; Lin, J.-X.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Cao, L.-L.; Lin, M.; et al. CDK5RAP3 Suppresses Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by Inhibiting AKT Phosphorylation in Gastric Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2018, 37, 59. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-B.; Wang, Z.-W.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.-Q.; Zheng, C.-H.; Li, P.; Xie, J.-W.; Lin, J.-X.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q.-Y.; et al. CDK5RAP3 Acts as a Tumor Suppressor in Gastric Cancer through Inhibition of β-Catenin Signaling. Cancer Lett. 2017, 385, 188–197. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, G.; Petrasek, J. Inflammasome Activation and Function in Liver Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 387–400. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Cell Death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 2114–2127. [CrossRef]

- Mridha, A.R.; Wree, A.; Robertson, A.A.B.; Yeh, M.M.; Johnson, C.D.; Van Rooyen, D.M.; Haczeyni, F.; Teoh, N.C.-H.; Savard, C.; Ioannou, G.N.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Blockade Reduces Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis in Experimental NASH in Mice. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 1037–1046. [CrossRef]

- Wree, A.; McGeough, M.D.; Peña, C.A.; Schlattjan, M.; Li, H.; Inzaugarat, M.E.; Messer, K.; Canbay, A.; Hoffman, H.M.; Feldstein, A.E. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Is Required for Fibrosis Development in NAFLD. J. Mol. Med. Berl. Ger. 2014, 92, 1069–1082. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Kanneganti, T.-D. The Regulation of the ZBP1-NLRP3 Inflammasome and Its Implications in Pyroptosis, Apoptosis, and Necroptosis (PANoptosis). Immunol. Rev. 2020, 297, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Mangan, M.S.J.; Olhava, E.J.; Roush, W.R.; Seidel, H.M.; Glick, G.D.; Latz, E. Targeting the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Inflammatory Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 588–606. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, P.; Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Qiao, C.; Liu, W.; Deng, H.; Li, J.; Ning, P.; et al. Pyroptosis in Inflammatory Diseases and Cancer. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4310–4329. [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Tang, L.; Peng, C.; Chen, X. Pyroptosis: Mechanisms and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 128. [CrossRef]

- Bertheloot, D.; Latz, E.; Franklin, B.S. Necroptosis, Pyroptosis and Apoptosis: An Intricate Game of Cell Death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1106–1121. [CrossRef]

- Raneros, A.B.; Bernet, C.R.; Flórez, A.B.; Suarez-Alvarez, B. An Epigenetic Insight into NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Inflammation-Related Processes. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1614. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Hong, W.; Lu, S.; Li, Y.; Guan, Y.; Weng, X.; Feng, Z. The NLRP3 Inflammasome in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis: Therapeutic Targets and Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 780496. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. Targeting NF-κB Pathway for the Therapy of Diseases: Mechanism and Clinical Study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 209. [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Ro, S.W. MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 3026. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Oshaghi, E.; Mirzaei, F.; Pourjafar, M. NLRP3 Inflammasome, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis Induced in the Intestine and Liver of Rats Treated with Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: In Vivo and in Vitro Study. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1919–1936. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).