1. Introduction

Anchovy is one of the world’s most significant captured marine fish species, belongs to the family of

Engraulidae [

1]. European anchovies (

Engraulis encrasicolus) are the third most important type of anchovies with an estimated production of 595.527 tons in 2022 [

2]. This species ranks first in the fisheries in Turkey with a production of 273.914 tons in 2023. It is considered to be the most important fish species, both commercially and biologically, for the Black Sea environment and other seas of different nations [

1,

3,

4,

5]. Anchovy is a popular and widely utilized fish in human and animal diets worldwide [

2]. This species is known for its superior nutritional value due to its rich content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), especially omega-3 fatty acids [

6,

7,

8]. About twenty-five grams of European anchovy originated from the Northeast of Black Sea is sufficient to meet the daily requirement for n-3 PUFA, while approximately 130 g is a satisfactory level for total eicosapentaenoic acid + docosahexaenoic acid (EPA+DHA) for the suggested weekly requirement defined by different health authorities [

8,

9]. However, anchovy has a high production volume due to the limited fishing season. The catch needs to be preserved immediately, as this species has a high oil content leading to rapid autolytic spoilage [

10]. Consequently, a number of preservation strategies are applied to distribute high catch volumes throughout the year. The most popular of these is freezing, followed by marinating and salting. Frozen anchovies are sold below value at the start of new anchovy seasons, either for human consumption or for feed, such as tuna, because of low consumer demand [

11].

As one of the least expensive preservation and processing techniques, salting has a longstanding history in the seafood sector, particularly in developing nations. This traditional technique is widely used around the world as it is a simple and inexpensive way to prevent fish from spoiling and seafood from becoming unsafe to eat. It is also used in combination with other fish processing and preserving methods. These include drying, fermenting, marinating and smoking techniques. The dry salting and brining are known as the common salting methods. Depending on the availability of raw materials, anchovies can be salted from fresh or pre-frozen fish. However, since fresh anchovies are highly sensitive to deterioration, they are often frozen in the fish processing industry [

12,

13]. Past studies have also reported that this species has a high susceptibility to parasitic infections, in particular by

Anisakis pegreffii and A. simplex [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. For this reason, freezing is the preferred method to inactivate parasites, as the European Commission (EC) requires that fish products intended for consumption raw or semi-raw without cooking must be frozen at a temperature not exceeding -20°C for 24 hours before such industrial processing [

19,

20]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also requires that any fish and shellfish intended for eating raw or semi-raw (i.e., marinated or partially cooked) must be blast frozen at or below -35°C for 15 hours or completely frozen at or below -20°C for 7 days [

21,

22]. Freezing of fish for such products is also required by other countries such as Canada [

23]. However, several studies have reported adverse effects of freezing on the quality of traditional fish products, such as its effect on the texture and protein structure of fish muscle [

3,

16,

19,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, certain countries like Spain, established technical salting parameters and curing time for the inactivation of

Anisakidae larvae, replacing the freezing method. According to AESAN [

28], fish should have a salt concentration of more than 9% for a minimum of six weeks, between 10% and 20% for a minimum of four weeks, or more than 20% for a minimum of three weeks for inactivation of

Anisakis sp. Nevertheless, many studies have shown that freezing has many additional advantages over traditional fish processing methods (e.g., marinating, salting and smoking) beyond the neutralization of parasites in fish. Some of these are faster salt uptake and extended shelf-life compared to using fresh raw materials, which accelerates maturation and delays the development of biogenic amines [

26,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

The effect of freezing/frozen storage on the quality of salted fish products is likely to be influenced by the duration of storage of the frozen raw material. Previously, we have demonstrated that dry-salted and brined anchovies in 30% brine have a longer shelf life at refrigerated temperatures than anchovies freshly used before salting for samples obtained from previously frozen raw materials [

34]. This beneficial effect was attributed to the faster absorption of salt by frozen anchovies after defrosting, particularly in groups containing high salt concentrations.

The seafood processing plants that freeze anchovies in Turkey fill their warehouses during the fishing season and then market their products as in many other countries. In this country, the frozen anchovies are processed into different fish products, including fish paste, marinated and smoked anchovies. Due to the oversupply of frozen products and certain economic factors, it is not possible to sell all the frozen anchovies from the previous season and therefore are sold at reduced prices as meal or feed for tuna farming in order to free up space for the new season. In order to avoid this, a suitable method should be chosen for the utilization of frozen anchovies from the previous season for human consumption without using energy for additional storage. Nevertheless, there is a need for cost-effective storage options because refrigerated storage uses energy to ripen and store salted fish, which raises the cost of manufacturing. The primary choice for this is ambient temperature. The impact of freezing before salting on the quality of salted European anchovies at room temperature has not yet been investigated. Thus, it was aimed to investigate the effect of the freezing/frozen storage of the raw materials prior to salting on the changes in quality and food safety during the storage of anchovies under ambient conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Rock salt (Billur Tuz, İzmir, Turkey) was provided from a local supermarket. Analytical and chromatography grades were used for chemicals and solvents and obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and Merck.

2.2. Experimental Design and Sample Preparations

Anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus, L) with mean weight and length of 10.21 ± 2.89 g and 12.48 ± 1.26 cm, respectively, were caught by commercial purse seiners from the Northeast of the Turkish Black Sea. The fish were landed a few hours after capture, divided into two batches, and transported on ice (1:1 fish:ice) to a commercial fish processing company, POLIFISH, within one hour. One batch was immediately washed and frozen at -40°C and then stored at -18±2°C for one year in the company’s cold store. The second batch was processed fresh (not frozen) on arrival (brining and dry salting) and was referred to as the control group. Freshly salted fish were stored at room temperature (17±3°C) until the organoleptic evaluation of spoilage was complete. The experimental group that was frozen and stored for one year was transferred to the laboratory using the company’s frigofrig system and was thawed overnight in a refrigerator (Arçelik 8810 NF, Turkey) at 4±1°C immediately prior to processing. Subsequently, processing and storage were carried out using the same procedures as for fresh salted fish.

2.3. Salting, Storage and Sampling Procedures

Each group received two different salting treatments: brine and dry salting. Fish were beheaded, gutted, and washed under running tap water for each type of salting. Dry salting was performed in 2 glass jars (8 L each) using a 3:1 (w:w) fish:salt ratio, in layers starting in the bottom and ending with top salted layers. Two types of salting were applied to each group, namely brining and dry salting. The first brine containing blood was replaced with fresh saturated brine after two weeks of maturation. Five distinct salt concentrations (10, 15, 20, 25, and 30%) with a fish:brine (w:w) ratio of 1:2 were applied to duplicate glass jars for brining (10 glass jars in total, each containing 8 L). Weights were applied to the fish to prevent them from floating in the water. The brine solution was replaced at the end of the first week for the groups with a salt concentration of 10, 15 and 20% and at the end of the second week for the groups with a salt concentration of 25 and 30%. All groups were stored at ambient temperature (17±3°C) for further storage. Sampling was performed three times, weekly for the 1st month and then monthly for up to one year, to monitor changes in quality and the formation of biogenic amines to ensure product safety. Each sampling, weighing approximately 500 g, was performed under sterile conditions to avoid microbial contamination. A portion of the sample (200 g) was used for organoleptic analysis, another portion (100 g) for microbial counts and the remaining portion for chemical and physical analysis. The analytical procedures are described below.

2.4. Organoleptic Analysis

A modified approach based on the techniques of Amerina et al. [

35], Hernandez-Herrero et al. [

36], Karaçam et al. [

37], and Archer [

38] was used for organoleptic evaluation. Dry salted and brined fish samples were evaluated for texture, odor, color, and overall appearance. Taste analysis was not done in the study. The overall acceptability of the samples was rated by eight trained panelists (MSc and PhD students) using a ten-point descriptive scale. The scale indicates that the organoleptic rating of a sample is 10-9 for excellent, 8-7 for good, 6-5 for fair, and 4-5 for “borderline” between acceptable and unacceptable, <4 is unacceptable.

Supplementary Table S1 represents the criteria applied for the organoleptic evaluation.

2.5. Measurements of aw pH, Weight and Length

A water activity meter (AQUALAB TE3) was used to measure water activity (a

w) in accordance with the guidelines provided by Minegishi et al. [

39]. A digital pH-meter (Jenco 6230N, CA, USA) was used to measure pH by placing electrodes on samples containing 5 g homogenized fish meat with 10 mL distilled water. Triplicate readings were taken for both a

w and pH. The weight was measured by a laboratory balance (Ohaus, PR1602, ±0.01 g), and the total length was measured by a fish measuring board (±0.1 cm).

2.6. Chemical Analysis

Oven-drying method AOAC [

40] was used to determine moisture content by drying 5 g of fish muscle in an oven at 105°C until a constant weight was obtained. The salt (NaCl) content of fish muscle was determined using the Mohr method according to Rohani et al. [

41]. Using the following equation Losikoff [

42], the water phase salt (WPS) was estimated from the amount of salt in the product depending on the moisture content and the salt content.

Total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) in fish muscle was determined according to Goulas and Kontominas [

43], while thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was analysed by the method of Smith et al. [

44]. Trimethylamine (TMA) analysis was performed according to the method of Boland and Paige [

45]. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu Prominence LC-20 AT series) with an autosampler (SIL20AC, Japan) was used to determine biogenic amines as reported by Köse et al. [

46] and Koral et al. [

47]. The column was Inertsil (GL Sciences, ODS-3, 5µm, 4.6x250 mm). The sampling was carried out in triplicate for each group.

2.7. Microbiological Analysis

The counts of total viable aerobic mesophilic bacteria (TVAMB) were conducted in accordance with Halkman [

48] and Salfinger and Tortorello [

49]. Twenty-five grams of sample was weighed under aseptic conditions into a sterile stomacher bag containing 225 mL of sterile physiological saline solution (0.85 %). The weighed sample was thoroughly shredded and homogenized with 225 mL of 0.85% physiological saline in a stomacher (Mayo, HG 400 V, Italy) for 4 minutes at the highest setting level. Additional decimal dilutions were made in saline (0.85%). TVAMB were enumerated on standard plate count agar (SPCA) which were incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. After incubation, Petri plates containing 30-300 colonies were counted, and the numbers of AMB were calculated. The results of the counting are expressed in colony-forming units per gram (cfu/g).

Histamine-forming bacteria (HFB) were identified using a modified Niven medium described by Köse [

50]. According to this method, the total HFB isolation agar is composed of 2.35% L-histidine-HCl, 2% agar, 0.5% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 0.1% CaCO

3 and 0.06% bromocresol violet with a pH 6.5 [

51]. For the determination of mesophilic HFB, the same incubation conditions as for TVAMB were applied. Halophilic bacteria (HB) counts were conducted as described by Halkman [

48], and Gürgün and Halkman [

52]. The same incubation conditions applied to TVAMB were used to determine mesophilic HFB. Halophilic bacteria (HB) counts were performed in accordance with Halkman [

48] and Gürgün and Halkman [

52].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and, when significant differences were detected, the means were compared using Tukey and Mann-Whitney U-tests (data not meeting assumptions of normality) in JMP 5.0.1 (SAS Institute., USA) and SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) [

53]. All analyses were performed at a 95% significance level (p < 0.05). Microsoft EXCEL, 2016 was used for linear regression analysis.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Organoleptic Analysis

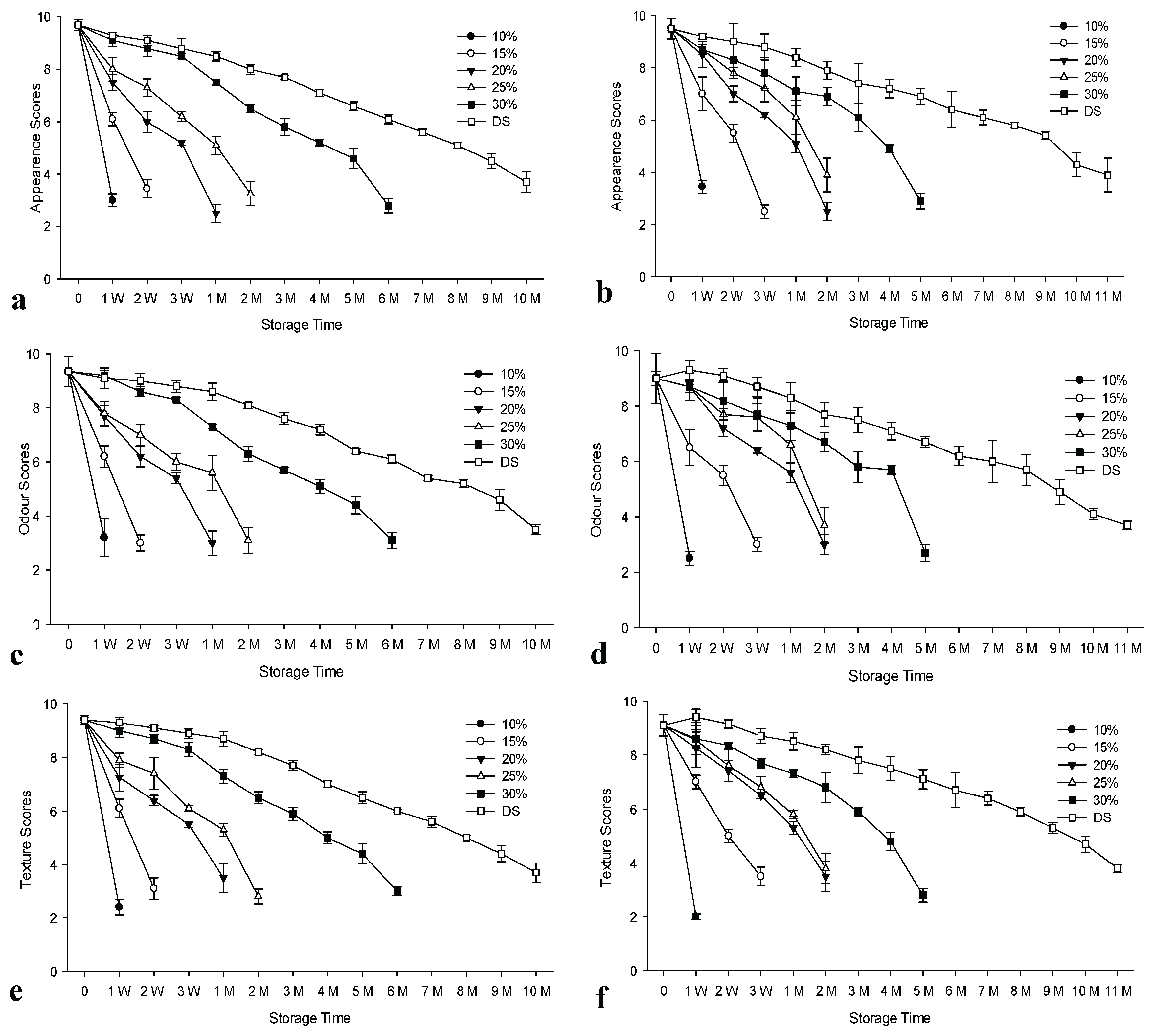

Figure 1 (a-g) shows the values obtained from organoleptic analysis of salted anchovies for the control group (used fresh raw materials) and the experimental group (used raw materials previously frozen stored for 1 year and defrosted prior to processing) stored at ambient temperature. Salt concentration significantly affected the shelf-life of products (p<0.05) (

Supplementary Table S2). The longest shelf-life of 10 months was observed for dry-salted products. Previous studies supported these findings relating to the effect of salt concentration during the storage of ripened anchovies for both refrigerated and ambient conditions [

34,

37,

54]. However, in our earlier study, we demonstrated higher shelf- life for all salt concentrations at refrigerated temperatures for the brined anchovies processed from previously frozen/thawed raw materials [

34]. According to the overall scores, products brined at 10% spoiled at the 1st week for both control and experimental groups. The shelf-life of products in brine at 15, 20, 25 and 30% salt concentration was 1 week, 3 weeks, 1 month and 5 months respectively for the control group. Higher shelf lives were obtained for the experimental group brined at 15% and 20% salt for 2 weeks and 1 month, in the same order, while the samples with 25% salt had a similar shelf-life. However, the samples brined at 30% corresponded to 4 months of storage life. On the other hand, the experimental group for dry-salted products had a one-month higher shelf-life compared to the control group, indicating the benefits of using previously frozen/defrosted raw material for this process, while this advantage was only one week for brined samples salted at 15-25% concentrations. Our previous study also demonstrated the advantage of using refrigerated storage with a higher shelf-life for both groups [

34]. It was reported that frozen/defrosted anchovies matured successfully, yielding a product with fully acceptable sensory properties. However, freezing before processing slowed down the ripening process [

55].

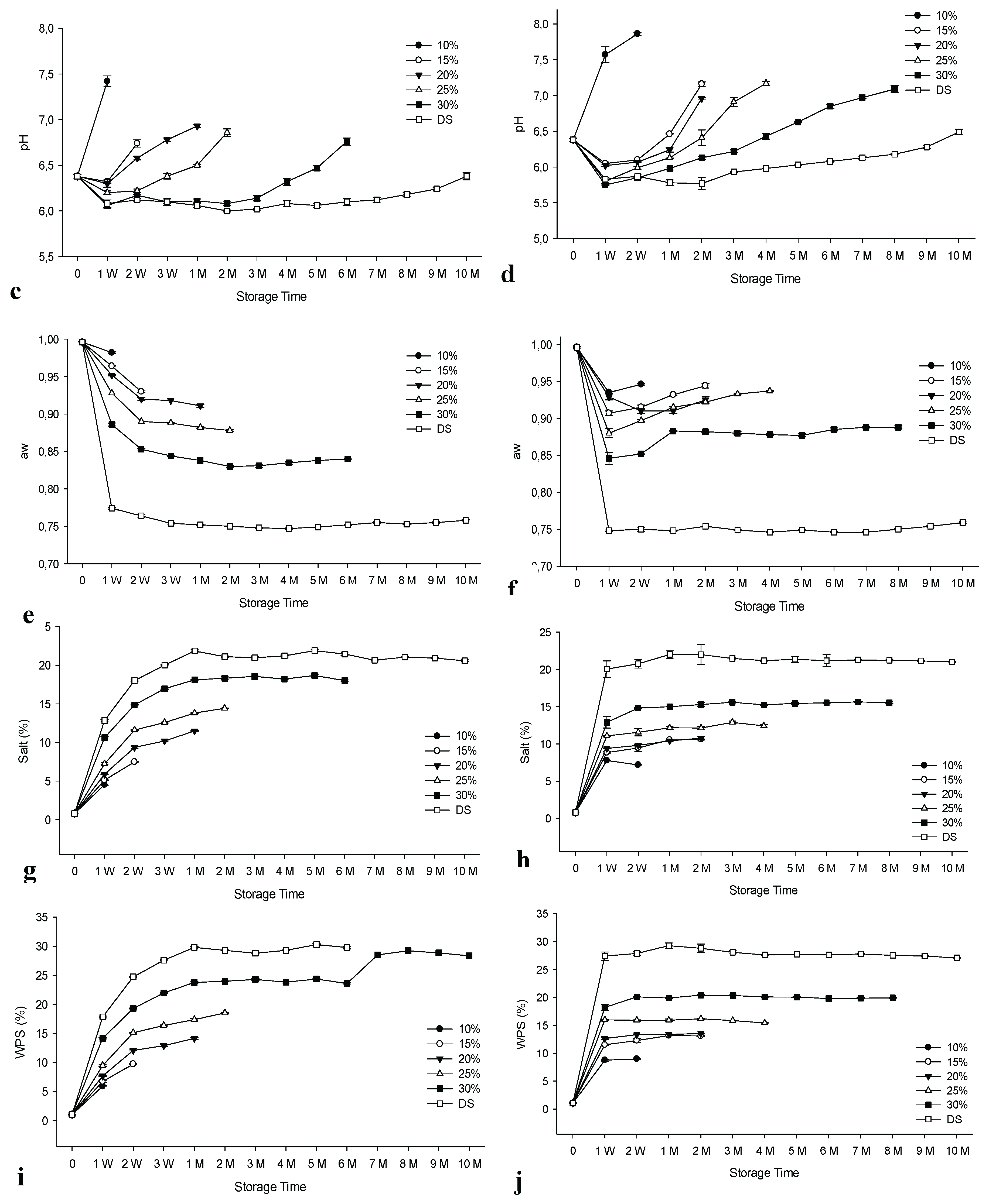

3.2. Results of Moisture Contents

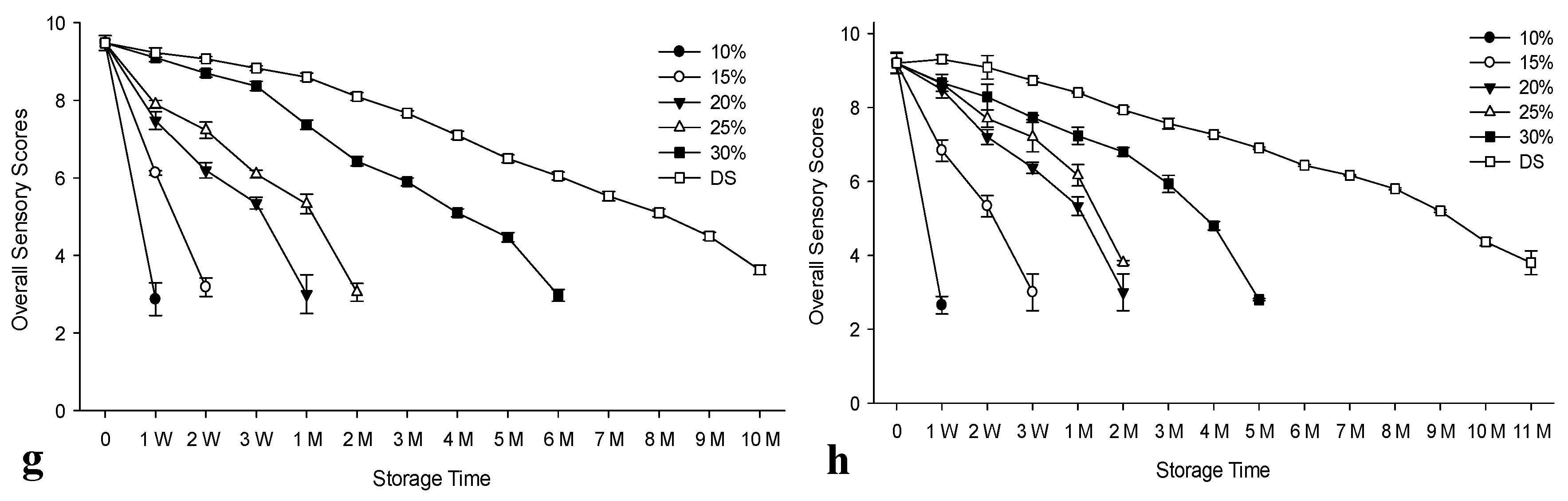

Salt curing is primarily used to reduce moisture content, thereby lowering water activity.

Figure 2 shows the results of moisture content throughout the maturation of anchovy stored at ambient temperature for all groups. The moisture content of the brine samples decreased significantly (p<0.05) in parallel with the increase of the salt concentration in the brine, except for 10% (Sup.

Table S2). For all subgroups of the control group (except 10% salt), there were strong negative correlations between moisture and salt contents and positive correlations between moisture and aw values. Correlation coefficient results for moisture and salt content varied in R

2: 0.91 - 0.99, while between moisture and aw contents ranged in R2: 0.88 - 0.99 for the control group depending on salt concentrations and salting method (

Table 1,

Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

Freezing/frozen storage of raw materials before processing had a significant (p<0.05) effect on salt intake as well as on the reduction of moisture and aw values. However, a slightly weaker correlation was observed for the experimental group, ranging from R

2: 0.49 to 0.96 and from R2: 0.82 to 0.98, respectively (

Table 1).

Using different salt concentrations and salting methods resulted in significant differences in moisture content between treatments (p<0.05). In addition, the percentage decrease in moisture content of dry-salted fish was faster than that of brined fish (p<0.05). The changes in the moisture content of the brined samples were generally insignificant after 2 weeks at the 20% and 25% salt concentrations and for the control group during the first month in relation to the 30% salt concentration and the dry salted product. For the experimental group, no significant changes in the values of the dry salt samples occurred during storage after 1st week. In fact, in the opposite case, salt values closely correlated to these results (

Figure 2). The lowest moisture content was determined for the dry salted samples as 50.42% on the 5th month for the control group and as 53.08% on the 1st week for the experimental group. The values obtained by Czerner and Yeannes [

56] and Koral et al. [

34,

46] for salted-ripened anchovies supported our findings.

3.3. Results of Salt Contents

Significant differences in salt content levels between the control and experimental groups were also obtained with some exceptions (p<0.05). Significantly higher salt intake was obtained for the experimental group compared to the control group until the 1st month (p<0.05), after which higher levels were obtained for the control group for the brined samples (

Figure 2, Sup.

Table S2). Changes after the second week were generally insignificant. In addition, salt intake of the brined samples was also influenced by salt concentration of the brine solution (p<0.05). The fastest salt uptake occurred in dry-salted products for both control and experimental groups (

Figure 2). Anastasio et al. [

16] showed that

Anisakis pegreffii larvae were devitalized within 15 days by a dry salting procedure with 21% salt content in whole anchovy fillets. The present study supports this finding, since the salt levels of the dry-salted anchovies originated from pre-frozen reached the same level in both groups after one month of storage. Furthermore, most parasites can be destroyed by freezing and frozen storage. This is important when the focus is on the processing of the salted fish into marinated products that are then to be consumed without being cooked [

11]. The previous study also supported the findings of this study [

34]. The previous findings also demonstrated that the amount of salt in several commercial dry-salted and brined anchovies from different countries were within the safety levels to prevent bacterial growth [

47].

3.4. Results of Water Activity (aw) Contents

The amount of the salt in the products significantly influenced the levels of aw. The lowest aw value was obtained with the highest salt content (

Figure 2). Initial aw was 0.996 in both groups and decreased significantly (p<0.05) after 1st week, with one exception. Thereafter, the levels gradually raised with significant variations for both groups (p<0.05) (

Figure 2, Sup.

Table S2). Values for dry salted products generally stabilized after the 1st week. The values also significantly differed among the different brine concentrations in both groups (p<0.05). The experimental group showed a significant decrease in aw levels faster than the control group (p<0.05), which showed a reverse trend in salt intake. The results showed that there was a strong negative correlation between the values of salt and aw for the control group with R

2 values between 0.94 and 0.99, whereas a weaker correlation occurred for the experimental group relating the brine samples with R

2 values between 0.58 and 0.93 (

Table 1,

Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). However, the correlation between salt and aw for dry salted products was also high, as R

2= 0.98. As the concentration of salt in the brine samples increased, the values of aw decreased in both groups. The lowest values were represented by the dry-salted samples for each group. Water activity is known as a growth limiting factor for microorganisms. Under FDA guidelines, the minimum aw value to allow growth of

Staphylococcus aureus is 0.83 and toxin formation is 0.85 when salt is used [

22]. For the dry-salted anchovies, the aw values of both groups were typically within the safety limit recommended by the FDA to prevent bacterial growth or toxin formation from the first week onward. However, except for the 30% salt concentrations representing the control group, aw values in both groups exceeded the recommended value (

Figure 2). Thus, the current study demonstrates the benefits of dry salting of both groups for salting anchovies in relation to food safety. In our previous study it was shown that brine samples prepared from pre-frozen raw materials reached the safety level earlier in the 1st and 2nd weeks for salt concentrations of 25% and 30%, respectively, stored at refrigerated temperature [

34]. Therefore, the earlier study indicated the advantage of using cold storage for ripening anchovies. The results of this study was also supported by the findings of the previous studies [

16,

33].

3.5. Results of pH

The initial pH of the salted anchovies decreased significantly, particularly faster for the experimental group. Then a significant increase occurred (p<0.05) in both groups with the exception of 10 % brined samples. The differences in pH between the control and experimental groups were also found significant (p<0.05) in relation to different salting methods/salt concentrations Product pH is important for the level of spoilage and food safety. However, it is generally used to assess the safety of the product. Huss [

57] stated that the pH value of the fish immediately after capture is between 6.0 and 6.5. Freshly caught fish is acceptable up to pH 6.8, but above 7.0 it is considered spoiled. Nonetheless, the basic proteases are crucial for the solubilization of connective tissue and degradation of myofibrillar protein at pH 6.5, which is the tissue’s post-mortem pH. It is therefore recommended that this measure be used along with other spoilage factors, particularly in the case of processed fish products [

10]. Despite the increase in pH during storage, the organoleptic examination showed that the pH values of all groups were at acceptable levels at the time of rejection. In addition, according to Besteiro et al. [

58], muscle enzymes such as cathepsins, especially cathepsin C, which has activity around pH 5.5-6.0, have been shown to contribute to the ripening process. Therefore, the salted/brined anchovies prepared from the raw materials which was previously kept for frozen for one year, and then thawed, usually have a better advantage in terms of pH values compared to freshly salted products. It has also been stated [

11,

22] that most pathogenic bacteria cannot grow or generate toxins at pH values below 5. The pH levels obtained for all groups were higher than 5, indicating that this criterion is insufficient to assess the safety of salted anchovies. Similar results were shown in our previous study for salted A. bonito and anchovy prepared from both fresh and pre-frozen/thawed raw materials under refrigerated conditions [

33,

34].

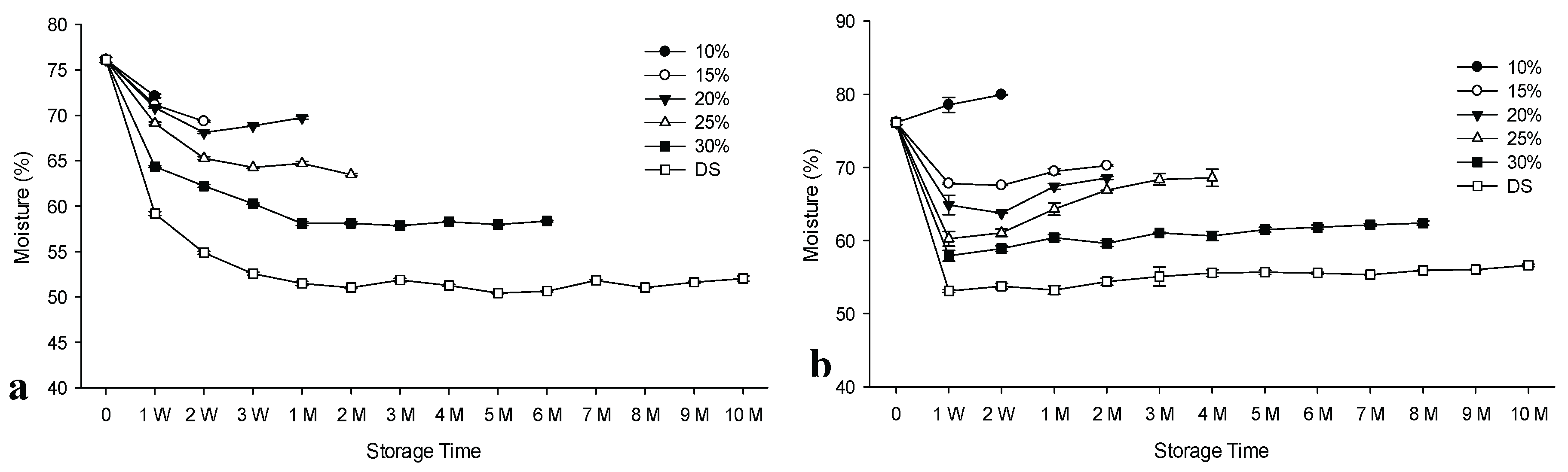

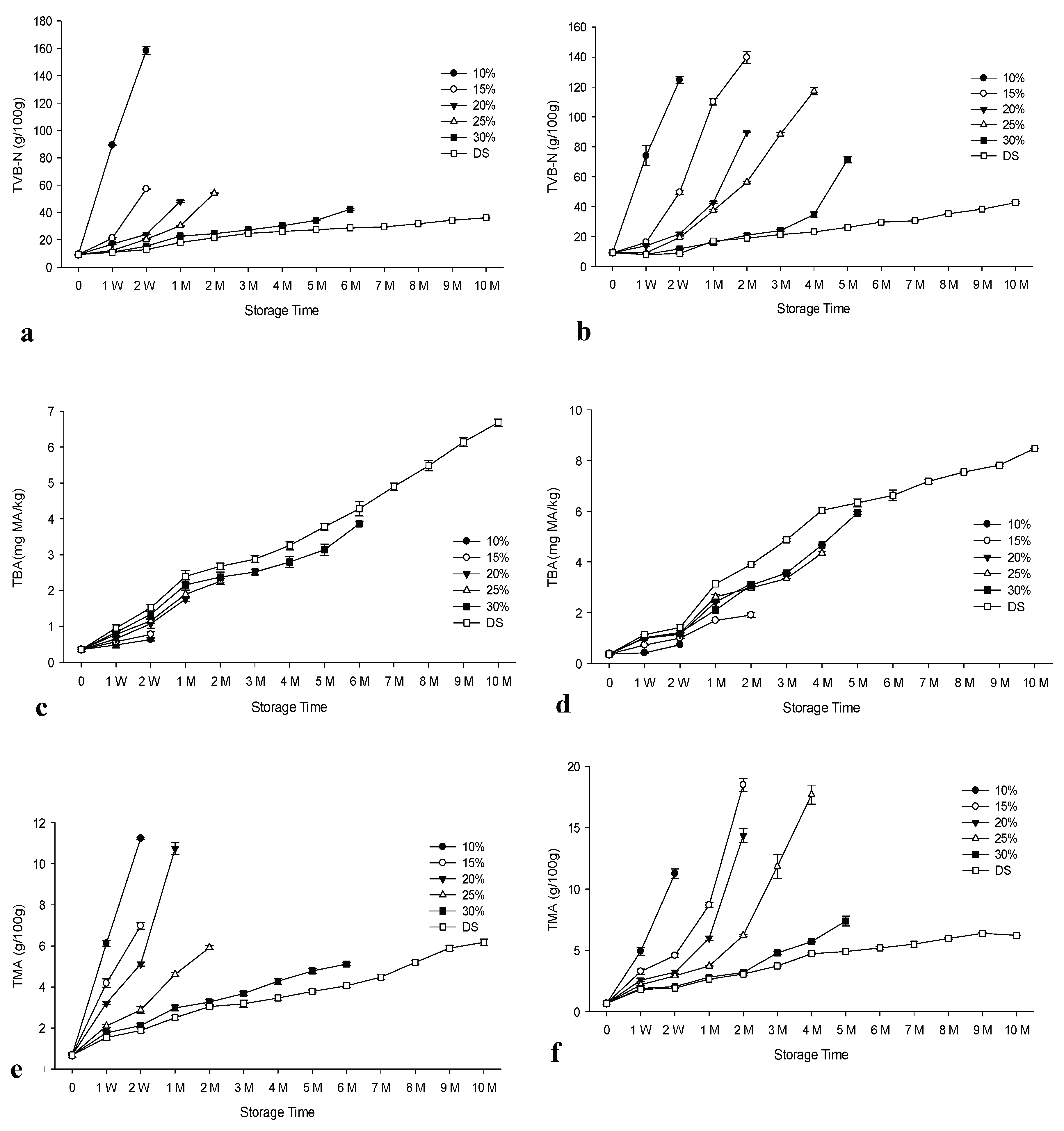

3.6. Results of Total Volatile Basic Nitrogen (TVB-N), Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) and Trimethylamine (TMA)

Figure 3 displays the results for TBA, TMA and TVB-N. There was a significant increase (p<0.05) in the values of these parameters for both groups during storage. Additionally, significant variations (p<0.05) were noted between the groups that differed in the concentration of the brine and in the method of salting, with a few exceptions (see

Table 2). Previous studies have also reported the effect of brine concentration on the results of these parameters for anchovies prepared from fresh raw material [

33,

34,

37,

59]. The presence of higher TBA levels in some samples may be due to dry salting, which makes the samples more susceptible to fat oxidation compared to brined samples. TVB-N and TMA levels increased significantly faster in the control group compared to the experimental group, with some exceptions (p<0.05).

3.6.1. TVBN Values

The European Union has set different limits for TVB-N of 25 - 35 mg/100 g for unprocessed fishery products that are considered unfit for human consumption when the organoleptic assessment raises doubt about their freshness [

20,

60]. However, anchovy is not part of the EU regulations for TVB-N assessment. Therefore, the TVB-N values can only be used as a support for the organoleptic values and the results of this study are in agreement with the organoleptic values of the control group, with the exception of the brine samples salted at a concentration of 30% and the dry salted products. Compared to the frozen/thawed salted anchovies, the samples brined at 10% and 30% concentrations and the dry salted products were in agreement with the organoleptic results. Very strong negative correlations between TVB-N and organoleptic scores were obtained for all groups, with correlation coefficients R

2: 0.87 - 0.98 for the control group and R2: 0.86-0.99 for the experimental group (

Table 2 and

Supplementary Tables S5 and S6).

3.6.2. TBA Values

TBA serves as a quality parameter, specifically in relation to lipid oxidation. Values lower than 5 mg MA/kg have been proposed as an indicator of high-quality fish, with an upper limit of 8 mg MA/kg for human consumption [

61]. A strong negative correlation was observed between the TBA results and the organoleptic values, with R

2 values ranging between 0.96 and 0.99 for the control group and 0.91 and 0.98 for the experimental group (

Table 2 and

Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). However, the obtained values did not reach the TBA limit for consumption. The highest value was determined for dry salted products as 8.48 for the experimental group at the end of the 10th month, when the products were spoiled, depending on the consumer panel. For both groups, brine samples at all concentrations showed good quality based on TBA values. According to Massa et al. [

62], TBA values may not indicate actual lipid oxidation rates, as malonaldehyde may interact with other fish constituents, such as lipid oxidation end products. They stated that this interaction differs between fish species. In a previous cold storage study, the highest TBA levels of 6.94 and 7.22 mg MA/kg were found in dry-salted anchovies for both experimental and control groups towards the end of the storage trial [

34]. Although our previous study with salted Atlantic bonito Koral & Köse, [

33] showed that freezing and frozen storage prior to salting can delay oxidative changes, the current study did not support these findings for salted anchovies frozen before processing. This situation can be attributed to the differences in salting methods, fish species and initial lipid content. Higher TBA levels were found in dry salted anchovies by Hernandez-Herrero et al. [

36]. The differences may be due to higher initial TBA levels.

3.6.3. TMA Values

Specific spoilage bacteria reduce trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), leading to the formation of TMA in fresh marine fish [

56,

63]. The maximum level for fresh fish was set at 15 mg/100 g [

64]. In this study, TMA was well below recommended limits with two exceptions. The highest values were 17.7 and 18.49 mg/100 g at the 2nd month of storage for the brine control group for 15% brine and the 4th month for 20% brine, respectively. A strong negative correlation was found between TMA and organoleptic scores for all groups. R

2 values ranged from 0.97 to 0.99 for the control group and from 0.88 to 0.99 for the experimental group (

Table 2 and

Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). TMA levels decreased with increasing salt concentrations, suggesting that the increase in salt concentration may delay TMA development for both groups. With few exceptions, the increase in values for the brined samples was higher in the control group than in the experimental group. This result shows the advantage of the freezing/thawing of the raw material prior to the salting process compared to non-frozen raw material. An opposite result was obtained for the dry-salted products, which is in agreement with our previous work Koral & Köse, [

33] using A. bonito that had been frozen/thawed prior to use. Siriskar et al. [

65] found an increase in the levels of TMA during storage of salt-pressed anchovies (

Stolephorus sp.), with levels up to 15.3 mg/100g at 5 weeks at ambient temperature.

3.7. Microbiological Results

Table 3 shows the microbial counts of the salted anchovies for both groups stored at ambient temperature. The initial TVAMB counts of fresh anchovies were 2.74 and HFB counts were 2.12 log cfu/g. Salt concentration significantly affected bacterial growth with some exceptions (p<0.05). These results were supported by previous studies [

34,

37,

66]. The study demonstrated that the bacterial load increases as the concentrations decrease. Thus, the lowest bacterial counts were observed for dry-salted anchovies for both groups, followed by the products in 30% brine. The control group generally had lower bacterial counts compared to the experimental group and differed significantly (p < 0.05) based on storage times and brine concentrations. TVAMB counts increased significantly for both groups (p<0.05) in brined samples during storage, except for 25% of the brined samples on the 2nd month. The counts remained below <1.47 log cfu/g in dry-salted products throughout storage. A similar situation was observed for the total number of HB and HFB. Limited growth was observed for HB in both groups during the 1st week of storage. Significant increases were recorded for brine samples (p<0.05). However, from the 1st week onwards, the HB count for dry-salted products was 1.47 log cfu/g for both groups. The International Commission for Microbiological Standards for Food [

67] recommends that raw fish products with a total bacterial count above 107 should be considered unacceptable.

In the present study, the overall plate counts of fresh raw material remained within an acceptable range. However, the highest counts of TVAMB in both groups were observed for the samples containing the lowest brine concentration (10%) in the 1st week of ripening (

Table 3) and were above the recommended limits. The results are consistent with the organoleptic values, given that samples at this concentration were spoiled by the end of the week. Low bacterial loads at various stages of ripened anchovies have been reported by several researchers [

34,

66,

68]. It

was reported that TVAMB counts in commercial dry-salted and brined products can range from

2.17 to 2.75 log cfu/g and from undetectable to 3.08 log cfu/g, respectively [

47]. More recently, Koral et al. [

34] reported that lower TVAMB counts for salted anchovies during refrigerated storage indicated the advantage of cold storage for the ripening period. The primary cause of deterioration of salted fish during storage is microbial activity, particularly salt-tolerant halophilic bacteria (HB). Previous research on such products has shown that HB counts are low or absent at the beginning of the ripening process and generally increase during storage [

65]. The results of HB supported previous research for dry-salted products for both groups and for samples brined at 25% and 30% brine concentrations for the control group. Previous studies have also shown that high salt concentrations and low storage temperatures inhibit HB bacterial growth [

34,

37,

65].

Similarly, the bacterial count results closely correlated with the aw values; the lower the aw, the lower the reported microbial counts. Total HB counts were varied in <1.47-7.14 and <1.47 log cfu/g for dry-salted and brined anchovies, respectively. For HFB counts, the values varied in 1.56-7.27 and <1.47 log cfu/g in the same respect [

47]. Hernandez-Herrero et al. [

36] reported decreasing levels of total viable bacteria and halophilic bacteria counts during the period of ripening. However, they also observed an increase in the levels of extreme HB. Although high levels of HB are generally associated with spoilage, some halophilic bacteria, in particular intermediate halophilic bacteria and extremely halophilic archaea, are also associated with an improvement in the quality of the anchovy [

56,

69,

70]. According to Yeannes et al. [

71], highly HB needs to grow in a medium containing 15-30% NaCl. Czerner and Yeannes [

56] showed that moderate HB dominated the ripening process of salted anchovies. They also reported that most of the isolates exhibited lipolytic, proteolytic, and TMAO reductase activity. They claimed that these activities contribute to the development of the distinctive flavor of the products and to the increase in TVB-N during the maturing process. Thus, the flavor development of salted anchovies may be facilitated by the presence HB during storage in the current study.

3.8. Results of Biogenic Amines

Histamine is produced by the decarboxylation activity of HFB, particularly

Klebsiella, Morganella, Vibrio, Photobacterium, and members of other genera [

11,

72]. However, halotolerant and halophilic histamine-producing bacteria of the genus

Staphylococcus, with strong histamine-producing activity, have generally been reported to be isolated during the maturation of salted anchovies. These bacteria have strong histamine-forming activity when exposed to 3% and 10% NaCl. Significant proteolysis is seen during the ripening process of salted anchovies, leading to the release of free amino acids and peptides. When free histidine is present in sufficient quantities, it can be degraded by microorganisms or their enzymes. As a result, histamine can be formed in the process and eventually reach toxic levels [

36].

In this study, anchovies corresponding to brine concentrations of 10% and 20% in both groups had a salt content of 10%, which is unsafe for histamine development during the maturing process. Moreover, the salt content of the brined anchovies relating to the control group was found to be below 10% at the end of the first week, which indicates the health risk for histamine development during this period. The salt content of other brine concentrations and dry-salted products remained over 10% throughout storage starting from the 1st and 2nd weeks for the experimental and control groups, respectively. The importance of initial HFB in fish stems from the fact that the histamine decarboxylase enzymes formed can continue to decarboxylate histidine to histamine even in the absence of live histamine decarboxylase-positive bacteria [

11]. A maximum average histamine value of 200 mg/kg is currently allowed in Europe for ripened anchovies, which is twice as much as is permitted for fresh or frozen fish [

20,

60]. The FDA has set a more stringent upper limit of 50 ppm for histamine in fish species because this level is typically the cause of multiple outbreaks and because histamine is not evenly distributed in the decomposed fish [

22].

In this study, histamine development was higher in samples salted at 10-20% brine concentration compared to higher brine concentrations and dry salted products (

Table 4). Histamine values increased significantly (p<0.05) during storage, except for dry salted anchovies. The control group exhibited slightly lower values compared to the experimental group, with some exceptions. Differences between the two groups were generally significant (p<0.05). Histamine values exceeded the levels permitted by EU regulation at the 2nd week, 1st and 2nd months for 10%, 15%, and 20% brine samples, respectively, while the other samples remained at acceptable levels throughout storage. However, the values reached the unacceptable levels set by the FDA in the 2nd week for 10% brined samples and in the 1st month for 15% and 20% brined samples. The values for the 30% brine and dry-salted samples remained below the detection limit from the beginning of storage until the 4th month. Then the values for the 30% brine samples increased significantly and reached the upper permissible limit set by the FDA at the end of the 8th month. The values for the dry salted products remained below the detection limit at the end of the storage period, even though they were spoilt by the organoleptic tests. Histamine values supported the organoleptic results of both groups for samples brined between 10% and 20% concentrations. Histamine values were well below the limits permitted by various health organizations for samples with higher salt concentrations and for dry salted products. These results indicate the food safety advantage of using higher salt concentrations for salted anchovies to be matured at ambient temperature. Our previous study also demonstrated the benefit of using cold storage during the ripening of brined and dry-salted anchovies [

34]. Karaçam et al. [

37] also showed histamine formation during the maturation of brined anchovy at ambient temperature and histamine inhibition during cold storage. Other studies have reported low levels of histamine formation during maturation of anchovies and other fish species [

33,

36,

68,

73]. Rodriguez-Jerez et al. [

74] stated that high histamine levels in salted fish may be due to a number of factors, including poor raw material quality, inadequate processing or other causes during storage. Thus, although Tapingkae et al. [

75] revealed some degradation of histamine activity, the salting process cannot eliminate already generated histamine in the raw material [

11]. In past literature, high histamine levels above the permissible levels set by the European Commission or the FDA have been reported in various commercial brine and dry salted anchovy products [

47,

76]. High concentrations may reflect poor raw material quality. In fact, Veciana-Nogués et al. [

77] showed that ripening has little effect on amine formation; therefore, the amount of amines in the final products is mainly determined by the concentrations of these compounds in the raw material. In later studies, they found that histamine and tyramine formation correlated well with other spoilage parameters (hypoxanthine, pH, TVB-N and TMA) during storage at both ambient and refrigerated temperatures [

78]. According to the European Commission [

79,

80], since 2015 there have been approximately 29 notifications of histamine health risks from anchovy products with histamine levels above 3000 ppm. Although the majority of anchovy products in these notifications related to fresh and canned anchovies, canned products were referred to as ‘in oil’, which may imply that they were salted and packed in oil, as this is a common anchovy salting technique in the seafood industry. In fact, high histamine contents were obtained at semi-preserved anchovies containing <15% salt during ripening at ambient temperatures [

81].

In addition to histamine, other biogenic amines are also important for the safety and quality of food. Due to their competition with enzymes metabolizing histamine, other biogenic amines present in foods, such as tyramine, putrescine and cadaverine, have been shown to have a potentiating effect in cases of histamine toxicity. In addition, about 30 mg/kg of phenylethylamine and 100 - 800 mg/kg of tyramine have been reported as toxic doses in food. Several studies have attempted to link varying concentrations of BAs to the spoilage of fish species [

82]. In the current study, high levels of putrescine, cadaverine and tyramine were determined for brined samples and significantly increased throughout the storage, with few exceptions (p<0.05). Similar results were obtained by the previous study for the samples kept at cold storage [

34]. Levels were generally below 20 ppm for phenylethylamine, spermine, spermidine and tryptamine for all product types. Although there were statistical differences among the groups, the levels fluctuated with inconsistent changes during storage. Cadaverine, putrescine and tyramine levels in 10% brine samples were significantly elevated to 448.76, 516.18 and 502.12 ppm, respectively, in the control group. Higher levels of 462.80, 587.41 and 521.98 ppm were obtained for the experimental group in the same respect, suggesting that freezing anchovies before processing may lead to additional formation of some biogenic amines. Tyramine results reached toxic levels (above 100 ppm) for the brined samples at 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30% concentrations at the 2nd week and 2nd and 4th months, respectively. However, tyramine values were well below the toxic levels for dry salted products throughout storage. Phenylethylamine levels were also found to be well below the recommended upper limit for all samples except those corresponding to 10% brine. Lower values were obtained for chilled brine anchovy samples in our previous study, demonstrating the benefit of cold storage [

34]. Low levels of BAs other than histamine have also been reported for commercially salted anchovies over a 14-month storage period [

83].

4. Conclusion

This study was carried out to investigate the possibility of storing salted anchovies, previously frozen and kept in frozen storage for one year, under ambient conditions with the aim of making them available for human consumption without causing economic losses. The results showed that the highest shelf-life corresponded to dry-salted anchovies, 10 to 11 months for the control and experimental groups, respectively. Brined samples had significantly lower shelf lives for both groups depending on salt concentrations, with shelf-life increasing as salt concentration increased. The storage life for brined samples was found to be less than a month for the samples brined at below 30% salt concentrations. Thus, if a long shelf-life is required for salted products prepared from anchovies frozen for one year, dry salting or brining at 30% salt concentration is required. On the other hand, products obtained by salting at lower concentrations can be consumed as salted products in a short time. They can also be used in the production of products such as marinated anchovies, fish paste and salted-dried anchovies within their shelf-life. Such applications will reduce the economic losses of the seafood factories in the region. It will also expand the range of products that can be processed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Serkan Koral (S. Kor.): Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing- original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, Sevim Köse (S.K.): Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing- original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Karadeniz Technical University Project Department, KTU-BAP project no. 2006.117.001.4.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Bekir Tufan of Karadeniz Technical University for his help for transporting fish samples. We also appreciate the help of the seafood company POLIFISH for their support in this study during freezing, storing and transporting the fish samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

References

- Şahin, C. , Akin, S., Hacimurtazaoglu, N., Mutlu, C., & Verep, B. The stock parameter of anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) population on the coasts of the Eastern Black Sea: Reason and implications in declining of anchovy population during the 2004-2005 and 2005–2006 fishing seasons. Fresenius Enviro. Bull. 2008, 17(12b). 2159-2169.

- FAO (2022). Fisheries Statistics, Rome, Italy. https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/aqspecies/2106/en.

- Šimat, V. , & Trumbić, Ž. Viability of Anisakis spp. larvae after direct exposure to different processing media and non-thermal processing in anchovy fillets. Fishes, 2019, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FISHBASE (2021). http://www.fishbase.org/search.php (accessed 16.09. 2021.

- TUIK (2024). Turkish Statistical Institute, State Fisheries Statistics. Turkey: TUIK. Retrieved from http://www.tuik.gov.tr (accessed 15.03. 2024.

- Özden, Ö. , Erkan, N. , Metin, S., & Baygar, T. Einfluss von größe und fangzeit auf das fettsäuremuster von sardellen. Fish als Lebensmittel. Informationen für die Fischwirtschaft aus der Fischereiforschung. 2020, 47, 150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatanos, S. , & Laskaridis, K. Seasonal variation in the fatty acid composition of three Mediterranean fish – sardine (Sardina pilchardus), anchovy (Engraulis encrasicholus) and picarel (Spicara smaris). Food Chem. 2007, 103, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufan, B. , Koral, S. & Köse, S. Changes during fishing season in the fat content and fatty acid profile of edible muscle, liver and gonads of anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) caught in the Turkish Black Sea. Int. J. Food Sci. Techno. 2011, 10, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. (2016). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016). FAO/INFOODS Global Food Composition Database for Fish and Shellfish Version 1.0- uFiSh1.0. Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i6655e/i6655e.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Martinez, A. & Gildberg, A. Autolytic degradation of belly tissue in anchovy (Engraulis encrasicholus). Int. J. Food Sci. Techno, 2007, 23, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, S. Evaluation of seafood safety health hazards for traditional fish products: preventive measures and monitoring issues. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 10, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soerensen, N.K. , & Motta, H. Storage and processing trials with anchovy (Stolephorus spp.) in Mozambique. Proceedings. Expert Consultation on Fish Technology in Africa, FAO, Rome (Italy). 1989, pp. 221–230.

- Montaner, M.I. , & Zugarramurdi, A. Influence of anchovy quality on yield and productivity in salting plants. Journal of Food Quality. 1995, 18, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rello, F. J. , Adroher, F. J., Benítez, R., & Valero, A. The fishing area as a possible indicator of the infection by anisakids in anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) from southwestern Europe. Int. J. Food Microbiol, 2009, 129, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serracca, L. , Battistini, R. , Rossini, I., Carducci, A., Verani, M., Prearo, M. Tomei, L., De Montis, G., & Ercolini, C. Food safety considerations in relation to Anisakis pegreffii in anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) and sardines (Sardina pilchardus) fished off the Ligurian Coast (Cinque Terre National Park, NW Mediterranean). Int. J. Food Microbiol, 2014, 190, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasio, A. , Smaldone, G. , Cacace, D., Marrone, R. Voi, A.L., Santoro, M., Cringoli, G. & Pozio, E. Inactivation of Anisakis pegreffii larvae in anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) by salting and quality assessment of finished product. Food Cont. 2016, 64, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardone, L. , Nucera, D. M., Lodora, L.B., Tinacci, L., Acutis, P.L., Guidi, A. & Armani, A. Anisakis spp. larvae in different kinds of ready to eat products made of anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) sold in Italian supermarkets. Int. J. Food Microbiol, 2018, 268, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffredo, E. , Azzarito, L., Di Taranto, P., Mancini, M.E., Normanno, G., Didonna, A., Faleo, S., Occhiochiuso, G., D’Attoli, L., Pedarra, C., Pinto, P., Cammilleri, G., Graci, S., Sciortino, S., & Costa, A. Prevalence of anisakid parasites in fish collected from Apulia region (Italy) and quantification of nematode larvae in flesh. Int. J. Food Microbiol, 2019, 292:159-170. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alonso, I. , Carballeda-Sangiao, N. , González-Muñoz, M., Navas, A., Arcos, S.C., Mendizábal, A., Cuesta, F., & Careche, M. Freezing kinetic parameters influence allergenic and infective potential of Anisakis simplex L3 present in fish muscle. Food Cont. 2020, 118, 107373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Directive. (2005). L 338/12 EN Official Journal of the European Union. Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32005R2073 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- EFSA (2010). Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Scientific Opinion on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products. EFSA Journal 2010; 8, 1543. Available online: www.efsa.europa.eu. [CrossRef]

- FDA (2020). Fish & Fisheries Products Hazards & Controls Guide. FDA, Office of Seafood 2nd ed. Washington, D.C, 276.

- Weir, E. Sushi, nemotodes and allergies. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 172, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurgisladottir, S. , Ingvarsdottir, H. , Torrissen, O.J., Cardinal, M., & Hafsteinsson, H. Effects of freezing/thawing on the microstructure and the texture of smoked Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Food Res. Int. 2000, 33, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, M. Comparison of physicochemical and sensory changes in fresh and frozen herring (Clupea harrengus L.) during marinating, J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 91, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, M. , Kołakowski, E. , & Felisiak, K. Influence of salt concentration on properties of marinated meat from fresh and frozen herring (Clupea harengus L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romotowska, P.E. , Gudjónsdóttir, M. , Kristinsdóttir, T.B., Karlsdóttir, M.G., Arason, S., Jónsson, Á., & Kristinsson, H.G. Effect of brining and frozen storage on physicochemical properties of well-fed Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) intended for hot smoking and canning. LWT - Food Sci. and Tech. 2016, 72, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AESAN. Report of the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Agency. Food Safety and Nutrition on measures to reduce the risk associated with the presence of Anisakis. 2007, 7 p.

- Deng, J.C. Effect of freezing and frozen storage on salt penetration into fish muscle immersed in brine. J. Food Sci. 1977, 42, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R. , Goncalves, A. & Nunes, M.L. Changes in free amino acids and biogenic amines during ripening of fresh and frozen sardine. J. Food Biochem. 1999, 23, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefánsson, G. , Nielsen, H. H., Skåra, T., Schubring, R., Oehlenschläger, J., Luten, J., Derrick, S., & Gudmundsdóttir, G. Frozen herring as raw material for spice-salting. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzsen, K. , Akse, L., Johansen, A. , Joensen, S., Sørensen, N.K. & Olsen, R.L. Physical and quality attributes of salted cod (Gadus morhua L.) as affected by the state of rigor and freezing prior to salting. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koral, S. , & Köse, S. The effect of using frozen raw material and different salt ratios on the quality changes of dry salted Atlantic bonito (lakerda) at two storage conditions. Food and Health. 2018, 4, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koral, S.; Köse, S.; Pompe, M.; & Kočar, D. ; & Kočar, D. The Effect of Freezing Raw Material on the Quality Changes and Safety of Salted Anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus, Linnaeus, 1758) at Cold Storage Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerina, M.A. , Pangborn, R.V., & Roessler, E.B. Principles of sensory evaluation of food. New York: Academic Press Inc. 9: 1965, ISBN, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Herrero, M.M. , Roig-Sagues, A. X., Lopez-Sabater, E.I., Rodriguez-Jerez, J.J. & Mora-Ventura, M.T. Influence of raw fish quality on some physicochemical and microbial characteristics as related to ripening of salted anchovies (Engraulis encrasicholus L.). J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 2631–2640.http. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaçam, H. , Kutlu, S. , & Köse, S. Effect of salt concentrations and temperature on the quality and shelf-life of brined anchovies. International Journal of Food Sci. and Tech. 2002, 37, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. Sensory assessment score sheets for fish and shell fish. Torry&QIM. Research & Development Department of Seafish, 2010, 58 p.

- Minegishi, Y. , Tsukamasa, Y. , Miake, K., Shimasaki, T., Imai, C., Sugiyama, M.S., & Hinano, H. Water activity and microflora in commercial vacuum-packed smoked salmons. Food Hyg. Safety Sci. 1995, 36, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Method 985.14: Moisture in Meat and Poultry Products in Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC, International; Cunniff, P. (Eds.) AOAC. Official Method 985.14: Moisture in Meat and Poultry Products in Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Cunniff, P., ed., AOAC International, 1995, Arlington, VA.

- Rohani, A.C.; Arup, M.J.; Zahrah, T. (2010). Brining parameters for the processing of smoked river carp (Leptobarbus hoevenii). J. Sci. Food Agri. 2010, 38, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Losikoff, M. Clostridium botulinum concerns. In: D.E. Kramer and L. Brown (eds) International smoked seafood conference proceedings (p. 5-7). 2008, Alaska, USA: Sea Grant.

- Goulas, A.E. , & Kontominos, M. G. Effect of salting and smoking method on the keeping quality of chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus): biochemical and sensory attributes. Food Chem. 2005, 93, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. , Hole, M. , & Hanson, S.W. Assessment of lipid oxidation in Indonesian salted-dried marine catfish (Arius thalassinus). J. Sci. Food and Agri, 1992, 51, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, F.E. , & Paige, D. D. Collaborative study of a method for the determination of trimethylamine nitrogen in fish, J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1971, 54, 725–727. [Google Scholar]

- Köse, S. , Kaklıkkaya, N. , Koral, S., Tufan, B., Buruk, K.C., & Aydın, F. Commercial test kits and the determination of histamine in traditional (ethnic) fish products evaluation against an EU accepted HPLC method. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koral, S. , Tufan, B. , Ščavničar, A., Kočar, D., Pompe, M., & Köse, S. Investigation of the contents of biogenic amines and some food safety parameters of various commercially salted fish products. Food Cont. 2013, 32, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkman, A.K. Merck Gıda Mikrobiyolojisi Uygulamaları, Başak Matbaacılık Ltd. Şti., 2005, Ankara, Turkey, 358p.

- Salfinger, Y. , & Tortorello, M. L. Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods. 5th Edition. Washington, USA, American Public Health Association. 2015, Alpha Press. 676 p. [CrossRef]

- Köse, S. Investigation into toxins and pathogens implicated in fish meal production. PhD Thesis. 1993, Loughborough University of Technology. UK.

- Niven, C.F. Jr. , Jeffrey, M. B., & Corlett, D.A. Jr. Different plating medium for quantitative detection of histamine-producing bacteria. Appl. Envir. Micro. 1981, 41, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürgün, V. , & Halkman, A.K. Mikrobiyolojide Sayım Yöntemleri, Gıda Teknolojisi Derneği, No:7, 1990, Ankara, Turkey, 146p.

- Sokal, R.R. , & Rohlf, F.J. Introduction to biostatistics. 2nd ed., New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. 9: 1987, ISBN, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yapar, A. Üç farklı tuz konsantrasyonu kullanılarak hazırlanan tuzlanmis hamsi (Engraulis encrasicolus)’lerde kalite değisimi. Turk J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 1999, 23, 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Besteiro, I. , Rodrígues, C. Selection of attributes for the sensory evaluation of anchovies during the ripening process. J. Sens. Stud. 15, 65–77. [CrossRef]

- Czerner, M. , & Yeannes, M. I. Bacterial contribution to salted anchovy (Engraulis anchoita Hubbs & Marinni, 1935) ripening process. Journal of Aquatic Food Prodt. Tech. 2014, 23, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, H.H. Fresh fish quality and quality changes. Danish International Development Agency, Rome: FAO. 1988, 43-45 pp.

- Besteiro, I. , Rodrígues, C. Chymotrypsin and general proteolytic activities in muscle of Engraulis encrasicolus and Engraulis anchoita during the ripening process. Eur. Food Res. Techno. 210, 414–418. [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, C.E. , Filsinger, B. E., Yeannes, M.I., & Soule, C.L. Shelf life of brine refrigerated anchovies (Engraulis anchoita) for canning. J. Food Sci. 1984, 49, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Directive. Commission Regulation (EU) No 1019/2013 of 23 October 2013 Amending Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 as Regards Histamine. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/%20PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1019& from=EN (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Huss, H.H. Post mortem changes in fish. Quality and Quality Changes in Fresh Fish. FAO, Rome: 1995, 35-92.

- Massa, A.E. , Manca, E. , & Yeannes, M.I. Development of quality index method for anchovy (Engraulis anchoita) stored in ice: Assessment of its shelf-life by chemical and sensory methods. Food Sci. Tech. Int. 2012, 18, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, L. , & Huss, H. H. Microbiological Spoilage of Fish and Fish Products. Int. J. Food Micro. 1996, 33, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.J. Control of Fish Quality. Fishing News Books, a Division of Blackweel Science Ltd. 1995, 245p.

- Siriskar, D.S. & Khedkar, G. D., & Lior, D. Production of salted and pressed anchovies (Stolephorus sp.) and its quality evaluation during storage. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2013, 50, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Jerez, J.J. , Lopez-Sabater, E. I., Roig-Sagues, A.X., & Mora-Ventura, M.T. Evolution of histidine decarboxylase bacterial groups during the Ripening of Spanish Semi-Preserved Anchovies. J. Vet. Med. Seri. B, 1993, 40, 8, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMSF. Microorganisms in Food in: Sampling for Microbiological Analysis, ed: ICMSF, 1992, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada.

- Mohamed, S.B. , Mendes, R. , Slama, R.B., Oliveira, P., Silva, H.A., & Bakhrouf, A. Changes in bacterial counts and biogenic amines during the ripening of salted anchovy (Engraulis encrasicholus). J. Food Nut. Res. 2016, 4, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte, M. , Blaiotta, G. , Francesca, N., & Moschetti, G. Could halophilic archaea improve the traditional salted anchovies (Engraulis encrasicholus) safety and quality? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 51, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonzo, A. , Randazzo, W. , Barbera, M., Sannino, C., Corona, O., Settanni, L., Moschetti, G., Santulli, A., & Francesca, N. Effect of salt concentration and extremely halophilic archaea on the safety and quality characteristics of traditional salted anchovies. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2017, 26, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeannes, M.I. , Ameztoy, I. M., Ramirez, E.E., & Felix, M.M. Culture alternative medium for the growth of extreme halophilic bacteria in fish products. Food Sci. Technol (Campinas). 2011, 31, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodtong, S. , Nawong, S. & Yongsawatdigul, J. Histamine accumulation and histamine-forming bacteria in Indian anchovy (Stolephorus indicus). Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 5, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Sánchez-Cascado, S. Veciana-Nogues, M. T., Bover-Cid, S., Marine-Font, A., & Vidal-Carou, M.C. Volatile and biogenic amines, microbiological counts, and bacterial amino acid decarboxylase activity throughout the salt-ripening process of anchovies (Engraulis encrasicholus). J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Jerez, J.J. , Lopez-Sabater, E. I., Roig-Sagues, A.X., & Mora-Ventura, M.T. Evolution of histidine decarboxylase bacterial groups during the Ripening of Spanish Semi-Preserved Anchovies. J. Vet. Med. Series B, 1993, 40, 8, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapingkae, W. , Tanasupawat, S. Parkin, K.L., Benjakul, S., & Visessanguan, W. Degradation of histamine by extremely halophilic archaea isolated from high salt-fermented fishery products. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2010, 46, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana-Nogués, M.T. , Mariné-Font, A. , & Vidal-Carou, M.C. (1997). Changes in biogenic amines during the storage of Mediterranean anchovies immersed in oil. J Agric Food Chem. 1997, 45, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana-Nogués, Albala-Hurtado, S. , M.T., Mariné-Font, A., & Vidal-Carou, M.C. Changes in biogenic amines during the manufacture and storage of semipreserved anchovies. J. Food Prot. 1996, 9, 1218–1222. [CrossRef]

- Veciana-Nogués, M.T. , Vidal-Carou, M. C., & Mariné-Font, A. Histamine and tyramine during storage and spoilage of anchovies, Engraulis encrasicholus: relationships with other fish spoilage indicators. J. Food Sci. 2006, 55, 1192–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. RASFF Portal. 2020, Available online:. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/rasff-window/portal/?event=searchResultList&StartRow=1 (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- European Commission. RASFF Portal. 2022, Available online:. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/rasff-window/portal/?event=searchResultList&StartRow=1 (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Rodriguez-Jerez, J.J. , Lopez-Sabater, E. I., Hernandez-Herrero, M.M., & Mora-Ventura, M.T. Histamine, putrescine and cadaverine formation in Spanish salted semipreserved anchovies as affected by time/temperature, J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 993–997. [Google Scholar]

- Kočar, D. , Köse, S. , Koral, S., Tufan, B., Ščavničar, A., & Pompe, M. Analysis of biogenic amines using immunoassays, HPLC, and a newly developed IC-MS/MS technique in fish products-A comparative study. Molecules. 2021, 26, 6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaut, A. , Himber, C. , Mulak, V., Grard, T., Krzewinski, F., Le Fur, B., & Duflos, G. Evolution of volatile compounds and biogenic amines throughout the shelf-life of marinated and salted anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus). J. Agri. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8014–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The changes in the organoleptic analysis values of salted and brined anchovies prepared from fresh and previously frozen/thawed raw materials during ambient storage. n: 3, DS: Dry salted anchovies, W: Week, M: Month, a: Appearance scores of control group, b: Appearance scores of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), c: Odour scores of control group, d: Odour scores of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), e: Texture scores of control group, f: Texture scores of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), g: Overall Sensory Scores results of control group, h: Overall Sensory Scores results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group).

Figure 1.

The changes in the organoleptic analysis values of salted and brined anchovies prepared from fresh and previously frozen/thawed raw materials during ambient storage. n: 3, DS: Dry salted anchovies, W: Week, M: Month, a: Appearance scores of control group, b: Appearance scores of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), c: Odour scores of control group, d: Odour scores of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), e: Texture scores of control group, f: Texture scores of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), g: Overall Sensory Scores results of control group, h: Overall Sensory Scores results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group).

Figure 2.

Moisture, pH, aw, salt (%) and WPS (%) results of salted/brined anchovies during ambient storage. n: 3, WPS: Water Phase Salt. a: Moisture results of control group, b: Moisture results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), c: pH results of control group, d: pH results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group), e: aw results of control group, f: aw results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), g: Salt (%) results of control group, h: Salt (%) results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), i: WPS (%) results of control (C) group, j: WPS (%) results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group).

Figure 2.

Moisture, pH, aw, salt (%) and WPS (%) results of salted/brined anchovies during ambient storage. n: 3, WPS: Water Phase Salt. a: Moisture results of control group, b: Moisture results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), c: pH results of control group, d: pH results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group), e: aw results of control group, f: aw results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), g: Salt (%) results of control group, h: Salt (%) results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group), i: WPS (%) results of control (C) group, j: WPS (%) results of prepared from frozen material (experimental group).

Figure 3.

The changes in the TVB-N, TBA and TMA of salted/brined anchovies prepared from fresh raw material (control group) in comparison to frozen/thawed raw material (experimental group) during ambient storage. n: 3, TVB-N: Total Volatile Base-Nitrogen, TBA: Thiobarbituric acid, TMA: trimethylamine. DS: Dry salted. MA: Malonaldehyde, a: TVB-N results of control group, b: TVB-N results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group), c: TBA results of control group, d: TBA results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group), e: TMA results of control group, f: TMA results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group).

Figure 3.

The changes in the TVB-N, TBA and TMA of salted/brined anchovies prepared from fresh raw material (control group) in comparison to frozen/thawed raw material (experimental group) during ambient storage. n: 3, TVB-N: Total Volatile Base-Nitrogen, TBA: Thiobarbituric acid, TMA: trimethylamine. DS: Dry salted. MA: Malonaldehyde, a: TVB-N results of control group, b: TVB-N results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group), c: TBA results of control group, d: TBA results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group), e: TMA results of control group, f: TMA results of prepared from frozen material (Experimental group).

Table 1.

Correlation results among the values of salt %, moisture % and water activity for the control and experimental groups during storage of refrigerator (4±1°C).

Table 1.

Correlation results among the values of salt %, moisture % and water activity for the control and experimental groups during storage of refrigerator (4±1°C).

| Sample Type |

Salt% – aw

|

Salt%- Moisture% |

Moisture% - aw

|

| C |

FM |

C |

FM |

C |

FM |

| 15 % |

R2=0.94 |

R2 = 0.68 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.76 |

R2=0.92 |

R2 = 0.98 |

| 20 % |

R2=0.97 |

R2 = 0.93 |

R2=0.91 |

R2 = 0.75 |

R2=0.88 |

R2 = 0.82 |

| 25 % |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.58 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.49 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.97 |

| 30 % |

R2=0.98 |

R2 = 0.74 |

R2=0.96 |

R2 = 0.81 |

R2=0.98 |

R2 = 0.96 |

| DS |

R2=0.98 |

R2 = 0.98 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.96 |

R2=0.94 |

R2 = 0.97 |

Table 2.

Correlation results between sensory values and the values of TVB-N, TBA and TMA in the control and experimental groups during storage of ambient temperature.

Table 2.

Correlation results between sensory values and the values of TVB-N, TBA and TMA in the control and experimental groups during storage of ambient temperature.

| Sample Type |

TVB-N – Sensory |

TBA- Sensory |

TMA- Sensory |

| C |

FM |

C |

FM |

C |

FM |

| 15 % |

R2=0.87 |

R2 = 0.86 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.91 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.88 |

| 20 % |

R2=0.95 |

R2 = 0.95 |

R2=0.97 |

R2 = 0.96 |

R2=0.97 |

R2 = 0.92 |

| 25 % |

R2=0.92 |

R2 = 0.98 |

R2=0.96 |

R2 = 0.91 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.95 |

| 30 % |

R2=0.98 |

R2 = 0.90 |

R2=0.97 |

R2 = 0.98 |

R2=0.97 |

R2 = 0.98 |

| DS |

R2=0.94 |

R2 = 0.99 |

R2=0.99 |

R2 = 0.94 |

R2=0.98 |

R2 = 0.95 |

Table 3.

The changes in the bacteria counts of salted/brined anchovies prepared from fresh raw material (the control group) in comparison to frozen/thawed raw material (the experimental group) during the ambient storage.

Table 3.

The changes in the bacteria counts of salted/brined anchovies prepared from fresh raw material (the control group) in comparison to frozen/thawed raw material (the experimental group) during the ambient storage.

Storage

Time |

Salt

Concentration |

Sample

Type |

Microbial Counts (log CFU/g) |

| TVAMB |

HB |

HFB |

| 1 Week |

10 % |

C |

7.21±0.28A,1

|

2.94±0.30A,1

|

5.88±0.18A,1

|

| FM |

7.89±0.34A,2

|

3.12±0.24A,1

|

6.38±0.34A,2

|

| 15 % |

C |

3.98±0.14B,1

|

2.26±0.08B,1

|

3.34±0.10B,1

|

| FM |

5.88±0.22a,B,2

|

3.10±0.12a,A,2

|

3.96±0.32a,B,2

|

| 20 % |

C |

3.12±0.08a,C,1

|

2.08±0.16a,B,1

|

2.68±0.06a,C,1

|

| FM |

5.49±0.22a,C,2

|

2.38±0.24a,B,1

|

2.96±0.16a,C,2

|

| 25 % |

C |

2.50±0.10a,D,1

|

<1.47 |

1.86±0.10a,D,1

|

| FM |

3.00±0.18a,D,2

|

2.12±0.12a,B

|

2.38±0.14a,D,2

|

| 30 % |

C |

2.38±0.14a,D,1

|

<1.47 |

1.56±0.14a,D,1

|

| FM |

2.47±0.10a,E,1

|

2.18±0.16a,B

|

1.98±0.08a,E,2

|

| DS |

C |

2.36±0.06D,1

|

<1.47 |

<1.47 |

| FM |

2.39±0.12E,1

|

<1.47 |

<1.47 |

| 1 Month |

15 % |

FM |

6.32±0.28b,A

|

6.26±0.36b,A

|

6.36±0.30b,A

|

| 20 % |

C |

5.36±0.14b,A,1

|

5.77±0.08b,A,1

|

4.82±0.18b,A,1

|

| FM |

6.20±0.34b,B,2

|

6.28±0.28b,A,2

|

6.32±0.30b,A,2

|

| 25 % |

C |

3.36±0.20b,B,1

|

3.27±0.18a,B,1

|

2.18±0.09b,B,1

|

| FM |

5.99±0.28b,B,2

|

6.07±0.34b,A,2

|

6.12±0.18b,A,2

|

| 30 % |

C |

2.68±0.12b,C,1

|

2.26±0.10a,C,1

|

2.14±0.09b,B,1

|

| FM |

3.12±0.20b,C,2

|

2.90±0.18b,B,2

|

2.68±0.12b,B,2

|

| DS |

C |

<1.47 |

<1.47 |

<1.47 |

| FM |

<1.47 |

<1.47 |

<1.47 |

| 2 Month |

20 % |

FM |

7.39±0.34c,A

|

6.98±0.28c,A

|

7.27±0.40c,A

|

| 25 % |

C |

4.36±0.12c,A,1

|

3.86±0.16b,A,1

|

3.86±0.16c,A,1

|

| FM |

5.20±0.26c,B,2

|

5.32±0.30c,B,2

|

5.02±0.22c,B,2

|

| 30 % |

C |

3.02±0.15c,B,1

|

2.56±0.16b,B,1

|

2.56±0.16c,B,1

|

| FM |

3.47±0.18c,C,2

|

3.12±0.12b,C,2

|

3.06±0.20c,C,2

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

<1.47 |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 3 Month |

25 % |

FM |

5.43±0.20c,A

|

5.64±0.24c,A

|

5.60±0.22c,A

|

| 30 % |

C |

3.46±0.14d,1

|

3.10±0.08c,1

|

2.86±0.14c,1

|

| FM |

3.87±0.18d,B,1

|

3.39±0.22b,B,1

|

3.28±0.26c,B,2

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 4 Month |

25 % |

FM |

6.23±0.24b,A

|

7.14±0.30d,A

|

6.20±0.28b,A

|

| 30 % |

C |

3.86±0.16e,1

|

3.22±0.16c,1

|

3.14±0.26c,1

|

| FM |

4.17±0.12d,B,2

|

3.80±0.20c,B,2

|

3.66±0.24c,B,2

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 5 Month |

30 % |

C |

4.17±0.15f,1

|

3.78±0.18d,1

|

3.46±0.07d,1

|

| FM |

4.87±0.26e,2

|

4.39±0.30d,2

|

4.66±0.28d,2

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 6 Month |

30 % |

C |

4.86±0.22g,1

|

3.96±0.12d,1

|

3.76±010e,1

|

| FM |

5.04±0.28e,1

|

4.60±0.20d,2

|

4.30±0.32d,2

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 7 Month |

30 % |

FM |

5.34±0.20e

|

5.25±0.18e

|

5.11±0.24e

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 8 Month |

30 % |

FM |

5.68±0.28f

|

5.47±0.30e

|

5.69±0.26f

|

| DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 9 Month |

DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 10 Month |

DS |

C |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 11 Month |

DS |

FM |

NO |

NO |

NO |

Table 4.

The changes in the biogenic amines of salted/brined anchovies prepared from fresh raw material (control group) in comparison to frozen/thawed raw material (experimental group) during the ambient temperature.

Table 4.

The changes in the biogenic amines of salted/brined anchovies prepared from fresh raw material (control group) in comparison to frozen/thawed raw material (experimental group) during the ambient temperature.

Str.

Time |

Salt

Cons. |

Sam.

Type |

Biogenic Amines (ppm) |

| Tryptamine |

Phenylethylamine |

Putrescine |

Cadaverine |

Histamine |

Tryamine |

Spermidine |

Spermine |

| 2nd Week |

10% |

C |

14.12±1.46A,1

|

46.18±1.72A,1

|

448.76±6.04A,1

|

516.18±18.56A,1

|

192.42±4.55A,1

|

502.12±18.38A,1

|

11.68±1.08A,1

|

<0.71 |

| FM |

7.79±0.25A,2

|

41.01±3.22A,2

|

462.80±19.24A,1

|

587.41±26.80A,2

|

195.56±0.70A,1

|

521.98±23.98A,1

|

9.78±0.48A,2

|

<0.71 |

| 15% |

C |

8.98±0.30a,B,1

|

6.14±0.42a,B,1

|

41.17±1.58a,B,1

|

146.12±4.20a,B,1

|

154.16±2.56a,B,1

|

118.16±2.58a,B,1

|

16.98±0.48a,B,1

|

1.58±0.14a,A,1

|

| FM |

8.29±1.68a,A,1

|

5.54±1.22a,B,1

|

44.59±1.19a,B,1

|

157.92±3.66a,B,1

|

162.56±0.80a,B,2

|

106.57±1.29a,B,2

|

16.59±1.29a,B,1

|

1.76±0.06a,A,1

|

| 20% |

C |

5.78±0.09a,C,1

|

3.68±0.10a,C,1

|

34.16±1.68a,C,1

|

141.30±0.40a,B,1

|

8.38±0.22a,C,1

|

82.62±0.94a,C,1

|

20.14±0.76a,C,1

|

1.84±0.16a,A,1

|

| FM |

6.35±0.19a,B,2

|

3.95±0.13a,C,2

|

37.10±0.60a,C,2

|

152.19±0.33a,B,2

|

7.84±0.40a,C,2

|

85.42±1.94a,C,1

|

21.74±1.17a,C,1

|

1.95±0.31a,B,1

|

| 25% |

C |

5.46±0.35a,C,1

|

5.88±0.15a,B,1

|

5.84±0.26a,D,1

|

34.12±0.68a,C,1

|

5.18±0.20a,D,1

|

66.34±1.45a,D,1

|

21.35±0.78a,C,1

|

1.80±0.14a,A,1

|

| FM |

5.62±0.24a,C,1

|

5.42±0.65a,B,1

|