1. Introduction

Large-mouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) is one of the important commercial fish species and is popular due to its high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids especially EPA and DHA, also the delicate texture and excellent taste. In recent years, the growth rate of large-mouth bass yield was one of the highest among all the freshwater fish species in China[

1]. Freezing is one of the most common storage methods for fish and fish products. However, freezing of muscle foods can lead to a series of physicochemical changes such as formation of ice crystals and the ice-water interface, concentrating of pro-oxidants, altered pH and ionic strength, etc.[

2]. Although frozen storage of muscle foods is a common practice, new insights into the mechanism of freeze-induced damage are still emerging[

3,

4]. Many studies have shown that different freezing rates and frozen storage temperatures have significant effect on fish quality indicators, including texture, water-holding, flavor, etc.[

5,

6]. However, it is often difficult to distinguish the individual contribution of freezing rate and storage temperatures to specific quality indicators.

Among the quality deterioration in frozen muscle, lipid oxidation is of particular importance. The large-mouth bass is generally prepared by steaming as the original taste and odor is favored by consumers. Therefore, extensive off-flavor in this kind of fish is especially unacceptable. Oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and subsequent decomposition of lipid oxidation products can produce volatiles which lead to fishy odor[

7]. Traditionally, the oxidation of lipids has been followed by measuring TBARS and PV values. Volatiles generated from oxidizing fatty acids, such as hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, acids, etc. have been widely used to assess the extent of lipid oxidation[

8]. Volatile compounds of meat are very complex and the identification/quantification requires powerful instruments. As pointed out by Dunkel et al.[

9], a total number of 10000 volatiles was predicted to occur in foods, and omitting just one key odorant will induce significant deviations in perception of aroma. Therefore, the analytical coverage of the chemical odor space of food needs to be comprehensive. In recent years, two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC) has been applied in the analysis of food flavor

[10-12]. Its high resolution may allow the separation of target compounds from matrix interferences or coeluted substances[

13].

The aim of this study was to classify the individual contribution of freezing rate and frozen storage temperature on selected quality indicators of frozen/thawed large-mouth bass, with a focus on volatiles related to lipid oxidation revealed by GC×GC-TOFMS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

Fresh large-mouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) were purchased from a local supermarket during August. Those fish were stunned at head with a wooden stick, and followed by the removal of scales and internal organs. The fish buried in crushed ice were transported to the lab within half an hour. Upon arrival, each fish was rinsed under tap water and their weight was recorded (weight: 405 ± 34 g). The dorsal muscle was taken out and cut into fillets of 5 cm * 3.5 cm. The fillets were divided into 5 groups and subjected to different freezing/frozen storage treatments. Each fillet was frozen by cold air in freezer till the center of fillet reached a temperature of -18 °C (monitored by a K-type thermocouple), and then the fillet was transferred to frozen storage at different temperatures. The treatment was as follows: Group A, Freeze at -18 °C and storage at -18 °C; Group B, Freeze at -60 °C and storage at -18 °C; Group C, Freeze at -60 °C with forced air circulation (wind speed 2 m/s) and storage at -18 °C;Group D, Freeze at -60 °C and storage at -40 °C;Group E, Freeze at -60 °C and storage at -60 °C. The groups were designed to evaluate the effects of different freezing rates (Groups A/B/C) and different frozen storage temperatures (Groups B/D/E). Temperature of the freezers during frozen storage were recorded by a K-type thermocouple (Uni-Trend Technology, Dongguan, China). After frozen storage for 30 and 90 days, the fillets were sampled for physiochemical analysis. Fresh fillets were used as control.

2.2. Water-Holding Capacity

Water-holding capacity was evaluated by thaw loss and centrifugation loss. Frozen fillets were thawed at room temperature. Each frozen fillet and the corresponding thawed fillet were weighed and recorded as M1, M2, respectively. The thaw loss was calculated by the formula: Thaw loss (%) = (M1-M2)/M1 * 100. For centrifugation loss, myofibrils were extracted from thawed fillet and the water-holding capacity of myofibrils was determined as described by Ji et al.[

14].

2.3. Lipid Oxidation

Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance (TBARS) test was used to estimate the degree of lipid oxidation based on Bao et al.[

15] with some modifications. Briefly, minced fish muscle (5 g) was homogenized (IKA T18 Ultra-Turrax, Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany) with 20 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid at a speed of 14000 rpm for 20 s, and then the mixture was filtered through double layers of filter paper. An aliquot of 5 mL filtrate was mixed with 5 mL thiobarbituric acid (20 mM) and incubated in a 90 °C water-bath for 30 min. After cooling to room temperature, the absorbance at 532 nm was measured. Tetraethoxypropane was used as the standard because it forms equal moles of malonaldehyde (MDA) during heating in acid conditions. TBARS values were expressed as mg MDA / kg meat.

2.4. Total Volatile Basic Nitrogen (TVB-N)

TVB-N values were estimated according to the current Chinese standard method (method III, micro diffusion) for determination of TVB-N in foods (GB5009.228-2016). Briefly, minced fish muscle (5 g) was homogenized (13500 rpm, 20 s) with 25 mL cold distilled water, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min followed by filtration. An aliquot of 1 mL filtrate was added to the outer chamber of a micro-diffusion dish (Supplementary File 1,

Figure 1), and 1 mL of boric acid (20 g/L) with methyl red-bromocresol green mixed indicator was added to the inner chamber of the diffusion dish. After addition of 1 mL of saturated K2CO3 solution to mix with the filtrate, the diffusion dish was sealed and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. And then the boric acid solution in the inner chamber was titrated with 0.01 M HCl, the TVB-N value was expressed as mg nitrogen/100 g muscle.

2.5. Protein Oxidation and Denaturation

Surface hydrophobicity of myofibrils was used as indicator of protein denaturation. It was evaluated based on the method proposed by Chelh et al.[

16]. This method was based on the interaction of the hydrophobic chromophore bromophenol blue (BPB) with myofibrillar proteins, and the separation of free and bound BPB. Some modifications were made as described in Ji et al.[

14]. Protein oxidation was indicated by loss of free thiol groups and the free thiol content of fish meat was determined according to Bao et al.[

15].

2.6. Freeze Substitution Histological Observation

Prior to analysis, meat samples were kept at -18 ℃ overnight and then cut into small cubes (5 × 5 × 3 mm3). The unthawed meat cubes were fixed in Carnoy solution (60% thanol, 30% chloroform, and 10% acetic acid) at -18 ℃ overnight. After fixation, the samples were dehydrated at 4 ℃ with a graded series of ethanol solutions (70-90% in 5% increments). And then the samples were further processed as described in Bao et al.[

17] until micrographs were taken by a light microscope (DM 2000, Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH)

2.7. Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (GC×GC-TOFMS)

Samples from fresh and thawed fillets (4 samples per group) were subjected to GCGC-TOFMS analysis. Two grams of minced meat was mixed with 10 L of internal standard (1,2-dichlorobenzene, 50 mg/L) and transferred to a 20 mL glass GC vial. The instrumental conditions were set up according to Wang et al. (2020b). Briefly, a Pegasus® 4D GC×GC-TOFMS system (LECO Corp., St. Joseph, MI, USA) equipped with an Agilent 7890B GC, a secondary oven, and a dual-stage quad-jet thermal modulator was used. A 60 m 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm DB-FFAP (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used as the first dimensional column, and a 1.5 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm Rxi-17Sil MS (Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was used as the second column. The initial oven temperature was 45℃ and kept for 3 min, raised to 150℃ at 4℃/min and held for 2 min, then ramped at 6℃/min to 200℃ and at 10℃/min to 230℃ for 20 min. The modulation period of 4 s and hot pulse of 0.80 s was performed. The second oven was kept 5℃ higher than the first oven. The electron energy of TOFMS (m/z 35 to m/z 400) was -70 volts, and acquisition rate was 100 spectra/s, ion source and transfer line were 230℃ and 240℃ respectively.

The data was processed with ChromaTOF version 4.61.1.0 software (LECO Corp., St. Joseph, MI, USA). The peaks aligned by the software based on the extracted masses and their retention times (first- and second-dimensional). Identification was done by comparing mass spectra and retention times (first- and second-dimensional) in databases (NIST 2014 and Welly 9). Identified compounds with similarity values larger than 800 were considered, and only the compound presented at least in three replicates was considered reliable.

2.8. Data Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc test using Duncan method (P<0.05) was performed by SPSS 22 statistics package program (IBM Corp., New York, USA). For multi-factor ANOVA, Day 30 & Day 90 samples were used. OPLS-DA analysis of volatiles was performed with MetaboAnalyst 4.0 (

https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). Data processing methods: Data transformation: Cubic Root Transformation; Data scaling: Pareto Scaling. 2D score plot of PLS-DA displayed 95% confidence region.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Freezing Process and Frozen Storage

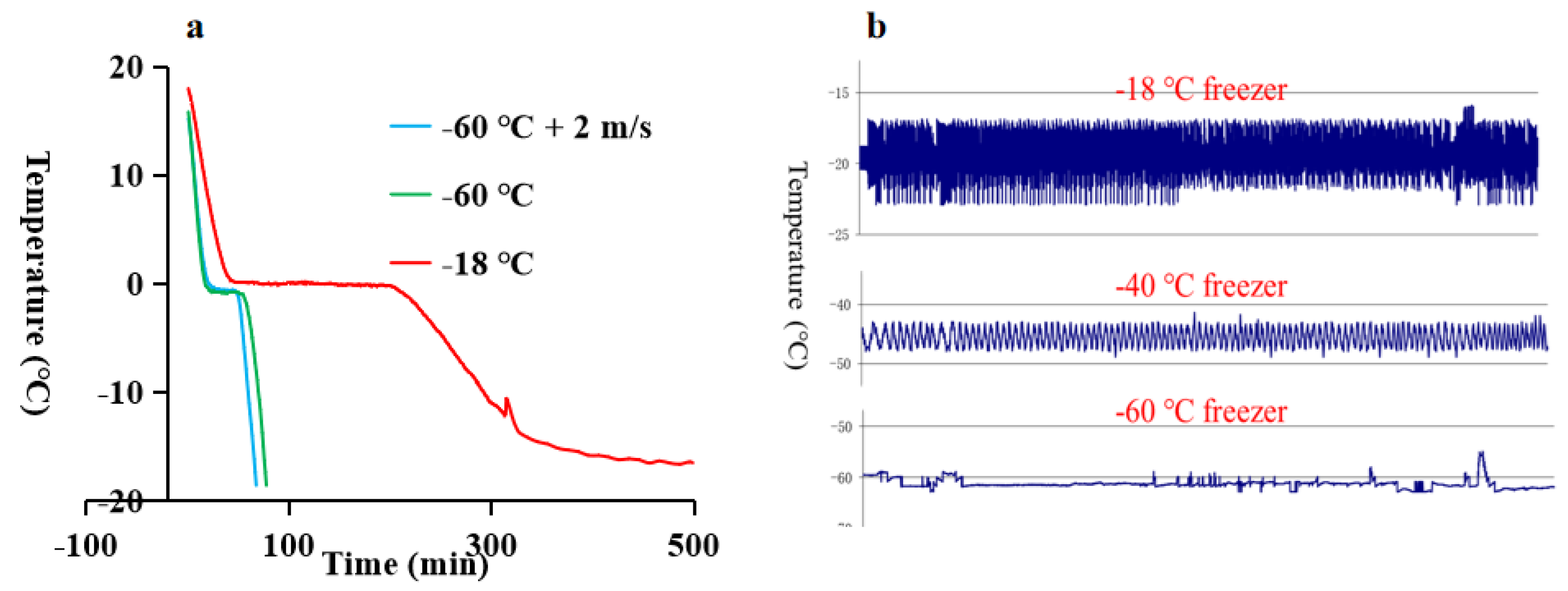

The core temperatures of fillets subjected to different freezing treatments were recorded. As the freezing process started, temperature gradually dropped. And then the temperature reached a plateau, and the temperature corresponding to the plateau was lower when freezing at -60 ℃ as compared to freezing at -18 ℃ (

Figure 1a). Similarly, the phenomenon that faster freezing resulted a relatively lower temperature at the plateau were also observed in the freezing of muscle foods[

14,

18] and other non-muscle food[

19]. This difference may have resulted from different freezing rates. It is well-known that during slow freezing, the formation of ice will release the latent heat of water and thereby against the heat removal by cooling. As a result, the system maintained at a rather constant temperature. When the cooling rate was higher, the heat removal would be greater than the released latent heat, therefore the equilibrium temperature would be lower. At even higher freezing rate, such as freezing with liquid nitrogen, a temperature of plateau is hardly seen. It can be seen that freezing at -60 ℃ was much faster than freezing at -18 ℃. The time needed for the temperature to decrease from -1 ℃ to -5 ℃ (maximal ice formation region) was approximately 47 min when freezing at -18 ℃, while it took 13 min at -60 ℃. The additional forced air circulation at 2 m/s further reduced that time to 7 min. Throughout the storage period, temperatures of the freezers were relatively stable with minor fluctuations (

Figure 1b)

Figure 1.

Core temperature of large-mouth bass fillets during freezing until the center reached -18 °C (a), and typical temperature fluctuations within different freezers over a period of 1 month, temperature was recorded every 15 minutes (b).

Figure 1.

Core temperature of large-mouth bass fillets during freezing until the center reached -18 °C (a), and typical temperature fluctuations within different freezers over a period of 1 month, temperature was recorded every 15 minutes (b).

3.2. Water-Holding

Water-holding is an important quality attribute of muscle foods. Water is distributed in a compartmentalized meat matrix and generally can be grouped into bound water, entrapped or immobilized water, and free water[

20]. There are different methods in the evaluation of water-holding of meat, including filter paper press, drip loss, thaw loss[

21], water-holding of extracted myofibrils[

22], sausage method[

23], etc. In frozen-thawed meat, the water-holding is generally lower than that of fresh meat, especially at a slow freezing rate, and this has been attributed to the formation of larger ice crystals and more severe protein denaturation[

4].

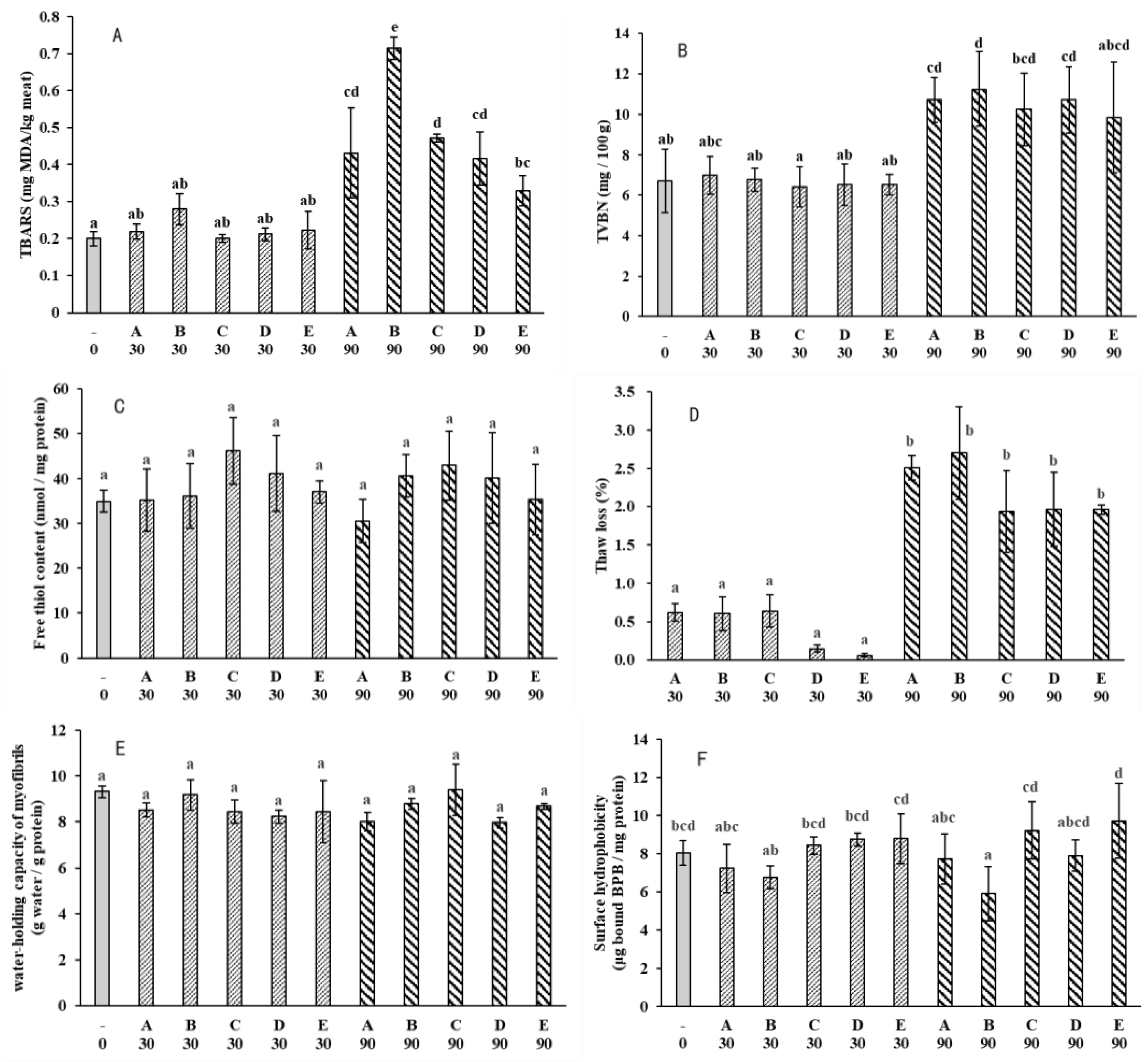

In this study, water-holding was studied by thaw loss and the centrifugation loss of myofibrils. Results showed that only storage time had a significant effect (P < 0.001) on thaw loss (

Table 1). Thaw loss at day 90 was more than doubled as compared to day 30 (

Figure 2D), while the water-holding of myofibrils did not show significant changes throughout the frozen storage (

Figure 2E). This was probably due to the different principles of the two methods. Thaw loss mainly reflect the loss of extracellular water, while the centrifugation loss of myofibrils reflects water loss in the intracellular matrix. The thaw loss of fish fillets was below 3.5%, while the thaw loss of pork or beef was often greater. This could be linked to a higher ultimate pH in fish and higher pH is often associated with better water-holding[

24]. Water-holding had close relationship with meat color, in addition to meat pigments. Disruption of the sarcolemma and the shrinkage of myofibril led to changes in water-holding, and the structural changes would affect the light scattering properties of meat[

25]. Thawed fillets had higher values of L* (lightness) as compared to unfrozen fresh sample (Supplementary File 1,

Figure 2), suggesting reduced water-holding. Different freezing rate or frozen storage temperature did not significantly affect thaw loss, However, there was a trend that lower storage temperature (Group D & E) had lower thaw loss. As for the water-holding of myofibrils, two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant effect of storage temperature and the interaction between freezing rate and storage time (P<0.05). In the current study, only thawing at room temperature was used. It is well-known that different thawing methods would affect water-holding of muscle foods

[26-28].

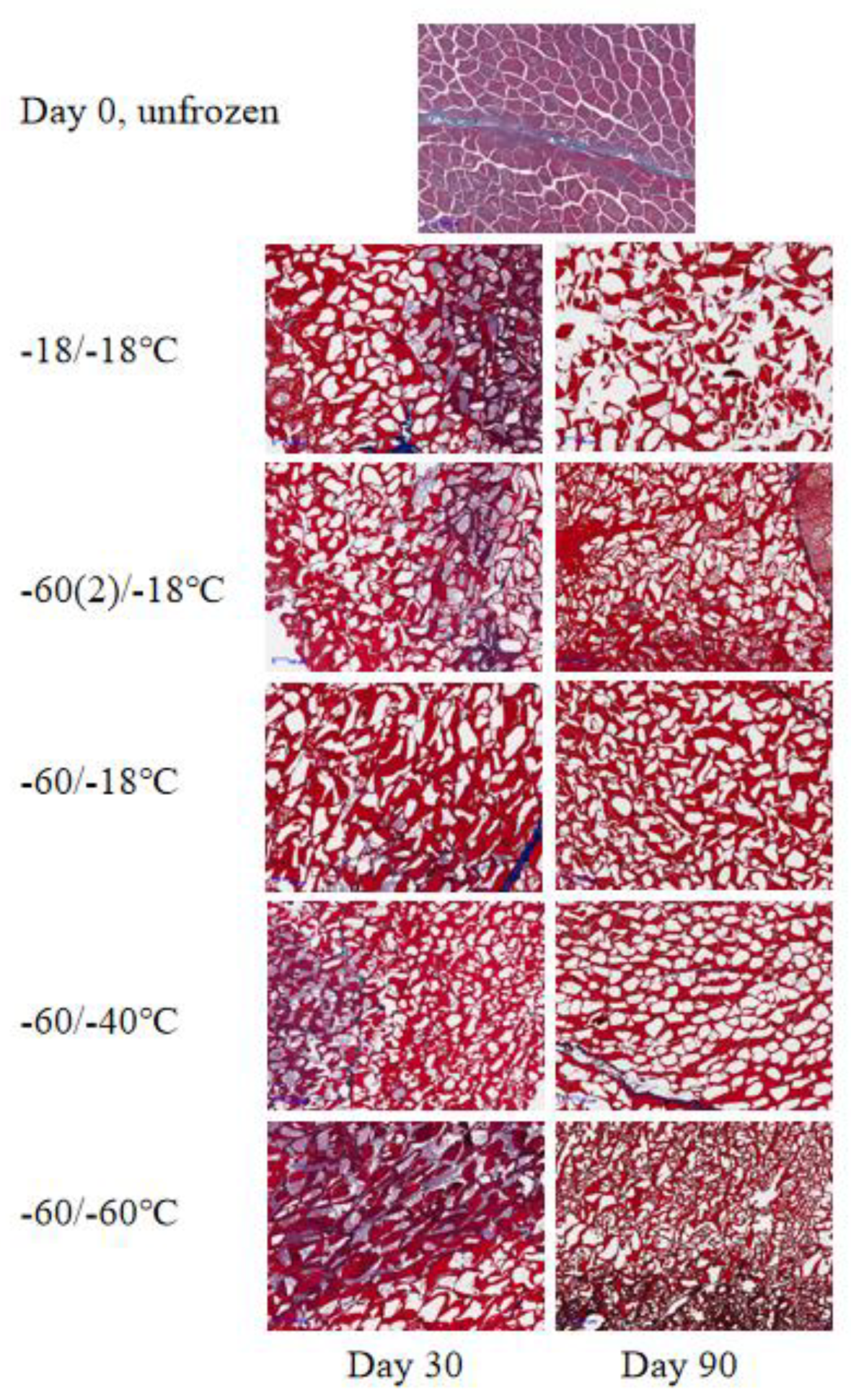

3.3. Microstructure Changes

The combined effects of freezing rates, frozen storage and thawing rates on crystal formation and the ultrastructure of muscle is a complex system[

29]. Upon thawing, the meat structure appeared to have almost completely recovered. In order to observe the ice crystals in the frozen state, Cross-sectional micrograph of fish muscle was obtained via the freeze substitution histological observation (

Figure 3). Unfrozen fresh muscle showed clear perimysium, the myofiber remained intact and the extracellular space was relatively small. Formation of ice-crystals and distortion of myofibers can be observed in all frozen samples. As shown in

Figure 1b, that temperature fluctuation in the -18 ℃ freezer was around ±3 ℃, this temperature fluctuation led to ice recrystallization. Generally, the ice crystals became larger at day 90 as compared to day 30 due to recrystallization during frozen storage. Samples which were frozen at -18 ℃ and stored at -18 ℃ for 90 days displayed the most severe damage to muscle structure. However, the structural damage was comparable to other groups at day 30, suggesting that a relatively long-term frozen storage at -18℃ was more detrimental to muscle structure.

3.4. Lipid Oxidation

Many biochemical reactions in frozen foods are inhibited due to a lower activity of water. However, reactivity of lipid oxidation can be relatively high even at a very low water activity of aw less than 0.1[

30]. Therefore, lipid oxidation can progress to a noticeable extent during long-term frozen storage of meat products. It can be seen that lipid oxidation level in the fillets measured as TBARS was not significantly different after frozen storage of 30 days, regardless of the freezing/storage treatment (

Figure 2A). However, TBARS values all increased at day 90 as compared to day 0 fresh sample. The increase of TABRS in frozen muscle foods with time have been widely reported

[31-34]. The combination of different freezing rates and frozen storage temperatures also had significant effect on TABRS. Among the day 90 samples, fillets that was frozen at -60 ℃ and stored at -18 ℃ (Group B) showed highest TABRS value around 0.7 mg MDA/kg meat, while the lower content in TABRS (Group E) was about half of that value. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed that storage time, freezing rate and frozen storage temperature all had significant effect on TABRS (P < 0.001), and there was significant interaction of freezing rate * storage time, and storage temperature * storage time (P < 0.01) (

Table 1). Similarly, Hou et al.[

32] reported that freezing methods (with different freezing rates) had significant effect on the TBARS value of pork, and there was strong interaction between the freezing rate and storage time. And storage at -80 ℃ for 20 weeks did not increase the TABRS value in beef. Karlsdottir et al.[

35] studied the effects of temperature during frozen storage on lipid deterioration of saithe and hoki muscles, results showed that extended storage time increased lipid deterioration, but lower storage temperature had more preservative effects.

It is known that lipid oxidation generates a range of small molecular compounds including aldehydes, ketones, alcohols and acids, and many of them are volatile[

36]. Baron[

31] concluded that measurement of volatiles is a very sensitive method for measuring the development of lipid oxidation in rainbow trout during frozen storage at different temperatures. In order to study lipid oxidation in more detail, GC×GC-TOFMS was employed to investigate possible products degraded from lipid oxidation, and only the compound presented at least in three replicates was considered reliable. In total, 40 compounds were quantified and presented in Supplementary File 2. In general, the volatile profile may be considered as a chemical fingerprint of food: the nature and relative quantities of compounds in the volatile fraction are distinctive features. Analyzing volatile compounds can be exploited to differentiate fresh fish from frozen-thawed ones. Leduc et al.[

37] compared the volatile compounds both in fresh and frozen-thawed European sea bass, gilthead seabream, cod and salmon, and results showed that dimethyl sulfide, 3-methybutanal, ethyl acetate and 2-methybutanal were suitable differentiation indicators. Zhang et al.[

38] suggested to use volatile profile to evaluate the freshness of different seafood, as a conventional chemical marker, trimethylamine does not always have the high contribution in discrimination.

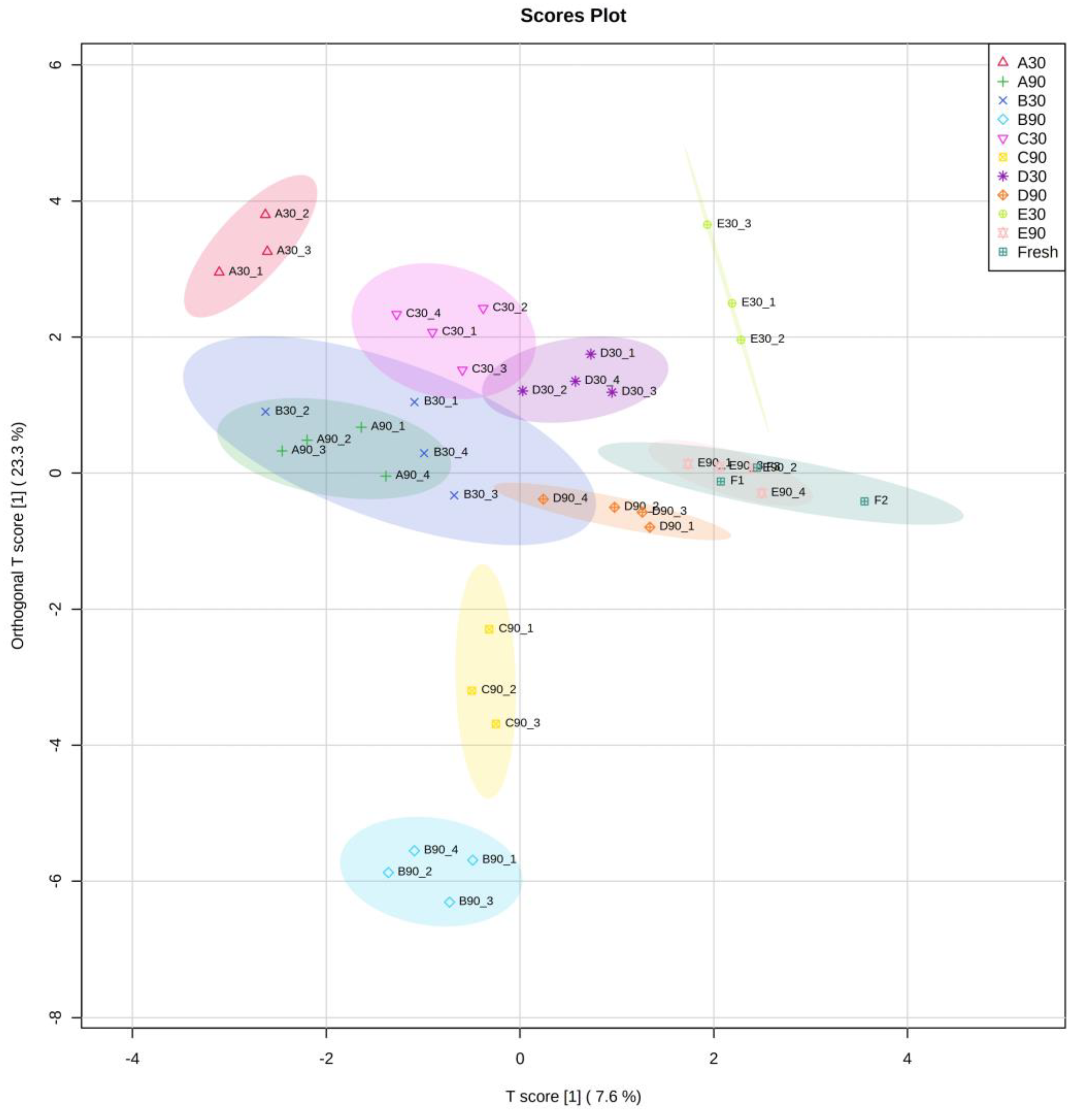

In the present study, a range of aldehydes (2-octenal, 2-nonenal, etc.), ketones (2-undecanone, 2-nonanone, etc.), alcohols (3-octanol, 2-octen-1-ol, etc.), and acids (hexanoic acid, heptanoic acid, etc.) were only presented in frozen-thawed fillets. This likely contributed to our observation that fresh samples were separated from the frozen-thawed ones except for E90 in OPLS-DA (

Figure 4). For samples taken at day 30 and day 90, ANOVA revealed that storage time, storage temperature and the freezing rate before storage all had significant effects on volatile composition (

Table 2). Different volatiles responded to frozen storage conditions differently. Among the 40 quantified compounds, 2-Pentanone, 1-Pentanol, 1-Hexanol, 1-Heptanol, (5Z)-Octa-1,5-dien-3-ol were significantly affected by all three factors; while octanoic acid, 3-phenyl-2-Propenal, n-Decanoic acid, octanal, 6-methyl-5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl-3-Heptanol, nonanal, 2-Octenal, 2-Nonenal were not affected by neither of the three factors. From the OPLS-DA graph (

Figure 4), it can be found that fillets in group D & E were relatively close to fresh fillets in the composition of oxidation-related volatiles, suggesting that frozen storage at temperatures below -40℃ was beneficial in preserving freshness of large-mouth bass in terms of volatiles. Group B had the same freezing rate with groups D & E, but a subsequent frozen storage at -18℃ increased lipid oxidation shown by larger TBARS values at day 90. Therefore, group B clearly separated from groups D & E. In agreement, group B at day 90 had a higher content of oxidation-derived compounds, such as 1-pentanol, 1-octen-3-ol as compared to other treatments. In addition, a range of oxidation-derived compounds were only detected at day 90 in group B, including heptanal, 2-hexenal, 2,4-heptadienal, 4-hepten-1-ol, 2,7-octadien-1-ol, undecanal. Group C had higher freezing rate and it generally separated from groups A & B, indicating that the freezing rate had an impact on lipid degradation as groups A-C shared the same storage temperature. This was in line with the two-way ANOVA results that freezing rate had significant effect on TABRS (P < 0.001). These preliminary results showed that application of GC×GC-TOFMS in the study of frozen fish quality is feasible.

3.5. Protein Changes

Protein denaturation and oxidation are common consequence of frozen-thawed muscle foods, and both phenomena affect frozen-thawed meat quality such as water-holding. Protein denaturation and oxidation are likely to be closely related[

2]. In this study, protein denaturation and oxidation were indicated by increased surface hydrophobicity and loss of free thiols, respectively. In general, there was no marked changes in protein oxidation when evaluated by free thiols (

Figure 2), but two-way ANOVA revealed that freezing rate had significant effect (P < 0.01,

Table 1). Similarly, Hou et al.[

32] reported that free thiols did not change between slow freezing and fast freezing pork, but lipid oxidation was lower in fast freezing samples. In theory, oxidative stress can be transferred between lipids and proteins. In this study, lipid oxidation displayed significant changes between storage time and freezing treatments. Many studies observed increased lipid oxidation in frozen meats together with increased protein oxidation

[39-41]. As for protein denaturation, there was significant changes in surface hydrophobicity of extracted myofibrils among freezing treatments, and both freezing rate and storage temperature exhibited a strong effect (

Table 1). In agreement, Zhang & Ertbjerg[

4] reported that slow freezing led to increased surface hydrophobicity of myofibrils. Qian et al.[

42] found that protein denaturation was generally greater at higher temperatures when beef was frozen stored at temperatures between -1 to -18 ℃. Proteolytic activity may proceed during frozen storage, suggested by an increase of TVB-N with storage time. TVB-N is widely used as an indicator of fish freshness, and results from the degradation of protein and non-protein nitrogenous compounds by microbial and endogenous enzymes. Neither the storage temperature nor the freezing rate had a significant effect on the amount of TVB-N (P > 0.05,

Table 1).

4. Conclusions

The present study found that freezing rate and storage temperature had significant impact on lipid oxidation and protein denaturation in the fillets of large-mouth bass, while protein oxidation was more affected by freezing rate. Water-holding and TVBN were mainly affected by storage time. GC×GC-TOFMS revealed a total of 40 volatile compounds which may derive from lipid oxidation and degradation. OPLS-DA of the detected volatiles showed that fresh samples were separated from the frozen-thawed ones. Volatiles such as 2-octenal, 2-nonenal, 2-undecanone, 2-nonanone, 2-octen-1-ol,hexanoic acid, heptanoic acid were only presented in frozen-thawed fillets. Fillets that were frozen at -60 °C with forced air circulation at 2 m/s generally separated from samples frozen at -18 °C or -60 °C (without forced air circulation), and fillets that were frozen stored at -40 ℃ and -60 ℃ were relatively close to fresh fillets in the composition of oxidation-related volatiles, indicating that a faster freezing rate and storage at temperatures below -40 ℃ was beneficial in preserving freshness of large-mouth bass in terms of volatiles. However, the level of temperature may have some limitations regarding an industrial implementation of these conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Supplementary Figure 1: Illustration of the micro-diffusion dish; Supplementary Figure 2: Lightness (L*) of large-mouth fillet subjected to different freezing/frozen storage treatments. Supplementary File 2: summary of quantified volatiles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yulong Bao; methodology, Yaqi Zhang and Wanjun Xu; formal analysis, Yaqi Zhang and Yulong Bao; investigation, Yaqi Zhang and Wanjun Xu; writing—original draft preparation, Yaqi Zhang.; writing—review and editing, Yulong Bao; supervision, Yulong Bao; funding acquisition, Yulong Bao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2021M701480 and the Senior Talent Program of Jiangsu University, grant number 20JDG062.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M701480). Yulong Bao wishes to acknowledge the financial support from Jiangsu Provincial Double-Innovation Doctor Program (JSSCBS20210932), and the Senior Talent Program of Jiangsu University (20JDG062).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in respect to the work described in this paper.

References

- Fishery Bureau of Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook. Beijing, China: China Agriculture Press, 2021.

- Bao, Y., Ertbjerg, P., Estévez, M., Yuan, L., & Gao, R.. Freezing of meat and aquatic food: Underlying mechanisms and implications on protein oxidation[J]. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2021, 20(6), 5548-5569. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Qian, S., Song, Y., Guo, Y., Huang, F., Han, D., ... & Blecker, C.. New insights into the mechanism of freeze-induced damage based on ice crystal morphology and exudate proteomics[J]. Food Research International, 2022, 161, 111757. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , & Ertbjerg, P.. On the origin of thaw loss: Relationship between freezing rate and protein denaturation[M]. Food Chemistry, 2019, 299, 125104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, N. , & Okazaki, E.. Recent research on factors influencing the quality of frozen seafood[J]. Fisheries Science, 2020, 86, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstorebrov, I. , Eikevik, T. M., & Bantle, M.. Effect of low and ultra-low temperature applications during freezing and frozen storage on quality parameters for fish[J]. International Journal of Refrigeration, 2016, 63, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R. J., & Kinsella, J. E.. Lipoxygenase generation of specific volatile flavor carbonyl compounds in fish tissues[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1989, 37(2), 279-286. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R., Pateiro, M., Gagaoua, M., Barba, F. J., Zhang, W., & Lorenzo, J. M.. A comprehensive review on lipid oxidation in meat and meat products[J]. Antioxidants, 2019, 8(10), 429. [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, A. , Steinhaus, M., Kotthoff, M., Nowak, B., Krautwurst, D., Schieberle, P., & Hofmann, T.. Nature’s chemical signatures in human olfaction: a foodborne perspective for future biotechnology[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2014, 53, 7124–7143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratel, J. , & Engel, E.. Determination of benzenic and halogenated volatile organic compounds in animal-derived food products by one-dimensional and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2009, 1216, 7889–7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. , Feng, X., Zhang, D., Li, B., Sun, B., Tian, H., & Liu, Y.. Analysis of volatile compounds in Chinese dry-cured hams by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography with high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry[J]. Meat Science, 2018, 140, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Zhu, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, X., & Shi, W.. Characteristic volatile compounds in different parts of grass carp by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry[J]. International Journal of Food Properties, 2011, 23, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A. , Khummueng, W., Mercier, F., Kondjoyan, N., Tournayre, P., Meurillon, M.,... Engel, E.. Relevance of two-dimensional gas chromatography and high resolution olfactometry for the parallel determination of heat-induced toxicants and odorants in cooked food[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2015, 1388, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W., Bao, Y., Wang, K., Yin, L. and Zhou, P.. Protein changes in shrimp (Metapenaeus ensis) frozen stored at different temperatures and the relation to water-holding capacity. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2021, 56(8), 3924-3937. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y., & Ertbjerg, P.. Relationship between oxygen concentration, shear force and protein oxidation in modified atmosphere packaged pork[J]. Meat Science, 2015, 110, 174-179. [CrossRef]

- Chelh, I., Gatellier, P., & Santé-Lhoutellier, V. (2006). A simplified procedure for myofibril hydrophobicity determination[J]. Meat Science, 2066, 74(4), 681-683. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y. , Wang, K., Yang, H., Regenstein, J. M., Ertbjerg, P., & Zhou, P.. Protein degradation of black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) muscle during cold storage[J]. Food Chemistry, 2020, 308, 125576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. , & Pan, B. S.. Freezing tilapia by airblast and liquid nitrogen – freezing point and freezing rate[J]. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 1995, 30, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J. , Zhang, L., Yin, L. a., Liu, J., Sun, Z., & Zhou, P. (2021). Changes in bioactive proteins and serum proteome of human milk under different frozen storage[J]. Food Chemistry, 2021, 352, 129436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff-Lonergan, E. , & Lonergan, S. M.. Mechanisms of water-holding capacity of meat: The role of postmortem biochemical and structural changes[J]. Meat Science, 2005, 71, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, R.. Functional properties of the myofibrillar system and their measurements. In P. J. Bechtel (Ed.). Muscle as Food. London, 1986: Academic Press Inc. Food Science and Technology (pp. 135-191).

- Liu, J. , Arner, A., Puolanne, E., & Ertbjerg, P.. On the water-holding of myofibrils: Effect of sarcoplasmic protein denaturation[J]. Meat Science, 2016, 119, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M. , Ventanas, S., Heinonen, M., & Puolanne, E.. Protein carbonylation and water-holding capacity of pork subjected to frozen storage: Effect of muscle type, premincing, and packaging[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59, 5435–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offer, G. , & Knight, P.. Structural basis of water-holding in meat. Part 1: General principles and water uptake in meat processing. London, 1988: Elsevier Applied Science. In R. Lawrie (Ed.), Developments in Meat Science, Vol 4 (pp. 63-171).

- Hughes, J. , Oiseth, S., Purslow, P., & Warner, R.. A structural approach to understanding the interactions between color, water-holding capacity and tenderness[J]. Meat Science, 2014, 98, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L., Wan, J., Li, X., & Li, J.. Effects of different thawing methods on physicochemical properties and structure of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides)[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2020, 85(3), 582-591. [CrossRef]

- Leygonie, C., Britz, T. J., & Hoffman, L. C.. Impact of freezing and thawing on the quality of meat[J]. Meat Science, 2012, 91(2), 93-98. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y., & Xie, J.. Quality of cuttlefish as affected by different thawing methods[J]. International Journal of Food Properties, 2022, 25(1), 33-52. [CrossRef]

- Ngapo, T. M., Babare, I. H., Reynolds, J., & Mawson, R. F.. Freezing rate and frozen storage effects on the ultrastructure of samples of pork[J]. Meat Science, 1999, 53(3), 159-168. [CrossRef]

- Vilgis, T. A. . Soft matter food physics—the physics of food and cooking[J]. Reports on Progress in Physics, 2015, 78, 124602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, C. P. , Kjaersgard, I. V. H., Jessen, F., & Jacobsen, C. (2007). Protein and lipid oxidation during frozen storage of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2007, 55, 8118–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q. , Cheng, Y., Kang, D., Zhang, W., & Zhou, G.. Quality changes of pork during frozen storage: comparison of immersion solution freezing and air blast freezing[J]. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2020, 55, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. , Xiong, Y. L., Kong, B., Huang, X., & Li, J.. Influence of storage temperature and duration on lipid and protein oxidation and flavour changes in frozen pork dumpling filler[J]. Meat Science, 2013, 95, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozen, B. O. , & Soyer, A.. Effect of plant extracts on lipid and protein oxidation of mackerel (Scomber scombrus) mince during frozen storage[J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology-Mysore, 2018, 55, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsdottir, M. G. , Sveinsdottir, K., Kristinsson, H. G., Villot, D., Craft, B. D., & Arason, S.. Effects of temperature during frozen storage on lipid deterioration of saithe (Pollachius virens) and hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae) muscles[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 156, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaich, K.M, Shahidi, F., Zhong, Y., and Eskin, N.A.M.. Lipid Oxidation. In: Biochemistry of Foods, Third Edition, Ed. Eskin, 2013, N.A.M., Elsevier, pp. 419-478.

- Leduc, F., Krzewinski, F., Le Fur, B., N’Guessan, A., Malle, P., Kol, O., & Duflos, G.. Differentiation of fresh and frozen/thawed fish, European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata), cod (Gadus morhua) and salmon (Salmo salar), using volatile compounds by SPME/GC/MS[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2012, 92(12), 2560-2568. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Li, G., Luo, L., & Chen, G.. Study on seafood volatile profile characteristics during storage and its potential use for freshness evaluation by headspace solid phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2010, 659(1-2), 151-158. [CrossRef]

- Pan, N. , Dong, C., Du, X., Kong, B., Sun, J., & Xia, X.. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the quality of quick-frozen pork patty with different fat content by consumer assessment and instrument-based detection[J]. Meat Science, 2021, 172, 108313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utrera, M. , Morcuende, D., Ganhao, R., & Estevez, M.. Role of Phenolics Extracting from Rosa canina L. on Meat Protein Oxidation During Frozen Storage and Beef Patties Processing[J]. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 2015, 8, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y, Qiu, Z, Wang, X. . Protein oxidation and tandem mass tag-based proteomic analysis in the dorsal muscle of farmed obscure pufferfish subjected to multiple freeze–thaw cycles. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2020, 44, e14721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S., Li, X., Wang, H., Mehmood, W., Zhang, C., & Blecker, C.. Effects of frozen storage temperature and duration on changes in physicochemical properties of beef myofibrillar protein[J]. Journal of Food Quality, 2021, 8836749. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).