Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

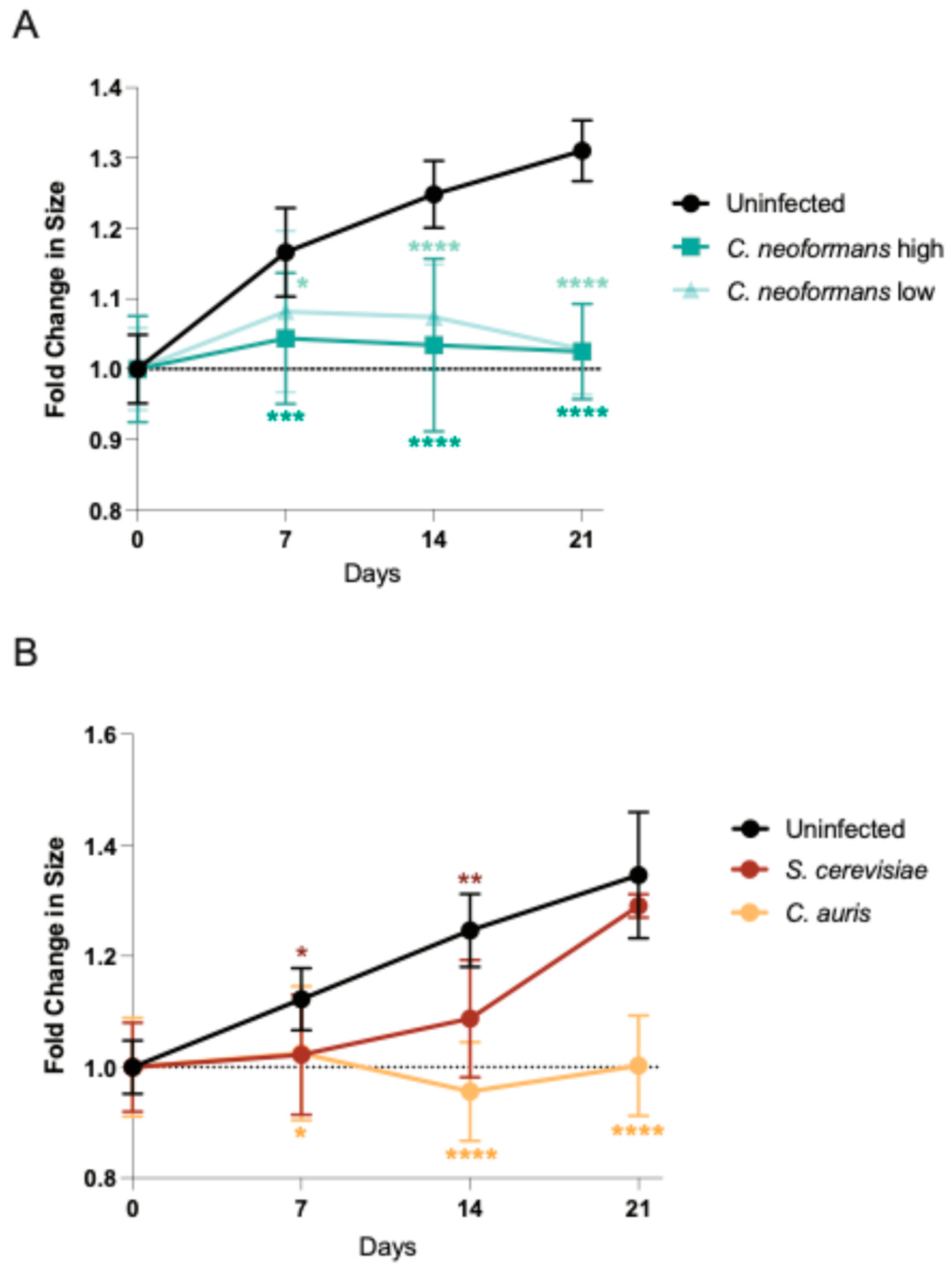

2.1. Organoids Display Growth Defect in Response to Pathogenic Fungi

2.2. C. neoformans Effectively Penetrates Organoid Tissues

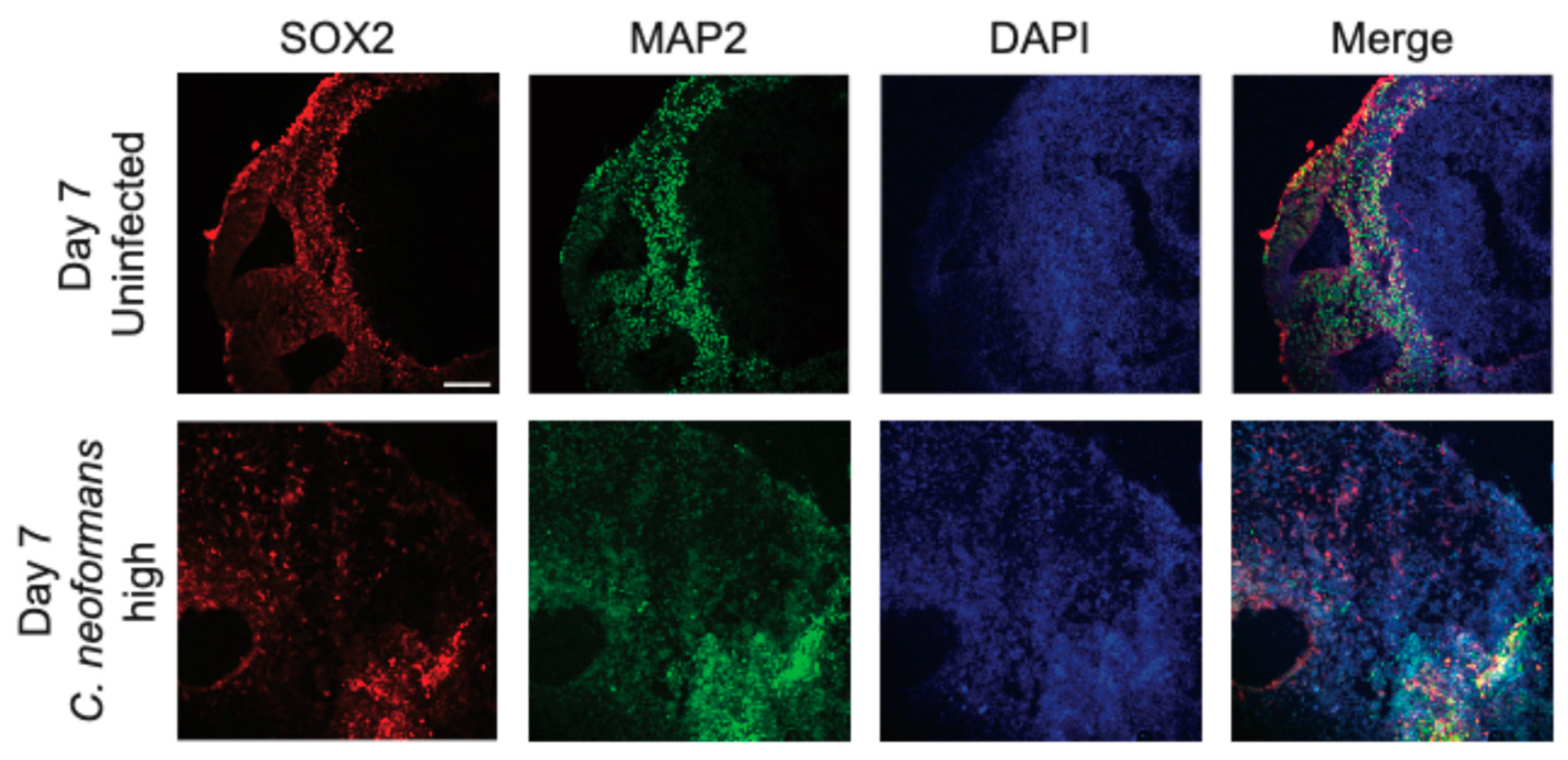

2.3. C. neoformans Infection Disrupts Organoid Cellular Architecture

2.4. Cryptococcal Infection Induces Cytokine Induction in Brain Organoids

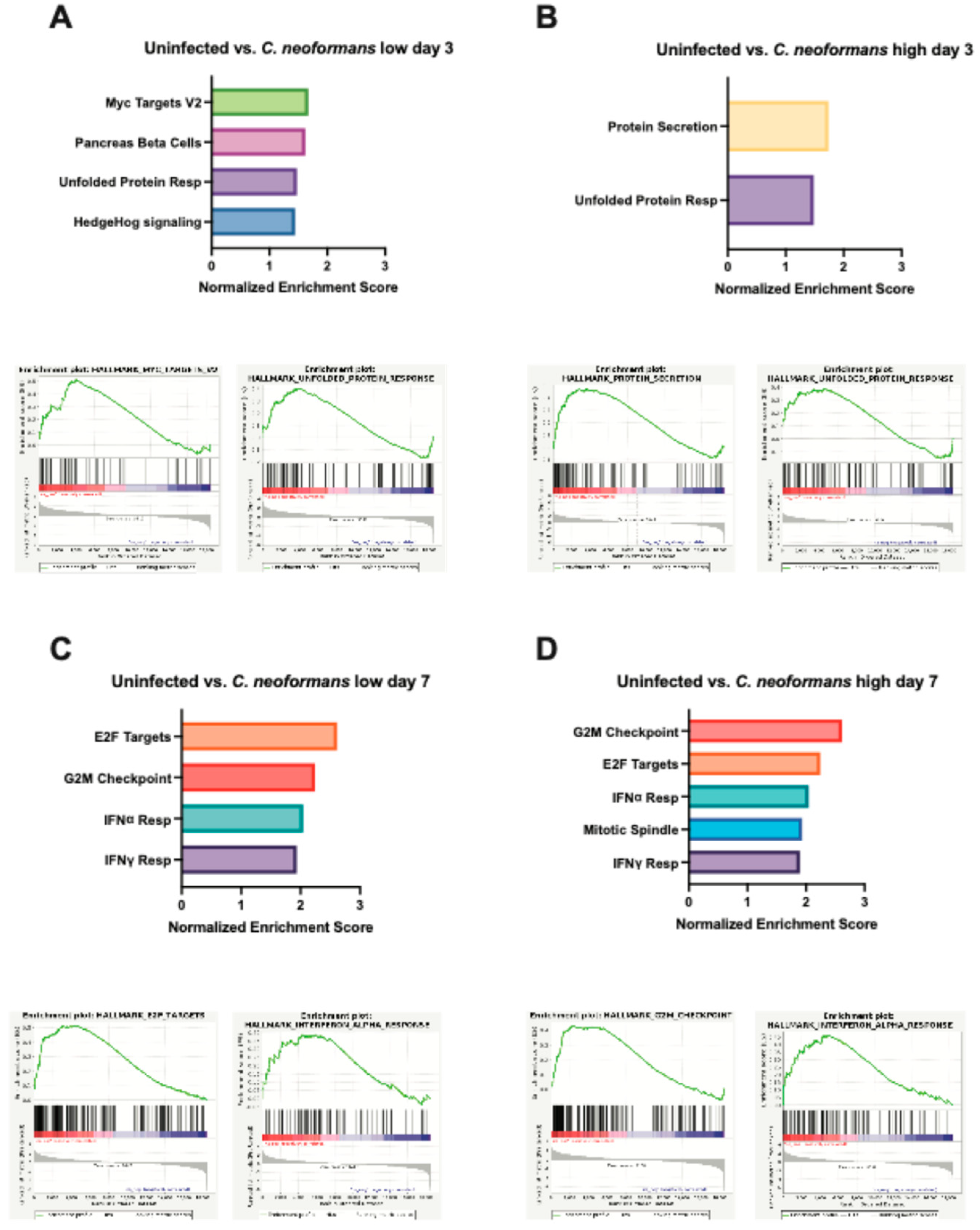

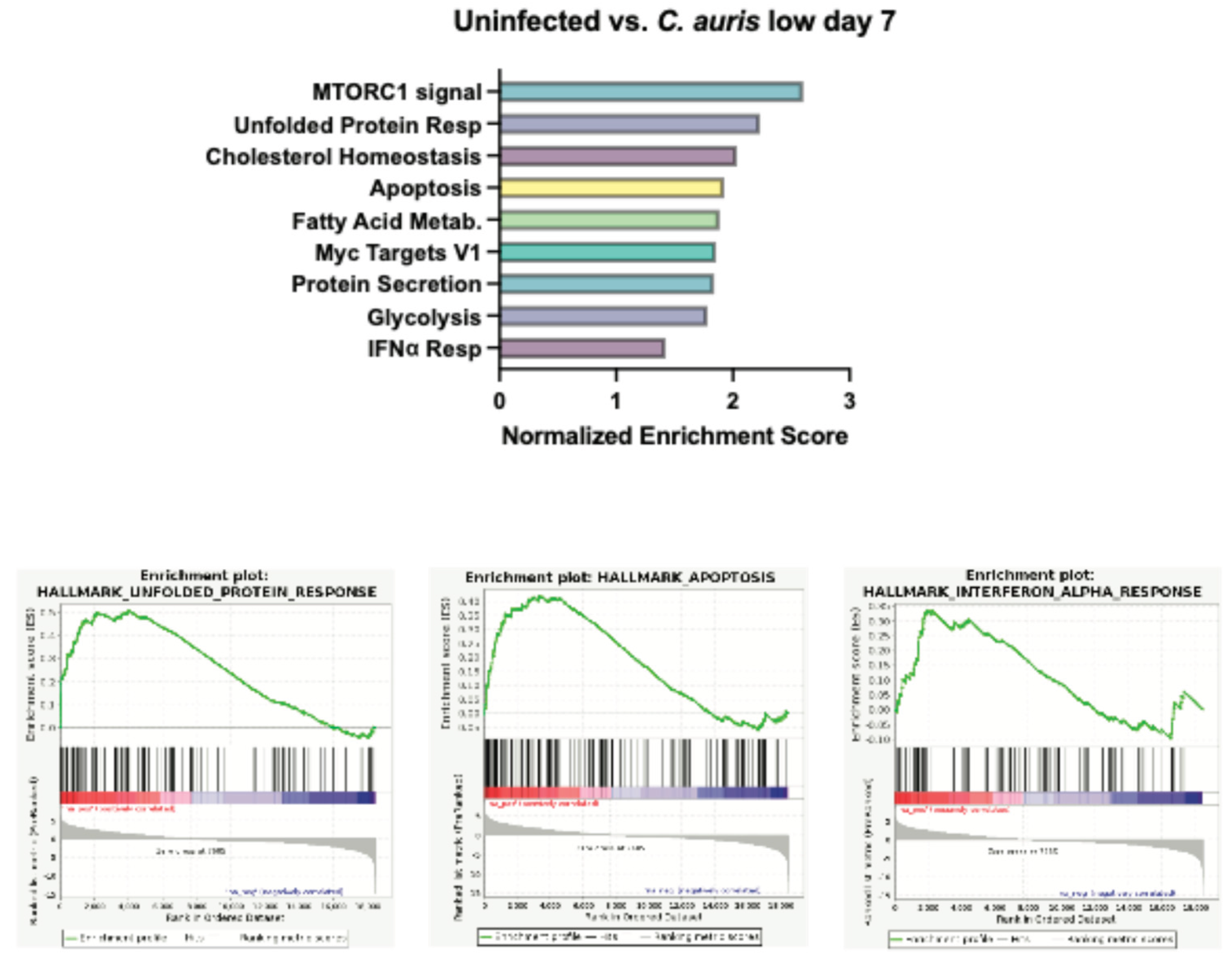

2.5. Organoid Transcriptional Response to Fungal Infection

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Organoid Generation from Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs)

4.2. Fungal Infection of Organoids

4.3. Growth Measurements

4.4. Organoid Collection for Staining, Embedding and Sectioning

4.3. Immunofluorescence Staining

4.4. Fungal, Periodic Acid Schiff Stain

4.5. Immunoblot Analysis

4.6. RNA Isolation and Sequencing

Acknowledgments

References

- Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17: 873–881. [CrossRef]

- Bratton EW, El Husseini N, Chastain CA, Lee MS, Poole C, Stürmer T, et al. Comparison and Temporal Trends of Three Groups with Cryptococcosis: HIV-Infected, Solid Organ Transplant, and HIV-Negative/Non-Transplant. Scheurer M, editor. PLoS One. 2012;7: e43582. [CrossRef]

- Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17: 873–881. [CrossRef]

- Sabiiti W, May RC. Mechanisms of Infection by the Human Fungal Pathogen Cryptococcus Neoformans. Future Microbiol. 2012;7: 1297–1313. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall A. Cryptococci at the brain gate: break and enter or use a Trojan horse? J Clin Invest. 2010;120: 1389. [CrossRef]

- Chang YC, Stins MF, McCaffery MJ, Miller GF, Pare DR, Dam T, et al. Cryptococcal Yeast Cells Invade the Central Nervous System via Transcellular Penetration of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Infect Immun. 2004;72: 4985. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Tirado FH, Klein RS, Doering TL. An In Vitro Brain Endothelial Model for Studies of Cryptococcal Transmigration into the Central Nervous System. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2019;53: e78. [CrossRef]

- Normile TG, Bryan AM, Del Poeta M. Animal Models of Cryptococcus neoformans in Identifying Immune Parameters Associated With Primary Infection and Reactivation of Latent Infection. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 581750. [CrossRef]

- Lee SC, Dickson DW, Casadevall A. Pathology of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis: Analysis of 27 patients with pathogenetic implications. Hum Pathol. 1996;27: 839–847. [CrossRef]

- Wensink GE, Elias SG, Mullenders J, Koopman M, Boj SF, Kranenburg OW, et al. Patient-derived organoids as a predictive biomarker for treatment response in cancer patients. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41698-021-00168-1;SUBJMETA=1059,2423,308,4028,53,575,67,692;KWRD=CANCER+THERAPY,PREDICTIVE+MARKERS,TRANSLATIONAL+RESEARCH.

- Dang J, Tiwari SK, Lichinchi G, Qin Y, Patil VS, Eroshkin AM, et al. Zika Virus Depletes Neural Progenitors in Human Cerebral Organoids through Activation of the Innate Immune Receptor TLR3. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19: 258. [CrossRef]

- Halioti A, Vrettou CS, Neromyliotis E, Gavrielatou E, Sarri A, Psaroudaki Z, et al. Cerebrospinal Drain Infection by Candida auris: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of Fungi. 2024;10: 859. [CrossRef]

- Reguera-Gomez M, Munzen ME, Hamed MF, Charles-Niño CL, Martinez LR. IL-6 deficiency accelerates cerebral cryptococcosis and alters glial cell responses. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21: 242. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Liu G, Ma J, Zhou L, Zhang Q, Gao L. Lack of IL-6 increases blood–brain barrier permeability in fungal meningitis. J Biosci. 2015;40: 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis JN, Meintjes G, Bicanic T, Buffa V, Hogan L, Mo S, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Cytokine Profiles Predict Risk of Early Mortality and Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11. [CrossRef]

- Huffnagle GB, McNeil LK. Dissemination of C. neoformans to the central nervous system: Role of chemokines, Th1 immunity and leukocyte recruitment. J Neurovirol. 1999;5: 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Hansakon A, Jeerawattanawart S, Pattanapanyasat K, Angkasekwinai P. IL-25 Receptor Signaling Modulates Host Defense against Cryptococcus neoformans Infection. The Journal of Immunology. 2020;205: 674–685. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Gault RA, Kozel TR, Murphy WJ. Protection from Direct Cerebral Cryptococcus Infection by Interferon-γ-Dependent Activation of Microglial Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178: 5753–5761. [CrossRef]

- Lee SC, Dickson DW, Brosnan CF, Casadevall A. Human astrocytes inhibit Cryptococcus neoformans growth by a nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;180: 365–369. [CrossRef]

- Uicker WC, Doyle HA, McCracken JP, Langlois M, Buchanan KL. Cytokine and chemokine expression in the central nervous system associated with protective cell-mediated immunity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Med Mycol. 2005;43: 27–38. [CrossRef]

- Neal LM, Xing E, Xu J, Kolbe JL, Osterholzer JJ, Segal BM, et al. Cd4+ T cells orchestrate lethal immune pathology despite fungal clearance during cryptococcus neoformans meningoencephalitis. mBio. 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Neal LM, Ganguly A, Kolbe JL, Hargarten JC, Elsegeiny W, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 is required for lethal brain pathology but not pathogen clearance during cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. Sci Adv. 2020;6: eaba2502. [CrossRef]

- Quadrato G, Nguyen T, Macosko EZ, Sherwood JL, Yang SM, Berger DR, et al. Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature. 2017;545: 48. [CrossRef]

- Juan-Mateu J, Rech TH, Villate O, Lizarraga-Mollinedo E, Wendt A, Turatsinze JV, et al. Neuron-enriched RNA-binding Proteins Regulate Pancreatic Beta Cell Function and Survival. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017;292: 3466–3480. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer I, Blanco R. N-myc and c-myc expression in Alzheimer disease, Huntington disease and Parkinson disease. Molecular Brain Research. 2000;77: 270–276. [CrossRef]

- Lee HG, Casadesus G, Nunomura A, Zhu X, Castellani RJ, Richardson SL, et al. The Neuronal Expression of MYC Causes a Neurodegenerative Phenotype in a Novel Transgenic Mouse. Am J Pathol. 2009;174: 891–897. [CrossRef]

- Lee HP, Kudo W, Zhu X, Smith MA, Lee H gon. Early induction of c-Myc is associated with neuronal cell death. Neurosci Lett. 2011;505: 124–127. [CrossRef]

- Sorrell TC, Juillard PG, Djordjevic JT, Kaufman-Francis K, Dietmann A, Milonig A, et al. Cryptococcal transmigration across a model brain blood-barrier: evidence of the Trojan horse mechanism and differences between Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii strain H99 and Cryptococcus gattii strain R265. Microbes Infect. 2016;18: 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Tirado FH, Klein RS, Doering TL. An In Vitro Brain Endothelial Model for Studies of Cryptococcal Transmigration into the Central Nervous System. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2019;53. [CrossRef]

- Vu K, Weksler B, Romero I, Couraud PO, Gelli A. Immortalized human brain endothelial cell line HCMEC/D3 as a model of the blood-brain barrier facilitates in vitro studies of central nervous system infection by cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8: 1803–1807. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall A. Cryptococci at the brain gate: break and enter or use a Trojan horse? J Clin Invest. 2010;120: 1389. [CrossRef]

- Lee SC, Dickson DW, Casadevall A. Pathology of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis: Analysis of 27 patients with pathogenetic implications. Hum Pathol. 1996;27: 839–847. [CrossRef]

- Erta M, Quintana A, Hidalgo J. Interleukin-6, a Major Cytokine in the Central Nervous System. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8: 1254. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe RD, Putoczki TL, Griffin MDW. Structural Understanding of Interleukin 6 Family Cytokine Signaling and Targeted Therapies: Focus on Interleukin 11. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 1424. [CrossRef]

- Hirohata S, Miyamoto T. Elevated levels of interleukin-6 in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and central nervous system invol vement. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33: 644–649. [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi MA, Sidén Å, Persson MAA, Norkrans G, Hagberg L, Chiodi F. Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 activity in HIV infection and inflammatory and noninflammatory diseases of the nervous system. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;57: 233–241. [CrossRef]

- Klein RS, Lin E, Zhang B, Luster AD, Tollett J, Samuel MA, et al. Neuronal CXCL10 Directs CD8+ T-Cell Recruitment and Control of West Nile Virus Encephalitis. J Virol. 2005;79: 11457. [CrossRef]

- Petrisko TJ, Bloemer J, Pinky PD, Srinivas S, Heslin RT, Du Y, et al. Neuronal CXCL10/CXCR3 Axis Mediates the Induction of Cerebral Hyperexcitability by Peripheral Viral Challenge. Front Neurosci. 2020;14. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Strickland A, Shi M. IFN-γ signaling is essential for the clearance of C. neoformans in the brain and survival of the infected mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2020;204: 231.2-231.2. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui AA, Brouwer AE, Wuthiekanun V, Jaffar S, Shattock R, Irving D, et al. IFN-γ at the Site of Infection Determines Rate of Clearance of Infection in Cryptococcal Meningitis. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174: 1746–1750. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Xu Y, Guo P, Chen YJ, Zhou J, Xia M, et al. CCL5/CCR5-mediated peripheral inflammation exacerbates blood‒brain barrier disruption after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J Transl Med. 2023;21: 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Pittaluga A. CCL5-glutamate cross-talk in astrocyte-neuron communication in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2017;8: 285787. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Xu Y, Guo P, Chen YJ, Zhou J, Xia M, et al. CCL5/CCR5-mediated peripheral inflammation exacerbates blood‒brain barrier disruption after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J Transl Med. 2023;21: 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Stawowczyk M, Naseem S, Montoya V, Baker DP, Konopka J, Reich NC. Pathogenic effects of IFIT2 and interferon-β during fatal systemic Candida albicans infection. mBio. 2018;9. [CrossRef]

- delFresno C, Soulat D, Roth S, Blazek K, Udalova I, Sancho D, et al. Interferon-β Production via Dectin-1-Syk-IRF5 Signaling in Dendritic Cells Is Crucial for Immunity to C. albicans. Immunity. 2013;38: 1176–1186. [CrossRef]

- Majer O, Bourgeois C, Zwolanek F, Lassnig C, Kerjaschki D, Mack M, et al. Type I Interferons Promote Fatal Immunopathology by Regulating Inflammatory Monocytes and Neutrophils during Candida Infections. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8: 10. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa V, Dutta O, McElrath C, Du P, Chang YJ, Cicciarelli B, et al. Type III interferon is a critical regulator of innate antifungal immunity. Sci Immunol. 2017;2. [CrossRef]

- Smeekens SP, Ng A, Kumar V, Johnson MD, Plantinga TS, Van Diemen C, et al. Functional genomics identifies type I interferon pathway as central for host defense against Candida albicans. Nat Commun. 2013;4. [CrossRef]

- Pekmezovic M, Hovhannisyan H, Gresnigt MS, Iracane E, Oliveira-Pacheco J, Siscar-Lewin S, et al. Candida pathogens induce protective mitochondria-associated type I interferon signalling and a damage-driven response in vaginal epithelial cells. Nature Microbiology 2021 6:5. 2021;6: 643–657. [CrossRef]

- Brown Harding H, Kwaku G, Reardon C, Khan N, Zamith-Miranda D, Zarnowski R, et al. Candida albicans Extracellular Vesicles Trigger Type I IFN Signaling via cGAS and STING. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9: 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Han F, Guo H, Wang L, Zhang Y, Sun L, Dai C, et al. The cGAS-STING signaling pathway contributes to the inflammatory response and autophagy in Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis. Exp Eye Res. 2021;202: 108366. [CrossRef]

- Kwaku GN, Jensen KN, Simaku P, Floyd DJ, Saelens JW, Reardon CM, et al. Extracellular vesicles from diverse fungal pathogens induce species-specific and endocytosis-dependent immunomodulation. PLoS Pathog. 2025;21: e1012879. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Muffat J, Omer A, Bosch I, Lancaster MA, Sur M, et al. Induction of expansion and folding in human cerebral organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;20: 385. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).