Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Advancements in Neural Vocoders

2.2. GAN-Based Non-Autoregressive Vocoders

2.3. Diffusion-Based Vocoders

2.4. Combining GANs and Diffusion: Emerging Synergies

2.5. Fixed-Point Iteration: A Theoretical Foundation for Iterative Refinement

2.6. Positioning Our Work: The Contribution of IterVocoder

3. Methodology

3.1. Neural Vocoding Task Definition

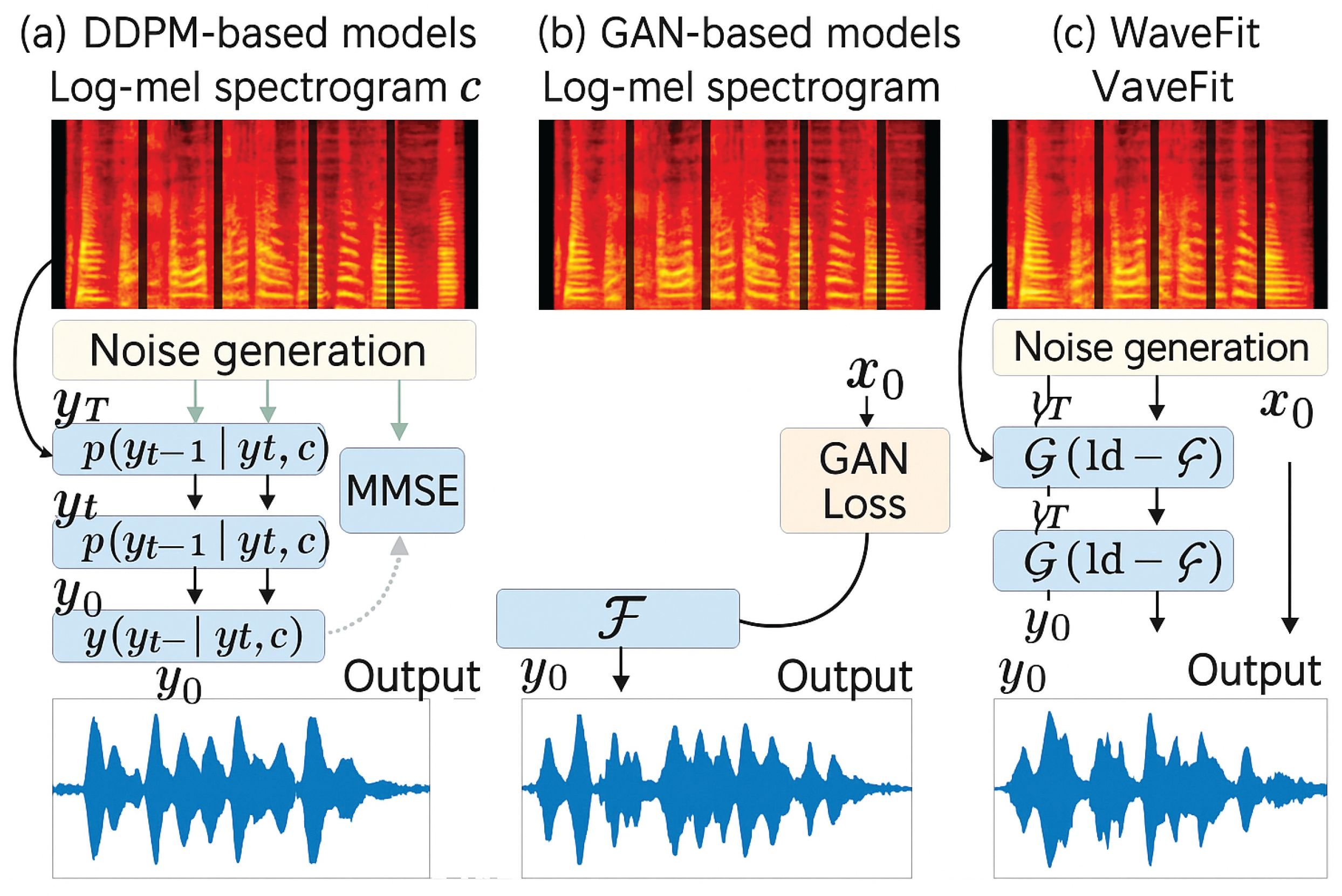

3.2. Preliminary: DDPM-Based Neural Vocoders

SpecGrad Loss

InferGrad Strategy

3.3. GAN-Based Vocoders

Multi-Resolution STFT Loss

3.4. Fixed-Point Iteration in Neural Vocoding

3.5. Proposed IterVocoder Framework

Final Objective

4. Experiments

4.1. Model Architecture and Implementation Details

- Architecture Overview: The IterVocoder framework is built on top of the WaveGrad Base model [42], consisting of 13.8M trainable parameters. For the denoising network , we adopt a U-Net-like architecture equipped with residual connections, layer normalization, and dilated convolutions for long-range temporal modeling. For adversarial supervision, we employ three GAN discriminators at different temporal resolutions (original, 2x, and 4x down-sampled) using the MelGAN backbone [34]. Each discriminator processes audio segments and outputs multi-frame logits, which are then aggregated through averaging.

- Noise Initialization and Conditioning: The initial noisy input is sampled using the SpecGrad algorithm [46]. For conditional input , we compute 128-dimensional log-mel spectrograms using a 24 kHz sampling rate with a Hann window of 50 ms, 12.5 ms frame shift, and a 2048-point FFT.

-

Loss Functions: Our generator is jointly supervised by the following loss functions:

- -

- Adversarial Losses: Generator and discriminator losses are defined via Equations Equation ?? and Equation ??, respectively.

- -

- Multi-resolution STFT Loss: Using three STFT settings ([360, 900, 1800], [80, 150, 300], and [512, 1024, 2048]), we apply to capture spectral fidelity at different temporal scales.

- -

- Mel-spectrogram Amplitude Loss: MAE is computed between the 128-dimensional mel features of generated and reference audio.

4.2. Training Setup and Baseline Models

- Dataset and Training: For training, we use a proprietary 184-hour US English dataset and the LibriTTS dataset [67]. Training is done using 128 Google TPU v3 cores with a global batch size of 512. We crop 1.5-second segments for training and follow optimizer hyperparameters from WaveGrad.

- Loss Weighting: On the proprietary dataset, we set and following SEANet [64]; for LibriTTS, we use and , and omit the mel amplitude loss.

-

Baselines: We include:

4.3. Objective Evaluation of Iterative Denoising

4.4. Main Results: MOS and Inference Speed

4.5. Side-by-Side Preference Results

4.6. Evaluation on GAN Baselines and Robustness

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

References

- S. Mehri, K. Kumar, I. Gulrajani, R. Kumar, S. Jain, and J. Sotelo, “SampleRNN: An unconditional end-to-end neural audio,” in Proc. ICLR, 2018.

- A. Tamamori, T. Hayashi, K. Kobayashi, K. Takeda, and T. Toda, “Speaker-dependent WaveNet vocoder.” in Proc. Interspeech, 2017.

- R. Prenger, R. Valle, and B. Catanzaro, “WaveGlow: A flow-based generative network for speech synthesis,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2019.

- W. Ping, K. Peng, K. Zhao, and Z. Song, “WaveFlow: A compact flow-based model for raw audio,” in Proc. ICML, 2020.

- J. Shen, R. Pang, R. J. Weiss, M. Schuster, N. Jaitly, Z. Yang, Z. Chen, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, R. Skerrv-Ryan, R. A. Saurous, Y. Agiomvrgiannakis, and Y. Wu, “Natural TTS synthesis by conditioning WaveNet on mel spectrogram predictions,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2018.

- J. Shen, Y. Jia, M. Chrzanowski, Y. Zhang, I. Elias, H. Zen, and Y. Wu, “Non-attentive Tacotron: Robust and controllable neural TTS synthesis including unsupervised duration modeling,” arXiv:2010.04301, 2020.

- I. Elias, H. Zen, J. Shen, Y. Zhang, Y. Jia, R. J. Weiss, and Y. Wu, “Parallel Tacotron: Non-autoregressive and controllable TTS,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2021.

- Y. Jia, H. Zen, J. Shen, Y. Zhang, and Y. Wu, “PnG BERT: Augmented BERT on phonemes and graphemes for neural TTS,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2021.

- Y. Ren, Y. Ruan, X. Tan, T. Qin, S. Zhao, Z. Zhao, and T.-Y. Liu, “FastSpeech: Fast, robust and controllable text to speech,” in Proc. NeurIPS, 2019.

- Y. Ren, C. Hu, X. Tan, T. Qin, S. Zhao, Z. Zhao, and T.-Y. Liu, “FastSpeech 2: Fast and high-quality end-to-end text to speech,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. (ICLR), 2021.

- B. Sisman, J. Yamagishi, S. King, and H. Li, “An overview of voice conversion and its challenges: From statistical modeling to deep learning,” IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process., 2021.

- W.-C. Huang, S.-W. Yang, T. Hayashi, and T. Toda, “A comparative study of self-supervised speech representation based voice conversion,” EEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process., 2022.

- Y. Jia, R. J. Weiss, F. Biadsy, W. Macherey, M. Johnson, Z. Chen, and Y. Wu, “Direct speech-to-speech translation with a sequence-to-sequence model,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2019.

- Y. Jia, M. T. Ramanovich, T. Remez, and R. Pomerantz, “Translatotron 2: High-quality direct speech-to-speech translation with voice preservation,” in Proc. ICML, 2022.

- A. Lee, P.-J. Chen, C. Wang, J. Gu, S. Popuri, X. Ma, A. Polyak, Y. Adi, Q. He, Y. Tang, J. Pino, and W.-N. Hsu, “Direct speech-to-speech translation with discrete units,” in Proc. 60th Annu. Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. (Vol. 1: Long Pap.), 2022.

- S. Maiti and M. I. Mandel, “Parametric resynthesis with neural vocoders,” in Proc. IEEE WASPAA, 2019.

- ——, “Speaker independence of neural vocoders and their effect on parametric resynthesis speech enhancement,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2020.

- J. Su, Z. Jin, and A. Finkelstein, “HiFi-GAN: High-fidelity denoising and dereverberation based on speech deep features in adversarial networks,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2020.

- ——, “HiFi-GAN-2: Studio-quality speech enhancement via generative adversarial networks conditioned on acoustic features,” in Proc. IEEE WASPAA, 2021.

- H. Liu, Q. Kong, Q. Tian, Y. Zhao, D. L. Wang, C. Huang, and Y. Wang, “VoiceFixer: Toward general speech restoration with neural vocoder,” arXiv:2109.13731, 2021.

- T. Saeki, S. Takamichi, T. Nakamura, N. Tanji, and H. Saruwatari, “SelfRemaster: Self-supervised speech restoration with analysis-by-synthesis approach using channel modeling,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2022.

- W. B. Kleijn, F. S. C. Lim, A. Luebs, J. Skoglund, F. Stimberg, Q. Wang, and T. C. Walters, “WaveNet based low rate speech coding,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2018.

- T. Yoshimura, K. Hashimoto, K. Oura, Y. Nankaku, and K. Tokuda, “WaveNet-based zero-delay lossless speech coding,” in Proc. SLT, 2018.

- J.-M. Valin and J. Skoglund, “A real-time wideband neural vocoder at 1.6kb/s using LPCNet,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2019.

- N. Zeghidour, A. Luebs, A. Omran, J. Skoglund, and M. Tagliasacchi, “SoundStream: An end-to-end neural audio codec,” IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech and Lang. Proc., 2022.

- A. van den Oord, S. Dieleman, H. Zen, K. Simonyan, O. Vinyals, A. Graves, N. Kalchbrenner, A. Senior, and K. Kavukcuoglu, “WaveNet: A generative model for raw audio,” arXiv:1609.03499, 2016.

- N. Kalchbrenner, W. Elsen, K. Simonyan, S. Noury, N. Casagrande, W. Lockhart, F. Stimberg, A. van den Oord, S. Dieleman, and K. Kavukcuoglu, “Efficient neural audio synthesis,” in Proc. ICML, 2018.

- J.-M. Valin and J. Skoglund, “LPCNet: Improving neural speech synthesis through linear prediction,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2019.

- A. van den Oord, Y. Li, I. Babuschkin, K. Simonyan, O. Vinyals, K. Kavukcuoglu, G. van den Driessche, E. Lockhart, L. C. Cobo, F. Stimberg, N. Casagrande, D. Grewe, S. Noury, S. Dieleman, E. Elsen, N. Kalchbrenner, H. Zen, A. Graves, H. King, T. Walters, D. Belov, and D. Hassabis, “Parallel WaveNet: Fast high-fidelity speech synthesis.” in Proc. ICML, 2018.

- D. J. Rezende and S. Mohamed, “Variational inference with normalizing flows,” in Proc. ICML, 2015.

- I. Goodfellow, J. Pouget-Abadie, M. Mirza, B. Xu, D. Warde-Farley, S. Ozair, A. Courville, and Y. Bengio, “Generative adversarial nets,” in Proc. NeurIPS, 2014.

- C. Donahue, J. McAuley, and M. Puckette, “Adversarial audio synthesis,” in Proc. ICLR, 2019.

- J. Kong, J. Kim, and J. Bae, “HiFi-GAN: Generative adversarial networks for efficient and high fidelity speech synthesis,” in Proc. NeurIPS, 2020.

- K. Kumar, R. Kumar, T. de Boissiere, L. Gestin, W. Z. Teoh, J. Sotelo, A. de Brébisson, Y. Bengio, and A. C. Courville, “MelGAN: Generative adversarial networks for conditional waveform synthesis,” in Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS), 2019.

- R. Yamamoto, E. Song, and J.-M. Kim, “Parallel WaveGAN: A fast waveform generation model based on generative adversarial networks with multi-resolution spectrogram,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2020.

- G. Yang, S. Yang, K. Liu, P. Fang, W. Chen, and L. Xie, “Multi-band MelGAN: Faster waveform generation for high-quality text-to-speech,” in Proc. IEEE SLT, 2021.

- J. You, D. Kim, G. Nam, G. Hwang, and G. Chae, “GAN vocoder: Multi-resolution discriminator is all you need,” arXiv:2103.05236, 2021.

- W. Jang, D. Lim, J. Yoon, B. Kim, and J. Kim, “UnivNet: A neural vocoder with multi-resolution spectrogram discriminators for high-fidelity waveform generation,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2021.

- T. Kaneko, K. Tanaka, H. Kameoka, and S. Seki, “iSTFTNet: Fast and lightweight mel-spectrogram vocoder incorporating inverse short-time Fourier transform,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2022.

- T. Bak, J. Lee, H. Bae, J. Yang, J.-S. Bae, and Y.-S. Joo, “Avocodo: Generative adversarial network for artifact-free vocoder,” arXiv:2206.13404, 2022.

- S.-g. Lee, W. Ping, B. Ginsburg, B. Catanzaro, and S. Yoon, “BigVGAN: A universal neural vocoder with large-scale training,” arXiv:2206.04658, 2022.

- N. Chen, Y. Zhang, H. Zen, R. J. Weiss, M. Norouzi, and W. Chan, “WaveGrad: Estimating gradients for waveform generation,” in Proc. ICLR, 2021.

- Z. Kong, W. Ping, J. Huang, K. Zhao, and B. Catanzaro, “DiffWave: A versatile diffusion model for audio synthesis,” in Proc. ICLR, 2021.

- M. W. Y. Lam, J. Wang, D. Su, and D. Yu, “BDDM: Bilateral denoising diffusion models for fast and high-quality speech synthesis,” in Proc. ICLR, 2022.

- S. Lee, H. Kim, C. Shin, X. Tan, C. Liu, Q. Meng, T. Qin, W. Chen, S. Yoon, and T.-Y. Liu, “PriorGrad: Improving conditional denoising diffusion models with data-dependent adaptive prior,” in Proc. ICLR, 2022.

- Y. Koizumi, H. Zen, K. Yatabe, N. Chen, and M. Bacchiani, “SpecGrad: Diffusion probabilistic model based neural vocoder with adaptive noise spectral shaping,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2022.

- T. Okamoto, T. Toda, Y. Shiga, and H. Kawai, “Noise level limited sub-modeling for diffusion probabilistic vocoders,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2021.

- K. Goel, A. Gu, C. Donahue, and C. Ré, “It’s Raw! audio generation with state-space models,” arXiv:2202.09729, 2022.

- Z. Chen, X. Tan, K. Wang, S. Pan, D. Mandic, L. He, and S. Zhao, “InferGrad: Improving diffusion models for vocoder by considering inference in training,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2022.

- Z. Xiao, K. Kreis, and A. Vahdat, “Tackling the generative learning trilemma with denoising diffusion GANs,” in Proc. ICLR, 2022.

- S. Liu, D. Su, and D. Yu, “DiffGAN-TTS: High-fidelity and efficient text-to-speech with denoising diffusion GANs,” arXiv:2201.11972, 2022.

- P. L. Combettes and J.-C. Pesquet, “Fixed point strategies in data science,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., 2021.

- J. Ho, A. Jain, and P. Abbeel, “Denoising diffusion probabilistic models,” in Proc. NeurIPS, 2020.

- A. Defossez, G. Synnaeve, and Y. Adi, “Real time speech enhancement in the waveform domain,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2020.

- G. T. Buzzard, S. H. Chan, S. Sreehari, and C. A. Bouman, “Plug-and-play unplugged: Optimization-free reconstruction using consensus equilibrium,” SIAM J. Imaging Sci., 2018.

- E. Ryu, J. Liu, S. Wang, X. Chen, Z. Wang, and W. Yin, “Plug-and-play methods provably converge with properly trained denoisers,” in Proc. ICML, 2019.

- J.-C. Pesquet, A. Repetti, M. Terris, and Y. Wiaux, “Learning maximally monotone operators for image recovery,” SIAM J. Imaging Sci., 2021.

- Y. Masuyama, K. Yatabe, Y. Koizumi, Y. Oikawa, and N. Harada, “Deep Griffin-Lim iteration,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2019.

- ——, “Deep Griffin–Lim iteration: Trainable iterative phase reconstruction using neural network,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process., 2021.

- R. Cohen, M. Elad, and P. Milanfar, “Regularization by denoising via fixed-point projection (RED-PRO),” SIAM J. Imaging Sci., 2021.

- H. H. Bauschke and P. L. Combettes, Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces. Springer, 2017.

- I. Yamada, M. Yukawa, and M. Yamagishi, Minimizing the Moreau envelope of nonsmooth convex functions over the fixed point set of certain quasi-nonexpansive mappings. Springer, 2011, pp. 345–390.

- N. Parikh and S. Boyd, “Proximal algorithms,” Found. Trends Optim., 2014.

- M. Tagliasacchi, Y. Li, K. Misiunas, and D. Roblek, “SEANet: A multi-modal speech enhancement network,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2020.

- S. Theodoridis, K. Slavakis, and I. Yamada, “Adaptive learning in a world of projections,” IEEE Signal Process. Mag., 2011.

- T. Hayashi, “Parallel WaveGAN implementation with Pytorch,” github.com/kan-bayashi/ParallelWaveGAN.

- H. Zen, R. Clark, R. J. Weiss, V. Dang, Y. Jia, Y. Wu, Y. Zhang, and Z. Chen, “LibriTTS: A corpus derived from LibriSpeech for text-to-speech,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2019.

- D. P. Kingma and J. L. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in Proc. ICLR, 2015.

- A. A. Gritsenko, T. Salimans, R. van den Berg, J. Snoek, and N. Kalchbrenner, “A spectral energy distance for parallel speech synthesis,” in Proc. NeurIPS, 2020.

- J. Sohl-Dickstein, E. Weiss, N. Maheswaranathan, and S. Ganguli, “Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamic,” in Proc. ICML, 2015.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- Endri Kacupaj, Kuldeep Singh, Maria Maleshkova, and Jens Lehmann. 2022. An Answer Verbalization Dataset for Conversational Question Answerings over Knowledge Graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.06734 (2022).

- Magdalena Kaiser, Rishiraj Saha Roy, and Gerhard Weikum. 2021. Reinforcement Learning from Reformulations In Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 459–469.

- Yunshi Lan, Gaole He, Jinhao Jiang, Jing Jiang, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2021. A Survey on Complex Knowledge Base Question Answering: Methods, Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 4483–4491. Survey Track.

- Yunshi Lan and Jing Jiang. 2021. Modeling transitions of focal entities for conversational knowledge base question answering. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers).

- Mike Lewis, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Veselin Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2020. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7871–7880.

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. 2019. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Pierre Marion, Paweł Krzysztof Nowak, and Francesco Piccinno. 2021. Structured Context and High-Coverage Grammar for Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (2021).

- Pradeep K. Atrey, M. Anwar Hossain, Abdulmotaleb El Saddik, and Mohan S. Kankanhalli. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia Systems, 16(6):345–379, April 2010. ISSN 0942-4962. [CrossRef]

- Meishan Zhang, Hao Fei, Bin Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yixin Cao, Fei Li, and Min Zhang. Recognizing everything from all modalities at once: Grounded multimodal universal information extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, and Tat-Seng Chua. Universal scene graph generation. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Jingkang Yang, Xiangtai Li, Juncheng Li, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. Learning 4d panoptic scene graph generation from rich 2d visual scene. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Yaoting Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yuecheng Zhang, Shuicheng Yan, Ziwei Liu, Jiebo Luo, and Hao Fei. Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.12605, 2025.

- Hao Fei, Yuan Zhou, Juncheng Li, Xiangtai Li, Qingshan Xu, Bobo Li, Shengqiong Wu, Yaoting Wang, Junbao Zhou, Jiahao Meng, Qingyu Shi, Zhiyuan Zhou, Liangtao Shi, Minghe Gao, Daoan Zhang, Zhiqi Ge, Weiming Wu, Siliang Tang, Kaihang Pan, Yaobo Ye, Haobo Yuan, Tao Zhang, Tianjie Ju, Zixiang Meng, Shilin Xu, Liyu Jia, Wentao Hu, Meng Luo, Jiebo Luo, Tat-Seng Chua, Shuicheng Yan, and Hanwang Zhang. On path to multimodal generalist: General-level and general-bench. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2025.

- Jian Li, Weiheng Lu, Hao Fei, Meng Luo, Ming Dai, Min Xia, Yizhang Jin, Zhenye Gan, Ding Qi, Chaoyou Fu, et al. A survey on benchmarks of multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632, 2024.

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553):436–444, may 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608.

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.1090, 2014.

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. In The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pp. 1–6. IEEE, aug 2013. ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3. https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN.2013.6706748. URL http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=6706748. [CrossRef]

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014.

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024.

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, “Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions,” TPAMI, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 664–676, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2151–2161, 2020.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 11513–11521, 2022.

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4232–4241, 2022.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 7692–7699, 2020.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9871–9881, 2022.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion, 100:101919, 2023.

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09541, 2018.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11719, 2023.

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357, 2024.

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, pages 15460–15475, 2022.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics, 37(1):9–27, 2011.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 22(3), 2021.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2593–2608, 2023.

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05250, 2016.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021b.

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11255, 2023.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N19-1423. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR, abs/2309.05519, 2023.

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv, 2019.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024,, 2024.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 11:1–10, 01 2021.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05127, 2024.

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy, 11(12):2411, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management, 57(6):102311, 2020.

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022.

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: a conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(4):1–22, 2018.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023.

- P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 41(2):50:1–50:32, 2023.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 34(9):5544–5556, 2023.

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03044, 2(3):5, 2015.

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 23(8):1177–1193, 2012.

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

| Method | MOS (↑) | RTF (↓) |

|---|---|---|

| InferGrad-2 | ||

| IterVocoder-2 | ||

| SpecGrad-3 | ||

| InferGrad-3 | ||

| IterVocoder-3 | ||

| InferGrad-5 | ||

| WaveRNN | ||

| IterVocoder-5 | ||

| Ground-truth | − |

| Method-A | Method-B | SxS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IterVocoder-3 | InferGrad-3 | ||

| IterVocoder-3 | WaveRNN | ||

| IterVocoder-5 | InferGrad-5 | ||

| IterVocoder-5 | WaveRNN | ||

| IterVocoder-5 | Ground-truth |

| Method | MOS (↑) | SxS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MB-MelGAN | |||

| HiFi-GAN V1 | |||

| Ground-truth | |||

| IterVocoder-5 | − | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).