Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Examination

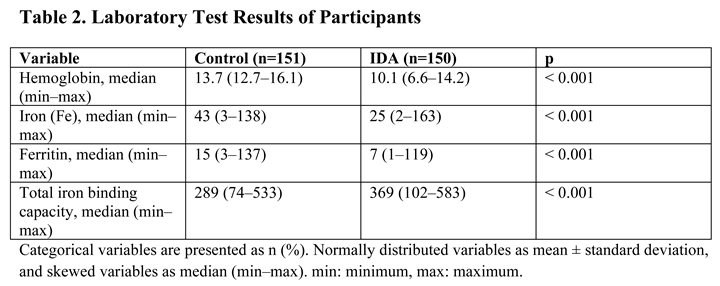

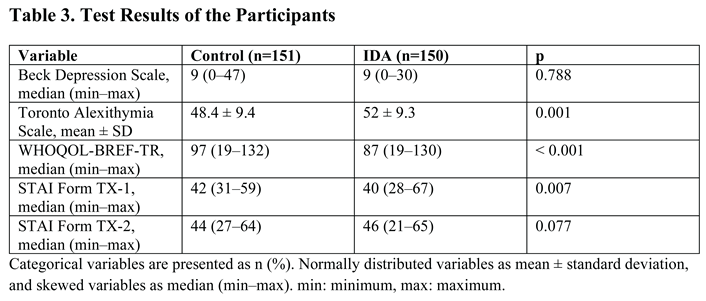

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- WHO. Anaemia. An Overview (WHO, 2021).

- Alem, A. Z. , Efendi, F., McKenna, L., Felipe-Dimog, E. B., Chilot, D., Tonapa, S. I.,..., Zainuri, A. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia in women of reproductive age across low-and middle-income countries based on national data. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 20335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- East P, Doom JR, Blanco E, Burrows R, Lozoff B, Gahagan S. Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive and educational outcomes in young adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2021, 57, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirci, K. , BAŞ, F. Y., Arslan, B., Salman, Z., Akpinar, A.,, DEMİRDAŞ, A. Demir Eksikliği Anemisi Olan Kadın Hastalarda Erişkin Dikkat Eksikliği Hiperaktivite Belirtilerinin ve Tanısının Araştırılması. Arch Neuropsychiatry 2017, 54, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira A, Neves P, Gozzelino R. Multilevel Impacts of Iron in the Brain: The Cross Talk between Neurophysiological Mechanisms, Cognition, and Social Behavior. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H. E. , Bhawnani, N., Ethirajulu, A., Alkasabera, A., Onyali, C. B., Anim-Koranteng, C.,, Mostafa, J. A. (.

- Kim, J.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Wessling-Resnick M. Iron and mechanisms of emotional behavior. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2014, 25, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed T, Lamoureux-Lamarche C, Berbiche D, Vasiliadis HM. The association between anemia and depression in older adults and the role of treating anemia. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. J. , Han, K. D., Cho, K. H., Kim, Y. H.,, Park, Y. G. Anemia and health-related quality of life in South Korea: data from the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2008–2016. BMC public health 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss WE, Auerbach M. Health-related quality of life in patients with iron deficiency anemia: impact of treatment with intravenous iron. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2018, 9, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogeveen J, Grafman J. Alexithymia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2021, 183, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, R. F. , Hall, R. J., Williams, C. M.,, Hasan, N. T. Gender differences in alexithymia. Psychology of men, masculinity 2009, 10, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, L. , Demartini, B., Fotopoulou, A.,, Edwards, M. J. Alexithymia in neurological disease: a review. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences 2015, 27, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz O, Şengül Y, Şengül HS, Parlakkaya FB, Öztürk A. Investigation of alexithymia and levels of anxiety and depression among patients with restless legs syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018, 14, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terock, J. , Hannemann, A., Weihs, A., Janowitz, D.,, Grabe, H. J. Alexithymia is associated with reduced vitamin D levels, but not polymorphisms of the vitamin D binding-protein gene. Psychiatric Genetics 2021, 31, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban E, Timurağaoğlu A. Yaşlı hastalarda demir eksikliği anemisine yaklaşım. T Klin J Med Sci 2004, 24, 267–270. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisli, N. Beck Depresyon Ölçeğinin bir Türk örnekleminde geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği [Reliability and validity of Beck Depression Scale in a Turkish sample] Psikoloji Dergisi. 1988, 6, 118–122. 6.

- Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale – I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç H, Köse S, Güleç MY. Reliability and factorial validity of the Turkish version of the 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS-20) Klinik Psikofarmakol Bülteni. 2009, 19, 214–220.

- Öner N, Le Compte A. Süreksiz durumluk /sürekli kaygı envanteri el kitabı. 1. Baskı. İstanbul: Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yayını, 1983; 1-26.

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Test manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. 1st ed. California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970.

- The WHOQOL Group: The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine 1998, 46, 1569–1585. [CrossRef]

- Eser SY, Fidaner H, Fidaner C, Elbi H, Eser E: Yaşam kalitesinin ölçülmesi, WHOQOL-100 ve WHOQOL-BREF. 3P Dergisi 1999 ;(7): 5-13 (Ek 2).

- gholamreza Noorazar, S. , Ranjbar, F., Nemati, N., Yasamineh, N.,, Kalejahi, P. Relationship between severity of depression symptoms and iron deficiency anemia in women with major depressive disorder. Journal of Research in Clinical Medicine 2015, 3, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. S. , Chao, H. H., Huang, W. T., Chen, S. C. C.,, Yang, H. Y. Psychiatric disorders risk in patients with iron deficiency anemia and association with iron supplementation medications: a nationwide database analysis. BMC psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, H. , Arshad, A., Hafiz, M. Y., Muhammad, G., Khatri, S.,, Arain, F. Psychiatric Manifestations of Iron Deficiency Anemia-A Literature Review. European Psychiatry 2023, 66, S243–S244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin EJ, Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Low hemoglobin level is a risk factor for postpartum depression. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 4139–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacar G, Sans T, Martin-Santos R et al. An association between plasma ferritin concentrations measured 48 h after delivery and postpartum depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters HJCM, van der Klauw MM, de Witte T, Stauder R, Swinkels DW, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Huls G. Association of anemia with health-related quality of life and survival: a large population-based cohort study. Haematologica. 2019, 104, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A. K. , Vare, S., Sircar, S., Joshi, A. D.,, Jain, D. Impact of iron deficiency anemia on quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Advances in Digestive Medicine 2023, 10, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlexanderMKewalramaniRAgodoaIGlobeDAssociation of anemia correction with health related quality of life in patients not on dialysisCurr Med Res Opin200723122997300817958944.

- Strauss, W. E. ,, Auerbach, M. Health-related quality of life in patients with iron deficiency anemia: impact of treatment with intravenous iron. Patient related outcome measures.

- Schore, AN. Relational trauma, brain development and dissociation. In: Ford JD, Courtois CA, editors. Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models. New York: The Guilford Press;

- Ricciardi, L. , Demartini, B., Fotopoulou, A.,, Edwards, M. J. Alexithymia in neurological disease: a review. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences 2015, 27, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M. E. , McFarlane, T.,, Cassin, S. Alexithymia and eating disorders: a critical review of the literature. Journal of eating disorders 2013, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A. D. , Babienko, V.,, Kobolev, E. Influence of latent iron deficiency on cognitive abilities in students. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2022, 12, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, N. D. ,, ARIKAN, İ. The relationship between alexithymia, anxiety, depression, and severity of the disease in psoriasis patients. Journal of Surgery and Medicine 2020, 4, 226–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tesio V, Di Tella M, Ghiggia A, Romeo A, Colonna F, Fusaro E, Geminiani GC, Castelli L. Alexithymia and Depression Affect Quality of Life in Patients With Chronic Pain: A Study on 205 Patients With Fibromyalgia. Front Psychol. 2018, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Control (n=151) | IDA Group (n=150) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female: 151 (100%) | Female: 150 (100%) | |

| Marital Status | Single/Widowed: 62 (41.1%) Married: 89 (58.9%) |

Single/Widowed: 49 (32.7%) Married: 101 (67.3%) |

0.131 |

| Age, median (min–max) | 31 (18–64) | 36 (16–68) | 0.048 |

| Level of Education | Illiterate: 1 (0.7%) Primary: 15 (9.9%) High school: 33 (21.9%) University: 102 (67.5%) |

Illiterate: 1 (0.7%) Primary: 15 (10%) High school: 40 (26.7%) University: 94 (62.7%) |

0.803 |

| Place of Residence | Rural: 6 (4%) Urban: 145 (96%) |

Rural: 7 (4.7%) Urban: 143 (95.3%) |

0.767 |

| Household Income Level | Low: 28 (18.5%) Medium: 111 (73.5%) High: 12 (8%) |

Low: 14 (9.3%) Medium: 129 (86%) High: 7 (4.7%) |

0.026* |

| Alcohol Consumption | No: 144 (95.4%) Yes: 7 (4.6%) |

No: 145 (96.7%) Yes: 5 (3.3%) |

0.564 |

| Smoking | No: 126 (83.4%) Yes: 25 (16.6%) |

No: 114 (76%) Yes: 36 (24%) |

0.108 |

| Psychiatric Illness History | No: 148 (98%) Yes: 3 (2%) |

No: 145 (96.7%) Yes: 5 (3.3%) |

0.501 |

| Family Psychiatric History | No: 148 (98%) Yes: 3 (2%) |

No: 145 (96.7%) Yes: 5 (3.3%) |

0.501 |

| Suicide Attempt | No: 150 (99.3%) Yes: 1 (0.7%) |

No: 149 (99.3%) Yes: 1 (0.7%) |

0.996 |

| IDA Treatment History | No: 68 (45%) Yes: 83 (55%) |

No: 47 (31.3%) Yes: 103 (68.7%) |

0.014* |

|

|

| Variable | No Alexithymia (n=175) | Probable Alexithymia or Alexithymia (n=126) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (min–max) | 34 (16–64) | 35 (18–68) | 0.333 |

| Marital Status | Single or widowed: 67 (38.3) Married: 108 (61.7) |

Single or widowed: 44 (34.9) Married: 82 (65.1) |

0.551 |

| Level of Education | Illiterate: 14 (8) Primary school: 47 (26.9) High school: 112 (64) University: 2 (1.1) |

Illiterate: 16 (12.7) Primary school: 26 (20.6) High school: 84 (66.7) University: 0 (0) |

0.230 |

| Place of residence | Rural: 4 (2.3) Urban: 171 (97.7) |

Rural: 9 (7.1) Urban: 117 (92.9) |

0.041 |

| Household income level | Low: 31 (17.7) Medium: 133 (76) High: 11 (6.3) |

Low: 11 (8.7) Medium: 107 (84.9) High: 8 (6.3) |

0.083 |

| Alcohol consumption | No: 168 (96) Yes: 7 (4) |

No: 121 (96) Yes: 5 (4) |

0.989 |

| Smoking | No: 139 (79.4) Yes: 36 (20.6) |

No: 101 (80.2) Yes: 25 (19.8) |

0.876 |

| Iron-deficiency Anemia | No: 101 (57.7) Yes: 74 (42.3) |

No: 50 (39.7) Yes: 76 (60.3) |

0.002 |

| Hemoglobin, median (min–max) | 13 (6.6–16) | 11.4 (7–16.1) | 0.017 |

| Iron (Fe), median (min–max) | 34 (2–133) | 29 (2–163) | 0.062 |

| Ferritin, median (min–max) | 11 (2–137) | 9 (1–135) | 0.288 |

| Total iron binding capacity, median (min–max) | 302 (74–583) | 334 (130–571) | 0.084 |

| Beck Depression Scale, median (min–max) | 7 (0–34) | 10 (0–47) | < 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-BREF-TR, median (min–max) | 98 (19–132) | 86 (49–115) | < 0.001 |

| STAI Form TX-1, median (min–max) | 42 (31–59) | 41 (28–67) | 0.443 |

| STAI Form TX-2, median (min–max) | 44 (21–65) | 46 (31–64) | < 0.001 |

| Parameter | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| WHOQOL-BREF-TR | -0.431 | < 0.001* |

| Beck Depression Scale | 0.302 | < 0.001* |

| STAI Form TX-2 | 0.169 | 0.003* |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | -0.175 | 0.002* |

| Iron (Fe) | -0.164 | 0.004* |

| Total iron binding capacity | 0.117 | 0.042* |

| STAI Form TX-1 | -0.095 | 0.102 |

| Ferritin | -0.069 | 0.235 |

| Age | 0.009 | 0.873 |

| Risk Factors | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Total iron binding capacity | 1.003 (1.000–1.006) | 0.044* |

| Beck Depression Scale | 1.032 (0.998–1.068) | 0.068 |

| WHOQOL-BREF-TR | 0.966 (0.950–0.982) | < 0.001* |

| STAI Form TX-2 | 1.098 (1.050–1.147) | < 0.001* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).