1. Introduction

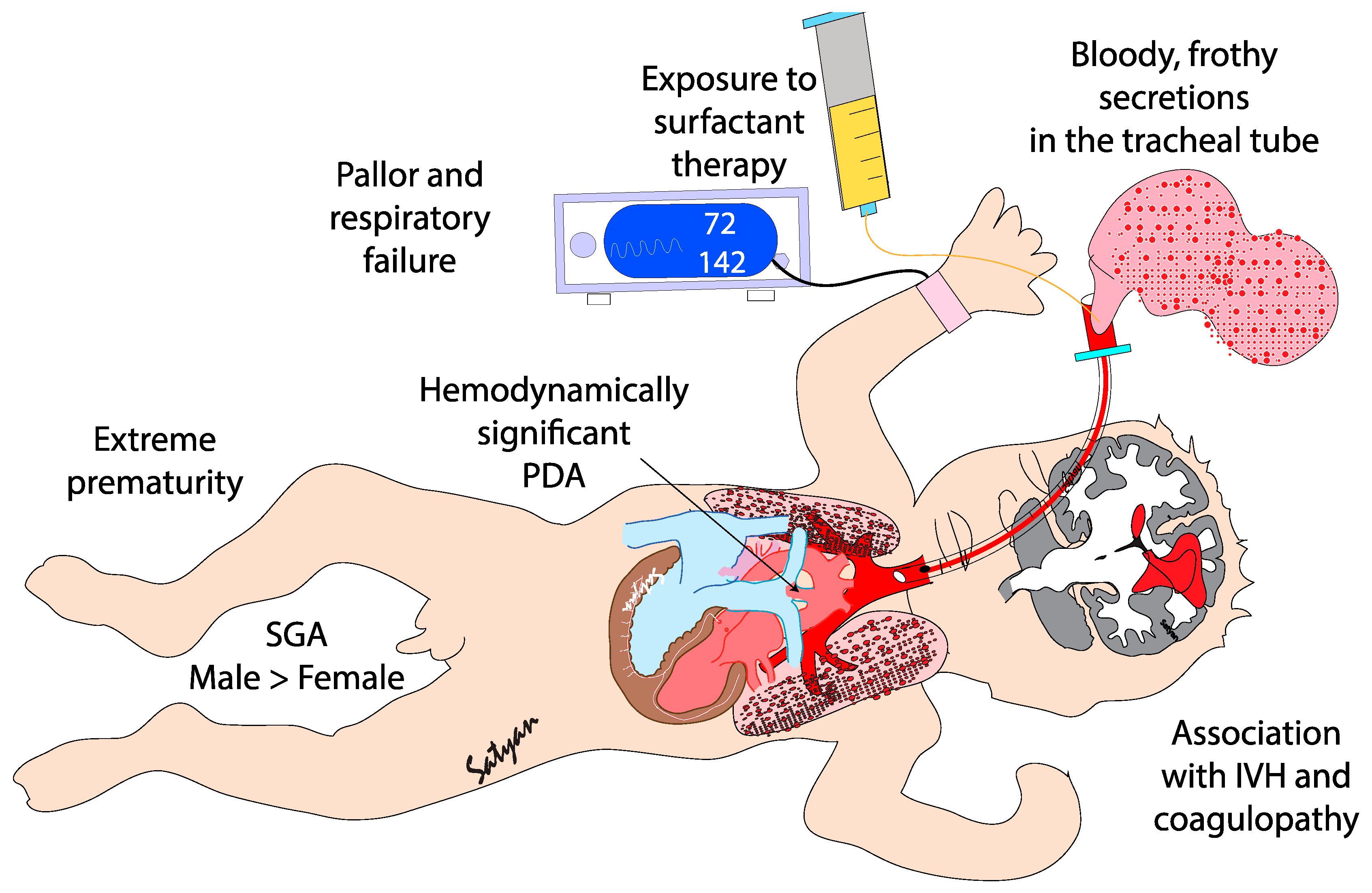

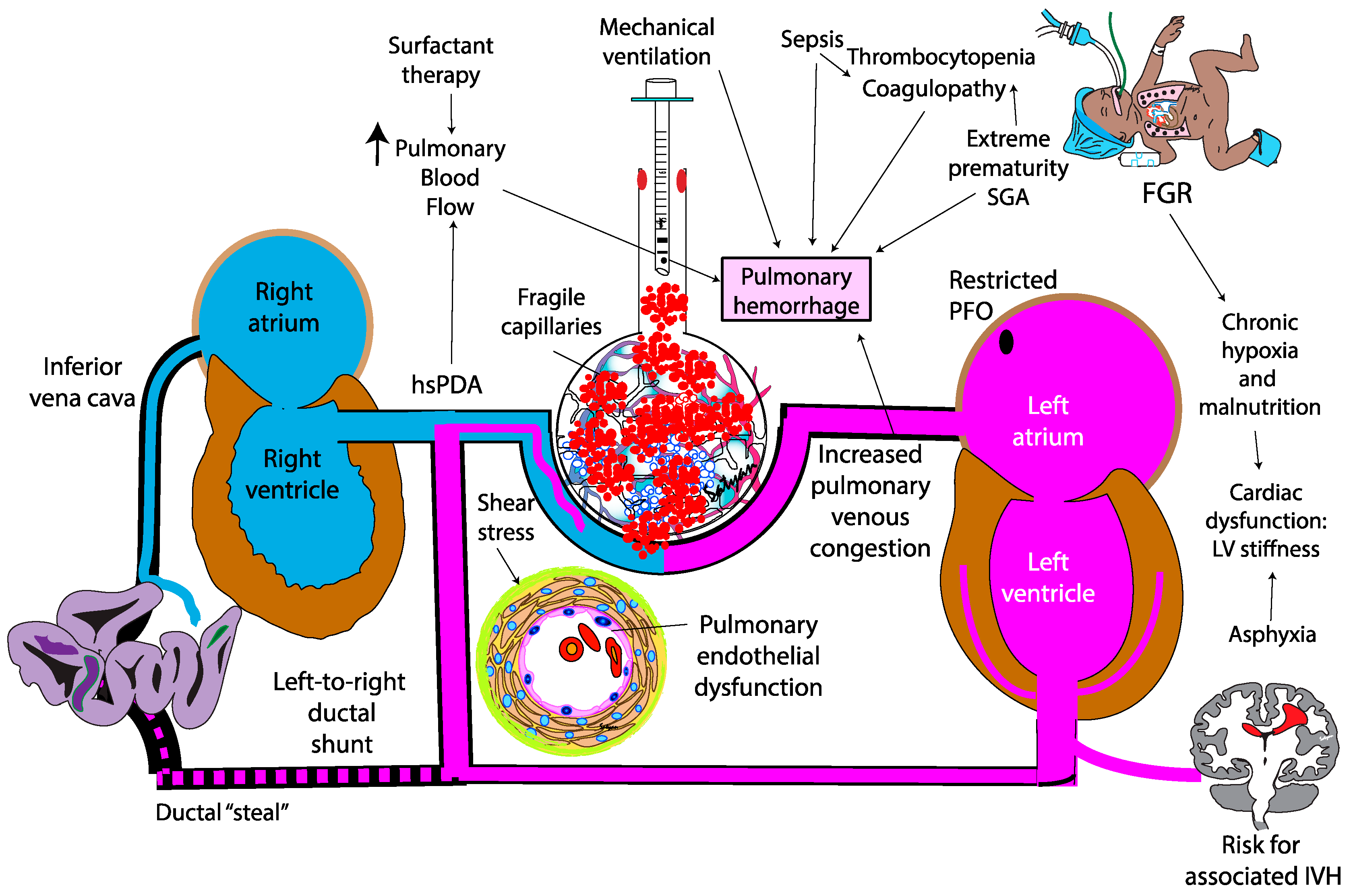

Pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) is generally described as an acute event characterized by the sudden discharge of bloody fluid from the upper respiratory tract or through the endotracheal tube.[

1] PH is a severe and often life-threatening condition primarily affecting premature infants, particularly those with very low birth weight (VLBW)[

2] and intrauterine growth restriction (FGR) or small for gestational age (SGA)[

3]. It mainly occurs during the first 48 to 96 hours of life, i.e. during the transitional period.[

4] PH is characterized by rapid clinical deterioration, often leading to acute hypoxemia and respiratory failure. Its occurrence is strongly associated with several neonatal complications, including birth asphyxia and hypothermia[

5], respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) [

6,

7,

8], sepsis[

9,

10], and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)[

8,

10](

Figure 1). The introduction of surfactant therapy has significantly improved neonatal outcomes in RDS management, yet paradoxically, it has been linked to an increased risk of PH in certain high-risk populations[

11,

12]. Despite advances in neonatal care, PH remains a major cause of mortality and long-term morbidity in preterm infants[

9,

12]. This review will explore the epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, clinical diagnosis, management strategies, and outcomes associated with PH in neonates.

2. Epidemiology

PH is a major complication in very premature infants, particularly those with very low birth weight (VLBW, <1500 grams) and extremely low birth weight (ELBW, <1000 grams). Its overall incidence range from 1 to 12 per 1,000 live births[

6], but rises to approximately 11.9%[

13] in VLBW infants. Associated mortality is up to 57%[

14]. While regional variations are likely, detailed geographic data are limited. In high-income setting, PH is more frequently reported, reflecting broader access to neonatal intensive care and interventions such as surfactant therapy and high-frequency ventilation. In low-resource settings, limited access to NICUs and specialized care leads to underreporting of PH and higher mortality rates due to delayed interventions[

15]. A 2012 systematic review reported a PH incidence in high-income countries ranging from 1 to 12 per 1,000 live births[

4]. A study from China found PH in 6.6% of infants born with <1,500 grams and 22.9% in infants with BW <1,000 grams[

16]. Variability in incidence and outcomes is influenced by differences in the definition of PH and care practices, including timing and frequency of surfactant administration, antenatal steroid use, and availability of advanced ventilatory support. Regional studies underscore PH contribution to neonatal mortality: in Taiwan, PH accounted for 10.5% of deaths among VLBW infants, with one multicenter study reporting a rate between 2.2 and 27.6% across hospitals. [

17]. Similarly, a Korean tertiary center reported rates of 20.5% in ELBW and 14.8% in VLBW infants[

13].

Demographic factors also influence PH incidence. Male infants have a higher incidence than females[

18]. Access to prenatal care reduces the risk of prematurity and PH[

19], while socioeconomic disparities increase vulnerability through poorer maternal health, less access to prenatal care, and limited neonatal care[

15]. Data on ethnic differences in PH remain limited, emphasizing the need for further research.

3. Pathogenesis

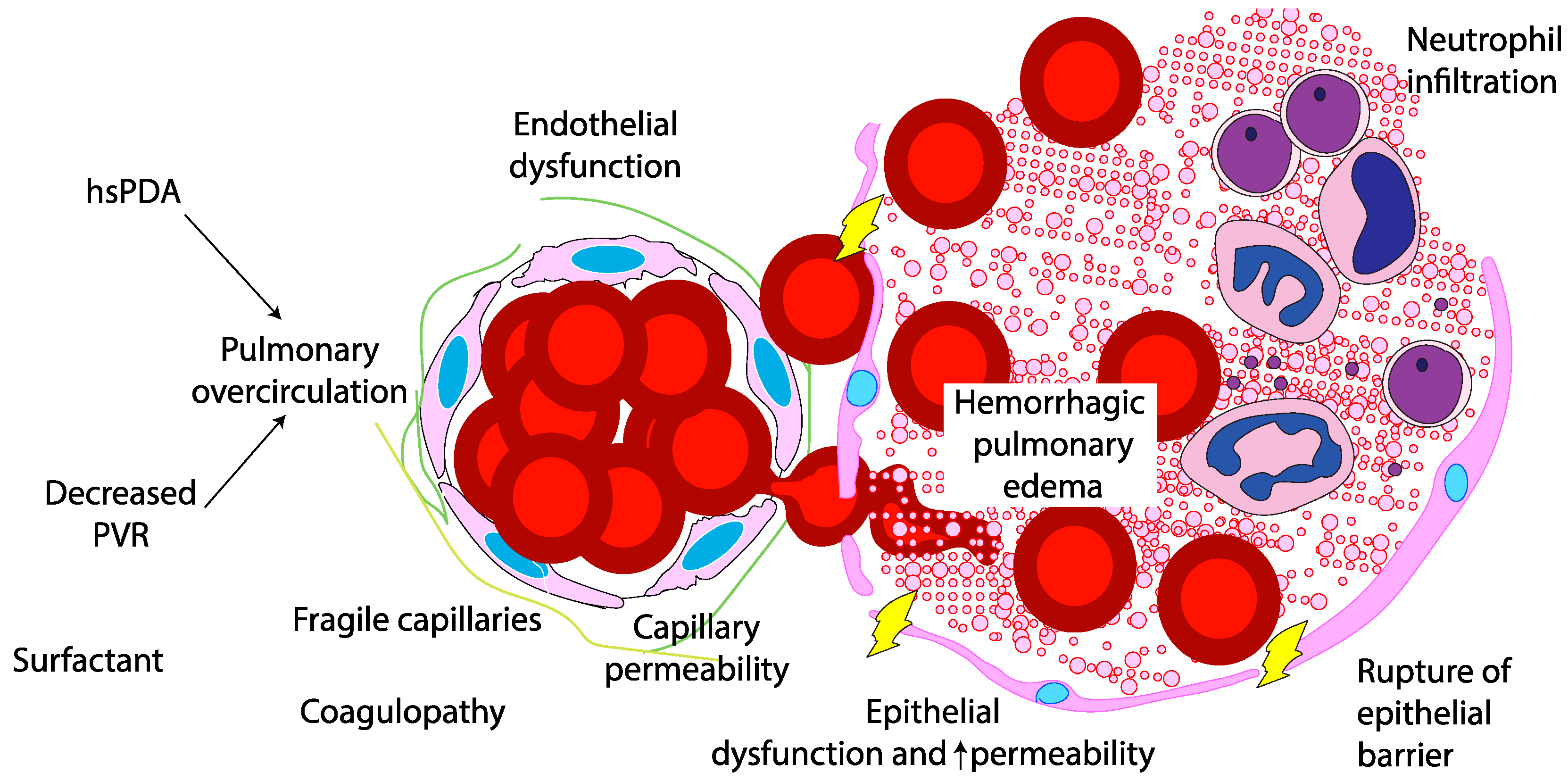

The pathogenesis of PH in neonates is multifactorial, driven by both structural and functional immaturity of the pulmonary vasculature. Similar to intraventricular hemorrhage, PH primarily affects premature infants whose fragile capillaries are highly susceptible to rupture under fluctuating hemodynamic conditions. (

Figure 2) During the immediate postnatal transition, the physiological drop in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) leads to a sudden increase in pulmonary blood flow. In preterm infants, this surge in blood flow can overwhelm underdeveloped vascular structures. In this context, a combination of vascular fragility, immature autoregulatory mechanisms, immature cardiac function, genetic predisposition, and iatrogenic factors – such as positive pressure ventilation and fluids shifts – can exacerbate capillary stress, precipitating hemorrhagic episodes. Emerging evidence suggests that hemodynamic conditions and genetic predispositions[

20] may further modulate individual susceptibility to PH, emphasising the need for personalized approaches to risk stratification and management.

The degree of prematurity is the most significant risk factor for PH, with infants born before 30 weeks of gestation being particularly vulnerable. The structural immaturity of the pulmonary capillary network in these infants result in increased fragility, making it more prone to rupture under stress.[

17,

21]. This increased risk is attributed to a combination of immature lung development, frequent presence of RDS requiring surfactant administration, and the inherent fragility of the pulmonary capillary network. As birth weight decreases, the risk of PH rises significantly.[

22].

Platelet dysfunction is recognized as another contributing factor to pulmonary hemorrhage in preterm neonates, particularly among those with very low birth weight (VLBW). In this population, bleeding events most commonly occur within the first week of life, which corresponds to the period when platelet dysfunction tends to be most pronounced.[

23]

4. Factors Contributing to Pulmonary Hemorrhage

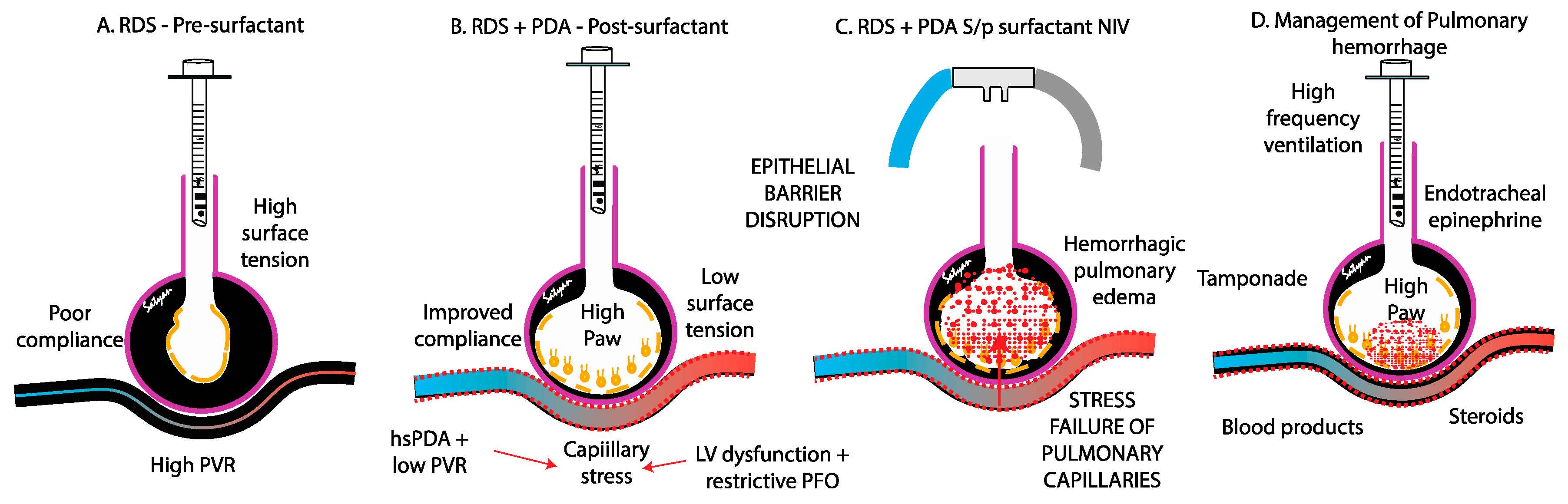

4.1. Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS)

Extreme premature infants are born at a critical stage of pulmonary development, where alveolarization is incomplete, surfactant production has not started or remains insufficient, and airways as well as pulmonary vascular structures are still immature.

During the course of RDS, infants with surfactant deficiency are at high risk for alveolar edema due to the accumulation of fluid and erythrocytes within the alveoli. This accumulation increases alveolar epithelial permeability, promoting infiltration by immune cells and proinflammatory cytokines, particularly neutrophils - key mediators of the innate immune response. Over time, the disruption of intercellular junctions leads to epithelial barrier breakdown, allowing further migration of fluid and red blood cells into the air spaces, further compromising gas exchange[

24].[

25]

The rapid improvement in lung compliance with surfactant exposure can lead to a sudden reduction in PVR, abruptly increasing pulmonary blood flow. This sudden hemodynamic and compliance change increases the risk of capillary rupture, loss of epithelial and endothelial integrity and bleeding, precipitating PH (

Figure 3).[

17,

26,

27]. A meta-analysis of surfactant therapy has shown a modest increase in the risk of PH[

28]. However, this increased risk is outweighed by the substantial benefits of surfactant administration in reducing mortality in preterm infant with severe RDS. In a comparative study, the incidence of PH was significantly higher in infants treated with poractant-alpha (200 mg/kg) than in those receiving beractant (100 mg/kg) (14.3% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.038)[

29]. Similarly, Ahmad

et al. reported that newborns with PH had greater cumulative exposure to surfactant therapy, particularly poractant alfa compared to matched controls[

14]. Earlier studies on poractant alfa did not demonstrate this association[

30,

31], likely due to the limited inclusion of extremely preterm infant (23 or 24 weeks’ gestation) —those at the highest risk for PH. Surfactant may also interfere with the coagulation cascade. An in vitro study by Strauss

et al., showed that higher surfactant concentrations were associated with a trend toward prolonged clotting time and reduced clot strength. While the findings suggest a potential exacerbation of bleeding, the study was conducted in adult populations, and it remains uncertain whether it can be extrapolated to the neonatal population [

32].

Finally, mechanical ventilation can also exacerbate to the risk of PH. High airway pressure and excessive tidal volume can cause alveolar overdistension, leading to capillary rupture through volutrauma and barotrauma. Additionally, oxygen-induced lung injury can amplify pulmonary vascular stress, leading to endothelial damage and increased capillary permeability[

33].

4.2. Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) and Pulmonary Over Circulation

The contribution of a patent ductus arteriosus to the pathogenesis of pulmonary hemorrhage remains controversial. In the immediate postnatal life, the physiological drop in PVR driven by birth, surfactant therapy with fluctuations in airway pressure, oxygen exposure, hypocapnia, and use of vasodilatory agent such as iNO and opiods – may facilitate left-to-right shunting through an unrestrictive PDA, overwhelming the fragile pulmonary vascular bed. This shunt exposes the immature pulmonary vasculature to systemic pressure and elevated blood flow (increased pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio [Qp:Qs]) potentially exacerbating pulmonary edema and the risk of capillary rupture [

4,

24]. It is not clear if early extubation after surfactant therapy (INSURE) or less invasive surfactant administration (LISA) are associated with higher incidence of PH compared to continued mechanical ventilation after surfactant administration. Centers that use high frequency ventilation and early hemodynamic screening for PDA report lower incidence of PH (figure 3).

Despite these theoretical concerns, clinical trials have yielded conflicting evidence regarding the role of PDA in PH. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of infants <29 weeks, early indomethacin administration significantly reduced PH in the first 72 hours (1% vs. 21%), but not over the study period (9% vs. 23%, p=0.07)[

34]. The observed early benefit may reflect direct pulmonary vasoconstrictive effect of NSAIDs[

35], or anti-angiogenic properties[

36] rather than PDA constriction itself.

Further evidence challenges the centrality of the PDA in PH pathogenesis. The Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TIPP) found no difference in PH incidence between infants receiving prophylactic indomethacin (15%) and placebo (16%)[

37]. In a recent cohort study using a conservative PDA approach (no NSAIDs, acetaminophen, surgical ligation, or catheter-based closure), PH rates were low - 6% in preterm infants born <26 weeks of GA (n=130) and 7% in those born between 26 and 28+6 weeks (n=84)[

38]. Similarly, the BeNeDuctus trial reported a PH rate of 3% in the expectant management group versus 1% in the ibuprofen group[

39]. Notably, this trial included a true non-intervention control group, with only one participant in the expectant group receiving open-label treatment (ibuprofen). These findings suggest that PDA might contribute to the pathogenesis of PH but challenges the hypothesis that it is a primary driver of that. Instead, PH appears to be more strongly influenced by intrinsic factors related to the immature pulmonary vascular bed and pulmonary venous drainage along with disruption of alveolar epithelial barrier, rather than the persistence of ductal shunting.

4.3. Stress Failure of Pulmonary Capillaries

Stress failure of pulmonary capillaries leads to the disruption of the endothelial barrier, allowing hemorrhagic fluid to leak into the alveoli. This process is driven by three primary forces: (1) circumferential tension within the capillary wall, caused by transmural pressure across the capillary; (2) surface tension within the alveoli, which stabilizes the bulging capillaries; and (3) longitudinal tension in the alveoli, generated during lung inflation[

4,

40]. Sudden reductions in PVR, venous congestion, or left heart dysfunction can abruptly alter pulmonary vascular flow, subjecting the fragile capillary beds of preterm infants to excessive mechanical stress. This increased stress can ultimately result in capillary rupture and hemorrhage (

Figure 3 A-C).

4.4. Left Ventricular Stiffness and Diastolic Properties

Emerging evidence suggests that cardiac function and stress-velocity relationship, a surrogate marker of myocardial workload and afterload mismatch, may play a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) in preterm infants [

41] The stress-velocity relationship reflects the dynamic interaction between myocardial contractility and wall stress, integrating both systemic vascular resistance and ventricular performance. In the transitional period, preterm infants with immature myocardium and labile hemodynamics are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in afterload. A sudden increase in systemic vascular resistance, such as that caused by vasopressor use, can disrupt the normal stress-velocity relationship of the immature myocardium. This afterload-intolerant state impairs left ventricular performance, leading to elevated left atrial and pulmonary venous pressures. The resulting capillary stress predisposes fragile pulmonary vessels to leakage and hemorrhage. This mechanism is analogous to cerebral vulnerability seen in intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH).[

41,

42] Stress-velocity relationship may serve as a hemodynamic biomarker linking ventricular performance to pulmonary capillary integrity, highlighting the need for careful modulation of cardiovascular support in extremely low birth weight infants.

High-risk populations such as infants with intrauterine growth restriction due to placental insufficiency[

42], often exhibit systemic vascular stiffness and compromised LV compliance[

43,

44]. Similarly, neonates with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) may present with LV hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction and elevated LA pressure. In these instances, the transpulmonary pressure gradient is reduced, promoting post-capillary congestion, and increasing the possibility of capillary rupture and hemorrhage.

4.5. Genetic Factors

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), or Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, is a rare but autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multisystem telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). While adult complications are well-documented, neonatal presentations are rare and limited to case reports. In children, HHT typically presents with cyanosis, digital clubbing, and dyspnea, with or without visible telangiectasias. PH is uncommon in early life and typically emerges later due to progressive AVMs or bronchial angiodysplasia. The pathogenesis of PH in HHT is linked to impaired vascular integrity, driven by dysregulated transforming growth factor-β signaling, which disrupts endothelial cell function, and extracellular matrix composition[

45]. Although a rare condition, HHT and other genetic disorders should be considered, especially in the context of familial history, due to their potential to predispose to vascular integrity[

20].

Another rare hereditary bleeding disorders such as hemophilia, which follows an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern, may also present atypically with PH as an initial symptom. Pace et al. reported a case involving a premature neonate from a monochorionic-diamniotic twin gestation who developed severe, life-threatening PH as the first clinical indication of hemophilia B, despite an absence of any family history of bleeding disorders.[

46]

4.6. Infection and Sepsis

In neonates with overwhelming sepsis - particularly Gram-negative sepsis - PH may result from profound microvascular injury and inflammation. Endotoxin release activates mononuclear phagocytes, stimulating the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn trigger neutrophils and T-cells to release secondary inflammatory mediators. This inflammatory surge disrupts endothelial integrity and increases pulmonary capillary permeability, heightening the risk of PH[

17]. Additionally, sepsis induces a systemic inflammatory response that disrupts normal coagulation pathways, increasing the risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Case reports have also suggested associations between PH and conditions such as coxsackievirus infection, necrotizing enterocolitis, and early-onset sepsis, although data remain limited[

14,

47,

48]. In preterm infants with immature pulmonary vasculature, the synergy between sepsis-induced microvascular permeability, endothelial damage, coagulopathy, and capillary fragility created a critical environment that highly conducive to PH[

17]. Sepsis is a common cause of pulmonary hemorrhage in low-resource settings.

4.7. Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR)

FGR is associated with an increased risk of PH, likely due to a combination of coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction and cardiovascular dysfunction. Impaired coagulation in these infants may involve reduced levels of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors, essential for coagulation. Thrombocytopenia is frequently observed, , particularly in cases associated with congenital infections such as cytomegalovirus. While the exact etiology of this coagulopathy remains unclear, antenatal liver hypoxia has been suggested as a contributing factor, potentially due to impaired production of clotting factors[

49]. Cardiac dysfunction may also compound this risk. Autopsy studies by Takahashi et al. in FGR infants with PH and heart failure, revealed myocardial fiber hypoplasia and depleted glycogen stores - findings indicative of chronic hypoxia and malnutrition in utero rather than acute ischemia. As a result, FGR infants may experience compromised cardiac function after birth, struggling with both left and right ventricular dysfunction[

50]. In turn, impaired cardiac function and elevated left atrial pressure can exacerbate pulmonary venous congestion, contributing to the pathogenesis of PH. (

Figure 4)

4.8. Other Conditions Possibly Associated with PH

Congenital heart disease (CHD) associated with pulmonary hypertension presents a paradoxical state marked by both thrombotic and bleeding tendencies[

51]. CHD is implicated in 30–40% of PH cases, underscoring its clinical relevance[

52,

53].

In asphyxiated neonates, left ventricular failure and the subsequent increase in pulmonary capillary pressure are key hemodynamic contributor[

19] to PH. Asphyxia leads to bradycardia, acidosis, and impaired myocardial contractility due to hypoperfusion and ischemia[

54]. This cascade elevates pulmonary venous pressures, increasing the risk of capillary stress failure and PH. Moreover, neonates with perinatal asphyxia frequently exhibit evidence of coagulopathy, that may increase the risk of PH.[

55]

Neonatal hypothermia has also been associated with PH likely through platelet dysfunction, resulting in thrombocytopenia or decreased response, which may persist or even accelerate during rewarming. If a similar process occurs in vivo, it may compromise hemostasis and contribute to hemorrhagic complications [

56].

Coagulation factors also play an important role in PH. Interestingly, coagulation levels are physiologically lower in neonates, with even more pronounced deficiencies observed in preterm infants. A study from Pal et al. has demonstrated that these factors gradually mature and typically reach adult levels by approximately six months of age.[

57]

In addition, coagulation disorders are frequently observed in neonates with PH and may exacerbate the condition[

4,

19,

58]. Carolis et al. suggested that hypocoagulability is a key risk factor strongly associated with PH. This is supported by findings that neonates with PH more frequently exhibit thrombocytopenia and abnormal coagulation test results compared to those without PH. These infants also show increased rates of bleeding from other sites, including umbilical bleeding, widespread oozing, and bruising[

3]. In a study by Yum et al. prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) was associated with worse survival, and platelet count influenced the interval between PH onset and mortality[

19] . Although activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) values remained within normal range, they were predictive of adverse outcomes in the context of DIC.

These findings highlight the multifactorial nature of PH in neonates, where cardiovascular compromise, coagulopathy, and systemic stressors converge to an overwhelmed pulmonary integrity.

5. Protective Factors

5.1. Antenatal Glucocorticoids

Berger et al. reported that maternal administration of a complete course of antenatal glucocorticoids was associated with a reduced risk of PH compared to no glucocorticoids or an incomplete course[

19]. This protective effect is likely due to the role of antenatal steroids in promoting lung maturation, enhancing surfactant production, and stabilizing the pulmonary vasculature, thereby reducing the risk of capillary stress failure and hemorrhage in preterm infants.

5.2. Prophylactic Indomethacin

The Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterm (TIPP) demonstrated that prophylactic indomethacin did not reduce the overall incidence of PH. However, when analyzing its effect on severe pulmonary hemorrhage, the study found that it was associated with a lower incidence of early severe PH (within the first week of life)[

59]. Despite this early benefit, its effectiveness in preventing late-onset severe PH (beyond the first week of life) was significantly reduced, suggesting that other mechanisms, beyond PDA-related hemodynamics, contribute to the pathogenesis of pulmonary hemorrhage in preterm infants [

59].

Table 1.

Risk and Protective factors of Pulmonary Hemorrhage.

Table 1.

Risk and Protective factors of Pulmonary Hemorrhage.

| Risk Factors |

Protective Factors |

Respiratory distress syndrome- Sudden drop of PVR after surfactant therapy and pressure from mechanical ventilator leads to capillary trauma

Patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary over circulation- Pulmonary edema and capillary rupture

Stress failure of pulmonary capillaries- Disruption of the endothelial barrier, allowing hemorrhagic fluid to leak into the alveoli.

Left ventricular stiffness and diastolic properties- Myocardial workload and afterload mismatch

Genetic factors- HHT: impaired vascular integrity, hemophilia: bleeding disorder

Infection and sepsis- Profound microvascular injury and inflammation.

Fetal growth restriction- Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction and cardiovascular dysfunction.

Possible factors- Congenital heart disease, asphyxia, hypothermia, lower coagulation factors in neonatal population |

Antenatal glucocorticoids- Enhancing surfactant production, and stabilizing the pulmonary vasculature

Prophylactic Indomethacin- Lower incidence of early severe PH (within the first week of life)

|

6. Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PH in neonates is often urgent, requiring rapid recognition and intervention due to its association with sudden clinical deterioration. It is primarily based on clinical presentation, including acute respiratory distress, bloody tracheal secretions, and hypoxemia, supported by radiological findings such as diffuse alveolar infiltrates on chest radiography. Laboratory evaluations, including coagulation profiles and markers of inflammation, can help identify underlying contributing factors. In recent years, lung ultrasound (LUS) has emerged as a valuable, non-invasive diagnostic tool for PH. LUS can detect increased pulmonary echogenicity, consolidations, and alveolar-interstitial syndrome, aiding in the early identification of PH in the clinical context[

60,

61,

62].

6.1. Clinical Presentation

PH typically occurs in the first 48 to 72 hours of life. The hallmark clinical sign is the sudden appearance of frothy, pink-tinged secretions or visible bleeding from the endotracheal tube. In infants receiving non-invasive ventilation, blood may be observed in the posterior pharynx, or it may be detected in gastric secretions. This presentation is often accompanied by a rapid increase in oxygen requirements and ventilatory support, signaling significant pulmonary compromise that requires urgent intervention. Lung auscultation often reveals coarse breath sounds and reduced air entry, reflecting pulmonary congestion and alveolar flooding. As PH progresses, oxygen requirements escalate[

24], and if left untreated, may lead to apnea, widespread pallor, cyanosis, bradycardia, and hypotension due to hypovolemic shock. In severe cases, rapid cardiopulmonary collapse can occur[

1]. Given the acute and life-threatening nature of PH, clinicians must promptly recognize its onset, particularly in neonates with predisposing factors such as surfactant therapy, PDA, FGR, and coagulopathies. A sudden and unexplained clinical deterioration in a high-risk neonate should immediately raise suspicion for PH and prompt urgent evaluation and intervention[

4,

13,

24,

27].

6.2. Laboratory Diagnosis

Laboratory findings often reflect both the severity of blood loss and any underlying coagulopathy. A complete blood count (CBC) typically reveals a sharp drop in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels due to ongoing pulmonary bleeding, which may necessitate urgent blood transfusions to restore oxygen-carrying capacity. Coagulation studies often demonstrate abnormalities, particularly in neonates with DIC or other coagulation disorders. Prolonged PT and aPTT, along with decreased fibrinogen levels and thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction may exacerbate PH[

4]. In addition, blood gas analysis frequently shows severe hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and metabolic acidosis, indicative of impaired gas exchange due to alveolar flooding and ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

6.3. Radiological Diagnosis

Chest radiography findings are often nonspecific and vary depending on the severity and timing of the hemorrhage. In mild cases, imaging may reveal fluffy opacities or focal ground-glass opacities, reflecting localized alveolar hemorrhage. As the hemorrhage progresses, the opacities may become more diffuse, resembling worsening pulmonary edema. In severe cases, extensive alveolar flooding can lead to a complete "white-out" appearance, indicating significant impairment of gas exchange[

4]. However, these radiographic findings are not pathognomonic and can overlap with conditions such as RDS, pneumonia, or pulmonary edema, making clinical correlation essential for accurate diagnosis.

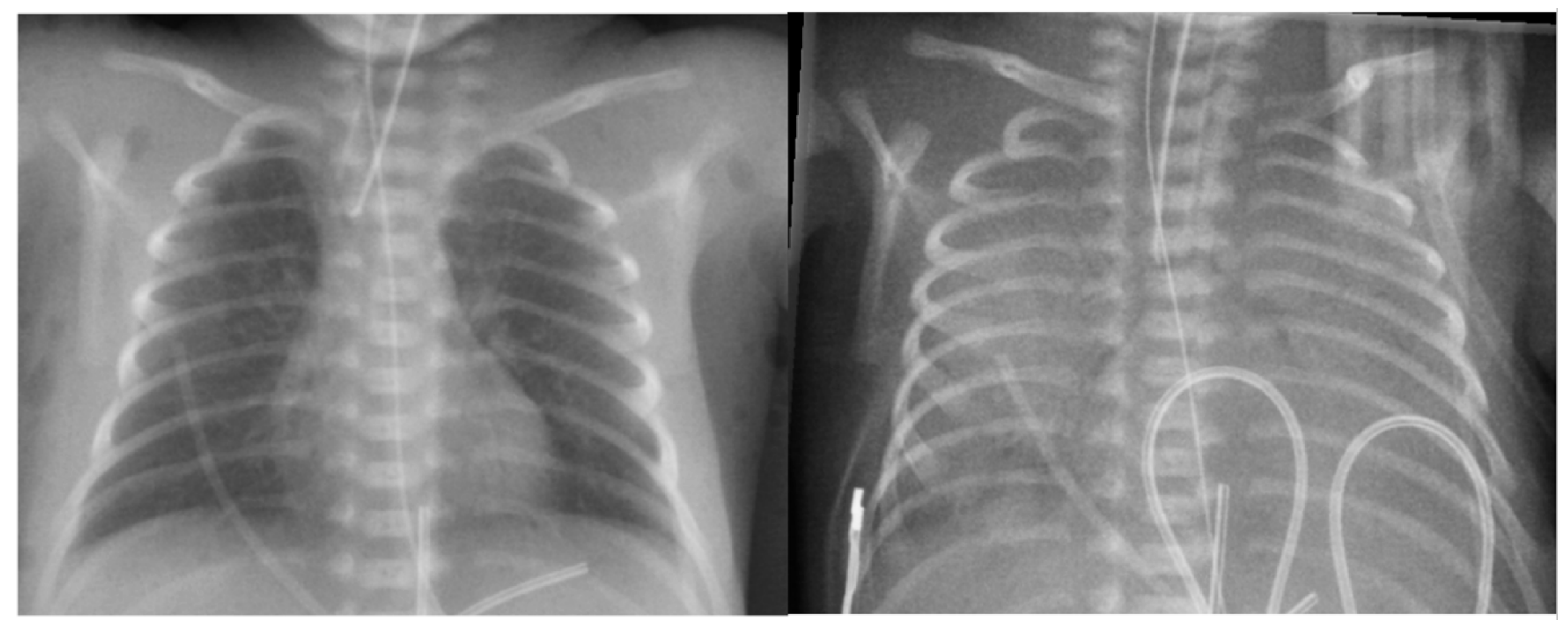

Figure 5.

Chest x-ray of a premature baby with pulmonary hemorrhage showing bilateral opacities.

Figure 5.

Chest x-ray of a premature baby with pulmonary hemorrhage showing bilateral opacities.

Figure 6.

Chest x-ray of the baby with massive pulmonary hemorrhage. Left: Before pulmonary hemorrhage. Right: After massive pulmonary hemorrhage: “white out” lungs appearance due to extensive pulmonary flooding.

Figure 6.

Chest x-ray of the baby with massive pulmonary hemorrhage. Left: Before pulmonary hemorrhage. Right: After massive pulmonary hemorrhage: “white out” lungs appearance due to extensive pulmonary flooding.

6.4. Lung Ultrasound in the Evaluation of PH

LUS is increasingly recognized as a potential tool for pulmonary conditions in neonates, including PH. As a non-invasive, radiation-free, and bedside-performable technique, LUS is particularly advantageous for critically ill neonates requiring frequent assessment. Studies have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for detecting various pulmonary pathologies. A study by Ren

et al. highlighted the reliability of LUS for recognizing PH[

62].

Characteristic LUS findings associated with PH include lung consolidation with a shred sign at the edges of the affected area, air or fluid bronchograms, and atelectasis, reflecting significant alveolar involvement. Additionally, abnormalities such as disrupted pleural lines, absence of A-lines, and pleural effusion may be observed, with severe cases showing real-time evidence of red blood cell destruction and fibrous protein deposition, appearing as floating objects within the pleural fluid. Furthermore, alveolar-interstitial syndrome, characterized by the presence of more than three B-lines per intercostal space, suggests lung edema, which can be a consequence of hemorrhagic lung injury. LUS has the potential to enhance early detection and management of PH.

6.5. Echocardiography Assessment

6.5.1. Patent Ductus Arteriosus

A study by Kluckow

et al. examined echocardiographic findings in preterm infants around the time of PH and identified significant patterns associated with the condition[

63]. Infants who developed PH had significantly larger PDA diameters, (>1.5 mm), with a predominantly left-to-right shunt. Additionally, these infants exhibited absent or retrograde diastolic flow in the post-ductal descending aorta, suggesting steal effect from the systemic circulation and increased Qp:Qs.

6.5.2. Pulmonary Hypertension

Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) is approved for term and near-term infants with hypoxic-ischemic failure but has not demonstrated consistent outcome benefits in preterm infants. [

64] [

65]. However, some studies suggest potential oxygenation improvement in select preterm subgroups – especially those with pulmonary hypoplasia, prolonged rupture of membranes, or early PPHN[

66]. Observational studies have also indicated that an acute response to iNO in preterm infants is associated with improved survival, supporting the rationale for a short therapeutic trial in this population[

67]. PPHN or acute pulmonary hypertension frequently complicate severe RDS in very preterm infants, and iNO administration was associated to oxygenation improvements and survival[

68].

iNO may reduce pulmonary vascular resistance rapidly, leading to an abrupt increase in pulmonary blood flow, placing excessive stress on the immature and fragile capillary network, increasing the risk of capillary rupture and PH. Moreover, abrupt iNO withdrawal may trigger rebound pulmonary hypertension, further stressing the pulmonary vasculature[

69]. PH can perpetuate pulmonary hypertension through inflammation, airway obstruction, and microvasculature damage, all contributing to elevated PVR. Hence, iNO should be used cautiously in this group of patients, only in infants with confirmed pulmonary hypertension on echocardiography. Serial echoes should perform to guide the duration of iNO and it should be weaned off as soon as possible when pulmonary hypertension is resolved.

Echocardiographic is essential to assess pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), right ventricular (RV) function, and systemic blood flow (SBF)[

70]. Key parameters include estimate of pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), RV function, and systemic blood flow (SBF). PAP assessment should include the analysis of tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity and PDA shunt velocity, when present, to estimate right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) and PAP. Septal wall morphology in the parasternal short-axis view and systolic eccentricity index (EI) provides an objective measure of septal flattening. RV function must be assessed by objective and validated methods, including tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), fractional area change (FAC), Doppler tissue imaging, and deformation imaging[

71]. These echocardiographic assessments enable timely diagnosis and tailored of PH-associated pulmonary hypertension in neonates.

6.5.3. Systemic Hypotension

Pulmonary hemorrhage in neonates is often associated with hypotension, driven by blood loss, reduced preload, hypoxia-induced myocardial dysfunction, and impaired contractility. Hypovolemia and systemic hypoxia, can compromise myocardial oxygenation, further reducing cardiac output. Additionally, elevated mean airway pressure (MAP), often used in PH management, further compromise venous return and preload, exacerbating hypotension. The increased intra-thoracic pressure can elevate central venous pressure and predispose to germinal matrix hemorrhage in preterm infants with fragile cerebral vasculature.

Increased intrathoracic pressure also raises RV afterload, which may impair RV function and exacerbate adverse RV-LV interactions. Echocardiographic assessment is essential to guide clinical management. Key assessments include:

Assessment of biventricular systolic function (impact of hemorrhage on contractility).

Evaluation of preload and afterload (volume status and vascular resistance).

Characterization of intra- and extracardiac shunts (PDA and atrial shunt), influencing pulmonary and systemic flow.

Chamber morphology (LV and RV size, hypertrophy, dilation) secondary to volume or pressure overload.

Exclusion or inclusion of a diagnosis of congenital heart disease, which may present with hemodynamic instability and contribute to PH[

71].

7. Management

Effective management of neonatal PH requires a rapid, multidisciplinary approach focused on stabilizing respiratory and hemodynamic status, preventing further bleeding, and treating underlying conditions. Key objectives include optimizing oxygenation, minimizing additional pulmonary injury, correcting hemodynamic instability, and managing coagulopathies. (Figure 7) Interventions must be prompt and tailored to the infant’s condition, often requiring a combination of strategies related to hemorrhage severity and comorbidities.

7.1. Resuscitation and Stabilization

Prompt resuscitation and stabilization are critical. Following standard neonatal resuscitation protocols, hemorrhagic secretions should be carefully cleared from the airway using gentle suctioning, ensuring that the airway remains patent while minimizing additional trauma. If necessary, endotracheal intubation should be performed to secure the airway and facilitate effective ventilation. Gentle suctioning is essential for removing blood clots that may obstruct airflow or impair visualization of the airway anatomy; however, excessive suctioning and frequent disconnection from the ventilator should be avoided to prevent further mucosal injury or exacerbation of bleeding[

24].

7.2. Mechanical Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation is central to the management of PH, aimed to support oxygenation while minimizing further lung injury. Strategies focus on maintaining adequate oxygenation, prevent hypoxemia and acidosis, reduce the risk of barotrauma and volutrauma. And avoiding excessive pressures that may worsen capillary stress.

High-Frequency Oscillatory Ventilation (HFOV): HFOV is often favored over conventional mechanical ventilation (CMV), although no RCT has confirmed its superiority. Several studies have demonstrated that HFOV can significantly reduce FiO₂ requirements and improve the oxygenation index in critically ill neonates with massive PH and respiratory failure[

8,

72,

73]. AlKharfy et al. further reported that HFOV effectively promotes adequate ventilation [

74]. Additionally, a study by Duval et al. highlighted the potential life-saving benefits of HFOV in cases of severe PH, showing rapid improvement in oxygenation[

75]. Its sustained high distending pressures, which may tamponade alveolar bleeding, reduce pulmonary blood flow and limit further capillary rupture makes it a valuable lung-protective strategy.

Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP): Trompeter et al. demonstrated that increasing MAP through PEEP optimization alongside acidosis correction, morphine administration, and diuretic (furosemide) can stabilize the hemorrhage[

5]. Similarly, Bhandari et al. reported benefit from combining increased MAP with endotracheal epinephrine (1:10,000 at 0.1 mL/kg) and/or 4% cocaine (4 mL/kg)[

76]. These strategies aim to improve lung recruitment, stabilize alveolar capillary membranes, and mitigate further hemorrhagic episodes by reducing excessive pulmonary capillary pressure and improving gas exchange.

7.3. Surfactant Therapy

While surfactant therapy has been implicated as a potential trigger for PH in some infants, it can be beneficial in most neonates who experience PH once the acute bleeding phase has stabilized[

33,

77]. Additional doses may be administered post-hemorrhage to enhance lung recruitment and improve gas exchange since alveolar blood inactivates surfactant. Pandit

et al. reported an improvement in the oxygenation index following surfactant administration[

78], while Amizuka

et al. demonstrated a positive effect, showing that 82% of cases achieved a ventilatory index of <0.047 within one hour of surfactant administration. Moreover, no neonates in this study developed BPD or experienced mortality, further suggesting a role for surfactant in the recovery after PH[

79].

7.4. Blood Product Transfusions and Coagulation Support

Coagulopathies are commonly associated with PH, making hemodynamic stabilization and correction of clotting abnormalities essential in its management. Blood products are frequently used as adjunctive therapies to replace lost blood volume and restore coagulation function[

1,

78]. The British Society of Haematology guidelines recommend maintaining hemoglobin levels above 120 g/L in preterm infants requiring ventilatory support or experiencing active bleeding. Additionally, platelet counts should be kept above 50-100 × 10⁹/L in cases of active hemorrhage. Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) may be beneficial for neonates with clinically significant bleeding or abnormal coagulation profiles, characterized by prolonged PT or aPTT relative to gestational and postnatal age norms. If PT is elevated, an additional dose of vitamin K may be administered, and fibrinogen levels should be maintained above 1.0 g/dL through fibrinogen supplementation[

80]. In addition, several pharmacologic agents can be used to promote hemostasis and stabilize bleeding.

Recombinant Factor VII (rFVIIa): A few case reports have documented the use of intravenous recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) in neonates with life-threatening PH, demonstrating positive outcomes. rFVIIa acts by directly activating the extrinsic coagulation pathway, leading to thrombin generation and fibrin clot formation, which may help control severe bleeding. However, further prospective studies are needed to establish the optimal dosage, timing of administration, and overall efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rFVIIa in both preterm and term neonates[

81].

Hemocoagulase: Some studies have reported the use of hemocoagulase, a snake venom-derived enzyme, as a hemostatic agent in neonatal hemorrhage. Hemocoagulase promotes blood coagulation by activating prothrombin and accelerating fibrin clot formation. While its use in neonates remains limited, preliminary reports suggest its potential efficacy in controlling pulmonary hemorrhage. Further research is needed to evaluate its safety, optimal dosing, and overall effectiveness in neonatal care[

82,

83,

84].

Antifibrinolytic Agents: Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic agent that prevents fibrin clot degradation by inhibiting plasminogen activation. It has been used intravenously in some cases of neonatal hemorrhage, including PH, to stabilize existing clots and reduce ongoing bleeding[

85]. While TXA has shown promise in adult and pediatric populations[

86], its use in neonates remains limited, and further research is needed to establish its safety, optimal dosing, and overall efficacy in preterm and critically ill infants.

Ankaferd Blood Stopper (ABS): Two cases from a report described the successful use of ABS in treating massive PH in neonates. The first case involved a term male newborn at 38 3/7 weeks of gestation, while the second case involved a late preterm infant at 33 6/7 weeks. Both neonates experienced severe PH, and ABS was administered directly via the endotracheal tube. In both cases, the hemorrhage ceased immediately following ABS administration, highlighting its potential as an emergency hemostatic intervention in neonatal PH. However, further studies are necessary to evaluate its safety, optimal dosing, and broader clinical application, especially in premature infants where there is no reported evidence or experience [

87].

7.5. Endotracheal Epinephrine

Although not a standard therapy, endotracheal epinephrine may be considered in life-threatening cases PH, particularly during resuscitation or when bleeding is refractory. Epinephrine administered via the endotracheal tube (ETT) induces localized pulmonary vasoconstriction to help control the hemorrhage. While effective, this approach carries potential risks, including airway or vocal cord ischemia, local tissue necrosis, arrhythmias, systemic vasoconstriction, hyperglycemia, lactic acidosis, and hypertension. A study by Chen

et al. reported significant higher survival (80% vs. 18.2%) with direct intratracheal catheter administration (1:10,000 epinephrine, dose 0.3 to 1.0 mL/kg (0.03 to 0.1 mg/kg) compared to ETT connector delivery [

17]. However, further studies are needed to define optimal dosing and safety in this context.

7.6. Tolazoline

In one case report, tolazoline was administered to a full-term newborn with neonatal encephalopathy and pulmonary hemorrhage. The infant received a 6 mg bolus followed by an intravenous infusion of tolazoline, leading to a rapid improvement in oxygenation within three minutes. This improvement facilitated the discontinuation of ventilatory support 16 hours later. The newborn ultimately survived without any apparent long-term disability, suggesting a potential role for tolazoline in the management of severe neonatal pulmonary hypertension. However, further studies are needed to assess its safety and efficacy in broader neonatal populations[

88].

8. Prognosis

The prognosis of PH in preterm infants depends on its severity and associated complications.[

14] Chen

et al. reported a significantly higher incidence of severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH; grades 3 or 4) in infants with massive PH, with all affected neonates developing IVH either concurrently or shortly after. The pathogenesis of IVH is complex and multifactorial and has been described earlier [

17]. Similarly, Pandit

et al. found that neonates with PH were three times more likely to develop major IVH[

11]. Concomitant, those infants experiencing severe PH have a significantly higher risk of death or neurodevelopmental impairment among survivors[

59].

8.1. Future Directions

Despite progress, many gaps remain in our understanding and management of PH in preterm infants. The complex interplay between hemodynamic, coagulation, and genetic predisposition is not fully elucidated. Risk factors such as RDS, PDA, and surfactant use need better characterization, especially in combination. Diagnostic tool like LUS and echocardiography show promise but lack standardization implementation. Additional predictive strategies for PH must be explored such as heart rate variability analysis or artificial intelligence models integrating multiple physiological signals, and near-infrared spectroscopy by establishing normative values specific to preterm populations and assessing their impact on clinical decision-making and outcomes. Therapeutic strategies also warrant further investigation. While HFOV and surfactant therapy are commonly utilized, optimal timing, dosing, and long-term effects remain unclear. Adjunctive therapies - antifibrinolytics, rFVII, hemocoagulase or ABS - require further validation. Preventive approaches, including antenatal corticosteroids and prophylactic indomethacin, also warrant targeted trials. Finally, the long-term impact of PH on survivors remains poorly characterized. Future studies should address neurodevelopmental and cardiopulmonary sequelae, and the broader economic and psychosocial burden on families. Understanding the trajectory of PH survivors is crucial to refining follow-up strategies and optimizing long-term care. Addressing these gaps will be essential to improving both survival and short- and long-term outcomes in this vulnerable population.

8.2. Conclusion

PH in preterm infants remains a major clinical challenge due to its complex and multifactorial pathogenesis. Despite advancements in neonatal care, PH continues to be associated with high mortality and severe long-term neurodevelopmental impairment. Emerging evidence highlights the importance of early recognition through clinical signs, laboratory markers, and imaging, particularly lung ultrasound. Management strategies such as high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, higher PEEP levels, surfactant administration, and hemostatic support play key roles during acute care. Future research should focus on refining preventive strategies, validate early diagnosis tools, and explore novel therapies to improve survival and long-term outcomes in this high-risk population.

Table 2.

Management of Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Neonates.

Table 2.

Management of Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Neonates.

| Initial Assessment and Stabilization |

- Assess for clinical signs of PH (bloody secretions, hypoxemia, hypotension). Exclude traumatic cause of bleeding (position of ETT).

- Consider early intubation and initiation of mechanical ventilation if not already intubated.

- Perform chest radiography and consider lung ultrasound to assess for alveolar infiltrates.

- Monitor continuously with pulse oximetry, blood pressure measurement, and blood gas analysis. |

| Mechanical Ventilation |

- Secure airway

- Increase PEEP level to prevent further hemorrhage and improve oxygenation.

- Initiate or transition to HFOV to minimize alveolar collapse and optimize gas exchange.

- Employ a gentle ventilation strategy to reduce barotrauma and protect fragile lung tissue. |

| Surfactant Therapy |

- Administer additional surfactant doses once the bleeding has stabilized.

- Monitor for hemodynamic changes following surfactant administration. |

| Blood Product Transfusions |

- Administer packed red blood cells to maintain hemoglobin levels.

- Administer fresh frozen plasma (FFP) for coagulation factor replacement in cases of coagulopathy.

- Give cryoprecipitate to replenish fibrinogen and other clotting factors if levels are low.

- Platelet transfusions if thrombocytopenia is present. |

| Coagulation Support |

- Administer vitamin K if ongoing DIC. |

| Endotracheal epinephrine |

- Consider administer endotracheal epinephrine when persistent and uncontrolled bleeding or during the resuscitation. |

| Inotropic drug or vasopressor |

- Consider inotropic drug or vasopressor to help stabilize the hemodynamic status. |

| Steroids |

- Consider steroid in case of potential adrenal insufficiency. |

Author Contributions

Literature review, S.S., Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.L., A.V., A.H., N.N., Y.S., C.S., T.C.; Visualization, G.A. and S.L.; Supervision, G.A. and S.L.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barnes, M.E.; Feeney, E.; Duncan, A.; Jassim, S.; MacNamara, H.; O’Hara, J.; Refila, B.; Allen, J.; McCollum, D.; Meehan, J.; et al. Pulmonary haemorrhage in neonates: Systematic review of management. Acta Paediatrica 2022, 111, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Stork, E.; Minich, N.M.; Friedman, H.; Berlin, S.; Hack, M. Pulmonary Hemorrhage: Clinical Course and Outcomes Among Very Low-Birth-Weight Infants. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 1999, 153, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, M.P.; Romagnoli, C.; Cafforio, C.; Piersigilli, F.; Papacci, P.; Vento, G.; Tortorolo, G. Pulmonary haemorrhage in infants with gestational age of less than 30 weeks. Eur J Pediatr 1998, 157, 1037–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahr, R.A.; Ashfaq, A.; Marron-Corwin, M. Neonatal Pulmonary Hemorrhage. NeoReviews 2012, 13, e302–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, R.; Yu, V.Y.; Aynsley-Green, A.; Roberton, N.R. Massive pulmonary haemorrhage in the newborn infant. Arch Dis Child 1975, 50, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houten, J.; Long, W.; Mullett, M.; Finer, N.; Derleth, D.; McMurray, B.; Peliowski, A.; Walker, D.; Wold, D.; Sankaran, K.; et al. Pulmonary hemorrhage in premature infants after treatment with synthetic surfactant: an autopsy evaluation. The American Exosurf Neonatal Study Group I, and the Canadian Exosurf Neonatal Study Group. J Pediatr 1992, 120, S40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappin, A.; Shenker, N.; Hack, M.; Redline, R.W. Extensive intraalveolar pulmonary hemorrhage in infants dying after surfactant therapy. The Journal of Pediatrics 1994, 124, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.Y.; Chang, Y.S.; Park, W.S. Massive pulmonary hemorrhage in newborn infants successfully treated with high frequency oscillatory ventilation. J Korean Med Sci 1998, 13, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.Y. Massive pulmonary hemorrhage in neonatal infection. Can Med Assoc J 1976, 114, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, E.R.; Subhedar, N.V. Pulmonary haemorrhage in preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr 2000, 159, 870–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.B.; O'Brien, K.; Asztalos, E.; Colucci, E.; Dunn, M.S. Outcome following pulmonary haemorrhage in very low birthweight neonates treated with surfactant. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999, 81, F40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeh-Vered, T.; Rosenberg, N.; Morag, I.; Berg, A.A.; Kenet, G.; Strauss, T. A Proposed Role of Surfactant in Platelet Function and Treatment of Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Preterm and Term Infants. Acta Haematol 2018, 140, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yum, S.K.; Moon, C.J.; Youn, Y.A.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Sung, I.K. Risk factor profile of massive pulmonary haemorrhage in neonates: the impact on survival studied in a tertiary care centre. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016, 29, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, K.A.; Bennett, M.M.; Ahmad, S.F.; Clark, R.H.; Tolia, V.N. Morbidity and mortality with early pulmonary haemorrhage in preterm neonates. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2019, 104, F63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezmu, A.M.; Tefera, E.; Mochankana, K.; Imran, F.; Joel, D.; Pelaelo, I.; Nakstad, B. Pulmonary hemorrhage and associated risk factors among newborns admitted to a tertiary level neonatal unit in Botswana. Front Pediatr 2023, 11, 1171223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, H.; Ye, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z. Exploring prediction model and survival strategies for pulmonary hemorrhage in premature infants: a single-center, retrospective study. Translational Pediatrics 2021, 10, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, H.P.; Lin, S.M.; Chang, J.T.; Hsieh, K.S.; Huang, F.K.; Chiou, Y.H.; Huang, Y.F.; Taiwan Premature Infant Development Collaborative Study, G. Pulmonary hemorrhage in very low-birthweight infants: risk factors and management. Pediatr Int 2012, 54, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, J.L.; Marston, L.; Marlow, N.; Calvert, S.A.; Greenough, A. Neonatal and infant outcome in boys and girls born very prematurely. Pediatr Res 2012, 71, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.M.; Allred, E.N.; Van Marter, L.J. Antecedents of clinically significant pulmonary hemorrhage among newborn infants. J Perinatol 2000, 20, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gludovacz, K.; Vlasselaer, J.; Mesens, T.; Van Holsbeke, C.; Van Robays, J.; Gyselaers, W. Early neonatal complications from pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: case report and review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012, 25, 1494–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.H.; Carmona, F.; Martinez, F.E. Prevalence, risk factors and outcomes associated with pulmonary hemorrhage in newborns. Jornal de Pediatria 2014, 90, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.T.; Zhou, M.; Hu, X.F.; Liu, J.Q. Perinatal risk factors for pulmonary hemorrhage in extremely low-birth-weight infants. World J Pediatr 2020, 16, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxonhouse, M.A.; Sola, M.C. Platelet function in term and preterm neonates. Clinics in Perinatology 2004, 31, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welde, M.A.; Sanford, C.B.; Mangum, M.; Paschal, C.; Jnah, A.J. Pulmonary Hemorrhage in the Neonate. Neonatal Netw 2021, 40, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Johnson, D.L.; Stewart, L.; Waite, K.; Elliott, D.; Wilson, J.M. Rab14 regulation of claudin-2 trafficking modulates epithelial permeability and lumen morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 2014, 25, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.W.; Su, B.H.; Lin, H.C.; Hu, P.S.; Peng, C.T.; Tsai, C.H.; Liang, W.M. Risk factors of pulmonary hemorrhage in very-low-birth-weight infants: a two-year retrospective study. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 2000, 41, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bendapudi, P.; Narasimhan, R.; Papworth, S. Causes and management of pulmonary haemorrhage in the neonate. Paediatrics and Child Health 2012, 22, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.N.; Langenberg, P. Pulmonary hemorrhage and exogenous surfactant therapy: a metaanalysis. J Pediatr 1993, 123, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.L.; Siu, K.L. Pulmonary Complications in Premature Infants Using a Beractant or Poractant for Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Perinatol 2024, 41, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, C.P.; Gefeller, O.; Groneck, P.; Laufkotter, E.; Roll, C.; Hanssler, L.; Harms, K.; Herting, E.; Boenisch, H.; Windeler, J.; et al. Randomised clinical trial of two treatment regimens of natural surfactant preparations in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1995, 72, F8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, S.B.; Beresford, M.W.; Milligan, D.W.; Shaw, N.J.; Matthews, J.N.; Fenton, A.C.; Ward Platt, M.P. Pumactant and poractant alfa for treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in neonates born at 25-29 weeks' gestation: a randomised trial. Lancet 2000, 355, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, T.; Rozenzweig, N.; Rosenberg, N.; Shenkman, B.; Livnat, T.; Morag, I.; Fruchtman, Y.; Martinowitz, U.; Kenet, G. Surfactant impairs coagulation in-vitro: A risk factor for pulmonary hemorrhage? Thrombosis Research 2013, 132, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.J.; Kohn, A. Pulmonary Hemorrhage, Transient Tachypnea and Neonatal Pneumonia. In Neonatology: A Practical Approach to Neonatal Diseases, Buonocore, G., Bracci, R., Weindling, M., Eds.; Springer Milan: Milano, 2012; pp. 455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckow, M.; Jeffery, M.; Gill, A.; Evans, N. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of early treatment of the patent ductus arteriosus. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014, 99, F99–f104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gournay, V.; Roze, J.C.; Kuster, A.; Daoud, P.; Cambonie, G.; Hascoet, J.M.; Chamboux, C.; Blanc, T.; Fichtner, C.; Savagner, C.; et al. Prophylactic ibuprofen versus placebo in very premature infants: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 364, 1939–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Walther, F.J.; Yang, C.; Wagenaar, G.T.M. Vascular and pulmonary effects of ibuprofen on neonatal lung development. Respir Res 2023, 24, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Davis, P.; Moddemann, D.; Ohlsson, A.; Roberts, R.S.; Saigal, S.; Solimano, A.; Vincer, M.; Wright, L.L. Long-term effects of indomethacin prophylaxis in extremely-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med 2001, 344, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Nunes, G.; Wutthigate, P.; Simoneau, J.; Beltempo, M.; Sant'Anna, G.M.; Altit, G. Natural evolution of the patent ductus arteriosus in the extremely premature newborn and respiratory outcomes. J Perinatol 2022, 42, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundscheid, T.; Onland, W.; Kooi, E.M.W.; Vijlbrief, D.C.; de Vries, W.B.; Dijkman, K.P.; van Kaam, A.H.; Villamor, E.; Kroon, A.A.; Visser, R.; et al. Expectant Management or Early Ibuprofen for Patent Ductus Arteriosus. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.B.; Mathieu-Costello, O. Stress failure of pulmonary capillaries: role in lung and heart disease. Lancet 1992, 340, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, K.; Kawataki, M.; Ohyama, M.; Shibasaki, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hoshino, R.; Itani, Y.; Nakazawa, M. Tailor-made circulatory management based on the stress-velocity relationship in preterm infants. J Formos Med Assoc 2013, 112, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, S.; McCoy, M.; Anderson, M.P.; Ramji, F.; Seri, I. Changes in cardiac function and cerebral blood flow in relation to peri/intraventricular hemorrhage in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr 2014, 164, 264–270.e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Änghagen, O.; Engvall, J.; Gottvall, T.; Nelson, N.; Nylander, E.; Bang, P. Developmental Differences in Left Ventricular Strain in IUGR vs. Control Children the First Three Months of Life. Pediatr Cardiol 2022, 43, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharie, G.C.; Hasmasanu, M.; Blaga, L.; Matyas, M.; Muresan, D.; Bolboaca, S.D. Cardiac left heart morphology and function in newborns with intrauterine growth restriction: relevance for long-term assessment. Med Ultrason 2019, 21, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dearborn, D.G. Pulmonary hemorrhage in infants and children. Curr Opin Pediatr 1997, 9, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, L.M.; Lee, A.Y.; Nath, S.; Alviedo, N.B. Pulmonary Hemorrhage: An Unusual Life-Threatening Presentation of Factor IX Deficiency in a Monochorionic-Diamniotic Twin Neonate. Cureus 2021, 13, e20352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbach, R.; Mandel, D.; Lubetzky, R.; Ovental, A.; Haham, A.; Halutz, O.; Grisaru-Soen, G. Pulmonary hemorrhage due to Coxsackievirus B infection-A call to raise suspicion of this important complication as an end-stage of enterovirus sepsis in preterm twin neonates. J Clin Virol 2016, 82, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollinger, C.; Steiner, L. Case 2: Respiratory Failure, Myocardial Dysfunction, and Pulmonary Hemorrhage in a Full-Term Newborn. NeoReviews 2016, 17, e282–e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotto, E.K.; Kilbride, H.W. Perinatal Outcome and Later Implications of Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006, 49, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Nishida, H.; Arai, T.; Kaneda, Y. Abnormal cardiac histology in severe intrauterine growth retardation infants. Acta Paediatr Jpn 1995, 37, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, F.; Hanna, B.D.; Zinman, R. Pulmonary complications of congenital heart disease. Paediatr Respir Rev 2012, 13, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, S.K.; Casey, A.M.; Fishman, M.P. Pulmonary hemorrhage in infancy: A 10-year single-center experience. Pediatric Pulmonology 2018, 53, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, G.T.M.; Nguyen, N.P.M.; Long, N.P.; Nguyen, D.N.; Nguyen, T.-T. Risk Factors and Outcomes of Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Preterm Infants born before 32 weeks. medRxiv 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polglase, G.R.; Ong, T.; Hillman, N.H. Cardiovascular Alterations and Multiorgan Dysfunction After Birth Asphyxia. Clin Perinatol 2016, 43, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Morishita, S. Hypercoagulability and DIC in high-risk infants. Semin Thromb Hemost 1998, 24, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, I.J. Room temperature ADP-induced first-stage hyperaggregation of human platelets: the cause of rewarming deaths by thrombocytopenia in neonatal cold injury. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1991, 8, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Curley, A.; Stanworth, S.J. Interpretation of clotting tests in the neonate. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2015, 100, F270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, V.A.; Normand, I.C.; Reynolds, E.O.; Rivers, R.P. Pathogenesis of hemorrhagic pulmonary edema and massive pulmonary hemorrhage in the newborn. Pediatrics 1973, 51, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaleh, K.; Smyth, J.A.; Roberts, R.S.; Solimano, A.; Asztalos, E.V.; Schmidt, B.; Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms, I. Prevention and 18-month outcomes of serious pulmonary hemorrhage in extremely low birth weight infants: results from the trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, F.; Yousef, N.; Migliaro, F.; Capasso, L.; De Luca, D. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in neonatology: classification into descriptive and functional applications. Pediatric Research 2021, 90, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoss, J.L.; Bazacliu, C.; Cacho, N.; De Luca, D. Lung Ultrasound in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Does It Impact Clinical Care? Children (Basel) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.L.; Fu, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xia, R.M. Lung ultrasonography to diagnose pulmonary hemorrhage of the newborn. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017, 30, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluckow, M.; Evans, N. Ductal shunting, high pulmonary blood flow, and pulmonary hemorrhage. The Journal of Pediatrics 2000, 137, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrington, K.J.; Finer, N.; Pennaforte, T.; Altit, G. Nitric oxide for respiratory failure in infants born at or near term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 1, Cd000399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrington, K.J.; Finer, N.; Pennaforte, T. Inhaled nitric oxide for respiratory failure in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 1, Cd000509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chock, V.Y.; Van Meurs, K.P.; Hintz, S.R.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Lemons, J.A.; Kendrick, D.E.; Stevenson, D.K. Inhaled nitric oxide for preterm premature rupture of membranes, oligohydramnios, and pulmonary hypoplasia. Am J Perinatol 2009, 26, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, R.; Subhedar, N.V. Nitric Oxide in Pulmonary Hypoplasia: Results from the European iNO Registry. Neonatology 2019, 116, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, C.; Corsini, I.; Cangemi, J.; Vangi, V.; Pratesi, S. Nitric oxide for the treatment of preterm infants with severe RDS and pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Pulmonol 2017, 52, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullan, D.M.; Bekker, J.M.; Johengen, M.J.; Hendricks-Munoz, K.; Gerrets, R.; Black, S.M.; Fineman, J.R. Inhaled nitric oxide-induced rebound pulmonary hypertension: role for endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001, 280, H777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijlbrief, D.C.; Benders, M.J.; Kemperman, H.; van Bel, F.; de Vries, W.B. B-type natriuretic peptide and rebound during treatment for persistent pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr 2012, 160, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.J.; Jain, A.; El-Khuffash, A.; Giesinger, R.; Weisz, D.; Freud, L.; Levy, P.T.; Bhombal, S.; de Boode, W.; Leone, T.; et al. Guidelines and Recommendations for Targeted Neonatal Echocardiography and Cardiac Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2024, 37, 171–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, M.D.; Sarnaik, A.P.; Meert, K.L.; Hasan, R.A.; Lieh-Lai, M.W. Idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage in infancy. Clinical features and management with high frequency ventilation. Chest 1996, 110, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, T.A.; Wang, C.C.; Hsieh, W.S.; Chou, H.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsao, P.N. Short-term outcome of pulmonary hemorrhage in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants. Pediatr Neonatol 2013, 54, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlKharfy, T.M. High-frequency ventilation in the management of very-low-birth-weight infants with pulmonary hemorrhage. Am J Perinatol 2004, 21, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, E.L.I.M.; Markhorst, D.G.; Ramet, J.; van Vught, A.J. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation in severe lung haemorrhage: A case study of three centres. Respiratory Medicine CME 2009, 2, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V.; Gagnon, C.; Rosenkrantz, T.; Hussain, N. Pulmonary hemorrhage in neonates of early and late gestation. J Perinat Med 1999, 27, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Ohlsson, A. Surfactant for pulmonary haemorrhage in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 2, CD005254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.B.; Dunn, M.S.; Colucci, E.A. Surfactant therapy in neonates with respiratory deterioration due to pulmonary hemorrhage. Pediatrics 1995, 95, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amizuka, T.; Shimizu, H.; Niida, Y.; Ogawa, Y. Surfactant therapy in neonates with respiratory failure due to haemorrhagic pulmonary oedema. Eur J Pediatr 2003, 162, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, H.V.; Berryman, J.; Bolton-Maggs, P.H.; Cantwell, C.; Chalmers, E.A.; Davies, T.; Gottstein, R.; Kelleher, A.; Kumar, S.; Morley, S.L.; et al. Guidelines on transfusion for fetuses, neonates and older children. Br J Haematol 2016, 175, 784–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poralla, C.; Hertfelder, H.-J.; Oldenburg, J.; Müller, A.; Bartmann, P.; Heep, A. Treatment of acute pulmonary haemorrhage in extremely preterm infants with recombinant activated factor VII. Acta Paediatrica 2010, 99, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Tang, S.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Pan, F. New Treatment of Neonatal Pulmonary Hemorrhage with Hemocoagulase in Addition to Mechanical Ventilation. Biology of the Neonate 2005, 88, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodha, A.; Kamaluddeen, M.; Akierman, A.; Amin, H. Role of Hemocoagulase in Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2011, 78, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, J.; Tang, S.; Pan, F.; Liu, L.; Tian, Z.; Li, H. Effect of hemocoagulase for prevention of pulmonary hemorrhage in critical newborns on mechanical ventilation: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr 2008, 45, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Can, E.; Hamilçıkan, Ş. Efficacy of Tranexamic Acid in Severe Pulmonary Hemorrhage in a Asphyctic Neonate. 2018.

- Singleton, L.; Kennedy, C.; Philip, B.; Navaei, A.; Bhar, S.; Ankola, A.; Doane, K.; Ontaneda, A. Use of Inhaled Tranexamic Acid for Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Pediatric Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support. Asaio j 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, S.; Halis, H. Treatment of Acute Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Neonates with Endotracheal Ankaferd Blood Stopper Use. THE ULUTAS MEDICAL JOURNAL 2021, 7, 248–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markestad, T.; Finne, P.H. Effect of tolazoline in pulmonary hemorrhage in the newborn. Acta Paediatr Scand 1980, 69, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).