1. Introduction

Urban forests are important to cities and provide a range of ecosystem services, including carbon (C) sequestration, air purification, and urban cooling, which enhance the quality of life for urban populations (Ariluoma et al., 2021; Shafique et al., 2020). As urbanization accelerates globally, urban forests are increasingly recognized as critical components of sustainable urban ecosystems (Reyes-Riveros et al., 2021). However, urban forests also generate significant quantities of organic waste, including grass clippings, pruned branches, leaf litter, and fallen woody debris, primarily resulting from landscaping and maintenance activities. Those organic wastes, often sent to dump sites, pose significant environmental challenges if improperly managed (Lan et al., 2022). When waste materials undergo microbial decomposition, they release greenhouse gases (GHGs), including carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O) —which all contribute to the global warming potential (GWP), although some have a much stronger effect than others. A study conducted in five municipalities of Paraíba state, northeast Brazil, revealed that improper disposal of urban tree pruning waste resulted in emissions of >1 Mt CO2 equivalent over a ten-year period (Araujo et al., 2024). These emissions contribute to global warming and exacerbate other forms of climate change, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable waste management strategies tailored to urban contexts.

While considerable research has been conducted on GHG emissions from soils or soil systems amended with organic waste (Chataut et al., 2023; Gross et al., 2022), relatively few studies have directly examined GHG emissions from decomposing urban forestry waste. The decomposition dynamics of organic material in soil differ significantly from those of urban forestry waste, which is often piled at open dumping sites (Osra et al., 2024). Soil emissions are primarily driven by microbial processes that decompose organic matter and are influenced by factors such as soil type, moisture content, temperature, and the quantity and quality of organic inputs (Davidson & Janssens, 2006; Wang et al., 2020). In contrast, greenhouse gas emissions from urban forestry waste are mainly influenced by the chemical composition of the waste (e.g., C:N ratio, lignin content) as well as by exposure to air and fluctuating moisture and temperature conditions (Sánchez et al., 2015). These factors can lead to markedly different emission profiles compared to those observed in soil systems.

Despite the growing volume of urban forestry waste, a notable research gap remains regarding its direct GHG emissions and how those emissions might be mitigated. This gap is critical to address given the unique chemical composition of urban forestry waste compared to agricultural or municipal waste and the increasing quantities generated due to rapid urbanization. For instance, urban forestry waste typically contains higher proportions of recalcitrant organic matter such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, which decompose more slowly and affect microbial metabolism and gas fluxes differently than typical soil organic matter or food-based municipal waste. Understanding the GHG emissions and environmental impacts of this waste and identifying strategies to reduce those emissions are important. For example, biochar—a carbon-rich material produced through pyrolysis—has been shown to reduce GHG emissions in various organic substrates and soils (Duan et al., 2020; Gross et al., 2022). Recent studies have shown that incorporating biochar into urban green infrastructure increases nutrient availability, enhances water retention, stimulates microbial activity, promotes plant growth, and improves carbon sequestration (Liao et al., 2023; Senadheera et al., 2024). A mesocosm experiment demonstrated that biochar can enhance CH₄ uptake and alter CO₂ fluxes when applied with mulched urban forestry waste, such as woodchips and bark, by modifying microbial activity, pH, and C:N ratios, as well as improving substrate aeration and reducing water loss (Kayes et al., 2025). These findings highlight the multifaceted role of biochar in modulating GHG fluxes from organic waste systems, including its capacity to influence microbial communities and substrate conditions. However, studies investigating the effects of biochar on greenhouse gas emissions and the underlying physicochemical and microbial changes during the decomposition of urban forestry waste are still limited.

In this study, we examined the effects of biochar on GHG emissions from two common types of urban forestry waste: green waste, which is composed primarily of grass clippings, fresh leaves, and small branches from pruning operations, and yard waste, which includes wood debris, composted urban forestry waste, and soil that has mixed in during collection or processing. We hypothesized that biochar influences GHG emissions by altering extracellular enzyme activity and the physicochemical properties of urban forestry waste, thereby reducing GHG production during decomposition. The objectives of this study were to (i) assess CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O emissions from green waste and yard waste, (ii) examine the impact of biochar addition on extracellular hydrolytic enzyme activities and the physicochemical properties of these wastes, and (iii) evaluate how these changes influence GHG emissions and GWP. The findings can support local policymakers, urban planners, and environmental managers in identifying more sustainable strategies for managing urban forestry waste, with potential contributions to regional sustainability and climate action efforts.2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Materials

Green waste and yard waste were collected from an urban forestry waste dumping site located in Ambleside (53°25'35.5" N, 113°34'20.3" W), Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, one of the city's designated sites for urban forestry waste disposal. Green waste mostly consists of grass clippings and some fresh leaves. Yard waste consists of compost, wood debris, and soil, which are primarily used for home gardens. The collected materials were homogenized before conducting the incubation experiment. Subsamples were taken to determine the chemical properties of the materials. The initial moisture contents of the green waste and yard waste were 4.6% and 54.3% (w/w), respectively. The C, nitrogen (N) concentrations and C/N ratio were 36.9%, 3.5%, and 10.5, respectively, for the green waste, and 29.1%, 1.5%, and 19.3, respectively, for the yard waste. The biochar used in this study was supplied by Innotech Alberta (Vegreville, AB, CA) and pyrolyzed from wheat (Triticum aestivum) straw at 450-500 °C. The pH, electrical conductivity, C%, N%, and C/N ratio of the biochar were 9.1, 2.4 dS m-1, 56.5%, 0.96%, and 59.1, respectively.

2.2. Experimental Design and Incubation Procedure

The experiment used a completely randomized block design with four treatments and five replications. Two types of organic waste— green waste and yard waste —were each treated with and without biochar, resulting in four treatment combinations. The treatments included green waste without biochar (GW), green waste amended with 2% (w/w) wheat straw biochar (GWB), yard waste without biochar (YW), and yard waste amended with 2% (w/w) wheat straw biochar (YWB). The green waste was cut into small (2–5 cm) pieces to make them more uniform and fit into the jars used for the incubation. Before being used in the incubation, each waste material type was thoroughly mixed and homogenized. The initial moisture content of green waste was very low (4.6%). Since decomposition of organic waste typically begins when the moisture content is between 40% and 60%, we adjusted the moisture content to 50% by adding distilled water. This adjustment was performed to increase microbial activity and initiate the degradation process. When the initial moisture content of the yard waste was 54.3%, the moisture content was maintained at the initial value. For the GW and YW treatments, 50 g and 100 g of fresh material, respectively, were placed into 1 L Mason jars. For the GWB and YWB treatments, each material was mixed with biochar at a rate of 2% (w/w) on an oven-dry weight basis before being placed into 1 L Mason jars. The materials were compacted to a specific depth in all treatments, ensuring a consistent bulk density. The moisture content of all treatments was adjusted by adding distilled water every three days based on the weight loss observed throughout incubation. Since destructive sampling affects GHG measurements, two separate incubation experiments (for each waste type) were set up in parallel: one for measuring GHG emissions and the other for analyzing enzyme activities and physicochemical properties on days 1, 10, 50, and 100. The Mason jars were covered with aluminum foil, and pin holes were punctured in the foil to provide ventilation while minimizing water loss throughout the incubation. All the treatments were incubated at 22 °C. To maintain a humid environment and further minimize moisture loss from the incubated materials, 10 mL of Milli-Q water was added to a beaker placed inside the incubator (Impraim et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021).

2.3. Gas and Incubation Material Sampling and Analysis

Gas samples were collected from the headspace of the Mason jars on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 22, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100. The GHG concentrations were determined via a gas chromatograph (Varian CP-3800, Mississauga, ON, Canada) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (for detecting CO2), an electron capture detector (for detecting N2O), and a flame ionization detector (for detecting CH4) (Li et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). The incubated waste materials were destructively sampled from the Mason jars on days 1, 10, 50, and 100 to determine their enzyme activities and physicochemical properties.

2.4. Analysis of Enzyme Activities and Physicochemical Properties of the Incubated Materials

The activities of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes, including β-1,4-glucosidase (BG) and β-1,4-N-acetyl glucosaminidase (NAG), were analyzed in moist waste samples using a fluorometric method following the methods described in Sinsabaugh et al. (2003). For each sample, enzyme activity was determined using fluorogenic substrates: 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucopyranoside for BG and 4-methylumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide for NAG. Upon enzymatic hydrolysis, these substrates released 4-methylumbelliferone (MUB), a fluorescent product. Fluorescence in the aliquots was measured using a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) with 365 nm excitation and 450 nm emission filters. Fresh waste samples were oven-dried at 105 °C for ~24 hours to determine the moisture content. The pH and electrical conductivity of the waste materials were measured at a 1:10 (w:v) waste-to-water ratio via a pH meter (DMP-2 mV, Thermo Orion, USA). To determine the available N content in the waste materials, the samples were extracted with 0.01 M K₂SO₄ solution at a 1:20 (w:v) ratio and analyzed for NO₃⁻ and NH4+ via a colorimetric method (Keeney & Nelson, 1982; Mulvaney, 1996). The samples were extracted with 0.01 M K₂SO₄ solution at a 1:20 (w:v) ratio to determine the extractable C and N concentrations using a TOC-VCSN analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The extractable C concentration represents dissolved organic C (DOC), and the difference between the extractable N and available N (total inorganic N: TIN = NO₃⁻ + NH4+) represents dissolved organic N (DON) (Wu et al., 2020). The total C (TC) and total N (TN) contents of the waste materials were determined via a CHN elemental analyzer (Vario MICRO cube, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Germany). The C/N ratio was determined as the mass ratio of TC to TN.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All data analysis was conducted via SPSS v.26 software. Before statistical analysis, all data were tested for normality of distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity of variance using Levene's test. Enzyme activity and physicochemical property data were log- or square-root-transformed as necessary to account for unequal variances and then back-transformed after statistical analyses for presentation purposes. The effects of biochar on enzyme activities and physicochemical properties of green waste and yard waste were tested separately for each sampling time (after 1, 10, 50, and 100 days of incubation) via one-way ANOVA. The statistical significance of differences in all treatment effects was set at α = 0.05 in all analyses, and the means were separated among the treatments via Tukey's test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biochar Effects on Physicochemical Properties

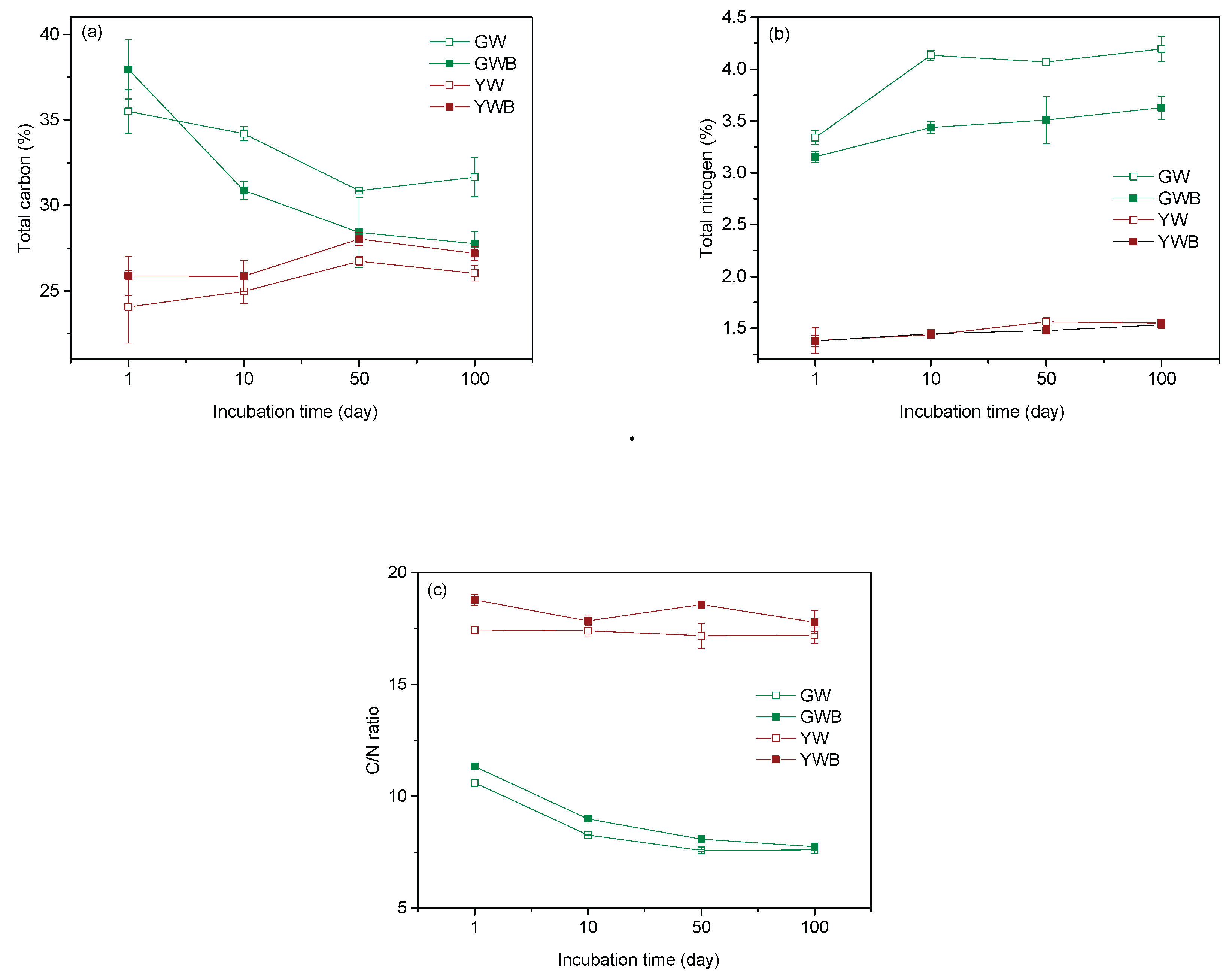

The TC in GW and GWB decreased over time (

Figure 1a), reflecting microbial decomposition of C and subsequent C loss. GWB showed a more rapid decline, suggesting biochar may enhance microbial activity or alter decomposition dynamics by increasing nutrient availability or serving as a microbial habitat (Ebrahimi et al., 2024; Li et al., 2018). TN increased in both treatments (

Figure 1b), likely due to microbial N immobilization or the formation of stable N compounds (Kauser et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2023). GWB consistently had a higher C/N ratio than GW (

Figure 1c), possibly because biochar slowed decomposition or retained N during early stages. As decomposition progressed, the C/N ratios of both treatments gradually converged (Alarefee et al., 2023). In contrast, TC remained relatively stable in YW and YWB (

Figure 1a), indicating slower decomposition, possibly due to more resistant C or lower microbial activity. TN increased slightly (

Figure 1b), and C/N ratios remained stable (

Figure 1c), suggesting consistent nutrient dynamics. These patterns suggest that biochar had a lesser influence on yard waste than on green waste. Yard waste’s high fixed C content (Fetene et al., 2018) and a larger proportion of slowly hydrolysable C in leaves and branches (Komilis, 2006) contribute to its slower decomposition. Green waste, including grass clippings, decomposes more rapidly due to a lower proportion of recalcitrant C.

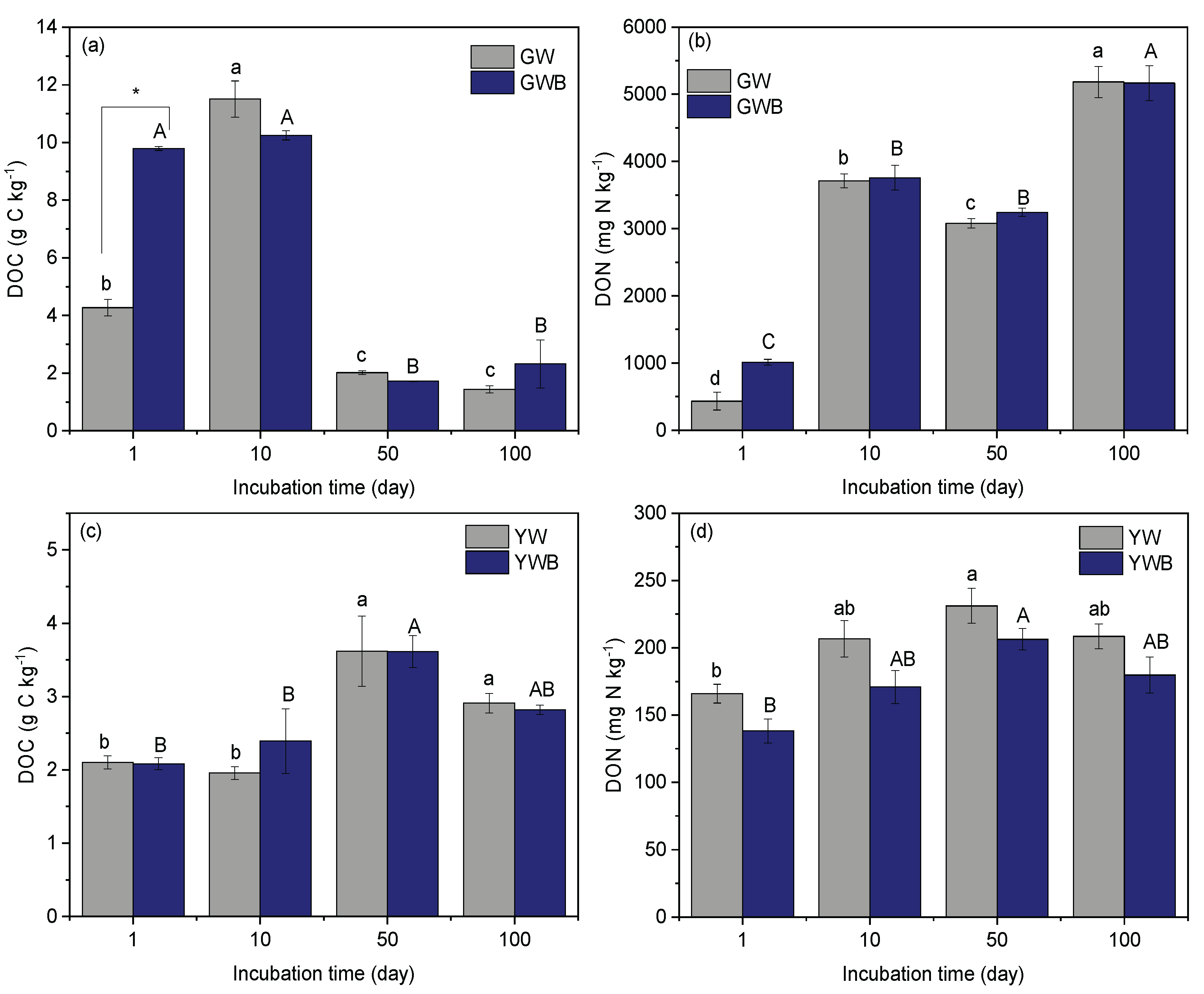

DOC levels were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in GWB than GW on day 1 (

Figure 2a), indicating that biochar stimulated early soluble C release. DOC peaked at day 10 in both treatments, followed by a steady decline due to microbial consumption and stabilization of labile organic matter (Godlewska et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). DON also peaked on day 10 (

Figure 2b), reflecting active microbial decomposition and N release (Belias et al., 2007; El Barnossi et al., 2019). Despite early differences, DON levels in GW and GWB were similar by day 100, suggesting biochar’s limited long-term effect on total DON dynamics. In YW and YWB, DOC significantly increased (p < 0.05) on days 50 and 100 (

Figure 2c), and DON peaked on day 50 (

Figure 2d). These increases likely result from the gradual decomposition of more complex organic matter and the release of soluble C and N (Błońska et al., 2023). Biochar did not significantly affect the trends in DOC or DON in yard waste, indicating a limited role in influencing the release of C and N from more recalcitrant materials. GW and GWB showed stable pH values throughout the incubation period (

Table 1), indicating consistent alkalinity. Electrical conductivity (EC) increased gradually due to the release of mineral salts during decomposition (Chen et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2021). In GW, NH₄⁺ levels declined significantly (p < 0.05), consistent with ammonification followed by volatilization or nitrification (Manga et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2023). In GWB, NH₄⁺ initially increased and then declined slightly, suggesting that biochar helped retain NH₄⁺. NO₃⁻ concentrations in both treatments increased significantly by day 100, indicating nitrification. The TIN was consistently higher in GWB, indicating that biochar enhanced overall N retention. In YW and YWB, pH remained stable with minimal fluctuations (

Table 2), while EC steadily increased, reflecting ongoing mineralization. NH₄⁺ levels declined, and NO₃⁻ levels increased progressively, a typical pattern of aerobic decomposition in organic matter (Zhang et al., 2002). These changes reflect the conversion of organic N to NH₄⁺ and its subsequent oxidation to NO₃⁻. The observed trends align with the composting literature, showing a reduction in NH₄⁺ and an increase in NO₃⁻ over time (Cardoso et al., 2022). Biochar had little impact on these patterns in yard waste, possibly due to the more stable nature of its organic matter.

3.2. Biochar Effects on Enzyme Activities

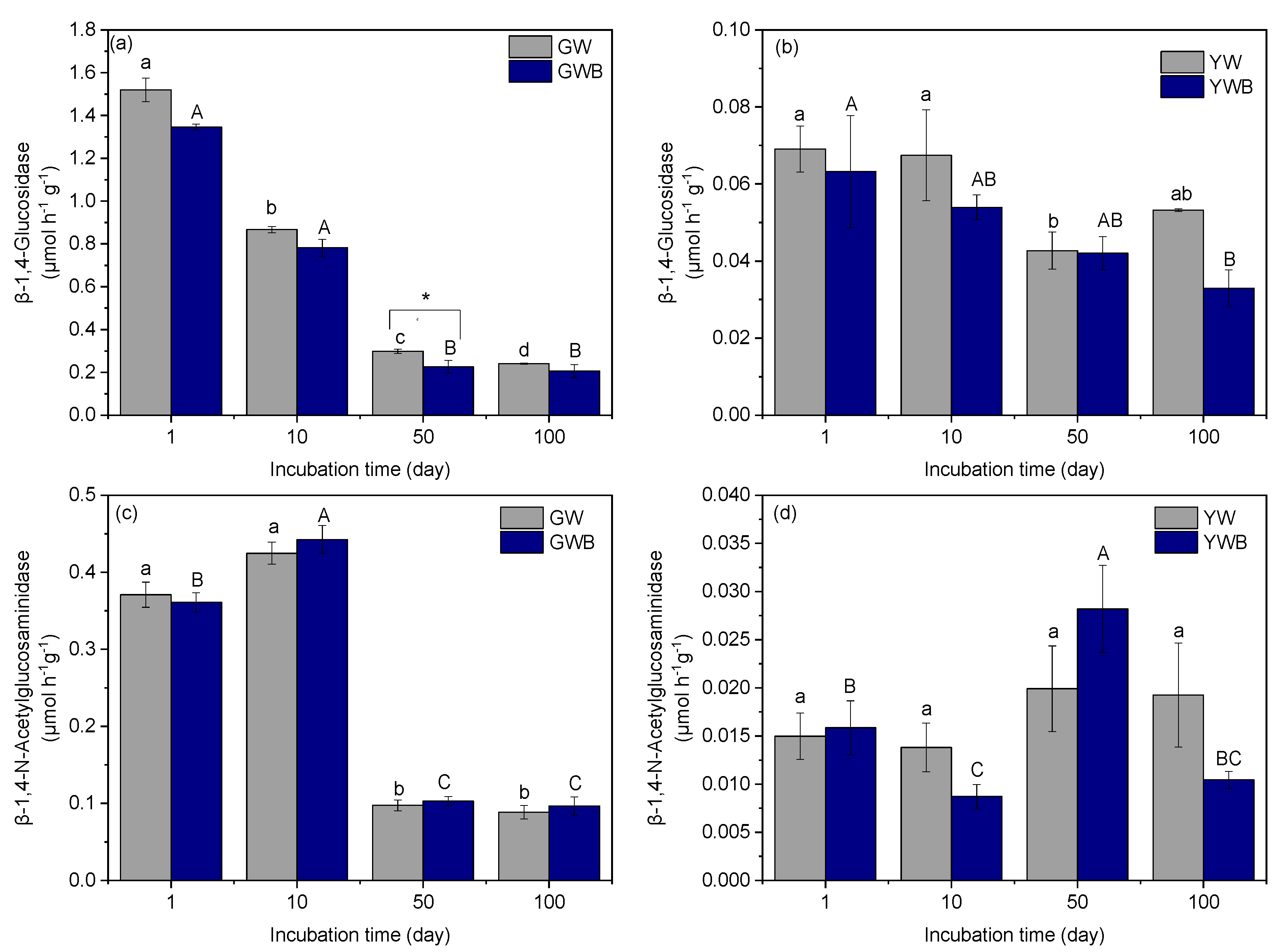

In GW, BG activity declined significantly over time (

Figure 3a), dropping by 42.9% on day 10, 80.4% on day 50, and 84.1% on day 100 relative to day 1. This suggests reduced cellulose availability and microbial activity as decomposition progressed (Daunoras et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2024). GWB showed a more gradual decline, with significant reductions (p < 0.05) only after day 10. In YW, BG activity was relatively stable, with a significant decrease observed only on day 50 (

Figure 3b), indicating slower decomposition and more resilient enzyme dynamics. In YWB, a significant reduction occurred only on day 100.

For NAG, GW showed a significant decline by days 50 and 100 (

Figure 3c), reflecting the diminishing availability of N-containing substrates over time (Sun et al., 2023). GWB peaked on day 10 but declined significantly thereafter, suggesting that biochar may temporarily stimulate enzyme activity before decomposition advances (Hardy et al., 2019; Zaid et al., 2024). YW displayed consistently low NAG activity (

Figure 3d), while YWB showed minimal activity on day 10 and a peak on day 50. These trends emphasize the influence of substrate quality and biochar on enzyme activity and nitrogen cycling during decomposition.

3.3. Biochar Effects on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Global Warming Potential

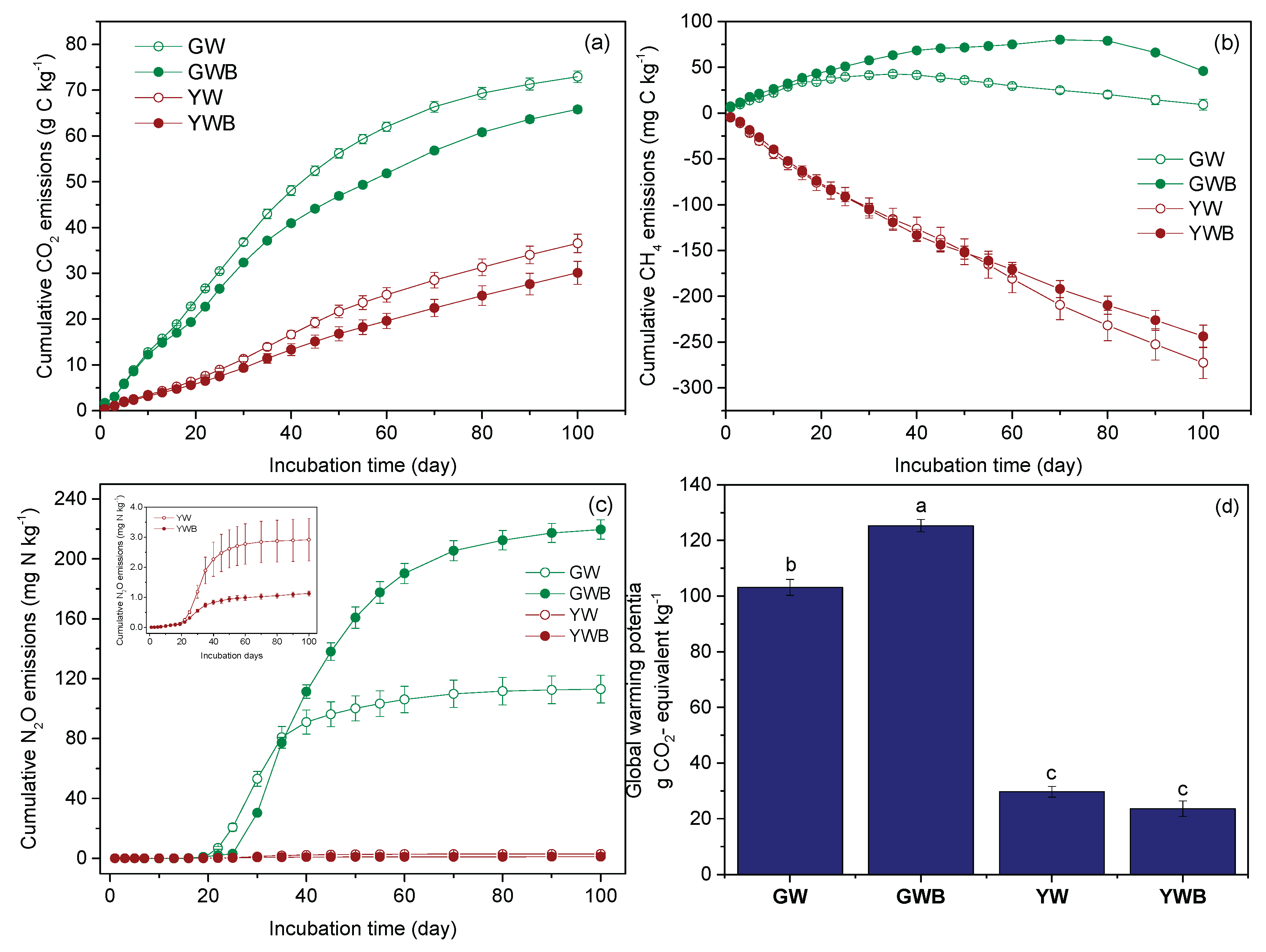

Compared with YW, GW consistently emitted more CO₂ throughout the 100-day incubation (

Figure 4a), likely due to its higher content of easily degradable compounds such as cellulose (25.3%) and hemicellulose (46.3%) (Zhang & Sun, 2014), as well as its higher nitrogen content. In contrast, yard waste contained more lignin (Komilis and Ham (2003), which is more resistant to microbial decomposition. As a result, GW emitted over three times more CO₂ than YW on day 1 and continued to emit substantially more by day 100. Adding biochar significantly reduced CO₂ emissions in both waste types, suggesting a stabilizing effect on organic matter (Bekchanova et al., 2024; Kalu et al., 2024). GW also produced notable CH₄ emissions, peaking at day 30 (

Figure 4b). Interestingly, CH₄ emissions were even higher in GWB, suggesting that biochar may stimulate methanogenic activity in GW (Gao et al., 2022). In contrast, both YW and YWB showed negative cumulative CH₄ emissions (

Figure 4b), indicating net CH₄ uptake driven by methanotrophic activity. Similarly, Li et al. (2021) reported a net CH₄ uptake (i.e., negative CH₄ emissions) in soils amended with biochar. The N₂O emissions were substantially higher in GWB than in GW (

Figure 4c), possibly due to biochar inhibiting N₂O-reducing microbes and increasing nitrate and ammonium availabilities for N₂O production through nitrification and denitrification (Cayuela et al., 2014; Escuer-Gatius et al., 2020; Li et al., 2024). Conversely, biochar addition reduced N₂O emissions in YWB compared to YW (

Figure 4c), emphasizing that biochar’s effects vary with the waste type. As a result of elevated CH₄ and N₂O emissions, GWB exhibited the highest global warming potential (GWP: 125.3 g CO₂-eq kg⁻¹) (

Figure 4d). In contrast, YW and YWB showed significantly lower (p < 0.05) GWPs (29.7 and 23.6 g CO₂-eq kg⁻¹, respectively) as compared to GWB, with no significant difference between YW and YWB. These findings underscore that biochar’s impact on GHG emissions and GWP is highly dependent on the type of waste material.

3.4. Factors Affecting GHG Emissions from Green Waste Under Biochar Application

On Day 100, Pearson correlation analysis revealed key relationships between GHG emissions and several variables (

Table 3). CO₂ emissions were positively correlated with TC (r = 0.73, p < 0.05) and TN (r = 0.76, p < 0.05), but negatively correlated with NH₄⁺ (r = -0.83, p < 0.01) and TIN (r = -0.73, p < 0.05). Cumulative CO₂ emissions were lower in GWB than in GW (

Figure 4a), suggesting biochar moderated emissions by stabilizing organic matter and slowing decomposition (Hassan et al., 2024; Spokas et al., 2009). Wu et al. (2020) similarly observed that increased TIN availability reduced CO₂ emissions. Biochar's retention of NH₄⁺ and NO₃⁻ may suppress microbial activity responsible for CO₂ production by altering N availability and microbial communities (Liang et al., 2019; Zhai et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2021)

CH₄ emissions were negatively correlated with TC (r = -0.79, p < 0.01) and TN (r = -0.78, p < 0.01), but positively correlated with NO₃⁻ (r = 0.77, p < 0.01) and TIN (r = 0.89, p < 0.01). CH₄ emissions were higher in GWB, possibly due to elevated TIN (1083.1 mg N g⁻¹), which may have promoted methanogenesis. The positive correlation with NO₃⁻ suggests that N availability supported methanogenic microbial activity. Biochar's ability to store nutrients may indirectly facilitate CH₄ production (Pant & Rai, 2021; Xiao et al., 2021). While some studies report CH₄ suppression by biochar through enhanced methanotrophy (Huang et al., 2023; Nandipamu et al., 2024), high organic N in green waste may override this effect.

N₂O emissions were negatively correlated with TC (r = -0.69, p < 0.05) and TN (r = -0.72, p < 0.05), but positively correlated with NH₄⁺ (r = 0.705, p < 0.05), NO₃⁻ (r = 0.69, p < 0.05), and TIN (r = 0.88, p < 0.01). GWB emitted significantly more N₂O than GW (

Figure 4c), likely due to the increased availability of NH₄⁺ and NO₃⁻ (

Table 1), which are key substrates for nitrification and denitrification (Guo et al., 2023). These findings align with previous studies, which have shown that biochar can increase N₂O emissions under high N availability and labile C conditions (Edwards et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023).

GWP was positively correlated with NO₃⁻ (r = 0.71, p < 0.05) and TIN (r = 0.86, p < 0.01), and negatively with TN (r = -0.65, p < 0.05). It also showed a negative correlation with CO₂ emissions (r = -0.66, p < 0.01) and strong positive correlations with CH₄ (r = 0.90, p < 0.01) and N₂O (r = 0.98, p < 0.01), highlighting the dominant role of these gases in determining the total GWP. Although biochar application led to a reduction in CO₂ emissions—likely due to its stabilization of labile carbon and suppression of microbial respiration—the concurrent increases in CH₄ and N₂O emissions resulted in an overall rise in GWP. This is primarily due to the much higher global warming potentials of CH₄ and N₂O, which are 25 and 298 times greater than that of CO₂, respectively (Chen et al., 2019). These findings suggest that the benefits of CO₂ mitigation through biochar are offset by enhanced emissions of more potent greenhouse gases. Therefore, while biochar has potential as a carbon management strategy, its use in organic waste systems may pose a trade-off, and strategies to mitigate CH₄ and N₂O emissions must be considered to optimize its environmental performance.

3.5. Factors Affecting GHG Emissions from Yard Waste Under Biochar Application

Carbon dioxide emissions were positively correlated with NAG activity (r = 0.68, p < 0.05) (

Table 3), indicating that higher CO₂ emissions are associated with increased microbial N cycling. NAG is involved in chitin degradation, contributing to N mineralization and stimulating microbial respiration, which releases CO₂ (Uwituze et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2025). Methane emissions were positively correlated with NO₃⁻ (r = 0.74, p < 0.05) and TIN (r = 0.71, p < 0.05) and negatively with DON (r = −0.65, p < 0.05). These results suggest that greater N availability promotes methanogenesis as microbial activity increases with available N (Bodelier & Laanbroek, 2004; Liu et al., 2024b). In contrast, higher DON may suppress CH₄ production by promoting denitrifiers or limiting labile C for methanogens (Chen et al., 2009; Euler et al., 2020; Riyaz & Khan, 2024).

Nitrous oxide emissions were negatively correlated with EC (r = -0.77, p < 0.05) and TIN (r = -0.74, p < 0.05). The increased EC from biochar amendment may inhibit microbial processes involved in N₂O production, thereby reducing emissions (Liu et al., 2024a; Yuan et al., 2019). Enhancing biochar’s electrochemical properties, such as specific capacitance and electrical conductivity, has been shown to mitigate N₂O emissions (Liu et al., 2024a). The negative correlation with TIN suggests that biochar may alter N cycling by shifting denitrification pathways or reducing excess N availability (Liao et al., 2021). On the other hand, N₂O emissions were positively correlated with BG activity (r = 0.68, p < 0.05), indicating that biochar’s influence on C degradation also affects N transformations. Yan et al. (2024) reported similar findings linking N₂O emissions with BG activity. Reduced BG activity due to biochar likely limited cellulose decomposition and glucose release, decreasing energy availability for microbial growth. Since denitrification relies on both NO₃⁻ and labile C (Yang et al., 2019), lower C availability restricts this process, thereby reducing N₂O emissions (Gao et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2018).

The GWP was negatively correlated with pH (r = -0.66, p < 0.05). Biochar’s alkalinity can buffer acidity, influencing microbial community structure and enzymatic activity related to GHG emissions (Criscuoli et al., 2024; Duan et al., 2024). These results support previous findings that increasing soil pH through biochar can suppress GHG production by altering N cycling pathways (Saharan et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023). GWP also showed a strong positive correlation with CO₂ emissions (r = 0.99, p < 0.01), underscoring the dominant role of CO₂ in contributing to global warming potential.

4. Conclusions

Biochar has dual effects on GHG emissions and waste decomposition in urban forestry waste. Biochar addition reduced CO₂ emissions in green waste and yard waste, highlighting biochar’s potential for C stabilization. The increased CH₄ and N₂O emissions in GWB underscore the complex interplay between biochar and changes in microbial communities and substrate availability. The YW and YWB exhibited negative cumulative CH₄ emissions, and YWB exhibited lower N2O emissions than YW. The GWP was highest in GWB at 125.3 g CO₂-eq kg⁻¹, indicating that biochar application exacerbated the overall GHG impact of green waste. Our findings highlight the influence of the chemical composition of waste materials on the effectiveness of biochar in mitigating GHG emissions. Green waste, rich in labile organic C, exhibited faster decomposition and greater microbial activity, amplifying the effects of biochar on CH₄ and N₂O production. In contrast, yard waste, characterized by its high concentrations of recalcitrant compounds, was more affected by biochar application, which reduced overall GHG emissions. Our findings emphasize the need for a tailored approach to biochar application, as well as the importance of considering the specific properties of the waste material. Further research should explore strategies, such as combining biochar with complementary amendments or fine-tuning application rates, to maximize biochar’s potential for sustainable waste management.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an NSERC (Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada) Alliance grant (grant No. ALLRP 577155-2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alarefee, H.A., Ishak, C.F., Othman, R., Karam, D.S. 2023. Effectiveness of mixing poultry litter compost with rice husk biochar in mitigating ammonia volatilization and carbon dioxide emission. Journal of Environmental Management, 329, 117051. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, Y.R.V., Souza, B.I., Carvalho, M. 2024. Greenhouse gas emissions associated with tree pruning residues of urban areas of Northeast Brazil. Resources, 13(9), 127. [CrossRef]

- Ariluoma, M., Ottelin, J., Hautamäki, R., Tuhkanen, E.-M., Mänttäri, M. 2021. Carbon sequestration and storage potential of urban green in residential yards: A case study from Helsinki. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 57, 126939. [CrossRef]

- Bekchanova, M., Kuppens, T., Cuypers, A., Jozefczak, M., Malina, R. 2024. Biochar’s effect on the soil carbon cycle: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Biochar, 6(1), 88. [CrossRef]

- Belias, C., Dassenakis, M., Scoullos, M. 2007. Study of the N, P and Si fluxes between fish farm sediment and seawater. Results of simulation experiments employing a benthic chamber under various redox conditions. Marine Chemistry, 103(3), 266-275. [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E., Prażuch, W., Lasota, J. 2023. Deadwood affects the soil organic matter fractions and enzyme activity of soils in altitude gradient of temperate forests. Forest Ecosystems, 10, 100115. [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P.L.E., Laanbroek, H.J. 2004. Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 47(3), 265-277. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.H.S., Gonçalves, P.W.B., Alves, G.d.O., Pegoraro, R.F., Fernandes, L.A., Frazão, L.A., Sampaio, R.A. 2022. Improving the quality of organic compost of sewage sludge using grass cultivation followed by composting. Journal of Environmental Management, 314, 115076. [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, M.L., van Zwieten, L., Singh, B.P., Jeffery, S., Roig, A., Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. 2014. Biochar's role in mitigating soil nitrous oxide emissions: A review and meta-analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 191, 5-16. [CrossRef]

- Chataut, G., Bhatta, B., Joshi, D., Subedi, K., Kafle, K. 2023. Greenhouse gases emission from agricultural soil: A review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 11, 100533. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Huang, Y., Liu, H., Xie, S., Abbas, F. 2019. Impact of different nitrogen source on the compost quality and greenhouse gas emissions during composting of garden waste. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 124, 326-335. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Ma, X., Liang, J. 2024. Carbon conversion and microbial driving factors in the humification of green waste composts. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Sun, D., Chung, J.-S. 2009. Simultaneous methanogenesis and denitrification of aniline wastewater by using anaerobic–aerobic biofilm system with recirculation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 169(1), 575-580. [CrossRef]

- Criscuoli, I., Panzacchi, P., Tognetti, R., Petrillo, M., Zanotelli, D., Andreotti, C., Loesch, M., Raifer, B., Tonon, G., Ventura, M. 2024. Effects of woodchip biochar on temperature sensitivity of greenhouse gas emissions in amended soils within a mountain vineyard. Geoderma Regional, 38, e00847. [CrossRef]

- Daunoras, J., Kačergius, A., Gudiukaitė, R. 2024. Role of soil microbiota enzymes in soil health and activity changes depending on climate change and the type of soil ecosystem. Biology, 13(2), 85. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A., Janssens, I.A. 2006. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature, 440(7081), 165-173.

- Duan, M., Wu, F., Jia, Z., Wang, S., Cai, Y., Chang, S.X. 2020. Wheat straw and its biochar differently affect soil properties and field-based greenhouse gas emission in a Chernozemic soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 56(7), 1023-1036. [CrossRef]

- Duan, T., Zhao, J., Zhu, L. 2024. Insights into CO2 and N2O emissions driven by applying biochar and nitrogen fertilizers in upland soil. Science of The Total Environment, 929, 172439. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M., Gholipour, S., Mostafaii, G., Yousefian, F. 2024. Biochar-amended food waste compost: A review of properties. Results in Engineering, 24, 103118. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.D., Pittelkow, C.M., Kent, A.D., Yang, W.H. 2018. Dynamic biochar effects on soil nitrous oxide emissions and underlying microbial processes during the maize growing season. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 122, 81-90. [CrossRef]

- El Barnossi, A., Moussaid, F., Iraqi Housseini, A. 2019. Decomposition of tangerine and pomegranate wastes in water and soil: characterisation of physicochemical parameters and global microbial activities under laboratory conditions. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 76(3), 456-470. [CrossRef]

- Escuer-Gatius, J., Shanskiy, M., Soosaar, K., Astover, A., Raave, H. 2020. High-temperature hay biochar application into soil increases N2O fluxes. Agronomy, 10(1), 109. [CrossRef]

- Euler, S., Jeffrey, L.C., Maher, D.T., Mackenzie, D., Tait, D.R. 2020. Shifts in methanogenic archaea communities and methane dynamics along a subtropical estuarine land use gradient. Plos One, 15(11), e0242339. [CrossRef]

- Fetene, Y., Addis, T., Beyene, A., Kloos, H. 2018. Valorisation of solid waste as key opportunity for green city development in the growing urban areas of the developing world. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 6(6), 7144-7151. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Liu, L., Shi, Z., Lv, J. 2022. Biochar amendments facilitate methane production by regulating the abundances of methanogens and methanotrophs in flooded paddy soil. Frontiers in Soil Science, 2, 801227. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W., Yao, Y., Gao, D., Wang, H., Song, L., Sheng, H., Cai, T., Liang, H. 2019. Responses of N2O emissions to spring thaw period in a typical continuous permafrost region of the Daxing'an Mountains, northeast China. Atmospheric Environment, 214, 116822. [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, P., Schmidt, H.P., Ok, Y.S., Oleszczuk, P. 2017. Biochar for composting improvement and contaminants reduction. A review. Bioresource Technology, 246, 193-202. [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.D., Bork, E.W., Carlyle, C.N., Chang, S.X. 2022. Biochar and its manure-based feedstock have divergent effects on soil organic carbon and greenhouse gas emissions in croplands. Science of The Total Environment, 806, 151337.

- Guo, X., Xie, H., Pan, W., Li, P., Du, L., Zou, G., Wei, D. 2023. Enhanced nitrogen removal via biochar-mediated nitrification, denitrification, and electron transfer in constructed wetland microcosms. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(28), 72710-72720.

- Hardy, B., Sleutel, S., Dufey, J.E., Cornelis, J.-T. 2019. The long-term effect of biochar on soil microbial abundance, activity and community structure is overwritten by land management. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.S., Jalil, A.A., Izzuddin, N.M., Bahari, M.B., Hatta, A.H., Kasmani, R.M., Norazahar, N. 2024. Recent advances in lignocellulosic biomass-derived biochar-based photocatalyst for wastewater remediation. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 163, 105670.

- Huang, Y., Tao, B., Lal, R., Lorenz, K., Jacinthe, P.-A., Shrestha, R.K., Bai, X., Singh, M.P., Lindsey, L.E., Ren, W. 2023. A global synthesis of biochar's sustainability in climate-smart agriculture - Evidence from field and laboratory experiments. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 172, 113042. [CrossRef]

- Impraim, R., Weatherley, A., Chen, D., Suter, H. 2022. Effect of lignite amendment on carbon and nitrogen mineralization from raw and composted manure during incubation with soil. Pedosphere, 32(5), 785-795. [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S., Seppänen, A., Mganga, K.Z., Sietiö, O.-M., Glaser, B., Karhu, K. 2024. Biochar reduced the mineralization of native and added soil organic carbon: evidence of negative priming and enhanced microbial carbon use efficiency. Biochar, 6(1), 7.

- Kauser, H., Pal, S., Haq, I., Khwairakpam, M. 2020. Evaluation of rotary drum composting for the management of invasive weed Mikania micrantha Kunth and its toxicity assessment. Bioresource Technology, 313, 123678. [CrossRef]

- Kayes, I., Halim, M.A., Thomas, S.C. 2025. Biochar mitigates methane emissions from organic mulching in urban soils: Evidence from a long-term mesocosm experiment. Journal of Environmental Management, 376, 124525. [CrossRef]

- Keeney, D.R., Nelson, D.W. 1982. Nitrogen—inorganic forms. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties, 9, 643-698.

- Komilis, D.P. 2006. A kinetic analysis of solid waste composting at optimal conditions. Waste Management, 26(1), 82-91.

- Komilis, D.P., Ham, R.K. 2003. The effect of lignin and sugars to the aerobic decomposition of solid wastes. Waste management, 23(5), 419-423.

- Lan, K., Zhang, B., Yao, Y. 2022. Circular utilization of urban tree waste contributes to the mitigation of climate change and eutrophication. One Earth, 5(8), 944-957. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Tang, Y., Gao, W., Pan, W., Jiang, C., Lee, X., Cheng, J. 2024. Response of soil N2O production pathways to biochar amendment and its isotope discrimination methods. Chemosphere, 350, 141002.

- Li, J., Kwak, J.-H., Chang, S.X., Gong, X., An, Z., Chen, J. 2021. Greenhouse gas emissions from forest soils reduced by straw biochar and nitrapyrin applications. Land, 10(2), 189. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Yao, S., Wang, Z., Jiang, X., Song, Y., Chang, S.X. 2022. Polyethylene microplastic and biochar interactively affect the global warming potential of soil greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental Pollution, 315, 120433.

- Li, Y., Hu, S., Chen, J., Müller, K., Li, Y., Fu, W., Lin, Z., Wang, H. 2018. Effects of biochar application in forest ecosystems on soil properties and greenhouse gas emissions: a review. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 18(2), 546-563. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-F., An, J., Gao, J.-Q., Zhang, X.-Y., Song, M.-H., Yu, F.-H. 2019. Interactive effects of biochar and AMF on plant growth and greenhouse gas emissions from wetland microcosms. Geoderma, 346, 11-17.

- Liao, W., Halim, M.A., Kayes, I., Drake, J.A., Thomas, S.C. 2023. Biochar benefits green infrastructure: global meta-analysis and synthesis. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(41), 15475-15486.

- Liao, X., Müller, C., Jansen-Willems, A., Luo, J., Lindsey, S., Liu, D., Chen, Z., Niu, Y., Ding, W. 2021. Field-aged biochar decreased N2O emissions by reducing autotrophic nitrification in a sandy loam soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 57(4), 471-483.

- Liu, X., Liu, X., Gao, S. 2024a. The electrochemical mechanism of biochar for mediating the product ratio of N2O/(N2O + N2) in the denitrification process. Science of the Total Environment, 951, 175566.

- Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Dong, J., Ren, S. 2024b. The impact of global change factors on the functional genes of soil nitrogen and methane cycles in grassland ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Oecologia, 207(1), 6.

- Liu, Y., Zhu, J., Ye, C., Zhu, P., Ba, Q., Pang, J., Shu, L. 2018. Effects of biochar application on the abundance and community composition of denitrifying bacteria in a reclaimed soil from coal mining subsidence area. Science of the Total Environment, 625, 1218-1224.

- Manga, M., Camargo-Valero, M.A., Anthonj, C., Evans, B.E. 2021. Fate of faecal pathogen indicators during faecal sludge composting with different bulking agents in tropical climate. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 232, 113670. [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, R.L. 1996. Nitrogen—inorganic forms. Methods of soil analysis: Part 3 Chemical methods, 5, 1123-1184.

- Nandipamu, T.M.K., Nayak, P., Chaturvedi, S., Dhyani, V.C., Sharma, R., Tharayil, N. 2024. Chapter 17 - Biochar-led methanogenic and methanotrophic microbial community shift: mitigating methane emissions. in: Biochar Production for Green Economy, (Eds.) S.V. Singh, S. Mandal, R.S. Meena, S. Chaturvedi, K. Govindaraju, Academic Press, pp. 335-358.

- Osra, F.A., Elbisy, M.S., Mosaıbah, H.A., Osra, K., Ciner, M.N., Ozcan, H.K. 2024. Environmental impact assessment of a dumping site: A case study of Kakia dumping site. Sustainability, 16(10), 3882.

- Pant, A., Rai, J.P.N. 2021. Application of Biochar on methane production through organic solid waste and ammonia inhibition. Environmental Challenges, 5, 100262.

- Reyes-Riveros, R., Altamirano, A., De La Barrera, F., Rozas-Vásquez, D., Vieli, L., Meli, P. 2021. Linking public urban green spaces and human well-being: A systematic review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 61, 127105.

- Riyaz, Z., Khan, S.T. 2024. Nitrogen fixation by methanogenic Archaea, literature review and DNA database-based analysis; significance in face of climate change. Archives of Microbiology, 207(1), 6.

- Saharan, B.S., Dhanda, D., Mandal, N.K., Kumar, R., Sharma, D., Sadh, P.K., Jabborova, D., Duhan, J.S. 2024. Microbial contributions to sustainable paddy straw utilization for economic gain and environmental conservation. Current Research in Microbial Sciences, 7, 100264.

- Sánchez, A., Artola, A., Font, X., Gea, T., Barrena, R., Gabriel, D., Sánchez-Monedero, M.Á., Roig, A., Cayuela, M.L., Mondini, C. 2015. Greenhouse gas emissions from organic waste composting. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 13(3), 223-238.

- Senadheera, S.S., Withana, P.A., Lim, J.Y., You, S., Chang, S.X., Wang, F., Rhee, J.H., Ok, Y.S. 2024. Carbon negative biochar systems contribute to sustainable urban green infrastructure: a critical review. Green Chemistry, 26(21), 10634-10660.

- Shafique, M., Xue, X., Luo, X. 2020. An overview of carbon sequestration of green roofs in urban areas. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 47, 126515. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D., Pandey, A.K., Yadav, K.D., Kumar, S. 2021. Response surface methodology and artificial neural network modelling for enhancing maturity parameters during vermicomposting of floral waste. Bioresource Technology, 324, 124672.

- Sinsabaugh, R., Saiya-Cork, K., Long, T., Osgood, M., Neher, D., Zak, D., Norby, R. 2003. Soil microbial activity in a Liquidambar plantation unresponsive to CO2-driven increases in primary production. Applied Soil Ecology, 24(3), 263-271.

- Spokas, K.A., Koskinen, W.C., Baker, J.M., Reicosky, D.C. 2009. Impacts of woodchip biochar additions on greenhouse gas production and sorption/degradation of two herbicides in a Minnesota soil. Chemosphere, 77(4), 574-581.

- Sun, B., Kallenbach, C.M., Boh, M.Y., Clark, O.G., Whalen, J.K. 2023. Enzyme activity after applying alkaline biosolids to agricultural soil. Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 103(2), 372-376. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X., Gao, R., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., Pan, J., Tang, K.H.D., Scriber Ii, K.E., Amoah, I.D., Zhang, Z., Li, R. 2023. Enhancing nitrogen conversion and microbial dynamics in swine manure composting process through inoculation with a microbial consortium. Journal of Cleaner Production, 423, 138819. [CrossRef]

- Uwituze, Y., Nyiraneza, J., Fraser, T.D., Dessureaut-Rompré, J., Ziadi, N., Lafond, J. 2022. Carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and extracellular soil enzyme responses to different land use. Frontiers in Soil Science, 2. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Odinga, E.S., Zhang, W., Zhou, X., Yang, B., Waigi, M.G., Gao, Y. 2019. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons in biochars and human health risks of food crops grown in biochar-amended soils: A synthesis study. Environment International, 130, 104899.

- Wang, J.Y., Ren, C.J., Feng, X.X., Zhang, L., Doughty, R., Zhao, F.Z. 2020. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition due to shifts in soil extracellular enzymes after afforestation. Geoderma, 374, 114426. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Li, X., Li, Y., Zeng, F., Gufwan, L.A., Yang, L., Xia, L., Song, S., Montes, M.L., Fernandez, M.A., Zheng, B., Wu, L. 2025. The inclusion of clay minerals accelerates biocrust formation and potentially boosts carbon storage capabilities. Soil and Tillage Research, 245, 106316.

- Wang, Y., Gu, J., Ni, J. 2023. Influence of biochar on soil air permeability and greenhouse gas emissions in vegetated soil: A review. Biogeotechnics, 1(4), 100040.

- Wu, Q., Kwak, J.-H., Chang, S.X., Han, G., Gong, X. 2020. Cattle urine and dung additions differently affect nitrification pathways and greenhouse gas emission in a grassland soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 56(2), 235-247.

- Xiao, L., Lichtfouse, E., Kumar, P.S., Wang, Q., Liu, F. 2021. Biochar promotes methane production during anaerobic digestion of organic waste. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 19(5), 3557-3564. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q., Li, L., Guo, J., Guo, H., Liu, M., Guo, S., Kuzyakov, Y., Ling, N., Shen, Q. 2024. Active microbial population dynamics and life strategies drive the enhanced carbon use efficiency in high-organic matter soils. mBio, 15(3), e00177-24.

- Yan, Z., Lin, S., Hu, R., Cheng, H., Xiang, R., Xu, H., Zhao, J. 2024. Effects of biodegradable microplastics and straw addition on soil greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental Pollution, 356, 124315. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Chen, X., Tang, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, C., Perry, D.C., You, W. 2019. External carbon addition increases nitrate removal and decreases nitrous oxide emission in a restored wetland. Ecological Engineering, 138, 200-208.

- Yuan, H., Zhang, Z., Li, M., Clough, T., Wrage-Mönnig, N., Qin, S., Ge, T., Liao, H., Zhou, S. 2019. Biochar's role as an electron shuttle for mediating soil N2O emissions. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 133, 94-96. [CrossRef]

- Zaid, F., Al-Awwal, N., Yang, J., Anderson, S.H., Alsunuse, B.T.B. 2024. Effects of biochar-amended composts on selected enzyme activities in soils. Processes, 12(8), 1678.

- Zhai, W., Jia, L., Zhao, R., Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Wei, Z. 2023. Response characteristics of nitrous oxide related microorganisms to biochar addition during chicken manure composting. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 169, 604-608.

- Zhang, L., Jing, Y., Chen, C., Xiang, Y., Rezaei Rashti, M., Li, Y., Deng, Q., Zhang, R. 2021. Effects of biochar application on soil nitrogen transformation, microbial functional genes, enzyme activity, and plant nitrogen uptake: A meta-analysis of field studies. GCB Bioenergy, 13(12), 1859-1873. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Sun, X. 2014. Effects of rhamnolipid and initial compost particle size on the two-stage composting of green waste. Bioresource Technology, 163, 112-122. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, C., Zhou, X., Moore, B. 2002. A simulation model linking crop growth and soil biogeochemistry for sustainable agriculture. Ecological Modelling, 151(1), 75-108. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Chen, G., Yu, D., Liu, R., Chen, X., Yang, Z., Yao, T., Gong, Y., Shan, Y., Wang, Y. 2023. Sludge composting with self-produced carbon source by phosphate buffer coupled hyperthermophilic pretreatment realizing nitrogen retention. Chemical Engineering Journal, 476, 146811. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).