1. Introduction

Energy Performance Contracts (EPC) are among the performance-based financing models that encourage energy efficiency and renewable energy investments, and enable the implementation of cost-effective projects in the public sector. EPC applications in Turkey have gained momentum in recent years, especially for the reduction of energy consumption in public buildings, and the legislative infrastructure was shaped by the Energy Efficiency Law No. 5627 [

1]. Within this framework, it is aimed for public institutions to realize energy efficiency investments with their own financing or through third-party investors. In line with Presidential Circulars No. 2019/18 and 2023/15, it is aimed to achieve 15% and 30% energy savings in public buildings, respectively, and the “Savings Target and Implementation Guide in Public Buildings” has been published in this direction [

2]. Although the EPC model allows public organizations to undertake renewable energy projects without having to make a direct capital investment, its performance-based payment structure makes financing through power savings easier.

There are two basic implementation formats in this model:

Guaranteed savings model

Shared savings model

In the guaranteed model, the public institution undertakes the investment financing while the contractor guarantees a certain level of energy savings. In the shared model, the investment is financed by the contractor and repayment is provided based on the savings achieved. Both models are of strategic importance in terms of reducing operational costs in public buildings, reducing energy dependency and supporting environmental sustainability goals.

Projects implemented within the scope of EPC in Türkiye generally focus on areas such as modernization of heating and cooling systems, installation of building automation systems, LED lighting conversions and implementation of solar power plants (SPP). In this context, public universities are considered among the important pilot areas for EPC applications due to their energy consumption profiles. Energy efficiency studies carried out within universities have the potential to not only provide cost savings but also increase the level of research, education and social awareness.

This study fills a research gap in the empirical evaluation of EPCs applied in renewable energy projects in Turkey, especially in public institutions, in this case a university campus. Existing studies mostly focus on policy frameworks or theoretical analyses, with limited use of actual production and financial data to assess the performance of EPCs. There is also a lack of integrated models that link predictions with actual energy efficiency outcomes in this context. Present study presents the technical and economic performance analysis of the solar power plant established within the scope of EPC in Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University campus. In the study, a multiple linear regression model was developed in order to determine the basic variables affecting the production cost, based on the energy studies and feasibility reports conducted before the plant investment. In the developed model, solar radiation, investment cost and electricity sales price were evaluated as independent variables; unit production cost was considered as the dependent variable. Model outputs were tested by comparing with real production data and the predictive power of the model was evaluated. This analysis provides the opportunity to test both the technical suitability and economic feasibility of an investment within the scope of EPC with numerical data.

In addition, the study analyzed indicators such as theoretical production, inverter output, specific energy, performance ratio, CO2 emission reduction and standard coal savings based on the production data of the relevant campus power plant. Thus, it was possible to evaluate EPC applications not only in terms of economic but also environmental performance. In particular, the evaluations made on the monthly distribution of the performance ratio reveal how the system responds to seasonal variations; in this respect, the study offers important implications for similar public investments. In this context, the study has a decision-support nature for policy makers, university administrations and investment firms regarding the dissemination of EPC applications in public institutions in Türkiye; it contributes to the holistic analysis of renewable energy investments on university campuses in terms of technical, economic and environmental aspects.

Thus, the novelty of this study lies in integrating quantitative regression-based analysis with real operational data to assess the economic feasibility of a solar power plant implemented in EPC in the public sector in Turkey. Unlike most existing studies, which often focus on policy or theoretical modeling, this study develops a multiple linear regression model using real data and validates it against 12 months of measured energy production. The approach used, validated in a Turkish university environment, allowed for the assessment of the technical and economic efficiency of EPC, but also the predictive reliability of the model. Also novel is the introduction of a comparative framework for planned, predicted and actual energy production results, which is a unique contribution to the literature on renewable energy financing and performance assessment.

The current study contributes to the science by introducing a data-driven methodology that combines technical, economic and environmental parameters to assess the performance of solar energy investments within an EPC. By presenting a repeatable model for estimating unit production costs and verifying system performance using real-world data, our study offers a practical decision support tool for policy makers and energy planners. Additionally, the study contributes to the research stream supporting the development of accurate and sustainable energy policies by quantifying both financial and environmental outcomes.

As a practical implication of the study, the study points to the creation of a methodology allowing decision-makers and practitioners to consistently evaluate the technical and economic viability of EPC-built energy projects. By enabling precise forecasting, investment planning, and performance verification, this technology helps to lower financial risks and guarantee contract compliance. The study provides useful analysis to help shape more efficient, data-driven renewable energy policies and to enhance decision-making procedures in public energy management.

2. Literature Review

Energy performance contracting (EPC) is widely implemented worldwide to increase energy efficiency and support sustainable development. However, EPC implementations face various obstacles such as financing difficulties, deficiencies in legal regulations, technical limitations and lack of awareness [

3,

4,

5,

6].

2.1. Main Challenges in EPC Applications

2.1.1. EPC Financing Challenges and Investment Payback Times

Since EPC projects require high initial costs, obtaining financing to cover these costs is one of the main challenges to be overcome [

7,

8,

9]. The limited financing options in public institutions cause private sector investments to remain insufficient [

10]. Furthermore, the high payback duration also makes such investments less desirable for investors [

11]. Especially in industries that are highly energy-intensive (e.g., iron-steel, cement, glass, chemical and paper industries and public buildings with heavy energy consumption such as public hospitals, universities and big service buildings), lack of financing is a key concern [

12]. In Smolina [

13], it is noted that local authorities must necessarily be engaged in the process for energy saving measures to be successful. Additionally, due to the lack of finance, energy efficiency measures; are normally perceived by private consumers such as homeowners, small businesses and individual consumers as high up-front cost solutions with long payback periods and limited applicability [

14]. In this context, public incentives can create a “doping” effect in the field of energy efficiency, both economically and ecologically [

15]. Therefore, the financing models of EPC projects should be reconsidered within the framework of long-term economic sustainability.

2.1.2. Deficiencies in the Legal and Regulatory Framework

In many countries around the world, there are no adequate legal regulations supporting the implementation of EPC projects. The legislation determined for EPC projects in the public sector does not fully meet the requirements [

16]. In the current legal framework, cooperation processes between energy service companies (ESCOs) and public institutions are not sufficiently clear [

17]. In addition, due to deficiencies in legislation, the interest of the private sector in EPC projects remains low [

18].

Although Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) projects aimed at improving energy efficiency in public buildings are being implemented, various difficulties are encountered in implementation due to deficiencies in the legal infrastructure. Ostrynskyi et al. [

19] draw attention to the inadequacy of the legal framework in EPC projects in Ukraine and the financial liquidity problems of the contracts. Similarly, Athigakunagorn et al. [

20] emphasize the limited contracting opportunities as well as the uncertainties regarding the relationship between emission reduction targets and EPC projects.

In addition, political interference and poor management practices in EPC projects may negatively affect project performance. Kiboi [

21] states that performance contracts cannot be effectively implemented in public institutions due to management deficiencies. The success of Energy Performance Contracts (EPC) largely depends on the effectiveness of public-private partnerships. However, the inadequacy of the structures responsible for energy management in public institutions constitutes a significant obstacle to this process [

22]. In many public institutions in Turkey, energy management units are generally positioned under the departments of construction works or technical works. This situation contradicts the nature of energy management, which requires an independent, holistic and specialized approach. However, energy management units should be defined as a separate department in the institutional structure and the personnel working in this department should have received special training as energy experts. In addition, the job description of these units should not be limited to monitoring the energy consumption of existing structures; it should also include evaluating and guiding in terms of energy efficiency in pre- and post-construction processes and ensuring that energy management systems such as ISO 50001 are implemented and monitored starting from public procurement processes. However, there are serious inconsistencies between the current legislation and practice in this context.

2.1.3. Measurement and Verification Problems

In order to achieve successful results in EPC projects, energy savings must be calculated accurately and performance monitoring processes must be implemented effectively. However, it is stated that data collection and measurement processes are costly and time-consuming [

23]. In addition, the limited competence of the experts who make the evaluation makes it difficult to evaluate the actual performance of EPC projects.

Accurate calculations are required for the effective implementation of studies such as insulation, window optimization and building envelope improvements, which are implemented to ensure energy efficiency in buildings [

24]. In addition, it is recommended to use dynamic energy performance analyzes instead of static data in calculations [

25].

As a result, financial incentives, legislative developments, technical expertise and awareness raising are required for the effective implementation of EPC projects. In particular, effective implementation of both local and international policies is of critical importance for the widespread use of EPC applications in the public sector.

2.1.4. Bureaucratic Processes and Lack of Institutional Awareness

In order to implement EPC projects, approvals must be obtained from many different public institutions, which slows down the processes [

26,

27]. The lack of sufficient knowledge of public institutions about EPC applications negatively affects the success of the projects [

13,

24]. In addition, bureaucratic obstacles in decision-making processes and lack of awareness about financing mechanisms make it difficult to implement projects [

6].

Deficiencies and uncertainties in financial support mechanisms of energy efficiency projects reduce the feasibility of projects [

28]. Lack of institutional awareness and inadequacies in strategic energy management also reduce the success rate of projects [

29]. In addition, the lack of sufficiently developed understanding of energy management in public institutions makes it difficult to implement projects effectively [

6].

2.1.5. EPC Financing Challenges and Investment Payback Times

The effective implementation of EPC Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) projects requires technical know-how, expert human resources and a strong technological infrastructure. However, the inadequacies in these areas in the public sector make the sustainability of these projects significantly difficult [

30,

31]. In particular, the lack of technical methods used in energy efficiency applications and the inadequacy of the infrastructure prevent EPC projects from producing the expected level of efficiency [

32].

In order to optimize energy efficiency in buildings, physical and thermal performance parameters such as thermal conductivity coefficient (U-value), thermal bridge formation, air tightness and solar gain of building components such as external walls, roof, windows and doors must be determined and improved accurately. However, in practice, inaccurate or subpar calculations of fundamental factors like wall-to-window ratio, window glass characteristics, and insulation thickness result in additional energy losses and inability to meet the desired level of energy performance. The other major obstacle to the adoption of EPC projects is the technical shortcomings in demand-side reactive power correction [

33]. A major aspect that lowers the efficiency of energy performance projects is the fact that the impact of interventions taken in an effort to increase the energy efficiency of public buildings tends not to achieve the projected saving rates [

34].

Another important factor affecting the success of EPC projects is the difficulties encountered in the selection of energy service companies (ESCOs). The difficulty of selecting the optimal ESCO is directly related to the lack of effective evaluation and monitoring mechanisms [

35]. New and sustainable selection mechanisms are needed to integrate ESCOs into projects in a way that can balance both profitability and energy efficiency. The lack of these mechanisms risks the long-term sustainability of projects [

36].

Finally, failure to adequately manage financial and technical risks in EPC projects carried out in public buildings leads to these projects not achieving their long-term efficiency and savings goals [

37,

38]. In this context, it is of great importance not only to increase the technical expertise capacity but also to develop risk management mechanisms.

2.2. Solution Suggestions

2.2.1. Diversification of Financing Options

Raising the level of financial incentives for Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) projects is imperative towards promoting their utilization in the public sector [

39]. Financing by states, investment tax benefits, and long-term loan facilities will all assist in making EPC projects lucrative. Long-term energy efficiency programs will also be able to continue if funding sources for renewable energy projects are expanded [

40].

One of the current financial barriers is the high initial costs of renovation projects aimed at achieving energy efficiency in public buildings. Especially radical renovations can cause operational disruptions and legal restrictions [

41,

42]. In order to prevent this problem, financial collaborations between the public and private sectors should be encouraged and efficient financing mechanisms implemented in European Union countries should be included in the adaptation process [

43].

2.2.2. Strengthening the Legal Framework

In order for EPC applications to be successfully implemented, the legislative infrastructure needs to be strengthened. Updating the legal framework and introducing more flexible regulations will increase the applicability of projects and increase public-private partnerships [

44]. Public institutions have deficiencies in strategic energy management and an adequate culture cannot be created for optimizing energy resources [

29]. In order to increase the effectiveness of EPC applications, the technical knowledge level of public institutions on energy management should be increased and the number of experts working in this field should be increased [

45].

2.2.3. Improving Measurement and Verification Processes

To increase the reliability of energy saving measurements, advanced Measurement and Verification (M&V) systems should be developed and independent audits should be implemented [

46]. In order to increase the effectiveness of EPC projects, verification methods in line with international standards should be adopted and realistic assessment of energy performance targets should be ensured [

47]. In particular, the lack of calibration of reference buildings makes it difficult to determine cost-optimum criteria and increases uncertainties [

48].

2.2.4. Increasing Public Awareness and Technical Capacity

Training programs should be organized for public institutions on EPC and technical capacity should be increased [

49,

50]. In order to ensure energy efficiency in public buildings, structural problems such as high specific energy consumption and insufficient heat accumulation resistance should be focused on [

30].

Programs to train experts in energy efficiency and EPC should be implemented in cooperation with universities and the private sector [

45]. In particular, problems such as financial inequalities and high variable cost coefficients experienced in the renovation of public buildings limit the applicability of EPCs [

51].

As a result, in order to effectively implement EPC projects, financing options need to be expanded, legislative regulations need to be strengthened, measurement and verification processes need to be improved, and public awareness needs to be increased. When these approaches are considered together, the continuity and expansion of energy efficiency projects can be ensured.

3. Materials and Methods

This study proposes a quantitative method based on regression analysis to assess the economic feasibility of a 1710.72 kWp solar power plant (SPP) investment implemented within the scope of Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) in a university campus. The methodological approach consists of three stages: applied data collection, model development and production estimation.

3.1. Conducting Energy Audits and Collecting Data

In the Energy Survey conducted at Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University campus (

Figure 1), the annual total electricity consumption was determined as approximately 2,144,590.43 kWh, and the annual average production capacity of the planned solar power plant was predicted to be 2,464,069.60 kWh. The system to be installed was designed to have a fixed 0° slope and a 187° south orientation; the performance ratio was calculated as 83% and the specific production capacity as 1,434.9 kWh/kWp-year (

Table 1). These data were obtained from pre-feasibility studies and technical study reports.

3.2. Regression Model Development

A multiple linear regression model was developed to analyze the determinants of the unit production cost (TL/kWh) of the solar power plant investment. The variables used in the model are listed below:

Dependent Variable:

Unit production cost (TL/kWh)

Independent Variables:

Annual solar radiation (kWh/m2-year)

Solar power plant investment cost (TL/kWp)

Electricity sales price (kr/kWh)

The general form of the model is expressed by the following equation:

Where:

Y - Unit production cost (TL/kWh)

X1 - Annual solar radiation (kWh/m2-year)

X2 - Solar power plant investment cost (TL/kWp)

X3 - Electricity sales price (kr/kWh)

β0 - Constant term

β1, β2, β3 - Coefficients of independent variables

ε - Error term

The data used in the model is based on technical and financial feasibility reports created during the planning phase of the campus-scale solar power plant investment. Taking 2022 as reference, the total investment cost was determined as 1,197,504 USD (approximately 18,329,166 TL, 1 USD = 18.21 TL). The electricity unit sales price was taken as 313.82 kr/kWh (

Table 2). The estimation accuracy of the regression model was analyzed by comparing it with the 12-month production data of 2,423,472.28 kWh realized on the campus.

Regression Model Validity Outputs:

R2 (Coefficient of Determination): 0.873

F-Test Significance Level: p < 0.01

t-tests (independent variables): p < 0.05 (significant for all variables)

According to the model output, the annual estimated production value is calculated as 2,778,882 kWh. The difference between this value and the actual production value is ±355,409.72 kWh. The margin of error (MAPE) is calculated according to the following formula:

Error Rate (%) = |Estimated - Actual| / Actual × 100 = |2,778,882 - 2,423,472.28| / 2,423,472.28 × 100 ≈ 14.67%

This ratio is within acceptable limits and shows the predictive ability of the model

3.3. Electricity Production Estimation and Calculation Formula

Monthly production estimates of the solar power plant are calculated using the following formula based on solar radiation values:

Where:

Ei - Energy expected to be produced in month i (kWh)

Ri - solar radiation measured in the ith month (kWh/m2)

A - Panel surface area (m2) → 3600 m2

H - Panel efficiency → 0.18 (i.e., 18%)

The estimated monthly production values calculated with this method are given in

Table 3.

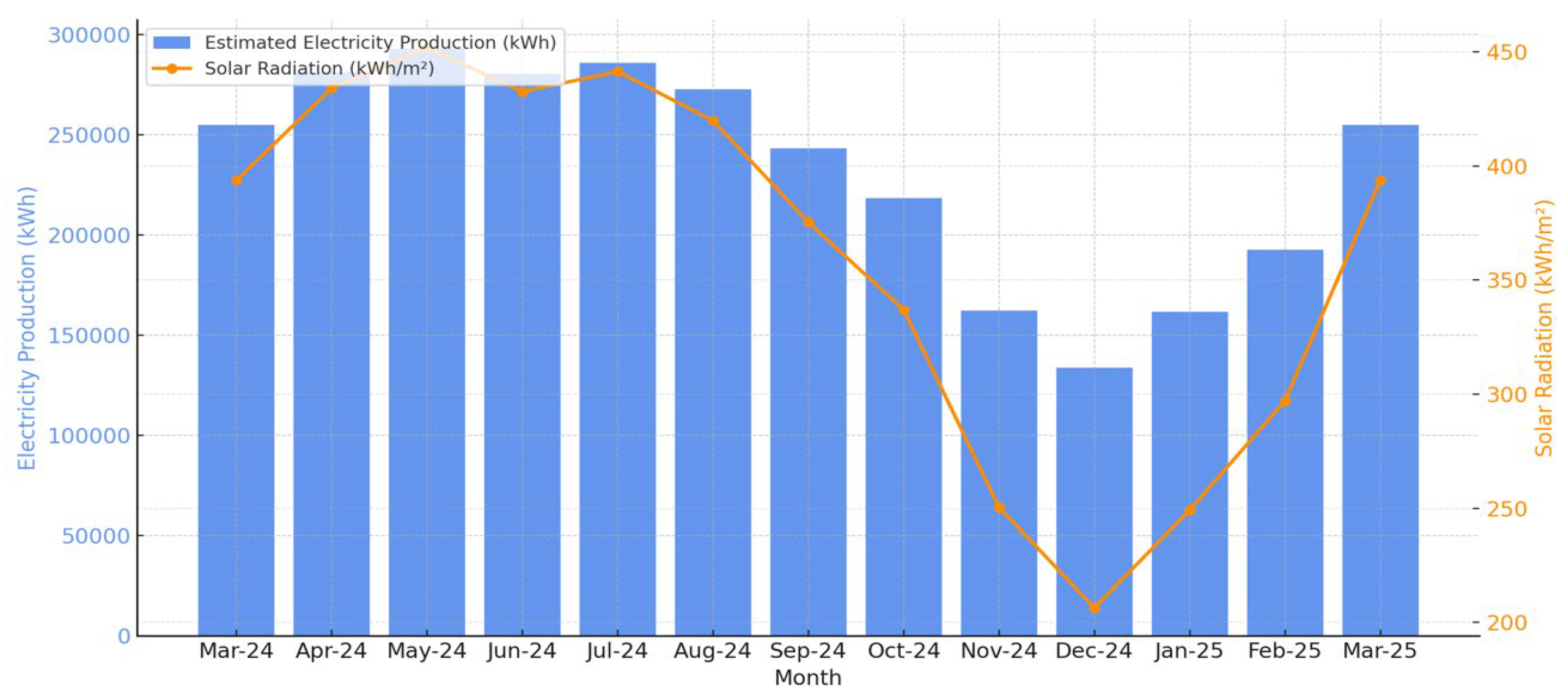

The

Figure 2 shows the estimated monthly electricity production (kWh) and the corresponding solar radiation (kWh/m

2) values, according to the forecasts made before the start of the project.

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the estimated monthly electricity production of the solar power plant of Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University campus in Antalya province between March 6, 2024 and March 6, 2025, and the solar radiation (radiance) values affecting this production. The graph visually presents two basic data:

The blue bars represent the amount of electricity (in kWh) the system is projected to produce in that month.

The orange line shows the solar radiation values (kWh/m2) provided by Antalya Meteorology Directorate for the same month and optimized with design software.

The radiation data used in this study were obtained from the multi-year insolation statistics provided by the Turkish Republic Meteorological Service (MGM) for Antalya province and were simulated according to the system installation characteristics (slope, orientation, panel type). As a result of this optimization for each month, forecast data as close as possible to the real conditions were obtained.

When the graph is examined, it is seen that both solar radiation and electricity production reach their highest levels, especially between May and July. For example, in June, the system is expected to produce approximately 280,256 kWh in return for 432.49 kWh/m2 radiation. This parallel clearly shows the sensitivity of photovoltaic systems to solar radiation.

On the other hand, a significant decrease in both radiation and production levels was observed between November 2024 and January 2025. This decrease is not due to system efficiency, but rather to seasonal variability and the decrease in daylight hours. Overall, the graph successfully models the seasonal behavior of the system and demonstrates that performance expectations within the scope of EPC should be based on climatic foundations. The use of insolation data from reliable sources in production estimation directly affects both the decision-making processes of investors and the contract planning of public administrations.

4. Results

In this study, the first year-end production data of the 1710.72 kWp solar power plant (SPP) established on the University campus were analyzed. The production was evaluated in line with the performance monitoring and forecasting models carried out within the scope of the Energy Performance Contract (EPC). The findings include both actual production data obtained from remote reading devices and estimated production values based on meteorological data.

4.1. Electricity Production Estimation and Calculation Formula

Through two separate energy analyzers belonging to the system, energy production was achieved between March 6, 2024 and March 6, 2025, at the following values (

Table 4):

4.2. Planned Production and Economic Gain

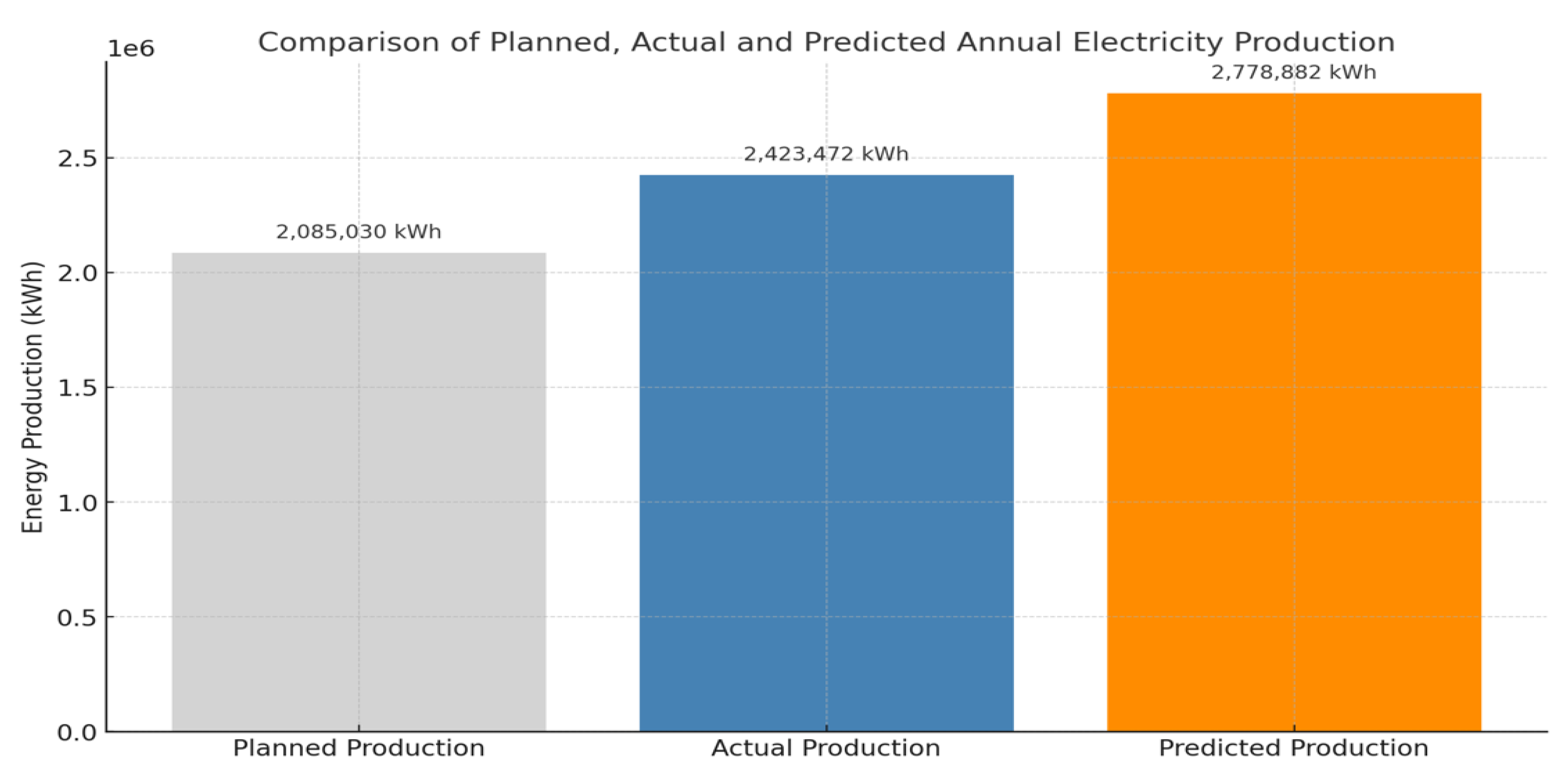

According to the Energy Performance Contract, the contractor company planned to produce 2,085,030.40 kWh annually. Accordingly, the expected income is 8,777,978.00 TL. However, the actual production and income exceeded the planned values.

When

Table 5 is evaluated, the actual production amount was approximately 16.2% above the contract targets. This shows that the performance of the system was higher than expected and the environmental conditions and optimization were successfully implemented.

4.3. Monthly PV Performance Analysis Obtained from Inverter Remote Monitoring System

An analysis of the monthly PV system performance is shown in

Table 6, detailing energy production, CO

2 mitigation, and coal savings.

In this section, the production estimation model developed based on meteorological data and technical system parameters in the methodology part of the study and the actual production data obtained in the field were comparatively analyzed.

Estimated annual production amount: 2,778,882 kWh

Actual production amount: 2,423,472.28 kWh

Planned production (according to EPC contract): 2,085,030.40 kWh

Estimation Error Margin: Error Rate (%) = |2,778,882 − 2,423,472.28| / 2,423,472.28 × 100 ≈ 14.67%

Figure 3 aims to present the annual electricity production values obtained from the solar power plant in comparison with the planned values specified in the energy performance contract and the theoretical production calculated with the forecast model. The graph contains three main components:

Grey column (Planned Production): Represents the production amount committed by the contractor company within the scope of EPC, which is 2,085,030.40 kWh. This value is the minimum performance level that forms the basis of the contract.

Blue column (Actual Production): Indicates the production amount of 2,423,472.28 kWh based on field measurements. This amount is approximately 16% above the planned production, indicating that the technical capacity and operating conditions of the system performed better than expected.

Orange column (Predicted Production): It reflects the theoretical production amount of 2,778,882.00 kWh calculated with the multivariate regression model and system efficiency parameters using Antalya Meteorology data. This value shows the production limit of the system based on the maximum climatic potential.

When the three data points are evaluated together, it is seen that the actual production is both above the planned value and within the acceptable deviation limits compared to the estimated model. The difference can be attributed to the effects of environmental factors such as seasonal variations during the year, short-term production interruptions, dust and shading.

This chart is a powerful tool that can provide decision makers with sound insights in performance verification, risk assessment and financial analysis processes in EPC projects.**

This graph visually demonstrates the difference between the projected performance targets of the study and the actual outputs in the field. The realized production shown in the blue column was 16% higher than the contractually planned production shown in gray. This shows that the commitments under the energy performance contract were technically successfully fulfilled.

However, the estimated production value represented by the orange column is 14.7% higher than the field data. This deviation is due to the use of theoretical maximum irradiance data by the forecast model, seasonal climate variability, and within-system yield losses.

This difference shows that the forecast model remains within acceptable error limits and that seasonal fluctuations have a direct effect on production. The graphical evaluation reveals that the methodological calculations are compatible with the system reality and points to the importance of constructing the performance guarantee processes within the scope of EPC on scientific foundations.

General Assessment When the forecast study conducted within the scope of EPC was compared with the actual data obtained from the field, it was determined that the system was working above the predicted performance. The fact that the realized production was above the contract targets supports both the technical adequacy and the accuracy of the forecast system. At the same time, it is understood that the system is working with high efficiency in terms of environmental contributions (CO2 emission prevention and coal savings).

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Solar Power Plant This study comprehensively evaluated the first year production performance of the 1710.72 kWp capacity solar power plant (SPP) established in Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University campus, a public university in Antalya, within the scope of the Energy Performance Contract (EPC). The applied multiple linear regression model was supported by the Antalya Meteorology data and estimated production calculations based on field parameters. At the same time, the technical, economic and environmental performance of the system was analyzed by evaluating the actual production data and environmental gains.

The power plant has successfully performed technically and economically, exceeding the production amount committed within the scope of EPC by 16.2%. The production realized was measured as 2,423,472.28 kWh, which is above both the amount planned in the contract (2,085,030.40 kWh) and the economic savings foreseen for the administration. According to Article 9.1 of EPC, the payment to be made to the contractor is determined only according to the guaranteed production amount. Therefore, this excess production has been evaluated as a value working in favor of the administration.

However, the estimated production value was calculated as 2,778,882 kWh, and there was a deviation of approximately 14.67% between the actual production and the model. This deviation can be explained by seasonal fluctuations, environmental effects and efficiency losses in the system. However, this difference shows that the reliability level of the model is within acceptable limits.

Although only the regression model and estimation method were used in this study, the integration of more advanced artificial intelligence-based algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithm, particle swarm optimization, artificial neural networks) is suggested for future applications. Such optimization algorithms will strengthen the accuracy of decision support systems by increasing the estimation precision and provide more stable predictions, especially in long-term energy planning and production guarantee calculations.

Considering the environmental aspect of the study, it was seen that a total of 1,168.64 tons of CO2 emissions were prevented in the first year of the plant and approximately 950 tons of standard coal were saved. These data provide a concrete contribution to Türkiye’s goals of combating climate change and its vision of sustainable development until 2030.

Turkey is a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, has ratified the Kyoto Protocol and put the Paris Agreement into effect. In this context, climate-friendly energy production and greenhouse gas reduction are among the basic political goals while continuing economic development. EPC applications provide a mechanism directly compatible with these goals; making renewable energy production in public buildings financial.

In conclusion, this preliminary application shows that EPC can be adopted not only as a financial but also as a technical and environmental strategy. In future applications, integrated forecasting models supported by optimization algorithms based on multidimensional analysis of meteorological data are suggested and it is emphasized that national energy policies should be supported by more data-based tools.

Our study is not free from research limitations. One of the key limitations of this study is the use of a multiple linear regression model for analyses, which may not fully capture the complex, nonlinear interactions between environmental and technical variables affecting solar energy production. Furthermore, our analysis is based on a single case, i.e., a solar power plant located on one university campus, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other geographical regions or institutional environments. A challenge for future research may therefore be to verify the applied approach in other public entities. Next, the study includes a limited number of variables, e.g., it assumes static electricity prices and investment costs, which certainly does not include future market dynamics or inflation trends. Future studies could therefore attempt to expand the number of variables subject to verification or alternatively include a sensitivity analysis of the model. Finally, it is suggested that the use of advanced methods based on artificial intelligence is crucial in the analyzed topic, which was not used in the current analyses, and therefore may indicate future research directions and research challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C. M.O., K.W.,O.P.; methodology, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C., M.O.; software, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.C., K.W.; validation, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C., O.P.; formal analysis, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C., M.O.; investigation, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.C.; resources, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C..; data curation, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.C. K.W.,O.P.; writing—review and editing A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C. K.W., M.U., O.P.; visualization, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.C., M.O.; supervision, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C.; project administration, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.AT., A.C.; funding acquisition, A.A., M.N., K.T., L.A. M.K., A.C., M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

If AI was used, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (ETKB). Energy Performance Agreements and National Energy Projects Development Report; 2022. Available online: https://enerji.gov.tr/bilgi-merkezi-enerji-verimliligi-ulusal-ve-uluslararasi-projeler-gelistirme (accessed on 20.05.2025).

- Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change (ÇŞİDB). Savings Target and Implementation Guide in Public Buildings (2024–2030); 2023. Available online: https://kamuguclendirme.csb.gov.tr/proje-hakkinda-genel-bilgi-i-101905 (accessed on [Insert Access Date]).

- Akkoç, H.N.; Onaygıl, S.; Acuner, E.; Cin, R. Implementations of Energy Performance Contracts in the Energy Service Market of Turkey. Energy for Sustainable Development 2023, 76, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernetska, Y.; Borychenko, O.; Yehorenko, A. Determination of Optimal Packages of Energy Efficient Measures for Public Buildings. POWER ENGINEERING economics technique ecology 2023, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, Z.H.; Ludin, N.A.; Junedi, M.M.; Affandi, N.A.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Teridi, M.A.M. A Rational Plan of Energy Performance Contracting in an Educational Building: A Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medved, P. EPCHC - Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) Model for Historic City Centres. Acta Innovations 2022, 47, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytko, J. The Role of Public Sector Entities in Improving Energy Efficiency—Characteristics of Energy Performance Contracts. Studia Iuridica 2023, 101, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimukhamedova, A. Role of Energy Intensity and Investment in Reducing Emissions in Türkiye. Eurasian Journal of Economic and Business Studies 2024, 68, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Suder, M.; Kusa, R.; Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Duda, J.; Niemiec, M. The Limited Financing Options in Public Institutions Cause Private Sector Investments to Remain Insufficient. Energies 2020, 13, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade, J.; Cruz, C.O.; Silva, C.M. Improving the Efficiency of Energy Consumption in Buildings: Simulation of Alternative EnPC Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, G. A Modeling Framework for the Diffusion of Low Carbon Energy Performance Contracts. Energy Efficiency 2020, 13, 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, P.; Cirik, K.; Şakalak, E.; Sever, A.E. A Critical Examination of the Construction Sector in Turkey in Terms of Sustainability. International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolina, L. Energy Saving Methods during the Life Cycle of Buildings and Structures: Energy Service Contracts. E3S Web of Conferences 2024, 549, 05007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Sikora, J.; Niemiec, M.; Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Suder, M.; Kuboń, M.; Borkowski, T.; Malik, G. Solar Power: Stellar Profit or Astronomic Cost? A Case Study of Photovoltaic Installations under Poland’s National Prosumer Policy in 2016–2020. Energies 2021, 14, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Caponi, P.; Cecere, C.; Sciubba, E. An Exercise-Based Analysis of the Effects of Public Incentives on the So-Called “Energy Efficiency” of the Residential Sector, with Emphasis on Primary Resource Use and Economics of Scale. Frontiers in Sustainability 2024, 5, 1397416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, D.G.; Cesur, F. A Study for the Improvement of the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) System in Turkey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Energy Performance Contracting from the Perspective of the Public Sector—A Bibliometric Analysis. Business 2022, 14, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacinkiewicz, D.; Słotwiński, S. The Statutory Model of Energy Performance Contracting as a Means of Improving Energy Efficiency in Public Sector Units as Seen in the Example of Polish Legal Policies. Energies 2023, 16, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrynskyi, V.; Nykytchenko, N.; Sopilko, I.; Krykun, V.; Mykulets, V.Y. EPC-Contracts Using in Renewable Energy: Legal and Practical Aspect. Revista Amazonia Investiga 2022, 11, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athigakunagorn, N.; Limsawasd, C.; Mano, D.; Khathawatcharakun, P.; Labi, S. Promoting Sustainable Policy in Construction: Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions through Performance-Variation Based Contract Clauses. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 448, 141594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiboi, A.W. Management Perception of Performance Contracting in State Corporations. International Journal of Supply Chain and Logistics 2023, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepbaşlı, A.; Eltez, M. A.; Eltez, M. A Survey on Building Energy Management Systems at Turkish Universities. In Energy and the Environment; Begell House, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Võsa, K.-V.; Ferrantelli, A.; Tzanev, D.; Simeonov, K.; Carnero, P.; Espigares, C.; Navarro Escudero, M.; Quiles, P.V.; Andrieu, T.; Battezzati, F.; et al. Building Performance Indicators and IEQ Assessment Procedure for the Next Generation of EPC-s. E3S Web of Conferences 2021, 246, 13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, A. The Effect of Thermal Insulation on Building Energy Efficiency in Turkey. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers–Energy 2022, 175, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltsios, S.; Tsolakis, A.C.; Fokaides, P.; Katsifaraki, A.; Cebrat, G.; Jurelionis, A.; Contopoulos, C.; Chatzipanagiotidou, P.; Malavazos, C.; Ioannidis, D.; Tzovaras, D. D^2EPC: Next Generation Digital and Dynamic Energy Performance Certificates. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cin, R.; Acuner, E.; Onaygil, S. Analysis of Energy Efficiency Obligation Scheme Implementation in Turkey. Energy Efficiency 2021, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Marijuan, A.; Garay-Martinez, R.; de Agustín-Camacho, P.; Eguiarte, O. Assessment of the Potential of Commercial Buildings for Energy Management in Energy Performance Contracts. In Proceedings of the International Conference; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzani, D.; Stavrakas, V.; Santini, M.C.; Thomas, S.; Rosenow, J.E.; Flamos, A. Pioneering a Performance-Based Future for Energy Efficiency: Lessons Learned from a Comparative Review Analysis of Pay-for-Performance Programs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpa, F.S.E.; Cunha, R.A.D.; Nascimento, L.A. Energy Efficiency through Analysis of the Contracted Demand, Consumption and Framework Group “A” Tariff: Case Study at IFPA Parauapebas Campus. Braz. J. Dev. 2022, 8, 65088–65098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shen, Y.; Xia, Y. Research on the Driving Factors for the Application of Energy Performance Contracting in Public Institutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, M.; Wernert, C.; Chartier, A. Social Housing Net-Zero Energy Renovations with Energy Performance Contract: Incorporating Occupants’ Behaviour. Urban Planning 2022, 7, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayın, S.; Augenbroe, G. Optimal Energy Design and Retrofit Recommendations for the Turkish Building Sector. Journal of Green Building 2021, 16, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Sun, Z.; Rao, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhang, R.; Guo, W.; Liu, Z. Research on Energy Performance Contracting Mode of Demand-Side Reactive Power Compensation. Highlights in Science Engineering and Technology 2024, 90, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Życzyńska, A.; Majerek, D.; Suchorab, Z.; Żelazna, A.; Kočí, V.; Černý, R. Improving the Energy Performance of Public Buildings Equipped with Individual Gas Boilers Due to Thermal Retrofitting. Energies 2021, 14, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, Y. Optimum Selection of Energy Service Company Based on Intuitionistic Fuzzy Entropy and VIKOR Framework. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 186572–186584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B. Design of Balanced Energy Savings Performance Contracts. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1401–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z.; Othman, M.N.; Zainuddin, H.; Rosdi, M.J.; Khallawi, A.R. Systematic Review of Risks in Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) Projects. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 48, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z.; Othman, M.N.; Zainuddin, H.; Rosdi, M.J.; Khallawi, A.R.; Adip, M.A. Risks in Measurement and Verification (M&V) in Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) Projects: A Systematic Review. Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Sciences and Engineering Technology 2024, 53, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniello, L.; Morea, D.; Paolone, F.; Tiscini, R. Energy Performance Contracting and Public-Private Partnership: How to Share Risks and Balance Benefits. Energies 2020, 13, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamov, D.; Ilyushin, P.V.; Minarchenko, I.; Filippov, S.; Suslov, K. The Role of Energy Performance Agreements in the Sustainable Development of Decentralized Energy Systems: Methodology for Determining the Equilibrium Conditions of the Contract. Energies 2023, 16, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anarene, B. Revolutionizing Energy Efficiency in Commercial and Institutional Buildings: A Complete Analysis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 12, 7444–7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, M.; Sikora, J.; Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Komorowska, M. Assessment of the Possibilities for the Use of Selected Waste in Terms of Biogas Yield and Further Use of Its Digestate in Agriculture. Materials 2022, 15, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Maseda, J.J.; Castro-Santos, L.; Graña-López, M.Á.; García-Diez, A.I.; Filgueira-Vizoso, A. Analysis of Contracts to Build Energy Infrastructures to Optimize the OPEX. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiernsson, A.; Geijer, M.; Malafry, M. Legal Aspects on Cultural Values and Energy Efficiency in the Built Environment—A Sustainable Balance of Public Interests? Heritage 2021, 4, 3507–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksin, F.N.; Selçuk, S.A. Energy Performance Optimization of School Buildings in Different Climates of Turkey. Front. Civ. Eng. 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, M.M.; Salvalai, G.; Della Valle, N.; Giulia, M.; Bertoldi, P. Towards Harmonizing Energy Performance Certificate Indicators in Europe. J. Civil Eng. 2024, 95, 110323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Contract Decisions Analysis of Shared Savings Energy Performance Contracting Based on Stackelberg Game Theory. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 385, 02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, D.; Yousif, C.; Cellura, M.; Camilleri, L.; Guarino, F. Assessment of Building Energy Modeling Studies to Meet the Requirements of the New Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 127, 109886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, M. A Public Energy Policy Proposal for Turkey in the Light of Econometric Findings. Journal of Kırklareli University Social Sciences Vocational School 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakosta, C.; Mylona, Z. A Methodological Framework for Enhancing Energy Efficiency Investments in Buildings. In Proceedings of the LIMEN International Scientific-Business Conference—Leadership, Innovation, Management and Economics; Integrated Politics of Research; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Lam, P.T.I.; Lee, W.L. Risks in Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) Projects. Energy Build. 2015, 92, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).