1. Introduction

In recent years, the medical and scientific communities have witnessed a surge of interest in the potential therapeutic applications of cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive compound derived from the Cannabis sativa plant. Cannabinoids (CB’s) have long been used as part of chemotherapy treatments for toxicity induced indications. CB’s are effective in reducing nausea often associated with chemo and radio therapy. However, CB’s have also been shown to have anti-proliferative effects on a number of cancers to include breast, colorectal, lung, paraganglioma, and brain both in vitro and in vivo [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Accumulating evidence suggests that CBD may exert anticancer effects through multiple mechanisms, including apoptosis induction, cell cycle regulation, inhibition of angiogenesis, and attenuation of migration and invasion [

3,

7].

These effects are due in part to signaling through endogenous cannabinoid receptors (CB-R’s). These receptors are present on several cancer cell lines and directly correlates with aggressiveness [

4]. These effects have been shown on both estrogen positive and negative breast cancer cell lines as well as in models of gliomas [

2,

4]. Of the over 500 compounds in the C.

sativa plant, 60 have been classified as CB’s with two, Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD), having been extensively tested in a research setting.

However, CB’s effect on cancer cell metabolism has yet to be examined. Cancer cell metabolism has been a heavily researched topic, often attributed to Otto Warburg’s work. Warburg postulated that all cancers suffered from an irreversible inhibition of mitochondrial metabolism, leaving cancer cells wholly dependent on glycolysis and sugar for energy production [

10]. In recent years, however, we have seen the complexity of cancer cell metabolism as studies show that glutamine and fatty acids also play a role in cancer growth and survival [

11,

12,

13]. However, targeting cancer cell metabolism has remained an interesting yet elusive target for novel therapies. It has been suggested that CB’s may exert their anti-proliferative effects partly through changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, suggesting a metabolic consequence of treatment with CB’s [

14].

Aside from their use in cancer therapy, CB’s have been shown to influence pain and inflammation through their modulation of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and thioredoxin reductase as well as it’s modulation of the inflammatory marker NFkB [

15,

16]. Application of CB’s therefore reach wide from cancer to Parkinson’s, and even to chronic pain [

17,

18]. Furthermore, CBD has been shown to modulate several neuropsychiatric disorders with the potential to modulate psychotic, addictive, and depressive states [

19].

Currently, the FDA has not approved any cannabis products for the treatment of diseases. It has however approved several cannabis-derived and synthetic THC-like compounds for the treatment of seizures and AIDS associated weight loss (Epidolex, Marinol, Syndros, and Cesamet). Research on large human cohorts is limited partly because important metabolic studies are lacking.

In this study, our aim was to understand the metabolic changes of malignant fibroblast (Malme-3M) cells compared to benign fibroblasts (BJ) cells after treatment with CBD.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The Malignant fibroblast (Malme-3M, ATCC Catalog No. HTB-64) were grown in an IMDM medium (gibco, Catalog No.12440-053) with 10% FBS. The benign fibroblasts (BJ) cell line were grown in a DMEM medium (gibco, Catalog No. 11965-092) with 10% FBS.

Grow cells according to specific cell conditions in T75 flasks first. When the cell has reached logarithmic phase (80% confluency), then the cells were seeded into 60-mm dishes in quintupled. The seeding density of BJ was 3 x105 cells /each dish and for Malme-3M was 1.2 x 106 cells/each dish. Then the cells were incubated for 24 hours before treatment. Cells were then treated with DMSO (vehicle, Sigma Catalog No D2650-100ML) or CBD (Cayman Chemical Catalog No. 90080) and incubated at 37 °C CO2 incubator for 72 hours before doing the metabolite measurements.

2.2. Dosing with CBD

For benign fibroblasts (BJ), the dose with CBD is 12.5 µM and for malignant fibroblast (Malme-3M), the dose with CBD is 16µM.

2.3. Metabolite Measurements

Triplicate 60-mm dishes of cultured cells were used for the extraction of intracellular metabolites. The culture medium was aspirated from the dish and cells were washed twice by 5% mannitol solution (5 mL first and then 1 mL). The cells were then treated with 400 µL of methanol and left at rest for 30 s in order to inactivate enzymes. Next, the cell extract was treated with 275 µL of Milli-Q water containing internal standards (H3304-1002, Human Metabolome Technologies, Inc., Tsuruoka, Japan) and left at rest for another 30 s. The extract was obtained and centrifuged at 2,300 ×g and 4ºC for 5 min and then 350 µL of upper aqueous layer was centrifugally filtered through a Millipore 5-kDa cutoff filter at 9,100 ×g and 4ºC for 180 min to remove proteins. The filtrate was centrifugally concentrated and re-suspended in 50 µL of Milli-Q water for CE-MS analysis.

Metabolome measurements were carried out through a facility service at Human Metabolome Technology Inc., Tsuruoka, Japan.

3. Results

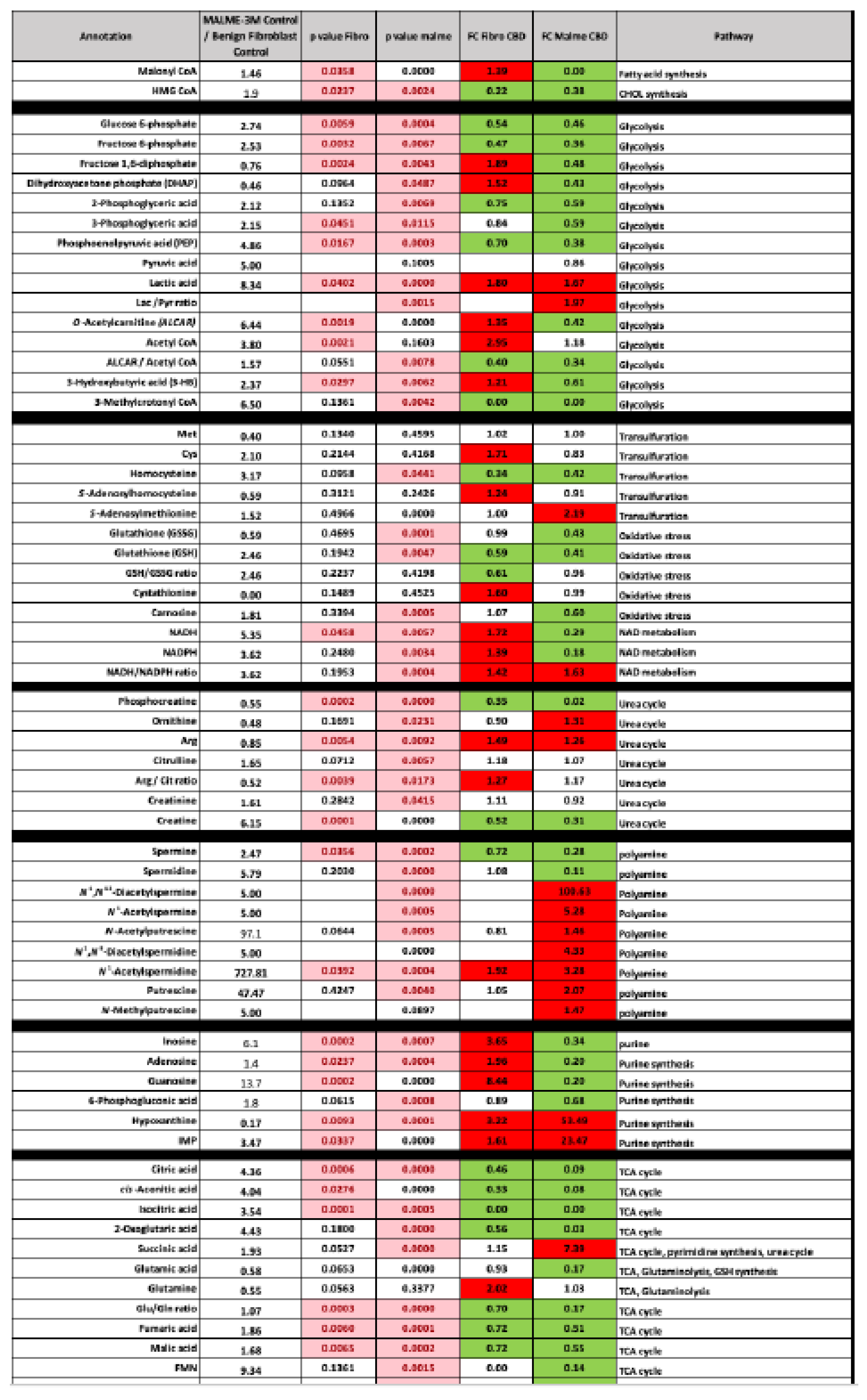

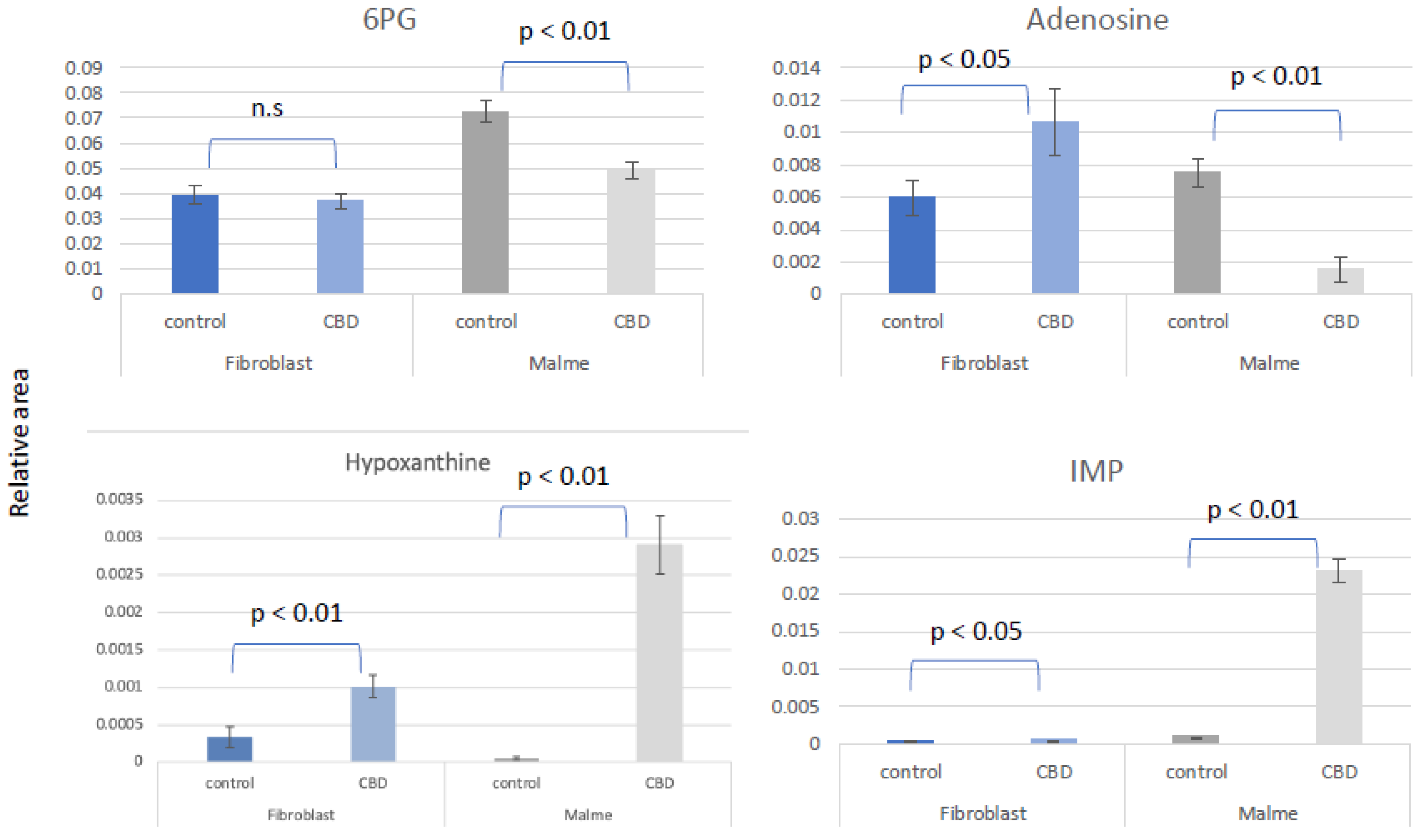

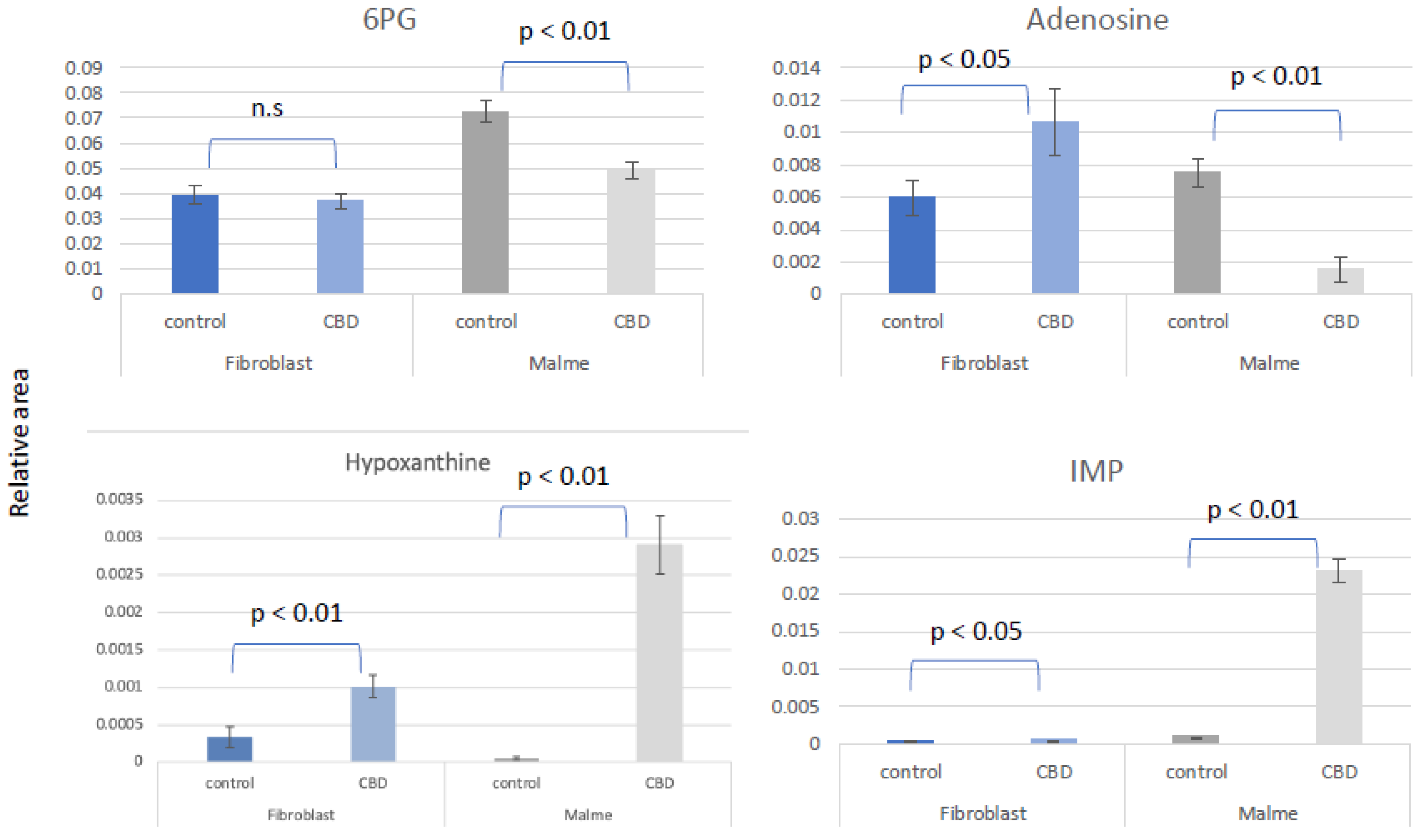

In this study we aimed to understand metabolic changes in both a normal BJ Fibroblast cell line compared to its oncogenic counterpart, the Malme-3M cell line, when pre-treated with cannabidiol (CBD). We first interrogated cellular wide changes and their associated metabolic processes. Fibroblast and Malme-3M cell lines were treated with 12.5 and 16 μm CBD which respectively represents the IC50 for each cell line. As shown in

Figure 1 we saw a larger number of differentially regulated metabolites in the Malme-3M cell line treated with CBD relative to the control fibroblast cell line. Of note, we saw significant changes in several key metabolic pathways to include glycolysis, glutaminolysis, redox maintenance, urea cycle and the TCA cycle.

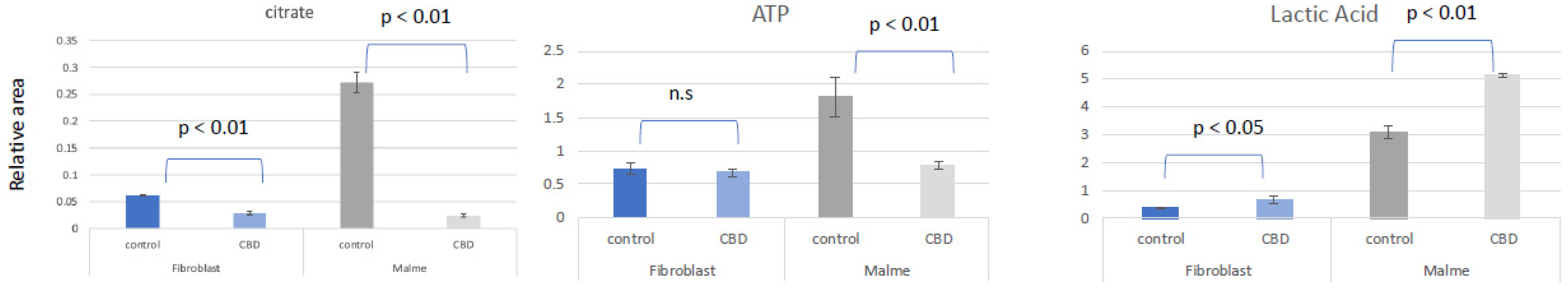

While both the benign BJ fibroblast cells and Malme-3M cells showed a significant decrease in citrate as shown in

Figure 2, there was only a corresponding decrease in ATP in the Malme-3M cell line. Glycolytic activity was correspondingly increased in the Malme-3M cell line in a likely attempt to maintain ATP levels.

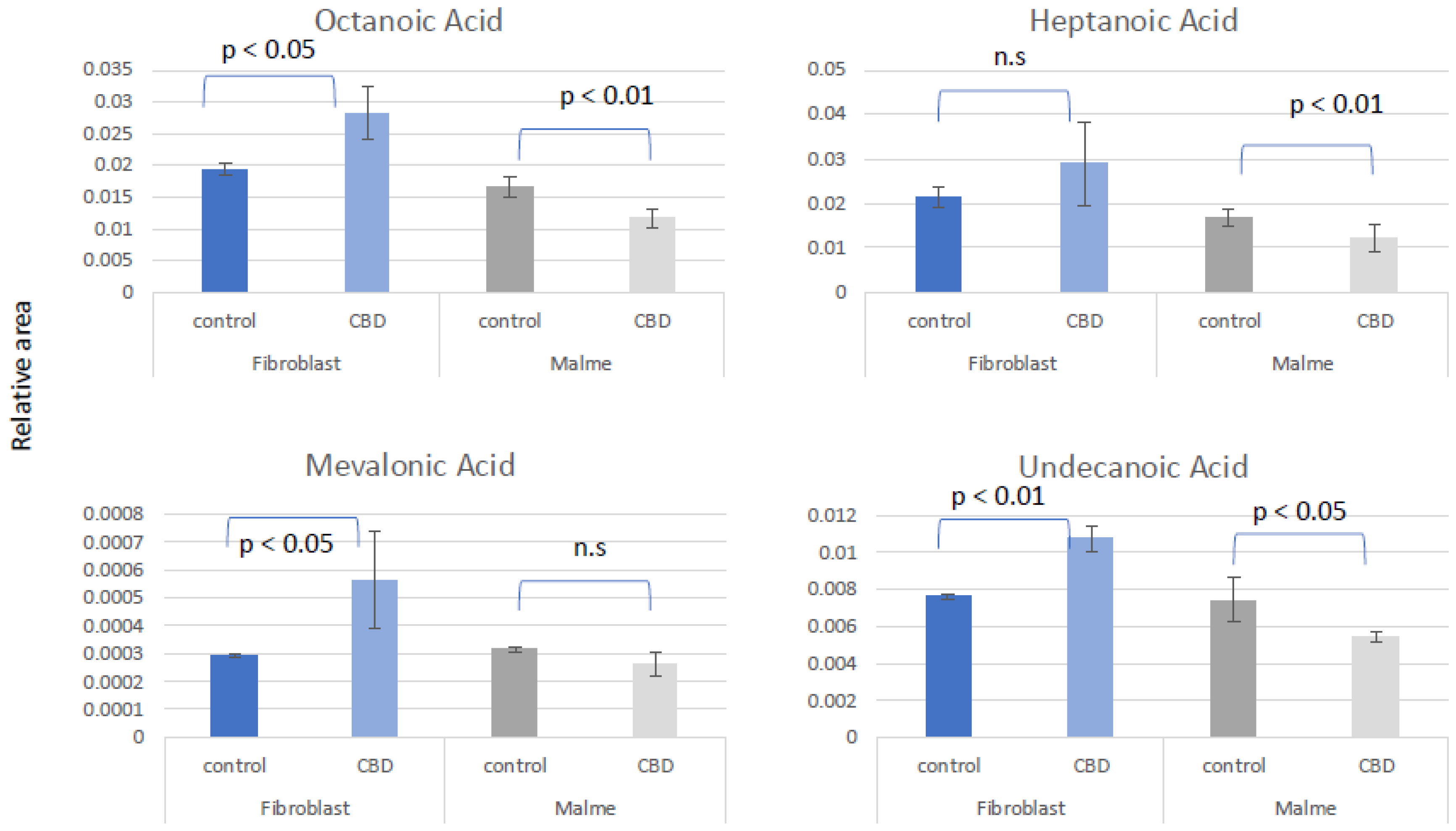

By examining the change in short and medium chain fatty acids, we conclude that fatty acid metabolism is elevated in BJ fibroblasts cells because of CBD treatment as shown in

Figure 3. This suggests that the normal fibroblasts respond to reductions in TCA cycle activity with an increase in fatty acid oxidation to maintain constant ATP levels. In contrast, there is an overall significant decrease or no change in the Malme-3M cells, consistent with an inhibited TCA cycle.

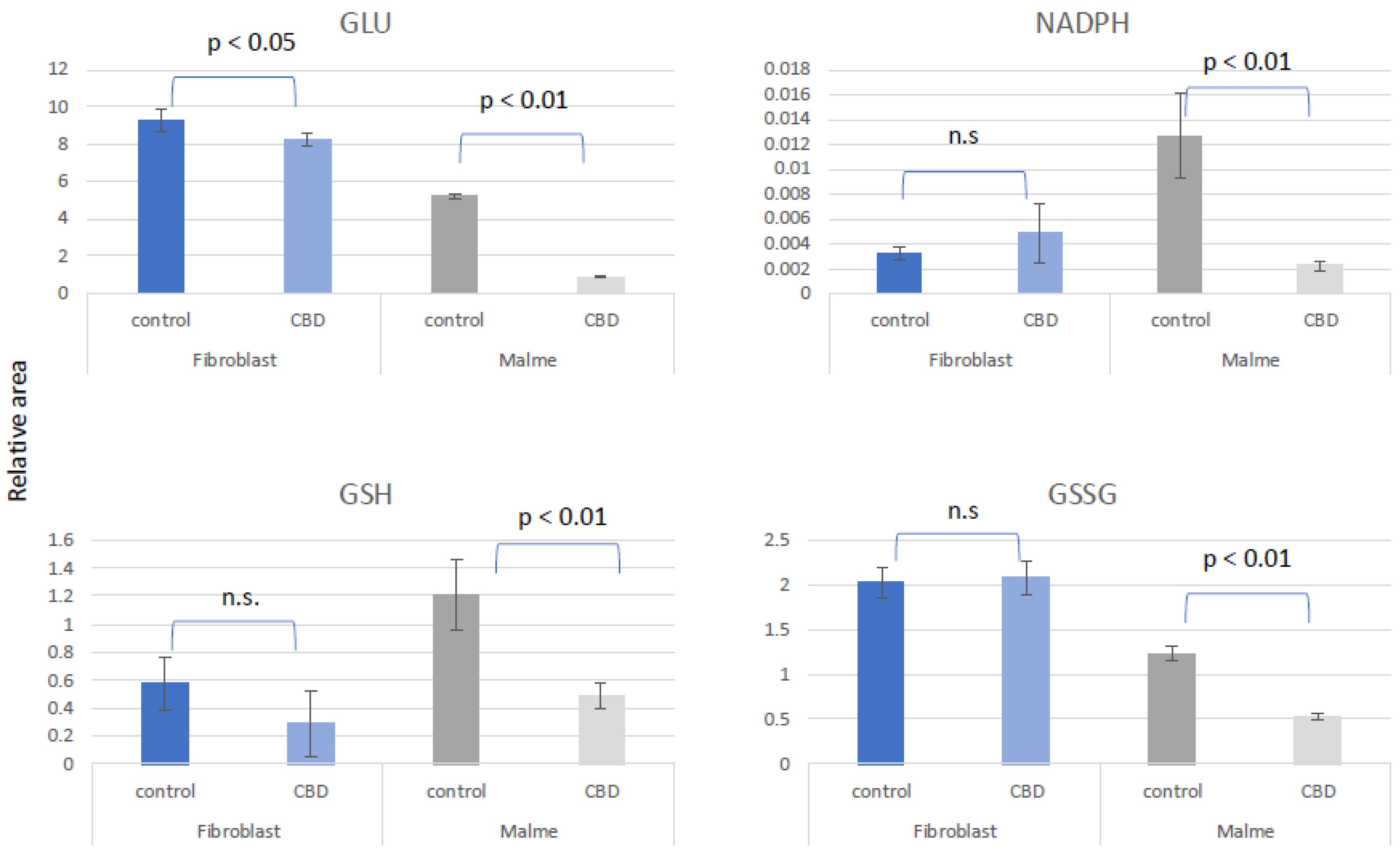

We suggest that CBD results in potential oxidative stress or greater susceptibility to oxidative stress in tumor cells lines only. In

Figure 4, we show that glutamate was significantly reduced in the Malme-3M cells, resulting in a reduction in both GSH and GSSG, likely affecting de novo glutathione synthesis. NADPH, which is required for GSH regeneration was also significantly reduced in Malme-3M.

As shown in

Figure 5 the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and de novo purine synthesis are differentially regulated by CBD in fibroblast vs Malme-3M cells. As a result of a likely increase in glycolytic activity in the Malme-3M cell line, glucose carbons are shunted away from the PPP to accommodate this increased demand for ATP. This results in an overall decrease in de novo purine synthesis as shown by a dramatic decrease in both 6-phosphogluconate (6-PG), the first metabolite of the PPP, and adenosine levels, a key precursor for nucleotide synthesis. The nucleotide salvage pathway can potentially recycle purine bases to maintain some level of de novo purine synthesis. During this process of recycling nucleotides, hypoxanthine is a key intermediate. We see both hypoxanthine and IMP, a product recycled from hypoxanthine, is significantly elevated in Malme-3M + CBD only, suggesting nucleotide salvage is activated. The first committed step of the PPP also produces NADPH which is essential for GSH regeneration. We see that in Malme-3M, this step seems to be reduced, resulting from less activity in the PPP and as a byproduct, less production of NADPH as shown in

Figure 3. Interestingly, while we also see an increase in IMP and hypoxanthine in the fibroblast cell line, we see an increase in adenosine as well which may suggest that in the fibroblast cell line, overall de novo purine synthesis might be upregulated because of CBD treatment, in contrast to the decrease of de novo purine synthesis we are seeing in the Malme cell line

.

4. Discussion

A detailed metabolic analysis of both normal human BJ fibroblasts and a transformed fibroblast cell line, Malme-3M, after treatment with CBD was performed. CBD exerted a differential effect in the Malme-3M cell line, particularly affecting central energy metabolites. Specifically, there was a reduction of TCA cycle metabolites in the Malme-3M cells, and a corresponding increase in glycolytic output in the form of lactic acid. Consistent with an inhibited TCA cycle, reductions in ATP levels were seen. A potential consequence of an elevated glycolytic pathway is the diversion of glucose carbons away from de novo purine synthesis for the continued production of ATP for cell survival. However, because of reduced purine synthesis, the nucleotide salvage pathway appears to be elevated, as noted with increase in both hypoxanthine and IMP, key biomarkers of nucleotide salvage, in CBD treated Malme-3M cells. A major consequence of reduced carbon flow through the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), a key precursor pathway for de novo purine synthesis, is the reduction of NADPH which is generated by the first committed step of the PPP. NADPH is critical for the recycling of oxidized glutathione during times of oxidative stress. Overall, in conjunction with a reduction of total glutathione levels, we suggest that this can further sensitize the cells to oxidative stress.

The reduction of total glutathione levels could be in part due to a reduction of de novo synthesis of glutathione as glutamate, a key glutathione precursor, could be re-directed to the TCA to compensate for the reduced TCA activity. A reduction in glutathione, in combination with reduced levels of NADPH, may result in an increased sensitivity to oxidative stress in the Malme-3M cells. Therefore, CBD treatment may result in synergistic effects when combined with other redox-inducing stress such as radiation therapy.

Interestingly, while the normal fibroblasts also exhibited changes in some of the same key metabolic pathways, namely the TCA cycle and increase in lactic acid production, however, there were key differences in the response by the BJ fibroblasts. One key difference in the response to CBD treatment was the overall increase in short and medium chain fatty acids in the non-tumorigenic BJ fibroblast cell line, while we saw either no change or a slight decrease in the Malme-3M cell line. This differential response could be observed because of the inhibited TCA cycle. The normal fibroblasts may switch to fatty acid oxidation to maintain cellular ATP levels. Indeed, there was no change in ATP levels in the fibroblast cell line, even in the presence of reduced citrate concentrations and a presumably reduced TCA cycle. Whereas we saw that the tumorigenic Malme-3M cells were unable to maintain cellular ATP levels in a similar way and instead attempted to maintain levels through an increase in glycolytic output as evidenced by a larger increase in lactic acid in the Malme-3M cell line.

This study focused primarily on metabolic consequences of CBD treatment in benign and transformed fibroblasts. Future studies are warranted to examine the underlying mechanism associated with these metabolic alterations. However, it is possible that calcium maintenance may be involved due to the mitochondria-related consequences of CBD treatment. CBD has previously been shown to increase intracellular calcium levels and reduce cell viability [

20,

21,

22]. These effects can be attributed to activation of the transmembrane ion channel TRPA1 by CBD, followed by activation of the mitochondrial outer membrane VDAC1 by increased calcium flux or direct interaction with CBD [

22,

23]. VDAC1 is an outer mitochondrial receptor that increases uptake of calcium into the mitochondria leading to and contributing to calcium overload and cell death. It is unclear why CBD would have differential effects on normal vs cancer cell lines; however, studies have shown alterations of cancer cell mitochondrial membrane composition [

24] which could leave cancer cells more susceptible to calcium dysregulation as a result of CBD treatment.

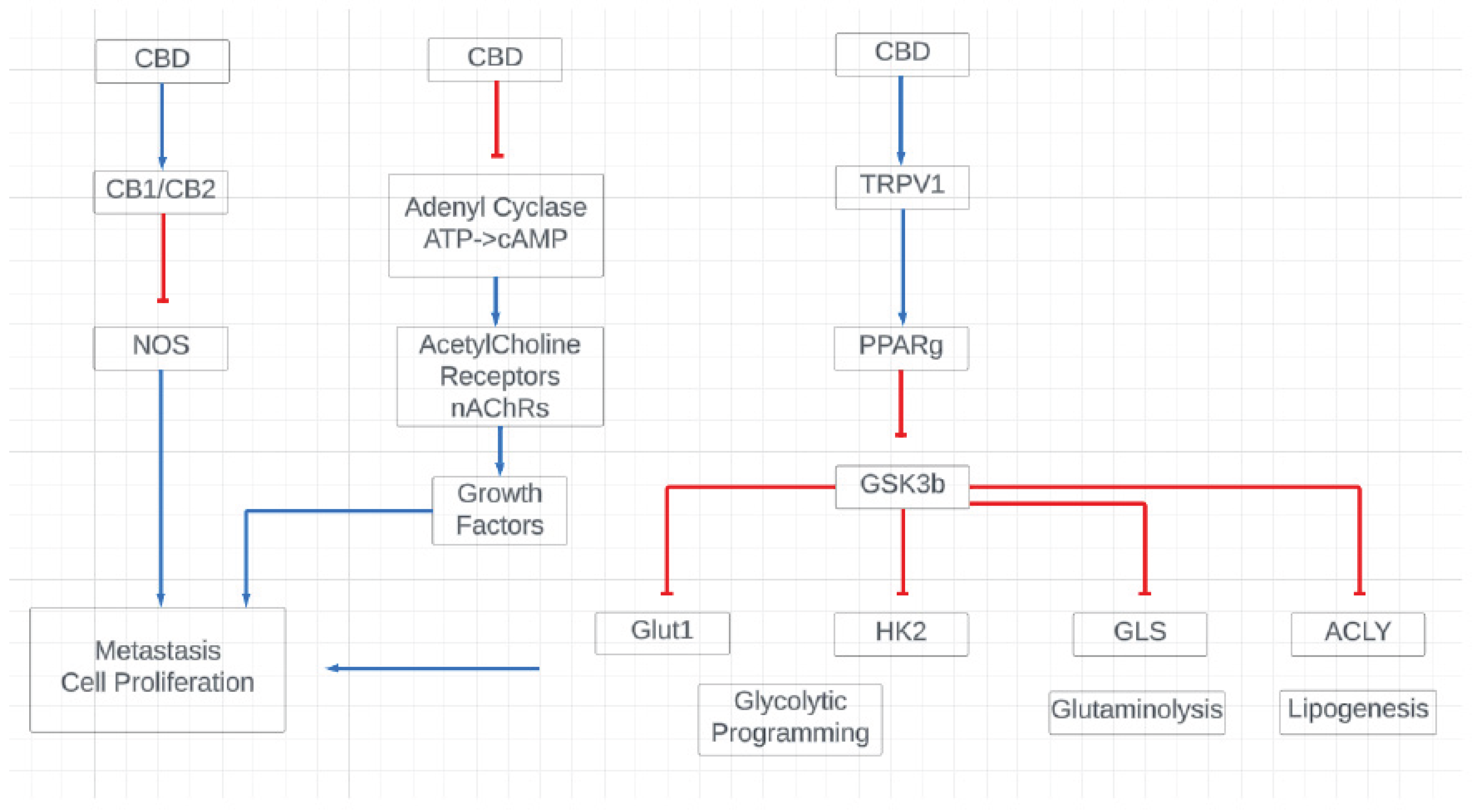

Due to the known effect CBD has on mitochondrial calcium homeostasis, we suggest that CBD exerts its effects through several potential signaling pathways, including through the CB1/CB2, VDAC1, and TRPV1 receptors which all in turn regulate various cellular processes from the regulation of glycolysis and glutaminolysis to the regulation of oxidative stress markers as shown in

Figure 6.

5. Conclusions

For the first time, an analysis of metabolomics of both normal and tumor derived cell lines after pre-treatment with CBD has been made. As a result of CBD treatment, there is reprogramming of key metabolic processes including the TCA cycle, redox maintenance, and fatty acid oxidation. While more studies are needed to fully elucidate the mechanistic effects of CBD treatment, there is a clear and differential cellular metabolic consequence of CBD treatment in malignant Malme-3M cells versus normal BJ fibroblasts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: LMS; Methodology: LMS, AMB YU; Analysis, review, edit: LMS, AMB, HG.

Funding

Human Metabolome Technologies, America.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- McAllister, S.D., et al., Pathways mediating the effects of cannabidiol on the reduction of breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2011. 129(1): p. 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M., et al., A pilot clinical study of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Br J Cancer, 2006. 95(2): p. 197-203. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.M., et al., Cannabinoid Receptor-1 suppresses M2 macrophage polarization in colorectal cancer by downregulating EGFR. Cell Death Discov, 2022. 8(1): p. 273. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.F., et al., Cannabinoids in Breast Cancer: Differential Susceptibility According to Subtype. Molecules, 2021. 27(1). [CrossRef]

- McAllister, S.D., et al., Cannabidiol as a novel inhibitor of Id-1 gene expression in aggressive breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther, 2007. 6(11): p. 2921-7. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.N., et al., Inhibition of ATM kinase upregulates levels of cell death induced by cannabidiol and gamma-irradiation in human glioblastoma cells. Oncotarget, 2019. 10(8): p. 825-846. [CrossRef]

- Massi, P., et al., Cannabidiol as potential anticancer drug. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2013. 75(2): p. 303-12. [CrossRef]

- Munson, A.E., et al., Antineoplastic activity of cannabinoids. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1975. 55(3): p. 597-602.

- Mao, Y., et al., Protective effects of cannabinoid receptor 2 on annulus fibrosus degeneration by upregulating autophagy via AKT-mTOR-p70S6K signal pathway. Biochem Pharmacol, 2025. 232: p. 116734. [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O., On the origin of cancer cells. Science, 1956. 123(3191): p. 309-14. [CrossRef]

- DeBerardinis, R.J., et al., Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(49): p. 19345-50. [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, T.N. and L.M. Shelton, Cancer as a metabolic disease. Nutr Metab (Lond), 2010. 7: p. 7. [CrossRef]

- Shelton, L.M., L.C. Huysentruyt, and T.N. Seyfried, Glutamine targeting inhibits systemic metastasis in the VM-M3 murine tumor model. Int J Cancer, 2010. 127(10): p. 2478-85. [CrossRef]

- Sooda, K., S.J. Allison, and F.A. Javid, Investigation of the cytotoxicity induced by cannabinoids on human ovarian carcinoma cells. Pharmacol Res Perspect, 2023. 11(6): p. e01152. [CrossRef]

- Jastrzab, A., A. Gegotek, and E. Skrzydlewska, Cannabidiol Regulates the Expression of Keratinocyte Proteins Involved in the Inflammation Process through Transcriptional Regulation. Cells, 2019. 8(8). [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J., W.W. Chen, and X. Zhang, Endocannabinoid system: Role in depression, reward and pain control (Review). Mol Med Rep, 2016. 14(4): p. 2899-903. [CrossRef]

- Pisanti, S., et al., Cannabidiol: State of the art and new challenges for therapeutic applications. Pharmacol Ther, 2017. 175: p. 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.B., The Case for the Entourage Effect and Conventional Breeding of Clinical Cannabis: No “Strain,” No Gain. Front Plant Sci, 2018. 9: p. 1969.

- Elsaid, S., S. Kloiber, and B. Le Foll, Effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in neuropsychiatric disorders: A review of pre-clinical and clinical findings. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 2019. 167: p. 25-75.

- Rimmerman, N., et al., Direct modulation of the outer mitochondrial membrane channel, voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) by cannabidiol: a novel mechanism for cannabinoid-induced cell death. Cell Death Dis, 2013. 4(12): p. e949. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.Z. and R.E. Duncan, Regulatory Effects of Cannabidiol on Mitochondrial Functions: A Review. Cells, 2021. 10(5). [CrossRef]

- de la Harpe, A., N. Beukes, and C.L. Frost, CBD activation of TRPV1 induces oxidative signaling and subsequent ER stress in breast cancer cell lines. Biotechnol Appl Biochem, 2022. 69(2): p. 420-430. [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, M., et al., Anandamide inhibits metabolism and physiological actions of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the striatum. Nat Neurosci, 2008. 11(2): p. 152-9. [CrossRef]

- Kiebish, M.A., et al., Brain mitochondrial lipid abnormalities in mice susceptible to spontaneous gliomas. Lipids, 2008. 43(10): p. 951-9. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overall view of key metabolic changes observed in the Malme-3M cell line relative to the control BJ Fibroblasts. As show in the table a number of metabolites involved in primary metabolism, to include choline regulation, glycolysis and the TCA were differentially regulated by CBD in the Malme cell line. Up regulated cutoff for TTEST was 1.2 fold or above, Down regulated cutoff was 0.8 or below.

Figure 1.

Overall view of key metabolic changes observed in the Malme-3M cell line relative to the control BJ Fibroblasts. As show in the table a number of metabolites involved in primary metabolism, to include choline regulation, glycolysis and the TCA were differentially regulated by CBD in the Malme cell line. Up regulated cutoff for TTEST was 1.2 fold or above, Down regulated cutoff was 0.8 or below.

Figure 2.

Primary metabolic response to CBD treatment. BJ Fibroblast and Malme-3M cell lines were treated with 10 and 16 um CBD which respectively represents the IC50 for each cell line. While the fibroblast cell line showed a significant decrease in the TCA cycle metabolite citrate, there was no corresponding increase in glycolytic activity as shown by no significant difference in ATP concentrations. However, with the marked reduction in citrate levels in the Malme cell line, there was a corresponding significant decrease in ATP. Glycolytic activity was correspondingly increased in the Malme cell line in a likely attempt to maintain ATP levels.

Figure 2.

Primary metabolic response to CBD treatment. BJ Fibroblast and Malme-3M cell lines were treated with 10 and 16 um CBD which respectively represents the IC50 for each cell line. While the fibroblast cell line showed a significant decrease in the TCA cycle metabolite citrate, there was no corresponding increase in glycolytic activity as shown by no significant difference in ATP concentrations. However, with the marked reduction in citrate levels in the Malme cell line, there was a corresponding significant decrease in ATP. Glycolytic activity was correspondingly increased in the Malme cell line in a likely attempt to maintain ATP levels.

Figure 3.

Fatty acid metabolism is elevated in fibroblasts cells as a result of CBD treatment. Short chain fatty acids are found to be elevated in the fibroblast cell line in response to CBD treatment with significant changes seen in octanoic, mevalonic, and undecanoic acid. In contrast, there is an overall slight decrease or no change in the Malme cell line, consistent with an inhibited TCA cycle.

Figure 3.

Fatty acid metabolism is elevated in fibroblasts cells as a result of CBD treatment. Short chain fatty acids are found to be elevated in the fibroblast cell line in response to CBD treatment with significant changes seen in octanoic, mevalonic, and undecanoic acid. In contrast, there is an overall slight decrease or no change in the Malme cell line, consistent with an inhibited TCA cycle.

Figure 4.

CBD results in potential oxidative stress or greater susceptibility to oxidative stress in tumor cells lines only. Glutamate (GLU) was significantly reduced in the Malme-3M cell line, resulting in a significant reduction in both GSH and GSSG, likely affecting de novo glutathione synthesis. NADPH, which is required for GSH regeneration was also significantly reduced in Malme-3M only.

Figure 4.

CBD results in potential oxidative stress or greater susceptibility to oxidative stress in tumor cells lines only. Glutamate (GLU) was significantly reduced in the Malme-3M cell line, resulting in a significant reduction in both GSH and GSSG, likely affecting de novo glutathione synthesis. NADPH, which is required for GSH regeneration was also significantly reduced in Malme-3M only.

Figure 5.

The pentose phosphate pathway and de novo purine synthesis is differentially regulated by CBD in fibroblast vs Malme-3M cells. As a result of a likely increase in glycolytic activity in the Malme-3M cell line, glucose carbons are shunted away from the PPP in the Malme-3M cell line to accommodate this increased demand for ATP as shown by a significant decrease in 6PG, the first metabolite of the PPP. This results in an overall decrease in de novo purine synthesis as shown in a dramatic decrease in adenosine levels. The nucleotide salvage pathway can potentially recycle purine bases to maintain some level of de novo purine synthesis. We see hypoxanthine and IMP, a product recycled from hypoxanthine, is drastically elevated in Malme-3M + CBD, suggesting nucleotide salvage is activated in the Malme-3M cell line. In contrast, we see elevations of all of the purine metabolites in the normal BJ fibroblast cell line suggesting de novo purine synthesis may be elevated slightly in the normal BJ fibroblast cell line.

Figure 5.

The pentose phosphate pathway and de novo purine synthesis is differentially regulated by CBD in fibroblast vs Malme-3M cells. As a result of a likely increase in glycolytic activity in the Malme-3M cell line, glucose carbons are shunted away from the PPP in the Malme-3M cell line to accommodate this increased demand for ATP as shown by a significant decrease in 6PG, the first metabolite of the PPP. This results in an overall decrease in de novo purine synthesis as shown in a dramatic decrease in adenosine levels. The nucleotide salvage pathway can potentially recycle purine bases to maintain some level of de novo purine synthesis. We see hypoxanthine and IMP, a product recycled from hypoxanthine, is drastically elevated in Malme-3M + CBD, suggesting nucleotide salvage is activated in the Malme-3M cell line. In contrast, we see elevations of all of the purine metabolites in the normal BJ fibroblast cell line suggesting de novo purine synthesis may be elevated slightly in the normal BJ fibroblast cell line.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanistic action of CBD in cancerous Malme-3M cells. We suggest that CBD exerts its effects in part due to it’s known role in regulating CB1/CB2, cAMP, and TRPV1 receptors. These in turn are key regulators of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and lipogenesis, all key pathways that were found to be differentially regulated by CBD treatment.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanistic action of CBD in cancerous Malme-3M cells. We suggest that CBD exerts its effects in part due to it’s known role in regulating CB1/CB2, cAMP, and TRPV1 receptors. These in turn are key regulators of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and lipogenesis, all key pathways that were found to be differentially regulated by CBD treatment.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).