1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by restricted interests, repetitive behaviors, and especially communication disorders. The prevalence rate of ASD has a marked gender difference, that is, the male-to-female ratio varying from 2:1 to 15:1 [

1]. The mechanism of the remarkable gender bias of ASD is thought to be due to testosterone (TSTN) level during the fetal brain development [

2,

3]. TSTN, one of the main male hormones, is reported that high levels of maternally derived TSTN to higher autistic tendency. In the second pregnancy trimester, TSTN level increases sharply in the womb, which is important for boy’s brain development. It is called “TSTN shower” [

4]. Thus, extremely high levels of TSTN during brain development might lead to brain malformation and impair social behavior. Molecular understanding of the roles of TSTN in the ASD onset had not been archived, however, we have previously reported that TSTN directly binds to Neurexin (Nrxn) and interrupts NRXN and Neuroligin (Nlgn) interaction

in vitro [

5].

Nrxn and Nlgn are both single transmembrane proteins and localized at pre- or post-synapses, respectively. Nrxn and Nlgn, also known as “synaptic organizers”, play essential roles in synapse differentiation and maturation [

6,

7,

8], while these functions require the trans-synaptic interaction between Nrxn and Nlgn [

9,

10,

11]. Moreover, Nrxn and Nlgn gain attention as ASD-related genes because familial ASD mutations or copy number variations are reported on both Nrxn and Nlgn [

12,

13,

14,

15]. From these studies, it is thought that normal expressions of Nrxn and Nlgn at synaptic clefts are necessary for social function. Furthermore, the Nrxn-Nlgn trans-synaptic interaction is also considered a crucial function in regulation of social behavior [

16].

Therefore, we hypothesized that heavily concentrated TSTN during the brain development interrupts Nrxn-Nlgn trans-synaptic interaction, leading to abnormal synaptic formation and impaired social behavior. It can explain the molecular mechanisms of TSTN on ASD onset and the possibility of sporadic ASD development even though without Nrxn or Nlgn mutations. In this study, we injected TSTN into pregnant mice and assayed their neonate brain. We found that the TSTN injection decreased Nrxn-Nlgn binding . We also investigated the social preference behavior. Interestingly, male mice showed social novelty impairment, whereas female mice showed social novelty and sociability impairment by TSTN injection. On the other hand, the performances of novel object recognition task and Y-maze task were not changed. Thus, from this study, it is revealed that the molecular mechanism of TSTN of ASD onset and the missing link of sporadic ASD-causing mechanisms by Nrxn, Nlgn and TSTN.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the regulations and guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals at Saitama Medical University and were approved by the institutional review committees. C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory Japan, Yokohama, Japan) were housed and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle and allowed ad libitum access to food and water. Pregnant mice (13-15 days) were injected with 12.5mg/kg Testosterone solution (TSTN) or Corn oil subcutaneously. The brain tissues from neonates which were born from the injected mice, were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) assay. On the other hand, neonates born from the injected mice were raised to 7-12 weeks old, and subjected to behavioral experiments.

2.2. Antibodies and Chemicals

Anti-NRXN3 (HPA002727) was purchased from Atlas Antibodies (Bromma, Sweden). Anti-all Nlgn (1/2/3/4) antibody (#129213) was purchased from Synaptic Systems (Goettingen, Germany). TSTN solution was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Brain Sample Preparation and co-IP with Nlgn

Neonate C57BL/6J were anesthetized with sevoflurane, and were sacrificed. The isolated brain tissues were divided into hippocampi and cortices, and frozen at -80℃ until use. The hippocampi were homogenized with 500μl RIPA Buffer (50mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH7.6), 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing 1% Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Nacalai Tesque INC., Kyoto, Japan) and cOmplete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Merck, NJ, USA). After holding on ice for 10min, hippocampus homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20min at 4℃. The supernatants were immunoprecipitated at 4℃ overnight with anti-neuroligin 1/2/3/4 antibody, which were incubated for 1hr with Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The magnetic beads were precipitated by a magnetic stand followed by 3 times RIPA Buffer wash. Protein samples were denatured with 15μl Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) and boiled for 3min.

2.4. Western Blotting

Protein samples were separated on 5-10% precast gels (Nacalai Tesque) by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk (MEGMILK SNOW BRAND Co., Ltd., Sapporo, Japan) for 1h at room temperature, and incubated overnight at 4℃ with the primary antibodies. The membranes were washed, and probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse/ -rabbit secondary antibody. Signals were detected using Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nacalai Tesque) or ImmunoStar LD (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) by ChemiDoc MP (Bio-rad).

2.5. Behavioral Test

2.5.1. Three-Chamber Social Test

The three-chamber arena was a box (61 cm x 40 cm x 19 cm) made of white acrylic board, and was divided into three equal compartments, where mice were allowed to freely move between the compartments through the doors on dividing walls.

The subject mouse was habituated to the three-chamber arena for 5min without any objects or animals. After habituation, the subject mouse was returned to their breeding cage. A stimulus mouse was placed under a wire cage (animal side) in one side of the chamber, and a similar wire cage without a mouse was placed in the other side (object side). The subject mouse was placed into the middle chamber in the beginning of the test and freely explored the three-chamber arena for 5min. To quantify the sociability, the sniffing time at each wire cage was measured.

After the sociability session, the subject mouse was returned to their breeding cage again. A novel mouse was put into the empty wire cage on the object side (Novel animal side), while the already known mouse stays in the animal side (familiar animal side). The subject mouse was placed into the middle chamber and freely explored for 5min. To quantify the social novelty, the sniffing time at each wire cage was measured.

2.5.2. Novel Object Recognition Test

The subject mouse was habituated to the three-chamber arena for 5min without any objects. After habituation, the subject mouse was returned to their breeding cage. The same objects were placed in both sides (Object A), and the subject mouse was placed into the middle chamber, and freely explored for 5min. After the same object session, the subject mouse was returned to their breeding cage again. Object A of the one side was replaced with a novel object (Object B). The subject mouse was placed into the middle chamber and freely explored for 5min. To quantify the novel object recognition, the sniffing time at Object A (Familiar) and Object B (Novel) was measured.

2.5.3. Y-Maze Test

Y-maze test was performed essentially as described previously (Yagishita et al., 2017). The Y maze apparatus (Hazai-ya, Tokyo, Japan) was a 3-arm (A, B, or C) maze with equal angles between all arms (8 cm width) and a bottom with 40 cm (length) and 15 cm height. Mice were tested individually by placing them in an arm of the maze, with allowing them to move freely throughout the 3 different arms for 10 min. The sequence and entries into each arm were recorded.

An accuracy rate was calculated as (the number of ‘successful’ alternations divided by the number of the total arm entries minus 2) × 100. The ‘successful’ alternation was defined as consecutive arm entries into the 3 different arms, such as, ABC, ACB, BCA, BAC, CAB, and CBA.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using R program (R core Team 2019). Student’s t-test (

Figure 1) or paired t-test (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) were performed.

3. Results

3.1. Nrxn and Nlgn Binding is Interrupted by TSTN Injection

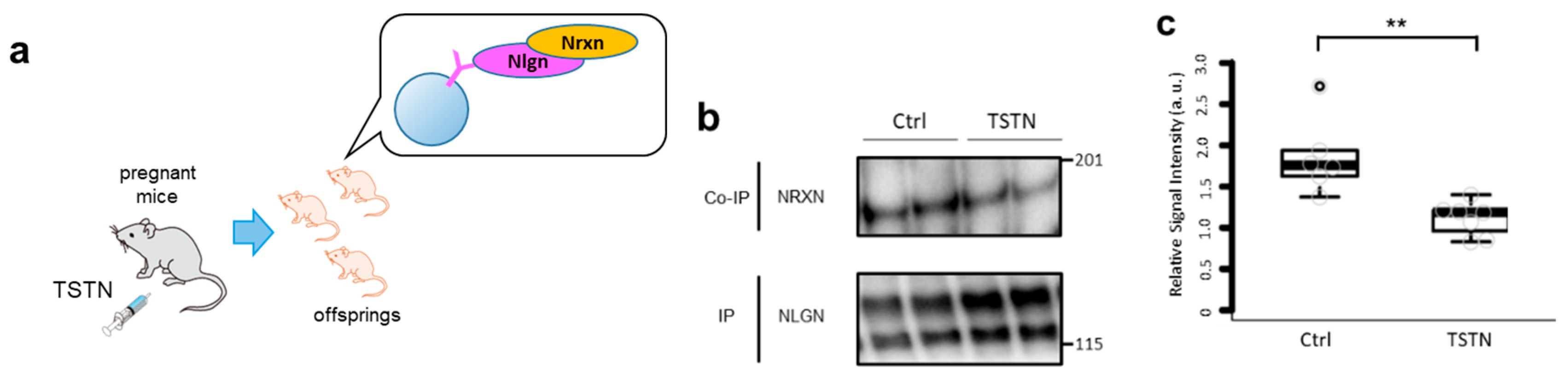

We injected TSTN or vehicle to pregnant mice to mimic the TSTN level elevation in the womb (

Figure 1a). We analyzed the binding intensities between Nrxn and Nlgn from TSTN-injected neonate brains by co-IP assay (

Figure 1b). According to the co-IP results, Nrxn-Nlgn bindings were reduced to ~75% by maternal TSTN injection (

Figure 1c).

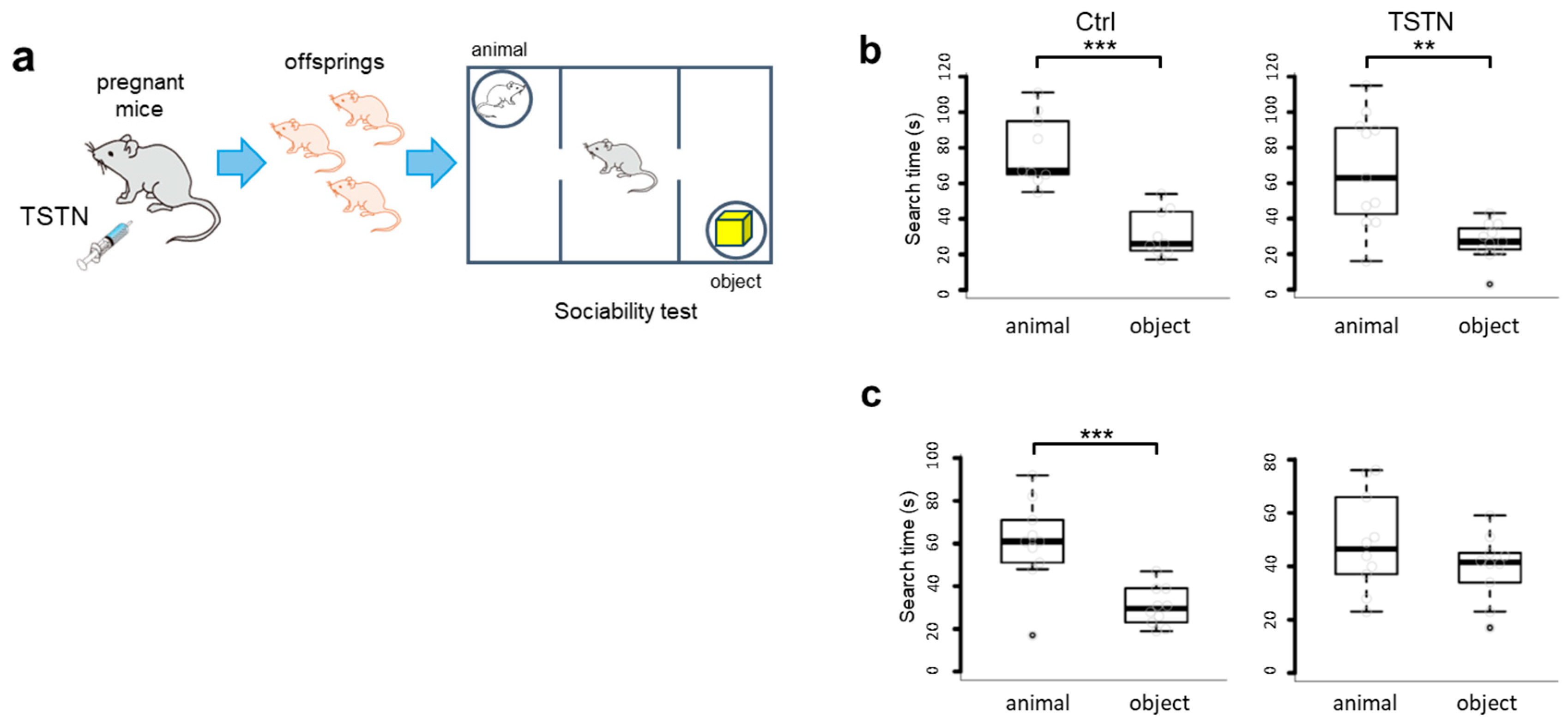

3.2. Sociability of Female Offsprings Is Impaired by TSTN Injection

We raised the neonates to 7-12 weeks old, and subjected to sociability tests (

Figure 2a.) The offsprings born from the vehicle-injected mother (Ctrl) and male offsprings born from the TSTN-injected mother (TSTN-m) significantly spent more time to search for the animal side than the object side (

Figure 2b). Noteworthy, there were no difference in animal/object searching time from TSTN-m female offsprings (

Figure 2c). Therefore, high levels of TSTN during the brain development period impaired sociability of female offsprings.

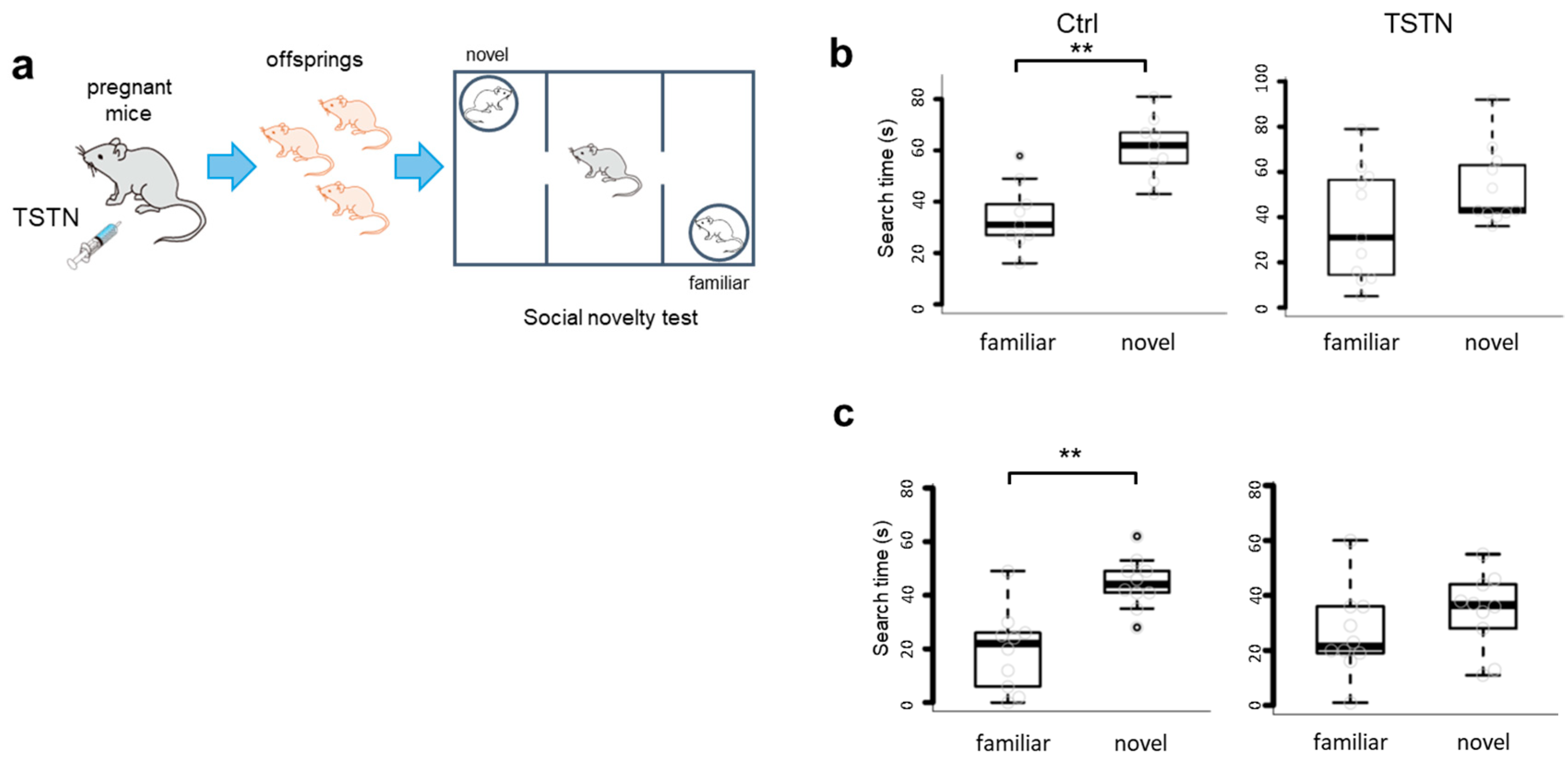

3.3. Social Novelty Is Impaired by TSTN Injection in both Male and Female Offsprings

Next, we performed social novelty tests (

Figure 3a). Ctrl offsprings exhibited significant differences between the novel animal side and the familiar animal side. They searched for the novel animal side longer than the familiar animal side. On the other hand, both male and female TSTN-m offsprings exhibited little differences between the novel animal side and the familiar animal side (

Figure 3b,c). Thus, TSTN exposure during the brain development period impaired social novelty.

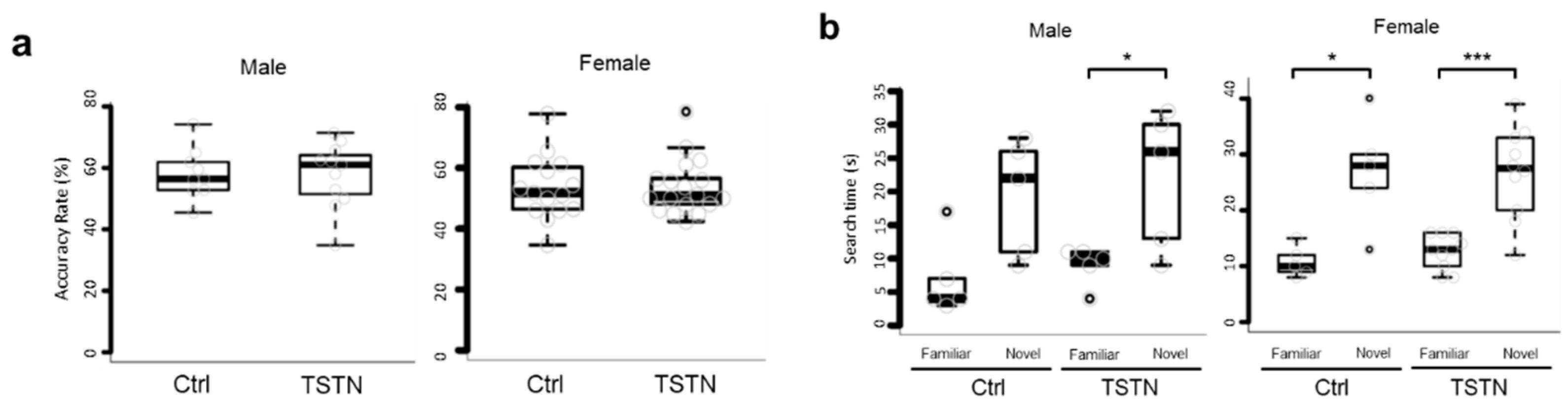

3.4. TSTN Offsprings Does Not Affect Working Memory

To confirm whether the ability impairments of TSTN offsprings were confined to sociality or not, we performed Y-maze test, and novel object recognition test. According to Y-maze test results, the accuracy rate was consistent across Ctrl and TSTN-m regardless of the sex (

Figure 4a). Also, in novel object recognition test, the tendency to search novel object longer than familiar object was consistent regardless of the treatment or the sex (

Figure 4b). These results indicated that TSTN exposure did not affect working memory or novel object recognition memory.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interruption of Nrxn-Nlgn Binding by TSTN Injection

Previously, we reported that, in cultured cells, TSTN interrupts Nrxn-Nlgn binding in a concentration-dependent manner [

5], suggesting that 100 nM TSTN is sufficient to inhibit Nrxn-Nlgn binding

in vitro. In the present study, we revealed that Nrxn-Nlgn binding was also interrupted by recreating the high levels of TSTN in fetus brain. Takekura et al. reported that serum TSTN reached the concentration of 100 nM by 20mg/kg intramuscular TSTN injection [

17]. Therefore, also in this study, TSTN was inferred to reach a concentration sufficient to affect Nrxn-Nlgn binding.

It is a fact that brain masculinization of rodents is different from human brain masculinization. The sex difference in the male mouse brain is under the influence of estrogens derived from the neural aromatization of TSTN [

18,

19,

20]. However, we focused on the nongenomic aspect of TSTN in this study, so it wouldn’t matter if the main sex-hormone effect of mouse brain development has come from estrogens.

4.2. Female Offsprings Have More Impact by TSTN Injection

From the results of sociability test, sociability of male offsprings were not different between Ctrl and TSTN-m. On the other hand, TSTN impaired sociability of female offsprings (

Figure 2). In the early development period, the plasma TSTN concentration was about 2 nM in neonatal male mice, while that was under 0.5n M in neonatal female mice [

21,

22,

23]. Then, female offsprings were more strongly influenced by TSTN injection because the gap between native TSTN and exogenous TSTN administration was wider than male offsprings. Thus, the impairment in social ability by TSTN injection was also stronger in female offsprings, and they had more severe symptoms of ASD.

4.3. High Level of TSTN in Utero Only Impairs Social Ability of Offsprings

Liu et al., reported that sevoflurane exposure only impaired social novelty but not sociability [

24]. This result indicated that social novelty was more susceptible to external stimuli than sociability. Our results also showed that social novelty was impaired not only in female offsprings, but also in male offsprings by TSTN injection (

Figure 3). Consequently, maternal TSTN injection is a comparatively strong stimulus for social ability impairment.

Our study also showed that TSTN injection did not impair the working memory and novel object recognition memory (

Figure 4). Thus, the social novelty impairments of offsprings were not due to the impairment to memorize which side was the familiar animal side. It was a particularly important characteristic in ASD symptoms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Y-K. and S.Y.; methodology, N.Y-K. and S.Y.; validation, N.Y-K. and S.Y.; formal analysis, N.Y-K.; investigation, N.Y-K.; data curation, N.Y-K. and S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Y-K.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.; visualization, N.Y-K.; supervision, S.Y..; project administration, N.Y-K.; funding acquisition, N.Y-K. and S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (23K06801 and 22K07333). The APC was funded by 22K07333.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saitama Medical University. (protocol code 4229 and date of approval 14th March 2025).

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at Saitama Medical University. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author N.Y-K. on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Mr. Kensuke Iwasa and Dr. Shinji Yamamoto (Saitama Medical University), Mrs. Takako Kuwahara for laboratory maintenance; Ms. Ayaka Mitobe (Saitama Medical University) for technical supports. We also thank to staff of Division of Analytical Science (Biomedical Research Center, Saitama Medical University) for their continual supports.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorder |

| TSTN |

Testosterone |

| Nrxn |

Neurexin |

| Nlgn |

Neuroligin |

| IP |

Immunoprecipitation |

References

- S.L. Ferri; T. Abel; E.S. Brodkin. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: a review. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep. 2018, 20, p. 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Baron-Cohen; B. Auyeung; B. Nørgaard-Pedersen; D. M. Hougaard; M. W. Abdallah; L. Melgaard; A. S. Cohen; B. Chakrabarti; L. Ruta; M. V. Lombardo. Elevated fetal steroidogenic activity in autism. Mol. Psychiatr. 2015, 20, pp. 369-376. [CrossRef]

- X.J. Xu; H.F. Zhang; X.J. Shou; J. Li; W.L. Jing; Y. Zhou; Y. Qian; S.P. Han; R. Zhang; J.S. Han. Prenatal hyperandrogenic environment induced autistic-like behavior in rat offspring. Physiol Behav. 2015, 138, pp. 13-20. [CrossRef]

- A. Collignon; L. Dion-Albert; C. Ménard; V. Coelho-Santos. Sex, hormones and cerebrovascular function: from development to disorder. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2024, 21, Article No. 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Yagishita-Kyo; Y. Ikari; T. Uekita; A. Shinohara; C. Koshimoto; K. Yoshikawa; K. Maruyama; S. Yagishita. Testosterone interrupts binding of Neurexin and Neuroligin that are expressed in a highly socialized rodent, Octodon degus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021, 551, pp. 54-62. [CrossRef]

- E.R. Graf; X. Zhang; S.X. Jin; M.W. Linhoff; A.M. Craig. Neurexins induce differentiation of GABA and glutamate postsynaptic specializations via neuroligins. Cell. 2004, 119, pp. 1013-1026. [CrossRef]

- O. Prange; T.P. Wong; K. Gerrow; Y.T. Wang; A. El-Husseini. A balance between excitatory and inhibitory synapses is controlled by PSD-95 and neuroligin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101, pp. 13915-13920. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. Kang; X. Zhang; F. Dobie; H. Wu; A.M. Craig. Induction of GABAergic postsynaptic differentiation by alpha-neurexins. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283, pp. 2323-2334. [CrossRef]

- J. Ko; C. Zhang; D. Araç; A.A. Boucard; A.T. Brunger; T.C. Südhof. Neuroligin-1 performs neurexin-dependent and neurexin-independent functions in synapse validation. EMBO J. 2009, 28, pp. 3244-3255. [CrossRef]

- O. Gokce; T.C. Südhof. Membrane-tethered monomeric neurexin LNS-domain triggers synapse formation. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, pp. 14617-14628. [CrossRef]

- T. Tsetsenis; A.A. Boucard; D. Araç; A.T. Brunger; T.C. Südhof. Direct visualization of trans-synaptic neurexin-neuroligin interactions during synapse formation. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, pp. 15083-15096. [CrossRef]

- S. Jamain; H. Quach; C. Betancur; M. Råstam; C. Colineaux; I.C. Gillberg; H. Soderstrom; B. Giros; M. Leboyer; C. Gillberg; T. Bourgeron. Paris Autism Research International Sibpair Study. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet. 2003, 34, pp. 27-29. [CrossRef]

- F. Laumonnier; F. Bonnet-Brilhault; M. Gomot; R. Blanc; A. David; M.P. Moizard; M. Raynaud; N. Ronce; E. Lemonnier; P. Calvas; B. Laudier; J. Chelly; J.P. Fryns; H.H. Ropers; B.C. Hamel; C. Andres; C. Barthélémy; C. Moraine; S. Briault. X-linked mental retardation and autism are associated with a mutation in the NLGN4 gene, a member of the neuroligin family. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74, pp. 552-557. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Julie; J.S. Tabrez; H. Peng; Y. Daisaku; F.H. Fadi; C. Nathalie; L. Mathieu; S. Dan; N. Anne; G.L. Ronald; F. Ferid; J. Ridha; K. Marie-Odile; E.D. Lynn; M. Laurent; F. Eric; L.M. Jacques; D. Pierre; C. Salvatore; M.C. Ann; A.R. Guy. Truncating mutations in NRXN2 and NRXN1 in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Hum. Genet. 2011, 130, pp. 563-573.

- S.J. Sanders; A.G. Ercan-Sencicek; V. Hus; R. Luo; M.T. Murtha; D. Moreno-De-Luca; S.H. Chu; M.P. Moreau; A.R. Gupta; S.A. Thomson; C.E. Mason; K. Bilguvar; P.B. Celestino-Soper; M. Choi; E.L. Crawford; L. Davis; N.R. Wright; R.M. Dhodapkar; M. DiCola; N.M. DiLullo; T.V. Fernandez; V. Fielding-Singh; D.O. Fishman; S. Frahm; R. Garagaloyan; G.S. Goh; S. Kammela; L. Klei; J.K. Lowe; S.C. Lund; A.D. McGrew; K.A. Meyer; W.J. Moffat; J.D. Murdoch; B.J. O'Roak; G.T. Ober; R.S. Pottenger; M.J. Raubeson; Y. Song; Q. Wang; B.L. Yaspan; T.W. Yu; I.R. Yurkiewicz; A.L. Beaudet; R.M. Cantor; M. Curland; D.E. Grice; M. Günel; R.P. Lifton; S.M. Mane; D.M. Martin; C.A. Shaw; M. Sheldon; J.A. Tischfield; C.A. Walsh; E.M. Morrow; D.H. Ledbetter; E. Fombonne; C. Lord; C.L. Martin; A.I. Brooks; J.S. Sutcliffe; E.H. Cook Jr; D. Geschwind; K. Roeder; B. Devlin; M.W. State. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011, 70, pp. 863-885. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S.A. Connor; I. Ammendrup-Johnsen; A.W. Chan; Y. Kishimoto; C. Murayama; N. Kurihara; A. Tada; Y. Ge; H. Lu; R. Yan; J.M. LeDue; H. Matsumoto; H. Kiyonari; Y. Kirino; F. Matsuzaki; T. Suzuki; T.H. Murphy; Y.T. Wang; T. Yamamoto; A.M. Craig. Altered Cortical Dynamics and Cognitive Function upon Haploinsufficiency of the Autism-Linked Excitatory Synaptic Suppressor MDGA2. Neuron. 2016, 91, pp. 1052-1068. [CrossRef]

- H. Takekura; R. Watanabe; N. Kasuga; T. Yoshioka. Influences of exogenous testosterone administration for the weight and functional profiles in exercise trained rat skeletal muscle. Jpn J. Phys. Educ. Health Sport Sci. 1991, 36, pp. 337-348. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Baum. Differentiation of coital behavior in mammals: a comparative analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1979, 3, pp. 265-284. [CrossRef]

- N.J. MacLusky; F. Naftolin. Sexual differentiation of the central nervous system. Science. 1981, 211, pp. 1294-1303.

- J. Bakker; T. Brand; J. van Ophemert; A.K. Slob. Hormonal regulation of adult partner preference behavior in neonatally ATD-treated male rats. Behav. Neurosci. 1993, 107, pp. 480-487.

- C. Jean-Faucher; M. Berger; M. de Turckheim; G. Veyssiere; C. Jean. Developmental patterns of plasma and testicular testosterone in mice from birth to adulthood. Acta Endocrinologica. 1978, 89, pp. 780-788. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S.J. Elliot; M. Berho; K. Korach; S. Doublier; E. Lupia; G.E. Striker; M. Karl. Gender-specific effects of endogenous testosterone: Female α-estrogen receptor-deficient C57Bl/6J mice develop glomerulosclerosis. Kidney International. 2007, 72, pp. 464-472. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Dela Cruz; H.M. Kinnear; P.H. Hashim; A. Wandoff; L. Nimmagadda; F.L. Chang; V. Padmanabhan; A. Shikanov; M.B. Moravek. A mouse model mimicking gender-affirming treatment with pubertal suppression followed by testosterone in transmasculine youth. Hum Reprod. 2023, 38, pp. 256-265. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu; X. Meng; Y. Li; S. Chen; Y. Ji; S. Song; F. Ji; X. Jin. Neonatal exposure to sevoflurane impairs preference for social novelty in C57BL/6 female mice at early-adulthood. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022, 593, pp. 129-136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).