Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Flexible Transparent Conductive Films

2.1. Transparency and Conductivity

2.2. Flexibility and Stability

3. Preparation Methods of AgNW-based Transparent Conductive Films

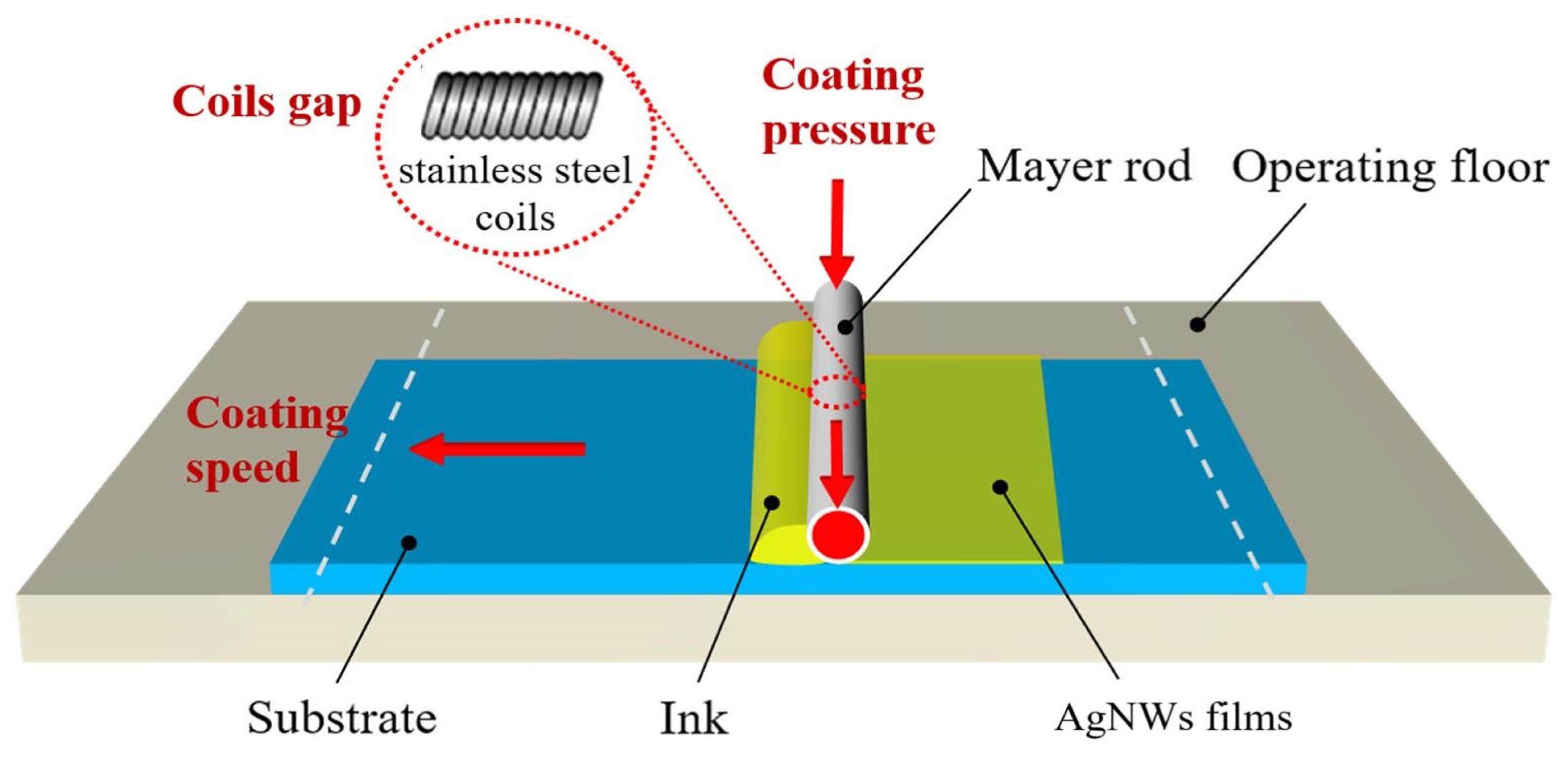

3.1. Meyer Rod Coating Method

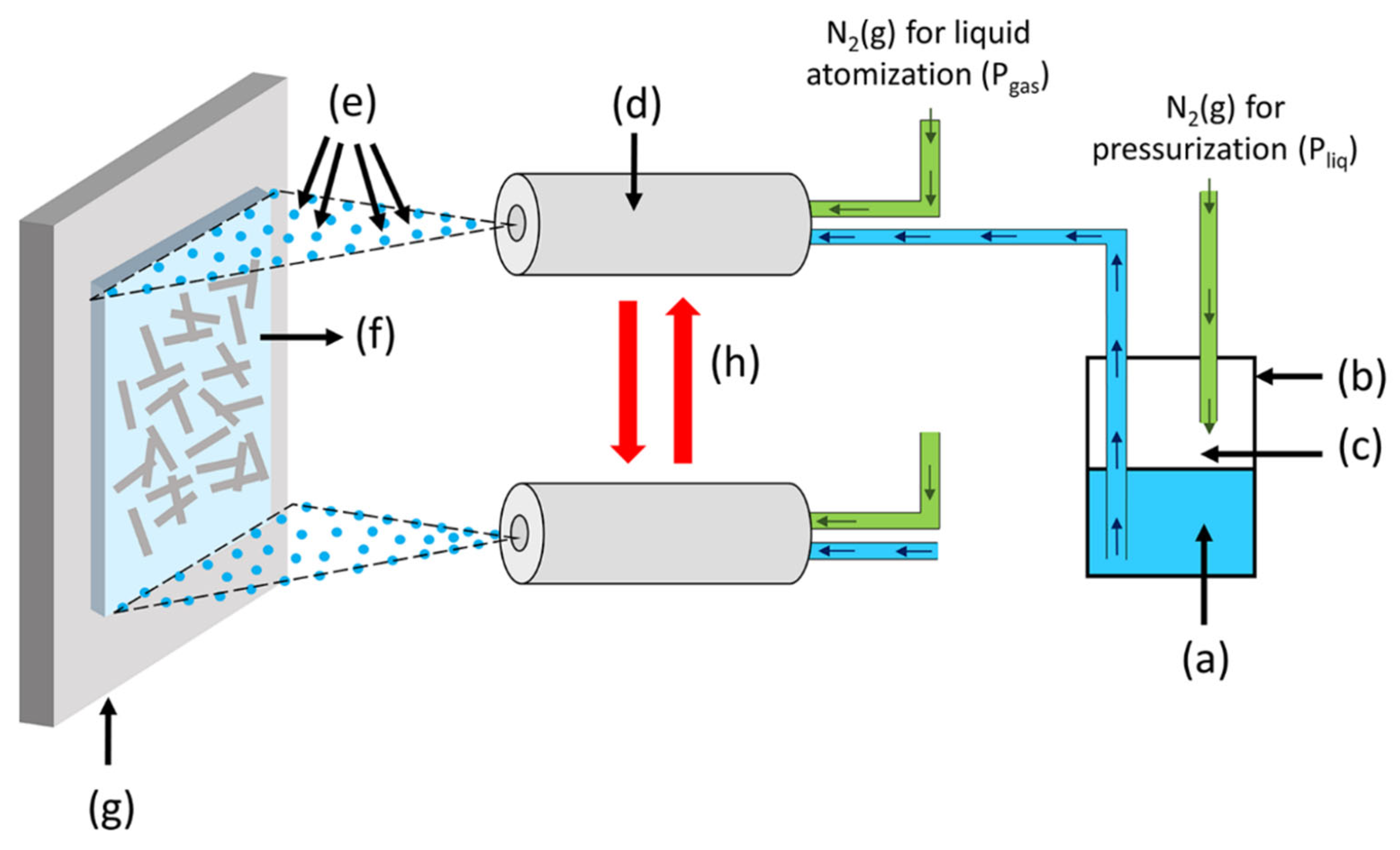

3.2. Spraying Method

3.3. Spin Coating Method

3.4. Silk-screen Printing

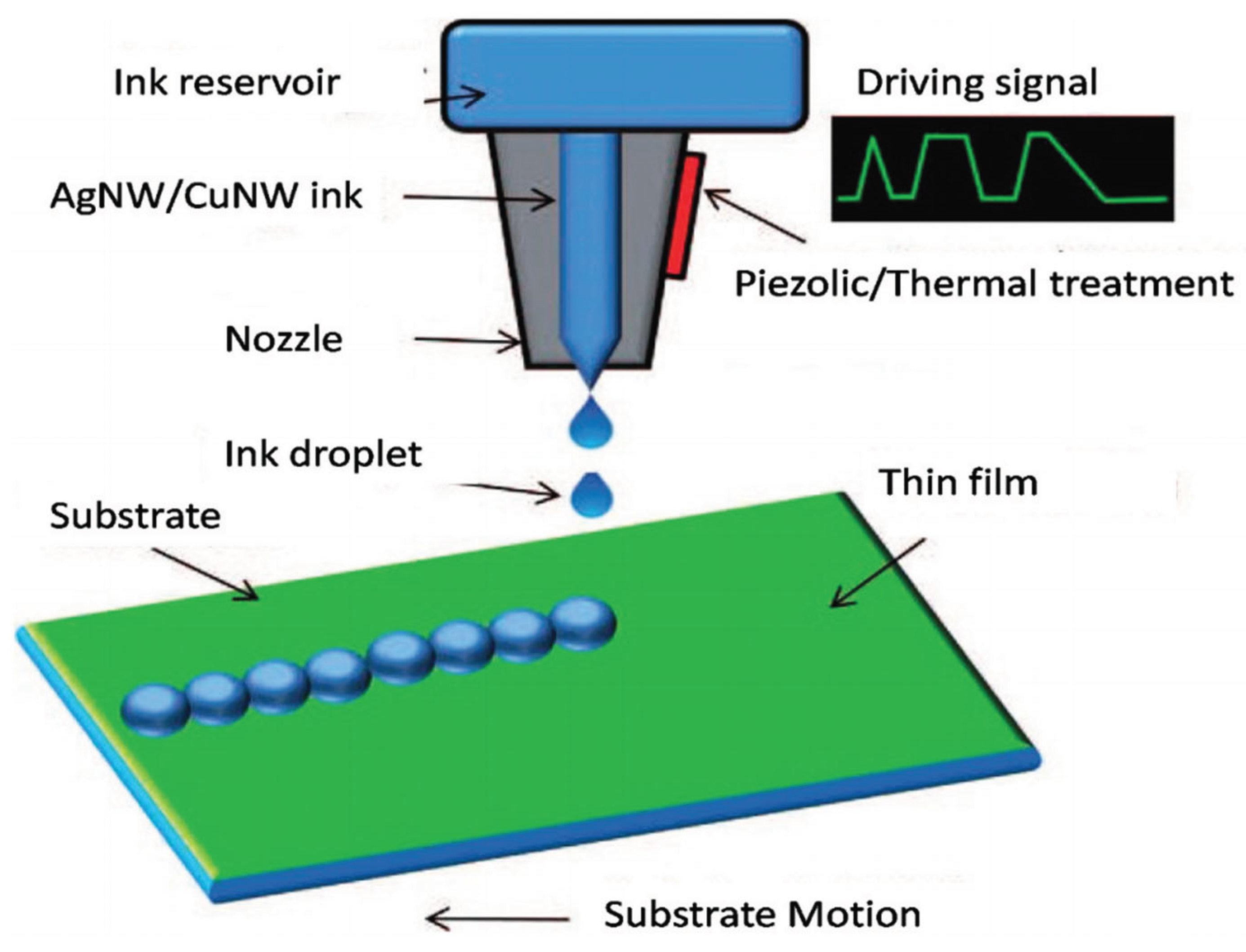

3.5. Inkjet Printing Method

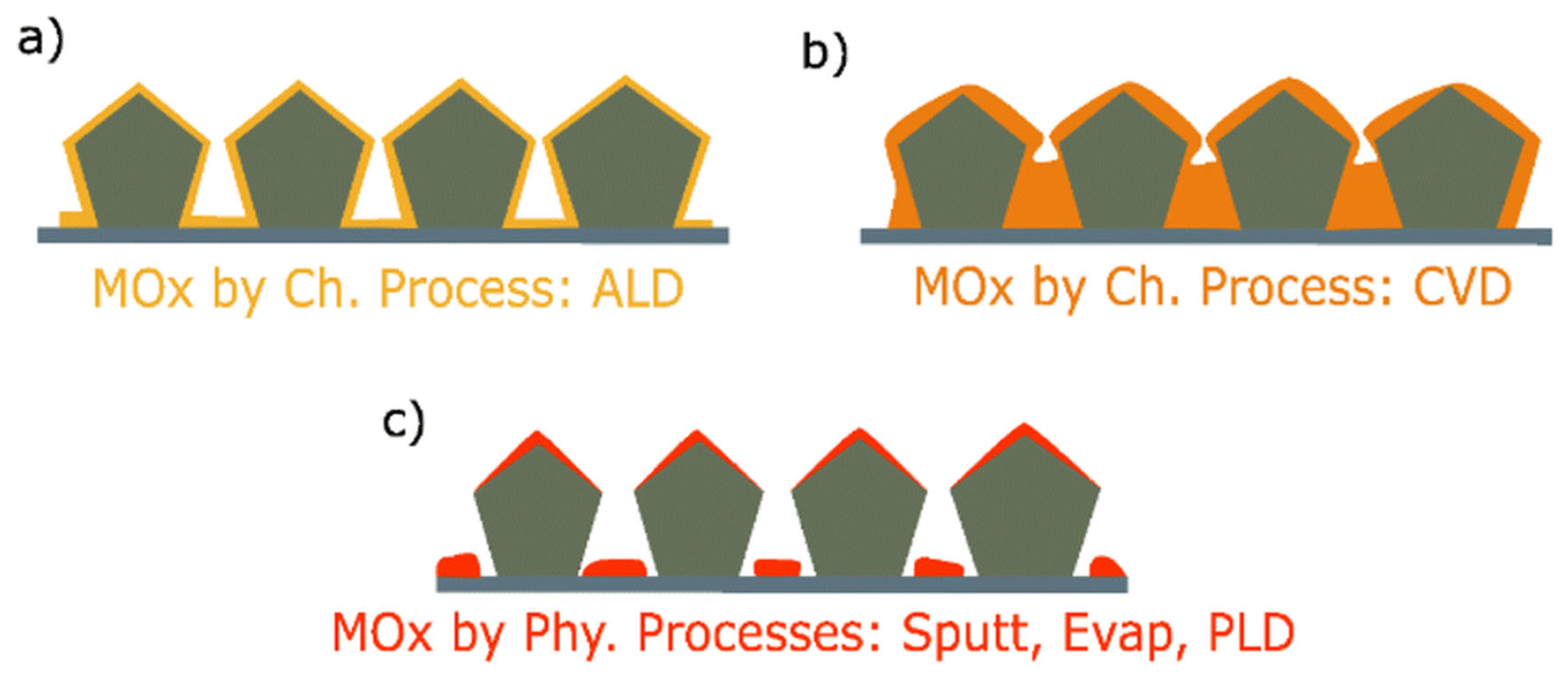

4. Methods to AgNW Networks Coated with Metal Oxides

4.1. Physical Vapor Deposition Methods

4.1.1. Sputtering Deposition

4.1.2. Pulsed layer deposition (PLD)

4.2. Chemical Deposition Methods

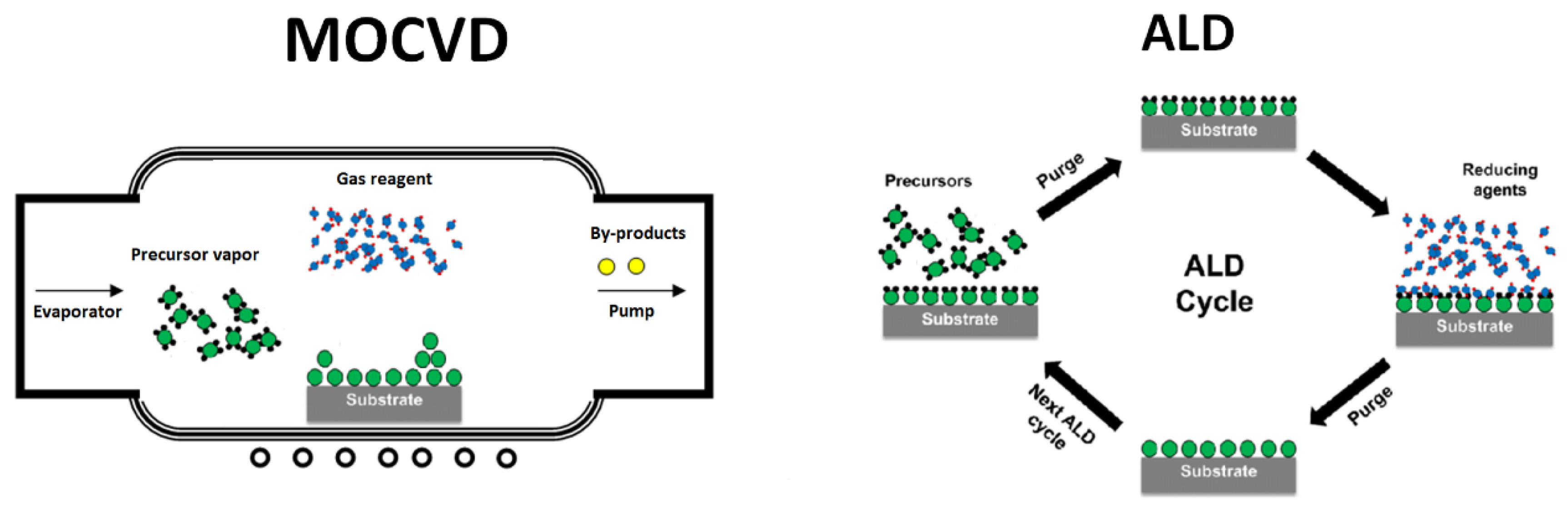

4.2.1. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)

4.2.2. Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD)

4.2.3. Solution Methods

4.3. Hybrid Approaches

5. Application of AgNW-TCFs

5.1. Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs)

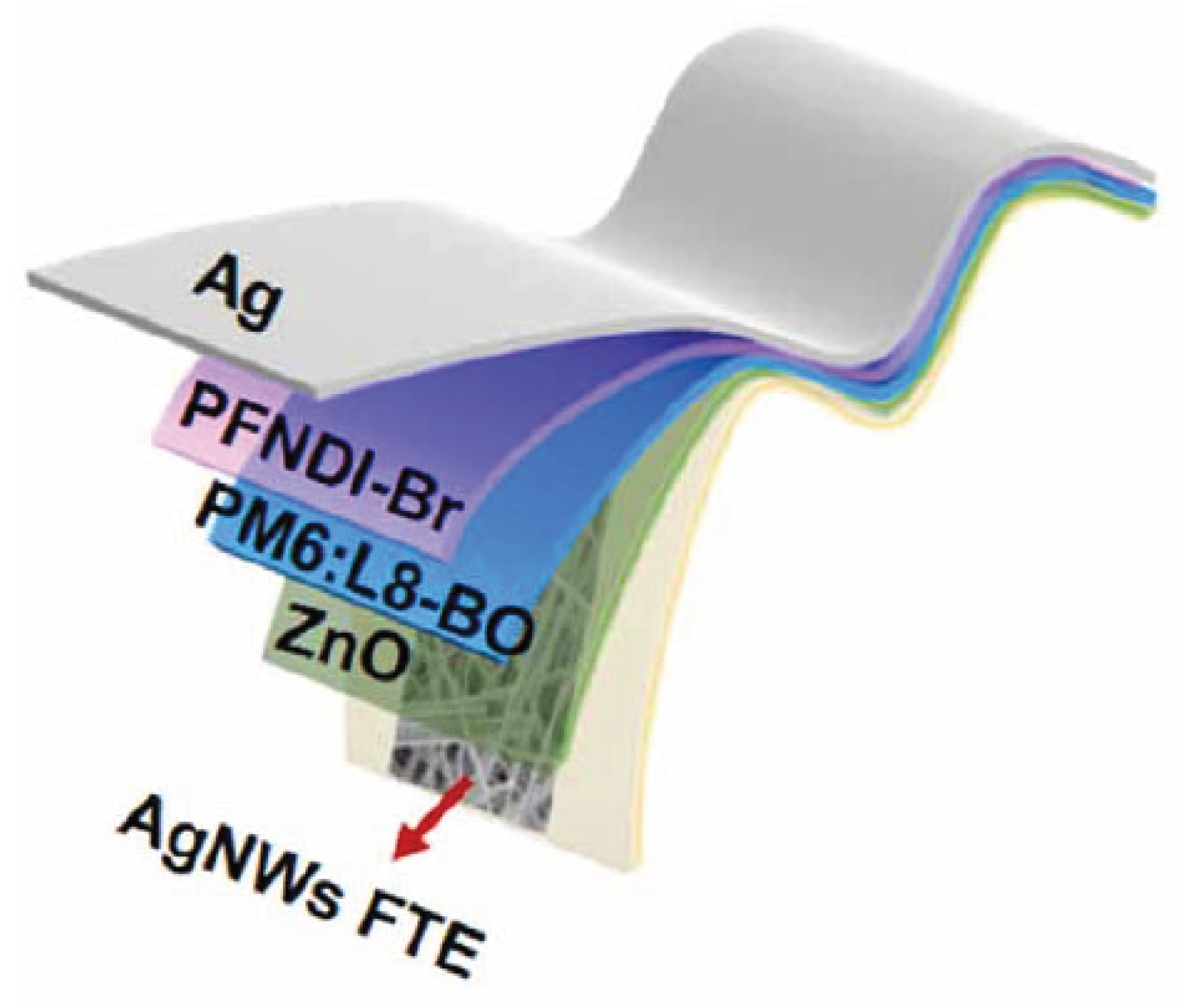

5.2. Organic Solar Cells (OSCs)

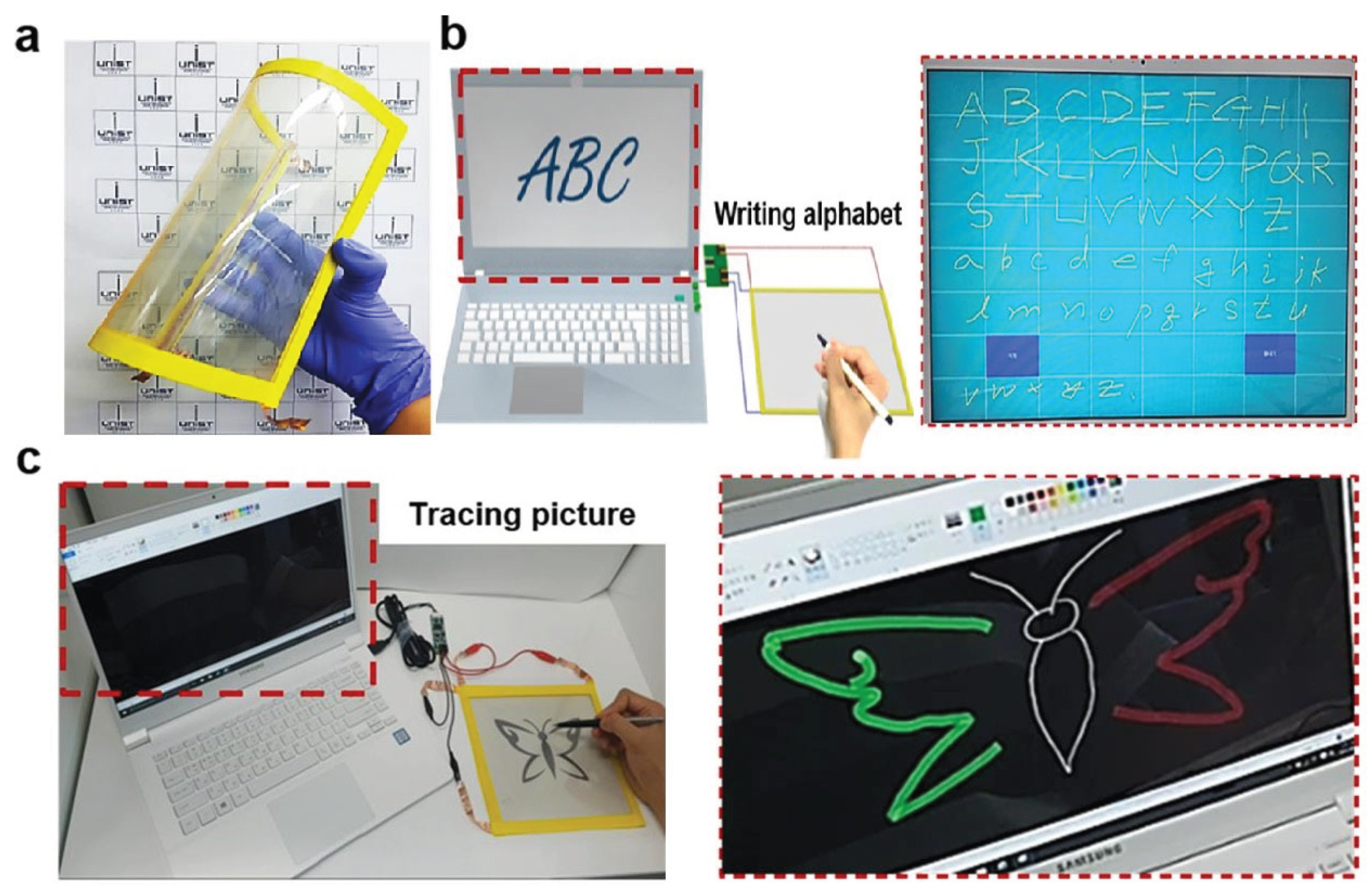

5.3. Flexible Sensors

5.4. Electromagnetic Shielding

5.5. Other Important Applications

6. Stability Challenges and Mitigation in AgNW Networks

6.1. The Degradation Mechanism of AgNWs

6.1.1. Electrical Instability

6.1.2. Thermal Failure

6.1.3. Photodegradation

6.1.4. Chemical Corrosion

6.2. Mitigation Strategies

6.2.1. Surface Encapsulation

6.2.2. Stabilization Additives

6.2.3. Hybrid Nanocomposites

6.2.4. Process Optimization

6.3. Future Challenges and Research Directions

7. Conclusions and Outlook

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Outlook and Future Directions

- Despite significant progress, critical challenges remain:

- Uniformity & Scalability: Achieving nanoscale homogeneity in large-area films requires roll-to-roll (R2R) compatible processes. Screen printing and spray coating show industrial potential but need improved thickness control.

- Long-Term Stability: Degradation under thermal (>200°C), UV, and chemical stresses necessitates robust encapsulation. Hybrid approaches (e.g., GO/AgNW) and ALD-grown oxide barriers (Al₂O₃, TiO₂) offer promising solutions.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Reducing silver usage via optimized network density and low-cost ink formulations (e.g., HPMC-AgNW) is vital for commercialization.

- 2.

- Future research should prioritize:

- Advanced Modeling: Develop multiscale simulations to predict failure modes (e.g., hotspot formation under electrothermal stress).

- Standardized Testing: Establish unified metrics for lifetime assessment under combined stressors (thermal-humidity-mechanical cycling).

- Emerging Applications:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim Kwang-Seok; Kim Sun Ok; Han Chul Jong; Kim Dae Up; Kim Jin Soo; Yu Yeon-Tae; Lee Cheul-Ro; Kim Jong-Woong. Revisiting the thickness reduction approach for near-foldable capacitive touch sensors based on a single layer of Ag nanowire-polymer composite structure. Composites Science and Technology, 2018, 165, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji Animesh; Kuila Chinmoy; Panda Bholanath; Dhak Debasis; Murmu Naresh Chandra; Kuila Tapas*. Tailoring AgNWs-rGO/PVDF advanced composites for flexible strain sensors in wearable electronics with thermal management: balancing sensitivity and hysteresis. ACS Applied Electronic Materials, 2025, 7, 1670–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Ziye; Niu Ziying; Wang Yongqiang; Xu Zijie; Liu Yunlong; Wang Wenjun; Li Shuhong. Flexible OLED Performance Enhancement: The impact of AgNWs: AgNPs electrode-integrated MoOX QDs hole-injection layer. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2025, 17, 10898–10906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Juanyong; Chen Yang; Chen Weijie; Xia Jinfeng; Zeng Guang; Cao Jianlei; Jin Chuang; Shen Yunxiu; Wu Xiaoxiao; Chen Haiyang; Ding Junyuan; Ou Xue mei; Li Yaowen; Li Yongfang. Enhanced charge collection of AgNWs-based top electrode to realize high-performance, all-solution processed organic solar cells. Science China Chemistry, 2024, 67, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Xingya; Dai Hongfei; Ji Mengnan; Han Ying; Jiang Bo; Cheng Chi; Song Xiaolei; Song Ying; Wu Guangfeng. A flexible piezoresistive strain sensor based on AgNWs/MXene/PDMS sponge. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2025, 36, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Bozhen; Yu Yujing; Wu Peng; Wu Yidong; Huang Jiang; Song Xuejiao. SiC whisker/AgNWs/TPU composite film with asymmetric structure for low-reflection electromagnetic interference shielding. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2024, 141, e56019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma Vibha; Arora Ekta Kundra; Jaison Manav; Vashist Tamanna; Jagtap Shweta; Adhikari Arindam; Kumar Pawan; Dash Jatis Kumar; Patel Rajkumar. Tuning the work function and properties of the conducting polymer PEDOT:PSS for enhancing optoelectronic device performance of solar cells and organic light emitting diodes. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials, 2025, 64, 1019–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz M. H.; Al-Hossainy A. F.; Ibrahim A.; El-Maksoud S. A. Abd; Zoromba M. Sh.; Bassyouni M.; S. Abdel-Hamid M. S.; Abd-Elmageed A. A. I.; Elsayed I. A.; Alqahtani O. M. Retraction note: synthesis, characterization and optical properties of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/aniline-o-anthranilic acid copolymer nanocomposite thin films. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2025, 36, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadmehr Sadegh; Alamdari Sanaz; Tafreshi Majid Jafar. Flexible and transparent highly luminescent sensor based on doped zinc tungstate/graphene oxide nanocomposite. The European Physical Journal Plus, 2025, 140, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achagri Ghizlane; Ismail Rimeh; Kadier Abudukeremu; Ma Peng Cheng. A solar-powered electrocoagulation process with a novel CNT/silver nanowire coated basalt fabric cathode for effective oil/water separation: From fundamentals to application. Journal of Environmental Management, 2025, 375, 124289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo Zhijiang; Li Xiaoli; Li Ning; Liu Xuanji; Li Haojie; Li Xuezhi; Wang Yuxuan; Liang Jianguo; Chen Zhanchun. Multilayer directionally arranged silver nanowire networks for flexible transparent conductive films. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics: PCCP, 2023, 25, 14778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao Jingqi; Liu Ni; Li Shuxin; Shi Jun; Ji Shulin. Structural manipulation of silver nanowire transparent conductive films for optoelectrical property optimization in different application fields. Thin Solid Films, 2021, 729, 138679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Xingchao; Zhang Yuqiang; Ma Chuao; Liu Hongliang. Large-area, stretchable, ordered silver nanowires electrode by superwetting-induced transfer of ionic liquid@silver nanowires complex. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023, 476, 146505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Ping; Tong Xingrui; Gao Yi; Qian Zhongyuan; Ren Ruirui; Bian Chenchen; Wang Jinhui; Cai Guofa. A sensing and stretchable polymer-dispersed liquid crystal device based on spiderweb-inspired silver nanowires-micromesh transparent electrode. Advanced Functional Materials, 2023, 33, 2303270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang Qiheng; Zou Miao; Chang Liang; Guo Wenjing. A super-flexible and transparent wood film/silver nanowire electrode for optical and capacitive dual-mode sensing wood-based electronic skin. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2022, 430, 132152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao Tingting; Zhang Leipeng; Ji Haoyu; Zhou Qiyu; Feng Ting; Song Shanshan; Wang Bo; Liu Dongqi; Ren Zichen; Liu Wenchao; Zhang Yike; Sun Jiawu; Li Yao. A stretchable, transparent, and mechanically robust silver nanowire-polydimethylsiloxane electrode for electrochromic devices. Polymers, 2023, 15, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Xiaoguang; Song Chengjun; Wang Yangyang; Feng Shaoxuan; Xu Dong; Hao Tingting; Xu Hongbo. Flexible transparent films of oriented silver nanowires for a stretchable strain sensor. Materials, 2024, 17, 4059–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Dong-Hwan; Yu Ki-Cheol; Kim Youngmin; Kim Jong-Woong. Highly stretchable and mechanically stable transparent electrode based on composite of silver nanowires and polyurethane-urea. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2015, 7, 15214–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Neethu; Sharma Neha; Swaminathan Parasuraman. Optimizing silver nanowire dimensions by the modification of polyol synthesis for the fabrication of transparent conducting films. Nanotechnology, 2023, 35, 055602. [Google Scholar]

- Ge Yongjie; Liu Jianfang; Liu Xiaojun; Hu Jiawen; Duan Xidong; Duan Xiangfeng. Rapid electrochemical cleaning silver nanowire thin films for high-performance transparent conductors. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019, 141, 12251–12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Chenghao; Li Chun; Si Xiaoqing; He Zongjing; Qi Junlei; Feng Jicai; Cao Jian. Single-crystalline silver nanowire arrays directly synthesized onto substrates by template-assisted chemical wetting. Materialia, 2020, 9, 100529–100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorick Bleiji; Andrea Cordaro; Stefan W Tabernig; Esther Alarcón Lladó. High Aspect Ratio Silver Nanogrids by Bottom-Up Electrochemical Growth as Transparent Electrode. ACS applied optical materials, 2024, 2, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou Lu; Yu Mengjie; Yao Lanqian; Lai Wen-Yong. Mayer rod-coated organic light-emitting devices: binary solvent inks, film topography optimization, and large-area fabrication. Advanced Engineering Materials, 2022, 24, 2101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Shuye; Liu Xu; Lin Tiesong; He Peng. A method to fabricate uniform silver nanowires transparent electrode using meyer rod coating and dynamic heating. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2019, 30, 18702–18709. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Sannicolo; Nicolas Charvin; Lionel Flandin; Silas Kraus; Papanastasiou Dorina T; Caroline Celle; Jean-Pierre Simonato; David Muñoz-Rojas; Carmen Jiménez; Daniel Bellet. Electrical mapping of silver nanowire networks: a versatile tool for imaging network homogeneity and degradation dynamics during failure. ACS nano, 2018, 12, 4648–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crêpellière Jonathan; Menguelti Kevin; Wack Sabrina; Bouton Olivier; Gérard Mathieu; Popa Petru Lunca; Pistillo Bianca Rita; Leturcq Renaud; Michel Marc. Spray deposition of silver nanowires on large area substrates for transparent electrodes. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2021, 4, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami Mostafa; Tajabadi Fariba; Taghavinia Nima; Moshfegh Alireza. Chemically-stable flexible transparent electrode: gold-electrodeposited on embedded silver nanowires. Scientific Reports, 2023, 13, 17511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng Jieyuan; Zhao Yajie; Chen Lirong; Zheng Yang; Wang Xingru; Xu Gang; Xiao Xiudi. Unveiling the function and mechanism of the ordered alignment silver nanowires on boosting the electrochromic performance. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023, 463, 142524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song Lijun; Qu Shiru; Ma Lijing; Yu Shihui. All solution prepared WOx/AgNW composite transparent conductive films with enhanced adhesion and stability. Materials Letters, 2023, 336, 133918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi Liren. Flexible transparent silver nanowires conductive films fabricated with spin-coating method. Micro & Nano Letters, 2022, 18, e12151. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Pengchang; Jian Maoliang; Wu Majiaqi; Zhang Chi; Zhou Chenhao; Ling Xiao; Zhang Jianhua; Yang Lianqiao. Highly sandwich-structured silver nanowire hybrid transparent conductive films for flexible transparent heater applications. Composites Part A, 2022, 159, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, V.; Mitra, K.Y.; Castro, H.; Rocha, J.G.; Sowade, E.; Baumann, R.R.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Design and fabrication of multilayer inkjet-printed passive components for printed electronics circuit development. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 2018, 31, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Zhengliang; Zhang Xuyang; Shan Jiaqi; Liu Cuilan; Guo Xingzhong; Zhao Xiaoyu; Yang Hui. Facile fabrication of large-scale silver nanowire transparent conductive films by screen printing. Materials Research Express, 2022, 9, 066401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu Xiaowen; Liu Zhuofang; He Pei; Yang Junliang. Screen-printed silver nanowire and graphene oxide hybrid transparent electrodes for long-term electrocardiography monitoring. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 2019, 52, 455401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Weiwei; Yarali Emre; Bakytbekov Azamat; Anthopoulos Thomas D; Shamim Atif. Highly transparent and conductive electrodes enabled by scalable printing. Nanotechnology, 2020, 31, 395201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan Saleem; Ali Shawkat; Bermak Amine. Smart manufacturing technologies for printed electronics. IntechOpen 2020, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Yuehui; Wu Xiaoli; Wang Ke; Lin Kaiwen; Xie Hui; Zhang Xiaobing; Li Jingze. Novel insights into inkjet printed silver nanowires flexible transparent Conductive Films. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22, 7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Xiaoli; Wang Shuyue; Luo Zhengwu; Lu Jiaxin; Lin Kaiwen; Xie Hui; Wang Yuehui; Li JingZe. Inkjet printing of flexible transparent conductive films with silver nanowires ink. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland), 2021, 11, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Milaji Karam Nashwan; Huang Qijin; Li Zhen; Ng Tse Nga; Zhao Hong. Direct Embedment and alignment of silver nanowires by Inkjet printing for stretchable conductors. ACS Applied Electronic Materials, 2020, 2, 3289–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia Li-Chuan; Yan Ding-Xiang; Liu Xiaofeng; Ma Rujun; Wu Hong-Yuan; Li Zhong-Ming. Highly efficient and reliable transparent electromagnetic interference shielding film. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2018, 10, 11941–11949. [Google Scholar]

- Abderrahime Sekkat; Camilo Sanchez-Velasquez; Laetitia Bardet; Matthieu Weber; Carmen Jimenez; Daniel Bellet; David Muñoz-Rojas; Viet Huong Nguyen. Towards enhanced transparent conductive nanocomposites based on metallic nanowire networks coated with metal oxides: a brief review. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2024, 12, 25600–25621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu Rong; Zheng Haoran; Zhao Xiaofang; Yang Pan; Yu Shihui. The high transmittance silver nanowire conductive films with excellent electromagnetic shielding efficiency prepared by electrospinning and magnetron sputtering. Optical Materials, 2024, 157, 116219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Chun-Te, Ho Ying-Rong, Huang Da-Zhan, Huang Jung-Jie. AZO/silver nanowire stacked films deposited by RF magnetron sputtering for transparent antenna. Surface and Coatings Technology, 2019, 360, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Xuanliang; Deng Zhongyang; Long Yu; Feng Bin; Jiang Xin; Liu Xu; Zhong Yujia; Zou Sumeng; Zhen Zhen; Lin Shuyuan; Hu Haowen; Li Jing; Zhao Guoke; Liu Lei; Zou Guisheng; Zhu Hongwei. Multifunctional sensing platform with pulsed-laser-deposited silver nanoporous structures. Sensors & Actuators: A. Physical, 2019, 293, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Vikulova Evgeniia, S.; Dorovskikh Svetlana, I.; Basova Tamara, V.; Zheravin Aleksander, A.; Morozova Natalya, B. Silver CVD and ALD Precursors: Synthesis, Properties, and Application in Deposition Processes. Molecules, 2024, 29, 5705–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Zhenfeng; Li Zihan; Shi Zhiyuan; Zhu Pengyu; Wang Zixu; Zhang Jia; Li Yang; He Peng; Zhang Shuye. ALD prepared silver nanowire/ZnO thin film for ultraviolet detectors. Materials Today Communications, 2023, 37, 106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng Yalian; Chen Guixiong; Zhou Xiongtu; Zhang Yongai; Yan Qun; Guo Tailiang. Stability enhancement and patterning of silver nanowire networks by conformal TiO2 coating for flexible transparent conductive electrodes. Journal of Materials Science, 2023, 58, 17816–17828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang Jiachen; Han Kang; Sun Xue; Zhang Lianping; Huang Rong; Ismail Irfan; Wang Zhenguo; Ding Changzeng; Zha Wusong; Li Fangsen; Luo Qun; Li Yuanjie; Lin Jian; Ma Chang-Qi. Suppression of Ag migration by low-temperature sol-gel zinc oxide in the Ag nanowires transparent electrode-based flexible perovskite solar cells. Organic Electronics, 2020, 82, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho Seungse; Kang Saewon; Pandya Ashish; Shanker Ravi; Khan Ziyauddin; Lee OrcidYoungsu; Park Jonghwa; Craig Stephen L.; Ko Hyunhyub. Large-area cross-aligned silver nanowire electrodes for flexible, transparent, and force-sensitive mechanochromic touch screens. ACS Nano, 2017, 11, 4346–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Mengyang; Yang Zhuo; Miao Yangqin; Wang Chao; Dong Peng; Wang Hua; Guo Kunping. Facile nanowelding process for silver nanowire electrodes toward high-performance large-area flexible organic light-emitting diodes. Advanced Functional Materials, 2024, 34, 2404567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Yuzhou; Liu Yan; Wang Tao; Liu Shuhui; Chen Zeng; Duan Shaobo. Low-temperature nanowelding silver nanowire hybrid flexible transparent conductive film for green light OLED devices. Nanotechnology, 2022, 33, 455201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian Peng-Fei; Geng Wen-Hao; Bao Ze-Long; Jing Li-Chao; Zhang Di; Geng Hong-Zhang. Eco-friendly transparent conductive films formed by silver nanowires embedded with conductive polymers in HPMC for flexible OLEDs. Surfaces and Interfaces, 2025, 56, 105583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Dong Woo; Han Dong Woo; Lim Kwon Taek; Kim Yong Hyun. Highly enhanced light-outcoupling efficiency in ITO-free organic light emitting diodes using surface nanostructure embedded high-refractive index polymers. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2018, 10, 985–991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Sunho; Hwang Byungil. Ag nanowire electrode with patterned dry film photoresist insulator for flexible organic light emitting diode with various designs. Materials & Design, 2018, 160, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Sunho; Kim Jungwoo; Kim Daekyoung; Kim Bongsung; Chae Heeyeop; Yi Hyunjung; Hwang Byungil. High-performance transparent quantum dot light-emitting diode with patchable transparent electrodes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2019, 11, 26333–26338. [Google Scholar]

- Li Huiying; Liu Yunfei; Su Anyang; Wang Jintao; Duan Yu. Promising hybrid graphene-silver nanowire composite electrode for flexible organic light-emitting diodes. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9, 17998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Sang Yun; Nam Yun Seok; Yu Jae Choul; Lee Seungjin; Jung Eui Dae; Kim Si-Hoon; Lee Sukbin; Kim Ju-Young; Song Myoung Hoon. Highly efficient flexible perovskite light-emitting diodes using the modified PEDOT: PSS hole transport layer and polymer silver nanowire composite electrode. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2019, 11, 39274–39282. [Google Scholar]

- Triambulo Rose, E.; Kim Jin-Hoon; Park Jin-Woo. Highly flexible organic light-emitting diodes on patterned Ag nanowire network transparent electrodes. Organic Electronics, 2019, 71, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian Lu; Dong Dan; Feng Dongxu; He Gufeng. Low roughness silver nanowire flexible transparent electrode by low temperature solution-processing for organic light emitting diodes. Organic Electronics, 2017, 49, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Yongmei; Chen Qiaomei; Zhang Guangcong; Xiao Chengyi; Wei Yen; Li Weiwei. Ultrathin flexible transparent composite electrode via semi-embedding silver nanowires in a colorless polyimide for high performance ultraflexible organic solar cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022, 14, 5699−5708. [Google Scholar]

- Lei Tao; Peng Ruixiang; Song Wei; Hong Ling; Huang Jiaming; Fei Nannan; Ge Ziyi. Bendable and foldable flexible organic solar cells based on Ag nanowire films with 10.30% efficiency. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2019, 7, 3737–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song Wei; Yu Kuibao; Zhou Erjun; Xie Lin; Hong Ling; Ge Jinfeng; Zhang Jinsheng; Zhang Xiaoli; Peng Ruixiang; Ge Ziyi. Crumple durable ultra flexible organic solar cells with an excellent ower-per-weight performance. Advanced Functional Materials, 2021, 31, 2102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi Jiabin; Chen Shuo; Lan Chuntao; Wang Aurelia Chi; Cui Xun; You Zhengwei; Zhang Qinghong; Li Yaogang; Wang Zhong Lin; Wang Hongzhi; Lin Zhiqun. Large-grained perovskite films enabled by one-step meniscus-assisted solution printing of cross-aligned conductive nanowires for biodegradable flexible solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials, 2020, 10, 2001185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin Wenfeng; Xue Yunsheng; Li Gang; Peng Hao; Gong Guochong; Yan Ran; Zhao Xin; Pang Jie. Highly-sensitive wearable pressure sensor based on AgNWs/MXene/non-woven fabric. Organic Electronics, 2024, 125, 106958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Xue; Jin Jiarui; Liu Bing; Li Sheng; Guo Tao; Sheng Zongqiang; Wu Hongwei. Flexible and transparent leaf-vein electrodes fabricated by liquid film rupture self-assembly AgNWs for application of heaters and pressure sensors. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2024, 499, 156500–156500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-López Dulce Natalia; Gómez-Pavón Luz del Carmen; Gutíerrez-Nava Alfredo; Zaca-Morán Placido; Arriaga-Arriaga Cesar Augusto; Muñoz-Pacheco Jesús Manuel; Luis-Ramos Arnulfo. Flexible force sensor based on a PVA/AgNWs nanocomposite and cellulose acetate. Sensors, 2024, 24, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Xinbo; Cai Guoqiang; Song Jiangxiao; Zhang Yan; Yu Bin; Zhai Shimin; Chen Kai; Zhang Hao; Yu Yihao; Qi Dongming. Large-scale fabrication of tunable sandwich-structured silver nanowires and aramid nanofiber films for exceptional electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding. Polymers, 2023, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo Zhengzheng; Zha Yidan; Luo Peien; Chen Zhengyan; Song Ping; Jin Yanling; Pei Lu; Ren Fang; Ren Penggang. Durable and sustainable CoFe2O4@MXene-silver nanowires/cellulose nanofibers composite films with controllable electric–magnetic gradient towards high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding and Joule heating capacity. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2024, 485, 149691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Duy Khiem; Pham Trung Nhan; Pham Ai Le Hoang; Nguyen Van Cuong; Tran Minh-Sang; Bui Viet Quoc; Vu Minh Canh. Multilayered silver nanowires and graphene fluoride-based aramid nanofibers for excellent thermosconductive electromagnetic interference shielding materials with low-reflection. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2024, 688, 133553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer Sébastien; Celle Caroline; Crivello Chiara; Szambolics Helga; MuñozRojas David; Bellet Daniel; Simonato JeanPierre. Transparent and Mechanically Resistant Silver-Nanowire-Based Low-Emissivity Coatings. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2021, 13, 21971–21978. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Su Bin; Meena Jagan Singh; Joo Jinho; Kim Jong Woong. Autonomous self-healing wearable flexible heaters enabled by innovative MXene/polycaprolactone composite fibrous networks and silver nanowires. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials, 2023, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano Gianluca; Pedretti Giacomo; Montano Kevin; Ricci Saverio; Hashemkhani Shahin; Boarino Luca; Ielmini Daniele. Ricciardi CarloIn materia reservoir computing with a fully memristive architecture based on self-organizing nanowire networks. Nature materials 2021, 21, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Charvin Nicolas; Resende Joao; Papanastasiou Dorina T. ; Munoz Rojas David; Jimenez Carmen; Nourdine Ali; Bellet Daniel; Flandin Lionel. Dynamic degradation of metallic nanowire networks under electrical stress: a comparison between experiments and simulations. Nanoscale Advances, 2021, 3, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazioli Davide; Gangi Gabriele; Nicola Lucia; Simone Angelo. Predicting mechanical and electrical failure of nanowire networks in flexible transparent electrodes. Composi Science and Technology 2024, 245, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh Harim; Lee Jeeyoung; Lee Myeongkyu. Transformation of silver nanowires into nanoparticles by rayleigh instability: comparison between laser irradiation and heat treatment. Applied Surface Science, 2018, 427, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang Byungil; An Youngseo; Lee Hyangsook; Lee Eunha; Becker Stefan; Kim Yong-Hoon; Kim Hyoungsub. Highly flexible and transparent Ag nanowire electrode encapsulated with Ultra-Thin Al2O3: thermal, ambient, and mechanical stabilities. Scientific reports, 2017, 7, 41336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong Yong-Chan; Nam Jiyoon; Kim Jongbok; Kim Chang Su; Jo Sungjin. Enhancing thermal oxidation stability of silver nanowire transparent electrodes by using a cesium carbonate-incorporated overcoating layer. Materials, 2019, 12, 1140–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Chiao-Chi; Lin Dong-Xuan; Lin Shih-He. Degradation problem in silver nanowire transparent electrodes caused by ultraviolet exposure. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 215705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan Zheng; Chen Hongye; Li Min; Wen Xiaoyan; Yang Yingping; Choy Wallace C. H.; Lu Haifei. Observing and understanding the corrosion of silver nanowire electrode by precursor reagents and MAPbI3 film in different environmental conditions. Advanced Materials Interfaces, 2021, 8, 2001669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh Ming-Hua; Chen Po-Hsun; Yang Yi-Ching; Chen Guan-Hong; Chen Hsueh-Shih. Investigation of Ag-TiO2 interfacial reaction of highly stable Ag nanowire transparent conductive film with conformal TiO2 coating by atomic layer deposition. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2017, 9, 10788–10797. [Google Scholar]

- Entifar Siti Aisyah Nurmaulia; Han Joo Won; Lee Dong Jin; Ramadhan Zeno Rizqi; Hong Juhee; Kang Moon Hee; Kim Soyeon; Lim Dongchan; Yun Changhun; Kim Yong Hyun. Simultaneously enhanced optical, electrical, and mechanical properties of highly stretchable transparent silver nanowire electrodes using organic surface modifier. Science and technology of advanced materials, 2019, 20, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai Suresh Kumar Raman; Wang Jing; Wang Yilei; Sk Md Moniruzzaman; Prakoso Ari Bimo; Rusli; Chan-Park Mary B. Totally embedded hybrid thin films of carbon nanotubes and silver nanowires as flat homogenous flexible transparent conductors. Scientific reports, 2016, 6, 38453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang Yan; Ruan Haibo; Liu Hongdong; Zhang Jin; Shi Dongping; Han Tao; Yang Liu. Low-temperature solution processed flexible silver nanowires/ZnO composite electrode with enhanced performance and stability. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 747659–747665. [Google Scholar]

- Choo Dong Chul; Kim Tae Whan. Degradation mechanisms of silver nanowire electrodes under ultraviolet irradiation and heat treatment. Scientific reports, 2017, 7, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil Jatin J; Chae Woo Hyun; Trebach Adam; Carter KiJana; Lee Eric; Sannicolo Thomas; Grossman Jeffrey C. Failing Forward: Stability of Transparent Electrodes Based on Metal Nanowire Networks. Advanced materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.), 2020, 33, e2004356. [Google Scholar]

| Method of Film Deposition | Tav / % | Rs / Ω·sq-1 | FOM | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meyer Rod Coating | 92.2 | 12.9 | 352.33 | [11] |

| Meyer Rod Coating | 91 | 10 | 390.08 | [24] |

| Spraying | 91.7 | 9 | 709 | [26] |

| Spraying | 86.6 | 18.3 | 138 | [28] |

| Spin Coating | 82.6 | 9.4 | 199.78 | [29] |

| Spin Coating | 87.5 | 14.4 | 189.44 | [31] |

| Silk-screen printing | 95.3 | 13.6 | 568.47 | [33] |

| Inkjet Printing | 83.1 | 34.0 | 57.12 | [37] |

| Inkjet Printing | 74 | 2.9 | 399.74 | [38] |

| Preparation Method | Film Uniformity | Equipment Cost | Production Efficiency | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meyer Rod Coating | good | low | slow | small scale in the laboratory |

| Spin Coating | excellent (small area) |

Moderate (except high-precision) |

fast (small-area) | electronic, optical devices |

| Spraying | moderate (dependent on spray control) | moderate | fast | architectural glass, solar cells |

| Silk-screen printing | moderate (except for edges and corners) | low (except high-precision) |

fast | electronic circuits, sensors |

| Inkjet Printing | excellent (sprinkler head) |

high (spray head and ink) |

low (large-area) fast (small-area) |

microelectronics, Flexible Electronics, Biosensors |

| Preparation Method | Film Uniformity | Equipment Cost | Production Efficiency | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputtering Deposition | excellent (dense, regular-structured) | high | medium | TCEs (e.g., displays, solar cells) |

| Pulsed layer deposition (PLD) | excellent (precise patterning) | very high | low (small-area) |

high-performance electronic devices (e.g., gas sensors, high-frequency electronic components) |

| Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) | excellent (large-area, high-quality) | very high | high (large-area) |

flexible electronic devices (e.g., flexible display screens, wearable devices) |

| Atomic layer deposition (ALD) | extremely high (atomic level) | very high | low (layer-by-layer deposition) | high-stability electrodes (e.g., lithium battery electrodes, UV photodetectors) |

| Solution methods | poor (porous structure) | low | relatively high | flexible wearable devices (e.g., flexible circuits, biosensors), low-cost optoelectronic devices |

| Material | Substrate | Area(cm2) | Turn-on voltage(V) | Maximum Current Efficiency(cd/A) | Maximum Luminance(cd/m2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPMN-processed AgNWs | PET | 2.5 × 2.5 | 3 | 78.0 | 5118 | [50] |

| Ti3C2Tx / AgNWs |

PEDOT: PSS |

4 × 4 | 7 | 3.7 | 10040 | [51] |

| HRLOC/ AgNWs |

PI | 20 × 20 | 18.37 | 20000 | [53] | |

| AgNWs | GLASS | 4 × 4 | 5.5 | 45.99 | 27310 | [55] |

| Graphene /AgNWs | PET | 9 | 15000 | [56] | ||

| AgNWs/ITO | PI | 1 × 1 | 7.7 | 5000 | [58] | |

| PVA/AgNWs | PEN | 10 | 35.3 | 18540 | [59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).