1. Introduction

Papillomaviruses (PVs) are small, circular, double-stranded DNA viruses known to cause both pre-neoplastic and neoplastic diseases across various species, including humans, cats, horses, and dogs [

1,

2]. Classified within the

Papillomaviridae family, PVs are categorized based on the nucleotide sequence similarity of the L1 gene, biological properties, and phylogenetic tree topology [

1,

2]. In dogs, most infections with

Canis familiaris Papillomavirus (canine papillomavirus - CPV) are asymptomatic [

3]. However, CPVs have been implicated in causing conditions such as hyperplastic lesions [

4] and, less frequently, neoplastic diseases [

5]. Currently, 33 CPV types have been identified and are divided into three genera

Lambdapapillomavirus,

Taupapillomavirus, and

Chipapillomavirus according to the Papillomavirus Episteme (PaVE) database (

https://pave.niaid.nih.gov), with some types still unclassified [

6].

CPVs are associated with various lesions, including oral and cutaneous papillomatosis, pigmented plaques, and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. While most canine pigmented plaques are small and localized, cases of extensive and disseminated plaques have been reported, with rare instances progressing to SCC [

7]. Specific CPV types, such as CPV16, are believed to have a higher potential for neoplastic transformations, although other types have also been found in lesions undergoing malignant changes [

3,

7,

10,

11,

12]. In contrast, according to PaVE, over 400 human papillomavirus (HPV) types have been characterized. Despite recent reports of new viral types and co-infections, CPV diversity remains notably low. Factors such as viral evolution, anthropogenic landscape changes, and global climate shifts significantly influence the incidence and geographic distribution of viral agents affecting both animal and human populations.

The Amazon region, with its unparalleled biodiversity and complex ecosystems, highlights the critical need for virology research. Understanding how environmental factors contribute to the emergence and transmission of various viral pathogens is essential. Therefore, there is an urgent need for studies analyzing the genetic diversity of CPVs, particularly on Amazon. Thus, this study aims to identify the papillomavirus types present in oral and cutaneous papillomatous lesions in dogs from the Western Amazon region of Brazil. By expanding our knowledge of CPV diversity and its potential health implications, this research will provide valuable insights into canine virology and inform veterinary practices in biodiversity-rich areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Sampling and Histopathological Evaluation

This study included 61 domiciled dogs clinically presenting papillomatous lesions—38 with cutaneous and 23 with oral lesions—originating from Acre (n = 18) and Rondônia (n = 43) states in the Western Brazilian Amazon. To ensure a minimally invasive procedure, lesion samples were collected under local infiltrative anesthesia using 2% lidocaine without vasoconstrictor (Ceva, São Paulo, SP, Brazil). Sterile scalpels and forceps were used for excision. Following collection, each lesion was divided: one fragment was stored at –20 °C for subsequent DNA extraction, while 54 lesion samples, depending on tissue availability, were fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde for histopathological examination.

Detailed clinical data were recorded for all dogs, including sex, age, breed, anatomical location, and the macroscopic morphology of lesions. Based on visual examination, lesions were classified into six distinct types: (1) cauliflower-like—irregular with a broad base; (2) filiform—thin projections resembling grains of rice; (3) nodular—raised, 1–2 cm in diameter; (4) dome-shaped—small, endophytic, approximately 4 mm; (5) papular—small (≈2 mm) flat lesions; and (6) pigmented plaques—hyperpigmented patches of skin.

To minimize animal suffering, all procedures were carried out in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (2010/63/EU, revised 2010) and in accordance with Colégio Bra-sileiro de Experimentação Animal (COBEA). The project was approved by the Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais da Universidade Federal do Acre (protocol number 23107.005499/2018-96).

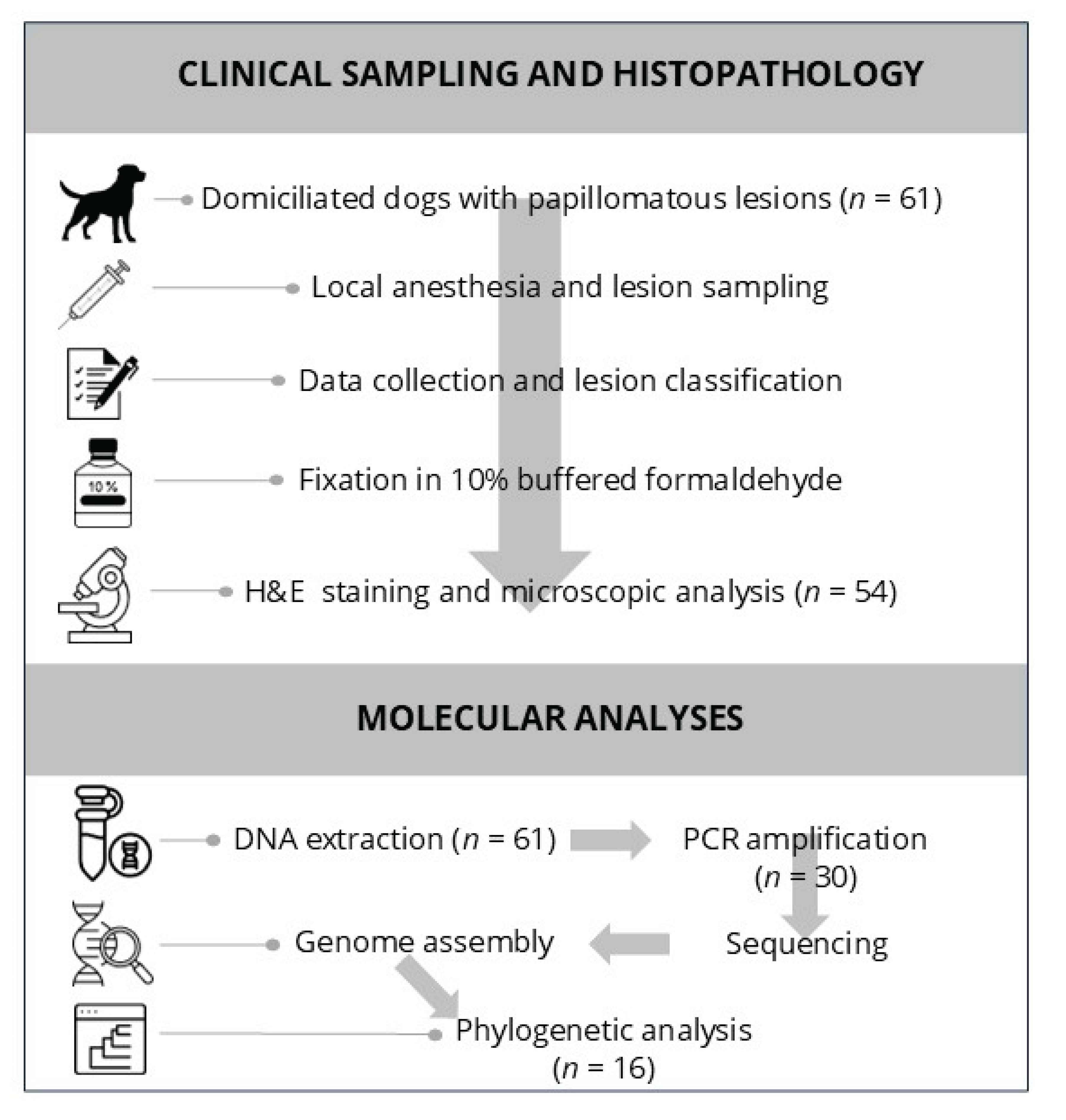

For histopathological processing, formalin-fixed tissues were kept in solution for at least 72 h, processed routinely, and sectioned at 3 μm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined microscopically by a veterinary pathologist. A visual overview of the clinical sampling and histopathological workflow is presented in

Figure 1.

2.2. Molecular Analyses: DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Phylogenetic Inference

Approximately 25 mg of each lesion was used for DNA extraction using the PureLink® Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted DNA was stored at –20 °C.

To detect papillomaviral DNA, partial amplification of the L1 gene was performed using degenerate primers FAP59 and FAP64, as previously described [

13]. PCR products were purified using the PureLink® Quick PCR Purification Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and sequenced using the ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit. The resulting data were processed with Data Collection 3 software and converted to FASTA format using Sequence Analysis Software v6 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Consensus sequences were assembled using Geneious Prime software, and sequence identity was assessed via BLASTn and BLASTx against GenBank databases.

To obtain the complete viral genomes, rolling circle amplification (RCA) was applied to three samples with higher DNA quality and concentration using the TempliPhi™100 Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare, Burlington, MA, USA) [

14,

15]. The RCA products were purified, and their concentration and purity were measured using NanoDrop™ and Qubit™ systems (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA libraries were prepared using 50 ng of purified DNA with the Nextera XT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform using the v2 reagent kit (300 cycles).

Sequence data quality was evaluated with FastQC. Reads were trimmed at the 3′ end using a Phred quality threshold of 20 and assembled into contigs with SPAdes v3.5. Chimeric sequences were excluded based on RDP4 software analysis [

16]. Assembled sequences were annotated and analyzed using Geneious Prime, and alignment with known papillomavirus sequences was performed using MAFFT [

17]. The final phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method with the HKY model and 1000 bootstrap replicates in IQ-TREE [

18].

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Clinical and Histopathological Findings

Among the 61 dogs evaluated, clinically evident papillomatous lesions were primarily distributed in the oral cavity and limbs. The lesions varied in morphology, including cauliflower-like, nodular, filiform, and pigmented plaque presentations.

Table 1 compiles all individual case data, including PCR results (including phylogeny findings), breed, age, sex, lesion location, and detailed macroscopic and histological characterizations.

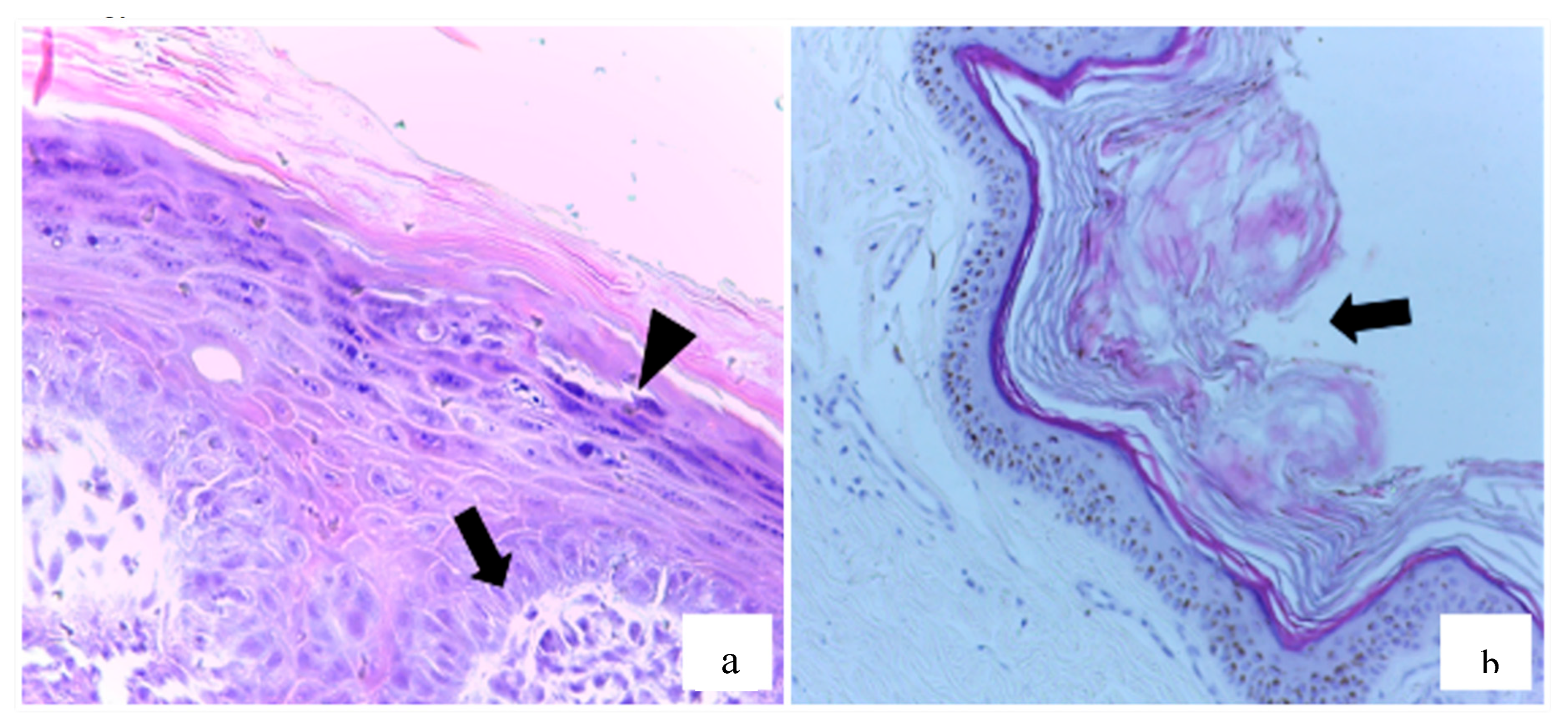

Histopathological analysis was performed on 54 samples (88.5%), of which 20 (37%) were diagnosed as squamous papilloma (SP). These cases exhibited hallmark features such as epidermal hyperplasia, marked hyperkeratosis, and hypergranulosis (

Figure 2a). In some instances, there was fibroblast proliferation within the dermis (

Figure 2b), as well as lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrates, keratohyalin granules, and intranuclear inclusions—consistent with papillomavirus etiology.

3.2. Papillomavirus Detection and Lesion Classification

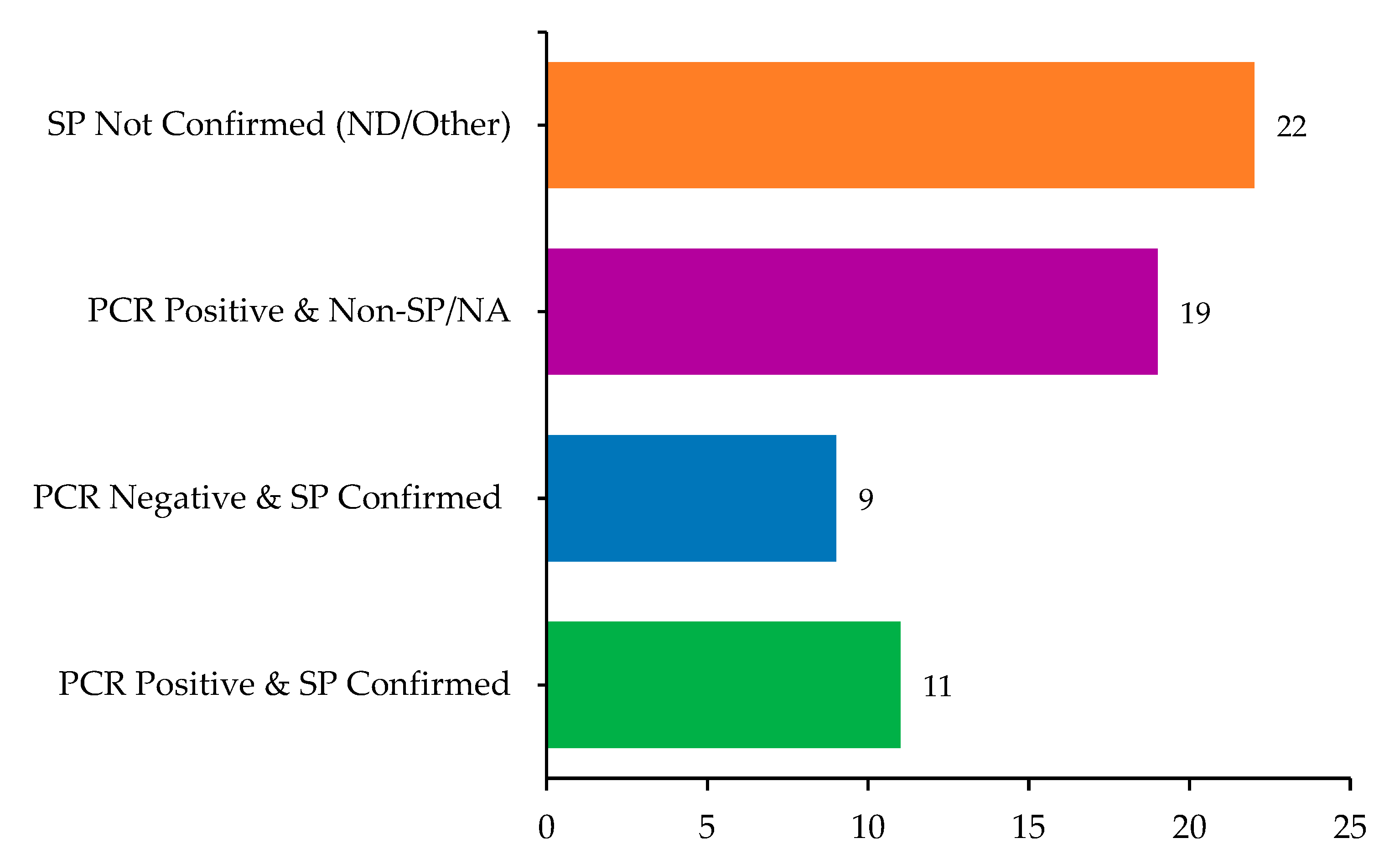

Of the 61 samples, 30 (49.2%) tested positive for papillomavirus DNA using PCR, including both cutaneous and oral lesions. Among these PCR-positive samples, 11 (36.7%) were also histologically confirmed as SP. Conversely, nine PCR-negative lesions (29%) were histologically consistent with SP, suggesting either low viral load or the presence of unamplified PV types. The overlap and divergence between molecular and histopathological diagnoses are summarized in

Figure 3.

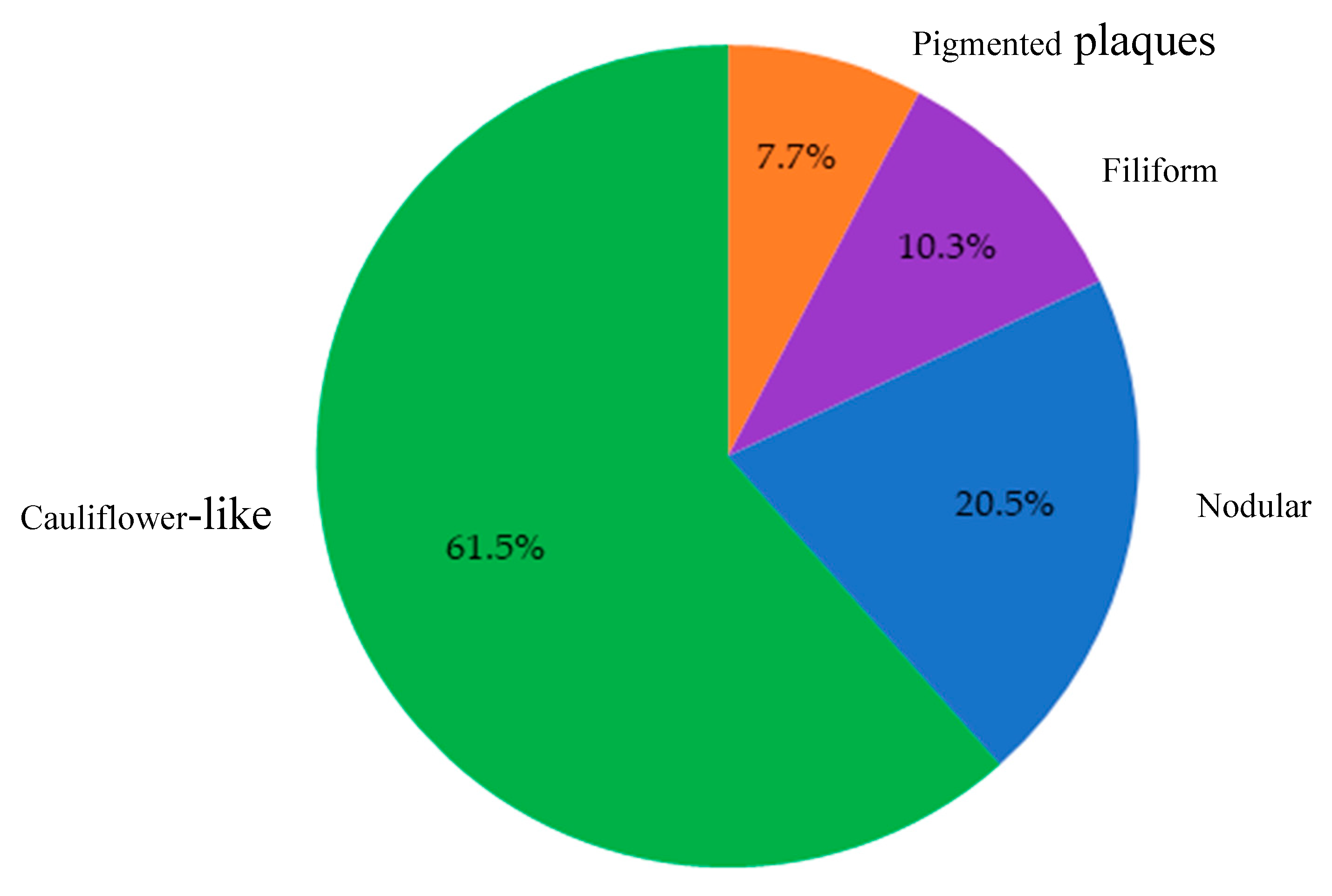

Overall, 39 cases were confirmed by either PCR and/or histopathology as consistent with CPV infection. These lesions predominantly exhibited cauliflower-like macroscopic morphology (61.5%), followed by nodular (20.5%), filiform (10.3%), and pigmented plaques (7.7%). Macroscopically, the lesions identified as papillomatosis or CPV-positive were predominantly cauliflower-like, followed by nodular, filiform, and pigmented plaques (

Figure 4).

3.3. Histological Analysis of Non-Papillomatous Lesions

Lesions that did not meet the criteria for SP diagnosis (n=24) were histologically classified into various categories. These included sebaceous adenomas, melanocytomas, histiocytomas, chronic otitis, and trichoblastomas, among others. Several samples showed non-specific hyperkeratosis or inflammatory changes, and some were deemed inconclusive or lacking significant histopathological alterations (

Table 2).

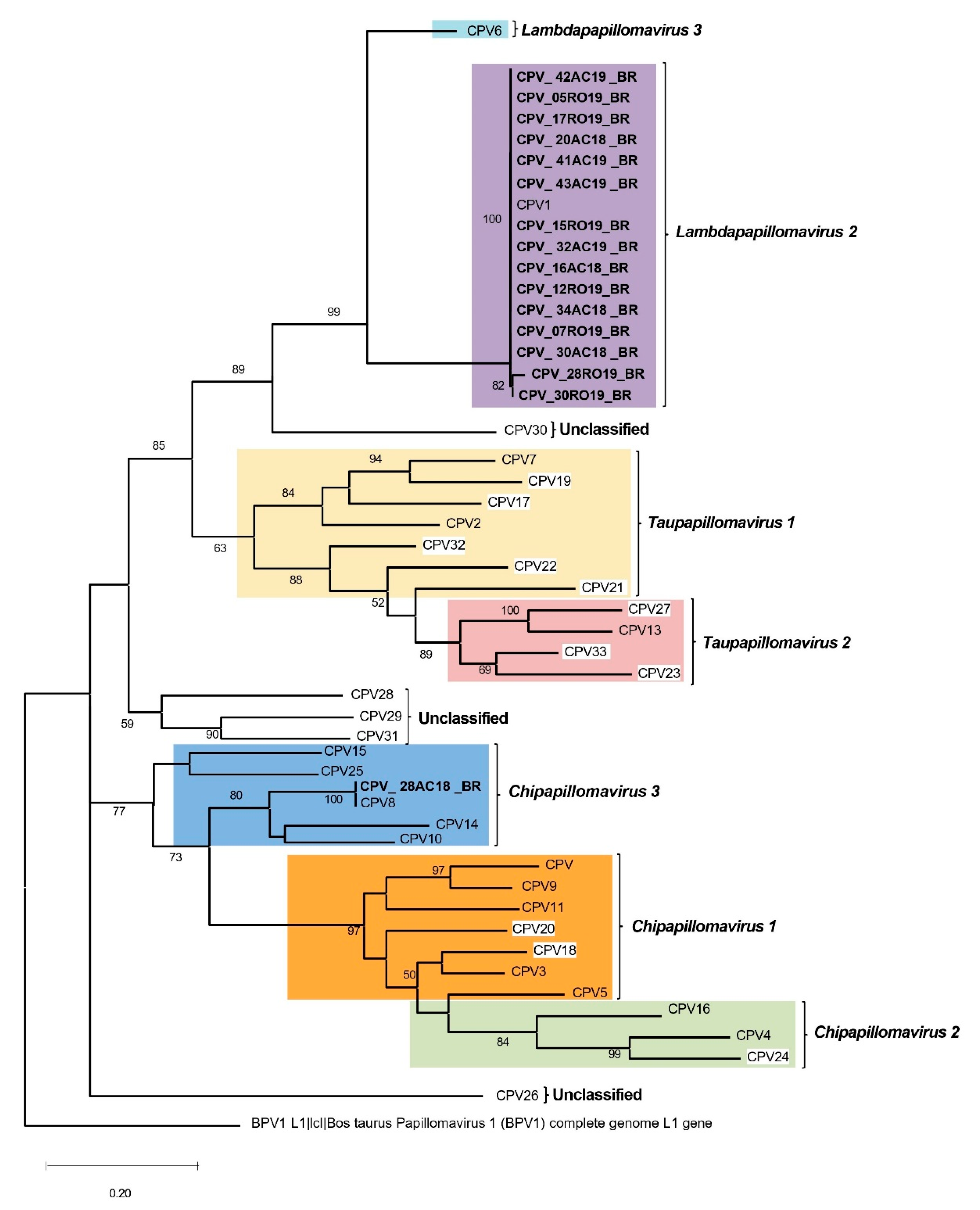

3.4. Phylogenetic Characterization of CPV

Of the PCR-positive samples, 16 yielded high-quality L1 sequences suitable for phylogenetic analysis. Most sequences showed >99% nucleotide identity with CPV1, the prototype of the Lambdapapillomavirus 2 species (GenBank NC_001619). One notable exception was sample 28AC18BR, which exhibited 99% identity with CPV8, a member of the Chipapillomavirus 3 species, and 98% identity with a Swiss CPV8 strain (GenBank YP_004857848) associated with pigmented plaques.

The phylogenetic tree based on the partial L1 region (

Figure 5) confirmed the taxonomic placement of CPV1 and CPV8 among known Canis familiaris papillomaviruses, demonstrating strong bootstrap support for the respective clades.

3.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Selected Isolates

Three samples (16AC18BR, 20AC18BR, and 34AC19BR) with high DNA quality were selected for whole-genome sequencing via high-throughput sequencing. The complete genomes ranged from 8,607 to 8,626 bp, and all included the canonical PV gene set: E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7, L1, L2, and a URR (upstream regulatory region). Genome coverage depth ranged from 20x to 35x, ensuring high confidence in base calling and genomic structure. All three genomes clustered within Lambdapapillomavirus 2 (CPV1), supporting the partial L1-based findings.

4. Discussion

Papillomavirus infections in dogs most commonly manifest as oral and cutaneous papillomas, both of which are typically recognizable through clinical examination due to their characteristic exophytic, verrucous appearance [

19,

20]. In this study, 61 lesions with macroscopic features consistent with papillomatosis were collected from domiciled dogs in the Western Brazilian Amazon. The most frequently affected regions were the oral cavity (37.7%) and limbs (14.8%), consistent with the anatomical predilections reported in previous literature [

20,

25].

Although papillomatosis is classically considered a disease of young dogs with immature immune systems [

20], our findings challenge this paradigm. Among the 39 dogs confirmed by PCR and/or histopathology, only eight were ≤ 2 years of age, while 28 animals were older, 10 of which were over 10 years. These results suggest that factors beyond age-related immune status, such as individual immunogenetics, co-infections, or environmental pressures, may influence disease expression. This notion aligns with studies demonstrating that many dogs may harbor papillomavirus DNA asymptomatically, with lesion development being contingent on immune dysregulation [

19,

21].

The detection of papillomavirus DNA by PCR in 49.2% of cases underscores the challenges inherent to molecular diagnosis in PV infections. Despite using the broad-range FAP59/64 primers, nearly half of the lesions tested negative. This is not unexpected, given that these degenerate primers preferentially amplify a limited spectrum of CPV types (1–5, 7) and may fail to detect divergent or low-copy-number variants [

21,

22]. Furthermore, the “hit-and-run” oncogenic model provides a compelling explanation for histologically confirmed squamous papillomas (SPs) lacking detectable viral DNA. In this model, the viral genome is required to initiate—but not maintain—neoplastic transformation [

23].

Interestingly, of the 20 SPs identified by histopathology, nine were PCR-negative. These cases reinforce the importance of combining histopathological evaluation with molecular tools, as reliance on PCR alone could lead to underdiagnosis. Our data also support previous observations that papillomavirus infections in dogs may follow heterogeneous clinical courses, influenced by complex virus–host–environment interactions [

3,

10].

To date, 33 distinct CPV types have been described, each demonstrating varying tissue tropism and pathogenic potential [

6,

9]. In our study, CPV1 was the predominant type detected, aligning with its known association with oral and cutaneous papillomas and its wide global distribution across five continents [

24,

25,

26,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. CPV1-positive lesions in this cohort included nodular, filiform, cauliflower-like, and even pigmented plaque morphologies—suggesting phenotypic versatility of this genotype. This reinforces the concept that CPV1 remains the most ubiquitous and clinically relevant papillomavirus in dogs.

Notably, one sample (28AC18BR) revealed CPV8, a virus traditionally associated with pigmented plaques and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, particularly in

Chipapillomavirus infections [

9,

26,

27]. However, in this case, CPV8 was detected in a filiform SP, which closely resembled classical benign papillomas rather than pigmented plaques. This finding raises important questions regarding the pathogenic spectrum of CPV8 and supports its potential to induce diverse lesion types. Its high sequence identity with a CPV8 strain from Switzerland [YP_004857848] further suggests that this genotype is conserved across distant geographic regions, despite differences in lesion phenotype.

The histological features of confirmed SPs in this study—epidermal hyperplasia, marked hyperkeratosis, fibroblast proliferation, and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions—were consistent with those described in the literature [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Lesions were most commonly localized to the lips, oral mucosa, and head, a distribution pattern also reported in studies from southern and northeastern Brazil [

28,

29].

The sequencing of partial L1 genes from 16 PCR-positive samples revealed strong identity (>99%) with CPV1, and the three complete genomes obtained confirmed their classification within the

Lambdapapillomavirus 2 species. The low genetic divergence among these CPV1 isolates—even across geographically distinct Brazilian states—highlights the remarkable genomic stability of this virus. These findings are in agreement with previous molecular surveys conducted in South America [

28,

29], North America [

32,

33], Asia [

11], Africa [

34], and Europe [

35,

36].

The detection of CPV1 and CPV8 in dogs from the Western Amazon represents the first molecular and phylogenetic characterization of canine papillomaviruses in this biome. Despite the Amazon's unique ecological complexity, our CPV1 strains were nearly identical to isolates from southern and northeastern Brazil [

28,

29,

37], suggesting either broad viral dissemination or limited mutational drift. This genetic homogeneity raises intriguing questions about the evolutionary constraints and selective pressures acting on CPVs in different environments.

While bovine papillomaviruses (BPVs) have been widely studied and are known for their oncogenic potential and capacity to induce malignant lesions, even in cattle from the amazon region [

38], studies on CPVs remain limited—especially in remote, biodiverse areas such as the Amazon. Unlike BPVs, CPVs are typically associated with benign cutaneous and mucosal lesions in dogs; however, the detection of CPV8 in an atypical lesion phenotype in this study challenges existing assumptions and expands the known pathogenic spectrum of these viruses.

Given the Amazon's exceptional biodiversity and ecological distinctiveness, further studies are warranted to assess the potential presence of unique or emerging CPV genotypes. Such research could elucidate virus–host dynamics under environmental conditions distinct from urbanized or temperate zones. It may also reveal whether co-infections, environmental stressors, or host genetic variability influence viral tropism, pathogenicity, or oncogenic potential in this biome.

5. Conclusions

This study reinforces the value of integrating molecular and histopathological approaches to improve the accuracy of CPV diagnosis. Our findings expand the epidemiological landscape of CPVs by documenting the presence of CPV1 and CPV8 in dogs from the Brazilian Amazon and underscore the need for continued viral surveillance in underrepresented regions. By illuminating the genetic stability of CPV1 and detecting CPV8 in an unusual lesion phenotype, this study provides new insights into papillomavirus diversity and evolution in companion animals. Understanding these dynamics is crucial not only for veterinary virology but also for comparative oncology and One Health strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D., F.R.C.d.S., J.C.d.M.S., and H.O.M.; methodology, C.D., F.R.C.d.S., J.C.d.M.S., H.O.M., F.d.A.S., M.S.d.S., and C.W.C.; formal analysis, C.D., F.R.C.d.S., A.d.M.C.L., F.R.S., M.S.d.S., F.d.A.S., C.S.d.A., F.M.S., and C.W.C.; investigation, J.C.d.M.S., H.O.M., A.d.M.C.L., V.M.d.A.G.P., A.D.P., M.S.d.S., F.M.S., C.W.C., and P.H.G.G.; data curation, C.D., F.R.C.d.S., J.C.d.M.S., H.O.M., V.M.d.A.G.P., A.d.M.C.L., F.R.S., C.S.d.A., F.M.S., A.D.P., E.M.B.R., R.A.S., and F.R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D., F.R.C.d.S., J.C.d.M.S., H.O.M., F.d.A.S., and M.S.d.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S.d.A., F.M.S., P.H.G.G., A.D.P., E.M.B.R., R.A.S., V.M.d.A.G.P., F.R.S., and C.W.C.; supervision, C.D., and F.R.C.d.S.; project administration, C.D., F.R.C.d.S., J.C.d.M.S., and H.O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol number CEUA 23107.005499/2018-96 was approved by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) at 5th July 2018 and was approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Acre (CEUA/UFAC).

Informed Consent Statement

The authors have obtained the informed consent from the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) – Finance Code 001, the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Acre (FAPAC), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS), and the Pró-reitoria de Pesquisa da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Propesq/UFRGS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- de Villiers, E.-M.; Fauquet, C.; Broker, T.R.; Bernard, H.-U.; zur Hausen, H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 2004, 324, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.-U.; Burk, R.D.; Chen, Z.; van Doorslaer, K.; zur Hausen, H.; de Villiers, E.-M. Classification of Papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 2010, 401, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, C.E.; Zollinger, S.; Tobler, K.; Ackermann, M.; Favrot, C. Clinically healthy skin of dogs is a potential reservoir for canine papillomaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munday, J.S.; Knight, C.G.; Luff, J.A. Papillomaviral skin diseases of humans, dogs, cats and horses: A comparative review. Part 1: Papillomavirus biology and hyperplastic lesions. Vet. J. 2022, 288, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munday, J.S.; Knight, C.G.; Luff, J.A. Papillomaviral skin diseases of humans, dogs, cats and horses: A comparative review. Part 2: Pre-neoplastic and neoplastic diseases. Vet. J. 2022, 288, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.S.; Bond, S.D.; Piripi, S.; Soulsby, S.J.; Knox, M.A. Canis familiaris Papillomavirus Type 26: A Novel Papillomavirus of Dogs and the First Canine Papillomavirus within the Omegapapillomavirus Genus. Viruses 2024, 16, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.D.B.T.; Weber, M.N.; Guimarães, L.L.B.; Cibulski, S.P.; da Silva, F.R.C.; Daudt, C.; Budaszewski, R.F.; Silva, M.S.; Mayer, F.Q.; Bianchi, R.M.; et al. Canine papillomavirus type 16 associated to squamous cell carcinoma in a dog: Virological and pathological findings. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.S.; Gedye, K.; Knox, M.A.; Ravens, P.; Lin, X. Genomic Characterization of Canis familiaris Papillomavirus Type 24, a Novel Papillomavirus Associated with Extensive Pigmented Plaque Formation in a Pug Dog. Viruses 2022, 14, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, M.; Mazzei, M.; Albanese, F.; et al. Clinical, histopathological, and molecular characterization of canine pigmented viral plaques. Vet. Pathol. 2023, 60, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luff, J.; Rowland, P.; Mader, M.; Orr, C.; Yuan, H. Two Canine Papillomaviruses Associated with Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Two Related Basenji Dogs. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 1160–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, W.-T.; Haga, T.; Yamashita, N.; Lee, C.-F.; Tsuzuki, M.; Chang, H.-W. The detection and association of canine papillomavirus with benign and malignant skin lesions in dogs. Viruses 2020, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munday, J.S.; O’Connor, K.I.; Smits, B. Development of multiple pigmented viral plaques and squamous cell carcinomas in a dog infected by a novel papillomavirus. Vet. Dermatol. 2011, 22, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, O.; Antonsson, A.; Edlund, K.; Nordin, P.; Stenquist, B.; Hansson, B.G. A broad range of human papillomavirus types detected with a general PCR method suitable for analysis of cutaneous tumours and normal skin. J. Gen. Virol. 1999, 80, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, C.; da Silva, F.; Streck, A.F.; Weber, M.N.; Cibulski, S.P.; Mayer, F.Q.; Canal, C.W. How many papillomavirus species can go undetected in papilloma lesions? Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, F.R.C.; Daudt, C.; Cibulski, S.P.; Weber, M.N.; Streck, A.F.; Mayer, F.Q.; Canal, C.W. Genome characterization of a bovine papillomavirus type 5 from cattle in the Amazon region, Brazil. Virus Genes 2017, 53, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.S.; Thomson, N.A.; Luff, J.A. Papillomaviruses in dogs and cats. Vet. J. 2017, 225, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Scally, G.; Langland, J. A topical botanical therapy for the treatment of canine papilloma virus associated oral warts: A case series. Adv. Integr. Med. 2021, 8, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, E.A.F.; Chu, S.; Pearce, J.W.; Bryan, J.N.; Flesner, B.K. Papillomavirus DNA Not Detected in Canine Lobular Orbital Adenoma and Normal Conjunctival Tissue. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.E.; Zollinger, S.; Tobler, K.; Ackermann, M.; Favrot, C. Clinically Healthy Skin of Dogs Is a Potential Reservoir for Canine Papillomaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.T.; Saveria Campo, M. “Hit and Run” Transformation of Mouse C127 Cells by Bovine Papillomavirus Type 4: The Viral DNA Is Required for the Initiation but Not for Maintenance of the Transformed Phenotype. Virology 1988, 164, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, K.; Fritsche, J.; Mueller, N.; Koerschgen, B.; Dierig, B.; Strebelow, G.; et al. Detection of Canine Oral Papillomavirus DNA in Conjunctival Epithelial Hyperplastic Lesions of Three Dogs. Vet. Pathol. 2009, 46, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, C.E.; Tobler, K.; Ackermann, M.; Panakova, L.; Thoday, K.L.; Favrot, C. Three Novel Canine Papillomaviruses Support Taxonomic Clade Formation. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 2615–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, A.P.; Coyner, K.S.; Trimmer, A.M.; Tater, K.; Rishniw, M. Canine Pedal Papilloma Identification and Management: A Retrospective Series of 44 Cases. Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 32, 509–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luff, J.A.; Affolter, V.K.; Yeargan, B.; Moore, P.F. Detection of Six Novel Papillomavirus Sequences within Canine Pigmented Plaques. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2012, 24, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Alcântara, B.K.; Alfieri, A.A.; Rodrigues, W.B.; Otonel, R.A.A.; Lunardi, M.; Headley, S.A.; Alfieri, A.F. Identification of Canine Papillomavirus Type 1 (CPV1) DNA in Dogs with Cutaneous Papillomatosis. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2014, 34, 1223–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.D.R.; Oliveira, L.B.; Santos, L.A.B.O.; Soares, R.C.; Batista, M.V.A. Molecular Characterization of Canis Familiaris Oral Papillomavirus 1 Identified in Naturally Infected Dogs from Northeast Brazil. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.R.C.; Daudt, C.; Streck, A.F.; Weber, M.N.; Lima Filho, R.V.; Driemeier, D.; Canal, C.W. Genetic characterization of Amazonian bovine papillomavirus reveals the existence of four new putative types. Virus Genes 2015, 51, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, C.E.; Jennings, S.H.; Diallo, A.; Lyons, J. Canine papillomavirus types 1 and 2 in classical papillomas: High abundance, different morphological associations and frequent co-infections. Vet. J. 2019, 250, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regalado Ibarra, A.M.; Legendre, L.; Munday, J.S. Malignant transformation of a canine papillomavirus type 1-induced persistent oral papilloma in a 3-year-old dog. J. Vet. Dent. 2018, 35, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnard, G.L.; Baloyi, N.M.; Bracher, L.R.; Hitzeroth, I.I.; Rybicki, E.P. Complete genome sequences of two isolates of Canis familiaris oral papillomavirus from South Africa. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, e01006-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancak, A.; Favrot, C.; Geisseler, M.D.; Müller, M.; Lange, C.E. Antibody titres against canine papillomavirus 1 peak around clinical regression in naturally occurring oral papillomatosis. Vet. Dermatol. 2015, 26, 57–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.S.; Tucker, R.S.; Kiupel, M.; Harvey, C.J. Multiple oral carcinomas associated with a novel papillomavirus in a dog. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2015, 27, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchioratto, I.; Mucellini, C.I.; Lopes, T.R.R.; Oliveira, P.S.B.; Silva Júnior, J.V.J.; Brum, M.C.S.; Weiblen, R.; Flores, E.F. Phylogenetic analysis of papillomaviruses in dogs from southern Brazil: Molecular epidemiology and investigation of mixed infections and spillover events. Vet. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 2025–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.d.A.; Daudt, C.; Lins, A.d.M.C.; dos Santos, I.R.; Tomaya, L.Y.C.; Lima, A.d.S.; Reis, E.M.B.; Satrapa, R.A.; Driemeier, D.; Bagon, A.; et al. Characterization of Papillomatous Lesions and Genetic Diversity of Bovine Papillomavirus from the Amazon Region. Viruses 2025, 17, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram summarizing the methodology used in the study. (Top panel): Clinical sampling and histopathological evaluation of 61 dogs with papillomatous lesions, including lesion excision, classification, and histological analysis. (Bottom panel): Molecular workflow, from DNA extraction and PCR amplification to genome assembly and phylogenetic analysis.

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram summarizing the methodology used in the study. (Top panel): Clinical sampling and histopathological evaluation of 61 dogs with papillomatous lesions, including lesion excision, classification, and histological analysis. (Bottom panel): Molecular workflow, from DNA extraction and PCR amplification to genome assembly and phylogenetic analysis.

Figure 2.

Exophytic papillomatous proliferation of the epithelium in dogs sampled in the study. (a) Fibroblast proliferation in the superficial dermis (arrow), associated with hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and hypergranulosis (arrowhead) in the underlying epidermis. HE, 20x. (b) Hyperkeratosis (arrow) covering hyperplastic epidermis. HE, 10x.

Figure 2.

Exophytic papillomatous proliferation of the epithelium in dogs sampled in the study. (a) Fibroblast proliferation in the superficial dermis (arrow), associated with hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and hypergranulosis (arrowhead) in the underlying epidermis. HE, 20x. (b) Hyperkeratosis (arrow) covering hyperplastic epidermis. HE, 10x.

Figure 3.

Comparison of histopathological and molecular findings in sampled dogs (n = 61), highlighting overlaps and discrepancies between PCR results and squamous papilloma (SP) diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Comparison of histopathological and molecular findings in sampled dogs (n = 61), highlighting overlaps and discrepancies between PCR results and squamous papilloma (SP) diagnosis.

Figure 4.

Distribution of lesion morphologies among samples diagnosed as papillomatosis by PCR and/or histopathology (n = 39). Cauliflower-like lesions predominated (61.5%), followed by nodular (20.5%), filiform (10.3%), and pigmented plaques (7.7%).

Figure 4.

Distribution of lesion morphologies among samples diagnosed as papillomatosis by PCR and/or histopathology (n = 39). Cauliflower-like lesions predominated (61.5%), followed by nodular (20.5%), filiform (10.3%), and pigmented plaques (7.7%).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of partial L1 region, which reveals major clades representing different species of Canis familiaris papillomavirus types, with an outgroup of Colobus guereza papillomavirus generated using MEGA software. The sequences generated herein are bold. CPV with white framing are those not classified within species at PaVE.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of partial L1 region, which reveals major clades representing different species of Canis familiaris papillomavirus types, with an outgroup of Colobus guereza papillomavirus generated using MEGA software. The sequences generated herein are bold. CPV with white framing are those not classified within species at PaVE.

Table 1.

Complete samples data, including ID, PCR result, age (Y: year/s, M: month/s), breed, Munincipality/State, Anatomic location and macroscopy/microscopy features.

Table 1.

Complete samples data, including ID, PCR result, age (Y: year/s, M: month/s), breed, Munincipality/State, Anatomic location and macroscopy/microscopy features.

| ID |

PCR |

Age |

Sex |

Breed |

Municipality/State |

Anatomic Location |

Macroscopy |

Microscopy |

| 16AC18BR |

CPV1 |

5Y |

F |

Poodle |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Ear |

Nodular |

NA 2

|

| 20AC18BR |

CPV1 |

8Y |

F |

American Bully |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Eye |

Nodular |

SP 3

|

| 27AC18BR |

(+) 1

|

4Y |

F |

Pinscher |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Limb |

Nodular |

NA |

| 28AC18BR |

CPV8 |

4Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Limb |

Filiform |

SP |

| 30AC18BR |

CPV1 |

2Y |

F |

Pinscher |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Head |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 32AC19BR |

CPV1 |

7Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 34AC19BR |

CPV1 |

1Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 35AC19BR |

(+) |

12Y |

M |

Pitbull |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Limb |

Filiform |

NA |

| 41AC19BR |

CPV1 |

2Y |

M |

Poodle |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

NA |

| 42AC19BR |

CPV1 |

2Y |

F |

Shihtzu |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

NA |

| 43AC19BR |

CPV1 |

4Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Eye |

Cauliflower |

NA |

| 19AC18BR |

(-) |

8Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Teat |

Nodular |

SP |

| 21RO18BR |

(-) |

4 M |

M |

Labrador |

Porto Velho/Rondônia |

Oral |

Nodular |

SP |

| 22RO18BR |

(-) |

8Y |

M |

Labrador |

Porto Velho/Rondônia |

Oral |

Nodular |

ND 4

|

| 24AC18BR |

(-) |

8Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Ear |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 25AC18BR |

(-) |

3Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Abdomen |

Nodular |

SP |

| 26AC18BR |

(-) |

3Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Teat |

Nodular |

SP |

| 31AC18BR |

(-) |

10Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Teat |

Filiform |

ND |

| 01RO19BR |

(+) |

12Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Jarú/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 02RO19BR |

(-) |

8Y |

F |

Pitbull |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Neck |

Filiform |

ND |

| 03RO19BR |

(+) |

13Y |

F |

Poodle |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Back |

Pigmented Plaques |

ND |

| 04RO19BR |

(+) |

12Y |

F |

Boxer |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Limb |

Pigmented Plaques |

ND |

| 05RO19BR |

CPV1 |

8M |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ouro-Preto/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 06RO19BR |

(-) |

8M |

M |

Pitbull |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 07RO19BR |

CPV1 |

3Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 08RO19BR |

(-) |

10Y |

M |

Basset Hound |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Head |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 09RO19BR |

(-) |

10Y |

M |

Pitbull |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Limb |

Filiform |

ND |

| 10RO19BR |

(-) |

13Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Limb |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 11RO19BR |

(-) |

10Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Ear |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 12RO19BR |

CPV1 |

8Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Nova-Londrina/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 13RO19BR |

(-) |

2Y |

M |

Pitbull |

Nova-Londrina/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 14RO19BR |

(+) |

13Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 15RO19BR |

CPV1 |

13Y |

M |

Pitbull |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Chest |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 16RO19BR |

(-) |

12Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 17RO19BR |

CPV1 |

7Y |

F |

Dachshund |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Limb |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 18RO19BR |

(-) |

13Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 19RO19BR |

(-) |

12Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Eye |

Filiform |

ND |

| 20RO19BR |

(-) |

12Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Teat |

Filiform |

ND |

| 21RO19BR |

(-) |

12Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Limb |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 22RO19BR |

(-) |

MI 5

|

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Back |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 23RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Nodular |

ND |

| 24RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Eye |

Nodular |

ND |

| 25RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Limb |

Nodular |

ND |

| 26RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Abdomen |

Nodular |

ND |

| 27RO19BR |

(+) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 28RO19BR |

CPV1 |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Neck |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 30RO19BR |

CPV1 |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 31RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 32RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Chest |

Filiform |

ND |

| 33RO19BR |

(+) |

7Y |

F |

Shih Tzu |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Eye |

Nodular |

ND |

| 34RO19BR |

(-) |

MI |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Teat |

Filiform |

ND |

| 35RO19BR |

(-) |

8Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 36RO19BR |

(-) |

10Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Neck |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 39RO19BR |

(-) |

5M |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 40RO19BR |

(+) |

11Y |

F |

Poodle |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Chest |

Filiform |

ND |

| 41RO19BR |

(+) |

8Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Eye |

Filiform |

ND |

| 42RO19BR |

(-) |

9Y |

F |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Teat |

Filiform |

ND |

| 43RO19BR |

(+) |

11Y |

M |

Mixed breed |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Ear |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 44RO19BR |

(+) |

8Y |

MI |

MI |

Ji-Paraná/Rondônia |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

SP |

| 45AC19BR |

(+) |

6Y |

MI |

MI |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Oral |

Cauliflower |

ND |

| 02AC23BR |

(+) |

7Y |

F |

Pinscher |

Rio Branco/Acre |

Vulva |

Pigmented Plaques |

NA |

Table 2.

Diagnostic summary and microscopic characterization of canine skin and mucosal lesions not diagnosed as squamous papilloma.

Table 2.

Diagnostic summary and microscopic characterization of canine skin and mucosal lesions not diagnosed as squamous papilloma.

| Sample |

Diagnosis |

Histopathological description |

| 22RO18BR |

Sebaceous hyperplasia |

Sample composed of skin with sebaceous gland hyperplasia and epidermal acanthosis. |

| 24AC18BR |

Histiocytoma |

Non-encapsulated dermal neoplastic proliferation of round mesenchymal cells, with eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, moderate pleomorphism, and high mitotic activity (≈30 mitoses/10 HPF). |

| 31AC18BR |

Dermatofibrosis |

Collagen proliferation and infiltrate of mast cells and lymphocytes. |

| 02RO19BR |

Collagenous hamartoma |

Papillary exophytic nodule composed of marked disorganized collagen proliferation, covered by thin stratified keratinized squamous epithelium. |

| 09RO19BR |

Sebaceous adenoma |

Well-differentiated, non-encapsulated sebocytic proliferation in small lobules with scant collagenous stroma. Polygonal cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, round nuclei, stippled chromatin, and prominent nucleoli. Mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, no mitoses. |

| 11RO19BR |

Chronic otitis |

Epidermis with marked acanthosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. Infiltrate also involves dilated ceruminous glands with eosinophilic material and neutrophils. Moderate proliferation of fibrous connective tissue in the dermis. |

| 18RO19BR |

Melanocytoma |

Poorly defined, non-encapsulated melanocytic neoplastic proliferation with individual polygonal cells, cytoplasm containing melanin granules, and mild anisocytosis. No mitoses. Numerous freezing artifacts. |

| 19RO19BR |

Melanocytoma |

Poorly defined, non-encapsulated melanocytic neoplastic proliferation of polygonal cells with melanin granules often obscuring the nuclei. Nuclei are round to oval with finely stippled chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, no mitotic figures. |

| 20RO19BR |

Melanocytoma |

Poorly defined, non-encapsulated melanocytic neoplastic proliferation of polygonal cells with melanin granules often obscuring the nuclei. Nuclei are round to oval, finely stippled chromatin, prominent nucleoli. Mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, no mitoses observed. |

| 21RO19BR |

Inconclusive |

Moderate multifocal epidermal acanthosis associated with moderate orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. |

| 22RO19BR |

No significant histopathological lesions |

Mild multifocal orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. |

| 23RO19BR |

No significant histopathological lesions |

Mild multifocal orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. |

| 24RO19BR |

Melanocytoma |

Poorly defined, non-encapsulated melanocytic proliferation of individual polygonal cells with cytoplasm containing melanin. Round to oval nuclei with stippled chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, no mitoses. Moderate inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. |

| 25RO19BR |

Sebaceous adenoma |

Well-differentiated, non-encapsulated sebocytic proliferation in small lobules with scant stroma. Polygonal cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, round nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, no mitoses. Epidermis with moderate acanthosis. |

| 26RO19BR |

Inconclusive |

Deep dermis with focal extensive area of dilated blood vessels filled with erythrocytes, surrounded by moderate inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. |

| 31RO19BR |

Chronic-active ulcerative stomatitis |

Submucosa with marked inflammatory infiltrate (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages), associated with fibrovascular proliferation and fibrin deposition. Mucosa shows multifocal ulceration with neutrophilic infiltrate, bacterial aggregates, and fibrin. Remaining epithelium is moderately hyperplastic with digitiform projections into the submucosa. |

| 32RO19BR |

Trichoblastoma |

Moderately defined epithelial neoplastic proliferation in superficial dermis, with polygonal cells in trabeculae over abundant fibrocollagenous stroma. Oval to elongated nuclei, stippled chromatin, prominent nucleoli, mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and 25 mitoses in 2.37 mm². Mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in underlying dermis. |

| 34RO19BR |

No significant histopathological lesions |

Mild multifocal orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. |

| 35RO19BR |

No significant histopathological lesions |

Mild multifocal orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. In the dermis around skin adnexa, mild infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. |

| 36RO19BR |

No significant histopathological lesions |

Marked diffuse orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis associated with mild epithelial acanthosis. |

| 39RO19BR |

No significant histopathological lesions |

Mild infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages, along with mild fibrosis. |

| 42RO19BR |

Melanoma |

Poorly defined melanocytic neoplastic proliferation in dermis, with polygonal cells containing melanin that obscures nuclei. Nuclei are round to oval, with moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and 20 mitoses. Moderate inflammatory infiltrate present. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).