Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overparenting and Offspring’s Mental Health

1.2. Potential Moderators of Associations Between Overparenting and Mental Health

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

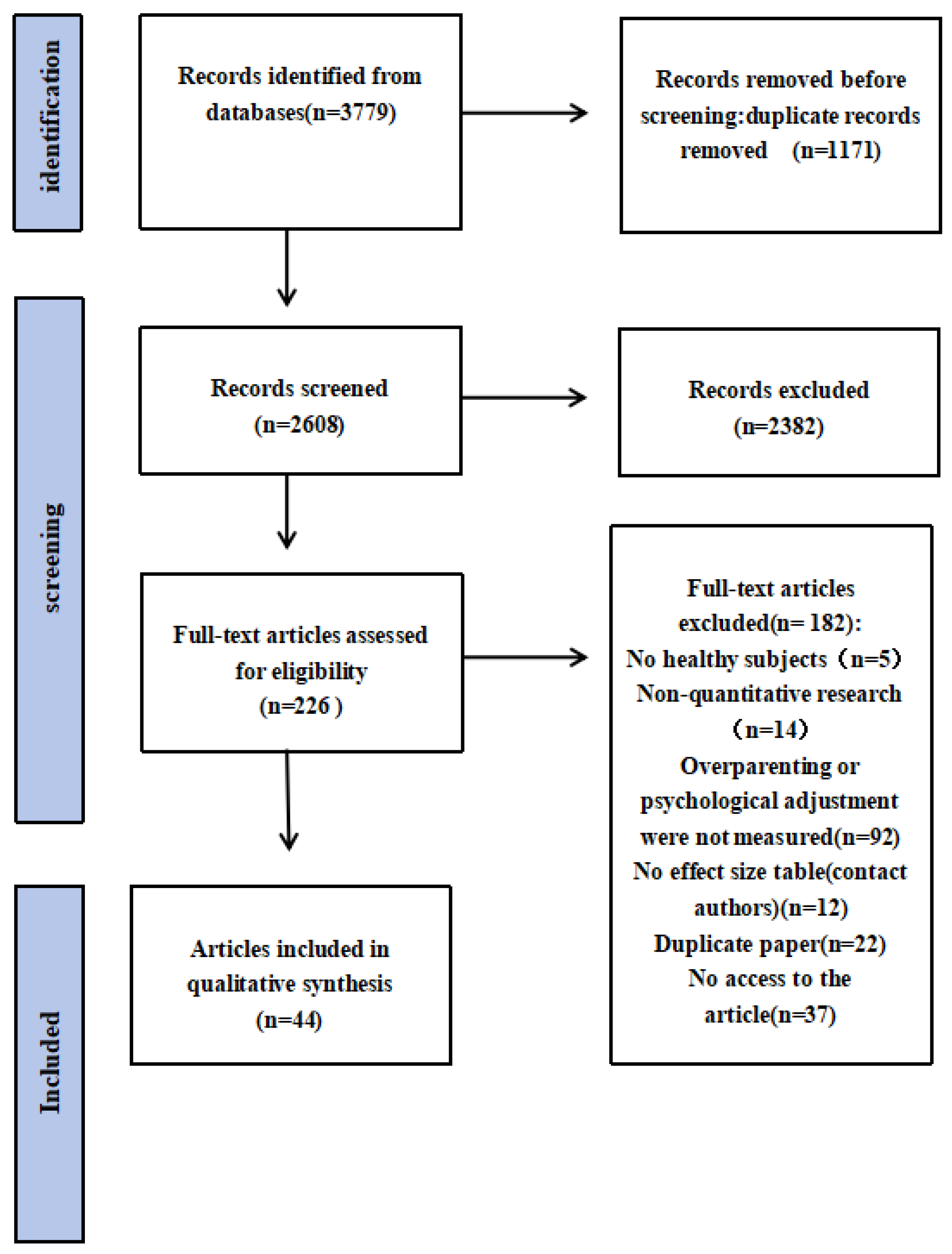

2.1. Search Procedure and Selection Steps

2.2. Coding of the Studies

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Meta-Analysis of Overparenting and Indicators of Mental Health

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations Between Overparenting and Mental Health

4.2. Moderators of Associations Between Overparenting and Mental Health

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Ahmed, F.L.; Mingay, D. (2023). Relationship between helicopter parenting and psychological wellbeing in college students. International Journal of Social Research & Innovation, 7(1), 73. [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [CrossRef]

- *Borges, D.; Portugal, A.; Magalhães, E.; Sotero, L.; Lamela, D.; Prioste, A. (2019). Helicopter Parenting Instrument: Estudos Psicométricos Iniciais com Adultos Emergentes. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagncstico y Evaluacicn Psicolcgica. 53: 33–48. [CrossRef]

- *Cardoso Garcia, R.; Pedroso de Lima, M.; Carona, C. (2022). The Relation Between Helicopter Parenting and Satisfaction with Life in Emerging Adults Living with Their Parents: The Moderating Role of Gender and Age Group. Central European Journal of Paediatrics. 18(2): 150–160. [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N.; Gartrell, N.K.; Rothblum, E.D.; Koh, A.S.; Bos, H.M.W. (2022). Helicopter parenting, emotional avoidant coping, mental health, and homophobic stigmatization among emerging adult offspring of lesbian parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 36(7):1205–1215. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.S.S.; Pomerantz, E.M. (2015). Value development underlies the benefits of parents’ involvement in children’s learning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 309. [CrossRef]

- *Chen, Y.W. (2022). Effects of parental education anxiety on adolescents’ mental health: evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Unpublished master’s thesis). Jiangxi Normal University.

- *Cook, E.C. (2020). Understanding the Associations between Helicopter Parenting and Emerging Adults’ Adjustment. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 29(7):1899–1913. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Allen, J.W.; Fincham, F.D.; May, R.W.; Love, H. (2019). Helicopter Parenting, Self-regulatory Processes, and Alcohol Use among Female College Students. Journal of Adult Development, 26(2), 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Hong, P.; Jiao, C. (2022). Overparenting and emerging adult development: A systematic review. Emerging Adulthood. 10(5):1076–1094. [CrossRef]

- *Darlow, V.; Norvilitis, J.; Schuetze, P. (2017). The Relationship between Helicopter Parenting and Adjustment to College. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 26(8): 2291–2298. [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Karl, K.A. (2022). Is helicopter parenting stifling moral courage and promoting moral disengagement? Implications for the training and development of millennial managers. Management Research Review, 45(5), 700–714. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castilla, B.; Declercq, L.; Jamshidi, L.; Beretvas, S.N.; Onghena, P.; Van den Noortgate, W. (2021). Detecting selection bias in meta-analyses with multiple outcomes: A simulation study. Journal of Experimental Education, 89(1), 125–144. [CrossRef]

- *Flower, A.T. (2021). The effects of helicopter parenting in emerging adulthood: An investigation of the roles of involvement and perceived intrusiveness. Honors Theses. 315.

- Filippello, P.; Harrington, N.; Costa, S.; Buzzai, C.; Sorrenti, L. (2018). Perceived parental psychological control and school learned helplessness: The role of frustration intolerance as a mediator factor. School Psychology International, 39(4), 360–377. [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, K.L.; Cheng, Y.; Wesselmann, E.D.; Zarit, S.; Furstenberg, F.; Birditt, K.S. (2012). Helicopter Parents and landing pad Kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(4), 880–896. [CrossRef]

- *Gao, W.; Hou, Y.; Hao, S.; Yu, A. (2023). Helicopter Parenting and Emotional Problems in Chinese Emerging Adults: Are There Cross-lagged Effects and the Mediations of Autonomy? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 52(2):393-405. [CrossRef]

- Grotevant, H.D.; Cooper, C.R. (1986). Individuation in family relationships: A perspective on individual differences in the development of identity and role-taking skill in adolescence. Human Development. 29(2), 82–100. [CrossRef]

- Greenspoon, P.J.; Saklofske, D.H. (2001). Toward an Integration of Subjective Well-Being and Psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54(1), 81–108. [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Vevea, J.L. (1998). Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 486–504. [CrossRef]

- Hong, P. (2021). A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Overparenting and Emerging Adults’ Well-Being (Doctoral dissertation). The Florida State University. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/cross-cultural-perspective-on-overparenting/docview/2546939390/se-2.

- *Hong, P.; Cui, M. (2020). Helicopter parenting and college students’ psychological maladjustment: The role of self-control and living arrangement. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 29: 338-347. [CrossRef]

- * Hong, P.; CuiM. (2023). Overparenting and psychological well-being of emerging adult children in the United States and China. Family Relations. 72(5): 2852-2868. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.H.; Doh, H.S. (2018). Effects of helicopter parenting on depression in female emerging adults: Examining the mediating role of adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 39(6), 143–158. [CrossRef]

- * Howard, A.L.; Alexander, S.M.; Dunn, L.C. (2022). Helicopter Parenting is Unrelated to Student Success and Well-Being: A Latent profile analysis of perceived parenting and academic motivation during the transition to university. Emerging Adulthood, 10(1), 197–211. [CrossRef]

- *Jiao, J. (2022). I came through you and belong not to you: Overparenting, attachment, autonomy, and mental health in emerging adulthood (Doctoral dissertation). The University of Arizona. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/openview/c6a265b46e9066847621d3a010c3d5bc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- *Jiao, J.; Segrin, C. (2021). Parent–Emerging-Adult-Child Attachment and Overparenting. Family Relations. 70(3):859–865. [CrossRef]

- *Jiao, J.; Segrin, C. (2023). Moderating the Association Between Overparenting and Mental Health: Open Family Communication and Emerging Adult Children’s Trait Autonomy. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 32(3):652–662. [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Hwang, W.; Kim, S.; Sin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. (2019). Relationships among helicopter parenting, self-efficacy, and academic outcome in American and South Korean college students. Journal of Family Issues. 40(18):2849–2870. [CrossRef]

- *Jung, E.; Hwang, W.; Kim, S.; Sin, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Park, J.H. (2020). Helicopter parenting, autonomy support, and student wellbeing in the United States and South Korea. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 29:358-373. [CrossRef]

- *Kouros, C.; Pruitt, M.; Ekas, N.; Kiriaki, R.; Sunderland, M. (2017). Helicopter Parenting, Autonomy Support, and College Students’ Mental Health and Well-being: The Moderating Role of Sex and Ethnicity. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 26(3):939–949. [CrossRef]

- *Kwon, K.-A.; Yoo, G.; Bingham, G. (2016). Helicopter Parenting in Emerging Adulthood: Support or Barrier for Korean College Students’ Mental health? Journal of Child & Family Studies. 25(1):136–145. [CrossRef]

- *Lee, J.; Kang, S. (2018). Perceived Helicopter Parenting and Korean Emerging Adults’ Mental Health: The Mediational Role of Parent-Child Affection and Pressure from Parental Career Expectations. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 27(11):3672–3686. [CrossRef]

- LeMoyne, T.; Buchanan, T. (2011). Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum. 31(4):399–418. [CrossRef]

- *Leung, J.T. (2020). Too much of a good thing: Perceived overparenting and wellbeing of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Indicators Research. 13(5):1791-1809. [CrossRef]

- *Leung, J.T.Y. (2021). Overparenting, parent-child conflict and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: A cross-lagged panel study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18(22):11887. [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.; Shek, D.T. (2024). Overparenting and psychological wellbeing among Chinese adolescents: Findings based on latent growth modeling. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 34(3), 871-883. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kim, S. (2025). The differential impact of neglectful and Intrusive parenting behavior on adolescents’ relationships with peers and Teachers using longitudinal data: Mediating effects of depression and social withdrawal. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 56(2), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- *Love, H.N. (2020). Overparenting: Measurement, Profiles, and Associations with Emerging Adults’ Mental Health (Doctoral dissertation). The Florida State University. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/openview/97392e1856150f29f1d95230092a40e2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- *Love, H.; Cui, M.; Allen, J.W.; Fincham, F.D.; May, R.W. (2020). Helicopter parenting and female university students’ anxiety: does parents’ gender matter? Families, Relationships and Societies, 9(3), 417-430. [CrossRef]

- *Min-Hwa Hong & Hyun-Sim Doh. (2018). Effects of helicopter parenting on depression in female emerging adults: Examining the mediating role of adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. Korean Journal of Child Studies. 39(6):143-158. [CrossRef]

- *Moilanen, K.L.; Lynn Manuel, M. (2019). Helicopter parenting and adjustment outcomes in young adulthood: A consideration of the mediating roles of mastery and self-regulation. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 28(8):2145–2158. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Nelson, L.J. (2012). Black hawk down?: Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence. 35(5):1177–1190. [CrossRef]

- *Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Son, D.; Nelson, L.J. (2021). Profiles of helicopter parenting, parental warmth, and psychological control during emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. 9(2): 132–144. [CrossRef]

- Patock-Peckham, J.A.; Morgan-Lopez, A.A. (2009). The gender specific mediational pathways between parenting styles, neuroticism, pathological reasons for drinking, and alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 34(3):312–315. [CrossRef]

- *Pautler Lindsey, R. (2017). Helicopter Parenting of College Students (Masters Theses). Eastern Illinois University. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2749.

- *Perez, C.M. (2019). Overparenting, Emotional Distress, and Subjective Well-Being: Facets of Emotional Distress Tolerance as Mediators (Doctoral dissertation). Southern Mississippi University. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1608.

- *Perez, C.M.; Nicholson, B.C.; Dahlen, E.R.; Leuty, M.E. (2020). Overparenting and emerging adults’ mental health: The mediating role of emotional distress tolerance. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 29(2):374–381. [CrossRef]

- *Pistella, J.; Izzo, F.; Isolani, S.; Ioverno, S.; Baiocco, R. (2020). Helicopter mothers and helicopter fathers: Italian adaptation and validation of the Helicopter Parenting Instrument. Psychology Hub. 37(1):37-46. [CrossRef]

- *Ratcliff, M.A. (2020). Validation of helicopter parenting: An examination of measures and psychological outcomes (Doctoral dissertation). University of La Verne. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/validation-helicopter-parenting-examination/docview/2447265316/se-2.

- *Reed, K.; Duncan, J.M.; Lucier-Greer, M.; Fixelle, C.; Ferraro, A.J. (2016). Helicopter parenting and emerging adult self-efficacy: Implications for mental and physical health. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 25:3136-3149. [CrossRef]

- *Rote, W.M.; Olmo, M.; Feliscar, L.; Jambon, M.M.; Ball, C.L.; Smetana, J.G. (2020). Helicopter parenting and perceived overcontrol by emerging adults: A family-level profile analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 29:3153-3168. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Scharf, M. (2015). “I will guide you” The indirect link between overparenting and young adults’ adjustment. Psychiatry research, 228(3), 826–834. [CrossRef]

- Schulzke, S. (2021). Assessment of Publication Bias. In: Patole, S. (eds) Principles and Practice of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- *Schiffrin, H.H.; Erchull, M.J.; Sendrick, E.; Yost, J.C.; Power, V.; Saldanha, E.R. (2019). The effects of maternal and paternal helicopter parenting on the self-determination and well-being of emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 28: 3346-3359. [CrossRef]

- *Schiffrin, H.H.; Liss, M.; Miles-McLean, H.; Geary, K.A.; Erchull, M.J.; Tashner, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family studies, 23, 548-557. [CrossRef]

- *Segrin, C.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J. (2022). Indirect Effects of Overparenting and Family Communication Patterns on Mental Health of Emerging Adults in China and the United States. Journal of Adult Development. 29(3):205–217. [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C.; Woszidlo, A.; Givertz, M.; Bauer, A.; Murphy, M.T. (2012). The association between overparenting, Parent-Child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Family Relations, 61(2), 237–252. [CrossRef]

- *Segrin, C.; Woszidlo, A.; Givertz, M.; Montgomery, N. (2013). Parent and Child Traits Associated with Overparenting. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(6), 569–595. [CrossRef]

- *Seki, T.; Haktanir, A.; Şimşir Gökalp, Z. (2023). The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between helicopter parenting and several indicators of mental health among emerging adults. Journal of Community Psychology. 51(3):1394-1407. [CrossRef]

- * Stout, A.E. (2023). Exploring the Associations Between Helicopter Parenting and First-Year College Student’s Mental Health and Academic Outcomes (Master’s thesis, The Ohio State University). OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1681893433671612.

- Szwedo, D.E.; Hessel, E.T.; Loeb, E.L.; Hafen, C.A.; Allen, J.P. (2017). Adolescent support seeking as a path to adult functional independence. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 949. [CrossRef]

- Urone, C.; Verdi, C.; Iacono, C.L.; Miano, P. (2024). Dealing with Overparenting: Developmental Outcomes in Emerging Adults Exposed to Overprotection and Overcontrol. Trends in Psychology, 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Vigdal, J.S.; Brønnick, K.K. (2022). A systematic review of helicopter parenting and its relationship with anxiety and depression. Frontiers in Psychology. 13: 872-981. [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, M.L.; Scorza, P.; Shultz, J.M.; Helpman, L.; Mootz, J.J.; Johnson, K.A.;... & Arbuckle, M.R. (2017). Challenges and opportunities in global mental health: a research-to-practice perspective. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19, 1-10.

- *Wang, J.; Lai, R.; Yang, A.; Yang, M.; Guo, Y. (2021). Helicopter parenting and depressive level among non-clinical Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders. 295:522–529. [CrossRef]

- *Wang, X.Y.; Liu, S.H.; Wu, X.C. (2023). The relationship between adolescent depression and parental over-education, parent-child conflict and developmental differences. Applied Psychology. (01):71-79. [CrossRef]

- *Wenze, S.J.; Pohoryles, A.B.; DeCicco, J.M. (2019). Helicopter Parenting and Emotion Regulation in US College Students. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research. 24(4):274–283. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO manual on sugar-sweetened beverage taxation policies to promote healthy diets. World Health Organization.

- Zhang, Q.; Ji, W. (2023). Overparenting and offspring depression, anxiety, and internalizing symptoms: A meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 36(3), 1307–1322. [CrossRef]

- *Zienty, L.; Nordling, D.J. (2018). Fathers are helping, mothers are hovering: Differential effects of helicopter parenting in college first-year students. Celebration of Learning. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/celebrationoflearning/2018/posters/19.

| First author and year | N | Country | Cultures | Design | Parental gender | Percent of female | Age group | Average age of offspring |

Informants |

| Ahmed (2023) | 71 | Maldives | NW | C | Both | 70% | adult | N/A | offspring |

| Borges (2019) | 187 | Portugal | N-A W | C | Both | 64.70% | adult | 21.20 | offspring |

| Carone (2022) | 76 | USA | W | L | Mother | 48.68% | adult | 25 | offspring |

| Chen (2022) | 623 | China | NW | C | Both | 45.75% | adolescent | 16.04 | Both |

| Cook (2020) | 637 | USA | W | C | Both | 67% | adult | 20.03 | offspring |

| Darlow (2017) | 294 | USA | W | C | Both | 81.97% | adult | 20.54 | offspring |

| Flower (2021) | 194 | USA | W | C | Both | 64.95% | adult | N/A | offspring |

| Gao (2023) | 418 | China | NW | L | Both | 80.1% | adult | 18.71 | offspring |

| Garcia (2022) | 173 | Portugal | N-A W | C | Both | 69.40% | adult | 23.08 | offspring |

| Hong (2018) | 305 | Korea | NW | C | Both | 100% | adult | 21.94 | offspring |

| Hong (2020) | 432 | USA | W | C | Both | 89.60% | adult | 20.21 | offspring |

| Hong (2023) | 414; 612 | USA; China | W; NW | C | Both | 92%; 69% | adult | 20.38; 20.21 | offspring |

| Howard (2022) | 460 | Canada | N-A W | C | Both | 43.91% | adult | 18.33 | offspring |

| Jiao (2021) | 213 pairs | USA | W | C | Both | 65.80% | adult | 20.63 | Both |

| Jiao (2022) | 412 | USA | W | L | Both | 60.40% | adult | 24.3 | Both |

| Jiao (2023) | 442 | USA | W | C | Both | 68.10% | adult | 20.28 | offspring |

| Jung (2020) | 215;171 | USA; Korea | W; NW | C | Mother | N/A | adult | 19.61; 21.95 | offspring |

| Kouros (2017) | 118 | USA | W | C | Both | 83.10% | adult | 19.82 | offspring |

| Kwon (2016) | 412 | USA | W | C | Both | 50.70% | adult | 21.28 | offspring |

| Lee (2018) | 562 | Korea | NW | C | Both | 47.86% | adult | 24.88 | offspring |

| Leung (2020) | 1735 | China | NW | C | Both | 47.40% | child | 12.63 | offspring |

| Leung (2021) | 1074 | China | NW | L | Both | 46.80% | adolescent | 12.66 | offspring |

| Love (2020) | 473 | USA | W | C | Both | N/A | adult | 19.78 | offspring |

| Love (2020) | 539 | USA | W | C | Both | 92.50% | adult | 20.18 | offspring |

| Moilanen (2019) | 302 | USA | W | C | Both | 64.90% | adult | 21.57 | offspring |

| Padilla-Walker (2021) | 458 | USA | W | L | Both | 51% | adult | 19 | offspring |

| Pautler (2017) | 87 | USA | W | C | Mother | 63% | adult | N/A | offspring |

| Perez (2019) | 313 | USA | W | C | Both | 82.40% | adult | 19.55 | Both |

| Perez (2020) | 360 | USA | W | C | Both | 83.60% | adult | 19.93 | offspring |

| Pistella (2020) | 602 | Italian | N-A W | C | Both | 59% | adolescent | 16.59 | offspring |

| Ratcliff (2020) | 158 | USA | W | C | Mother | 74.7% | adult | 20.28 | offspring |

| Reed (2016) | 461 | USA | W | C | Mother | 80.80% | adult | 19.66 | offspring |

| Rote (2020) | 282 | USA | W | C | Both | 71% | adult | 19.87 | offspring |

| Schiffrin (2014) | 297 | USA | W | C | Mother | 88% | adult | 19.34 | offspring |

| Schiffrin (2019) | 446 | USA | W | C | Both | 73.10% | adult | 19.59 | offspring |

| Segrin (2013) | 653 pairs | USA | W | C | Both | 81% | adult | 20.03 | Both |

| Segrin (2022) | 282;281 | USA; China | W; NW | C | Both | 62.1%;71.9% | adult | 20.67;19.83 | offspring |

| Seki (2023) | 402 | Turkey | NW | C | Both | 82.10% | adult | 21.31 | offspring |

| Stout (2023) | 120 | USA | W | C | Both | 59.20% | adult | N/A | offspring |

| Wang (2021) | 648 | China | NW | C | Both | 50.30% | adult | 21 | offspring |

| Wang (2023) | 2041 | China | NW | C | Both | 52.60% | adolescent | 14.11±2.42 | offspring |

| Wenze (2019) | 104 | USA | W | C | Mother | 77.88% | adult | 19.15 | offspring |

| Zienty (2018) | 156 | USA | W | C | Both | 71.15% | adult | N/A | offspring |

| Relationships | k | r | Heterogeneity Test | Publication Bias Test | |||||

| N | Q | df | I2 | Egger’s intercept | SE | 95%CI | |||

| depression | 65 | 31855 | 0.20 | 768.78 ** | 64 | 91.67% | -0.12 | 1.42 | [-2.97, 2.72] |

| anxiety | 34 | 37872 | 0.16 | 719.05** | 63 | 91.24% | 3.80 | 1.24 | [1.31, 6.28] |

| life satisfaction | 13 | 17293 | 0.09 | 315.83** | 35 | 90.05% | -5.03 | 2.98 | [-11.08, 1.02] |

| subjective well-being | 3 | 1687 | -.01 | 13.36 | 3 | 77.54% | -5.59 | 0.49 | [-7.68, -3.49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).