1. Introduction

In contemporary Western societies, a significant surge in narcissistic tendencies has been observed, a phenomenon often dubbed the “narcissism epidemic” [

1]. This escalation is evidenced by empirical data revealing a stark increase in self-centric attitudes, particularly among adolescents. For instance, the endorsement rate for statements such as “I am an important person” rose from 12% in 1963 to 77-80% in 1992 [

1]. This trend permeates various aspects of culture, including the lyrical content of contemporary songs and the thematic focus of popular television shows, which increasingly prioritize individual fame and self-promotion [

1].

Jean Twenge and her team investigated the observed increase in narcissistic tendencies by examining generational changes. The study, carried out in 2008, analyzed 85 cohorts of participants who completed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) scale between 1979 and 2006. The results revealed a 30% increase in narcissism levels among US university students during this period [

2]. If this trajectory continues, as many scholars speculate, the path toward heightened narcissism appears inevitable [

2].

The rise in narcissism prevalence underscores the importance of understanding its origins, namely whether influenced by parenting education. Such understanding can inform treatment adaptations and potentially shift paradigms.

The main objective of this work is to verify whether there is a correlation between parental education and the development of narcissistic traits. Hence, this work includes a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Section 2 provides a brief introduction to the topics addressed, covering the concept of narcissism, its types and scales, and the various forms of parenting considered. The subsequent section discusses the study methodology that follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Section 4 presents the results, followed by a discussion in

Section 5 and a conclusion in

Section 6.

2. Understanding Narcissism: From Personality Traits to Parenting Influences

This section presents a broad review of the literature on Narcissistic Personality Disorder, with a focus on its two main forms: grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. In addition, the section examines the assorted scales used to assess narcissistic traits, as well as the connections between narcissism and parental education.

2.1. Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Speaking of narcissism almost automatically brings us to Narcissus, a figure from Greek mythology known for falling in love with his own reflection in a pond, which ultimately led to his death. The etymology of the word possibly derives from the Greek

(narke), meaning “sleep, numbness”. The concept was taken up and refined by psychodynamic theorists, who considered that narcissism functioned as a self-regulatory mechanism as well as a personality disposition (as Jauk and Kanske cited, [

3]). In the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), it was included for the first time as a personality disorder being defined by the American Psychiatric Association as “a pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts” [

4].

Individuals with Narcissistic Personality Disorder are highly sensitive to criticism or defeat due to their fragile self-esteem. Even though they may not display it outwardly, criticism can affect them deeply, leaving them feeling humiliated, empty, and degraded. Their reactions may range from disdain and rage to defiant counterattacks. These experiences often result in social withdrawal or a façade of humility, concealing their underlying grandiosity. Their interpersonal relationships suffer significantly due to entitlement issues, a constant need for admiration, and a lack of consideration for others’ feelings [

4].

Beneath their superficially smooth and socially adaptive behavior lies deep-seated dysfunction in their internal relations with others. They often oscillate between intense ambitions, grandiose fantasies, and feelings of inferiority, relying heavily on external validation to maintain their self-worth. Despite an outward display of confidence and success, they are plagued by chronic feelings of boredom, emptiness, and dissatisfaction with life. Their constant search for admiration and gratification stems from deep-rooted desires for brilliance, wealth, power, and beauty, often paired with an inability to genuinely love or empathize with others [

5].

These individuals struggle with a lack of empathetic understanding, exhibiting exploitative and even ruthless behavior, driven by conscious or unconscious envy. Their persistent dissatisfaction, combined with their envy of others, can result in heightened defenses and further isolation. Although their ambition and confidence may lead to temporary successes, their inability to handle criticism and defeat often undermines their performance, leading to low vocational functioning, depression, and social withdrawal. Periods of grandiosity may be interspersed with hypomanic moods, adding to the instability of their emotional and professional lives [

4,

5].

2.1.1. Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism

As mentioned by Jauk and Kanske [

3], emerging consensus suggests that narcissism is multifaceted, with distinct expressions. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism are recognized as separate yet related manifestations, characterized by either self-assured dominance or self-conscious withdrawal. Despite differences, both entail feelings of self-importance and entitlement.

Narcissism is a multidimensional construct, with grandiose and vulnerable forms distinguished by persistent feelings of importance and grandiosity, alongside a desire for admiration and antagonistic traits. Although the term “narcissism” commonly evokes notions of exaggerated self-worth, superiority, entitlement, and arrogance, this definition closely aligns with the definition of grandiose narcissism. This personality trait encompasses entitlement, extroversion, socially dominant behavior, self-assurance, immodesty, exhibitionism, manipulation, and aggression. While vulnerable narcissism is associated with distrustful, hostile interpersonal styles driven by negative emotionality and problematic attachment that tends towards depressive symptoms and social withdrawal, with less emphasis on grandiose fantasies. Pathological grandiose or vulnerable narcissism may be diagnosed when these traits are pronounced. Both overlap in their use of antagonistic interpersonal strategies but differ in specific traits and behavioral tendencies [

3,

6,

7,

8].

2.1.2. Narcissism Scales

With the advancement of studies on narcissism, methods for assessing personality also emerged. The first known assessments were developed by Raskin and Hall, consisting of versions with 80 and 54 items, respectively. The shorter version,

Narcissistic Personality Inventory-40 (NPI-40), was subjected to three different studies by the same authors in 1988, and it is the version that is most used and examined in many studies to date [

9]. However, short versions were perceived after NPI-40, such as NPI-16 and NPI-34.

The NPI-40 is composed of three subscales, each capturing different facets of narcissism:

Entitlement/Exploitativeness: This subscale is often considered the most indicative of narcissistic personality pathology. It is related to lower self-esteem and extraversion, higher mood variability, and neuroticism. Additionally, it is associated with both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, as well as narcissistic personality disorder [

10].

Leadership/Authority: This subscale is a more specific marker of grandiose narcissism, associated with higher self-esteem, extraversion, and lower neuroticism. It indicates a tendency to seek and enjoy positions of leadership and authority [

10].

Grandiose Exhibitionism: Like the Leadership/Authority subscale, this is also a marker of grandiose narcissism. It is associated with higher self-esteem, extraversion, and lower neuroticism. It reflects the need to be the center of attention and to receive admiration from others [

10].

Several assessments are commonly used to measure narcissistic personality traits in psychological research. Alongside the widely recognized NPI-40, the

Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI), developed by Pincus et al. in 2009, is a 52-item self-report measure that assesses both vulnerable and grandiose narcissism traits. The PNI is divided into four subscales for vulnerable narcissism (Contingent Self-Esteem, Hiding the Self, Devaluing, and Entitlement Rage) and three subscales for grandiose narcissism (Self-Sacrificing Self-Enhancement, Grandiose Fantasies, and Exploitativeness) [

10].

The

Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS), created by Hendin and Cheek in 1997, is a 10-item self-report measure specifically designed to assess vulnerable narcissism [

10].

The

California Adult Q-Sort (CAQ) is a set of statements used in observer and self-report assessments of personality. It comprises 100 items that have been utilized to assess various personality traits, including narcissism. The CAQ-13 is a measure of narcissism-based CAQ, which consists of 13 items selected to represent it. These items were identified by experts and subjected to factor analysis, resulting in three subscales: Grandiose, Vulnerable, and Autonomy [

11,

12].

The

Childhood Narcissism Scale (CNS) is a unidimensional measure consisting of 10 items designed to assess narcissistic traits in children. The scale evaluates the degree to which children endorse grandiose and entitled self-perceptions [

13,

14,

15].

The

Dark Triad Dirty Dozen Scale (DTDD) is a 12-item measure used to assess the Dark Triad traits: narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Each of these three dimensions is evaluated with four specific items [

16,

17,

18].

The

DSM-IV Assessment of Personality Disorders Questionnaire (ADP-IV) is a self-report instrument comprising 94 items, representing the 80 criteria of the 10 DSM-IV personality disorders and the 14 research criteria of the depressive and passive-aggressive personality disorders [

19].

The

Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory – Short Form (FFNI-SF) is a 60-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess narcissism through the lens of the five-factor model (FFM) of personality. The FFNI-SF assesses both vulnerable and grandiose narcissism across 15 subscales, each representing a maladaptive variant of an FFM trait. Additionally, it considers three dimensions derived from factor analysis: antagonism, neuroticism, and agentic extraversion [

20].

The

Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire (NPQ) developed by Zhou et al. in 2009 is a 34-item self-report instrument that assesses three dimensions: desire for power, sense of superiority, and self-appreciation [

21].

The

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire – 4th Edition Plus (PDQ-4+) is the most recent version of the PDQ. Each version corresponds to the different editions of the DSM since 1980. The PDQ-4+ consists of 99-item true/false questions and assesses ten DSM-IV-TR personality disorders and two provisional personality disorders [

22,

23,

24].

The

Short Dark Triad (SD3) and the

Short Dark Tetrad (SD4) are 27-item and 28-item, respectively, self-report questionnaires designed to measure individuals’ dark personality traits. The SD4 addresses all four dark personality traits (subclinical narcissism, machiavellianism, subclinical psychopathy, and sadism), whereas the SD3 focuses on only the first three [

25,

26,

27,

28].

The

Single Item Narcissism Scale (SINS) is an one-item measure that assesses grandiose and vulnerable aspects of non-clinical narcissism. Participants respond on a seven-point scale (1 = “Not very true of me” to 7 = “Very true of me”): “To what extent do you agree with this statement: I am a narcissist. (Note: The word “narcissist” means egotistical, self-focused, and vain.).” [

29,

30]

The

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID) is a widely used semi-structured interview designed to diagnose personality disorders according to DSM-IV criteria. It includes 94 main yes/no questions that address enduring patterns of inner experience and behavior deviating from cultural expectations, affecting cognition, affectivity, interpersonal functioning, and impulse control [

31,

32].

The

Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form (YSQ-SF) is a 75-item adaptation of the original 205-item Young Schema Questionnaire. The short form includes 5 items from each of the 15 original scales, selected based on their strong factor loadings. The 15 subscales assess various schemas, such as abandonment, mistrust/abuse, and emotional deprivation. In the study under analysis, narcissism was specifically assessed using the 5-item grandiosity subscale from the YSQ-SF, which measures beliefs of superiority and entitlement to special treatment [

33,

34].

2.2. Narcissism and Parental Education

Parenting education is widely recognized as an influential factor in the development of a child’s personality traits. As mentioned by Imamoglu and Batigun [

35], and Kernberg [

5], overly permissive, intrusive, cold, or strict parenting styles — particularly when parents appear functional but are emotionally indifferent or subtly aggressive — can play a significant role in the development of narcissistic traits, including pathological narcissism. Similarly, Young et al. [

36] propose that childhood experiences such as loneliness, poor boundaries, manipulation, and conditional approval contribute to the development of a narcissistic personality, often resulting in a lack of genuine love and empathy in these individuals during their early years.

In the investigation of the impact of parental education on child development, Baumrind [

37] identified four parenting styles, each offering a perspective on the socialization processes that shape children’s personalities. These parenting styles, among the most widely accepted by scholars, are authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and neglectful styles.

Authoritarian parenting is characterized by shaping and controlling the child’s behavior according to strict standards, emphasizing obedience without explanation, and often relying on punitive measures to enforce compliance [

11]. This approach can restrain the child’s development of personal competence, as it discourages the recognition and expression of their thoughts and feelings, leading to a reliance on external approval to maintain a constructed self-image [

38,

39]. Children raised in authoritarian households may exhibit higher levels of aggression, struggle with decision-making, and have poor self-esteem due to the lack of nurturing and flexibility from their parents. Additionally, strict rules can lead to rebellion or an inflated sense of self-importance if the child is praised for compliance. However, this sense of specialness is fragile, as it depends on the continued admiration of others [

11,

40].

In contrast,

authoritative parenting sets clear behavioral standards but uses reasoning and explanation to guide the child, balancing assertiveness with respect for the child’s perspective and rights. Discipline in this style is more supportive than punitive [

11]. This approach is responsive to the child’s needs, fostering autonomy, competent skill-building, and self-regulation [

41,

42]. By maintaining clear expectations and simultaneously respecting the child’s individuality, authoritative parenting promotes a strong sense of self-confidence and self-esteem, reducing the likelihood of narcissistic traits developing [

11].

Permissive parenting is characterized by leniency and affection, often struggling to enforce discipline and not requiring the child to display mature behavior [

11]. While this approach meets the child’s needs and affirms their worth, it can foster impulsivity, selfishness, and a lack of self-regulation. Although children raised by permissive parents may develop some level of self-esteem and social skills, they often become demanding and expect their needs to be met without effort. This lack of boundaries may result in compensatory behaviors, where the child inflates their self-image and ignores others who do not satisfy their desires, behaviors commonly associated with narcissism [

40,

41,

43].

On the other hand,

neglectful parenting expects the child to manage problems independently, offers little support, and encourages the child to take responsibility for their own life, often neglecting to provide guidance or assistance [

11]. Children may develop resilience and self-sufficiency out of necessity, rather than through positive development. This lack of involvement can leave the child feeling incompetent and vulnerable, as they do not receive the support needed to build essential skills and emotional regulation. As a result, they often struggle with controlling their emotions, coping effectively, and facing difficulties in maintaining and nurturing social relationships. Eventually, the child’s ability to develop a strong sense of self is compromised, leading to further challenges in navigating setbacks [

40,

43].

The different parenting styles can significantly influence the development of narcissistic traits in children. Understanding these dynamics is essential for both researchers and practitioners aiming to address the root causes of narcissism and to promote healthier personality development.

3. Methodology

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed following the PRISMA guidelines. The study was registered in PROSPERO (an international prospective register for systematic review protocols) under the registration

CRD42024516395, and included a prespecified protocol.

To ensure the integrity of the data extraction process, a systematic approach was employed. Two independent reviewers screened the eligibility of studies based on their titles and abstracts. Articles passing this initial screening underwent full-text review. Extracted data included title, authors, publication year, narcissism scale, information for effect measure computation, and risk of bias assessment.

In line with the systematic selection process, specific inclusion criteria were applied to ensure consistency across the studies analyzed. Eligible studies needed to feature participants who had completed a validated narcissism scale, thus guaranteeing reliable measurement of narcissistic traits. Participants were required to be at least six years old, a threshold informed by developmental psychology theories, such as those proposed by Jean Piaget and Erik Erikson, which suggest that personality traits and self-concept begin to emerge more distinctly around this age. Additionally, studies had to report at least one relevant outcome measure, be published in English or Portuguese, and have a publication date no earlier than 2000, ensuring the inclusion of contemporary research.

A first search for articles was carried out on PubMed and Scopus on 2nd January 2024, using Boolean operators and the following search terms: (narcis*) AND (cognitive OR parent* OR educat*).

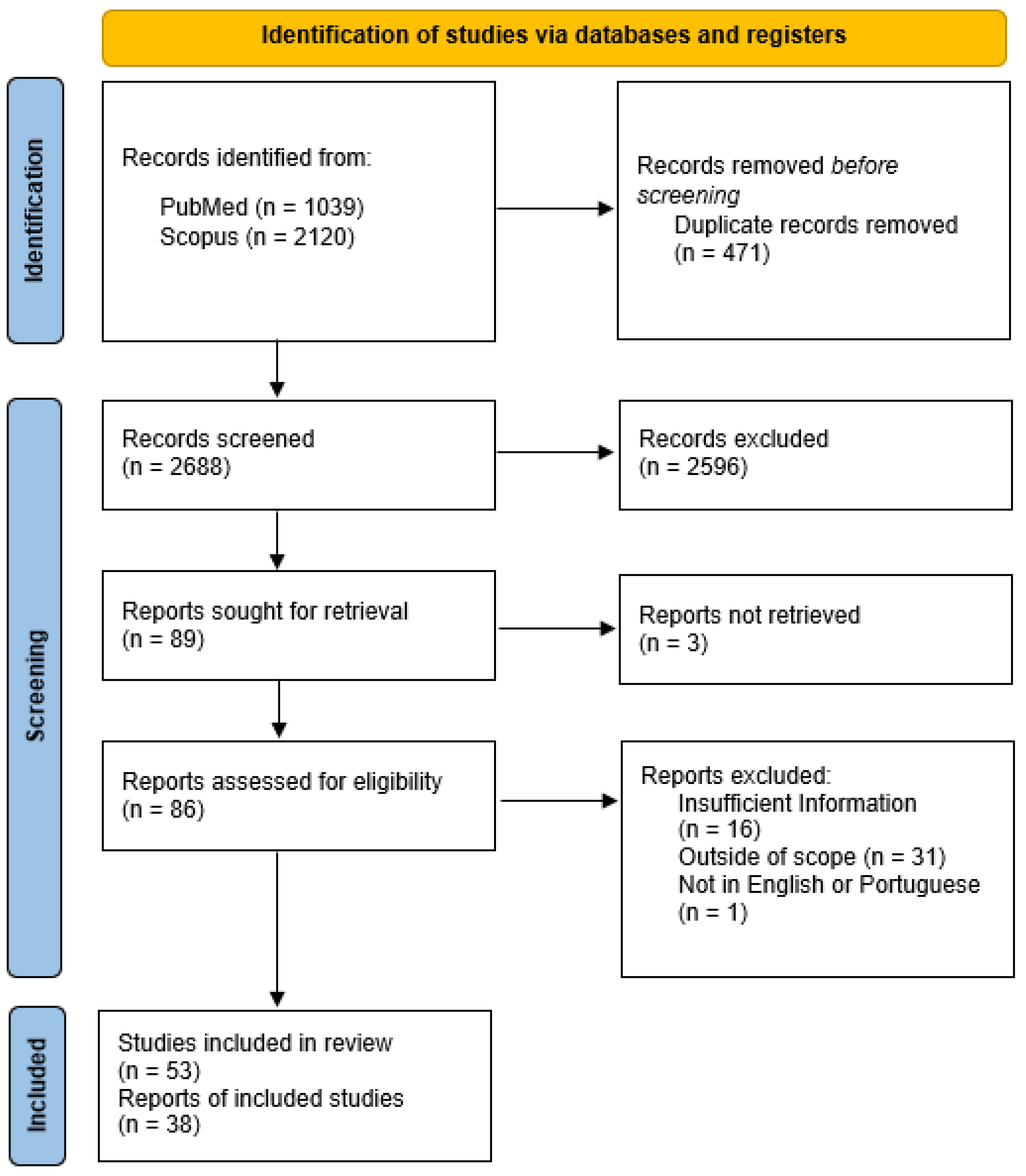

After screening the titles and abstracts, 2596 articles were excluded. Out of 89 qualified studies, 16 did not provide quantitative data, 31 were outside of scope, 3 the full version of the article could not be retrieved, and 1 was not written in English or Portuguese. A total of 38 studies examining the relationship between parental education and narcissism were included in the final analysis, cf.

Figure 1.

Table A1 (

Appendix A) summarize all the studies included in the final analysis. The studies addressing parental education analyze various characteristics such as overprotection, rejection, and corporal punishment, among others. Consequently, these characteristics were associated with established parenting styles – authoritative, authoritarian, neglectful, and permissive, as detailed in

Section 2.2. In situations where multiple characteristics were identified for a single parental style, a 90% confidence interval for the correlation was calculated. If there was an overlap within the confidence intervals, an average was taken; otherwise, the characteristics were excluded.

Additionally, specific terminology was employed to clarify the study. Therefore, the term “parenting” and “parents” refers to the influence of both parents, while “maternal” or “mother” corresponds to the mother’s role, and “paternal” or “father” relates to the father’s influence. The term “overall” was used when discussing narcissism without distinguishing between its subtypes, while “grandiose” and “vulnerable” specifically denote grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, respectively.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

In this meta-analysis, the effect measures considered were partial and zero-order correlations. Partial correlations were preferred over zero-order correlations, as they measure the strength of a relationship between two variables while controlling for the effect of one or more other variables, thereby providing a more accurate representation of the relationships under investigation.

For data synthesis, statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the

statistic which estimates the fraction of variance that is due to heterogeneity, i.e.,

where

represents the average within-study variance, and

denotes the between study-variance. A value between 25% and 75% indicates moderate heterogeneity and above 75% indicates high heterogeneity. The models were selected based on the

statistic, with a fixed-effects model being used if the value was less than 25%, and a random-effects model being used otherwise. The fixed-effects model assumes that all studies share a common true effect size

and that observed differences are only due to sampling error. An estimator of the common true effect

is given by

where

is the observed effect size in study

i, and

is the inverse of the variance of the study

i (i.e.,

) for

. In the random effects model, the weights are the inverse of the sum of the between-study variance

and the within-study variance

, i.e.,

. In this setting,

is treated as a random variable that follows a normal distribution with mean

and variance

, i.e.,

. In both models,

is assumed to follow a normal distribution. Data analysis was conducted using R statistical software and metacor package [

44,

45].

During the analysis, confidence intervals (CI) were reported at the 95% level, and hypothesis tests were conducted with a significance level of 5%.

Publication bias, if present, was assessed using funnel plots, Egger’s test, and the trim and fill method [

46,

47,

48].

It’s noteworthy that a minimum criterion has been set for the analysis, as it’s necessary to have a minimum number of studies that provide a sufficient basis for reliable statistical analysis and meaningful conclusions. Therefore, in cases where fewer than three studies were available, the analysis was not carried out.

3.2. Quality Analysis

The included studies were evaluated for risk of bias using established critical appraisal tools. Two researchers independently assessed each study, with any discrepancies resolved by a third researcher. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) were used to evaluate methodological quality, with studies scoring at least 8 out of 10 points considered high quality. The original scale was modified to accommodate the particular circumstances under examination in this analysis. The employed scale and its respective adaptation is detailed in the

Appendix B, while the individual study scores are presented in

Table A1.

To assess the sensitivity of the conclusions, in cases that included studies scored less than eight on the NOS, two analyses were performed: one including all studies regardless of NOS score and another including only those scoring eight or higher, comparing the results accordingly.

4. Results

This section provides an overview of the findings, organized according to parental education. The statistical analysis and significant patterns observed during the study are presented in detail, forming the basis for the discussion and conclusions that will be presented in the following sections.

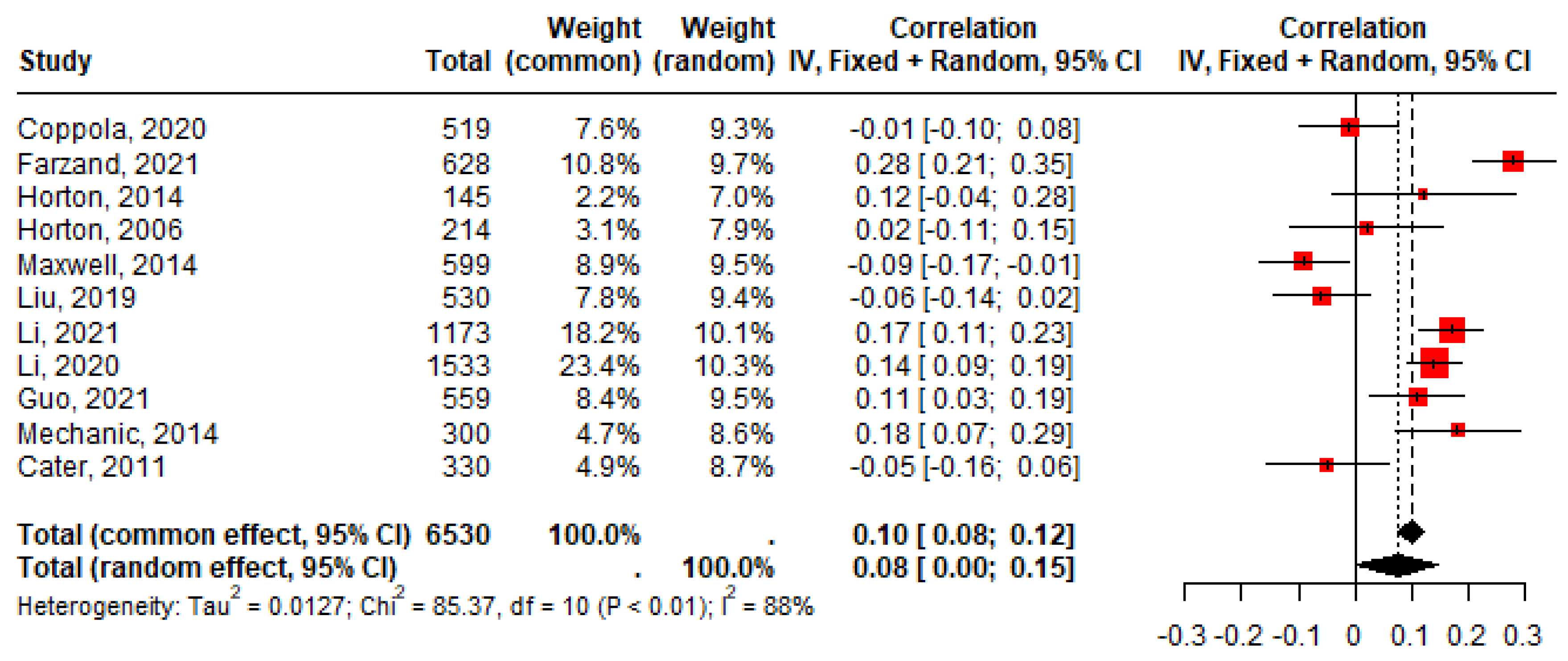

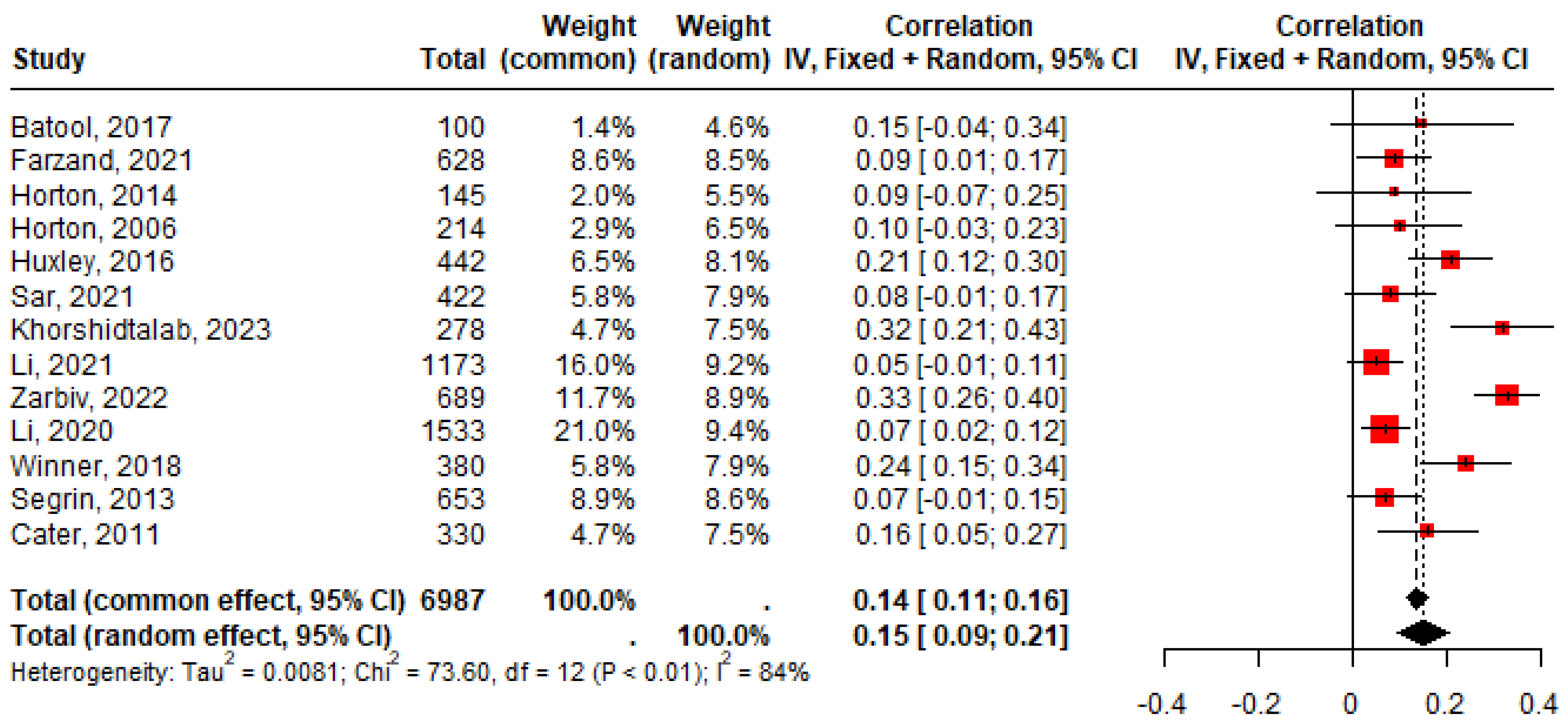

A total of 11, 13, 9, and 6 studies were found relating overall narcissism to parenting styles authoritative, authoritarian, neglectful, and permissive, respectively.

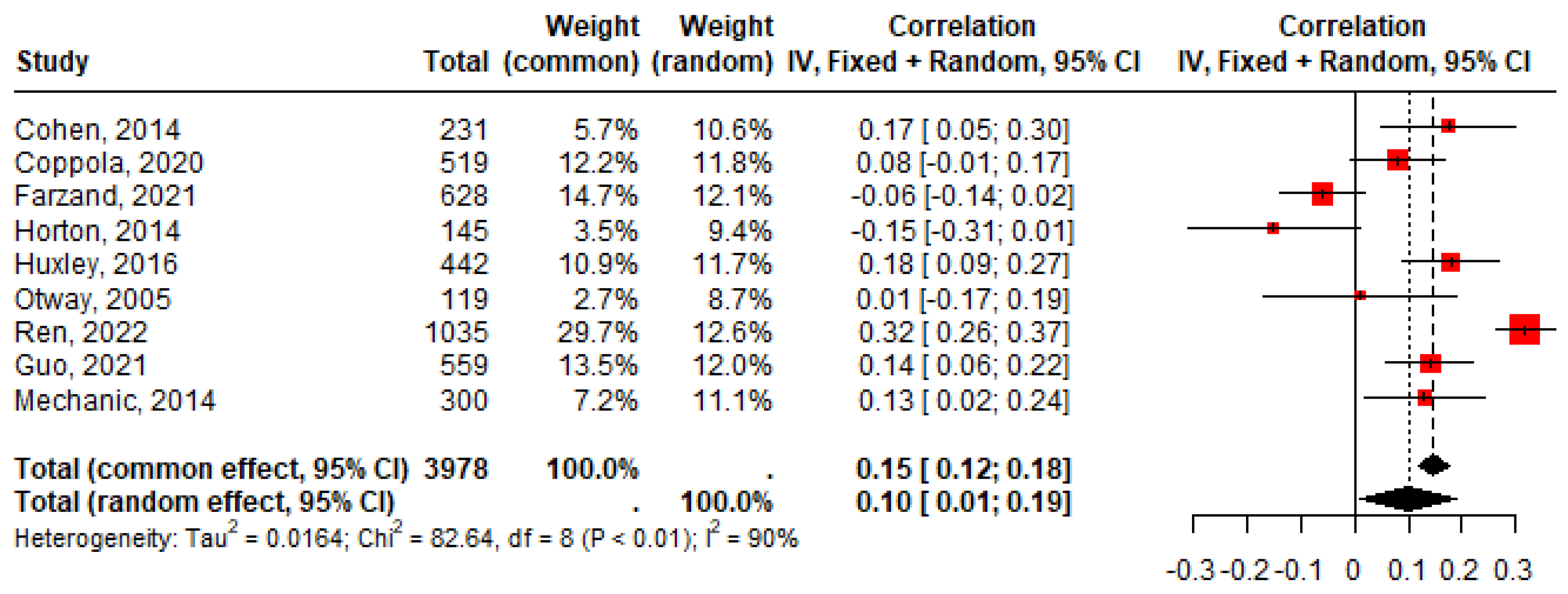

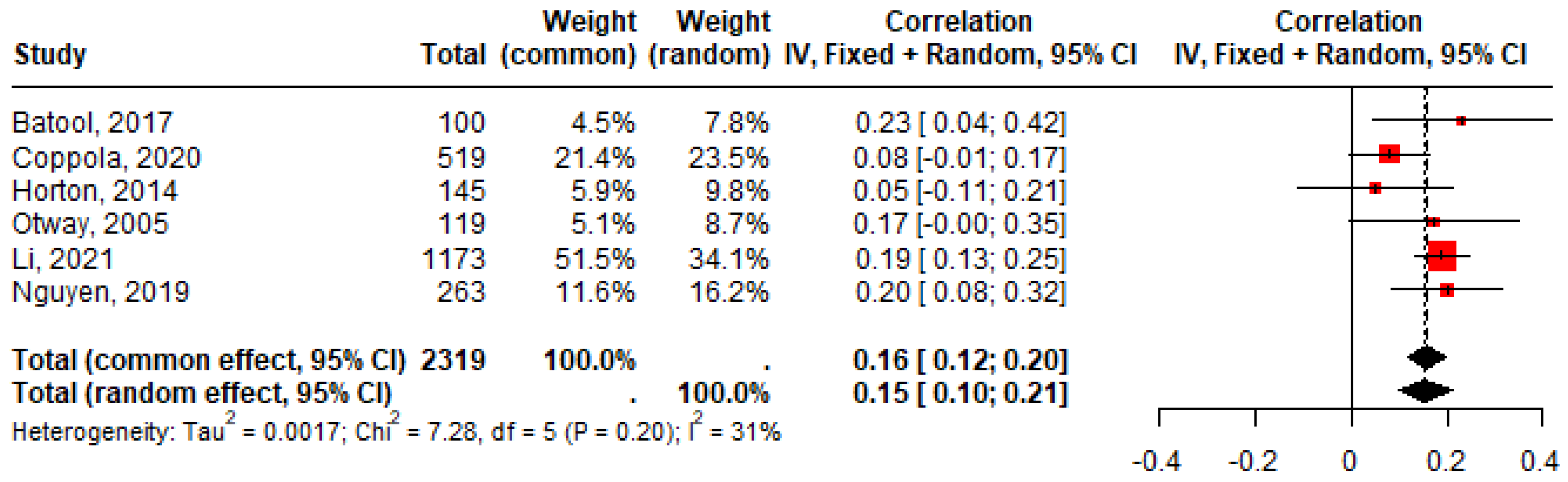

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present forest plots summarizing the findings. In all cases, the results revealed significant heterogeneity for the authoritative, authoritarian, and negligent education (authoritative: Q(6530) = 85.37,

p < 0.0001; authoritarian: Q(6987) = 73.60,

p < 0.0001; negligent: Q(3978) = 82.64,

p < 0.0001). Results also showed that the magnitudes of heterogeneity were large for these three parenting styles (authoritative:

= 88.3%; authoritarian:

= 83.7%; negligent:

= 90.3%). Only results for the permissive style showed moderate heterogeneity (Q(2319) = 7.28,

p = 0.2005,

= 31.3%).

Given this heterogeneity in all instances, the overall estimates were calculated using a random-effects model. The highest correlations were observed for the permissive (0.15, CI 95% [0.10; 0.21]) and authoritarian (0.15, CI 95% [0.09; 0.21]) styles, followed by neglectful (0.10, CI 95% [0.01; 0.19]), and authoritative (0.08, CI 95% [0.00; 0.15]) styles.

Upon examination of the forest plots, it becomes evident that the confidence intervals intersect, thereby rendering it plausible to suggest that the correlation values are equal. Concerning all parenting styles, a significant, albeit weak, correlation with narcissism is observed, with an estimated range between 0.08 and 0.15.

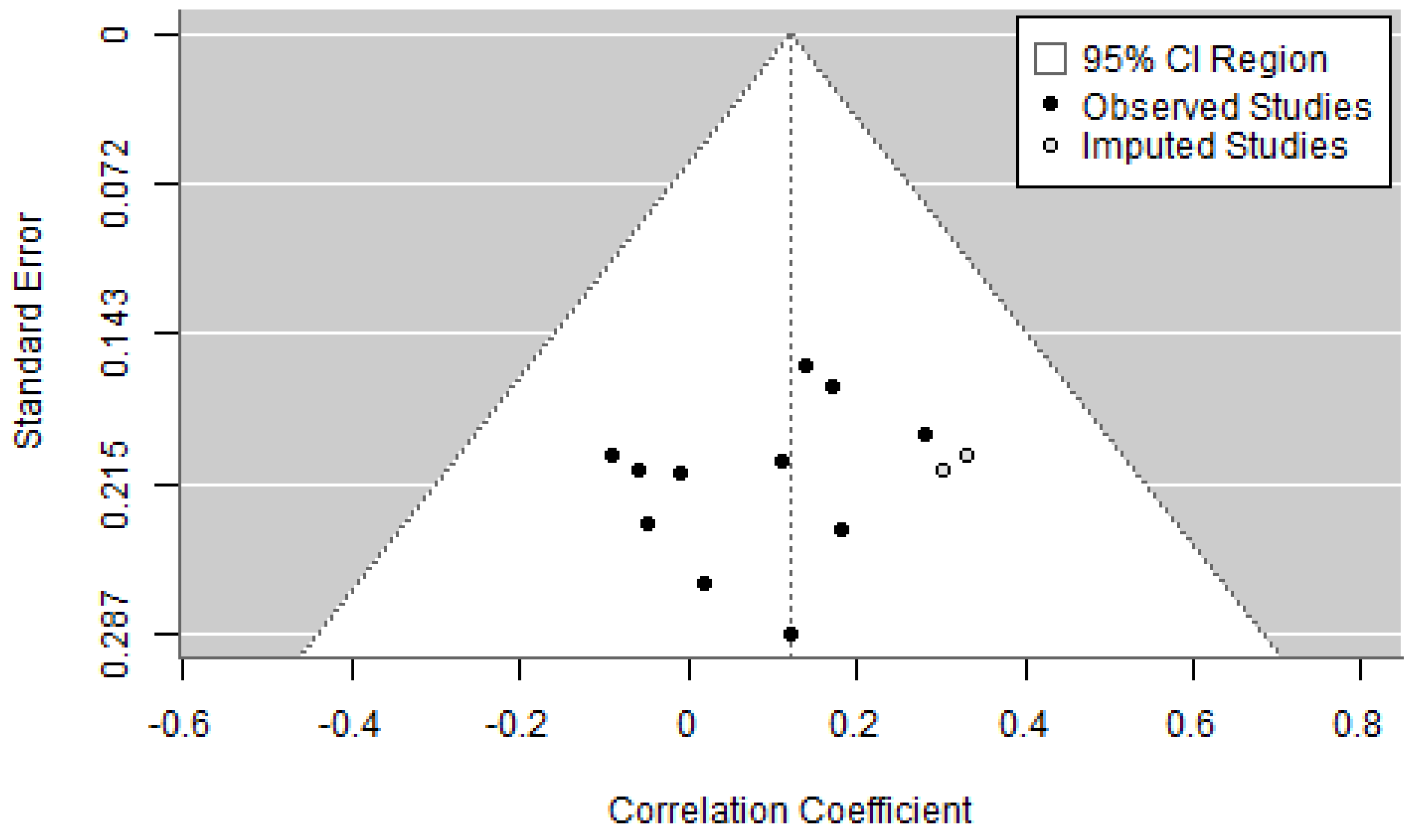

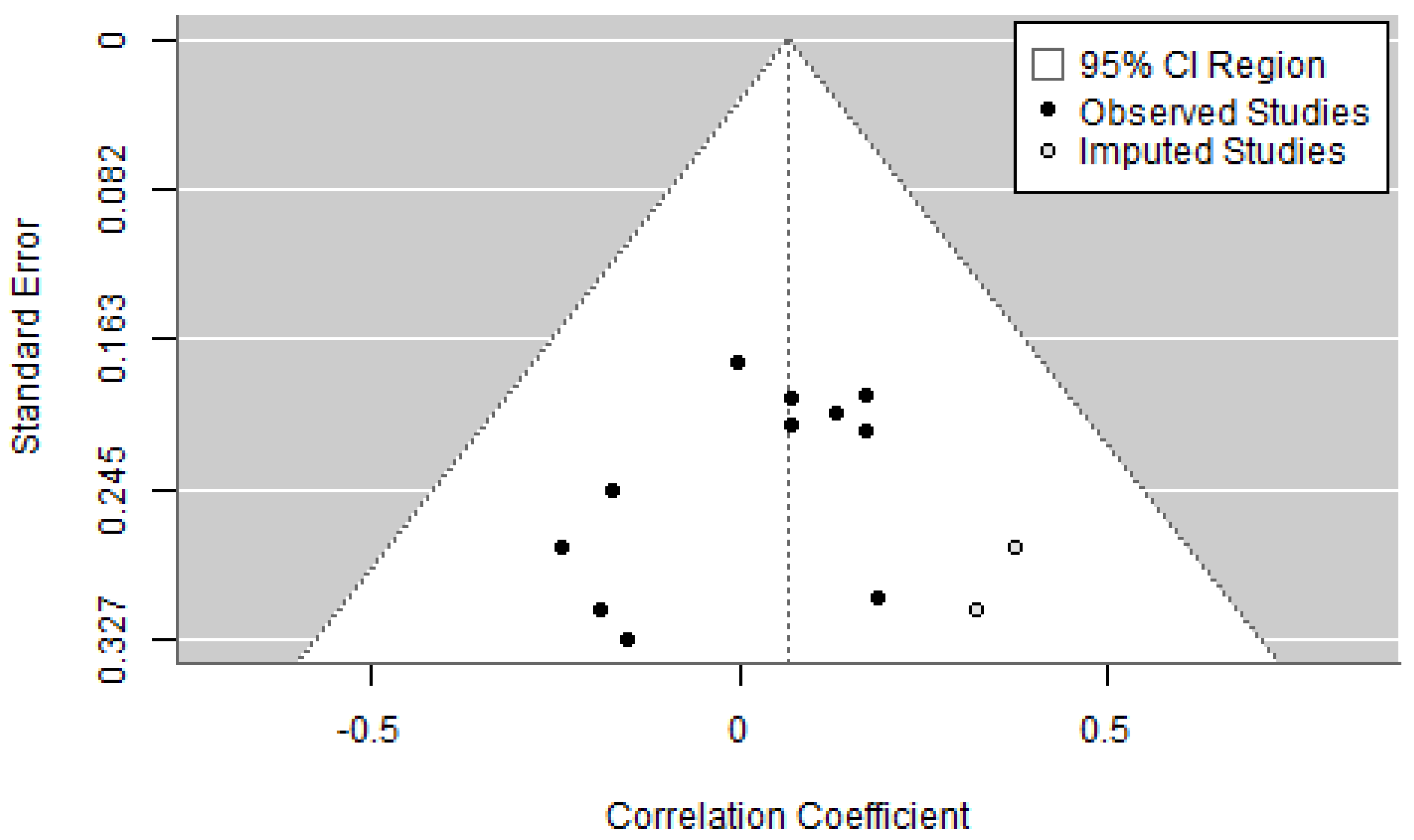

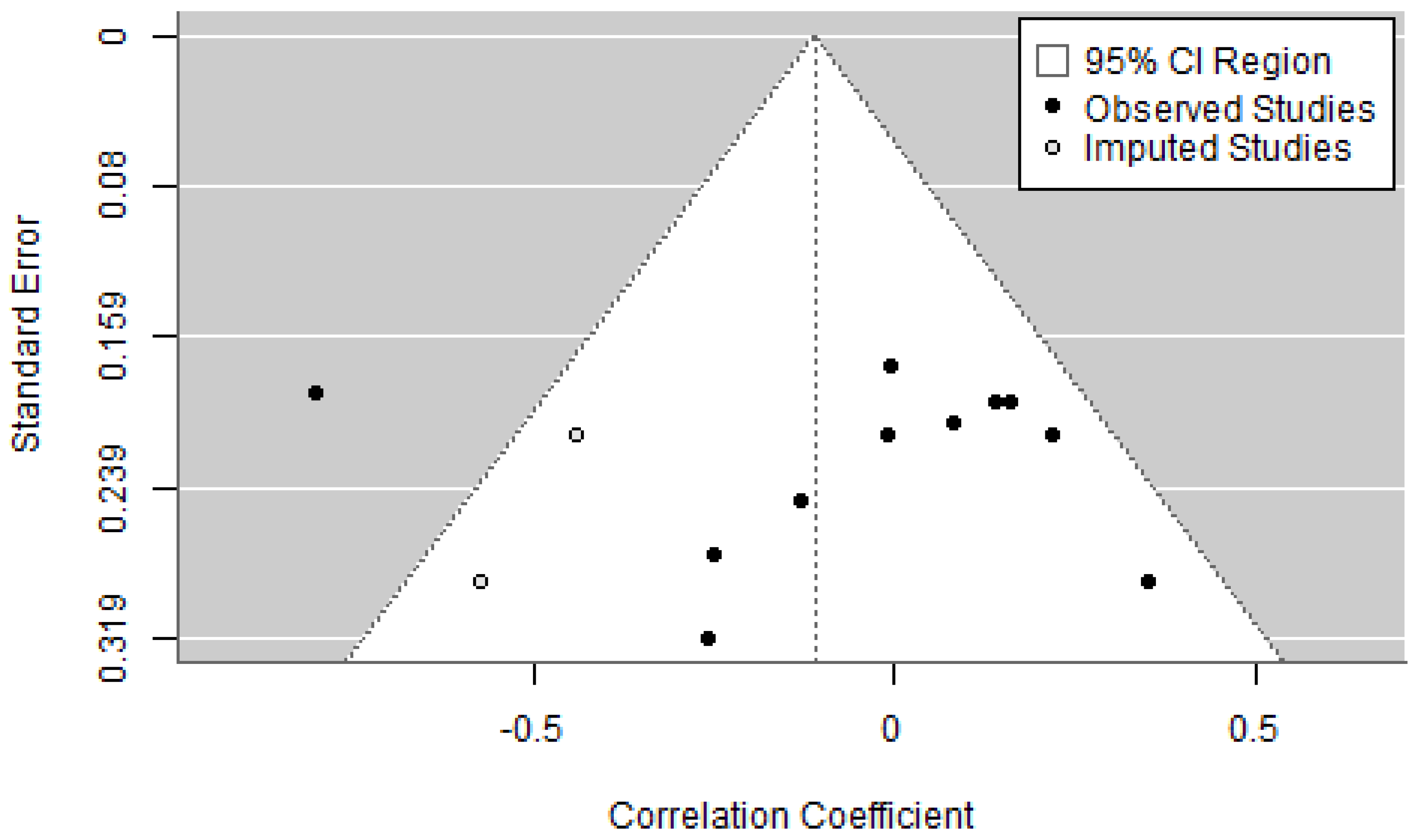

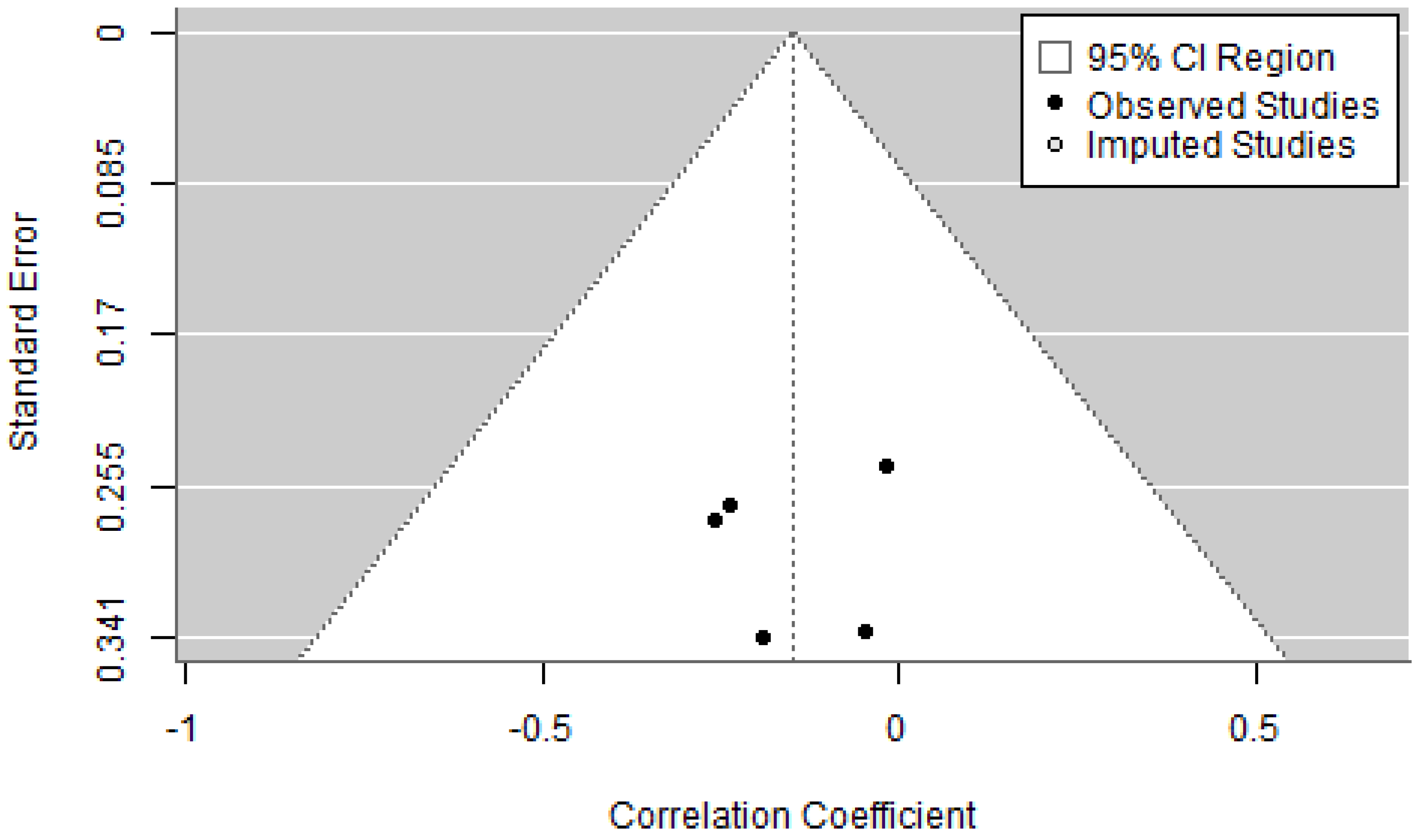

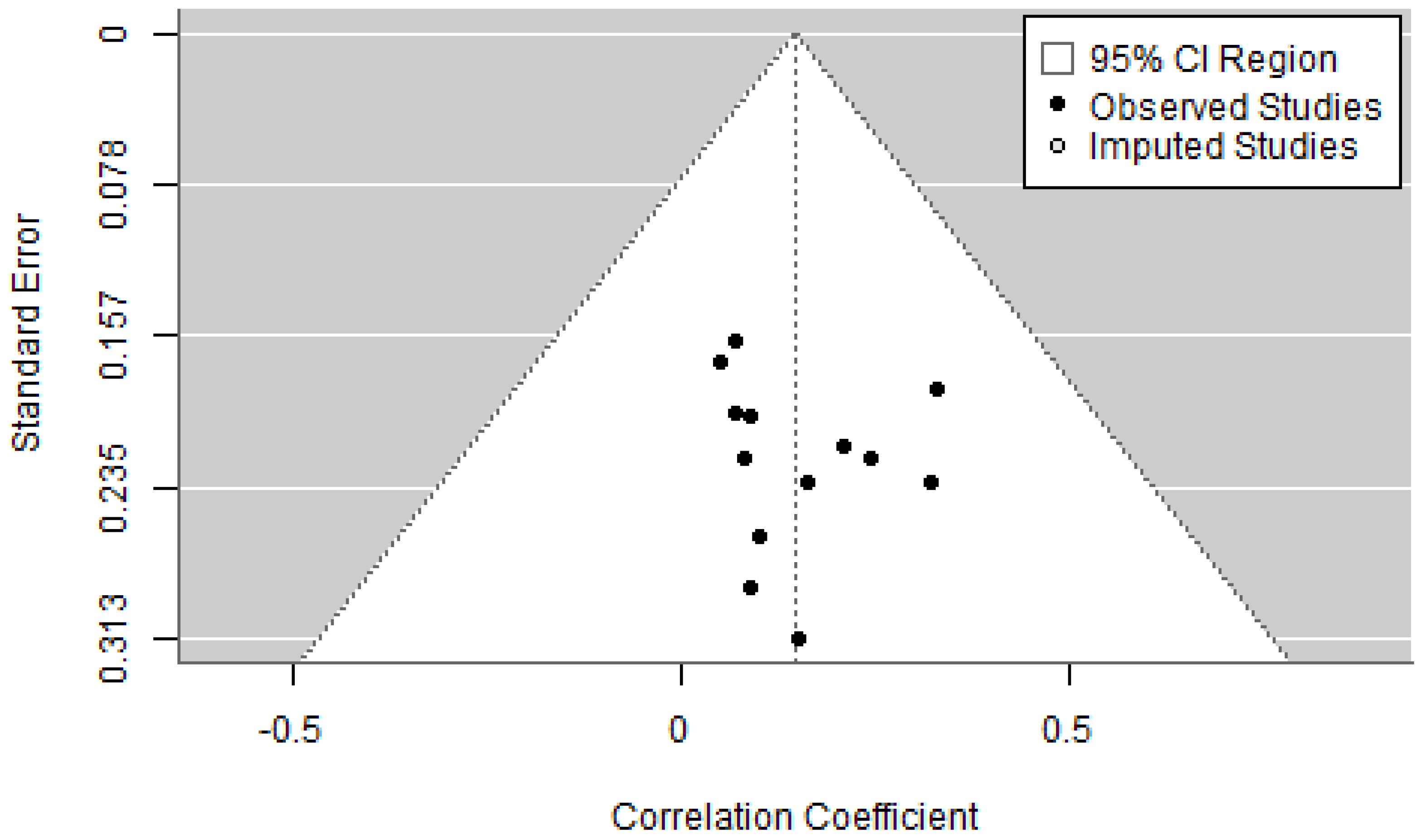

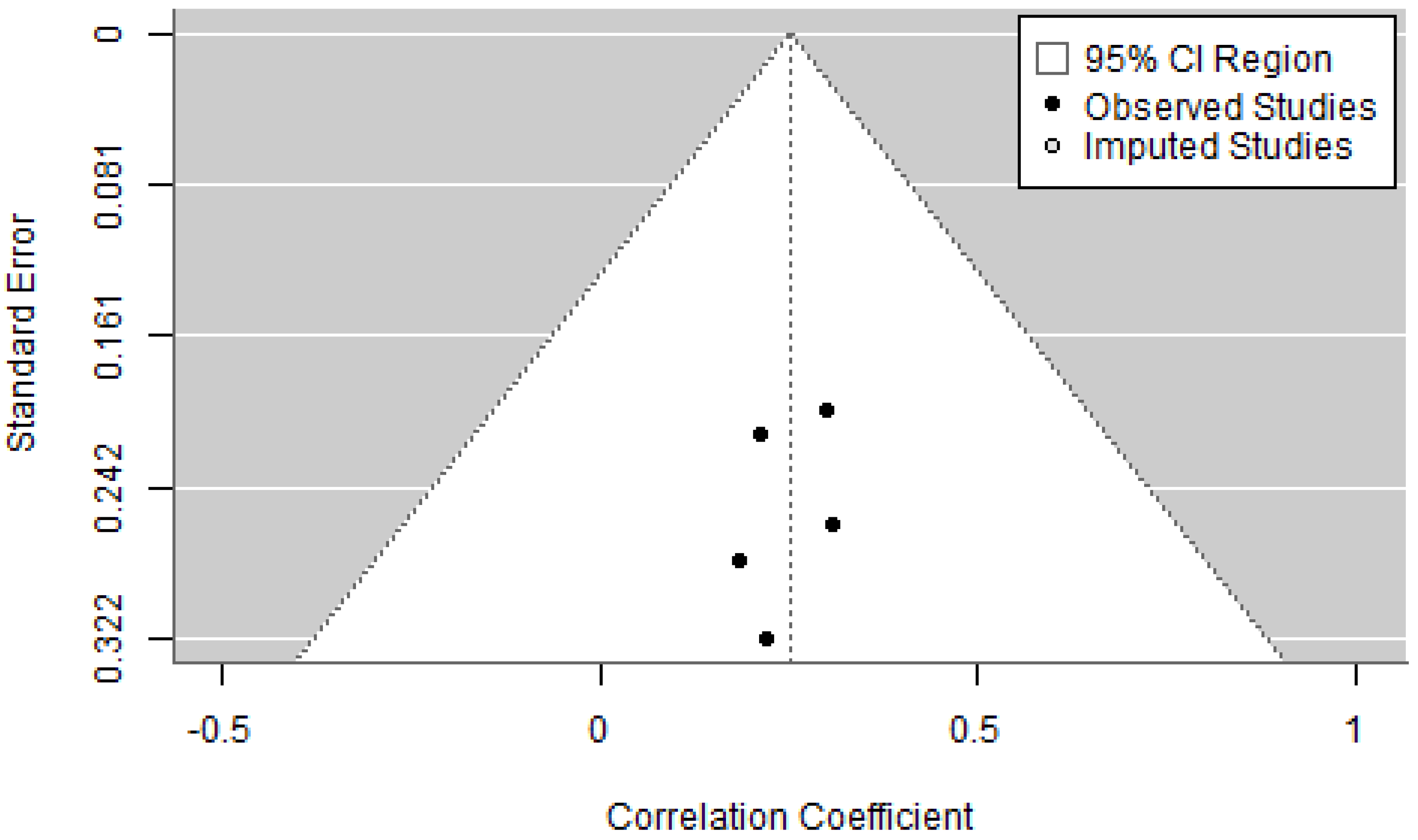

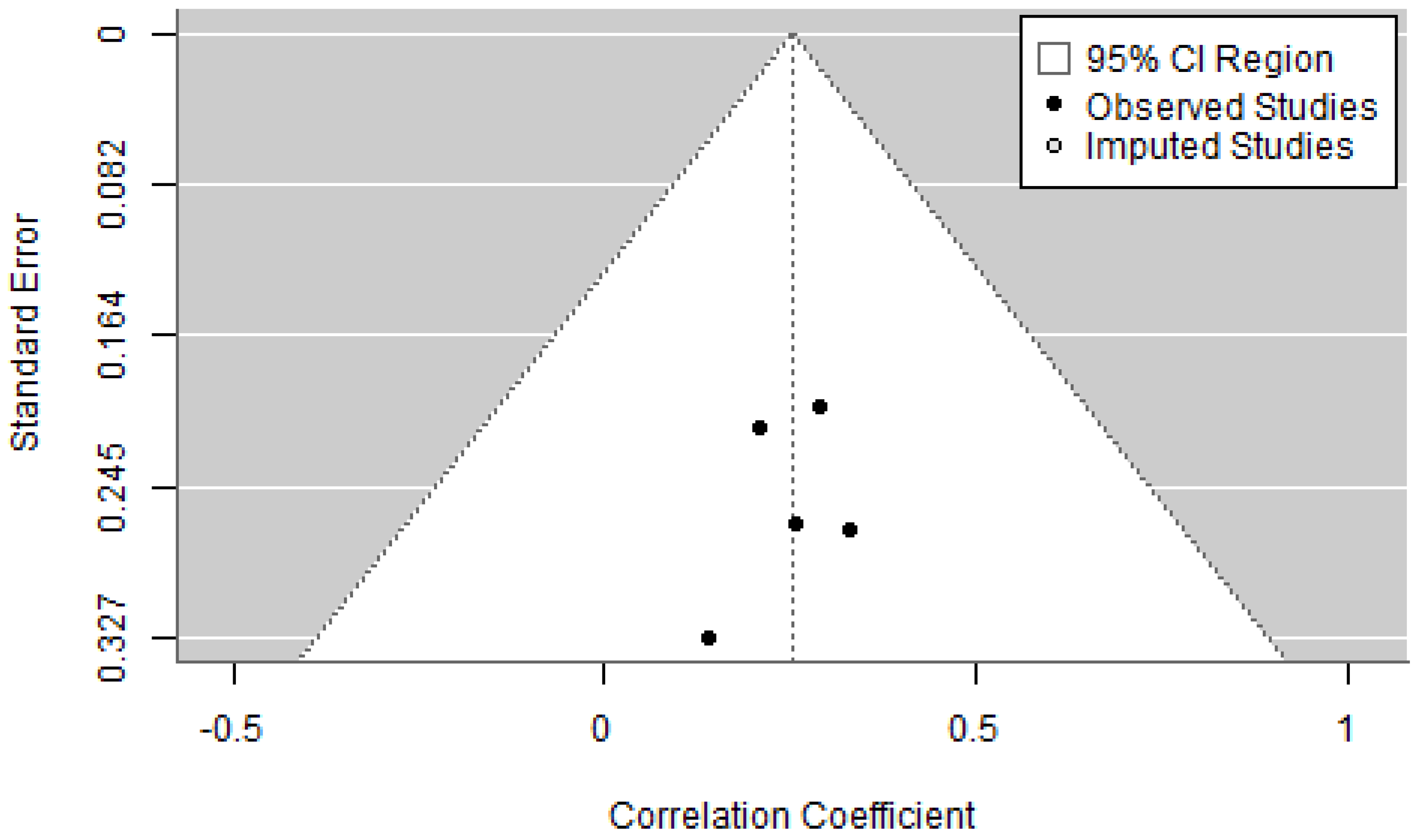

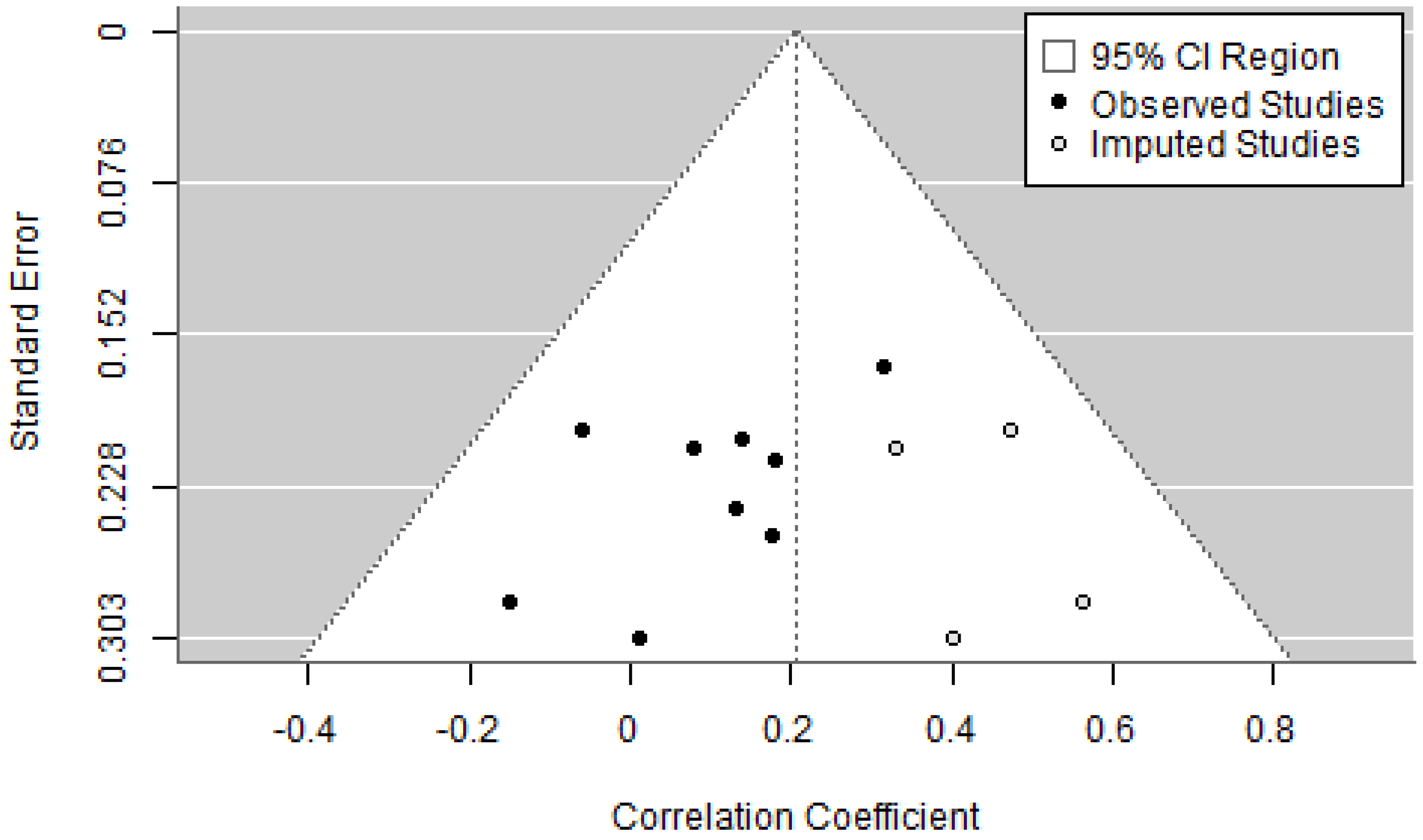

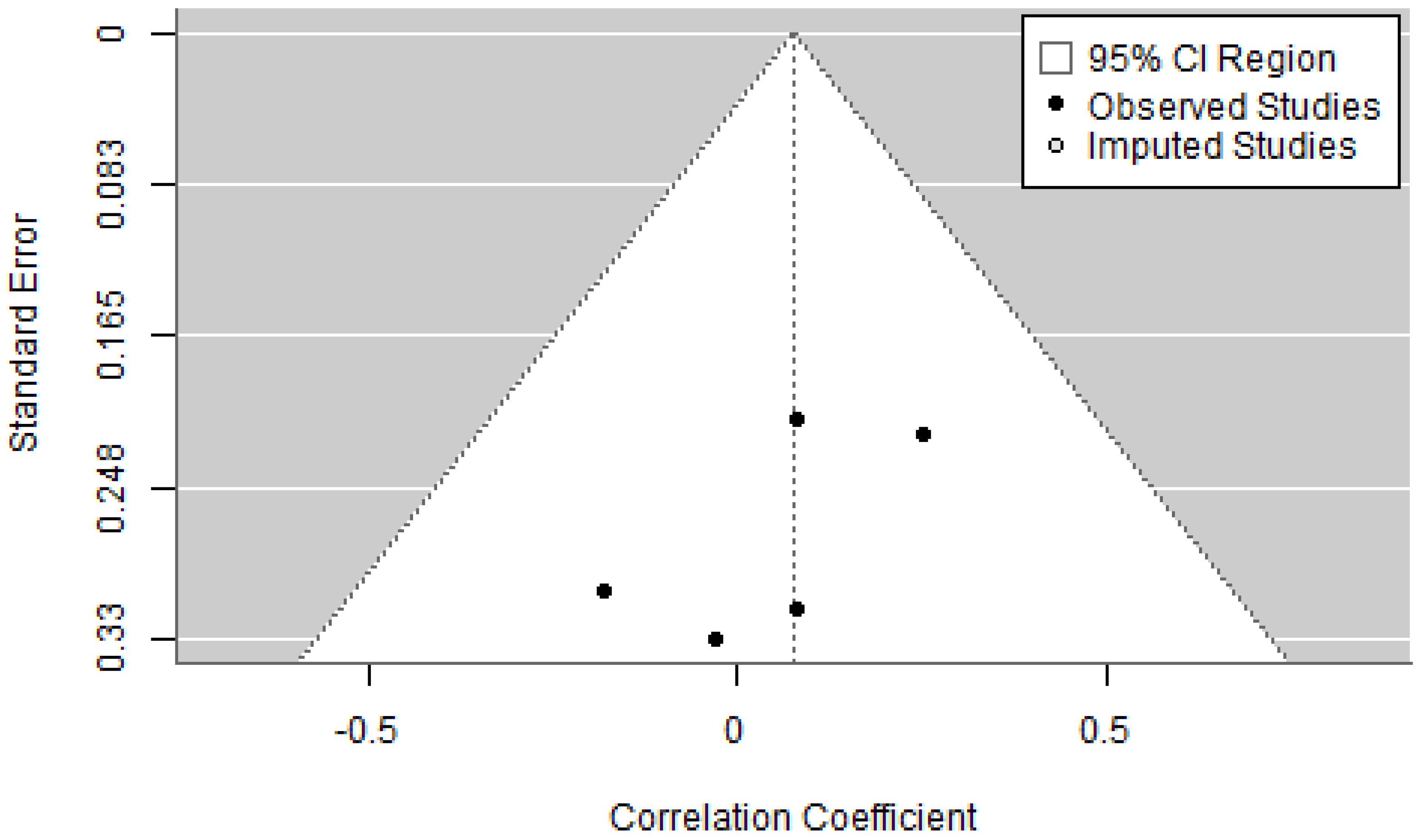

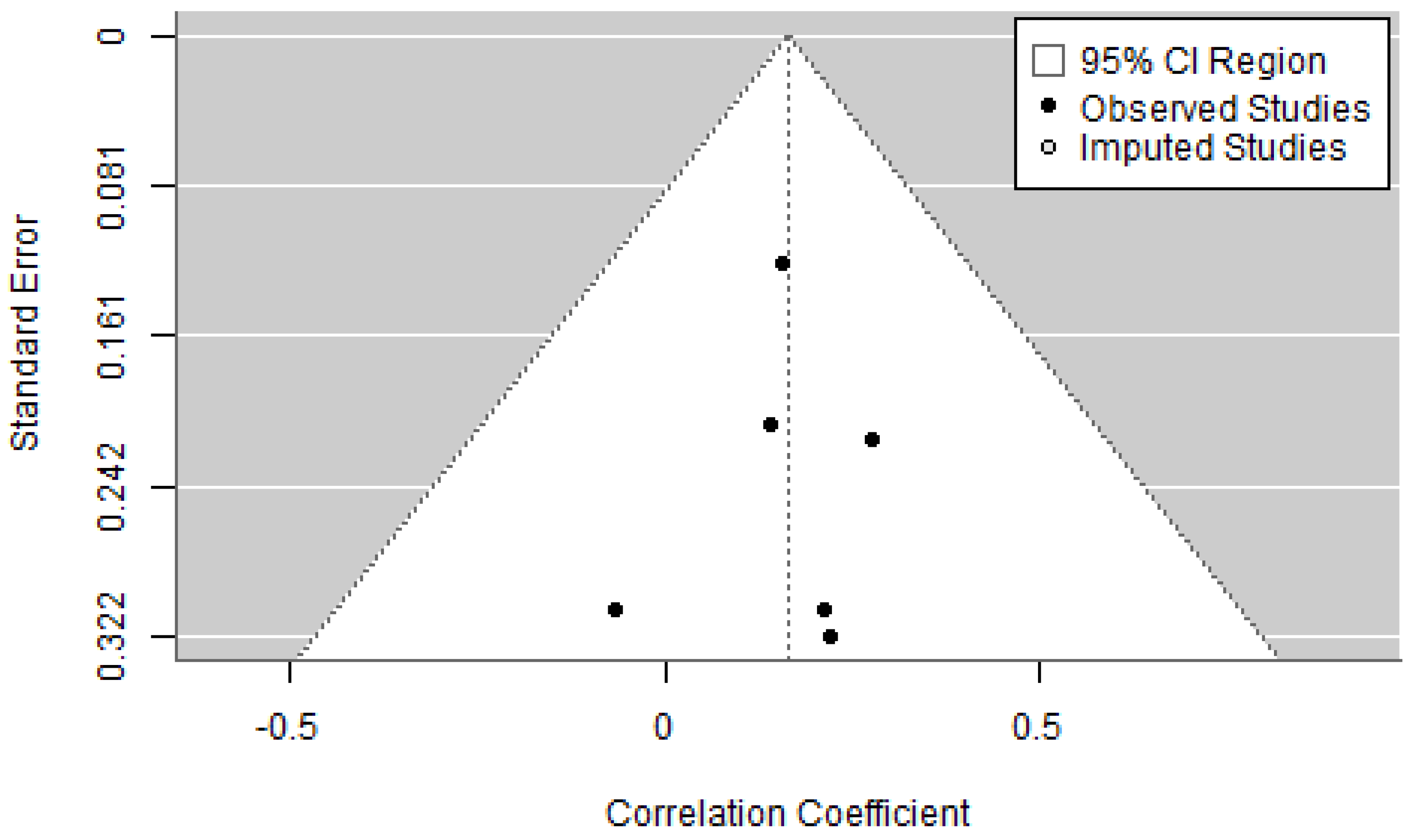

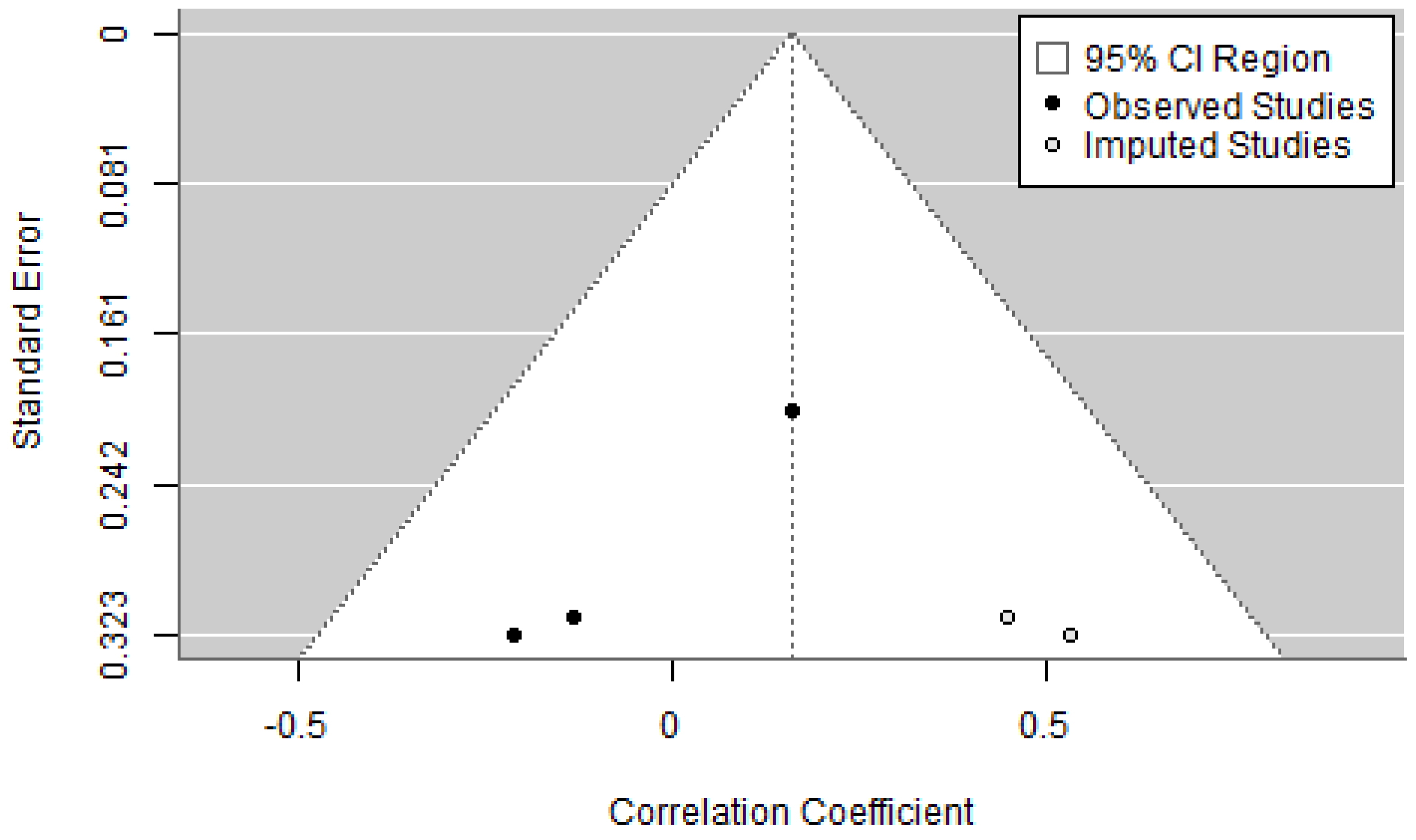

Funnel plots, the trim-and-fill method, and Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry were employed to investigate the potential for publication bias. As illustrated in

Appendix C (

Figure A1,

Figure A9,

Figure A15 and

Figure A19), the funnel plots for permissive and authoritarian parenting styles exhibit symmetrical patterns. However, the plots for authoritative and neglectful styles reveal potential missing studies, with two and four studies respectively.

Despite these observations, the p-values from the Egger’s tests for funnel plot asymmetry are substantially higher than 0.05 (authoritative: p = 0.5533; authoritarian: p = 0.7727; negligent: p = 0.2736; permissive: p = 0.9582), indicating that the results of the meta-analyses are not significantly affected by publication bias.

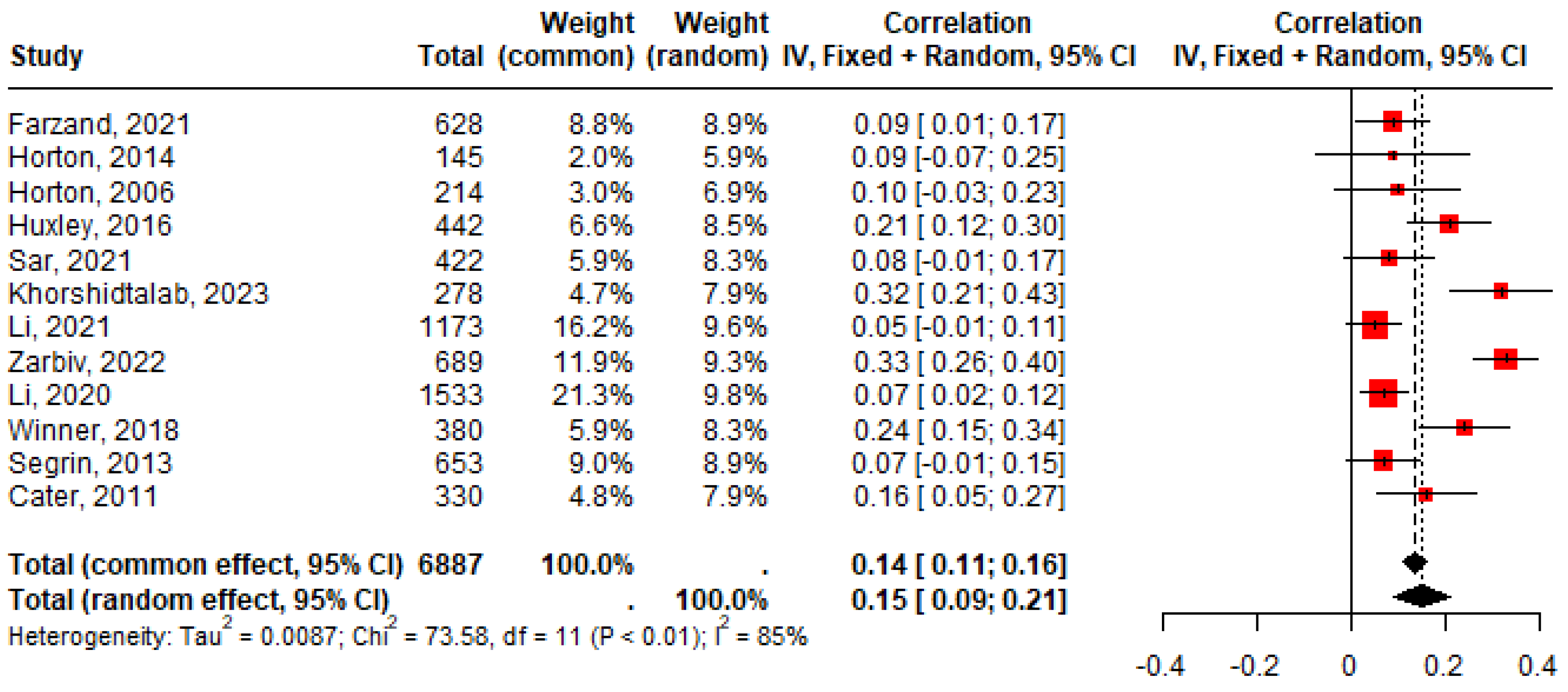

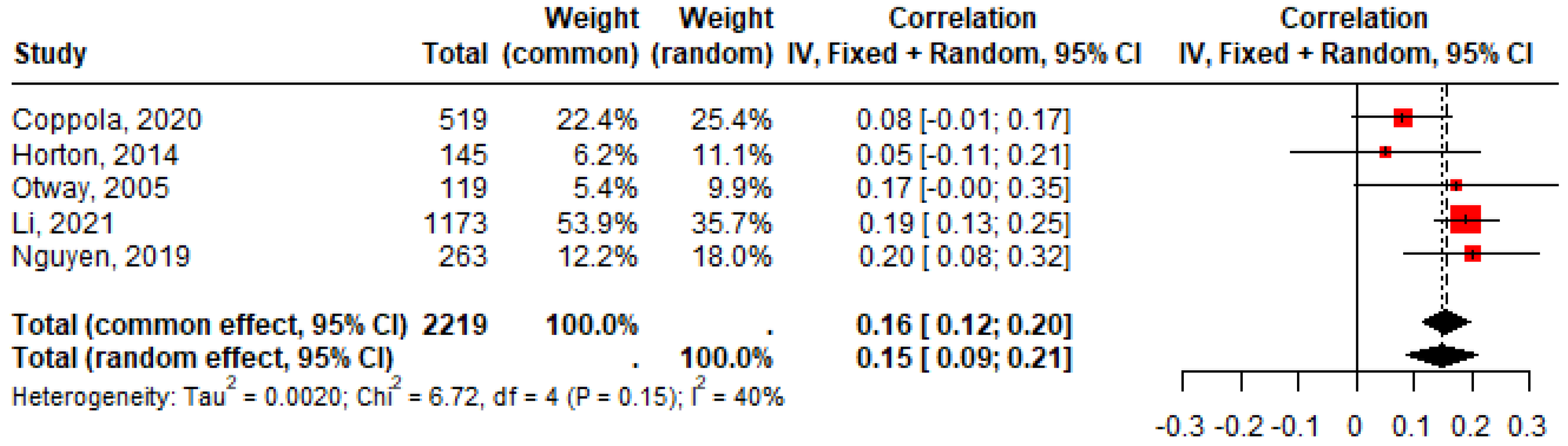

In the analysis examining the relationship between authoritarian and permissive parenting and overall narcissism, a study was identified with a NOS score below eight. Therefore, a second analysis was performed, excluding this lower-quality study, to assess the robustness of the findings, cf.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. In this secondary analysis (authoritarian: 0.15, CI 95% [0.0919; 0.2102]; permissive: 0.15, CI 95% [0.0853; 0.2082]), the conclusions remained consistent with the primary analysis, indicating that the lower-quality study did not significantly influence the overall results. This reinforces the reliability of the conclusions drawn from the full dataset, as the observed results were not contingent on the exclusion of studies with potential methodological limitations.

4.1. Narcissism and Authoritative Education

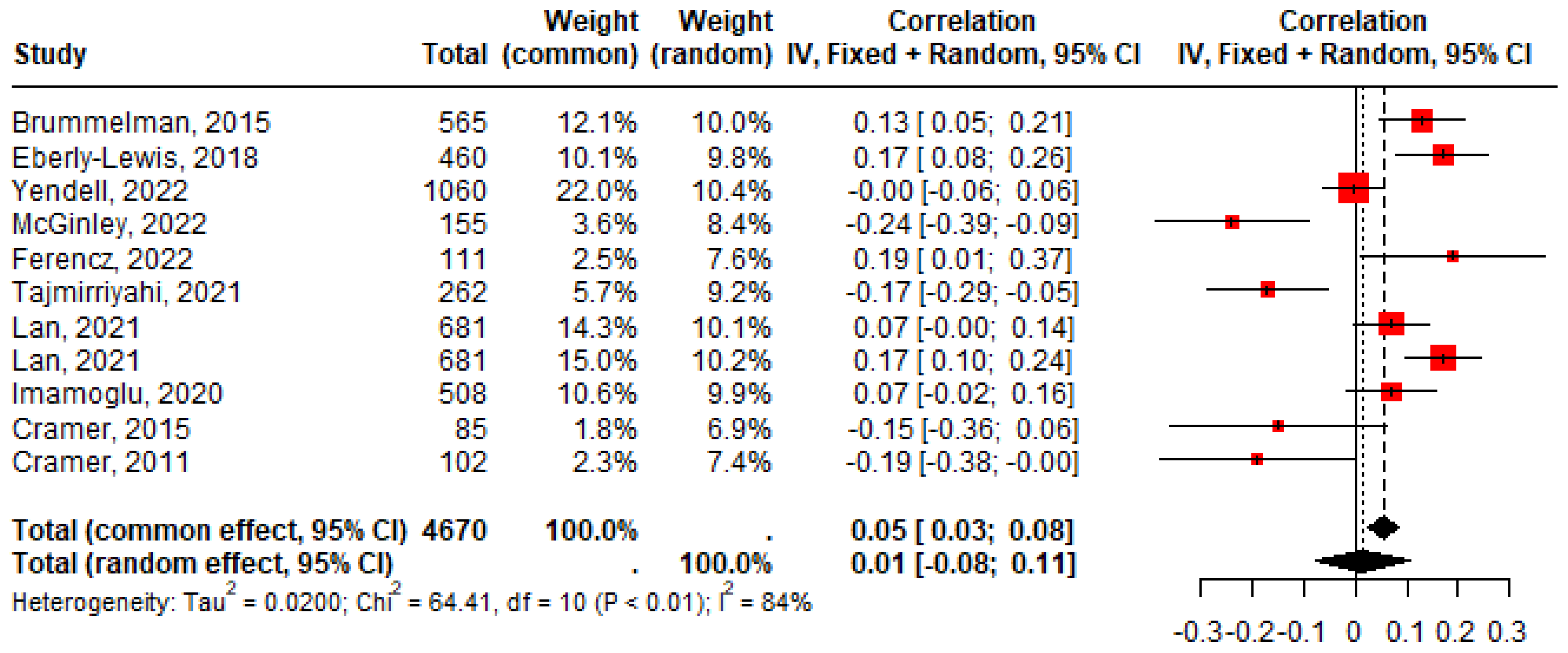

Focused on maternal and paternal education, a total of 11 studies were identified for each, examining the correlation between the authoritative parenting style and overall narcissism.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 present forest plots summarizing the findings. A significant heterogeneity was evident for both maternal and paternal education (mother: Q(4670) = 64.41,

p < 0.0001,

= 84.5%; father: Q(4670) = 580.97,

p < 0.0001,

= 98.3%).

Consequently, a random-effects model was used to analyze the correlation. Observing the forest plots, the confidence intervals for the correlations between overall narcissism and both maternal and paternal authoritative parenting overlap with zero, suggesting that these correlations are not statistically significant (mother: 0.01, 95% CI [-0.0764; 0.1061]; father: -0.05, 95% CI [-0.2322; 0.1415]).

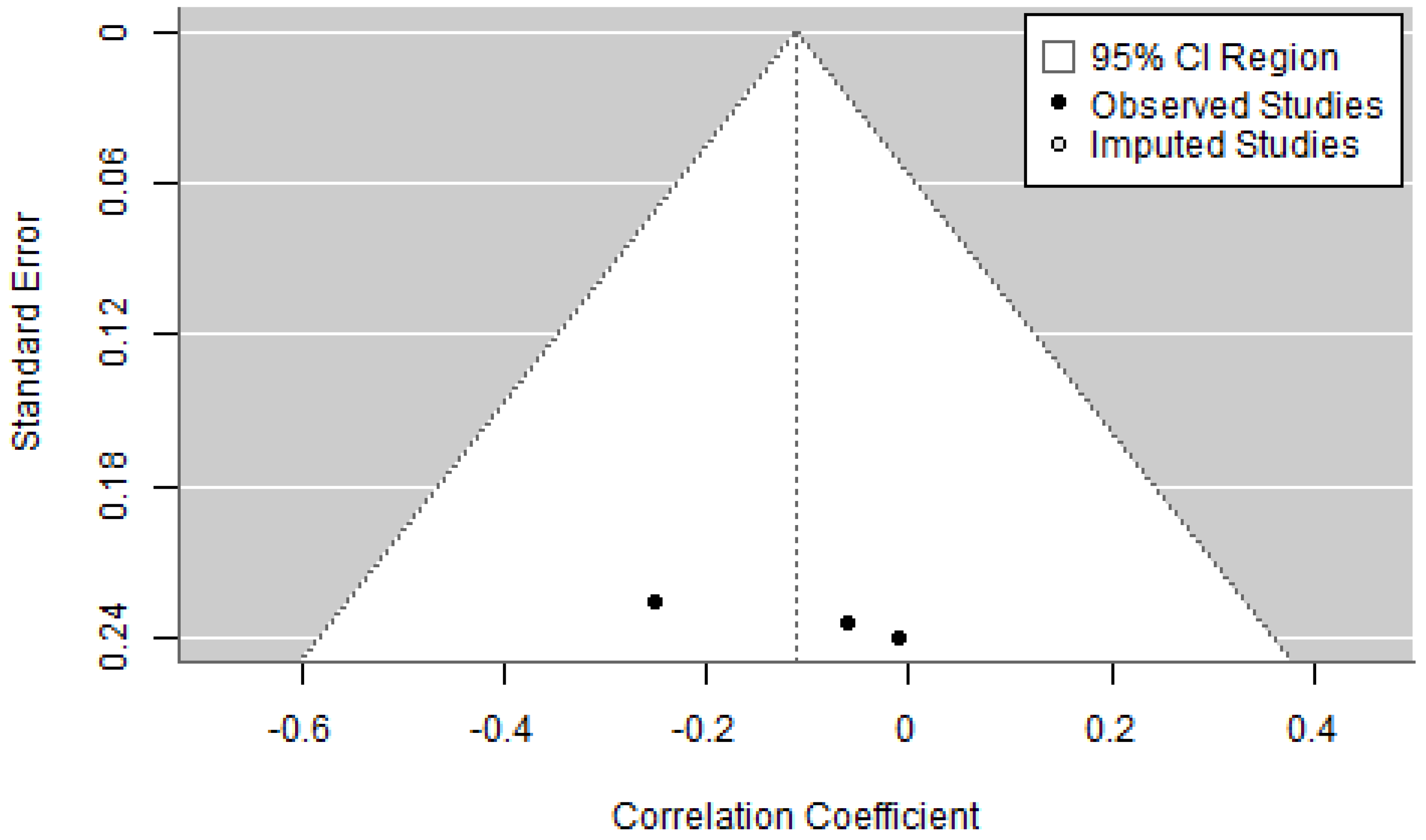

Although funnel plots identify two missing studies for both maternal and paternal influences (

Figure A2 and

Figure A3 in

Appendix C), the

p-values from the regression tests for funnel plot asymmetry remain well above the 0.05 threshold (maternal:

p = 0.3003; paternal:

p = 0.9498). This suggests that publication bias is not significantly affecting the results of these meta-analyses.

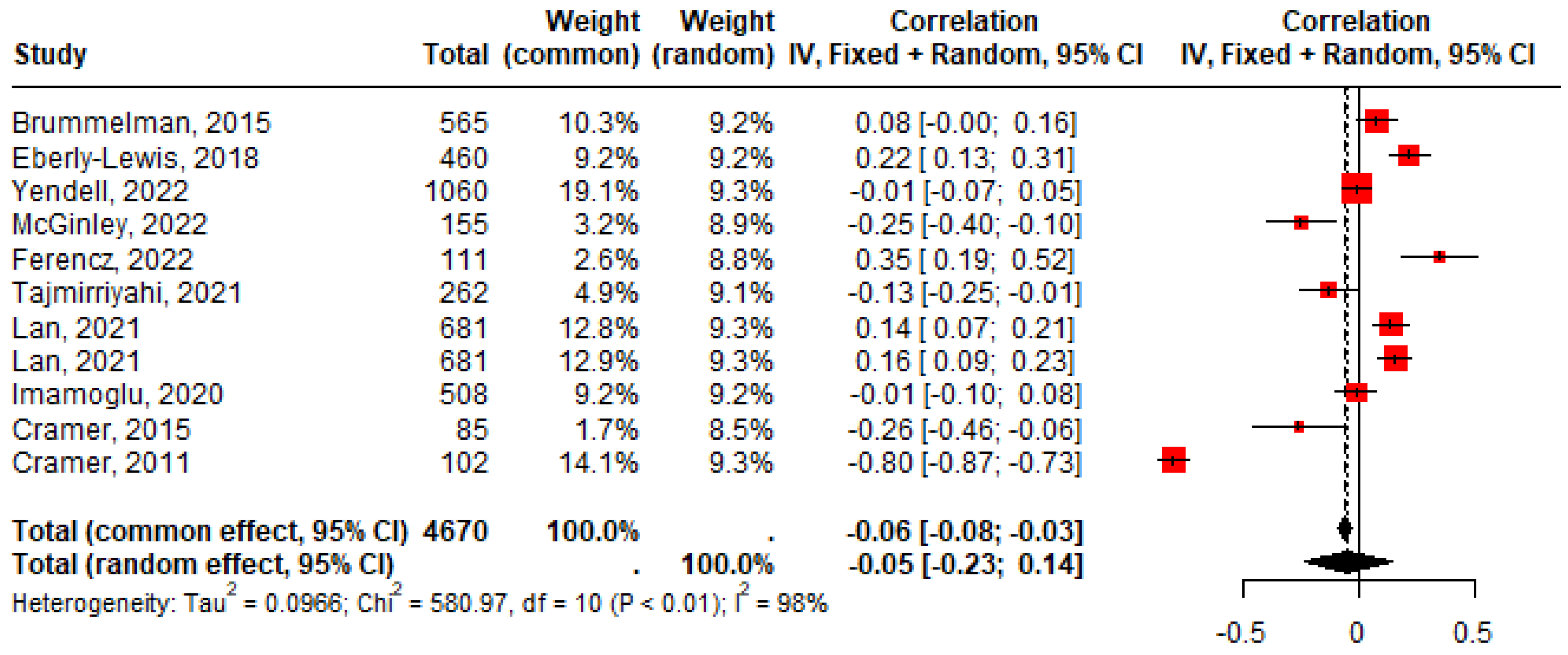

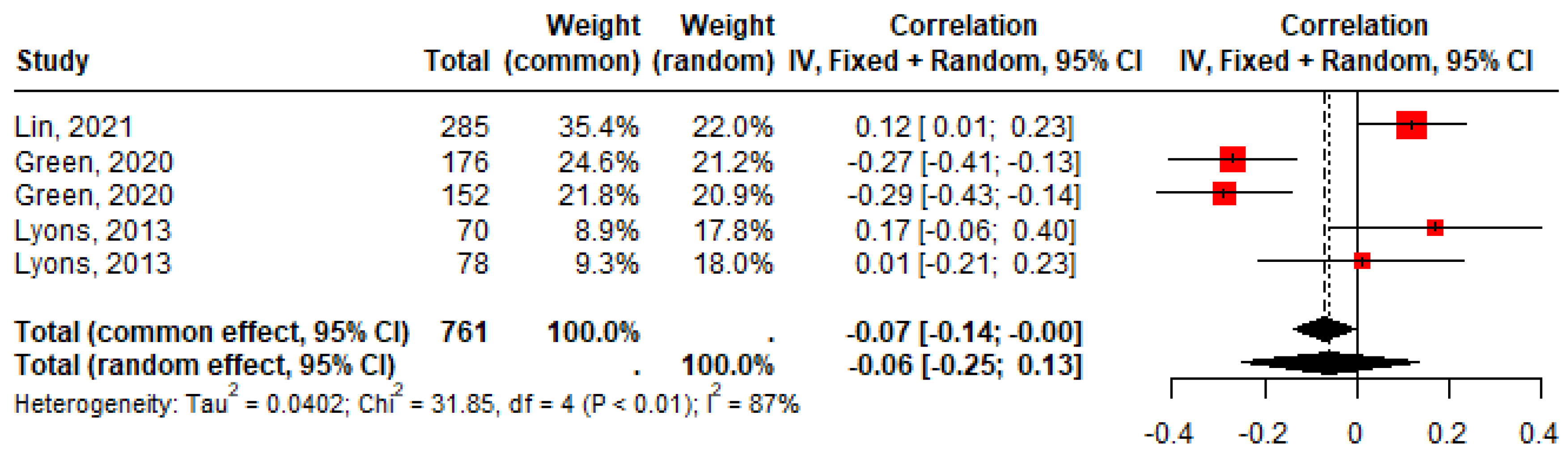

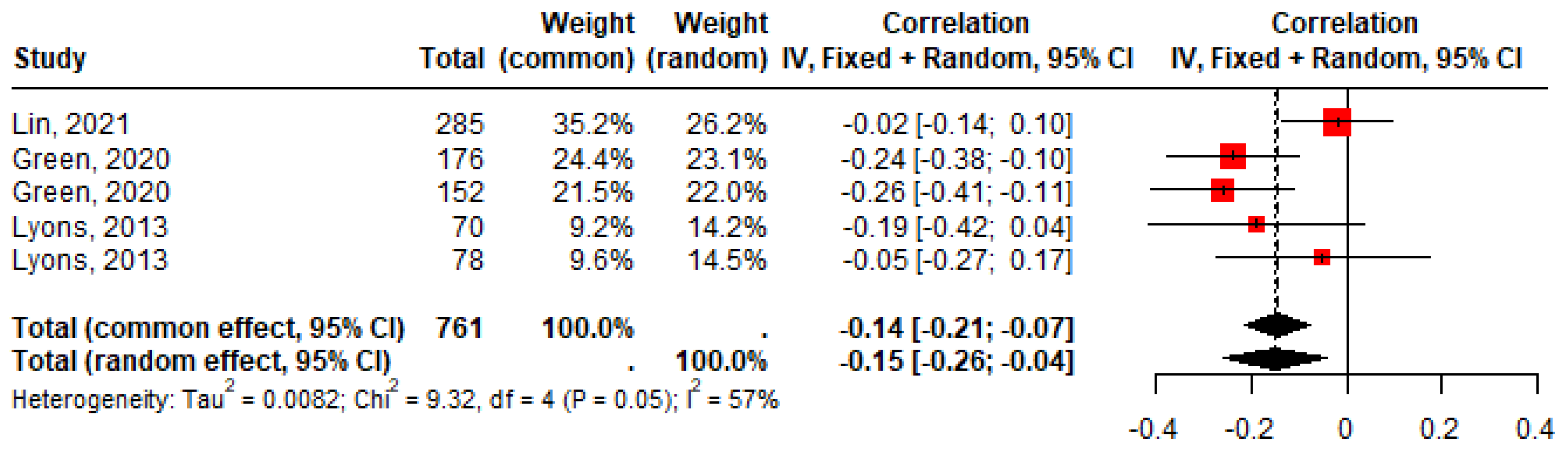

Regarding grandiose narcissism, five studies each were identified examining the correlation between maternal and paternal authoritative parenting, cf.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. Upon further analysis, significant heterogeneity was found in these studies. Specifically, the studies focusing on maternal authoritative parenting reveal high heterogeneity (Q(761) = 31.85,

p < 0.0001,

= 87.4%), whereas studies focusing on paternal authoritative parenting show moderate heterogeneity (Q(761) = 9.32,

p < 0.0001,

= 57.1%).

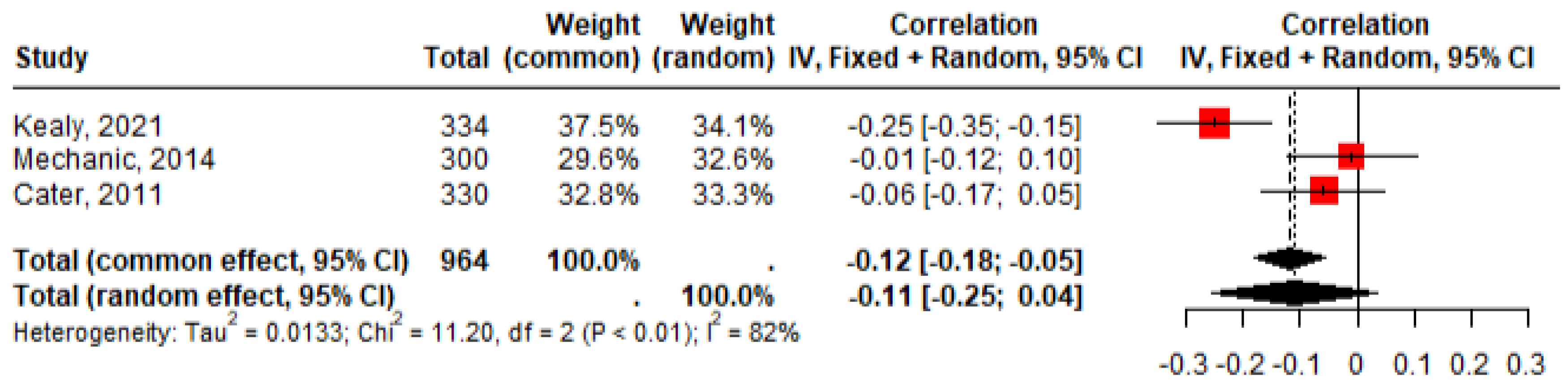

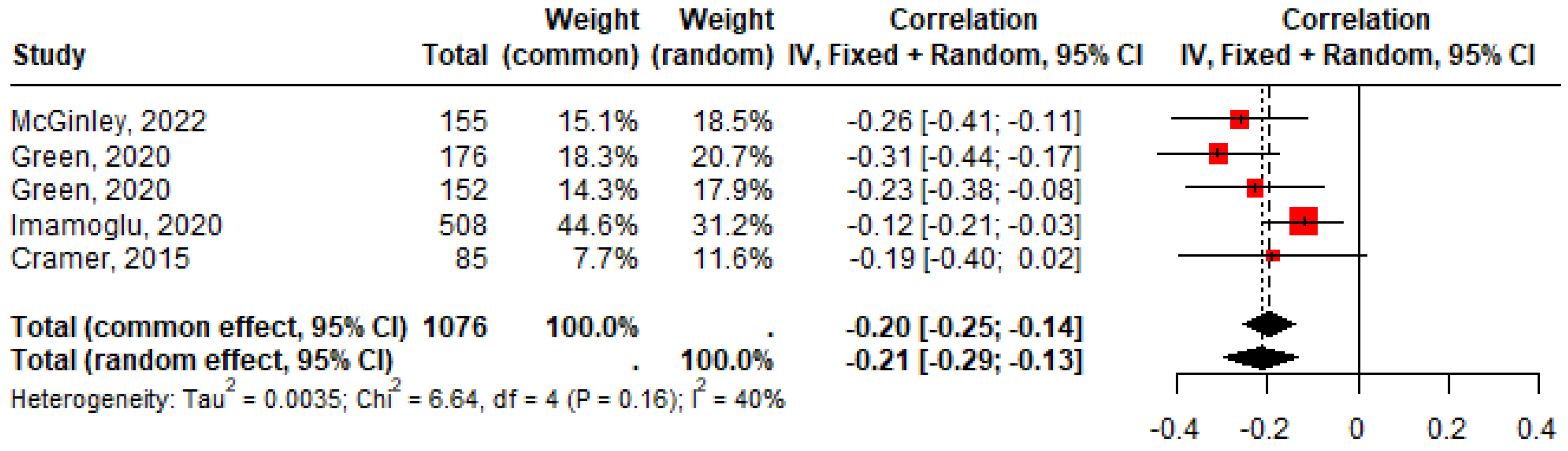

In the context of vulnerable narcissism, three studies examined overall authoritative parenting, while five studies each focused on maternal and paternal authoritative parenting. Forest plots summarizing the findings are shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. Once again, the heterogeneity remains significant for both maternal (Q(1076) = 25.04,

p < 0.0001,

= 84%) and overall authoritative parenting (Q(1076) = 11.20,

p = 0.0037,

= 82.1%), while paternal authoritative parenting shows moderate heterogeneity (Q(1076) = 6.64,

p = 0.1564,

= 39.7%).

A closer examination of these specific types of narcissism reveals different patterns in the data. It is noteworthy that while maternal authoritative parenting shows no significant correlation with grandiose narcissism, paternal authoritative parenting exhibits a negative correlation, suggesting the potential for an inverse relationship (mother: -0.06, CI 95% [-0.2510; 0.1329]; father: -0.15, CI 95% [-0.2603; -0.0434]).

For vulnerable narcissism, although the intervals indicate that there is no statistically significant correlation with authoritative parenting (-0.11, CI 95% [-0.2529; 0.0360]), when looking for maternal and paternal influences (mother: -0.28, CI 95% [-0.4046; -0.1521]; father: -0.21, CI 95% [-0.2931; -0.1316]), the negative correlations observed imply that authoritative parenting may be inversely related to vulnerable narcissism.

Funnel plots reveal symmetrical patterns for the analyses of both grandiose (mother and father) and vulnerable narcissism (overall parenting), cf.

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6 in

Appendix C. However, for maternal and paternal influences on vulnerable narcissism, the plots indicate two missing studies each, cf.

Figure A7 and

Figure A8 in

Appendix C. Despite these findings, there is no evidence of publication bias in the analyses according to

p-values from the Egger’s tests for funnel plot asymmetry, well above 0.05 (grandiose narcissism: mother:

p = 0.724, father:

p = 0.9242; vulnerable narcissism: parenting:

p = 0.4534, mother:

p = 0.4423, father:

p = 0.7393), suggesting that the meta-analysis results are not significantly affected by publication bias.

4.2. Narcissism and Authoritarian Education

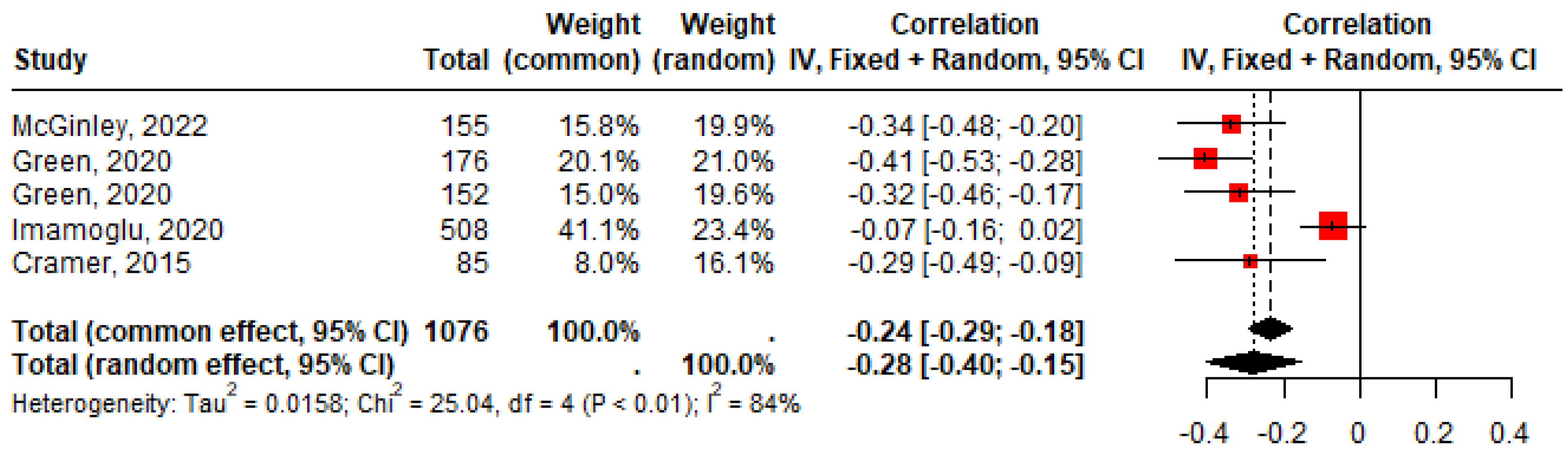

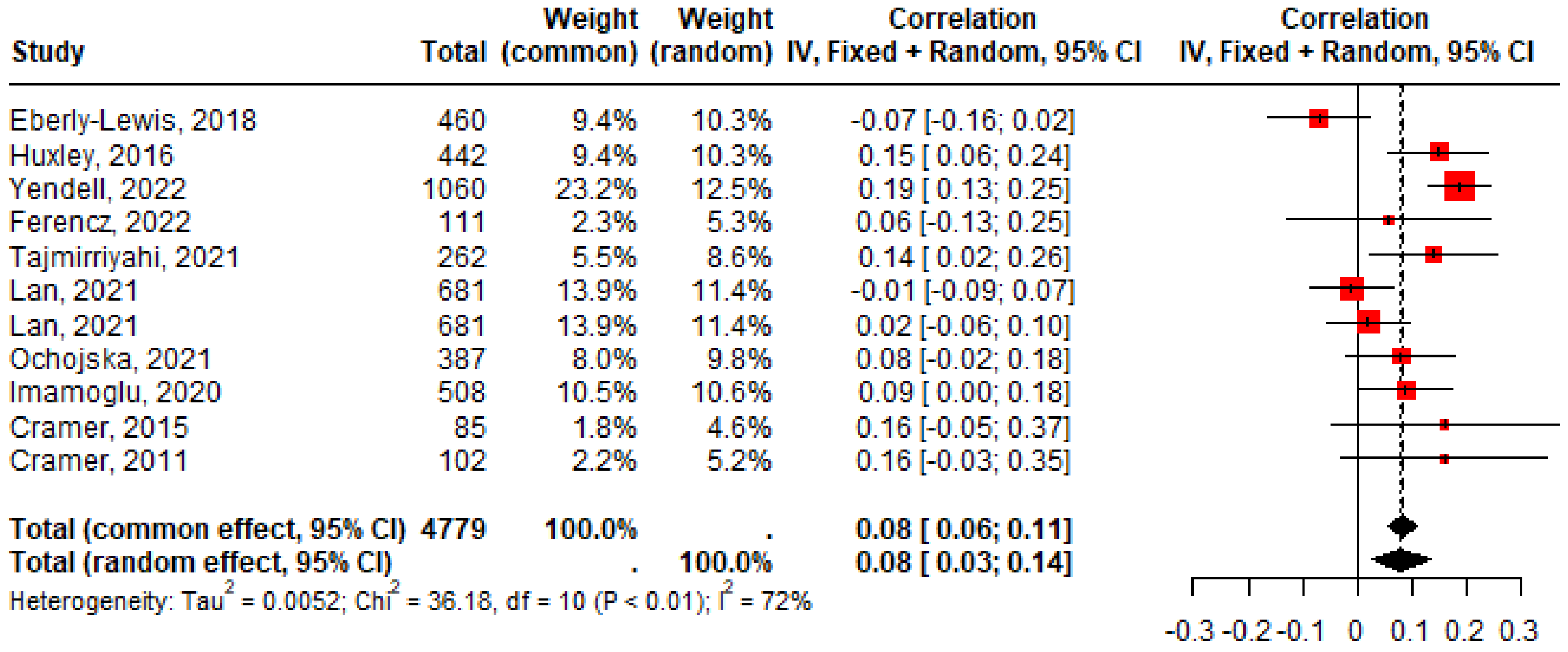

A total of 11 studies were used to examine the relationship between overall narcissism and both authoritarian maternal and paternal parenting styles. Furthermore, five studies each investigated the correlation between vulnerable narcissism and authoritarian parenting styles, including maternal and paternal influences.

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 present a summary of the findings in the form of forest plots.

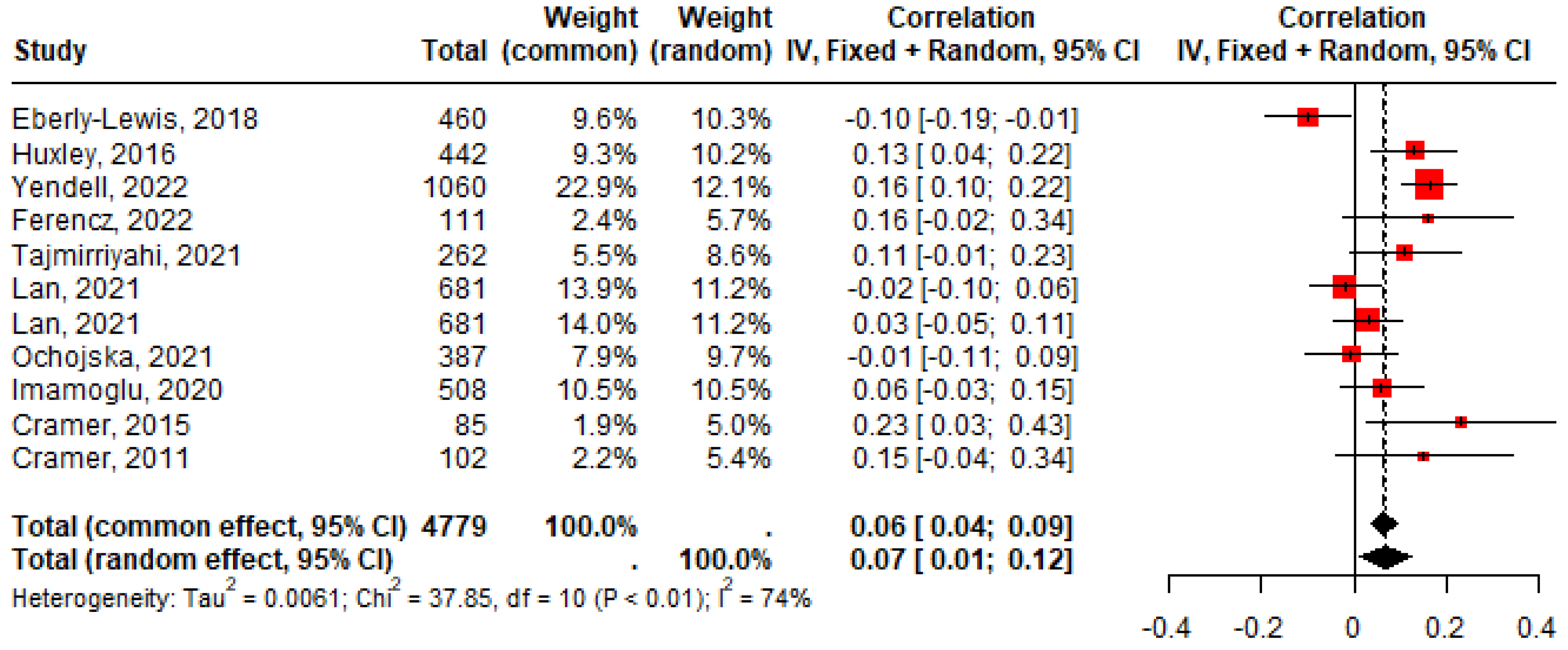

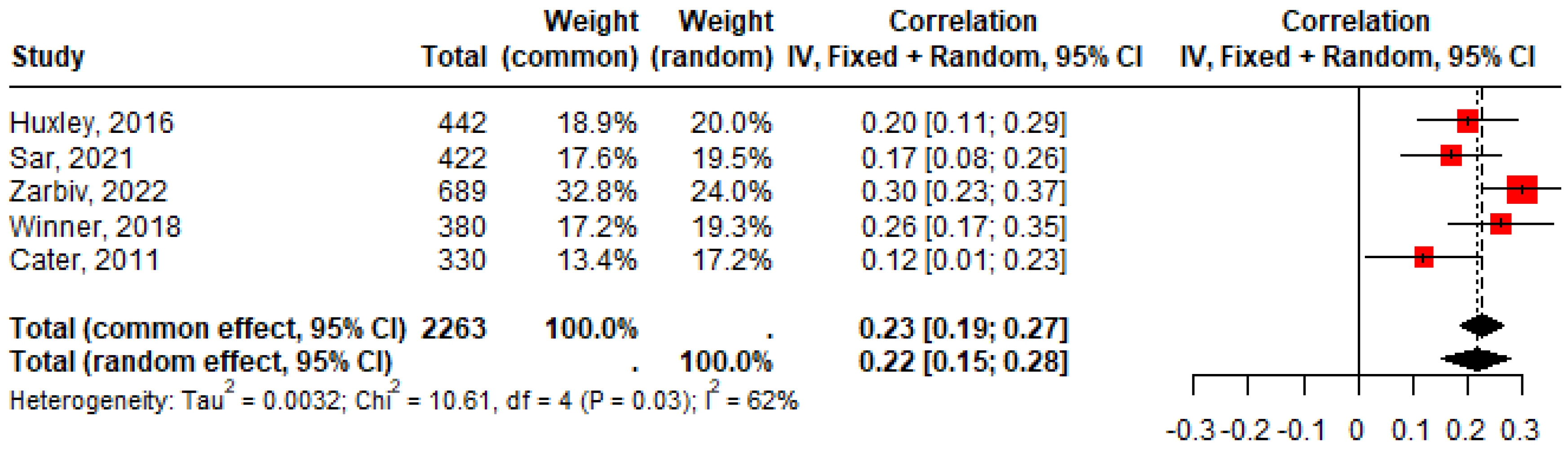

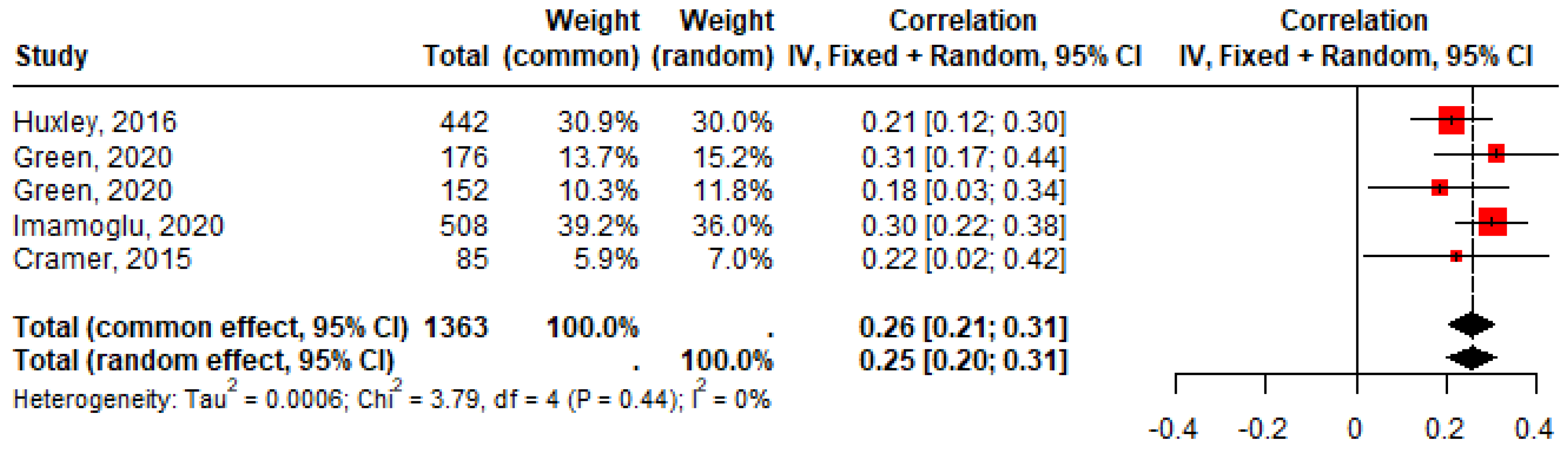

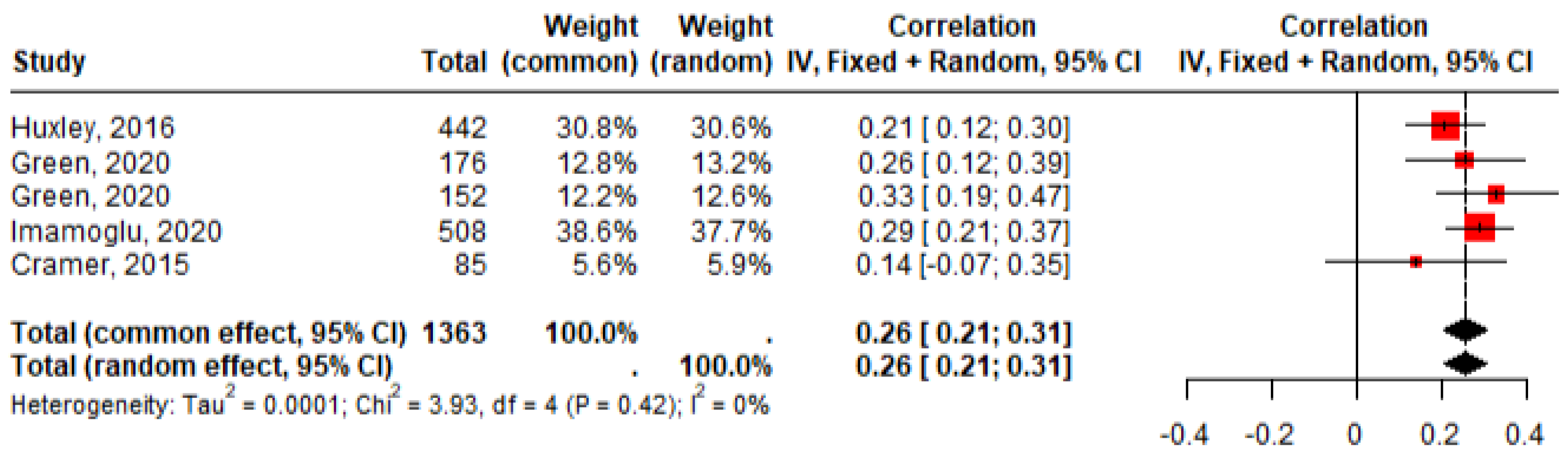

Despite the observed heterogeneity in studies analyzing the correlation between authoritarian parenting style and overall narcissism, this heterogeneity revealed to be not significant when focusing on maternal and paternal education (mother: Q(4779) = 36.18, p < 0.0001; father: Q(4779) = 37.85, p < 0.0001) and in relation to vulnerable narcissism (parents: Q(2263) = 10.61, p = 0.0313; mother: Q(1363) = 3.79, p = 0.4354; father: Q(1363) = 3.93, p = 0.4150).

Results also showed that the magnitudes of heterogeneity were not large when considering overall narcissism and mother education ( = 72.4%) or father education ( = 73.6%), and when considering only vulnerable narcissism (parents: = 62.3%; mother: = 0%; father: = 0%). Therefore, a random-effects model was used to analyze the correlation between overall narcissism and mother and father education, as well as vulnerable narcissism and overall parenting. For the correlation between vulnerable narcissism and both mother and father influences, a fixed effects (common-effects) model was used.

The forest plot analysis clearly indicates a positive correlation between authoritarian parenting style and narcissism, with no difference between maternal and paternal education (mother: 0.08, CI 95% [0.0271; 0.1352]; father: 0.07, CI 95% [0.0107; 0.1247]), cf.

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

When comparing overall narcissism with vulnerable narcissism, it is observed that the

value decreases, indicating greater homogeneity of the data that point us to an even stronger correlation (0.22, CI 95% [0.1524; 0.2800]), again with no difference between maternal and paternal education (mother: 0.26, CI 95% [0.2070; 0.3062]; father: 0.26, CI 95% [0.2079; 0.3070]), cf.

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19.

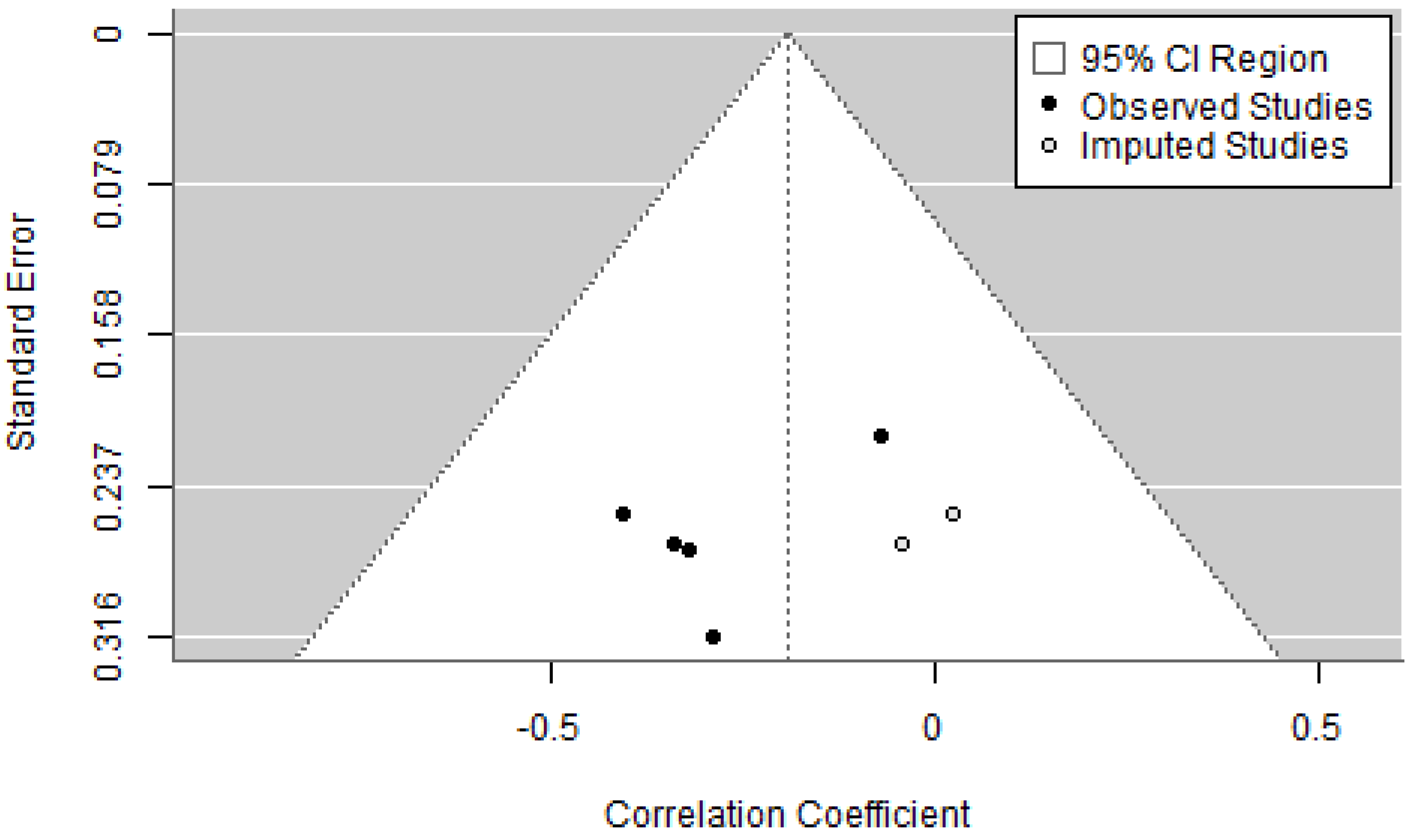

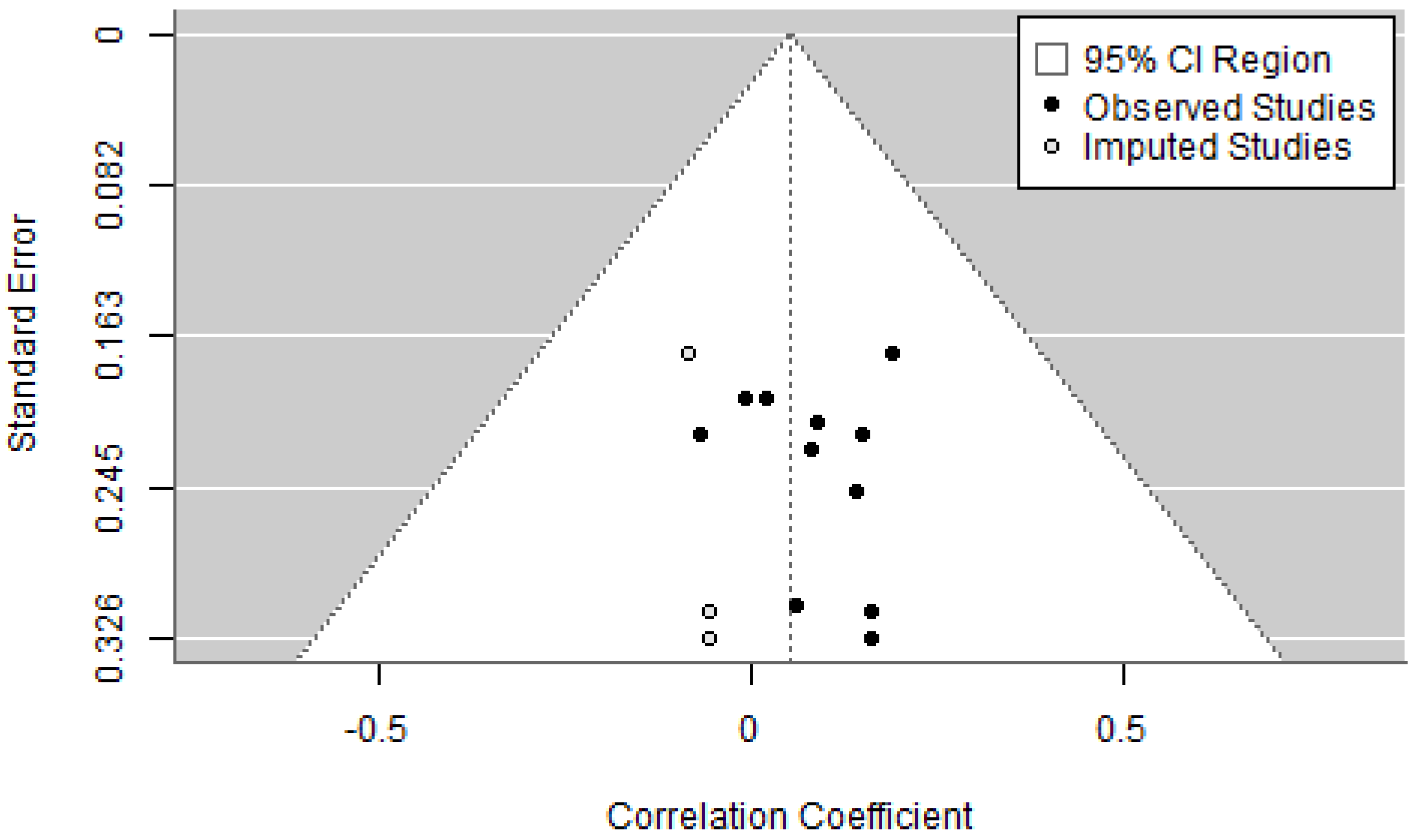

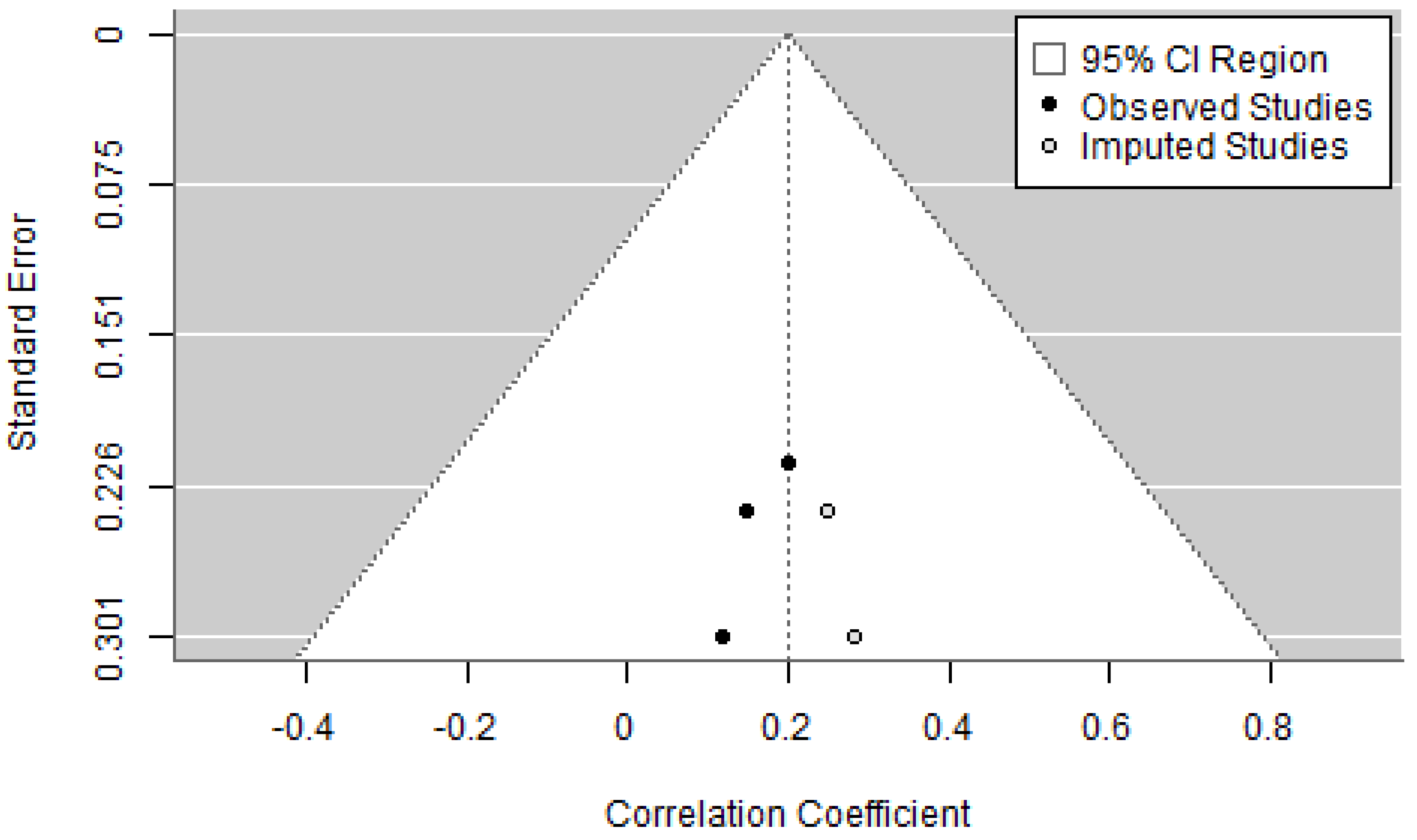

Although the funnel plots identify missing studies for the analyses of mother and father influences on overall narcissism, and for the analyses of overall parenting with vulnerable narcissism (cf.

Appendix C,

Figure A10,

Figure A11,

Figure A12,

Figure A13 and

Figure A14), there is no evidence of publication bias with observed regression test

p-values substantially higher than 0.05 (mother:

p = 0.8892; father:

p = 0.6535), vulnerable narcissism (parents:

p = 0.5602; mother:

p = 0.8658; father:

p = 0.8546).

4.3. Narcissism and Neglectful Education

In the context of the neglectful parenting style, a total of 5 studies investigated the relationship between maternal education and overall narcissism, while 6 studies focused on paternal influences. Additionally, 3 studies examined the correlation between neglectful parenting and vulnerable narcissism. Forest plots summarizing these findings are presented in

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

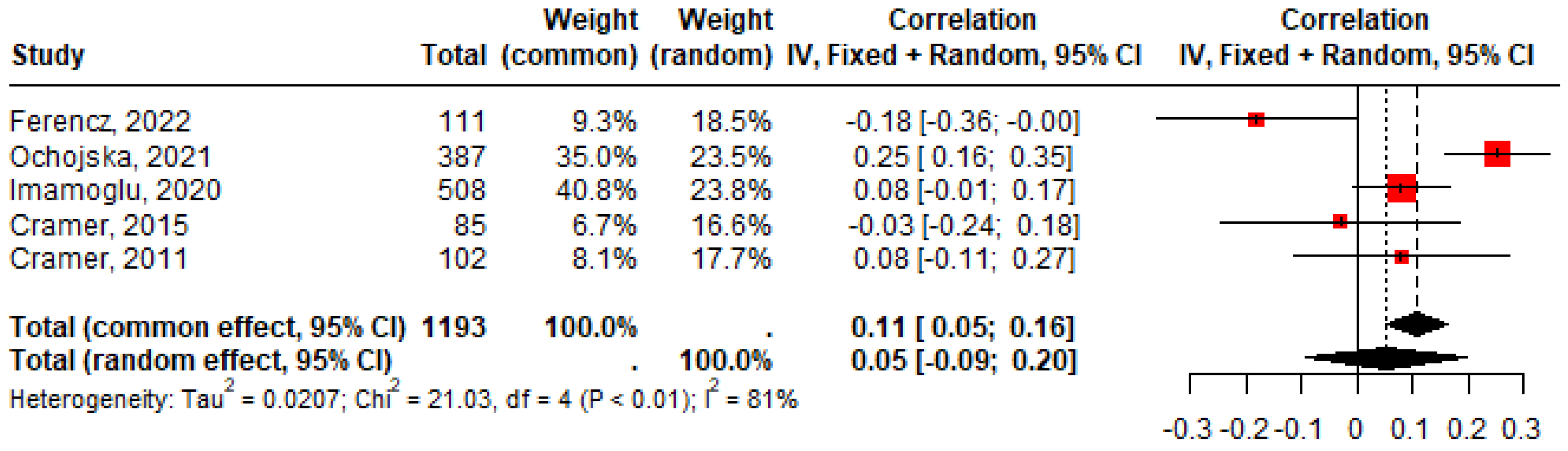

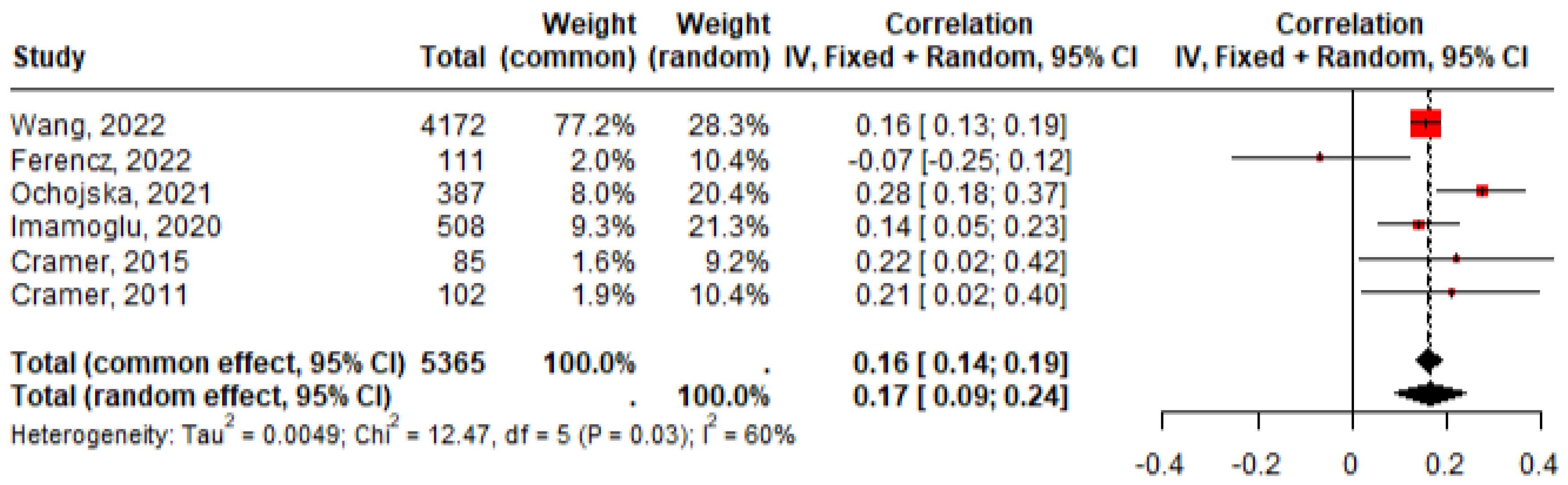

A more granular analysis distinguishing between maternal and paternal influences reveals persistent heterogeneity in studies focusing on maternal influences. Conversely, studies examining paternal influences display greater homogeneity (mother: Q(1193) = 21.03,

p = 0.0003,

= 81%; father: Q(5365) = 12.47,

p = 0.0289,

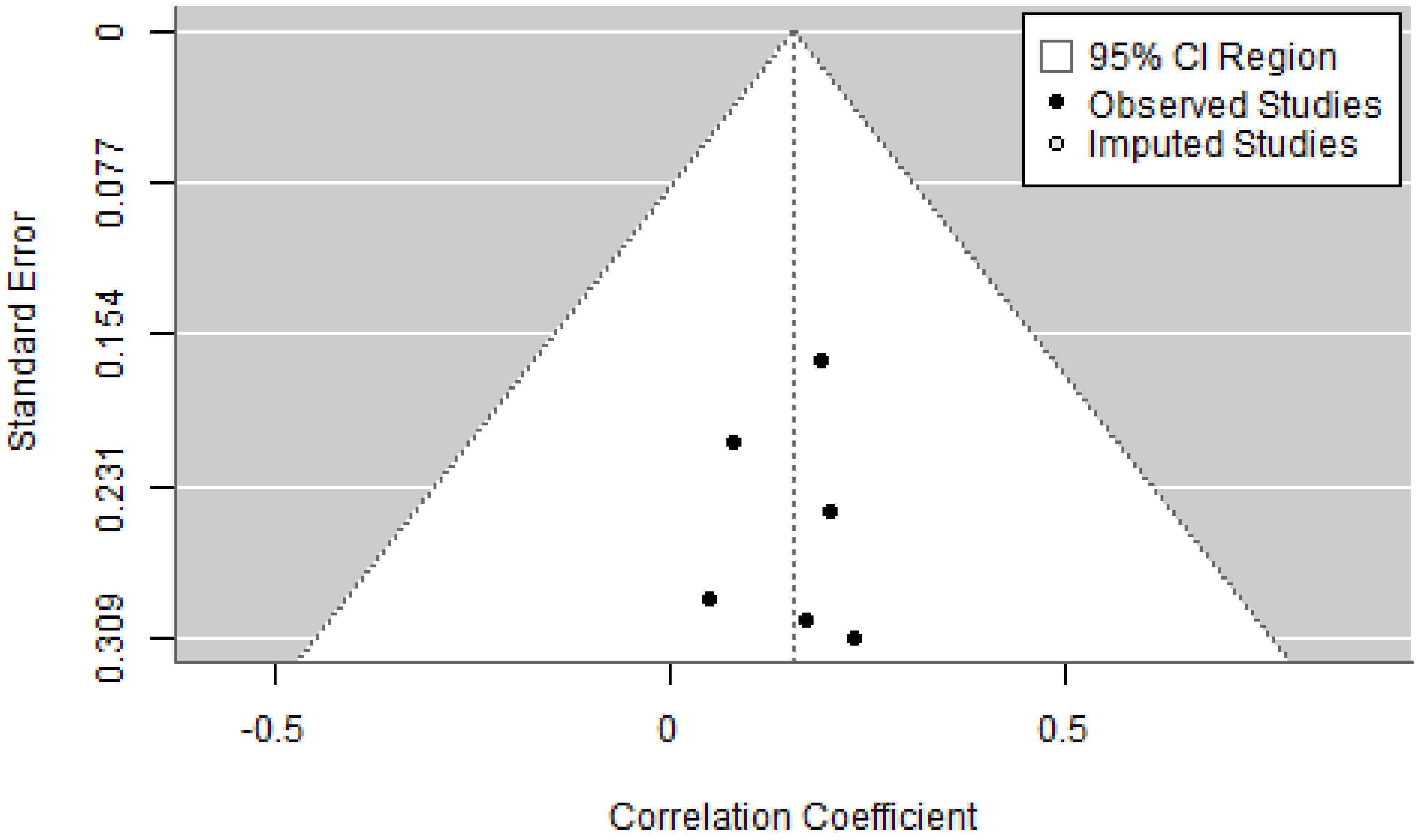

= 59.9%), with no evidence of publication bias (mother:

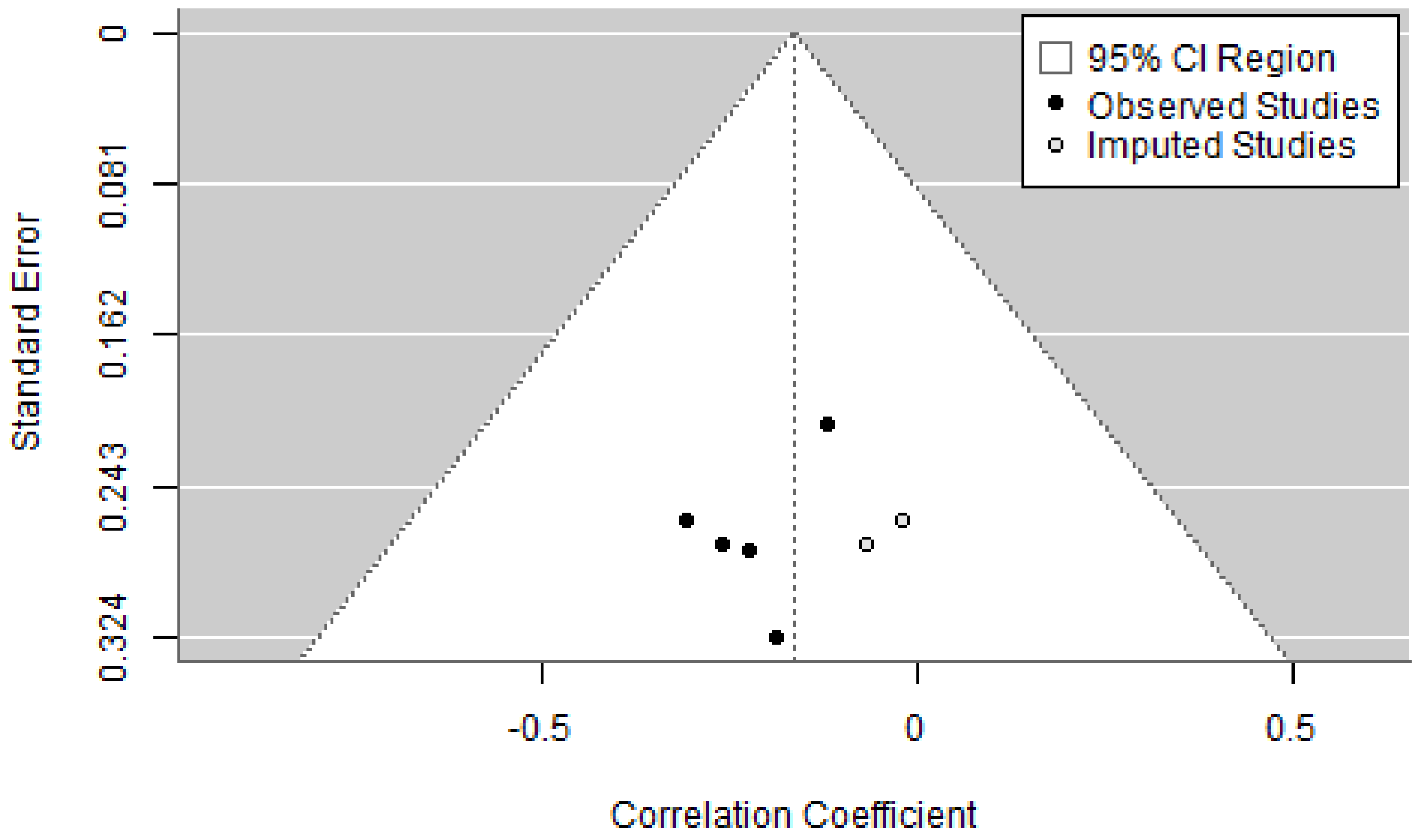

p = 0.4241; father:

p = 0.9341). The funnel plots summarizing these findings are presented in

Figure A16 and

Figure A17 in

Appendix C.

Analyzing the correlations, it is evident that for overall narcissism, the confidence intervals of the three estimates – overall parenting, maternal and paternal parenting – overlap, and the correlation with maternal education crosses zero, indicating a lack of significant correlation (0.05, CI 95% [-0.0901; 0.1980]). In contrast, a significant correlation is observed with paternal education (0.17, CI 95% [0.0910; 0.2400]), as

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 reveal.

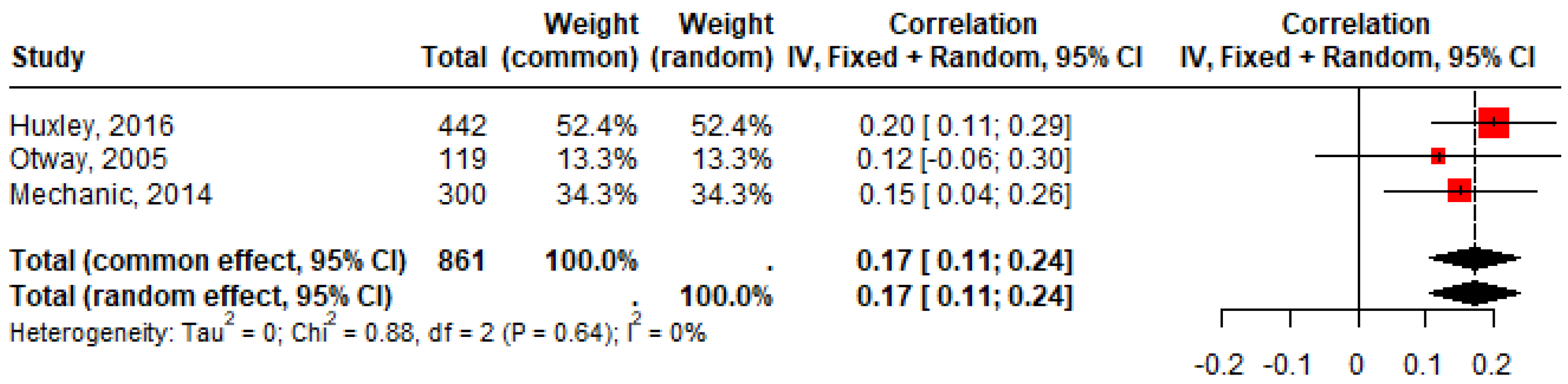

When comparing the studies of negligent parenting style with overall narcissism and with vulnerable narcissism, a notable reduction in the

value is observed (vulnerable narcissism:

= 0%), indicating increased data homogeneity, cf.

Figure 22.

The comparison between the correlations of the negligent parenting style with overall narcissism and vulnerable narcissism reveals that the relationship persists, with the correlation for vulnerable narcissism (0.17, CI 95% [0.11; 0.24]) having a higher estimate than that observed with overall narcissism (0.10, CI 95% [0.01; 0.19]). This raises the question of whether the negligent parenting style may not significantly influence grandiose narcissism, which could explain the high heterogeneity and weak correlations observed with overall narcissism.

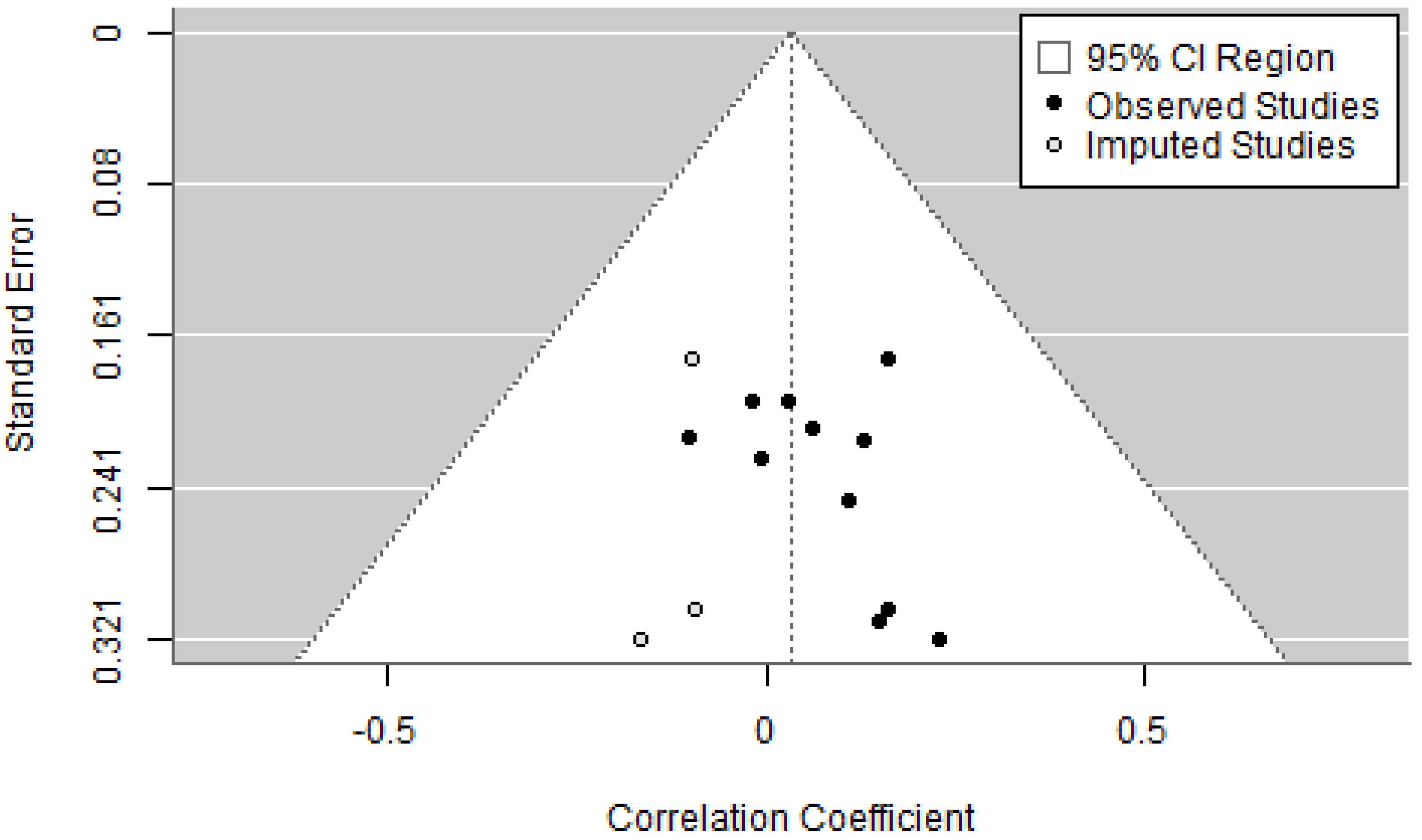

Similar to the findings for overall narcissism, the funnel plots for vulnerable narcissism, as shown in

Figure A18, also identify missing studies. However, the

p-value from the Egger’s tests for funnel plot asymmetry is above the 0.05 threshold, indicating no significant evidence of publication bias. This suggests that the correlation between negligent parenting and vulnerable narcissism is stronger than that with overall narcissism.

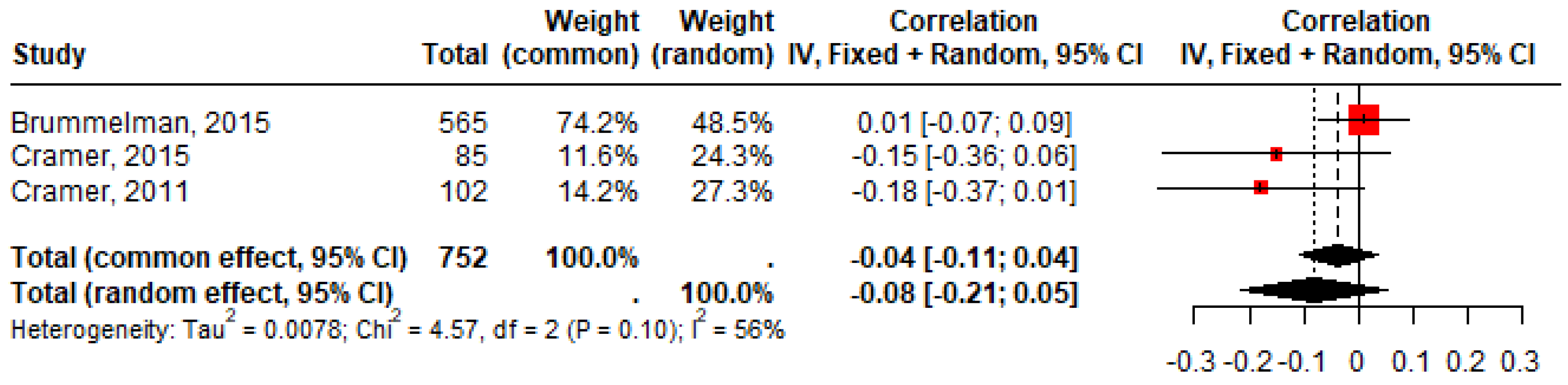

4.4. Narcissism and Permissive Education

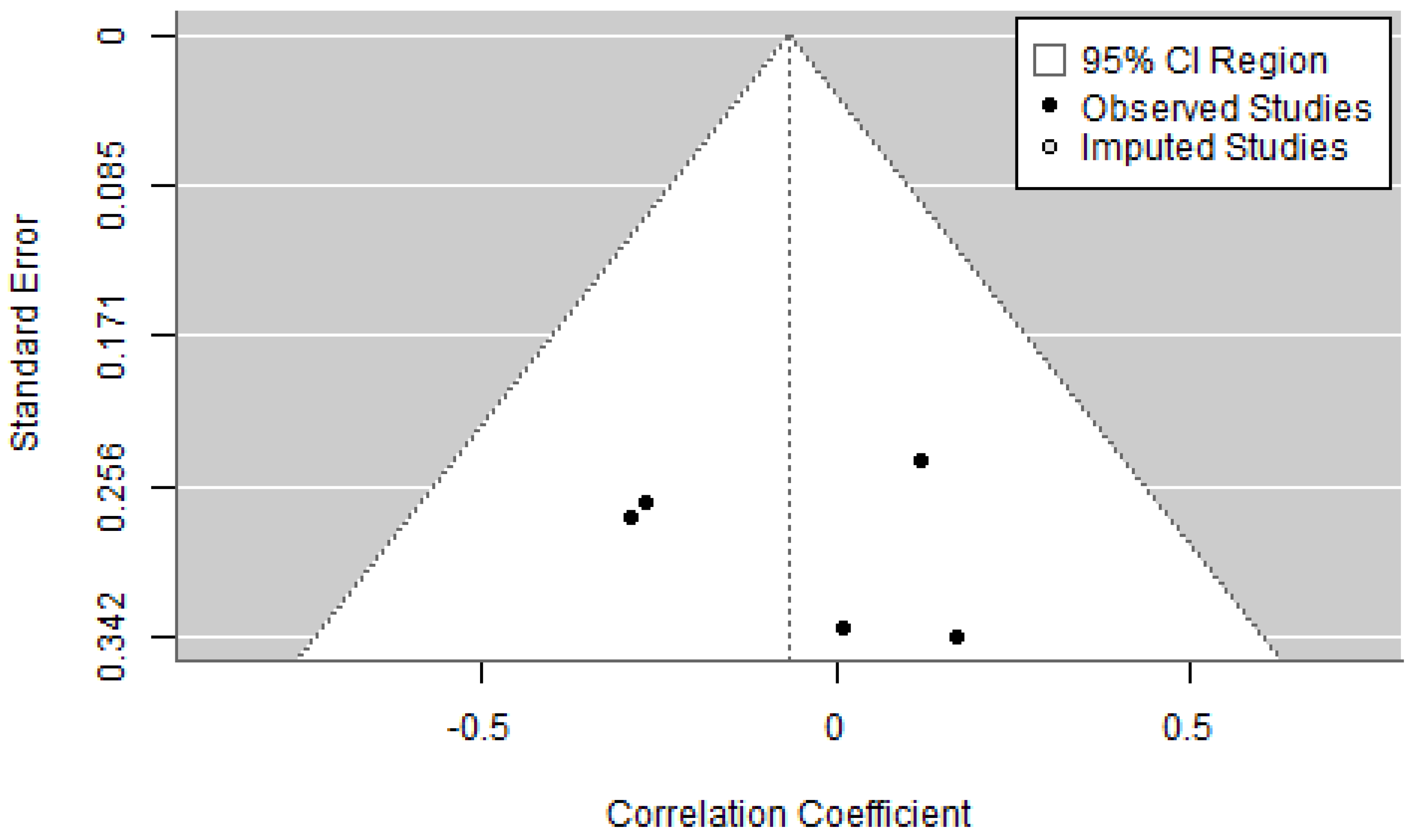

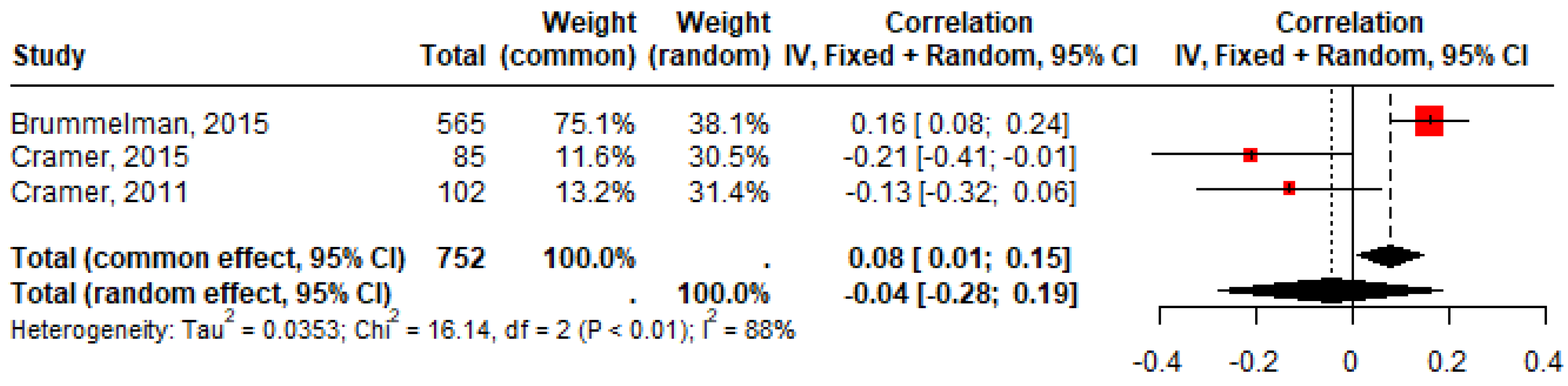

A total of three studies were identified examining the correlation between permissive parenting styles, both maternal and paternal, and overall narcissism. In contrast to other parenting styles, when the analysis of the permissive parenting style is narrowed down to distinguish between maternal and paternal influences, an increase in the value is observed, indicating greater heterogeneity in studies focusing on paternal influences (mother: Q(752) = 4.57, p = 0.1016, = 56.3%; father: Q(725) = 16.14, p = 0.0003, = 87.6%). Due to the high heterogeneity, a random-effects model was applied to better estimate the effect sizes.

Upon examining the correlations, it becomes evident that there is no significant correlation between permissive parenting, whether maternal or paternal, and narcissism (mother: -0.08, CI 95% [-0.2145; 0.0533]; father: -0.04, CI 95% [-0.2764; 0.1886]), as

Figure 23 and

Figure 24 reveal.

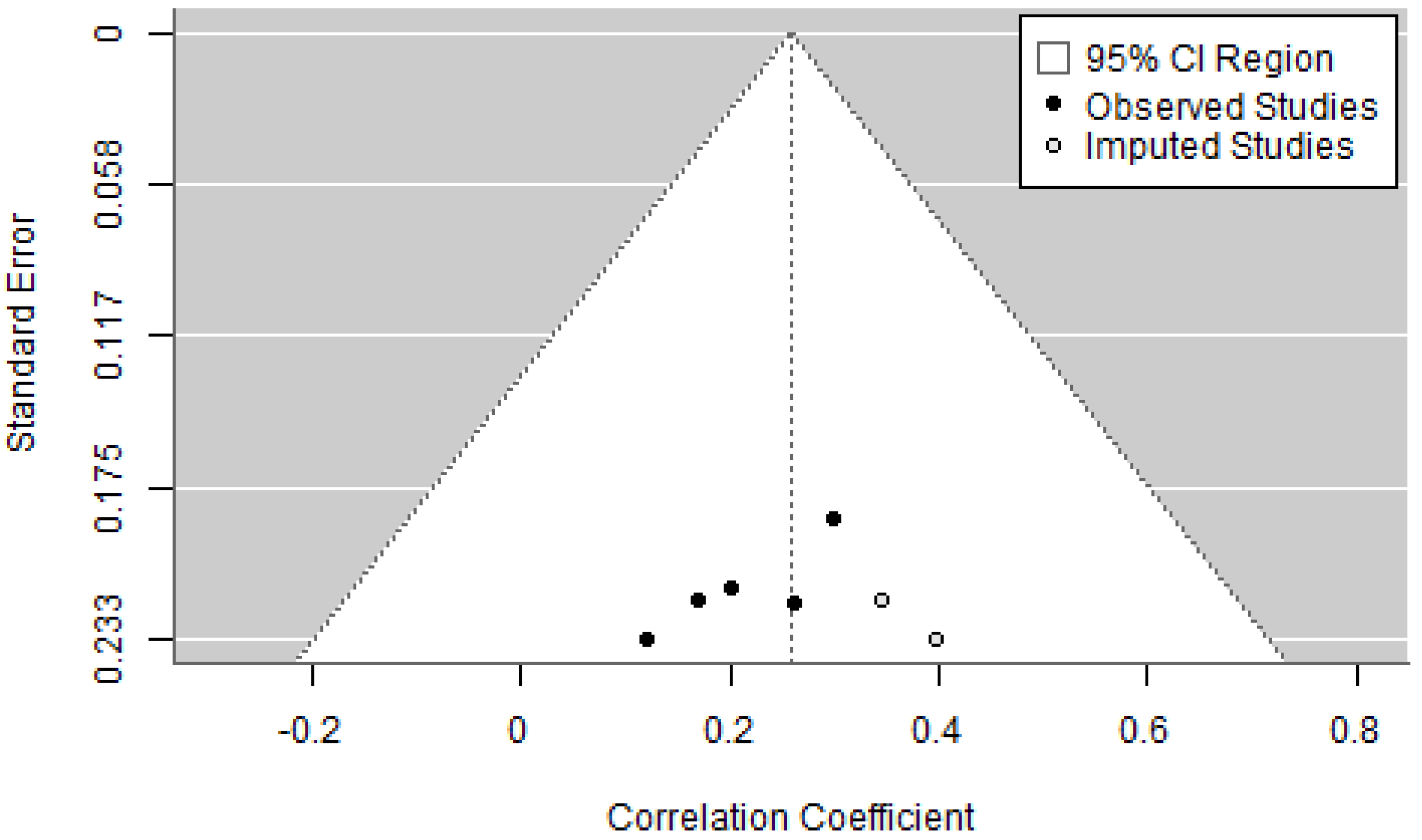

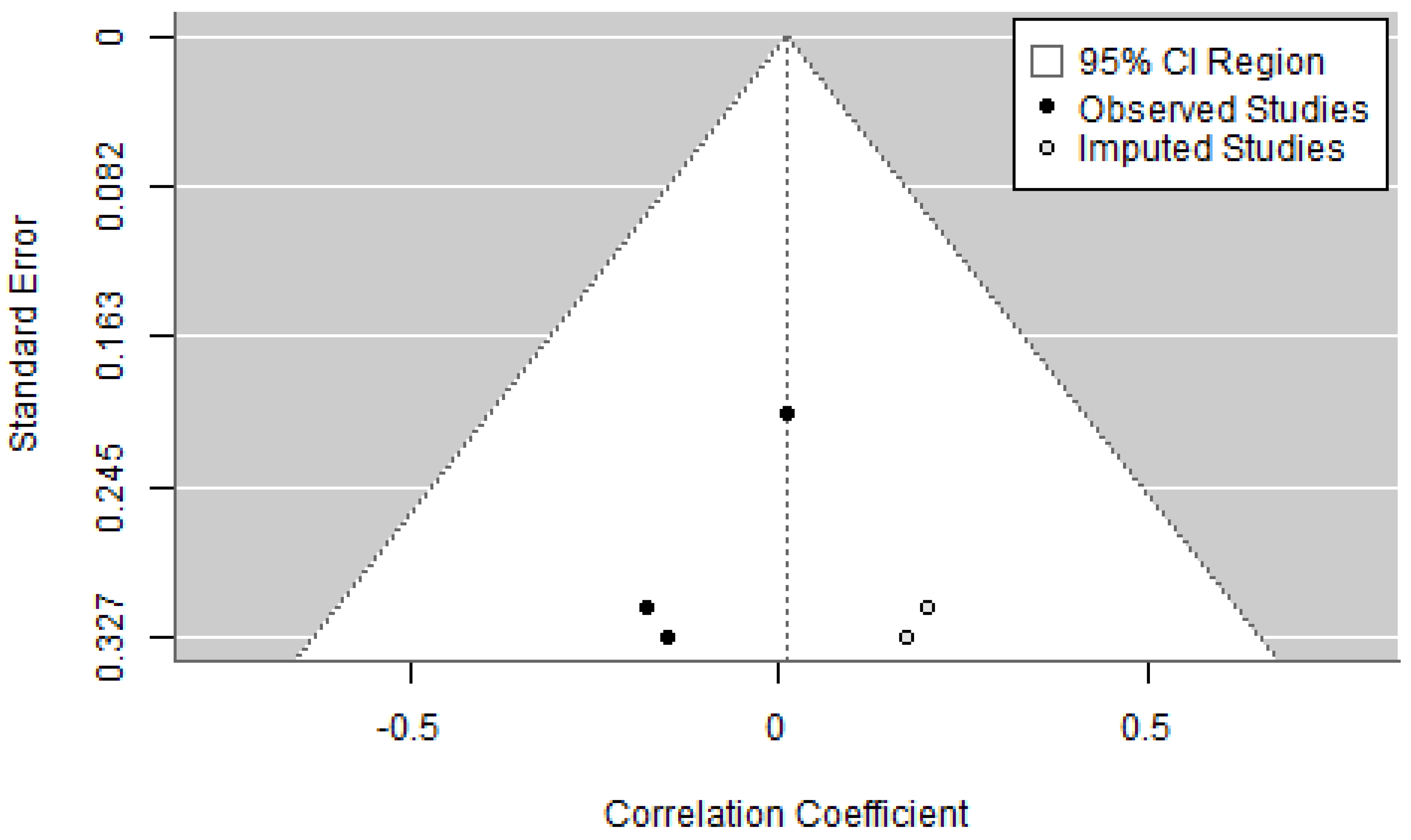

Additionally, there is no evidence of publication bias. Although the funnel plots identified missing studies (cf.

Appendix C,

Figure A20 and

Figure A21), the

p-value from Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry is above the 0.05 threshold (mother:

p = 0.57; father:

p = 0.2734), suggesting no significant bias. The results observed in the funnel plots may also be attributed to the small number of studies analyzed, specifically three.

5. Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis provide nuanced insights into the relationship between various parenting styles and the development of narcissistic traits, highlighting both the complexity of these relationships and the differential impacts of maternal and paternal influences.

Although the analysis reveals a significant correlation between overall narcissism and all four parenting styles, these correlations are weak, with estimates ranging between 0.08 and 0.15. At a preliminary analysis of the results between overall narcissism and each one of the parental styles, the overlapping confidence intervals observed in the forest plots indicate that the correlation values among the different parenting styles are comparable, thereby emphasizing the modest influence that parenting styles exert on the development of narcissistic traits [

49,

50,

51].

A closer examination of authoritative parenting reveals a more complex picture. The confidence intervals for the correlations between overall narcissism and both maternal and paternal authoritative parenting indicate no statistically significant association, suggesting that authoritative parenting, often characterized by a balanced approach of warmth and control, may not have a direct or strong influence on the emergence of narcissistic traits in children. However, when considering specific types of narcissism, such as grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, distinct patterns emerge. Notably, paternal authoritative parenting exhibits a negative correlation with grandiose narcissism, hinting at a potential inverse relationship. In contrast, maternal authoritative parenting shows no significant correlation, which may indicate that fathers may play a unique role in mitigating grandiose narcissistic tendencies through authoritative parenting.

Similarly, for vulnerable narcissism, although the overall correlations with authoritative parenting are not statistically significant, both maternal and paternal authoritative parenting exhibit negative correlations. These findings imply that authoritative parenting, particularly from mothers, may be inversely related to the development of vulnerable narcissism, suggesting a potential protective effect against this subtype of narcissism.

In contrast, the analysis of authoritarian parenting consistently reveals a significant and positive correlation with narcissism. This relationship persists regardless of whether the influence is maternal or paternal, with similar correlation estimates observed. Furthermore, the correlation between authoritarian parenting and vulnerable narcissism appears even higher, which reinforces the notion that an authoritarian parenting style, characterized by strict discipline and low warmth, is more strongly associated with the development of narcissistic traits, particularly vulnerable narcissism [

5,

49,

52] .

The examination of negligent parenting further supports the persistence of the relationship between this style and narcissism, particularly vulnerable narcissism. The higher correlation estimates for vulnerable narcissism compared to overall narcissism suggest that a neglectful parenting approach may have a more pronounced effect on the development of vulnerable narcissistic traits, potentially due to the lack of emotional support and guidance [

50,

51].

In contrast, the analysis of permissive parenting reveals no significant correlation with narcissism, whether maternal or paternal. The confidence intervals for maternal and paternal permissive parenting indicate the absence of a meaningful association, which suggests that this style may not significantly contribute to the development of narcissistic traits in children.

This meta-analysis, while providing valuable insights, was subject to some limitations that need to be acknowledged. One of the primary challenges was the heterogeneity observed across studies, coupled with the lack of sufficient data on grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, which highlights the limitations of the current evidence.

It also would be valuable to conduct more studies examining maternal and paternal influences to understand the distinct roles that each parent may play in the development of narcissistic characteristics.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis reveals a significant, though weak, correlation between parenting styles and narcissistic traits, with notable differences observed between maternal and paternal influences.

Authoritative parenting shows no significant relationship with overall narcissism, but paternal authoritative parenting is negatively correlated with grandiose narcissism, suggesting fathers may help mitigate these traits. In contrast, both maternal and paternal authoritative parenting exhibit negative correlations with vulnerable narcissism, indicating a potential protective effect. Authoritarian and neglectful parenting are more strongly associated with vulnerable narcissism, reinforcing the detrimental impact of low warmth and emotional neglect. Finally, permissive parenting shows no significant correlation with narcissism, indicating that a lack of discipline does not contribute notably to the development of narcissistic traits.

Despite the limitations of heterogeneity and insufficient data, the findings offer valuable insights into the interplay between parenting styles and narcissistic traits, providing directions for future theoretical models and clinical interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to clinical psychologists Dr. Marta Faustino and Dr. Brígida Ribeiro for their invaluable collaboration in this study. Their professional expertise and clinical insights were instrumental in enriching the practical aspects of the research and ensuring its depth and relevance.

Author Contributions

The article is a joint work of three authors who contributed equally to the final version of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially financed by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under the project UIDB/00006/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00006/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All analyzed data were obtained from the

PubMed and

Scopus platforms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADP |

Assessment of Personality Disorders Questionnaire |

| CAQ |

California Adult Q-Sort |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CNS |

Childhood Narcissism Scale |

| DTDD |

Dark Triad Dirty Dozen Scale |

| DSM |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| FFNI-SF |

Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory – Short Form |

| HSNS |

Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale |

|

statistic |

| NOS |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| NPI |

Narcissistic Personality Inventory |

| NPQ |

Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire |

| PDQ-4+ |

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire – 4th Edition Plus |

| PNI |

Pathological Narcissism Inventory |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO |

Prospective register for systematic review protocols |

|

Heterogeneity statistic Q

|

| SCID |

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders |

| SD3 |

Short Dark Triad |

| SD4 |

Short Dark Tetrad |

| SINS |

Single Item Narcissism Scale |

| YSQ-SF |

Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form |

Appendix A. Parental Education Studies Characteristics

Table A1.

Parental Education Studies Characteristic. Parental Education Studies Characteristics. Narc. Scale: Narcissism Scale; G: Grandiose Narcissism; V: Vulnerable Narcissism.

Table A1.

Parental Education Studies Characteristic. Parental Education Studies Characteristics. Narc. Scale: Narcissism Scale; G: Grandiose Narcissism; V: Vulnerable Narcissism.

| Study |

Country |

Sample |

Female |

Mean |

Narc. |

NOS |

| |

|

Size |

% |

Age |

Scale |

|

| [22] |

Pakistan |

100 |

87 |

|

PDQ |

7 |

| [14] |

Netherlands |

565 |

54 |

9.6 |

CNS |

10 |

| [53] |

|

330 |

83.9 |

21.6 |

PNI |

8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-V |

8 |

| [23] |

USA |

231 |

54.5 |

39.3 |

PDQ 4+ |

8 |

| [15] |

Italy |

519 |

52.4 |

9.7 |

CNS |

9 |

| [11] |

USA |

85 |

50.6 |

23 |

CAQ-13 |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

CAQ-13-V |

9 |

| [54] |

USA |

102 |

|

23 |

CAQ |

8 |

| [13] |

USA |

460 |

58.5 |

|

CNS |

10 |

| [55] |

Cyprus |

628 |

45.4 |

|

NPI-40 |

10 |

| [26] |

|

111 |

58.6 |

15.9 |

SD3 |

9 |

| [56] |

UK |

176 |

100 |

|

PNI-52-G |

8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-52-V |

8 |

| |

|

152 |

0 |

|

PNI-52-G |

8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-52-V |

8 |

| [57] |

China |

559 |

68.2 |

21.2 |

DTDD |

9 |

| [58] |

USA |

214 |

59.3 |

15.4 |

NPI-40 |

9 |

| [59] |

USA |

145 |

32,4 |

19.6 |

NPI-40 |

9 |

| [60] |

Australian |

442 |

68.1 |

25.6 |

PNI-52 |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-52-V |

9 |

| [35] |

Turkey |

508 |

53.3 |

31.2 |

PNI |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-V |

9 |

| [61] |

UK |

334 |

79.9 |

20.3 |

HSNS |

9 |

| [62] |

Iran |

278 |

|

|

NPI-16 |

8 |

| [63] |

China |

681 |

59 |

15.6 |

SD3-D |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

SD3-I |

9 |

| [21] |

China |

1173 |

53.7 |

14.8 |

NPQ |

10 |

| [64] |

China |

1533 |

55.1 |

15.3 |

SD3 |

9 |

| [65] |

Taiwan |

285 |

70.5 |

20.1 |

NPI-40 |

9 |

| [66] |

China |

530 |

82.3 |

18.8 |

DTDD |

8 |

| [67] |

UAE |

70 |

100 |

19.7 |

NPI-40 |

8 |

| |

UK |

78 |

|

21 |

|

|

| [68] |

USA |

599 |

76,5 |

22,3 |

PNI-52 |

9 |

| [69] |

USA |

155 |

66.7 |

19.3 |

PNI-28 |

8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-28-V |

8 |

| [70] |

|

300 |

14.3 |

16.6 |

PNI |

8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-V |

8 |

| [71] |

USA |

263 |

90 |

45 |

NPI-40 |

8 |

| [31] |

|

387 |

70.8 |

22.8 |

SCID |

9 |

| [72] |

UK |

119 |

50 |

28.8 |

NPI-40 |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

HSNS |

9 |

| [25] |

China |

1035 |

57.5 |

22.5 |

SD4 |

10 |

| [20] |

Turkey |

422 |

79.6 |

20.1 |

FFNI-SF |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

FFNI-SF-V |

9 |

| [73] |

USA |

653 |

69.5 |

20 |

PNI-52 |

10 |

| [18] |

Iran |

262 |

23.2 |

22.8 |

DTDD |

9 |

| [29] |

China |

4172 |

48 |

16.4 |

SINS |

9 |

| [74] |

|

380 |

78.9 |

20.1 |

PNI |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-V |

9 |

| [16] |

Germany |

1060 |

49 |

|

DDS |

9 |

| [75] |

Israel |

689 |

79 |

24.6 |

PNI-28 |

9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

PNI-28-V |

9 |

Appendix B. Adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for Parental Education Studies

Selection: (Maximum 5 stars)

Comparability: (Maximum 2 stars)

Outcome: (Maximum 3 stars)

Appendix C. Funnel Graphics for Parental Education Studies

Figure A1.

Authoritative Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.5533, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A1.

Authoritative Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.5533, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A2.

Authoritative Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.3003, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A2.

Authoritative Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.3003, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A3.

Authoritative Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.7393, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A3.

Authoritative Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.7393, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A4.

Authoritative Mother Grandiose. Egger’s test p-value=0.7240, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A4.

Authoritative Mother Grandiose. Egger’s test p-value=0.7240, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A5.

Authoritative Father Grandiose. Egger’s test p-value=0.9242, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A5.

Authoritative Father Grandiose. Egger’s test p-value=0.9242, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A6.

Authoritative Parenting Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.4534, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A6.

Authoritative Parenting Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.4534, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A7.

Authoritative Mother Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.4423, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A7.

Authoritative Mother Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.4423, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A8.

Authoritative Father Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.7393, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A8.

Authoritative Father Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.7393, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A9.

Authoritarian Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.7727, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A9.

Authoritarian Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.7727, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A10.

Authoritarian Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.8892, Trim and fill method: 3 missing studies

Figure A10.

Authoritarian Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.8892, Trim and fill method: 3 missing studies

Figure A11.

Authoritarian Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.6535, Trim and fill method: 3 missing studies

Figure A11.

Authoritarian Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.6535, Trim and fill method: 3 missing studies

Figure A12.

Authoritarian Parenting Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.5602, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A12.

Authoritarian Parenting Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.5602, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A13.

Authoritarian Mother Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.8658, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A13.

Authoritarian Mother Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.8658, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A14.

Authoritarian Father Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.8546, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A14.

Authoritarian Father Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.8546, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A15.

Neglectful Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.2736, Trim and fill method: 4 missing studies

Figure A15.

Neglectful Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.2736, Trim and fill method: 4 missing studies

Figure A16.

Neglectful Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.4241, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A16.

Neglectful Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.4241, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A17.

Neglectful Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.9341, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A17.

Neglectful Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.9341, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A18.

Neglectful Parenting Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.8289, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A18.

Neglectful Parenting Vulnerable. Egger’s test p-value=0.8289, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A19.

Permissive Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.9582, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A19.

Permissive Parenting Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.9582, Trim and fill method: no missing studies

Figure A20.

Permissive Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.5700, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A20.

Permissive Mother Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.5700, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A21.

Permissive Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.2734, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

Figure A21.

Permissive Father Overall. Egger’s test p-value=0.2734, Trim and fill method: 2 missing studies

References

- Vater, A.; Moritz, S.; Roepke, S. Does a narcissism epidemic exist in modern western societies? Comparing narcissism and self-esteem in East and West Germany. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.J. Are we becoming more narcissistic? Website, 2021. https://www.sciencefocus.com/news/are-we-becoming-more-narcissistic.

- Jauk, E.; Kanske, P. Can neuroscience help to understand narcissism? A systematic review of an emerging field. Personality Neuroscience 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.); American Psychiatric Association, 2013. https://archive.org/details/APA-DSM-5/page/671/mode/2up.

- Kernberg, O. Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism; Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2004. https://archive.org/details/borderlinecondit00kern.

- Clemens, V.; Fegert, J.M.; Allroggen, M. Adverse childhood experiences and grandiose narcissism – Findings from a population-representative sample. Child Abuse & Neglect 2022, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawn, K.P.; Keller, P.S.; Widige, T.A. Parent Grandiose Narcissism and Child Socio-Emotional Well Being: The Role of Parenting. Sage Journals 2023, 0, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.; Price, J.; Gentile, B.; Lynam, D.R.; Campbell, W.K. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism from the perspective of the interpersonal circumplex. Personality and Individual Differences 2012, 53, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Solutions. Narcissistic Personality Inventory-40 (NPI-40), 2024. https://www.statisticssolutions.com/free-resources/directory-of-survey-instruments/narcissistic-personality-inventory-40-npi-40/.

- Gentile, B.; Miller, J.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Reidy, D.E.; Zeichner, A.; Campbell, W.K. A Test of Two Brief Measures of Grandiose Narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality Inventory–13 and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory–16. Psychological Assessment 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, P. Adolescent Parenting, Identification, and Maladaptive Narcissism. Psychoanalytic Psychology 2015, 32, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, K.; Sherman, R.A. The California Adult Q-Sort. Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences 2017. [CrossRef]

- Eberly-Lewis, M.B.; Vera-Hughes, M.; Coetzee, T.M. Parenting and Adolescent Grandiose Narcissism: Mediation through Independent Self-Construal and Need for Positive Approval. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 2018, 179, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummelman, E.; Thomaes, S.; Nelemans, S.A.; de Castro, B.O.; Overbeek, G.; Bushman, B.J. Origins of narcissism in children. PNAS 2015, 112, 3659–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, G.; Musso, P.; Buonanno, C.; Semeraro, C.; Iacobellis, B.; Cassibba, R.; Levantini, V.; Masi, G.; Thomaes, S.; Muratori, P. The Apple of Daddy’s Eye: Parental Overvaluation Links the Narcissistic Traits of Father and Child. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yendell, A.; Clemens, V.; Schuler, J.; Decker, O. What makes a violent mind? The interplay of parental rearing, dark triad personality traits and propensity for violence in a sample of German adolescents. PLOS ONE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guoa, J.; Zhangb, J.; Panga, W. Parental warmth, rejection, and creativity: The mediating roles of openness and dark personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmirriyahi, M.; Doerfler, S.M.; Najafi, M.; Hamidizadeh, K.; Ickes, W. Dark Triad traits, recalled and current quality of the parent-child relationship: A non-western replication and extension. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Rodgers, S.; Müller, M.; Rossler, W. Childhood adversity in association with personality disorder dimensions: New findings in an old debate. European Psychiatry 2013, 28, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şar, V.; Türk-Kurtça, T. The Vicious Cycle of Traumatic Narcissism and Dissociative Depression Among Young Adults: A Trans-Diagnostic Approach. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y. Early material parenting and adolescents’ materialism: the mediating role of overt narcissism. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 10543–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, N.; Shehzadi, H.; Riaz, M.N.; Riaz, M.A. Paternal malparenting and offspring personality disorders: Mediating effect of early maladaptive schemas. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2017, 67, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.J.; Tanis, T.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Nesci, C.; Halmi, W.; Galynker, I. Are there differential relationships between different types of childhood maltreatment and different types of adult personality pathology? Psychiatry Research 2014, 215, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PsycNet, A. Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire – 4+, 2024. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft07759-000.

- Ren, M.; Zou, S.; Ding, S.; Ding, D. Childhood Environmental Unpredictability and Prosocial Behavior in Adults: The Effect of Life-History Strategy and Dark Personalities. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2022, 15, 1757–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencz, T.; Láng, A.; Kocsor, F.; Kozma, L.; Babós, A.; Gyuris, P. Sibling relationship quality and parental rearing style infuence the development of Dark Triad traits. Current Psychology 2022, 42, 24764–24781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakr, Z.; Fatahi, N. Risk-taking Behaviour: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Impulsivity, Sensation Seeking and Adverse Childhood Experience. Acta Informatica Medica 2023, 31, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilleira, M.P.; Rodicio-García, M.L.; de Deus, M.P.R.; del Hierro, T.A. Adaptation of the Short Dark Triad (SD3) to Spanish Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hu, H.; Mo, P.K.H.; Ouyang, M.; Geng, J.; Zeng, P.; Mao, N. How is Father Phubbing Associated with Adolescents’ Social Networking Sites Addiction? Roles of Narcissism, Need to Belong, and Loneliness. The Journal of Psychology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PsycNet, A. Single Item Narcissism Scale, 2024. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft46661-000.

- Ochojska, D.; Pasternak, J. The selected psychosocial risk factors in the development of personality disorders in a group of Polish young adults. Journal of Psychopathology 2021, 27, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasofer, D.R.; Brown, A.J.; Riegel, M. Structured Clinical Interviewfor DSM-IV (SCID). Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PsycNet, A. Young Schema Questionnaire–Short Form, 2024. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft12644-000.

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Gamez-Guadix, M. Predictors of Child-to-Parent Aggression: A 3-Year Longitudinal Study. Developmental Psychology 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamoglu, A.H.; Batigun, A.D. The assessment of the relationship between narcissism, perceived parental rearing styles, and defense mechanisms. Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020, 33, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M.E. Schema theraphy: a practitioner’s guide; The Guilford Press, Inc., 2003. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-00629-000.

- Baumrind, D. Current Patterns of Parental Authority. Developmental Psychology 1971, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Prisoners of Childhood; New York, N.Y.: Basic Books, 1981. https://www.alice-miller.com/en/prisoners-of-childhood/.

- Winnicott, D.W. Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. The maturational processes and the facilitating environment: Studies in the theory of emotional development 1965, pp. 140–152. [CrossRef]

- Sanvictores, T.; Mendez, M.D. Types of parenting styles and effects on children; StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33760502/.

- George, C.; Solomon, J. Internal working models of caregiving and security of attachment at age six. Infant Mental Health Journal 1989, 10, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Thompson, R.A. Parent’s role in children’s personality development: The psychology resource principle. In Handbook of personality: Theory and research; New York, N.Y.: Basic Books, 1981. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-11667-013.

- Kernberg, P.F.; Weiner, A.S.; Bardenstein, K.K. Personality disorders in children and adolescents; New York, N.Y.: Basic Books, 2000. https://archive.org/details/personalitydisor0000kern.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, 2024. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Laliberté, E. Package ‘metacor’ Meta-Analysis of Correlation Coefficients. Website, 2019. http://download.nust.na/pub3/cran/web/packages/metacor/metacor.pdf.

- Brilhante, M. Uma Introdução à Meta-Análise Minicurso do XXIII Congresso; Sociedade Portuguesa de Estatística, 2017. https://www.spestatistica.pt/publicacoes/publicacao/uma-introducao-meta-analise.

- Shim, S.R.; Kim, S.J. Intervention meta-analysis: application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health 2019, p. 41.e2019008. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.; Steinmetz, H.; Block, J. How to conduct a meta-analysis in eight steps: a practical guide. Management Review Quarterly 2022, 72, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millon, T.; Grossman, S.; Millon, C.; Meagher, S.; Ramnath, R. Personality Disorders In Modern Life; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-18756-000.

- Kohut, H. The analysis of the self: A systematic approach to the psychoanalytic treatment of narcissistic personality disorders; International Universities Press, 1971. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-16139-000.

- Kohut, H. The restoration of the self; International Universities Press, 1977. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-16135-000.

- Zeigler-Hill, V.; Clark, C.B.; Pickard, J.D. Narcissistic Subtypes and Contingent Self-Esteem: Do All Narcissists Base Their Self-Esteem on the Same Domains? Journal of personality 2008, 76, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, T.E.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Vonk, J. Narcissism and recollections of early life experiences. Personality and Individual Differences 2011, 51, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, P. Young adult narcissism: A 20 year longitudinal study of the contribution of parenting styles, preschool precursors of narcissism, and denial. Journal of Research in Personality 2011, 45, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzand, M.; Cerkez, Y.; Baysen, E. Effects of Self-Concept on Narcissism: Mediational Role of Perceived Parenting. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; MacLean, R.; Charles, K. Recollections of Parenting Styles in The Development of Narcissism: The Role of Gender. Personality and Individual Differences 2020, 167, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Pang, W. Parental warmth, rejection, and creativity: The mediating roles of openness and dark personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.S.; Bleau, G.; Drwecki, B. Parenting Narcissus: What Are the Links Between Parenting and Narcissism? Journal of Personality 2006, 74, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.S.; Tritch, T. Clarifying the Links Between Grandiose Narcissism and Parenting. The Journal of Psychology 2014, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Huxley, E.; Bizumic, B. Parental Invalidation and the Development of Narcissism. The Journal of Psychology 2016, pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kealy, D.; Hewitt, P.L.; Cox, D.W.; Laverdière, O. Narcissistic vulnerability and the need for belonging: Moderated mediation from perceived parental responsiveness to depressive symptoms. Current Psychology 2021, 42, 2820–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidtalab, E.; Niknam, M. The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction in the Relationship Between Overparenting and Narcissism in Iranian College Students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology 2023, 29, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X. Disengaged and highly harsh? Perceived parenting profiles, narcissism, and loneliness among adolescents from divorced families. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yao, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H. Parent Autonomy Support and Psychological Control, Dark Triad, and Subjective Well-Being of Chinese Adolescents: Synergy of Variable- and Person-Centered Approaches. Journal of Early Adolescence 2020, 40, 966–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C. Parental attachment and dispositional gratitude: The mediating role of adaptive narcissism. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 16121–16130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Meng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D. Mediating Effect of Dark Triad Personality Traits on the Relationship Between Parental Emotional Warmth and Aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2021, 36, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, M.; Morgan, K.; Thomas, J.; Hashmi, A.A. Patterns of Parental Warmth, Attachment, and Narcissism in Young Women in United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom. Individual Differences Research 2013, 11, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, K.; Huprich, S. Retrospective reports of attachment disruptions, parental abuse and neglect mediate the relationship between pathological narcissism and self-esteem. Personality and Mental Health 2014, 8, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, M.; Muzzy, B.M.; Hermann, M.; Thompson, R.A. Secure attachment and social and personality outcomes: The moderating role of emerging adults’ autobiographical memories of parents. Review of Social Development 2022, pp. 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mechanic, K.L.; Barry, C.T. Adolescent Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism: Associations with Perceived Parenting Practices. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2015, 24, 1510–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Shaw, L. The aetiology of non-clinical narcissism: Clarifying the role of adverse childhood experiences and parental overvaluation. Personality and Individual Differences 2020, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otway, L.J.; Vignoles, V.L. Narcissism and childhood recollections: a quantitative test of psychoanalytic predictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2006, 32, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C.; Woszidlo, A.; Givertz, M.; Montgomery, N. Parent and Child Traits Associated with Overparenting. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2013, 32, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, N.A.; Nicholson, B.C. Overparenting and Narcissism in Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Psychological Control. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2018, 27, 3650–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbiv, B.; Goldner, L. Understanding PTSD Symptoms Resulting from Childhood Emotional Abuse and Boundary Dissolution: The Mediating Role of Narcissistic Pathology. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2022, 31, 1279–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram

Figure 2.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 2.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 3.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 3.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 4.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 4.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 5.

Forest Graphic Permissive Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 5.

Forest Graphic Permissive Parenting Overall Narcissism

Figure 6.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Parenting Overall Narcissism – with NOS score studies higher or equal to 8

Figure 6.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Parenting Overall Narcissism – with NOS score studies higher or equal to 8

Figure 7.

Forest Graphic Permissive Parenting Overall Narcissism – with NOS score studies higher or equal to 8

Figure 7.

Forest Graphic Permissive Parenting Overall Narcissism – with NOS score studies higher or equal to 8

Figure 8.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 8.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 9.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 9.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 10.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Mother Grandiose Narcissism

Figure 10.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Mother Grandiose Narcissism

Figure 11.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Father Grandiose Narcissism

Figure 11.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Father Grandiose Narcissism

Figure 12.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Parenting Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 12.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Parenting Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 13.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Mother Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 13.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Mother Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 14.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Father Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 14.

Forest Graphic Authoritative Father Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 15.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 15.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 16.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 16.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 17.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Parenting Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 17.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Parenting Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 18.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Mother Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 18.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Mother Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 19.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Father Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 19.

Forest Graphic Authoritarian Father Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 20.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 20.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 21.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 21.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 22.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Parenting Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 22.

Forest Graphic Neglectful Parenting Vulnerable Narcissism

Figure 23.

Forest Graphic Permissive Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 23.

Forest Graphic Permissive Mother Overall Narcissism

Figure 24.

Forest Graphic Permissive Father Overall Narcissism

Figure 24.

Forest Graphic Permissive Father Overall Narcissism

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).