Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

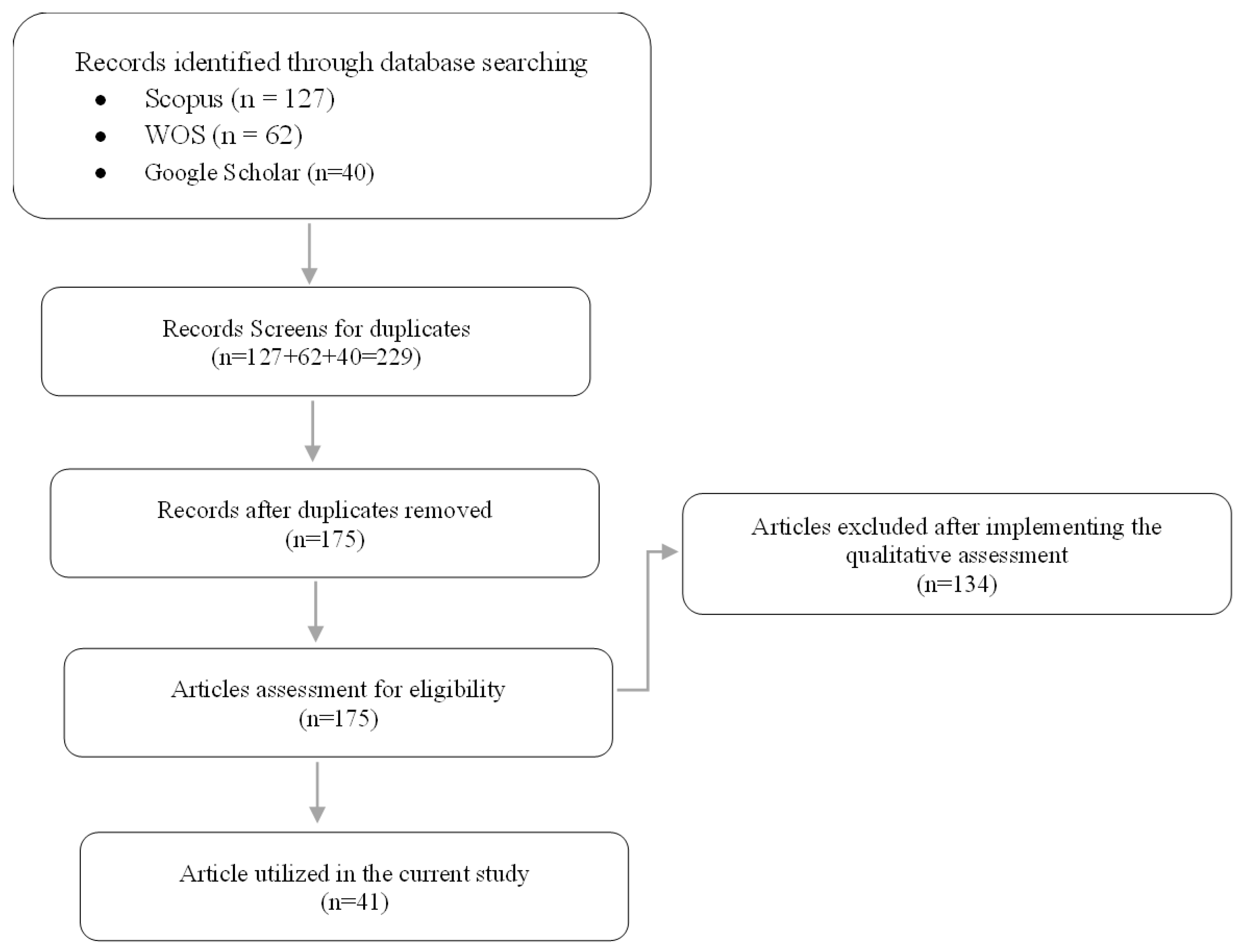

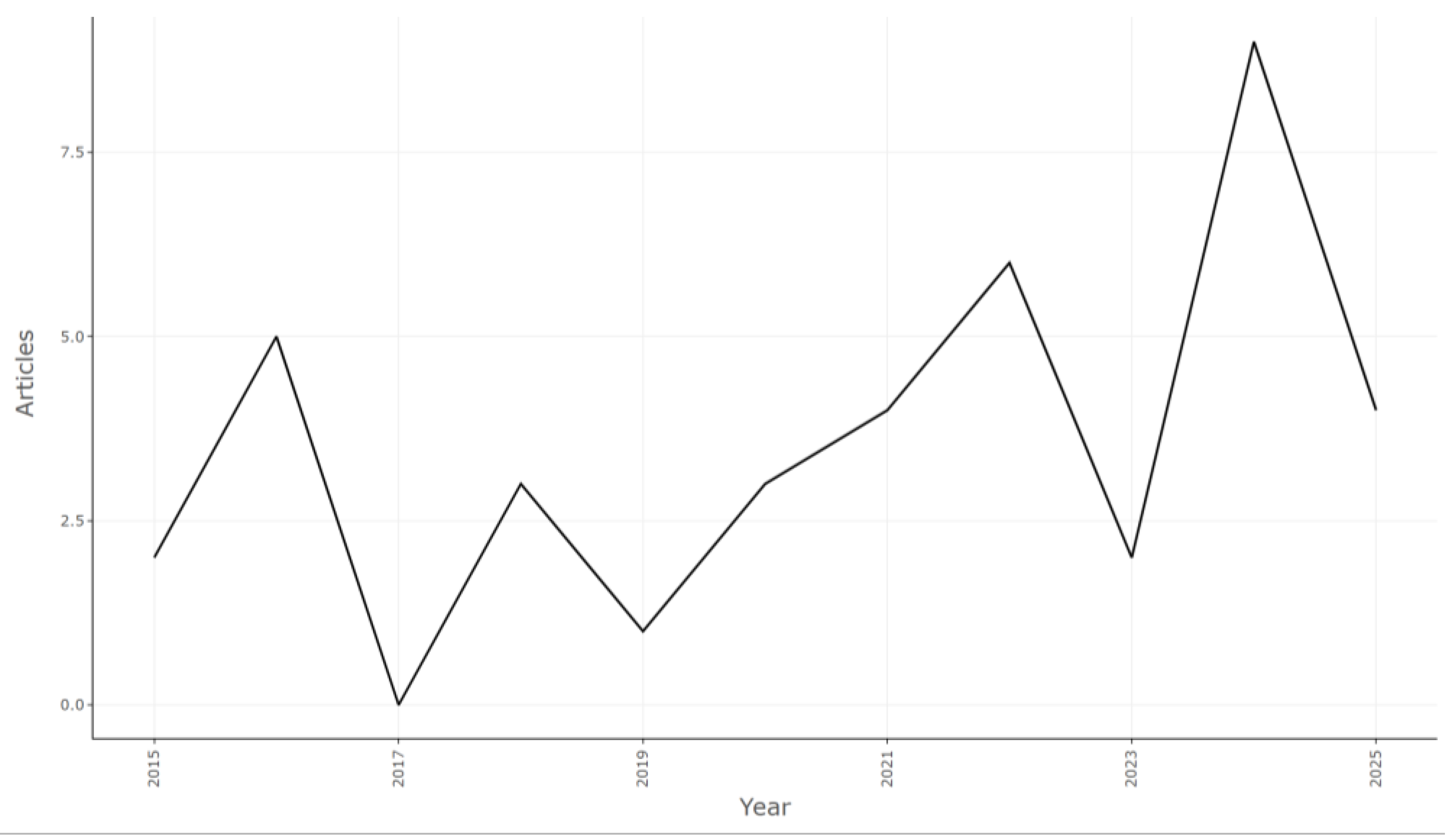

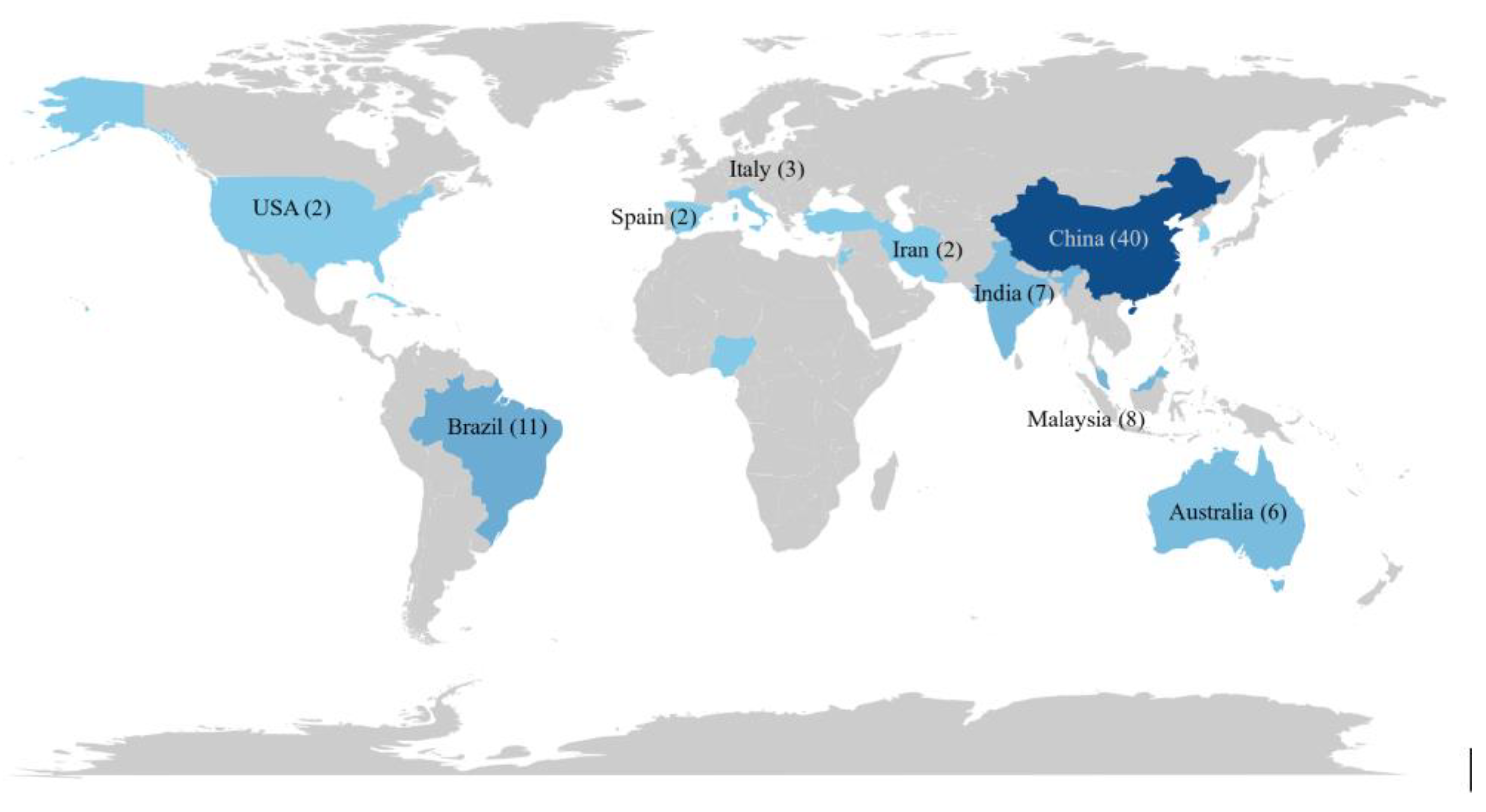

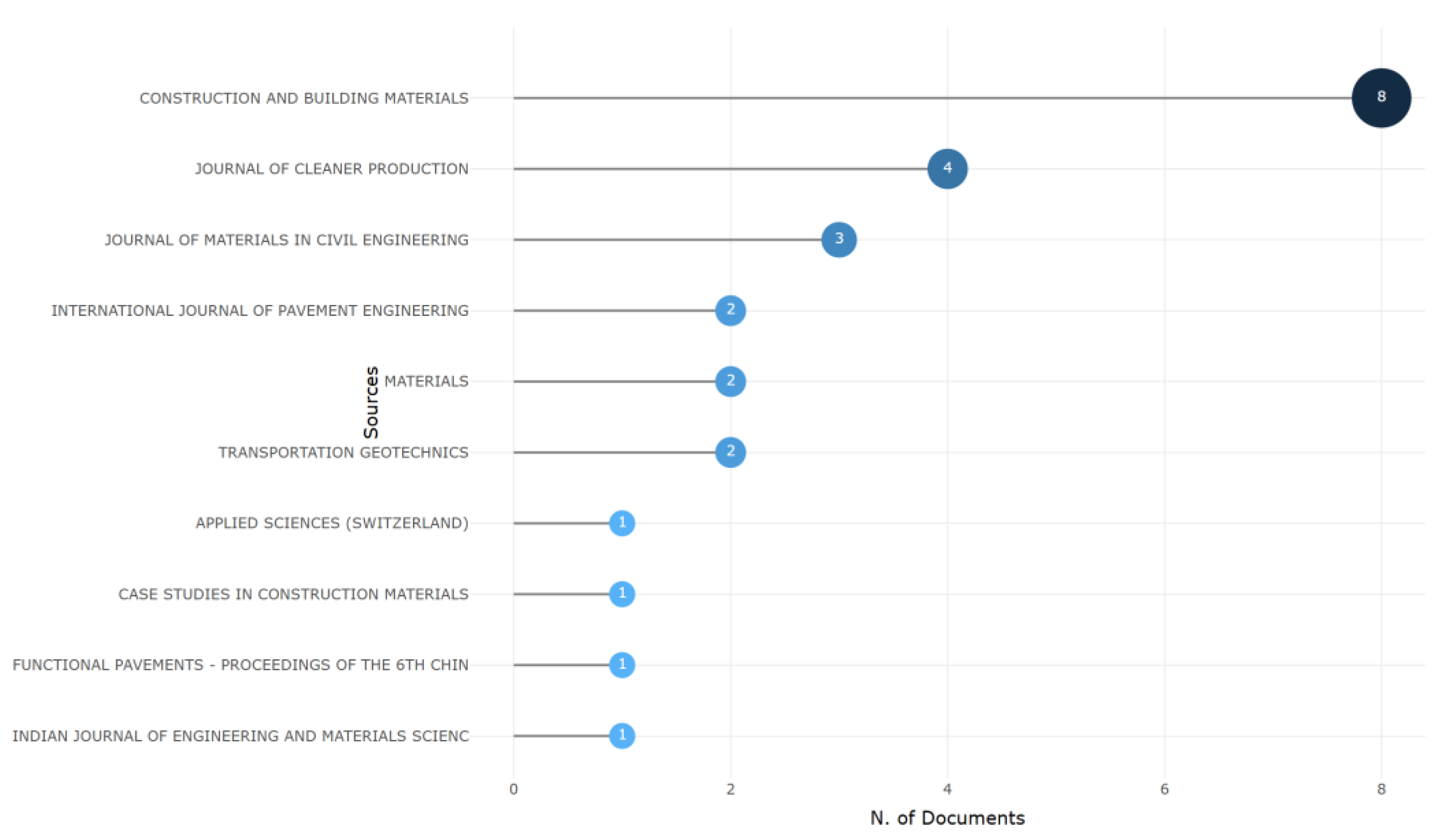

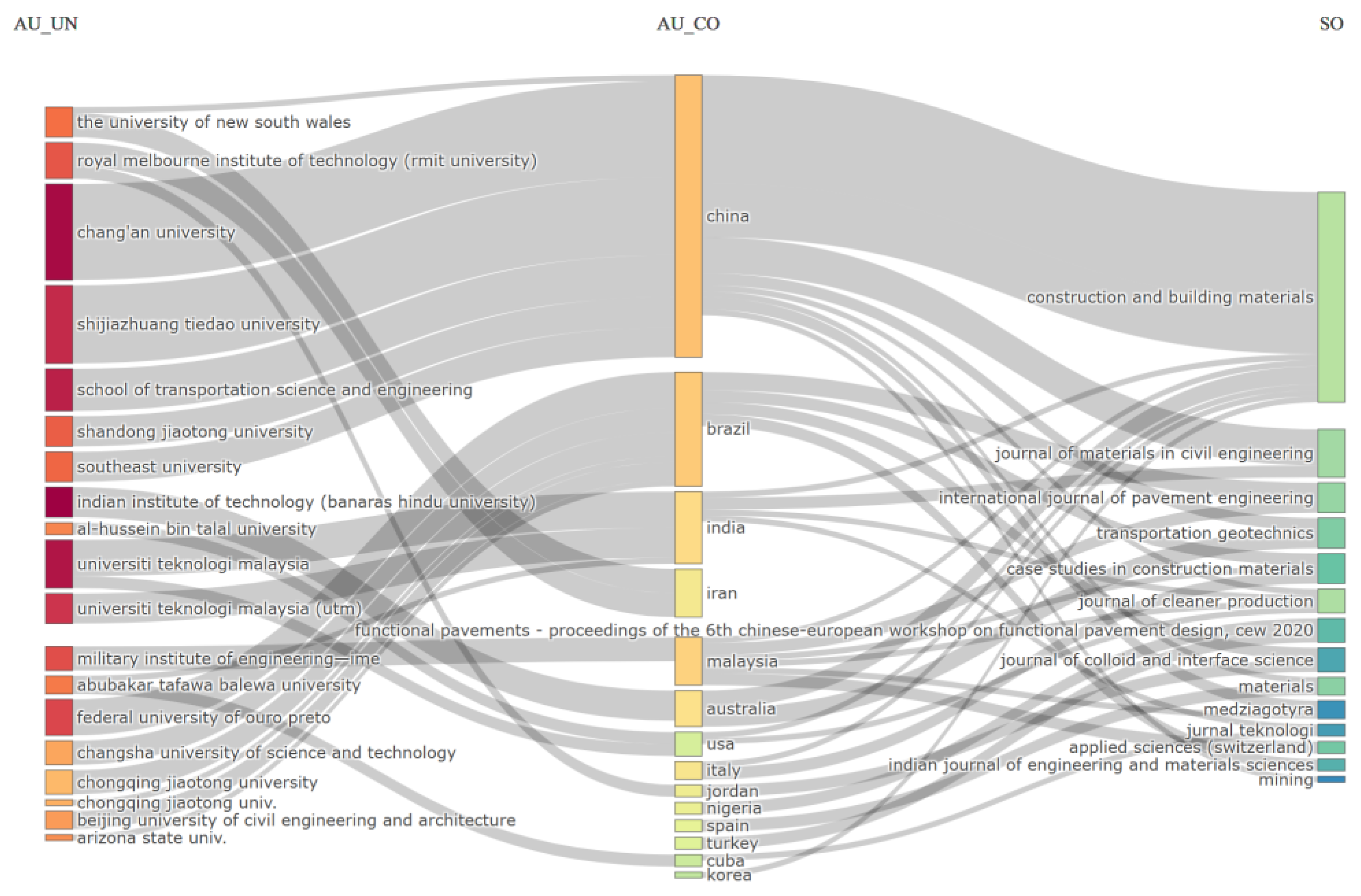

2. Methodology and Bibliometric Analysis

3. Utilization of Mining Waste in Flexible Pavement

3.1. Mining-Waste Types, Characteristics & Roles

3.2. Mining Waste Utilisation Methods & Performance Benefits

4. Impact of Mining Waste on Asphalt Performance

4.1. Rutting Resistance

4.2. Fatigue Resistance

4.3. Moisture Susceptibility

5. Environmental Impacts of Mining-Waste Use in Flexible Pavements

5.1. Leaching & Toxicity Potential

5.2. Greenhouse-Gas Emissions

6. Economic Impacts of Mining-Waste Use in Flexible Pavements

7. Conclusions and Future Recommendation

- Future work must move beyond short-term mechanical properties by conducting long-term field monitoring of trial pavement sections under real traffic and environmental conditions. This should be complemented by laboratory research employing advanced aging simulations, such as multi-stage Pressure Aging Vessel (PAV) protocols and ultraviolet (UV) aging, to accurately predict the evolution of mixture properties and resistance to fatigue and low-temperature cracking over a full-service life.

- A holistic understanding of the environmental and economic implications is required. This necessitates comprehensive Life-Cycle Assessments (LCA) to quantify the cradle-to-grave environmental footprint, including energy consumption and emissions. Concurrently, thorough Life-Cycle Cost Analyses (LCCA) should be performed to model the full economic impact, covering material processing, transport, construction, and long-term maintenance costs, providing asset managers with robust data for decision-making.

- To confirm the long-term efficacy of bitumen in encapsulating heavy metals, research is needed to assess leaching behaviour under dynamic and realistic environmental conditions, such as varying pH levels and repeated freeze-thaw cycles. This will build confidence in the environmental safety of using mining wastes in pavement structures.

- To address the significant variability in mining wastes from different sources, a critical research need is the development of a standardized characterization and classification protocol. This would link the mineralogical, chemical, and physical properties of wastes to their expected performance in asphalt, creating a foundation for reliable specifications. Research should also focus on developing cost-effective beneficiation techniques to homogenize waste materials for consistent performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSR | Dynamic Shear Rheometer |

| MSCR | Multiple Stress Creep Recovery |

| RTFOT | Rolling Thin Film Oven Test |

| LAS | Linear Amplitude Sweep |

| HMA | Hot-Mix Asphalt |

| SMA | Stone Mastic Asphalt |

| PG | Performance Grade |

| CF | Carbon Fibre |

| ESAL | Equivalent Single Axle Load(s) |

| TCLP | Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure |

| TSR | Tensile Strength Ratio |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| EAF | Electric Arc Furnace (slag) |

| MSR | Marshall Stability Ratio |

References

- Kobayashi, H.; Garnier, J.; Mulholland, D.S.; Quantin, C.; Haurine, F.; Tonha, M.; Joko, C.; Olivetti, D.; Freydier, R.; Seyler, P.; et al. Exploring a New Approach for Assessing the Fate and Behavior of the Tailings Released by the Brumadinho Dam Collapse (Minas Gerais, Brazil). J Hazard Mater 2023, 448, 130828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerals Research Institute of Western Australia Alternative Use of Tailings and Wast3. Available online: https://www.mriwa.wa.gov.au/minerals-research-advancing-western-australia/focus-areas/alternative-use-of-tailings-and-waste/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Mineral Processing Wastes - Material Description - User Guidelines for Waste and Byproduct Materials in Pavement Construction - FHWA-RD-97-148. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/infrastructure/structures/97148/mwst1.cfm (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Chapter 4: Mining Waste. Available online: https://www.sgu.se/en/itp308/knowledge-platform/4-mining-waste/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Pickin, J.; Wardle, C.; O’farrell, K.; Stovell, L.; Nyunt, P.; Guazzo, S.; Lin, Y.; Caggiati-Shortell, G.; Chakma, P.; Edwards, C.; et al. National Waste Report 2022. Blue Environment Pty Ltd 2022, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Valenta, R.K.; Lèbre, É.; Antonio, C.; Franks, D.M.; Jokovic, V.; Micklethwaite, S.; Parbhakar-Fox, A.; Runge, K.; Savinova, E.; Segura-Salazar, J.; et al. Decarbonisation to Drive Dramatic Increase in Mining Waste–Options for Reduction. Resour Conserv Recycl 2023, 190, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asphalt Market Size, Share & Trend | Report -2033. Available online: https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/market-reports/asphalt-market-108615 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Asphalt Market Size, Growth & Analysis to 2032. Available online: https://straitsresearch.com/report/asphalt-market (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Asphalt Market Size, Share & Trend | Report -2033. Available online: https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/market-reports/asphalt-market-108615 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Global Asphalt Market Expected to Reach USD 397.2 Million by 2033 - IMARC Group. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/asphalt-market-statistics (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Asphalt Market to Reach USD 389.9 Million by 2032 |. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2024/10/01/2956238/0/en/Asphalt-Market-to-Reach-USD-389-9-Million-by-2032-Increasing-Infrastructure-Development-and-Growing-Demand-from-the-Construction-Industry-Propel-Market-Growth-SNS-Insider.html (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Bastidas-Martínez, J.G.; Reyes-Lizcano, F.A.; Rondón-Quintana, H.A. Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregates in Asphalt Mixtures for Pavements: A Review. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition) 2022, 9, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiger, M.; Mamatha, K.H.; Dinesh, S.V. Use of Recycled Aggregates in Bituminous Mixes. Mater Today Proc 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeshwini, S.; Mamatha, K.H.; Dinesh, S.V. Characterization of Long-Term Field Aging: Differential Impact on Rheological, Chemical, and Morphological Properties of Binders across the Lanes of Flexible Pavement. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J Informetr 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Qu, F.; Zhao, C.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Wu, V.; Li, W. Recycling of Copper Tailing as Filler Material in Asphalt Paving Mastic: A Sustainable Solution for Mining Waste Recovery. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024, 20, e03237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xie, K.; Meng, Y.; Fu, T.; Fang, G.; Luo, X.; Wang, Q. Feasibility and Environmental Assessment of Reusing Aluminum Tailing Slurry in Asphalt. Constr Build Mater 2024, 411, 134737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sha, A.; Wang, Z.; Song, R.; Cao, Y. Investigation of the Self-Healing, Road Performance and Cost–Benefit Effects of an Iron Tailing/Asphalt Mixture in Pavement. Constr Build Mater 2024, 422, 135788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Si, C.; Li, S.; Jia, Y.; Guo, B. Iron Tailings as Mineral Fillers and Their Effect on the Fatigue Performance of Asphalt Mastic. Materials 2024, 17, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, V.L.; Guimarães, A.C.R.; Coelho, L.M.; dos Santos, W.W.; da Silveira, P.H.P.M.; Monteiro, S.N. Recycling Iron Ore Waste through Low-Cost Paving Techniques. Sustainability 2024, Vol. 16, Page 5570 2024, 16, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.M.; Betancourt, S.; Rodríguez, E.; Ribeiros, L.F.M.; de Farias, M.M. Use of Mining Wastes in Asphalt Concretes Production. Revista Ingenieria de Construccion 2023, 38, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, W.M.; Marques, G.L.O.; Gomes, G.J.C. Geotechnical Performance of Isotropic and Foliated Quartzite Waste as Aggregate for Road Base and Asphalt Mixture. Transportation Geotechnics 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y. Utilization of Iron Ore Tailing as an Alternative Mineral Filler in Asphalt Mastic: High-Temperature Performance and Environmental Aspects. J Clean Prod 2022, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Si, C.; Li, S.; Jia, Y.; Guo, B. Iron Tailings as Mineral Fillers and Their Effect on the Fatigue Performance of Asphalt Mastic. Materials 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, T.; Dong, Z.; Tian, Z. Utilization of Iron Tailings as Aggregates in Paving Asphalt Mixture: A Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Solution for Mining Waste. J Clean Prod 2022, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, M.; Ling, M.; Sun, J.; Li, H.; Kang, X. Temperature Field Characterization of Iron Tailings Based on Microwave Maintenance Technology. Materials 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sha, A.; Wang, Z.; Song, R.; Cao, Y. Investigation of the Self-Healing, Road Performance and Cost–Benefit Effects of an Iron Tailing/Asphalt Mixture in Pavement. Constr Build Mater 2024, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Si, C.; Shi, X.; Cui, Y.; Bao, B.; Zhang, Q. Evaluation of the Rheological Properties of Asphalt Mastic Incorporating Iron Tailings Filler as an Alternative to Limestone Filler. J Clean Prod 2025, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, T.M.R.P.; Neto, O. de M.M.; Lucena, A.E. de F.L.; Lucena, L. de F.L.; Nascimento, M.S. Viability of Asphalt Mixtures with Iron Ore Tailings as a Partial Substitute for Fine Aggregate. Transp Res Rec 2024, 2678, 770–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Wan, S.; Yang, C.; Ma, X.; Dong, Z. Self-Stress and Deformation Sensing of Electrically Conductive Asphalt Concrete Incorporating Carbon Fiber and Iron Tailings. Struct Control Health Monit 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Gao, Y. Influence of Iron Tailing Filler on Rheological Behavior of Asphalt Mastic. Constr Build Mater 2022, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, K.; Jiao, C.; Zhu Wen; Wang, J. Performance of SMA Mixture Added Iron Tailings Coarse Aggregate; CRC Press, 2021; ISBN 9780367726102.

- Ullah, S.; Yang, C.; Cao, L.; Wang, P.; Chai, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, Z.; Lushinga, N.; Zhang, B. Material Design and Performance Improvement of Conductive Asphalt Concrete Incorporating Carbon Fiber and Iron Tailings. Constr Build Mater 2021, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qu, F.; Tiwari, R.; Yoo, D.Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Development of Self-Sensing Asphalt Cementitious Composites Using Conductive Carbon Fibre and Recycled Copper Tailing. Constr Build Mater 2025, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Performance Evaluation of Asphalt Concrete Mixes Having Copper Industry Waste as Filler. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V., 2020; Vol. 48, pp. 3656–3667.

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Analysis and Comparison of Asphalt Mixes Containing Waste Fillers Using a Novel Ranking Methodology. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Evaluation of Engineering, Economic and Environmental Suitability of Waste Filler Incorporated Asphalt Mixes and Pavements. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2021, 22, S624–S640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Qu, F.; Zhao, C.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Wu, V.; Li, W. Recycling of Copper Tailing as Filler Material in Asphalt Paving Mastic: A Sustainable Solution for Mining Waste Recovery. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Analysing the Influence of Industrial Waste Fillers on the Ageing Susceptibility of Asphalt Concrete. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2022, 23, 3906–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Effect of Filler on the Bitumen-Aggregate Adhesion in Asphalt Mix. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2020, 21, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhomaidat, F.; Al-Kheetan, M.J.; Alosifat, S.M. Recycling Phosphate Mine Waste Rocks in Asphalt Mixtures to Fully Replace Natural Aggregate: A Preliminary Study. Results in Engineering 2025, 25, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Lu, R.; Li, J.; Yao, Z.; Zheng, J. Investigation on Synergistic Flame Retardancy of Modified Asphalt Using Tungsten Mine Tailings and Aluminum Trihydrate. Constr Build Mater 2024, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xie, K.; Meng, Y.; Fu, T.; Fang, G.; Luo, X.; Wang, Q. Feasibility and Environmental Assessment of Reusing Aluminum Tailing Slurry in Asphalt. Constr Build Mater 2024, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M.; Zakerinejad, M. Production of Sustainable Hot Mix Asphalt from the Iron Ore Overburden Residues. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2023, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandra, P.; Quaranta, S.; Apolo Miranda Figueira, B.; Caputo, P.; Porto, M.; Oliviero Rossi, C. Mining Wastes to Improve Bitumen Performances: An Example of Circular Economy. J Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 614, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, G.; Fini, E.H.; Obando, C.J.; Yu, M.; Zou, W. Effect of Taconite on Healing and Thermal Characteristics of Asphalt Binder. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, J.; Wu, Z.; Hu, L.; Yang, L.; Cheng, K. The High Value Utilization Characteristics of Coal Gangue Powder with Emulsified Asphalt Mastic through Rheological and Viscoelastic Damage Theory. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.C.R.; Arêdes, M.L.A. de; Castro, C.D.; Coelho, L.M.; Monteiro, S.N. Evaluation of the Mechanical Behavior of Asphaltic Mixtures Utilizing Waste of the Processing of Iron Ore. Mining 2024, 4, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenza-Abril, A.J.; Saval, J.M.; García-Vera, V.E.; Solak, A.M.; Herráiz, T.R.; Ortega, J.M. Effects of Using Mine Tailings from La Unión (Spain) in Hot Bituminous Mixes Design. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesare, S.; Piergiorgio, T.; Claudio, L.; Francesco, M. Application of Mining Waste Powder as Filler in Hot Mix Asphalt. MATEC Web of Conferences 2019, 274, 04002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustozzi, F.; Mansour, K.; Patti, F.; Pannirselvam, M.; Fiori, F. Shear Rheology and Microstructure of Mining Material-Bitumen Composites as Filler Replacement in Asphalt Mastics. Constr Build Mater 2018, 171, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.K.; Kalla, P.; Nagar, R.; Agrawal, R.; Jethoo, A.S. Laboratory Investigations on Hot Mix Asphalt Containing Mining Waste as Aggregates. Constr Build Mater 2018, 168, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Application of Waste Materials as Fillers in Bituminous Mixes. Waste Management 2018, 78, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluwasola, E.; Hainin, M.R.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Aziz, A.; Naqiuddin, M.; Warid, M. Volumetric Properties and Leaching Effect of Asphalt Mixes with Electric Arc Furnace Steel Slag and Copper Mine Tailings; 2016;

- Gürer, C.; Selman, G.Ş. Investigation of Properties of Asphalt Concrete Containing Boron Waste as Mineral Filler. Medziagotyra 2016, 22, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwasola, E.A.; Hainin, M.R. Evaluation of Performance Characteristics of Stone Mastic Asphalt Incorporating Industrial Waste. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Akin Oluwasola, E.; RosliHainin, M.; Maniruzzaman Aziz, M.A.; Arafat Yero, S. EFFECT OF MOISTURE DAMAGE ON GAP-GRADED ASPHALT MIXTURE INCORPORATING ELECTRIC ARC FURNACE STEEL SLAG AND COPPER MINE TAILINGS; 2016;

- Oluwasola, E.A.; Hainin, M.R.; Aziz, M.M.A. Comparative Evaluation of Dense-Graded and Gap-Graded Asphalt Mix Incorporating Electric Arc Furnace Steel Slag and Copper Mine Tailings. J Clean Prod 2016, 122, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin Oluwasola, E.; Hainin, R.; Aziz, M.A. Evaluation of Rutting Potential and Skid Resistance of Hot Mix Asphalt Incorporating Electric Arc Furnace Steel Slag and Copper Mine Tailing; 2015; Vol. 22;

- Oluwasola, E.A.; Hainin, M.R.; Aziz, M.M.A. Evaluation of Asphalt Mixtures Incorporating Electric Arc Furnace Steel Slag and Copper Mine Tailings for Road Construction. Transportation Geotechnics 2015, 2, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwasola, E.A.; Hainin, M.R.; Aziz, Md.M.A.; Mahinder Singh, S.S.A. Effect of Aging on the Resilient Modulus of Stone Mastic Asphalt Incorporating Electric Arc Furnace Steel Slag and Copper Mine Tailings. In InCIEC 2014; Springer Singapore, 2015; pp. 1199–1208.

- Mashaan, NS., De Silva, TS. (2024). Review on Assessment and Performance Mechanism Evaluation of Non-Structural Concrete Incorporating Waste Materials. Applied Mechanics, 5(3), 579-599.

- Mashaan, N.; Yogi, B. Mining Waste Materials in Road Construction. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaan, N.; Dassanayake, K. (2025). Rutting and Aging Properties of Recycled Polymer-Modified Pavement Materials. Recycling, 10(2), Article number 60.

| Mining Waste Type | Predominant Chemical Components | Typical Physical Characteristics | Role(s) in flexible pavement | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal Gangue Powder (CGP) | High SiO₂ content | Fine powder, Density=2.27 g/cm³ | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | [47] |

| Phosphate Mine Waste Rocks (PMWR) | SiO₂ (18.09%), CaO (37.47.75%), Al₂O₃ (1.38%), P₂O5 (2.86%) | Crushed rock aggregate, Specific Gravity = 2.455 g/cm³, Water Absorption = 9.19% | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [41] |

| Iron Tailings Filler (ITF) | SiO₂ (66.70%), Fe₂O₃ (9.52.5%), CaO (4.56%), Al₂O₃ (8.06.1%) | Fine powder (0.075mm), density=2.36 g/cm³, Smooth, angular particles with well-defined edges | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | [28] |

| Copper Tailings (CT) | SiO₂ (49.24%), Al₂O₃ (21.19%), Fe₂O₃ (6.63%), CaO (6.75%), K₂O (9.02%) | Fine powder (0.075mm), Larger angularity, higher surface area, rough surface | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [34] |

| Iron Tailings (IT) | Magnetite (Fe₃O₄), quartz (SiO₂), actinolite, chlorite, apatite, hematite (Fe₂O₃), | Aggregate size (4.75-9.5mm, 4.75-13.2mm, 9.5-13.2mm), density=2.8 g/cm³, Angular, rough-textured particles, Magnetic properties noted | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [26] |

| Copper Tailings Powder (CTP) | SiO₂ (49.24%), Al₂O₃ (21.19%), Fe₂O₃ (6.63%), CaO (6.75%), K₂O (9.02%) | Fine powder (0.075mm), Density=2.87 g/cm³, Angular & rough surface | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | [38] |

| Iron Tailings (IT) | SiO₂ (~68%), CaO (~7%), Al₂O₃ (1~8%), Fe₂O₃ (~7%) | Fine powder (0.075mm), Angular shape, Density=3.02 g/cm³ | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | [24] |

| Tungsten Mine Tailings (TMT) | SiO₂ (53.21%), Al₂O₃ (19.74%), CaO (9.85%), Fe₂O₃ (3.41%) | Fine powder, strongly hydrophilic | Modifier in Asphalt binder | [42] |

| Iron Tailing Filler (ITF) | SiO₂ (~51 %) CaO (~9.5 %) | Fine powder, Irregular shape density=2.785 g/cm³ | Filler in Asphalt mixture | [27] |

| Isotropic Quartzite Waste (IQ) | Quartz: 83.2 %; Muscovite: 16.8 % | Crushed Aggregate. Density ≈ 2.65 g/cm³ | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [22] |

| Foliated Quartzite Waste (FQ) | Quartz: 73.2 %; Kyanite: 18.5 %; Muscovite: 3.6.8 % | Crushed Aggregate. Density ≈ 2.84 g/cm³ | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [22] |

| Aluminum Tailing Slurry (ATS) | Al₂O₃ (50.12%), SiO₂ (19.79%), Fe₂O₃ (25.05%), TiO₂ (2.43%) | Fine powder (0.075mm), density=3.07 g/cm³, irregular, coarse-textured particles with fine attached grains | Modifier in Asphalt Binder | [43] |

| Iron Ore Tailings (IoT) | SiO₂ (29.4%), Fe₂O₃ (38.1%), Al₂O₃ (22.8%), MgO (7.9%) | Fine particles | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [29] |

| Iron Ore Overburden (IOO) | SiO₂ (43.15%), Fe₂O₃ (24.78%), Al₂O₃ (15.79%), Cao (7.2%) | Crushed rock aggregate (various sizes) | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [44] |

| Iron Tailings | SiO₂ (63.47 %), Al₂O₃ (12.55 %), Fe₂O₃ (9.79 %), CaO (3.59 %) | Coarse and Fine, density = 2.8 g/cm³, Smooth texture | Aggregate in Asphalt mixture | [25] |

| Iron Ore Tailing (IOT) | SiO₂ (28.85%), CaO (15.23%), Al₂O₃ (13%), Fe₂O₃ (29.19%), | Fine powder (0.075mm), Density=3.09 g/cm³, Smooth & Angular shape, | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | [23] |

| Manganese Ore Tailings | Al₂O₃ (34.10%), SiO₂ (46.95%), MnO (14.95%), Fe₂O₃ (7.33%) | Fine powder, Density=2.95 g/cm³ | Modifier in Asphalt Binder | [45] |

| Mining Waste | Utilized | Dosage % | Binder and Mixture Type | Key Findings | Optimum Content | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper tailings (CT) | Filler | 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% | AH-70 bitumen AC-13 mixture | CT substitution increases high-temperature rutting resistance but degrades low-temperature cracking resistance and moisture susceptibility above 50%. | 50% | [34] |

| Phosphate mine waste rocks | Aggregate | 100% | Pen 60/70 | 100 % PMWR mix: 20 % Cantabro loss vs. 17 % for limestone; SEM showed weak binder–aggregate interface; FTIR revealed PO₄³⁻ bands causing increased brittleness. | ≤ 40 % | [41] |

| Iron tailings (IT) | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 20%, 50%, 80%, 100% | Bitumen 70# | Increasing IT content lowers high-temperature performance and fatigue response. Binder-filler interaction is purely physical and weakens with more IT. Addition of 1.5% silane coupling agent (SCA) substantially restores and even enhances rheological properties. | 80% ITF (with 20% LF) plus 1.5% SCA for best rheological improvement; 100% ITF for greatest economic benefit | [28] |

| Coal gangue powder (CGP) | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, 1.5 | Bitumen 70# Emulsified Asphalt Mastic (EAM) |

Higher filler content and (Rotating Thin Film Oven Test) RTFOT aging improve high-temperature stability and stress sensitivity but reduce fatigue resistance. EAM with CGP and Portland Cement outperforms Limestone Powder filled mastic at high temperature, whereas LP-mastic retains better fatigue resistance; CGP is a viable green filler. | 1.2–1.5 for CGP yields optimal high-temperature performance with minimal fatigue loss | [47] |

| Copper tailings powder (CTP) | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2 | AH-70 Bitumen | CT’s rough surface and higher specific surface area enhanced high-temperature rutting resistance; low-temperature cracking and moisture stability slightly declined but remained acceptable. | 1.2 for maximal rutting resistance with balanced overall performance | [38] |

| Iron tailings | Aggregate | 4.75–9.5 mm; 4.75–13.2 mm; 9.5–13.2 mm |

SBS Class I-C modified asphalt | Specimens with 4.75–13.2 mm tailings achieved the best heating (126 °C in 2 min) and superior road performance (dynamic stability, direct-tension strength, immersion and freeze–thaw resistance). | 4.75–13.2 mm | [26] |

| Tungsten mine tailings (TMT) | Composite flame-retardant modifier with aluminium trihydrate (ATH) | ATH/TMTs ratios of 5 %/2 %, 10 %/4 %, 15 %/6 %, 20 %/8 % | 70# SBS-free road asphalt | Increased in softening point and decreased in penetration & ductility. Limiting oxygen impact increased significantly, showing enhanced flame retardancy property. Maintains good low temperature cracking resistance. Thermal stability improved due to denser & more compact char layer blocking heat & mass transfer. | 5 % ATH + 6 % TMTs | [42] |

| Iron tailings | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 1.0 | Bitumen 70# | IT are primarily quartz and highly angular. Lower adhesion energy as compared to limestone but strong filler–asphalt interaction. LAS fatigue life meets performance requirement | 1.0 | [24] |

| Aluminum tailing slurry (ATS) | Modifier | 3%,6%,9%,12%, and 15% | Bitumen 70# | ATS increased the complex modulus (G*), rutting factor (G*/sinδ), and recovery rate (R) but decreased the the phase angle (δ) and nonrecoverable compliance (Jnr). Enhanced thermal stability, slightly reduced “bee” structures. Storage stability drops significantly above 9 %, no pollution risk and strong economic benefits | 9% | [43] |

| Iron ore waste | Aggregate | M2:20%. M3: 17% |

CAP 50/70 | For medium traffic level of N = 5 × 10⁶, M1 & M3 gave identical layer thickness (6.9 cm) and fatigue class 1; M2 had thicker layer (8.2 cm) and fatigue class 0 but still met cracked-area limits. | 17% (M3) | [48] |

| Quartzite waste | Aggregate | 100% | Pen 50/70 | Isotropic (IAM) & foliated (FAM) quartzite met ITS (>0.65 MPa) and Marshall stability; IAM showed higher stiffness, both fulfilled MeDiNa fatigue & rutting limits for medium traffic. | 100% | [22] |

| Iron tailing (IT) | Filler | 20%, 40%, 60%, 80% | Bitumen 70# | IT improved microwave heating and healing, 60% & 80% IT boosted healing capacity by 2.5× and 2.75× after five cycles; high-temperature stability and moisture resistance remained acceptable. | 40% | [27] |

| Nickel (A) /Cobalt (C) tailings | Filler | 100% | CA 50-70 | Mineral residue volumetric parameters remain within specification. Stability increased by 17% (A) and 9% (C). No significant changes in flow, stiffness, tensile strength, or Cantabro abrasion. Technically viable and offers environmental benefit by valorising waste. | 100% | [21] |

| Iron ore tailings (IoT) | Aggregate | 7.5%, 10%, 12.5% | Pen 50/70 | 12.5% IoT mix showed highest tensile strength, resilient modulus, fatigue life, and permanent-deformation resistance. Reduced production cost per km and surface temperature by 2.9 °C. | 12.5% | [29] |

| Iron ore overburden (IOO) | Aggregate | 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% | Pen 60/70 PG 70-16 |

Mechanical properties (Marshall stability, flow, volumetric parameters) remain within specifications even at 100 % IOO. Environmental (TCLP) tests show heavy metals below hazardous limits, indicating solidification by bitumen. Electrical volume resistivity reduced (improved conductivity) and microwave de-icing efficiency up to 15.74 times. Cost–benefit analysis reveals positive NPV (e.g. US $926 M nationwide, US $0.96 M pilot project) | 100% | [44] |

| Iron tailings (IT) | Aggregate | 100% | Pen 70 AC-20 HMA |

All tailings mixes exceed minimum rutting stability requirements, but coarse tailing replacements degrade low-temperature cracking and moisture resistance, especially tailing sand mix. Performance enhancements using limestone fine aggregate, composite modified asphalt, hydrated lime or silane coupling agent restore and exceed specification for rutting, cracking, and TSR. | 100% combined with composite (SBS and Crumb rubber) modified binder and either 1.7 % hydrated lime or 0.4 % silane coupling agent | [25] |

| Iron tailings (IT) | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2 | Pen 60/70 | IT enhances viscosity, rutting factor, and elastic recovery. Smaller particle size and larger specific surface area improve adsorption and stiffening effect. Leaching tests confirm environmental safety. Cost-benefit analysis shows economic viability. | 1.0 | [23] |

| Iron tailing | Aggregate | Carbon fibre (CF) to tailing = 1:3 | Pen 70 AC-13 HMA |

Adequate mechanical strength & low resistivity. Negative fractional changes in electrical resistance (FCR) under low stress (compaction), reversible/irreversible FCR under medium/high stress enable microcrack detection. The mixture functions as an intrinsic damage sensor until macrocracking occurs. | CF: TA 1:3 | [30] |

| Manganese ore tailings | Filler | 1%, 3%, 5%, 10% | Pen 50/70 | Improved resistance to stress, rutting, and fatigue. Anti-aging effect observed at 10% w/w. Favourable physio-chemical interactions between bitumen and filler. | 10% | [45] |

| Iron tailing (IT) | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2 | Pen 60/80 | Improved viscosity, complex modulus, creep stiffness but decrease phase angle, viscosity-temperature susceptibility and m-value. Enhances anti-rutting but excess IT greater than 1.0 reduce workability and low-temp cracking. | 1.0 | [31] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Filler | 4 %, 5.5 %, 7 %, 8.5 % | VG-30 | Alternate fillers match or exceed stone dust in strength, rutting and ravelling, governed by particle fineness, air-voids and film thickness. Moisture resistance depends on filler mineralogy and film thickness, calcium-based fillers (kota stone, red mud) outperform silica-based (CT, glass powder). Ageing sensitivity: tensile strength ratio, Cantabro loss, Marshall quotient and Marshall stability depend on both filler type and content, while indirect tensile strength ageing is driven solely by dosage. | CT 5.5 % | [39] |

| Iron tailings (IT) | Aggregate | 100% | SBS Type I-D modified asphalt SMA |

Iron tailings meet all current specification requirements. High temperature stability slightly (~20 %) lower than basalt but meet the minimum requirement. Immersion and freeze-thaw TSR both greatly exceed specification limits. | 100% | [32] |

| Iron tailings | Aggregate | Tailing aggregate (TA): Natural Aggregate = 1:3 (25 % TA) Carbon Fibre = 0.1–1.4 % by mix weight |

Bitumen 70# Dense-graded AC-13 |

Combined CF + TA (25 % TA, 0.2–0.4 % CF) yields optimum conductive mixes with enhanced electrical conductivity and improved mechanical performance; 0.4TNA mix shows reliable, reversible resistance change under both tensile and compressive loading for self-sensing functionality. | 0.4% CF + 25% TA | [33] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Filler | 100% | PG 76-XX | Waste fillers produced mixes with similar or better strength, rutting and moisture resistance than stone dust; limestone slurry dust (LD) was best, rice straw ash (RSA) worst; except GP, all mixes met TSR ≥ 80 %; LD showed highest rut and crack resistance. | 100% | [37] |

| Taconite | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 0%, 10%, 20%, 30% | PG 64-22 | Healing index and thermal conductivity both increase with taconite content; best healing at 900 s, 5% strain, 50% damage; thermal conductivity rises from 0.1582 to 0.1870 W/(m·K) across dosages. | 30% | [46] |

| Copper tailings (CT) | Filler | 100% | Pen 60/70 | CT-filled mixes achieved satisfactory Marshall stability and volumetrics at lower asphalt demand; superior rutting & cracking resistance; slightly lower moisture- and ravelling-resistance due to high silica content. | 100 % | [35] |

| Copper tailings (CT) | Filler | 4%, 5.5%, 7%, 8.5% | VG-30 | Filler type and dosage significantly affect both active (mixability) and passive (moisture) adhesion. Ca-based fillers (natural stone dust and Kota stone dust)) markedly improved both adhesions; Si-based glass powder showed the poorest adhesion. | 4% | [40] |

| Copper tailings (CT) | Filler | 100% | VG-30 | All mixes met Marshall and volumetric criteria. Finer fillers (red mud, CT, carbide lime, glass powder) enhanced cracking and rutting resistance. Ca-based (carbide lime, stone dust) mixes excelled in adhesion and moisture resistance; glass powder mixes underperformed. Red mud ranked best overall, rice straw worst. | 100% | [36] |

| Well Cuttings (WC) | Aggregate | 100% | 35/50 bitumen AC-16 Surf mix (AC-WC) | Similar performance to control mix (porphyry); compliant with PG-3. Higher ITS and fatigue resistance at 5% bitumen. Good resistance to permanent deformation and acceptable water sensitivity above 4.5% binder. | 100% | [49] |

| Mine Tailings (MT) | Aggregate | 100% | 35/50 bitumen AC-16 Surf mix (AC-MT) | Required higher binder content due to higher porosity; showed good Marshall stability and fatigue resistance but failed water sensitivity (ITSR < 85%) at all binder levels. | Not viable (failed ITSR) | [49] |

| Tungsten residue | Filler | 100% | Pen 50/70, HMA | MWP meets EN 13043 gradation, similar viscoelastic behaviour to limestone filler, lower voids of dry compacted filler (28.1%) indicate lower bitumen absorption, improved resistance to permanent deformation in MSCR test, higher Marshall stability and ITS compared to control. | 100% | [50] |

| Magnetite powder | Filler in Asphalt Mastic | 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 | C170 & C320 | Magnetite-based mastics exhibited reduced temperature and loading-time susceptibility, higher stiffness and elastic response at elevated temperatures compared to limestone-filled mastics; no major particle clustering; ferromagnetic properties enable induction or microwave crack-healing application. | ≥ 1.0 | [51] |

| Kota stone mining waste (LSW) | Aggregate | 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% | VG-30, Bituminous concrete (BC), Dense Bituminous Concrete macadam (DBM) | Up to 50% replacement in BC and 25% in DBM met all Marshall design criteria, moisture susceptibility, rutting resistance and resilient modulus requirements; higher replacement levels caused decreased stability, increased flow and permanent deformation and lower ITS/TSR. | 50% for BC; 25% for DBM | [52] |

| Copper slag (CT) | Filler | 100% | VG-30, DBM | All seven-filler met Indian paving specifications. Finer particles (red mud and limestone dust) increased stiffness and cracking resistance. Porous fillers like copper tailing, rice straw and red mud raised air voids, driving higher bitumen demand. Calcium-rich fillers (CT, limestone dust) gave superior moisture resistance and adhesion while silica-rich wastes (glass powder, rice straw ash, brick dust) showed poorer moisture performance. | 100% | [53] |

| copper mine tailings | Aggregate | Mix 1: 0% Mix 2: 20 % CT Mix 3: 80 % EAF slag + 20 % CT Mix 4: 40 % EAF slag + 20 % CT |

Pen 80-100, ACW 14 | Mix 3 showed higher VMA, adequate VTM/VFA and Marshall stability as compared to control. All met JKR volumetric specs and TCLP leachate concentrations of Cu, Cr, Pb, Cd, Ni well below regulatory limits. | Mix 3 | [54] |

| Boron Waste | Filler | 4 %, 5 %, 6 %, 7 %, 8 % | Pen 50/70, HMA | Stability decreases when filler > 6 % due to thinner asphalt film, control (6 % limestone) had highest stability. Highest density obtained at 5 % filler, matching control’s impermeability. 7 % boron filler showed lowest Marshall stability loss after 48 h immersion (9.7 %). Stiffness modulus at 10 °C & 20 °C for 6 % boron filler almost identical to control. | 5.7% | [55] |

| Copper mine tailings (CT) | Aggregates | Mix 1: 0% Mix 2: 80% Granite, 20% CT Mix 3: 80% EAF Steel Slag, 20% CT Mix 4: 40% EAF Steel Slag, 40% Granite, 20% CT |

PG 76-22 and 5 % EVA-modified Pen 80/100, SMA14 | All mixes with EAF slag + CT outperformed the control. Mix 3 showed the highest stiffness (resilient modulus), the lowest permanent deformation (axial strain & CSS), and the shallowest rut. Moisture susceptibility (TSR) remained within allowable limits. EVA-modified binder further increased stiffness and rutting susceptibility compared to PG 76-22. | Mix 3 | [56] |

| Copper mine tailings (CT) | Aggregates | Mix 1: 0 %, Mix 2: 20 % CT Mix 3: 20 % EAF Mix 4: 40 % combined CT + EAF |

PG 76-22 and 5 % EVA-modified Pen 80/100, SMA14 | Waste-incorporated mixes require slightly higher OBC and show increased Marshall stability and bulk specific gravity compared to control. Moisture conditioning (24 h/48 h) reduces retained strength index (RSI) but all mixes stay ≥ 75 %. Wet samples exhibit higher abrasion loss; EVA modification lowers abrasion loss vs. PG 76. Tensile strength ratio (TSR) ≥ 80 % for all except Mix 3 with PG 76 at 48 h. | Mix 4 | [57] |

| Copper mine tailings (CT) | Aggregates | Mix 1: 0 % Mix 2: 0 % EAF / 20 % CT Mix 3: 80 % EAF / 20 % CT Mix 4: 40 % EAF / 20 % CT / 40 % granite |

PG 76-22 and 5 % EVA-modified Pen 80/100, SMA14, ACW14 | Mix 3 showed up to 77.7 % reduction in rut depth and 42.9 % reduction in creep strain slope compared to control. All mixes with EAF/CT had TSR ≥ 80 % except mix 3 (SMA14 -PG76). TCLP leachates for heavy metals well below EPA limits | Mix 3 | [58] |

| Copper mine tailings (CT) | Aggregates | Mix 1: 0% Mix 2: 20 % CT Mix 3: 80 % EAF slag + 20 % CT Mix 4: 40 % EAF slag + 20 % CT |

PG 76-22 and Pen 80/100, ACW14 | Mix 3 showed the lowest final rut depth and rutting rate; after 4000 APA cycles it had already reached 70–80 % of its total rut depth, indicating rapid initial densification. Mix 3 achieved the highest British Pendulum Number (↑29.3 % for PG76-22; ↑20.5 % for 80/100) and mean texture depth, owing to the sharp edges, angular and rough texture of slag and tailings. | Mix 3 | [59] |

| Copper mine tailings (CT) | Aggregates | Mix 1: 0% Mix 2: 20 % CT Mix 3: 80 % EAF slag + 20 % CT Mix 4: 40 % EAF slag + 20 % CT |

PG 76-22 and Pen 80/100, ACW14 | Substituting granite with CT & EAF slag markedly improved Marshall stability, stiffness (MQ), and resilient modulus. Moisture susceptibility remained acceptable (TSR > 80%). Mix 3 gave the best overall performance.Aging increased stiffness and dynamic creep modulus. | Mix 3 | [60] |

| Copper mine tailings (CT) | Aggregates | Mix 1: 0% Mix 2: 15 % CT Mix 3: 83 % EAF slag + 15 % CT Mix 4: 41 % EAF slag + 15 % CT |

PG 76, SMA14 | EAF slag and CT mixes significantly reduced binder drain-down compared to control. Resilient modulus at 25 °C and 40 °C was higher in all waste-containing mixes under unaged, short term and long-term aging. Mix 3 showed the largest gains, especially after long-term aging, | Mix 3 | [61] |

| Minig Waste | Utilisation | Rutting Test Method(s) | Key Rutting Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal gangue powder (CGP) | Asphalt mastic | MSCR (0.1/3.2 kPa at 64 °C & 70 °C) | CGP mastic exhibited lower non-recoverable creep compliance Jnr as compared to limestone powder, corresponding to a PG70E (After RTFO) classification and enhanced high-temperature stability. | [47] |

| Iron tailing (IT) | Asphalt mastic | MSCR (0.1, 3.2, 6.4, & 12.8 kPa at 64 °C) | Replacing limestone with IT with SCA modification significantly decreased Jnr and increased elastic recovery (%R), indicating improved rutting resistance in IT-modified mastics. | [28] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Asphalt mixture | Wheel-tracking test (300 × 300 × 50 mm slabs, 0.7 MPa loading @ 60 °C, 42 cycles/min) | CT/carbon fibre composites achieved higher dynamic stability depth than control; substituting up to 50 % CT optimizes high-temp rutting performance. | [34] |

| Iron tailings | Asphalt mixture | Wheel-tracking test (300 × 300 × 50 mm slabs, 0.7 MPa loading @ 60 °C, 42 cycles/min) | Iron tailings-based mixtures showed a 16.55 % higher dynamic stability than basalt mixtures under identical test conditions, reflecting superior resistance to high-temperature rutting. | [26] |

| Copper tailing powder (CTP) | Asphalt mastic | DSR temperature sweep; rutting factor (G*/sin δ) | Replacing limestone with copper tailings boosted |G*| by 35–65 % at all filler-to-asphalt ratios and correspondingly raised |G*|/sin δ, demonstrating enhanced ruuting resistance. | [38] |

| Tungsten mine tailings (TMTs) + ATH | Asphalt Binder | DSR temperature sweep; rutting factor (G*/sin δ) | The composite asphalt with 20 % ATH + 6 % TMTs achieved G*/sin δ >15 kPa at 52 °C, demonstrating substantially improved rutting resistance versus unmodified binder. | [42] |

| Quartzite waste | Asphalt mixture | MeDiNa simulations | Predicted permanent deformation (rut) depths remained below 6 mm over five million passes for quartzite mixtures, indicating satisfactory rutting performance for pavement applications. | [22] |

| Aluminium tailing slurry (ATS) | Asphalt mastic | DSR temperature sweep; rutting factor (G*/sin δ); MSCR at 54 °C (0.1/3.2 kPa) | Rutting factor (G*/sin δ) increase with higher ATS dosages, indicating better rutting resistance. At 9 % ATS dosage, nonrecoverable creep compliance Jnr dropped by 26 % and recovery R increased by 43 % at 0.1 kPa, confirming enhanced high-temperature rutting resistance. | [43] |

| Waste Material | Utilization | Fatigue Test Method(s) | Key Fatigue Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron tailings (IT) | Asphalt mastics | DSR-LAS at 20 °C; strains 2.5 %, 5 %, 7.5 % | Finest, angular IT mastic reached Nf@5 % ≈ 1.09×10⁷ vs. limestone’s 1.34×10⁷. Gray correlation (r≈0.58) linked fatigue life to adhesion energy and binder–filler interaction, highlighting particle morphology’s role. | [24] |

| Iron tailings (IT) | Asphalt mastics | DSR-LAS; at 20 °C; strains 2.5 %, 5 %, | Unmodified IT mastics drops fatigue life Nf by 7.1 % at 2.5 % strain and 15.5 % at 5 % strain versus limestone controls, while SCA nearly restored and for 80 % IT exceeded the fatigue life by improving binder–filler adhesion. | [28] |

| Coal gangue powder (CGP) | Asphalt mastics | DSR-(LAS) (2.5 % & 5 % strain); pre- and post-RTFOT aging | Unaged CGP mastic fatigue life Nf at P/B = 0.9, 1.2 and 1.5, dropped by 50.8 %, 21.1 % and 8.2 %, respectively, versus P/B = 0.6 baseline. Post-RTFOT 0.6 and 1.5 fatigue life fell by 47.7 % and 40.4 %, respectively. | [47] |

| Manganese ore tailings | Asphalt Binder | DSR time-sweep | Fatigue parameter G*·sin δ increases with manganese content, indicating reduce fatigue resistance. | [45] |

| Iron tailings (IT) | Asphalt mixture | Indirect tensile fatigue test | Mixes with 7.5 % and 10 % iron tailings outperformed the control at low stress levels, while the 12.5 % tailings blend achieved the highest cycles-to-failure across all stresses demonstrating the best overall fatigue resistance. | [29] |

| Iron ore waste | Asphalt mixture | Controlled stress fatigue life tests MeDiNa simulations |

The mixture containing 20 % iron-ore waste (M2) exhibited a slightly reduced fatigue performance compared to the reference mix. In contrast, the mix with 17 % waste matched or slightly exceeded the control’s fatigue resistance, indicating that moderate incorporation of mining waste does not reduce and may even enhance fatigue life. | [48] |

| Isotropic quartzite waste (IAM) Foliated quartzite waste (FAM) |

Asphalt mixture | Indirect tensile fatigue test MeDiNa simulations |

FAM exhibits a higher number of cycles to failure at a given resilient strain (regression R² > 0.8), indicating slightly better lab fatigue resistance than IAM. Both IAM and FAM meet the MeDiNa–predicted limits (≤ 30 % cracked area & ≤ 20 mm rut depth) up to 5 × 10⁶ ESAL | [22] |

| Waste Material | Utilization | Moisture Test Method(s) | Key Moisture susceptibly Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper Tailing | Asphalt mastic | Pull-Off Adhesion Test | Copper tailings can be reused as asphalt mastic filler with acceptable moisture durability especially at moderate filler content (F/A ≈ 0.6), while higher tailings contents accelerate moisture damage. | [38] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Asphalt mixture | Immersion MSR Freeze–thaw splitting TSR |

Both MSR and the TSR decrease as CT content increases. Mixtures with up to 50 % CT still meet the specification criteria, whereas 75 % and 100 % CT fail to comply. | [34] |

| Iron tailings | Asphalt mixture | Immersion MSR Freeze–thaw splitting TSR |

All iron-tailings mixtures easily exceed the 80 % specification threshold for both MSR and TSR, despite slight reductions compared to the basalt control. | [26] |

| Isotropic quartzite waste (IAM) Foliated quartzite waste (FAM) |

Asphalt mixture | Freeze–thaw splitting TSR | Asphalt mixtures with IAM and FAM retain over 85 % of their tensile strength after freeze–thaw, comfortably meeting specification requirements. | [22] |

| Iron tailings | Asphalt mixture | Freeze–thaw splitting TSR | Iron-tailings coarse aggregate from TB can be used without special anti-stripping measures (TSR > 75 %), but TA tailings and tailings sand (TS) cause TSR values below specification (especially TS < 70 %), indicating significantly increased moisture susceptibility. | [25] |

| Iron tailings | Asphalt mixture | Freeze–thaw splitting TSR | Mixtures with 25% iron tailing and 0.2–0.6 % carbon fibre (CF) maintained TSR > 75 % after conditioning, confirming moisture stability. | [33] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Asphalt mixture | Freeze–thaw splitting TSR | Cooper tailing mixture shows TSR value of 84.24 %, exceeding the 80 % minimum requirement specified for adequate moisture resistance. | [37] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Asphalt mixture | Freeze–thaw splitting TSR | Copper tailing (TSR = 84.24%) exceeds the 80 % specification requirements, demonstrating that using copper tailing as filler maintains adequate moisture resistance, with only a modest reduction compared to the conventional stone-dust control. | [35] |

| Copper tailing (CT) | Asphalt mixture | Freeze–thaw splitting TSR | Copper-tailings mixes achieved a TSR of 84.24 %, exceeding the 80 % minimum requirement and demonstrating that CT can be used as an effective asphalt filler without compromising moisture resistance. | [36] |

| Mining Waste Type (in asphalt) | Cr (mg/L) | Cd (mg/L) | Pb (mg/L) | Cu (mg/L) | Zn (mg/L) | Ba (mg/L) | Ni (mg/L) | Co (mg/L) | Key Finding | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper Tailings (CT) | 0.002 | NR | ND | 0.001 | 0.002 | NR | ND | ND | Under Limits | [34] |

| Iron Ore Overburden (IOO) | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.78 | 0.54 | ND | NR | NR | Under Limits | [44] |

| Aluminum Tailing Slurry (ATS) | 0.261* | NR | 0.638* | 0.297* | 1.01* | 0.184* | 0.175* | NR | Under Limits | [43] |

| EAF Steel Slag & Copper Mine Tailings | <0.019 | <0.402 | <2.961 | <0.083 | NR | NR | <0.001 (or ND) | NR | Under Limits | [54] |

| Iron Ore Tailing (IOT) | 0.00228* | 0.00027* | 0.00020* | 0.02677* | 0.10579* | 0.06161* | NR | NR | Under Limits | [23] |

| Copper Tailings Powder (CTP) | 0.002 | NR | 0 | 0.001 | 0.002 | NR | 0 | 0 | Under Limits | [38] |

| Waste Type | Economic Aspect(s) Investigated | Methodology | Key Finding | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron tailings filler (ITF) | Material cost savings, overall economic benefits when replacing limestone filler (LF). | Comparative cost analysis for 1km (2-lane) pavement (material prices, transport, modifier cost). | ITF substitution offers substantial economic advantages, with costs decreasing with increased ITF content, even with an SCA modifier. | [28] |

| Copper tailings (CT) (with Carbon Fibre) | Material cost savings, CT disposal cost savings. | Cost-benefit analysis for 1km unit road (AC-13, 50% LF replacement by CT). | Recycling CT as 50% LF replacement saves 725.84 USD/unit road in material costs and 41.04-134.79 USD/unit road in CT disposal costs. | [34] |

| Copper tailings powder (CTP) | Cost-benefit analysis, Net Present Value (NPV), Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR). | CBA for 1km (2-lane) HMA pavement over 10 years with a 15% discount rate, calculating NPV and BCR. | CTP application in asphalt mastic provides lucrative economic profits with BCR > 7.4 and positive NPV. | [38] |

| Iron tailings (ITs) as mineral fillers | Price comparison (ITs vs. Limestone), overall economic effectiveness, land & cost savings in maintenance. | Comparative cost figures for materials; estimation of savings for pavement maintenance application of ITs. | ITs are approx. 1/4 the price of limestone; their use in pavement maintenance can save 104 yuan/m² and extend service life. | [24] |

| Iron Tailing Filler (ITF) | Cost-benefit assessment (NPV, BCR). | CBA for 1km (4-lane) over a 10-year. | Incorporating ITF at rates of 60% & 80% in asphalt mixtures provides considerable economic efficiency, with positive NPV and BCR > 1. | [27] |

| Aluminum Tailing Slurry (ATS) powder | Cost-benefit analysis (NPV, BCR). | CBA for 1km (2-lane) HMA pavement over 10 years with a 15% discount rate. | Using ATS as an asphalt modifier is profitable (BCR 1.19) and offers considerable economic benefits, mainly from the low ATS cost. | [43] |

| Iron ore overburden (IOO) as aggregates & filler | Cost savings, NPV, CBA for local and large-scale applications. | CBA for 1km (2-lane) HMA pavement over a 10 year, considering material, transport, and IOO storage costs. | IOO HMA shows significant economic benefits (10-year NPV saving of >$900 million USD for 1000km new roads, approximately 960,000 USD saved for a 9.5km on-site project). | [44] |

| Iron tailings as aggregates | Material cost savings, general economic. | Price comparison of iron tailings vs. limestone and basalt. | Recycling iron tailings offers huge economic benefits as their price is approx. 1/4 of limestone and 1/6 of basalt. | [25] |

| Iron ore tailing (IOT) as mineral filler | Material cost savings, Cost-benefit analysis (NPV, BCR). | CBA for 1km (2-lane) asphalt pavement over 10 years with a 15% discount rate. | IOT as filler offers considerable economic benefits (BCR > 5, positive NPV) from reduced LF purchase and IOT disposal/transport costs. | [23] |

| Copper tailing (CT) as a filler | Material cost savings | Comparative material cost analysis for 1km (2-lane) pavement surface course. | Mixes with CT was more economic than conventional stone dust, offering up to 5% cost savings. | [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).