Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Empirical Review

2.2.1. Studies Related to Financial Innovation and Competition

2.2.2. Studies Related to Competition and Bank Performance /Stability

2.2.3. Studies Related to Financial Innovation and Bank Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Fintech Financial Stress Indicator Development

3.2. Pretest Requirements

- Cross Sectional Dependence Test

- Panel Unit Root Test

3.3. PVAR Model

4. Results

4.1. Data

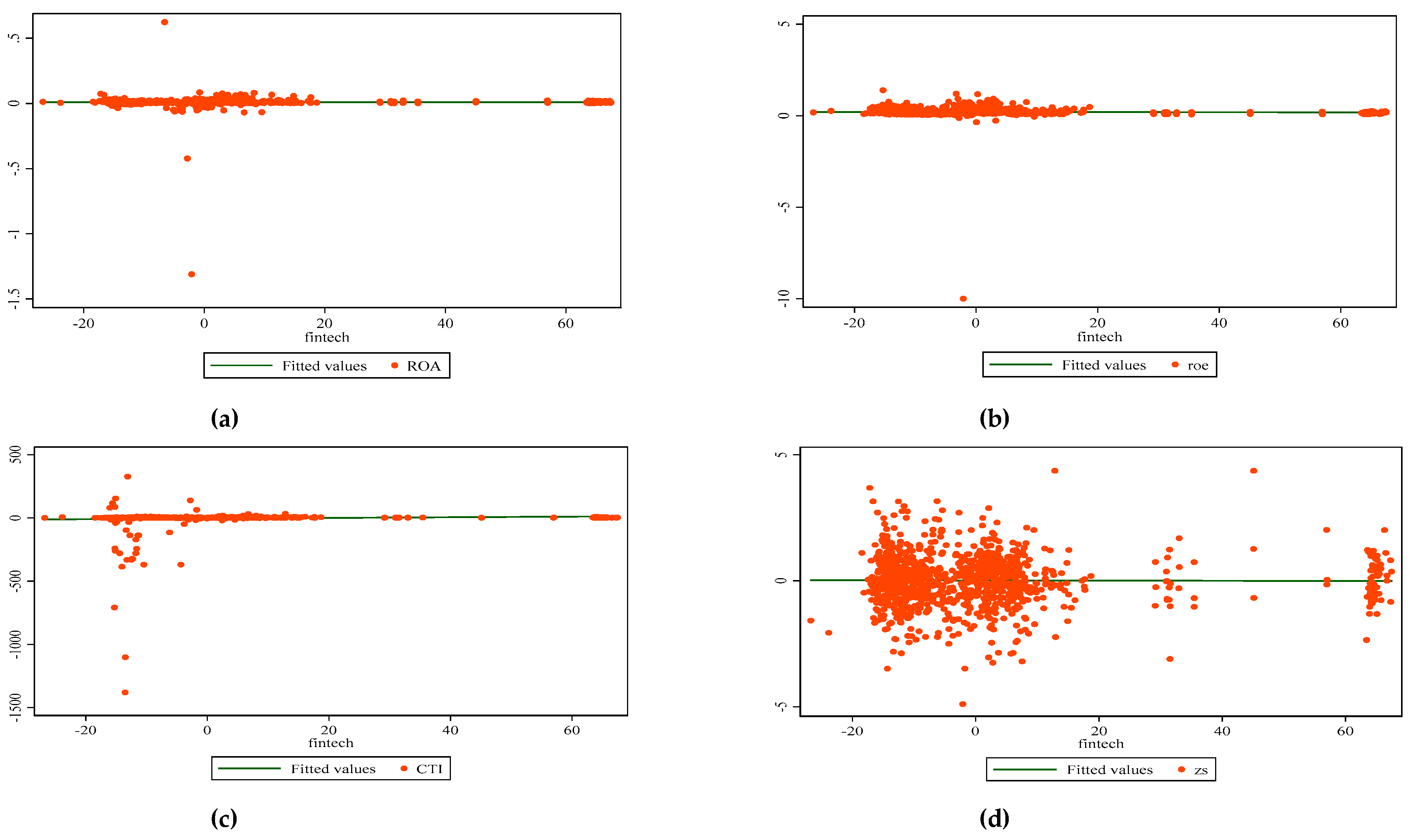

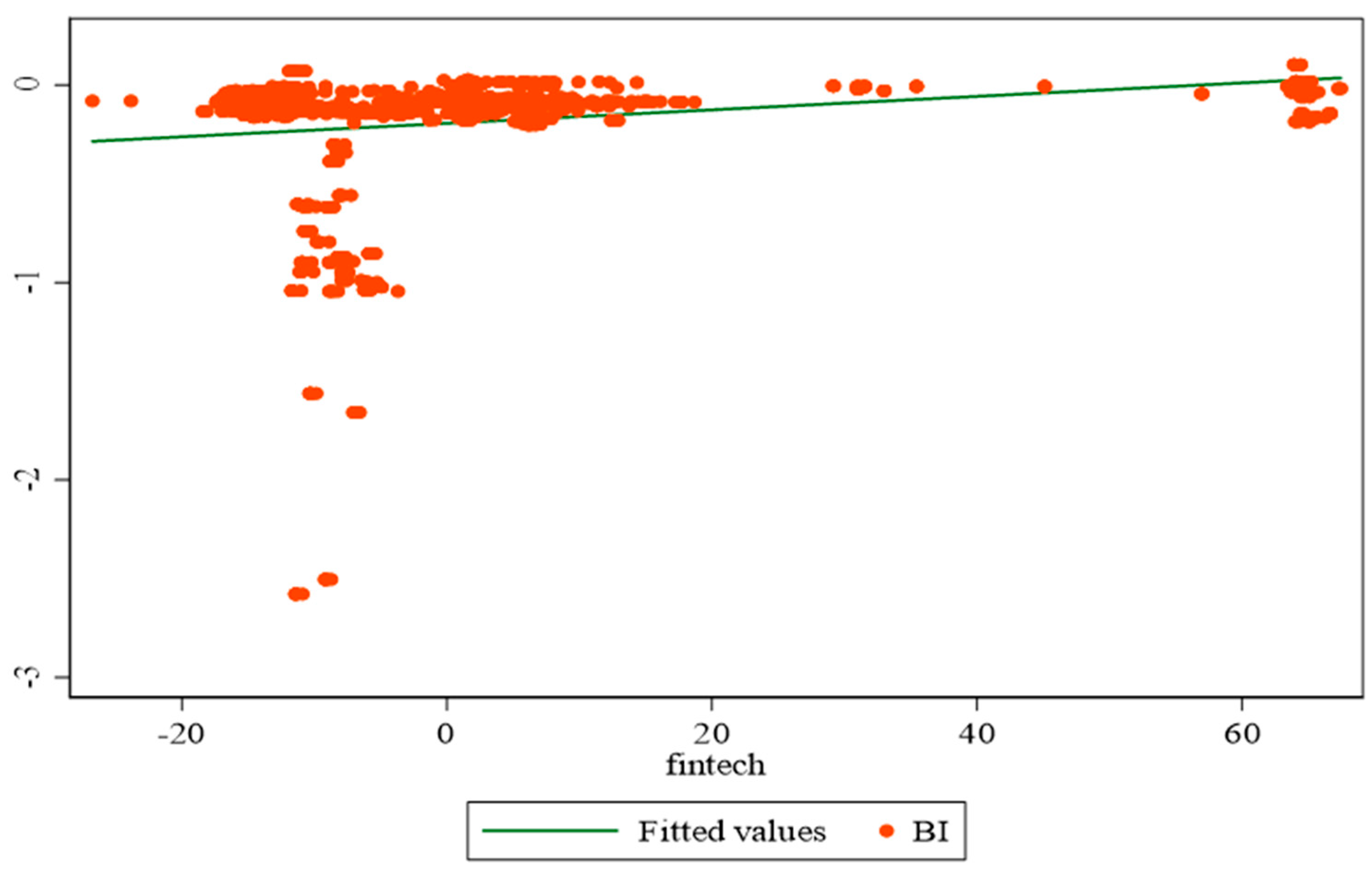

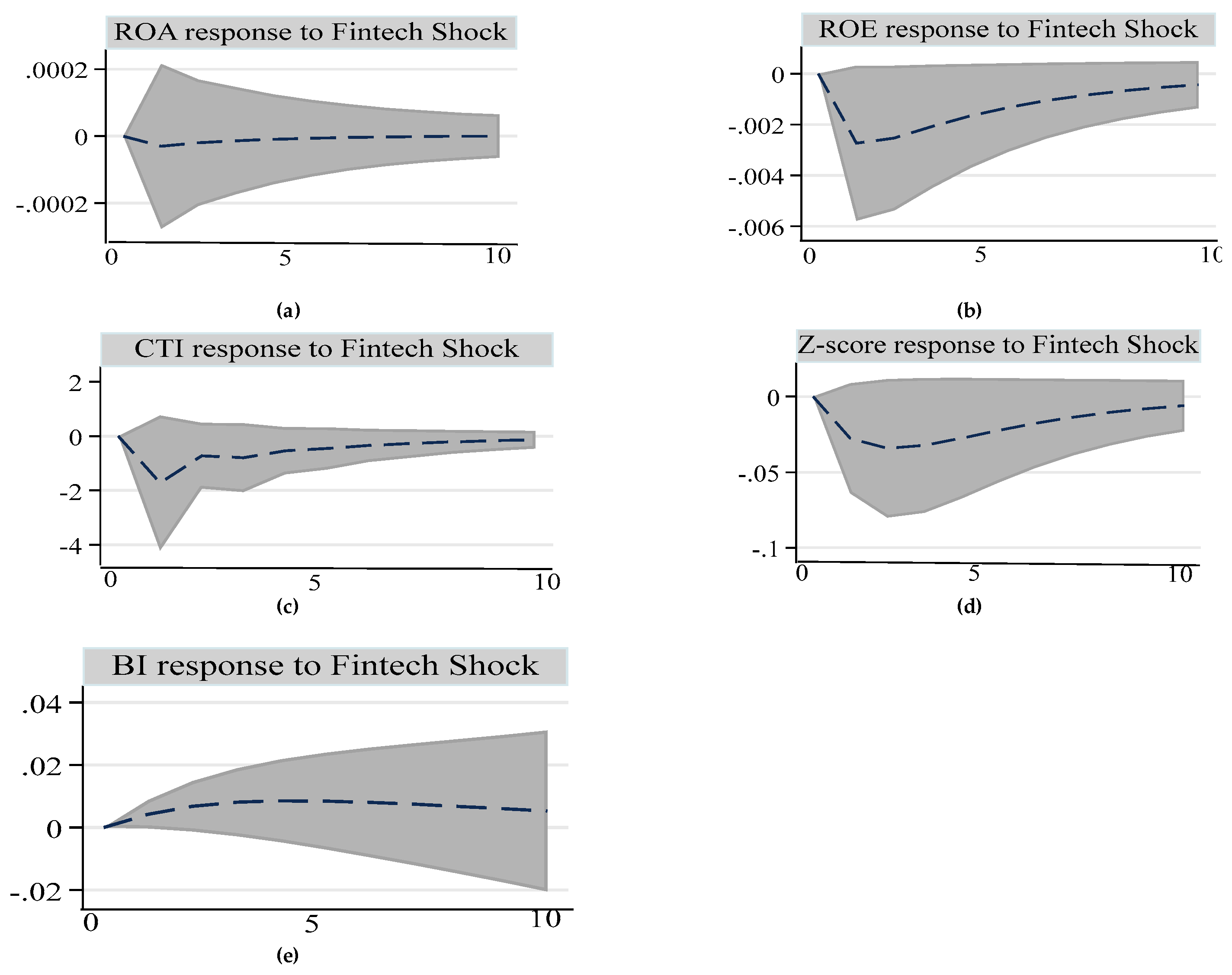

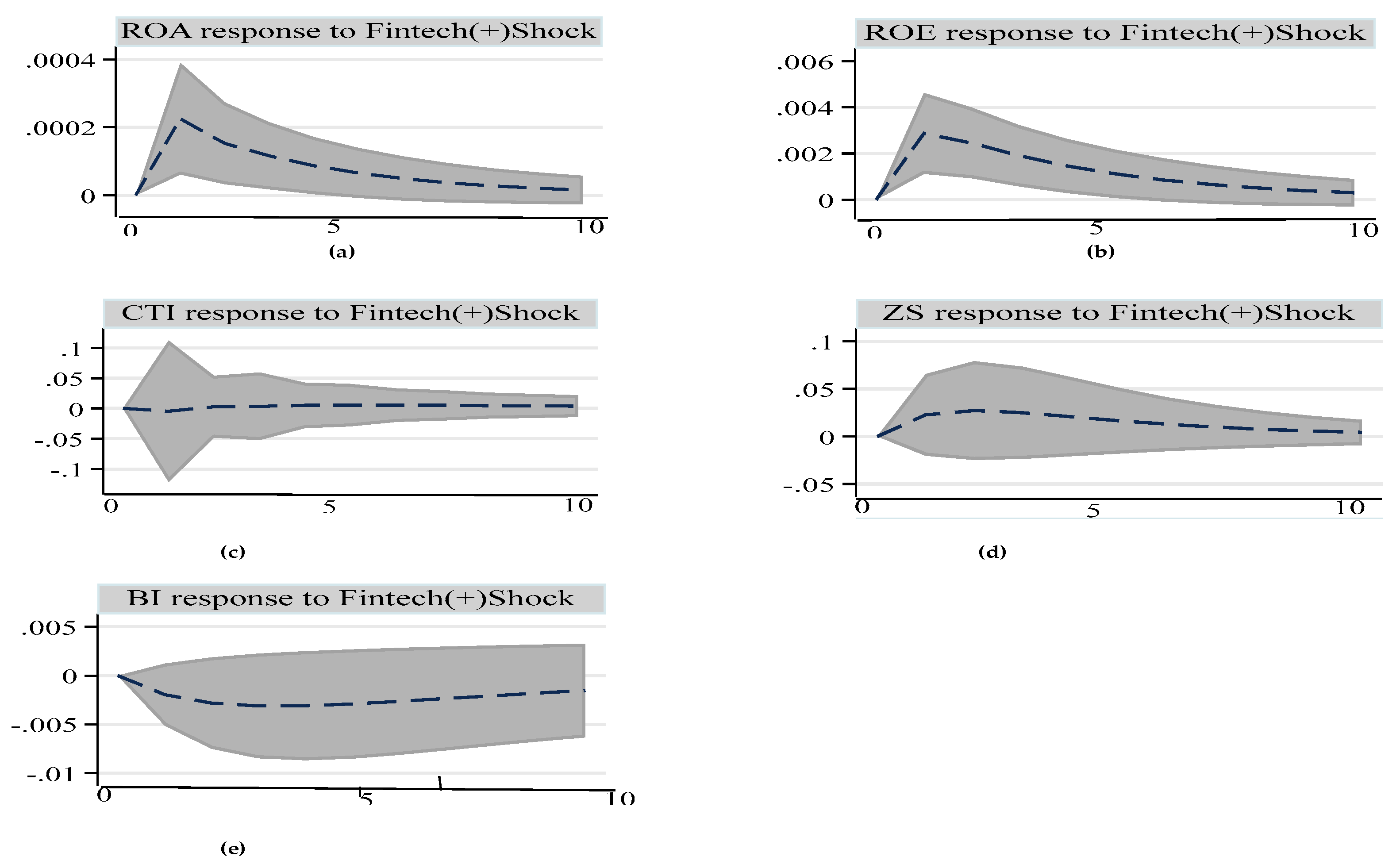

4.2. Results and Discussion

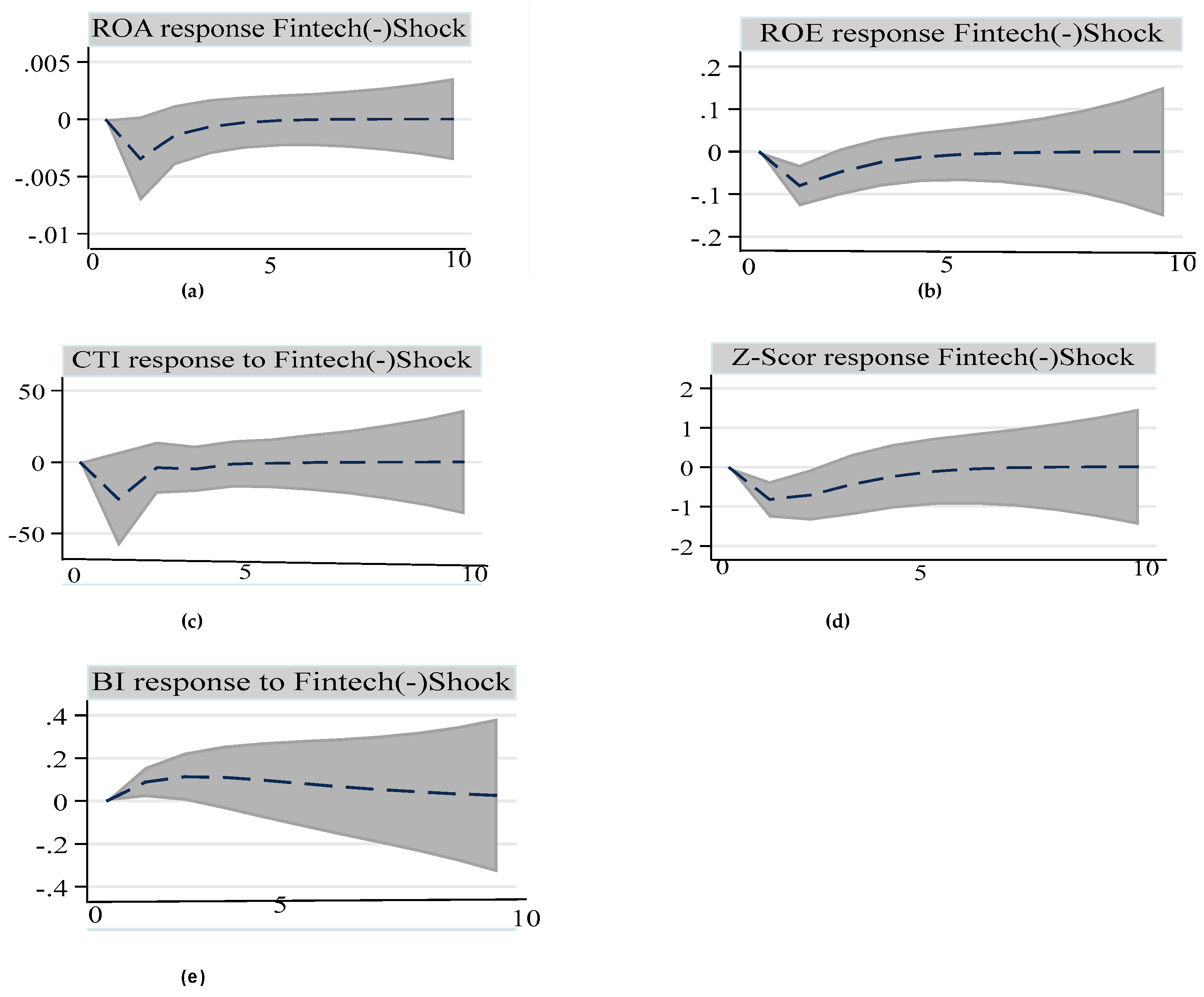

- Asymmetric effects of fintech risk on bank performance.

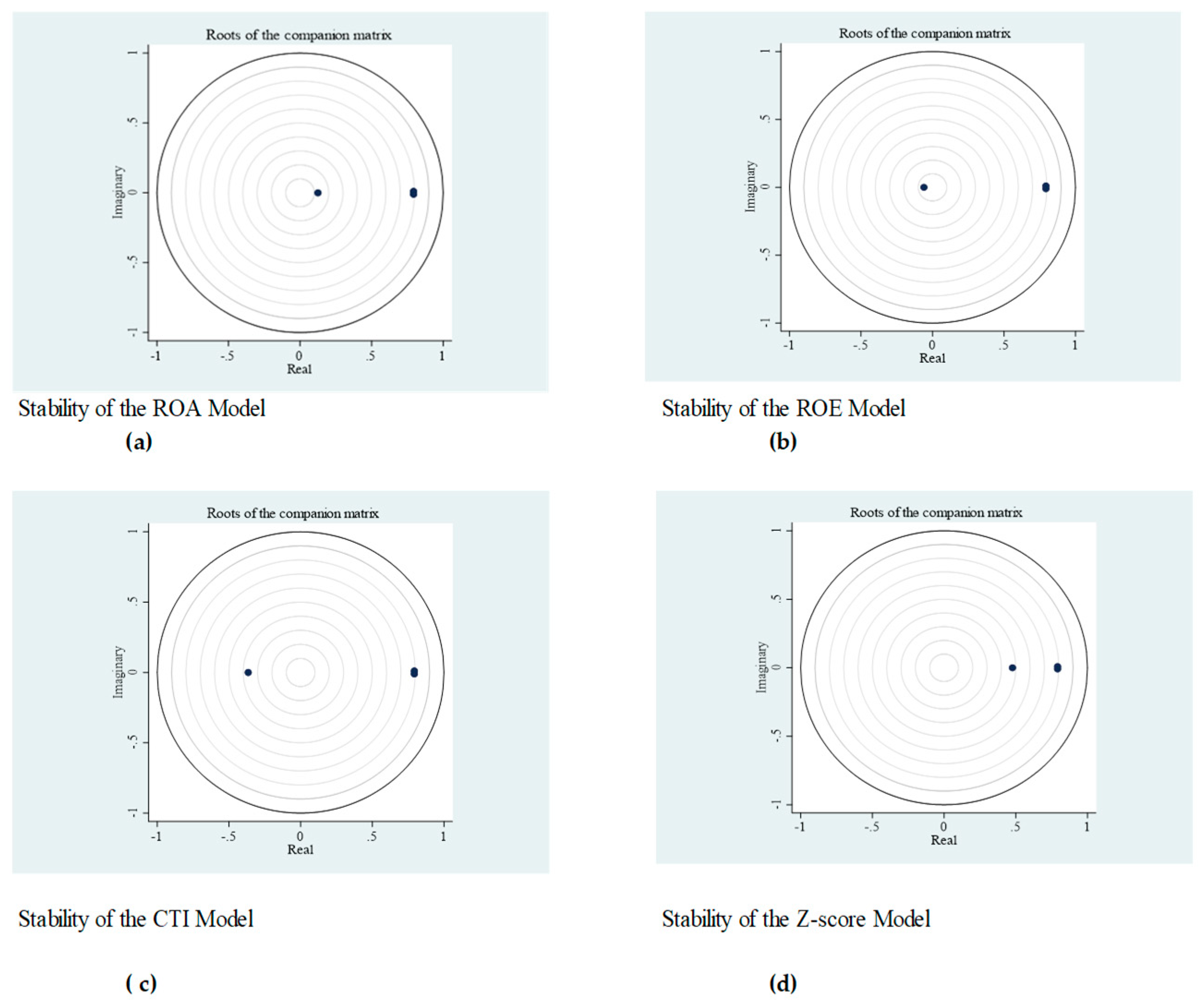

4.2.1. Diagnostic Tests: Stability of the Panel VAR Model

4.2.2. Robustness Check: Granger Non-Causality Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATMs | Automated Teller Machines |

| CFI | Co-operative Financial Institution |

| CTI | Cost to Income Ratio |

| FFSI | Fintech Financial Stress Indicator |

| Fintech | Financial Technology |

| MoMo | Mobile Money |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| PVAR | Panel Vector-Autoregressive process |

Appendix A

| Bank Performance Metrics | ||||

| GMM Estimates | ||||

| ROA | ROE | CTI | Z-Score | |

| ROA(t-1) | -0.0601 | |||

| (0.106) | ||||

| Fintech(t-1) | -0.00000784 | -0.000709* | -0.446 | -0.00715 |

| (0.0000346) | (0.000377) | (0.306) | (0.00544) | |

| BI(t-1) | 0.000510 | -0.0150 | -2.803* | 0.0799 |

| (0.00188) | (0.0117) | (1.527) | (0.146) | |

| ROE(t-1) | 0.125 | |||

| (0.106) | ||||

| CTI(t-1) | -0.365** | |||

| (0.183) | ||||

| Z-Score(t-1) | 0.473*** | |||

| (0.0425) | ||||

| GMM Estimates Competition |

||||

| ROA(t-1) | -0.0388 | |||

| (0.0601) | ||||

| Fintech(t-1) | 0.00111* | 0.00110* | 0.00111* | 0.00113* |

| (0.000599) | (0.000598) | (0.000599) | (0.000609) | |

| BI(t-1) | 0.809*** | 0.809*** | 0.809*** | 0.809*** |

| (0.124) | (0.124) | (0.124) | (0.123) | |

| ROE(t-1) | -0.0147 | |||

| (0.0172) | ||||

| CTI(t-1) | -0.00000172 | |||

| (0.00000921) | ||||

| Z-Score(t-1) | 0.00242 | |||

| (0.00664) | ||||

| N | 1312 | 1312 | 1312 | 1312 |

| Bank Performance Metrics GMM Estimates |

||||

| ROA | ROE | CTI | Z-score | |

| ROA(t-1) | -0.0755 | |||

| (0.0826) | ||||

| FintechP(t-1) | 0.0000515* | 0.000657** | -0.00104 | 0.00520 |

| (0.0000204) | (0.000213) | (0.0135) | (0.00464) | |

| BI(t-1) | 0.000161 | -0.0202 | -2.826 | -0.00145 |

| (0.00171) | (0.0128) | (2.031) | (0.122) | |

| ROE(t-1) | 0.0899 | |||

| (0.0551) | ||||

| CTI(t-1) | -0.359* | |||

| (0.179) | ||||

| Z-score(t-1) | 0.443*** | |||

| (0.0404) | ||||

| Competition GMM Estimates |

||||

| ROA(t-1) | -0.00698 | |||

| (0.0268) | ||||

| FintechP(t-1) | -0.000373 | -0.000367 | -0.000373 | -0.000447 |

| (0.000360) | (0.000360) | (0.000360) | (0.000362) | |

| BI(t-1) | 0.802*** | 0.802*** | 0.802*** | 0.801*** |

| (0.103) | (0.103) | (0.103) | (0.103) | |

| ROE(t-1) | -0.00898 | |||

| (0.00877) | ||||

| CTI(t-1) | 0.00000735 | |||

| (0.0000126) | ||||

| Z-score(t-1) | 0.00921 | |||

| (0.00748) | ||||

| N | 1312 | 1312 | 1310 | 1312 |

| Performance Metrics GMM Estimates |

||||

| ROA | ROE | CTI | Z-Score | |

| ROA(t-1) | -0.0736 | |||

| (0.0819) | ||||

| FintechN(t-1) | -0.00187 | -0.0432** | -14.04 | -0.445*** |

| (0.000994) | (0.0132) | (9.836) | (0.132) | |

| BI(t-1) | -0.000573 | -0.0371 | -8.443 | -0.168 |

| (0.00200) | (0.0202) | (6.721) | (0.211) | |

| ROE(t-1) | 0.105 | |||

| (0.0661) | ||||

| CTI(t-1) | -0.333 | |||

| (0.178) | ||||

| Z-Score(t-1) | 0.372*** | |||

| Competition GMM Estimates |

||||

| ROA(t-1) | -0.0504 | |||

| (0.0820) | ||||

| FintechN(t-1) | 0.0478* | 0.0468* | 0.0469* | 0.0565* |

| (0.0191) | (0.0187) | (0.0187) | (0.0220) | |

| BI(t-1) | 0.822*** | 0.821*** | 0.821*** | 0.822*** |

| (0.106) | (0.106) | (0.106) | (0.107) | |

| ROE(t-1) | -0.0247 | |||

| (0.0226) | ||||

| CTI(t-1) | -0.0000812 | |||

| (0.0000689) | ||||

| Z-Score(t-1) | 0.0182 | |||

| (0.00991) | ||||

| N | 1312 | 1312 | 1310 | 1312 |

| 1 | Banking Competition |

| 2 |

is the characteristic polynomial, and its roots are the eigenvalues. |

| 3 | The eigen vectors are linearly dependent, as for every computed eigenvalue, , we need to solve for non-zero such that |

| 4 | Where and .Hence the null hypothesis of unit root becomes . Moreover, , subsequently substituting back into Equation 17 one gets: as in Equation 16. |

| 5 | The models are also stable for positive and negative fintech risk shocks. |

References

- Ahmed, O. N. and Wamugo, L. (2018) ‘Financial Innovation and the Performance of Commercial Banks in Kenya’, International Journal of Current Aspects in Finance., IV(Ii), pp. 133–147.

- Allen, F. and Gale, D. (2004) ‘Competition and Financial Stability’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking., 36(3), pp. 453–480.

- Anarigide, D. A., Issahaku, H. and Dary, S. K. (2023) ‘Drivers of financial innovation in sub-Saharan Africa’, SN Business & Economics. Springer International Publishing, 3(9), pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D. W. K. and Lu, B. (2001) ‘Consistent model and moment selection procedures for GMM estimation with application to dynamic panel data models’, Journal of Econometrics, 101, pp. 123–164.

- Andries, A. M. and Capraru, B. (2014) ‘The nexus between competition and efficiency : The European banking industries experience’, International Business Review, 23, pp. 566–579. [CrossRef]

- Ashiru, O., Balogun, G. and Paseda, O. (2023) ‘Financial innovation and bank financial performance : Evidence from Nigerian deposit money banks’, Research in Globalization. Elsevier Ltd, 6(December 2022), p. 100120. [CrossRef]

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2024) Digitalisation of finance.

- Bejar, P., Ishi, K, Komatsuzaki, T, Shibata, I, and Sin, J. (2022) ‘Can Fintech Foster Competition in the Banking System in Latin America and the Caribbean ? ’, Latin American Journal of Central Banking. Elsevier B.V., 3(2), p. 100061. [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, J. and Bozou, C. (2024) ‘Desirable banking competition and stability’, Journal of Financial Stability. Elsevier B.V., 73(April), p. 101266. [CrossRef]

- Berryman, A. A. (1992) ‘The Origins and Evolution of Predator-Prey Theory’, Ecology, 73(5), pp. 1530–1535.

- Browne, J. (2019) Nigeria’s banking oligopolies : Case for review, Nigerian Tribune.

- Bu, Y, Du, X, Li, H, Yu, X, and Wang, Y. (2023) ‘Research on the FinTech risk early warning based on the MS-VAR model : An empirical analysis in China’, Global Finance Journal, 58(April), pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Canova, F. and Ciccarelli, M. (2013) 'Panel Vector Autoregressive Models: A Survey.' Working Paper No 1507.

- Chassang, S. and Ortner, J. (2023) ‘Regulating Collusion’, Annual Review of Economics, 15, pp. 177–204.

- Chipeta, C. and Mapela, L. (2024) The effects of Basel III capital and liquidity. South African Reserve Bank Working Paper Series-WP/24/17.

- Dong, Q., Du, Q. and Min, A. (2024) ‘Interplay between oil prices , country risks , and stock returns in the context of global conflict : A PVAR approach’, Research in International Business and Finance. Elsevier B.V., 72(PB), p. 102545. [CrossRef]

- Emery, D. R., Finnerty, J. D. and Stowe, J. D. (2017) Corporate Financial Management. 5th Edition. Morristown, NJ: Wohl Publishing.

- Fang, J., Lau, C.M., Lu, Z., Tan, Y., and Zhang, H. (2019) ‘Bank performance in China : A Perspective from Bank efficiency , risk-taking and market competition’, Pacific-Basin Finance Journal. Elsevier, 56(June), pp. 290–309. [CrossRef]

- Githinji, M. W. (2024) ‘Bank-Specific Charecteristics, Bank Concentration and Financial Distress of Commercial Banks in Kenya.’, International Academic Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(3), pp. 313–342.

- Greene, W. H. (2002) Econometric Analysis. 5th Edition. Prentice Hall.

- De Hoyos, R. E. and Sarafidis, V. (2006) ‘Testing for cross-sectional dependence in panel data models’, The Stata Journal, 6(Number 4), pp. 482–496.

- Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H. and Shin, Y. (2003) ‘Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels’, Journal of Econometrics, 115(9526), pp. 53–74. [CrossRef]

- Jia, K., He, Y. and Mohsin, M. (2023) ‘Digital financial and banking competition network : Evidence from China’, Frontiers in Psychology, (January), pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, B. A., Awad, A. B., Ahmed, O., and Gharios, R. (2023) ‘The Role of FinTech in Determining the Performance of Banks : The Case of Middle East & North Africa ( MENA ) Region’, International Journal of Membrane Science and Technology, 10(3), pp. 1525–1.

- KPMG (2022) Pulse of Fintech H2’21. Available at: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2022/02/pulse-of-fintech-h2-21.pdf.

- Kulu, E., Opoku, A., Gbolonyo, E., Anthony, M., and Kodwo, T. (2022) ‘ Mobile money transactions and banking sector performance in Ghana’, Heliyon. The Author(s), 8(May), p. e10761. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Feng, Q. and Li, H. (2024) ‘Digital finance , bank competition shocks and operational efficiency of local commercial banks in Western China.’, Pacific-Basin Finance Journal. Elsevier B.V., 85(April 2024), p. 102377. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L. and Weber, S. (2017) ‘Testing for Granger causality in panel data’, The Stata Journal, 17(4), pp. 972–984. [CrossRef]

- Lütkepohl, H. (2005) New Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis. Springer.

- Mabe, Q. M. and Simo-kengne, B. D. (2023) ‘Relative Importance of Time , Country and Bank-specific Effects on Bank Performance : A Three-Level Hierarchical Approach’, African Review of Economics and Finance, 15, pp. 1–25.

- Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M. D. and Green, J. R. (1995) Microeconomic Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Mhlongo, N., Kunjal, D. and Muzindutsi, P.-F. (2025) ‘The influence of Fintech innovations on bank competition and performance in South Africa’, Modern Finance, 3(2020), pp. 1–12.

- Murinde, V., Rizopoulos, E. and Zachariadis, M. (2022) ‘International Review of Financial Analysis The impact of the FinTech revolution on the future of banking : Opportunities and risks’, International Review of Financial Analysis. Elsevier Inc., 81(June 2021), p. 102103. [CrossRef]

- Mushonga, M., Arun, T. G. and Marwa, N. W. (2018) ‘Technological Forecasting & Social Change Drivers , inhibitors and the future of co-operative financial institutions : A Delphi study on South African perspective’, Technological Forecasting & Social Change. Elsevier, 133(April), pp. 254–268. [CrossRef]

- Nekesa, S. M. and Olweny, T. (2012) ‘Effect of Financial Innovation on Financial Performance: A Case Study of Deposit-Taking Savings and Credit Cooperative Societies in Kajiado County’, International Journal of Social and Information Technology, ISSN 2412=.

- Niehans, J. (1983) ‘Financial Innovation, Multinational Banking and Monetary Policy.’, Journal of Banking and Finance, 7, pp. 537–551.

- Okapor, C. (2023) 'Top Fintech Companies in Africa'., Business Insider Africa.

- Oriji, O., Shonibare, M. A, Daraojimba, R.E, Abitoye., O., and Daraojimbe, A. (2023) ‘Financial Technology Evolution in Africa: A Comprehensive Review of Legal Frameworks and Implications for AI-Driven Financial Services.’, International Journal of Management and Entrepreneurship Research, 5(12), pp. 929–951. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, F. (2019) SA’s banking oligopoly and the forex cartel, IOL. Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/analysis/sas-banking-oligopoly-and-the-forex-cartel-2654b258-1ebc-464e-9174-41352bc7ce68 (Accessed: 19 February 2025).

- Silber, W. L. (1983) ‘The Process of Financial’, American Economic Association, 73(2), pp. 89–95.

- Simo-kengne, B. D., Gupta, R. and Bittencourt, M. (2013) ‘The Impact of House Prices on Consumption in South Africa : Evidence from Provincial-Level Panel VARs ’, Housing Studies, (September), pp. 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Stata Corp (2023) Stata Statistical Software: Release 18., STATA Reference Manual. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Stigler, G. J. (1964) ‘A Theory of Oligopoly’, Journal of Political Economy, 72(1), pp. 44–61.

- Walyaula, A. (2007) List Of Fintech Startups In Kenya, Kahawa Tungu. Available at: https://kahawatungu.com/list-of-fintech-startups-in-kenya/.

- Wang, W., Feng, C. and Dang, X. (2021) ‘Research on the Impact of Market Competition on the Operating Performance of Rural Commercial Banks — Path Inspection Based’, in Xu, J. et al. (eds) Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management. Springer International Publishing, pp. 788–811. [CrossRef]

- Werker, C. (2003) ‘Innovation , market performance , and competition : lessons from a product life cycle model’, Technovation, 23, pp. 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Zamil, R. and Lawson, A. (2022) Gatekeeping the gatekeepers : when big techs and fintechs own banks – benefits , risks and policy options.

- Zhao, J., Li, X., Yu, C., Chen, S, and Lee., C (2022) ‘Riding the FinTech innovation wave : FinTech , patents and bank performance’, Journal of International Money and Finance. Elsevier Ltd, 122, p. 102552. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K. and Guo, L. (2024) ‘Financial technology , inclusive finance and bank performance’, Finance Research Letters. Elsevier Inc., 60(August 2023), p. 104872. [CrossRef]

- Zribi, W., Boufateh. T, Ben, B., and Urom, C. (2024) ‘Uncertainty shocks, investor sentiment and environmental performance : Novel evidence from a PVAR approach’, International Review of Financial Analysis. Elsevier Inc., 93(July 2023), p. 103196. [CrossRef]

| Model Parameters | Interpretations and Assumptions |

| The growth rate of cartel customers | |

| The diminishing rate of cartel customers when they interact with the violator customers | |

| The percentage rate of cartel customers that leave the cartel bank without any interaction with the violating banks’ customers. The assumption is that the customers who leave banks that conform with the cartel agreement, become the violators’ customers. | |

| The death rate of the violators’ customers or clients who switch to mattress banking. | |

| The growth rate of the violators’ customers when they interact with cartels’ customers |

| Metric type | Level 1 Indicators | Secondary Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Fintech Companies | Market Risk | MoMo growth rate |

| Stoxx Global Fintech volatility | ||

| Internet use | ||

| Deposits and loans with credit unions | ||

| Banking-Financial institutions | Digital operational risk | Automated Teller Machine (ATM) growth rate |

| Branches growth rate | ||

| Operational risk | Nonperforming loan ratio | |

| Capital adequacy ratio | ||

| Provision for loan loss reserves | ||

| Market risk | Liquidity ratio | |

| Net Interest Margin | ||

| Financial Market Volatility | ||

| Non-banking-Financial institutions | Securities market cycle risk | Treasury Bill rates |

| Peripheral services | Economic environment | Year-on-year CPI |

| GDP growth rate | ||

| Finance | Financial environment | Net loans-to-total deposit of financial institutions |

| External Environment | Technological environment | Secured Internet servers R&D growth rate |

| Network-environment/Cyber crime | Crime rate |

| Description | Variable | Source |

|---|---|---|

| The ratio of net income to equity | ROE | Thomson Reuters |

| The ratio of net income to total assets | ROA | Thomson Reuters |

| Cost to income ratio | CTI | Thomson Reuters |

| The difference between ROA and its mean over the standard deviation of ROA | Z-score | Derived by the author |

| Fintech Financial Stress Index | FFSI | Derived by the author |

| Factors | Component 1 |

|---|---|

| Loan to deposit ratio | 0.3589 |

| Leverage ratio | 0.2129 |

| Liquidity (current liability:current assets) | 0.2652 |

| Non-performing loans | -0.2713 |

| Net interest margin | 0.0741 |

| Tier 1 capital ratio | -0.299 |

| Loan loss reserves | -0.0029 |

| Market volatility | -0.0022 |

| Fin tech volatility | 0.0164 |

| Rate of change of MoMo transactions | -0.0833 |

| Rate of change in the number of bank branches | 0.2643 |

| Rate of change in the number of ATMs | 0.3254 |

| Internet use per 100 individuals | -0.3095 |

| Treasury bill rates | -0.2165 |

| Consumer Price Index (CPI) | 0.2552 |

| GDP | 0.2223 |

| Rate of change in the number of Secured internet servers | -0.0939 |

| Crime rate | -0.2709 |

| Research and Development | 0.0219 |

| Deposits in credit unions | 0.2308 |

| Loans issued by credit unions | -0.1046 |

| ROA | ROE | CTI | Z-score | FFSI | BI | |

| ROA | 1.000 | |||||

| ROE | 0.8165* | 1.000 | ||||

| CTI | 0.019 | -0.012 | 1.000 | |||

| Z-score | 0.3214* | 0.2259* | -0.039 | 1.000 | ||

| FFSI | 0.003 | -0.011 | 0.0704* | -0.008 | 1.000 | |

| BI | 0.018 | 0.0713* | -0.036 | -0.006 | 0.1910* | 1.000 |

| ROA | ROE | CTI | Z-Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis | Hypothesis | Hypothesis | ||||

| BI ROA | 0.074 | BI ROE | 1.65 | BI CTI | 3.37* | BI Z-score | 0.302 |

| Fintech ROA | 0.051 | Fintech ROE | 3.537* | FintechCTI | 2.118 | Fintech Z-score | 1.729 |

| ROA BI | 0.416 | ROE BI | 0.733 | CTI BI | 0.035 | Z-score BI | 0.133 |

| Fintech BI | 3.44* | Fintech BI | 3.389* | Fintech BI | 3.427 | FintechBI | 3.427* |

| ROA Fintech | 0.089 | ROE Fintech | 0.201 | CTI Fintech | 0.165 | Z-score Fintech | 0.512 |

| BI Fintech | 0.93 | BI Fintech | 0.916 | BIFintech | 0.932 | BI Fintech | 1.23 |

| Positive Fintech | Positive Fintech | Positive Fintech | Positive Fintech | ||||

| BI ROA | 0.009 | BI ROE | 2.497 | BI CTI | 1.936 | BI Z-score | 0.002 |

| Fintech ROA | 6.394*** | Fintech ROE | 9.542** | Fintech CTI | 0.006 | Fintech Z-score | 1.255 |

| ROA BI | 0.068 | ROE BI | 1.049 | CTI BI | 0.338 | Z-score BI | 1.515 |

| Fintech BI | 1.074 | Fintech BI | 1.041 | Fintech BI | 1.075 | Fintech BI | 1.522 |

| ROA Fintech | 1.507 | ROE Fintech | 1.661 | CTI Fintech | 2.165 | Z-score Fintech | 0.042 |

| BI Fintech | 0.215 | BI Fintech | 0.292 | BI Fintech | 0.243 | BI Fintech | 0.042 |

| Negative Fintech | Negative Fintech | Negative Fintech | Negative Fintech | ||||

| BI ROA | 0.082 | BI ROE | 3.367* | BI CTI | 1.578 | BI Z-score | 0.639 |

| Fintech ROA | 3.527* | Fintech ROE | 10.664** | Fintech CTI | 2.038 | Fintech Z-score | 11.297*** |

| ROA BI | 0.378 | ROE BI | 1.195 | CTI BI | 1.386 | Z-score BI | 3.367* |

| Fintech BI | 6.262*** | Fintech BI | 6.271** | Fintech BI | 6.28** | Fintech BI | 6.591*** |

| ROA Fintech | 0.24 | ROE Fintech | 0.105 | CTI Fintech | 0.041 | Z-score Fintech | 0.113 |

| BI Fintech | 1.193 | BI Fintech | 1.25 | BI Fintech | 1.235 | BIFintech | 1.174 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).