Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Types and Roles of AI Agents in Education

- Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS): These agents most likely represent the most famed sorts designed to simulate one-on-one human tutor interaction. An ITS analyzes a student-declared knowledge state and provides instruction catered to the student's needs, offering hints and feedback as well as selecting the most suited problems or activities to work on [10,11]. Usually, these would be agents that concentrate on one subject, like mathematics or physics, and then vary the problem's difficulty accordingly while providing step-by-step help [12].

- Pedagogical Agents: Animated characters or avatars that act as learning companions, guides, or motivators within a learning environment [7]. They may teach, motivate, demonstrate, and/or converse with the learner to enhance engagement and provide a more supportive setting [13]. Efficacy might depend on the character agent's appearance, voice, and perceived personality [14].

- Conversational Agents (Chatbots): These agents use natural language processing to hold a conversation with a learner, either in text or by voice. They can answer questions, explain things, offer practice, or lead a learner through content [15]. Increased use of chatbots for administrative questions, FAQ support, and basic content delivery has fueled their speed and scale of interaction [16].

- Adaptive Assessment Agents: These agents vary the difficulty and type of assessment items based on a dynamic view of learner performance [8]. This makes for a more efficient and accurate evaluation of a student's mastery level than static tests, and the immediate feedback offered can be tailored to an individual student's improvement areas [17].

- Automated Feedback and Grading Agents: These agents use AI—particularly natural language processing and machine learning—to automate feedback on written assignments, code, or other submissions. Potentially, they can also capture common errors, provide suggestions for improvements, and even assign preliminary grades, thereby freeing the instructor for meaningful engagement [5,18].

- Affective Computing Agents: More advanced, these agents aim to detect and respond to a learner's emotional state (e.g., frustration, confusion, engagement) based on facial expressions, vocal tones, or interaction patterns [19]. The agent's response will then modify its pedagogical strategy in light of the student's affect with a view to improve motivation and learning outcomes [20].

2.2. Benefits of AI Agents in Education

- Personalization and Adaptation: AI is particularly good at tailoring the learning experience to each student regarding individual need, timing, and style [1,11]. They customize relevant content, appropriate activities, and levels of challenge depending upon assessment of the processed performance data, hence yielding better learning outcomes [12].

- Increased Engagement and Motivation: Interactive agents, especially pedagogical and conversational agents, enhance student engagement and reduce solitude in learning experiences [13,16]. Novelty in interaction, accompanied by attention to unique individual needs, creates sustained student interest and motivation [7].

- Instantaneous and Personalized Feedback: Agents can provide up-to-second, specific feedback about student performance, which often is a challenge for human instructors in large classes [8,18]. Such immediate feedback can aid students in pinpointing and rectifying errors, thus reinforcing correct understanding [17].

- Scalability and Accessibility: Whereas an AI agent can offer personalized interaction and support to a massive number of students at the same time, the presence of an instructor becomes inhibitive for that scale due to limited availability [9]. Such an arrangement will further make personalized learning more scalable and potentially accessible among diverse groups of people [5].

- Data Collection and Analytics: Agents can collect such detailed data continuously on student interactions, performances, and learning processes [1,8]. The data gathered might be analyzed for insights into learning trends, identification of students with difficulties, and enriching the pedagogical tool for the agent and human instructor alike [2].

- Instructor Support: AI agents set the stage for 'doing the heavy lifting' to allow faculty to engage in high-order activities like curriculum design, facilitating discussions, and giving personalized attention to student needs of an intricate sort by essentially tapping grading, providing basic explanations, and tracking student progress [5,9].

2.3. Challenges and Limitations

- Cost and Complexity of Development: Developing effective and robust AI agents, particularly sophisticated ITS or affective computing agents, is an endeavor that calls for much expertise and money to invest [9].

- A Place for Human Intervention: AI agents are tools to assist in learning, not to replace human interaction entirely [24]. Human teachers provide situations requiring social-emotional support, mentorship, and the handling of complex and nuanced occurrences that agents cannot handle [2]. The implementation of agents with teacher role redefinition, not elimination, becomes imperative [5].

- Technical Issues and Infrastructure: The proper technical infrastructure, internet connectivity, and support for reliable implementations may not always be available [9].

2.4. Comparative Analysis: AI Agents vs. Traditional Teaching Methods [26,27]

| Aspect | Traditional Teaching | AI Agents |

| Personalization | Limited due to teacher-student ratio; It is difficult to do personal. | High; AI adopts material and speed for personal requirements. |

| Feedback | Delayed, especially in large classes. | The instantaneous, wide and personal response. |

| Scalability | Challenge with increase in student number. | Easily scalable; An AI can help thousands of people simultaneously. |

| Human Interaction | High emotional intelligence, mentorship, social education | Limited sympathy and social connections (although improvement with affection computing). |

| Cost | High labor costs for small square size. | Higher early development costs but additional students per less marginal cost. |

| Adaptability | Slow to adjust materials and methods for student needs. | Dynamically adjusts the level of learning paths and difficulty in real time. |

| Engagement | Depends heavily on teacher skill and class dynamics. | Interactive agents, gamification, and novelty can enhance engagement, but can also cause novelty fatigue. |

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Proposed Research Design

3.2. Participants

- Experimental Group: Students using an AI agent (e.g., intelligent tutoring system or conversational agent which provides practice and feedback) as an additional resource for learning.

- Control Group: Students receiving typical instruction and available standard course resources without the AI agent.

3.3. Intervention

3.4. Data Collection

-

Quantitative Data:

- ○

- Student Learning Outcomes: Evaluation of knowledge acquisition and skill development is done using pre- and post-intervention tests/assessments. Performance data from assignments and exams throughout the study are also useful.

- ○

- Engagement: Data logging by the AI agent system (i.e., time using the agent, frequency of interactions with it, types of activities involved). Surveys to assess levels of student engagement (possibly through validated scales), among other measures.

-

Qualitative Data:

- ○

- Student Perceptions: Semi-structured interviews or focus groups with students forming the experimental group to tap into their experiences related to the AI agent, especially perceived benefits, and impediments, and its impact on learning.

- ○

- Instructor Perceptions: Interviews with a course instructor to gain insight into their observations of student use of the agent, its impact on classroom dynamics, and challenges can afford instructors opportunities.

3.5. Data Analysis

- Quantitative Analysis: Statistical techniques (including t-tests, ANOVA, etc.) will be applied for comparative learning attainment and engagement measure metrics for experimental and control groups. The correlation analysis would look at the relationship between agent usage and performance.

- Qualitative Analysis: Interview and focus group transcripts would be thematically analyzed to allow for the identification of pervading themes, patterns, and perspectives relating to the impact of the AI agent.

- Mixed Methods Integration: Quantitative and qualitative data findings would provide a more comprehensive understanding of agent impact using qualitative insights to explain statistical findings.

4. Experiment

- How does the supplemental use of an AI-powered conversational agent affect student learning outcomes (currently measured by the performance in assignments and exams) for the introductory programming course as compared to traditional resource use?

- Does the AI-powered dialog agent lead to higher levels of engagement with students as measured in an introductory programming class?

- Perceptions of students or instructors related to the effectiveness and impact of the AI-powered conversational agent.

- Quantitative: Data were collected through ruthless examination of midterms and finals exam results; scores on four major programming assignments throughout the semester; logs of agent usage (for the experimental group): frequency of interactions, types of queries, session duration; a Student Engagement Survey (adapted from the National Survey of Student Engagement-NSSE, focusing on active and collaborative learning, student-faculty interaction, and technology-related support) which was administered at the end of the semester.

- Qualitative: Data were collected via semi-structured interviews with 20 experimental group students randomly selected at the end of the semester. The tips would also conduct semi-structured interviews with instructors and teaching assistants at the end of the semester.

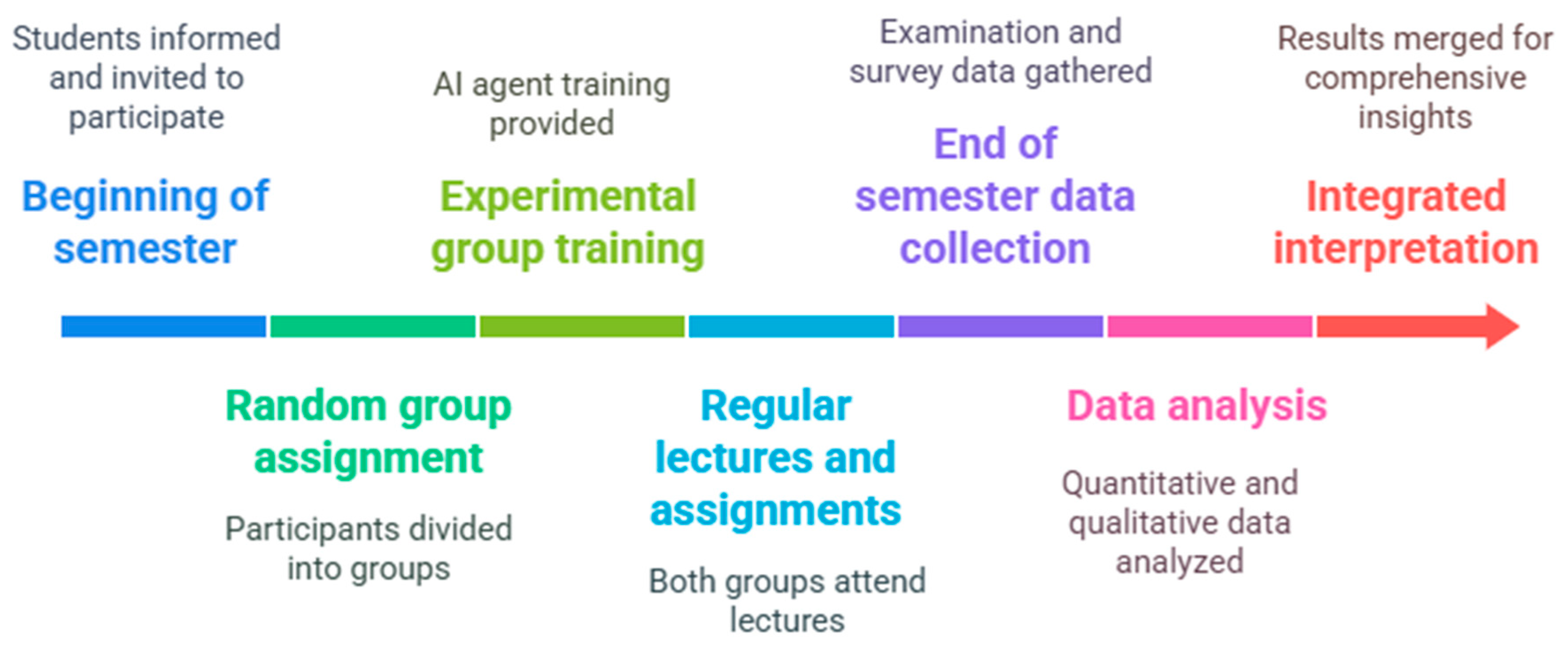

- Students will be informed about the study at the beginning of the semester and invited to participate with informed consent.

- Participants will be randomly assigned to groups.

- The experimental group will be trained in using the AI conversational agent and will be provided with instructions and access to the AI conversational agent.

- Throughout the course of the semester, both groups would regularly attend lectures, complete assignments and prepare for exams. The experimental group would interact with the agent as a supplementary learning resource, as and when they found it useful.

- Post-semester data would be collected through examination scores, assignment scores, agent log records for the experimental group, student survey responses, and student interviews.

- The quantitative data will analyze using some software for statistical analysis.

- The qualitative data will transcribe and subjected to thematic analysis.

- The results from both qualitative and quantitative data would be merged for an integrated interpretation.

5. Result and Discussion

5.1. Potential Results Based on Literature

- Learning Outcomes: Statistically significant improvements in average assignment and exam scores might be observed in the experimental group when contrasted to the control group [12]. Aiding the understanding and retention of concepts by providing prompt practice and feedback on specific programming concepts and error messages likely accounts for such an improved performance [17]. Students who were more interactive, or spent more time with the agent, might show far more gains [11].

- Engagement Levels: Compared to the control group, the experimental group is likely to show greater self-reports of engagement in active learning and use of technology captured in the post-semester survey [13]. The agent's open availability for answering questions beyond scheduled office hours and non-judgmental approach foster frequent interaction, practice, and much more engagement within the course content [16]. Usage logs for the agent would yield an array of use levels within students, possibly between their pre-existing motivation to learn or perceived requirement of help.

- Student Perceptions: The qualitative data are collected through interview of students and most likely on different perceptions. A lot of students might mention being pleased with the agent's availability or quick responses or even how the agent could explain the same concept in different ways [15]. They may even mention how helpful it was in debugging or practicing syntax. However, some might express disappointment at how they feel the agent cannot help with complex queries or simply that students prefer human-to-human interaction for complete understanding or to approach particularly difficult problems [24]. There might also be concerns on privacy over the collection of data [21].

- Instructor Perceptions: The instructors and TAs might see a decrease in repetitive basic questions during office hours or online forums and thus assume that the agent is doing its job well in addressing common inquiries [5]. They could see the students engaging with the agent being better prepared for class discussions or handling harder problems, while at the same time pointing out that this can lead to students depending too much on the agent at the expense of their problem-solving skills, some inaccurate or misleading information from the agent [23]. The need for seamless integration of the agent into the existing course structure and the training and upkeep efforts required for the maintenance of the agent will probably be stressed [9].

5.2. Discussion of Potential Implications

- Complementary, Not Replacement: The outcomes would likely further reinforce the argument that the agent is a very useful supplement and not a replacement for- human instruction [24]. As critical qualitative data, it illustrates those placements where human intervention is still important with resentful completion in cases of complex or emotionally charged issues [2].

- Equity and Access: The agent's scalability will provide equity; it is an essential feature, especially establishing equitable access to technology and digital literacy [9]. This would require assessing probable discrepancies among the student demographic in using or benefitting from the agent.

- Teacher Role Evolution: Basic inquiry agents may now free instructors to spend time on more vital activities like coaching collaborative learning and mentoring students, as well as dealing with higher thinking skills [5]. And educators must really be trained in how to ensure effective use of AI agents within their pedagogy.

6. Future Scope

- Collaborative Agents: For example, agents that can help facilitate collaborative learning activities by managing group dynamics, prompting discussions, and offering support to a team of students [7].

- AI Educational Agents: A tailor-made set of AI agents designed specifically for aiding teachers in functions beyond grading: making recommendations on instructional strategies based on educational data mining; designing the curriculum; and identifying students who might be at risk [5].

- Explainable AI in Education: This entails research geared towards ensuring transparency of the decision-making processes of educational AI agents to both students and instructors, thereby engendering trust while providing insights regarding the recommendations made by the agent or feedback it gives [23,25].

- Long-term Impact Studies: Conduct longitudinal studies over time, assessing the long-term implications of interacting with AI agents on a student's learning habits, self-regulation skills, and dispositions toward learning [1]. Establishing substantive ethical frameworks, guidelines, and policies for the design, deployment, and use of AI agents in educational settings, with considerations for privacy, bias, equity, and accountability [21,22].

- Personalized Agent Personalities: This research will consider how agent personalities, appearances, and communication styles can affect student engagement and learning outcomes, factoring in cultural and individual differences [14].

- Synergy with Emerging Technologies: In conjunction with emerging technologies such as VR and AR, AI agents can help sculpt immersive and highly interactive learning experiences [6].

7. Conclusion

References

- Chen, X.; Xie, H.; Hwang, G.-J. Fifty years of artificial intelligence in education: Insights from a meta-analysis. Computers & Education 2020, 157, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. Boston, MA: Center for Curriculum Redesign, 2019.

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W.; Griffiths, M.; Forcier, L.B. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education. Doha: World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE), 2016.

- Russell, S.J.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010.

- Baker, R.S.; Siemens, G. "Educational data mining and learning analytics," in Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 2nd ed. R. K. Sawyer, Ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 253–274.

- Hwang, G.-J.; Tu, N.T. Roles and research trends of artificial intelligence in education: A review of the top 50 most cited articles in the SSCI category of 'Education & Educational Research'. Interactive Learning Environments 2021, 29, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.L.; Rickel, J.W.; Lester, J.C. Animated pedagogical agents: Face-to-face interaction in interactive learning environments. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2000, 11, 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Coniam, D. The use of artificial intelligence in marking and giving feedback on writing. J. Writing Res. 2016, 8, 517–552. [Google Scholar]

- Popenici, S.A.; Kerr, S. Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2017, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanLehn, K. The architecture of intelligent tutoring systems: A review and analysis. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2006, 16, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, B.P. Building Intelligent Interactive Tutors: Student-Centered Strategies for Revolutionizing E-Learning; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, A.T.; Anderson, J.R. Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 1995, 4, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.; Traum, D. Social artificial intelligence agents in education: Opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2019, 29, 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Baylor, A.L.; Ryu, J. The effects of pedagogical agent persona on student interest and learning. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2003, 28, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranoliya, B.R.; Raghuwanshi, M.M.; Singh, S. "Chatbot for university related FAQs," in Proc. 2017 Int. Conf. Adv. Comput. Commun. Informatics (ICACCI), pp. 1525–1529.

- Smutny, P.; Schreiberova, P. Chatbots for learning: A review of educational chatbots for the Facebook Messenger platform. Computers & Education 2020, 151, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shute, V.J. Stealth assessment in computer-based games to support learning. Computer-Based Games and Simulations in Education 2011, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Deane, P.; van der Kleij, F. System architecture and psychometric models for automated assessment of argumentative writing. J. Writing Res. 2015, 7, 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R.W. Affective Computing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- S. K., D'Mello; Graesser, A.C. Dynamics of affective states during complex learning. Learning and Instruction 2014, 29, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sellen, A.; Rogers, Y.; Harper, R.; Rodden, T. The AI Book: The Artificial Intelligence of Everything; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI; Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Popenici, S.A.S. AI in education: Current trends, opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Innovative Res. Inf. Security (IJIRIS) 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cuban, L. Oversold and Underused: Computers in the Classroom; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A.K. Explainable AI in education: From adaptive learning to personalized explanations. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2020, 63, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Rochelle & Dr. Sushith. (2024). Exploring the AI Era: A Comparative Analysis of AI-Driven Education and Traditional Teaching Methods. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research (IJFMR), Volume 6, Issue 4, July-August 2024.

- Shahid, A.; Hayat, K.; Iqbal, Z.; Jabeen, I. Comparative Analysis: ChatGPT vs Traditional Teaching Methods. Pakistan Journal of Society, Education and Language (PJSEL) 2023, 9, 585–593. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).