2. Theoretical Hypotheses

2.1. Impact of Urban Compactness on GTFP

A compact city is characterized by high density, mixed and diverse land-use functions, efficient and pedestrian-friendly transportation, and socio-economic diversity. It influences GTFP primarily through four dimensions: economic activity, population, land use, and transportation.

First, economic activities in compact cities are highly concentrated, creating economic agglomeration. Such agglomeration accelerates the concentration of firms and labor in the central city, reducing information asymmetry within the urban economy and thereby facilitating faster matching of production factors and improving productivity [

27]. Moreover, large-scale agglomeration can generate economies of scale through shared production equipment and facilities, further enhancing the efficiency of resource allocation [

19]. Economic agglomeration not only concentrates firms and people but also leads to more compact and diverse land use, increasing land-use efficiency and average land output value, which boosts economic performance and in turn raises GTFP [

29]. Additionally, higher-density cities tend to cluster industrial and commercial activities within the urban core, enabling more centralized energy supply, improving energy-use efficiency, and thus enhancing urban GTFP.

Second, compact cities generate scale effects in the urban core through the concentration of talent, capital, and resources. The aggregation of skilled labor and financial capital fosters knowledge spillovers that drive technological innovation and optimize urban industrial structure \[

30]. For example, the clustering of manufacturing can accelerate green technological progress and improve green economic efficiency, thereby enhancing pollution control technologies, reducing the environmental impact of industrial emissions, and increasing GTFP. However, if labor, capital, and other factors become overly concentrated without adequate management, they may exceed the city’s environmental carrying capacity and adversely affect urban sustainability [

19].

Third, compact urban spaces feature higher accessibility and spatial proximity, providing cities with dense road networks that improve connectivity between functional zones and enhance transport efficiency. From another perspective, pedestrian-friendly, dense street layouts help reduce private car usage, yielding environmental benefits and boosting GTFP.

From the above analysis, compact cities improve infrastructure and energy-use efficiency through the agglomeration of economic activities, talent, capital, resources, and through compact spatial and road networks; they promote the optimization of urban industrial structure and foster green technological innovation; and they enhance land-use efficiency. However, beyond a certain threshold, such concentration may negatively impact urban ecology and energy conservation and emission reduction. Hence, we propose Hypothesis 1: Within a certain range, increases in urban compactness have a positive effect on GTFP.

2.2. Mediating-Effect Analysis

2.2.1. The Driving Effect of Urban Compactness on Green Technological Innovation

By increasing land-use density and adopting an intensive spatial layout, enhanced urban compactness raises land costs and intensifies resource competition, thereby forcing traditional, low-value-added, high-energy-consumption industries (e.g., conventional manufacturing) to transform. At the same time, it attracts knowledge-intensive, technology-intensive, and service-oriented industries to cluster, promoting an upgrade of the industrial structure toward higher-end and lower-carbon activities.

Moreover, greater compactness shortens the physical distance between firms, facilitating the frequent flow of talent, technology, and information. This fosters the formation of innovation networks and industrial clusters, accelerates technology diffusion and industrial synergies, and lays a technological foundation for the development of high-tech, energy-saving, and emission-reduction industries as well as modern service sectors.

In addition, through the adoption of specific policies, increased urban compactness promotes more efficient land use and facilitates centralized investment in green infrastructure. Policy measures and market mechanisms—such as imposing carbon taxes and establishing industry-entry standards to phase out outdated capacity—can guide capital toward green industries [

31].

2.2.2. Pathways by Which Green Technological Innovation Enhances GTFP

High-end industries have a strong demand for green technology upgrades, typically featuring higher energy-use efficiency and lower pollution-emission intensity. Their technology spillover effects can stimulate green innovation across the entire economic system and optimize the allocation of production factors [

32]. Moreover, the service and knowledge sectors rely less on natural resources and more on human capital and digital technologies; this shift in factor structure directly lowers the environmental cost per unit of output, thereby promoting GTFP growth.

On the other hand, industrial upgrading is generally accompanied by both vertical integration and horizontal collaboration within the value chain. Through resource sharing and waste recycling models, industries can achieve emission reductions and resource regeneration at scale, and further enhance production efficiency via shared technologies and supporting infrastructure [

33].

2.2.3. The Mediating Role of Green Technological Innovation between Urban Compactness and GTFP

As a mediating variable, green technological innovation links compact cities and GTFP primarily through two mechanisms: structural emission reduction and the innovation multiplier effect.

Structural Emission Reduction

An increased share of high-value-added industries helps lower energy consumption and carbon-emission intensity per unit of GDP. Thus, optimizing the industrial structure via green technology upgrades is more conducive to energy conservation and emission reduction, easing environmental pressures and enhancing urban GTFP.

Innovation Multiplier Effect

In compact cities, knowledge-intensive industries (such as digital services and clean-energy technologies) tend to be relatively concentrated. Green innovations emerging in these sectors not only boost efficiency within their own industries but also, through scale effects and technology diffusion, benefit traditional industries and drive green technological progress across the entire region.

Accordingly, Hypothesis 2 is proposed: Green technological innovation serves as a mediating variable in the impact of urban compactness on GTFP.

2.3. Heterogeneity in the Impact of Urban Compactness on GTFP

Cities with higher and lower levels of economic development exhibit different effects of compactness on GTFP, which may stem from variations in resource allocation efficiency, industrial base, and innovation-absorption capacity. In economically advanced cities, more developed transport infrastructure and a higher-level industrial structure reduce commuting costs through increased transport efficiency, helping to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Under such advanced industrial structures, greater urban compactness facilitates industrial agglomeration, promotes the diffusion and absorption of green technologies, and enhances resource allocation efficiency, so that the net effect of compactness on GTFP tends to be positive. In contrast, in cities with lower levels of economic development, infrastructure is often underdeveloped and pillar industries remain in the secondary sector transition phase, weakening their capacity to adopt green technologies and industries. Moreover, these cities typically face weaker fiscal positions, with limited revenues directed toward basic infrastructure and public services, leaving little room to support emerging green industries and even risking a crowding-out effect. Therefore, we expect urban compactness to have a negative impact on GTFP in lower-development contexts.

Accordingly, Hypothesis 3 is proposed: The impact of urban compactness on GTFP exhibits heterogeneity across different levels of economic development.

2.4. Threshold Effect

The impact of urban compactness on GTFP may be nonlinear, reflecting differing stages of industrial development across cities. In the early stage of industrialization—when the industrial structure is dominated by inefficient, high-energy-consumption, and heavily polluting traditional industries—a compact urban form may exacerbate pollution, thereby weakening any positive effect on GTFP. Cities with a low share of industrial output also lack incentives for technological upgrading, and a compact layout may instead reinforce firms’ dependence on low-cost land and labor, potentially suppressing green innovation. Once industrial development reaches a certain level, with complete supporting facilities and reserves of capital and technology, green technological upgrading becomes more feasible. In such compact urban spaces, industrial agglomeration and scale effects are more pronounced, and green technology upgrades easily produce diffusion effects that more significantly boost GTFP. Based on these inferences, we propose Hypothesis 4: The effect of urban compactness on GTFP exhibits a threshold effect with respect to the share of industrial output value.

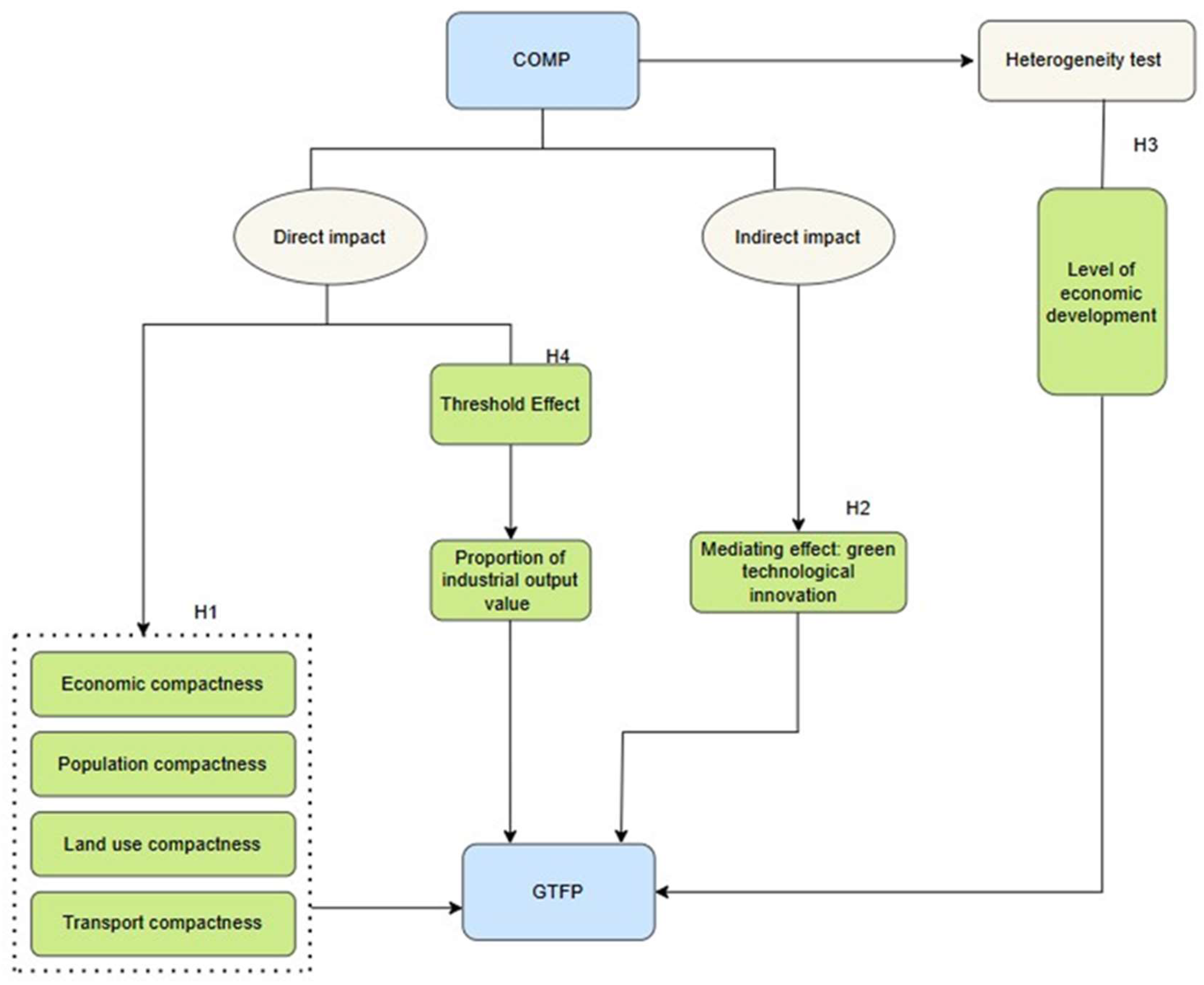

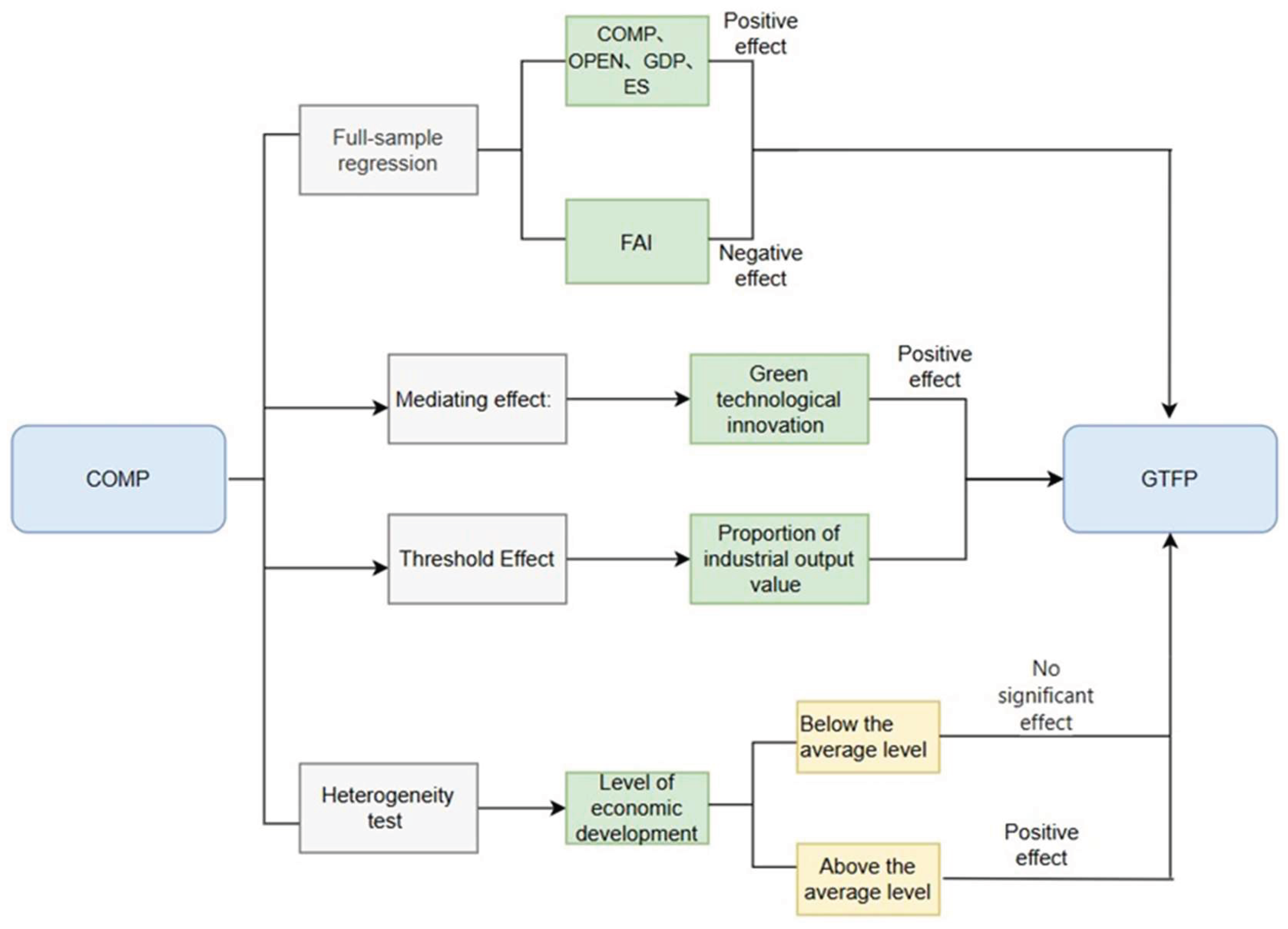

The theoretical framework of this study is illustrated in

Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Research Design

3.1. Variable Selection and Indicator System Construction

(1) Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study is Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP), which is measured using an SBM model and requires both input and output indicators. The SBM model can incorporate undesirable outputs into the GTFP estimation, thereby allowing for a more accurate assessment of urban GTFP levels.

Input Indicators:

Labor input: represented by the average number of on-the-job employees in each region.

Capital input: represented by the fixed-capital stock of each prefecture-level city.

Resource input: represented by the total electricity consumption of each prefecture-level city.

Output Indicators:

Desired output: Real gross domestic product.

Undesirable outputs: industrial wastewater discharge, industrial sulfur dioxide (SO₂) emissions, and industrial smoke (dust) emissions [

34].

The resulting indicator system for measuring GTFP is presented in

Table 1.

(2) Key Explanatory Variable

In this study, urban compactness serves as the key explanatory variable. To ensure scientific rigor, we draw on previous research and construct an indicator system measuring urban compactness from four dimensions: economic compactness, population compactness, land-use compactness, and transportation compactness. The specific indicators are detailed in

Table 2.

(3) Control Variables

A Openness to Foreign Investment

Foreign capital inflows, driven by the pursuit of higher economic returns and shaped by local regulatory constraints, tend to target technology-intensive and environmentally friendly industries that employ more efficient green production technologies. Their entry into local markets often intensifies competition, compelling domestic firms to allocate additional resources toward improving green technological capabilities, thereby enhancing urban GTFP. We measure openness to foreign investment by the amount of actual utilized foreign capital. In the empirical analysis, we take the natural logarithm of this variable. The expected effect of actual utilized foreign capital on GTFP is positive.

B Government Fiscal Decentralization

Compared with the overall economic development level of Chinese cities, the cities in our study area lag behind, resulting in relatively limited tax revenues. Most fiscal expenditures are allocated to social welfare, infrastructure, and other basic projects, leaving little capacity to support the development of green, innovation-driven industries. Moreover, these cities, located in China’s inland Southwest, attract comparatively low levels of foreign investment, exhibit lower degrees of market liberalization, and experience higher degrees of government intervention, all of which constrain firms’ autonomy in exploring diversified innovation pathways. We measure the degree of fiscal decentralization by the ratio of government general revenue to government general expenditure, and we expect its effect on GTFP to be negative.

C Economic Value per Unit of Carbon Emission

Growth in the economic value per unit of carbon emission typically coincides with a rising share of technology-intensive industries—such as new energy, advanced manufacturing, and digital services—which possess stronger R\&D capabilities and apply cleaner technologies. This shift reduces energy consumption in production and thereby effectively enhances GTFP. As the economic value per unit of carbon emission increases, traditional energy-intensive and high-pollution industries are gradually squeezed out by market and policy mechanisms, prompting the reallocation of production factors toward high-efficiency, low-environmental-cost sectors and improving overall resource allocation efficiency. We measure economic value per unit of carbon emission as the ratio of actual GDP to total carbon emissions, and we expect its effect on GTFP to be positive.

D Employment Structure

Compared with other sectors, the tertiary sector exhibits higher value added and lower pollution emissions. Therefore, the reallocation of human resources and capital toward the tertiary sector contributes to improved production efficiency and, in turn, enhances green total factor productivity. We measure employment structure by the ratio of tertiary-sector employment to total employment, and we expect its effect on GTFP to be negative.

(4) Mediator Variable

Based on the mediation-effect hypothesis, this study selects the total number of green patent authorizations per 10,000 people as the mediator. To avoid inaccuracies arising from inconsistent units in the regression, the green patent authorization data are normalized. The per-10,000-population green patent authorization is calculated as the total number of green patents authorized divided by the resident population.

(5) Threshold Variable

Based on the threshold-effect hypothesis, this study uses the share of regional industrial output value as the threshold variable, measured as regional industrial output value divided by GDP.

3.2. Measurement Method for Green Total Factor Productivity

The dependent variable, Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP), is measured using the Slack-Based Measure (SBM) model. The SBM model is a derivative of the traditional DEA framework. Traditional radial models tend to ignore slacks in inputs and outputs, which can bias research conclusions. To address the neglect of slack variables in efficiency evaluation by radial models, Tone (2001) proposed the SBM model (Slack-Based Measure). This model accounts for slacks in both input and output variables, substantially improving the robustness of the results. Therefore, this study employs the SBM model to measure GTFP. The model is specified as follows:

In equation(1) and (2), m is the number of input indicators; Sg and Sb are the numbers of desirable and undesirable outputs, respectively; x0、y0、b0 denote the input, desirable-output, and undesirable-output vectors of the decision-making unit under evaluation ; X、Yg、Yb are the corresponding data matrices for all n decision-making units in the sample; λare the intensity weights ;S-、S+、Sb are the slack variables for input excess, desirable-output shortfall, and undesirable-output excess, respectively. When all slack variables are zero, the DMU lies on the efficient frontier; When ρ∗ <1 , indicates inefficiency, with smaller values reflecting greater distance from the frontier and thus lower efficiency.

3.3. Method for Measuring Urban Compactness

To ensure measurement objectivity, this study similarly employs the entropy weight method for weight assignment and quantification of the Urban Density index system. The methodological procedure consists of the following steps:

- ➀

Pre-processing of data for entropy weight method calculation

First, the data are normalized and inverted:

Positive indicators:

Negative indicators: (1)

In the formula, is the data that were dimensionless using the polarization method , , are maximum and minimum value of index.

- ➁

Calculation of information entropy using the entropy method

is the information entropy of index; denotes the sample city ; is the indicator data after dimensionless processing.

- ➂

Calculation of the weights of the indicators

is the weight of index , is the sample city ,is the information entropy of city .

- ➃

Calculating Urban Density

is the weight of index , is the sample city , is compactness of a city, is the indicator data after dimensionless processing.

3.4. Model Construction and Data Sources

(1) Model Construction

Based on the above analysis, the following model is constructed:

Model 1: (5)

In the equation, GTFP denotes green total factor productivity; Compact represents urban compactness; FDI indicates the level of foreign investment; FAI refers to the degree of fiscal decentralization; GDP denotes the economic value per unit of carbon emission; ES indicates the employment structure; ε is the random error term; a₀ to a₅ are the parameters to be estimated; and i and t represent city and time, respectively.

Model 2: (6)

Model 3: (7)

In Equation (6), M represents the mediating variable, namely green technological innovation. Control denotes the set of four control variables. To test for mediation effects, regression analysis is conducted based on Model 2 to examine whether urban compactness has a significant impact on green technological innovation. If both coefficients α₁ and β₂ are statistically significant, a significant mediation effect is present. If β₂ is not significant while α₁ is, this indicates full mediation. If both are significant, it indicates partial mediation. If the stepwise regression results are not significant, further tests using the Sobel test and Bootstrap method are conducted to verify the existence of the mediation effect.

Model 4: (8)

In Equation (8), GTFP denotes Green Total Factor Productivity, COMP represents urban compactness, and qit is the threshold variable indicating the proportion of industrial output, γis the threshold value to be estimated, Xit represents control variables,λdenotes time fixed effects, andεis the random disturbance term. I(qit≤γ) takes the value 0 when the threshold variable is less than or equal toγ; I(qit>γ) takes the value 1 when the threshold variable is greater than .

(2) Research Scope and Data Description

This study covers cities within the Dianzhong Urban Agglomeration and the Chengdu–Chongqing Urban Agglomeration. The Dianzhong Urban Agglomeration is located in China’s southwestern frontier region, where economic development is relatively lagging; the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative has positioned it as China’s frontier for opening to the southwest. The Chengdu–Chongqing Urban Agglomeration, by contrast, has a higher overall level of economic development, and with the inauguration of the Chengdu–Kunming and Chongqing–Kunming high-speed railways, its linkage with the Dianzhong Urban Agglomeration has become increasingly close—making their coordinated development a focal point of both research and practice. Both agglomerations lie in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, an ecologically sensitive area, and their administrative regions encompass diverse landforms such as mountains, hills, and plains. Identifying the pathways through which urban compactness affects GTFP in these two city clusters can inform their coordinated development and the formulation of differentiated urban spatial planning policies. Due to severe data gaps and difficulty in obtaining reliable statistics for Chuxiong City, it is excluded from this study.

The data used to measure urban compactness, Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP), regional gross domestic product, the share and value added of secondary and tertiary industries, resident population, average number of employees at year-end, administrative land area, per-capita road area, number of buses per 10 000 people, number of taxis per 10 000 people, total fixed-asset investment, number of green patent authorizations, fiscal expenditure within budget, total foreign capital utilization, and total energy consumption (10 000 tons of standard coal) are primarily drawn from the 2011–2022 editions of the China City Statistical Yearbook and the statistical yearbooks of each case city. Data on built-up area, construction land area, and residential land area were obtained through consultation with local government Natural Resources Bureaus and Housing and Urban–Rural Development Bureaus. Industrial sulfur dioxide (SO₂) emissions, industrial waste-gas emissions, and industrial wastewater emissions were collected via local government Ecological Environment Bureaus, supplemented by the China City Statistical Yearbook and each case city’s statistical yearbook. Total electricity consumption and average on-the-job employee counts were sourced from local government reports and the case cities’ statistical yearbooks. To ensure the scientific rigor and accuracy of the research, the foreign capital utilization variable was logarithmically transformed to reduce data distortion. Missing values were filled using interpolation and ARIMA methods. Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in

Table 3.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

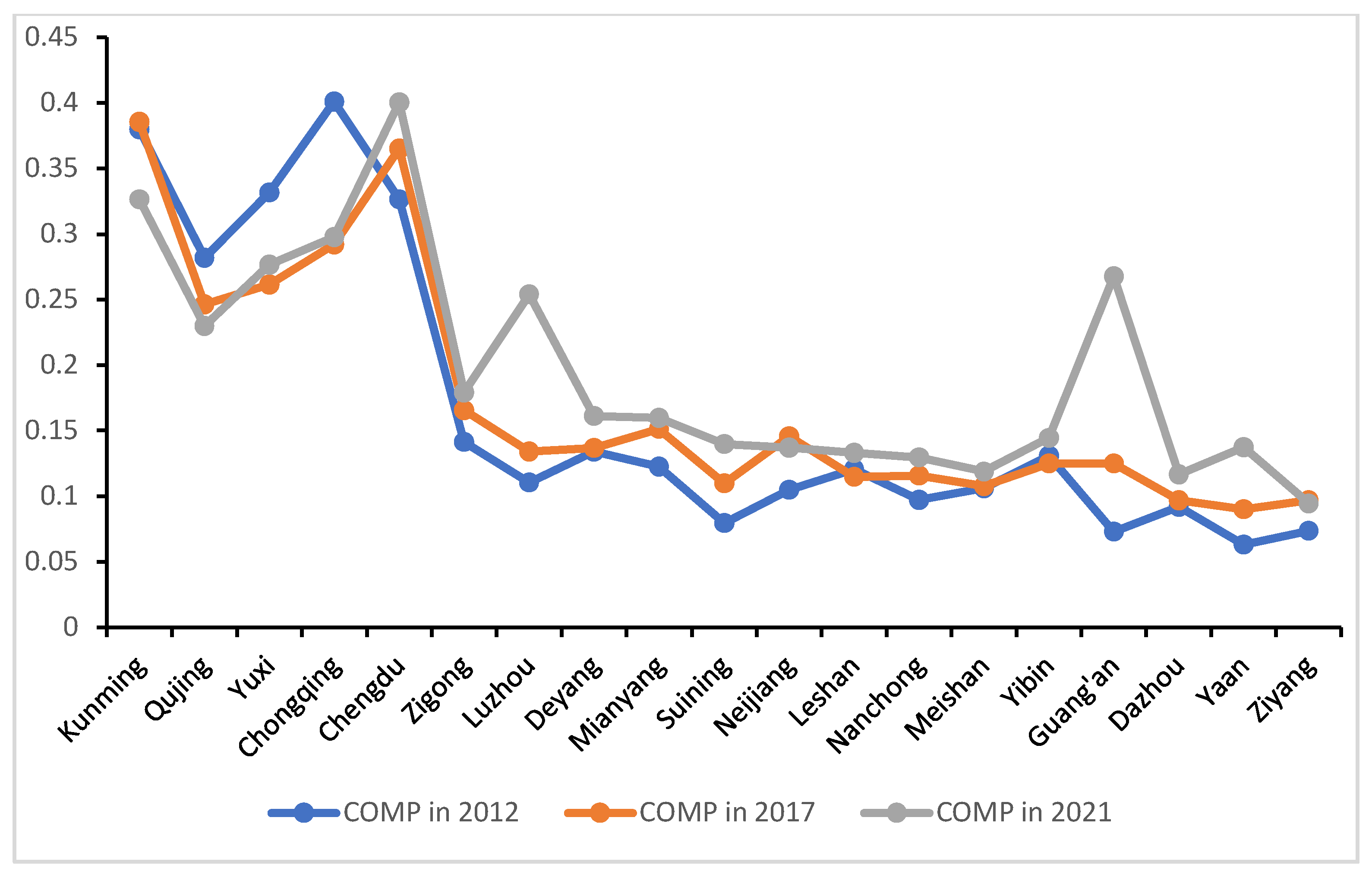

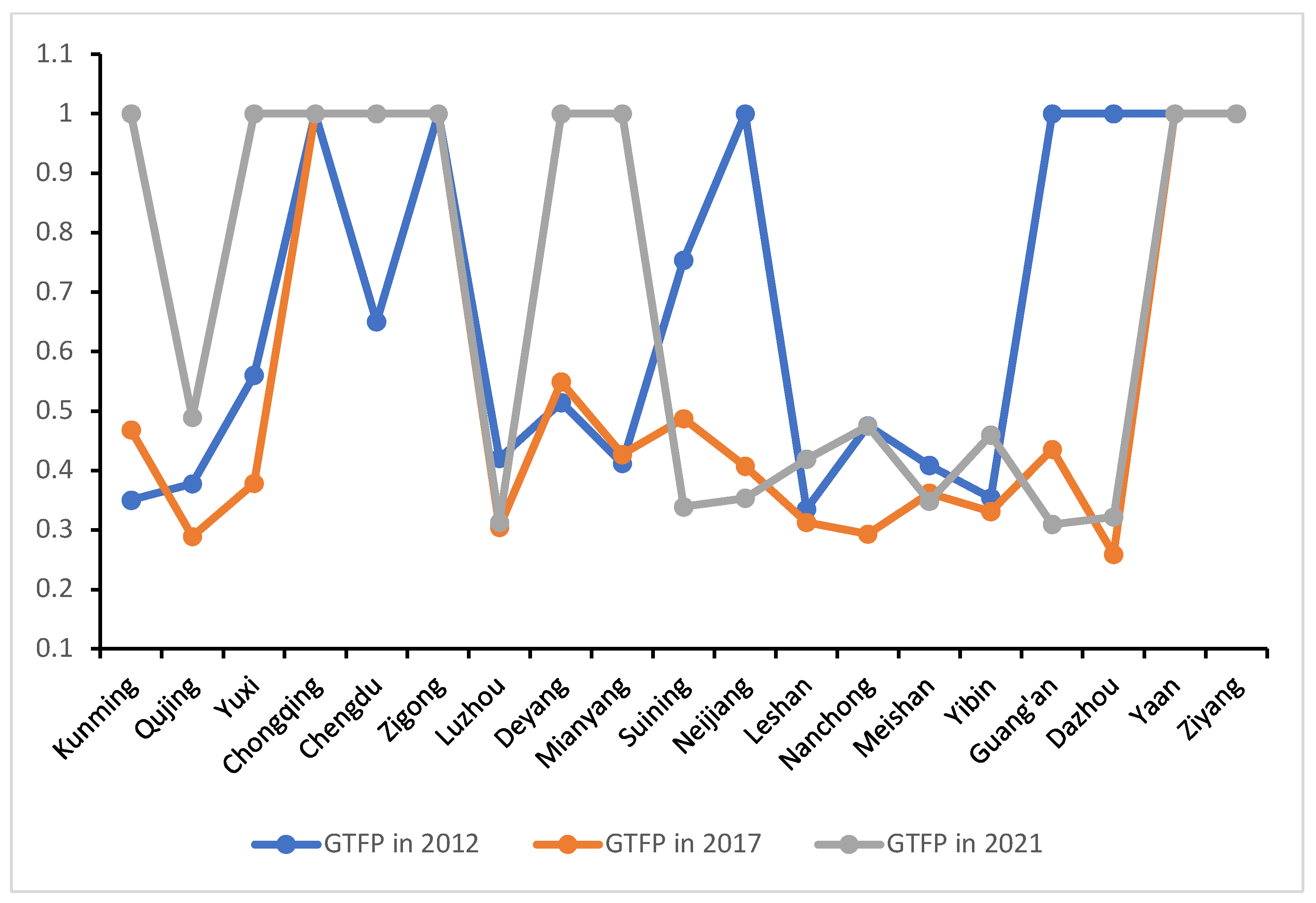

4.1. Trends in Urban Compactness and GTFP

By applying the entropy-weight method, we calculated the weights and scores of each indicator for urban compactness, and we used a SBM model to compute composite GTFP scores (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). We then selected the 2011, 2017, and 2021 scores for urban compactness and GTFP and visualized them in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. By comparing the two charts, we observe that, aside from a few cities showing a downward trend, both urban compactness and GTFP levels have generally increased in sync over the eleven-year period, providing a preliminary data foundation for further examination of the mechanisms through which compactness influences GTFP.

Figure 4.

Trends in Urban Compactness.

Figure 4.

Trends in Urban Compactness.

Figure 5.

Trends in GTFP.

Figure 5.

Trends in GTFP.

4.2. Analysis of Full-Sample Regression Results

To avoid errors arising from multicollinearity, we first conducted a multicollinearity test on the variables involved in the study, as shown in

Table 4. All variables have VIF values below 5, indicating that multicollinearity is weak in the regression model.

Before conducting the overall regression, we performed a Hausman test on the model to assess its appropriateness, with results shown in

Table 5. The Hausman test rejects the null hypothesis (P < 0.01), indicating that the fixed-effects model is more suitable for the empirical analysis.

On this basis, we conducted a full-sample regression, and the results are presented in

Table 6. Urban compactness has a positively significant effect on GTFP at the 5% level (0.65), indicating that greater compactness can promote GTFP improvement. As economic compactness increases and economic activities become more concentrated, economies of scale emerge, boosting production efficiency and reducing resource consumption, thereby enhancing urban GTFP. Through denser road-network planning combined with compact spatial planning, increases in network density and functional-zone compactness reduce greenhouse-gas emissions caused by excessive traffic and long commuting distances, further improving GTFP. Moreover, higher population density and concentrated human capital improve labor productivity. For example, the spillover of high-quality education and medical resources from central cities raises the human-capital level in surrounding areas. A concentrated population also fully leverages shared public services (e.g., transportation and healthcare), lowering living costs, attracting more highly skilled people, and creating a positive cycle that provides a human-capital advantage for upgrading urban industrial technology, thus affecting GTFP.

Among the control variables, the level of foreign direct investment, the economic value per unit of carbon emissions, and the employment structure each have a positive and significant impact on GTFP at the 1% level. In contrast, fiscal decentralization has a negative and significant effect on GTFP at the 1% level.

OPEN also shows a positive and significant effect on GTFP, suggesting that higher openness advances marketization, fosters a fairer competitive environment for enterprises, and helps channel production factors such as capital and labor toward high-technology, high-efficiency, lower-energy-consumption, and higher-value-added firms, thereby optimizing resource allocation. A higher level of external investment typically reflects stronger intellectual-property protection and more thoroughly price-mediated production factors, which encourage firms to pursue green technological innovation, gain competitive advantage, and in turn drive improvements in GTFP.

The positive and significant effect of GDP on GTFP indicates that increasing this metric helps enhance GTFP. Higher economic returns per unit of carbon emissions optimize the return on investment in green technologies, raise their economic value, and facilitate their diffusion and application, thereby boosting GTFP. In addition, a higher economic value per unit of carbon emissions improves resource-allocation efficiency: strong economic incentives steer capital and production inputs toward low-carbon industries such as renewable energy and services, further enhancing GTFP.

The negative and significant effect of FAI on GTFP suggests that excessive administrative intervention may occur in resource allocation. When governments allocate resources through administrative directives rather than market signals, capital and labor may flow into suboptimal sectors, inhibiting the green transformation of industry. In the Dianzhong and Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomerations, economic development lags overall and local fiscal revenues are limited, making these regions heavily dependent on higher-level transfer payments. Preferring broad, short-term spending to quickly generate revenue, local governments fail to provide targeted support for green industries and struggle to build long-term green-technology capacity.

The positive and significant impact of ES on GTFP indicates that a higher share of tertiary-industry employment promotes GTFP growth. Compared with primary and secondary sectors, the tertiary industry typically generates greater economic value with lower pollution emissions. Moreover, tertiary-industry jobs usually offer higher incomes, and increasing their share supports higher household incomes, drives an upgrade in consumption patterns, and stimulates spending on culture, education, and entertainment. This shift encourages green consumption and influences producers to adopt green-industry practices and technological upgrades.

4.3. Robustness Check

(1) Two-sided Winsorization of the Core Explanatory Variable

To perform a robustness check, the core explanatory variable, urban compactness (COMP), was subjected to two-sided Winsorization. The results, shown in

Table 7, indicate that the significance and signs of the coefficients for COMP and the control variables are largely consistent with the original regression results. The effects of each variable on the dependent variable remain essentially unchanged, confirming the robustness of the regression findings.

(2) Robust Regression

Building on the original regression model, we conducted a robust-standard-errors test to examine model stability. The results in

Table 8 show that urban compactness still has a significantly positive effect on GTFP (P < 0.01), and the significance levels and directions of the remaining control variables remain unchanged, confirming the robustness of the findings.

4.4. Mediation Effect Test

To ensure the scientific rigor and reliability of the mediation-effect test, we applied the bootstrap method to assess the robustness of the mediation effect. The results are shown in

Table 9. The total-effect coefficient is 0.653, which represents the estimated overall effect of the independent variable (urban compactness) on the dependent variable (GTFP) via the mediator (green technological innovation). The “a” coefficient (0.977) measures the effect of COMP on the mediator, and the “b” coefficient (0.371) measures the effect of the per-10,000-population green patent authorizations on GTFP. The direct-effect coefficient (c′) is the coefficient on COMP from the full model. Hence, the product a × b (0.363) is the mediation-effect value, with P < 0.01 and a 95% confidence interval that does not include zero, indicating a robust mediation effect.

The coefficient of 0.977 for the effect of urban compactness on green technological innovation (a-value) indicates that increased compactness promotes green technological innovation. Through intensive land use, cities can implement centralized green infrastructure investments, providing policy and environmental support for firms’ green transformation; compact spatial layouts intensify land-price competition, forcing low-value-added, high-energy-consumption industries either to relocate or to upgrade via green technologies, thereby enhancing GTFP; and compact urban forms facilitate the efficient flow of information, technology, and talent, improving resource-allocation efficiency, accelerating technology diffusion, and fostering industrial synergies that underpin the development of low-energy-consumption, high-tech industries and modern services.

The effect of green technological innovation on GTFP is positive and significant at the 5% level, with a coefficient of 0.371 (b-value), demonstrating that green technological innovation fosters GTFP improvement. Green technological innovation raises firms’ production efficiency and reduces energy consumption, aiding traditional manufacturing in its structural transformation and weakening carbon-emission intensity. Moreover, it drives firms to diversify green-product portfolios and lower production costs, which tends to reduce prices, satisfy and stimulate green-consumer demand, and thus support the sustainable growth of GTFP.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

The above sections have examined the overall effect of urban compactness on GTFP and the mediating role of green technological innovation. However, cities in our sample belong to different geographic contexts and stages of economic development, so the impact of compactness on GTFP may vary with economic development level. To test this, we used the 2021 per-capita GDP of each city: those above the sample average were classified as “higher-development” cities, and those below as “lower-development” cities. The higher-development group comprises nine cities: Kunming, Yuxi, Chongqing, Chengdu, Zigong, Deyang, Mianyang, Leshan, and Yibin; the lower-development group comprises ten cities: Qujing, Luzhou, Suining, Neijiang, Nanchong, Meishan, Guang’an, Dazhou, Ya’an, and Ziyang.

4.5.1. Heterogeneity Test by Economic Development Level

We divided the sample into the two development-level groups and estimated the effect of urban compactness on GTFP separately for each. The results, shown in

Table 10, indicate that for cities with above-average economic development, compactness has a positive and significant impact on GTFP, with a coefficient of 0.88. In contrast, for cities below the average, the effect of compactness on GTFP is not statistically significant.

Cities with higher economic development typically have more advanced industrial structures and higher value added, which raises the demand for green technological innovation to reduce production costs. Moreover, the clustering of technology-intensive industries facilitates green-technology learning and diffusion among firms, further improving productivity and GTFP growth. Conversely, less-developed cities often lack adequate infrastructure and remain in an industrial transition phase, with limited capacity to absorb green industries. Their constrained fiscal resources are largely directed toward basic infrastructure and social services, weakening support for emerging green sectors and potentially crowding out green investment, which may explain the insignificant effect of compactness on GTFP in these cities.

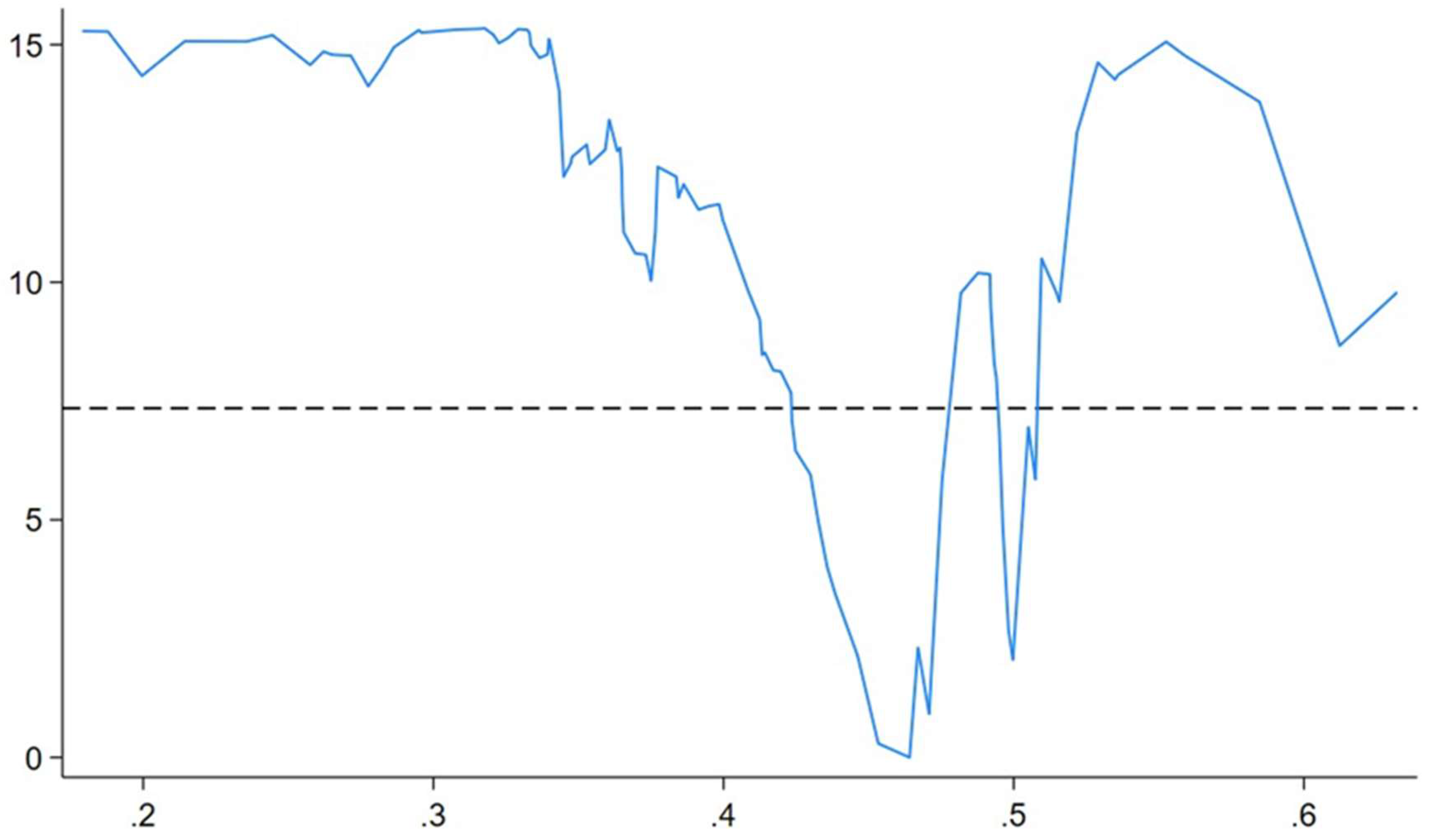

The threshold-effect regression results are shown in

Table 11. The test indicates that when the share of industrial output is at a lower level, urban compactness has a positive and significant effect on GTFP at the 5% level, with a coefficient of 0.606. Once the industrial-output share exceeds the threshold value, compactness exerts a positive and significant effect on GTFP at the 1% level, with a coefficient of 1.528. This suggests that at lower levels of industrial output, a more compact urban form reduces transportation costs and improves land-use efficiency, thereby enhancing overall resource-allocation efficiency and positively driving GTFP. However, because the industrial system is relatively small at this stage, the spillover effects of green technology are limited, so the impact of compactness on GTFP remains modest.

When the industrial-output share is at a higher stage, infrastructure and public services are more fully developed. In this context, the economies-of-scale and agglomeration effects induced by spatial compactness become more pronounced, attracting greater green-technology investment and providing sufficient research funding, which strengthens the capacity for green-technology development and diffusion. Furthermore, advancing a compact spatial layout facilitates knowledge sharing and accelerates green-technology progress.

Fig 2 plots the nonlinear marginal-effect curve of urban compactness on GTFP across different compactness scores. The figure shows that once the threshold (0.464) is exceeded, the slope of the compactness–GTFP relationship increases markedly, consistent with the analysis above.

Figure 2.

Threshold-Effect Visualization.

Figure 2.

Threshold-Effect Visualization.

Table 12 presents the bootstrap test results, with P < 0.01, indicating that the threshold-effect test is robust.